Abstract

Background

Left atrial (LA) decompression on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) can reduce left ventricular distension, allowing myocardial rest and recovery, and protect from lung injury secondary to cardiogenic pulmonary edema. However, clinical benefits remain unknown. We sought to evaluate the association between LA decompression and in‐hospital adverse outcome (mortality, transplant on ECMO, or conversion to ventricular assist device) in patients who failed to wean from cardiopulmonary bypass using a propensity score to adjust for baseline differences.

Methods and Results

Children (aged <18 years) with biventricular physiology supported with ECMO for failure to wean from cardiopulmonary bypass after cardiac surgery from 2000 through 2016, reported to the ELSO (Extracorporeal Life Support Organization) Registry, were included. Inverse probability of treatment weighted logistic regression was used to test the association between LA decompression and in‐hospital adverse outcomes. Of the 2915 patients supported with venoarterial ECMO for failure to wean from cardiopulmonary bypass, 1508 had biventricular physiology and 279 (18%) underwent LA decompression (LA+). Genetic and congenital abnormalities (P=0.001) and pulmonary hypertension (P=0.010) were less frequent and baseline arrhythmias (P=0.022) were more frequent in LA+ patients. LA+ patients had longer pre‐ECMO mechanical ventilation and CBP time (P<0.001), and used aortic cross‐clamp (P=0.001) more frequently. Covariates were well balanced between the propensity‐weighted cohorts. In‐hospital adverse outcomes occurred in 47% of LA+ patients and 51% of the others. Weighted multivariate logistic regression showed LA decompression to be protective for in‐hospital adverse outcomes (adjusted odds ratio, 0.775 [95% CI, 0.644–0.932]).

Conclusions

LA decompression independently decreased the risk of in‐hospital adverse outcome in pediatric venoarterial ECMO patients who failed to wean from cardiopulmonary bypass, suggesting that these patients may benefit from LA decompression.

Keywords: congenital heart disease, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, failure to wean from cardiopulmonary bypass, left atrial decompression

Subject Categories: Congenital Heart Disease, Heart Failure, Cardiovascular Surgery, Mortality/Survival

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CPB

cardiopulmonary bypass

- ELSO

Extracorporeal Life Support Organization

Clinical Perspective

What Is New?

We evaluated benefit of left atrial decompression in terms of outcomes (in‐hospital mortality, transplant on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation [ECMO], or conversion to ventricular assist device), in a large multicenter cohort of children with congenital heart disease and biventricular physiology supported with venoarterial ECMO for failure to wean from cardiopulmonary bypass, using propensity score analysis to adjust for baseline differences.

We found left atrial decompression to be an independent protective factor against in‐hospital adverse outcomes.

Other factors including longer ECMO duration, higher ECMO pump flow, cardiac surgery on ECMO, and ECMO complications were also found to independently increase the risk of adverse outcomes, whereas the use of systemic vasodilators on ECMO independently reduced the risk.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Our results suggest that left atrial decompression may have clinical benefits in children with biventricular physiology who are supported with venoarterial ECMO after failing to wean from cardiopulmonary bypass after congenital cardiac surgery.

These findings add significant evidence to support consideration of left atrial decompression in children supported with ECMO and may help design future trials to secure higher level of evidence.

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) provides mechanical circulatory support for resuscitation in children who experienced severe acute cardiac failure. 1 In the setting of a failing heart and increased left ventricular (LV) afterload secondary to ECMO, the LV end‐diastolic volume and pressure can increase, reducing transmural myocardial perfusion and impairing myocardial function and recovery. Left atrial (LA) decompression, either transcatheter or surgical, has been described as a successful strategy for decreasing the left heart pressure in adults and pediatric patients by reducing the LV distension and decreasing the LV wall stress, facilitating myocardial rest and recovery. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 Furthermore, LA decompression may protect from lung injury secondary to cardiogenic pulmonary edema or pulmonary hemorrhage when severe LA hypertension is present. 2 , 4 , 6 , 8

Different techniques to decompress the left heart in patients supported with ECMO have been described. In patients with central cannulation, addition of an LA cannula through one of the pulmonary veins (or less frequently addition of a pulmonary artery cannula) is the more common approach. 9 , 10 , 11 In patients with peripheral ECMO or when left atrial cannulation is not anatomically possible, transcatheter or surgical atrial septostomy are the preferred options. 5 , 6 , 9 , 10 Finally, in appropriately sized patients, a synergic combination of ECMO with a temporary, percutaneously implanted intracorporeal left ventricular assist device (VAD; ie, Impella) has been recently described as a valuable alternative. 9 , 10 Because the LA decompression is not universally performed in children on ECMO and procedure can be associated with adverse events, the benefits of LA decompression need to be defined. 5 , 9 , 10 With the present study, we sought to define the benefit of LA decompression in terms of in‐hospital outcome (mortality, transplant on ECMO, or conversion to VAD) in a cohort of pediatric patients supported on venoarterial ECMO for failure to wean from cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) after cardiac surgery.

In a previous ELSO (Extracorporeal Life Support Organization) Registry analysis, we evaluated a large cohort of children with congenital and acquired heart disease who underwent open heart surgery and failed to wean from CPB, describing their in‐hospital mortality and associated risk factors. 12 In this recently published study, we found that, among ECMO‐related factors, LA cannulation was protective against in‐hospital mortality. Although LA cannulation was not retained in the final model when all the other investigated factors were added, we believe this may have been influenced by the significant number of patients with univentricular physiology included in the study, who did not need an LA decompression because of the underlying surgical anatomy. Therefore, we performed a subgroup analysis of the previously described cohort, only including patients with biventricular physiology, and investigated the specific association between LA decompression and in‐hospital outcome. A propensity score weighting approach was used to address the existence of selection biases before the intervention.

Methods

Study Population

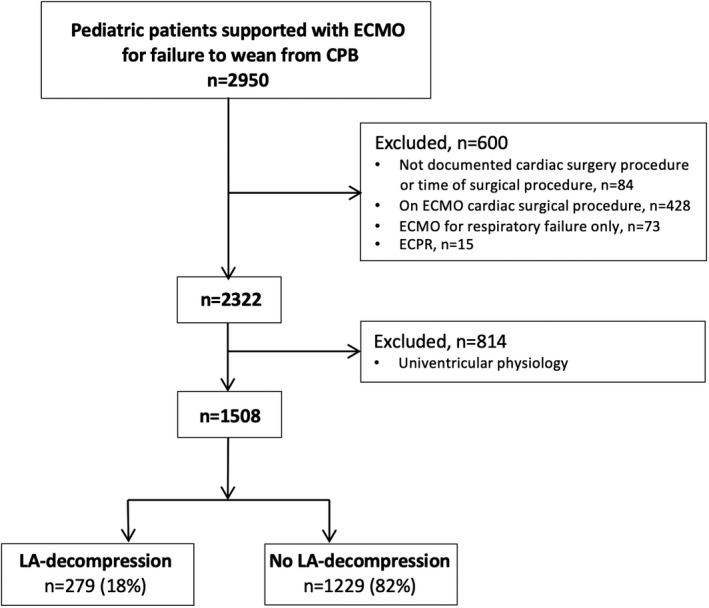

We included children (aged <18 years) with biventricular physiology who underwent an open heart surgical procedure and required ECMO for failure to wean from CPB, reported to the ELSO Registry during the period 2000 to 2016. Patients were excluded if were already on ECMO at the time of surgery, had no documented cardiac surgical procedure or time of surgical procedure, required ECMO for isolated respiratory failure or to support cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or had univentricular physiology (Figure).

Figure 1. Flowchart of patient selection.

CPB indicates cardiopulmonary bypass; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; ECPR, ECMO–cardiopulmonary resuscitation; and LA, left atrial.

Data Source, Collection, and Categorization

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Data were extracted from the ELSO Registry. Member centers report data on voluntary basis, after approval by their local Institutional Review Board. A data user agreement between ELSO Registry and member centers allows release of limited deidentified data sets for research purposes, waiving the need for regulatory approval. The present study qualified for human subject research exemption by Boston Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board (IRB‐P00035751). Data extracted included baseline demographics and clinical characteristics, cardiac surgical procedure details, pre‐ECMO support variables, ECMO support details, and ECMO complications. Cardiac surgical procedures were categorized on the basis of complexity, using the risk‐adjusted congenital heart surgery 1 method. 13

Predictors and Outcome Measures

Our primary predictor was use of LA decompression (ie, LA cannulation, transcatheter atrial septostomy, or surgical atrial septostomy on ECMO). Of note, timing of LA decompression is not included in the ELSO Registry. Our primary outcome measure was any in‐hospital adverse outcome, defined as any one of the following: in‐hospital mortality, transplant, or conversion to VAD while on ECMO. Secondary outcome measures were ECMO duration and successful weaning off ECMO.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive data are reported as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and median and interquartile range (25th–75th percentile) for continuous variables because of distribution characteristics. Given the observational nonrandomized nature of this study, significant baseline differences between patients who underwent LA decompression (LA+) and patients who did not (LA–) can influence the association of LA decompression and in‐hospital outcome. To assess the existence of these selection biases, demographic and clinical pre‐ECMO details were compared between LA+ and LA– patients. The Pearson χ2 test was used to compare categorical data before weighting; the Fisher exact test was used when the expected count in >20% of cells was <5. The Mann‐Whitney U test was used to compare continuous data. Because significant differences between LA+ and LA– patients were identified, a propensity‐weighted approach was chosen to balance these differences. In particular, an inverse probability of treatment weighting, based on a propensity score, was used to weight demographic and clinical baseline differences between LA+ and LA– patients. 14 , 15 To compute the inverse probability of treatment weights, we estimated each patient’s propensity to undergo LA decompression using a logistic regression model with the LA decompression as dependent variable. Predictor variables were selected on the basis of their univariate associations with the treatment (P<0.1) and their a priori probability of confounding the relationship between LA decompression and mortality. The following variables were selected as candidates for inclusion: age, race (White), genetic syndrome, other congenital anomalies, prematurity, baseline cardiac conditions as arrhythmias, pulmonary hypertension, and cardiomyopathy, baseline respiratory, neurologic, renal, gastroenterological, and infectious endocrine‐metabolic diseases, coagulation defects or hemorrhages, preoperative cardiac arrest, risk‐adjusted congenital heart surgery 1 score, CBP time, use of aortic cross‐clamp, use of deep hypothermic circulatory arrest, and pre‐ECMO vasoactive support. Candidate variables for this model were tested for collinearity; age and weight were found to be collinear; thus, only age was used for modeling. The predicted probability from the model was saved as “propensity score”; the “inverse probability of treatment propensity score” was then computed, assigning LA+ patients a weight of 1/propensity score and LA– patients a weight of 1/(1−propensity score). 15 The performance of the score in balancing the baseline differences between the 2 groups was confirmed using weighted logistic regression (with LA decompression as dependent variable; Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic, Baseline Clinical, and Pre‐ECMO Characteristics, According to LA Decompression, Before and After Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting

| Variable |

Cohort before inverse probability of treatment weighting |

Cohort after inverse probability of treatment weighting |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

LA decompression (n=279) |

No LA decompression (n=1229) |

P value* |

LA decompression (n=245) |

No LA decompression (n=1019) |

P value † | |

| Age, median (IQR), d | 64 (10–214) | 46 (8–193) | 0.179 | 64 (9–220) | 46 (8–189) | 0.648 |

| Weight, median (IQR), kga | 4.0 (3.3–6.6) | 3.8 (3.1–6.3) | 0.076 | 4.0 (3.3–6.7) | 3.8 (3.1–6.2) | 0.919 |

| Race, White, n (%)b | 158 (58) | 688 (58) | 0.888 | 142 (58) | 594 (58) | 0.541 |

| Comorbid conditions, n (%) | ||||||

| Genetic syndrome or other congenital anomalies | 32 (11) | 244 (20) | 0.001 | 29 (12) | 202 (20) | 0.304 |

| Prematurity ‡ | 26 (9) | 100 (8) | 0.519 | 22 (9) | 86 (8) | 0.850 |

| Cardiac‐associated disease | ||||||

| Arrhythmia | 55 (20) | 175 (14) | 0.022 | 47 (19) | 151 (15) | 0.774 |

| Pulmonary hypertension | 6 (2) | 73 (6) | 0.010 | 5 (1) | 63 (6) | 0.080 |

| Cardiomyopathy | 8 (3) | 35 (3) | 0.986 | 5 (2) | 28 (3) | 0.416 |

| Respiratory disease | 52 (19) | 227 (19) | 0.948 | 47 (19) | 194 (19) | 0.671 |

| Neurologic disease | 34 (12) | 113 (9) | 0.128 | 28 (11) | 100 (9) | 0.468 |

| Renal disease | 33 (12) | 128 (10) | 0.490 | 30 (12) | 113 (11) | 0.868 |

| Gastrointestinal disease | 15 (5) | 76 (6) | 0.609 | 13 (5) | 67 (7) | 0.315 |

| Infectious disease | 25 (9) | 83 (7) | 0.197 | 20 (8) | 78 (8) | 0.915 |

| Metabolic, endocrine, or electrolyte abnormalities | 11 (4) | 59 (5) | 0.539 | 8 (3) | 48 (5) | 0.710 |

| Coagulation defects | 7 (2) | 21 (2) | 0.371 | 6 (2) | 20 (2) | 0.670 |

| Hemorrhage | 12 (4) | 67 (5) | 0.436 | 10 (4) | 61 (6) | 0.060 |

| Other comorbidities | 25 (9) | 113 (9) | 0.903 | 22 (9) | 103 (10) | 0.229 |

| Preoperative cardiac arrest, n (%) § | 36 (13) | 123 (10) | 0.155 | 32 (13) | 98 (10) | 0.508 |

| Main cardiac surgery RACHS‐1 score, n (%) | ||||||

| 1–3 | 188 (67) | 748 (61) | 166 (68) | 614 (60) | ||

| 4–6 | 79 (28) | 435 (35) | 0.079 | 69 (28) | 368 (36) | 0.738 |

| Not assigned | 12 (4) | 46 (4) | 10 (4) | 37 (4) | ||

| Surgery details | ||||||

| CPB time, median (IQR), minc | 288 (207–386) | 250 (172–357) | <0.001 | 295 (209–384) | 251 (173–359) | 0.782 |

| ACC, n (%) | 261 (93) | 1038 (84) | 0.001 | 243 (99) | 965 (95) | 0.561 |

| DHCA, n (%) | 89 (32) | 429 (35) | 0.340 | 84 (34) | 401 (39) | 0.385 |

| Pre‐ECMO support, n (%) | ||||||

| Inotropic/vasopressor drugs | 171 (61) | 751 (61) | 0.955 | 158 (64) | 645 (63) | 0.495 |

| Vasodilator drugs | 52 (19) | 230 (19) | 0.976 | 47 (19) | 201 (20) | 0.681 |

| Inhaled NO | 35 (12) | 204 (17) | 0.094 | 31 (13) | 170 (17) | 0.283 |

| Pre‐ECMO neuromuscular blockers, n (%) | 149 (53) | 583 (47) | 0.072 | 134 (55) | 512 (50) | 0.196 |

| Pre‐ECMO mechanical ventilation >24 h, n (%) | 117 (43) | 419 (35) | 0.018 | 103 (42) | 351 (35) | 0.649 |

| Preoperative bicarbonate infusion, n (%) | 49 (18) | 196 (16) | 0.509 | 47 (19) | 170 (17) | 0.645 |

Missing data before weighting, n (LA+, LA–): a10 (2, 8); b42 (7, 35); c159 (18, 141). ACC indicates aortic cross‐clamp; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; DHCA deep hypothermic cardiac arrest; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; IQR, interquartile range; LA, left atrial; and RACHS‐1, risk‐adjusted congenital heart surgery score 1.

P values are calculated by χ2 test and Mann‐Whitney U test.

P values are calculated by weighted logistic regression.

Prematurity is defined as gestational age ≤36 weeks.

Within 24 hours before ECMO.

Bold values indicate statistical significant.

Once a balance was confirmed, LA decompression was tested as a predictor of mortality in 2 weighted logistic regression models. The first model tested the unadjusted relationship with the outcome; the second model was then adjusted for other potential predictors of mortality. Candidate variables for inclusion in the adjusted model were selected from the univariate weighted analysis comparing survivors and nonsurvivors and were tested for collinearity. In case of collinear variables, only the variable with the most significant P value in the univariate analysis was included. All variables with a univariate P value <0.1 were selected for inclusion in the multivariable model. A backward conditional strategy was used to reach the final model. All statistical analyses were performed using R statistics (version 3.6.2.; R Core Team, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Statistical significance was set at a 2‐sided P<0.05.

Results

Study Population

Of the 2915 patients supported with ECMO for failure to wean from CPB during the study period, 1508 met the inclusion criteria (Figure). Of these, 279 (18%) patients underwent LA decompression (LA cannulation, n=269; transcatheter, n=4; or surgical atrial septostomy, n=9). A total of 1264 patients (245 LA+ and 1019 LA–) had available data to compute the propensity score and were therefore included in the weighted logistic regression analysis (Table 1).

Table 1 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the population, as well as differences between LA+ and LA– patients before and after the propensity weighting. LA+ patients were less likely to have a diagnosis of genetic syndrome or congenital anomalies (P=0.001) or a diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension (P=0.010), and more likely to have baseline arrhythmias (P=0.022). There were no other significant differences in terms of comorbidities at baseline. In terms of pre‐ECMO support, LA+ patients had longer mechanical ventilation pre‐ECMO (P=0.018). As for surgical characteristics, LA+ patients required longer CBP time (P<0.001) and more commonly underwent aortic cross‐clamp (P=0.001). Once the newly computed propensity score was used to weight the comparison analysis (Table 1, on the right), no significant differences persisted between the groups.

ECMO Details, Hospital Stay Characteristics, and Outcomes of LA+ Patients Compared With LA– Patients

Patients who underwent LA decompression included a higher proportion of patients with cardiac arrhythmias (P=0.046), patients with myocardial stun (P<0.001), those supported with systemic vasodilators (P<0.001), and patients with hemofiltration (P<0.001). LA+ patients more frequently underwent further cardiac surgery on ECMO (P<0.001) or post‐ECMO (P=0.012). They had lower fraction of inspired oxygen requirements at 24 hours of ECMO (P<0.001), lower frequency of hypoglycemia (P=0.003), and lower need for inotropic support on ECMO (P=0.032). ECMO circuit complications and cannulation bleeding were similar between the 2 groups (Table S1).

Of the 1264 patients included, 638 (50%) had at least one in‐hospital adverse outcome (transplant on ECMO, n=5 [0.4%]; conversion to VAD, n=10 [1%]; and mortality, n=633 [50%]). The frequency of adverse outcomes did not significantly differ between the 2 cohorts by unadjusted weighted analysis (47% in LA+ patients versus 51% in LA– patients; P=0.078; odds ratio [OR], 0.868 [95% CI, 0.741–1.016]; Table 2). However, when the weighted logistic regression was adjusted for other variables (Table 2), LA decompression was found to be an independent protective factor against in‐hospital adverse outcome (adjusted OR, 0.775 [95% CI, 0.644–0.932]; P=0.007; Table 2).

Table 2.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Weighted Logistic Regression, Testing LA Decompression as an Independent Predictor of In‐Hospital Adverse Outcome

| Variables | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted logistic regression | |||

| LA decompression | 0.868 | 0.741–1.016 | 0.078 |

| Adjusted logistic regression model | |||

| LA decompression | 0.775 | 0.644–0.932 | 0.007 |

| ECMO pump flow at 4 h of ECMO (mL/kg per min) | |||

| ≤97 | 1.0 | Reference | … |

| >97 and ≤115 | 1.284 | 1.000–1.650 | 0.050 |

| >115 and ≤140 | 1.441 | 1.118–1.857 | 0.004 |

| >141 | 1.862 | 1.408–2.463 | <0.001 |

| ECMO support duration (h) | 1.004 | 1.003–1.005 | <0.001 |

| Cardiac surgery on ECMO | 1.743 | 1.327–2.290 | <0.001 |

| ECMO circuit complications | 1.451 | 1.192–1.767 | <0.001 |

| CNS hemorrhage or infarction on ECMO | 1.741 | 1.333–2.274 | <0.001 |

| Cardiac arrhythmia requiring treatment on ECMO | 2.399 | 1.887–3.049 | <0.001 |

| CPR on ECMO | 2.421 | 1.139–5.144 | 0.021 |

| Use of systemic vasodilators on ECMO | 0.625 | 0.489–0.797 | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary hemorrhage on ECMO | 2.915 | 2.111–4.024 | <0.001 |

| Renal failure on ECMO | 1.989 | 1.465–2.700 | <0.001 |

| Use of hemofiltration on ECMO | 1.260 | 1.029–1.542 | 0.025 |

| Arterial pH <7.20 on ECMO | 3.047 | 1.862–4.986 | <0.001 |

| Blood glucose <40 mg/dL on ECMO | 2.678 | 1.217–5.898 | 0.014 |

Unadjusted model: N=1264; Hosmer and Lemeshow test P=1.000; area under the curve=0.522. Adjusted model: N=1205; Hosmer and Lemeshow test P=0.863; area under the curve=0.743. Candidate variables were as follows: LA decompression, ECMO pump flow at 4 hours of ECMO, ECMO support duration (hours), cardiac surgery on ECMO, multiple cardiac surgery on ECMO, invasive procedure on ECMO other than cardiac surgeries (by Current Procedural Terminology procedure codes), ECMO circuit complications (mechanical complications requiring intervention, such as oxygenator failure, pump failure, raceway or other tubing rupture, circuit change, cannula problems, heat exchanger malfunction, clots, and air emboli), seizures, CNS hemorrhages or infarction, cardiac arrhythmia requiring treatment (medication infusion, overdrive pacing, cardioversion, or defibrillation), CPR on ECMO, use of inotropic or vasopressor drugs on ECMO (dobutamine, dopamine, epinephrine, milrinone, norepinephrine, or vasopressin), use of systemic vasodilators (nicardipine, nitroglycerin, nitroprusside, or milrinone), pneumothorax requiring treatment, pulmonary hemorrhage, cannulation or surgical site bleeding, hemolysis (plasma‐free hemoglobin >50 mg/dL), disseminated intravascular coagulation, infectious complications, renal failure, use of hemofiltration, arterial pH >7.60, arterial pH<7.20, blood glucose <40 mg/dL, and hyperbilirubinemia (direct bilirubin >2.0 mg/dL or total bilirubin >15.0 mg/dL). Detailed variable definitions are available at https://www.elso.org/Registry/DataDefinitions,Forms,Instructions.aspx. CNS indicates central nervous system; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; and LA, left atrial.

P values are calculated by weighted logistic regression.

Bold values indicate statistical significant.

Other Predictors for In‐Hospital Mortality

Weighted univariate analysis of variables potentially associated with in‐hospital mortality is shown in Table S2. Patients who had an adverse outcome had higher ECMO flow at 4 hours (60% of them >100 mL/kg per minute) and at 24 hours (both P<0.001), frequently required additional cardiac surgery on ECMO (P<0.001), had longer ECMO duration (P<0.001), and had more ECMO complications (Table S2). The weighted multivariate analysis (Table 2) showed longer ECMO duration, higher ECMO pump flow, cardiac surgery on ECMO, and ECMO complications (central nervous system hemorrhage or infarction, cardiac arrhythmia requiring treatment, cardiopulmonary resuscitation on ECMO, pulmonary hemorrhages, as well as renal failure, use of hemofiltration, hypoglycemia, and acidosis) independently increased the risk of adverse outcome, whereas the use of systemic vasodilators on ECMO reduced the risk for adverse outcome.

LA Decompression and Secondary Outcomes

ECMO duration did not significantly differ between LA+ and LA– patients (107 [interquartile range, 66–181] hours versus 107 [interquartile range, 64–168] hours; weighted P=0.602). Rate of ECMO weaning was similar in the 2 groups (69% in LA+ patients versus 70% in LA– patients; weighted P=0.437).

Discussion

In this large multicenter cohort of pediatric patients with biventricular physiology supported with venoarterial ECMO for failure to wean from CBP, 18% of patients underwent LA decompression during ECMO. Using a propensity score–weighted analysis, adjusting for baseline differences between patients who did or did not undergo LA decompression, we show that LA decompression was independently associated with decreased in‐hospital adverse outcome (mortality, transplantation, or conversion to VAD).

Although venoarterial ECMO effectively supports organ perfusion in the setting of a failing heart, it also increases the LV afterload and LV end‐diastolic pressure, causing LV dilation. Several studies have shown that LV distention reduces transcoronary perfusion gradient impairing myocardial perfusion, resulting in myocardial injury. 11 , 16 , 17 The severity of LV distension has been demonstrated to be inversely related to the likelihood of myocardial recovery and event‐free survival (death or transition to VAD). 18 The absence of ejection in the setting of a closed aortic valve may also cause stasis of blood in the LV with higher risk of thrombus formation. 19 Finally, LA hypertension may cause significant pulmonary edema, which can negatively affect the right ventricular function and the respiratory gas exchange. In this setting, LA decompression, either surgical or transcatheter, has been proposed as a means to mitigate these adverse events in both adults and pediatric patients. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 7 , 9 , 17

Although LA decompression has become common practice, data have conflicted on the best modality of decompression, best timing, as well as the overall utility of this intervention. Although some studies support its benefits, 5 , 8 others showed no differences in outcomes between patients who did or did not undergo LA decompression. 20 In particular, Baruteau et al retrospectively reviewed data of 64 patients (32 adults and 32 children) among 4 institutions who underwent a transcatheter balloon atrioseptostomy for LA decompression on venoarterial ECMO, reporting an improvement of day 1 chest X‐ray in 77% of patients, improvement of clinical status in all but one patient, and improvement of pulmonary hemorrhages in all patients who experienced this complication (n=14). 5 Kotani et al reported a series of 23 pediatric patients who underwent LA decompression within 12 hours of ECMO cannulation and described a 70% weaning rate. 8 In a recent multicenter study of 16 US pediatric centers, including a total of 137 patients, early LA decompression (within 18 hours since cannulation) was found to be associated with reduced ECMO duration but did not modify the in‐hospital and overall survival. 7 Conflicting evidence exists also for the adult population 9 , 21 ; however, a recent meta‐analysis of 17 observational studies on adult patients supported on venoarterial ECMO for cardiogenic shock found that LA+ patients had a lower mortality rate compared with others. 6 , 7 , 22

Several factors may have led to inconsistent conclusions on the benefit of LA decompression. First, populations may have been too heterogeneous, and data on adults may not be comparable to those on pediatric populations. Although in adults some degree of LV distension is usually well tolerated, threshold for LV decompression in children should be lower as the infantile myocardium is extremely vulnerable to distension 9 , 23 ; and, hemodynamics may be more labile in the setting of complex congenital heart diseases. Moreover, compared with children, alternative and more efficient strategies to decompress the LV, such as the combination of a temporary left VAD (ie, Impella) and ECMO, are available in the adult population. 9 In addition, timing of LA decompression may be critical in defining patients’ outcome, given the decreased ability of the myocardium to recover once ischemia has occurred; thus, variability in time to LA decompression between centers may have resulted in inconsistent conclusions on the benefits of LA decompression. 7 Finally, but not less importantly, selection biases may play a crucial role in influencing and confounding outcome‐related analysis.

Our propensity‐based approach allowed us to detect and adjust for the most important treatment‐related selection biases. In fact, the initial comparison analysis between LA+ and LA– patients demonstrated that significant differences exist between the 2 groups: LA+ patients had less frequently a genetic syndrome or congenital anomalies, had more frequently baseline arrhythmias, had longer CBP time, had more frequently required an aortic cross‐clamp, and had longer preoperative mechanical ventilation. The propensity score was able to adjust for these biases, allowing us to investigate the effect of LA decompression on in‐hospital adverse outcomes on weighted cohorts. At the multivariate weighted analysis, LA decompression was found to be a protective factor against in‐hospital adverse outcome (mortality, transplant on ECMO, or conversion to VAD), suggesting that clinical benefits may exist in pediatric patients with biventricular physiology who failed to wean off CPB.

Certainly, this is a selected population of patients who required ECMO support because of severe LV impairment. Indeed, 60% of the patients were supported with >100 mL/kg per minute of ECMO flow at 4 hours. In some circumstances, it is possible that high ECMO flows may have contributed to increasing the workload of the LV. 24 , 25 , 26 In fact, although venoarterial ECMO can reduce central venous pressure and improve end‐organ perfusion, it can also cause a significant increase in LV afterload because of retrograde perfusion of the aorta, which may inhibit aortic valve opening and suppress LV ejection. 25 , 26 Thus, as ECMO flow increases, the primary hemodynamic effect is an increase in the LV afterload. 25 In addition, as ECMO flow increases, the venous return to the LV (residual flow through the pulmonary circulation, venous return from the bronchial circulation, and Thebesian flow) increases, the LV end‐diastolic pressure increases, and the LV end‐diastolic pressure/stroke volume relationship on the Frank‐Starling curve shifts to the right, increasing the work and oxygen consumption of the LV in the effort to eject. 25 , 26 Consistently, the variable “ECMO flows at 4 hours” was retained in the final logistic regression model as an independent risk factor for adverse outcomes, with higher ORs at increased flows, whereas LA decompression and use of systemic vasodilators were identified as protective. Other risk factors for adverse outcomes identified by our model may all be related to either insufficient decompression of the LV or insufficient ECMO flow: pulmonary hemorrhage (likely related to LA hypertension), cardiac arrhythmias (possibly related to high filling pressures), renal failure (likely secondary to either right ventricular failure or insufficient ECMO flow), hypoglycemia (likely related to liver failure secondary to right ventricular failure), and acidosis (likely secondary to insufficient ECMO flows). These risk factors were previously reported for other ECMO cohorts. 12 , 27 , 28 , 29

Many limitations of this study need to be acknowledged. First, there are no data about the timing of LA decompression and the specific decompression technique used, which would have been an important factor that may have influenced our primary outcome. Data on LV function, ejection across the aortic valve, presence of aortic regurgitation, and pre‐ECMO existence of atrial communication, such as atrial septal defects, were not available for further analysis. As well, given the retrospective nature of this multicenter registry study, missing data may have influenced our analyses. In addition, given the high numbers of centers included in this study, it was not possible to take into consideration a center effect as these data were not available for analysis. Last, the results may not be generalizable to all patients supported on ECMO. We believe that patients with severe biventricular dysfunction and no LV ejection may benefit from LA decompression. However, clinicians should weigh the risks and benefits before decompressing the left heart during ECMO. Future studies that will include these data may be able to identify the category of patients who may benefit the most from this intervention. Despite these limitations, this represents, at the best of our knowledge, the largest reported cohort of pediatric patients on venoarterial ECMO who underwent LA decompression, and the first propensity score–adjusted analysis to access its association with in‐hospital adverse outcome.

In conclusion, in this multicenter cohort of pediatric patients supported with venoarterial ECMO for failure to wean from CPB, we have shown that LA decompression independently decreased the risk of in‐hospital adverse outcomes, suggesting these patients may benefit from LA decompression. Although only a randomized controlled trial could confirm this evidence, we believe our results add more evidence in supporting LA decompression in this population and may help design future higher‐evidence trials.

Source of Funding

None.

Disclosures

None.

Supporting information

Tables S1–S2

Supplemental Material for this article is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.121.023963

See Editorial by Baran and Brozzi.

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 8.

References

- 1. Barbaro RP, Paden ML, Guner YS, Raman L, Ryerson LM, Alexander P, Nasr VG, Bembea MM, Rycus PT, Thiagarajan RR. Pediatric extracorporeal life support organization registry international report 2016. ASAIO J. 2017;63:456–463. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Seib PM, Faulkner SC, Erickson CC, Van Devanter SH, Harrell JE, Fasules JW, Frazier EA, Morrow WR. Blade and balloon atrial septostomy for left heart decompression in patients with severe ventricular dysfunction on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 1999;46:179–186. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Johnston TA, Jaggers J, McGovern JJ, O’Laughlin MP. Bedside transseptal balloon dilation atrial septostomy for decompression of the left heart during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 1999;46:197–199. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aiyagari RM, Rocchini AP, Remenapp RT, Graziano JN. Decompression of the left atrium during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation using a transseptal cannula incorporated into the circuit. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:2603–2606. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000239113.02836.F1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Baruteau AE, Barnetche T, Morin L, Jalal Z, Boscamp NS, Le Bret E, Thambo JB, Vincent JA, Fraisse A, Torres AJ. Percutaneous balloon atrial septostomy on top of venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation results in safe and effective left heart decompression. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2018;7:70–79. doi: 10.1177/2048872616675485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Eastaugh LJ, Thiagarajan RR, Darst JR, McElhinney DB, Lock JE, Marshall AC. Percutaneous left atrial decompression in patients supported with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for cardiac disease. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2015;16:59–65. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zampi JD, Alghanem F, Yu S, Callahan R, Curzon CL, Delaney JW, Gray RG, Herbert CE, Leahy RA, Lowery R, et al. Relationship between time to left atrial decompression and outcomes in patients receiving venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support: a multicenter pediatric interventional cardiology early‐career society study. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2019;20:728–736. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kotani Y, Chetan D, Rodrigues W, Ben SV, Gruenwald C, Guerguerian AM, Van Arsdell GS, Honjo O. Left atrial decompression during venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for left ventricular failure in children: current strategy and clinical outcomes. Artif Organs. 2013;37:29–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1594.2012.01534.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rupprecht L, Flörchinger B, Schopka S, Schmid C, Philipp A, Lunz D, Müller T, Camboni D. Cardiac decompression on extracorporeal life support: a review and discussion of the literature. ASAIO J. 2013;59:547–553. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0b013e3182a4b2f6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Desai SR, Hwang NC. Strategies for left ventricular decompression during venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation – a narrative review. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2020;34:208–218. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2019.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hlavacek AM, Atz AM, Bradley SM, Bandisode VM. Left atrial decompression by percutaneous cannula placement while on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130:595–596. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.12.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sperotto F, Cogo P, Amigoni A, Pettenazzo A, Thiagarajan RR, Polito A. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support for failure to wean from cardiopulmonary bypass after pediatric cardiac surgery: analysis of extracorporeal life support organization registry data. Crit Care Explor. 2020;2:e0183. doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jenkins KJ, Gauvreau K, Newburger JW, Spray TL, Moller JH, Iezzoni LI. Consensus‐based method for risk adjustment for surgery for congenital heart disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;123:110–118. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2002.119064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lunceford J, Davidian M. Stratification and weighting via the propensity score in estimation of causal treatment effects: a comparative study. Stat Med. 2004;23:2937–2960. doi: 10.1002/sim.1903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Austin P, Stuart E. Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Stat Med. 2015;34:3661–3679. doi: 10.1002/sim.6607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Holubarsch C, Hasenfuss G, Thierfelder L, Pieske B, Just H. The heart in heart failure: ventricular and myocardial alterations. Eur Heart J. 1991;12:8–13. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/12.suppl_C.8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Soleimani B, Pae WE. Management of left ventricular distension during peripheral extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for cardiogenic shock. Perfus (United Kingdom). 2012;27:326–331. doi: 10.1177/0267659112443722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Truby LK, Takeda K, Mauro C, Yuzefpolskaya M, Garan AR, Kirtane AJ, Topkara VK, Abrams D, Brodie D, Colombo PC, et al. Incidence and implications of left ventricular distention during venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support. ASAIO J. 2017;63:257–265. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Weber C, Deppe AC, Sabashnikov A, Slottosch I, Kuhn E, Eghbalzadeh K, Scherner M, Choi YH, Madershahian N, Wahlers T. Left ventricular thrombus formation in patients undergoing femoral veno‐arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Perfus (United Kingdom). 2018;33:283–288. doi: 10.1177/0267659117745369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mistry MS, Trucco SM, Maul T, Sharma MS, Wang L, West S. Predictors of poor outcomes in pediatric venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. World J Pediatr Congenit Heart Surg. 2018;9:297–304. doi: 10.1177/2150135118762391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tonna JE, Johnson NJ, Greenwood J, Gaieski DF, Shinar Z, Bellezo JM, Becker L, Shah AP, Youngquist ST, Mallin MP, et al. Practice characteristics of emergency department extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (eCPR) programs in the United States: the current state of the art of emergency department extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ED ECMO). Resuscitation. 2016;107:38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.07.237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Russo JJ, Aleksova N, Pitcher I, Couture E, Parlow S, Faraz M, Visintini S, Simard T, Di Santo P, Mathew R, et al. Left ventricular unloading during extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in patients with cardiogenic shock. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:654–662. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.10.085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Morita K, Ihnken K, Buckberg GD, Sherman MP, Young HH, Ignarro LJ. Role of controlled cardiac reoxygenation in reducing nitric oxide production and cardiac oxidant damage in cyanotic infantile hearts. J Clin Invest. 1994;93:2658–2666. doi: 10.1172/JCI117279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hála P, Mlček M, Ošťádal P, Popková M, Janák D, Bouček T, Lacko S, Kudlička J, Neužil P, Kittnar O. Increasing venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation flow puts higher demands on left ventricular work in a porcine model of chronic heart failure. J Transl Med. 2020;18:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02250-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Burkhoff D, Sayer G, Doshi D, Uriel N. Hemodynamics of mechanical circulatory support. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:2663–2674. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Schrage B, Burkhoff D, Rübsamen N, Becher PM, Schwarzl M, Bernhardt A, Grahn H, Lubos E, Söffker G, Clemmensen P, et al. Unloading of the left ventricle during venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation therapy in cardiogenic shock. JACC Heart Fail. 2018;6:1035–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2018.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Thiagarajan RR, Laussen PC, Rycus PT, Bartlett RH, Bratton SL. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation to aid cardiopulmonary resuscitation in infants and children. Circulation. 2007;116:1693–1700. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.680678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Morris MC, Ittenbach RF, Godinez RI, Portnoy JD, Tabbutt S, Hanna BD, Hoffman TM, Gaynor JW, Connelly JT, Helfaer MA, et al. Risk factors for mortality in 137 pediatric cardiac intensive care unit patients managed with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1061–1069. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000119425.04364.CF [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Alsoufi B, Al‐Radi OO, Gruenwald C, Lean L, Williams WG, McCrindle BW, Caldarone CA, Van Arsdell GS. Extra‐corporeal life support following cardiac surgery in children: analysis of risk factors and survival in a single institution. Eur J Cardiothoracic Surg. 2009;35:1004–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.02.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tables S1–S2