Medicine is facing a dangerous lack of accountability. We know that diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in our workforce support productivity, personal and professional well-being, and positive patient outcomes.1,2 We know that lack of DEI does the opposite. We know that building a diverse and inclusive workforce requires diverse and inclusive leadership; people need to see that their leaders look like them to believe that they belong.3 We know that half of medical students are women and half identify as non-White.4 Yet, in most instances, we seem unable or unwilling to promote, support, or sustain their representation.5 We are failing to practice the DEI that we preach.

Perhaps our lack of progress is because we are also unable or unwilling to reconcile women and/or people who identify as Black, Indigenous, Persons of Color (BIPOC), or Under-Represented in Medicine (URM) with our pictures of professionalism.

The Ambiguity of Professionalism Standards

Commonly understood as physicians' adherence to accepted standards, their code of conduct, and/or their portrayal of certain qualities, medical professionalism is an evaluation criterion in training, hiring, and promotion. It is the aspirational ideal, something we look to our leaders to teach and model.

It is also inherently biased. Professionalism standards are based on historical archetypes; they tend to support maleness and Whiteness.6 In the 1960s, when asked to draw a scientist, 99% of school-age children drew a man.6 Despite the fact that women represented roughly half of professionals in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) by the mid-2010s, children at that time still overwhelmingly drew men when asked the same question. Professionalism-based preferences in hiring, mentorship, and sponsorship (all necessary for medical professional advancement) tend to promote Western, White cultural standards of dress (suit over hijab), hairstyle (straight over afro), speech (English fluency over accents), communication (stoicism over emotion), name (White-sounding over foreign), and cultural fit (sameness over difference).7 Disadvantages compound and accumulate especially profoundly for those who inhabit the intersection of multiple historically marginalized identities.8

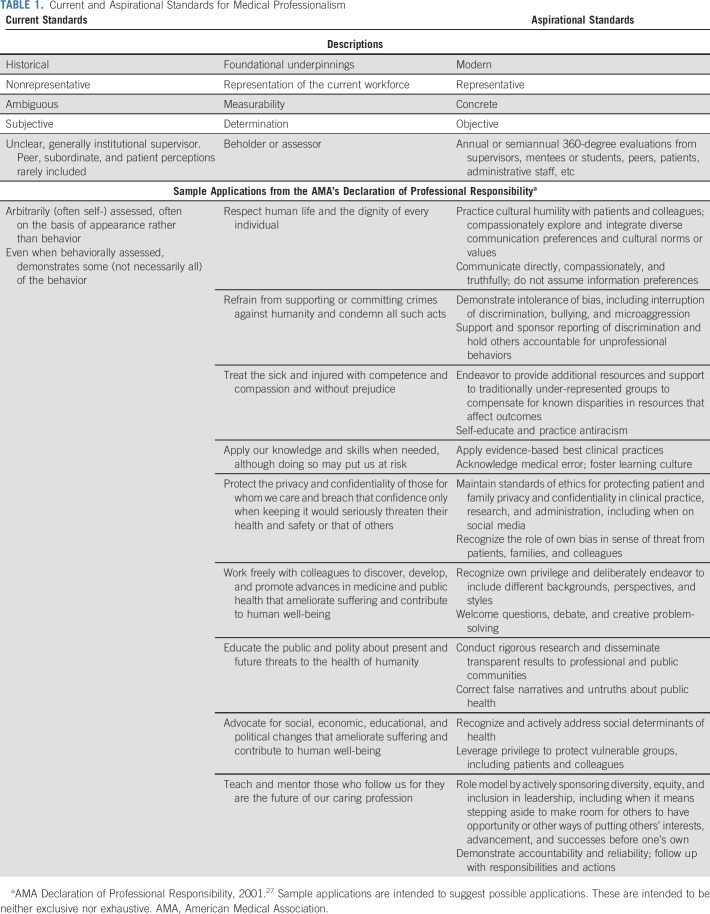

Even when organizations are transparent about their professionalism expectations, there is little clarity about who decides whether a person is sufficiently professional. For example, the American Medical Association's Declaration of Professional Responsibility includes lofty and immeasurable obligations such as “respect human life and the dignity of every individual,” and “advocate for social, economic, educational, and political changes that ameliorate suffering and contribute to human well-being.”9 Similar abstract statements are in many institutions' policies regarding professional (and unprofessional) conduct, including expectations of accountability, reliability, and overall integrity. Although these may justify disciplinary action for objective shortcomings such as plagiarism or billing fraud, they are problematic when individual professionalism is the eye of the beholder. Those who behold (and judge) tend to identify with (and use) the same archetypal benchmarks while picturing a professional. The resulting determinations of professionalism are subjective, cloaked in stereotypes, and ultimately discriminatory.

The Consequence of Outdated and Biased Professionalism Standards

Several recent cases underscore these challenges. Take, for example, the story of a prominent male academic oncologist who engaged in unethical sexual relationships with his female subordinates, including at least one trainee and multiple colleagues.10 He allegedly falsified legal documents, justified his actions because they advanced the woman's career, and received reprimands from three state medical boards. Despite all this, he maintained leadership and mentorship positions and was extolled as an exemplar of academic success.10 It took a literal Act of Congress to question his worthiness to represent the medical profession.11

Alternatively, consider the case of a well-qualified Black woman physician who was dismissed from her leadership position.12 Her antidiscrimination lawsuit is ongoing. Publicly available court documents allege that senior institutional leaders expressed concern that a Black leader would change the face of the institution. “White medical students wouldn't follow or rank favorably a program with a Black program director,” they said.12(p5) Although this woman fights for her career, institutional leaders move on.12

Finally, take the case of Shari Dunaway, a Latina medical student who publicly shared that she was deemed unprofessional and “docked a bunch of points on [the] med school OSCE for wearing hoop earrings.”13,14 Her social media post generated thousands of comments on the social construct of medical professionalism and its inherently discriminatory consequences for women and/or those who identify as BIPOC or URM. “How you speak, how you present yourself, is very culturally dependent,” said Briana Christophers, a different Latina MD-PhD student who was interviewed about the story. “To have people who are in a position of power over you getting to dictate whether you're being a good physician or not based on seemingly superficial attributes…is dangerous.”13

These examples occurred just in the past few months. They are only known because of the public outcry that followed. They represent three examples in a sea of biases that include sex, race, sexual orientation, gender identity, disability and myriad others.15 They illustrate both a lack of professional behavior by people in positions of influence and a lack of accountability by the medical community at large. They are not unique; gender discrimination in medicine includes disparities in pay, academic rank, and leadership, as well as these ubiquitous experiences of pervasive and uncorrected micro- and macroaggression toward women.5,16-19 Indeed, the same three states in the first case reported a total of 153 sexual harassment claims over 2 years.10 More than half of those have been substantiated, to date, and a minority of perpetrators have experienced (largely trivial) consequences including executive coaching, antiharassment training, or verbal warnings. It is little wonder that reporting of such experiences is rare.5

Similarly, discrimination against women of color in science is well-described.20 A 2014 study of professionals in STEM suggested that 100% of the 60 interviewed women who identified as BIPOC experienced at least one form of bias.20 Up to 77% reported having to provide more evidence of their competence than others to prove themselves, and up to 61% reported backlash for behaviors like assertiveness, self-promotion, or expression of anger.

In clinical oncology, specifically, women and/or people who identify as BIPOC are under-represented in the workforce and in positions of influence. Only 36% of medical, radiation, and surgical oncologists are women, and fewer women still (22%, 12%, and 4%) are in medical, radiation, and surgical oncology leadership positions, respectively.21 Only 2% of the oncology workforce identifies as Black or African American, and 3% as Hispanic or Latino.22 Recognizing the fact that a more representative workforce promotes improved productivity, outcomes, science, and clinical care, several organizations have called for immediate actions to address discrimination and achieve gender and racial parity in the oncology workforce.22,23

It is Time to Change Medical Professionalism Standards

We must rethink the application and merits of medical professionalism norms, at least as they are currently understood. We must decide: do we care about diversity (differences) or fit (sameness). We cannot have both.

Most medical professionals share the goal of promoting individual and public health. Such a common goal and a diverse workforce are not mutually exclusive. Rather, new frameworks of professionalism can help us achieve both. Doing so requires moving from historical, nonrepresentative, ambiguous, and subjective to modern, representative, concrete, and objective guidelines (Table 1). It also requires rethinking who has the privilege and training to decide if someone is professional or not. In almost all cases, professionalism guidelines should be determined and measured by diverse and representative members of the workforce, including those previously—and oftentimes currently—under-represented.

TABLE 1.

Current and Aspirational Standards for Medical Professionalism

The business industry is way ahead of the medical industry in these efforts. Not only is there evidence from corporations around the world that diversity and accountability in leadership improve performance, well-being, and company outcomes, but there is also guidance for how to adapt norms of professionalism to reflect and respect an evolving workforce.24 That shift begins with representation in leadership and commitments to diversity in hiring, promotion, and other positions of influence.25,26 It continues with a recognition and celebration of differences; we cannot integrate diverse perspectives and experiences without allowing our workers to be their authentic selves. The shift sustains itself with commitments to having difficult conversations, including those that question old norms or involve disciplining those whose actions are racist, sexist, homophobic, or otherwise discriminatory. Finally, this shift demands accountability; institutions, leaders, and all medical professionals must be held to these new standards of professionalism with measured metrics, progress reports, and action.

For too long, medical professionalism has implicitly been grounded in its past—a time when medical professionals were nearly all White males born into wealth and privilege. Students sitting in medical school classrooms today, however, look nothing like those from this bygone era, nor do they look like the portraits of prior eras' professionals adorning the institution's walls. Just like those portraits, our conceptualization of professionalism is out-of-date and no longer serves its intended purpose.

It is time for definitions of professionalism to include the practice of equity and inclusion, and it is time to hold our leaders accountable. We can no longer uphold the stature of those who perpetuate sexism, racism, and other biases. Neither can we claim that diversity does not belong in medicine by suppressing it under the cloak of professionalism. Picture a professional. What do you see? It is time that our picture represents the whole of our medical workforce.

Reshma Jagsi

Employment: University of Michigan

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Equity Quotient

Research Funding: Genentech (Inst)

Expert Testimony: Baptist Health/Dressman Benziger Lavalle Law, Kleinbard, LLC, Sherinian and Hasso

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Amgen

Other Relationship: JAMA Oncology

Open Payments Link: https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/physician/373670/summary

Jonathan M. Marron

Honoraria: Genzyme

Consulting or Advisory Role: Partner Therapeutics

Open Payments Link: https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/physician/802634/summary

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Financial support: Abby R. Rosenberg

Administrative support: Abby R. Rosenberg

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Picture a Professional: Rethinking Expectations of Medical Professionalism through the Lens of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Reshma Jagsi

Employment: University of Michigan

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Equity Quotient

Research Funding: Genentech (Inst)

Expert Testimony: Baptist Health/Dressman Benziger Lavalle Law, Kleinbard, LLC, Sherinian and Hasso

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Amgen

Other Relationship: JAMA Oncology

Open Payments Link: https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/physician/373670/summary

Jonathan M. Marron

Honoraria: Genzyme

Consulting or Advisory Role: Partner Therapeutics

Open Payments Link: https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/physician/802634/summary

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gomez LE, Bernet P: Diversity improves performance and outcomes. J Natl Med Assoc 111:383-392, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rock D, Grant H: Why Diverse Teams Are Smarter. Harvard Business Review, 2016. https://hbr.org/2016/11/why-diverse-teams-are-smarter [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kennedy JT, Jain-Lin P: What Does It Take to Build a Culture of Belonging? Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2021/06/what-does-it-take-to-build-a-culture-of-belonging, 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Association of American Medical Colleges: Diversity in medicine: Facts and figures 2019. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/report/diversity-medicine-facts-and-figures-2019 [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine : Sexual Harassment of Women: Climate, Culture, and Consequneces in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Washington, DC, National Academies Press, 2018 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crawford KF, WIndsor LC: Bias and 'professionalism.' 2019. https://medium.com/international-affairs-blog/bias-and-professionalism-c42abf65f4ba [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gray A: The Bias of "Professoinalism" Standards. Stanford Social Innovation Review, 2019. https://ssir.org/articles/entry/the_bias_of_professionalism_standards# [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crenshaw K: Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politic. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989. https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=1052&context=uclf [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Medical Association: AMA Declaration of Professional Responsibility. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/public-health/ama-declaration-professional-responsibility, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carolan A: Prominent GI Oncologist Axel Grothey Was Forced Out of Mayo Clinic for Unethical Sexual Relationships With Women He Mentored the Cancer Letter. https://cancerletter.com/the-cancer-letter/20210528_1/ [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldberg P, Bin Han Ong M: Congressional letter based on Grothey case demands answers on NIH policies on sexual misconduct by advisors. The Cancer Letter, 2021. https://cancerletter.com/capitol-hill/20210810_1/ [Google Scholar]

- 12.United States District Court, Eastern District of Louisiana : Dennar vs the Administrators of the Tulane Educational Fund, 2020. https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.laed.247389/gov.uscourts.laed.247389.1.0_1.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hatzipanagos R: A Doctor Was Deemed "unprofessional" for Wearing Hoops. Now Other Women of Color Are Speaking Out. The Lily (a product of the Washington Post), 2021. https://www.thelily.com/a-doctor-was-deemed-unprofessional-for-wearing-hoops-now-other-women-of-color-are-speaking-out/ [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dr Hoops [@ShariDunawayMD] : “I got docked a bunch of points on my med school OSCE for wearing hoop earrings during a test.” Twitter, June 28, 2021, https://twitter.com/ShariDunawayMD/status/1409598749731602433

- 15.Beeler WH, Cortina LM, Jagsi R: Diving beneath the surface: Addressing gender inequities among clinical investigators. J Clin Invest 129:3468-3471, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jena AB, Olenski AR, Blumenthal DM: Sex differences in physician salary in US public medical schools. JAMA Intern Med 176:1294-1304, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jena AB, Khullar D, Ho O, et al. : Sex differences in academic rank in US medical schools in 2014. JAMA 314:1149-1158, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jagsi R: Sexual harassment in medicine—#MeToo. N Engl J Med 378:209-211, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dzau VJ, Johnson PA: Ending sexual harassment in academic medicine. N Engl J Med 379:1589-1591, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams J, Phillips KW, Hall EV: Double Jeopardy? Gender Bias Against Women of Color in Science. 2014. https://worklifelaw.org/publications/Double-Jeopardy-Report_v6_full_web-sm.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chowdhary M, Chowdhary A, Royce TJ, et al. : Women's representation in leadership positions in academic medical oncology, radiation oncology, and surgical oncology programs. JAMA Netw Open 3:e200708, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winkfield KM, Flowers CR, Patel JD, et al. : American Society of Clinical Oncology strategic plan for increasing racial and ethnic diversity in the oncology workforce. J Clin Oncol 35:2576-2579, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diversity and inclusion in cancer research and oncology. Trends Cancer 6:719-723, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hunt V, Yee L, Prince S, et al. : Delivering through Diversity. 2018. https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/delivering-through-diversity [Google Scholar]

- 25.Perry-Smith J: You've Built a Racially Diverse Team. But Have You Built an Inclusive Culture? Harvard Business Review, 2021. https://hbr.org/2021/08/youve-built-a-racially-diverse-team-but-have-you-built-an-inclusive-culture?ab=hero-main-text [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knight R: How to Hold Your Company Accountable to Its Promise of Racial Justice. Harvard Business Review, 2020. https://hbr.org/2020/12/how-to-hold-your-company-accountable-to-its-promise-of-racial-justice [Google Scholar]

- 27.American Medical Association : AMA Declaration of Professional Responsibility. 2001. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/public-health/ama-declaration-professional-responsibility [Google Scholar]