PURPOSE

After risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO), BRCA1/2 pathogenic variant (PV) carriers have a residual risk to develop peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC). The etiology of PC is not yet clarified, but may be related to serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma (STIC), the postulated origin for high-grade serous cancer. In this systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis, we investigate the risk of PC in women with and without STIC at RRSO.

METHODS

Unpublished data from three centers were supplemented by studies identified in a systematic review of EMBASE, MEDLINE, and the Cochrane library describing women with a BRCA-PV with and without STIC at RRSO until September 2020. Primary outcome was the hazard ratio for the risk of PC between BRCA-PV carriers with and without STIC at RRSO, and the corresponding 5- and 10-year risks. Primary analysis was based on a one-stage Cox proportional-hazards regression with a frailty term for study.

RESULTS

From 17 studies, individual patient data were available for 3,121 women, of whom 115 had a STIC at RRSO. The estimated hazard ratio to develop PC during follow-up in women with STIC was 33.9 (95% CI, 15.6 to 73.9), P < .001) compared with women without STIC. For women with STIC, the five- and ten-year risks to develop PC were 10.5% (95% CI, 6.2 to 17.2) and 27.5% (95% CI, 15.6 to 43.9), respectively, whereas the corresponding risks were 0.3% (95% CI, 0.2 to 0.6) and 0.9% (95% CI, 0.6 to 1.4) for women without STIC at RRSO.

CONCLUSION

BRCA-PV carriers with STIC at RRSO have a strongly increased risk to develop PC which increases over time, although current data are limited by small numbers of events.

INTRODUCTION

Epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC) is the most lethal gynecologic cancer with a 5-year survival rate of 47%.1 Women in the general population have a lifetime risk of 1.3% to develop EOC, but this risk is, on average, 44% (95% CI, 36 to 53) for women with a BRCA1 and 17% (95% CI, 11 to 25) for women with a BRCA2 pathogenic variant (PV) up to age 80 years.2 Surveillance with ultrasound and/or cancer antigen 125 showed to be ineffective in the early diagnosis of EOC for normal-risk postmenopausal women,3-7 although less data are available for younger high-risk women.8 Timely risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO) is the most effective method of prevention, reducing EOC risk up to 96%.9-11 To optimize risk-reduction, BRCA1/2-PV carriers are advised to undergo RRSO at the age of 35-40 and 40-45 years, respectively.12-14 Despite the significant risk-reduction, a risk of developing peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC) persists. For BRCA1-PV and BRCA2-PV carriers, the estimated cumulative risk to develop PC during the 20 years after RRSO is 3.9% and 1.9%, respectively.10 Currently, it is unclear which patients are most at risk to develop PC after RRSO.

CONTEXT

Key Objective

Women with a BRCA1/2 pathogenic variant undergo a risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO) to minimize their ovarian cancer risk. Despite this surgery, a minority develops peritoneal carcinomatosis (PC). We investigated the risk of PC in women with and without a serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma (STIC) at RRSO. We present the largest meta-analysis thus far with individual patient data of 3,121 women of whom 115 were with STIC.

Knowledge Generated

Women with isolated STIC at RRSO are at increased risk to develop PC compared with women without STIC (hazard ratio, 33.9; 95% CI, 15.6 to 73.9; P < .001). The 5- and 10-year risks of PC are, respectively, 10.5% and 27.5% for women with STIC versus 0.3% and 0.9% for women without STIC.

Relevance

Women undergoing RRSO should be informed about these risks, and future research should focus on prospective data collection on STICs, the etiology of PC, and clinical management after STIC diagnosis.

PC was thought to derive from the pelvic peritoneum as secondary Müllerian system. However, signs for a fallopian tube origin of PC accumulated as the focus on the fallopian tube epithelium expanded after the suggestion of the noninvasive serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma (STIC) as precursor for high-grade serous carcinoma.15,16 In the study by Harmsen et al,17 including women with PC after RRSO, STIC was found in the original RRSO tissue in around 60%. As STIC is found in approximately 3% of BRCA-PV carriers at RRSO, the finding by Harmsen et al is notably higher than expected, which suggests an association between STIC and PC later on.17,18 Moreover, the same TP53 mutation was identified in PC and STIC from the same patient,19 suggesting that an isolated STIC at RRSO increases the risk for developing PC. As STIC lesions are rather rare, only small series describing the follow-up of BRCA-PV carriers with STIC have been published.20,21 To elucidate the risk of PC for BRCA-PV carriers with a STIC at RRSO, we present a systematic review and Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis (IPDMA). IPDMA is especially useful when analyzing time-to-event outcomes such as the risk of PC, as hazard ratios (HRs) and risk predictions can be calculated independent to trial reporting. Furthermore, effect modifiers (intervention-covariate interactions) can be directly assessed.22 In this manuscript, we use the term STIC, as it is highly recognized by the medical community. These lesions are alternatively described as fallopian tube intraepithelial neoplasia or high-grade tubal intraepithelial lesions, to specifically denote noninvasive lesions.23

METHODS

The study protocol was submitted at the PROSPERO database (CRD42020157451). The article was written conforming with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement on reporting an IPDMA.24 First, unpublished patient data were collected from three hospitals. Second, a systematic review was performed to identify eligible studies and to collect individual patient data (IPD), or, if unavailable, aggregated data.

Data Collection Part 1: Cohort Study (unpublished data)

We performed a retrospective cohort study in three hospitals: (1) Kaiser Permanente in San Francisco, CA, (2) MD Anderson in Houston, TX, and (3) Radboud University Medical Center in Nijmegen, the Netherlands. The medical ethics committee of Arnhem-Nijmegen (registration number 2018-4462) provided approval. All women with a confirmed BRCA1/2-PV who underwent RRSO between January 2007 and September 2019 (hospital one), 2007 and 2019 (hospital two), and January 1996 and November 2018 (hospital three) were identified. Aberrant P53 and Ki-67 expression was supportive in case of unclear morphology to diagnose STIC. The histopathologic characteristics were extracted from pathology reports, using a standardized form. All tissue slides from hospital three were revised by a gynecologic pathologist to complete the description of histopathologic characteristics.

Data Collection Part 2: Systematic Review (published data)

A search strategy was built to search EMBASE, MEDLINE, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; Data Supplement, online only). Included studies were case-control, cohort, or population-based, reported the occurrence of PC during follow-up of women with a BRCA-PV after RRSO, and assessed the ovaries and fallopian tubes on the presence of carcinoma and STIC. The identified studies were screened on title/abstract and subsequently on full-text, both independently by two authors. Inconsistencies were resolved by discussion and consulting a third author. Data of the included studies were extracted on a data-extraction form (Data Supplement). Studies were independently assessed on risk of bias by two authors (M.P.S. and J. Bogaerts), using a predefined quality assessment tool for observational cohort studies.25 Item 7 (“Was the time frame sufficient so that one could reasonably expect to see an association between exposure and outcome if it existed?”) was scored as low risk of bias when the median time frame was 60 months between RRSO and PC, as the median time to PC was 42-55 months in earlier studies.17,20 The corresponding author of each individual study was contacted by e-mail minimally twice to request IPD on a standardized case report form (Data Supplement).

Outcome Measures

The primary aim was to estimate the HR for the risk of PC during follow-up between BRCA-PV carriers with and without STIC at RRSO and the 5- and 10-year risks of PC after RRSO for these women. Additional analyses were performed to investigate the risk in women per BRCA-PV type (BRCA1 v BRCA2), for age at RRSO, with and without additional staging surgery and/or postoperative chemotherapy.

Statistical Analysis

The primary analysis was based on IPD using a one-stage Cox proportional-hazards regression with a frailty term (random intercept) for study. First, the distribution of PCs was evaluated with Kaplan-Meier plots stratified by STIC and BRCA-PV type. The amount of data beyond 10 years after RRSO appeared scarce; therefore, analyses were performed up and until 10 years after RRSO. There is evidence that the incidence of PC differs depending on age at RRSO and type of BRCA-PV.10,17 Recency of RRSO might also play a role, as in recent years, the STIC detection may have improved. Therefore, we considered these three parameters as potential confounders. To investigate whether the results are not affected by these potential confounders, we used mixed logistic regression models with a random intercept for study to investigate the association between the potential confounders and the incidence of STICs. If associated, we evaluated whether they also were associated with PC risk in the Cox models.

To estimate PC risk at five and 10 years after RRSO, we used a parametric survival model on the basis of the Weibull distribution. Parametric models are convenient when absolute (rather than relative) risks for individual subjects (rather than for subpopulations) are of primary interest as they result in smooth predicted survival curves.22 A Weibull model stratified by study did not converge. Instead, we added a clustering term for the data from the same study, to have standard errors adjusted for the clustered design of the data. HRs of the Cox and the Weibull model were similar.

We used four data sets to evaluate PC risk after STIC at RRSO. Data set A included all studies with IPD and was used for the primary analysis. Data set B included only studies with complete IPD for both women with and without STIC, as in data set A, some studies had only IPD of women with STIC available, whereas IPD of women without STIC were missing. Data sets C and D were partly self-constructed: individual data were simulated from aggregated data to include also women for whom IPD were not available. Data of incident cases with STIC and PC were individually described and thus directly incorporated. Most aggregated data were from women without STIC and without PC. To simulate individual follow-up times, we used the reported follow-up in a normal distribution with as mean the log-transformed median and as standard deviation the (log-median minus log-minimum) follow-up divided by 2 (as the maximum follow-up was biased by censoring). The distribution of the simulated data was compared with the original aggregated data and fitted very well. Data set D was a subset of C, including only the studies that described both women with and without STIC at RRSO. Sensitivity analyses on data sets B, C, and D used the same models as the primary analysis (data set A).

Analyses were conducted with the statistical software R.26 The Data Supplement provides additional information on the used R packages.

Initially, we aimed to adjust for the clustering effect of studies by formulating a model stratified by (or with a frailty term for) study with a random effect for the interaction of STIC by study. However, because of the low number of PCs and STICs, these models did not converge and we used a fixed effect for STIC. To evaluate this, we conducted as sensitivity analysis a two-stage approach where per study the association of STIC with PC was estimated using a Cox model with Firth's penalized likelihood, followed by random-effects meta-analysis with an REML estimator for tau and the Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman approach.27

RESULTS

Study Selection

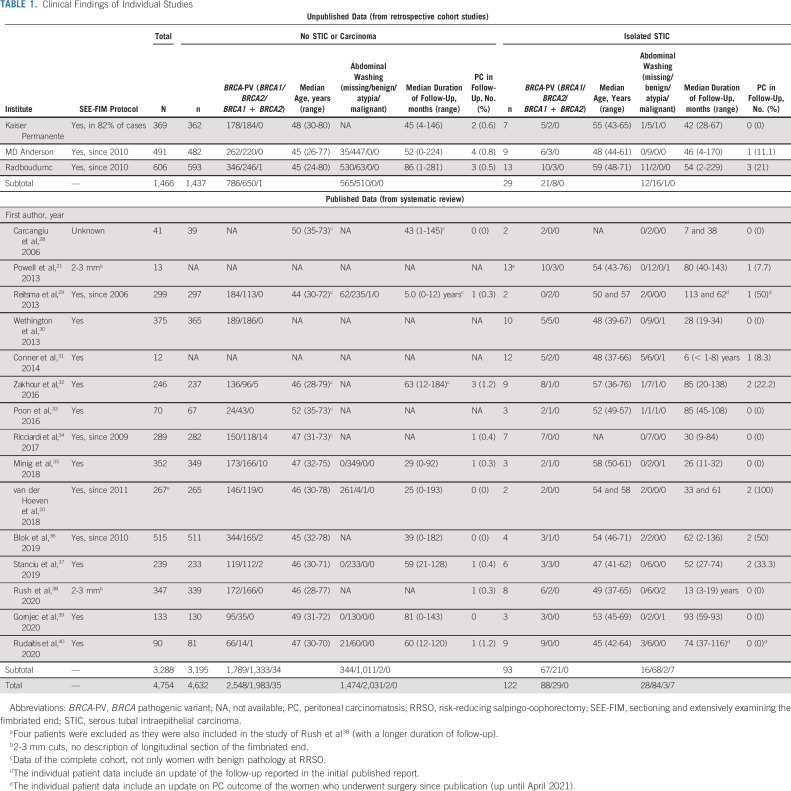

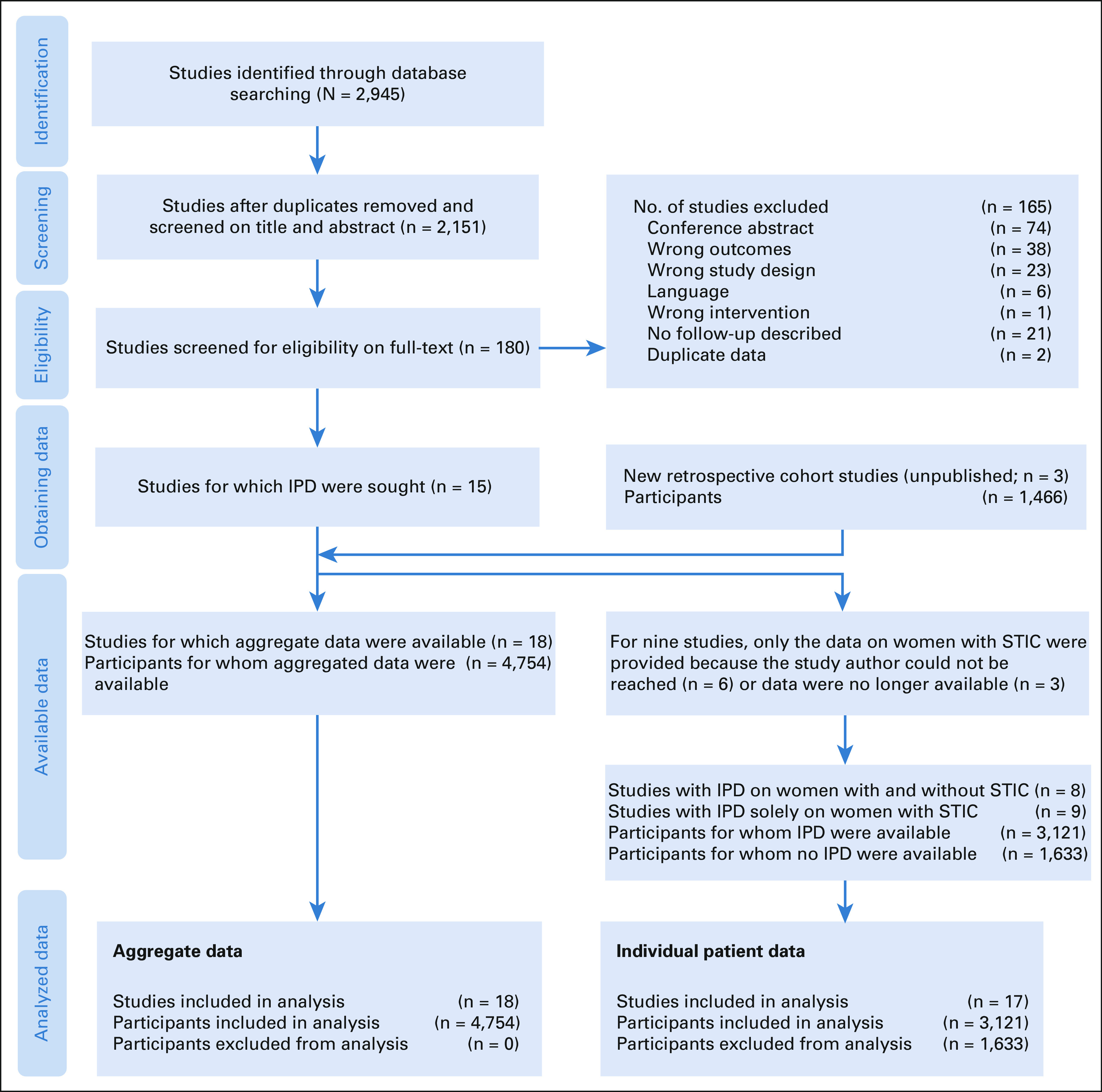

A total of 2,151 studies were identified. After title, abstract, and full-text screening, 15 studies with data of 3,288 women were included. The three unpublished retrospective cohort studies contained data of an additional 1,466 women. IPD was available for 3,121 women, of whom 115 had a STIC at RRSO. Aggregated data were available for 4,754 women, of whom 122 had a STIC at RRSO (Table 1 and Data Supplement). Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram.

TABLE 1.

Clinical Findings of Individual Studies

FIG 1.

PRISMA IPD flow diagram to illustrate the study selection process. IPD, individual patient data; STIC, serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma.

Risk-of-Bias Assessment

The Data Supplement provides the risk of bias assessment. Short duration of follow-up was the most frequent source for potential bias as this was present in seven of the 15 studies. There is little to no detection bias in the studies as shown in the Data Supplement.

Primary IPD Population

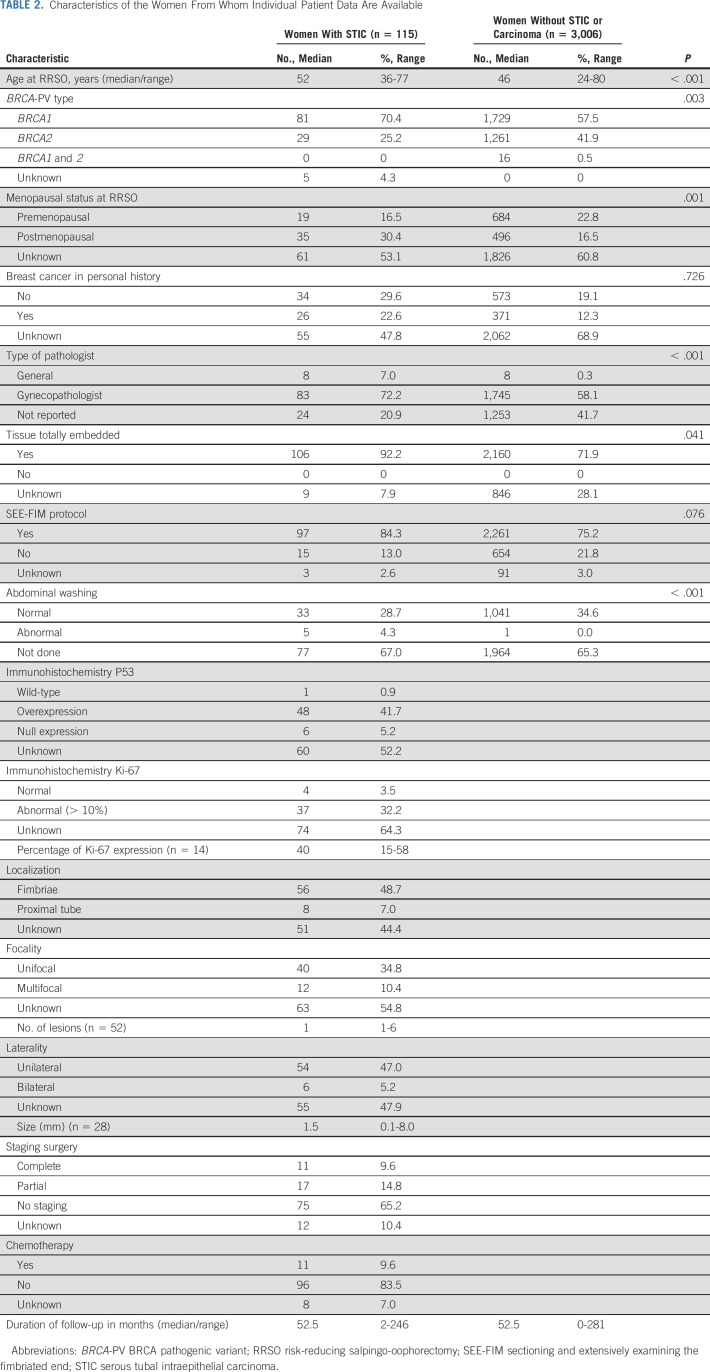

The characteristics of the women from whom IPD are available are described in Table 2. The 115 women with STIC had a median age (range) of 52 (36-77) years at RRSO and the 3,006 women without STIC a median age (range) of 46 (24-80) years (P < .001). Of the women with STIC, 70.4% harbored a BRCA1, 25.2% a BRCA2, zero a BRCA1 and 2-PV, and in 4.3% BRCA-PV type was unknown, whereas these percentages were, respectively, 57.5%, 41.9%, 0.5%, and 0% in women without STIC (P = .003). The tissue was embedded in conformity with the sectioning and extensively examining the fimbriated end (SEE-FIM) protocol in 86.8% of the women with STIC and in 77.2% without STIC (P = .076). The median (range) follow-up duration is 52.5 (2-246) months in women with STIC and 52.5 (0-281) months in women without STIC. In 55 women P53 expression was known, 48 women (87.3%) had P53 overexpression, six (10.9%) P53 null expression, and one (1.8%) a wild-type immunohistochemical profile. Ki-67 expression was normal in four out of 41 women (9.8%) with known outcome and abnormal in the other 37 women (90.2%). STIC was localized in the fimbriated end in 87.4%, unifocal in 77.0%, and unilateral in 90.0% of women from whom these data were available. The median (range) STIC size was 1.5 (0.1-8.0) mm.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of the Women From Whom Individual Patient Data Are Available

Primary Analysis

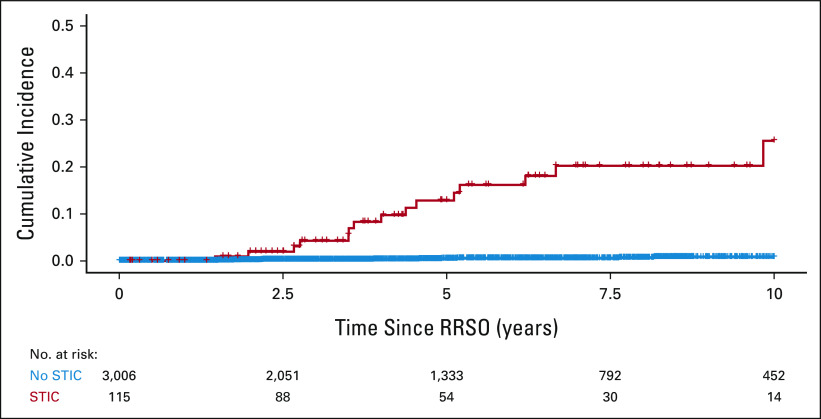

Fifteen (13%) of the 115 women with STIC at RRSO developed PC during a median (range) follow-up of 52.5 (2-246) months. Of the 3,006 women without identified STIC at RRSO, a total of 12 (0.4%) developed PC during 52.5 (0-281) months of follow-up, and 11 (0.4%) when restricting the follow-up period till 120 months after RRSO. The median (range) time from RRSO to PC was 48.0 (18-118) months for women with STIC and 50.8 (18-160) months for women without STIC at RRSO. No PCs occurred within 18 months after RRSO (Fig 2). The HR for the risk of developing PC during follow-up was 33.9 (95% CI, 15.6 to 73.9; P < .001) in case of STIC, compared with no STIC at RRSO.

FIG 2.

Kaplan-Meier plot to visualize the occurrence of peritoneal carcinomatosis after RRSO. RRSO, risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy, STIC, serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma.

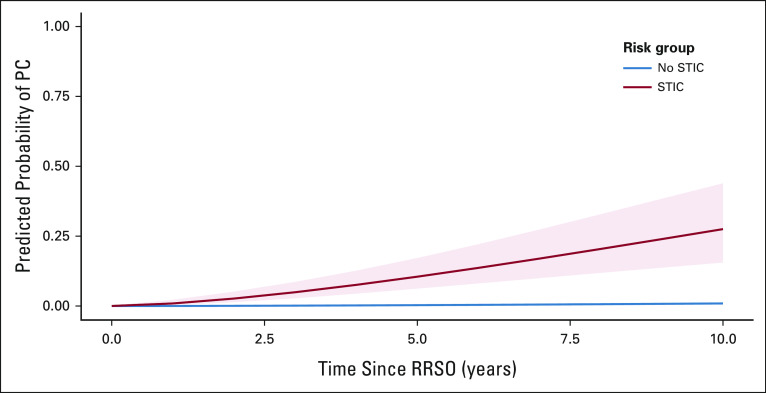

Predicted probabilities for PC for women with or without STIC at RRSO are presented in Figure 3. For women with STIC, the cumulative risk of PC after 5 years is 10.5% (95% CI, 6.2 to 17.2) and after 10 years is 27.5% (95% CI, 15.6 to 43.9). For women without STIC, these risks are 0.3% (95% CI, 0.2 to 0.6) and 0.9% (95% CI, 0.6 to 1.4), respectively.

FIG 3.

Predicted probability of PC after RRSO. PC, peritoneal carcinomatosis, RRSO, risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy, STIC serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma.

Secondary Analyses

We evaluated age at RRSO, BRCA-PV type, and recency of RRSO as potential confounders. Higher age at RRSO (P < .001) and BRCA1-PV type (P = .016) were positively associated with presence of STIC, whereas recency of RRSO was not (P = .980). Neither age nor BRCA1-PV was significantly associated with PC in a Cox model with STIC, age, and BRCA-PV type (P = .370 and P = .064, respectively). Neither were BRCA-PV type, age at RRSO, and recency of RRSO significant effect modifiers (P = .240, .730, and .800, respectively). An overview of these analyses is enclosed in the Data Supplement. Interaction between positive cytology and STIC could not be evaluated as only six cases had positive cytology.

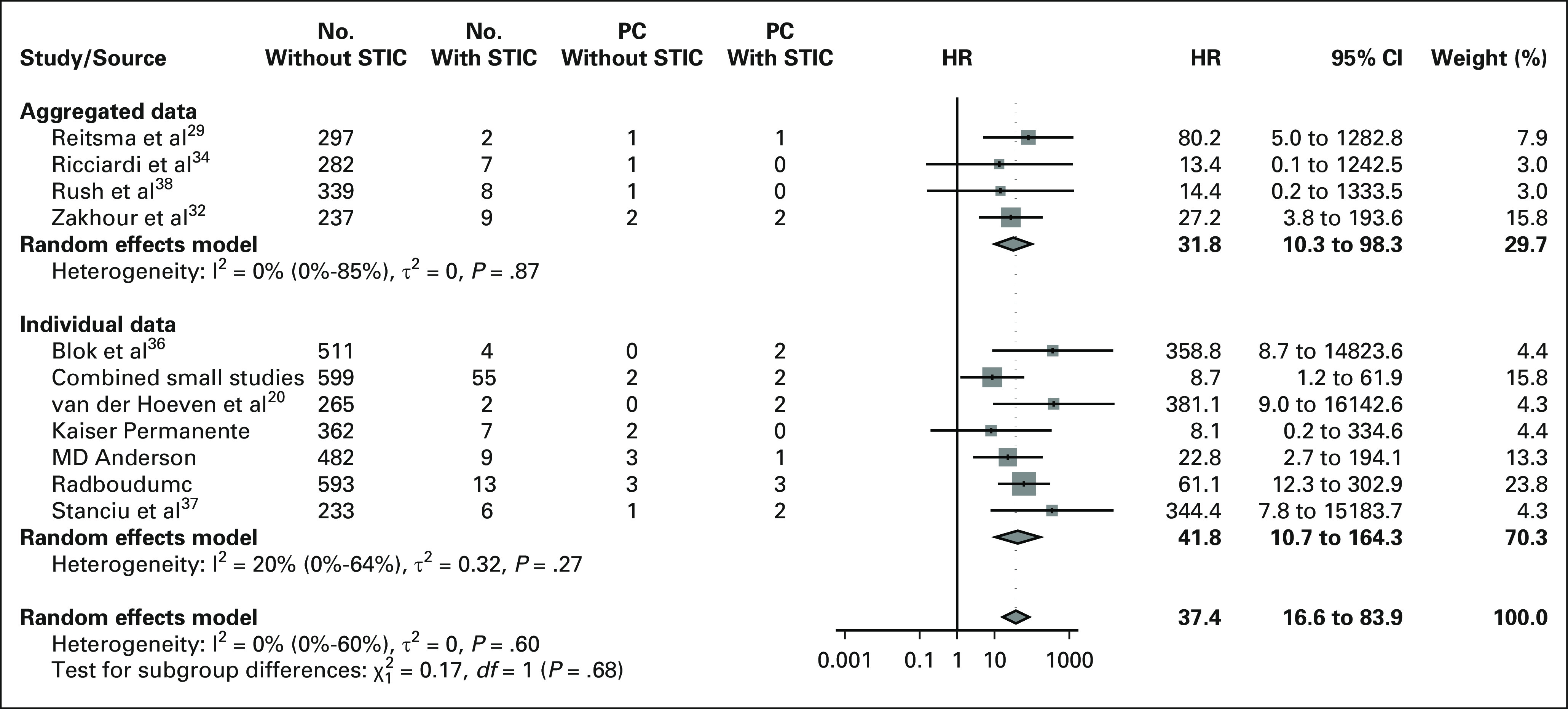

Kaplan-Meier plots, stratified by presence of STIC and BRCA-PV type, for all four data sets are presented in the Data Supplement. The results of the analyses in the other data sets were similar to the results of the primary analysis: the HR to develop PC for women with STIC in IPD from studies with both STIC classes (data set B, 17 studies) was 49.5 (95% CI, 21.0 to 116.8), in the combined IPD and aggregated data (data set C, 18 studies) 33.1 (95% CI, 6.4 to 67.1) and in the combined data from studies with both STIC classes (data set D, 14 studies) 41.5 (95% CI, 19.9 to 86.3). The results on confounding, effect modification, and risk prediction were also similar to those from the analyses of the primary data set. The two-stage analysis (to evaluate the effect of assuming a fixed effect for STIC) resulted in an HR of 37.4 (95% CI, 16.6 to 83.9; Fig 4). Differences between the results of aggregated and individual data were not significant (P = .678), and the heterogeneity between studies was low (maximum 20%).

FIG 4.

Forest plot to visualize the two-stage analysis. HR, hazard ratio; PC, peritoneal carcinomatosis; STIC, serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma.

Abdominal washing was known to be performed in 1,080 women of whom 38 had a STIC at RRSO. One of the 1,041 women without STIC demonstrated atypical cells in the abdominal washing, none had malignant cells. In the 38 women with STIC, one had atypical cells and four had malignant cells. The one woman with STIC and atypical cells did not undergo additional staging surgery, but received chemotherapy. These data were unknown for the woman without STIC with atypical cells in cytology. All four women with malignant cells underwent additional staging surgery and three of them also received chemotherapy. None of the six women with abnormal cytology developed PC during a follow-up of 58.5 (11-246) months.

Data on the performance of secondary staging surgery were available for 103 women (89.6%) with STIC. In 28 women (27.2%), a partial or complete staging surgery was conducted. Neither invasive cancer nor PC was diagnosed during 59.6 (11-245) months of follow-up.

Of 107 women (93.0%) with STIC, we had IPD regarding adjuvant chemotherapy after STIC diagnosis and 11 (10.3%) received chemotherapy. They had a median age of 50 (43-66) years; four carried a BRCA1-PV and five women also underwent additional staging surgery. One patient received monotherapy with platinum-based chemotherapy; the other 10 patients were treated with a combination of platinum and paclitaxel-based chemotherapy. The median number of cycles was 6 (range, 2-6). None of these 11 women developed PC during 96.0 (25.0-245.9) months of follow-up.

DISCUSSION

Our systematic review and IPDMA showed an increased risk of PC in BRCA1/2-PV carriers with a STIC at RRSO. The HR for developing PC in women with STIC is 33.9 (95% CI, 15.6 to 73.9), P < .001) compared with women without STIC. The 5- and 10-year risks to develop PC after RRSO are 10.5% (95% CI, 6.2 to 17.2) and 27.5% (95% CI, 15.6 to 43.9) for women with STIC, respectively, compared with 0.3% (95% CI, 0.2 to 0.6) and 0.9% (95% CI, 0.6 to 1.4) for women without STIC at RRSO. None of the women with STIC who underwent additional staging surgery (n = 28) or chemotherapy (n = 11) developed PC, but the data regarding additional treatment are insufficient for clinical recommendations.

The association between STIC at RRSO and subsequent PCs is described in several studies with PC incidences differing between 0 and 50%.20,21,28-41 These differences are most likely explained by the small sample sizes of 2-13 STICs per study. However, these disparities were also found between the two earlier systematic reviews that described a PC risk of 4.5% and 11%, respectively.20,42 The variation in duration of follow-up after RRSO, ranging from a few months to several years, might also be explaining these differences. Therefore, we conducted a meta-analysis on the basis of IPD to account for differences in follow-up and to study effects of patient characteristics. It was formerly thought that higher age at RRSO formed a risk factor to develop PC.17 In our analyses, age at RRSO was indeed clearly associated with the incidence of STIC at RRSO, but when STIC was found, age at RRSO was no longer a risk factor to develop PC. This is important for counseling these patients in clinical practice.12 Thus, women who underwent RRSO beyond the current guideline age, for example, because they discovered their BRCA-PV at later age, without STIC at pathologic assessment, have a much lower risk to develop PC than formerly assumed (0.9%; 95% CI, 0.6 to 1.4) at 10 years compared with the formerly assumed 3.9% for BRCA1 and 1.9% for BRCA2-PV carriers).10 However, the odds of finding a STIC increases with increasing age; thus, the recommendation remains to undergo RRSO within the current guideline age. It also supports early salpingectomy after completion of childbearing as is currently investigated in ongoing trials (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04294927, ISRCTN 25173360, and ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04251052).

Despite the high HR, the etiology of the association between STIC and PC is not completely clear. The association is mainly supported by the findings of identical TP53 mutations in isolated STIC and PC by Blok et al.36 One can imagine that PC might develop upon shedding of (pre)invasive cells throughout the abdomen before or at RRSO. If PC develops upon shedding of invasive cells, cases with isolated STIC are actually cases with missed invasive carcinomas. However, if these cases were mainly missed invasive carcinomas at RRSO, it is to be expected that the PC would occur relatively early after RRSO. As the median duration between isolated STIC and PC was 48.0 (18-118) months, accompanied by the fact that none of the PCs occurred within 18 months after RRSO, it seems unlikely that the isolated STICs were misdiagnosed invasive carcinomas. In only 28 cases, additional staging surgery was performed; moreover, it is unknown whether additional (deeper) slides of the fallopian tubes were reviewed by the pathologist after diagnosing the isolated STIC lesion. Both measures would lower the chance of missing an invasive carcinoma. In the case that preinvasive cells were shed throughout the abdomen, these cells might take years before developing into widespread PC. According to the evolutionary analyses by Labidi-Galy et al,43 a time span of seven years is expected between STIC and development into invasive high-grade serous carcinoma. There are also distinct, more complex hypotheses on ovarian cancer development after STIC. For example, the theory in which areas of morphologically normal but genetically mutated cells are present in the fallopian tube and peritoneum. These fields of cells with genomic instability are then at increased risk to develop into STIC or invasive cancer (ie, tubal cancer or PC). In this hypothesis, STIC is a signal of a broader ongoing oncogenetic process instead of the primary source of cancer. The etiology of PC is not yet clarified, but on the basis of current literature, it is unlikely that PCs are actually missed invasive carcinomas at RRSO.

This IPDMA contains follow-up data from the largest cohort of participants with STIC diagnosed at RRSO. The IPDMA method is most suitable for investigating this issue because of the infrequent prevalence of STIC, which is about 3% in the BRCA-PV population.18 Moreover, the usage of IPD enables the adjustment for potential confounders and duration of follow-up. Our results are robust as results of individual studies were highly consistent and strengthened by the fact that a similar effect was found with a different analysis method (two-stage analysis), when aggregated data of studies without IPD were used, and when studies with IPD only on women with STIC were excluded. Although we reported the greatest number of STIC cases, the groups per study were relatively small and therefore, some bias by small study effect cannot completely be excluded. However, the results are very clear as 15 PCs occurred in 115 women with isolated STIC, whereas only 18 PCs occurred among 3,006 women without STIC. Reporting and publication bias might also be of influence, an effect we tried to minimize by searching in gray literature, requesting updates of follow-up, and by including three cohorts with unpublished data. Detection bias cannot be completely excluded, although we expect a minimal influence because the majority of STIC diagnoses were independent of PC diagnoses. A potential variability in pathologic assessment and STIC definition might introduce heterogeneity between studies, although the STIC definition was highly similar in the included studies.

The most important direct clinical implication is the increased knowledge on PC risk after RRSO, which should be used to postoperatively inform patients when discussing the pathology reports. This is important for both women with STIC, as for women without STIC since their risk for PC is lower than formerly communicated. Moreover, this emphasizes the importance of adherence to the SEE-FIM protocol and structural assessment by an experienced pathologist to minimize the chance of missing a STIC. The magnitude of the absolute cancer risk at 5 and 10 years after RRSO may support the ESGO guideline, which advises to consider staging surgery in case of a STIC.44 On the contrary, the hypothesis of PCs being misdiagnosed cases of invasive malignancies is not the most plausible one. Chemotherapy to lower the PC risk is yet another point of discussion, for which current literature is insufficient. The 11 cases with STIC whom received chemotherapy did not develop PC, but because of the low number of cases, a conclusion cannot be drawn. However, in the five studies with the 11 patients who received chemotherapy, in each study, a minority of women received chemotherapy after STIC diagnosis. In four patients, this was probably because of the positive abdominal washings; in the other seven patients, it might be due to a subjective higher risk of PC, for example, age at RRSO, or histopathologic characteristics of the STIC itself. In that case, the data are suggestive of a positive effect of chemotherapy on PC risk during follow-up, but more prospective data should be available before offering this treatment, as it has significant side effects. For less toxicity, PARP inhibitors might be considered, although current data are also too limited to provide recommendations. The data of our current study are a base to investigate these issues, and international collaboration to set up a large multicenter consortium study with long follow-up is urgently needed. Currently, objective measures are unavailable to determine which women with STIC are among the women who develop PC. Moreover, as the etiology of PC development is not yet elucidated, the effect of staging and/or chemotherapy on preventing PC is unknown. Future research should be directed at clarifying the etiology of PC after STIC in, for example, the microenvironment of the peritoneum. Moreover, research should be aimed at the histopathologic characteristics of the STIC itself: is it possible to identify women with a higher risk of PC by assessing the STIC on histopathologic characteristics such as size, localization, and molecular or immunohistochemical profile? Perhaps, digital pathology combined with artificial intelligence could be applied to this question.45

To conclude, BRCA1/2-PV carriers with STIC at RRSO are at increased risk of PC (HR, 33.9; 95% CI, 15.6 to 73.9; P < .001). This risk increases over time up to 27.5% (95% CI, 15.6 to 43.9) after 10 years, whereas the corresponding risk is only 0.9% (95% CI, 0.6 to 1.4) for women without STIC at RRSO. It is important that women are informed about this increased risk, and future research should focus on prospective data collection on STICs, PC etiology, and clinical management after STIC diagnosis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors would like to thank the Radboud medical library for assistance in the electronic database search.

Marielle Nobbenhuis

Consulting or Advisory Role: Intuitive Surgical

Mateja Krajc

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca, Pfizer

Vilius Rudaitis

Honoraria: Medtronic

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca/MedImmune

Research Funding: Inovio Pharmaceuticals

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: MSD Oncology, Roche, Karl Storz

Elizabeth M. Swisher

Leadership: IDEAYA Biosciences

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

See accompanying editorial on page 1850

PRIOR PRESENTATION

Presented in part at the European Society of Gynecological Oncology congress Prague, Czech Republic, October 30-31, 2021; and presented in part at the BRCA symposium Montreal, Canada, May 4-7, 2021.

SUPPORT

Supported in part (Lithuania) by the Research Council of Lithuania grant P-MIP-22-187 (V.R.). No other authors received financial support for this study.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Miranda P. Steenbeek, Joanne A. de Hullu

Provision of study materials or patients: Miranda P. Steenbeek, Christine Garcia, Han T. Cun, Karen H. Lu, Heleen J. van Beekhuizen, Lucas Minig, Katja N. Gaarenstroom, Marielle Nobbenhuis, Mateja Krajc, Vilius Rudaitis, Barbara M. Norquist, Elizabeth M. Swisher, Marian J.E. Mourits

Collection and assembly of data: Miranda P. Steenbeek, Johan Bulten, Julia A. Hulsmann, Joep Bogaerts, Christine Garcia, Han T. Cun, Karen H. Lu, Heleen J. van Beekhuizen, Lucas Minig, Katja N. Gaarenstroom, Marielle Nobbenhuis, Mateja Krajc, Vilius Rudaitis, Barbara M. Norquist, Elizabeth M. Swisher, Marian J.E. Mourits, Joanna IntHout, Joanne A. de Hullu

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Risk of Peritoneal Carcinomatosis After Risk-Reducing Salpingo-Oophorectomy: A Systematic Review and Individual Patient Data Meta-Analysis

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Marielle Nobbenhuis

Consulting or Advisory Role: Intuitive Surgical

Mateja Krajc

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca, Pfizer

Vilius Rudaitis

Honoraria: Medtronic

Consulting or Advisory Role: AstraZeneca/MedImmune

Research Funding: Inovio Pharmaceuticals

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: MSD Oncology, Roche, Karl Storz

Elizabeth M. Swisher

Leadership: IDEAYA Biosciences

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A: Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin 69:7-34, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuchenbaecker KB, Hopper JL, Barnes DR, et al. : Risks of breast, ovarian, and contralateral breast cancer for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. Jama 317:2402-2416, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oei AL, Massuger LF, Bulten J, et al. : Surveillance of women at high risk for hereditary ovarian cancer is inefficient. Br J Cancer 94:814-819, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu KH: Screening for ovarian cancer in asymptomatic women. JAMA 319:557-558, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buys SS, Partridge E, Black A, et al. : Effect of screening on ovarian cancer mortality: The Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) cancer screening randomized controlled trial. JAMA 305:2295-2303, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Menon U, Gentry-Maharaj A, Burnell M, et al. : Ovarian cancer population screening and mortality after long-term follow-up in the UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 397:2182-2193, 2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skates SJ, Greene MH, Buys SS, et al. : Early detection of ovarian cancer using the risk of ovarian cancer algorithm with frequent CA125 testing in women at increased familial risk—Combined results from two screening trials. Clin Cancer Res 23:3628-3637, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosenthal AN, Fraser LSM, Philpott S, et al. : Evidence of stage shift in women diagnosed with ovarian cancer during phase II of the United Kingdom Familial Ovarian Cancer Screening Study. J Clin Oncol 35:1411-1420, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eleje GU, Eke AC, Ezebialu IU, et al. : Risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 8:CD012464, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Finch AP, Lubinski J, Moller P, et al. : Impact of oophorectomy on cancer incidence and mortality in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. J Clin Oncol 32:1547-1553, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rebbeck TR, Kauff ND, Domchek SM: Meta-analysis of risk reduction estimates associated with risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst 101:80-87, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Practice bulletin No. 182 summary: Hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome. Obstet Gynecol 130:657–659, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richtlijn Hereditair Mamma/Ovariumcarcinoom . http://www.oncoline.nl/hereditair-mamma-ovariumcarcinoom

- 14.Daly MB, Pal T, Berry MP, et al. : Genetic/familial high-risk assessment: Breast, ovarian, and pancreatic, version 2.2021, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 19:77-102, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seidman JD, Zhao P, Yemelyanova A: Primary peritoneal high-grade serous carcinoma is very likely metastatic from serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma: Assessing the new paradigm of ovarian and pelvic serous carcinogenesis and its implications for screening for ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 120:470-473, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carlson JW, Miron A, Jarboe EA, et al. : Serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma: Its potential role in primary peritoneal serous carcinoma and serous cancer prevention. J Clin Oncol 26:4160-4165, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harmsen MG, Piek JMJ, Bulten J, et al. : Peritoneal carcinomatosis after risk-reducing surgery in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. Cancer 124:952-959, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng A, Li L, Wu M, et al. : Pathological findings following risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA mutation carriers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol 46:139-147, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuhn E, Kurman RJ, Vang R, et al. : TP53 mutations in serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma and concurrent pelvic high-grade serous carcinoma-evidence supporting the clonal relationship of the two lesions. J Pathol 226:421-426, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Hoeven NMA, Van Wijk K, Bonfrer SE, et al. : Outcome and prognostic impact of surgical staging in serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma: A cohort study and systematic review. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 30:463-471, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Powell CB, Swisher EM, Cass I, et al. : Long term follow up of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers with unsuspected neoplasia identified at risk reducing salpingo-oophorectomy. Gynecol Oncol 129:364-371, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Jong VMT, Moons KGM, Riley RD, et al. : Individual participant data meta-analysis of intervention studies with time-to-event outcomes: A review of the methodology and an applied example. Res Synth Methods 11:148-168, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perrone ME, Reder NP, Agoff SN, et al. : An alternate diagnostic algorithm for the diagnosis of intraepithelial fallopian tube lesions. Int J Gynecol Pathol 39:261-269, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. : Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Plos Med 6:e1000097, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute : Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Studies. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools

- 26.R Foundation for Statistical Computing V, Vienna, Austria: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 27.IntHout J, Ioannidis JP, Borm GF: The Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method for random effects meta-analysis is straightforward and considerably outperforms the standard DerSimonian-Laird method. BMC Med Res Methodol 14:25, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carcangiu ML, Peissel B, Pasini B, et al. : Incidental carcinomas in prophylactic specimens in BRCA1 and BRCA2 germ-line mutation carriers, with emphasis on fallopian tube lesions: Report of 6 cases and review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol 30:1222-1230, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reitsma W, De Bock GH, Oosterwijk JC, et al. : Support of the 'fallopian tube hypothesis' in a prospective series of risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy specimens. Eur J Cancer 49:132-141, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wethington SL, Park KJ, Soslow RA, et al. : Clinical outcome of isolated serous tubal intraepithelial carcinomas (STIC). Int J Gynecol Cancer 23:1603-1611, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Conner JR, Meserve E, Pizer E, et al. : Outcome of unexpected adnexal neoplasia discovered during risk reduction salpingo-oophorectomy in women with germ-line BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. Gynecol Oncol 132:280-286, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zakhour M, Danovitch Y, Lester J, et al. : Occult and subsequent cancer incidence following risk-reducing surgery in BRCA mutation carriers. Gynecol Oncol 143:231-235, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Poon C, Hyde S, Grant P, et al. : Incidence and characteristics of unsuspected neoplasia discovered in high-risk women undergoing risk reductive bilateral salpingooophorectomy. Int J Gynecol Cancer 26:1415-1420, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ricciardi E, Tomao F, Aletti G, et al. : Risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in women at higher risk of ovarian and breast cancer: A single institution prospective series. Anticancer Res 37:5241-5248, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Minig L, Cabrera S, Oliver R, et al. : Pathology findings and clinical outcomes after risk reduction salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA mutation carriers: A multicenter Spanish study. Clin Transl Oncol 20:1337-1344, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blok F, Dasgupta S, Dinjens WNM, et al. : Retrospective study of a 16 year cohort of BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers presenting for RRSO: Prevalence of invasive and in-situ carcinoma, with follow-up. Gynecol Oncol 153:326-334, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stanciu PI, Ind TEJ, Barton DPJ, et al. : Development of peritoneal carcinoma in women diagnosed with serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma (STIC) following risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy (RRSO). J Ovarian Res 12:50, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rush SK, Swisher EM, Garcia RL, et al. : Pathologic findings and clinical outcomes in women undergoing risk-reducing surgery to prevent ovarian and fallopian tube carcinoma: A large prospective single institution experience. Gynecol Oncol 157:514-520, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gornjec A, Merlo S, Novakovic S, et al. : The prevalence of occult ovarian cancer in the series of 155 consequently operated high risk asymptomatic patients - Slovenian population based study. Radiol Oncol 54:180-186, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rudaitis V, Mikliusas V, Januska G, et al. : The incidence of occult ovarian neoplasia and cancer in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers after the bilateral prophylactic salpingo-oophorectomy (PBSO): A single-center prospective study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 247:26-31, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Minig L, Chuang L, Patrono MG, et al. : Surgical Outcomes and complications of prophylactic salpingectomy at the time of benign hysterectomy in premenopausal women. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 22:653-657, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patrono MG, Iniesta MD, Malpica A, et al. : Clinical outcomes in patients with isolated serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma (STIC): A comprehensive review. Gynecol Oncol 139:568-572, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Labidi-Galy SI, Papp E, Hallberg D, et al. : High grade serous ovarian carcinomas originate in the fallopian tube. Nat Commun 8:1093, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Colombo N, Sessa C, Bois AD, et al. : ESMO-ESGO consensus conference recommendations on ovarian cancer: Pathology and molecular biology, early and advanced stages, borderline tumours and recurrent disease. Ann Oncol 30:672-705, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bera K, Schalper KA, Rimm DL, et al. : Artificial intelligence in digital pathology—New tools for diagnosis and precision oncology. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 16:703-715, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]