Abstract

Background

The relationship between periodontal diseases and Sjogren’s syndrome were found inconsistent in current studies. Our objective is to clarify the relationship between periodontal diseases and Sjogren’s syndrome.

Methods

A systematic review was performed and reported according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). Electronic databases (EMBASE, PubMed, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library, from inceptions until 24 November 2021) were searched. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) were applied to evaluate the quality of studies. Quality assessment of the certainty of evidence was performed based on the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) guidelines. When the output is the ratio, Odds ratio (OR) of periodontal diseases with Sjogren’s syndrome were calculated. When the output is the mean, weighted mean difference (WMD) of periodontal diseases with Sjogren’s syndrome was calculated. We conducted meta-analysis and estimated the pool sensitivity. Begg’s test was used to test the possibility of publication bias. We also carried out meta-regression to clarify the source of heterogeneity (I2 > 50%). Finally, we performed a trial sequential analysis (TSA) to identify the false positive or false negative outcomes that might occur during repeated updates.

Results

21 studies were included in this systematic review, with a total of 11435 subjects. Meta-analysis of 5 studies showed that there is a positive correlation between periodontitis and Sjogren’s syndrome (OR = 2.12, 95% CI = 1.43–3.17; 5 studies, 6927 participants; low certainty of evidence). Meta-analysis of 16 studies showed that the periodontal condition of patients with Sjogren’s syndrome was worse compared with the control group, and the scores of clinical periodontal parameters were relatively high.

Conclusion

Sjogren’s syndrome patients seem to be more likely to be diagnosed with periodontal diseases. However, our results should be interpreted with caution considering the high heterogeneity.

Systematic review registration

[https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/], identifier [CRD42021261322].

Keywords: periodontal disease, observational study, systematic review, meta-analysis, Sjogren’s syndrome

1. Introduction

Periodontal disease is an inflammatory and infectious disease. In the early stages of periodontal disease, the main symptoms are red, swollen and bleeding gums. As the disease progresses, the teeth become loose, mainly due to the development of periodontal pockets and absorption of alveolar bone (1). Gingivitis and periodontitis, the most common forms of periodontal diseases, are triggered by a pathogenic microbiota in the subgingival biofilm. They comprise a variety of inflammatory conditions and periodontitis that could lead to tooth loss and contribute to systemic inflammation (2). Periodontitis is very common in adults and it is more serious in the elderly. It is estimated that about 10−15% of the elderly will develop severe periodontitis (3). The microbial immune subversion, the disturbance of the immune microenvironment and the subsequent systemic inflammatory response in periodontal diseases have been examined for decades (4), which may serve as the causative factor of autoimmune diseases. Some studies have reported that adverse periodontal status may aggravate certain autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis (5, 6), systemic lupus erythematosus (7, 8), Sjogren’s syndrome (SS) (9), thrombocytopenia purpura (10). Thus, there is increasing interest in the potential link between periodontal diseases and certain autoimmune diseases.

Sjogren’s syndrome (SS) is an autoimmune disorder with secretory gland dysfunction charactered by dryness of the main mucosal surfaces including the mouth, eyes, nose, and vagina (11, 12). It can occur alone as primary SS (pSS) or be associated with other systemic diseases as secondary SS (sSS) (13). Incidence and prevalence rates of pSS vary widely around the world. The prevalence rate of pSS was 43.03 cases per 100,000 inhabitants across a series of population-based studies in which the overall age of patients was 56.16 years (14). It is worth mentioning that increasing incidences of oligoptyalism in patients with Sjogren’s syndrome have been reported, which affects the removal of dental plaque and ultimately may lead to periodontal diseases.

According to the published literature in the early years, no significant difference could be detected concerning the periodontal status of SS patients, compared with that of the patients with other immune diseases as well as with that of systemically healthy subjects (15–17). However, in recent years, putative links between periodontal diseases and SS have been reported in several studies. For example, Chuang et al. (18) found that the prevalence (74.6% vs. 63.0%, P = 0.001) and frequency (median 5.37 vs. 1.45 per year, P < 0.001) of dental visits were found higher in patients with pSS and the risk of gingivitis (aIRR 1.43, P < 0.001) and periodontitis (aIRR 1.44, P < 0.001) was also significantly higher them (18). Results of the above researches contradict previous systematic reviews (19). To systematically ascertain whether patients with SS are more likely to be diagnosed with periodontal disease, we included articles that explored the incidence of periodontal diseases in patients diagnosed with SS compared with subjects without SS and conducted this systematic review.

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol and registration

This systematic review was conducted according to the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines (20), the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses standard (PRISMA) (21). It was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42021261322). The research question of this meta-analysis and systematic review was that: is there an association between periodontal disease and SS subjects meeting the following eligibility criteria?

2.2. Eligibility criteria

The strategy for search process was conducted using the PEOS model:

-

(1)

P (patient/participants): subjects aged ≥ 14 years and without other related diseases (such as head and neck tumors);

-

(2)

E (exposure): Sjogren’s syndrome [with the criteria such as the American-European Consensus Group Criteria (AECG), the European Community criteria, etc.];

-

(3)

O (outcome): periodontal disease percentage or clinical periodontal parameters;

-

(4)

S (study design): observational study (cohort, case–control, and cross-sectional studies).

2.3. Information sources and search strategy

We conducted a systematic literature search in the PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library (from their inceptions until 24 November 2021) to investigate the relationship between SS and periodontal diseases. To identify all related datasets and the relevant articles, we used search strategies shown in Supplementary Table 1.

2.4. Study selection and data collection

All retrieved studies were independently assessed by two researchers (XP and JG) based on inclusion/exclusion criteria. For studies whose titles and abstracts might meet the inclusion criteria, the full text was selected for further evaluation. A third author BY was involved when there was a disagreement between the two researchers (XP and JG).

After identifying the included studies that met the criteria, XP and JG extracted the following information: study characteristics (author/s, year of publication, study design, country, and characteristics of participants); periodontal diseases assessment [by clinical diagnosis, oral examination including bleeding on probing (BOP), plaque index (PI), probing pocket depth (PPD), gingival index (GI), and clinical attachment level (CAL) or self-report]; and SS assessment (by clinical diagnosis or clinical examination).

2.5. Risk of bias and applicability assessment

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was applied for assessing case-control studies and cohort studies. The evaluation criteria were Selection, Comparability and Exposure. Stars were awarded each study (up to 9 stars) for quick visual assessment, Studies awarded with 6 or more stars were defined as high quality research (22, 23). For cross-sectional studies, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) methodology checklist was applied. This is a methodological quality assessment tool using an 11-item checklist, and the AHRQ recommends it for assessment of cross-sectional studies. Article quality was assessed as follows: low quality = 0–3; moderate quality = 4–7; high quality = 8–11.

The results of NOS and AHRQ scores can be used for reference in the quality of evidence grading. Two reviewers (XP and JG) independently evaluated the quality of the articles, and a third author (BY) evaluated the articles in case of disagreement.

2.6. Data synthesis

Forest plots were generated to assess the ORs and corresponding 95% CIs or WMDs and 95% CIs across the studies for meta-analysis. The data reported in some studies were standard error of mean (SEM) and we converted them into SD (SEM = SD/√N) (24). Forest plots were generated to intuitively assess the ORs and corresponding 95% CIs in dichotomous variables or weighted mean difference (WMD) and 95% CIs in continuous variables across the articles. Considering the heterogeneity among the included studies, we used a random-effects model.

We assessed the heterogeneity with Cochran’s Q test. If the p-value was lower than 0.1, the I2 statistic was used to quantify the statistical heterogeneity. The threshold was determined as Cochrane recommended, that is 0% to 50%: may not be important; 50% to 100%: may represent substantial heterogeneity (25). In addition, we also carried out meta-regression to clarify the source of heterogeneity. Sensitivity analyses were performed by comparing the pooled sensitivity and specificity results when including and excluding studies with high risk of bias. The Begg’s test was used to test the possibility of publication bias. Finally, we performed a trial sequential analysis (TSA) to identify the false positive or false negative outcomes that might occur during repeated updates. The Stata statistical software version 14 and TSA 0.9 was used to analyze the data. P-values were two-sided, and the significance level was set at 0.05.

The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) guidelines were used for rating the quality of evidence (26). The degree of certainty of evidence is high, moderate, low or very low. Observational studies are initially rated low by default (26) and are downgraded according to the following pre-specified criteria: risk of bias, inconsistency, inaccuracy, inaccuracy, and publication bias (26).

3. Results

3.1. Literature search and study characteristics

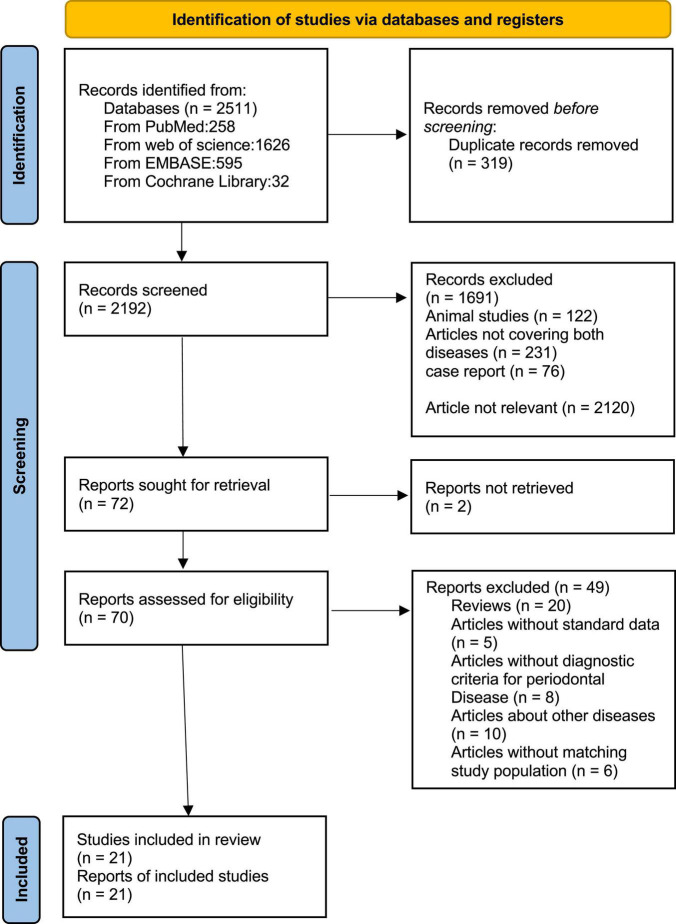

We identified 2511 articles in PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library. After screening the titles and abstracts of all the articles, 72 articles were selected for further evaluation. Then we reviewed the full text of these articles and excluded 51 articles based on inclusion criteria. In the end, there are 21 articles with 11435 participants meeting the inclusion criteria for the meta-analysis (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of study selection.

Among these 21 articles, 5 articles evaluated the percentage of periodontal diseases in SS subjects and non-SS subjects, and 16 reported the diagnostic criteria scores of clinical periodontal parameters (mean ± SD) in SS subjects and non-SS subjects. Among these latter 16 studies, 7 reported BOP scores, 12 reported PI scores, 12 reported PPD scores, 10 reported GI scores, and 6 reported CAL scores. All included studies were observational, including 3 cohort studies, 4 case-control studies, and 14 cross-sectional studies. The total number of participants was 11,435 (9597 SS patients and 1838 non-SS patients). With regard to the age of the participants, the average age of all studies was over 30 years old. 6 of the studies assessed women separately (16, 27–31), while the rest assessed men and women, and were predominantly female. In the control group, all studies included individuals with no other related diseases. In the diagnostic criteria of SS, International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, Clinical Modification coding system (ICD-9-CM) (18, 32) was selected as the diagnostic standard in 2 studies, AECG was selected as the diagnostic standard in 8 studies (27, 29, 31, 33–37), and the European classification criteria for SS was selected in 8 studies (16, 17, 28, 38–42). The Copenhagen Criteria was used in 3 studies (31, 41, 43) and other criteria were used in 2 studies (30, 44). Among the diagnostic criteria for periodontal disease, ICD-9-CM was selected in two studies (18, 32), self-report was selected in one study (27), “clinical examination” was only reported in one study without explicit description of examination content (34), and clinical indicators were reported in the rest of the studies (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the included studies on the prevalence of periodontal diseases in patients with Sjogren’s syndrome.

| References | Study design | Country | Age, years | Periodontal diseases assessment | SS assessment | n (control) | n (SS cases) | Number of participants | Women (%) | Fundings |

| Chuang et al. (18) | Cohort | China | Range: 20−80 | Gingivitis: ICD-9-CM: 523.0, 523.1, and 523.2Periodontitis: ICD-9-CM: 523.3, 523.4, 523.5, and 523.8 | ICD-9-CM: 710.2 | 7090 | 709 | 7799 | 88.9% | − |

| Albrecht et al. (27) | Cohort | Germany | Patients range: 24−80; mean ± SD: 58.1 ± 12Controls range: 19−76; mean ± SD: 54.1 ± 14 | Self-reported | AECG | 87 | 205 | 292 | 100% | − |

| Lu et al. (32) | Cohort | China | Mean ± SD: 54 ± 14 | Gingivitis: ICD-9-CM: 523.0–523.9Periodontitis: ICD-9-CM: 523.3–523.5 | ICD-9-CM: 710.2 | 1945 | 389 | 2334 | 90% | − |

| Ozcaka et al. (33) | Cross-sectional case control | Turkey | Mean ± SD: 51.1 ± 14.1 | PPD, PI, BOP | AECG | 25 | 44 | 69 | − | The Research Foundation of Ege University, Izmir, Turkey. |

| Crincoli et al. (34) | Case–control | Italy | Patients range: 21−82; mean ± SD: 56.06 ± 12.19Controls range: 19−76; mean ± SD: 55.32 ± 12.17 | Clinical examination | AECG | 72 | 72 | 144 | 97.2% | − |

| Ergun et al. (44) | Case–control | Turkey | Patients range: 26−78; mean: 53.27Controls range: 25−94; mean: 54.27 | PPD, API, BOP | The recently modified internationally agreed-on criteria for SS | 37 | 37 | 74 | − | − |

| Antoniazzi et al. (17) | Cross-sectional | Brazil | Mean ± SD: 50.1 ± 12.5pSS mean ± SD: 48.1 ± 13.4sSS mean ± SD: 53.8 ± 11.6Controls mean ± SD: 49.8 ± 12.8 | PI, GI, CAL, PPD, BOP | The European Community criteria | 19 | 19 | 38 | 50% | − |

| Pedersen et al. (31) | Case–control | Denmark | Patients Mean ± SD: 60 ± 15Controls Mean ± SD: 56 ± 13 | PI, GI, PPD | AECG; the Copenhagen criteria | 20 | 20 | 40 | 100% | − |

| Leung et al. (38) | Cross-sectional | China | pSS range: 33−76; mean ± SD: 51.4 ± 14.3sSS range: 27−66; mean ± SD: 43.3 ± 10.9Controls range: 27−75; mean ± SD: 44.0 ± 10.7 | PI, CI, CAL | The European Community Diagnostic Criteria | 29 | 51 | 80 | 93.33% | CRCG grant from the University of Hong Kong. |

| Najera et al. (39) | Cross-sectional | United States | Patients range: 28 - 80; mean ± SD: 60.92 ± 13.52Controls range: 30 – 77; mean ± SD: 58.29 ± 12.09 | PI, GI, BOP, PPD, CAL | The European Community Criteria | 24 | 25 | 49 | 91.84% | − |

| Tervahartiala et al. (43) | Cross-sectional | Denmark | Patients range: 38−63; mean: 52Controls range: 27−42; mean: 31 | PI, PPD, GBI | The Copenhagen criteria | 6 | 8 | 14 | − | The Finnish Academy; the Kordelin Foundation; the Research Foundation for Women; the Finnish Dental Association. |

| Ambrosio et al. (29) | Cross-sectional | Brazil | Patients Mean ± SD: 52.14 ± 14.1Controls Mean ± SD: 49 ± 6.73 | PPD, CAL, BOP, PI | AECG | 7 | 7 | 14 | 100% | The SALIVA Research Nucleus of Support (NAP-SALIVA) of the University of São Paulo; the research grants from São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP, respectively, 2015/07396-2, and 2013/26381-0); the scholarships from FAPESP (respectively, 2014/06387-7, and 2015/24061-4). |

| Marton et al. (35) | Cross-sectional | Hungary | Range: 32–76Patients Mean ± SD: 55 ± 11Controls Mean ± SD: 49 ± 15 | GBI, PPD, BOP | AECG | 43 | 49 | 92 | 92.39% | The Hungarian Scientific Research Fund (OTKA no. T-037776); the Hungarian Medical Research Council (ETT-247/2003). |

| Kuru et al. (16) | Cross-sectional | England | pSS range: 35−77; mean ± SD: 61.2 ± 14.4sSS range: 43−77; mean ± SD: 60.6 ± 11.8Controls range: 40−77; mean ± SD: 61.8 ± 13.09 | PI, GI, BOP, PPD, CAL | The European Community Criteria | 11 | 18 | 29 | 100% | − |

| Pedersen et al. (40) | Cross-sectional | Norway | Patients range: 40−82; Mean: 61.4Controls range: 39−70; Mean: 50 | PI, GI, PPD | The European classification criteria for SS | 14 | 16 | 30 | 90% | The Ingeborg and Leo Dannin Foundation; the Danish Dental Association Research Foundation (DTF’s Forskningsfond and FUT); the Colgate Research Foundation; the Ib Henriksen Research Foundation. |

| Pedersen et al. (41) | Cross-sectional | Denmark | Patients range: 40−82; Mean: 64.1Controls range: 39−70; Mean: 64.8 | PI, GI, PPD | European classification criteria for SS and the Copenhagen criteria | 20 | 20 | 40 | 82.5% | The Zendium Household and Body Care Research Foundation; the Danish Dental Association Research Foundation (DTF’s forskningsfond and FUT). |

| Tseng (30) | Cross-sectional | United States | Patients Mean: 52.9Controls Mean: 53.7 | GI, PI, BI, PPD, CAL | NS | 14 | 14 | 28 | 100% | − |

| Zoppo et al. (42) | Cross-sectional | Venezuela | Patients range: 43−68; Mean ± SD: 54.8 ± 10Controls range: 21−43; Mean ± SD: 32 ± 8.34 | GI, PI, PPD | The European classification criteria for SS | 6 | 7 | 13 | 69.23% | − |

| Seck-Diallo et al. (36) | Cross-sectional | Senegal | pSS mean ± SD: 46.7 ± 2.5sSS mean ± SD: 48.2 ± 1.4 | PI, GI, PPD, CAL | AECG | 103 | 103 | 206 | 91.26% | − |

| Pers et al. (37) | Cross-sectional | France | Patients range: 44−81Controls range: 39−82 | PI, GI, BOP, PPD | AECG | 15 | 15 | 30 | 83.3% | − |

| Rhodus and Michalowicz (28) | Cross-sectional study | United States | Patients range: 43−74; Mean: 56.7Controls range: 32−65; Mean: 52.6 | PI, GI, PPD, CAL | The comprehensive European Community Criteria | 10 | 10 | 20 | 100% | − |

ICD-9-CM, the International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision, Clinical Modification coding system; AECG, the American-European Consensus Group Criteria; BOP, bleeding on probing; PI, plaque index; PPD, probing pocket depth; GI, gingival index; CAL, clinical attachment level; MPD, mean probing depth; CPD, cumulative probing depth; API, approximal plaque index; CI, calculus indices; MAL, mean attachment loss; PAL, probing attachment level; GBI, gingival bleeding index.

The NOS scores and the AHRQ methodology checklist for quality assessment of these studies are shown in Tables 2, 3. The GRADE assessment is shown in Table 4.

TABLE 2.

Quality assessment of cohort studies and case–control studies with the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS).

| References | Study design | Selection | Comparability | Exposure/outcome | Summary score | ||||||

| Chuang et al. (18) | Cohort | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | 9/9 |

| Albrecht et al. (27) | Cohort | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | 5/9 | ||||

| Lu et al. (32) | Cohort | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | 9/9 |

| Ozcaka et al. (33) | Case control | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | 8/9 | |

| Crincoli et al. (34) | Case control | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | 5/9 | ||||

| Ergun et al. (44) | Case control | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | 7/9 | ||

| Pedersen et al. (31) | Case control | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | ✩ | 5/9 | ||||

TABLE 3.

Quality assessment of cross-sectional studies with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) methodology checklist.

| References | Study design | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | Summary score |

| Antoniazzi et al. (17) | Cross-sectional | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 8/11 |

| Leung et al. (38) | Cross-sectional | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5/11 |

| Najera et al. (39) | Cross-sectional | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4/11 |

| Tervahartiala et al. (43) | Cross-sectional | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2/11 |

| Ambrosio et al. (29) | Cross-sectional | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 8/11 |

| Marton et al. (35) | Cross-sectional | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3/11 |

| Kuru et al. (16) | Cross-sectional | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5/11 |

| Pedersen et al. (40) | Cross-sectional | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4/11 |

| Pedersen et al. (41) | Cross-sectional | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6/11 |

| Tseng (30) | Cross-sectional | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3/11 |

| Zoppo et al. (42) | Cross-sectional | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3/11 |

| Seck-Diallo et al. (36) | Cross-sectional | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4/11 |

| Pers et al. (37) | Cross-sectional | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3/11 |

| Rhodus and Michalowicz (28) | Cross-sectional | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5/11 |

TABLE 4.

The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) assessment for the incidence of periodontal disease on Sjogren’s syndrome subjects.

| Outcome | No. of studies | Study design | Certainty assessment | OR (WMD) [95% CI] | Certainty | ||||

| Risk of bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Other considerations | |||||

| Incidence of periodontal disease | 5 | Observational study | Not serious | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | OR = 2.12, 95% CI = 1.43–3.17 | ⊕⊕ LOW |

| BOP | 7 | Observational study | Not serious | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | WMD = 9.62, 95% CI = 3.43–15.80 | ⊕ VERY LOW |

| PI | 12 | Observational study | Not serious | Serious | Not serious | Serious | None | WMD = 0.15, 95% CI = −0.00–0.30 | ⊕ VERY LOW |

| GI | 10 | Observational study | Not serious | Serious | Not serious | Not serious | None | WMD = 0.28, 95% CI = 0.04–0.51 | ⊕ VERY LOW |

| PPD | 12 | Observational study | Not serious | Serious | Not serious | Serious | None | WMD = 0.22, 95% CI = −0.19–0.63 | ⊕ VERY LOW |

| CAL | 6 | Observational study | Not serious | Serious | Not serious | Serious | None | WMD = 0.40, 95% CI = −0.00–0.81 | ⊕ VERY LOW |

OR, odds ratio; WMD, weighted mean difference.

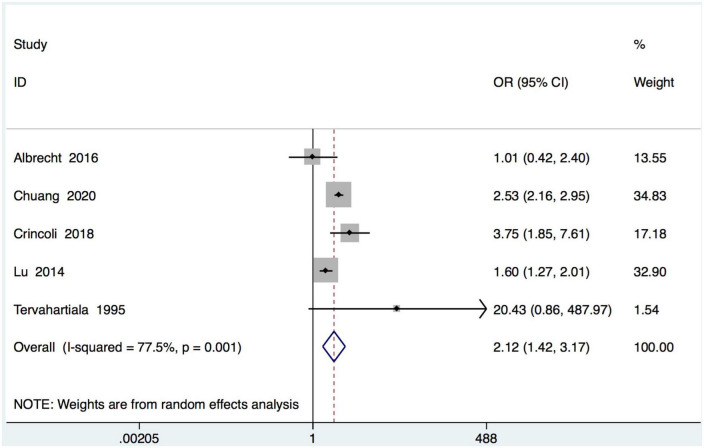

3.2. Study of periodontal diseases in SS subjects

Five studies recording the incidence of periodontitis in SS subjects (Table 1). In the meta-analysis of these 5 studies, a positive association between SS and periodontal diseases was found and SS patients were more likely to be diagnosed with periodontal diseases than healthy controls (OR = 2.12, 95% CI = 1.43–3.17; 5 studies, 6927 participants; low certainty of evidence, I2 = 77.5%) (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Forest plot for periodontal diseases in subjects with Sjogren’s syndrome (SS) and controls. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

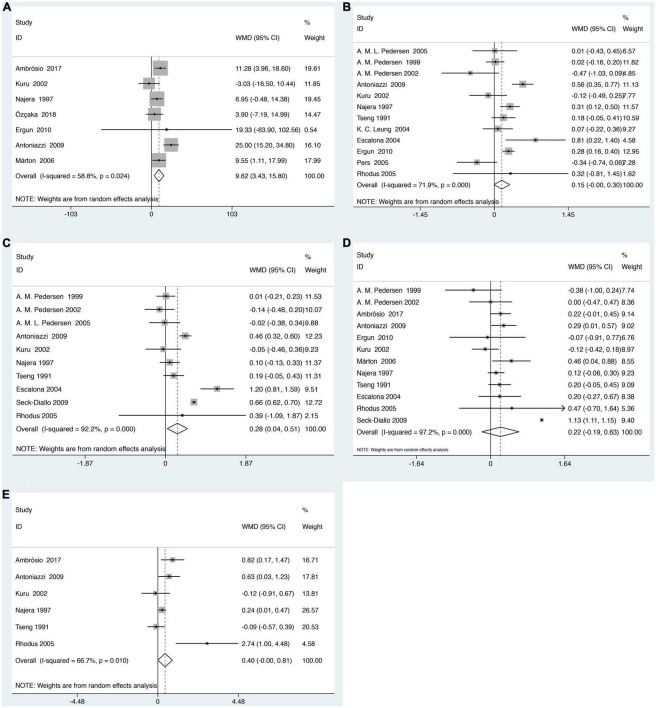

There are 16 studies reporting clinical periodontal parameters scores, which recorded in 455 subjects with SS and 397 healthy subjects (Table 1). Subjects with SS had significant difference in the clinical periodontal parameters scores BOP (WMD = 9.62, 95% CI = 3.43–15.80, I2 = 58.8%) and GI (WMD = 0.28, 95% CI = 0.04–0.51, I2 = 92.2%) was found. However, subjects with SS had no significant difference in the clinical periodontal parameters scores PPD (WMD = 0.22, 95% CI = −0.19–0.63, I2 = 97.2%). Finally, the relationship between the SS and the clinical parameters scores CAL (WMD = 0.40, 95% CI = −0.00–0.81, I2 = 66.7%) and PI (WMD = 0.15, 95% CI = −0.00–0.30, I2 = 71.9%) is not very clear (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Forest plot for SS and clinical periodontal parameters scores (A). Clinical periodontal parameters scores bleeding on probing (BOP) (B). Clinical periodontal parameters scores plaque index (PI) (C). Clinical periodontal parameters scores gingival index (GI) (D). Clinical periodontal parameters scores probing pocket depth (PPD) (E). Clinical periodontal parameters scores clinical attachment level (CAL). WMD, weighted mean difference; CI, confidence interval.

3.3. Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were performed by comparing the pooled sensitivity and specificity results when including and excluding studies with high risk of bias. There are no substantial changes in the meta-analysis results of the pooled ORs with corresponding 95% CIs (for the association between periodontal diseases and SS) and the pooled WMD s with corresponding 95% CIs (for the mean difference in the clinical periodontal parameter scores between subjects with SS and healthy controls), indicating that our meta-analysis is relatively stable (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Sensitivity analysis. The pooled ORs (WMDs) and 95% CIs were stable after the deletion of each study in the analysis of the association between SS and controls (A). The association between periodontal diseases and SS (B). Clinical periodontal parameters scores BOP (C). Clinical periodontal parameters scores PI (D). Clinical periodontal parameters scores GI (E). Clinical periodontal parameters scores PPD (F). Clinical periodontal parameters scores CAL. CI, confidence interval.

3.4. Publication bias

Potential publication bias was analyzed using Begg’s test in at least 10 studies included in the analyses. No significant publication bias was found in the WMD for clinical periodontal parameters scores PI (p = 0.537), GI (p = 0.721), and PPD (p = 0.086) between subjects with SS and healthy controls (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Begg’s funnel plot analysis to detect publication bias for the association between periodontal diseases and SS (A). Clinical periodontal parameters scores PI (B). Clinical periodontal parameters scores GI (C). Clinical periodontal parameters scores PPD. WMD, weighted mean difference.

3.5. Meta-regression

Meta-regression was used to investigate potential sources of heterogeneity between the studies. We found that when the outcome variable was the percentage of periodontitis (p = 0.031), PI (p = 0.050), and GI (p < 0.001) age was one source of heterogeneity. When the outcome variable was PPD, the diagnostic criteria for SS was at least a source of heterogeneity (p = 0.025).

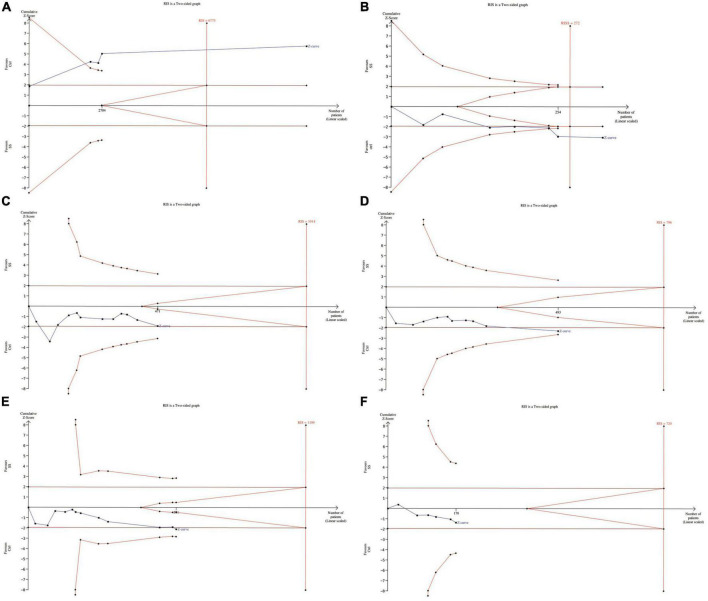

3.6. Trial sequential analysis

In meta-analyses, it is important to minimize the risk of false positive or false negative results. We therefore performed a TSA to control the risks for type I and type II errors and help to clarify whether additional trials are needed.

The results showed that for dichotomous variables, the meta-analysis can be declared as conclusive with regard to the anticipated effect leading to the required information size. That is, we can conclude that SS patients were more likely to be diagnosed with periodontal disease than healthy controls. Similarly, the continuous variable BOP also drew significant conclusions with enough information size (45).

For GI, although the meta-analysis came to a positive conclusion, it may have been declared not significant by TSA at this information size, meaning a false positive result. As for PI, PPD and CAL, irrelevant conclusions from meta-analysis are also inconclusive due to insufficient information. In fact, more tests need to be included for confirmation (46) (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Trial sequential analysis of trials in subjects with SS (A). The association between periodontal disease and SS (B). Clinical periodontal parameters scores BOP (C). Clinical periodontal parameters scores PI (D). Clinical periodontal parameters scores GI (E). Clinical periodontal parameters scores PPD (F). Clinical periodontal parameters scores CAL. RIS, required information size.

4. Discussion

4.1. General interpretation of main results

In this meta-analysis of the studies on periodontal diseases and SS, we included 21 articles with 11435 participants meeting the inclusion criteria. GRADE Quality of evidence Indicates that the quality of evidence included in the study is not high. A positive association between periodontal diseases and SS was found. Subjects with SS had significantly higher clinical periodontal parameter scores BOP (WMD = 9.62, 95% CI = 3.43–15.80) and GI (WMD = 0.28, 95% CI = 0.04–0.51). However, there is no significant difference in the clinical periodontal parameters scores PI (WMD = 0.15, 95% CI = −0.00–0.30) and PPD (WMD = 0.22, 95% CI = −0.19–0.63) in SS patients. TSA trail showed that for dichotomous variables, the meta-analysis can be declared as conclusive with regard to the anticipated effect leading to the required information size. Similarly, the continuous variable BOP also drew significant conclusions with enough information size. For GI, PI, PPD, and CAL, more tests need to be included for confirmation.

4.2. Strengths and limitations of the review

There are several strengths in Our meta-analysis. First, we searched all relevant databases as thoroughly as possible to include more studies that met the criteria. Second, we performed GRADE evidence quality grading to reflect the accuracy of the effect estimates. Third, we conducted TSA Trail to manage the risk of type I and II errors and to help determine whether additional trials are needed. Therefore, our analysis could well reflect the trial effect and illustrate the clinical guiding significance of the indicator.

There are also limitations in our study. First, the results had relatively high statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 77.5%, 58.8%, 71.9%, 92.2%, 97.2%, and 66.7%) across the studies. Although we tried meta-regression to explore the sources of heterogeneity and obtained some sources of heterogeneity, we did not find more sources of heterogeneity due to the lack of more detailed description of research characteristics in the included studies. Second, although some positive conclusions are reached in TSA Trail results, some conclusions are still unstable and lack sufficient information. Therefore, the current conclusions may change with the increase of studies. Third, because a small part of the included study data came from dental clinics, patients from dental clinics may have some dental diseases or have some symptoms, so these patients are more likely to suffer from periodontal disease. In contrast, patients from other places such as Sjogren’s Syndrome Service of the Hospital Clinics showed no such bias. All in all, the results we get may lean toward “correlation.” In addition, we tried to search the studies on the incidence of Sjogren’s syndrome in patients with periodontal disease. Unfortunately, due to the retrieval of only two articles (47, 48), meta-analysis could not be conducted, and further relationship could not be obtained. However, both papers concluded that patients with periodontal disease were more likely to have Sjogren’s syndrome. To some extent, we believe that such conclusions can help to prove the relationship between Sjogren’s syndrome and periodontal disease. Our results should be interpreted with caution considering the existence of multiple conditions.

4.3. Implications for practice and future research

According to previous studies, periodontal diseases and SS have been considered to be related (47), which has been shown by quite a few studies. SS patients had a higher incidence of tooth loss, a higher risk ratio of undergoing one or more tooth extractions, and significantly more SS patients were edentulous, which may be related to reduced salivary secretion (49). SS can lead to a decrease in saliva flow and a change in its composition, which affects the removal of bacteria in the oral cavity and thus facilitates the accumulation of plaque on the surface of teeth, which contributes to the deterioration of clinical periodontal parameters and, in severe cases, periodontal diseases (15). It has also been reported that the salivary glands of patients with SS are characterized by lymphocytes gathering around the salivary ducts, which plays an important role in driving the local immune response (50). The capillaries of gingival microcirculation in patients with SS have been changed, which may be related to the occurrence of periodontal diseases (51). Moreover, it has been found that the patients with Sjogren’s syndrome had higher serum concentrations of anti-periodontal pathogens such as Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis. Furthermore, alterations in cytokine networks may act as an intermediate factor between periodontal diseases and SS. More inflammatory cytokines were also found in the oral cavity of patients with SS, which can stimulate the differentiation of immune cells, thus affecting the occurrence and development of periodontal diseases (17, 52). However, the underlying pathophysiological mechanism between periodontal diseases and Sjogren’s syndrome are so complex that by now, it has not been fully understood (47). Unfortunately, we still have no conclusive evidence to judge the relationship between periodontal disease and Sjogren’s syndrome.

Despite the lack of clear evidence, our meta-analysis still has its value for the clinical prevention and treatment of periodontal diseases and SS. The first consultation department of many SS patients is the dental department because dry mouth and dental caries are the initial symptoms of them. This meta-analysis is the first to explore the correlation between periodontal diseases and SS from the perspective of dentists and patients. From the perspective of dentists, the periodontal condition of SS patients should also be paid attention to when they are diagnosed and treated. If timely measures are taken to improve the periodontal condition, SS patients are expected to reduce or even avoid the progressive loss of periodontal tissue. From the patient’s point of view, the symptoms of periodontal disease and SS may serve as reminders of each other, and patients should pay close attention to the other when one is diagnosed. We believe that the treatment of SS is helpful in alleviating periodontal diseases, and the awareness of patients and clinicians on SS may contribute to the successful treatment of periodontal diseases. Future scientific studies should further verify the correlation between these two diseases and explore the mechanism and molecular pathway of their association.

5. Conclusion

This systematic review indicated that SS patients were more likely to be diagnosed with periodontal diseases, and the periodontal index is more likely to be abnormal, suggesting that the treatment of SS has a positive effect on periodontitis.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

BY and XP put forward the ideas, searched the literature, filtered the information, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. JG prepared the figures and tables and checked for errors. XuL, XiL, YW, ZC, and BC reviewed the manuscript, put forward the constructive comments, and participated in its design and coordination. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82001109, 81970975, and 81630025), the State Key Laboratory of Oral Diseases (SKLOD) Open Fund (SKLOD2022OF06), Open Funding of Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Stomatology (KF2021120103 and KF2020120102), the Guangdong Financial Fund for High-Caliber Hospital Construction (174-2018-XMZC-0001-03-0125/D-09 and 174-2018-XMZC-0001-03-0125/D-10), and Special Funds for the Cultivation of Guangdong College Students’ Scientific and Technological Innovation (“Climbing Program”) Special Funds (pdjh2023b0017).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2022.904638/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.Zheng D, Kang X, Wang Y, Huang Y, Pang C, Chen Y, et al. Periodontal disease and emotional disorders: a meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol. (2021) 48:180–204. 10.1111/jcpe.13395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kinane D, Stathopoulou P, Papapanou P. Periodontal diseases. Nat Rev Dis Primers. (2017) 3:17038. 10.1038/nrdp.2017.38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ebersole J, Graves C, Gonzalez O, Dawson D, III, Morford L, Huja P, et al. Aging, inflammation, immunity and periodontal disease. Periodontol 2000. (2016) 72:54–75. 10.1111/prd.12135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hajishengallis G. Periodontitis: from microbial immune subversion to systemic inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. (2015) 15:30–44. 10.1038/nri3785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergot A, Giri R, Thomas R. The microbiome and rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. (2019) 33:101497. 10.1016/j.berh.2020.101497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Culshaw S, McInnes I, Liew F. What can the periodontal community learn from the pathophysiology of rheumatoid arthritis? J Clin Periodontol. (2011) 38(Suppl. 11):106–13. 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2010.01669.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sojod B, Pidorodeski Nagano C, Garcia Lopez G, Zalcberg A, Dridi S, Anagnostou F. Systemic lupus erythematosus and periodontal disease: a complex clinical and biological interplay. J Clin Med. (2021) 10:1957. 10.3390/jcm10091957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pessoa L, Aleti G, Choudhury S, Nguyen D, Yaskell T, Zhang Y, et al. Host-microbial interactions in systemic lupus erythematosus and periodontitis. Front Immunol. (2019) 10:2602. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maarse F, Jager D, Alterch S, Korfage A, Forouzanfar T, Vissink A, et al. Sjögren’s syndrome is not a risk factor for periodontal disease: a systematic review. Clin Exp Rheumatol. (2019) 37(Suppl. 118):225–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fenner M, Frankenberger R, Pressmar K, John S, Neukam F, Nkenke E. Life-threatening thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura associated with dental foci. Report of two cases. J Clin Periodontol. (2004) 31:1019–23. 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2004.00617.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brito-Zerón P, Baldini C, Bootsma H, Bowman S, Jonsson R, Mariette X, et al. Sjögren syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. (2016) 2:16047. 10.1038/nrdp.2016.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, Sisó-Almirall A, Bosch X. Primary Sjogren syndrome. BMJ. (2012) 344:e3821. 10.1136/bmj.e3821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun X, Lu L, Li Y, Yang R, Shan L, Wang Y. Increased risk of thyroid disease in patients with Sjogren’s syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PeerJ. (2019) 7:e6737. 10.7717/peerj.6737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qin B, Wang J, Yang Z, Yang M, Ma N, Huang F, et al. Epidemiology of primary Sjögren’s syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis. (2015) 74:1983–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boutsi E, Paikos S, Dafni U, Moutsopoulos H, Skopouli F. Dental and periodontal status of Sjogren’s syndrome. J Clin Periodontol. (2000) 27:231–5. 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2000.027004231.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuru B, McCullough M, Yilmaz S, Porter S. Clinical and microbiological studies of periodontal disease in Sjogren syndrome patients. J Clin Periodontol. (2002) 29:92–102. 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2002.290202.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Antoniazzi R, Miranda L, Zanatta F, Islabao A, Gustafsson A, Chiapinotto G, et al. Periodontal conditions of individuals with Sjogren’s syndrome. J Periodontol. (2009) 80:429–35. 10.1902/jop.2009.080350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chuang C, Hsu C, Lu M, Koo M. Increased risk of developing dental diseases in patients with primary Sjogren’s syndrome-A secondary cohort analysis of population-based claims data. PLoS One. (2020) 15:e0239442. 10.1371/journal.pone.0239442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Goes Soares L, Rocha R, Bagordakis E, Galvao E, Douglas-de-Oliveira D, Falci S. Relationship between sjogren syndrome and periodontal status: a systematic review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. (2018) 125:223–31. 10.1016/j.oooo.2017.11.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stroup D, Berlin J, Morton S, Olkin I, Williamson G, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. (2000) 283:2008–12. 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D, Group P. Reprint–preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Phys Ther. (2009) 89:873–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Araujo M, Martins C, Costa L, Cota L, Faria R, Cunha F, et al. Association between depression and periodontitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol. (2016) 43:216–28. 10.1111/jcpe.12510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu F, Wen Y, Zhou Y, Lei G, Guo Q, Dang YH. A meta-analysis of emotional disorders as possible risk factors for chronic periodontitis. Medicine. (2018) 97:e11434. 10.1097/MD.0000000000011434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Livingston E. The mean and standard deviation: what does it all mean? J Surg Res. (2004) 119:117–23. 10.1016/j.jss.2004.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cumpston M, Li T, Page M, Chandler J, Welch V, Higgins J, et al. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2019) 10:ED000142. 10.1002/14651858.ED000142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balshem H, Helfand M, Schunemann H, Oxman A, Kunz R, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. (2011) 64:401–6. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Albrecht K, Callhoff J, Westhoff G, Dietrich T, Dorner T, Zink A. The prevalence of dental implants and related factors in patients with Sjogren syndrome: results from a cohort study. J Rheumatol. (2016) 43:1380–5. 10.3899/jrheum.151167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rhodus N, Michalowicz B. Periodontal status and sulcular Candida albicans colonization in patients with primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Quintessence Int. (2005) 36:228–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ambrosio L, Rovai E, Franca B, Balzarini D, Abreu I, Lopes S, et al. Effects of periodontal treatment on primary Sjogren’s syndrome symptoms. Braz Oral Res. (2017) 31:e8. 10.1590/1807-3107BOR-2017.vol31.0008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tseng C. Periodontal status of patients with Sjogren’s syndrome: a cross-sectional study. J Formos Med Assoc. (1991) 90:109–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pedersen A, Bardow A, Nauntofte B. Salivary changes and dental caries as potential oral markers of autoimmune salivary gland dysfunction in primary Sjogren’s syndrome. BMC Clin Pathol. (2005) 5:4. 10.1186/1472-6890-5-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu M, Jheng C, Tsai T, Koo M, Lai N. Increased dental visits in patients prior to diagnosis of primary Sjogren’s syndrome: a population-based study in Taiwan. Rheumatol Int. (2014) 34:1555–61. 10.1007/s00296-014-3003-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ozcaka O, Alpoz E, Nalbantsoy A, Karabulut G, Kabasakal Y. Clinical periodontal status and inflammatory cytokines in primary Sjogren syndrome and rheumatoid arthritis. J Periodontol. (2018) 89:959–65. 10.1002/JPER.17-0730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crincoli V, Di Comite M, Guerrieri M, Rotolo R, Limongelli L, Tempesta A, et al. Orofacial manifestations and temporomandibular disorders of Sjogren syndrome: an observational study. Int J Med Sci. (2018) 15:475–83. 10.7150/ijms.23044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marton K, Boros I, Varga G, Zelles T, Fejerdy P, Zeher M, et al. Evaluation of palatal saliva flow rate and oral manifestations in patients with Sjogren’s syndrome. Oral Dis. (2006) 12:480–6. 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2005.01224.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seck-Diallo A, Diallo S, Benoist H, Diouf A, Sembene M, Diallo P. Periodontal status of Senegalese patients with Sjogren’s syndrome. A case control study at the Service of Internal Medicine. Odontostomatol Trop. (2009) 32:39–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pers J, d’Arbonneau F, Devauchelle-Pensec V, Saraux A, Pennec Y, Youinou P. Is periodontal disease mediated by salivary BAFF in Sjogren’s syndrome? Arthritis Rheum. (2005) 52:2411–4. 10.1002/art.21205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leung K, McMillan A, Leung W, Wong M, Lau C, Mok T. Oral health condition and saliva flow in southern Chinese with Sjogren’s syndrome. Int Dent J. (2004) 54:159–65. 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2004.tb00273.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Najera M, Al-Hashimi I, Plemons J, Rivera-Hidalgo F, Rees T, Haghighat N, et al. Prevalence of periodontal disease in patients with Sjogren’s syndrome. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. (1997) 83:453–7. 10.1016/s1079-2104(97)90144-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pedersen A, Reibel J, Nordgarden H, Bergem H, Jensen J, Nauntofte B. Primary Sjogren’s syndrome: salivary gland function and clinical oral findings. Oral Dis. (1999) 5:128–38. 10.1111/j.1601-0825.1999.tb00077.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pedersen A, Andersen T, Reibel J, Holmstrup P, Nauntofte B. Oral findings in patients with primary Sjogren’s syndrome and oral lichen planus–a preliminary study on the effects of bovine colostrum-containing oral hygiene products. Clin Oral Investig. (2002) 6:11–20. 10.1007/s00784-001-0148-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zoppo F, Bertaglia E, Tondo C, Colella A, Mantovan R, Senatore G, et al. High prevalence of cooled tip use as compared with 8-mm tip in a multicenter Italian registry on atrial fibrillation ablation: focus on procedural safety. J Cardiovasc Med. (2008) 9:888–92. 10.2459/JCM.0b013e3282f7352a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tervahartiala T, Ingman T, Sorsa T, Ding Y, Kangaspunta P, Konttinen Y. Proteolytic enzymes as indicators of periodontal health in gingival crevicular fluid of patients with Sjogren’s syndrome. Eur J Oral Sci. (1995) 103:11–6. 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1995.tb00004.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ergun S, Cekici A, Topcuoglu N, Migliari D, Kulekci G, Tanyeri H, et al. Oral status and Candida colonization in patients with Sjogren’s Syndrome. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. (2010) 15:e310–5. 10.4317/medoral.15.e310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wetterslev J, Thorlund K, Brok J, Gluud C. Trial sequential analysis may establish when firm evidence is reached in cumulative meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. (2008) 61:64–75. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brok J, Thorlund K, Gluud C, Wetterslev J. Trial sequential analysis reveals insufficient information size and potentially false positive results in many meta-analyses. J Clin Epidemiol. (2008) 61:763–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin C, Tseng C, Liu J, Chuang H, Lei W, Liu L, et al. Association between Periodontal Disease and Subsequent Sjogren’s Syndrome: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin T, Tseng C, Wang Y, Yu H, Chang Y. Patients with chronic periodontitis present increased risk for primary Sjogren syndrome: a nationwide population-based cohort study. PeerJ. (2018) 6:e5109. 10.7717/peerj.5109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maarse F, Jager D, Forouzanfar T, Wolff J, Brand H. Tooth loss in Sjogren’s syndrome patients compared to age and gender matched controls. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. (2018) 23:e545–51. 10.4317/medoral.22545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lugonja B, Yeo L, Milward M, Smith D, Dietrich T, Chapple I, et al. Periodontitis prevalence and serum antibody reactivity to periodontal bacteria in primary Sjogren’s syndrome: a pilot study. J Clin Periodontol. (2016) 43:26–33. 10.1111/jcpe.12485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scardina G, Ruggieri A, Messina P. Periodontal disease and sjogren syndrome: a possible correlation? Angiology. (2010) 61:289–93. 10.1177/0003319709344576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee C, Choy C, Lai Y, Chang C, Teng N, Huang W, et al. A cross-sectional study of endogenous antioxidants and patterns of dental visits of periodontitis patients. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:180. 10.3390/ijerph16020180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.