Abstract

Clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa are classified into invasive and noninvasive (cytolytic) strains. In a noninvasive PA103 background, ExoS and ExoT have recently been shown to function as anti-internalization factors. However, these two factors seemed not to have such a function in an invasive strain PAK background. In this study, using HeLa tissue culture cells, we observed that the internalization of invasive strain PAK is dependent on its growth phases, with the stationary-phase cells internalized about 100-fold more efficiently than the exponential-phase cells. This growth phase-dependent internalization was not observed in the noninvasive PA103 strain. Further analysis of various mutant derivatives of the invasive PAK and the noninvasive PA103 strains demonstrated that ExoS or ExoT that is injected into host cells by a type III secretion machinery functions as an anti-internalization factor in both types of strains. In correlation with the growth phase-dependent internalization, the invasive strain PAK translocates much higher amount of ExoS and ExoT into HeLa cells when it is in an exponential-growth phase than when it is in a stationary-growth phase, whereas the translocation of ExoT by the noninvasive strain PA103 is consistently high regardless of the growth phases, suggesting a difference in the regulatory mechanism of type III secretion between the two types of strains. Consistent with the invasive phenotype of the parent strain, an internalized PAK derivative survived well within the HeLa cells, whereas the viability of internalized PA103 derivative was dramatically decreased and completely cleared within 48 h. These results indicate that the invasive strains of P. aeruginosa have evolved the mechanism of intracellular survival, whereas the noninvasive P. aeruginosa strains have lost or not acquired the ability to survive within the epithelial cells.

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic human pathogen that infects severe-burn patients and patients with leukemia, AIDS, cystic fibrosis, or cancer (2, 3, 28, 35). P. aeruginosa is capable of utilizing a wide variety of carbon and nitrogen sources, enabling it to grow and persist in diverse environments (26). P. aeruginosa is armed with many virulence factors such as proteases, cytotoxins, phospholipases, neuraminidase, capsular polysaccharides, and lipopolysaccharides, contributing to its ability to colonize, penetrate, and survive against host immune defense (9, 26, 35). Moreover, P. aeruginosa is intrinsically resistant and easily acquires resistance to antibiotics commonly used to treat bacterial infections (23). Furthermore, its ability to form biofilm enhances the bacterial resistance to various antimicrobial agents (1, 6). These characteristics make it difficult to avoid contamination by P. aeruginosa in the hospital setting and hard to cure once patients are infected with P. aeruginosa.

Clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa have been grouped into invasive and noninvasive (cytolytic) strains based on their interactions with nonphagocytic corneal epithelial cells (12). The invasive and noninvasive strains encode different sets of exoenzymes that are translocated into the host cells via a type III secretion machinery (15, 37). The noninvasive strains encode exoT and exoU genes, whereas the invasive strains encode exoT and exoS genes (39). Although 49-kDa ExoS and 53-kDa ExoT share 75% identity at the amino acid level, ExoT was shown to possess only 0.2% of ADP-ribosyltransferase activity of the ExoS in an in vitro assay (36). The ExoS preferentially ADP-ribosylates several Ras family of GTP-binding proteins that regulate intracellular vesicle transports, cell proliferations, and differentiations (4, 5). The ADP-ribosylating activity of the ExoS was also shown recently to cause apoptosis in various tissue culture cells (19). Both ExoS and ExoT also cause severe cell rounding by disrupting actin cytoskeleton in an ADP-ribosyltransferase activity-independent manner (16, 20, 27). Expressions of these exoenzymes are coordinately regulated by a transcriptional activator, ExsA, in response to various environmental signals, including low calcium and direct contact with tissue culture cells (11, 33, 36, 38).

P. aeruginosa strain PA103 is highly cytolytic and does not invade epithelial cells (12). Its cytolytic activity derives mainly from the function of the acute cytotoxin ExoU (11). An exoU mutant of PA103 is still noninvasive to the epithelial cells, indicating that the noninvasive is not caused by its high cytotoxicity (10, 17). Recently, ExoS and ExoT were reported to possess anti-internalization functions in the cytolytic PA103 background (7). However, the invasive P. aeruginosa strains are highly internalized into the epithelial cells despite the presence of both ExoS and ExoT (12). The mechanism for these differences has not been understood.

In this study, we demonstrate that the ExoS and ExoT function as anti-internalization factors in both the invasive strain PAK and the noninvasive strain PA103. We show that the internalization of invasive PAK is dependent on its growth phases, which correlates with the growth phase-dependent translocation of the ExoS and ExoT into HeLa cells. In addition, the internalized invasive PAK derivative stably persisted in the HeLa cells, whereas internalized noninvasive PA103 derivative was killed quickly. The implication of these findings to the P. aeruginosa pathogenesis is also discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. P. aeruginosa was grown in Luria (L) agar or L broth at 37°C. Antibiotics were used at a final concentration of 150 μg of carbenicillin, 200 μg of gentamicin, 200 μg of spectinomycin, 200 μg of streptomycin, and 100 μg of tetracycline per ml for P. aeruginosa and 100 μg of ampicillin, 5 μg of gentamicin, 50 μg of spectinomycin, 25 μg of streptomycin, and 20 μg of tetracycline per ml for Escherichia coli.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Descriptiona | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| P. aeruginosa | ||

| PAK | Clinical isolate of wild-type invasive strain | D. Bradley |

| PA103 | Clinical isolate of wild-type cytotoxic strain | 22 |

| PAKexsA | PAK with chromosomal disruption of the exsA locus; Spr Smr | 14 |

| PAKrpoS | PAK with chromosomal disruption of the rpoS locus; Spr Smr | This study |

| PAKfliC | PAK with chromosomal disruption of the fliC locus; Gmr | R. Ramphal |

| PAKexoS | PAK with chromosomal disruption of the exoS locus; Spr Smr | 19 |

| PAKexoSexoT | PAK with chromosomal disruption of the exoS and exoT loci; Spr Smr Gmr | 19 |

| PA103exoU | PA103 with chromosomal deletion of the exoU locus | 11 |

| PA103exoUexoT | PA103-ΔexoU with chromosomal disruption of the exoT locus; Tcr | 33 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCR2.1-TOPO | PCR cloning vector; Apr Kmr | Invitrogen |

| pDN19lacΩ | Promoterless lacZ fusion vector; Spr Smr Tcr | 32 |

| pFLAG-CTC | FLAG peptide fusion vector; Apr | Sigma |

| pHW0004 | exoT gene derived from PAK in pUCP18; Apr | This study |

| pHW0005 | PAK exoS promoter fused to promoterless lacZ in pDN19lacΩ; Spr Smr Tcr | This study |

| pHW0006 | PAK exoT promoter fused to promoterless lacZ in pDN19lacΩ; Spr Smr Tcr | This study |

| pHW0015 | exoS gene derived from PAK in pUCP18; Apr | This study |

| pHW0017 | exoT gene derived from PA103 in pUCP18; Apr | This study |

| pHW0018 | PA103 exoT promoter fused to promoterless lacZ in pDN19lacΩ; Spr Smr Tcr | This study |

| pHW0027 | exoT-FLAG of PAK in pUCP18; Apr | This study |

| pHW0028 | exoT-FLAG of PA103 in pUCP18; Apr | This study |

| pHW0029 | exoS-FLAG of PAK in pUCP18; Apr | This study |

| pUCP18 | Broad host range shuttle vector; Apr | 30 |

| pUCPexoS | exoS gene derived from 388 in pUCP18; Apr | 21 |

| pUCPexoT | exoT gene derived from 388 in pUCP18; Apr | 36 |

| pUCPexoSE381A | exoS of pUCPexoS mutated into E381A; Apr | 34 |

Phenotypes: Apr, ampicillin resistance marker; Kmr, kanamycin resistance marker; Gmr, gentamicin resistance marker; Spr, spectinomycin resistance marker; Smr, streptomycin resistance marker; Tcr, tetracycline resistance marker.

The exoS and exoT genes derived from PAK and PA103 were cloned following amplified by PCR. The oligonucleotides used to clone the exoS gene were exoS-1 (5′-CAG TTG TTC GAG TTG ATG GTG GAT CTG GGC CCT GT-3′) and exoS-2 (5′-CGT TTC GTC GCC TGG ACC TAC CTC GAC AAG AAG CA-3′). The oligonucleotides used to PCR clone the exoT genes were exoT-1 (5′-AGG AAG GTC ATC AGC AGG GCG ATC TCG GTG GTC AT-3′) and exoT-2 (5′-GCT GTA CGG CGC AAA TGA AAA CGG ACA CCC CTT GG-3′). The amplified DNA fragments were cloned into a PCR cloning vector, pCR2.1-TOPO, and recloned into a broad-host-range vector, pUCP18, to be transformed into P. aeruginosa. A 0.9-kb SmaI-KpnI fragment containing exoS promoter of PAK and 1.1-kb NruI-KpnI fragments containing exoT promoters of PAK and PA103 were fused to a promoterless lacZ in pDN19lacΩ vector, resulting transcriptional fusion constructs of pHW0005, pHW0006, and pHW0018, respectively, to monitor corresponding gene expression.

Construction of ExoS-FLAG and ExoT-FLAG fusion plasmids.

The exoS and exoT genes of PAK and PA103 were amplified by PCR using primers that generate BglII sites at 3′ ends which allowed in-frame fusions with the FLAG tag in C termini by cloning into the BglII site (AGATCT) of pFLAG-CTC. Oligonucleotides exoS-1 and exoS-4 (5′-TTA CGA CCG GTC ATG CCA GAT CTA AGG CCG CGC AT-3′) were used to amplify exoS, and oligonucleotides exoT-1 and exoT-4 (5′-CGG TCA GGC CAG ATC TGA GGC TGC GCA TTC TCA GG-3′) were used for exoT. PCR products were first cloned into pCR2.1-TOPO, and then the inserts were reisolated as EcoRI-BglII fragments for cloning into the C-terminal FLAG tag fusion vector pFLAG-CTC. Resulting plasmids were confirmed for in-frame fusions by sequencing and Western blot using anti-FLAG monoclonal antibody. The exoS-FLAG and exoT-FLAG clones were further isolated as HindIII-SspI and HindIII-ScaI fragments, respectively, and subcloned into the HindIII-SmaI sites of a shuttle vector pUCP18 for use in P. aeruginosa.

β-Galactosidase assay.

A standard β-galactosidase assay (25) was conducted to determine the transcriptional expression of exoS and exoT. For the HeLa cell contact-mediated expressions, exponential- and stationary-phase P. aeruginosa cells were harvested and suspended in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 5% of fetal calf serum (FCS) and 100 μg of tetracycline/ml. The suspensions were used to infect 4.0 × 105 of HeLa epithelial cells in six-well plates at the indicated multiplicity of infection (MOI). At 2 h postinfection at 37°C in 5% CO2, both surface-adhered and lifted HeLa cells were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and treated with 0.25% of Trypsin-EDTA solution to collect the adhered cells. The collected HeLa cells were suspended in Z buffer (25) for the β-galactosidase assay as well as for counting the number of viable bacterial cells by colony count. Overnight cultures of P. aeruginosa in L broth containing antibiotics was used as the stationary-phase bacterial cells, whereas 3-h subcultures of a 100-fold dilution of the stationary bacteria into fresh L broth with antibiotics was used as the exponential-phase bacterial cells.

Invasion assay.

A total of 4.0 × 105 HeLa S3 epithelial cells in 3 ml of DMEM containing 5% FCS were seeded into each of the six-well plates and incubated at 37°C in 5% of CO2 for 24 h. After two washes with PBS, 1 ml of DMEM containing 5% FCS was added to the HeLa cells, followed by the addition of 0.1 ml of bacterial suspension in DMEM, giving rise to an MOI of 10. The infected HeLa cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 2 h. After three washes with PBS, the cells were resuspended in 0.25% Triton-X100 and plated on L-agar plates containing appropriate antibiotics to count the number of bacteria associated with HeLa cells. To another set of the infected HeLa cells, 1 ml of DMEM containing 5% FCS and 400 μg of amikacin per ml was added and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 2 h. The cells were washed twice with PBS and lysed with 0.25% Triton X-100, and the suspension was plated as described above. To test intracellular survival, HeLa cells were infected with PAKexoSexoT mutant at an MOI of 10 or PA103exoUexoT mutant at an MOI of 100. After 2 h of incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2, the HeLa cells were washed and immersed in 2 ml of DMEM containing 5% FCS and 400 μg of amikacin per ml and then incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 2, 6, 12, 24, 36, 48, or 60 h. After two washes with PBS, the infected HeLa cells were lysed with 0.25% Triton X-100 and plated on L-agar plates containing appropriate antibiotics in order to count the number of bacterial cells.

Detection of ExoS and ExoT proteins translocated into HeLa cells.

A total of 3.0 × 106 HeLa S3 epithelial cells in 3 ml of DMEM containing 5% FCS were seeded in tissue culture dishes (60 by 15 mm), and the HeLa cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% of CO2 for 24 h. After two washes with PBS, the cells were immersed in 1 ml of DMEM containing 5% FCS, followed by addition of a 0.1-ml bacterial suspension in DMEM, resulting in an MOI of 10. The infected HeLa cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 2 h. After three washes with PBS, the cells were collected by cell scrapers and spun at 1,000 × g for 5 min to pellet the HeLa cells. The HeLa cells were lysed with 0.25% Triton X-100 and spun at 13,000 rpm for 2 min. Pellets were suspended in 1 ml of PBS and used to count the number of bacterial cells by colony count. Proteins were precipitated from the supernatant by the addition of trichloroacetic acid (TCA) to final concentration of 15%. After incubation at 4°C for 2 h, protein precipitates were collected by spinning at 13,000 rpm for 5 min and washing with acetone. The samples were suspended in 1× protein loading buffer for sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blot analysis.

Other methods.

Standard methods were used for plasmid DNA preparation, restriction enzyme digestion, and cloning (29). DNA sequence analysis was performed by PCR-mediated Taq DyeDeoxy Terminator Cycle sequence using an Applied Biosystems model 373A DNA sequencer. DNA restriction enzyme sites and open reading frame analyses were conducted using the DNA Strider program. Southern hybridizations were carried out using the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) labeling and detection kit from Amersham. For Western hybridizations, a monoclonal antibody against FLAG peptide from Sigma and an anti-mouse immunoglobulin conjugated with horseradish peroxidase were used with the ECL labeling and detection kit from Amersham.

RESULTS

Growth phase-dependent internalization of invasive strain PAK.

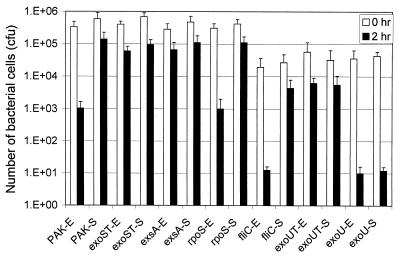

While studying apoptosis caused by invasive strains of P. aeruginosa, we observed that the growth phases of the bacterial cells seem to affect their ability to cause apoptosis as well as invasion. To confirm the effect of bacterial growth phases on the internalization of P. aeruginosa into HeLa cells, an invasive strain PAK was grown in L broth to the exponential or stationary phase and subjected to invasion assay by infecting HeLa cells (see Materials and Methods). As shown in Fig. 1, PAK cells in stationary-growth phase internalized into the HeLa cells about 100-fold more efficiently than that in exponential phase, although bacterial binding abilities to HeLa cells were the same. We tested if the stationary-phase-specific sigma factor RpoS is required for the higher invasion rate of the stationary-phase cells. Invasion test of the rpoS mutant strain, PAKrpoS, showed a pattern of growth phase-dependent internalization similar to that of the wild-type PAK, indicating that RpoS is not required for the bacterial invasion. However, when a type III null mutant strain PAKexsA was used in the invasion assay, it was internalized at a high rate without being affected by its growth phases, indicating that the low invasion rate seen with exponential-phase cells is a type III secretion-dependent phenomenon. Furthermore, the high invasion rate seen with stationary-phase cells is independent of type III secretion.

FIG. 1.

Growth phase-dependent internalizations of P. aeruginosa into HeLa epithelial cells. Exponential (E)- and stationary (S)-phase bacterial cells were used to infect HeLa S3 cells at an MOI of 10 and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 2 h. After three washes with PBS, the bacteria associated with the HeLa cells were plated with serial dilutions for the colony count (open bars). Another set of infected HeLa cells was incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 2 h in the presence of amikacin to kill extracellular bacteria, and the number of intracellular bacteria was calculated from the colony count (solid bars). PAK, an invasive wild-type strain; exsA, type III mutant strain PAKexsA; rpoS, rpoS mutant strain PAKrpoS; fliC, flagellum structural gene mutant strain PAKfliC; exoUT, exoU and exoT double mutant of PA103, PA103exoUexoT; exoU, exoU mutant of PA103, PA103exoU; exoST, exoS and exoT double mutant of PAK, PAKexoSexoT. Average values from three repeated tests are shown.

An exoU mutant strain of PA103, PA103exoU, internalized poorly in both the exponential- and the stationary-growth phases, whereas an exoU exoT double mutant, PA103exoUexoT, internalized at a high rate regardless of the growth phases (Fig. 1). These results indicated that the internalization of cytolytic PA103 is not affected by the growth phases and that ExoT indeed functions as an anti-internalization factor as reported previously (7). The binding capacity of the PA103exoU to the HeLa cells was about 10-fold less than the invasive PAK which is 10% of the input bacteria. This is likely due to the fact that PA103 strain is a genuine nonmotile bacterium due to a defect in flagella. Consistent with this prediction, a nonflagellated mutant of PAK, PAKfliC, showed a level of decrease in binding to the HeLa cells similar to that of PA103 (1% of input bacteria), but its internalization rate remained the same as wild-type PAK (10% of bound bacteria) (Fig. 1), indicating that a defect in the flagella affects binding to the HeLa cells but does not affect the growth phase-dependent internalization.

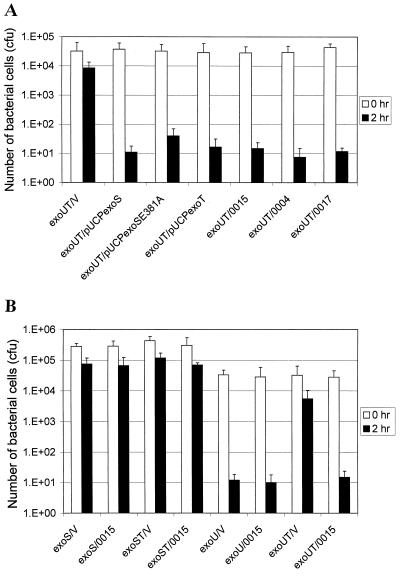

Anti-internalization functions of ExoS and ExoT.

The ExoS and ExoT were shown to block the uptake of noninvasive P. aeruginosa PA103 into epithelial cells (7). However, the stationary-phase PAK is highly internalized into HeLa cells despite the presence of both ExoS and ExoT. We determined whether the anti-internalization functions of ExoS and ExoT derived from PAK differ from ExoT of PA103. The exoS and exoT of PAK, as well as exoT of PA103, were cloned and transformed into a PA103exoUexoT double mutant background which is highly invasive and encodes no exoenzymes. In addition, we also used exoS (in pUCPexoS), exoSE381A (in pUCPexoSE381A), and exoT (in pUCPexoT) of 388 to compare the anti-internalization functions with the exoenzymes of PAK. As shown in Fig. 2A, PA103exoUexoT complemented with any of the exoS or exoT clones resulted in an almost 1,000-fold decrease in the invasion rate compared to the mutant complemented with a vector. These results suggested that there is no significant difference in anti-internalization activities among the three exoenzymes derived from invasive and cytolytic strains; therefore, the high internalization of invasive PAK in the stationary phase is not due to low anti-internalization activities of its ExoS or ExoT. Furthermore, the ADP-ribosylating activity is not required for the anti-internalization activity of the ExoS.

FIG. 2.

Anti-internalization functions of ExoS and ExoT in a PA103 background. Stationary-phase bacteria were used to infect HeLa S3 cells and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 2 h. After three washes with PBS, the number of bacteria associated with the HeLa cells were counted (open bars). Another set of the infected HeLa cells was incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 2 h in the presence of amikacin to kill extracellular bacteria, and the number of intracellular bacteria was counted (solid bars). (A) Anti-internalization functions of ExoS and ExoT derived from PAK, 388, and PA103. exoUT, PA103exoUexoT double mutant; V, pUCP18 vector; pUCPexoS, encoding the exoS gene of strain 388; pUCPexoSE381A, encoding the exoS gene mutated at E381A; pUCPexoT, encoding the exoT gene of strain 388; 0004, pHW0004 encoding the exoT gene of PAK; 0015, pHW0015 encoding the exoS gene of PAK; 0017, pHW0017 encoding the exoT gene of PA103. (B) Interference tests between ExoS and ExoT for their anti-internalization functions. exoS, PAKexoS mutant; exoST, PAKexoSexoT double mutant; exoU, PA103exoU mutant; exoUT, PA103exoUexoT double mutant; V, pUCP18 vector; 0015, pHW0015 encoding exoS gene of PAK. Average values from three repeated tests are shown.

Since the invasive strain PAK encodes both ExoS and ExoT, whereas PA103 encodes ExoT only, we next tested if the ExoS and ExoT interfere with each other's anti-internalization function. To test this, we compared the invasion rates of PAKexoS(pUCP18) that encodes only exoT, PAKexoS(pHW0015) that encodes both exoS and exoT, and PAKexoSexoT(pHW0015) that encodes only exoS. As shown in Fig. 2B, these three mutant strains showed a growth phase-dependent invasion phenotype similar to that of the wild-type PAK, suggesting that there is no interference between ExoS and ExoT. This is further supported by the observation that PA103exoU(pHW0015), which encodes both exoS and exoT, is as poorly invasive as PA103exoU(pUCP18), which encodes exoT only, and PA103exoUexoT(pHW0015), which encodes exoS only. Thus, the high invasion rate of stationary-phase PAK is not due to interference between the ExoS and ExoT. Interestingly, an exoS and exoT double mutant of PAK, PAKexoSexoT, showed a high invasion rate both in exponential and in stationary phases (Fig. 1), suggesting that the ExoS and ExoT are responsible for the low invasion rate of the exponential-phase cells of invasive strain PAK.

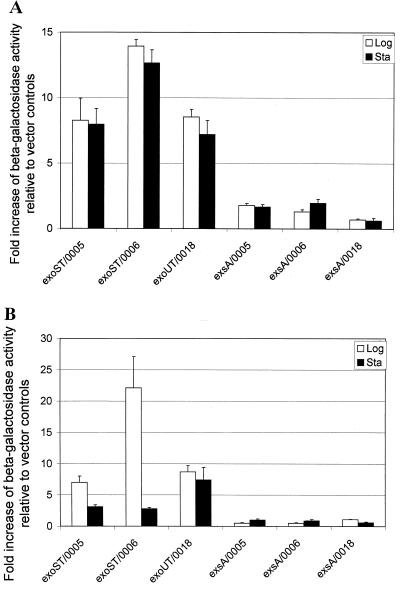

Expression of the exoS and exoT genes in exponential- and stationary-growth phases.

The anti-internalization functions of the ExoS and ExoT are observed only in exponential-phase cells of the invasive strain PAK, suggesting that the expression of exoS and exoT might be regulated in a growth phase-dependent manner. To examine this, we generated lacZ reporter gene fusions to exoS and exoT promoters derived from PAK as well as exoT promoter derived from PA103, i.e., pHW0005, pHW0006, and pHW0018, respectively. The three fusion constructs were transformed into PAKexoSexoT and PA103exoUexoT, as well as type III mutant PAKexsA. The strains were cultured in L broth containing appropriate antibiotics to exponential or stationary phase, and the β-galactosidase activities were measured. As shown in Fig. 3A, expression of the exoS and exoT in a PAKexoSexoT and PA103exoUexoT background was not significantly different in the two growth phases. As expected, no significant expression of exoS and exoT was detected in PAKexsA mutant in either of the two growth phases. These results indicated that the growth phase-dependent internalization rate of the invasive PAK strain is not caused by a difference in the expression of exoS and exoT in L broth before subjecting it to invasion assays.

FIG. 3.

Transcriptional activation of exoS and exoT. (A) Growth phase-dependent expressions. Bacterial strains were cultured in L broth containing appropriate antibiotics to the exponential and stationary phases. The cultured bacterial cells were subjected to a standard β-galactosidase assay. The displayed values are the fold increase of β-galactosidase activity relative to the expression of pDN19lacΩ vector control. (B) Cell contact-mediated expression. The exponential- and stationary-phase bacterial cells were used to infect HeLa cells and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 2 h. After three washes with PBS, bacteria associated with the HeLa cells were counted and subjected to the β-galactosidase assay. The displayed values are the fold increase of β-galactosidase activity relative to that of the pDN19lacΩ vector control. exsA, type III mutant strain PAKexsA; exoST, PAKexoSexoT double mutant; exoUT, PA103exoUexoT double mutant; 0005, pHW0005 encoding the exoS::lacZ fusion of PAK; 0006, pHW0006 encoding the exoT::lacZ fusion of PAK; 0018, pHW0018 encoding the exoT::lacZ fusion of PA103. Average values from three repeated tests are shown.

Next, we tested if there is a difference in the cell contact-mediated expression of the exoS and exoT. To avoid HeLa cell lifting, PAKexoSexoT and PA103exoUexoT containing either the exoS::lacZ or the exoT::lacZ fusion construct were used. Bacterial cells were grown in L broth to exponential or stationary phase and used to infect HeLa cells in DMEM tissue culture medium containing 5% FCS. After 2 h of incubation, the β-galactosidase activities of the HeLa cell associated bacteria were measured. As shown in Fig. 3B, the β-galactosidase activities of the exponential-phase PAKexoSexoT were sharply higher than those of the stationary-phase cells, especially exoT, whose induction in exponential-phase cells was more than sevenfold higher than that of stationary-phase cells. However, in the PA103exoUexoT background, cell contact-mediated expression of the exoT was equally high in both the exponential- and the stationary-growth phases. These results indicated that cell contact-mediated activation of exoS and exoT expression is dependent on the growth phases in invasive strain PAK but not in the cytolytic PA103, implying a difference in regulatory mechanisms of the expression of the exoenzymes between the two strains.

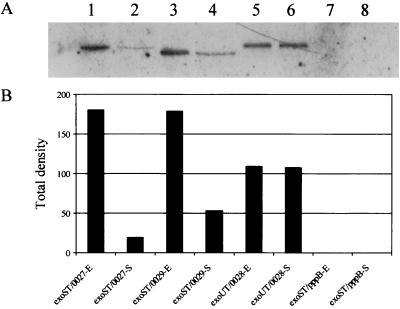

Translocation of ExoS and ExoT into HeLa cells during infection.

As type III effector molecules, the ExoS and ExoT must be translocated into the host cells to exert their functions. To trace the amount of ExoS and ExoT that were translocated into the HeLa cells, plasmid constructs were generated in which C termini of the ExoS and ExoT were tagged with the FLAG peptide. Plasmid constructs with ExoS-FLAG and ExoT-FLAG of PAK, pHW0029 and pHW0027, respectively, were introduced into PAKexoSexoT, whereas the ExoT-FLAG of PA103, pHW0028; was introduced into PA103exoUexoT. Resulting strains were cultured in L broth to exponential or stationary phase and infected HeLa cells at an MOI of 10 for PAK derivatives and of 100 for PA103 derivatives to obtain a similar number of bacterial cell binding to each HeLa cell (see Materials and Methods). After 2 h of incubation, the infected HeLa cells were then lysed with 0.25% Triton X-100, cell debris and bacterial cells were removed by centrifugation, and proteins in the supernatant were precipitated with TCA. The precipitated protein samples were standardized with the number of bacterial cells associated with the HeLa cells during the infection. ExoS and ExoT in the precipitate, representing those translocated, were detected by Western blot analysis using monoclonal antibody against the FLAG tag.

As shown in Fig. 4, the exponential-phase PAK cells translocated an ∼9.2-fold-higher amount of ExoT and an ∼3.4-fold-higher amount of ExoS into HeLa cells than the stationary-phase PAK cells. However, the cytolytic PA103 did not show a significant difference in the amounts of ExoT translocation between exponential- and stationary-growth-phase cells. As a control, no ExoS-FLAG or ExoT-FLAG translocation was detected when the HeLa cells were infected with PAKexsA harboring the exoS-FLAG or exoT-FLAG construct (data not shown). In addition, PAKexoSexoT harboring pppB-FLAG fusion, a non-type III secreted cytoplasmic protein, translocated no detectable amount of the PppB-FLAG (Fig. 4), although a high amount of this protein was detected from the bacterial lysate (data not shown). Together, these results indicated that the ExoS and ExoT proteins detected in our assays were the results of specific type III secretion into HeLa cells.

FIG. 4.

Growth phase-dependent translocation of ExoS and ExoT into HeLa cells. The exponential (E)- and stationary (S)-phase bacterial cells were used to infect HeLa S3 cells at an MOI of 10 and incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 2 h. After three washes with PBS, the infected HeLa cells were collected and lysed with 0.25% Triton X-100. The insoluble pellet of the lysate was suspended with PBS to count the number of associated bacteria. Proteins in the supernatant of HeLa cell lysate were precipitated with TCA. The numbers of bacterial cells associated with the HeLa cells were used to standardize the amount of proteins subjected to Western blot analysis. The intensities of the Western blot bands were scanned by densitometer, and the resulting values are shown in the bar figure. exoST, PAKexoSexoT double mutant; exoUT, PA103exoUexoT double mutant; 0027, pHW0027 encoding the exoT-FLAG fusion of PAK; 0028, pHW0028 encoding the exoT-FLAG fusion of PA103; 0029, pHW0029 encoding the exoS-FLAG fusion of PAK; pppB, encoding the pppB-FLAG fusion of PAK.

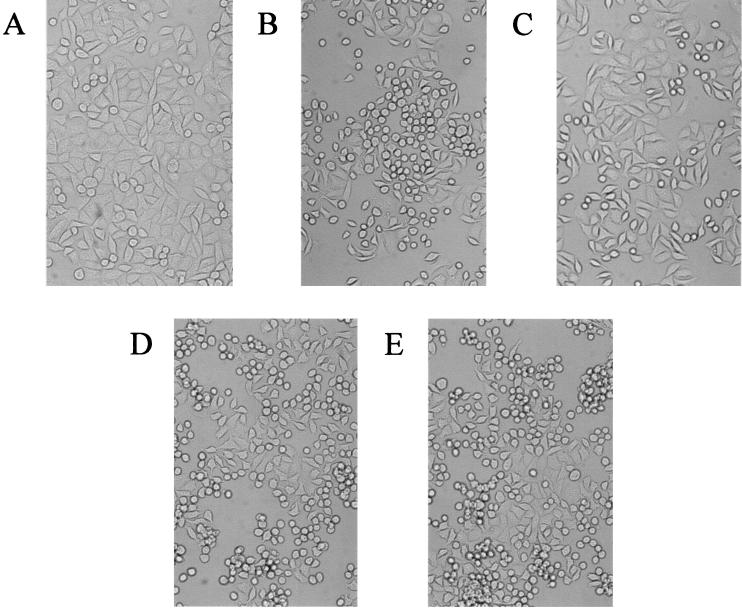

The injection of both ExoS and ExoT is known to disrupt host cell cytoskeletal structures causing HeLa cell morphological changes (cell rounding). Correlating with the growth phase-dependent secretion of ExoS and ExoT, the rates of HeLa cell rounding were also dependent on the growth phases of the infecting bacterium. As shown in Fig. 5, after 80 min of incubation, exponential- and stationary-phase PAK cells caused 60 and 20% HeLa cell rounding, respectively, whereas PAKexsA and PAKexoSexoT mutants did not cause significant cell rounding at either growth phase (data not shown). However, independent of growth phases, PA103exoU caused 60% cell rounding, whereas PA103exoUexoT did not cause any cell rounding (data not shown). These results clearly indicated that the exponential-phase PAK cells translocate more efficiently than the stationary-phase cells both the ExoS and the ExoT proteins into HeLa cells, and the higher amounts of translocated ExoS and ExoT proteins inhibit the uptake of PAK cells, resulting in a growth phase-dependent invasion phenotype.

FIG. 5.

Morphological changes of HeLa cells infected with P. aeruginosa. Exponential- and stationary-phase bacterial cells were used to infect HeLa S3 cells that were cultured on cover glasses. After incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2 for the indicated length of times, the HeLa cells on the cover glasses were observed under a light microscope. (A) No infection as a control. (B) HeLa cells infected with exponential-phase of PAK. (C) HeLa cells infected with stationary-phase PAK. (D) HeLa cells infected with exponential-phase PA103exoU mutant. (E) HeLa cells infected with stationary-phase PA103exoU mutant.

Intracellular survival of invasive and noninvasive P. aeruginosa strains.

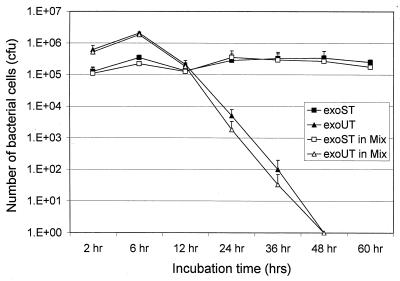

Since mammalian cells can effectively clear most intracellular bacteria, invasive bacterial pathogens are usually equipped with factors that enable them to evade the bactericidal effect of the host cells. We tested whether the invasive strain PAK is also equipped with such a factor. To compare the intracellular survival of invasive strain PAK and noninvasive strain PA103, corresponding mutant strains PAKexoSexoT and PA103exoUexoT were used to avoid cytotoxicity and cell lifting. HeLa cells were infected with each mutant for 2 h, followed by amikacin treatment to kill extracellular bacteria. To achieve the same number of bacteria bound to the HeLa cells, a 10-fold higher MOI was used for PA103exoUexoT than for PAKexoSexoT. HeLa cells were lysed at various time points and plated to count the intracellular bacteria. As shown in Fig. 6, PAKexoSexoT maintained high viability inside HeLa cells by 60 h, the longest time point followed, whereas the viability of PA103exoUexoT decreased dramatically after 4 h of amikacin treatment and cleared completely by 48 h. Similar results have been obtained when the HeLa cells were infected with a 1:10 mixture of PAKexoSexoT and PA103exoUexoT (Fig. 6). The mixed infection exposed both mutants to the same intracellular environment, allowing us to accurately compare the relative survival abilities of the two mutant strains. Furthermore, the MIC of amikacin for both strains was identical (20 μg/ml), indicating that the observed decrease in intracellular survival of PA103exoUexoT was not caused by a higher sensitivity to the amikacin. These results demonstrate that the invasive PAK strain has evolved an intracellular survival mechanism, whereas the noninvasive PA103 strain lost or has not acquired such ability.

FIG. 6.

Intracellular survival of P. aeruginosa strains in HeLa cells. Stationary-phase bacteria were used to infect HeLa S3 cells, and the infected HeLa cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 2 h. After three washes with PBS, the HeLa cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 2, 6, 12, 24, 36, 48, and 60 h in the presence of 400 μg of amikacin per ml to kill extracellular bacteria. The number of intracellular bacterial cells was calculated by colony count. Symbols: ■, PAKexoSexoT double mutant; ▴, PA103exoUexoT double mutant; □, PAKexoSexoT double mutant in the mixed infections; ▵, PA103exoUexoT double mutant in the mixed infections. Average values of three repeated tests are shown.

DISCUSSION

The growth phase-dependent variation of invasion could be the result of an increased expression of invasin during the stationary phase or an increased expression of anti-internalization factor during the exponential phase. The fact that a type III mutant strain PAKexsA is highly invasive in both exponential and stationary phases suggested the latter is the case. Although both ExoS and ExoT were shown to act as anti-internalization factors in a cytolytic strain background (7), it was not clear why exoS and exoT harboring invasive strains are highly invasive (12). In this study, we first demonstrated that there is no significant difference in the anti-internalization activities of the ExoS and ExoT derived from the two types of strains. Then, we showed that there is no interference of the anti-internalization functions between ExoS and ExoT, as P. aeruginosa has been known to produce a heterologous aggregate of ExoS and ExoT (33). Finally, the growth phase-dependent invasion phenotype was correlated to the differential expression of the exoS and exoT during the exponential phase versus the stationary phase in response to HeLa cell contact. This cause-and-effect relationship was confirmed by demonstrating that the ExoS and ExoT do function as anti-internalization factors in both invasive and noninvasive strains, although the anti-internalization phenotype is only observable in exponential-phase cells of the invasive strain. Another possibility existed in which the stationary-phase cells of invasive PAK might synthesize a specific inhibitor that interrupts the anti-internalization functions of the ExoS and ExoT. The inhibitor molecule could be secreted directly into the host cells or localized on the surface of bacterial cells which interrupts host cell signal transduction through direct interaction. This possibility was addressed by a mixed infection of PAKexoSexoT as the source of the possible inhibitor and PA103exoU as the source of anti-internalization factor ExoT. The anti-internalization function of ExoT from PA103exoU was not affected by the presence of PAKexoSexoT, resulting in low invasion of both strains (data not shown). This result indicated that PAK has no inhibitor that blocks anti-internalization functions of the ExoS and ExoT.

ExoS and ExoT are highly homologous, and both have two domain structures, with N-terminal domains having GAP (GTPase-activating protein) activities that cause disruptions in cytoskeletal structures and C-terminal domains with ADP-ribosylation activities (16, 18, 20, 27). The ADP-ribosylating activity of ExoT is only 0.2% that of ExoS (36), although both molecules showed similar levels of anti-invasion activity; thus, it is unlikely that this activity is directly linked to the anti-internalization function. Also, the experimental result with the ExoS(E381A) mutant which is defective in ADP-ribosylating activity further supported the notion that the N-terminal domains play the anti-internalization roles (7). This is consistent with the observation that ExoS, ExoT, and ExoS(E381A) caused morphological changes without causing obvious membrane damages, indicating that actin microfilaments are important for epithelial cells to take up P. aeruginosa (13, 33). Thus, cytoskeletal disrupting functions of the ExoS and ExoT are likely responsible for the inhibition of bacterial internalization.

Expressions of type III secretion components, including ExoS and ExoT, are known to be stimulated by the depletion of divalent cations with the treatment of EGTA or nitrilotriacetic acid, as well as contact with mammalian cells (31). However, differences have been observed between these two inducing conditions. Addition of 5 mM EGTA induced significant levels of exoS-lacZ and exoT-lacZ expression only after 4 h, whereas a 2-h treatment had minimal effect. However, a 2-h incubation with HeLa cells resulted in significant levels of both ExoS and ExoT expression, in comparison to incubation with tissue culture medium without HeLa cells, indicating that there is a difference in the ExsA-regulated genes responding to the low-calcium conditions versus contact with eukaryotic cells. Since the growth phase-dependent invasion was detected as early as 2 h postinfection, all of the assays were conducted after a 2-h treatment (13). Our results of growth phase-dependent invasion indicated that the exponential-phase PAK is much more sensitive to cell contact signals than the stationary-phase cells, whereas the PA103 responds equally well to the cell contact signal in the two growth phases.

Correlating to the cell contact-mediated activation of gene expression, translocation of the ExoS and ExoT into the host cell followed the same pattern. Exponential-phase PAK translocated a 9.2-fold-higher amount of ExoT and a 3.4-fold-higher amount of ExoS into the HeLa cells than did stationary-phase PAK, whereas the amount of ExoT translocated by the two growth-phase PA103 cells were not significantly different. Therefore, the increased secretion of exoenzymes by the exponential-phase cells could efficiently block the internalization of bacteria into HeLa cells and cause faster cell rounding than by the stationary phase of PAK. These results suggested that there is a difference in the signal sensing and regulation of type III component between the two strains. A similar observation was also made by Dacheux et al. (8), who found that an invasive strain of P. aeruginosa CHA caused the most rapid cell death when it was in the late-exponential-growth phase, whereas the bacterial cytotoxicity dramatically decreased as soon as the bacterial growth phase entered the stationary phase.

From the evolutionary point of view, the invasive PAK might be adapted to the environments of mammalian cells and better able to survive intracellularly than the cytotoxic PA103. To compare the intracellular survival of invasive versus cytolytic strains, we have used PAKexoSexoT and PA103exoUexoT, both of which are highly invasive and do not possess major host cell disrupting exoenzymes. Exposure of mammalian cells to ExoS and ExoU leads to cell death through apoptosis and necrosis, respectively, whereas ExoT alters the actin cytoskeleton typically by activating Rho-GTPase proteins (20). Our data clearly indicated that the invasive strain PAK has a mechanism to avoid intracellular killing and maintains its viability, whereas the cytolytic strain PA103 has no such defense and is cleared quickly. A similar observation has also been made for a closely related strain of Burkholderia cepacia, for which it was shown that clinical isolates are able to survive intracellularly in both cultured macrophage and epithelial cells, whereas environmental isolates are defective in this ability (24). The high internalization rate and stable persistence inside host cells could contribute to bacterial ability to evade host immune defense and the efficient dissemination into deeper organs tissues.

Based on the growth phase-dependent invasion of PAK, invasive strains may have two kinds of lifestyles depending on the environmental condition. During the stationary phase, typically under harsh growth conditions such as nutrient depletion and increasing host immune attacks, PAK becomes invasive by turning down ExoS and ExoT secretion and escapes inside host cells, where it can persist for a long period of time, whereas during exponential-growth phase under a high nutrient growth environment there is no need to invade host cells; thus, PAK acts more like a cytolytic strain by increasing the expression and secretion of ExoS and ExoT in response to the cell contact, inhibiting internalization into the host cells. In contrast to the invasive PAK, regardless of the growth phases, the cytolytic strain PA103 blocks its uptake into the cells and kills through the action of ExoU. These hypotheses would predict that cytolytic strains are more likely associated with acute and localized tissue necrosis, whereas invasive strains are more likely associated with chronic and systemic infections.

The observation that a noninvasive strain PA103exoU can be converted into an invasive strain by mutating the anti-internalization factor exoT indicated that the noninvasive strain naturally encodes an invasin. Since the type III gene clusters are acquired by bacterial pathogens through horizontal gene transfers, it is therefore likely that strain PA103 is derived from an invasive ancestor by acquiring the anti-invasion factor. Furthermore, despite the fact that the noninvasive strain PA103 has lost or did not acquire genes for intracellular survival, it retained the invasin molecule, suggesting that the invasin is likely to have additional function that is essential or that renders the bacterium a survival advantage. In support of this view, the invasin gene seems to be constitutively expressed in both types of strains since PAKexoSexoT and PA103exoUexoT are highly invasive regardless of growth phases. A recent study by Fleiszig's group has shown that mutation in a key component required for flagellum assembly, flhA, drastically reduces bacterial invasion (C. van Delden, S. K. Aurora, R. Ramphal, and M. J. Fleiszig, Abstr. 100th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 2000, abstr. D-145, 2000). Since the FlhA is an inner membrane protein and is commonly present among flagellated bacterium, the finding implies that the translocation of the “invasin” to the bacterial cell surface or secretion into the host cell requires this component. The real invasin molecule has yet to be identified.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank members of S. Jin's laboratory for helpful discussion and suggestions.

This work was supported by NIH grant R29AI39524.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anwar H, Strap J L, Costerton J W. Establishment of aging biofilms: possible mechanism of bacterial resistance to antimicrobial therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:1347–1351. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.7.1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asboe D, Gant V, Aucken H M, Moore D A, Umasankar S, Bingham J S, Kaufmann M E, Pitt T L. Persistence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains in respiratory infection in AIDS patients. AIDS. 1998;12:1771–1775. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199814000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bodey G P, Bolivar R, Fainstein V, Jadeja L. Infections caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Rev Infect Dis. 1983;5:279–313. doi: 10.1093/clinids/5.2.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bourne H R, Sanders D A, McCormick F. The GTPase superfamily: a conserved switch for diverse cell functions. Nature. 1990;348:125–132. doi: 10.1038/348125a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coburn J, Gill D M. ADP-ribosylation of p21ras and related proteins by Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzyme S. Infect Immun. 1991;59:4259–4262. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.11.4259-4262.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costerton J W, Stewart P S, Greenberg E P. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science. 1999;284:1318–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cowell B A, Chen D Y, Frank D W, Vallis A J, Fleiszig S M. ExoT of cytotoxic Pseudomonas aeruginosa prevents uptake by corneal epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2000;68:403–406. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.403-406.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dacheux D, Toussaint B, Richard M, Brochier G, Croize J, Attree I. Pseudomonas aeruginosa cystic fibrosis isolates induce rapid, type III secretion-dependent, but ExoU-independent, oncosis of macrophages and polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2916–2924. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.5.2916-2924.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doring G, Maier M, Muller E, Bibi Z, Tummler B, Kharazmi A. Virulence factors of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antibiot Chemother. 1987;39:136–148. doi: 10.1159/000414341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans D J, Frank D W, Finck-Barbancon V, Wu C, Fleiszig S M. Pseudomonas aeruginosa invasion and cytotoxicity are independent events, both of which involve protein tyrosine kinase activity. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1453–1459. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1453-1459.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finck-Barbancon V, Goranson J, Zhu L, Sawa T, Wiener-Kronish J P, Fleiszig S M, Wu C, Mende-Mueller L, Frank D W. ExoU expression by Pseudomonas aeruginosa correlates with acute cytotoxicity and epithelial injury. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:547–557. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4891851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fleiszig S M, Wiener-Kronish J P, Miyazaki H, Vallas V, Mostov K E, Kanada D, Sawa T, Yen T S, Frank D W. Pseudomonas aeruginosa-mediated cytotoxicity and invasion correlate with distinct genotypes at the loci encoding exoenzyme S. Infect Immun. 1997;65:579–586. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.579-586.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fleiszig S M, Zaidi T S, Pier G B. Pseudomonas aeruginosa invasion of and multiplication within corneal epithelial cells in vitro. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4072–4077. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.10.4072-4077.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frank D W, Nair G, Schweizer H P. Construction and characterization of chromosomal insertional mutations of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzyme S trans-regulatory locus. Infect Immun. 1994;62:554–563. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.2.554-563.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frithz-Lindsten E, Du Y, Rosqvist R, Forsberg A. Intracellular targeting of exoenzyme S of Pseudomonas aeruginosa via type III-dependent translocation induces phagocytosis resistance, cytotoxicity and disruption of actin microfilaments. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:1125–1139. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5411905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goehring U M, Schmidt G, Pederson K J, Aktories K, Barbieri J T. The N-terminal domain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzyme S is a GTPase-activating protein for Rho GTPases. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36369–36372. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hauser A R, Fleiszig S, Kang P J, Mostov K, Engel J N. Defects in type III secretion correlate with internalization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1413–1420. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.4.1413-1420.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iglewski B H, Sadoff J, Bjorn M J, Maxwell E S. Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzyme S: an adenosine diphosphate ribosyltransferase distinct from toxin A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:3211–3215. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.7.3211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaufman M R, Jia J, Zeng L, Ha U, Chow M, Jin S. Pseudomonas aeruginosa mediated apoptosis requires ADP-ribosylating activity of ExoS. Microbiology. 2000;146:2531–2541. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-10-2531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krall R, Schmidt G, Aktories K, Barbieri J T. Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoT is a rho GTPase-activating protein. Immun Infect. 2000;68:6066–6068. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.10.6066-6068.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kulich S M, Frank D W, Barbieri J T. Expression of recombinant exoenzyme S of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.1.1-8.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu P V. The roles of various fractions of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in its pathogenesis. III. Identity of the lethal toxins produced in vitro and in vivo. J Infect Dis. 1966;116:481–489. doi: 10.1093/infdis/116.4.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lory S, Tai P C. Biochemical and genetic aspects of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1985;118:53–69. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-70586-1_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin D W, Mohr C D. Invasion and intracellular survival of Burkholderia cepacia. Infect Immun. 2000;68:24–29. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.24-29.2000. . (Erratum, 68:3792.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller J H. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicas T I, Iglewski B H. The contribution of exoproducts to virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Can J Microbiol. 1985;31:387–392. doi: 10.1139/m85-074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pederson K J, Vallis A J, Aktories K, Frank D W, Barbieri J T. The amino-terminal domain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoS disrupts actin filaments via small-molecular-weight GTP-binding proteins. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:393–401. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roilides E, Butler K M, Husson R N, Mueller B U, Lewis L L, Pizzo P A. Pseudomonas infections in children with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992;11:547–553. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199207000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory mannual. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schweizer H P. Escherichia-Pseudomonas shuttle vectors derived from pUC18/19. Gene. 1991;97:109–112. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thompson M R, Bjorn M J, Sokol P A, Lile J D, Iglewski B H. Exoenzyme S: an ADP-ribosyl transferase produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. In: Smulson M, Sugimura T, editors. Novel ADP-ribosylations of regulatory enzymes and proteins. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier North-Holland, Inc.; 1980. pp. 425–433. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Totten P A, Lory S. Characterization of the type a flagellin gene from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAK. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:7188–7199. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.12.7188-7199.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vallis A J, Finck-Barbancon V, Yahr T L, Frank D W. Biological effects of Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III-secreted proteins on CHO cells. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2040–2044. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.4.2040-2044.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vallis A J, Yahr T L, Barbieri J T, Frank D W. Regulation of ExoS production and secretion by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in response to tissue culture conditions. Infect Immun. 1999;67:914–920. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.2.914-920.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Delden C, Iglewski B H. Cell-to-cell signaling and Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 1998;4:551–560. doi: 10.3201/eid0404.980405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yahr T L, Barbieri J T, Frank D W. Genetic relationship between the 53- and 49-kilodalton forms of exoenzyme S from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:1412–1419. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.5.1412-1419.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yahr T L, Goranson J, Frank D W. Exoenzyme S of Pseudomonas aeruginosa is secreted by a type III pathway. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:991–1003. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.01554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yahr T L, Hovey A K, Kulich S M, Frank D W. Transcriptional analysis of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzyme S structural gene. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1169–1178. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.5.1169-1178.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yahr T L, Mende-Mueller L M, Friese M B, Frank D W. Identification of type III secreted products of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzyme S regulon. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7165–7168. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.22.7165-7168.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]