Abstract

This study developed, optimized, characterized, and evaluated bioadhesive, hot-melt extruded (HME), extended-release ocular inserts containing ciprofloxacin hydrochloride (CIP-HCL) to improve the therapeutic outcomes of ocular bacterial infections. The inserts were fabricated with FDA-approved biocompatible, biodegradable, and bioadhesive polymers that were tuned in different ratios to achieve a sustained release profile. The results revealed an inverse relationship between the Klucel™ hydroxypropyl cellulose (HPC, 140,000 Da) concentration and drug release and extended-release profile over 24 h. The CIP-HCL-HME inserts presented stable drug content, thermal behavior, surface pH, and release profiles over three months of room-temperature storage and demonstrated adequate mucoadhesive strength. SEM micrographs revealed a smooth surface. Bacterial growth was not observed on the samples during the in vitro release experiment (0.5–24 h), indicating that a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 90 against Pseudomonas aeruginosa was achieved. Ex vivo transcorneal permeation studies using excised rabbit corneas revealed that the prepared ocular inserts prolonged the transcorneal flux of the drug compared to commercial eye drops and immediate-release inserts and could reduce the administration frequency to once daily. Therefore, the inserts could increase patient compliance and exhibited prolonged antibacterial activity and thus could provide better therapeutic outcomes against ocular bacterial infections.

Keywords: Experimental design, Klucel™ JXF, Ocular insert, Hot-melt extrusion, Ciprofloxacin, Ocular bacterial infection, Sustained release

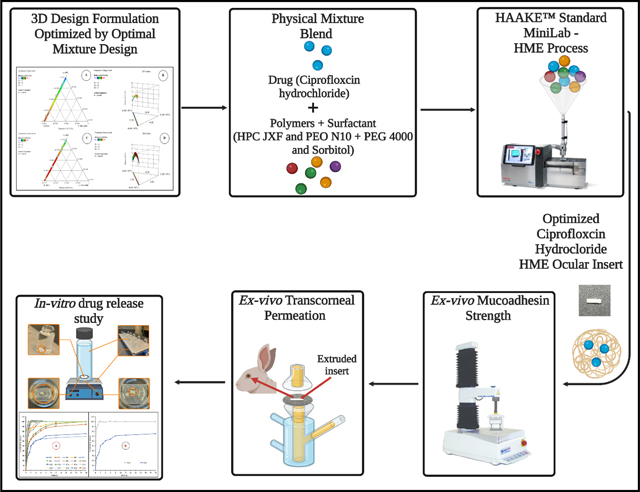

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Ocular bacterial infections can manifest in different ways; however, the most common are keratitis, conjunctivitis, blepharitis, and endophthalmitis (Kowalski and Dhaliwal, 2005; Teweldemedhin et al., 2017). Bacterial keratitis (BK) is a devastatingly painful corneal inflammation caused by bacterial infection, and if left without proper treatment, it can progress to corneal ulceration, bacterial endophthalmitis, and serious irreversible visual impairment (Bertino, 2009a). Although the exact prevalence of BK is unknown, US estimates range from 25,000 to 71,000 cases each year while the global rates may exceed 2.0–3.5 million cases (Hyndiuk et al., 1996a; Liu et al., 2017a). Bacterial blepharitis (BB) is an inflammation of the eyelid margin caused by bacteria, and it can result in blepharoconjunctivitis after extension of the conjunctiva (Kowalski and Dhaliwal, 2005). In 2009, ophthalmologists and optometrists in the US reported that blepharitis affected 37% and 47% of their patients, respectively (Balguri et al., 2017a). Bacterial endophthalmitis (BE) is a sight-threatening inflammatory reaction caused by bacteria inside the eye globe that involves the vitreous and/or aqueous humor (LeBel, 1988). Reports have indicated that outpatient treatments for infectious endophthalmitis resulted in savings of $1.5 to $7.8 million per year in the USA (LeBel, 1988). The most common bacterial pathogens isolated from these ocular bacterial infections are Staphylococcus aureus (gram positive) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (gram negative) (Kowalski and Dhaliwal, 2005; Teweldemedhin et al., 2017b).

Ciprofloxacin (CIP) is a second-generation bactericidal broad-spectrum fluoroquinolone antibiotic (Youssef et al., 2022a) that inhibits DNA replication by inhibiting bacterial DNA topoisomerase and DNA-gyrase. CIP is an options considered during the treatment of BK (Hyndiuk et al., 1996b), BE (Liu et al., 2017b), BC (Friedlaender, 1995a), and many other bacterial infections of the eye, including BB (Balguri et al., 2017b), because of its broad-spectrum, safety, and patient tolerability. Among quinolones, CIP is the most effective against Pseudomonas aeruginosa (LeBel, 1988). Moreover, many in vitro and animal studies have reported superior cure rates for both methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant S. aureus infections (Righter, 1987). CIP is available commercially as ophthalmic solution eyedrops and ointments at 0.3% w/v concentration for topical ocular applications (Youssef et al., 2021a). However, the use of these eyedrops present several challenges, such as high pre-corneal loss, short residence time, and nasolacrimal drainage, which leads to poor ocular bioavailability following topical application. All of these challenges necessitate frequent administration, which leads to reduced patient compliance. Moreover, the ointment dosage form is associated with many side effects, including blurred vision, redness, itching, eye discomfort, and eye dryness (Youssef et al., 2021a). Effective early treatment of different ocular bacterial infections can prevent the progression to corneal perforation, endophthalmitis, or blindness (Bertino, 2009b; Pachigolla et al., 2007).

Ocular inserts are solid or semi-solid drug-containing polymeric matrices that are usually placed in the cul de sac, conjunctiva, or upper fornix (Thakkar et al., 2021). This dosage form is intended for prolonged delivery to reduce the frequency of administration and potentially decrease systemic exposure and toxicity (Polat et al., 2020; Thakkar et al., 2021). Moreover, the addition of preservatives can be prevented, thereby preventing adverse side effects (Thakkar et al., 2021). Furthermore, inserts can be tailored to obtain several desired characteristics by selecting appropriate biocompatible, biodegradable, mucoadhesive, and immediate- or sustained-release polymers (Thakkar et al., 2021).

The solvent casting process was used to prepare the majority of the ocular inserts; however, trace levels of the remaining solvent may pose a high ocular safety risk (Balguri et al., 2017c). Furthermore, this approach has scalability issues, shows batch-to-batch variations, and suffers from air entrapment and a time-consuming solvent removal process (Bhagurkar et al., 2019; Thakkar et al., 2021). The hot-melt extrusion (HME) technique can overcome these disadvantages while maintaining all other advantages of inserts because it is a solvent-free and easily scalable continuous process with relatively high throughput rates, and it is an economical and versatile technology (Thakkar et al., 2021). Recently, HME technology has been established for the production of a wide range of oral (Narala et al., 2022), ocular (Thakkar et al., 2021), dermal (Shettar et al., 2021), and parenteral formulations (Repka et al., 2008). HME has been used in many successful pharmaceutical research applications, including improving the solubility of poorly water-soluble compounds for transdermal, transmucosal, and topical drug delivery systems (Thakkar et al., 2021, 2020). Moreover, two FDA-approved ophthalmic inserts prepared using HME are currently marketed: Lacrisert®, a topical insert for dry eye symptoms, and Ozurdex®, an intravitreal implant for macular edema following branch retinal vein occlusion or central retinal vein occlusion (Thakkar et al., 2021).

The current study aimed to develop a sustained-release CIP ocular insert using HME technology based on the design of experiment (DoE) approach, which could overcome the drawbacks of rudimentary approaches for the fabrication of ocular inserts. Furthermore, these HME inserts could enhance ocular retention, improve bioavailability, reduce the once-a-day administration frequency, and serve as an alternative delivery system for currently marketed formulations to manage different ocular bacterial infections.

2. Materials and methods:

2.1. Materials

Ciprofloxacin hydrochloride (CIP-HCL) was purchased from Cayman Chemical Company (Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Klucel™ hydroxypropyl cellulose (HPC), JXF grade, was kindly gifted by Ashland (Ashland Inc., Bridgewater, NJ, USA). POLYOX™ WSR N10 (PEO) was generously gifted by Colorcon, Inc. (Irvine, CA, USA). Polyethylene glycol 4000 (PEG 4000) was purchased from Fischer Chemicals (Hampton, NH, USA). Parteck® SI 150 (sorbitol) was generously gifted by Millipore Sigma (Burlington, MA, USA). Other chemicals, such as solvents and reagents, were of analytical grade and obtained from Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ, USA). The centrifuge tubes (50 mL), HPLC vials, and glass vials were purchased from Fischer Scientific (Hampton, NH, USA). Millex® syringe nylon membrane filters (0.45 μm) were purchased from MilliporeSigma (St. Louis, MO, USA).

2.1.1. Biological tissues and samples

The whole eyes globe of a mixed gender group of albino New Zealand rabbits (4.75–5.75 lbs and 8–12 weeks of age) were purchased from Pel-Freez Biologicals (Rogers, AR, USA). The eyes were shipped overnight under cold conditions in Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS). Corneas were carefully excised and used for permeation studies immediately upon arrival. Microbial strains were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA).

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. High performance liquid chromatography

CIP-HCL was quantified using the validated reversed-phase high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method described in the CIP-HCL USP monograph. The analysis was performed using a Waters HPLC system (Waters Corp., Milford, MA, USA) equipped with an autosampler, UV/VIS detector, and Empower software (Waters Inc., Mount Holly, NJ, USA). Chromatographic separation was achieved on a Waters Symmetry® C18 column (150 mm × 4.6 mm, 5.0 μm), with the detection wavelength set to 278 nm. The mobile phase consisted of acetonitrile and 25 mM phosphoric acid solution (pH of 3.0 ± 0.1), which was mixed in a v/v ratio of 13:87% and pumped isocratically through the instrument. The pH of the mobile phase was adjusted using triethylamine (TEA). The flow rate was set to 1.2 mL/min with a run time of 10 min, and the injection volume was 20 μL. The method was linear over a CIP-HCL concentration range of 1–100 μg/mL.

2.2.2. Preparation of the physical mixture

The physical mixture (PM) blends containing polymers, plasticizers, and CIP-HCL were prepared at different ratios, as shown in Table 2. All the powders were individually sieved through mesh with a U.S. sieve size of 30 before mixing using the geometric dilution method with a mortar and pestle for 5 min. The drug, polymers, and plasticizers were blended in equal quantities before dilution with polymers to obtain the optimal drug/carrier ratio. The PMs were then tumble-mixed in a V-shaped blender (MaxiBlend™; GlobePharma, NJ, USA) for 10 min at 25 rpm, stored in polyethylene bags, and placed in a desiccator at room temperature to prevent moisture adsorption.

Table 2.

Composition of ciprofloxacin hydrochloride ocular inserts according to the I-optimal mixture design.

| Formulation code | Run | Composition (% w/w) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPC JXF | PEO N10 | PEG 4000 | Sorbitol | ||

| F1 | 1 | 62.6667 | 31.3333 | 0 | 0 |

| F2 | 2 | 0 | 87 | 3 | 4 |

| F3 | 3 | 30.3333 | 61.6667 | 2 | 0 |

| F4 | 4 | 45.5 | 45.5 | 0 | 3 |

| F5 | 5 | 28.3333 | 56.6667 | 3 | 6 |

| F6 | 6 | 0 | 87 | 1 | 6 |

| F7 | 7 | 0 | 87 | 1 | 6 |

| F8 | 8 | 45.5 | 45.5 | 0 | 3 |

| F9 | 9 | 66.375 | 22.375 | 0.75 | 4.5 |

| F10 | 10 | 0 | 94 | 0 | 0 |

| F11 | 11 | 88 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| F12 | 12 | 88 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| F13 | 13 | 94 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| F14 | 14 | 56.6667 | 28.3333 | 3 | 6 |

| F15 | 15 | 22.375 | 69.375 | 0.75 | 1.5 |

| F16 | 16 | 0 | 87 | 3 | 4 |

| F17 | 17 | 42.5 | 42.5 | 3 | 6 |

| F18 | 18 | 30.3333 | 61.6667 | 2 | 0 |

| F19 | 19 | 91 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| F20 | 20 | 88 | 0 | 2 | 4 |

2.2.3. Mixture design for the development and optimization of CIP-HCL ocular inserts

The DOE approach was employed in this study to examine the relationship between the selected independent factors and drug release at 0.5 h and 6 h as a response across the entire design space. Statistical optimization is an efficient tool for exploring the relationship between various independent formulation variables to obtain the desired response. Among several models, the I-optimal point-exchange randomized mixture design was selected to study the interactions between the four formulation ingredients as independent variables. Four factors (independent variables), namely, the weight ratio percentage of hydroxypropyl cellulose (HPC, A), polyethylene oxide (PEO, B), polyethylene glycol 4000 (PEG 4000, C), and sorbitol (D), were selected as presented in Table 1. The levels of independent variables were chosen based on a literature review and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) inactive ingredients database (Table 1). All four excipients were randomly displayed in several ratios, with a total % equal to 94% and a drug load of 6% w/w within all formulations. Twenty experimental runs were generated using Design-Expert® software version 12 (StatEase Inc., Minnesota, USA), as summarized in Table 2. The % release at 0.5 h (R1) and 6 h (R2) was the dependent variable for the optimization of the developed ocular inserts.

Table 1.

Experimental mixture design (independent variables and selected responses).

| Independent factors (% w/w) | Levels | |

|---|---|---|

| −1 (Low) | +1 (High) | |

| A – HPC | 0 | 94 |

| B – PEO | 0 | 94 |

| C – PEG 4000 | 0 | 3 |

| D – Sorbitol | 0 | 6 |

| Dependent factors (%) | ||

| R1 – release at 0.5 h | R2 – release at 6 h | |

The adjusted and predicted coefficients of determination (R2) and predicted residual sum of squares (PRESS) values were calculated using the software from the sequential model comparison to select the best model for fitting among different software models. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) and model F value assessments were performed on the software-selected fitting model to determine the significance of each model term along with the interaction between different model terms. Contour plots and response surfaces were generated to understand the main and interaction effects of the responses. Moreover, numerical optimization was performed to achieve the study goals with target release values of 0.5 and 6 h.

2.2.4. Control formulation

Immediate-release insert (CIP-HCL-HME-IR)

The F15 insert was considered the immediate-release insert, and it was prepared according to the composition of optimized CIP-HCL-HME inserts with low % w/w of the HPC polymer, and the PEO polymer accounted for the bulk of the insert. CIP-HCL-HME-IR was used as a control formulation for ex vivo permeation and in vitro release studies because it showed the highest value for drug release for both dependent variables.

CIP hydrochloride ophthalmic solution control (CIP-HCL-C)

CIP-HCL ophthalmic solution (0.3% as a base, Leading Pharma LLC, NJ, USA; lot # 018B041) was used as a control formulation for the ex vivo permeation and antimicrobial testing studies.

2.2.5. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)

A TA DSC 25 instrument (TA Instruments, Newcastle, DE, USA) was used to evaluate the thermal behavior of the active pure excipients, PMs, and CIP-HCL-HME-IR and optimized CIP-HCL-HME inserts. The samples were scanned in the range of 25 °C to 200 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min under ultra-purified nitrogen atmosphere (50 mL/min). The samples (5–8 mg) were loaded into hermetically sealed aluminum pans (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA), and an empty pan was used as a reference. The results were analyzed using Trios software (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA).

2.2.6. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy

The IR spectra of the samples (pure drug, excipients, PM, and optimized insert) were collected in the wavenumber range 650–4000 cm−1 using a Cary-630 FTIR spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The bench was equipped with MIRacle Attenuated Total Reflection (Pike Technologies MIRacle ATR, Madison, WI, USA), which was fitted with a single-bounce diamond-coated ZnSe internal reflection element.

2.2.7. Hot-melt extrusion process

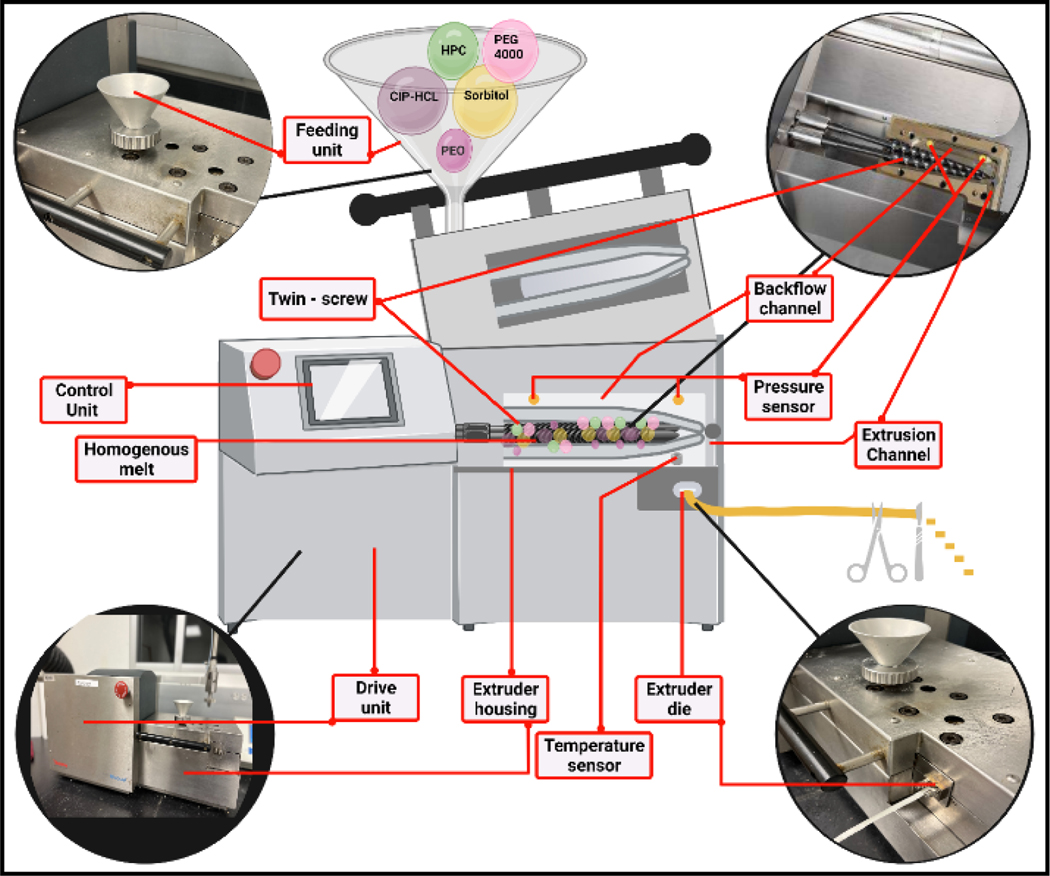

The mixture blends were individually fed into the hopper of a counter-rotating twin-screw extruder (Haake Minilab, Thermo Fisher™ Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at a steady rate (~ 0.4 g/min) (Fig. 1). The width of the inserts was controlled using a 2.0 mm die (rectangular shape) mounted on the Haake extruder at a screw speed of 50 rpm. The HME process temperature was in the range of 90 to 140 °C, based on the polymeric carrier ratio of each formulation, as shown in Table 3. The inserts (cut) were stored in polyethylene bags and placed in a desiccator at room temperature to prevent the adsorption of moisture.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the Haake Minilab Thermo Fisher Scientific® twin-screw extruder used for the fabrication of ciprofloxacin hydrochloride ocular inserts.

Table 3.

HME processing parameters during the fabrication of ciprofloxacin hydrochloride ocular inserts.

| Code | Process temperature (°C) | Residence time (min) | Feed rate (g/min) | Screw speed (rpm) | Torque (Ncm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 90 | 3.36 | 0.43 | 50 | 53 |

| F2 | 90 | 3.53 | 0.33 | 50 | 22 |

| F3 | 90 | 3.20 | 0.36 | 50 | 28 |

| F4 | 90 | 3.41 | 0.35 | 50 | 25 |

| F5 | 90 | 4.52 | 0.42 | 50 | 19 |

| F6 | 90 | 4.23 | 0.38 | 50 | 20 |

| F7 | 90 | 4.23 | 0.38 | 50 | 20 |

| F8 | 90 | 3.41 | 0.35 | 50 | 25 |

| F9 | 90 | 4.58 | 0.40 | 50 | 26 |

| F10 | 90 | 4.36 | 0.40 | 50 | 30 |

| F11 | 120 | 4.29 | 0.44 | 50 | 33 |

| F12 | 120 | 4.13 | 0.35 | 50 | 43 |

| F13 | 140 | 3.44 | 0.36 | 50 | 66 |

| F14 | 90 | 4.38 | 0.39 | 50 | 25 |

| F15 | 90 | 4.39 | 0.38 | 50 | 27 |

| F16 | 90 | 3.53 | 0.36 | 50 | 22 |

| F17 | 90 | 4.22 | 0.41 | 50 | 19 |

| F18 | 90 | 3.20 | 0.36 | 50 | 28 |

| F19 | 140 | 3.33 | 0.42 | 50 | 21 |

| F20 | 140 | 4.29 | 0.44 | 50 | 33 |

2.2.8. Evaluation of CIP-HCL-HME ocular inserts

The inserts were evaluated based on their appearance, weight variation, surface pH, uniform thickness, drug content, swelling index, thermal analysis, drug–excipient compatibility, moisture loss and absorption, surface morphology, mucoadhesive strength, in vitro release, antimicrobial efficacy, ex vivo transcorneal permeation, and stability.

Thickness and weight

The thickness of the HME extruded film was measured in three different regions using a Thermo Fischer Scientific digital caliper (0–150 mm). The HME extruded film was pre-marked for 1 mm cuts using the abovementioned digital caliper before cutting using a scalpel blade. The inserts were weighed individually on a calibrated Mettler Toledo excellence balance. All measurements were performed in triplicate.

Surface pH

The inserts were soaked in phosphate buffered saline (PBS, 3.0 mL, pH 7.4 ± 0.1) in glass vials prior to measurement, and then pH was measured using a Mettler Toledo pH meter (FiveEasy™, Columbus, OH, USA) equipped with an Inlab® Micro Pro-ISM probe. The pH meter was calibrated using different buffers with known pH values of 4.01, 7.00, and 10.01 (Orion™ Standard All-in-One™ pH Buffer Kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Chelmsford, MA, USA). The pH measurements were performed in triplicate.

Drug content

The ocular inserts (~5 mg) were individually dissolved in a mixture of acetonitrile and 25 mM phosphoric acid solution (pH 2.0 ± 0.1, adjusted with TEA) mixed in a v/v ratio of 13:87% into a volumetric flask (10 mL). The extract was vortexed for 3 min at 2000 rpm and sonicated (Bransonic® Ultrasonic Cleaner, USA) for 5 min. The mixtures were then centrifuged using AccuSpin™ 3R centrifuge (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 10,000 rpm for 15 min. The supernatant was passed through a nylon membrane filter with a 0.45-μm pore size and analyzed for the CIP-HCL content using the HPLC method described above.

Swelling index

The swelling index of both ocular inserts (immediate and optimized) was determined for each formulation. Each insert was weighed initially before being placed into an isotonic phosphate-buffer saline (IPBS, pH 7.4, 34 ± 0.2 °C) in glass vials. The insert was removed from the IPBS at scheduled time points during the experimental period. Excess IPBS medium was removed with the aid of filter paper from the surface of the insert before reweighing. The swelling index was determined for three randomly selected ocular inserts from each batch, and the swelling index (%) was calculated based on the following equation (Shadambikar et al., 2021a):

Moisture absorption (%)

The initial weights of the three optimized CIP-HCL-HME ocular inserts were recorded before they were placed in a desiccator for three days with the hydrated form of aluminum chloride for the % moisture absorption calculation. After the testing period, the inserts were reweighed and the moisture absorption (%) was calculated using the following formula (Khurana et al., 2012):

Moisture loss (%)

The initial weights of the three optimized CIP-HCL-HME ocular inserts were recorded before being placed in a desiccator for three days containing anhydrous calcium chloride as the highly hygroscopic material for calculating moisture loss. After the testing period, the inserts were reweighed and the moisture loss (%) was calculated using the following formula (Khurana et al., 2012):

2.2.9. Evaluation of antimicrobial activity

The antibacterial activity of CIP-HCl within the collected release samples was evaluated against Pseudomonas aeruginosa (ATCC BAA-2018) obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed according to a modified version of the guidelines of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI, 2012). Samples were diluted using cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth (pH 7.3). The diluted samples (10 μL) were then transferred to microdilution plates (96 well). Inocula were prepared by correcting the OD630 of the bacterial suspensions in the incubation broth to provide the recommended inocula, as per the CLSI protocol. Subsequently, 5.0% Alamar Blue™ was added to the final assay plate. CIP-HCL solution in release medium was used as a positive control, while the IPBS (pH 7.4) containing 2.5% randomly methylated beta-cyclodextrin (RMβCD) served as a negative control because it was the release medium. The optical density was measured for each of the panel wells using a Bio-Tek plate reader at 544 ex/590 em before and after incubation at 35 °C for 24 h. The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was determined for all tested formulations and defined as the lowest test CIP-HCL concentration that resulted in no visual growth. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

2.2.10. Ex vivo bioadhesive strength

Isolated rabbit corneas were used to evaluate the bioadhesive strength of the optimized inserts (Fig. 2). Bioadhesion testing was performed using a texture analyzer (TA.XT2i, Stable Micro Systems, Texture Technologies Corporation, London, UK) with a 50-N load cell equipped with a TA-57R (diameter: 7 mm) probe. The ocular inserts (2 × 1 mm) were attached to the base of the testing probe using double-face adhesive tape, and the base was fixed to the mobile arm of the TA-XT2i, as shown in Fig. 2. The corneas were mounted between the two parts of the tissue holder, with the epithelial surface facing the probe to which the formulation was attached (Fig. 2). The tissue holder was loaded in a beaker (500 mL) filled with IPBS (pH 7.4), maintained at 34.0 ± 0.5 °C. Simulated tear fluid (STF, 10 μL) was added to the ocular surface using an Eppendorf® pipette. STF with a pH of 7.0 ± 0.2 was prepared by dissolving calcium chloride (0.0084%), sodium chloride (0.678%), potassium chloride (0.138%), and sodium bicarbonate (0.218%) in Milli-Q water (Youssef et al., 2020). The following parameters were set: applied force (5.0 N), pre-test speed (0.1 mm/s), test speed (1.0 mm/s), pre-test speed (0.1 mm/s), and contact time (60 and 180 sec). The maximum force necessary to detach the probe from the ocular surface (Fmax) was determined using the Exponent software (version 6.1.5.0, Stable Micro Systems, Godalming, UK). All measurements were performed in triplicates.

Figure 2.

Bioadhesive strength measurement of the ciprofloxacin hydrochloride hot-melt extruded insert on excised rabbit corneal using a texture analyzer.

2.2.11. In vitro drug release

The accurately weighed inserts were sandwiched between the bottom of 20 mL glass scintillation vials and a stainless-steel mesh (#10), and a magnetic stirrer bar rotated above the mesh screen. Then, each vial was filled with IPBS (pH 7.4, 10 mL) containing 2.5% RMβCD as the release medium. The vials were maintained under continuous magnetic stirring at 34 ± 0.2 °C. Samples (0.5 mL) were collected at regular time points and replaced with an equal volume of the release medium. The release medium was selected based on previous studies (Youssef et al., 2021a). The concentration of CIP-HCl in the samples was quantified using the HPLC method described above. The collected release data were fitted using DDSolver software for modeling and comparisons of the drug dissolution profiles based on the following equations:

where Q0 and Q represent the initial drug content at the time t0 and drug content remaining at time t, respectively; Zero-order model: % drug released vs. time; First-order model: amount of drug remaining vs. time; Higuchi model: % drug released vs. square root of time; and Korsmeyer–Peppas model: log% drug released vs. log time.

2.2.12. Stability studies

The optimized formulation was investigated for physicochemical stability after storage under room temperature conditions (25 ± 2 °C) for 90 d. The formulation was packed in glass scintillation vials and loaded into a Thermo Scientific Heratherm compact incubator. The samples were evaluated at scheduled time points for any changes in drug content, release profile, and thermal behavior.

2.2.13. Ex vivo transcorneal permeation

The studies were conducted according to our previously validated protocols (Majumdar et al., 2010). Ex vivo permeation testing was performed using a vertical Franz diffusion apparatus (PermeGear® Inc., Hellertown, PA, USA) on excised rabbit corneas isolated from whole eyes. Each cornea was mounted between the two compartments of each vertical Franz diffusion cell (spherical joint) with the corneal epithelium facing the donor compartment, which contained the test or control formulations. The test formulation was the optimized CIP-HCL insert (approximately 5 mg), while the controls consisted of the CIP-HCl-HME-IR insert (approximately 5 mg) and marketed formulation (100 μL). The receiver compartment, which contained a solution of 2.5% RMβCD in IPBS (pH 7.4), was maintained under continuous magnetic stirring and 34.0 ± 2.0 °C with the aid of a circulating water bath. Aliquots were removed from the receiver compartment at predetermined time points and replaced with an equal volume of fresh medium. The samples were analyzed for CIP-HCl using the HPLC method described above. The cumulative amount of drug permeation (Qn) and steady-state flux (Jss) were calculated using the following equations:

where n is the sample-withdrawing time point, Vr is the volume in the receiver compartment (5.0 mL), VS is the volume of the aliquot collected at the nth time point (0.5 mL), and Cr(n) is the drug concentration in the receiver compartment at the nth time point (μg/mL).

where dQ/dt) is the rate of transcorneal permeation (slope of Qn versus the time plot), and A is the effective area for drug permeation (0.64 cm2).

2.2.14. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The surface morphology of the pure drug, PM, and optimized CIP-HCL-HME insert formulations was investigated using a JSM-7200FLV scanning electron microscope (JOEL, Peabody, MA, USA) at an accelerating voltage of 5 kV. All samples were arranged on SEM stubs and attached with double-sided tape. Before imaging, the samples were sputter-coated with platinum in an argon environment using a fully automated Denton Desk V TSC sputter coater (Denton Vacuum, Moorestown, NJ, USA).

2.2.15. Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation. Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 28 (IBM, SPSS, Ithaca, NY, USA) was used to perform the statistical analyses. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Formulation development

CIP-HCL-HME inserts were successfully fabricated for both immediate and sustained release using biodegradable polymers (PEO and HPC) and plasticizers (PEG 4000 and sorbitol). PEO is one of the best candidates as a polymeric matrix for the HME process and ocular drug delivery because of its nonionic, biodegradable, biocompatible, and bioadhesive properties, low toxicity, excellent pliability, thermogelation characteristics, and low melting point of 65 °C (Balguri et al., 2017c; Li et al., 2006). HPC is a thermoplastic nonionic cellulose ether polymer that is pH-independent, biodegradable, biocompatible, bioadhesive, relatively nontoxic, pliable, and extrudable and an excellent film component (Gupta et al., 2021). Moreover, the low glass transition temperature (−25 °C – 0 °C) of HPC provides low melt viscosity and fast melt flow properties during extrusion (Picker-Freyer and Dürig, 2007) (Pereira et al., 2020a). PEG was anticipated to improve the flowability of the mixtures because of its low melt viscosity (Ahmad et al., 2012), thereby enabling increased mechanical flexibility of the inserts. However, sorbitol has also been utilized to increase extrudability (Pereira et al., 2020b). CIP eyedrop dosing of 2 drops was applied to the conjunctival sac while the patient was awake for different types of infections (Youssef et al., 2022b). Thus, the drug load was maintained at 6% w/w in all inserts to ensure that the concentration of the CIP base was equivalent to that of the marketed formulation dose.

3.1.1. Preparation of CIP-HCL-HME inserts

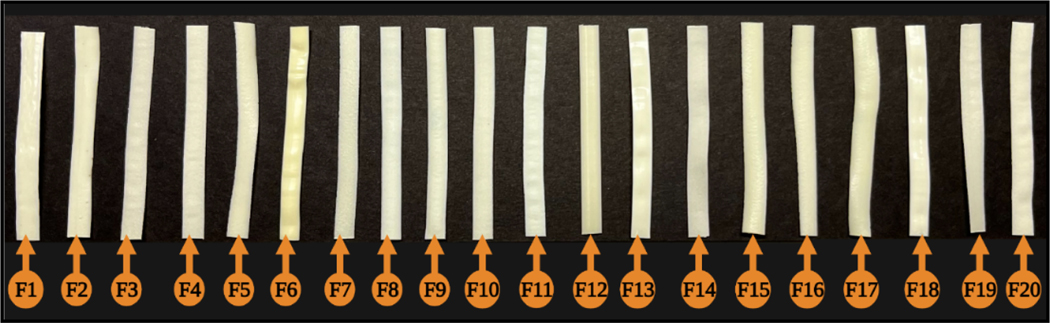

All CIP-HCL extruded inserts were successfully fabricated using a Haake Minilab co-rotating twin-screw extruder (Fig. 1). Both the HPC and PEO polymers were exposed to heat and shearing stresses during the HME process. Temperature may contribute to polymer chain depolymerization, whereas screw shearing can cause chain scission (Repka and McGinity, 2000). The HME process has a temperature range of 90–140 °C. Because of the high viscosity of the polymer melt, the films with a high % of HPC (≥ 88%, F13 and F19–20) could not be extruded below 120 °C without PEO and a high % plasticizer. Moreover, HPC-containing formulations without PEO or plasticizers demonstrated high torque values (66 Ncm) within the extruder. Furthermore, PEO had a good plasticizing effect and helped to process formulations at low temperature (90 °C). The processing residence time for all formulations was less than 5 min. The extruded films were labelled and sealed in 5 ml polyethylene bags (25 °C, 50% relative humidity). Random samples of extruded films were obtained for testing and further evaluation.

3.2. Statistical analysis of the applied mixture design

Mixture design was performed in this study to analyze the effect of the selected independent variables on the in vitro release behavior of the developed CIP-HCL ocular inserts. The observed responses generated by the software for the 20 experimental runs are listed in Table 4. The first step for response optimization was to select the model that best described and fit the data. Therefore, a sequential model comparison was performed to analyze the results for the response variables, as presented in Table 5. The % drug release data at the selected time points were fit to linear, quadratic, special cubic, and cubic models to select the best model for determining the relationship between input factors and responses. Higher-order models, such as special cubic and cubic, were aliased (i.e., the number of software-selected terms in the model was larger than the number of unique points in the design) and thus were not suitable for response prediction during the optimization of the inserts in the current investigation. Based on the significant p-values obtained from the sequential model sum of squares analysis, the best fit was chosen for each response. The quadratic model showed the best fit for R1 and R2 when compared with the other models, as evidenced by the large predicted R2 values.

Table 4.

Generated trial formulations and their observed responses according to the mixture design.

| Code | Run | Response (%) | Code | Run | Response (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Release at 0.5 h | Release at 6 h | Release at 0.5 h | Release at 6 h | ||||

| F1 | 1 | 45.8 | 100 | F11 | 11 | 29.6 | 80.8 |

| F2 | 2 | 82.2 | 90.1 | F12 | 12 | 35.2 | 85.0 |

| F3 | 3 | 80.1 | 100 | F13 | 13 | 19.2 | 64.5 |

| F4 | 4 | 59.4 | 100 | F14 | 14 | 69.4 | 100 |

| F5 | 5 | 82.0 | 100 | F15* | 15 | 86.9 | 100 |

| F6 | 6 | 83.1 | 100 | F16 | 16 | 82.2 | 90.1 |

| F7 | 7 | 83.1 | 100 | F17 | 17 | 72.9 | 100 |

| F8 | 8 | 59.4 | 100 | F18 | 18 | 80.1 | 100 |

| F9 | 9 | 49.6 | 99.9 | F19# | 19 | 25.8 | 63.0 |

| F10 | 10 | 81.8 | 100 | F20 | 20 | 29.6 | 80.8 |

F15 and F19 are the immediate-release and optimized sustained-release formulations, respectively.

Table 5.

Fit summary for both responses.

| Model | Response | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Release at 0.5 h | Release at 6 h | |||

| Adjusted R2 | Predicted R2 | Adjusted R2 | Predicted R2 | |

| Linear | 0.8080 | 0.7389 | 0.4096 | 0.1613 |

| Quadratic | 0.9889 | 0.8925 | 0.9354 | 0.8017 |

| Special cubic | 0.9713 | 0.9975 | ||

| Cubic | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | ||

An ANOVA test was then applied to study the significance of the various terms in the quadratic model and determine the effect of each factor on each response. The statistically significant p-value (< 0.0001) for both responses signified that the selected model provided a good fit and could predict the data (Table 6). The robustness of the chosen model was demonstrated by the large F values, indicating that the model was significant and presented only a 0.01% chance that a large F-value could occur because of noise. The accuracy of the selected model was further assessed using the normal probability of residuals (studentized). The external results (studentized) were scattered around both sides of the straight line and showed a slight deviation.

Table 6.

ANOVA results for the quadratic model for both responses.

| Response (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Release at 0.5 h | Release at 6 h | |||

| F-value | p-value | F-value | p-value | |

| Model | 188.95 | < 0.0001 | 31.58 | < 0.0001 |

| Linear Mixture | 478.01 | < 0.0001 | 49.32 | < 0.0001 |

| AB | 169.11 | < 0.0001 | 85.94 | < 0.0001 |

| AC | 0.3149 | 0.5871 | 4.89 | 0.0515 |

| AD | 6.69 | 0.0271 | 1.35 | 0.2720 |

| BC | 0.2915 | 0.6011 | 4.73 | 0.0547 |

| BD | 8.35 | 0.0161 | 1.78 | 0.2121 |

| CD | 0.3221 | 0.5829 | 3.76 | 0.0811 |

| Transform | Base 10 Log | None | ||

P-values less than 0.05 indicate that the model term is significant, while values greater than 0.10 indicate that the model term is not significant.

3.3. Model fitting and evaluation of the responses (R1: release at 0.5 h and R2: release at 6 h)

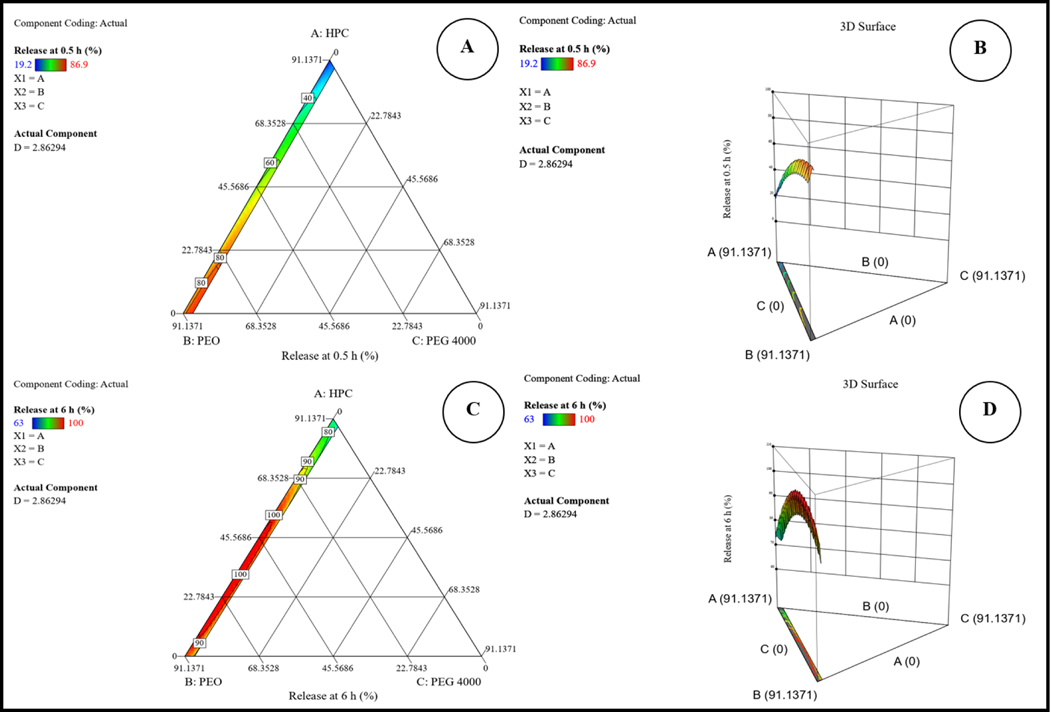

The ANOVA results revealed a significant statistical relationship between the components and responses at the 95% confidence level and demonstrated that the linear mixture components had a significant effect on each response (p < 0.0001). The results also revealed that the release at 0.5 and 6 h was significantly affected by the synergistic effect of a linear mixture (p < 0.0001) for all tested factors (Table 6). The lack of fit was not significant for the two models, with p-values of 0.7521 and 0.3519 for R1 and R2, respectively. The selected quadratic models also showed high a R2 of 0.9942 for R1 and 0.9660 for R2, thus revealing a strong correlation between the independent and dependent variables. The predicted R2 values were in reasonable agreement with the adjusted R2 values (the difference was less than 0.2), indicating the accuracy of the predictive model (Table 5). Moreover, the obtained signal-to-noise ratios (adequate precision > 4), with a value of 41.261 for R1 and 18.958 for R2, indicated that the signal was adequate to navigate the design space. Box-Cox plots were examined for any suggested data transformations. Log transformation was suggested for R1, whereas no transformation was required for R2. Moreover, outliers were not observed for the two models.

The quadratic model equations with coded factors for R1 and R2 as a function of the independent variables are presented in Eqs. 1 and 2, respectively. The magnitudes and signs of the term coefficients in the regression equations were used to infer the effects of their respective terms. A positive coefficient of any equation term demonstrates that an increase in the term leads to a simultaneous increase in the response, whereas the opposite is true for the negative coefficient (Bolton and Bor, 2003). Polynomial equations can be applied to predict the % release for any given concentration of each independent variable.

| (1) |

| (2) |

Both equations demonstrated that factor D (sorbitol) has a predominant potent positive effect on R1 and R2 as a result of the high water solubility of sorbitol, which led to faster disintegration of the ocular inserts and fast exposure of the drug to the release medium; this finding was consistent with earlier investigations (Dukić-Ott et al., 2007). However, factor C (PEG 4000) provided the most potent antagonistic effect on both responses. PEG 4000 is known to improve drug release in any dosage form. However, the decrease in drug release with increasing PEG 4000 concentration could indicate a higher-order relationship between drug release and PEG 4000 concentrations. This observation is consistent with an earlier report that applied lower concentrations of propylene glycol (Thakkar et al., 2021). The three-dimensional response surface and two-dimensional contour plots for both responses are graphically illustrated in Fig. 3. The two-dimensional contour plot in Fig. 4 shows the optimization of the formulation and possible predicted values for both responses from the model.

Figure 3.

Two-dimensional contour (A&C) and three-dimensional response surface plots (B&D) for both responses.

Figure 4.

Two-dimensional contour plots showing the desirability and predicted response for the proposed solution.

3.4. Optimization and validation of the experimental design

Staphylococcus aureus, Coagulase-negative Staphylococci, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa are the leading pathogens that cause ocular infections. The reported MIC90 value of CIP was 64 μg/mL against fluoroquinolone-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and 0.125 μg/mL against Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Kowalski et al., 2003). Therefore, the prepared inserts should release at least 25% of their CIP content starting at the first time point (30 min) to supersede the highest required MIC90 value (64 μg/mL) for better therapeutic outcomes. Moreover, the main objective of this study was to prepare sustained-release ocular inserts of CIP-HCL; therefore, the target drug release at 6 h was set at 60%.

After the analysis of responses and construction of good regression models, an optimization step was performed to select the level of factors. The process was optimized by setting the goals of the independent variables and responses and applying the global desirability function (D), as shown in Table 7. Based on these criteria, a desirability plot was generated, with a D value of 0.631. To achieve the desired responses with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), the Design-Expert software suggested one formulation (F19) that included 91% w/w of HPC, 3.0% w/w of PEG 4000, 0.0% of PEO, and 0.0% of sorbitol to fulfill the optimum formulation requirements. Using these variables and their respective levels resulted in a formulation with a % release of 25.4 and 62.8 at 0.5 (R1) and 6 h (R2), respectively. This solution is graphically represented by cubes in Fig. 4. A validation trial (formulation) was performed in triplicate to compare the actual release (%) values with their respective predicted values. The mean of the observed target release values was found to be within a 95% CI of the software predicted values, as presented in Table 8.

Table 7.

Criteria of variables and responses for the optimization step.

| Variable | Goal | Lower limit | Upper limit |

|---|---|---|---|

| A: HPC | in range | 0 | 94 |

| B: PEO | in range | 0 | 94 |

| C: PEG 4000 | in range | 0 | 3 |

| D: Sorbitol | in range | 0 | 6 |

| R1: Release at 0.5 h | target = 25 | 20 | 30 |

| R2: Release at 6 h | target = 60 | 55 | 65 |

Table 8.

Results of the validation trials of the proposed solution (mean, n = 3).

| Response (%) | Predicted value | Results of validation trials | 95% CI (low) of the mean | 95% CI (high) of the mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Release at 0.5 h | 25.4 | 26.3 | 22.8 | 28.3 |

| Release at 6 h | 62.8 | 58.3 | 56.2 | 69.5 |

3.5. Characterization of the prepared CIP-HCL-HME ocular insert

3.5.1. Physical appearance, weight, thickness, surface pH, and drug content

The HME technique was used to obtain thin uniform films. All the prepared ocular films had a good semitransparent appearance, milky white to yellowish color, and smooth and uniform surfaces (Fig. 5). The inserts had an average weight of approximately 5 mg, with dimensions of 2 mm (width) × 1 mm (length), and an average thickness of approximately 1.0 mm, as shown in Table 9.

Figure 5.

Physical appearance of all 20 prepared films.

Table 9.

Weight, thickness, surface pH, and drug content of hot-melt extruded ciprofloxacin hydrochloride ocular inserts (mean ± SD, n = 3).

| Formulation | Weight (mg) | Thickness (mm) | Surface pH | Drug content (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F1 | 5.1 ± 0.02 | 0.9 ± 0.03 | 7.3 ± 0.00 | 91.2 ± 1.0 |

| F2 | 5.2 ± 0.10 | 0.8 ± 0.03 | 7.4 ± 0.02 | 94.0 ± 1.1 |

| F3 | 5.1 ± 0.05 | 1.0 ± 0.01 | 7.4 ± 0.01 | 100.7 ± 4.9 |

| F4 | 5.1 ± 0.04 | 1.0 ± 0.02 | 7.0 ± 0.04 | 90.8 ± 1.3 |

| F5 | 5.2 ± 0.03 | 0.9 ± 0.02 | 7.4 ± 0.01 | 96.3 ± 2.4 |

| F6 | 5.1 ± 0.02 | 0.9 ± 0.02 | 7.3 ± 0.00 | 90.1 ± 1.4 |

| F7 | 5.1 ± 0.02 | 1.1 ± 0.01 | 7.1 ± 0.01 | 101.4 ± 1.2 |

| F8 | 5.1 ± 0.04 | 0.9 ± 0.02 | 7.3 ± 0.01 | 91.7 ± 0.5 |

| F9 | 5.2 ± 0.10 | 1.0 ± 0.01 | 7.3 ± 0.01 | 90.9 ± 2.1 |

| F10 | 5.1 ± 0.04 | 1.0 ± 0.02 | 7.4 ± 0.01 | 91.3 ± 1.5 |

| F11 | 5.1 ± 0.03 | 1.0 ± 0.01 | 7.4 ± 0.00 | 92.4 ± 1.7 |

| F12 | 5.3 ± 0.06 | 1.1 ± 0.01 | 7.4 ± 0.00 | 92.5 ± 2.3 |

| F13 | 5.3 ± 0.15 | 1.1 ± 0.02 | 7.2 ± 0.00 | 92.1 ± 2.4 |

| F14 | 5.0 ± 0.01 | 0.9 ± 0.03 | 7.4 ± 0.01 | 90.3 ± 1.5 |

| F15 | 5.3 ± 0.09 | 0.9 ± 0.04 | 7.4 ± 0.01 | 93.4 ± 1.4 |

| F16 | 5.2 ± 0.10 | 1.0 ± 0.02 | 7.4 ± 0.00 | 91.0 ± 1.8 |

| F17 | 5.2 ± 0.04 | 1.0 ± 0.01 | 7.2 ± 0.06 | 96.4 ± 2.0 |

| F18 | 5.1 ± 0.11 | 1.1 ± 0.02 | 7.4 ± 0.00 | 91.9 ± 1.9 |

| F19 | 5.2 ± 0.14 | 1.0 ± 0.01 | 7.3 ± 0.01 | 98.6 ± 3.3 |

| F20 | 5.1 ± 0.06 | 1.0 ± 0.02 | 7.4 ± 0.01 | 96.8 ± 1.3 |

The normal human tear pH ranges from 6.5 to 7.6, with a mean value of 7.0 (Abelson et al., 1981). The eye globe can tolerate topically instilled dosage forms over a pH range of 3.0 to 8.6 depending on the buffering capacity of the formulation (USP). The surface pH was in the range of 7.0–7.4, which is favorable for ocular applications. The CIP content of each prepared insert was within the acceptance limits of the label’s content (± 10%), and the drug content in all inserts varied from 90.1 ± 1.4 to 101.4 ± 1.2% (Table 9).

3.5.2. Swelling index

Determining the swelling index of the insert is important because this information could provide an indication of the adhesive characteristics of the ocular inserts. Polymer swelling is required to initiate bioadhesion of the inserts to the ocular surface (Shadambikar et al., 2021b). The swelling index corresponds to the water-retaining capacity of the polymers (Shadambikar et al., 2021b). Water absorption increased with time because of the hydrophilic nature of the polymer. Both inserts were hydrated quickly, and the CIP-HCL-IR (F15) insert reached a hydration level of approximately 29% within 30 min (Fig. 6). However, the optimized CIP-HCL-HME formulation (F19) only reached a level of 12% within 30 min. The high swelling index for the IR ocular inserts containing PEO N10 compared with the optimized insert could be due to the fact that PEO N10 is a hydrophilic swellable polymer that forms a gel layer upon hydration (Li et al., 2008).

Figure 6.

Swelling index (%) of the immediate- and sustained-release ciprofloxacin hydrochloride ocular inserts in isotonic phosphate buffer saline (mean ± SD, n = 3)

3.5.3. Moisture absorption and loss

The observed % moisture absorption and loss values for the F19 insert were 15.3 ± 0.4 and 4.6 ± 0.7%, respectively. Although the % moisture absorption and loss were high, no change was observed in the insert integrity under high humidity and dry test conditions, which was evaluated based on physical appearance.

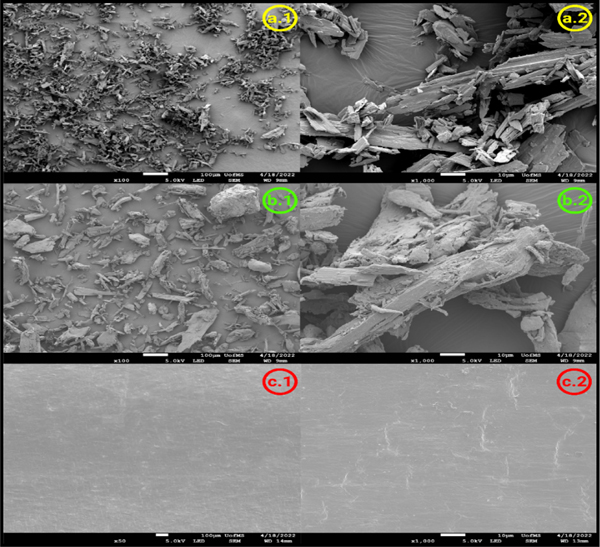

3.5.4. DSC

The thermal characteristics and compatibility of the CIP-HCL-HME insert ingredients were evaluated using DSC as shown in Fig. 7. The DSC thermogram of pure CIP-HCL showed a sharp endothermic peak with an onset at 161 °C because of the crystalline nature of the drug. PEO and HPC polymers showed an endothermic melting peak (broad peak for HPC) at 69 and 90 °C, respectively, indicating their melting transitions. PEG 4000 and sorbitol showed endothermic peaks at 60 °C and 100 °C, respectively. The absence of an endothermic drug peak in the PMs of the immediate- and sustained-release formulations (F15 and F19) prior to HME indicated that the drug was soluble in the PEO–HPC polymer matrix. Moreover, the absence of the same endothermic drug peak in the CIP-HCL-HME and CIP-HCL-HME-IR DSC curves indicates that the drug was converted into its amorphous form within the polymer matrix.

Figure 7.

DSC thermograms of pure active and inactive ingredients, physical mixtures, and ciprofloxacin hydrochloride hot-melt-extruded ocular inserts.

The amorphous form of certain drugs is unstable and tends to revert to its stable crystalline form over time, which could change the formulation properties, such as the release rate and, thus could ultimately affect ocular bioavailability (Thakkar et al., 2021). Hence, the CIP-HCL-HME inserts were stored at 25 ± 2 °C for 3 months (last time point examined) to observe any change in crystallinity, as shown in Fig. 7. The endothermic CIP peak was not observed in the DSC thermogram of the optimized inserts at day 90, which indicated the absence of any crystal form transformation and the stability of the HME-fabricated inserts at room temperature upon storage.

3.5.5. FTIR

The FTIR spectra of pure CIP-HCL, HPC, PEG, the PM, and the optimized CIP-HCL-HME inserts were investigated for incompatibility between the active and inactive ingredients within the inserts, as shown in Fig. 8. The FTIR spectrum of pure CIP-HCL showed a carbonyl group stretching band at 1722 cm−1, a stretching vibration of the C–F bond at 1290 cm−1, and a C–H stretching vibration band of the phenyl ring at 3043 and 2918 cm−1 (Youssef et al., 2021b). The PM and optimized inserts showed a similar spectrum to that of the pure HPC polymer because both formulations contained a high % of this polymer (91%). Moreover, the absence of characteristic CIP-HCL peaks in the FTIR spectra of PM and the optimized inserts could be due to the high solubility of CIP in the polymeric matrix.

Figure 8.

FTIR spectra for pure CIP-HCL, pure HPC JXF, pure PEG 4000, physical mixture of the optimized formulation, and optimized CIP-HCL-HME ocular inserts.

3.5.6. SEM

The SEM micrographs of pure CIP-HCL, PM, and the optimized CIP-HCL-HME insert are shown in Fig. 9. Pure CIP-HCL exhibited a crystalline structure (Fig. 9 a.1&2). The crystalline nature of the drug was still preserved in the PM (Fig. 9 b.1&2), whereas the optimized CIP-HCL-HME insert showed a smooth surface and no CIP-HCL crystals on the surface, suggesting that the drug was well dispersed throughout the polymeric matrix at the molecular level due to the HME process (Fig. 9 c.1&2). Thus, the SEM micrographs complemented the findings of the DSC analysis with the amorphous form within the fabricated insert.

Figure 9.

SEM micrographs of pure ciprofloxacin hydrochloride (100X (a.1) and 1000X (a.2)), physical mixture of the optimized formulation (100X (b.1) and 1000X (b.2)), and optimized CIP-HCL-HME insert (100X (c.1) and 1000X (c.2)).

3.5.7. Ex vivo bioadhesive strength

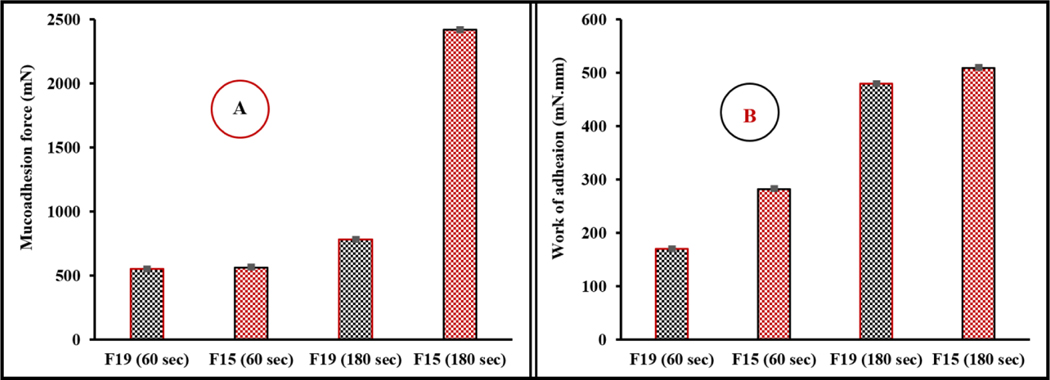

Mucoadhesion is defined as adhesion between two materials, one of which is the mucosal surface. Mucoadhesive drug delivery systems enable prolonged retention at the ocular surface and improve ocular bioavailability to achieve better therapeutic outcomes (Shaikh et al., 2011). Therefore, the mucoadhesive characteristics of the CIP-HCL-HME and CIP-HCL-HME-IR inserts were tested on freshly excised rabbit corneas, as shown in Fig. 2. The force and work of adhesion (WOA) exhibited a simultaneous increase with increases in the testing period for both formulations, with the highest values observed for the CIP-HCL-HME-IR inserts (Fig. 10). The two recorded mucoadhesive parameters were directly correlated, with a higher mucoadhesive force corresponding to a higher WOA recorded for the ocular inserts.

Figure 10.

Mucoadhesion forces (A) and work of adhesion (B) of the immediate- and optimized sustained-release hot-melt-extruded ocular inserts of ciprofloxacin hydrochloride (means ± SD, n = 3)

Various theories (electronic, diffusion, adsorption, wetting, and interpenetration) have been proposed to explain bioadhesion and mucoadhesion (Ludwig, 2005). To be an excellent mucoadhesive agent, the polymer within the drug delivery system should be in close contact with the mucin layer covering the corneal surface (Ludwig, 2005). The polymer chains should be mobile and flexible to diffuse into the mucus and penetrate to a sufficient depth to entangle mucin in a strong network. Moreover, polymers form hydrogen bonds as well as electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions with mucins. However, the interpenetration and molecular entanglement between the polymer and mucus layer require a critical chain length. The threshold molecular weight required for successful mucoadhesion is 100 KDa (Ludwig, 2005). Polymers with higher molecular weights could exhibit excessive cross-linking between polymer chains, thus decreasing the chain length accessible for interfacial penetration and entanglement with the mucus layer (Madsen et al., 1998). The stronger adhesive forces for PEO N10 compared with HPC could be due to the lower molecular weight (10 KDa) of the PEO polymer compared to HPC JXF (140 KDa).

3.5.8. In vitro release studies

Based on visual observations, the inserts started to swell slightly when the release medium (PBS, pH 7.4, 2.5% RMβCD) was placed inside the glass vials above them. Additionally, all inserts started to dissolve and diminish in size, and they were completely dissolved in the release medium by the end of the study (24 h). The in vitro drug release profiles as a function of time are graphically illustrated in Fig. 11A-B. The CIP-HCL-HME-IR insert did not contain high amounts of HPC JXF (22.4%) and PEG 4000 (0.75%), was primarily composed of PEO N100 (69.4%), and had the same drug load (6.0%) as the optimized insert. Based on Fig. 11B, 86.9% drug release was achieved from the CIP-HCL-HME-IR (F15) within 30 min; thus, it served as an immediate-release platform. However, the optimized CIP-HCL-HME insert released only 25.8 ± 2.0% of its drug content during the first 30 min and achieved a sustained CIP-HCL release profile with 75.0 ± 1.8% drug release at the end of 24 h.

Figure 11.

A) In vitro release profiles of all 20-ciprofloxacin hydrochloride hot-melt-extruded ocular inserts in release inserts (mean ± SD, n = 3) in the design space. B) In vitro release profile of ciprofloxacin hydrochloride from the immediate- and optimized sustained-release inserts.

To understand the mechanism of drug release from the optimized inserts, five conventional release models, including Zero-order (R2 = 0.4457), First-order (R2 = 0.6086), Higuchi (R2 = 0.8879), Hixson-Crowell (R2 = 0.5532), and Korsmeyer-Peppas (R2 = 0.9945), were fitted to the release data, and a regression analysis was performed. Mathematical model fitting revealed that the release profile of the optimized insert followed the Korsmeyer-Peppas model. The calculated slope value (n = 0.52) of the Korsmeyer-Peppas model (0.5<n<1.0) indicated non-Fickian drug release profiles controlled by both erosion and diffusion mechanisms. These results are in accordance with earlier reports (Thakkar et al., 2021).

3.5.9. Antibacterial activity

The correlation between the release profile and the antibacterial activity is shown in Fig. 12. No bacterial growth was detected in any of the released samples during the time course of the study (0.5 to 24 h), indicating that an experimental MIC of 50 (1.25 μg/mL) against Pseudomonas aeruginosa was achieved across all release timepoints. It is worth mentioning that the release study samples were diluted (10-fold) before antibacterial testing. Consequently, the MIC levels could be achieved at any time before the start of the release time point (30 min). Based on the strong correlation revealed in this study, the release data can be used to predict antibacterial therapeutic efficacy.

Figure 12.

Relationship between the ciprofloxacin hydrochloride release profile from the optimized hot-melt-extruded insert with antibacterial activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa (% growth and release profile against time).

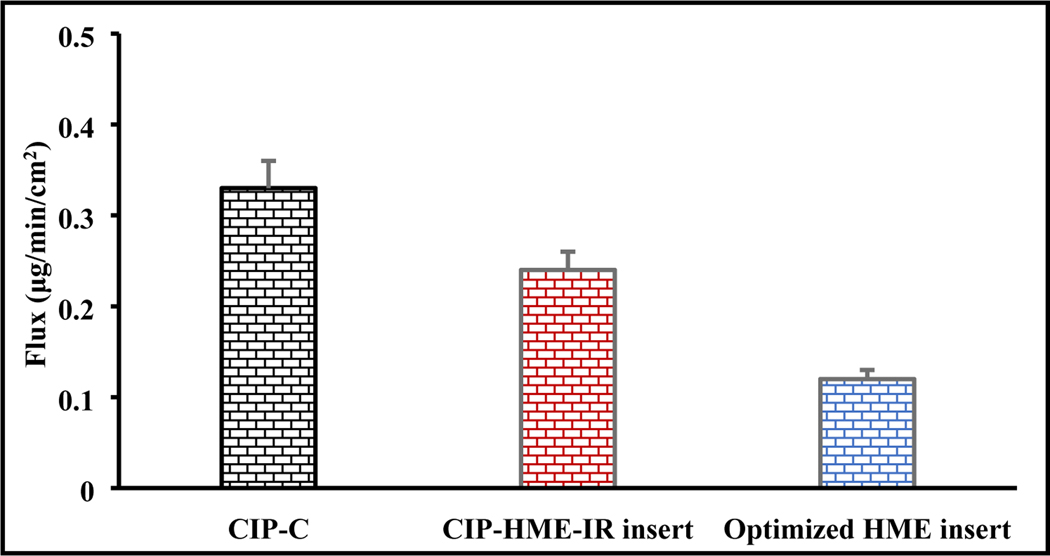

3.5.10. Ex vivo transcorneal permeation

The flux of CIP-HCl from the commercial solution eye drops (CIP-C), CIP-HCL-HME-IR, and optimized CIP-HCL-HME insert was studied across excised rabbit corneas, and the data are shown in Fig. 13. The CIP-HCL flux was in the following order: control (0.33 ± 0.03 μg/min/cm2) > CIP-HCL-HME-IR (0.24 ± 0.02 μg/min/cm2) insert > optimized CIP-HCL-HME (0.12 ± 0.01 μg/min/cm2) insert. Similar observations were reported in earlier investigations (Thakkar et al., 2021), wherein commercial eye drops showed higher flux compared to the corresponding HME ocular inserts. These observations can be explained by the fact that CIP is in a solution form in commercial eye drops while the inserts containing the drug are in a solid state, resulting in low drug flux (Thakkar et al., 2021). Therefore, the CIP-HCL-HME-IR insert was used as another control formulation for proper comparison with the optimized CIP-HCL-HME inserts. The CIP-HCL-HME-IR insert exhibited a 2-fold higher CIP-HCL flux than the optimized CIP-HCL-HME insert. This observation could be due to the fact that the CIP-HCL-HME-IR insert contains a high concentration (69.4% w/w) of PEO as an immediate-release polymer, and lacks the sustained release behavior of the HPC JXF polymer. Therefore, CIP-HCL is able to diffuse out of the polymeric matrix at a faster rate compared to the CIP-HCL-HME insert.

Figure 13.

Transcorneal ciprofloxacin hydrochloride flux (μg/min/cm2) from commercial eyedrops, CIP-HCL-HME-IR insert and the optimized CIP-HCL-HME insert (mean ± SD, n = 143).

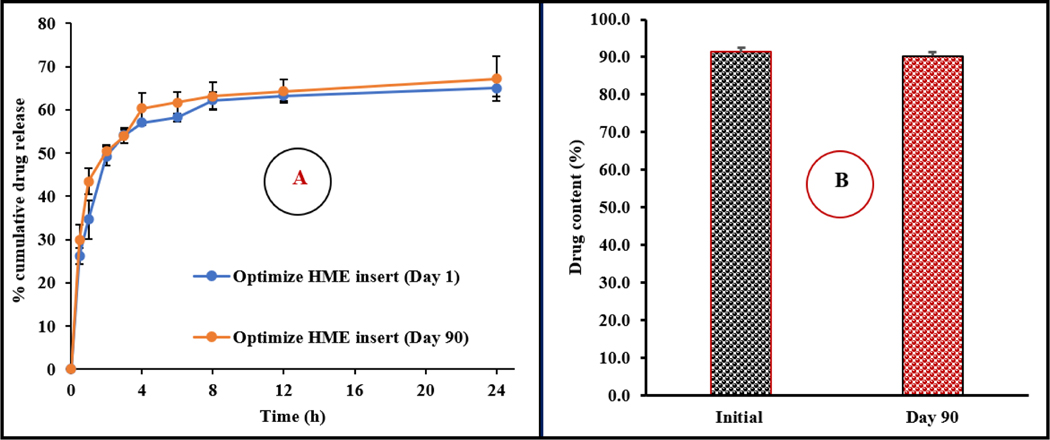

3.5.11. Stability studies

The physicochemical stability of the CIP-HCL-HME inserts was evaluated under room temperature storage conditions for over 90 days (last time point tested). No physical changes, such as swelling or discoloration, were observed during the testing period. The effect of storage conditions on the drug content and release profile is shown in Fig. 14 and the effect on thermal behavior is shown in Fig. 7. The HME inserts did not show any significant (p > 0.05) changes in CIP-HCL content and drug release rate over the storage period. Moreover, the day-90 DSC thermogram of the optimized HME inserts did not show any CIP-HCL crystal-form transformation upon storage.

Figure 14.

A) In vitro release profiles and B) drug content of the optimized CIP-HCL-HME inserts over three-month storage at 25 °C (mean ± SD, n = 3).

4. Conclusions

HME CIP-HCL ocular inserts were successfully prepared using a solvent-free, easily scalable, continuous process with relatively high throughput rates and economical technology. An optimal mixture design was applied to optimize the fabricated inserts for ocular delivery, and it presented a sustained release profile over 24 h. The biodegradable polymeric matrix dissolved completely within 24 h, eliminating the need for removal after application. The optimized formulation was stable at room temperature for 3 months, with no significant changes observed in the drug content, release profile, and solid-state characteristics. Moreover, ex vivo transcorneal permeation studies revealed that the optimized inserts prolonged the transcorneal flux of the drug compared to commercial solution eye drops. Furthermore, bacterial growth was not observed during the in vitro release experiment (24 h), indicating that an MIC of 90 against Pseudomonas aeruginosa was achieved across all release time points. In vivo ocular biodistribution, efficacy, and irritation in a rabbit model are additional future studies required for the formulation to be developed into an ocular dosage form for the treatment of different ocular bacterial infections. In conclusion, the optimized HME inserts could decrease the need for frequent dosing, improve therapeutic outcomes, and increase patient compliance compared with conventional commercial eye drops.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) for providing Parteck® SI 150. The authors are grateful to Ashland Inc. for donating the gift sample of KlucelT JXF PHARM. Also, the authors acknowledge Colorcon, Inc. (Irvine, CA, USA) for providing a sample of POLYOX WSR N10. The authors also acknowledge the Pii Center for Pharmaceutical Technology. Furthermore, the authors acknowledge that the SEM images presented in this work were generated using the instruments and services at the Microscopy and Imaging Center, The University of Mississippi. This facility is supported in part by grant 1726880 from the National Science Foundation.

Funding:

This project was also partially supported by Grant Number P30GM122733 funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) as one of its Centers of Biomedical Research Excellence (COBRE).

Abbreviations:

- ATCC

American Type Culture Collection

- BB

Bacterial blepharitis

- BE

Bacterial endophthalmitis

- BK

Bacterial keratitis

- CLS

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute

- DoE

Design of experiment

- HBSS

Hanks’ balanced salt solution

- HME

Hot-melt extrusion

- IPBS

Isotonic phosphate-buffer saline

- MIC

Minimum inhibitory concentration

- PM

Physical mixture

- PRESS

Predicted residual sum of squares

- STF

Simulated tear fluid

- WOA

Work of adhesion

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or conflicts of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abelson MB, Udell IJ, Weston JH, 1981. Normal human tear pH by direct measurement. Arch. Ophthalmol 99, 301. 10.1001/archopht.1981.03930010303017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad M, Uzir Wahit M, Abdul Kadir MR, Mohd Dahlan KZ, 2012. Mechanical, rheological, and bioactivity properties of ultra high-molecular-weight polyethylene bioactive composites containing polyethylene glycol and hydroxyapatite. Sci. World J 2012, 474851. 10.1100/2012/474851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balguri SP, Adelli GR, Janga KY, Bhagav P, Majumdar S, 2017a. Ocular disposition of ciprofloxacin from topical, pegylated nanostructured lipid carriers: Effect of molecular weight and density of poly (ethylene) glycol. Int. J. Pharm 529, 32–43. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2017.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balguri SP, Adelli GR, Tatke A, Janga KY, Bhagav P, Majumdar S, 2017b. Melt-cast noninvasive ocular inserts for posterior segment drug delivery. J. Pharm. Sci 106, 3515–3523. 10.1016/j.xphs.2017.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertino JS, 2009. Impact of antibiotic resistance in the management of ocular infections: The role of current and future antibiotics. Clin. Ophthalmol 3, 507–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhagurkar AM, Darji M, Lakhani P, Thipsay P, Bandari S, Repka MA, 2019. Effects of formulation composition on the characteristics of mucoadhesive films prepared by hot-melt extrusion technology. J. Pharm. Pharmacol 71, 293–305. 10.1111/jphp.13046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton S, Bor S, 2003. Pharmaceutical Statistics: Practical and Clinical Applications, Revised and Expanded, fourth ed. CRC Press, Boca Raton. 10.1201/9780203912799. [DOI]

- Dukić-Ott A, Remon JP, Foreman P, Vervaet C, 2007. Immediate release of poorly soluble drugs from starch-based pellets prepared via extrusion/spheronisation. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm 67, 715–724. 10.1016/j.ejpb.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedlaender MH, 1995. A review of the causes and treatment of bacterial and allergic conjunctivitis. Clin. Ther 17, 800–810. 10.1016/0149-2918(95)80058-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta B, Mishra V, Gharat S, Momin M, Omri A, 2021. Cellulosic polymers for enhancing drug bioavailability in ocular drug delivery systems. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 14, 1201. 10.3390/ph14111201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyndiuk RA, Eiferman RA, Caldwell DR, Rosenwasser GO, Santos CI, Katz HR, Badrinath SS, Reddy MK, Adenis JP, Klauss V, Adenis JP, 1996. Comparison of Ciprofloxacin Ophthalmic solution 0.3% to fortified tobramycin-cefazolin in treating bacterial corneal ulcers. Ophthalmology. 103, 1854–1863. 10.1016/S0161-6420(96)30416-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khurana G, Arora S, Pawar PK, 2012. Ocular insert for sustained delivery of gatifloxacin sesquihydrate: Preparation and evaluations. Int. J. Pharm. Investig 2, 70–77. 10.4103/2230-973X.100040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski RP, Dhaliwal DK, 2005. Ocular bacterial infections: Current and future treatment options. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther 3, 131–139. 10.1586/14787210.3.1.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski RP, Dhaliwal DK, Karenchak LM, Romanowski EG, Mah FS, Ritterband DC, Gordon YJ, 2003. Gatifloxacin and moxifloxacin: An in vitro susceptibility comparison to levofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, and ofloxacin using bacterial keratitis isolates. Am. J. Ophthalmol 136, 500–505. 10.1016/S0002-9394(03)00294-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBel M, 1988. Ciprofloxacin: Chemistry, mechanism of action, resistance, antimicrobial spectrum, pharmacokinetics, clinical trials, and adverse reactions. Pharmacotherapy. 8, 3–33. 10.1002/j.1875-9114.1988.tb04058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Hardy RJ, Gu X, 2008. Effect of drug solubility on polymer hydration and drug dissolution from polyethylene oxide (PEO) matrix tablets. AAPS PharmSciTech. 9, 437–443. 10.1208/s12249-008-9060-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, AbuBaker O, Shao ZJ, 2006. Characterization of poly(ethylene oxide) as a drug carrier in hot-melt extrusion. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm 32, 991–1002. 10.1080/03639040600559057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Ji J, Li S, Wang Z, Tang L, Cao W, Sun X, 2017. Microbiological isolates and antibiotic susceptibilities: A 10-year review of culture-proven endophthalmitis cases. Curr. Eye Res 42, 443–447. 10.1080/02713683.2016.1188118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig A, 2005. The use of mucoadhesive polymers in ocular drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 57, 1595–1639. 10.1016/j.addr.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen F, Eberth K, Smart JD, 1998. A rheological assessment of the nature of interactions between mucoadhesive polymers and a homogenised mucus gel. Biomaterials. 19, 1083–1092. 10.1016/S0142-9612(98)00037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumdar S, Hingorani T, Srirangam R, 2010. Evaluation of active and passive transport processes in corneas extracted from preserved rabbit eyes. J. Pharm. Sci 99, 1921–1930. 10.1002/jps.21979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narala S, Nyavanandi D, Alzahrani A, Bandari S, Zhang F, Repka MA, 2022. Creation of hydrochlorothiazide pharmaceutical cocrystals via hot-melt extrusion for enhanced solubility and permeability. AAPS PharmSciTech. 23, 56. 10.1208/s12249-021-02202-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachigolla G, Blomquist P, Cavanagh HD, 2007. Microbial keratitis pathogens and antibiotic susceptibilities: A 5-year review of cases at an urban County Hospital in North Texas. Eye Contact Lens. 33, 45–49. 10.1097/01.icl.0000234002.88643.d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira GG, Figueiredo S, Fernandes AI, Pinto JF, 2020a. Polymer selection for hot-melt extrusion coupled to fused deposition modelling in pharmaceutics. Pharmaceutics. 12, 795. 10.3390/pharmaceutics12090795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picker-Freyer KM, Dürig T, 2007. Physical mechanical and tablet formation properties of hydroxypropylcellulose: In pure form and in mixtures. AAPS PharmSciTech. 8, 82–90. 10.1208/pt0804092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polat HK, Bozdağ Pehlivan SB, Özkul C, Çalamak S, Öztürk N, Aytekin E, Fırat A, Ulubayram K, Kocabeyoğlu S, İrkeç M, Çalış S, 2020. Development of besifloxacin HCl loaded nanofibrous ocular inserts for the treatment of bacterial keratitis: In vitro, ex vivo and in vivo evaluation. Int. J. Pharm 585, 119552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repka MA, Majumdar S, Kumar Battu S, Srirangam R, Upadhye SB, 2008. Applications of hot-melt extrusion for drug delivery. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv 5, 1357–1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repka MA, McGinity JW, 2000. Influence of vitamin E TPGS on the properties of hydrophilic films produced by hot-melt extrusion. Int. J. Pharm 202, 63–70. 10.1016/S0378-5173(00)00418-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Righter J, 1987. Ciprofloxacin treatment of Staphylococcus aureus infections. J. Antimicrob. Chemother 20, 595–597. 10.1093/jac/20.4.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadambikar G, Marathe S, Patil A, Joshi R, Bandari S, Majumdar S, Repka M, 2021a. Novel application of hot melt extrusion technology for preparation and evaluation of valacyclovir hydrochloride ocular inserts. AAPS PharmSciTech. 22, 48. 10.1208/s12249-020-01916-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh R, Raj Singh TR, Garland MJ, Woolfson AD, Donnelly RF, 2011. Mucoadhesive drug delivery systems. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci 3, 89–100. 10.4103/0975-7406.76478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shettar A, Shankar VK, Ajjarapu S, Kulkarni VI, Repka MA, Murthy SN, 2021. Development and characterization of Novel topical oil/PEG creams of voriconazole for the treatment of fungal infections. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol 66, 102928. 10.1016/j.jddst.2021.102928. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Teweldemedhin M, Gebreyesus H, Atsbaha AH, Asgedom SW, Saravanan M, 2017. Bacterial profile of ocular infections: A systematic review. BMC Ophthalmol. 17, 212. 10.1186/s12886-017-0612-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakkar R, Komanduri N, Dudhipala N, Tripathi S, Repka MA, Majumdar S, 2021. Development and optimization of hot-melt extruded moxifloxacin hydrochloride inserts, for ocular applications, using the design of experiments. Int. J. Pharm 603, 120676. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2021.120676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thakkar R, Thakkar R, Pillai A, Ashour EA, Repka MA, 2020. Systematic screening of pharmaceutical polymers for hot melt extrusion processing: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Pharm 576, 118989. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2019.118989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youssef A, Dudhipala N, Majumdar S, 2020. Ciprofloxacin loaded nanostructured lipid carriers incorporated into in-situ gels to improve management of bacterial endophthalmitis. Pharmaceutics. 12, 572. 10.3390/pharmaceutics12060572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youssef AAA, Cai C, Dudhipala N, Majumdar S, 2021a. Design of topical ocular ciprofloxacin nanoemulsion for the management of bacterial keratitis. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 14, 210. 10.3390/ph14030210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youssef AAA, Dudhipala N, Majumdar S, 2022a. Dual drug loaded lipid nanocarrier formulations for topical ocular applications. Int. J. Nanomedicine 17, 2283–2299. 10.2147/IJN.S360740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]