Abstract

Uterine carcinosarcoma, which is categorized as high-grade endometrial cancer, is an uncommon kind of malignant gynecological neoplasms. Clinically, this tumor frequently affects menopausal women and the main symptom is abnormally postmenopausal vaginal bleeding. Surgery continues to be the main treatment for carcinosarcoma. In this study, we wanted to discuss 2 cases of uterine carcinosarcoma in 2 women who were in menopause and who had been evaluated by ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging.

Keywords: Carcinosarcoma, Uterus, Ultrasound, Magnetic resonance imaging

Introduction

Less than 5% of uterine malignancies are uterine carcinosarcomas (UCS), which are rare tumors defined by a mix of malignant stromal and epithelial tissue [1,2]. The incidence rate of UCS was growing substantially, and the survival outcomes for women were worse than those for endometrial cancer or even uterine sarcoma. UCS will have better prognosis when diagnosed and treated properly and early. Ultrasound is the first-line diagnostic modality for the assessment of UCS and preoperatively, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) plays an essential role as main imaging and staging methods [3], [4], [5]. In this paper, we wanted to present 2 uterine carcinosarcoma instances that were examined using ultrasound and MRI.

Cases description

Case 1

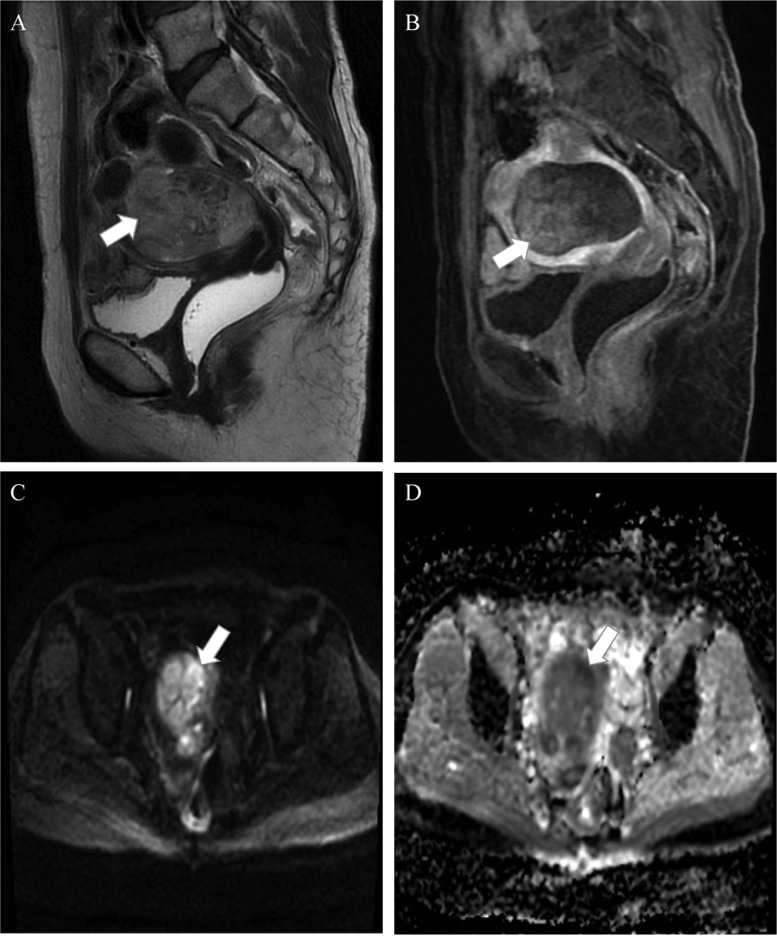

A 56-year-old G1P1 female who had experienced excessive, irregular vaginal bleeding for 2 months admitted to the hospital. The patient acknowledged losing weight during the previous 2 months but denied experiencing palpitations and urinary problems. A space-occupying mass in the uterine cavity was seen on preoperative MRI (Fig. 1). The 67 × 60 × 44 mm lesion had an amorphous form. T2-weighted imaging (T2WI) of the lesion showed mix signal with flow voids. The mass enhanced very weakly on the T1-weighted image (T1WI) with contrast agent. The apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) value of the lesion was 0.9 × 10−3 mm2/s.

Fig. 1.

A heterogeneous mass (arrows) can be seen inside the uterus on the sagittal T2W (A). On T1W with contrast agent, the lesion showed weak enhancement (B). Within the mass, there are several regions with limited diffusion (arrow) on DWI (C) and matching low signal on the ADC map (D).

The mass appears to have invaded the myometrium beyond the serosal and by more than 50%. The initial diagnosis was endometrial cancer. The patient experiences surgery including hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and pelvic lymph node dissection. Based on histopathological findings, the mass was a carcinosarcoma along with metastatic left pelvic lymph nodes. According to FIGO 2018, the condition was staged as IIIC1. Following surgery, she kept getting the 6 cycles of carboplatin/paclitaxel every 3 weeks.

Case 2

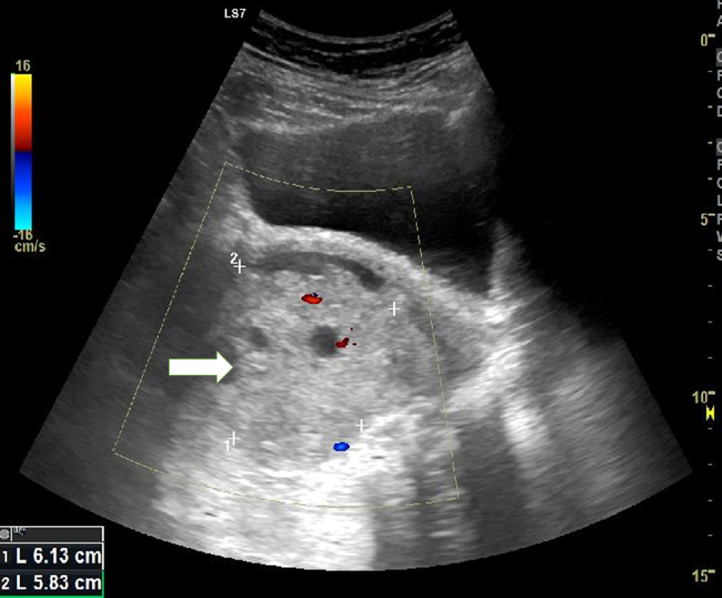

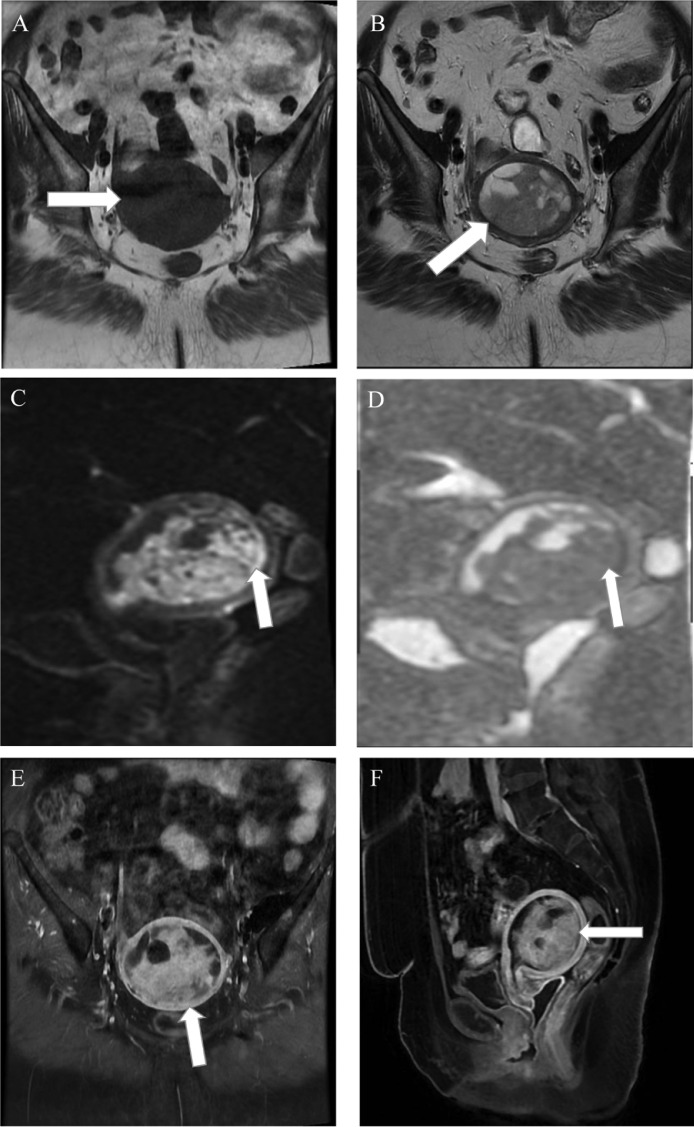

A 60-year-old postmenopausal woman reported having vaginal bleeding and pelvic distension for a week. A heterogeneous echotexture and ill-defined mass within the uterus were visible on abdominal ultrasonography (Fig. 2). On MRI examination, the mass was low signal intensity on T1WI and heterogeneous high signal intensity on T2WI. The mass also had central necrosis (Fig. 3). The solid component had high signal intensity on diffusion-weighted imaging and low signal intensity on ADC map that were consistent with limited diffusion. ADC value of the lesion was 0.8 × 10−3 mm2/s. Less than half of the myometrium's thickness appears to be invaded by mass. The preliminary diagnosis was endometrial cancer. Bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection, radical hysterectomy, and salpingo-oophorectomy were all performed. A uterine carcinosarcoma with no evidence of metastases in the pelvic lymph nodes was identified by the pathological analysis. As to FIGO 2018, the pathological stage was IA.

Fig. 2.

Pelvic ultrasonography shows ill-defined border tumor inside the uterus with a heterogeneous echotexture (arrow).

Fig. 3.

The axial precontrast T1-weighted (A) and T2-weighted (B) MRI images demonstrate a heterogeneous mass (arrows) centered within the uterus. Within the mass, there are several regions with limited diffusion (arrows, (C, D) showing strong signal on DWI (C) and matching low signal on the ADC map (D). On postcontrast axial (E) and sagittal (F) T1-weighted fat-saturated images, the lesion shows heterogeneously enhanced (arrow).

Discussion

Carcinosarcoma of uterus, a rare form of the cancer, is classified as high-grade endometrial cancer [2]. Age of onset is usually in about 70-year-old and risk factors include black race, history of pelvic radiation therapy, or tamoxifen therapy [6], [7], [8].

The aggressive cancer UCS often spreads to the lung and lymph nodes [9].

Based mostly on the histopathology of the disease, 4 fundamental hypotheses have been put out regarding the cellular origins of carcinosarcoma [10,11]. The first is the collision tumor hypothesis, which presumes that 2 distinct tumors merge to form a single neoplasm, based on the finding that patients with sun-damaged skin frequently develop skin cancers and superficial malignant fibrous histiocytomas; the second is the composition hypothesis, which argues that the mesenchymal component is a pseudosarcomatous response to the epithelial malignancy. The third is the combination hypothesis, which contends that both the epithelial and mesenchymal components of the tumor originate from a common pluripotential stem cell that undergoes divergent differentiation. The fourth is the conversion/divergence hypothesis, which contends that the sarcomatous component of the tumor is a metaplastic sarcomatous transformation of the epithelial component [11], [12], [13].

Dramatically, with the advancement of sophisticated methods for DNA analysis and immunohistochemistry, it is more likely to believe that carcinosarcoma is a metaplastic cancer in which mutant epithelial cells divide to become mesenchymal cells. According to Gorai et al. [14], the tumor's mesenchymal and epithelial cells both have similar genetic flaws.

Radiologically, particularly MRI had a superior role in the staging of uterine carcinosarcoma. The staging method of the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics or the Tumor, Node, Metastasis classification system should be used to interpret this malignancy because it is categorized as endometrial carcinoma. MRI has a 70% staging accuracy rate [15].

The most typical presenting characteristics of UCS lesions are large masses filling the cavity, low or equal signal intensity on T1WI, high or mixed signal intensity on T2WI. Lesion has high signal patches on T1WI, which may suggest bleeding and is a highly distinct hallmark of carcinosarcoma. Mild to moderate enhancement is a key characteristic that distinguishes carcinosarcoma from other malignant tumors. The carcinosarcoma typically shows progressive or permanent mild or moderate enhancement, whereas the carcinoma frequently shows modest enhancement in the early stage and reduction in the late stage [16,17].

Surgical excision is the primary method of therapy for UCS, which may involve hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and dissection of the pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes. Additionally, it is thought that patients' chances of survival are improved by adjuvant therapy following surgery, such as radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or combination therapy [18], [19], [20].

Conclusions

A mix of carcinomatous and sarcomatous tumors characterizes the uncommon gynecological cancer known as UCS. Among the explanations put out, UCS is seen as a metaphasic carcinoma with epithelial cells turning into mesenchymal cells. It is challenging to distinguish between endometrial uterine cancer and carcinosarcoma. MRI is the best imaging modality for staging because to its superior soft tissue resolution and capacity to assess myometrial invasion.

Authors’ contribution

Ho Xuan Tuan and Nguyen Minh Duc contributed to write original draft. Cao Minh Tri and Nguyen Minh Duc contributed to undergo diagnostic procedure, collect, and interpret the imaging. Huynh-Thi Do Quyen, Cao Minh Tri, and Nguyen Minh Duc made substantial contributions to collect patient data and clinical data analysis. All authors have read, revised, and approved the final published version of the manuscript. All authors were responsible for submission of our study for publication.

Statement of ethics

Ethical approval was not necessary for the preparation of this article.

Data availability statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and/or its online supplementary material files. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Patient consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Kurnit KC, Previs RA, Soliman PT, Westin SN, Klopp AH, Fellman BM, et al. Prognostic factors impacting survival in early stage uterine carcinosarcoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2019;152(1):31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.10.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cantrell LA, Blank SV, Duska LR. Uterine carcinosarcoma: a review of the literature. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137(3):581–588. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsuo K, Ross MS, Machida H, Blake EA, Roman LD. Trends of uterine carcinosarcoma in the United States. J Gynecol Oncol. 2018;29(2):e22. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2018.29.e22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fader AN, Java J, Tenney M, Ricci S, Gunderson CC, Temkin SM, et al. Impact of histology and surgical approach on survival among women with early-stage, high-grade uterine cancer: an NRG Oncology/Gynecologic Oncology Group ancillary analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;143(3):460–465. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Desai NB, Kollmeier MA, Makker V, Levine DA, Abu-Rustum NR, Alektiar KM. Comparison of outcomes in early stage uterine carcinosarcoma and uterine serous carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;135(1):49–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.07.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sutton G. Uterine sarcomas 2013. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;130(1):3–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brooks SE, Zhan M, Cote T, Baquet CR. Surveillance, epidemiology, and end results analysis of 2677 cases of uterine sarcoma 1989-1999. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;93(1):204–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsuo K, Ross MS, Bush SH, Yunokawa M, Blake EA, Takano T, et al. Tumor characteristics and survival outcomes of women with tamoxifen-related uterine carcinosarcoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;144(2):329–335. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.11.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schiavone MB, Zivanovic O, Zhou Q, Leitao MM, Jr., Levine DA, Soslow RA, et al. Survival of patients with uterine carcinosarcoma undergoing sentinel lymph node mapping. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(1):196–202. doi: 10.1245/s10434-015-4612-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zidar N, Gale N. Carcinosarcoma and spindle cell carcinoma–monoclonal neoplasms undergoing epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Virchows Arch. 2015;466(3):357–358. doi: 10.1007/s00428-014-1686-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loh TL, Tomlinson J, Chin R, Eslick GD. Cutaneous carcinosarcoma with metastasis to the parotid gland. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/173235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bansal N, Herzog TJ, Seshan VE, Schiff PB, Burke WM, Cohen CJ, et al. Uterine carcinosarcomas and grade 3 endometrioid cancers: evidence for distinct tumor behavior. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(1):64–70. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318176157c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nama N, Cason FD, Misra S, Hai S, Tucci V, Haq F, et al. Carcinosarcoma of the uterus: a study from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Result (SEER) database. Cureus. 2020;12(9):e10283. doi: 10.7759/cureus.10283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gorai I, Yanagibashi T, Taki A, Udagawa K, Miyagi E, Nakazawa T, et al. Uterine carcinosarcoma is derived from a single stem cell: an in vitro study. Int J Cancer. 1997;72(5):821–827. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970904)72:5<821::aid-ijc19>3.0.co;2-b. 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970904)72:5<821::aid-ijc19>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li L, Huang W, Xue K, Feng L, Han Y, Wang R, et al. Clinical and imaging features of carcinosarcoma of the uterus and cervix. Insights Imaging. 2021;12(1):142. doi: 10.1186/s13244-021-01084-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamishima Y, Takeuchi M, Kawai T, Kawaguchi T, Yamaguchi K, Takahashi N, et al. A predictive diagnostic model using multiparametric MRI for differentiating uterine carcinosarcoma from carcinoma of the uterine corpus. Jpn J Radiol. 2017;35(8):472–483. doi: 10.1007/s11604-017-0655-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bharwani N, Newland A, Tunariu N, Babar S, Sahdev A, Rockall AG, et al. MRI appearances of uterine malignant mixed mullerian tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195(5):1268–1275. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.4419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y, Ren H, Wang J. Outcome of adjuvant radiotherapy after total hysterectomy in patients with uterine leiomyosarcoma or carcinosarcoma: a SEER-based study. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):697. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-5879-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shinde A, Li R, Amini A, Chen YJ, Cristea M, Dellinger T, et al. Improved survival with adjuvant brachytherapy in stage IA endometrial cancer of unfavorable histology. Gynecol Oncol. 2018;151(1):82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2018.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cantrell LA, Havrilesky L, Moore DT, O'Malley D, Liotta M, Secord AA, et al. A multi-institutional cohort study of adjuvant therapy in stage I-II uterine carcinosarcoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127(1):22–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and/or its online supplementary material files. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.