Abstract

Brucella spp. are gram-negative intracellular pathogens that survive and multiply within phagocytic cells of their hosts. Smooth organisms present O polysaccharides (OPS) on their surface. These OPS help the bacteria avoid the bactericidal action of serum. The wboA gene, coding for the enzyme glycosyltransferase, is essential for the synthesis of O chain in Brucella. In this study, the sensitivity to serum of smooth, virulent Brucella melitensis 16M and B. abortus 2308, rough wboA mutants VTRM1, RA1, and WRR51 derived from these two Brucella species, and the B. abortus vaccine strain RB51 was assayed using normal nonimmune human serum (NHS). The deposition of complement components and mannose-binding lectin (MBL) on the bacterial surface was detected by flow cytometry. Rough B. abortus mutants were more sensitive to the bactericidal action of NHS than were rough B. melitensis mutants. Complement components were deposited on smooth strains at a slower rate compared to rough strains. Deposition of iC3b and C5b-9 and bacterial killing occurred when bacteria were treated with C1q-depleted, but not with C2-depleted serum or NHS in the presence of Mg-EGTA. These results indicate that (i) OPS-deficient strains derived from B. melitensis 16M are more resistant to the bactericidal action of NHS than OPS-deficient strains derived from B. abortus 2308, (ii) both the classical and the MBL-mediated pathways are involved in complement deposition and complement-mediated killing of Brucella, and (iii) the alternative pathway is not activated by smooth or rough brucellae.

The complement system represents an important defense mechanism against microorganisms. There are three pathways by which the complement system can be activated: (i) the classical pathway, which is initiated by binding of C1q to the Fc regions of antigen-antibody complexes or directly to pathogenic bacteria (15, 37); (ii) the alternative pathway, which is an antibody-independent route initiated by certain structures on the surface of microorganisms; and (iii) the lectin pathway, which is initiated by the binding of mannose-binding lectin (MBL) to carbohydrates on microbial surfaces (33, 37, 43, 46, 47). MBL and another collectin, pulmonary surfactant protein A (SP-A), can trigger cellular responses in a manner similar to that of C1q (15, 39). After activation, complement can effectively eliminate microorganisms by deposition of proteins onto the microbial surface, which will (i) serve as opsonins (C1q, C3b or iC3b, and C4b), providing immune recognition of those organisms by phagocytic cells, and (ii) lead to the formation and assembly of the membrane attack complex (MAC or C5b-9), causing the direct lysis of those microorganisms (15, 16, 26, 44). However, microbial pathogens have developed effective strategies to avoid recognition or eradication by complement (56). Avoidance structures of pathogenic microorganisms include lipopolysaccharides (LPS), outer membrane proteins (OMP), capsules, porins, and several proteins sharing molecular mimicry of host complement proteins (1, 2, 11, 25, 27, 28, 31, 32, 34, 42, 48, 56).

Brucella spp. are gram-negative intracellular pathogens, which can survive and multiply within phagocytic cells of their hosts and are resistant to the bactericidal action of serum. Treatment of virulent Brucella with normal nonimmune human serum (NHS) does not result in complement-mediated killing but enhances their ingestion by macrophages (41). The genus Brucella consists of six species, each one with a preference for a host and with differences in pathogenicity: Brucella abortus (cattle), B. melitensis (goats), B. canis (dogs), B. ovis (sheep), B. suis (swine), and B. neotomae (desert rat) (41). However, at the DNA level this genus is a highly homogeneous group that has been proposed to be only one genomic species (52). B. abortus and B. melitensis constitute the main pathogenic species for humans worldwide. These two species may occur as either smooth or rough variants depending on the expression of O polysaccharides (OPS) as a component of the bacterial outer membrane LPS. In rough strains, the expression of OPS is limited or absent and the attenuation of virulence is generally observed (3, 9, 19, 29). Curiously, B. ovis and B. canis are two naturally rough Brucella species that are fully virulent in their primary host despite their lack of surface O antigen (4, 5, 19). The O antigen of B. abortus and B. melitensis is a homopolymer of perosamine (4,6-dideoxy-4-formamido-d-mannopyranosyl), which exists in two different configurations. The A (abortus) antigen is a linear homopolymer of α1,2-linked-perosamine. The M (melitensis) antigen is a linear homopolymer of the same sugar in which four α1,2-linked-perosamine residues are α1,3-linked to the last monosaccharide of a pentasaccharide repeating unit (22, 23). Although A and M antigens may be present alone or together on either B. abortus or B. melitensis, strain 2308 expresses almost exclusively A antigen and strain 16M expresses M antigen (30). B. melitensis, the principal cause of human brucellosis (55, 57), differs from B. abortus in virulence and cell envelope (17, 58). Previous studies using bovine serum (17) and NHS (58) have suggested that B. melitensis is more resistant than B. abortus to the bactericidal action of complement, although the mechanisms of this enhanced resistance are unknown. Smooth strains of B. abortus are more resistant than rough strains to serum bactericidal activity (9, 12, 13). Although this difference has plausibly been attributed to the lack of surface OPS in rough strains, the strains used in these studies were not genetically characterized, and the contribution of other components beside OPS to the resistance of smooth strains could not be rigorously excluded. The aim of this study was to investigate the bactericidal activity and complement activation pathways of NHS against smooth, virulent B. melitensis 16M and B. abortus 2308 and rough mutant strains derived from these two Brucella species by interrupting the wboA gene, which is required for O-chain synthesis (29). Bacteria were treated with NHS at different concentrations and incubation times, and bacterial survival was then determined. Additionally, deposition of complement components (C1q, C2, C4, iC3b, and C5b-9) and MBL on the bacterial surface was detected using a novel flow cytometric technique. Finally, to elucidate the complement pathways involved in killing or opsonization of Brucella, bacteria were treated with sera depleted of C1q or C2 or preincubated with Mg-EGTA prior to determination of bacterial survival and complement deposition. These studies demonstrated that (i) OPS-deficient strains derived from B. melitensis 16M are more resistant to the bactericidal action of NHS than OPS-deficient strains derived from B. abortus 2308, (ii) both the classical and the MBL-mediated pathways are involved in complement deposition and complement-mediated killing of Brucella, and (iii) the alternative pathway is not activated by smooth or rough brucellae. Smooth brucellae may limit complement deposition on their surface to protect them from extracellular killing but allow sufficient deposition to opsonize them for uptake by macrophages, their preferred target for intracellular replication.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The Brucella strains used in these experiments are listed in Table 1. Rough strains RB51 and RA1 are wboA mutants derived from B. abortus 2308 (29). The wboA gene, previously called rfbU, codes for the enzyme glycosyltransferase, which is essential for the synthesis of O chain in Brucella. Strain RA1 was derived from B. abortus 2308 by transposon (Tn5) disruption of the wboA gene (55). Strain RB51 is devoid of the O chain and arose spontaneously after multiple passages (40); an IS711 element interrupts the wboA gene in this strain (50). RB51 contains at least one additional mutation, but the exact nature of the mutation(s) remains unknown (41, 50, 51). Strain VTRM1 was derived from B. melitensis 16M by transposon (Tn5) disruption of the wboA gene (55). Strain WRR51 was derived from B. melitensis 16M by replacement of the internal region of the wboA gene with an antibiotic resistance cassette (M. P. Nikolich, unpublished results). Strain WRR51/pRFBUK11 was derived by electroporating pRFBUK11 into strain WRR51. This procedure complemented the wboA gene and restored the smooth phenotype (Nikolich, unpublished). Bacteria were grown at 37°C with shaking in Brucella broth (Difco).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Strain | Species | Description | Sourcea |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2308 | B. abortus | Wild-type; smooth strain | VMRCVM |

| RB51 | B. abortus | Rough mutant of 2308, Rif; nature of mutation is unknown | VMRCVM |

| RA1 | B. abortus | Rough mutant of 2308; Tn5 disruption of glycosyltransferase gene, named wboA | VMRCVM |

| 16M | B. melitensis | Wild-type, smooth strain | VMRCVM |

| VTRM1 | B. melitensis | Rough mutant of 16M; Tn5 disruption of glycosyltransferase gene, named wboA | VMRCVM |

| WRR51 | B. melitensis | Rough mutant of 16M by replacement of the wbo gene with an antibiotic resistance gene | WRAIR |

| WRR51/pRFBUK11 | B. melitensis | WRR51 complemented with wboA; smooth strain | WRAIR |

VMRCVM, Virginia-Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine; WRAIR, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research.

Sera.

NHS was obtained from members of the laboratory staff and stored at −70°C until required. Sera were negative for Brucella antibody by agglutination tests. Sera depleted of either C1q or C2 were purchased from Quidel Corp. (San Diego, Calif.). For inactivation of the classical and MBL-mediated pathways of complement activation, EGTA (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) and MgCl2 (10 mM) were added as described previously (38). To inactivate complement completely, sera were heated at 56°C for 30 min as described elsewhere (38).

Bactericidal assay.

Brucella strains were grown to mid-logarithmic phase, collected by centrifugation, washed in 0.9% NaCl, recentrifuged, and suspended in RPMI 1640 medium (RPMI) at approximately 106 CFU/ml. Next, 100 μl of these suspensions was transferred into each well in a 96-well plate containing 100 μl of either fresh (i.e., frozen at −70°C) or heat-inactivated NHS. The plates were incubated at 37°C for different times in a CO2 incubator. At each time point, 10-μl samples were transferred to another 96-well plate in which each well contained 90 μl of RPMI to make serial dilutions. Two or three 10-μl samples were spot plated from each well onto Brucella agar, and the plates were incubated at 37°C in a CO2 incubator for 3 days. CFU were enumerated; duplicate or triplicate spots were averaged.

Antibodies.

Mouse monoclonal antibodies (MAb) to human antigens C1q, iC3b, C4, SC5b-9, factor B, and factor H, and goat polyclonal antiserum to human C2 were purchased from Quidel Corp. Mouse MAb to human MBL was purchased from Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark. Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-murine immunoglobulin G (IgG) and FITC-conjugated rabbit anti-goat antibody (heavy and light chain specific) were purchased from Sigma.

Flow cytometry.

Brucella strains were harvested from 24-h broth cultures and washed once with 0.9% NaCl. Bacterial suspensions were adjusted turbidometrically to a concentration of 107 CFU/ml in RPMI and incubated in 2, 3, or 10% serum for different periods of time at 37°C in a CO2 incubator. Then, 100 μl of these suspensions was transferred to a 96-well filter plate set on a filter unit. The samples were next washed three times with 300 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (Gibco) containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (PBS-BSA) and resuspended in 100 μl of PBS-BSA. Complement antibodies were added at a concentration of 20 μg/ml in PBS-BSA; nonspecific staining and unstained controls received PBS-BSA only. The plate was incubated at 4°C for 30 min (18). After washing and resuspending the samples as before, secondary, FITC-conjugated anti-murine IgG or anti-goat IgG antibody or PBS-BSA (for unstained controls) was added, and the plate was again incubated at 4°C for 30 min. Finally, samples were washed as before and fixed in 300 μl of 4% formaldehyde in PBS. Controls were cells either unstained or stained only with the secondary antibody. An aliquot of each sample was plated on Brucella agar plates and incubated for 3 days at 37°C in a CO2 incubator for sterility check. Samples were then acquired on Becton Dickinson FACSort flow cytometer and analyzed using CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, Calif.).

Elution of complement from bacterial surface.

Brucella strains were incubated with serum as outlined above, but bacteria were treated for 30 min at 37°C with 1 M NaCl in RPMI with 0.15 mM CaCl2 and 1.0 mM MgCl2 (14) before the samples were transferred to a 96-well filter plate set for staining for flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was done by Student's t test using INSTAT statistical analysis package (Graph Pad Software, Inc., San Diego, Calif.). The significance was P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Bactericidal effect of NHS on Brucella strains.

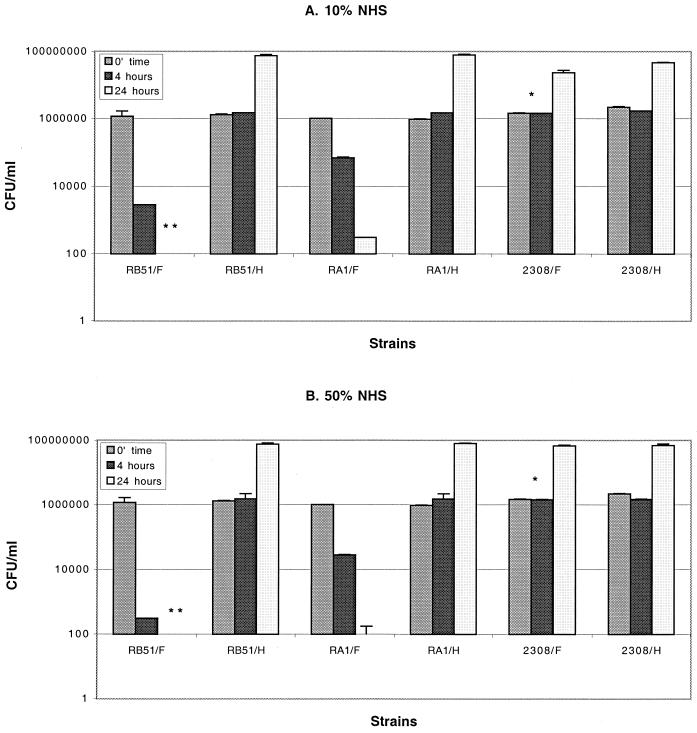

NHS was tested for its ability to kill the rough and smooth B. abortus and B. melitensis strains listed in Table 1 and described into Materials and Methods. As shown in Fig. 1, only rough B. abortus strains RB51 and RA1 were sensitive to the bactericidal action of serum. However, differences between these two rough B. abortus strains were detected. We found that 10% fresh NHS killed more than 2 log10 of RB51 in 4 h but only reduced RA1 by 1 log10 (Fig. 1A). Similar incubation with 50% NHS for 4 h led to 3.7 log10 reduction in RB51 but only 1.7 log10 reduction in RA1 (Fig. 1B). These differences were maintained even when the incubation period was extended to 24 h (Fig. 1). Strains RB51 and RA1 both multiplied nearly 10-fold when cultured with heated serum for 24 h, but 10 or 50% fresh serum reduced RB51 by more than 4 log10 from the starting inoculum and reduced RA1 by more than 3 log10. In contrast to this marked susceptibility of rough B. abortus to the bactericidal activity of NHS, rough B. melitensis strains VTRM1 and WRR51 were not killed by 10% or even 50% fresh serum. CFU counts were similar at all time points regardless of whether rough strains were incubated with fresh or heat-inactivated serum. Moreover, they multiplied as well as the smooth, wild-type strains 2308 (Fig. 1) or 16M or the smooth, complemented strain WRR51/pRFBUK11. These data imply that there are additional factors, beside the disruption of gene wboA, that mediate the varied sensitivity of these two Brucella species to the bactericidal action of serum.

FIG. 1.

Bactericidal effect of 10% (A) and 50% (B) NHS on rough and smooth B. abortus and B. melitensis strains. Bacteria were grown overnight at 37°C and incubated in fresh NHS (F) or heated serum (H) as described in Materials and Methods. The data represent the number of CFU/milliliter recovered at the initial time and after 4 and 24 h of incubation. The characteristics of the strains are listed in Table 1. ∗, Not significant P values compared to their respective CFU recovered after incubation with heat serum. Error bars show the means ± the standard deviations (SD). ∗∗, CFU/milliliter lower than 100 were not detected by the plating technique described in Materials and Methods.

Deposition of complement components on the surface of smooth and rough Brucella strains.

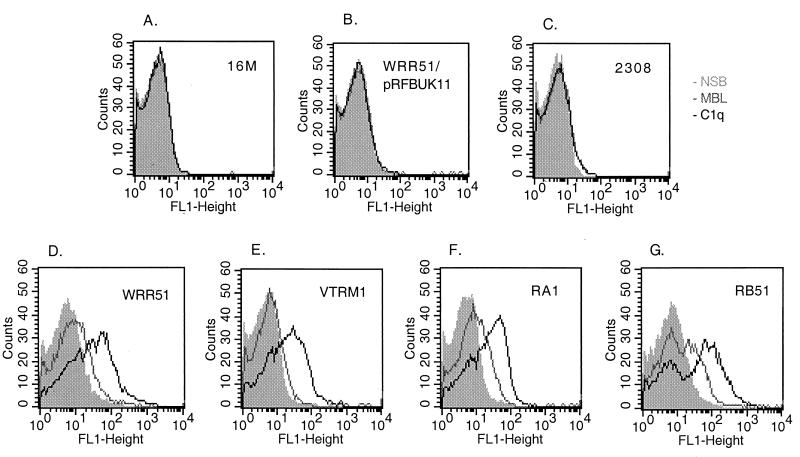

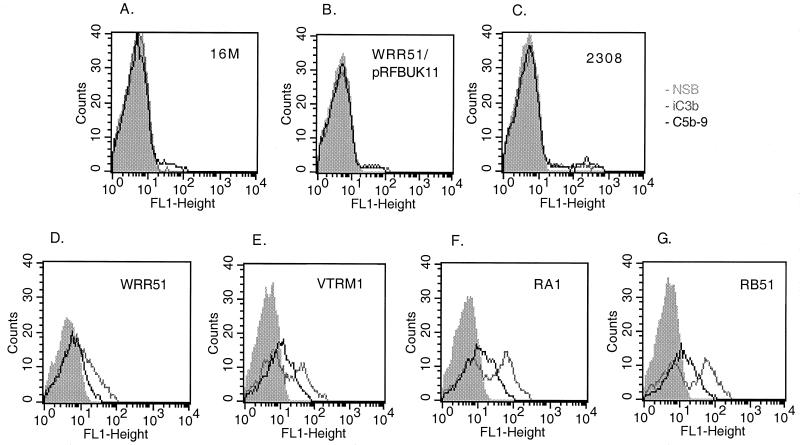

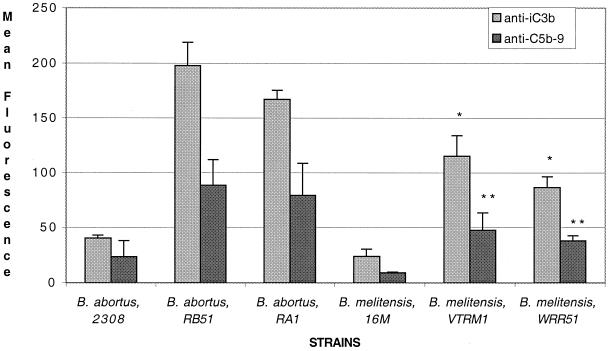

In preliminary experiments, we found that an NHS concentration of 2 to 3% and a treatment period of 1 to 2 h were optimal for flow cytometric detection of all complement proteins except C1q and MBL; these required a shorter treatment period and sometimes a higher NHS concentration in order to detect their binding to the bacterial surface (data not shown). In the experiment shown in Fig. 2, bacteria were exposed to 3% NHS and immediately fixed with formaldehyde. Rough Brucella strains (RB51, RA1, VTRM1, and WRR51) bound more MBL and C1q on their surface than smooth organisms (2308, 16M, and WRR51/pRFBUK11). Similarly rough strains bound more iC3b and C5b-9 than smooth strains (Fig. 3). These experiments also suggested that B. melitensis strains bound less complement than B. abortus strains. This suggestion was confirmed by experiments in which bacteria were treated with 2% serum and the binding of iC3b and C5b-9 was determined (Fig. 4). At that serum concentration, VTRM1 and WRR51 bound less iC3b (P < 0.008) and C5b-9 (P < 0.01) than either RB51 or RA1. Strain 16M bound slightly less of these components than strain 2308.

FIG. 2.

Comparative complement deposition on smooth (A to C) and rough (D to G) B. abortus (C, F, and G) and B. melitensis (A, B, D, and E) strains. Bacteria were fixed with formaldehyde immediately after the addition of 3% fresh NHS (F) or heated serum (H). The binding of MBL (gray line) and C1q (black line) to bacteria was detected by incubation with the corresponding MAb and secondary FITC-labeled antibodies as described in Materials and Methods. The respective nonspecific binding (NSB) is shown in the shaded area. Cells were analyzed on a FACSort flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). The panels show the results for 16M (A), WRR51/pRFBUK11 (B), 2308 (C), WRR51 (D), VTRM1 (E), RA1 (F), and RB51 (G). The characteristics of the strains are listed in Table 1. These data are from a representative experiment that was repeated with similar results.

FIG. 3.

Comparative complement deposition on smooth (A to C) and rough (D to G) B. abortus (C, F, and G) and B. melitensis (A, B, D, and E) strains. Bacteria were incubated in 3% fresh NHS or heated serum. Binding of iC3b (gray line) and C5b-9 (black line) to bacteria was detected by incubation with the corresponding MAb and secondary FITC-labeled antibodies as described in Materials and Methods. The respective nonspecific binding (NSB) is shown in the shaded area. Cells were analyzed on a FACSort flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). The panels show results for 16M (A), WRR51/pRFBUK11 (B), 2308 (C), WRR51 (D), VTRM1 (E), RA1 (F), and RB51 (G). The characteristics of the strains are listed in Table 1. These data are from a representative experiment that was repeated with similar results.

FIG. 4.

Comparative complement deposition between smooth and rough B. abortus and B. melitensis strains using 2% NHS. Bacteria were incubated and treated as described in the legend to Fig. 2. Here, deposition of iC3b and C5b-9 on each strain was compared using 2% fresh NHS. The rough B. abortus strains, RB51 and RA1, deposited more iC3b (∗, P<0.008) and C5b-9 (∗∗, P < 0.01) than the rough B. melitensis strains, VTRM1 and WRR51. Error bars show the means ± the SD of two different experiments. The characteristics of the strains are listed in Table 1.

These data suggested that differences in susceptibility to bactericidal activity in serum between rough and smooth strains and between B. melitensis and B. abortus might be due to differences in the quantity of complement components bound to the cell surface, particularly to the quantity of bound C5b-9, the MAC. It was also possible, however, that the MAC bound less tightly in resistant strains than in susceptible strains, as previously demonstrated in other microorganisms (14, 27). To address this latter possibility, we examined the susceptibility to elution by 1 M NaCl. Bacteria were treated with 10% NHS for 30 min and then incubated with 1 M NaCl for an additional 30 min. Cells were stained for complement components and analyzed by flow cytometry. A total of 85% of bound C5b-9 was eluted from the surface of 16M and 72% was eluted from 2308 by treatment with 1 M NaCl. In contrast, this treatment with 1 M NaCl eluted only 10 to 20% of C5b-9 from the surface of rough strains. These studies indicated that the C5b-9 complex was not attached by strong hydrophobic interactions to the cell surface of smooth Brucella.

Complement pathways involved.

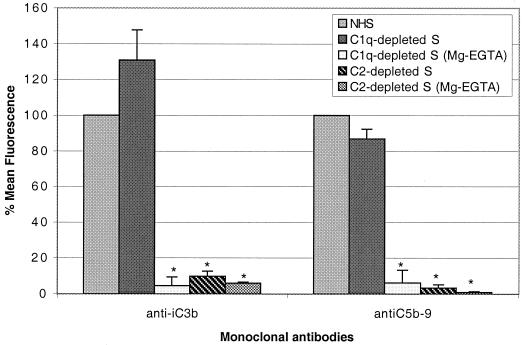

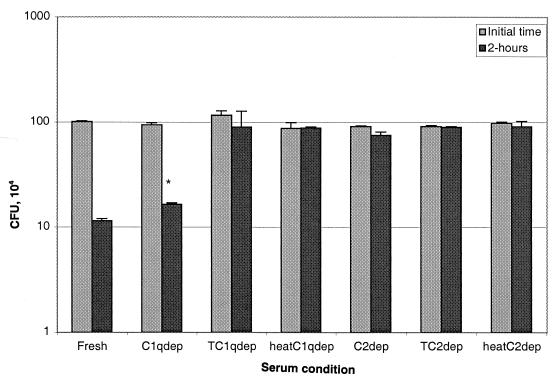

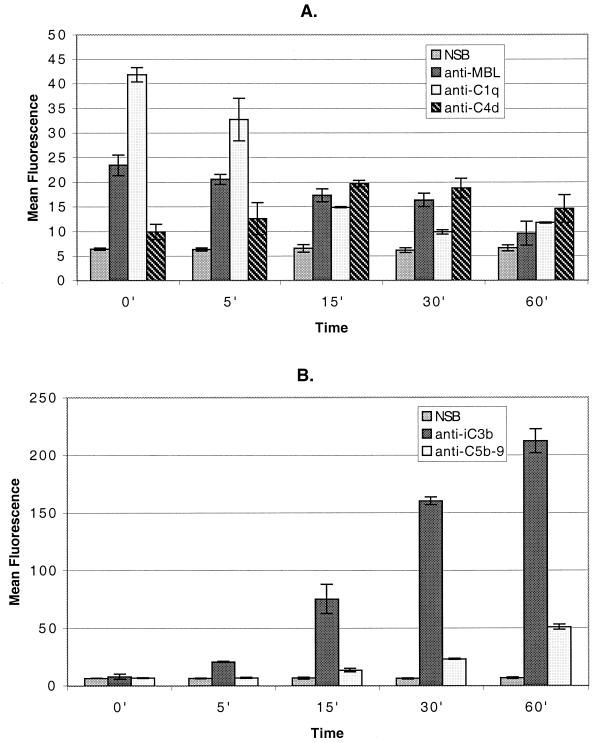

To determine the complement pathways involved in killing of rough B. abortus strains, we treated bacteria with nonimmune human serum depleted of certain complement components. C1q-depleted serum was used to determine whether only the classical pathway was involved. C2-depleted serum was included to determine if MBL also played a role in the killing of these bacteria. To determine the role of the alternative pathway, we treated some of these sera and NHS with Mg-EGTA, which inhibits the classical and collectin pathways but not the alternative pathway. Sera heated at 56°C for 30 min were used as controls, since this procedure inactivates complement completely. When C1q-depleted serum was used, the deposition of iC3b and C5b-9 was identical to the deposition when fresh NHS was used (Fig. 5), and the bactericidal activity of C1q-depleted serum (1 log10 reduction in 2 h) was identical to that of NHS (Fig. 6). In contrast, the use of C2-depleted serum resulted in a dramatic reduction in the binding of anti-iC3b (P = 0.014) and anti-C5b-9 (P = 0.008) (Fig. 5) and in almost complete inhibition of killing (Fig. 6). Furthermore, when C1q- or C2-depleted serum was treated with Mg-EGTA (to eliminate the classical and MBL pathways) or heated at 56°C for 30 min (to eliminate all complement activity), deposition of these two components (Fig. 5) and bacterial killing (Fig. 6) were completely abolished. Taken together, these data indicated that the alternative pathway did not mediate bacterial killing and that another, nonclassical pathway was playing a role. This possibility was confirmed by treating strain RB51 with 10% NHS and processing the cells for staining with anti-MBL and antibodies to other complement components either immediately or after 1 h of incubation. MBL, as well as C1q, were deposited very early on the surface of this strain. However, the amounts detected remained low or decreased after 1 h of incubation (Fig. 7).

FIG. 5.

Use of C1q- and C2-depleted NHS for complement pathway determination. Complement deposition of iC3b and C5b-9 on rough B. abortus strain RB51 was determined using fresh NHS, sera depleted of either C1q or C2, and depleted sera treated with Mg-EGTA as described in Materials and Methods. Cells were analyzed on a FACSort flow cytometer, and their respective mean fluorescence was compared to that obtained with fresh NHS and is shown as percentage. ∗, P < 0.03 compared to fresh NHS. Error bars show the means ± the SD of two different experiments.

FIG. 6.

Use of C1q- and C2-depleted NHS for complement pathway determination. Bactericidal assays were done by incubating the rough B. abortus RB51 strain with fresh NHS, C1q- and C2-depleted sera, depleted sera treated (T) with Mg-EGTA, and heat-depleted sera. The data represent the number of CFU/milliliter recovered at the initial time and after 2 h of incubation. ∗, Not significantly different from the number of CFU recovered after incubation with fresh NHS. Error bars show the SD from triplicate samples.

FIG. 7.

Classical and MBL-mediated pathways are involved in complement deposition on Brucella surfaces. RB51 was incubated with fresh NHS for different periods of time. Binding of complement components to bacteria was detected by staining and flow cytometric analysis. (A) Deposition of MBL, C1q, and C4d. (B) Deposition of iC3b and C5b-9. Note the difference in scale between panels A and B. Error bars show the means ± the SD of values from two different experiments.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we compared the deposition of complement components and the complement-mediated killing of smooth and rough mutants of B. abortus and B. melitensis. Although differences in susceptibility to serum between these two species (17, 58) and the role of O antigen in the resistance of Brucella to complement-mediated killing have been reported previously, most of these studies have been done using fortuitously isolated rough variants (9, 12, 13, 36). More recent work with genetically defined rough mutants has focused on understanding the effect of alterations in the synthesis of OPS on Brucella virulence, i.e., survival in macrophages and mice, but little or no information on the interactions of complement with these strains is available (3, 19, 29, 36, 55). RA1 and VTRM1, two rough mutant strains used in this study, were derived from virulent B. abortus 2308 or B. melitensis 16M, respectively (29, 55). Both rough mutants are defective only in the wboA gene encoding the enzyme glycosyltransferase. This gene is essential for the synthesis of O side chain in smooth strains of Brucella (29). Although strains RA1 and VTRM1 have identical mutations, RA1 strain was more sensitive to the bactericidal action of NHS, and more complement components were deposited on its surface than on strain VTRM1 (Fig. 1 to 4). Similar species-specific differences in both complement deposition and complement-mediated killing were also observed when strain RA1 was compared with another rough mutant of B. melitensis, WRR51 (Fig. 1 to 4). Strain WRR51 was derived from B. melitensis strain 16M by replacement of the internal region of the wboA gene with an antibiotic resistance cassette (Nikolich, unpublished) instead of having a transposon insertion on this gene, as in the case of VTRM1 or RA1 (55). There were no significant differences in either complement deposition or killing between VTRM1 and WRR51. Both strains were less susceptible than RA1 to the deposition of complement and complement-mediated killing. The vaccine strain RB51, a highly attenuated rough mutant derived by repeated in vitro passage of 2308 (40), was even more sensitive to the killing action of serum and deposited more complement components on its surface than RA1. Strains VTRM1 and WRR51 are attenuated in mice (55; Nikolich, unpublished), but not as much as strains RB51 or RA1 (23, 29, 41, 55). The reasons for the greater attenuation of RB51 are unknown but may be related to more profound deficiencies in OPS. In addition to a defect in wboA (50), RB51 also carries mutations in other gene(s) necessary for the expression of a smooth phenotype (51). Recently, McQuiston et al. have compared the LPS of strains RA1 and RB51 with the LPS of strain 2308 (29). Silver staining indicated that no O side chain was associated with LPS of strains RA1 or RB51, and compositional analysis of smooth and rough B. abortus LPS revealed that 2-keto-3-deoxy-d-manno-2-octulosonic acid (KDO) was the predominant glycose in the rough LPS (29). However, more mannose, galactose, and quinovosamine were found in RA1 than in RB51, suggesting than some components of the O side chain may be present in RA1 (29). It remains to be determined whether the differences between these glycoses are responsible for the complement-related differences observed in the present study and for the differences in virulence reported previously (29).

Our flow cytometric assays revealed that, in addition to depositing less complement on their surface, smooth strains of both B. abortus and B. melitensis released MAC quite readily (72 and 85%, respectively) when treated with 1 M NaCl as described for other serum-resistant organisms (14, 27). As previously shown with Aspergillius (21), Trypanosoma cruzi (45), Borrelia burgdorferi (6), Yersinia enterocolitica (34), and Helicobacter pylori (38), the diminished binding of complement components seems to be related to pathogenicity. It is possible that the increased virulence of rough B. melitensis compared to B. abortus strains for mice is related to decreased susceptibility to complement-mediated lysis. This decreased susceptibility in turn may be due to reduced deposition of complement components on the bacterial surface, since we did not detect differences between rough B. melitensis and B. abortus in the strength of the MAC attachment. It is possible that differences in the strength of the MAC attachment exist but were not detectable by the method used. It is also possible that other interactions of complement components with the bacterial membrane may mediate the differences in susceptibility to lysis between rough B. melitensis and B. abortus strains.

We speculate that these differences may be related to differential expression of OMP in the two species. Although the genus Brucella is highly homogeneous at the DNA level (52), major differences and diversity among Brucella species are found in the major OMP. OMP are exposed on the bacterial surface but are less accessible to complement in smooth strains than in rough strains (8, 13, 31, 32). Both the OPS length and the proportion of S-LPS on the bacterial surface influence the ability to shield bacteria from complement-mediated killing (4, 31, 32). Brucella OMP have been classified according to their apparent molecular mass as major 25- to 30-kDa, 31- to 34-kDa, and 36- to 38-kDa proteins and minor 10-, 16-, 19-, and 89-kDa proteins (5). Interestingly, the OMP of 31 to 34 kDa is tightly associated with the peptidoglycan and is the most exposed OMP in smooth B. melitensis and B. suis strains (8, 28). Remarkably, no binding of anti-31- to 34-kDa OMP MAb to B. abortus strains is detected by immunoblotting (53), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, flow cytometry, or immunoelectron microscopy assays (5, 28). Furthermore, hybridization studies have shown that the omp-31 gene is absent in B. abortus strains (54). This gene is included in a multigenic, 10-kb segment present in B. suis, B. melitensis, B. ovis, and B. canis but lacking in B. abortus (8, 54). This observation raises several intriguing questions in view of our findings in the present report. Does OMP-31 or perhaps another product(s) of this 10-kb region play a role in resistance to the bactericidal action of complement observed in both rough and smooth strains of B. melitensis? If so, is this resistance an important determinant of pathogenicity not only for B. melitensis but for other brucellae as well? We plan to address these issues in further studies.

Our findings indicate that binding of iC3b and C5b-9 to the Brucella surface is mediated primarily through the classical and MBL-mediated pathways without activation of the alternative pathway. These results are consistent with previous studies demonstrating that the bactericidal action of serum against B. abortus is due to effects of the classical and not the alternative pathway (9, 13, 22, 23). In addition, our results provide evidence for the first time that MBL may also play a role in host defense against Brucella. MBL has been increasingly recognized as a key protein in innate immunity (7, 10, 20, 24, 35, 46, 47, 49). A member of the collectin family, MBL is structurally related to C1q, the first subcomponent of the classical complement pathway, and to SP-A (24, 39, 46, 47, 49). The collectins are characterized by the presence of two major domains: a collagen-like and a lectin domain. The lectin domain of MBL mediates binding to carbohydrates on microorganisms. Consequent conformational changes in the collagen-like domains induce C4-converting activity, and complement activation proceeds via C4 and C2 as in the classical pathway (20, 24, 43, 46, 47). In our studies, the absence of iC3b on bacteria incubated with C2-depleted serum and the presence of iC3b on bacteria incubated with C1q-deficient serum indicate that deposition of MBL plays a functional role in complement activation on Brucella. C1q does not have a lectin domain and, for that reason, sugar-binding activity is not observed. However, in addition to its well-known ability to bind to immunoglobulin Fc regions in antigen-antibody complexes, C1q can also bind directly to pathogenic bacteria (15). In our study, using nonimmune serum, C1q and MBL both deposited more readily on the surface of rough Brucella than on smooth Brucella. However, the intensity of their binding was very low compared to other complement components (Fig. 6). This may reflect the amplification characteristics of the complement cascade: one C142 or presumably the analogous MBL-containing complex can activate numerous C3 molecules.

These studies make three important points. First, the amount of complement deposition and/or strength of association of the MAC with the bacterial surface are important determinants of the ability of serum to kill Brucella. Second, the presence of OPS on the bacterial surface cannot be the only factor causing the inhibition of binding of complement components observed in the more virulent organisms. Third, MBL and C1q both initiate antibody-independent complement activation and brucellacidal activity. Further investigations are needed to define the role of MBL in the immune response to Brucella. Collectins not only activate complement but may also influence cellular activation via specific receptors on macrophages and other immune effectors. The interactions of complement components, Brucella, and macrophages are an intriguing subject for additional studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Elzbieta Zelazowska for practical advice with the flow data.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alberti S, Alvarez D, Merino S, Casado M T, Vivanco F, Tomas J M, Benedi V J. Analysis of complement C3 deposition and degradation on Klebsiella pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4726–4732. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4726-4732.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alberti S, Marques G, Hernandez-Alles S, Rubires X, Tomas J M, Vivanco F, Benedi V J. Interaction between complement subcomponent C1q and the Klebsiella pneumoniae porin OmpK36. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4719–4725. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4719-4725.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen C A, Adams L G, Ficht T A. Transposon-derived Brucella abortus rough mutants are attenuated and exhibit reduced intracellular survival. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1008–1016. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.1008-1016.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bowden R A, Cloekaert A, Zygmunt M S, Bernard S, Dubray G. Surface exposure of outer membrane protein and lipopolysaccharide epitopes in Brucella species studied by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and flow cytometry. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3945–3952. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.10.3945-3952.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowden R A, Cloekaert A, Zygmunt M S, Bernard S, Dubray G. Outer-membrane protein- and rough lipopolysaccharide-specific monoclonal antibodies protect mice against Brucella ovis. J Med Microbiol. 1995;43:344–347. doi: 10.1099/00222615-43-5-344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breitner-Ruddock S, Wurzner R, Schulze J, Brade V. Heterogeneity in the complement-dependent bacteriolysis within the species of Borrelia burgdorferi. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1997;185:253–60. doi: 10.1007/s004300050038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carroll M C. The role of complement and complement receptors in induction and regulation of immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:545–568. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cloeckaert A, Verger J, Grayon M, Vizcaino N. Molecular and immunological characterization of the major outer membrane proteins of Brucella. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;145:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08547.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corbeil L B, Blau K, Inzana T J, Nielsen K H, Jacobson R H, Corbeil R R, Winter A J. Killing of Brucella abortus by bovine serum. Infect Immun. 1988;56:3251–3261. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.12.3251-3261.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaka W, Verheul A F M, Vaishnav V V, Cherniak R, Scharringa J, Verhoef J, Snippe H, Hoepelman A I M. Induction of TNF-α in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells by the mannoprotein of Cryptococcus neoformans involves human mannose binding protein. J Immunol. 1997;159:2979–2985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.China B, Sory M P, N'guyen B T, de Bruyere M, Cornelis G R. Role of the YadA protein in prevention of opsonization of Yersinia enterocolitica by C3b molecules. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3129–3136. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.8.3129-3136.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eisenschenk F C, Houle J J, Hoffmann E M. Serum sensitivity of field isolates and laboratory strains of Brucella abortus. Am J Vet Res. 1995;56:1592–1598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eisenschenk F C, Houle J J, Hoffmann E M. Mechanism of serum resistance among Brucella abortus isolates. Vet Microbiol. 1999;68:235–244. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1135(99)00075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Egan A M, Gordon D L. Burkholderia pseudomallei activates complement and is ingested but not killed by polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4952–4959. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.4952-4959.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eggleton P, Reid K B M, Tenner A J. C1q-how many functions? How many receptors? Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:428–431. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01373-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Esser A F. The membrane attack complex of complement: assembly, structure and cytotoxic activity. Toxicology. 1994;87:229–247. doi: 10.1016/0300-483x(94)90253-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gallego M C, LaPena M A. The interaction of Brucella melitensis 16-M and caprine polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Comp Immun Microbiol Infect Dis. 1990;13:59–65. doi: 10.1016/0147-9571(90)90517-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gemmell C H. A flow cytometric immunoassay to quantify adsorption of complement activation products (iC3b, C3d, SC5b-9) on artificial surfaces. J Biomed Mater Res. 1997;37:474–480. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4636(19971215)37:4<474::aid-jbm5>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Godfroid F, Taminiau B, Danese I, Denoel P, Tibor A, Weynants V, Cloeckaert A, Godfroid J, Letesson J. Identification of the perosamine synthetase gene of Brucella melitensis 16M and involvement of lipopolysaccharide O side chain in Brucella survival in mice and in macrophages. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5485–5493. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5485-5493.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hansen S, Holmskov U. Structural aspects of collectins and receptors for collectins. Immunobiology. 1998;199:165–189. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(98)80025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henwick S, Hetherington S V, Patrick C C. Complement binding to Aspergillus conidia correlates with pathogenicity. J Lab Clin Med. 1993;122:27–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoffmann E M, Kellogg W L, Houle J J. Inhibition of complement-mediated killing of Brucella abortus by fluid-phase immunoglobulins. Am J Vet Res. 1994;55:810–814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoffmann E M, Houle J J. Contradictory roles for antibody and complement in the interaction of Brucella abortus with its host. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1995;21:153–163. doi: 10.3109/10408419509113538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holmskov U, Malhotra R, Sim R B, Jensenius J C. Collectins: collagenous C-type lectins of the innate immune defense system. Immunol Today. 1994;15:67–74. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hortsmann R D. Target recognition failure by the nonspecific defense system: surface constituents of pathogens interfere with the alternative pathway of complement activation. Infect Immun. 1992;60:721–727. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.721-727.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jack D L, Dodds A W, Anwar N, Ison C A, Law A, Frosch M, Turner M W, Klein N J. Activation of complement by mannose-binding lectin on isogenic mutants of Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B. J Immunol. 1998;160:1346–1353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joiner K A, Warren K A, Hammer C, Frank M M. Bactericidal but not nonbactericidal C5b-9 is associated with distinctive outer membrane proteins in Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Immunol. 1985;134:1920–1925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kroll H P, Bhakdi S, Taylor P W. Membrane changes induced by exposure of Escherichia coli to human serum. Infect Immun. 1983;42:1055–1066. doi: 10.1128/iai.42.3.1055-1066.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McQuiston J R, Vemulapalli R, Inzana T J, Shurig G G, Sriranganathan N, Fritzinger D, Hadfield T L, Warren R A, Snellings N, Hoover D, Halling S M, Boyle S M. Genetic characterization of a Tn5-disrupted glycosyltransferase gene homolog in Brucella abortus and its effect on lipopolysaccharide composition and virulence. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3830–3835. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.3830-3835.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meikle P J, Perry M B, Cherwonogrodzky J W, Bundle D R. Fine structure of A and M antigens from Brucella biovars. Infect Immun. 1989;57:2820–2826. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.9.2820-2828.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Merino S, Rubires X, Aguilar A, Alberti S, Hernandez-Alles S, Benedi V J, Tomas J M. Mesophilic Aeromonas sp. serogroup O:11 resistance to complement-mediated killing. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5302–5309. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5302-5309.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Merino S, Nogueras M M, Aguilar A, Rubieres S, Alberti S, Benedi V J, Tomas J M. Activation of the complement classical pathway (C1q binding) by mesophilic Aeromonas hydrophila outer membrane protein. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3825–3831. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3825-3831.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morgan B P. Physiology and pathophysiology of complement: progress and trends. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 1995;32:265–298. doi: 10.3109/10408369509084686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pilz D, Vocke T, Heesemann J, Brade V. Mechanism of YadA-mediated serum resistance of Yersinia enterocolitica serotype O3. Infect Immun. 1992;60:189–195. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.1.189-195.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Polostky V Y, Belisle J T, Mikusova K, Ezekowitz R A B, Joiner K A. Interaction of human mannose-binding protein with Mycobacterium avium. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:1159–1168. doi: 10.1086/520354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Price R E, Templeton J W, Adams L G. Survival of smooth, rough and transposon mutant strains of Brucella abortus in bovine mammary macrophages. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1990;26:353–365. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(90)90119-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robertson M. Innate immunity. Curr Biol. 1998;8:R595–R597. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70384-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rokita E, Makristathis A, Presterl E, Rotter M L, Hirschi A M. Helicobacter pylori urease significantly reduces opsonization by human complement. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:1521–1525. doi: 10.1086/314459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sano H, Sohma H, Muta T, Nomura S, Voelker D R, Kuroki Y. Pulmonary surfactant protein A modulates the cellular response to smooth and rough lipopolysaccharides by interaction with CD14. J Immunol. 1999;163:387–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shurig G G, Roop II R M, Bagchi T, Boyle S M, Burman D, Sriranganathan N. Biological properties of RB51: a stable rough strain of Brucella abortus. Vet Microbiol. 1991;28:171–188. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(91)90091-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shurig G G. 50th anniversary meeting of brucellosis research conference. Chicago, Ill: IDEXX Laboratories, Inc.; 1997. Brucellosis vaccines: past, present and future; pp. 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taylor P W, Kroll H P. Interaction of human complement proteins with serum-sensitive and serum-resistant strains of Escherichia coli. Mol Immunol. 1984;21:609–620. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(84)90046-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thiel S, Vorup-Jensen T, Stover C M, Schwaeble W, Laursen S B, Poulsen K, Willis A C, Eggleton P, Hansen S, Holmskov U, Reid K B M, Jensenius J C. A second serine protease associated with mannan-binding lectin that activates complement. Nature. 1997;386:506–510. doi: 10.1038/386506a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tomlinson S. Complement defense mechanisms. Curr Opin Immunol. 1993;5:83–89. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(93)90085-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tomlinson S, Pontes de Carvalho L C, Vandekerckhove F, Nussenzqweig V. Role of sialic acid in the resistance of Trypanosoma cruzi trypomastigotes to complement. J Immunol. 1994;153:3141–3147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Turner M W. Mannose-binding lectin: the pluripotent molecule of the innate immune system. Immunol Today. 1996;17:532–540. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)10062-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Turner M W. Mannose-binding lectin (MBL) in health and disease. Immunobiology. 1998;199:327–339. doi: 10.1016/S0171-2985(98)80037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van den Berg R H, Faber-Krol M C, van de Klundert J A M, van Es L A, Daha M R. Inhibition of the hemolytic activity of the first component of complement C1 by an Escherichia coli C1q binding protein. J Immunol. 1996;156:4466–4473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vasta G R, Quesenberry M, Ahmed H, O'Leary N. C-type lectins and galectins mediate innate and adaptive immune functions: their roles in the complement activation pathway. Dev Comp Immunol. 1999;23:401–420. doi: 10.1016/s0145-305x(99)00020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vemulapalli R, McQuiston J R, Schurig G G, Sriranganathan N, Halling S M, Boyle S M. Identification of an IS711 element interrupting the wboA gene of Brucella abortus vaccine strain RB51 and a PCR assay to distinguish strain RB51 from other Brucella species and strains. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1999;6:760–764. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.5.760-764.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vemulapalli R, He Y, Buccolo L S, Boyle S M, Sriranganathan N, Schurig G G. Complementation of Brucella abortus RB51 with a functional wboA gene results in O-antigen synthesis and enhanced vaccine efficacy but no change in rough phenotype and attenuation. Infect Immun. 2000;68:3927–3932. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.7.3927-3932.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Verger J M, Grimont F, Grimont P A D, Grayon M. Brucella a monospecific genus as shown by deoxyribonucleic acid hybridization. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1985;35:292–295. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vizcaino N, Verger J M, Grayon M, Zygmunt M S, Cloeckaert A. DNA polymorphism at the omp-31 locus of Brucella spp.: evidence for a large deletion in Brucella abortus, and other species-specific markers. Microbiology. 1997;143:2913–2921. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-9-2913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vizcaino N, Cloeckaert A, Zygmunt M S, Fernandez-Lago L. Molecular characterization of a Brucella species large DNA fragment deleted in Brucella abortus strains: evidence for a locus involved in the synthesis of a polysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2700–2712. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.2700-2712.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Winter A J, Schurig G G, Boyle S M, Sriranganathan N, Bevins J S, Enright F M, Elzer P H, Kopec J D. Protection of BALB/c mice against homologous and heterologous species of Brucella by rough strain vaccines derived from Brucella melitensis and Brucella suis biovar 4. Am J Vet Res. 1996;57:677–683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wurzner R. Evasion of pathogens by avoiding recognition or eradication by complement, in part via molecular mimicry. Mol Immunol. 1999;36:249–260. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(99)00049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Young E J. Human brucellosis. Rev Infect Dis. 1983;5:821–842. doi: 10.1093/clinids/5.5.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Young E J, Borchert M, Kretzer F L, Musher D M. Phagocytosis and killing of Brucella by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Infect Dis. 1985;151:682–690. doi: 10.1093/infdis/151.4.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]