Abstract

The concept of health system resilience has been challenged by the COVID-19 pandemic. Even well-established health systems, considered resilient, collapsed during the pandemic. To revisit the concept of resilience two years and a half after the initial impact of COVID-19, we conducted a qualitative study with 26 international experts in health systems to explore their views on concepts, stages, analytical frameworks, and implementation from a comparative perspective of high- and low-and-middle-income countries (HICs and LMICs). The interview guide was informed by a comprehensive literature review, and all interviewees had practice and academic expertise in some of the largest health systems in the world. Results show that the pandemic did modify experts' views on various aspects of health system resilience, which we summarize and propose as refinements to the current understanding of health systems resilience.

Keywords: Health systems, Health system resilience, Framework, Covid-19, Implementation

Introduction

The idea of improving the resilience of health systems has been studied and discussed since the 2000s, although not always using resilience as a concept (Gilson, 2012; Murray and Frenk, 2000; World Health Organization, 2010; World Health Organization, 2000). As external and internal shocks increasingly affected health systems functionality worldwide, the expression “health system resilience” emerged as an adaptable approach to analyzing the impacts of different types of crises, such as economic downturns (Thomas et al., 2013), the Ebola epidemic (Kruk et al., 2015; Ling et al., 2017), influxes of refugees (Alameddine et al., 2019; Ammar et al., 2016), and infectious disease outbreaks (Nuzzo et al., 2019), among others. Only after 2014, the concept of health system resilience gained relevance in reports from the European Union (EU) (European Commission, 2014), Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (OECD. Organisation for Economic Co-operation & Development, 2014), Oxfam (Kamal-Yanni, 2015), and the World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe (WHO/Europe) (WHO Europe, 2017). Analytical frameworks were designed to evaluate health system capacity for responding to public health emergencies, focusing predominantly on high- and low-and-middle-income countries (HICs and LMICs) (Irene Papanicolas et al., 2022; Thomas et al., 2020; WHO Europe, 2017).

With advances in the concept, stages, and dimensions of health system resilience, initiatives to monitor and evaluate proposed analytical frameworks emerged, such as the Global Health Security Index (Bell and Nuzzo, 2021) and the European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies reports (Sagan et al., 2021; Thomas et al., 2020; WHO Europe, 2021). Despite the efforts to establish the characteristics of the most resilient countries and to propose rankings among them, the COVID-19 pandemic (World Health Organization, 2020) has challenged the concept of resilience and brought new issues into the discussion (Forman et al., 2022). For example, the Global Health Security Index (Bell and Nuzzo, 2021) ranked the United States and the United Kingdom as the 1st and 7th countries, respectively, best prepared to respond to a new health emergency. Yet, based on the number of COVID-19 deaths per million people (University of Oxford, 2022), these countries have shown worse results than the world average. Countries with well-structured and integrated health systems, such as some Western European countries, were severely hit by the pandemic (Aarestrup et al., 2021; Burau et al., 2022). Also, qualitative and quantitative metrics in the health system resilience literature still face difficulties, in particular, related to qualitative indicators in the governance dimension and to quantitative indicators aimed at measuring changes associated with shocks (Fleming et al., 2022).

The COVID-19 pandemic is the most severe global health emergency since the 1918–19 influenza. It brought unprecedented challenges that tested health systems' capacity to cope and respond to shocks, ultimately revealing that the world was not prepared to respond to such emergencies. This raises the question of whether there is anything new we should look at after two and a half years on from the initial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic to update knowledge on the health system resilience concept, stages, analytical framework, and implementation mechanisms.

To address this question, we performed a two-step qualitative analysis. First, we conducted a comprehensive literature review to identify critical themes on health system resilience. Second, we conducted semi-structured interviews with 26 world-renowned experts in health systems, and the interview guide was informed by the themes identified in the first step. Semi-structured interviews aimed at collecting informed opinions on the gaps and needs for revision of the current understanding of health system resilience, considering the challenges imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

A deductive qualitative approach comprised a) a comprehensive literature review on health system resilience, b) semi-structured interviews with world-renowned health system experts (with an interview guide informed by the literature review), and c) content analysis of the interviews. The deductive qualitative approach was chosen to link the categories created by the scoping review with the knowledge collected from the experts in the interviews (Saulnier et al., 2022).

Literature review

We used a scoping review approach to collect and categorize scientific papers and reports about health system resilience in the world. In this sense, our literature review is qualitative in nature by extracting information on health system resilience concepts, stages, dimensions, or implementation, and not by measuring quantitatively the studies through bibliometric analysis or meta-analysis.

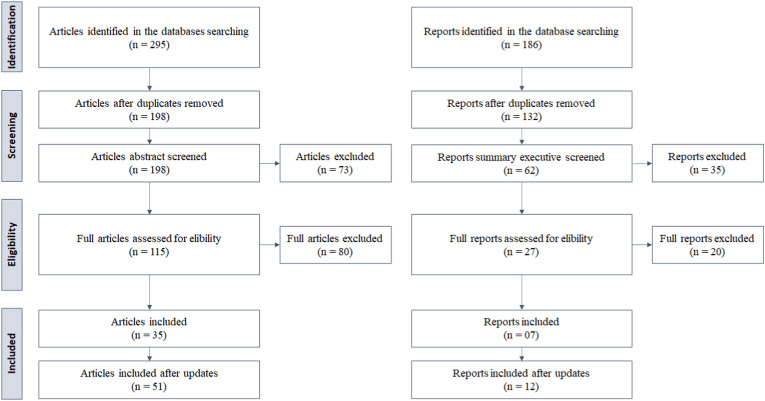

The first search was conducted in September 2020, and updated every 3 months until September 2022 (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Scoping review flow chart.

Description: the scoping review flow chart demonstrates the applied steps to collect and select the scientific papers and technical reports used in the paper.

For scientific papers, we searched the strings “health system” and “resilience” in the Web of Science, PubMed, and Scopus databases with no time filter. An initial screen was done based on the title, keywords, and abstract. For reports, we searched the strings “health system” and “resilience” and “report” in the google academic platform. Results were filtered by the publishing organization (e.g., World Health Organization and its regional offices, European Commission, OECD), and initially screened based on the title and abstract.

We used the Mendeley reference manager software to organize and detect duplicated studies. We used the PRISMA flow diagram to guide the steps and eligibility of the collected scientific papers and reports following Page et al. (2021). The authors screened the titles, abstracts, and summary executive and excluded those with clearly no relevant information to the health system resilience discussion. In sequence, the authors reviewed the full scientific papers and reports and elected those to be included in the final sample, based on their contribution to the health system resilience concept, stages, dimensions, or implementation.

We extracted from the included studies the general characteristics (title, authors, abstract, year, journal/organization) and the full texts. The full texts were analyzed through content analysis, and we created categories according to the health system resilience concept, stages, dimensions, or implementation to organize the existing topics.

Semi-structured interviews

We sought experts with solid knowledge of health systems, both in the practice and academic fields. The selection criteria were two-fold: i) current or previous work as a health system practitioner – e.g., worked for a government, served as a health advisor for a government, or worked in a WHO/UNICEF unit of a country, and/or ii) an academic with expertise and active research in health systems – e.g., professors, senior lecturers, or WHO/UNICEF advisors with published reports and/or relevant scientific papers.

Deductive content analysis of the semi-structured interview transcripts was done using QSR NVivo v.12. Categories and subcategories were discussed in light of the literature review and classified as novel contributions if not present in the available literature. In this sense, we deducted the content of the experts’ interviews through the categories and subcategories generated by the scoping review (Naylor et al., 2018).

Results

Scoping review

The scoping review identified 51 scientific papers and 12 reports. Their content was summarized into categories and subcategories (Table 1 ) that were used to guide and analyze the semi-structured interviews.

Table 1.

Categories and subcategories summarizing the systematic review.

| Categories/Subcategories (codes) |

References |

|---|---|

| 1. Health System Resilience Definition (concept) | |

| 1.1 capacity of a health system to absorb change but continue to retain essentially the same identity and function | (Odhiambo et al., 2020; Thomas et al., 2013; Turenne et al., 2019) |

| 1.2 capacity of health actors, institutions, and populations to prepare for and effectively respond to crises; maintain core functions when a crisis hits; and be informed by lessons learned pre, during, and after the crisis | (Chua et al., 2020; Haldane et al., 2017, 2021; Kruk et al., 2015; Ling et al., 2017; Nuzzo et al., 2019) |

| 1.3 capacity of a health system to absorb internal or external shocks, and maintain functional health institutions | (Ammar et al., 2016; Ozawa et al., 2016; Van de Pas et al., 2017) |

| 1.4 capacity of the health system to absorb, adapt and transform when exposed to a shock such as a pandemic, natural disaster, or armed conflict and still retain the same control of its structure and functions | (Abimbola et al., 2019; Alameddine et al., 2019; Blanchet et al., 2017; Khan et al., 2018; Nzinga et al., 2021; Saulnier et al., 2021; Turenne et al., 2019; Wiig and O’Hara, 2021) |

| 1.5 ability to prepare for, manage (absorb, adapt, and transform) and learn from shocks | (Biddle et al., 2020; Fridell et al., 2020; Thomas et al., 2020) |

| 1.6 COVID-19 changes the health system resilience definition | |

| 1.6.1 an improvement, with the insert and giving more attention to preparing, and later to learning, inserting the previous “steps” into the management place. | (Biddle et al., 2020; Fridell et al., 2020; Haldane and Morgan, 2021; Thomas et al., 2020) |

| 1.6.2 more attention to the steps, to evaluate the process | (Burke et al., 2021; Thomas et al., 2020) |

| 2. Health System Resilience Stages | |

| 2.1 preparedness, shock onset and alert, shock impact and management, and recovery and Learning | (Burke et al., 2021; Khan et al., 2018; Thomas et al., 2020) |

| 3. Health System Resilience Dimensions | |

| 3.1 financing, health services provision, resource generation, stewardship, vertical integration, and external factors to the health system – as a network | Murray and Frenk (2000) |

| 3.2 financing, services delivery, health workforce, health information systems, medicines, and leadership and governance - as building blocks | (Ammar et al., 2016; Bigoni et al., 2022; Fridell et al., 2020; McDarby et al., 2019; World Health Organization, 2010) |

| 3.2.1 medicines, vaccines, and technology. | Olu (2017) |

| 3.2.2 “community engagement” dimension | (Barasa et al., 2018; Khan et al., 2018; Nzinga et al., 2021) |

| 3.3 financial resilience; adaptive resilience and transformative resilience | Thomas et al. (2013) |

| 3.3.1 focus on governance: “anticipatory capacity, absorptive capacity, adaptive capacity, and transformative capacity” | (Alameddine et al., 2019; Blanchet et al., 2017; Burau et al., 2022; WHO Europe, 2017) |

| 3.3.2 cognitive, contextual, and behavioural capacities – strategies | (Gilson et al., 2020; Kagwanja et al., 2020) |

| 3.4 attributes: aware, diverse, self-regulating, integrated, and adaptive | (Foroughi et al., 2022; Humphrey Cyprian Karamagi et al., 2022; Ling et al., 2017; Nuzzo et al., 2019) |

| 3.5 synthetic version of the World Health Organization building blocks: governance, financing, resources, and services delivery | (Irene Papanicolas et al., 2022; Sagan et al., 2021; Thomas et al., 2020) |

| 3.5.1 expanding with new dimensions: political environment and community, legal foundation, risk communication, and containment measures | (Chua et al., 2020; Humphrey Cyprian Karamagi et al., 2022; Meyer et al., 2020) |

| 3.5.2 final framework excludes leadership and includes public health functions | (Haldane et al., 2021; Mustafa et al., 2021) |

| 3.6 inputs, outputs, and outcomes, crossing with equity, efficiency, and financing | (European Commission, 2020; Rogers et al., 2021) |

| 4. Incorporate Health System Resilience | |

| 4.1 investing and protecting health funding | (Burau et al., 2022; Etienne et al., 2020; Lal et al., 2021; Sagan et al., 2021; Thomas et al., 2020) |

| 4.2 health system with a people-centered focus | (Thomas et al., 2013; WHO Europe, 2017) |

| 4.3 equity and universal coverage | (Foroughi et al., 2022; Lal et al., 2021; Massuda et al., 2018) |

| 4.4 strengthening the health system capacities - adaptive, absorptive, and transformative | (Burau et al., 2022; Jung et al., 2021; Saulnier et al., 2021; WHO Europe, 2017) |

| 4.5 protect the provision of the services, as well as the health workforce in this process | (el Bcheraoui et al., 2020; Kagwanja et al., 2020; Sagan et al., 2021; Thomas et al., 2020, 2013) |

| 4.6 a constant and interactive network with other spheres (actors) and countries, including the knowledge of the scientific community | (Blanchet et al., 2017; Gilson et al., 2020; Jit et al., 2021; Kruk et al., 2015; Legido-Quigley et al., 2020) |

| 4.7 an integration of communication technologies to support a constant and interactive network | (European Commission, 2020; Foroughi et al., 2022; Rogers et al., 2021; Saulnier et al., 2022) |

| 4.8 one health approach | (Aarestrup et al., 2021; Forman et al., 2022) |

| 4.9 community engagement, solidarity, and trust (legitimacy) in the communication, associated with leadership, local or not, and governance. | (Alameddine et al., 2019; Blanchet et al., 2017; Chua et al., 2020; Forman et al., 2022; Haldane et al., 2021; Legido-Quigley et al., 2020; Nzinga et al., 2021; Ozawa et al., 2016) |

| 4.10 developing plans and protocols during all the process (before until after), with flexibility and coordination, and monitoring capacity | (Meyer et al., 2020; Mustafa et al., 2021; Nuzzo et al., 2019; Rogers et al., 2021; Sagan et al., 2021; Thomas et al., 2020) |

| 4.11 protect the medicines and physical resources supply chain | (Kagwanja et al., 2020; Perehudoff et al., 2021) |

| 5. Health System Resilience Framework – Implementation | |

| 5.1 to be in the political agenda and process, with stability | (Alameddine et al., 2019; Forman et al., 2022; Kruk et al., 2015; Rogers et al., 2021; Saulnier et al., 2022) |

| 5.2 create new political spaces to discuss and deliberate about the health system resilience | (Khan et al., 2018; Saulnier et al., 2022; Van de Pas et al., 2017) |

| 5.3 coordinate the different political leaders and communities during the event | (Abimbola et al., 2019; Chua et al., 2020; Foroughi et al., 2022; Lal et al., 2021) |

| 5.4 have a strong legal and regulatory foundation to support it, with legal proceedings and being flexible to adapt to new scenarios | (Barasa et al., 2018; Chua et al., 2020; Forman et al., 2022; Kruk et al., 2015; Nuzzo et al., 2019; Thomas et al., 2020) |

| 5.5 protect the social structure to justify the resilience issue | (Etienne et al., 2020; Ozawa et al., 2016; Thomas et al., 2013) |

| 5.6 have funding to discuss and implement the framework | (European Commission, 2020; Rogers et al., 2021) |

| 5.7 combinate the technical resources – communication, workforce, and structure, with new strategies and knowledge | (Abimbola et al., 2019; Alameddine et al., 2019; Bigoni et al., 2022; Ling et al., 2017; Thomas et al., 2013, 2020) |

| 5.8 information, technology, and data, as important issues to give relevance to the implementation | (el Bcheraoui et al., 2020; European Commission, 2020; Rogers et al., 2021) |

Description: the selected scientific papers and technical reports generated categories and subcategories to guide and analyze the interviews.

Description: the selected scientific papers and technical reports generated categories and subcategories to guide the and analyze the interviews.

Semi-structured interviews

We interviewed 26 world-renowned health system experts, with experience in 27 countries across all continents, except Antarctica (Fig. 2 ), between November 23, 2021, and March 1st, 2022. The final sample included health systems’ perspectives from 7 of the 10 most populous countries in the world (China, India, the United States, Brazil, Nigeria, Russia, and Mexico) (World Bank, 2021), and some of the leading universities and organizations in health system research (Table 2 ). The interviews had an average duration of 28 min, ranging from 14 to 59 min (Appendix 1). Although the length of the interviews varied across interviewees, we did not observe any differences in the depth of information collected by interview length.”

Fig. 2.

Countries whose Health System's experience was represented in the sample.

Table 2.

Characteristics of experts interviewed.

| Continents | Asia, Africa, Europe, North America, South America, and Oceania. |

|---|---|

| Countries* |

Asia: China, India, and the Philippines. Africa: Angola, Mozambique, Nigeria, and South Africa. Europe: Cyprus, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Liberia, Netherlands, Portugal, Serbia, Slovenia, Spain, Russia, and the United Kingdom. North America: Barbados, Canada, Mexico, and the United States. South America: Brazil. Oceania: Australia and New Zealand. |

| Organizations* practical background |

Non-governmental: World Health Organization (Africa, Americas, Europe, South-East Asia, Western Pacific, China, and Russia), World Bank; World Economic Forum, International Monetary Fund, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund, United Nations Development Programme, UK Medical Research Council, Commonwealth Fund International Program, and Public Health Foundation of India. Governmental: Ministry or Department of Health (Australia, Brazil, India, Mexico, Nigeria, Portugal, and Spain), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and European Commission. |

| Organizations* academic background | Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, University of Miami, London School of Economics, Trinity College Dublin, NOVA School of Business and Economics, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, University of São Paulo, UTS Business School, Getúlio Vargas Foundation, Grattan Institute, Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, University of Massachusetts Amherst, and the University of Campinas. |

| Positions* | Advisors (health, social or economic), Coordinators (health systems), University leadership, Directors and Representative of international organizations, Leader Economists, Leader Physicians, Ministers and Secretariats of Health, Directors of public health associations, Professors, and Researchers. |

| * Countries, organizations, and positions were listed if the interviewee was engaged in the work for at least 2 years. | |

Description: the world-renowned health system experts were characterized according to their countries' knowledge, organizational practical and academic background, and positions.

Description: the map represents the countries based on the health system experts experience, selected if the expert was engaged in the country for at least 2 years.

Description: the world-renowned health system experts were characterized according to their countries knowledge, organizational practical and academic background, and positions.

Health system resilience - concept

The scoping review indicated an evolution in the concept of health system resilience. Initially, there was a focus on the capacity of the system to absorb shocks and maintain its functions and identity (Thomas et al., 2013). This initial concept was revised to consider (i) preparedness and learning, including the analysis of the role of actors, such as institutions and the population (Chua et al., 2020; Kruk et al., 2015; Ling et al., 2017; Nuzzo et al., 2019); (ii) recognizing that shocks could be internal or external to the system (Ammar et al., 2016; Ozawa et al., 2016; Van de Pas et al., 2017); (iii) management as a sequence of actions that imply absorbing, adapting, and transforming; and (iv) different shock types, such as epidemics, pandemics, or natural disasters (Blanchet et al., 2017; Khan et al., 2018; Nzinga et al., 2021; Saulnier et al., 2021). Lastly, based on previous studies, a synthetic version was created considering the ability of preparedness, management (including absorb, adapt, and transform), and learning when facing a shock (Biddle et al., 2020; Fridell et al., 2020; Thomas et al., 2020).

Analysis of the semi-structured interviews showed that experts interviewed demonstrated knowledge of the health system resilience concept and its evolution, mainly with the emphasis on the ability or capacity to keep the health system operating and learning about shocks (Haldane et al., 2021; Kruk et al., 2015; Thomas et al., 2013, 2020). According to the interviews, however, that ability or capacity could influence or be influenced by community participation and context understanding. This is a novel concept improvement, not found in the scoping review. As one interviewee said:

“… healthcare systems don’t happen to people, they happen with people. So at the same time understand their expectations and how they react when a crisis happens … and then we switch back to the technical part because it is a lot easier. And then we follow to political and then legal ….”

When inquired about possible changes in the health system resilience concept considering COVID-19, experts suggested that the concept of health system resilience has been tested, challenged, and therefore changed.

“It showed a certain amount of flexibility, and the things that people might have taken years to implement in a hospital were implemented overnight. A pivot to telehealth, for example, things, you know, people have been talking about that, but well, it just had to happen.”

The changes proposed are a) resilience needs to have a strong element of context in your concept; b) health system resilience should go beyond the health care boundaries, emphasizing the need for financial, political, and social support; c) health care supply chain gained importance in the health system resilience discussion, with influence on public policies; d) health system resilience should include new technologies and instruments to strength resilient health system, as artificial intelligence and telemedicine; and e) surveillance, governance instruments, and social measures should gain more relevance in the health system resilience debate.

Health system resilience - stages

Based on the scoping review, health system resilience includes four stages (Burke et al., 2021; Khan et al., 2018; Thomas et al., 2020). The first, preparedness, represents the health system's readiness to respond before the shock event (Aarestrup et al., 2021; el Bcheraoui et al., 2020). The second, onset and alert, aims to understand the shock and establish timelines of action (Thomas et al., 2020). The third, shock impact and management, refers to the health system in action during the shock, with some adaptations and transformations to keep the health system operating (Burke et al., 2021; Khan et al., 2018). Finally, recovery and learning is the process of rethinking the health system and how it could be made more resilient (Sagan et al., 2021; Sheikh and Abimbola S. editor, 2021).

Experts interviewed proposed some changes to this framework. The first relevant change is to consider the four stages as a complex adaptive system with a continuing process of multiple interconnected and interdependent interactions among stages, thus building upon the framework developed by Thomas et al. (2020).

“They're all connected in true life. They overlap quite a lot. We are dealing with a complex adaptive system. I mean, unfortunately, when we try and classify stages, which is convenient, because when we are trying to under each heading consider, what are the actions that are required, what are the consequences of an action? And what are the consequences of inaction? It is convenient to divide into stages, but quite often, we find that in a complex adaptive system, there is an iteration of very many factors and alteration of very many factors as they come into play. And therefore, I don't think we can always say that these are sequential”.

At the core of that adaptive system should be the decision-making process and management capacity, influencing all the stages of action. Interviewees discussed the importance of the decision-making process through management. Therefore, the decision-makers – e.g., health system managers, front-line health professionals, among others – are the core of the adaptive system, and the management capacity connects them with all the other stages. Also, the resilience adaptive system is part of the health system, which influences and is influenced by the context.

Health system resilience - dimensions

Based on the scoping review, dimensions to be considered in the assessment of health system resilience have their roots in analytical frameworks to evaluate health system performance, initially proposed by the WHO in 2000 (Murray and Frenk, 2000). Over time, many changes were proposed to those frameworks, with dimensions (or building blocks) to analyze health systems including financing, service delivery, health workforce, health information systems, medicines/vaccines/technology (Olu, 2017), leadership and governance (World Health Organization, 2010), and community engagement (Barasa et al., 2018; Khan et al., 2018). These health systems dimensions contributed to creating a version to evaluate health systems resilience, proposed in 2020 and continued to be refined until 2022 (Irene Papanicolas et al., 2022; Thomas et al., 2020). Dimensions considered include governance, financing, resources, services delivery, political environment and community, legal foundation, risk communication, and containment measures (Haldane et al., 2021; Mustafa et al., 2021).

We cited in the interviews the building blocks framework (World Health Organization, 2010) and two health system resilience frameworks (Haldane et al., 2021; Thomas et al., 2020) to contextualize the discussion. Experts interviewed suggested several changes to health system resilience dimensions, such as (i) the framework needs to act as an integrated system, not fragmented by building blocks due to the relationship among dimensions; (ii) the center level is the decision-makers dimension, connected with the health system resilience dimensions through technology and information; (iii) technology and information gain relevance with the role of interfacing with all the health system resilience dimensions improving their performance; (iv) regulation is part of governance and leadership in the dimension; (v) a fourth level is proposed to connect the health system resilience dimensions with the context, through communication and social participation; and (vi) the inclusion of medical and public health approaches in the services provision dimension.

“Only things missing there. I thought was the government's response. The health information systems. Some of these elements were missing.”

“We need to use a little bit of bottom-up, which means to know how the organizations and institutions responded and adjusted (…). But also, it needs to understand the top down, and how the system works from top to down, because we are talking about mobilization, information systems, (…).”

Health system resilience in a comparative perspective

Based on experts’ interviews, there should be no differences in how the governance, leadership, and regulation dimensions of resilience are implemented in health systems in HICs or LMICs. Governance and regulation mechanisms, such as decision-making, evidence-based, and accountability, are more frequently found in HICs. Resources dimensions (human, physical and structural) in HICs are usually greater than in LMICs due to the greater financial capacity.

As for the medicines dimension, the COVID-19 pandemic showed the importance of logistics and healthcare supply chain, particularly for the delivery of vaccines. Here, HICs have been learning and adapting the health system services provision dimension faster than LMICs.

Regarding technology and information, one of the different elements could be the instruments and tools to plan, monitor, and evaluate these targets, such as information and communications technologies. HICs usually have a better instrumental capacity to follow and incorporate targets.

“(…) the essential difference here between developed and developing countries is probably in the available resources. (…) everything that is a decision-making process, informatics and mobilization infrastructure, and resources that could be mobilized probably, I would say, there you would have some difference to developing countries.”

In contrast, communication and social participation are important instruments to influence the governance, leadership, and regulation dimension, and do not depend on being HIC or LMIC. Also, before incorporating resilience into countries’ health systems, it is important to comprehend the context. Some context elements include trust in institutions; solidarity; the likelihood of outbreaks (natural disasters, war, or conflict); socioeconomic vulnerability; and whether primary health care works as the health system base. Despite that, social protection mechanisms play an important role to keep the health system resilient.

Health system resilience framework implementation

Resilience framework implementation is a major gap in the literature, based on the scoping review. Experts interviewed discussed implementation considering political, legal, economic, and technical perspectives. From a political perspective, four issues were identified as critical: (i) bring society to the center of the discussion through participatory mechanisms that facilitate understanding of what a resilient health system would mean to them; (ii) adapt the international discussion to national, regional, and local scenarios; (iii) have the government, or a policy champion, supporting implementation in different levels; and (iv) create a transformation process in the health system, with a long- and well-established plan. Legal elements, such as laws, decrees, and ordinances, could influence implementation, as they (a) connect the different subsystems in the healthcare sector (public, private, and supplementary), (b) measure and understand the impact of healthcare judicialization, and (c) have a strong and flexible regulation to quickly support the health system adaptation.

“(…) you're going to have to engage, not just the Ministry of Health, but all the particular economy, finance, the other sectors that have been very clearly impacted by the pandemic and make the strong, make the strong justification, (…). The arguments at the moment will be you, you should be able to make them even recognizing the current situation there at the moment, from the economic perspective on the political economy perspective. Also, (…) strengthening of the health system there from the technical a strategic perspective.”

From an economic perspective, it is essential to establish a fund to support implementation, understand the resource constraints of the healthcare system, and improve resources management capacity in strategic areas. Lastly, regarding technical elements, five actions were highlighted by the experts: (i) create or adapt a national representative survey to increase social participation and bottom-up communication by analyzing people's perception of what a resilient health system is; (ii) establish national, state, regional, and local data analysis capacity; (iii) improve health care data system interoperability between government spheres (e.g., federal, state, regional and local) and country borders, health care subsystems (private x public), and different services delivery subsystems (e.g., PHC and specialized care); (iv) have a high and stable competent team to manage, implement, monitor, and assess the health system resilience framework implementation; and (v) create a benchmarking atmosphere between the health departments in state, regional and local levels.

Discussion

Health system resilience has gained relevance in academic and practical discussions, affecting the decision-making process of many countries worldwide since the beginning of the 21st century. In the last two and a half years, the COVID-19 pandemic challenged the concept of health system resilience. Here, we reviewed the current literature and conducted interviews with experts to discuss the advances in health system resilience.

First, the resilience concept was improved with the addition of one important element: context dependence (Gilson et al., 2020; Sagan et al., 2021). It is important to consider the management and learning capacity with shocks, but also the context in which the shock happens. The capacity or ability to respond must engage the community, with an empathetic approach, and be adapted to local contexts. This understanding provides a refinement to the health system resilience definition as seen in the last studies (Biddle et al., 2020; Fridell et al., 2020; Haldane et al., 2021; Thomas et al., 2020). Specifically, it could be read as the “ability to prepare for, manage (absorb, adapt, and transform) and learn from shocks, based on community participation and context adaptation”. This refinement was influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic, placing more emphasis on non-medical elements, such as health surveillance (Haldane and Morgan, 2021; Legido-Quigley et al., 2020; Sundararaman et al., 2021), health care supply chain (Bhaskar et al., 2020b; Kandel et al., 2020), governance mechanisms to coordinate integrated responses (Haldane et al., 2021; Haldane and Morgan, 2021), and speed in the development and incorporation of new health technologies to support response worldwide (from vaccines to digital health) (Bhaskar et al., 2020a).

Second, we summarized the suggestions regarding the health system resilience stages in Fig. 3 . Decision-making gains a central role in the response to shocks and crises, supported by its management capacity, connected with all the health system resilience stages, and in constant interaction with the health system and the context. Most importantly, the previous four health system resilience stages discussed in the literature (Thomas et al., 2020) should be seen as an adaptive system (Atun et al., 2013; Haldane et al., 2021).

Fig. 3.

Health system resilience adaptive stages.

Description: the scheme illustrates the health system resilience stages, with a complex-based adaptive system and in constant interaction. Decision-making has a central role and is operationalized by the management capacity to connect with the 4 stages, acting in the health system environment and context.

Third, the scoping review and interviews brought advances in the health system resilience dimensions, with a new and adaptable framework. We summarize the findings in Fig. 4 and propose a system-based approach with technology and information systems playing an important role to connect the decision-makers with all the health system resilience dimensions (Yoon et al., 2022). In this refined framework, regulation gains more emphasis on governance and leadership (Bhaskar et al., 2020a; Kandel et al., 2020; Kringos et al., 2020; Sagan et al., 2021), and communication and social participation appear in the fourth level, connecting all other dimensions with the context. Therefore, the proposed framework (Fig. 4) advances in the health system resilience analysis with a system model, based on the importance of the decision-makers and management capacity, powered by technology and information, to improve the third-level dimensions performance. Also, the framework shows the importance of communication and participation to connect the health system's performance with the context.

Fig. 4.

Health system resilience framework.

Description: the figure illustrates an adaptable health system resilience framework. The decision-makers are in the center and connected with the 6 dimensions through technology and information. All the health system resilience dimensions interact with the context using communication and social participation.

In a comparative vision between HICs and LMICs, the main differences to incorporate resilience in health systems are resources (Haldane et al., 2021; Haldane and Morgan, 2021), social protection capacity, logistics and supply chain structure, and information and communication technologies (Bhaskar et al., 2020b; Haldane et al., 2021; Sundararaman et al., 2021). Governance mechanisms depend on the democracy maturity stage and are more frequently found in HICs (Foroughi et al., 2022; Lal et al., 2021; Robert et al., 2022), while communication and social participation, context, and target dimensions play a similar role in all countries. To properly respond to crises, it is necessary to have all parts of the health system resilience framework work together.

Regarding the implementation of the health system resilience framework, it is necessary to understand people's expectations about what a resilient healthcare system to them would be (Haldane et al., 2021; Nimako and Kruk, 2021), adapt the discussion to different government levels (H. C. Karamagi et al., 2022), and have policy support and a strong narrative (Herron et al., 2022). Therefore, organizations and actors must be connected (Kringos et al., 2020; Sundararaman et al., 2021; Williamson et al., 2022), through an improved information system (Chua et al., 2020; Jit et al., 2021; Sagan et al., 2021) and flexible regulation, to better respond to a crisis (Bhaskar et al., 2020a; Kandel et al., 2020). Having a stable team to manage the initiative and create a benchmarking environment between all the actors should be considered (Carroll et al., 2022; Yoon et al., 2022).

Finally, most studies on health systems resilience have focused on the context of HICs with well-established health systems or LICs with very fragile systems. It is essential to expand studies on health system's resilience in the context of MICs with highly fragmented systems in the public and private sectors.

Conclusion

Based on a scoping review and in-depth interviews we propose improvements in the health system resilience discussion. We revisited key aspects of the concept, stages, dimensions/framework, differences across countries, and framework implementation.

This paper contributed new conceptual insights to the health system resilience academic debate as well as to the policy and practical discussion around the topic by i) advancing towards a refinement in the health system resilience 4 adaptive stages model and the health system resilience framework; ii) pointing out differences in the way health systems resilience should be incorporated in HICs and LMICs, iii) identifying the timing and conditions upon which the health system resilience framework should be implemented; and iv) identifying gaps in the understanding of health system resilience in countries with fragile institutions and financial vulnerability.

Credit author statement

Marco Antonio Catussi Paschoalotto - Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Software; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing. Marcia C. Castro and Adriano Massuda - Conceptualization; Investigation; Methodology; Project administration; Resources; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing. Rudi Rocha and Eduardo Alves Lazzari - Conceptualization; Methodology; Project administration; Supervision; Validation; Visualization; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Ethics approval

The research received ethical approval by the Committee for Ethical Compliance in Research Involving Human Beings of Fundação Getulio Vargas (CEPH/FGV) on September 27th, 2021–228/2021 statement number.

Consent to participate

Before voluntary participation, all participants were informed that their responses would be used only for scientific purposes.

Consent for publication

All authors provided consent for this publication.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies (DRCLAS), Harvard University, for financial support, and São Paulo School of Business Administration, Fundação Getúlio Vargas (EAESP/FGV-SP), for institutional support.

Handling Editor: W Yip

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.115716.

Appendix ASupplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Aarestrup F.M., Bonten M., Koopmans M. Pandemics– one health preparedness for the next. The Lancet Regional Health - Europe. 2021;9:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abimbola S., Baatiema L., Bigdeli M. The Impacts of Decentralization on Health System Equity, Efficiency and Resilience: A Realist Synthesis of the Evidence. 2019. Health Policy Plan. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alameddine M., Fouad F.M., Diaconu K., Jamal Z., Lough G., Witter S., Ager A. Resilience capacities of health systems: accommodating the needs of Palestinian refugees from Syria. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019;220:22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ammar W., Kdouh O., Hammoud R., Hamadeh R., Harb H., Ammar Z., Atun R., Christiani D., Zalloua P.A. Health system resilience: Lebanon and the Syrian refugee crisis. J Glob Health. 2016;6 doi: 10.7189/jogh.06.020704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atun R., Aydin S., Chakraborty S., Sümer S., Aran M., Gürol I., Nazlioǧlu S., Özgülcü Ş., Aydoǧan Ü., Ayar B., Dilmen U., Akdaǧ R. Universal health coverage in Turkey: enhancement of equity. Lancet. 2013 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61051-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barasa E., Mbau R., Gilson L. What is resilience and how can it be nurtured? A systematic review of empirical literature on organizational resilience. Int. J. Health Pol. Manag. 2018 doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2018.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bcheraoui C., Weishaar H., Pozo-Martin F., Hanefeld J. Assessing COVID-19 through the lens of health systems' preparedness: time for a change. Glob. Health. 2020 doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00645-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell J.A., Nuzzo J.B. 2021. Global Health Security Index: Advancing Collective Action and Accountability amid Global Crisis. [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskar S., Bradley S., Chattu V.K., Adisesh A., Nurtazina A., Kyrykbayeva S., Sakhamuri S., Yaya S., Sunil T., Thomas P., Mucci V., Moguilner S., Israel-Korn S., Alacapa J., Mishra A., Pandya S., Schroeder S., Atreja A., Banach M., Ray D. Telemedicine across the globe-position paper from the COVID-19 pandemic health system resilience PROGRAM (REPROGRAM) international consortium (Part 1) Front. Public Health. 2020;8 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.556720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskar S., Tan J., Bogers M.L.A.M., Minssen T., Badaruddin H., Israeli-Korn S., Chesbrough H. At the epicenter of COVID-19–the tragic failure of the global supply chain for medical supplies. Front. Public Health. 2020;8 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.562882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biddle L., Wahedi K., Bozorgmehr K. Health System Resilience: A Literature Review of Empirical Research. 2020. Health Policy Plan. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigoni A., Malik A.M., Tasca R., Baleeiro M., Carrera M., Maria L., Schiesari C., Gambardella D.D., Massuda A. Brazil's Health System Functionality amidst of the COVID-19 Pandemic: an Analysis of Resilience. 2022. The Lancet Regional Health - Americas 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchet K., Nam S.L., Ramalingam B., Pozo-Martin F. Governance and capacity to manage resilience of health systems: towards a new conceptual framework. Int. J. Health Pol. Manag. 2017;6:431–435. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2017.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burau V., Falkenbach M., Neri S., Peckham S., Wallenburg I., Kuhlmann E. Health system resilience and health workforce capacities: comparing health system responses during the COVID‐19 pandemic in six European countries. Int. J. Health Plann. Manag. 2022 doi: 10.1002/hpm.3446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke S., Parker S., Fleming P., Barry S., Thomas S. Building health system resilience through policy development in response to COVID-19 in Ireland: from shock to reform. The Lancet Regional Health - Europe. 2021;9:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll R., Duea S.R., Prentice C.R. Implications for health system resilience: quantifying the impact of the COVID-19-related stay at home orders on cancer screenings and diagnoses in southeastern North Carolina, USA. Prev. Med. 2022;158 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2022.107010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua A.Q., Tan M.M.J., Verma M., Han E.K.L., Hsu L.Y., Cook A.R., Teo Y.Y., Lee V.J., Legido-Quigley H. Health system resilience in managing the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons from Singapore. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etienne C.F., Fitzgerald J., Almeida G., Birmingham M.E., Brana M., Bascolo E., Cid C., Pescetto C. COVID-19: transformative actions for more equitable, resilient, sustainable societies and health systems in the Americas. BMJ Glob Health. 2020 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Commission . 2014. Communication from the Commission: on Effective, Accessible and Resilient Health Systems. (Brussels) [Google Scholar]

- European Commission . 2020. THE ORGANISATION of RESILIENT HEALTH and SOCIAL CARE FOLLOWING the COVID-19 PANDEMIC: Opinion of the Expert Panel on Effective Ways of Investing in Health (EXPH). Luxemburg. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming P., O'Donoghue C., Almirall-Sanchez A., Mockler D., Keegan C., Cylus J., Sagan A., Thomas S. Health Policy. 2022. Metrics and Indicators Used to Assess Health System Resilience in Response to Shocks to Health Systems in High Income Countries—A Systematic Review. New York. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman R., Azzopardi-Muscat N., Kirkby V., Lessof S., Nathan N.L., Pastorino G., Permanand G., van Schalkwyk M.C., Torbica A., Busse R., Figueras J., McKee M., Mossialos E. Drawing light from the pandemic: rethinking strategies for health policy and beyond. Health Pol. 2022;126:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2021.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foroughi Z., Ebrahimi P., Aryankhesal A., Maleki M., Yazdani S. Toward a theory-led meta-framework for implementing health system resilience analysis studies: a systematic review and critical interpretive synthesis. BMC Publ. Health. 2022;22 doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-12496-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridell M., Edwin S., Schreeb J., von Saulnier D.D. Health system resilience: what are we talking about? A scoping review mapping characteristics and keywords. Int. J. Health Pol. Manag. 2020;9:6–16. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2019.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilson Lucy. In: Health Policy and Systems Research : a Methodology Reader. Gilson L., editor. Word Health Organization; 2012. (Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research). [Google Scholar]

- Gilson L., Ellokor S., Lehmann U., Brady L. Organizational change and everyday health system resilience: lessons from Cape Town, South Africa. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020;266 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldane V., Morgan G.T. From resilient to transilient health systems: the deep transformation of health systems in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Pol. Plann. 2021;36:134–135. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czaa169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldane V., Ong S.E., Chuah F.L.H., Legido-Quigley H. Health systems resilience: meaningful construct or catchphrase? Lancet. 2017 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30946-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldane V., de Foo C., Abdalla S.M., Jung A.-S., Tan M., Wu S., Chua A., Verma M., Shrestha P., Singh S., Perez T., Tan S.M., Bartos M., Mabuchi S., Bonk M., McNab C., Werner G.K., Panjabi R., Nordström A., Legido-Quigley H. Health systems resilience in managing the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons from 28 countries. Nat. Med. 2021;27:964–980. doi: 10.1038/S41591-021-01381-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herron L.-M., Phillips G., Brolan C.E., Mitchell R., O’reilly G., Sharma D., K€ S., Kendino M., Poloniati P., Kafoa B., Cox M. When all else fails you have to come to the emergency department”: overarching lessons about emergency care resilience from frontline clinicians in Pacific Island countries and territories during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2022.100519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jit M., Ananthakrishnan A., Mckee M., Wouters O.J., Beutels P., Teerawattananon Y. Multi-country collaboration in responding to global infectious disease threats: lessons for Europe from the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Regional Health - Europe. 2021;9:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung A.-S., Haldane V., Neill R., Wu S., Jamieson M., Verma M., Tan M., de Foo C., Abdalla S.M., Shrestha P., Chua A.Q., Bristol N., Singh S., Bartos M., Mabuchi S., Bonk M., McNab C., Werner G.K., Panjabi R., Nordström A., Legido-Quigley H. National responses to covid-19: drivers, complexities, and uncertainties in the first year of the pandemic. BMJ. 2021 doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-068954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagwanja N., Waithaka D., Nzinga J., Tsofa B., Boga M., Leli H., Mataza C., Gilson L., Molyneux S., Barasa E. Shocks, stress and everyday health system resilience: experiences from the Kenyan coast. Health Pol. Plann. 2020;35:522–535. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czaa002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamal-Yanni M. 2015. Never Again: Building Resilient Health Systems and Learning from the Ebola Crisis. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel N., Chungong S., Omaar A., Xing J. Health security capacities in the context of COVID-19 outbreak: an analysis of International Health Regulations annual report data from 182 countries. Lancet. 2020;395:1047–1053. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30553-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karamagi, Humphrey Cyprian, Titi-Ofei R., Kipruto H.K., Seydi A.B.W., Droti B., Talisuna A., Tsofa B., Saikat S., Schmets G., Barasa E., Tumusiime P., Makubalo L., Cabore J.W., Moeti M. On the resilience of health systems: a methodological exploration across countries in the WHO African Region. PLoS One. 2022;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0261904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan Y., O'Sullivan T., Brown A., Tracey S., Gibson J., Généreux M., Henry B., Schwartz B. Public health emergency preparedness: a framework to promote resilience 11 medical and health sciences 1117 public health and health services. BMC Publ. Health. 2018;18 doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-6250-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kringos D., Carinci F., Barbazza E., Bos V., Gilmore K., Groene O., Gulácsi L., Ivankovic D., Jansen T., Johnsen S.P., de Lusignan S., Mainz J., Nuti S., Klazinga N., Baji P., Brito Fernandes O., Kara P., Larrain N., Meza B., Murante A., Pentek M., Poldrugovac M., Wang S., Willmington C., Yang Y. Managing COVID-19 within and across health systems: why we need performance intelligence to coordinate a global response. Health Res. Pol. Syst. 2020;18 doi: 10.1186/s12961-020-00593-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruk M.E., Myers M., Varpilah S.T., Dahn B.T. What is a resilient health system? Lessons from Ebola. Lancet. 2015 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60755-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lal A., Erondu N.A., Heymann D.L., Gitahi G., Yates R. Fragmented health systems in COVID-19: rectifying the misalignment between global health security and universal health coverage. Lancet. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32228-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legido-Quigley H., Asgari N., Teo Y.Y., Leung G.M., Oshitani H., Fukuda K., Cook A.R., Hsu L.Y., Shibuya K., Heymann D. Are high-performing health systems resilient against the COVID-19 epidemic? The Lancet. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ling E.J., Larson E., MacAuley R.J., Kodl Y., Vandebogert B., Baawo S., Kruk M.E. Beyond the crisis: did the Ebola epidemic improve resilience of Liberia's health system? Health Pol. Plann. 2017;32 doi: 10.1093/heapol/czx109. iii40–iii47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massuda A., Hone T., Leles F.A.G., de Castro M.C., Atun R. The Brazilian health system at crossroads: progress, crisis and resilience. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2018-000829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDarby G., Reynolds L., Zibwowa Z., Syed S., Kelley E., Saikat S. The global pool of simulation exercise materials in health emergency preparedness and response: a scoping review with a health system perspective. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2019-001687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer D., Bishai D., Ravi S.J., Rashid H., Mahmood S.S., Toner E., Nuzzo J.B. A checklist to improve health system resilience to infectious disease outbreaks and natural hazards. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray C.J.L., Frenk J. Theme Papers A framework for assessing the performance of health systems. Bull. World Health Organ. 2000;78:717–731. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa S., Zhang Y., Zibwowa Z., Seifeldin R., Ako-Egbe L., McDarby G., Kelley E., Saikat S. Health Policy Plan; 2021. COVID-19 Preparedness and Response Plans from 106 Countries: a Review from a Health Systems Resilience Perspective. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor M.D., Hirschman K.B., Toles M.P., Jarrín O.F., Shaid E., Pauly M.v. Adaptations of the evidence-based transitional care model in the U.S. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018;213:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimako K., Kruk M.E. Seizing the moment to rethink health systems. Lancet Global Health. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00356-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuzzo J.B., Meyer D., Snyder M., Ravi S.J., Lapascu A., Souleles J., Andrada C.I., Bishai D. What makes health systems resilient against infectious disease outbreaks and natural hazards? Results from a scoping review. BMC Publ. Health. 2019;19 doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7707-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nzinga J., Boga M., Kagwanja N., Waithaka D., Barasa E., Tsofa B., Gilson L., Molyneux S. An Innovative Leadership Development Initiative to Support Building Everyday Resilience in Health Systems. 2021. Health Policy Plan. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odhiambo J., Jeffery C., Lako R., Devkota B., Valadez J.J. Measuring health system resilience in a highly fragile nation during protracted conflict: south Sudan 2011-15. Health Pol. Plann. 2020;35:313–322. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czz160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Organisation for Economic Co-operation & Development . 2014. Guidelines for Resilience Systems Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Olu O. Resilient health system as conceptual framework for strengthening public health disaster risk management: an african viewpoint. Front. Public Health. 2017;5 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozawa S., Paina L., Qiu M. Exploring pathways for building trust in vaccination and strengthening health system resilience. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016;16:131–141. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1867-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page M.J., McKenzie J.E., Bossuyt P.M., Boutron I., Hoffmann T.C., Mulrow C.D., et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372(71) doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papanicolas Irene, Rajan Dheepa, Karanikolos Marina, Soucat Agnes, Figueras Josep. 2022. Health System Performance Assessment. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perehudoff K., Dur C., Demchenko I., Mazzanti V., Parwani P., Suleman F., de Ruijter A. Impact of the European Union on access to medicines in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review. The Lancet Regional Health - Europe. 2021;9:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert E., Zongo S., Rajan D., Ridde V. Contributing to collaborative health governance in africa: a realist evaluation of the universal health coverage partnership. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022;22:753. doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-08120-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers H.L., Barros P.P., de Maeseneer J., Lehtonen L., Lionis C., McKee M., Siciliani L., Stahl D., Zaletel J., Kringos D. Resilience testing of health systems: how can it be done? Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2021;18 doi: 10.3390/ijerph18094742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagan A., Webb E., Azzopardi-Muscat N., de La Mata I., Mckee M., Figueras J. vol. 56. 2021. (Lessons for Building Back Better Health Policy Health Policy Series Series No). [Google Scholar]

- Saulnier D.D., Blanchet K., Canila C., Cobos Muñoz D., Dal Zennaro L., de Savigny D., Durski K.N., Garcia F., Grimm P.Y., Kwamie A., Maceira D., Marten R., Peytremann-Bridevaux I., Poroes C., Ridde V., Seematter L., Stern B., Suarez P., Teddy G., Wernli D., Wyss K., Tediosi F. A health systems resilience research agenda: moving from concept to practice. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6 doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-006779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saulnier D.D., Thol D., Por I., Hanson C., von Schreeb J., Alvesson H.M. We have a plan for that”: a qualitative study of health system resilience through the perspective of health workers managing antenatal and childbirth services during floods in Cambodia. BMJ Open. 2022;12 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-054145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheikh K., Abimbola S., editors. Learning Health Systems: Pathways to Progress. Flagship report of the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research; Geneva: 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Sundararaman T., Muraleedharan V.R., Ranjan A. Pandemic resilience and health systems preparedness: lessons from COVID-19 for the twenty-first century. J. Soc. Econ. Dev. 2021;23:290–300. doi: 10.1007/s40847-020-00133-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S., Keegan C., Barry S., Layte R., Jowett M., Normand C. A framework for assessing health system resilience in an economic crisis: Ireland as a test case. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2013;13 doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-450. (undefined) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S., Sagan A., Larkin J., Cylus J., Figueras J., Karanikolos M. 2020. Strengthening Health Systems Resilience POLICY BRIEF 36 Key Concepts and Strategies HEALTH SYSTEMS and POLICY ANALYSIS. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turenne C.P., Gautier L., Degroote S., Guillard E., Chabrol F., Ridde V. Conceptual analysis of health systems resilience: a scoping review. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- University of Oxford . 2022. Our World in Data.https://ourworldindata.org URL: accessed 3.22.22. [Google Scholar]

- van de Pas R., Ashour M., Kapilashrami A., Fustukian S. Interrogating resilience in health systems development. Health Pol. Plann. 2017;32 doi: 10.1093/heapol/czx110. iii88–iii90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Europe . 2017. Strengthening Resilience: a Priority Shared by Health 2020 and the Sustainable Development Goals. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Europe . 2021. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies.https://eurohealthobservatory.who.int/ [WWW Document]. URL. accessed 10.25.21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiig S., O'Hara J.K. Resilient and responsive healthcare services and systems: challenges and opportunities in a changing world. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021;21:1037. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-07087-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson A., Forman R., Azzopardi-Muscat N., Battista R., Colombo F., Glassman A., Marimont J.F., Javorcik B., O'Neill J., McGuire A., McKee M., Monti M., O'Donnell G., Wenham C., Yates R., Davies S., Mossialos E. Effective post-pandemic governance must focus on shared challenges. Lancet. 2022 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00891-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank . 2021. Population 2020 - World Bank Data. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2000. Health Systems: Improving Performance. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2010. Monitoring the Building Blocks of Health Systems: a Handbook of Indicators and Their Measurement Strategies. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . World Health Organization; 2020. WHO Director-General’s Opening Remarks at the Media Briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon S., Goh H., Chan A., Malhotra R., Visaria A., Matchar D., Lum E., Seng B., Ramakrishnan C., Quah S., Koh M.S., Tiew P.Y., Bee Y.M., Abdullah H., Nadarajan G.D., Graves N., Jafar T., Ong M.E.H. Spillover effects of COVID-19 on essential chronic care and ways to foster health system resilience to support vulnerable non-COVID patients: a multistakeholder study. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2022;23:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2021.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.