Abstract

Health crises have a disproportionate impact on communities that are marginalized by systems of oppression such as racism and capitalism. Benefits of advances such as in the prevention and treatment of HIV disease are unequally distributed. Intersecting factors including poverty, homophobia, homelessness, racism, and mass incarceration expose marginalized populations to greater risks while limiting access to resources that buffer these risks. Similar patterns have emerged with COVID-19.

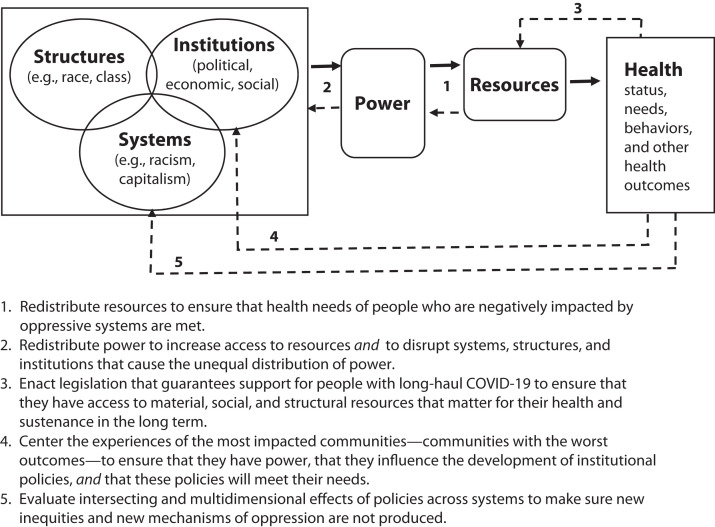

We identify comparable pitfalls in our responses to HIV and COVID-19. We introduce health justice as a framework for mitigating the long-term impact of the HIV epidemic and COVID-19 pandemic. The health justice framework considers the central role of power in the health and liberation of communities hit hardest by legacies of marginalization.

We provide 5 recommendations grounded in health justice: (1) redistribute resources, (2) enforce mandates that redistribute power, (3) enact legislation that guarantees support for people with long-haul COVID-19, (4) center experiences of the most impacted communities in policy development, and (5) evaluate multidimensional effects of policies across systems. Successful implementation of these recommendations requires community organizing and collective action. (Am J Public Health. 2023;113(2): 194–201. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2022.307139)

Communities marginalized by structural inequities often experience a disproportionate burden of disease. This is true for HIV and for COVID-19. About 1.2 million people are living with HIV in the United States, with almost 35 000 new infections each year.1 In 2019, Black Americans accounted for 44% of new HIV diagnoses, although they comprise 13% of the US population. Latino/a/x Americans make up 18% of the population but account for 30% of new cases.1 Rates of HIV infection are high in communities harmed by structural racism and other forms of oppression.2–4 Evidence from a systematic review of studies worldwide suggests that people living with HIV have an elevated risk of contracting severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the cause of COVID-19, and that they have a higher risk of COVID-19 mortality compared with persons who are not HIV-positive.5

HIV and COVID-19 coinfection is likely to increase, and communities hit hardest by systemic oppression such as poverty, racism, homophobia, transphobia, misogyny, homelessness, addiction, residential segregation, food insecurity, mass incarceration, and so forth will continue to bear most of the burden of these public health crises.3,4 Here, we identify comparable pitfalls in responses to HIV and COVID-19 in the United States. We also offer the health justice framework as the central component of our recommended strategies for mitigating the long-term impact of the burdens of the HIV epidemic and COVID-19 pandemic on communities marginalized by structural inequities.

DIFFERENT VIRUSES, SIMILAR RESPONSE PITFALLS

Strategies employed to address COVID-19 are not new. In a lot of ways, these strategies are leading to similar outcomes that emerged from our national response to HIV.

Initial Nonresponse

Following the first confirmed case of COVID-19 in the United States, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) stated that they have “been proactively preparing for the introduction of 2019-nCoV in the United States.”6 This press release was different from CDC’s first publication about HIV in that there was no preparation for what later developed into an epidemic. Reporting the presence of a rare cancer and a rare pneumonia-like disease that killed young gay men, the CDC hypothesized that the virus was contained in seminal fluid and that the disease occurred predominantly among gay men.7

The initial national response was a nonresponse reflecting attitudes about those who were being disproportionately affected—gay men. Writing about how this nonresponse led to a global humanitarian crisis, Greg Behrman, a former US State Department official, stated:

The subpopulations suffering in the United States were not part of Reagan’s constituency.… If the disease was truly heterosexual, then it was a bigger problem (at least politically) than the administration had estimated. They would have to address it, and they didn’t want to do that unless they had to.8(p27)

It was not until 4 years after the crisis began that President Reagan finally acknowledged AIDS in public.8

President Trump’s initial nonresponse to COVID-19 had a similar effect. On January 22, 2020, 2 days after the CDC confirmed the first case in the United States, President Trump stated: “We have it totally under control. It’s one person coming in from China. It’s going to be just fine.”9 A month later, at different occasions, he stated: “Coronavirus is very much under control in the USA… the Stock Market starting to look very good to me!” “I think that’s a problem that’s going to go away.… They have studied it. They know very much. In fact, we’re very close to a vaccine.” “The 15 [cases in the United States] within a couple of days is going to be down to close to zero.”9 President Trump’s underestimation of the virus was different from President Reagan’s dissociation from HIV, which was fueled by widespread homophobia and moral panic around gay male sexuality. However, both presidents were motivated by what was best for them politically, not what was best for public health. Their nonresponses meant no federal public health action, thereby exacerbating suffering.

Structural Determinants of Risk Factors Ignored

Public discussions, medical recommendations, and political actions around HIV did not initially consider the structural drivers of HIV vulnerability. For example, lack of structural and material support such as housing, the absence of social support, employment and housing discrimination, and the criminalization of homosexuality, sex work, and substance use all increase the risk of contracting HIV but were not emphasized.10 The focus was predominantly on the social identities of people who were infected. Indeed, at the beginning of the epidemic, the CDC referred to groups being impacted by HIV as the “Four Hs”—“homosexuals, heroin users, hemophiliacs, and Haitians.”11 However, understanding how structural inequities shape the actions of people with specific social identities and increase exposure to risk is critical. Unfortunately, most of the early epidemiological literature on HIV centered on these groups, sending a message that only people with specific identities were vulnerable. Identities, not structural factors, were highlighted as risk factors. HIV was not an “everyone’s disease.”

With COVID-19, early messaging was that it was indeed everyone’s disease—that we were all in this together. But epidemics highlight and exacerbate existing structural inequities.3,12 As more data became available, it was evident that Black, Latino/a/x, and Indigenous communities; persons living in poverty; people in predominantly underresourced neighborhoods; and those working in the health care sector or who lived with essential workers were disproportionately more likely to be infected, to be hospitalized, and to die from COVID-19.3,13 Structural racism—how our institutions, culture, ideology, norms, and practices create and maintain racial dominance and oppression through the control of resources, producing adverse and racially inequitable outcomes—drives the unjust burden of COVID-19 on racially minoritized groups.3,4,14 And capital accumulation limits access to resources needed to work from home and afford high-quality masks and regular at-home tests.3,14 These larger systemic factors drive inequities in COVID-19 outcomes. However, our national response focuses heavily on individual behaviors.

Blaming Victims

Significant blame has been assigned to groups who contract HIV for whom there is some level of societal moral disapproval of their behaviors. Examples include men who have sex with men, sex workers, and injection drug users. Similarly, people who have not received COVID-19 vaccines and those who have no choice but to continue to go to work when exposed or sick are usually perceived as responsible for why things are not “back to normal.” Underrepresentation of the working class in political processes and resistance to policies such as Medicare for All that are likely to facilitate engagement in healthy behaviors and access to care also increase the tendency to see risks as products of individual choices rather than outcomes of the political contexts.

The ability of the most privileged and insulated members of society to work from home or stay at home when exposed, for example, is attributable to less-privileged members assuming more risks because of the absence of social policies and safety-net programs that protect them.15 Attributing a public health crisis to individual actions distracts from the structural issues that matter more,16,17 causing our policy responses to unfortunately center individual responsibility even when personal agency is significantly constrained by structural factors. Blaming individual actions that are risky such as going to social gatherings is both politically convenient and driven by capitalism. For example, government avoids imposing restrictions on big businesses and employers. Victim blaming might also contribute to fear and reluctance to seek care, leading to further suffering.

Profits Over People

One of the most devasting things about the HIV epidemic is that it could have been stopped sooner by making life-saving antiretroviral therapy (ART) accessible to sub-Saharan Africa, Central and South America, and India, where HIV prevalence rates were highest.8 Driven by capitalism, pharmaceutical companies in wealthy countries colluded with international organizations such as the World Trade Organization and with some leaders of Western countries to set policies around manufacturing and distribution of ART that kept these medications out of the reach of people who needed them the most. Access to ART motivates people to get tested, decreases rates of transmission by reducing viral load, and prevents progression to AIDS.18 It was only until after years of HIV activism that generic drugs were finally allowed to be imported by countries without previous access to medications.8 By then, it was too late for many. The toll was already devastating.

The lack of global access to COVID-19 vaccines mirrors the lack of global access to ART for HIV. When vaccines first became available, several groups warned that these vaccines would not be available to people living in impoverished countries as pharmaceutical companies would not share the formula so that they could maximize profits as wealthy countries hoarded vaccines. Indeed, wealthy countries were negotiating advance purchasing deals before the vaccines were even approved.19 Stockpiling of vaccine doses by wealthy countries while many in poorer countries remain unvaccinated increases odds of additional variants of concern.

Inequities in access to HIV treatment (ART), preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP), and COVID-19 vaccines are also prevalent in the United States. For example, Black and Latino men who have sex with men have less access to PrEP and ART than their White peers.2,20 And economically marginalized populations have lower COVID-19 vaccination rates compared with high-income populations.21 Nothing indicates our prioritization of profits over people more than the fact that one’s ability to access lifesaving medications and vaccinations depends on access to money, the politics of where they live, and other flexible resources.

THE HEALTH JUSTICE FRAMEWORK

We propose the health justice framework as the basis for sustainable, equitable, and ethical responses to HIV and COVID-19. Drawing from intersectionality theory,22–24 the framework is premised on the assumption that all systems (e.g., capitalism, racism, homophobia, misogyny, xenophobia), all structures (e.g., race, gender, class, sexuality), and all institutions (e.g., political, economic, social) matter for health and well-being. As shown in Figure 1, these structures, systems, and institutions intersect to create and maintain unequal distribution of power and access to and distribution of resources that matter for health.

FIGURE 1—

Policy Recommendations Based on the Health Justice Framework

We conceptualize health justice as the equitable redistribution of power and resources such that people with the greatest need are prioritized, and where the processes of knowledge production around need, restructuring, and redistribution are grounded in the experiences of populations most impacted by health inequities. Health justice is a paradigm and collection of actions that interrogate systems; structures; social, political, economic, and cultural institutions; and networks of relationships that, although normalized, create and perpetuate inequities in power and access to resources that matter for health, including the ability to engage in healthy behaviors.

It is different from health equity in that it extends beyond removing obstacles and beyond giving everyone a fair opportunity to be healthy.25 It is also distinct from previous conceptualizations of health justice that focus on recognizing the human and civil rights of everyone.25 Specifically, our conceptualization of health justice considers how barriers to health occur because people with more power (ability to control resources and shape how the society is structured, whether that power is conferred by statuses such as occupation or by structures such as race) and access to resources (e.g., social, economic, material, political) benefit at the expense of people with less power and resources.

Addressing barriers to well-being from a health justice perspective requires people and institutions with the most power to reject the benefits of their power and to work toward relinquishing that power altogether—a feature that distinguishes health justice from health equity and health as a human right. For example, the ability of multibillion-dollar corporations to amass wealth during a pandemic comes at the expense of workers who have no choice but to return to work after a positive coronavirus test. The ability to get groceries delivered comes at a cost to essential workers and low-income factory workers. While one’s job might be because they attended a good school or because someone “put in a good word” for them, it all comes at the expense of someone else who might be just as smart and hardworking, but who could not attend a resource-rich school because of structural factors like residential segregation or the lack of networks that facilitate desirable employment. The health justice framework certainly complicates the idea that none of us is free until all of us are free. While we agree that interconnectedness of systems and institutions means that we are deeply implicated in each other’s lives, we also argue that some of us are only free because some of us are oppressed. Therefore, the health justice framework seeks liberation, restitution, and advancement for communities hit hardest by legacies of marginalization.

STRATEGIES FOR THE PATH FORWARD

Public health policies are more effective when implemented by federal, state, and local levels of government.26 While we identify 5 policy recommendations to help eliminate health inequities caused by HIV and COVID-19, we concede that political forces in the United States (e.g., filibuster, gerrymandering, and corporate lobbying) are significant obstacles to implementing these. Community organizing and collaborations between public‒private and nonprofit sectors are important for public health27–29; hence, they are necessary for the implementation of the recommendations we propose in Figure 1.

Redistribution of Resources

People who are disproportionately affected by HIV and COVID-19 are often marginalized and oppressed. Hence, they do not have resources to effect their own liberation. This is where government should come in. The United States is taking an approach to ending the pandemic that still largely relies on individual choices and resources. In March of 2022, the White House released the National COVID-19 Preparedness Plan,30 an updated plan to meet current challenges. The first goal of the revised plan was to protect against and treat COVID-19 by encouraging testing, wearing masks when risks of transmission are high, and increasing access to vaccines, high-quality masks, and life-saving antiviral pills. To a large degree, frequent testing, wearing masks, and getting vaccinated are contingent upon personal resources and preferences.

One major failure in our response to the HIV epidemic is we only focused on behavioral changes while not providing resources such as universal health care and needle-exchange programs that make behavioral modifications possible and sustainable.3,8 Fortunately, rapid tests for COVID-19, vaccines, and high-filtration masks have become more available. However, accessing them still relies on individual resources. For example, people who are insured have relatively easier access to free tests compared with those who are uninsured. Similarly, ordering and receiving free test kits from the government requires access to the Internet and a home address. COVID-19 is transmitted by an airborne virus. Thus, the quality of ventilation in buildings such as schools and offices matters. The likelihood of working from home or in buildings with good air circulation is partially dependent on one’s socioeconomic status.

We call on the Biden administration to expand the distribution of high-quality masks, tests, vaccines, and medications, especially for populations in low-wage, high-risk essential jobs. Legacies of marginalization ensure that people most at risk also have limited resources including specialized knowledge and time to find the free home test kits, masks, and medications that are available. Government has a responsibility to provide resources, to develop infrastructure and strategies that will connect these resources to people who need them the most, and to mandate employers to do the same. Resources to improve ventilation and air filtration in buildings, including access to portable air cleaners, should be made available.

Redistribute Power

We must truly prioritize people over profits. One of the goals of the COVID-19 Preparedness Plan is to prevent economic and educational shutdowns by keeping schools and businesses safely open.30 Two months before the release of the revised preparedness plan, the CDC shortened the isolation period from 10 days to 5 days for those who test positive for SARS-CoV-2. However, the ways by which prioritization of the economy undermine collective health and well-being and increase the risk of community transmission are not considered. One of the 10 essential public health services is to utilize legal and regulatory actions to improve and protect the health of the public.31 The government has power to enforce regulations for schools and multibillion-dollar industries alike. People most negatively impacted do not have the power to restructure institutions and policies in ways that would facilitate their liberation. This requires the Biden administration to develop and enforce regulations to protect health.

Government has a history of regulating all kinds of activities when politically convenient. Driven by homophobia and the need to control the sexuality of gay men, bathhouses and gay bars were shut down, and gay men were banned from donating blood as the government argued that these were critical in curbing the spread of HIV.32 Currently, there are no mandates or enforceable policies that regulate congregation of people indoors or on airplanes. Masks are optional. Masking when indoors or when in crowds is an individual choice shaped by politics.33 And people who might be unvaccinated, immunocompromised, or otherwise more susceptible to the virus are still at greater risks and remain unprotected.

We recommend workplace safety standards, mask mandates and capacity limits for indoor public gatherings, vaccine mandates for domestic flights, and paid time off for up to 10 days for people who have tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, pay that is supplemented by the federal government and from a proportion of profits and net revenues of large, wealthy employers.

Enact Legislation for People With Long-Haul COVID-19

Significant funds should be made available to specifically support the growing number of people who are unable to work because of long COVID-19‒related limitations. One of the most significant national policy responses to HIV was the enactment of the Ryan White Program, which pays for medical and support services for low-income persons living with HIV. A similar legislation should be enacted for long-term medical and support services that are needed by people who are navigating COVID-19‒related disabilities, unable to work, or in precarious employment situations with no benefits to support comprehensive rehabilitation services.

At the state level, Medicaid expansion is also necessary, especially as it is likely to cover a more comprehensive set of services for those who, because of the undue burden of COVID-19, have become eligible for Medicaid. Southern states that have not expanded Medicaid are also states with relatively high HIV prevalence and greater incidence of COVID-19.4 Ultimately, universal health care, Medicare for all, or some version of a single-payer system is needed. It is time to restructure our health care system such that access to health services for most persons in the United States is not contingent upon resources such as employment.

Center Most-Impacted Communities

We must center disproportionately affected communities in policy development and implementation. One successful response to HIV is that people living with HIV are involved in informing, developing, implementing, and monitoring programs and policies.4 For example, for organizations to obtain Part A funds from the Ryan White Program (funds that support HIV services in urban areas), there are requirements for these organizations to demonstrate mechanisms through which people living with HIV participate in needs assessment, prioritization of services, and allocation of funds to these services. A similar requirement that policy and program responses to COVID-19 should have a process for community leadership in planning, implementation, and monitoring is necessary. The experiences of patients with long-haul COVID-19 and their advocates will play a central role in ensuring people with long COVID-19 are supported.34

Evaluate Policies Across Systems

We must consider how benefits of our responses to COVID-19 might be inequitably distributed, thus exacerbating other inequities. With HIV, for example, the development of ART and PrEP increased viral suppression and reduced new infections in general but widened racial inequities in viral suppression rates and rates of new infections because, compared with Black and Latino men who have sex with men, White men who have sex with men had more access to these medications.2,3,20 When there is a new development that prevents disease and death, people with more resources are usually those who can take advantage of these developments. They benefit the most because resources, whether social, financial, or technological, are usually transferable and can be used in many different situations to ultimately improve health.14

Access to vaccines, high-filtration masks, and test kits by people with resources can widen existing inequities in COVID-19 outcomes. They can also widen socioeconomic inequities as persons with access to vaccines, masks, and tests likely have greater odds of staying healthy, continuing to work, attending classes, and so forth. Similarly, increase in the use of telemedicine and the move to virtual work and school might create new inequities in learning outcomes and health care utilization. While these developments and measures are critical for controlling the pandemic, we need monitoring systems in place to understand, mitigate, and eliminate new inequities.

CONCLUSION

The health justice framework considers the central role of power and resources in the liberation and advancement of communities who are disproportionately affected by health crises, including those caused by noncommunicable diseases and other conditions—power to make decisions that can affect a broad range of systems, institutions, structures, and populations. Power to make decisions and to control resources needed to support these decisions can alter the trajectories of crises. Government has power to enact far-reaching regulations and mandates and to develop and enforce policies. Government can also make resources available and accessible by regulating and taxing large corporations; by providing supplements, subsidies, and tax reliefs to individuals and businesses; and through the enactment of policies and programs that enable people to save money.

Both HIV and COVID-19 have wrought significant loss, grief, trauma, and suffering. Communities hit hardest by legacies of marginalization are disproportionately affected and should lead the development of long-term solutions. Investing in community-based participatory research now is essential so that communities can begin to direct and work with researchers to identify and prioritize their needs, to develop context-specific approaches to address these needs, and to work toward liberation and advancement. In 40 years, we have made significant advances in HIV prevention and treatment. Yet, the benefits of these advances are not equally distributed. We are seeing the same patterns with COVID-19 in which the benefits of advances such as vaccines, at-home test kits, and medications are unequally distributed. This is compounded by the fact that communities already disproportionately burdened by the HIV pandemic are also burdened by COVID-19.

We need an equitable society to prevent disproportionate impact of health crises. The Coronavirus Tax Relief in the form of economic impact payments and the advance child tax credits helped restore some of the income losses incurred by individuals and families. However, broad structural changes are necessary for the liberation of marginalized populations and for significant long-term benefits that can finally end legacies of marginalization. This is an issue of justice. This is also within our reach. People, systems, and institutions that benefit from structural inequalities at the expense of marginalized communities have a responsibility to relinquish these benefits to level the socioeconomic field.

In the end, government has the utmost responsibility to act decisively by investing in policies that address multiple dimensions of inequality. Policies such as universal health care, guaranteed living wage, universal access to broadband Internet, universal access to childcare regardless of employment status and income, and guaranteed and expanded sick leave will go a long way toward achieving a more equitable society. But government will not act simply because we wish for action. Community organizing; building grassroots movements; advocacy; public, private, and nonprofit collaborations; and grassroots activism are necessary strategies to influence change, even at different levels of government.16,35,36

The abolition movement, for example, has been successful in bringing the idea of abolition into the mainstream. People are actively talking about police and prison abolition, and we have seen a few jurisdictions redistribute funding away from policing.37 Similarly, collective power and action have led to changes in local, state, and federal-level policies that have improved, even incrementally, the health of many constituents such as nonsmokers, persons with disabilities, and people living with HIV.38 Amid political resistance to change and in the absence of governmental action, movement building and community organizing are critical.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Lisa Bowleg, PhD, for the extensive and helpful comments on the first version of this article.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

There are no conflicts of interest.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

Human participants were not involved.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV surveillance report. 2019. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html

- 2.Doshi RK, Bowleg L, Blankenship KM. Tying structural racism to human immunodeficiency virus viral suppression. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(10):e646–e648. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spinner GF. The intersection of HIV, COVID-19 and systemic racism. J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2021;14(2):8. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blackstock OJ. Ensuring progress toward ending the HIV epidemic while confronting the dual pandemics of COVID-19 and systemic racism. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(8):1462–1464. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ssentongo P, Heilbrunn ES, Ssentongo AE, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of COVID-19 in HIV-infected individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):628. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-85359-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/p0121-novel-coronavirus-travel-case.html

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pneumocystis pneumonia—Los Angeles. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1981;30(21):250–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Behrman G. The Invisible People: How the US Has Slept Through the Global AIDS Pandemic, the Greatest Humanitarian Catastrophe of Our Time. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gore D, Kiely E, Robertson L, Rieder R.2021. https://www.factcheck.org/2020/10/timeline-of-trumps-covid-19-comments

- 10.Curran JW, Jaffe HW, Hardy AM, Morgan WM, Selik RM, Dondero TJ. Epidemiology of HIV infection and AIDS in the United States. Science. 1988;239(4840):610–616. doi: 10.1126/science.3340847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bazell R. NBC News. November 6, 2007https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna21653369

- 12.Bowleg L. We’re not all in this together: on COVID-19, intersectionality, and structural inequality. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(7):917. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tan SB, DeSouza P, Raifman M. Structural racism and COVID-19 in the USA: a county-level empirical analysis. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2022;9(1):236–246. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00948-8. https://doi.10.1007/s40615-020-00948-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laster Pirtle WN. Racial capitalism: a fundamental cause of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic inequities in the United States. Health Educ Behav. 2020;47(4):504–508. doi: 10.1177/1090198120922942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Navarro V. What is happening in the United States? How social classes influence the political life of the country and its health and quality of life. Int J Health Serv. 2021;51(2):125–134. doi: 10.1177/0020731421994841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bassett MT. Tired of science being ignored? Get political. Nature. 2020;586(7829):337. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-02854-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Antonio-Villa NE, Fernandez-Chirino L, Pisanty-Alatorre J, et al. Comprehensive evaluation of the impact of sociodemographic inequalities on adverse outcomes and excess mortality during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Mexico City. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;74(5):785–792. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nguyen V-K, Bajos N, Dubois-Arber F, O’Malley J, Pirkle CM. Remedicalizing an epidemic: from HIV treatment as prevention to HIV treatment is prevention. AIDS. 2011;25(3):291–293. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283402c3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dyer O. COVID-19: many poor countries will see almost no vaccine next year, aid groups warn. BMJ. 2020;371:m4809. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mayer KH, Agwu A, Malebranche D. Barriers to the wider use of pre-exposure prophylaxis in the United States: a narrative review. Adv Ther. 2020;37(5):1778–1811. doi: 10.1007/s12325-020-01295-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barry V, Dasgupta S, Weller DL, et al. Patterns in COVID-19 vaccination coverage, by social vulnerability and urbanicity—United States, December 14, 2020–May 1, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(22):818–824. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7022e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crenshaw K. Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Rev. 1990;43(6):1241–1299. doi: 10.2307/1229039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bowleg L. Evolving intersectionality within public health: from analysis to action. Am J Public Health. 2021;111(1):88–90. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.306031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hankivsky O, Christoffersen A. Intersectionality and the determinants of health: a Canadian perspective. Crit Public Health. 2008;18(3):271–283. doi: 10.1080/09581590802294296. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tobin-Tyler E, Teitelbaum JB. Essentials of Health Justice: Law, Policy, and Structural Change.https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=dit4EAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT17&dq=%22Essentials+of+Health+Justice:+A+Primer%22+through+APHA+&ots=x68X-OH-_V&sig=fNrS8ZyHfZh8Y21ltT9_ZUoKLL4#v=onepage&q&f=false2022

- 26.Schneider MJ. Introduction to Public Health. https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=Of_2DwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=what+is+public+health+&ots=-JgJYPfvo9&sig=w2TYtMxYbRZEAboFf7LeEhRCfQs#v=onepage&q=whatispublichealth&f=false2021

- 27.Kaba M. We Do This’ Til We Free Us: Abolitionist Organizing and Transforming Justice. Chicago, IL: Haymarket Books; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Douglas JA, Grills C, Villanueva S, Subica AM. Empowerment praxis: community organizing to redress systemic health disparities. Am J Community Psychol. 2016;58(3-4):488–498. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pastor M, Terriquez V, Lin M. How community organizing promotes health equity, and how health equity affects organizing. Health Aff (Millwood) 2018;37(3):358–363. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1285. https://doi.org/101377/hlthaff20171285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.The White House. 2021. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/NAT-COVID-19-PREPAREDNESS-PLAN.pdf

- 31.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020. https://phnci.org/uploads/resource-files/EPHS-English.pdf

- 32.Mohr RD. AIDS, gays, and state coercion. Bioethics. 1987;1(1):35–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.1987.tb00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scoville C, McCumber A, Amironesei R, Jeon J. Mask refusal backlash: the politicization of face masks in the American public sphere during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Socius. 2022;8:1–22. doi: 10.1177/23780231221093158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Callard F, Perego E. How and why patients made long COVID. Soc Sci Med. 2021;268:113426. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cowan H. Taking the National(ism) out of the National Health Service: re-locating agency to amongst ourselves. Crit Public Health. 2021;31(2):134–143. doi: 10.1080/09581596.2020.1836328. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Campbell C, Cornish F. Public health activism in changing times: re-locating collective agency. Crit Public Health. 2021;31(2):125–133. doi: 10.1080/09581596.2021.1878110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taylor K. The emerging movement for police and prison abolition. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/news/our-columnists/the-emerging-movement-for-police-and-prison-abolition2022

- 38.Hoffman B. Health care reform and social movements in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(suppl 1):S69–S79. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.98.Supplement_1.S69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]