Abstract

Ferroptosis is a newly discovered type of cell-regulated death. It is characterized by the accumulation of iron-dependent lipid peroxidation and can be distinguished from other forms of cell-regulated death by different morphology, biochemistry, and genetics. Recently, studies have shown that ferroptosis is associated with a variety of diseases, including liver, kidney and neurological diseases, as well as cancer. Ferroptosis has been shown to be associated with colorectal epithelial disorders, which can lead to cancerous changes in the gut. However, the potential role of ferroptosis in the occurrence and development of colorectal cancer (CRC) is still controversial. To elucidate the underlying mechanisms of ferroptosis in CRC, this article systematically reviews ferroptosis, and its cellular functions in CRC, for furthering the understanding of the pathogenesis of CRC to aid clinical treatment.

Keywords: Ferroptosis, Colorectal cancer, Cell death, Therapy

Core Tip: Ferroptosis, a novel type of cell-regulated death, has diverse roles in the occurrence and development of colorectal cancers (CRCs). This article reviews the cellular functions of ferroptosis in CRC, providing potential therapeutic targets and treatment strategies for patients with CRC.

INTRODUCTION

Regulated cell death, including apoptosis, necroptosis, pyroptosis, ferroptosis, autophagy-dependent cell death, netotic cell death, and other forms, is an important mechanism for regulating the internal environment of the human body, and maintaining tissue function and morphology[1,2]. Ferroptosis, which was formally proposed in 2012, is a unique form of death that depends on the disorder of iron metabolism and accumulation of lipid reactive oxygen species (ROS). It differs from other forms of regulated cell death in terms of morphology, biochemical characteristics, and gene expression[2]. Especially in terms of morphology, ferroptosis involves unique mitochondrial alterations, concerning mitochondrial morphological disorder, membrane potential change, iron overload in the membrane and lipid ROS accumulation, that are different from other death forms[3]. The underlying mechanisms and pathways involved in ferroptosis include glutathione peroxidase/glutathione (GPx/GSH), system Xc- and p53 regulatory pathways. Usually, the pathways involved in ferroptosis ultimately regulate ROS accumulation through iron accumulation[2,4,5]. At present, the inhibitory effect of ferroptosis on tumor formation and development has been increasingly gaining attention, and its discovery has led to important progress in the diagnosis and treatment of tumors, as well as prognosis.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a malignant tumor of the digestive system and is associated with high morbidity and mortality. According to the 2018 GLOBOCAN assessment of global morbidity and mortality, CRC is the third most diagnosed cancer and the second leading cause of cancer-related death globally[6], and is characterized by multiple steps and stages during progression[7]. Currently, treatments for CRC patients include surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy and biological targeted therapy[8]. However, due to the lack of highly specific biomarkers and the complex biological characteristics of CRC, the lack of drugs targeting colorectal stem cells, and chemoresistance or intolerance to current treatment methods continue to hamper treatment[9,10]. Ferroptosis, as a form of regulated cell death independent of other forms of cell death, could provide an effective strategy for CRC treatment. In addition, a large number of recent studies have shown that ferroptosis-related genes can be used to predict the prognosis of patients with CRC, which is of great significance for improving the clinical efficacy of cancer treatment and the survival of patients[11-13].

THE MOLECULAR MECHANISM OF FERROPTOSIS

Discovery of ferroptosis

Erastin, a compound with the ability to kill tumor cells expressing high levels of the Ras oncogene, was discovered to induce a novel cell-death form that differed from apoptosis in terms of nuclear morphology, DNA fragmentation and caspase 3 activation[3,14,15]. Although the form of cell-death induced by erastin was not well elucidated at that time, other Ras-selective-lethal compounds (RSLs), such as RSL3 and RSL5, have been shown to trigger the same process, accompanied by increases in ROS levels that could be suppressed by iron chelators[3,16].

Ras protein, encoded by the well-known RAS oncogene, binds guanosine 5'-diphosphate (GDP)/ guanosine 5'-triphosphate (GTP) and possesses intrinsic GTPase activity[17]. Mutation of Ras is related to the loss of GTPase activity, providing a possible therapeutic strategy of recovering Ras GTPase function in RAS-mutant cancer cells as an effective means to combat cancer[18]. Based on previous findings, Dixon et al[2] defined the unique non-apoptotic cell death caused by erastin and RSLs as ferroptosis[2]. Ferroptosis, an iron-dependent form of cell death, is characterized by increases in intracellular ROS, but is distinguished morphologically, biochemically and genetically from other regulated cell death forms, such as apoptosis, necrosis and autophagy, in ways that will be specifically described in the following sections. Since the proposal of the concept of ferroptosis, the mechanism of ferroptosis has become an area of intense research, leading to progress in the study of anti-cancer drugs focused on ROS homeostasis.

The molecular mechanism of ferroptosis

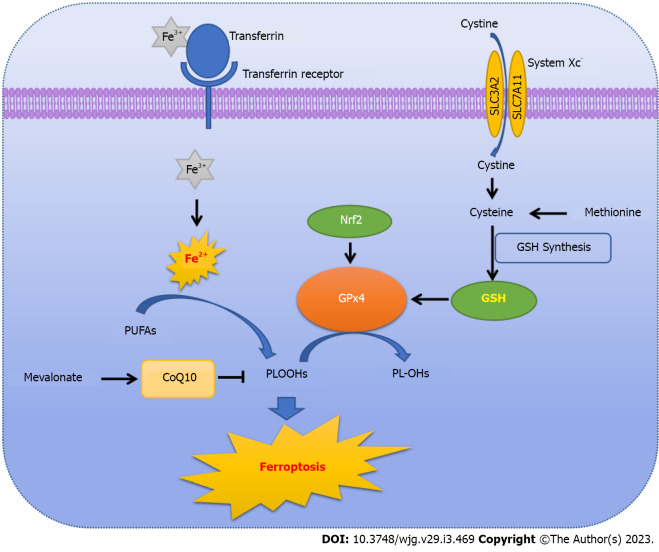

The imbalance between production and degradation of intracellular lipid ROS is the central mechanism of ferroptosis-mediated cell death[2,19]. If the antioxidant capacity of cells is decreased, excessive iron will initiate ferroptosis by producing lethal ROS via the Fenton reaction and cause ROS accumulation accordingly[2,5]. In addition, GSH depletion is also important for the induction of ferroptosis and subsequent nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH)-dependent lipid peroxidation[5]. Thus, intracellular ROS accumulation due to iron excess is the key for initiating ferroptosis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The schematic diagram of ferroptosis. PUFAs: Polyunsaturated fatty acids; PLOOHs: Phospholipid hydroperoxides; GSH: Glutathione; Nrf2: Nuclear factor erythroid2-related factor 2; GPx4: Glutathione peroxidase 4.

No matter whether using erastin or RSL, the induced ferroptosis is related to iron-dependent accumulation of ROS. In the normal intracellular environment, lipid oxidation and reduction are in a state of dynamic equilibrium. When cellular homeostasis is disrupted, gene expression related to lipid oxidation is up-regulated or that related to lipid reduction is inhibited, causing a high accumulation of intracellular oxidized lipid[20]. However, the sources of ROS are still unclear. Hassannia et al[21] pointed out that peroxidation of phospholipids containing polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in cell membranes could also lead to ferroptosis[21]. During induction of ferroptosis, PUFAs can form phospholipid hydroperoxides (PLOOHs) through enzymatic or non-enzymatic oxidation reactions. PLOOHs combined with intracellular iron will generate toxic lipid free radicals, such as alkoxy radicals, causing cell damage. Furthermore, these free radicals can extract protons from adjacent PUFAs, initiating a new round of lipid oxidation and delivering further oxidative damage[21,22]. Overall, ROS-mediated cell lipid damage is required for ferroptosis.

Obviously, intracellular iron plays a vital role during the process of ferroptosis, involving the absorption and reduction processes of iron[23]. Iron ingested in food is mainly absorbed, into the blood, as the ferric (Fe3+) form in the duodenum and upper jejunum, and transferred by plasma transferrin into cells, where it is converted to the reduced ferrous (Fe2+) form by metalloreductases in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Fe2+ is the main form of iron that participates in metabolic processes. Therefore, inhibition of iron absorption and reduction, such as silencing transferrin receptor expression, could inhibit erastin-induced ferroptosis, whereas the elevation of heme catabolism or iron supplementation could restore and accelerate ferroptosis[24-26].

Generally, Fe2+ is transported into cells and stored as ferritin to protect cells from iron toxicity[27]. In order to exert biological activity, Fe2+ has to be released into the active iron pool in the cytoplasm via iron pump solute carrier family 11 member 2/divalent metal transporter 1 (SLC11A2/DMT1), while the extra Fe2+ will either be recycled or stored as ferritin[28,29]. Up-regulation of ferritin gene expression restricts iron overload, whereas knockout of the SLC11A3 gene, which blocks iron transport out of the cells, aggravates erastin-induced ferroptosis in neuroma cells[30-32]. In the case of iron deficiency, ferritin is degraded by autophagy through the ATG5-ATG7-nuclear receptor coactivator 4 (NCOA4) signaling pathway, where NCOA4 binds to and transports ferritin to the lysosome, releasing Fe2+ to abnormally increase the labile iron pool. Subsequently, through the Fenton reaction, excess hydroxyl and peroxy radicals can be generated to initiate ferroptosis. Deletion of ATG5, ATG7 or NCOA4 will prevent erastin-induced ferroptosis by limiting ferritin degradation and reducing intracellular ferrous iron levels[33-35].

Signaling pathways involved in ferroptosis

The previous findings show that the key link causing ferroptosis involves increased lipid peroxidation and accumulation of ROS. Generally, the ferroptotic upstream pathways ultimately affect the activity of GPx directly or indirectly[4,36,37]. Consequently, GPx family members play an indispensable role in the process of ferroptosis. Among the 8 GPx family members, GPX4, a selenoprotein that inhibits lipid oxidation, has been shown to be the main regulator of ferroptosis[38].

GPX4, a selenoprotein capable of degrading small molecular peroxides and relatively complex lipid peroxides, is also able of reducing cytotoxic lipid hydroperoxides to non-toxic lipid alcohols, preventing the formation and accumulation of lethal ROS[39,40]. Knocking down GPX4 with siRNA results in cell sensitivity to ferroptosis, whereas up-regulating GPX4 induces resistance to ferroptosis[4,36,37]. In fact, RSL3, noted above as an important ferroptotic inducer, can directly suppress the activity of GPX4, thereby inducing ferroptosis[2,41,42]. The selenocysteine active site of GPX4 is covalently bound by RSL3, resulting in reduced cellular antioxidant capacity, increased lipid ROS and initiation of ferroptosis[2,4,43].

Additionally, the biosynthesis of GPX4 occurs through the mevalonate (MVA) pathway via interfering with the maturation of selenocysteine tRNAs[43,44]. Selenocysteine is one of the amino acids in the active center of GPX4, and its insertion into GPX4 requires a special selenocysteine tRNA. Isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP), a product of the MVA pathway, facilitates the maturation of selenocysteine tRNA by transferring an isopentenyl group to a selenocysteine tRNA precursor through isopentenyltransferase. Importantly, the MVA pathway influences the synthesis of selenocysteine by down-regulating IPP to further disrupt the activity of GPX4, finally causing ferroptosis[45]. Statins, such as cerivastatin, inhibit the MVA pathway and restrict GPX4 biosynthesis[43,44]. Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10), an endogenous antioxidant produced by the MVA pathway, protects cells from ferroptosis by preventing lipid oxidation[4,37]. Recently, Hadian et al[46] implicated ferroptosis-suppressor protein 1 (FSP1) as a novel ferroptosis resistance factor that reduces the expression of CoQ10, leading to the accumulation of lipid peroxides in a process independent of the cysteine/GSH/GPX4 pathway[46].

GSH, a tripeptide antioxidant composed of glutamate, cysteine and glycine[47,48], is an essential cofactor for GPX4 to degrade hydroperoxide[49]. Yant et al[50] found that GSH depletion is an indirect way of inactivating GPX4, which further causes a reduction in cellular antioxidant capacity, and increases accumulation of lipid ROS and subsequent ferroptosis[50]. Overall, hindering the synthesis and absorption of GSH or accelerating its degradation provides another means to induce ferroptosis. For example, erastin can block the absorption of GSH by inhibiting system Xc- to initiate ferroptosis[23]. System Xc- is a heterodimer composed of solute carrier family 3 member 2 (SLC3A2) and solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11), embedded in the cell surface membrane. SLC7A11 is the main functional subunit, which can transport cystine into cells, reduce it to cysteine in the cytoplasm, and incorporate it in the synthesis of GSH[51-54]. Interestingly, inhibiting system Xc- results in compensatory transcriptional upregulation of SLC7A11 in erastin- and sulfasalazine-induced ferroptosis[54-56]. When system Xc- is restrained, the absorption of cystine will be hindered, decreasing the synthesis of intracellular GSH, which will interfere with the biological activity of GPX4[22]. Finally, erastin obstructs the absorption of GSH by inhibiting system Xc-. However, GSH is a necessary cofactor for GPx, so the activity of GPx wanes and eventually results in cell ferroptosis[23]. Nevertheless, ferroptosis inducers that negatively regulate system Xc- are not effective in killing cells, since the cysteine involved in GSH synthesis can also be synthesized from methionine via trans-sulfation. Hayano et al[57] showed that inhibition of cysteine tRNA synthetase expression activates the trans-sulfuration pathway, further reducing cellular sensitivity to ferroptosis-inducing agents[57]. In addition, β-mercaptoethanol is able to promote cystine uptake without system Xc-, thus significantly inhibiting erastin- and glutamate-induced cell death[58].

Another factor involved in ferroptosis is p53, as an important tumor suppressor encoded by TP53 gene, which is mutated or inactivated in more than half of human cancers[59]. A large number of studies have shown that the tumor suppressing capacity of p53 is mainly derived from its typical functions, such as inducing cell cycle arrest, senescence, or apoptosis[60]. However, p53 also regulates metabolism, metastasis and invasion, and stem cell processes[61]. Recently, atypical functions of p53, such as controlling metabolism and redox status, have also been demonstrated to inhibit tumor development via regulating ferroptosis[62,63]. To verify whether p53 could induce ferroptosis, Jiang et al[56] showed treatment of p53-mutant non-small cell lung cancer cells with ROS had no significant effect on cell proliferation. However, following re-activation of p53, treatment with ROS dramatically induced 90% cell death, indicating that activation of p53 could dramatically reduce the antioxidant capacity of tumor cells[56]. Under the same conditions, addition of ferrostatin-1, an iron-death inhibitor, reduced the ROS-induced the cell death to 40%, indicating prevention of ROS-induced p53-dependent ferroptosis.

Under circumstances of oxidative stress, p53 can induce ferroptosis by transcriptional inhibition of SLC7A11, thereby inhibiting the absorption of cystine and reducing the production of GSH to enhance the sensitivity of cells to ferroptosis[56,64]. It is worth mentioning that acetylation of the p53 DNA-binding domain plays a key role in the regulation of SLC7A11 expression[56,65]. Notably, mice harboring p53 (3KR), an acetylation-defective p53 due to a lysine-to-arginine mutation, did not form tumors spontaneously, suggesting that p53 (3KR) cells lose their typical functions of inducing apoptosis, senescence, and cell cycle arrest[15], but retain the ability to regulate SLC7A11 expression. This finding highlights the ability of p53 to restrain tumorigenesis by means of inhibiting SLC7A11 expression and triggering ferroptosis[15,56].

Moreover, p53 could promote ferroptosis through regulating its target genes, such as glutaminase 2 (GLS2), prostaglandin endoperoxidase synthetase 2, and spermidine/spermine N1 acetyltransferase 1 (SAT1)[4,56,66,67]. For example, SAT1 enhances the activity of arachidonic acid (AA) and oxidizes PUFAs, thus promoting lipid peroxidation. Knockout of SAT1 will reduce p53-mediated ferroptosis whereas overexpression of SAT1 has the opposite effect[66].

Thus, depending on the p53 mutation status and cellular environment, p53 can promote or inhibit ferroptosis in response to different oxidative stress scenarios[68]. Under high oxidative stress, p53 will promote ferroptosis, while under basal or low ROS stress, it can prevent ferroptosis[69]. On the one hand, activation of the p53-p21 transcriptional pathway enables wild-type p53 to inhibit cysteine deprivation and systemic Xc- inhibition in cancer cell lines[70], which may help normal cells survive under various metabolic stress conditions. By binding to dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4) in the nucleus, p53 can prevent the interaction of DPP4 with NADPH oxidase (NOX) in the cytoplasm, and then reduce the accumulation of intracytoplasmic lipid peroxides, thereby inhibiting ferroptosis. This results in p53-WT CRCs being resistant to erastin-induced ferroptosis[71].

Initiation of cystine deprivation-induced ferroptosis requires glutaminolysis[67]. To prevent glutamine hydrolysis and resist ferroptosis, it is possible to restrict the uptake of glutamine by inhibiting the SLC1A5 transporter, inhibit glutamine metabolism to glutamate by mitochondrial GLS2, or deter glutamate synthesis to α-ketoglutarate by aspartate aminotransferase 1[67,72].

FSP1, a novel GSH-independent ferroptosis suppressor, suppresses CoQ10-mediated ferroptosis through an FSP1-CoQ10-NAD(P)H pathway, in a parallel manner to GPX4[73,74]. NADPH, normally used as a biomarker of iron-death inducer sensitivity, is a GSH reductase that maintains reduced GSH[75]. NOX, an enzyme complex that produces superoxide anions and oxidative radicals by consuming NADPH, mediates cellular oxidation to provide an important source of oxidative radicals[2]. Overexpression of NOX causes depletion of intracellular NADPH and increases the level of oxidative free radicals, which significantly raises the sensitivity of cells to ferroptosis. In contrast, NOX inhibitors can down-regulate NOX expression, thereby inhibiting erastin-induced ferroptosis[76].

FERROPTOSIS, A NON-APOPTOTIC CELL DEATH, IS ASSOCIATED WITH MITOCHONDRIAL ALTERATIONS

The characteristics of ferroptosis, compared with other forms of cell death

Ferroptosis, a form of cell death that is different from apoptosis, necrosis and autophagy, depends on the accumulation of lipid ROS, resulting in a redox imbalance. To investigate the differences between ferroptosis and other forms of cell death in morphology, biochemical characteristics, gene expression, and bioenergetics, Dixon et al[2] used different inducers to individually induce apoptosis, necrosis and autophagy, and found that, following erastin-induced ferroptosis, cells did not show the morphological characteristics associated with apoptosis (chromatin condensation, plasma membrane blebbing, unique apoptotic bodies), necrosis (cytoplasmic and organelle swelling, cell rupture, cytoskeleton disintegration) or autophagy (formation of a classic closed bilayer structure)[2,14]. Notably, mitochondrial alterations, including small mitochondria, increased membrane density, and mitochondrial outer membrane disruption detected in erastin-treated cells, are unique features that distinguish ferroptosis from other forms of cell death[77-79].

Also, the biochemical characteristics of ferroptosis differ from other forms of cell death. During ferroptosis, Fe2+ and ROS accumulate, the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) system is activated, and the uptake of cystine is reduced, resulting in an inhibitory effect on the Xc- system. At the same time, this process increases the activity of NOX and promotes the release of mediators, such as AA[1]. Regarding bioenergetics, a large reduction in intracellular ATP is found in H2O2-treated, but not in erastin-, STS-, or rapamycin-treated cells[2]. Regarding the characteristics of gene expression in the ferroptosis process, the intracellular Ras/Raf/MAPK and cystine transport pathways, and the activities of acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4), NADPH oxidase 1 (NOX1), GPX4, and SLC7A11 were all involved in ferroptosis, which is one of the differences between erastin-induced ferroptosis and other forms of cell death[2].

To investigate the effect of existing cell death inhibitors on erastin-induced ferroptosis, Dixon et al[2] used a regulatory assay strategy to test 12 cell death inhibitors for their ability to prevent ferroptosis in cells, and found that compounds confirmed to inhibit apoptosis, necrosis, and autophagy were unable to modulate erastin-induced ferroptosis[2]. In contrast, other compounds, such as the iron chelator deferoxamine (DFO), the antioxidant Trolox, a MEK inhibitor, and the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide, conversely were able to alleviate ferroptosis[3], demonstrating that these compounds are involved in ROS production and exert a preventive effect on ferroptosis[2].

Unique features of ferroptosis: Mitochondrial alterations

As mentioned above, mitochondrial morphological changes are the most significant feature of ferroptosis compared to other forms of cell death. Dixon et al[2] investigated the potential combination of erastin and the voltage-dependent anion channel 2/3 (VDAC2/3) on the mitochondrial membrane by affinity purification, demonstrating that VDAC2 and VDAC3 were necessary but not sufficient for erastin-induced cell death, which also suggests that mitochondria may be involved in the regulation of ferroptosis[3]. Under transmission electron microscopy, it was obvious that the number of mitochondria decreased and bilayer density increased in erastin induced BJeLR cells[2]. Mitochondrial swelling and mitochondrial crests decreased or disappeared in GPX4 ablated cells, and mitochondrial outer membranes rupture in RSL3 exposed Pfa1 cells in a time-dependent manner[37]. These abnormal mitochondrial structural changes are considered to be unique morphological features of ferroptosis[5]. In addition, the latest studies from Dr. Xuejun Jiang's laboratory have shown that cystine starvation-induced ROS accumulation and ferroptosis can be blocked by mitochondrial electron transport chain inhibitors, such as mitochondrial decoupling CCCP with mitochondrial membrane potential disruption[72]. However, in GPX4 knockout-induced ferroptosis, these electron transport chain inhibitors were unable to produce the blocking effect described above[37].

It is well known that iron overload and ROS accumulation are critical processes of ferroptosis in cells, and may be related to their induction of mitochondrial damage[80,81]. Iron overload would lead to mitochondrial morphological abnormalities, limit mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and antioxidant reactions, and impair mitochondrial function. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) double-strand breaks, reduced mtDNA transcription, and decreased expression of respiratory chain subunits encoded by the mitochondrial genome have been observed in iron-overloaded mitochondria[82-85], whereas preserving mitochondrial structure and function protects cells from iron toxicity[86]. In addition, Carsten Culmsee and colleagues found a sharp increase in mitochondrial ROS in erastin-[87] and RSL3-treated[88] HT-22 and MEF cells, but not in erastin treated HT-1080 cells. Thus, the researchers speculated that the difference could be due to the use of different cells or different exposure times. The mitochondrial targeting ROS scavenger MitoQ (mito-quinone) prevents neuronal cells from undergoing RSL3-induced ferroptosis[88]. Other studies have indicated that lipid ROS accumulates in the mitochondria rather than the cytoplasm[89], while some reports suggest that ferroptosis is caused by lipid peroxidation outside the mitochondria[37].

In general, according to existing studies, the structural integrity of mitochondria becomes damaged, membrane potential is altered, and abnormal iron metabolism and lipid peroxidation have varying degrees of influence on mitochondrial function. However, the alterations in mitochondrial structure and function in ferroptosis still requires further exploration and verification.

The surefire way to ferroptosis: Lipid peroxidation

Based on lipomics analysis, polyphosphorylated phosphatidylethanolamines (PEs) have been found to be key components in the induction of ferroptosis[90,91]. ACSL4, a key enzyme regulating lipid composition, catalyzes the addition of coenzyme A to AA and adrenic acid (AdA) to form PUFA coenzyme derivatives AA-CoA and AdA-CoA through an ER-associated oxygenation center. Subsequently, AA-CoA and AdA-CoA are esterified to AA-PE and AdA-PE by lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3 (LPCAT3) to take part in the synthesis of membrane phospholipids with negative charge[91-94]. In this situation, downregulation of ACSL4 for better conversion of AA to acylated AA, or inactivation of LPCAT3 to catalyze the insertion of acylated AA into membrane phospholipids, are also effective approaches to induce resistance to ferroptosis[90-92,95].

Additionally, free PUFAs such as AA-PE and AdA-PE will be selected as the preferred substrates for lipoxygenases (LOXs), lipid peroxidizing enzymes that catalyze the peroxidation of unsaturated fatty acids[96]. Knocking out LOX expression or treatment of cells with both tocotrienols and tocopherols have become an effective means to reduce erastin-induced ferroptosis[97,98]. With such treatment, LOX binds to phosphatidylethanolamine-binding protein 1 (PEBP1) to form a 15-LOX/PEBP1 complex that oxidizes AA-PE and AdA-PE to lipid hydroperoxides, thereby co-regulating the oxidation and reduction of esterified fatty acids with recombinant GPX4[99,100].

Recently, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), a well-known transcription factor, was found to be involved in the antioxidant process by inducing many antioxidant enzymes with antioxidant response elements in their promoters, such as GPX4 and GSH reductase, and its activity is strictly controlled by Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1)[101]. Under normal conditions, the binding of Nrf2 to KEAP1 causes the degradation and inactivation of Nrf2. However, when in a state of oxidative stress or with a large number of electrophiles, Nrf2 is released from the KEAP1 binding site and rapidly enters the nucleus to balance oxidative stress by activating transcriptional pathways and maintaining cellular redox homeostasis, ultimately inhibiting cellular oxidation and ferroptosis[74,102].

FERROPTOSIS PARTICIPATES IN TUMOR OCCURRENCE AND PROGRESSION

Ferroptosis and the tumor microenvironment

Ferroptosis can either inhibit or enhance tumorigenesis and development, with enhancement depending on the release of damage-associated molecular patterns in the tumor microenvironment (TME) and the inhibition of anti-tumor immune mechanisms, and inhibition depending on the activation of immune responses triggered by ferroptosis injury[103]. Therefore, understanding the interaction between ferroptosis and TME could provide new and effective anti-cancer strategies[104].

The TME is a complex environment within the tumor and enables tumor cells to survive and develop, serving as the ‘soil’ for non-cancerous cells (including stromal cells, immune cells, adipocytes, and endothelial cells) and extracellular matrix[105]. Theoretically, changes in tumor cytogenetics and epigenetics could enhance the ability of cancer cells to evade immune surveillance through various metabolic and biochemical mechanisms, ultimately promoting tumor initiation, progression, and metastasis[106]. Recently, Dai et al[107] found that ferroptosis caused by autophagic degradation releases cancer cells into TME and drives tumor-associated macrophage (TAM) polarization[107]. Yet ferroptosis inducers, such as erastin, RSL3 and sulfasalazine, have the capability to induce ferroptosis in cancer cells through different pathways, thus exerting anti-cancer effects, indicating the diverse role of ferroptosis in the process of cancer.

The regulatory effects of ferroptosis in malignancies

Erastin-induced cell death can be inhibited by antioxidants and iron chelators, suggesting that erastin-triggers cell death via ferroptosis related to the accumulation of ROS and iron[2,3]. The reduced GSH levels caused by erastin results from direct inhibition of the Xc- system, activating the ER stress response, and attenuating the antioxidant effect of GPX4/GSH, thereby accelerating the accumulation of ROS in the cytoplasm[42]. Sulfasalazine, another inducer of ferroptosis, has the same mechanism and function as erastin[108]. Thus, treatment with sulfasalazine also induces ferroptosis in cancer cells[2,42]. Activation of the RAF/MEK/ERK signaling pathway also appears to be an important factor in erastin-treated cells with high Ras expression[3]. As mentioned before, changes in mitochondrial structure and morphology are detected in cells following treatment with erastin, which binds to the mitochondrial VDAC[3].

Other inducers of ferroptosis, such as RSL3 and ferroptosis-inducing agents (FINs), are also associated with ROS accumulation. RSL3, a direct inhibitor of GPX4, can inactivate GPX4 through direct binding, resulting in the accumulation of intracellular lipid peroxides and ferroptosis[4]. FINs, with the ability to generate ROS, are classified into two types according to their mechanism of action[109,110]. Class I FINs share the same mechanism as erastin and sulfasalazine, inducing GSH depletion[111,112]. Class II FINs, similar to RSL3, directly inhibit the activity of GPX4 without depleting GSH[4]. Yang et al[4] showed that GPX4 overexpression and knockdown modulated the lethality of 12 ferroptosis inducers, but not of 11 compounds that induced cell death by other mechanisms[4].

Nevertheless, erastin- and RSL3-induced ferroptosis could be inhibited by ferrostatin, a lipophilic iron chelator[2]. Ferrostatin can cross the cell membrane and chelate free intracellular iron, or act directly on enzymes containing iron, to prevent the formation of iron-catalyzed lipid free radicals and inhibit the degradation of PUFAs. Lipoxygenase can be directly inactivated by iron chelators and thus most likely mediates iron-dependent lipid ROS formation[113]. Unlike lipophilic iron chelators, DFO is a non-membrane-permeable chelator that can accumulate on cell lysosomes, following endocytosis, and interact with iron in lysosomes to prevent the generation of lipid ROS[113-115]. Liproxstatin-1, a clinical drug, acts by preventing the accumulation of ROS and cell death in GPX4-/- cells[37]. More importantly, liproxstatin-1 is able to inhibit FIN-induced ferroptosis in vitro[37].

MECHANISMS OF FERROPTOSIS IN CRC

Signaling pathways of ferroptosis involved in CRC

GPX4 is a key factor in the regulation of ferroptosis. Molecules that inhibit GPX4 activity, either directly or indirectly, are involved in ferroptosis. RSL3, a confirmed ferroptosis-inducer, has anti-cancer effects in CRC that can be enhanced by aspirin through suppressing mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR)/sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBP-1)/stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 (SCD1)-mediated lipogenesis in PIK3CA-mutant CRC[116]. Not surprisingly, genetic ablation of SREBP-1 or SCD1 expression enhances CRC cell sensitivity to RSL3-induced ferroptosis, supporting the molecular mechanism of aspirin on RSL3-induced cytotoxicity[116].

In addition, reducing the synthesis of intracellular GSH by inhibiting SLC7A11, which is also the target of erastin and sulfasalazine, is also an effective way to induce ferroptosis in CRC[117]. 2-Imino-6-methoxy-2H-chromene-3-carbothioamide, a benzopyran derivative, has also been reported to have anti-cancer activity and was first discovered to exert ferroptotic anti-CRC activity through down-regulating SLC7A11 expression in the AMP-activated protein kinase/mTOR/p70S6K pathway in CRC[118].

Importantly, cancer stem cell (CSC)-regulated phenotypic plasticity and protection of metastasized cancer cells from lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis are related to the increased expression of SLC7A11[119]. In CRC, a remarkably low level of ROS is found in colorectal CSCs high in cysteine, GSH and SLC7A11 compared with CRC cells, while targeting SLC7A11 could induce ferroptosis through specifically suppressing the progression of colorectal CSC. Erastin exerts a dramatically strong cytotoxic effect on colorectal CSCs in vitro and in vivo[120]. By comparing the stemness of CRC cells and drug-resistant cells, it was found that the higher the stemness of CRC tumors, the more obvious the anti-ferroptosis characteristics. Correspondingly, the higher the stemness of CRC, the higher the expression of SLC7A11, suggesting that SLC7A11 is a potential target for colorectal CSC resistance to ferroptosis[120,121]. Knockdown of SLC7A11 expression in CSCs induced down-regulation of ALDH1, and tumor sphere size, as well as decreased cysteine and GSH and increased ROS levels, indicating decreased tumor stemness and increased ferroptotic characteristics. Similar results were obtained with erastin treatment, suggesting that erastin can effectively induce ferroptosis in drug-resistant CRC cells, thus achieving a therapeutic effect by targeting drug-resistant CSCs[120,121], providing a potential solution for drug resistance in CRC.

Doll et al[91] performed a genome-wide CRISPR-based genetic screen and microarray analysis of ferroptosis-resistant cell lines, and identified ACSL4 as an essential component for the synthesis of PE and execution of ferroptosis[91]. Another study analyzed the signaling pathway and miRNA profile of Kras mutant human CRC cells, and found that ACSL4 expression is high in CRC cells. Bromelain, a plant extract derived from pineapple, stimulated the expression of ACSL4, induced the cells to undergo ferroptosis and inhibited tumor progression[122], suggesting that the Kras gene may be an upstream regulator of ferroptosis.

TP53, an important tumor suppressor, plays a tumor suppressor role through transcriptional or non-transcriptional mechanisms in cancer cells[71]. In CRC cells, wild-type p53 restrains ferroptosis by blocking DPP4 activity, while deletion of wild-type p53 increases the anti-cancer activity of erastin in tumor-bearing mice[71]. In the nucleus, wild-type p53 binds to DPP4, preventing the translocation of DPP4 from the nucleus to the cytoplasm and the formation of the DPP4-NOX1 complex, responsible for preventing lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis, thereby restoring erastin-induced sensitivity in CRC cells[64,71]. On the contrary, p53 can also stimulate the expression of SLC7A11 in CRC, thereby protecting CRC cells from ferroptosis[71]. Therefore, it is desirable to modulate p53 to achieve efficacy in future CRC treatments.

Although ferroptosis is markedly different from other forms of cell death, there is a link between them in CRC. Hong et al[123] treated cancer cells with a combination of an apoptotic agent [tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)] and ferroptotic agents (erastin or artesunate) and found molecular crosstalk between ferroptosis and apoptosis[123]. The combined treatment remarkably promoted TRAIL-induced apoptosis due to the expression of ER stress-induced p53-independent up-regulation of apoptosis regulator PUMA. Further experiments found that the ER stress-response mediated by death receptor 5, one of the TRAIL receptors, also plays a significant role in the combined synergistic cytotoxic effect on multiple cell lines[124]. On the other hand, iron autophagy promotes ferroptosis in various types of cancer cells through regulating NCOA4, and inhibition of ferritin degradation inhibits the ferroptosis of these cells[31,35]. Interestingly, knockdown of NCOA4 did not change the ferroptosis of CRC cells[125], which could be explained by cell line differences or NCOA4 functional compensation, but further studies are needed.

Recent progress in CRC ferroptosis

In addition to the classical pathways mentioned above, mechanistic studies on ferroptosis in CRC are also increasing. A recent study revealed TP53-induced glycolysis and apoptosis regulator (TIGAR) to be a potential inhibitor of ferroptosis during CRC development[126]. TIGAR is highly expressed in CRC cell lines, and knockdown of TIGAR unexpectedly increases erastin-induced growth inhibition and death, indicating that low levels of TIGAR increase the sensitivity of CRC cells to erastin-induced ferroptosis and that TIGAR is a potential negative regulator of ferroptosis. Increased levels of lipid peroxidation and malondialdehyde are associated with knockdown of TIGAR in CRC, without obvious changes of iron level, suggesting TIGAR is a potential target for iron-death-based therapy for CRC through regulating ROS[126]. Similarly, cytoglobin (CYGB), a regulator of ROS, has been shown to be an inhibitor of ferroptosis via the p53-YAP1 pathway. In the same study, CYGB suppression, first shown in CRC, promoted ROS production and increased the sensitivity of cancer cells to RSL3- and erastin-induced ferroptosis, thus inhibiting the growth of CRC cells in a YAP1-dependent manner[126].

As GPX4 also plays crucial roles in ferroptosis, factors regulating GPX4 are predicted to be involved in the regulation of ferroptosis. Lipocalin-2 (LCN2), a protein siderophore that regulates iron homeostasis, is upregulated in several types of tumors, including CRC. Overexpression of LCN2 reduces the level of ferroptosis through reducing intracellular iron levels and stimulating the expression of GPX4 and system Xc-[127]. Serine and arginine rich splicing factor 9 was identified as a key factor promoting GPX4 expression and correspondingly decreased lipid peroxide damage, thereby driving CRC tumorigenesis, and thus providing another target for enhancing the sensitivity of CRC to erastin[128]. In addition, miR-15A-3p was found to positively regulate ferroptosis by directly targeting and suppressing GPX4 in CRC[129].

GTP cyclohydrolase 1 (GCH1), a rate-limiting enzyme in the synthesis of the free radical trapping antioxidant tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) was found to suppress ferroptosis in a GPX4-independent manner[130]. Blocking GCH1/BH4 promoted erastin-induced but not RSL3-induced ferroptosis, suggesting that GCH1 inhibitors combined with erastin provide a novel treatment strategy for CRC[130]. Interestingly, autophagy inhibitors could reverse erastin resistance in GCH1-knockdown cells, suggesting that GCH1/BH4 may act through ferritin phagocytosis[130]. Another novel inducer of ferroptosis, talaroconvolutin A was found to strongly induce ferroptosis in a dose- and time-dependent manner, but not apoptosis. Surprisingly, talaroconvolutin A was far more effective in inhibiting CRC by ferroptosis than erastin, and thus has become a potential treatment option for inducing ferroptosis in CRC[131].

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS OF FERROPTOSIS INDUCTION IN CANCER TREATMENT

Cancer remains one of the most threatening diseases to human health. Although traditional treatments, such as medication, surgery, radiation and chemotherapy, and comprehensive treatment, as well as immune therapy and targeted therapy, have been applied in the clinic, but the complexity of cancer pathogenesis, drug resistance, and patient intolerance have severely limited the efficacy of these approaches[132]. Therefore, further investigation is needed to explore the molecular changes and mechanisms involved in tumorigenesis and prognosis. Ferroptosis, a novel form of death, could play an indispensable role in inhibiting tumor growth and may therefore become an emerging strategy for anti-cancer therapy.

Reversing chemotherapeutic drug resistance

Chemotherapy has remained a necessary means to treat cancer, but drug resistance also remains one of the reasons for the poor prognosis of patients with malignancies. According to the molecular mechanism of ferroptosis, the pathways that reduce chemotherapeutic drug resistance are mainly involved in the lipid metabolism, iron metabolism and classical GPX4 pathways. The resistance of chemotherapeutic drugs in CRC also involves these processes.

In the process of lipid metabolism, ACSL4 is involved in the lipid oxidation pathway through the conversion of AA and AdA in PUFAs into coenzyme derivatives, and then producing oxidized lipid molecules[91]. Wu et al[133] reported that inhibiting ADP ribosylation factor 6 (ARF6), functions downstream of the Kras/ERK signaling pathway, and can activate ACSL4 and endow cancer cells with sensitivity to oxidative stress, especially RSL3-induced lipid peroxidation. ARF6 has a profound effect on the development of pancreatic cancer. Abrogation of ARF6 promotes RSL3-induced ferroptosis and alleviates gemcitabine resistance[133]. Another key enzyme in lipid metabolism, LOX, can directly oxidize PUFAs and mediate ferroptosis in a non-enzymatic manner[97]. Wu et al[134] demonstrated that arachidonate lipoxygenase 15 (ALOX15) is closely related to the inhibition of ferroptosis in gastric cancer. Decreasing miRNA-522 and increasing ALOX15, to induce ferroptosis, has become a novel treatment strategy to reverse drug resistance in gastric cancer, especially resistance to cisplatin/ paclitaxel[134].

In iron metabolic pathways, dihydroartemisinin (DHA), a safe and promising therapeutic agent that preferentially induces ferroptosis of cancer cells, was found to intensively enhance the cytotoxicity of cisplatin through impairing mitochondrial homeostasis and increasing mitochondrial-derived ROS, as well as promote ferroptosis with catastrophic accumulation of free iron and unrestricted lipid peroxidation. Depleting the free iron reservoir prevents death and triggers tolerance to DHA/cisplatin-induced ferroptosis, whereas supplementation of iron accelerates ferroptotic cell death[135]. Blocking lysosomal iron translocation out of lysosomes can be caused by the inhibition of DMT1 in CSC, resulting in iron accumulation in lysosomes, production of ROS and cell death in the form of ferroptosis[136].

Chen et al[137] discovered that androgen receptors could induce tumor cell drug resistance during the treatment of glioblastoma with temozolomide. Curcumin analogues reverse temozolomide resistance through ubiquitinating androgen receptors, which can be achieved by inhibition of GPX4 followed by induction of ferroptosis[137]. The reduction of oxaliplatin resistance in CRC occurs through a similar mechanism. CRCs induce ferroptosis by disrupting the KIF20A/NUAK1/PP1β/GPX4 pathway, in which high expression of KIF20A has been shown to be associated with oxaliplatin resistance[138]. In addition to the direct inhibition of GPX4 activity, blocking the synthesis of GSH also triggers ferroptosis indirectly. It is reported that ent-kaurane diterpenoids overcome cisplatin resistance by targeting peroxiredoxin I/II and consuming GSH to induce ferroptosis[139]. In head and neck cancer, cisplatin resistance can also be overcome by inhibiting system Xc-[140], and in gastric cancer, inhibition of the Nrf2/Keap1/system Xc- signaling pathway can induce the same effect[141].

Reversing targeted-therapy resistance

However, chemotherapy as a major means of cancer treatment has the undesirable side-effect of killing normal cells. In contrast, targeted therapy has gradually become an effective treatment. About half of patients with metastatic CRC have RAS mutations, which greatly limit the efficacy of cetuximab, an anti-epidermal growth factor receptor antibody. A natural product β-elemene, isolated from the Chinese herb turmeric, in combination with cetuximab, confers high cytotoxicity toward metastatic CRC cells with Kras mutations, and works by inducing ferroptosis and inhibiting epithelial-mesenchymal transition[9]. Olaparib, a well-known inhibitor of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase, promotes ferroptosis by inhibiting SLC7A11-mediated GSH synthesis. A synergistic effect with FINs can sensitize BRCA-activated ovarian cancer cells and xenograft cells[142]. Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) cells are resistant to clinical doses of gefitinib. Inhibition of GPX4 and induction of ferroptosis can enhance the sensitivity of TNBC to gefitinib[143]. Sorafenib is the first approved systemic medicine for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma, but acquired resistance limits its usefulness in the clinic. Inhibition of metallothionein-1g expression can enhance the anti-cancer activity of sorafenib by inducing ferroptosis in vitro and in vivo[144]. Artesunate, a drug derived from traditional Chinese medicine, inhibits the growth of sunitinib-resistant renal cell carcinoma by cell cycle arrest and induction of ferroptosis[145]. Similar to erastin, GSH depletion accompanied by GPx inactivation is the underlying mechanism of cisplatin, and cisplatin combined with erastin has enhanced anti-tumor activity compared to cisplatin alone[10]. The combination of erastin and cisplatin may be a useful strategy to improve the efficacy of cisplatin for the reason that the mechanisms used by these two compounds are different[10,146].

Reversing immunotherapy resistance

Over the past decade, immunotherapy with immune checkpoint inhibitors has shown promising efficacy in various malignancies. Even so, there has been some resistance to its use. Based on research advances, it has been proposed that stimulating the adaptive immune system by promoting immunogenic cell death may change the immune cold state into a checkpoint blockade response state, and ferroptosis happens to be immunogenic[147,148]. Therefore, induction of ferroptosis in cancer cells may induce vaccine-like effects and stimulate anti-tumor immunity, thereby overcoming immunotherapy resistance[149-151]. On the other hand, immunosuppressive cells in the TME also contribute to immunotherapy resistance, such as regulatory T cells (Tregs) and TAMs[152]. These findings suggest that induction of ferroptosis in Tregs by GPX4 inhibition may reverse immunotherapy resistance[153]. Moreover, Jiang et al[154] found that reprogramming of TAMs, due to in-tumor cell ferroptosis, resensitizes the tumor cells to immunotherapy[154].

CLINICAL PROGNOSTIC MODEL FOR FERROPTOSIS IN CRC

In recent years, numerous studies have focused on genetic screening for colon cancer and the establishment of polygenic prognostic models associated with ferroptosis. Owing to the lack of reliable and accurate biomarkers, the diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of colon cancer are faced with great challenges. Therefore, the establishment of a sound prognostic model and the mining of key biomarkers are effective ways to accurately predict the prognosis of CRC patients. In addition to their anti-cancer potential, ferroptosis-related genes also play an important role in the construction of prognostic models. Recent studies have shown that a new ferroptosis-related 10-gene prognostic model effectively predicts the prognosis and overall survival of patients with CRC, providing a reference value for targeted therapy and immunotherapy[11]. Xiang et al[12] established a prediction model based on regression analysis of CRC differentiation-related genes (CDRGs), and found that down-regulation of CDRGs was closely related to ferroptosis and immune metabolism, thus showing that molecular subtypes based on cell differentiation can successfully predict the prognosis of CRC patients undergoing chemotherapy and immunotherapy[12]. Moreover, a prognostic model based on EMT and ferroptosis-related genes predicted the ability of colorectal adenocarcinoma to invade and metastasize, where four genes involved in ferroptosis were potential prognostic biomarkers, thus providing important guidance for the individualized treatment and clinical decision-making of CRC[13]. Additionally, ferroptosis-related lncRNA signatures have proved to be promising biomarkers. Wu et al[155] constructed a robust prognostic model with only 4 ferroptosis-related lncRNA signatures, and the signature-based risk score showed a stronger ability to predict survival than traditional clinicopathological features, contributing to the prediction of clinical outcomes and treatment responses in patients with colon cancer[155] (Table 1). In future studies, the construction of CRC prognostic models and the discovery of potential biomarkers are expected to enhance and improve the survival and prognosis of CRC patients.

Table 1.

Prognostic model of ferroptosis-related genes in colorectal cancer patients

| Model |

Related genes |

Ref. |

| 10-Gene prognostic model | TFAP2C, SLC39A8, NOS2, HAMP, GDF15, FDFT1, CDKN2A, ALOX12, AKR1C1, ATP6V1G2 | [11] |

| Prediction model based on CDRG1 regression analysis | ACAA2, SRI, UGT2A3, KPNA2, MRPL37 | [12] |

| Prognostic model based on EMT1 and FRGs1 | MMP7, YAP1, PCOLCE, HOXC11 | [13] |

| Prognostic model of 4-FRL1 signatures | AP003555.1, AC104819.3, LINC02381, AC005841.1 | [155] |

CDRG: Colorectal cancer differentiation-related gene.

EMT: Epithelial-mesenchymal transition; FRG: Ferroptosis-related gene; FRL: Ferroptosis-related lncRNA.

CONCLUSION

In summary, ferroptosis mainly involves the accumulation of intracellular lipid ROS resulting from a disorder of iron metabolism[2]. Its unique form of death provides potential targets for the treatment of tumors. Since ferroptosis exerts different effects through different mechanisms in different tumor types, this article focuses on CRC to elaborate the molecular mechanisms and pathways of ferroptosis.

Many studies have proposed possible pathways of ferroptosis in CRC, but the specific mechanisms involved in the occurrence, development and metastasis of CRC remains unclear. In the classical pathway, GPX4 can be used as a target for tumor therapy, but the inhibition of GPX4 may cause side effects due to its protective role against β-amyloid toxicity in neurons[156,157]. Additionally, p53 has contradictory effects on ferroptosis, but the mechanism in CRC is unique. Future studies can explore how to achieve the switch between "brake" and "accelerator" in the regulation of ferroptosis[71]. Generally, the role of ferroptosis in disease may be to promote[158,159] or inhibit, but the induction of ferroptosis, undoubtedly, has an inhibitory effect on the occurrence, development and metastasis of CRC. In addition to the classical mechanism, other potential regulatory pathways need to be discovered. As mentioned above, these regulated types of cell death may share common pathways and key regulators, which could provide new directions for combined therapeutic interventions. Furthermore, the occurrence of ferroptosis is cell-type dependent, so cancer treatment based on ferroptosis will not necessarily be suitable for all cancer types, or even for different clinical stages of the same type. Although these treatments can be expected to be affected by the development of tumor cell drug resistance, with the gradual development of research, reducing drug resistance by inducing ferroptosis is gradually becoming a reality[10], and the construction of prognostic disease models by screening ferroptosis-related genes has become a focus of clinical research[13]. However, translating the multiple basic research discoveries in ferroptosis to clinical treatment will be another difficult problem we will soon face.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: October 14, 2022

First decision: November 17, 2022

Article in press: December 21, 2022

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chi HT, China; Feng S, China; Tzeng IS, Taiwan S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: A P-Editor: Fan JR

Contributor Information

Zheng Wu, Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory for Diagnosis and Treatment of Breast Cancer, Cancer Hospital of Shantou University Medical College, Shantou 515041, Guangdong Province, China.

Ze-Xuan Fang, Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory for Diagnosis and Treatment of Breast Cancer, Cancer Hospital of Shantou University Medical College, Shantou 515041, Guangdong Province, China.

Yan-Yu Hou, Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory for Diagnosis and Treatment of Breast Cancer, Cancer Hospital of Shantou University Medical College, Shantou 515041, Guangdong Province, China.

Bing-Xuan Wu, Department of General Surgery, First Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College, Shantou 515041, Guangdong Province, China.

Yu Deng, Department of General Surgery, First Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College, Shantou 515041, Guangdong Province, China.

Hua-Tao Wu, Department of General Surgery, First Affiliated Hospital of Shantou University Medical College, Shantou 515041, Guangdong Province, China.

Jing Liu, Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory for Diagnosis and Treatment of Breast Cancer, Cancer Hospital of Shantou University Medical College, Shantou 515041, Guangdong Province, China. jliu12@stu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Stockwell BR, Friedmann Angeli JP, Bayir H, Bush AI, Conrad M, Dixon SJ, Fulda S, Gascón S, Hatzios SK, Kagan VE, Noel K, Jiang X, Linkermann A, Murphy ME, Overholtzer M, Oyagi A, Pagnussat GC, Park J, Ran Q, Rosenfeld CS, Salnikow K, Tang D, Torti FM, Torti SV, Toyokuni S, Woerpel KA, Zhang DD. Ferroptosis: A Regulated Cell Death Nexus Linking Metabolism, Redox Biology, and Disease. Cell. 2017;171:273–285. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS, Morrison B 3rd, Stockwell BR. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell. 2012;149:1060–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yagoda N, von Rechenberg M, Zaganjor E, Bauer AJ, Yang WS, Fridman DJ, Wolpaw AJ, Smukste I, Peltier JM, Boniface JJ, Smith R, Lessnick SL, Sahasrabudhe S, Stockwell BR. RAS-RAF-MEK-dependent oxidative cell death involving voltage-dependent anion channels. Nature. 2007;447:864–868. doi: 10.1038/nature05859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang CZ, Ma J, Luo QQ, Neskey DM, Zhu DW, Liu Y, Myers JN, Zhang CP, Zhang ZY, Zhong LP. Elevated level of serum growth differentiation factor 15 is associated with oral leukoplakia and oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Pathol Med. 2014;43:28–34. doi: 10.1111/jop.12091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xie Y, Hou W, Song X, Yu Y, Huang J, Sun X, Kang R, Tang D. Ferroptosis: process and function. Cell Death Differ. 2016;23:369–379. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2015.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen L, Yang F, Chen S, Tai J. Mechanisms on chemotherapy resistance of colorectal cancer stem cells and research progress of reverse transformation: A mini-review. Front Med (Lausanne) 2022;9:995882. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.995882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benson AB, Venook AP, Al-Hawary MM, Cederquist L, Chen YJ, Ciombor KK, Cohen S, Cooper HS, Deming D, Engstrom PF, Garrido-Laguna I, Grem JL, Grothey A, Hochster HS, Hoffe S, Hunt S, Kamel A, Kirilcuk N, Krishnamurthi S, Messersmith WA, Meyerhardt J, Miller ED, Mulcahy MF, Murphy JD, Nurkin S, Saltz L, Sharma S, Shibata D, Skibber JM, Sofocleous CT, Stoffel EM, Stotsky-Himelfarb E, Willett CG, Wuthrick E, Gregory KM, Freedman-Cass DA. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Colon Cancer, Version 2.2018. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16:359–369. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2018.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen P, Li X, Zhang R, Liu S, Xiang Y, Zhang M, Chen X, Pan T, Yan L, Feng J, Duan T, Wang D, Chen B, Jin T, Wang W, Chen L, Huang X, Zhang W, Sun Y, Li G, Kong L, Li Y, Yang Z, Zhang Q, Zhuo L, Sui X, Xie T. Combinative treatment of β-elemene and cetuximab is sensitive to KRAS mutant colorectal cancer cells by inducing ferroptosis and inhibiting epithelial-mesenchymal transformation. Theranostics. 2020;10:5107–5119. doi: 10.7150/thno.44705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo J, Xu B, Han Q, Zhou H, Xia Y, Gong C, Dai X, Li Z, Wu G. Ferroptosis: A Novel Anti-tumor Action for Cisplatin. Cancer Res Treat. 2018;50:445–460. doi: 10.4143/crt.2016.572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shao Y, Jia H, Huang L, Li S, Wang C, Aikemu B, Yang G, Hong H, Yang X, Zhang S, Sun J, Zheng M. An Original Ferroptosis-Related Gene Signature Effectively Predicts the Prognosis and Clinical Status for Colorectal Cancer Patients. Front Oncol. 2021;11:711776. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.711776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xiang R, Fu J, Ge Y, Ren J, Song W, Fu T. Identification of Subtypes and a Prognostic Gene Signature in Colon Cancer Using Cell Differentiation Trajectories. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:705537. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.705537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi C, Xie Y, Li X, Li G, Liu W, Pei W, Liu J, Yu X, Liu T. Identification of Ferroptosis-Related Genes Signature Predicting the Efficiency of Invasion and Metastasis Ability in Colon Adenocarcinoma. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:815104. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.815104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dolma S, Lessnick SL, Hahn WC, Stockwell BR. Identification of genotype-selective antitumor agents using synthetic lethal chemical screening in engineered human tumor cells. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:285–296. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li T, Kon N, Jiang L, Tan M, Ludwig T, Zhao Y, Baer R, Gu W. Tumor suppression in the absence of p53-mediated cell-cycle arrest, apoptosis, and senescence. Cell. 2012;149:1269–1283. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang WS, Stockwell BR. Synthetic lethal screening identifies compounds activating iron-dependent, nonapoptotic cell death in oncogenic-RAS-harboring cancer cells. Chem Biol. 2008;15:234–245. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gremer L, Merbitz-Zahradnik T, Dvorsky R, Cirstea IC, Kratz CP, Zenker M, Wittinghofer A, Ahmadian MR. Germline KRAS mutations cause aberrant biochemical and physical properties leading to developmental disorders. Hum Mutat. 2011;32:33–43. doi: 10.1002/humu.21377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanada K, Kawada K, Nishikawa G, Toda K, Maekawa H, Nishikawa Y, Masui H, Hirata W, Okamoto M, Kiyasu Y, Honma S, Ogawa R, Mizuno R, Itatani Y, Miyoshi H, Sasazuki T, Shirasawa S, Taketo MM, Obama K, Sakai Y. Dual blockade of macropinocytosis and asparagine bioavailability shows synergistic anti-tumor effects on KRAS-mutant colorectal cancer. Cancer Lett. 2021;522:129–141. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2021.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu S, He Y, Lin L, Chen P, Chen M, Zhang S. The emerging role of ferroptosis in intestinal disease. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12:289. doi: 10.1038/s41419-021-03559-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xie B, Guo Y. Molecular mechanism of cell ferroptosis and research progress in regulation of ferroptosis by noncoding RNAs in tumor cells. Cell Death Discov. 2021;7:101. doi: 10.1038/s41420-021-00483-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hassannia B, Vandenabeele P, Vanden Berghe T. Targeting Ferroptosis to Iron Out Cancer. Cancer Cell. 2019;35:830–849. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dixon SJ, Stockwell BR. The role of iron and reactive oxygen species in cell death. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:9–17. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ning X, Qi H, Yuan Y, Li R, Wang Y, Lin Z, Yin Y. Identification of a new small molecule that initiates ferroptosis in cancer cells by inhibiting the system Xc(-) to deplete GSH. Eur J Pharmacol. 2022;934:175304. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2022.175304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gammella E, Recalcati S, Rybinska I, Buratti P, Cairo G. Iron-induced damage in cardiomyopathy: oxidative-dependent and independent mechanisms. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2015;2015:230182. doi: 10.1155/2015/230182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kwon MY, Park E, Lee SJ, Chung SW. Heme oxygenase-1 accelerates erastin-induced ferroptotic cell death. Oncotarget. 2015;6:24393–24403. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cao JY, Dixon SJ. Mechanisms of ferroptosis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73:2195–2209. doi: 10.1007/s00018-016-2194-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Y, Fan Z, Yang Y, Gu C. Iron metabolism and its contribution to cancer (Review) Int J Oncol. 2019;54:1143–1154. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2019.4720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang Y, Mikhael M, Xu D, Li Y, Soe-Lin S, Ning B, Li W, Nie G, Zhao Y, Ponka P. Lysosomal proteolysis is the primary degradation pathway for cytosolic ferritin and cytosolic ferritin degradation is necessary for iron exit. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;13:999–1009. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurz T, Eaton JW, Brunk UT. The role of lysosomes in iron metabolism and recycling. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2011;43:1686–1697. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Geng N, Shi BJ, Li SL, Zhong ZY, Li YC, Xua WL, Zhou H, Cai JH. Knockdown of ferroportin accelerates erastin-induced ferroptosis in neuroblastoma cells. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2018;22:3826–3836. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201806_15267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao M, Monian P, Pan Q, Zhang W, Xiang J, Jiang X. Ferroptosis is an autophagic cell death process. Cell Res. 2016;26:1021–1032. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Du J, Wang T, Li Y, Zhou Y, Wang X, Yu X, Ren X, An Y, Wu Y, Sun W, Fan W, Zhu Q, Wang Y, Tong X. DHA inhibits proliferation and induces ferroptosis of leukemia cells through autophagy dependent degradation of ferritin. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;131:356–369. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou B, Liu J, Kang R, Klionsky DJ, Kroemer G, Tang D. Ferroptosis is a type of autophagy-dependent cell death. Semin Cancer Biol. 2020;66:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2019.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mancias JD, Wang X, Gygi SP, Harper JW, Kimmelman AC. Quantitative proteomics identifies NCOA4 as the cargo receptor mediating ferritinophagy. Nature. 2014;509:105–109. doi: 10.1038/nature13148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hou W, Xie Y, Song X, Sun X, Lotze MT, Zeh HJ 3rd, Kang R, Tang D. Autophagy promotes ferroptosis by degradation of ferritin. Autophagy. 2016;12:1425–1428. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2016.1187366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liang C, Zhang X, Yang M, Dong X. Recent Progress in Ferroptosis Inducers for Cancer Therapy. Adv Mater. 2019;31:e1904197. doi: 10.1002/adma.201904197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Friedmann Angeli JP, Schneider M, Proneth B, Tyurina YY, Tyurin VA, Hammond VJ, Herbach N, Aichler M, Walch A, Eggenhofer E, Basavarajappa D, Rådmark O, Kobayashi S, Seibt T, Beck H, Neff F, Esposito I, Wanke R, Förster H, Yefremova O, Heinrichmeyer M, Bornkamm GW, Geissler EK, Thomas SB, Stockwell BR, O'Donnell VB, Kagan VE, Schick JA, Conrad M. Inactivation of the ferroptosis regulator Gpx4 triggers acute renal failure in mice. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:1180–1191. doi: 10.1038/ncb3064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tong J, Li D, Meng H, Sun D, Lan X, Ni M, Ma J, Zeng F, Sun S, Fu J, Li G, Ji Q, Zhang G, Shen Q, Wang Y, Zhu J, Zhao Y, Wang X, Liu Y, Ouyang S, Sheng C, Shen F, Wang P. Targeting a novel inducible GPX4 alternative isoform to alleviate ferroptosis and treat metabolic-associated fatty liver disease. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022;12:3650–3666. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2022.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ursini F, Maiorino M, Valente M, Ferri L, Gregolin C. Purification from pig liver of a protein which protects liposomes and biomembranes from peroxidative degradation and exhibits glutathione peroxidase activity on phosphatidylcholine hydroperoxides. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1982;710:197–211. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(82)90150-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brigelius-Flohé R, Maiorino M. Glutathione peroxidases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1830:3289–3303. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hirschhorn T, Stockwell BR. The development of the concept of ferroptosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;133:130–143. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dixon SJ, Patel DN, Welsch M, Skouta R, Lee ED, Hayano M, Thomas AG, Gleason CE, Tatonetti NP, Slusher BS, Stockwell BR. Pharmacological inhibition of cystine-glutamate exchange induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and ferroptosis. Elife. 2014;3:e02523. doi: 10.7554/eLife.02523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang WS, Stockwell BR. Ferroptosis: Death by Lipid Peroxidation. Trends Cell Biol. 2016;26:165–176. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Friedmann Angeli JP, Conrad M. Selenium and GPX4, a vital symbiosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2018;127:153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu H, Guo P, Xie X, Wang Y, Chen G. Ferroptosis, a new form of cell death, and its relationships with tumourous diseases. J Cell Mol Med. 2017;21:648–657. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.13008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hadian K. Ferroptosis Suppressor Protein 1 (FSP1) and Coenzyme Q(10) Cooperatively Suppress Ferroptosis. Biochemistry. 2020;59:637–638. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.0c00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ursini F, Maiorino M. Lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis: The role of GSH and GPx4. Free Radic Biol Med. 2020;152:175–185. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2020.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu SC. Glutathione synthesis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1830:3143–3153. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lu SC. Regulation of glutathione synthesis. Mol Aspects Med. 2009;30:42–59. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2008.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yant LJ, Ran Q, Rao L, Van Remmen H, Shibatani T, Belter JG, Motta L, Richardson A, Prolla TA. The selenoprotein GPX4 is essential for mouse development and protects from radiation and oxidative damage insults. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;34:496–502. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01360-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sato H, Tamba M, Ishii T, Bannai S. Cloning and expression of a plasma membrane cystine/glutamate exchange transporter composed of two distinct proteins. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:11455–11458. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McBean GJ. The transsulfuration pathway: a source of cysteine for glutathione in astrocytes. Amino Acids. 2012;42:199–205. doi: 10.1007/s00726-011-0864-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen L, Li X, Liu L, Yu B, Xue Y, Liu Y. Erastin sensitizes glioblastoma cells to temozolomide by restraining xCT and cystathionine-γ-lyase function. Oncol Rep. 2015;33:1465–1474. doi: 10.3892/or.2015.3712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bridges RJ, Natale NR, Patel SA. System xc⁻ cystine/glutamate antiporter: an update on molecular pharmacology and roles within the CNS. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;165:20–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01480.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sun X, Ou Z, Chen R, Niu X, Chen D, Kang R, Tang D. Activation of the p62-Keap1-NRF2 pathway protects against ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Hepatology. 2016;63:173–184. doi: 10.1002/hep.28251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jiang L, Kon N, Li T, Wang SJ, Su T, Hibshoosh H, Baer R, Gu W. Ferroptosis as a p53-mediated activity during tumour suppression. Nature. 2015;520:57–62. doi: 10.1038/nature14344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hayano M, Yang WS, Corn CK, Pagano NC, Stockwell BR. Loss of cysteinyl-tRNA synthetase (CARS) induces the transsulfuration pathway and inhibits ferroptosis induced by cystine deprivation. Cell Death Differ. 2016;23:270–278. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2015.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xie Y, Song X, Sun X, Huang J, Zhong M, Lotze MT, Zeh HJ Rd, Kang R, Tang D. Identification of baicalein as a ferroptosis inhibitor by natural product library screening. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;473:775–780. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu C, Shen Z, Lu Y, Sun F, Shi H. p53 Promotes Ferroptosis in Macrophages Treated with Fe(3)O(4) Nanoparticles. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2022;14:42791–42803. doi: 10.1021/acsami.2c00707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Capuozzo M, Santorsola M, Bocchetti M, Perri F, Cascella M, Granata V, Celotto V, Gualillo O, Cossu AM, Nasti G, Caraglia M, Ottaiano A. p53: From Fundamental Biology to Clinical Applications in Cancer. Biology (Basel) 2022;11 doi: 10.3390/biology11091325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rodriguez-Ramirez C, Zhang Z, Warner KA, Herzog AE, Mantesso A, Yoon E, Wang S, Wicha MS, Nör JE. p53 Inhibits Bmi-1-driven Self-Renewal and Defines Salivary Gland Cancer Stemness. Clin Cancer Res. 2022;28:4757–4770. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-22-1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kaiser AM, Attardi LD. Deconstructing networks of p53-mediated tumor suppression in vivo. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25:93–103. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2017.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bieging KT, Mello SS, Attardi LD. Unravelling mechanisms of p53-mediated tumour suppression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:359–370. doi: 10.1038/nrc3711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang W, Gai C, Ding D, Wang F, Li W. Targeted p53 on Small-Molecules-Induced Ferroptosis in Cancers. Front Oncol. 2018;8:507. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang SJ, Li D, Ou Y, Jiang L, Chen Y, Zhao Y, Gu W. Acetylation Is Crucial for p53-Mediated Ferroptosis and Tumor Suppression. Cell Rep. 2016;17:366–373. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ou Y, Wang SJ, Li D, Chu B, Gu W. Activation of SAT1 engages polyamine metabolism with p53-mediated ferroptotic responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:E6806–E6812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1607152113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gao M, Monian P, Quadri N, Ramasamy R, Jiang X. Glutaminolysis and Transferrin Regulate Ferroptosis. Mol Cell. 2015;59:298–308. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gnanapradeepan K, Basu S, Barnoud T, Budina-Kolomets A, Kung CP, Murphy ME. The p53 Tumor Suppressor in the Control of Metabolism and Ferroptosis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018;9:124. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kruiswijk F, Labuschagne CF, Vousden KH. p53 in survival, death and metabolic health: a lifeguard with a licence to kill. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16:393–405. doi: 10.1038/nrm4007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tarangelo A, Magtanong L, Bieging-Rolett KT, Li Y, Ye J, Attardi LD, Dixon SJ. p53 Suppresses Metabolic Stress-Induced Ferroptosis in Cancer Cells. Cell Rep. 2018;22:569–575. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.12.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xie Y, Zhu S, Song X, Sun X, Fan Y, Liu J, Zhong M, Yuan H, Zhang L, Billiar TR, Lotze MT, Zeh HJ 3rd, Kang R, Kroemer G, Tang D. The Tumor Suppressor p53 Limits Ferroptosis by Blocking DPP4 Activity. Cell Rep. 2017;20:1692–1704. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gao M, Yi J, Zhu J, Minikes AM, Monian P, Thompson CB, Jiang X. Role of Mitochondria in Ferroptosis. Mol Cell. 2019;73:354–363.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Doll S, Freitas FP, Shah R, Aldrovandi M, da Silva MC, Ingold I, Goya Grocin A, Xavier da Silva TN, Panzilius E, Scheel CH, Mourão A, Buday K, Sato M, Wanninger J, Vignane T, Mohana V, Rehberg M, Flatley A, Schepers A, Kurz A, White D, Sauer M, Sattler M, Tate EW, Schmitz W, Schulze A, O'Donnell V, Proneth B, Popowicz GM, Pratt DA, Angeli JPF, Conrad M. FSP1 is a glutathione-independent ferroptosis suppressor. Nature. 2019;575:693–698. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1707-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dodson M, Castro-Portuguez R, Zhang DD. NRF2 plays a critical role in mitigating lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis. Redox Biol. 2019;23:101107. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2019.101107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shimada K, Hayano M, Pagano NC, Stockwell BR. Cell-Line Selectivity Improves the Predictive Power of Pharmacogenomic Analyses and Helps Identify NADPH as Biomarker for Ferroptosis Sensitivity. Cell Chem Biol. 2016;23:225–235. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dächert J, Ehrenfeld V, Habermann K, Dolgikh N, Fulda S. Targeting ferroptosis in rhabdomyosarcoma cells. Int J Cancer. 2020;146:510–520. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yuan Y, Yucai L, Lu L, Hui L, Yong P, Haiyang Y. Acrylamide induces ferroptosis in HSC-T6 cells by causing antioxidant imbalance of the XCT-GSH-GPX4 signaling and mitochondrial dysfunction. Toxicol Lett. 2022;368:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2022.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wu H, Wang F, Ta N, Zhang T, Gao W. The Multifaceted Regulation of Mitochondria in Ferroptosis. Life (Basel) 2021;11 doi: 10.3390/life11030222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Battaglia AM, Chirillo R, Aversa I, Sacco A, Costanzo F, Biamonte F. Ferroptosis and Cancer: Mitochondria Meet the "Iron Maiden" Cell Death. Cells. 2020;9 doi: 10.3390/cells9061505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bauckman KA, Haller E, Flores I, Nanjundan M. Iron modulates cell survival in a Ras- and MAPK-dependent manner in ovarian cells. Cell Death Dis. 2013;4:e592. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rouault TA. Mitochondrial iron overload: causes and consequences. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2016;38:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Walter PB, Knutson MD, Paler-Martinez A, Lee S, Xu Y, Viteri FE, Ames BN. Iron deficiency and iron excess damage mitochondria and mitochondrial DNA in rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:2264–2269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261708798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gao X, Campian JL, Qian M, Sun XF, Eaton JW. Mitochondrial DNA damage in iron overload. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:4767–4775. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806235200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Asín J, Pérez-Martos A, Fernández-Silva P, Montoya J, Andreu AL. Iron(II) induces changes in the conformation of mammalian mitochondrial DNA resulting in a reduction of its transcriptional rate. FEBS Lett. 2000;480:161–164. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)01768-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yaffee M, Walter P, Richter C, Müller M. Direct observation of iron-induced conformational changes of mitochondrial DNA by high-resolution field-emission in-lens scanning electron microscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:5341–5346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Park J, Lee DG, Kim B, Park SJ, Kim JH, Lee SR, Chang KT, Lee HS, Lee DS. Iron overload triggers mitochondrial fragmentation via calcineurin-sensitive signals in HT-22 hippocampal neuron cells. Toxicology. 2015;337:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2015.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Neitemeier S, Jelinek A, Laino V, Hoffmann L, Eisenbach I, Eying R, Ganjam GK, Dolga AM, Oppermann S, Culmsee C. BID links ferroptosis to mitochondrial cell death pathways. Redox Biol. 2017;12:558–570. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jelinek A, Heyder L, Daude M, Plessner M, Krippner S, Grosse R, Diederich WE, Culmsee C. Mitochondrial rescue prevents glutathione peroxidase-dependent ferroptosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2018;117:45–57. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dikalova AE, Bikineyeva AT, Budzyn K, Nazarewicz RR, McCann L, Lewis W, Harrison DG, Dikalov SI. Therapeutic targeting of mitochondrial superoxide in hypertension. Circ Res. 2010;107:106–116. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.214601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yuan H, Li X, Zhang X, Kang R, Tang D. Identification of ACSL4 as a biomarker and contributor of ferroptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2016;478:1338–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.08.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Doll S, Proneth B, Tyurina YY, Panzilius E, Kobayashi S, Ingold I, Irmler M, Beckers J, Aichler M, Walch A, Prokisch H, Trümbach D, Mao G, Qu F, Bayir H, Füllekrug J, Scheel CH, Wurst W, Schick JA, Kagan VE, Angeli JP, Conrad M. ACSL4 dictates ferroptosis sensitivity by shaping cellular lipid composition. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13:91–98. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]