Abstract

Background

We compared cardiac outcomes for surgery‐eligible patients with stage III non‐small‐cell lung cancer treated adjuvantly or neoadjuvantly with chemotherapy versus chemo‐radiation therapy in the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results‐Medicare database.

Methods and Results

Patients were age 66+, had stage IIIA/B resectable non‐small‐cell lung cancer diagnosed between 2007 and 2015, and received adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemo‐radiation within 121 days of diagnosis. Patients having chemo‐radiation and chemotherapy only were propensity‐score matched and followed from day 121 to first cardiac outcome, noncardiac death, radiation initiation by patients who received chemotherapy only, fee‐for‐service enrollment interruption, or December 31, 2016. Cause‐specific hazard ratios (HRs) and competing risks subdistribution HRs were estimated. The primary outcome was the first of these severe cardiac events: acute myocardial infarction, other hospitalized ischemic heart disease, hospitalized heart failure, percutaneous coronary intervention/coronary artery bypass graft, cardiac death, or urgent/inpatient care for pericardial disease, conduction abnormality, valve disorder, or ischemic heart disease. With median follow‐up of 13 months, 70 of 682 patients who received chemo‐radiation (10.26%) and 43 of 682 matched patients who received chemotherapy only (6.30%) developed a severe cardiac event (P=0.008) with median time to first event 5.45 months. Chemo‐radiation increased the rate of severe cardiac events (cause‐specific HR: 1.62 [95% CI, 1.11–2.37] and subdistribution HR: 1.41 [95% CI, 0.97–2.04]). Cancer severity appeared greater among patients who received chemo‐radiation (noncardiac death cause‐specific HR, 2.53 [95% CI, 1.93–3.33] and subdistribution HR, 2.52 [95% CI, 1.90–3.33]).

Conclusions

Adding radiation therapy to chemotherapy is associated with an increased risk of severe cardiac events among patients with resectable stage III non‐small‐cell lung cancer for whom survival benefit of radiation therapy is unclear.

Keywords: cardiac effects, cardio‐oncology, epidemiology, non‐small‐cell lung cancer, radiation effects

Subject Categories: Cardiovascular Disease, Aging, Mortality/Survival, Complications, Cardio-Oncology

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CSHR

cause‐specific hazard ratio

- CTCAE

clinical trial common adverse event

- MACE

major adverse cardiac events

- NSCLC

non‐small‐cell lung cancer

- SEER

Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results

- SDHR

subdistribution hazard ratio

- 3DCRT

3‐dimensional conformal radiation therapy

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

This study is the first to evaluate whether concurrent chemotherapy and radiation is associated with greater cardiotoxicity compared with chemotherapy alone among a contemporary population‐based cohort of patients with resectable stage III non‐small‐cell lung cancer.

Radiation to the thoracic region may increase the risk of severe cardiovascular events among patients with operable stage III lung cancer who received chemotherapy.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Treatment decision‐making for lung cancer should be a multidisciplinary effort between cardiologists and oncologists, weighing the safety of combined chemotherapy and radiation against the not‐yet‐demonstrated survival benefit above chemotherapy alone.

Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality are elevated among survivors of adult‐onset lung, lymphoma, and breast cancers compared with noncancer controls, and a causal role for therapeutic exposures is suggested by absence of stage‐ and age‐adjusted increased risk among patients who receive only surgery. 1 For patients with malignancies involving the thoracic region, the therapeutic benefits of radiation therapy may be offset to some extent by effects on the heart. 2 Much of this evidence is from population‐based studies of breast cancer where more contemporary efforts to reduce exposure to the heart may have reduced the radiation‐associated cardiac risk. 3 , 4 , 5 However, it can be more difficult to protect the heart from radiation damage for treatment of lung cancer. 6 Pooled analyses of clinical trials 7 , 8 and a recent large retrospective chart review case series 9 of patients with radiation‐treated locally advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer (NSCLC) have verified radiation dose to the heart as a contributor to major adverse cardiac events (MACE) within the first 2 years after lung cancer diagnosis. 9

The benefits and risks of radiation therapy in patients with resectable stage IIIA NSCLC are inconclusive. 10 The purpose of our study was to assess the effect of chemo‐radiation treatment on cardiac outcomes when compared with chemotherapy only in a large population‐based cohort study of patients with surgically treatable stage III NSCLC who were age 66 or older at the time of their cancer diagnosis. Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER)‐Medicare cohort studies have previously reported cardiac outcomes associated with radiation therapy in patients with small cell lung cancer 11 and any‐stage NSCLC. 12 Our study adds to this literature with more contemporary data and by directly comparing chemo‐radiation to chemotherapy alone for surgically treatable stage III NSCLC.

METHODS

The SEER‐Medicare data are available with National Cancer Institute and SEER approval of specific research protocols in order to protect the confidentiality and privacy of patients and providers; instructions for obtaining the data are available at https://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/seermedicare/obtain/. Definitions of all variables used in this study (ie, billing codes) are available in the supplemental material to facilitate replication of this study's procedures.

The project was submitted to the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board, which determined it to not meet the regulatory definition of human subjects research and therefore did not require review by the Institutional Review Board, because this project is limited to analysis of deidentified public health and Medicare data.

Study Design

This propensity score‐matched retrospective cohort study of the SEER‐Medicare database 13 included patients diagnosed with histologically or microscopically confirmed stage III NSCLC between January 1, 2007 and December 31, 2015 (see Figure S1 for depiction of study design). Medicare claims data were used to identify patients who received cytotoxic chemotherapy with or without radiation treatment (ie, chemo‐radiation versus chemotherapy only) within an exposure assessment window from diagnosis through 4 months after diagnosis. The follow‐up period for cardiac event outcomes began upon completion of the exposure assessment window (ie, 4 months or 121 days after diagnosis) and ended at the earliest of the following: the first cardiac outcome of interest, noncardiac death, initiation of radiation therapy by a nonuser, or end of available Medicare claims (owing to discontinuation of full fee‐for‐service enrollment or December 31, 2016 [the last date of available claims data]). Baseline comorbidity covariates were assessed from claims any time before the diagnosis date, function‐related indicators were assessed for 1 year before diagnosis, and immunotherapy and hormonal therapy use was assessed from claims for encounters occurring during the exposure assessment window. Characteristics from SEER were used to assess exclusion criteria (Figure 1 – flow diagram) and some covariates.

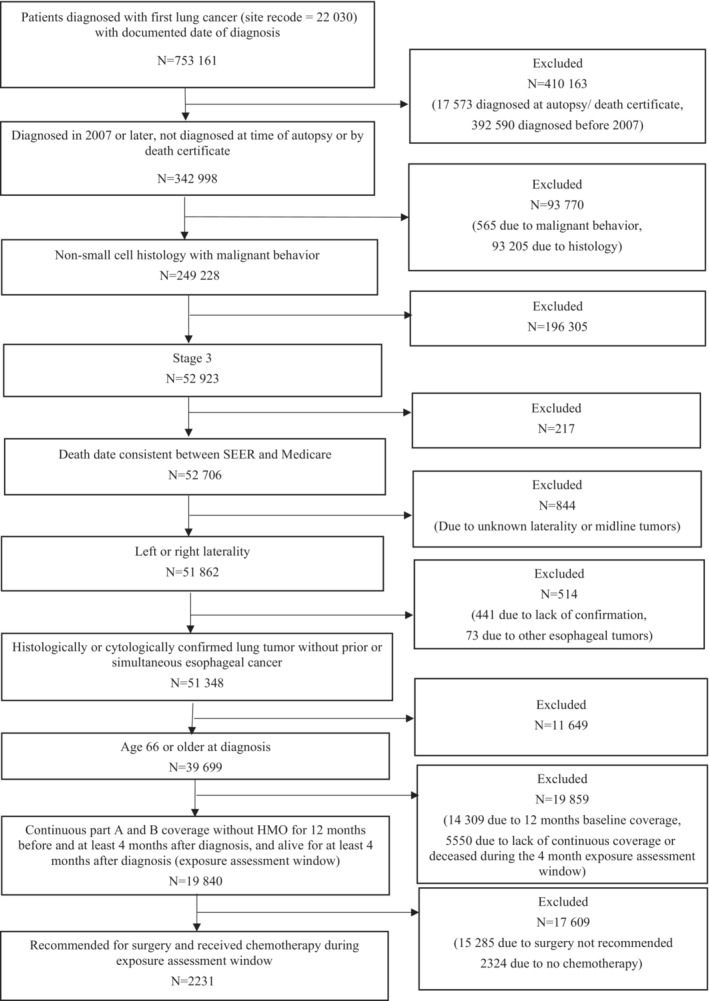

Figure 1. Flow diagram describing application of exclusion criteria to select the study sample.

HMO indicates health maintenance organization; and SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

Measures

Tables S1 and S2 provide all diagnosis and procedure codes and associated rules used to define treatments, cardiac outcomes, and covariates from Medicare claims. The primary outcome, composite severe cardiac event, included any severe cardiac outcome. Severe cardiac outcomes were defined to approximate well‐accepted American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology‐defined MACE end points for clinical trials 14 and grade 3 National Cancer Institute clinical trial common adverse event (CTCAE) definitions. 15 MACE included cardiac death, acute myocardial infarction, hospitalized heart failure, hospitalized ischemic heart disease (other than acute myocardial infarction), and percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass graft procedure. To approximate grade 3 or higher CTCAE, we included inpatient or urgent care encounters for ischemic heart disease, valve disorders/thoracic aortic disease, arrhythmia/conduction disorders, heart failure/cardiomyopathy/myocarditis, and pericardial disease operationalized as a first position diagnosis code on a hospitalization or emergency department encounter (Medicare Provider Analysis and Review/inpatient claim or emergency department revenue center code on an outpatient facility claim).

Covariates included sociodemographic factors (age, diagnosis year, and whether receiving a low‐income subsidy or state buy‐in), prediagnosis history of cardiac conditions, other cardiac risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, smoking), other individual comorbidities and a comorbidity summary score (as measured by the National Cancer Institute comorbidity index 16 ), individual frailty indicators and a count of those indicators, 17 and immunotherapy and hormonal therapy use.

Statistical Analysis

Propensity scores were estimated using logistic regression, with each patient treated with chemo‐radiation matched to 1 patient who received chemotherapy only, using greedy nearest neighbor matching with a caliper of 0.25 on the logit of propensity score scale. Additionally, pairs were required to have an exact match on laterality and year of diagnosis. Balance on covariates before and after matching was assessed using standardized differences. Standardized differences <0.1 were considered to indicate robust matching.

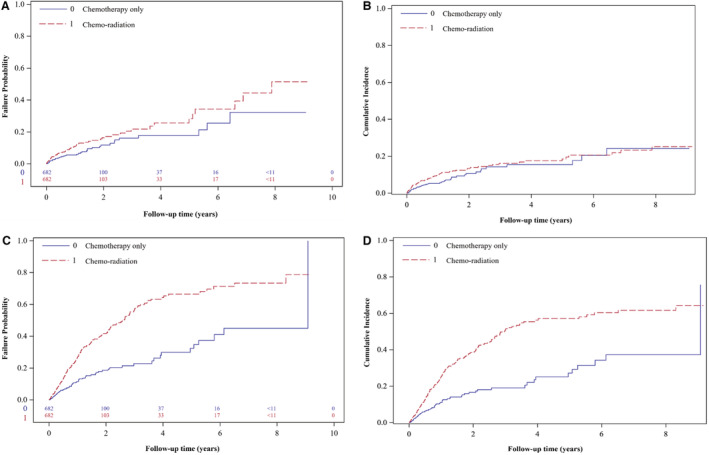

Clinically we are interested in the cumulative incidence, the expected proportion of patients who will have a cardiac event over the course of time. When there are competing risks (eg, noncardiac death), multivariable analyses commonly use Cox proportional cause‐specific hazard models and/or proportional subdistribution hazards models. Reporting both analysis approaches may provide a more complete understanding of the dynamics of competing events over time. 18 As recommended by Latouche et al, 18 descriptive cumulative cause‐specific hazards and cumulative incidence plots were produced for the composite cardiac outcome and noncardiac death to illustrate the time course of these events.

Competing risk analyses were conducted to assess the relationship of chemo‐radiation versus chemotherapy‐only treatment with the composite outcome and the individual cardiac outcomes. Cox proportional hazards models were used to estimate cause‐specific hazard ratios (CSHRs) and Fine–Gray (competing risks) regressions were used to estimate subdistributio hazard ratios (SDHRs) for all cardiac outcomes and for the competing event (noncardiac death). 18 Additionally, 2‐year cumulative incidence (ie, the probability of an event within the first 2 years of follow‐up) estimates were generated from the Fine–Gray competing risks model's cumulative incidence function.

Originally, we opted not to test the proportional hazards assumption for theoretical and practical considerations. Nonproportional hazards are typical in medical studies for reasons such as changes in the effect of treatment on the outcome over time or differences in susceptibility to the outcome, in which high‐risk patients experience events early and those surviving longer being less susceptible. 19 Large sample sizes and long duration of follow‐up are likely to yield statistically significant tests of proportional hazards. Accordingly, Stensrud and Hernán posit statistical testing for proportional hazards is unnecessary. 19

In an ad hoc analysis, we assessed the proportional hazards assumption visually and mathematically for the primary outcome of interest (any cardiac event) and the competing event (noncardiac death). The Kaplan–Meier survival curves and log‐negative‐log plots for the primary outcome and competing event appeared proportional between patients who received chemo‐radiation and and those who received chemotherapy only. The Kaplan–Meier curves for any cardiac event narrowed but did not cross, past 6 years of follow‐up, which is to be expected with a long duration of follow‐up. 19 We tested for an interaction between follow‐up time and treatment group (a significant interaction reflecting violation of the proportional hazards assumption); the treatment‐time interaction was not significant for the outcome or competing event.

Individuals were followed from 121 days after diagnosis through the first of the cardiac outcomes of interest, noncardiac death, initiation of radiation therapy by a nonuser, interruption of full fee‐for‐service enrollment, or December 31, 2016. Follow‐up time for both members of a matched pair ended when the earliest end of follow‐up for the pair was because of censoring (ie, radiation initiation by a patient who received chemotherapy only or discontinuation of fee‐for‐service coverage). That is, for each matched pair, if the member with the shortest follow‐up was censored, that follow‐up time was also used as the end of follow‐up for the other member of the pair. For estimating cause‐specific hazard of cardiac events, occurrence of the competing event (noncardiac death) also qualifies as a censoring event and vice versa (ie, cardiac event counts as censoring for the cause‐specific hazard of the competing event, noncardiac death). For Fine–Gray analyses, the competing event is not considered to be a censoring event.

To explore whether greater heart dose modified this association, a planned exploratory analysis examined whether patients with left‐sided laterality tumors, compared with right, had a greater difference in rate of cardiac events between patients with chemo‐radiation and patients with chemotherapy only. This was quantified with the relative excess risk because of interaction, a standard measure for interaction on the additive scale, with CIs computed via the multivariate delta method. 20 , 21 , 22 Another sensitivity analysis included only new‐onset outcomes (eg, atrial fibrillation encounters were counted as an outcome only if the patient had no history of atrial fibrillation before lung cancer diagnosis).

RESULTS

Of 2231 patients who met eligibility criteria (Figure 1), 1364 patients were propensity score matched. Before matching, the median age of this chemotherapy‐treated cohort was 72 years (interquartile range: 69–76), mean (SD) age was 72.8 (4.9), 46% were female, and 803 (36%) had radiation treatment initiated during the 4‐month postdiagnosis exposure assessment window. Patients often had prevalent cardiac disease before diagnosis, with 8.9% (n=199) having had prior evidence of a MACE. The prevalence of conduction abnormality, heart failure, ischemic heart disease, and valve disorder each exceeded 10% before diagnosis (Table 1). The groups were well balanced on covariates after matching (Table 1).

Table 1.

Covariate Balance Before and After Matching

| Before matching (n=2231) | After matching¶ (n=1364) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate | Chemoradiation (N=803) mean (SD) | Chemotherapy only (N=1428) mean (SD) | Standardized difference | Chemoradiation (N=682) mean (SD) | Chemotherapy only (N=682) mean (SD) | Standardized difference |

| Tumor characteristics (as documented in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results cancer file for the primary cancer diagnosis) | ||||||

| Tumor size, mm | 44.72 (32.62) | 40.89 (27.28) | 0.13 | 42.10 (22.81) | 41.99 (24.80) | 0.00 |

| N0 nodal status | 0.11 (0.32) | 0.12 (0.33) | −0.03 | 0.11 (0.31) | 0.11 (0.32) | −0.01 |

| N1 nodal status | 0.11 (0.31) | 0.17 (0.38) | −0.18 | 0.11 (0.31) | 0.12 (0.33) | −0.05 |

| N2 nodal status | 0.74 (0.44) | 0.69 (0.46) | 0.11 | 0.77 (0.42) | 0.75 (0.43) | 0.03 |

| N3 nodal status | 0.04 (0.19) | 0.02 (0.13) | 0.13 | 0.02 (0.13) | 0.01 (0.11) | 0.04 |

| Age at diagnosis, y | 72.41 (5.01) | 73.01 (4.88) | −0.12 | 72.47 (4.94) | 72.59 (4.68) | −0.02 |

| Year of diagnosis | 2011 (2.59) | 2011 (2.62) | −0.08 | 2011 (2.60) | 2011 (2.60) | 0.00 |

| Left laterality (of primary tumor) | 0.41 (0.49) | 0.43 (0.50) | −0.05 | 0.40 (0.49) | 0.40 (0.49) | 0.00 |

| Stage IIIA at diagnosis (vs IIIB) | 0.80 (0.40) | 0.83 (0.38) | −0.06 | 0.83 (0.38) | 0.83 (0.37) | −0.01 |

| Demographics (as documented in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results cancer file at the time of the primary cancer diagnosis) | ||||||

| White race | 0.91 (0.28) | 0.92 (0.28) | −0.01 | 0.91 (0.28) | 0.91 (0.29) | 0.03 |

| Black race | 0.06 (0.23) | 0.04 (0.20) | 0.08 | 0.06 (0.23) | 0.04 (0.20) | 0.08 |

| Other race†† | 0.03 (0.17) | 0.04 (0.20) | −0.08 | 0.03 (0.17) | 0.05 (0.23) | −0.12 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 0.04 (0.19) | 0.04 (0.21) | −0.03 | 0.04 (0.20) | 0.05 (0.21) | −0.04 |

| Married at diagnosis | 0.58 (0.49) | 0.64 (0.48) | −0.11 | 0.59 (0.49) | 0.65 (0.48) | −0.13 |

| Male sex | 0.58 (0.49) | 0.51 (0.50) | 0.13 | 0.56 (0.50) | 0.54 (0.50) | 0.06 |

| State buy‐in Medicare subsidy | 0.12 (0.32) | 0.11 (0.31) | 0.03 | 0.11 (0.31) | 0.11 (0.31) | 0.00 |

| Treatment characteristics# (identified via International Classification of Diseases diagnosis and Current Procedural Terminology/Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes during the exposure assessment window) | ||||||

| Immunotherapy‡ | 0.02 (0.13) | 0.07 (0.25) | −0.25 | 0.02 (0.13) | 0.01 (0.11) | 0.04 |

| Hormonal therapy‡ | 0.93 (0.26) | 0.86 (0.34) | 0.21 | 0.92 (0.27) | 0.92 (0.27) | 0.01 |

| Baseline cardiac conditions (any time before index cancer diagnosis) | ||||||

| Atrial fibrillation* , § | 0.11 (0.31) | 0.10 (0.30) | 0.02 | 0.10 (0.30) | 0.10 (0.30) | 0.00 |

| Arrhythmia or conduction abnormality* , § | 0.22 (0.41) | 0.22 (0.42) | −0.02 | 0.22 (0.42) | 0.23 (0.42) | −0.01 |

| Heart failure* , § | 0.11 (0.32) | 0.11 (0.31) | 0.02 | 0.11 (0.32) | 0.11 (0.32) | −0.00 |

| Ischemic heart disease* , § | 0.35 (0.48) | 0.34 (0.47) | 0.01 | 0.34 (0.47) | 0.36 (0.48) | −0.03 |

| Pericardial disease* , § | 0.00 (0.07) | 0.01 (0.08) | −0.03 | 0.01 (0.08) | 0.00 (0.07) | 0.02 |

| Valve disorders or thoracic aortic disease* , § | 0.14 (0.34) | 0.15 (0.36) | −0.05 | 0.14 (0.34) | 0.13 (0.34) | 0.00 |

| Hospitalized heart failure* , ǁ | 0.01 (0.12) | 0.01 (0.11) | 0.01 | 0.02 (0.13) | 0.01 (0.12) | 0.01 |

| Hospitalized ischemic heart disease* , ǁ | 0.07 (0.25) | 0.06 (0.24) | 0.02 | 0.06 (0.24) | 0.06 (0.23) | 0.02 |

| Acute myocardial infarction* , ǁ | 0.03 (0.18) | 0.03 (0.17) | 0.03 | 0.03 (0.16) | 0.03 (0.16) | 0.00 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention/coronary artery bypass graft* , ǁ | 0.08 (0.27) | 0.07 (0.26) | 0.01 | 0.07 (0.25) | 0.07 (0.26) | −0.02 |

| Comorbidities* (any time before index cancer diagnosis) | ||||||

| NCI‐weighted comorbidity index* | 2.46 (2.33) | 2.48 (2.31) | −0.01 | 2.39 (2.31) | 2.41 (2.28) | −0.01 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease* | 0.46 (0.50) | 0.47 (0.50) | −0.02 | 0.45 (0.50) | 0.46 (0.50) | −0.02 |

| Cerebrovascular disease* | 0.21 (0.41) | 0.18 (0.39) | 0.07 | 0.21 (0.41) | 0.20 (0.40) | 0.01 |

| Dementia* | 0.01 (0.11) | 0.01 (0.10) | 0.03 | 0.01 (0.11) | 0.02 (0.13) | −0.05 |

| Diabetes* | 0.31 (0.46) | 0.32 (0.47) | −0.03 | 0.31 (0.46) | 0.32 (0.47) | −0.02 |

| Diabetes with complications* | 0.09 (0.29) | 0.11 (0.31) | −0.04 | 0.09 (0.29) | 0.10 (0.30) | −0.01 |

| Moderate–severe liver disease* | 0.00 (0.05) | 0.00 (0.05) | −0.01 | 0.00 (0.05) | 0.00 (0.07) | −0.02 |

| Mild liver disease* | 0.01 (0.12) | 0.01 (0.12) | 0.00 | 0.02 (0.13) | 0.01 (0.12) | 0.01 |

| Hemiplegia or paraplegia* | 0.01 (0.11) | 0.01 (0.08) | 0.04 | 0.01 (0.08) | 0.01 (0.09) | −0.02 |

| Moderate–severe renal disease* | 0.08 (0.27) | 0.10 (0.30) | −0.06 | 0.08 (0.27) | 0.09 (0.28) | −0.02 |

| Peripheral vascular disease* | 0.23 (0.42) | 0.23 (0.42) | 0.01 | 0.23 (0.42) | 0.21 (0.41) | 0.04 |

| Rheumatologic disease* | 0.05 (0.22) | 0.07 (0.25) | −0.07 | 0.05 (0.22) | 0.05 (0.22) | 0.01 |

| Peptic ulcer disease* | 0.04 (0.20) | 0.04 (0.19) | 0.01 | 0.04 (0.19) | 0.04 (0.18) | 0.01 |

| AIDS* | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.03) | −0.04 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | |

| Smoking* | 0.48 (0.50) | 0.53 (0.50) | −0.08 | 0.48 (0.50) | 0.46 (0.50) | 0.04 |

| Hypertension* | 0.84 (0.37) | 0.84 (0.36) | −0.01 | 0.84 (0.37) | 0.85 (0.36) | −0.03 |

| Function‐related indicators† (in year before index cancer diagnosis) | ||||||

| Total number of functional impairments† | 0.74 (1.04) | 0.75 (1.01) | −0.01 | 0.69 (0.99) | 0.66 (0.88) | 0.04 |

| Any mobility limitation† | 0.04 (0.19) | 0.04 (0.18) | 0.01 | 0.04 (0.19) | 0.03 (0.18) | 0.03 |

| Supplemental oxygen† | 0.05 (0.21) | 0.04 (0.21) | 0.02 | 0.04 (0.21) | 0.04 (0.21) | 0.00 |

| Supplemental nutrition† | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.05) | −0.07 | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.00 (0.00) | |

| Catheter (internal or external)† | 0.02 (0.17) | 0.00 (0.06) | 0.13 | 0.01 (0.09) | 0.00 (0.07) | 0.02 |

| Hip or pelvic fracture† | 0.01 (0.09) | 0.01 (0.08) | 0.01 | 0.01 (0.08) | 0.00 (0.05) | 0.04 |

| Chronic skin ulcer† | 0.02 (0.13) | 0.02 (0.14) | −0.02 | 0.01 (0.12) | 0.02 (0.13) | −0.01 |

| Pneumonia† | 0.17 (0.37) | 0.17 (0.37) | 0.00 | 0.15 (0.35) | 0.14 (0.35) | 0.00 |

| Delirium, dementia, and Alzheimer's† | 0.03 (0.18) | 0.03 (0.18) | −0.00 | 0.03 (0.18) | 0.03 (0.17) | 0.02 |

| Bone marrow failure or agranulocytosis† | 0.01 (0.09) | 0.01 (0.10) | −0.03 | 0.01 (0.08) | 0.00 (0.07) | 0.02 |

| Depression† | 0.09 (0.29) | 0.10 (0.31) | −0.04 | 0.09 (0.29) | 0.09 (0.29) | 0.00 |

| Respiratory failure† | 0.03 (0.18) | 0.04 (0.19) | −0.02 | 0.03 (0.18) | 0.02 (0.16) | 0.04 |

| Sepsis† | 0.02 (0.13) | 0.01 (0.11) | 0.03 | 0.01 (0.11) | 0.02 (0.13) | −0.02 |

| Malnutrition and unintended weight loss† | 0.07 (0.25) | 0.06 (0.24) | 0.04 | 0.06 (0.24) | 0.05 (0.23) | 0.04 |

| Fall‐related injury† | 0.14 (0.34) | 0.17 (0.37) | −0.08 | 0.15 (0.35) | 0.14 (0.35) | 0.01 |

| Syncope† | 0.05 (0.22) | 0.05 (0.22) | −0.01 | 0.05 (0.21) | 0.04 (0.20) | 0.03 |

NCI indicates National Cancer Institute.

Comorbid conditions were constructed over the full period before diagnosis (minimum 1 year), generated during computation of the NCI comorbidity index. Definitions are described with the comorbidity index documentation. 16

Function‐related indicators 17 were constructed for the year before diagnosis.

During exposure assessment window.

Using codes in Table S2, event was considered to have occurred if a diagnosis code was present on 1 inpatient stay or 2 outpatient encounters separated by at least 30 days but not more than 365 days or by the presence of a procedure code in any position on any claim type.

Based on major adverse cardiac events variable definitions (Table S2).

The following covariates were included in the propensity score model: tumor size, nodal status, American Joint Committee on Cancer substage, low‐income subsidy, smoking, hypertension, comorbid conditions3, NCI comorbidity index, function‐related indicators, 4 frailty summary score, immunologic or hormonal therapies2 during the exposure assessment window, age at diagnosis, and cardiac conditions present at baseline. Additionally, pairs were required to have an exact match on laterality and year of diagnosis.

Oncologic therapies were categorized based on the Cancer Medications Enquiry Database available at https://seer.cancer.gov/oncologytoolbox/canmed/. The most common immunology therapies were monoclonal antibody targeted therapies (87.6%), most commonly bevacizumab (60.5% of all biologics) and denosumab (14.2%). Hormonal therapy consisted of corticosteroids (96.5%), somatostatin analogus (1.9%), hormone blockers (1.3%), and miscellaneous hormones not otherwise specified (0.3%). Immunologic and hormonal therapy definitions are provided in Table S2.

Other race includes American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian or Pacific Islander, unknown.

With a median follow‐up of 13 months (interquartile range: 3.47–32.21), 113 of 1364 (8.28%) matched patients had a severe cardiac event (70 of 682 patients treated with radiation [10.26%] and 43 of 682 patients treated without radiation [6.30%], P=0.008) with a median time to first event of 5.45 months. The 2‐year cumulative incidence of any severe cardiac event was 13.4% and 10.7% for patients treated with radiation and without radiation, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Cumulative Incidence of Severe Cardiac Events by Treatment Group in the Propensity Score‐Matched Cohort (n=1364)

| Overall (n=1364) | Chemoradiation (n=682) | Chemotherapy only (n=682) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of events in full follow‐up period (number within 2 years of follow‐up) | 2‐year cumulative incidence* (95% CI) | Number of events in full follow‐up period (number within 2 years of follow‐up) | 2‐year cumulative incidence* (95% CI) | Number of events in full follow‐up period (number within 2 years of follow‐up) | 2‐year cumulative incidence* (95% CI) | |

| Summary cardiac event indicators | ||||||

| Any MACE or CTCAE | 113 (92) | 12.1 (9.7–14.8) | 70 (57) | 13.4 (10.2–17.1) | 43 (35) | 10.7 (7.4–14.9) |

| Any MACE | 55 (40) | 5.1 (3.6–7.0) | 29 (22) | 5.2 (3.2–7.7) | 26 (18) | 5.2 (2.9–8.3) |

| Any CTCAE | 95 (76) | 10.1 (7.9–12.6) | 60 (48) | 11.4 (8.4–14.9) | 35 (28) | 8.8 (5.7–12.7) |

| Noncardiac death (competing event) | 263 (211) | 31.3 (27.5–35.2) | 194 (152) | 42.1 (36.5–47.6) | 69 (59) | 18.2 (13.8–23.15) |

| Individual MACE events | ||||||

| Acute MI | 23 (18) | 2.3 (1.4–3.7) | 12 (<11)† | 1.8 (0.8–3.4) | 11 (<11)† | 3 (1.4–5.7) |

| Hospitalized heart failure | 16 (11) | 1.6 (0.8–2.8) | <11 (<11)† | 2 (0.9–3.9) | <11 (<11)† | 1.1 (0.3–2.9) |

| Hospitalized ischemic heart disease (other than acute MI) | <11 (<11)† | 0.37 (0.1–0.9) | <11 (<11)† | 0.4 (0.1–1.4) | <11 (<11)† | 0.3 (0.1–1.1) |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention/coronary artery bypass graft | 13 (<11)† | 1 (0.4–2.1) | <11 (<11)† | 0.5 (0.1–1.3) | <11 (<11)† | 1.7 (0.5–4.3) |

| Cardiac death | 11 (<11)† | 0.9 (0.3–1.8) | <11 (<11)† | 0.9 (0.2–2.5) | <11 (<11)† | 0.8 (0.3–1.9) |

| Individual CTCAE events | ||||||

| Pericardial disease | <11 (<11)† | 0.9 (0.3–1.8) | <11 (<11)† | 0.9 (0.2–2.4) | <11 (<11)† | 0.8 (0.2–2.4) |

| Any conduction abnormality | 51 (45) | 6.2 (4.4–8.3) | 35 (31) | 7.5 (5.1–10.6) | 16 (14) | 4.6 (2.5–7.7) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 32 (31) | 4.3 (2.9–6.1) | <30 (<25)† | 6.1 (3.9–9.0) | <11 (<11)† | 2.2 (0.9–4.5) |

| Heart failure, cardiomyopathy, and myocarditis | 16 (<11)† | 1.6 (0.8–2.8) | <11 (<11)† | 2 (0.9–3.9) | <11 (<11)† | 1.1 (0.3–2.9) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 20 (14) | 1.8 (0.9–3.0) | <11 (<11)† | 1.1 (0.4–1.8) | >11 (<11)† | 2.7 (1.1–5.5) |

| Valve disorders or thoracic aortic disease | <11 (<11)† | 0.5 (0.1–1.6) | <11 (<11)† | 0.4 (0.1–1.4) | <11 (<11)† | 0.7 (0.1–3.5) |

CTCAE indicates clinical trial common adverse event; MACE, major adverse cardiac events; and MI, myocardial infarction.

Cumulative incidence percent is calculated based on the Fine–Gray Competing Risks Model's cumulative incidence function probability estimate. The 2‐year cumulative incidence reflects outcomes observed during each patient's available follow‐up, with a maximum of 2 years of follow‐up after diagnosis. Patients with more than 2 years of data available were censored at the 2‐year mark (ie, events or outcomes after 2 years from diagnosis were not evaluated).

Value suppressed or coarsened for confidentiality per the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results‐Medicare data use agreement, which is also consistent with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid cell size policy.

Of 1364 matched patients, 55 (4.03%) had 1 or more MACE (29 of 682 patients treated with radiation [4.26%], and 26 of 682 [3.81%] patients treated without radiation, P=0.68) with a median time to first MACE of 6.90 months. The 2‐year cumulative incidence of any MACE event was 5.2% for both those treated with radiation and without radiation (Table 2). Among individual MACE, a total of 11 had cardiac death, 23 developed an acute myocardial infarction, 16 were hospitalized with heart failure, <11 were hospitalized for ischemic heart disease other than acute myocardial infarction, and 13 had a percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass graft procedure (Table 2).

Of the 1364 matched patients, 95 (6.96%) had 1 or more approximated grade 3 CTCAE (60 of 682 [8.80%] treated with radiation and 35 of 682 [5.13%] without radiation, P=0.008) with a median time to first severe CTCAE of 6.28 months. The 2‐year cumulative incidence was 11.4% for patients treated with radiation treated and 8.8% for patients treated without radiation (Table 2). Among individual CTCAE, a total of 20 patients had an inpatient or urgent care encounter for ischemic heart disease, <11 for valvular disorders, 32 for atrial fibrillation, 51 with arrhythmia/conduction disorders including atrial fibrillation, 16 with heart failure/cardiomyopathy, and <11 for pericardial disease (Table 2).

Compared with chemotherapy alone, chemo‐radiation was significantly associated with an increase in the rate of severe cardiac events (CSHR, 1.62 [95% CI, 1.11–2.37]) as well as an increase in rate of noncardiac mortality (CSHR, 2.53 [95% CI, 1.93–3.33]) (Table 3). These results were comparable to the cumulative incidence analyses (SDHR, 1.41 [95% CI, 0.97–2.04] and SDHR, 2.52 [95% CI, 1.90–3.33], respectively) (Table 3, Figure 2). Over 73% (83 of 113) of people who experienced a severe cardiac outcome had a new onset event during the follow‐up period. Results were similar in sensitivity analyses that included only new onset outcomes (Table S3) and when restricted to stage IIIA only cases (Table S4).

Table 3.

Survival Analysis of Severe Cardiac Outcomes and Noncardiac Death by Chemoradiation vs Chemotherapy‐Only in the Propensity Score‐Matched Cohort (n=1364)

| Outcome | ||

|---|---|---|

| Model | Severe cardiac event | Noncardiac death (competing event) |

| Cause‐specific hazard ratio (95% CI),Wald P value | 1.62 (1.11–2.37), P=0.0128 | 2.53 (1.93–3.33), P<0.0001 |

| Subdistribution hazard ratio (95% CI), Wald P value | 1.41 (0.97–2.04), P=0.0692 | 2.52 (1.90–3.33), P<0.0001 |

Figure 2. Time to severe cardiac event and to competing event (noncardiac death) curves in propensity score‐matched cohort (n=1364).

A, Cause‐specific hazards of a severe cardiac event. B, Cumulative incidence (Fine–Gray) of severe cardiac events. C, Cause‐specific hazards of noncardiac death (the competing event). D, Cumulative incidence (Fine–Gray) of noncardiac death. Tabular insets provide the number of patients in the risk set at key time interval (in years) for cause‐specific hazards models.

There was some indication that the estimated effect of chemo‐radiation compared with chemotherapy alone among those with left‐sided laterality was greater than among those with right‐sided laterality (Table 4) The relative excess risk due to interaction was positive (0.16) with a 95% CI from −0.87 to 1.19 under the cause‐specific hazard model and 0.21 (−0.70 to 1.13) under the subdistribution hazard model. The laterality‐specific CSHRs were 1.64 (95% CI, 0.94–2.86) for left‐sided laterality and 1.59 (95% CI, 0.95–2.68) for right‐sided laterality. These results were comparable to the competing risk analyses by laterality where left‐side laterality SDHR was 1.46 (95% CI, 0.86–2.50) and right‐sided laterality SDHR was 1.38 (95% CI, 0.83–2.29). Compared with chemotherapy‐only and right‐sided laterality, the HRs for chemo‐radiation and left‐sided laterality were CSHR, 1.91 (95% CI, 1.12–3.25) and SDHR, 1.68 (95% CI, 0.99–2.85).

Table 4.

Modification of the Effect of Chemo‐radiation on Severe Cardiac Outcomes by Laterality

| Chemotherapy only hazard ratio (95% CI), Wald P value | Chemo‐radiation hazard ratio (95% CI), Wald P value | Chemo radiation vs chemotherapy only within strata of laterality hazard ratio (95% CI), Wald P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cause‐specific hazard model* | |||

| Right laterality (n=822) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.59 (0.95–2.68) P=0.0801 | 1.59 (0.95–2.68) P=0.0798 |

| Left laterality (n=542) | 1.15 (0.63–2.10) P=0.6430 | 1.91 (1.12–3.25) P=0.0175 | 1.64 (0.94–2.86) P=0.0814 |

| Subdistribution hazard model† | |||

| Right laterality (n=822) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.34 (0.80–2.27) P=0.2700 | 1.38 (0.83–2.29) P=0.2151 |

| Left laterality (n=542) | 1.13 (0.62–2.03) P=0.6936 | 1.68 (0.99–2.85) P=0.0532 | 1.46 (0.86–2.50) P=0.1618 |

RERI indicates relative excess risk due to interaction.

Cause‐specific hazard measure of effect modification: RERI, 0.16 [95% CI, −0.87 to 1.19] P=0.7567.

Subdistribution hazard measure of effect modification: RERI, 0.21, [95% CI, −0.70 to 1.13], P=0.6487.

DISCUSSION

In this population‐based study of Medicare beneficiaries with surgically treatable stage III NSCLC, we observed an increased risk of severe cardiac events associated with chemo‐radiation compared with chemotherapy only and noted a high risk within 2 years of follow‐up. This risk occurred in the context of an already high prevalence of baseline cardiac comorbidity. Examination of specific cardiac conditions suggested that areas of particular vulnerability may include conduction abnormalities, atrial arrhythmias, and heart failure, though sample size was too small to be conclusive.

The CSHRs for the 2 competing events (cardiac events and noncardiac death) were in the same direction. Compared with chemotherapy alone, chemo‐radiation was significantly associated with an increase in the rate of severe cardiac events as well as an increase in rate of noncardiac death. These results were comparable to the cumulative incidence analyses (ie, SDHRs). This knowledge helps inform how the impact of radiation on the cumulative incidence of cardiac events is interpreted. A higher rate of cardiac events accompanied by a higher competing rate of death implies that we will observe fewer cardiac events by the end of the study. Because both the cause‐specific and the cumulative incidence analyses are consistent with each other, this bolsters the inference that the effect of radiation on severe cardiac events when added to chemotherapy cannot be the result of an indirect protective effect on the competing event.

The increased rate of noncardiac death among recipients of chemo‐radiation suggests more extensive disease in this treatment group even though the matched groups were well balanced on stage and nodal status. Although no direct indication of cancer progression is available in SEER‐Medicare, respiratory neoplasms were coded as the underlying cause of death for 84% of all noncardiac deaths, with no statistically significant differences between patients who had chemo‐radiation versus chemotherapy only in respiratory neoplasm, nonrespiratory neoplasm, and non‐neoplasm cause of death (among people who had died and not died of cardiac death).

We explored whether the difference in rate of cardiac events between recipients of chemo‐radiation and chemotherapy only was greater among patients with left‐sided laterality. Although we did not expect laterality to have any direct effect on cardiac event risk or survival, 23 we did theorize that left‐sided laterality would correlate with a greater dose to the heart on average. The positive relative excess risk due to interaction indicated there was some evidence to support this. Because laterality is an imperfect proxy for heart dose, this likely underestimates the excess risk for some patients with left‐sided disease. Factors that may moderate mean heart dose include tumor location, heart volume, total radiotherapy dose, 3‐dimensional conformal radiation therapy plus intensity‐modulated radiation therapy compared with stereotactic body radiation therapy, and provider practices related to treatment planning for normal tissue dose constraints. 6 , 24

There have been previous SEER‐Medicare or SEER‐only cohort studies of cardiac outcomes among survivors of lung cancer. 11 , 12 , 24 , 25 In 1 study of 807 patients treated with chemotherapy who were propensity score‐matched to 807 who received chemotherapy plus radiation for small‐cell lung cancer diagnosed during 2000 to 2011, 11 an association between the addition of radiation therapy and a composite of cardiac events was found (HR, 1.20 [95% CI, 1.06–1.37]; P=0.005). The composite outcome included acute myocardial infarction or any acute heart disease, cardiomyopathy, dysrhythmia, heart failure, or pericarditis. A second SEER‐Medicare study 12 included patients of any stage diagnosed with NSCLC between 1991 and 2002 and followed through 2005 to identify ischemic heart disease, cardiomyopathy, conduction disorders, cardiac dysfunction, and heart failure. Compared with receiving neither chemotherapy nor radiation therapy, chemo‐radiation was associated with increased risks of conduction disorders, cardiac dysfunction, and heart failure, and this was further increased when radiation was delivered to the left lung. Chemo‐radiation was not directly compared with chemotherapy only in the study; however, for cardiac dysfunction the HR (HR, 2.36 [95% CI, 1.91–2.92]) exceeded that in the chemotherapy‐only group (HR, 1.58 [95% CI, 1.36–1.83]). One recent study of the unlinked SEER database examined the association between postoperative radiotherapy and cardiac‐related mortality among 7290 patients with stage IIIA‐N2 NSCLC from 1988 to 2016. Postoperative radiotherapy use was not associated with an increase in the hazard for cardiac‐related mortality (SDHR, 0.99 [95% CI, 0.78–1.24], P=0.91). 24 The study lacked data on comorbid conditions, smoking history, chemotherapy use, and radiation therapy dose. Liu et al 25 evaluated the effects of laterality in a radiation‐treated SEER‐Medicare cohort with stage I‐IIa NSCLC from 1994 to 2014 and found left‐side laterality to be associated with a higher rate of cardiac events when treated with 3‐dimensional conformal radiation therapy plus intensity‐modulated radiation therapy but not stereotactic body radiation therapy.

Recently, Atkins et al 9 recommended early recognition and treatment of cardiovascular events and efforts to avoid high cardiac radiotherapy dose based on findings from their 2‐institution case series medical record review of 748 patients treated with radiation from 1998 to 2014 with locally advanced (unresectable stage II or any stage III) NSCLC. Our estimate for 2‐year cumulative incidence of any MACE (5.2%) was similar to theirs (5.8%), and our estimate for CTCAE (11.4% among patients treated with chemo‐radiation) was lower than theirs (26.3%). This difference is likely because we required an acute care encounter for our CTCAE definition. They furthermore calculated mean whole‐heart dose for each patient and found this dose was associated with significantly increased risk of any MACE and any grade 3 or greater CTCAE. Of note, in their cohort only one‐third had been surgically treated, and the vast majority received both chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Chemo‐radiation is recommended for patients who are nonresectable whereas the benefit of chemo‐radiation is less certain for patients who are resectable. 26

Radiation to lung tumors will often result in unintentional radiation to the heart. This radiation can cause pericardial, ischemic, valvular, myocardial, and conduction system disease as well as autonomic changes, cardiomyopathy, arrhythmias, and heart failure. 27 , 28 Numerous acute and chronic pathologic mechanisms 29 have been identified leading to cellular damage and resultant cell loss, inflammation, and fibrosis that can affect any heart structure. Endothelial injury, inflammation and oxidative stress, and endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondrial dysfunction are all implicated pathways. 28 These effects vary in the timeline to clinical presentation and are dose related. Radiation has both acute and chronic effects on the pericardium, myocardium, and conduction system but may accelerate or exacerbate clinical symptoms of prevalent heart conditions. Although heart failure, arrhythmias, and valvular effects may require years to manifest clinically, radiation may also accelerate or exacerbate clinical symptoms of any type of preexisting heart condition. Therapeutic opportunities to prevent or treat radiation‐induced heart disease are being investigated, including antioxidants, anti‐inflammatory drugs, statins, cardioprotective drugs, renin‐angiotensin‐aldosterone system inhibitors, and a variety of novel pharmacologic therapies. 29

Our safety findings are relevant to clinical decision‐making for surgically treatable stage III NSCLC because clinical trials have not documented a clear benefit of chemo‐radiation over chemotherapy only for these patients. 26 We found that, before matching, patients treated with chemo‐radiation had larger tumor size and more extensive nodal status, suggesting that providers tend to select chemo‐radiation for patients with more extensive disease. Similarly, even after matching, chemo‐radiation was associated with a greater rate of noncardiac death, suggesting treatment sorting based on unmeasured lung cancer severity. Whether this reflects patient preferences for a tradeoff of potential lung cancer survival gain against severe cardiac events is not known.

Potential limitations of our study include limitations inherent with claims data and the observational design. Measurement error of treatment or cardiac outcomes is possible when using claims data. Our radiation and chemotherapy treatment measures were based on procedure codes that are high quality because they determine reimbursement. However, we could not assess the total radiation dose, fractions, or number of cycles delivered. The impact of radiation dosimetry on cardiac volume and individualized coronary substructures is also unavailable in claims data. Additionally, we included all chemotherapy regimens, and some chemotherapy types may have a lower risk of cardiac toxicity. 30 This imprecision would tend to underestimate the magnitude of associations. A limitation of retrospective analyses of claims data and a composite end point precludes inferences about how tradeoffs between cardiotoxicity and cancer efficacy were considered during clinical decision‐making. Practical considerations limited examination of distinct cardiac events; reliance on a composite outcome generalizes across types of cardiac events with different levels of clinical importance and expected frequency. 31 However, the composite cardiac outcomes used in this study are well‐established and accepted measures with particular merits in this context. We minimized measurement error for cardiac outcome definitions by employing algorithms with the best available positive predictive values and by including only severe events identified from hospital stays or other urgent care settings. A limitation of the observational design is that treatment was not randomized, and we cannot fully rule out the possibility that unmeasured cardiac risk factors rather than radiation itself may have explained the higher observed risks. However, the 2 treatment groups were already well balanced before matching on a large number of frailty and cardiac risk factors, and propensity score matching achieved excellent balance on all covariates, including smoking and other cancer treatments.

Generalizability of our findings is both a strength because of population‐based representation and a limitation because of excluded segments of the population. Our data were limited to patients over age 65 and may not generalize quantitatively to younger patients. Because of our desire to reflect more contemporary treatment practices, we included only patients diagnosed from 2007 and after. This affected available sample size and limited power for subgroup analyses and analyses of individual cardiac outcome types. Inferences can be made only for those who survived the 121‐day exposure assessment window. However, the typical time from radiation treatment to onset of cardiac side effects is typically months to years 9 , 32 so this is a minor limitation. This design feature is also a strength because it addresses immortal time bias. Finally, inferences can be made only for those who could be propensity score matched (see Table S5 for comparison with patients who could not be matched). However, this is also a strength in that it avoids generalizing a treatment effect to patients with a very low likelihood of receiving a particular treatment.

Strengths of this study include that it is population based and examines the comparative effects among surgically resectable treatment groups where safety may influence decision‐making because efficacy of adding radiation therapy is uncertain. 9 In addition, these results reflect more recent treatment years and use a propensity score‐matched study design to balance treatment groups on a detailed list of cardiac risk and function‐related factors. Finally, we conducted both cause‐specific survival analysis and cumulative incidence (ie, competing risk) analysis to understand the potential clinical relevance of any increased cardiac risk from radiation therapy given the competing risk of death from noncardiac causes (predominantly lung cancer).

CONCLUSIONS

The rate of cardiovascular disease among cancer survivors is higher than in the general population because of traditional cardiovascular risk factors, advancing age, and cardiotoxicity of cancer treatment. In this population‐based retrospective cohort study during a contemporary treatment era, patients who received adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus radiation for their surgically treatable stage III NSCLC had a 31% higher (8.7% versus 6.3%) rate of severe cardiac events compared with those who received chemotherapy only during a median of 13 months of follow‐up, with corresponding 2‐year cumulative incidences of any severe cardiac event of 13.4% and 10.7%, respectively. If chemo‐radiation confers survival benefits over chemotherapy alone, patients may feel that this is a risk worth taking. Opportunities to reduce that risk require investigation, including calculated dosimetry, stricter cardiac dose constraints, guidelines for cardiac risk assessment and monitoring, and repurposed or novel preventive and cardioprotective pharmacotherapies.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by the University of Iowa Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center Biostatistics and Population Research Cores (National Cancer Institute P30 CA086862; National Cancer Institute R50 CA243692). Dr Allen and Dr Spitz also received support from National Cancer Institute P01 CA217797.

Disclosures

The authors have no disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Tables S1–S5

Figure S1

Acknowledgments

This study used the linked SEER‐Medicare database. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the sole responsibility of the authors. The authors acknowledge the efforts of the National Cancer Institute; the Office of Research, Development and Information, CMS; Information Management Services, Inc.; and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program tumor registries in the creation of the SEER‐Medicare database.

This paper was sent to Kwok Leung Ong, Guest Editor, for review by expert referees, editorial decision, and final disposition.

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.122.027288

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 13.

REFERENCES

- 1. Armenian SH, Xu L, Ky B, Sun C, Farol LT, Pal SK, Douglas PS, Bhatia S, Chao C. Cardiovascular disease among survivors of adult‐onset cancer: a community‐based retrospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1122–1130. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.0409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abdel‐Rahman O. Causes of death in long‐term lung cancer survivors: a SEER database analysis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2017;33:1343–1348. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2017.1322052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Darby SC, McGale P, Taylor CW, Peto R. Long‐term mortality from heart disease and lung cancer after radiotherapy for early breast cancer: prospective cohort study of about 300 000 women in US SEER cancer registries. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:557–565. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70251-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Darby SC, Ewertz M, McGale P, Bennet AM, Blom‐Goldman U, Brønnum D, Correa C, Cutter D, Gagliardi G, Gigante B, et al. Risk of ischemic heart disease in women after radiotherapy for breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:987–998. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1209825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Boero IJ, Paravati AJ, Triplett DP, Hwang L, Matsuno RK, Gillespie EF, Yashar CM, Moiseenko V, Einck JP, Mell LK, et al. Modern radiation therapy and cardiac outcomes in breast cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;94:700–708. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Banfill K, Giuliani M, Aznar M, Franks K, McWilliam A, Schmitt M, Sun F, Vozenin MC, Faivre Finn C. IASLC advanced radiation technology committee. Cardiac toxicity of thoracic radiotherapy: existing evidence and future directions. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16:216–227. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang K, Eblan MJ, Deal AM, Lipner M, Zagar TM, Wang Y, Mavroidis P, Lee CB, Jensen BC, Rosenman JG, et al. Cardiac toxicity after radiotherapy for stage III non‐small‐cell lung cancer: pooled analysis of dose‐escalation trials delivering 70 to 90 Gy. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:1387–1394. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.70.0229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dess RT, Sun Y, Matuszak MM, Sun G, Soni PD, Bazzi L, Murthy VL, Hearn JWD, Kong FM, Kalemkerian GP, et al. Cardiac events after radiation therapy: combined analysis of prospective multicenter trials for locally advanced non‐small‐cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:1395–1402. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.6142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Atkins KM, Rawal B, Chaunzwa TL, Lamba N, Bitterman DS, Williams CL, Kozono DE, Baldini EH, Chen AB, Nguyen PL, et al. Cardiac radiation dose, cardiac disease, and mortality in patients with lung cancer. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:2976–2987. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. (PDQ®) Adult Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Non‐Small Cell Lung Cancer Treatment. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated June 15, 2021. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/types/lung/hp/non‐small‐cell‐lung‐treatment‐pdq. Accessed July 13, 2021.

- 11. Ferris MJ, Jiang R, Behera M, Ramalingam SS, Curran WJ, Higgins KA. Radiation therapy is associated with an increased incidence of cardiac events in patients with small cell lung cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2018;102:383–390. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.05.066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hardy D, Liu CC, Cormier JN, Xia R, Du XL. Cardiac toxicity in association with chemotherapy and radiation therapy in a large cohort of older patients with non‐small‐cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1825–1833. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Enewold L, Parsons H, Zhao L, Bott D, Rivera DR, Barrett MJ, Virnig BA, Warren JL. Updated overview of the SEER‐Medicare data: enhanced content and applications. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2020;2020:3–13. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgz029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hicks KA, Tcheng JE, Bozkurt B, Chaitman BR, Cutlip DE, Farb A, Fonarow GC, Jacobs JP, Jaff MR, Lichtman JH, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA key data elements and definitions for cardiovascular endpoint events in clinical trials: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force on clinical data standards (writing committee to develop cardiovascular endpoints data standards). Circulation. 2015;132:302–361. Erratum in: Circulation. 2015;132:e129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, Version 5.0, November 27, 2017. Available at: https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/CTCAE_v5_Quick_Reference_8.5x11.pdf (Accessed on March 28, 2022).

- 16. National Cancer Institute. Healthcare Delivery Research Program NCI comorbidity index overview, 2014 version. https://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/seermedicare/considerations/comorbidity.html. (Accessed on March 28, 2022).

- 17. Chrischilles E, Schneider K, Wilwert J, Lessman G, O'Donnell B, Gryzlak B, Wright K, Wallace R. Beyond comorbidity: expanding the definition and measurement of complexity among older adults using administrative claims data. Med Care. 2014;52:S75–S84. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Latouche A, Allignol A, Beyersmann J, Labopin M, Fine JP. A competing risks analysis should report results on all cause‐specific hazards and cumulative incidence functions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66:648–653. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stensrud MJ, Hernán MA. Why test for proportional hazards? JAMA. 2020;323:1401–1402. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li R, Chambless L. Test for additive interaction in proportional hazards models. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17:227–236. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lash TL, VanderWeele TJ, Haneuse S, Rothman KJ. Analysis of Interaction. Chapter 26 in: Modern Epidemiology, 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Knol MJ, VanderWeele TJ. Recommendations for presenting analyses of effect modification and interaction. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:514–520. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jia B, Zheng Q, Qi X, Zhao J, Wu M, An T, Wang Y, Zhuo M, Li J, Zhao X, et al. Survival comparison of right and left side non‐small cell lung cancer in stage I‐IIIA patients: a surveillance epidemiology and end results (SEER) analysis. Thorac Cancer. 2019;10:459–471. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.12959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sun X, Men Y, Wang J, Bao Y, Yang X, Zhao M, Sun S, Yuan M, Ma Z, Hui Z. Risk of cardiac‐related mortality in stage IIIA‐N2 non‐small cell lung cancer: analysis of the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) database. Thorac Cancer. 2021;12:1358–1365. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.13908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liu BY, Rehmani S, Kale MS, Marshall D, Rosenzweig KE, Kong CY, Wisnivesky J, Sigel K. Risk of cardiovascular toxicity according to tumor laterality among older patients with early stage non‐small cell lung cancer treated with radiation therapy. Chest. 2022;161:1666–1674. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.12.667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lei T, Li J, Zhong H, Zhang H, Jin Y, Wu J, Li L, Xu B, Song Q, Hu Q. Postoperative radiotherapy for patients with resectable stage III‐N2 non‐small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Front Oncol. 2021;11:680615. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.680615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yusuf SW, Venkatesulu BP, Mahadevan LS, Krishnan S. Radiation‐induced cardiovascular disease: a clinical perspective. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2017;4:66. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2017.00066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wang H, Wei J, Zheng Q, Meng L, Xin Y, Yin X, Jiang X. Radiation‐induced heart disease: a review of classification, mechanism and prevention. Int J Biol Sci. 2019;15:2128–2138. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.35460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sárközy M, Varga Z, Gáspár R, Szűcs G, Kovács MG, Kovács ZZA, Dux L, Kahán Z, Csont T. Pathomechanisms and therapeutic opportunities in radiation‐induced heart disease: from bench to bedside. Clin Res Cardiol. 2021;110:507–531. doi: 10.1007/s00392-021-01809-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Montisci A, Palmieri V, Liu JE, Vietri MT, Cirri S, Donatelli F, Napoli C. Severe cardiac toxicity induced by cancer therapies requiring intensive care unit admission. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:713694. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.713694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Armstrong P, Westerhout C. Composite end points in clinical research. Circulation. 2017;135:2299–2307. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.026229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Vojtíšek R. Cardiac toxicity of lung cancer radiotherapy. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2020;25:13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.rpor.2019.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tables S1–S5

Figure S1