Abstract

The alkylations of chiral seven-membered rings fused to tetrazoles are highly diastereoselective. The diastereoselectivity depended on the placement and the size of the substituent on the ring and on the electrophile. Subsequent alkylations occurred with high stereoselectivity, allowing for the construction of quaternary stereocenters. Computational studies revealed that torsional effects are responsible for the observed diastereoselectivity. Substituted products can be reduced to the corresponding secondary amines, thus providing an approach to synthesize diastereomerically enriched azepanes.

Graphical Abstract

The synthesis of 1,5-disubstituted tetrazoles has been developed because this heterocyclic core structure is present in biologically active synthetic compounds,1-4 including cis-amide bond isosteres.5-6 Introduction of a tetrazole moiety can enhance the potency and specificity of biologically active compounds.7-9 When fused to seven-membered rings, tertrazole-containing compounds display analeptic and nervous-system stimulant properties10-11 that can be tuned by making modifications to the seven-membered ring.12

In this Letter, we report that seven-membered-ring-fused 1,5 substituted tetrazoles can be functionalized through anionic intermediates with high diastereoselectivity. The transformations outlined herein allow for the synthesis of these heterocyclic compounds with well-defined three-dimensional structures.13 Additionally, the substituted tetrazole products can be reduced to the corresponding secondary amines, thus providing a new approach for the synthesis of highly substituted and diastereomerically enriched azepanes.14-16 These reactions build upon the growing number of stereoselective transformations of seven-membered-ring reactive intermediates.17-18 Investigations of the diastereoselective reactions of seven-membered-ring-fused tetrazoles commenced with the alkylations of C4-methyl-substituted tetrazole 1. Lithiation with lithium diisopropylamide followed by treatment with various electrophiles19 afforded α-substituted tetrazoles with high diastereoselectivity (Scheme 1). When iodomethane was used, methylated product trans-2a was formed as a single diastereomer. Bulkier alkyl halides, including allyl bromide, ethyl iodide, and benzyl bromide, underwent alkylation with lower stereoselectivity. Lithiation of tetrazole 1 with tert-butyllithium20 followed by quenching with D2O effected a modestly stereoselective deuteration at C2. In all cases, the electrophile approached the carbanion preferentially from the face opposite that of the remote C4 substituent,21 which contrasts what was observed in the alkylations of seven-membered-ring ε-lactam enolates.17

Scheme 1. Alkylations of C4-methyl tetrazole 1.a,b.

aDiastereomeric ratios were determined by 13C{H} analysis of the crude reaction mixture.22 bIsolated yields of purified products.

The diastereoselectivity for the alkylations of C4-substituted seven-membered-ring-fused tetrazoles was general (Scheme 2). C4-Phenyl tetrazole 3 was alkylated with similarly high stereoselectivities as with methyl-substituted tetrazole 1. The α-alkylations of tetrazole 5, which bears a bulkier tert-butyl substituent, proceeded with lower diastereoselectivity. The observation of lower diastereoselectivity with a larger remote substituent is opposite of what is observed in the alkylations of the analogous seven-membered-ring enolates.17 The alkylations of tetrazole 7 with a benzyl-protected hydroxyl group were moderately diastereoselective, but protection with a sterically larger silyl group led to higher diastereoselectivities.

Scheme 2. Scope of C4-substituted seven-membered-ring-fused tetrazoles.a,b.

aDiastereomeric ratios were determined by 13C{H} analysis of the crude reaction mixture.22 bIsolated yields of purified products. cReaction was performed on a 1.1 mmol scale.

The products of mono-alkylation could be alkylated a second time to afford compounds with quaternary stereocenters (Scheme 3). For example, the alkylation of α-methylated product trans-2a with allyl bromide afforded trans-2f as a single diastereomer. The other diastereomer, cis-2f, was synthesized by reversing the order of introduction of electrophiles. High diastereofacial selectivity was achieved with a remote phenyl substituent to afford diastereomerically pure products trans-4c and cis-4c. Remote substituents that were less effective at controlling the stereoselectivity of the first alkylation, such as a benzyloxy group, gave lower stereoselectivities for the second alkylation (trans-8c and cis-8c). As with the first alkylation, the allylation of a compound bearing a remote tert-butyldiphenylsilyloxy substituent (trans-10a) was completely diastereoselective, forming substituted tetrazole trans-12c.23 The alkylation of a cholesterol derivative with benzyl bromide afforded quaternary substituted tetrazole trans-13 with the same sense of high diastereoselectivity, which showcases the generality of stereoselectivity for the alkylations of substrates that bear C4 substituents.

Scheme 3. Diastereoselective syntheses of compounds with quaternary stereocenters.a,b.

aDiastereomeric ratios were determined by 13C{H} analysis of the crude reaction mixture.22 bIsolated yields of purified products.

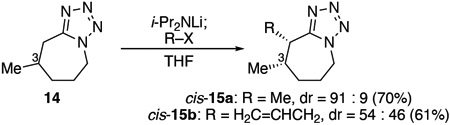

The stereoselectivities of alkylation depended upon the position of a substituent on the seven-membered ring. When a methyl group occupied the C3 position (eq 1), alkylation with iodomethane proceeded with high diastereoselectivity. The fact that the electrophile approached from the same face as the methyl group at C3 contrasts with the generally trans-selective reactions of similar cyclic enolates.17 This cis-selectivity suggests that torsional effects, not just steric effects, may be important in controlling diastereoselectivity. Alkylation with a larger electrophile, allyl bromide, led to complete erosion of diastereoselectivity, suggesting that steric factors might also play a role. Similar selectivity was observed with menthone derivative 16, which was alkylated with iodomethane to afford cis-17a (eq 2). Alkylations of substrates with a substituent at C5 (eq 3) were also cis-selective, regardless of the size of the electrophile. Diastereoselectivity was not observed when the methyl group was situated at the C6 position (eq 4). With a larger C6 substituent, modest stereoselectivity was achieved with a more hindered electrophile (eq 5).

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

|

(5) |

Computational methods were employed to probe the origin of diastereoselectivity in the α-alkylations of tetrazole-fused seven-membered-rings.24 Calculations on a reaction of a simplified model of the carbanion of C4-methyl substrate 1 revealed that delocalization of the carbanion in 24 forces C2, C1, and N7 into coplanarity, which causes the seven-membered ring to adopt a twist-chair conformation (Figure 1a). The twist-chair conformation observed for these intermediates differs from the geometries of the analogous seven-membered-ring enolates, which adopt chair conformations. The difference between chair and twist-chair conformations has a significant impact on the dihedral angles about the C2 and C3 substituents, which leads to the contrasting diastereoselectivities observed for the metalated tetrazoles and the corresponding enolates. A Newman projection looking down the C2─C3 bond of 24 reveals that electrophilic attack with methyl chloride from the β-face of the carbanion would lead to a compression of the torsional angles25-30 between the substituents on C2 and C3, whereas attack from the α-face should be accompanied by expansion of those same dihedral angles. Transition state calculations confirm this notion: in TS-24β, the dihedral angles between substituents at C2 and C3 become increasingly eclipsed, whereas in TS-24α, the same key dihedral angles are either expanded or unchanged (Figure 1b). These torsional strain differences in the transition states account for the relatively high ΔΔG‡, which was calculated to be 2.2 kcal/mol in favor of formation of the experimentally observed trans product.

Figure 1.

a) Geometry of resonance-stabilized carbanion 24. b) Newman projections looking down the C2─C3 bond of carbanion 24 and of transition states TS-24α and TS-24β.

The placement of the remote substituent on the seven-membered ring was also assessed with computational methods. Constrasteric alkylations of C3 substituted substrates can be rationalized by similar torsional strain arguments as the C4 case. The carbanion of the C3-methyl substrate, 25, adopts a similar twist-chair geometry as the C4-substituted carbanion 24, except in the case of 25 the torsionally favored approach, TS-25α, occurs from the same face of the remote methyl substituent (Figure 2). The disfavored transition state, TS-25β, is destabilized by accumulation of torsional strain, as evidenced by the small dihedral angles between the C2 and C3 substituents. The preference for the electrophile to approach the carbanion such that torsional strain is relieved, as in TS-25α, outweighs the destabilizing gauche interaction that develops between the incoming methyl group and the C3 methyl group. The sum of the torsional and steric factors account for the calculated ΔΔG‡ of 1.6 kcal/mol, which is in good agreement with the experimental results. Similarly, the C5 substituted carbanion adopts a conformation such that the methyl substituent occupies the face that is torsionally favored (Figure 3). Due to the remoteness of the C5 methyl group, and therefore the absence of a developing gauche interaction in the torsionally favored transition state, the calculated ΔΔG‡ was greater than in the C3 case (2.2 kcal/mol in favor of TS-26α over TS-26β).

Figure 2.

Twist-chair geometry of C3-substituted carbanion 25 and the C2─C3 Newman projections of TS-25α and TS-25β.

Figure 3.

Twist-chair geometry of C5-substituted carbanion 26 and the C2─C3 Newman projections of TS-26α and TS-26β.

In the case of the C6-substituted anion, two twist-chair carbanion conformers, 27 and 28, were found to be close in energy (ΔΔG0=0.2 kcal/mol), so the products are likely to be formed by multiple transition states. The torsionally favored transition states from each conformer, TS-27β and TS-28α, which lead to the cis and trans products, respectively, were found to be close in energy (ΔΔG‡ =0.6 kcal/mol, Figure 4). In TS-27β, the electrophile approaches from the same face as the pseudoaxial C6 methyl group, which leads to an increase in transannular steric repulsion in the transition state. TS-28α is destabilized by the A1,2 repulsion31 between the equatorial C6 methyl group and the tetrazole ring, although the approach of the electrophile is relatively unchanged compared to attack on TS-27β. When the C6 substituent is a methyl group, the magnitude of these destabilizing factors is similar, but with a tert-butyl substituent, the preference for alkylation to occur from the opposite face of the remote substituent is greater due to the larger size of the substituent.

Figure 4.

Geometries of C6-methyl carbanions 27 and 28 and their respective torsionally favored transition states of TS-27β and TS-28α.

Compounds bearing C2 quaternary stereocenters were sufficiently acidic at the C6-position to permit further functionalization (Scheme 4). The anions were formed at −78 °C with tert-butyllithium.32 Subsequent alkylations occurred with excellent stereoselectivity from the opposite face with respect to the remote C4 substituent.

Scheme 4. Diastereoselective C6 alkylations of C2 quaternary substitution products.a,b.

aDiastereomeric ratios were determined by 13C{H} analysis of the crude reaction mixture.22 bIsolated yields of purified products. cProduct was isolated with a rearranged byproduct. dReaction was performed on a 90:10 mixture of trans-8c and cis-8c. The reported diastereomeric ratio reflects the conversion of trans-8c to product.

The access to highly substituted tetrazoles provides a route to synthesize the corresponding diastereomerically enriched azepanes. Sequential treatment of phenyl tetrazole 3 with iodomethane and allyl bromide furnished α-quaternary tetrazole trans-4c as a single diastereomer. Subsequent reduction of the tetrazole ring with lithium triethylborohydride33 and methylation34 provided diastereomerically pure N-methyl azepane trans-32, albeit in low yield (eq 6). This strategy for the synthesis of 3,5-disubstituted azepanes provides a complementary approach to the synthesis that involves alkylating the corresponding seven-membered-ring lactam, which undergoes stereoselective α-alkylations from the opposite face (eq 7).17 In conclusion, the alkylations of anions derived from chiral seven-membered rings fused to tetrazoles are highly diastereoselective. Computational methods revealed that differences in torsional strain in the diastereomeric transition states account for the high diastereoselectivity. The diastereofacial preference was not altered in subsequent alkylations, which allowed for the controlled construction of quaternary stereocenters and for the introduction of an additional

|

(6) |

|

(7) |

stereocenter at the C6 position. The products of anionic functionalization, while potentially relevant medicinally, can also be reduced to the corresponding azepanes.14, 35

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of General Medical Sciences (1R01GM129286). The authors acknowledge New York University’s Shared Instrumentation Facility and the support provided by National Science Foundation Grant CHE-01162222 and NIH Grant S10-OD016343. The authors thank Dr. Chin Lin (New York University) and Dr. Chunhua (Tony) Hu (New York University) for their help with NMR and X-ray data, respectively.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

Full experimental details, computational details, and 1H and 13C spectra for new compounds (PDF)

Accession Codes

CCDC 2184100, 2184101, and 2184102 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif, or by emailing data_request@ccdc.cam.ac.uk, or by contacting The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; fax: + 44 1223 336033.

REFERENCES

- (1).Jones RN; Barry AL Cefoperazone: A Review of Its Antimicrobial Spectrum, β-Lactamase Stability, Enzyme Inhibition, and Other in Vitro Characteristics. Rev. Infect. Dis 1983, 5, 108–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Gardner CJ; Armour DR; Beattie DT; Gale JD; Hawcock AB; Kilpatrick GJ; Twissell DJ; Ward P GR205171: A Novel Antagonist with High Affinity for the Tachykinin NK1 Receptor, and Potent Broad-Spectrum Anti-Emetic Activity. Regul. Pept 1996, 65, 45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Nelson DW; Gregg RJ; Kort ME; Perez-Medrano A; Voight EA; Wang Y; Grayson G; Namovic MT; Donnelly-Roberts DL; Niforatos W; Honroe P; Jarvis MF; Faltynek CR; Carroll WA Structure-Activity Relationship Studies on a Series of Novel, Substituted 1-Benzyl-5-phenyltetrazole P2X7 Antagonists. J Med. Chem 2006, 49, 3659–3666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Staniszewska M; Gizińska M; Mikulak E; Adamus K; Koronkiewicz M; Łukowska-Chojnacka E New 1,5 and 2,5-Disubstituted Tetrazoles-Dependent Activity Towards Surface Barrier of Candida albicans. Eur. J. Med. Chem 2018, 145, 124–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Zabrocki J; Smith GD; Dunbar JB Jr.; Iijima H; Marshall GR Conformational Mimicry. 1. 1,5-Disubstituted Tetrazole Ring as a Surrogate for the Cis Amide Bond. J Am. Chem. Soc 1998, 110, 5875–5880. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Yu K-L; Johnson RL Synthesis and Chemical Properties of Tetrazole Peptide Analogues. J Org. Chem 1987, 52, 2051–2059. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Škorić ƉD; Klisurić OR; Jakimov DS; Sakać MN; Csanádi JJ Synthesis of New Bile Acid-Fused Tetrazoles Using the Schmidt Reaction. Beilstein J. Org. Chem 2021, 17, 2611–2620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Smith PAS The Schmidt Reaction: Experimental Conditions and Mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1948, 70, 320–323. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Motiwala HF; Charaschanya M; Day VW; Aubé J Remodeling and Enhancing Schmidt Reaction Pathways in Hexafluoroisopropanol. J. Org. Chem 2016, 81, 1593–1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Singh H; Chawla AS; Kapoor VK; Paul D; Malhotra RK Medicinal Chemistry of Tetrazoles. Prog. Med. Chem 1980, 17, 151–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Stone WE Convulsant Actions of Tetrazole Derivatives. Pharmacology 1970, 3, 367–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Gross EG; Featherstone RM Studies with Tetrazole Derivatives. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 1946, 291–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Lovering F; Bikker J; Humblet C Escape from Flatland: Increasing Saturation as an Approach to Improving Clinical Success. J. Med. Chem 2009, 52, 6752–6756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Barbero A; Diez-Varga A; Pulido FJ; González-Ortega A Synthesis of Azepane Derivatives by Silyl-aza-Prins Cyclization of Allylsilyl Amines: Influence of the Catalyst in the Outcome of the Reaction. Org. Lett 2016, 18, 1972–1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Ábrahámi RA; Kiss L; Barrio P; Fülöp F Synthesis of Fluorinated Piperidine and Azepane β-Amino Acid Derivatives. Tetrahedron 2016, 72, 7526–7535. [Google Scholar]

- (16).Cook GR; Shanker PS; Peterson SL Asymmetric Synthesis of the Balanol Heterocycle via a Palladium-Mediated Epimerization and Olefin Metathesis. Org. Lett 1999, 1, 615–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Lavinda O; Witt CH; Woerpel KA Origin of High Diastereoselectivity in Reactions of Seven-Membered-Ring Enolates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2022, e202114183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Beaver MG; Buscagan TM; Lavinda O; Woerpel KA Stereoelectronic Model To Explain Highly Stereoselective Reactions of Seven-Membered-Ring Oxocarbenium-Ion Intermediates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2016, 55, 1816–1819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).It was discovered through optimization of reaction conditions that 2.0 equiv of LDA and 4.0 equiv of electrophile were optimal for reactivity. Lower amounts of base and electrophile led to poor conversion and slow reaction times. Gem-dialkylation was never observed under the optimized reaction conditions.

- (20).Tert-butyllithium was used to prevent internal proton return (see Seebach D Structure and Reactivity of Lithium Enolates. From Pinacolone to Selective C-Alkylations of Peptides. Difficulties and Opportunities Afforded by Complex Structures. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. Engl 1988, 27, 1624–1654. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Details of stereochemical proofs are provided as Supporting Information.

- (22).Otte DA; Borchmann DE; Lin C; Weck M; Woerpel KA 13C NMR Spectroscopy for the Quantitative Determination of Compound Ratios and Polymer End Groups. Org. Lett 2014, 16, 1566–1569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).The synthesis of the other diastereomer by methylation of trans-12b was also diastereoselective, although it proceeded with low conversion and the product was not separable from the starting material by chromatography.

- (24).Calculations were performed using Gaussian 16 with a M06-2X functional and the 6-311+G(d,p) basis set with the SMD model for THF. Further details on calculations are supplied as Supporting Information.

- (25).Rondan NG; Paddon-Row MN; Caramella P; Mareda J; Mueller PH; Houk KN Origin of Huisgen's Factor “x”: Staggering of Allylic Bonds Promotes Anomalously Rapid Exo Attack on Norbornenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1982, 104, 4974–4976. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Wang H; Houk KN Torsional Control of Stereoselectivities in Electrophilic Additions and Cycloadditions to Alkenes. Chem. Sci 2014, 5, 462–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Cheong PH-Y; Yun H; Danishefsky SJ; Houk KN Torsional Steering Controls the Stereoselectivity of Epoxidation in the Guanacastepene A Synthesis. Org. Lett 2006, 8, 1513–1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Moon NG; Harned AM Torsional Steering as Friend and Foe: Development of a Synthetic Route to the Briarane Diterpenoid Stereotetrad. Org. Biomol. Chem 2017, 15, 1876–1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Volp KA; Harned AM Origin of Stereoselectivity of the Alkylation of Cyclohexadienone-Derived Bicyclic Malonates. J. Org. Chem 2013, 78, 7554–7564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Ando K; Green NS; Li Y; Houk KN Torsional and Steric Effects Control the Stereoselectivities of Alkylations of Pyrrolidinone Enolates. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1999, 121, 5334–5335. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Hoffmann RW Allylic 1,3-Strain as a Controlling Factor in Stereoselective Transformations. Chem. Rev 1989, 89, 1841–1860. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Moody CJ; Rees CW; Young RG Generation and Reactions of N-(α-Lithioalkyl)tetrazoles. J Chem. Soc Perkin Trans 1 1991, 323–327. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Duchamp E; Simard BD; Hanessian S Reductive Fragmentation of Tetrazoles: Mechanistic Insights and Applications toward the Stereocontrolled Synthesis of 2,6-Polysubstituted Morpholines. Org. Lett 2019, 21, 6593–6596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Clarke HT; Gillespie HB; Weisshaus SZ The Action of Formaldehyde on Amines and Amino Acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1933, 55, 4571–4587. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Kulanthaivel P; Hallock YF; Boros C; Hamilton SM; Janzen WP; Ballas LM; Loomis CR; Jiang JB Balanol: A Novel and Potent Inhibitor of Protein Kinase C from the Fungus Verticillium balanoides. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1993, 115, 6452–6453. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.