Abstract

Background and study aims Simple hepatic cysts (SHCs) are usually asymptomatic and detected incidentally. However, larger cysts may present with clinical signs and require treatment such as percutaneous aspiration or surgery with non negligeable rate of recurrence. We report a series of 13 consecutive patients who underwent EUS-guided lumen-apposing metal stent (LAMS) drainage of SHCs of the right and left liver.

Patients and methods Nine men and four women, average age 71.9 years, underwent EUS-guided LAMS cyst drainage because of significant symptoms. At 1 month, LAMS was exchanged for a double pigtail stent (DPS), which was left in place for 3 months. Nine of the SHCs were located in the right liver and four in the left. The average diameter was 22.2 cm.

Results Thirteen LAMS were successful delivered in all patients. However only 12 of 13 (92.3 %) remained in place. In one case, the LAMS slipped out immediately and was promptly removed and the cyst treated percutaneously. One of 12 patients experienced bleeding, which was treated conservatively. In seven patients, the LAMS was exchanged for a DPS; in the other five, it was successfully left in place until the patients died, given their comorbidities. At 10.5 months of follow-up, none of the SHCs had recurred.

Conclusions EUS-guided LAMS drainage permits treatment of symptomatic SHCs without recurrence and with few adverse events. Comparative studies are needed to consider this approach as first intention.

Introduction

Simple hepatic cysts (SHCs) are the most commonly diagnosed benign liver lesions, with a prevalence of 18 % in the general population undergoing abdominal computed tomography (CT) scanning for unrelated pathologies 1 . They are usually asymptomatic and detected incidentally, given the development and widespread use of diagnostic modalities 2 . However, larger lesions may present with clinical signs such as abdominal pain, epigastric fullness, early satiety or even jaundice. Infrequently, internal hemorrhage, infection, or rapid enlargement can lead to symptoms and presentation for clinical evaluation 2 .

Asymptomatic SHCs do not require treatment. In contrast, symptomatic SHCs might be considered for percutaneous aspiration, aspiration followed by sclerotherapy or surgery 3 .

EUS-guided endoscopic internal drainage (EID) could be an attractive minimally invasive alternative to the percutaneous method 4 . In addition, recent development of dedicated lumen-apposing metal stents (LAMS) mounted on an electrocautery-enhanced delivery system have made possible a one-step procedure with formation of stable communication between the gastrointestinal lumen and the cystic abdominal cavity 5 . Here we report the first experience, to our knowledge, of 13 consecutive patients who underwent EUS-guided LAMS drainage of symptomatic SHCs of the right and left liver.

Patients and methods

Video 1 EUS-guided LAMS drainage without fluoroscopy of a huge hepatic cyst with release of clear liquid.

Video 2 Abdominal CT scan at 3 months showing complete healing of the cyst.

Data on all patients with symptomatic SHCs of the right or left liver lobe that had never been treated or recurred after surgical or percutaneous drainage and were treated with EUS-guided LAMS drainage ( Video 1 ) since January 2019 were retrospectively analyzed. The protocol was approved by the local hospitalʼs Medical Ethics Commission. As per protocol, LAMS was left in place for 4 weeks then exchanged for a double pigtail stent (DPS) ( Video 2 ), which was removed 3 months later. Thirteen patients (9 male) with an average age of 71.9 years (45–98) were included ( Table 1 ).

Table 1. Demographics and results.

| No | Sex (M/F) | Age (y) | Localization right/left liver | Diameter (cm) | Previous treatment (yes/no – surgical/radiological | EUS LAMS success (yes/no) | LAMS used (10/15/20 mm) | LAMS withdrawal (y/n) | Follow-up (mo) | Clinical sucess (yes/no) |

| 1 | M | 64 | R | 11 | N | Y | 10 | Y | 11 | Y |

| 2 | F | 58 | L | 18 | N | N | 10 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 3 | M | 88 | L | 13 | Y-S | Y | 15 | N | 13 | Y |

| 4 | M | 45 | R | 16 | Y-R | Y | 15 | Y | 9 | Y |

| 5 | M | 64 | R | 31 | Y-R | Y | 15 | Y | 21 | Y |

| 6 | F | 63 | R | 19 | N | Y | 15 | Y | 12 | Y |

| 7 | F | 81 | R | 20 | N | Y | 15 | N | 8 | Y |

| 8 | M | 77 | L | 17 | Y-S | Y | 15 | Y | 20 | Y |

| 9 | M | 90 | R | 25 | N | Y | 15 | N | 2 | Y |

| 10 | M | 98 | R | 40 | Y-R | Y | 20 | N | 7 | Y |

| 11 | M | 45 | R | 18 | N | Y | 15 | Y | 5 | Y |

| 12 | M | 84 | L | 33 | N | Y | 20 | N | 3 | Y |

| 13 | F | 78 | R | 28 | N | Y | 15 | Y | 16 | Y |

All patients presented with pain and vomiting; in addition, six of them presented with several sepsis episodes, two had jaundice due to the compression of the cyst on the biliary tree, and one developed pancreatitis. Three patients presented with ascites. Moreover, three patients presented with compression on the portal vein with thrombosis and they were treated with anticoagulant therapy. All of the patients were critically ill, presenting with severe malnutrition and sepsis at the time of endoscopic intervention. Cardiac failure with significant reduction of ejection fraction was present in three of them. In all patients, EUS-guided EID LAMS drainage was performed.

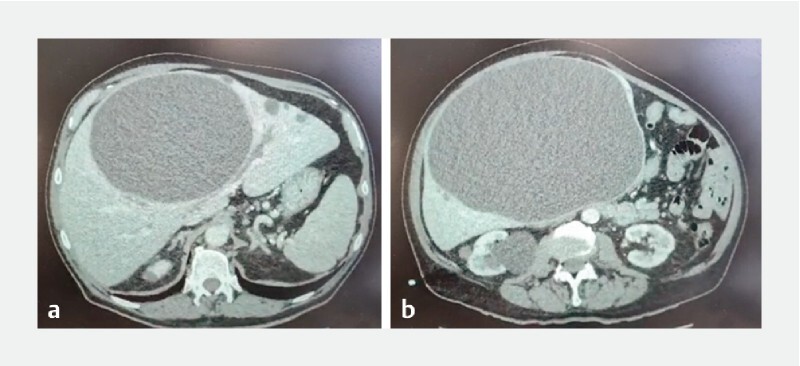

None of the patients enrolled in the protocol had a history of hepatobiliary endoscopy, surgery or trauma. Five patients presented with cyst recurrence, three after percutaneous drainage for an average of 90 days (15–120 days) and two after surgical fenestration at 8 months and 1 year, respectively. Nine cysts developed in the right liver lobe ( Fig. 1a, b ) and four in the left one. On average, the size of the cysts treated was 22.2 cm and the biggest was 40 cm (11–40 cm). They were unilocular with mostly liquid content with about 30 % of the total volume corpuscular and thick. A preoperative CT scan was performed in all patients as well as a postoperative one at 1 week and 3 weeks after LAMS placement. No signs of malignancy or of hydatid origin were identified.

Fig. 1 a, b.

CT scan showing right liver cyst > 20 cm in diameter.

The LAMS used was Hot Axios (Boston Scientific, Massachusetts, United States), two 20 × 10 mm, nine 15 × 10 mm, and two 10 × 10 mm. The technique used was the free-hand one. Once the cyst was identified, the best position was found to have the less tissue interposition, avoiding vessels and punching the cyst in its lowest part, trying to maximize, in this way, its emptying. A transesophageal approach was used in five cases, transgastric in five, and transduodenal in three of them. Fluoroscopy was not used in all cases. In all patients, aspiration of liquid was performed for cultural and biochemical examinations.

Results

Video 3 Endoscopic exploration of the cyst at 1 month and exchange of LAMS for double pigtails.

Technical success was defined as EUS identification through the upper gastrointestinal tract (esophagus, stomach, duodenum) and puncture of the cyst with deployment of LAMS and release of liquid in the gastrointestinal tract that enabled performance of bacteriology examinations. This was achieved in 92 % of cases (12 of 13). In one patient (second in the series), who underwent transesophageal drainage for a huge left liver cyst, after deployment of LAMS and aspiration of the liquid for bacteriology, the proximal esophageal flange slipped into the peritoneal cavity between the cardia and the left liver cyst. The access cautery defect was promptly catheterized (natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery), which would allow for the LAMS anchored in the hepatic parenchyma (cyst) to be found, grasped, and pulled with the aim of repositioning it. However, this was technically difficult, so the decision was made to remove the LAMS and close the esophageal defect with an Ovesco clip. Immediate drainage under radiologic guidance was performed. When the SHC recurred 7 months later, EUS-guided LAMS drainage again was performed and it was successful. Of note, this second drainage was not included in the series.

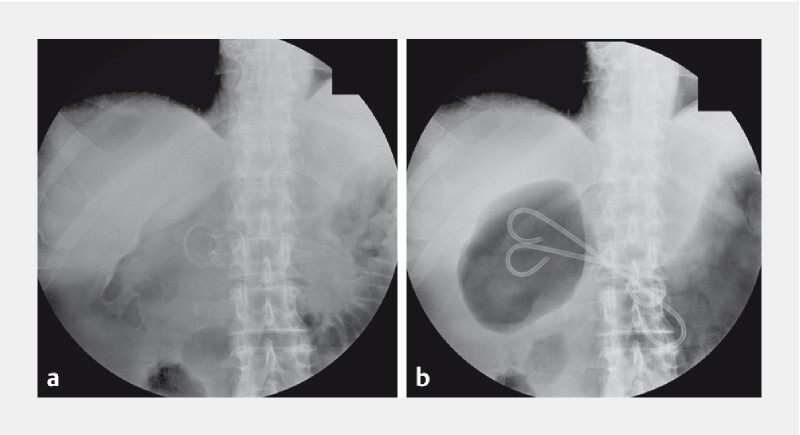

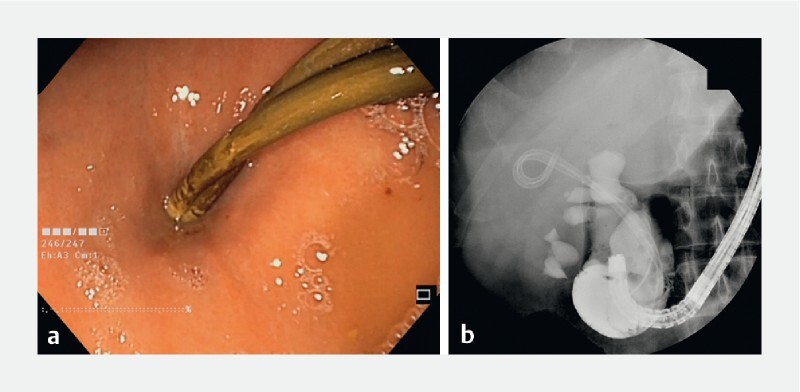

Drainage was successful in the other 12 patients (100 %) with discharge from the hospital within the next few days on a normal diet. All patients underwent a CT scan 7 to 21 days after the drainage and they were scheduled for LAMS removal at 4 weeks. In all 12 patients, symptoms improved and sepsis resolved ( Video 2 ); however, only seven patients (58.3 %) underwent endoscopic re-look in order to remove LAMS and replace it with a double pigtail stent ( Fig. 2a, b ) for 3 months ( Fig. 3a, b ). For the other five patients, considering their age, comorbidities, and successful recovery post procedure, LAMS was left in place until death, with an average follow-up of 9 months without adverse events (AEs) or inflammatory syndrome. At an average of 10.5 months (2–20) from EUS-guided LAMS drainage, none of the patients had a recurrence, including those with LAMS left in place (6.6; 2–13). None of the patients needed a necrosectomy or debridement; however, it was always possible to enter the cystic cavity through the LAMS at the 1-month control ( Video 3 ). Only one patient, 3 weeks after index EUS, presented melena with anemia without active bleeding on CT scan, which required a blood transfusion. LAMS was exchanged for a pigtail stent as scheduled, at 4 weeks. Follow-up was uneventful.

Fig. 2 a, b.

X-ray showing LAMS in place, and at 1 month exchanged for double pigtails.

Fig. 3 a.

Endoscopic appearance of transgastric pigtail in place at 3 months. b Upper swallow study through the scope showing no extravasation of medium contrast, meaning that the cyst is completely resolved. On x-ray, the cavity was not visible anymore at the level of the pigtails.

Discussion

SHCs are typically saccular, thin-walled masses with fluid-filled epithelial lined cavities. They arise from aberrant bile duct cells that originate during embryonic development. SHCs are usually < 1 cm and can grow up to 30 cm 6 .

While SHC are generally incidentally diagnosed and mainly asymptomatic, symptomatic ones need to be treated. The American College of Gastroenterology Clinical Guidelines recommend laparoscopic fenestration to deroof a cyst with or without omentoplasty as a first-line approach because it has a high success rate and is minimally invasive 3 ; however, the recurrence rate is 15 % to 20 % 7 . Other techniques have been described, such as percutaneous drainage, puncture, and sclerosis and/or injection of ethanol, with the same issue of recurrence as the surgical approach 7 .

In detail, percutaneous procedures for treatment of SHCs are particularly effective for immediate palliation of symptoms; however, they generally do not provide a long-term resolution because of the high rate of recurrence 8 and are often complicated by AEs such as leaks, skin inflammation, and accidental withdrawal of the drain. Radical surgical cyst excision seems to be curative without recurrence but is often characterized by a significant rate of morbidity and mortality 7 .

In recent years, LAMS, which originally were designed for drainage of transmural pancreatic fluid collections, have been used extensively for other indications. In fact, more recently other on-label and off-label indications have been proposed 9 , allowing drainage of almost all types of intra-abdominal (upper and lower gastrointestinal) collections and even performance of EUS-guided gastrointestinal anastomosis 10 11 , with very low rates of morbidity and mortality. Despite their worldwide use, there are few reports of LAMS EUS-guided drainage of symptomatic SHCs 12 , all of them performed on cysts located within the left liver lobe.

The choice of using LAMS as first intention, despite clear contents without debris, is related to avoiding leaks between the stomach and liver (cyst). With respiration, the liver and the stomach are mobile, so using pigtails as first intention guarantees less stability than LAMS, and could easily lead to a leak at the level of insertion with a risk of peritonitis. LAMS have been developed to avoid these kinds of AEs, as in digestive anastomosis. Once the fistula between the stomach and the liver cyst is epithelized (1 month later), a pigtail stent is useful to keep the internal drainage open, and it acts as a foreign body to promote granulation tissue formation and healing of the cyst (collapse of cavity and weld of wall).

However, abscess drainage 13 of the right liver lobe has already been attempted. Based on our experience, as long as the target is identified with EUS at a distance from the gastrointestinal wall of 1 cm maximum, it is always possible to proceed with a LAMS-guided procedure (anastomosis or drainage). In detail, the right liver is visualized transgastrically in pushed position or transbulbar and, despite the difficult location, generally the cysts are easily drainable due to their size, which cause their walls to be attached the gastrointestinal one. Infected cysts are the most common candidates for this kind of drainage, given that they can reach a size > 10 cm, increasing the likelihood of exclusion symptoms in adjacent organs 14 and making their treatment necessary. However, some concerns for EUS-guided liver cyst drainage persist, mainly in regard to risk of recurrence.

In this field, antibiotic treatment has been shown to have a treatment success rate of 20 %, which when combined with percutaneous drainage, increases to 65 %. Interestingly, antibiotics with surgery has a success rate of 100 % with an overall recurrence rate of 20 % 15 . In this consecutive series of patients, we had a 100 % success rate with combining antibiotics with LAMS drainage followed by pigtail stent positioning with no clinical recurrence at an average follow-up of 10.5 months, achieved with close monitoring of patient conditions after the procedure.

Our case series shows that persistent drainage, facilitated by positioning of double pigtail stents after LAMS removal, is enough to induce secondary collapse of pseudocavity, as shown in case of collection after EID of leaks and fistula after surgery, which have been successfully treated with double pigtail stents 16 . Recurrence after surgical deroofing, especially when cysts are located below the diaphragm, appear to be caused by partial occlusion by muscles during breath movements 7 . In our technique, slow and continuous drainage, facilitated by pigtail stent positioning, leads to collapse of the pseudocavity, which sticks to the pseudo-walls. Certainly, the large caliber of LAMS allows effective drainage of cysts even if there is some necrosis, such as in walled-off necrosis 17 . This is also the reason why EID with LAMS works better than percutaneous drainage, for which the usual drain caliber is 10F to 12F. Considering the rate of AEs, LAMS drainage is becoming the preferred option for gallbladder drainage, especially in unfit patients 18 . On the other hand, massive emptying of the cyst in the gastrointestinal cavity during the LAMS procedure (video) carries a potential orotracheal inhalation risk of the cystic content. Therefore, it needs to be performed carefully and in expert hands.

Interestingly, we reported just one failure (7.7 %), in a patient who needed drainage of a left liver cyst. The approach was through the intra-abdominal lower esophagus, which was probably the main reason for the failure. After a hand-free puncture and full deployment of LAMS with initial emptying of the cyst because of movements caused by respiration, the proximal flange slipped into the abdominal cavity, which resulted in stent migration. In this case and the previous one (the first), we used the 10x10 mm LAMS (despite the huge size of cyst, with pure liquid content), which may be have favored migration, given the cyst size. In all other patients, we used at least a 15-mm LAMS to obtain better anchoring, as we do routinely for EUS-guided gastro-entero-anastomosis, and we did not experience any AEs even with transesophageal drainage.

Conclusions

EUS-guided LAMS drainage permits to resolution of symptomatic SHCs without recurrence and with very few AEs. Comparative studies with interventional radiology and surgical management are necessary to consider this approach as first intention.

Footnotes

Competing interests The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Carrim Z I, Murchison J T. The prevalence of simple renal and hepatic cysts detected by spiral computed tomography. Clin Radiol. 2003;58:626–629. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(03)00165-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shimizu T, Yoshioka M, Kaneya Y et al. Management of simple hepatic cyst. J Nippon Med Sch. 2022;89:2–8. doi: 10.1272/jnms.JNMS.2022_89-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marrero J A, Ahn J, Rajender Reddy K et al. ACG clinical guideline: the diagnosis and management of focal liver lesions. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1328–1347. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donatelli G, Fuks D, Cereatti F et al. Endoscopic transmural management of abdominal fluid collection following gastrointestinal, bariatric, and hepato-bilio-pancreatic surgery. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:2281–2287. doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-5922-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Itoi T, Binmoeller K F, Itokawa F et al. First clinical experience using the AXIOS stent and delivery system for internal drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts and the gallbladder. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:AB330–AB331. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mavilia M G, Pakala T, Molina M et al. Differentiating cystic liver lesions: a review of imaging modalities, diagnosis and management. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2018;6:208–216. doi: 10.14218/JCTH.2017.00069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu S, Rao M, Pu Y et al. The efficacy of laparoscopic lauromacrogol sclerotherapy in the treatment of simple hepatic cysts located in posterior segments: a refined surgical approach. Ann Palliat Med. 2020;9:3462–3471. doi: 10.21037/apm-20-1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Erdogan D, van Delden O M, Rauws E A et al. Results of percutaneous sclerotherapy and surgical treatment in patients with symptomatic simple liver cysts and polycystic liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3095–3100. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i22.3095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mussetto A, Fugazza A, Fuccio L et al. Current uses and outcomes of lumen-apposing metal stents. Ann Gastroenterol. 2018;31:535–540. doi: 10.20524/aog.2018.0287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donatelli G, Cereatti F, Fazi M et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of intra-abdominal diverticular abscess. A case series. J Minim Access Surg. 2021;17:513–518. doi: 10.4103/jmas.JMAS_184_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donatelli G, Cereatti F, Spota A et al. Long-term placement of lumen-apposing metal stent after endoscopic ultrasound-guided duodeno- and jejunojejunal anastomosis for direct access to excluded jejunal limb. Endoscopy. 2021;53:293–297. doi: 10.1055/a-1223-2302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Molinario F, Rimbaş M, Pirozzi G A et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of a fungal liver abscess using a lumen-apposing metal stent: case report and literature review. Rom J Intern Med. 2021;59:93–98. doi: 10.2478/rjim-2020-0035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carbajo A Y, Brunie Vegas F J et al. Retrospective cohort study comparing endoscopic ultrasound-guided and percutaneous drainage of upper abdominal abscesses. Dig Endosc. 2019;31:431–438. doi: 10.1111/den.13342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kenzaka T, Sato Y, Nishisaki H. Giant infected hepatic cyst causing exclusion pancreatitis: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2022;10:2294–2300. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i7.2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lantinga M A, Geudens A, Gevers T J et al. Systematic review: the management of hepatic cyst infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:253–261. doi: 10.1111/apt.13047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Donatelli G, Dumont J L, Cereatti F et al. Treatment of leaks following sleeve gastrectomy by endoscopic internal drainage (EID) Obes Surg. 2015;25:1293–1301. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1675-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Muktesh G, Samanta J, Dhar J et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of patients with infected walled-off necrosis: Which stent to choose? Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2022 doi: 10.1097/SLE.0000000000001046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luk S W, Irani S, Krishnamoorthi R et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided gallbladder drainage versus percutaneous cholecystostomy for high-risk surgical patients with acute cholecystitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Endoscopy. 2019;51:722–732. doi: 10.1055/a-0929-6603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]