Abstract

Background

Over the last number of years, the healthcare system has become more complex in managing increasing costs and outcomes within a defined budget. To be effective through reform, especially moving forward from the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare leaders, specifically in nursing, have an increased need for business acumen beyond traditional leadership and management principles.

Aim

This paper examines the concept of business acumen in the profession of nursing, specifically for managers and higher nurse leaders, establishing whether these skills are optional or essential.

Discussion

Nurses learn and develop broad skills in leadership and management, but less specifically about business or the broader system. With a contemporary Australian health system aiming to be more effective, nurses may require a greater level of business acumen to adequately understand the mechanics of business decision making in the system when designing care models, as well as representing the business potential of nursing in balance with clinical outcomes through reform.

Conclusion

The modern nurse, in addition to clinical skills, may need a foundational understanding of business evolving throughout their career, to maximise innovative growth across the system, in meeting the healthcare needs of our community now and into the future. Without a foundation level of business acumen and an understanding of the system across the profession, nurses may not be empowered with their full potential of being a strong voice influencing health system reform.

Keywords: Nursing, Leadership, Business, Skills, Acumen, System

Summary of relevance

Problem

Across the world, including Australia more recently, healthcare has become more of a business than a social enterprise. Clinician leaders including nurses, have skills in leadership and management, but inconsistent business acumen or knowledge of the broader system.

What is already known?

Understanding business principles enable leaders to develop and influence sustainable solutions in balancing system resources with clinical outcomes. While business acumen itself is not a new concept across many industries, these skills are less common for clinicians.

What this paper adds?

Understanding the importance of business acumen for nursing leaders will identify gaps in the profession's current leadership and management skillset, as well as highlighting the enhanced value of nursing leaders consistently possessing these business skills. This discussion may also identify opportunities for future growth through training.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

1. Introduction

Effective leadership in healthcare has grown in importance as we work through the pandemic (Dudzic, 2021). Healthcare is typically an industry associated with the provision of services that address illness and injury (Mahoney, 2001; Thew, 2020; WHO, 2019). Historically, there has been less focus on cost containment with this provision of care (WHO, 2019). However, with modern day advances in treatment and technology consuming a greater percentage of government and household spending, the healthcare industry has seen a shift over the last two or more decades from ‘care at any cost’ to sustaining a care delivery system working within a defined budget (WHO, 2019). The COVID-19 pandemic has further highlighted the importance of sustainable budgeting in conjunction with health service delivery (Dudzic, 2021). In nursing however, this potentially introduces a clash of values between two paradigms being care and cost (Bamford-Wade & Moss, 2010).

With the introduction of managerialism through reform in the early 2000s that highlighted the importance of leadership skills beyond the delivery of care, sustainability practices of health service delivery have been now somewhat embedded as normal business across the system (Bamford‐Wade & Moss, 2010; Pierce, 2016). However, embedding managerialism raises the question, “are our clinicians sufficiently knowledgeable in terms of business acumen to best perform in this more fiscally focused environment, while at the same time continuing best practice standards in meeting the healthcare needs of our community?” Throughout this paper, the authors will refer to business in the context of acumen, which is defined as a combination of knowledge and skills (Elgood, 2012). While there are many differences and timeframes of change between health systems across the world, when noting the global research, the authors will consider healthcare system consistencies within the Australian context, such as healthcare service delivery, clinical outcomes, budget limitations and the role of the nurse leader.

The health system is a complex industry with many moving parts (Uhl-Bien, Meyer, & Smith, 2020). Understanding the business of healthcare and perspective at a systems level (system thinking) can be important to consider. Frequently, a clinician has a good idea regarding improving service delivery, writes a business case, but then fails to receive a green light to proceed (Malloch & Porter-O'Grady, 1999). The clinician often relies on business case templates, without understanding the full context of the business information required (Sherman, 2020). This can then fall short of including all the relevant details to support the decision-making process, leading to a negative outcome without the clinician understanding as to why, demonstrating a highly inefficient process (Malloch & Porter-O'Grady, 1999; Tally, Thorgrimson & Robinson, 2013).

Nursing at all levels has a history of not adequately representing the business detail, subsequently failing to get all business cases across the line in the first instance (Tally et al. 2013). Experienced nurse leaders are not immune to this scenario either. While a leader's understanding of the budgetary process is substantially greater than the frontline clinician, there are still some finer business elements a nurse leader may have a limited grasp on, based on their experience and exposure, such as activity revenue (Davidson, Elliott & Daly, 2006). In Australia, a large proportion of our public health system is funded through the delivery of health activity, known as activity-based funding, or ABF (IHPA, 2021). “Fee for service” around health activity, is also one of the foundations of Medicare and private health insurance funding models (Australian Government, 2019). Most of these funding mechanisms, however, do not directly relate to nursing and therefore can be easily misunderstood or underestimated (Davidson et al., 2006). A knowledge of funding mechanisms would empower nurse leaders to better influence the delivery of quality health services.

The environment of healthcare can be described as less than ideal when it comes to understanding a rational approach to economic decision-making (Altman, 2012). While clinical outcomes and person-centred care is always the priority, economic decision-making can be positively or negatively influenced by emotion and intuition of what may be best for the consumer, sometimes leading to mental short cuts and cognitive biases (Altman, 2012). Having knowledge and a clearer understanding of this, however, through a consistent level of business acumen, can only empower nurse leaders to positively contribute to system level decision-making in the healthcare environment (Altman, 2012). Authentically balancing leadership priorities between the competing paradigms of caring and economics, is symbolic of today's changing and challenging healthcare landscape (Keselman & Saxe-Braithwaite, 2020).

Nursing is known as a profession with strengths related to quality, safety, care and compassion (Burston, Chaboyer & Gillespie, 2014; Roche, Duffield, Dimitrelis, & Frew, 2015; Shamian & Ellen, 2016). Business acumen however, only appears to be a strength of some (Graham, Fielding, Rooke, & Keen, 2006; Kang et al., 2012; Waxman & Massarweh, 2018), leading to a question of whether this skillset is an opportunity for the profession to explore more broadly, as we continue to evolve our value as leaders across our health system into the future. Nursing has often been a profession of the health industry, perceived as only supporting other health professionals (Porter-O'Grady, 1999; Shamian & Ellen, 2016). Therefore, any broader value of nursing has not always been well understood or represented (Malloch & Porter-O'Grady, 1999; Shamian & Ellen, 2016). However, despite increasing mechanisms for nursing roles to independently deliver activity and attract revenue, nursing has continued to undersell its full potential in the health system, due to having a limited grasp of representing business principles (Rutherford, 2012; Waxman & Massarweh, 2018). Tapping into recurrent funding streams for own-source revenue through activity is one example of opportunity that is relatively foreign for nursing in general, compared with traditional block funding allocations in Australia (Davidson et al., 2006). Activity and revenue for example, are two key metrics of the health system, that would be highly valuable for today's nurse leader to better understand.

Health systems deliver clinical services for the community. Historically, nurses and other clinician leaders have led teams in the delivery of these services, with many other parts of the organisation being run independently at times by non-clinical staff (Longmore, 2017). With a shortage of adequately prepared nurse leaders with a moderate degree of business acumen, Mahoney (2001) noted in the United States (US) that there was a risk of non-nurses filling nurse administrator roles, potentially diminishing the nursing voice. Over the last two decades however, this risk has not reduced globally, and is an opportunity for nurse leaders in Australia to become increasingly relevant as we reform into the future (Roche et al., 2015).

A review of the literature on nursing leadership, management, and business skills indicates the following descriptions. Leadership is defined as a series of qualities from competence, confidence, creativity and courage, in order to carry out functions such as advocacy, inspiration, guidance and empowerment, to build self-esteem, trust, as well as drive vision and influence positive outcomes (Heuston & Wolf, 2011; Mahoney, 2001; Negandhi et al., 2015; Thomas et al., 2008). Management, in the context of a healthcare leader, is defined as administrative tasks related to overseeing staff, budgets and patient care (Roche et al., 2015). While leadership is a series of qualities and management is a series of learned transactional skills related to managers, business is applying a financial and economic lens over this, as well as understanding the running and performance of a complete organisation (Mahoney, 2001). From the literature, the authors understand management be described as “unit (level) leadership,” and propose business being expressed as “system (level) leadership.” It is with a business lens, that the value of a system level of understanding is clearer. These broad terms are noted in Table 1 .

Table 1.

leadership, management and business skills (glossary at end of paper).

| Leadership skills | Management skills | Business skills |

|---|---|---|

| AdvocacyInspirationEmpowermentInfluenceVision | Human resourcesBudgetsQuality/outcomes(Unit leadership) | Finance/economicsPerformanceOrganisation(System leadership) |

A published example of a nursing leader role that demonstrates inconsistent preparedness of the above knowledge in balance is the nurse manager (Roche et al., 2015). A nurse manager is pivotal in influencing a positive clinical environment, effectively managing change, culture, attitude and direction of staff delivering healthcare (Mathena, 2002; Sherman, Bishop, Eggenberger, & Karden, 2007). While an essential role, many nurse managers do not commence with formal leadership or management skills, qualifications or knowledge for success (Contino, 2004; Patrician, Oliver, Miltner, Dawson, & Ladner, 2012; Roche et al., 2015). Often chosen as an excellent clinical nurse with seniority, a skill deficit is immediately present, leading to often rapid, “on the job” training of transactional activities and forced learning by osmosis, which in most cases leads to a competent transactional leader, but often limits the nurse manager to think and act at the system level (Roche et al., 2015; Sanford, 2011). What this rapid training in management and leadership does is often impede the full effectiveness of the nurse manager to actively grow as a transformational leader of their unit in the short term, as well as limit their longer term understanding of, and contribution to, the business of the wider organisation and system (Roche et al., 2015). Learning lessons from critical roles such as the nurse manager could better prepare our future nurse leaders.

Broad leadership and management skills, including business acumen, can evolve through experience, as well as be learned via formal educational pathways through various university and healthcare organisation programs (Curtis, Sheerin, & de Vries, 2011). Nurses, however, typically do not have consistent access to adequate training on the full domains of business and finance, despite often being responsible for budgets (Waxman & Massarweh, 2018). For example, financial practices can be limited to being given a set budget to work within, without understanding the full mechanics of how a budget is determined (Roche et al., 2015). Having appropriate educational preparedness that increases consistent business acumen for nursing leadership roles can enhance professionalism, as well as positively influence the clinical environment and wider organisational clinical and financial outcomes through enhancing a workforce culture of empowerment (Abraham, 2011; Cummings et al., 2008). The literature points towards business acumen (often referred to as business management skills) being essential, yet it appears to be a distinct skillset less focused on in nursing leadership development (Graham et al., 2006; Kang et al., 2012; Waxman & Massarweh, 2018). Furthermore, there appears to be a gap in the research of the impact of this lesser focus on business in nursing across the years, as well as what a minimum standard of business acumen would be (Abraham 2011; Mahoney, 2001; Roche et al., 2015; Waxman & Massarweh, 2018). Further research investigating the value of business acumen as part of nursing leadership is vital to continually evolve our input into future health systems.

2. Discussion

Brown (1983, p. 52) in the US, set the scene of this discussion globally, by asking “what is business savvy?.” She highlighted the importance of nurses requiring socialisation to the corporate culture, that the qualifications required for tomorrow's nurses will be different from today's, and that working with a limited health dollar would demand changes to the educational preparedness of nurses (Brown, 1983). Since then, other international perspectives have included Graham et al., (2006) in the UK, noting weaknesses of nursing management being political acumen and professional business management (Graham et al., 2006). While in Taiwan, Kang (2012) found nursing administrators self-rated themselves as high on integrity but low on financial and business acumen skills (Kang et al., 2012). There are limited publications found on this in the Australian context, possibly reflecting the pace and impetus of international trends on this part of leadership.

Flowing on from Brown's initial work, Sanford (2011) drove the case for nursing leadership development being a collaboration between chief financial and chief nursing officers in developing nursing leaders in the US. While Rishel (2014) went one step further, proposing all nursing levels need business knowledge, not just leaders, noting the imperative of floor nurses having awareness of not only positive clinical patient outcomes, but the financial implications of various chemotherapy agents on maintaining a hospital's solvency (Rishel, 2014). In 2018, Waxman noted a broader recognition of business competence in leadership, with the six key healthcare administrator agencies in the US developing five core competencies for healthcare leaders that included business acumen as one of them (Waxman & Massarweh, 2018). As our local profession evolves leadership capacity, it can be argued these competencies would have high relevance for the Australian context as well.

In addition to the technical skills of nursing, nurse leaders develop strengths in leadership and learn transactional skills in management throughout their careers (Mahoney, 2001). However, the ever-growing importance for all clinician leaders to understand a greater depth of how a health organisation runs highlights business acumen as potentially becoming more essential across clinical professions (Waxman & Massarweh, 2018). Notwithstanding the evidence, a focus of business acumen is still lacking from most learning pathways and programs (Curtis et al., 2011; Fuster Linares et al., 2020). It can be argued that business is a subset of both leadership and management, but neither adequately cover the finer details of an organisational or systems level perspective. While nursing has strengths in leadership and management, business acumen may be a focused skillset of value for the profession to consider as we continually advance into the future, with business evolving as an essential skill for contributing to healthcare reform (Bamford-Wade & Moss, 2010; Davidson et al., 2006; Waxman & Massarweh, 2018). This is demonstrated in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

(Original concept by authors) – nursing technical skills, leadership, management, and business skills.

Modern nurse leaders need to be consistently skilled and recognised as business savvy and need a broad view of the healthcare system (Mahoney, 2001; Waxman & Messarweh, 2018). In a global survey by Roche et al., (2015), limited exposure to hospital affairs as a nurse leader was one of the main factors that influenced a nurse manager's decision to leave a role. The increasing complexity of the system, without adequate training or inclusion, has also been noted as a factor of increasing nurse leader burnout (Uhl-Bien et al., 2020). Understanding the business side of healthcare can positively impact the bottom line of an organisation and is essential in today's changing healthcare environment (Dudzic, 2021; Sanford, 2011; Thomas, Seifert, & Joyner, 2016). Nurse leaders are ideally placed to balance the clinical context and business demands of today's financially challenged healthcare system and reform efforts (Kesselman & Saxe-Braithwaite, 2020; Pierce, 2016). As we move into a new phase of health system management in Australia post-pandemic and through ongoing system modernisation, nurse leaders need to be at the forefront of reform and should have optimised knowledge and acumen to positively influence change.

Along with nursing leaders, further to Rishel's views in 2014, it can be argued that foundational business competence is of value to all clinicians at all levels (nursing/midwifery, allied health, medicine), to deliver care most effectively in today's health system, from understanding everyone's roles in performance through to cost effectiveness. Nurses at all levels could benefit from having leadership skills (Dyess & Sherman, 2011; Vance & Luis, 2020). While new graduate nurses are considered somewhat bedside leaders (Al-Dossary, Kitsantas, & Maddox, 2014), all levels of nursing could benefit from skills that enable better understanding of the bigger picture where an institution's survival is based on core business principles (Fletchall-Wilmes, 2019). With healthcare becoming more corporate, nurses in the future will need to be more business savvy to understand the decision-making process, which underpins the delivery of clinical services (Castledine, 2006).

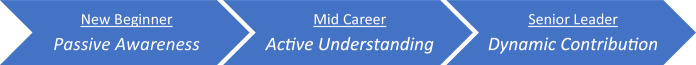

“Knowledge is power” (Mahoney, 2001, p. 270). Embedding leadership education to include foundational business principles across nursing degree programs as a norm of practise for all nurses, not just designated leaders, will develop essential skills and baseline awareness of business, increase leadership capacity across the profession and best prepare our nurses for the future (Curtis et al., 2011; Fuster Linares et al., 2020; Negandhi et al., 2015; Scott & Miles, 2013; Thew, 2020). In conjunction with traditional nursing values, this would encourage the growth of business acumen in nursing from passive awareness as a new graduate, through to active understanding and dynamic contribution later in one's nursing career as demonstrated in Fig. 2 .

Fig. 2.

(Original concept by authors) – growth of business acumen.

These foundation skills are proposed to enhance the long-term ability of nursing to lead and drive innovative health, reform and best practice, delivering sustainable healthcare where it counts.

3. Conclusion

Nursing leadership development is not a new concept in Australia nor around the world. However, over the past couple of decades and more recently through reform, there has been limited specific commentary about the need for nursing leaders to be more business savvy, able to adapt to today's healthcare environment, as well as focused efforts to enhance this skillset for nursing in Australia. The Australian healthcare system is at a point where major change is underway to reform and modernise, thus delivering more efficient and effective services for the community and the health system that is sustainable into the future.

Nurse leaders and all clinician leaders, in being able to lead and drive innovation and reform, would benefit from having a good and consistent understanding of all the moving parts of the system. Understanding the big picture in addition to clinical expertise, would promote positive effort and collaborative dialogue for successful transformation of the health system to occur. With an increased focus on the business side of healthcare, the strength and value of nursing's contribution and influence, can only be enhanced with a consistent approach to business acumen across the profession, in addition to the traditional values of nursing. By representing the business detail in addition to caring, our profession could position ourselves to be acknowledged with greater potential than what may be traditionally understood, opening up new opportunities for nursing at the system level. It is believed that business acumen is therefore essential for advancing nursing and health service delivery in Australia.

Furthermore, with the future direction of healthcare in Australia, there is a strong case for foundational business skills to be a fundamental competency of all clinicians at all levels. In nursing for example, this could likely enhance our profession's input on quality and safety, as well as perspective of promoting the person-centredness of healthcare. The inclusion of core business concepts that underpin our health system as part of the undergraduate curriculum, could be an effective method of delivering this knowledge, with continuous training also a vital part of future reform.

4. Recommendations

Overseas literature highlights business acumen as an essential skillset for nurse leaders to understand and contribute to the broader system (Graham et al., 2006; Kang et al., 2012; Shamian & Ellen, 2016; Thew, 2020; Waxman & Massarweh, 2018). While in Australia, although transactional leadership and management development are somewhat described (Roche et al., 2015), there is little acknowledgement of specific business acumen for nurses. There would be substantial value in understanding what the literature identifies as skills of business acumen, what these skills look like in nursing in conjunction with traditional values, and what needs to change in structure and culture of health organisations, to recognise and enhance these skills and therefore business acumen across the profession, without being a competing paradigm for nursing?

Along with reviewing the literature, current global bodies of knowledge on the skills of business acumen for clinicians need to be explored further in the Australian context. Further to this, exploring the skills, education and aspirations of our Australian healthcare workforce, as well as input from prominent healthcare leaders and other non-clinical stakeholders, could identify a focused collection of foundation skills of business acumen that will inform policy and curriculum in the future.

Recognising the value of business acumen for nursing leaders (with potential relevance to all clinician leaders), will enable a better understanding of non-clinical knowledge gaps that may form part of a future foundation skill-base, in addition to traditional clinical values, to best prepare our future clinicians to influence the evolution of our future healthcare system in Australia and globally.

Glossary

| Term | Definition | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Business acumen | An element of leadership, includes skills of financial literacy, knowledge of organisation and ability to take a ‘big picture’ view of the business. | Retrieved from www.chris-elgood.com/business-acumen-definition/ |

| Entrepreneurship | The capacity and willingness to develop, organise and management a business venture along with any of its risks in order to make a profit. | Retrieved from www.businessdictionary.com/definition/entrepreneurship.html |

| Leadership | A series of skills that set direction and drive a vision, by motivating and inspiring individuals and teams. | Retrieved from https://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/newldr_41.htm |

| Management | Administrative process of planning, organising, staffing, budgeting, leading and controlling a team. | Retrieved from www.iedunote.com/management |

| System (healthcare) | The method by which a service (healthcare) is financed, organised and delivered to a target group or population. | Retrieved from https://www.encyclopedia.com/science/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/healthcare-systems |

Acknowledgments

Authorship contribution statement

The paper properly credits the meaningful contributions of co-authors and co-researchers.

Funding

No funding was received to support the development of this paper.

Ethical statement

An ethical statement is not applicable as this publication did not involve human or animal research as it is a discussion paper.

Conflict of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

Jasna Romic and Sarah Thorning of Gold Coast Health Library Services for assisting with this background review.

References

- Abraham P.J. Developing nurse leaders: a program enhancing staff nurse leadership skills and professionalism. Nursing administration quarterly. 2011;35(4):306–312. doi: 10.1097/NAQ.0b013e31822ecc6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Dossary R., Kitsantas P., Maddox P.J. The impact of residency programs on new nurse graduates' clinical decision-making and leadership skills: A systematic review. Nurse education today. 2014;34(6):1024–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman M. Implications of behavioural economics for financial literacy and public policy. The Journal of socio-economics. 2012;41(5):677–690. doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2012.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bamford-Wade A., Moss C. Transformational leadership and shared governance: an action study. Journal of nursing management. 2010;18(7):815–821. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown B.S. What is business savvy? Nursing Economics. 1983;1(1):52–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burston S., Chaboyer W., Gillespie B. Nurse-sensitive indicators suitable to reflect nursing care quality: a review and discussion of issues. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2014;23(13-14):1785–1795. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castledine G. The business habits of highly effective nurses. British Journal Of Nursing. 2006;15(20):1143. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2006.15.20.22301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contino D.S. Leadership competencies: knowledge, skills, and aptitudes nurses need to lead organizations effectively. Critical care nurse. 2004;24(3):52–64. doi: 10.4037/ccn2004.24.3.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings G., Lee H., MacGregor T., Davey M., Wong C., Paul L., Stafford E. Factors contributing to nursing leadership: a systematic review. Journal of health services research & policy. 2008;13(4):240–248. doi: 10.1258/jhsrp.2008.007154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis E.A., Sheerin F.K., de Vries J. Developing leadership in nursing: the impact of education and training. British Journal Of Nursing. 2011;20(6):344–352. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2011.20.6.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson P.M., Elliott D., Daly J. Clinical leadership in contemporary clinical practice: implications for nursing in Australia. Journal of Nursing Management. 2006;14:180–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2934.2006.00555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudzic M. Healthcare reform in a post-pandemic world. New Labor Forum. 2021 doi: 10.1177/10957960211007128. https://doi.org/ [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dyess S., Sherman R. Developing the leadership skills of new graduates to influence practice environments: a novice nurse leadership program. Nursing administration quarterly. 2011;35(4):313–322. doi: 10.1097/NAQ.0b013e31822ed1d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgood, C. (2012). "Business Acumen Definition: Who Needs it and Why." Availale from https://www.chris-elgood.com/business-acumen-definition/, Accesed 28th February 2021.

- Fletchall-Wilmes, M. A. (2019). Financial acumen for nursing: The great game. Paper presented at the Creating healthy work environments conference, Louisiana. Availale from https://sigma.nursingrepository.org/handle/10755/16729

- Fuster Linares P., Rodriguez Higueras E., Martin-Ferreres M.L., Cerezuela Torre M.Á., Wennberg Capellades L., Gallart Fernández-Puebla A. Dimensions of leadership in undergraduate nursing students. Validation of a tool. Nurse education today. 2020;95 doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104576. 104576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham I., Fielding C., Rooke D., Keen S. Practice development ‘without walls’ and the quandary of corporate practice. Journal of clinical nursing. 2006;15(8):980–988. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuston M.M., Wolf G.A. Transformational leadership skills of successful nurse managers. The Journal of nursing administration. 2011;41(6):248–251. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e31821c4620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang C.M., Chiu H.T., Hu Y.C., Chen H.L., Lee P.H., Chang W.Y. Comparisons of self-ratings on managerial competencies, research capability, time management, executive power, workload and work stress among nurse administrators. Journal of nursing management. 2012;20(7):938–947. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2012.01383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keselman D., Saxe-Braithwaite M. Authentic and ethical leadership during a crisis. Healthcare Management Forum. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0840470420973051. https://doi.org/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longmore M. Nursing leadership being eroded. Kai Tiaki Nursing New Zealand. 2017;23(6):28–29. [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney J. Leadership skills for the 21st century. Journal of nursing management. 2001;9(5):269–271. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2834.2001.00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malloch K., Porter-O'Grady T. Partnership economics: nursing's challenge in the quantum age. Nursing Economics. 1999;17(6):299–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathena K.A. Nursing manager leadership skills. The Journal of nursing administration. 2002;32(3):136–142. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200203000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negandhi P., Negandhi H., Tiwari R., Sharma K., Zodpey S.P., Quazi Z., et al. Building interdisciplinary leadership skills among health practitioners in the twenty-first century: An innovative training model. Frontiers in public health. 2015;3 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2015.00221. 221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrician P.A., Oliver D., Miltner R.S., Dawson M., Ladner K.A. Nurturing charge nurses for future leadership roles. The Journal of nursing administration. 2012;42(10):461–466. doi: 10.1097/NNA.0b013e31826a1fdb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce B.R. Speaking up: It requires leadership maturity. Nurse leader. 2016;14(6):413–418. doi: 10.1016/j.mnl.2016.08.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rishel C.J. Financial savvy: the value of business acumen in oncology nursing. Oncology nursing forum. 2014;41(3):324–326. doi: 10.1188/14.ONF.324-326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche M., Duffield C., Dimitrelis S., Frew B. Leadership skills for nursing unit managers to decrease intention to leave. Nursing: research and reviews (Auckland, N.Z.) 2015;5:57–64. doi: 10.2147/NRR.S46155. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford M.M. Nursing is the room rate. Nursing Economics. 2012;30(4):193–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanford K.D. The case for nursing leadership development: leadership development for nurses can have a positive impact on an organization’s bottom line, particularly in light of future financial challenges. Healthcare financial management. 2011;65(3):104–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott E.S., Miles J. Advancing leadership capacity in nursing. Nursing administration quarterly. 2013;37(1):77–82. doi: 10.1097/NAQ.0b013e3182751998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman R.O., Bishop M., Eggenberger T., Karden R. Development of a leadership competency model. The Journal of nursing administration. 2007;37(2):85–94. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200702000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamian J., Ellen M.E. The role of nurses and nurse leaders on realising the clinical, social and economic return on investment of nursing care. Healthcare Management Forum. 2016;29(3):99–103. doi: 10.1177/0840470416629163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman R.O. Learn to manage yourself. American Journal of Nursing. 2020;120(2):68–71. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000654348.26954.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tally L.B., Thorgrimson D.H., Robinson N.C. Financial literacy as an essential element in nursing management practice. Nursing Economics. 2013;31(2):77–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thew J. Nurses rise to new levels in the c-suite. HealthLeaders (San Francisco, Calif.) 2020;23(2):6–18. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J., Collins A., Collins D., Herrin D., Dafferner D., Gabriel J. The language of business: a key nurse executive competency. Nursing Economics. 2008;26(2):122–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas T.W., Seifert P.C., Joyner J.C. Registered nurses leading innovative changes. Online journal of issues in nursing. 2016;21(3):3. doi: 10.3912/OJIN.Vol21No03Man03. 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhl-Bien M., Meyer D., Smith J. Complexity leadership in the nursing context. Nursing administration quarterly. 2020;44(2):109–116. doi: 10.1097/NAQ.0000000000000407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vance C., Luis C. A pandemic crisis: Mentoring, leadership, and the millennial nurse. Nursing Economics. 2020;38(3):152. [Google Scholar]

- Waxman K.T., Massarweh L.J. Talking the talk: financial skills for nurse leaders. Nurse leader. 2018;16(2):101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.mnl.2017.12.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- IHPA (2021). Activity based funding. Available from: https://www.ihpa.gov.au/what-we-do/activity-based-funding, Accesed 28th February 2021.

- Australian Government (2019). The Australian health system. Available from https://www.health.gov.au/about-us/the-australian-health-system. Accesed 28 February 2021.

- WHO. (2019). Universal health coverage. Avaialble from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/universal-health-coverage-(uhc), Accesed 28th February 2021.