1 |. INTRODUCTION

Respiratory distress is a common complaint for children seeking medical attention. Recurrent episodes are most often attributed to upper respiratory tract infections or asthma, but other causes do occur.1 Here, we describe the case of a previously healthy girl with episodes of severe respiratory distress recurring over several years.

2 |. CASE PRESENTATION

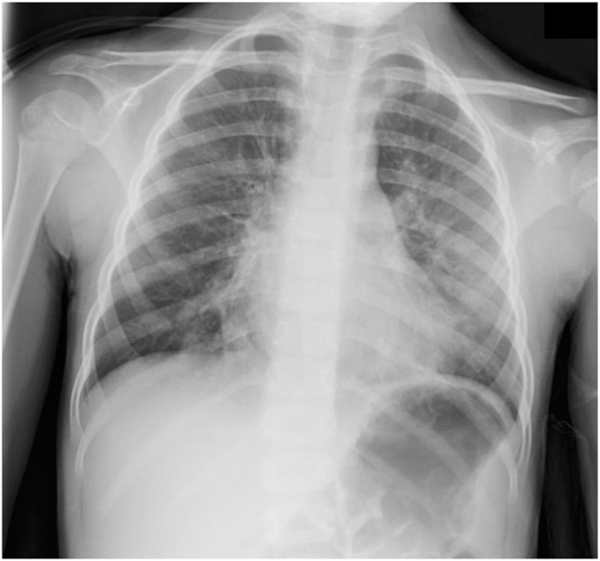

An otherwise healthy 3-year-old girl presented to the emergency department in severe respiratory distress. Symptoms included cough, wheeze, and labored breathing. She required admission to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) for severe respiratory distress and hypoxemia. She was treated with epinephrine and systemic corticosteroids for presumed anaphylaxis due to a recent horse exposure. She fully recovered and remained asymptomatic for 1 year before experiencing a similar episode, this time without exposure to a likely trigger. Despite initially feeling well, she awoke in the middle of the night with a persistent dry cough and was seen by her pediatrician the next morning. On examination, she was found to be coughing and wheezing and was in mild to moderate respiratory distress with pulse oximetry in the mid-80s while breathing ambient air. She again required admission to the PICU for severe respiratory distress and hypoxemia. Despite epinephrine and systemic corticosteroids, her hypoxemia worsened and bilevel positive airway pressure was initiated. An echocardiogram was unremarkable, but a chest radiograph revealed bilateral lower lobe subsegmental opacities (Figure 1) (Supporting Information Podcast 1*). She was started on azithromycin for presumed atypical pneumonia; her symptoms rapidly resolved, and she was discharged from the PICU 2 days later.

FIGURE 1.

Posterior-anterior (PA) radiograph of the chest: Perihilar interstitial opacities, peribronchial cuffing, and bilateral, bibasilar opacities suggestive of atelectasis

Given the severity and recurrent nature of her acute illnesses, she was referred for pulmonary consultation. Outside of a few minor colds without symptom progression, she had been asymptomatic between her two hospitalizations. Each episode presented with acute, rapidly progressing symptoms in the absence of fever, night sweats, or weight loss. She was growing well, had no signs of aspiration or reflux, and had no history of recurrent nonpulmonary infections. There was no history of sleep disturbance and she was physically active including participating in downhill skiing without shortness of breath. She was born full-term with a benign nursery stay. She had a history of a horse and peanut allergy but denied the need for bronchodilators or inhaled steroids except when hospitalized. There was no smoke or pet exposure at home and there had been no recent travel. No one in the family had a history of pulmonary disease. Her pediatrician repeated the chest radiograph after her most recent admission, and it was reported to be normal. Physical examination revealed a well-appearing 5-year-old girl who was developing appropriately and had a clear chest upon auscultation. There was no murmur and she was not clubbed. Growth was appropriate. Given the uncertain etiology of her acute respiratory symptoms and the prolonged period where she was asymptomatic, the decision was made to follow her closely to see if the symptoms returned.

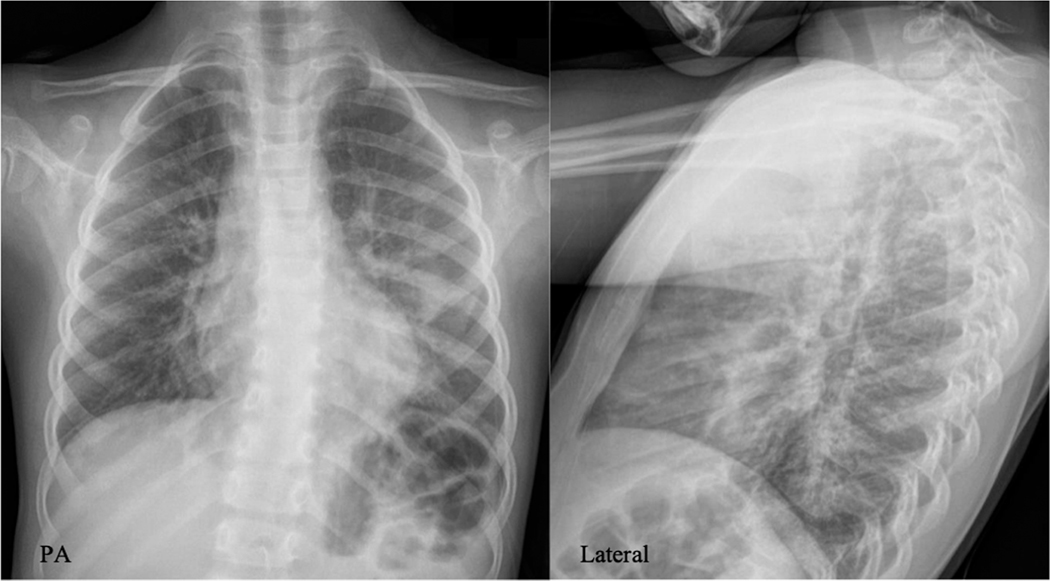

One month later she developed acute onset of cough that woke her from sleep. The mother reported peri-oral cyanosis and audible wheezing. There was no recent exposure to horses or peanuts. Her mother called an ambulance and the child was taken to the emergency department where she was found to be hypoxemic with an oxygen saturation of 88% on room air. Crackles were audible over the right middle lobe, right lower lobe, and left lower lobe. A chest radiograph demonstrated bilateral perihilar interstitial and bibasilar opacities, similar to the prior film (Figure 2) (Supporting Information Podcast 2).

FIGURE 2.

Posterior-anterior (PA) and lateral radiographs of the chest: (PA) Prominent perihilar interstitial markings and bibasilar opacities more pronounced on the left. (Lateral) No evidence of hyperinflation

2.1 |. Challenge point

A 5-year-old girl with recurrent episodes of respiratory distress requiring hospitalization, who presented to the emergency department with acute onset of hypoxemia and an abnormal chest radiograph.

2.2 |. Learner reflection

What is most likely going on with this patient (differential diagnosis and leading diagnosis)?

What would you do next and why?

Listen to the Supporting Information Podcast 3 to hear the consortium’s decision-making process.

2.3 |. Case progression

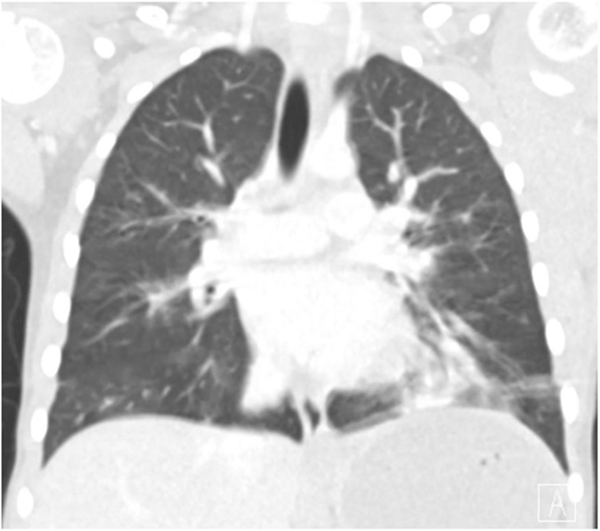

She was admitted to the pediatric service and started on systemic corticosteroids. She required up to 6 L/min of supplemental oxygen therapy while at rest and more with ambulation. A complete blood count with differential was unremarkable, and inflammatory markers were only mildly elevated (erythrocyte sedimentation rate 24 mm/h, C-reactive protein 40 mg/L). Computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest revealed ground-glass opacities and subsegmental atelectasis in the left lower lobe (Figure 3) (Supporting Information Podcast 4). Further laboratory tests included antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and mycoplasma titers, which were both negative. The IgE was elevated (790 IU/ml), specific serum IgE testing was positive for cats, dogs, dust mites, and trees, and an IgG hypersensitivity panel was positive for aspergillus and basidiospores. Flexible bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage showed no evidence of bacterial infection, aspiration, or hemorrhage and there were no anatomic abnormalities noted. She was able to wean off supplemental oxygen 5 days into her hospitalization. Given the elevated total and specific IgE levels and continued wheeze, she was discharged on inhaled fluticasone and oral cetirizine.

FIGURE 3.

Computed tomography scan of the chest: (Coronal image) Multifocal, subsegmental, bilateral atelectasis, and ground-glass opacities in the left lower lobe

There was concern her recurrent symptoms may be in part due to a mold exposure given the positive hypersensitivity panel for aspergillus and basidiospores. The parents subsequently tested their home, found these same molds, and installed an air purification system. She fully recovered and was asymptomatic for 5 months before developing a minor respiratory tract infection manifested by a dry cough. She was found to have crackles at the bases bilaterally despite a normal chest radiograph. She was treated as an outpatient with prednisone and reported improvement after 7 days. She was well for the next year until she developed acute onset of cough, wheeze, and dyspnea upon exertion. In the emergency department, she was found to be hypoxemic with an oxygen saturation of 88% on room air. Chest exam revealed bibasilar crackles and expiratory wheeze. A chest radiograph was unrevealing.

2.4 |. Challenge point

A 6-year-old girl with a presumed diagnosis of hypersensitivity pneumonitis in significant respiratory distress with no clear trigger.

2.5 |. Learner reflection

What is most likely going on with this patient (differential diagnosis and leading diagnosis)?

Is there anything else you would do at this time?

Listen to Supporting Information Podcast 5 to hear the consortium’s decision-making process.

2.6 |. Case progression

She was again admitted to the pediatric service and treated with supplemental oxygen and prednisone. She rapidly improved over 2 days and was discharged without a clear diagnosis. She fully recovered and was well for 3 months, when she developed a mild upper respiratory infection manifested by rhinorrhea and cough. Over a 12-h period, she became dyspneic and her mother recorded an oxygen saturation of 87%. In the emergency department, her chest exam again revealed bilateral crackles, she required supplemental oxygen via a nonrebreather mask to maintain adequate oxygenation and was ultimately admitted to the PICU on high flow oxygen via nasal cannula. Chest CT revealed scattered linear opacities throughout both lungs most consistent with atelectasis and resolution of the ground glass opacities previously seen in the left lower lobe. Her oxygenation improved over the subsequent 2 days, but she still required 2 L/min low flow nasal cannula at rest and 4 L/min with mild ambulation.

2.7 |. Challenge point

A 7-year-old girl admitted with recurrent respiratory distress of unclear etiology with signs of a diffusion defect evidenced by desaturation with ambulation combined with an unremarkable chest CT.

2.8 |. Learner reflection

What is most likely going on with this patient (differential diagnosis and leading diagnosis)?

What would you do next and why?

Listen to Supporting Information Podcast 6 supp to hear the consortium’s decision-making process.

2.9 |. Case progression

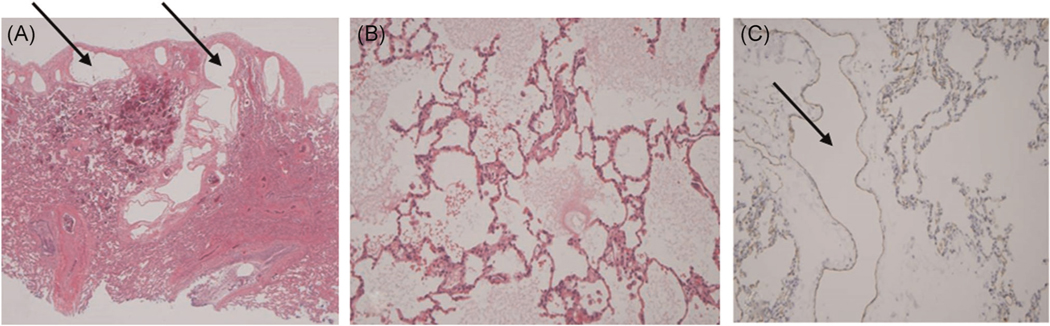

The patient’s recurrent respiratory illnesses were felt to be exacerbations of a diffuse process, and because the episodes were increasing in frequency with no clear etiology, the decision was made to obtain tissue. She underwent a thoracoscopic lung biopsy with a sampling of the left upper and lower lobes. Pathological examination using D2 40 and CD 31 staining demonstrated markedly dilated lymphatic channels most prominent in the subpleural regions without evidence of acute inflammation, granulomas, vasculitis, or malignancy. Further staining was consistent with pulmonary lymphangiectasia (Figure 4). She tolerated the procedure well and was discharged 2 days later. Given the lack of standard therapeutic options, a decision was made to treat future episodes of hypoxemia with as-needed oral furosemide due to the edema-like nature of her symptoms.

FIGURE 4.

Lung biopsy: (A) left lower lobe: dilated lymphatics along the subpleural space and septae (arrows), (B) left upper lobe: diffuse pulmonary edema (C) left upper lobe: CD 31 staining for lymphatics demonstrating a dilated lymphatic channel (arrow)

Over the subsequent year, she reported two episodes of respiratory distress similar to her previous illnesses. She developed a mild cough followed by wheeze and dyspnea each time. In the first episode, her mother gave her 2 mg/kg oral furosemide and called an ambulance for fear of escalation. By the time the child reached the emergency department her respiratory status was markedly improved, and she did not require admission, which represented an improvement compared to previous episodes requiring hospitalization. The second episode was also treated by a single dose of oral furosemide, but this time the patient’s symptoms resolved at home without the need for urgent evaluation.

3 |. DISCUSSION

A previously healthy 3-year-old female developed recurrent episodes of respiratory distress manifested by acute cough, crackles, and hypoxemia initially thought to be secondary to hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Her condition evolved over the course of approximately 3 years between the initial onset of symptoms and the ultimate diagnosis of primary pulmonary lymphangiectasia (PPL).

PPL is a rare congenital disorder characterized by dilation of subpleural, interlobar, perivascular, and peribronchial lymphatics.2 Pulmonary lymphangiectasia is classified as either primary due to an intrinsic defect in the pulmonary lymphatics, or secondary caused by lymphatic obstruction.2 PPL is often thought to be fatal and a cause of fetal demise,3 but after the neonatal period outcomes are mixed. Presentations range from nonimmune hydrops fetalis to respiratory distress requiring varying degrees of support.4 Diagnosis requires pathologic evidence of dilated lymphatics. Initial presentation of PPL after the newborn period, as was the case in this patient, has not been well described.

This patient initially presented with intermittent episodes of respiratory distress manifested by common respiratory signs and symptoms including cough, wheeze, crackles, and hypoxemia. Given that PPL has not been documented in otherwise healthy children outside of the newborn period, other more common entities were considered. It was not until she underwent a lung biopsy that the diagnosis was made. In hindsight, her recurrent respiratory distress, wheeze, crackles, and hypoxemia were most likely secondary to pulmonary edema due to abnormal lymphatic function. As this presentation of PPL has not been previously described, treatment with as-needed furosemide was initiated targeting the apparent pathophysiology and was ultimately successful in preventing further hospitalizations.

This patient had an unremarkable medical history for the first 3 years of life. She was diagnosed and treated for presumed anaphylaxis at 3 years of age, a common pediatric diagnosis,5 and was relatively asymptomatic for the next year. She subsequently required admission to the PICU secondary to what was thought to be atypical pneumonia. In retrospect, the bilateral perihilar interstitial and subsegmental opacities most likely represented atelectasis and pulmonary edema which is why she rapidly improved when placed on noninvasive positive pressure ventilation. As her symptoms became more frequent, she was trialed on inhaled corticosteroids and antihistamines given her atopic background. Due to continued episodes of respiratory distress and hypoxemia despite good compliance and technique with prescribed medications, the differential diagnosis was broadened looking for environmental exposures.

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) is a rare interstitial lung disease with a presentation in childhood often associated with exposure to antigens in the home environment.6 Diagnosis is based on exposure, compatible clinical and radiographic findings, bronchoscopy, and histopathology. Accurate diagnosis can be challenging due to the wide range of clinical presentations and while lung biopsy is not required, it may be necessary to establish an accurate diagnosis. Certain features of this case, but not all, initially fit with the diagnosis of HP. A home inspection revealed aspergillus and basidiospores and correlated with specific IgG antibodies found in the patient’s serum. Physical findings of dyspnea, wheeze, and crackles in conjunction with ground-glass opacities on chest CT seemed to fit the diagnosis of HP as well. However, bronchoalveolar lavage revealed only 11% lymphocytes whereas diagnostic criteria suggest a lymphocytosis of more than 20% with greater than 50% in most cases.7,8 Despite not fulfilling all diagnostic criteria, HP was the working diagnosis. Her parents meticulously cleaned the home and repeat testing of the environment was negative for all molds. She remained relatively asymptomatic over the subsequent 17 months until her symptoms returned.

A one-time recurrence of symptoms could have been attributed to either a flare of HP due to a mild exposure, or a respiratory viral illness. However, the severity of symptoms, combined with shorter asymptomatic intervals, necessitated further workup including repeat imaging. Of note, her chest CT, which originally demonstrated ground-glass opacities in the left lower lobe, no longer displayed any significant abnormalities other than atelectasis that could account for her current degree of hypoxemia. However, the radiographic improvement was inconsistent with her clinical deterioration, as she had diffuse crackles and displayed signs of a diffusion defect manifested by worsening hypoxemia with ambulation. Diagnosis in this setting required a lung biopsy, but the negative chest CT raised concern that a biopsy may be non-diagnostic. Lengthy discussions among the pulmonary service, the surgical service, and the family outlining the risks and benefits of a lung biopsy9 in the setting of the progressive respiratory disease combined with a negative chest CT ultimately favored proceeding to obtain tissue.

The clinical course for this patient does fit with the ultimate pathological diagnosis of PPL. The lymphatic system including capillaries, vessels, and nodes provides protective immunity.10 Disruptions of lymphatic function compromise immune function and result in lymphedema.10 In the lungs, this would manifest as pulmonary edema with subsequent hypoxemia. In this case, mild respiratory infections quickly escalated to severe hypoxemia. The initial wheeze and atelectasis were initially explained as caused by a viral illness. The crackles, profound hypoxemia, and favorable response to positive pressure ventilation and diuretics correlate with pulmonary edema driven by abnormal lymphatic function in the setting of an acute infection.

In discussion with the family, we initiated a trial of oral furosemide at the onset of respiratory distress. The goal was to treat pulmonary edema to improve oxygenation and minimize the need for supplemental oxygen, positive pressure ventilation, or hospital admission. Fortunately, this approach has been effective as she has treated several respiratory tract infections with early administration of furosemide and has not required hospital admission in over 2 years.

4 |. CONCLUSION

While this patient’s underlying lung pathology is rare, pulmonary edema is not, and she responded as expected to oral furosemide with a resolution of respiratory symptoms. In the absence of proven therapies for this rare condition, focusing on physiology has led to successful treatment.

Supplementary Material

CASE-BASED DYNAMIC LEARNING OF THE NEPPC RECURRENT HYPOXEMIA: WHEN CRACKLES CRACK THE CASE.

Podcast 1

(Radiologist) –: The chest radiograph demonstrates prominent perihilar interstitial opacities, peribronchial cuffing, and bilateral, bibasilar triangular and linear opacities suggestive of atelectasis. The trachea and mediastinal structures appear normal. This could be consistent with a viral pneumonia with subsegmental atelectasis or aspiration pneumonitis. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis most often presents with peripheral nodular opacities which we don’t see, however, non-specific appearances do occur.

(Pulmonologist # 1) –: This radiograph does not suggest significant hyperinflation, making obstructive diseases such as asthma, or a foreign body aspiration unlikely. Given the long period where she was asymptomatic, hypersensitivity pneumonitis could fit this picture.

(Radiologist) –: Although there is no sign of significant hyperinflation on this radiograph, we would need to obtain an expiratory view to be certain.

(Pulmonologist # 2) –: She was supposedly well for a year in between hospital admissions. I wonder if she ever fully recovered from her initial illness.

(Pulmonologist # 3) –: The acute onset of wheeze suggests an airway disease such as asthma, however, the chest radiograph is more consistent with parenchymal involvement.

Podcast 2

(Radiologist) –: This chest radiograph is similar to the previous film, with prominent perihilar interstitial markings. The bibasilar opacities are now more pronounced on the left side. There is no pneumothorax or pleural effusion. The lateral radiograph is more sensitive for assessment of hyperinflation and we do not see flattening of the diaphragms or significant air trapping.

(Pulmonologist # 1) –: The episodic nature of the respiratory events could suggest asthma. However, the physical examination and chest radiography are not consistent with an obstructive process. The bilateral opacities could represent pulmonary hemorrhage I suppose.

(Radiologist) –: Pulmonary hemorrhage could present with bilateral opacities, but findings on chest radiography are often non-specific. The radiograph could be consistent with viral bronchiolitis, but the clinical picture doesn’t fit. The peri-bronchial cuffing could be suggestive of hypersensitivity pneumonitis, but again there are no peripheral opacities. I also wonder about silent aspiration leading to atelectasis.

Podcast 3

(Pulmonologist #2) –: The differential diagnosis is still quite broad at this time. The intermittent nature of symptoms could point towards hypersensitivity pneumonitis, diffuse alveolar hemorrhage, or even vasculitis. Therefore, I would recommend a complete blood count with differential, a urinalysis, inflammatory markers, and a hypersensitivity panel.

(Pulmonologist #1) –: Although useful to obtain, a hypersensitivity panel is neither sensitive nor specific. Simply removing her from the home environment, and treating with systemic corticosteroids would be indicated if this were indeed hypersensitivity pneumonitis. This does not seem consistent with an acute bacterial infection; therefore, I would not recommend antibiotics.

(Pulmonologist #2) –: This is her third exacerbation without a clear etiology. I would be in favor of obtaining more data, before treating empirically with systemic steroids.

(Pulmonologist #3) –: I am struck that she is completely asymptomatic in between episodes of acute, severe, respiratory distress. The profound hypoxemia, and abnormal findings on the chest radiograph, are concerning. Therefore, I would recommend a computed tomography scan of the chest.

(Pulmonologist #1) –: The intermittent nature of acute respiratory distress and hypoxemia could fit with idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis, so bronchoscopy may eventually be necessary.

Podcast 4

(Radiologist) –: There is multi-focal, subsegmental, bilateral atelectasis and ground glass opacities in the left lower lobe. There is no lymphadenopathy, and the airway appears normal. I do not see centrilobular nodules, which are often found in hypersensitivity pneumonitis.

(Pulmonologist #3) –: I would have expected more parenchymal disease given the degree of hypoxemia. This does not provide a specific diagnosis, therefore, I would recommend bronchoscopy.

(Pulmonologist #2) –: Bronchoscopy would allow diagnostic testing for infection, hemorrhage, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, and anatomic abnormalities, such as a trachea-esophageal fistula.

Podcast 5

(Pulmonologist #2) –: She has rales and hypoxemia, which suggests an alveolar process. A repeat computed tomography scan of the chest would be warranted. I would also consider a lung biopsy given the frequency and severity of exacerbations without a clear diagnosis.

(Pulmonologist #3) –: The prior computed tomography scan of the chest does reveal ground glass opacities, but lacks the centrilobular nodules, and areas of decreased attenuation and vascularity often seen in hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Due to sampling error, idiopathic pulmonary hemosiderosis could still explain the intermittent exacerbations, despite the negative bronchoalveolar lavage. A shunt, as seen in arterio-venous malformations, could explain the desaturation with ambulation.

(Pulmonologist #1) –: She was well in between episodes, without evidence of exertional dyspnea, therefore a shunt would be less likely to explain her hypoxemia. I would start with repeating the chest computed tomography.

Podcast 6

(Pulmonologist #2) –: The hypoxemia is most likely secondary to a diffusion defect, as opposed to shunt physiology, given she denies exertional dyspnea when well. The frequency and severity of disease are progressing; therefore, I would recommend a lung biopsy now before she becomes too ill to obtain tissue.

(Pulmonologist #1) –: The unremarkable chest computed tomography gives me pause, but the clinical picture of significant hypoxemia, and progression of disease, requires further diagnostic intervention. Most likely she has diffuse disease given the degree of hypoxemia, otherwise there would be a significant abnormality seen on imaging.

(Pulmonologist #3) –: It would be important to discuss expectations with the family, as a lung biopsy in the setting of unremarkable imaging, may be non-diagnostic.

Footnotes

Case-Based Dynamic Learning of the NEPPC: The New England Pediatric Pulmonary Consortium (NEPPC) was founded in 1983. Physicians and trainees discuss and debate active cases involving pediatric patients with respiratory disease. The following dynamic case analysis based upon presentations at the NEPPC takes the reader through an iterative, experiential learning approach while promoting active learning. Challenge points allow for learner reflection and built in podcasts enable the reader to hear the consortium’s deliberations (participating institutions include: MassGeneral Hospital for Children, Boston Children’s Hospital, UMassMemorial Medical Center, Tufts Medical Center, Boston Medical Center, Mass Eye and Ear Infirmary, Dartmouth-Hitchcock).

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting Information may be found online in the supporting information tab for this article.

Audio files available for listening via links throughout the article. Written transcripts available as Supplementary Information.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gern JE. Viral respiratory infection and the link to asthma. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2008;27(10 Suppl):S97–S103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reiterer F, Grossauer K, Morris N, Uhrig S, Resch B. Congenital pulmonary lymphangiectasis. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2014;15(3): 275–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Esther CR Jr, Barker PM. Pulmonary lymphangiectasia: diagnosis and clinical course. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2004;38(4):308–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mettauer N, Agrawal S, Pierce C, Ashworth M, Petros A. Outcome of children with pulmonary lymphangiectasis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2009;44(4):351–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y, Allen KJ, Suaini NHA, McWilliam V, Peters RL, Koplin JJ. The global incidence and prevalence of anaphylaxis in children in the general population: a systematic review. Allergy. 2019;74(6): 1063–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Venkatesh P, Wild L. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis in children: clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. Paediatr Drugs. 2005;7(4): 235–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Selman M, Pardo A, King TE Jr. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: insights in diagnosis and pathobiology. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(4):314–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davidson KR, Ha DM, Schwarz MI, Chan ED. Bronchoalveolar lavage as diagnostic procedure: a review of known cellular and molecular findings in various lung diseases. J Thorac Dis. 2020;12(9): 4991–5019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fortmann C, Schwerk N, Wetzke M, Schukfeh N, Ure BM, Dingemann J. Diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic relevance of thoracoscopic lung biopsies in children. Pediatric Pulmonol. 2018;53: 948–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liao S, Padera TP. Lymphatic and immune regulation in health and disease. Lymphatic Res Biol. 2013;11(3):136–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.