Summary

Lyme neuroborreliosis (LNB), a tick-borne infection caused by spirochetes within the Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato (s.L.) complex, is among the most prevalent bacterial central nervous system (CNS) infections in Europe and the US. Here we have screened a panel of low-passage B. burgdorferi s.l. isolates using a novel, human-derived 3D blood-brain barrier (BBB)-organoid model. We show that human-derived BBB-organoids support the entry of Borrelia spirochetes, leading to swelling of the organoids and a loss of their structural integrity. The use of the BBB-organoid model highlights the organotropism between B. burgdorferi s.l. genospecies and their ability to cross the BBB contributing to CNS infection.

Subject areas: Neuroscience, Medical Microbiology, Cell biology

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Human derived blood-brain barrier organoids support Borrelia spp. invasion

-

•

Borrelia garinii preferentially invades organoids

-

•

Borrelia spp. exposure triggers a loss of tight junctions

-

•

Organoid structural integrity is significantly reduced after Borrelia spp. exposure

Neuroscience; Medical Microbiology; Cell biology

Introduction

Lyme borreliosis (LB), the most prevalent vector-borne infection in Europe and the US, is an emerging tick-borne infection caused by spirochetes belonging to the Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato (s.L.) complex. More than 20 different B. burgdorferi s.l. genospecies have been identified. Not all B. burgdorferi s.l. genospecies are known to be pathogenic to humans, whereas in the US B. burgdorferi sensu stricto (s.s.) is the predominant genospecies associated with LB. In Europe, Borrelia garinii and Borrelia afzelii are the most common genospecies in humans.1

The clinical manifestations of LB are diverse, with the expanding skin lesion, erythema migrans being the most common manifestation of LB. Dissemination of B. burgdorferi s.l. to the central nervous system (CNS) causing Lyme neuroborreliosis (LNB) has been reported to occur in approximately 10–15% of all cases of LB.1,2

Many aspects of the pathogenesis of LNB are still largely unknown, specifically how B. burgdorferi s.l. gains access to the CNS. Generally, dissemination to the CNS in humans is considered to occur through the bloodstream or along peripheral nerves.3,4 In Europe, early LNB in adults mainly manifests as a subacute painful meningoradiculitis and/or cranial nerve palsy and is typically associated with infection with B. garinii, which is particularly neurotropic.5,6 In contrast, the most frequent manifestation of LNB among patients in the US is lymphocytic meningitis caused by B. burgdorferi s.s. Thus, it is possible that the mechanism of dissemination to the nervous system is different in Europe and the US and depends on individual genospecies of B. burgdorferi s.l. and their ability to cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB).

The mechanism of how the spirochetes pass the BBB is not known although both paracellular and transcellular penetration, in addition to the spirochete-induced expression of plasminogen and metalloproteinases activators influencing the connections (tight-junctions) in the BBB have been proposed.3,4 However, further investigations to understand the pathogenesis of LNB are required but are limited by the lack of adequate animal models. Multiple animal types ranging from dogs, rhesus monkeys, New Zealand white rabbits, guinea pigs, and various strains of inbred mice have been used to model B. burgdorferi infection7,8,9,10; however, no single animal model fully recapitulates the disease progression observed in humans, and variation in responses between animal models is also observed.7 Recent studies using the C3H strain of inbred mice have demonstrated colonization of the dura mater during acute and late disseminated infection, however in human LNB, spirochetes have been observed perivascular, and within the parenchyma.14,15,16,17,18,19 To enter the brain, pathogens must first navigate the BBB; access can occur via direct transmigration such as that observed with Neisseria meningitidis,20,21 Plasmodium falciparum,22 or for example, Listeria monocytogenes that can either gain direct entry, or are transported indirectly via a trojan horse mechanism and carried across the BBB within infected leukocytes (reviewed in23). Growing evidence demonstrates the critical role of the BBB in neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric diseases. Multiple neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease have “leaky” barriers,24,25 whereas depressive disorders have also been shown to have altered permeability.26,27,28 Increasing our knowledge on how the spirochetal infection leads to the observed neural dysfunction, especially how B. burgdorferi s.l. crosses and impacts the BBB will be of paramount interest to not only understand the mechanisms driving the development of LNB, but for the development of preventative and adjunctive treatments. In addition, the ability of different clinical B. burgdorferi s.l. isolates to cross the BBB is unclear. To test this, we used a newly developed in vitro 3D BBB model and B. burgdorferi s.l. strains isolated from human patients.

Results

Blood-brain barrier-organoids support invasion by B. burgdorferi sensu lato spirochetes

To model LNB and investigate the effect of B. burgdorferi s.l. on the BBB, a 3D organoid model was employed. The organoids comprise brain endothelial cells, pericytes, and astrocytes with a distinct cellular orientation comparable to that of the in vivo BBB (Figure S1).29,30 To assess the impact of Borrelia on the BBB we used a panel containing eleven B. burgdorferi s.l. isolates isolated from clinical samples (skin biopsies or cerebrospinal fluid), and one a single B. burgdorferi s.s. isolate originated from an infected tick (Table 1). The isolates included five B. garinii (LNB associated), five B. afzelii (LB associated; erythema migrans), and two B. burgdorferi s.s. (LB associated; erythema migrans, or from a tick). The Borrelia spirochetes were maintained in culture under microaerobic conditions for seven days before staining with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE), because there are varying timepoints reported in the literature, co-incubation with the BBB-organoids was performed for 1, 4 and 24 h. CFSE was chosen to ensure no dye transfer from the spirochetes, unlike that observed with other dyes.31 Organoids were also mock treated with spirochete media, to ensure any observed changes where due to the borreliae, and not the change in media composition. At the earliest time point (1 h), only a few spirochetes were observed interacting with the organoids (Figure 1A); however, by 4 h, multiple individual spirochetes were observed interacting with the organoid surface for a single B. garinii isolate (LU116). With this isolate, spirochetes were observed perpendicular to the surface of the organoid (Figure 1B left panel inset). In contrast, the 24-h timepoint showed multiple B. garinii isolates (LU116, 118, 190, 190 luc, and 222) having many bacterial aggregates of varying sizes colonizing not only to the surface of the BBB-organoids, but also extending to depths of 20 μm within the organoid (Figure 1B right panel and C). Distinct, individual spirochetes were also visualized at depths of 82–101 μm within BBB-organoids (Figure 1D). Quantification of single Borrelia spirochetes was confounded due to aggregation (Figure 1C); therefore, we quantified invasion as sub-surface volume (μm3) of CFSE signal (Figure 2A). All five LNB associated B. garinii isolates had large volumes of CFSE signal below the surface of the BBB-organoids, whilst two of the B. afzelii isolates (LU68 and LU207) recorded some CFSE within the BBB-organoids (Figure 2A). They also showed evidence of diffuse, green-stained cells indicative of phagocytosis (Figure 2B).

Table 1.

Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato (complex) isolates used to generate experimental data

| Isolate | Genospecies | Geographic origin | Isolate origin | Clinical diagnosis | Passage no. | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ML23a | B.burgdorferi sensu stricto | USA | Tick | NA | NA | Ornstein et al.11 |

| HB19 | B.burgdorferi sensu stricto | USA | Blood | NA | NA | Ornstein et al.11 |

| LU58 | B. afzelii | Sweden | Skin | EMb | 6 | Ornstein et al.11 |

| LU68 | B. afzelii | Sweden | Skin | EMb | 6 | Ornstein et al.11 |

| LU81 | B. afzelii | Sweden | Skin | EMb | 7 | Ornstein et al.11 |

| LU171 | B. afzelii | Sweden | Skin | EMb | 5 | Ornstein et al.11 |

| LU207 | B. afzelii | Sweden | Skin | EMb | 6 | Ornstein et al.11 |

| LU116 | B. garinii | Sweden | Skin | EMb | 6 | Ornstein et al.11 |

| LU118 | B. garinii | Sweden | Skin | EMb | NA | Ornstein et al.11 |

| LU190 | B. garinii | Sweden | CSF | LNBc | NA | Ornstein et al.11 |

| LU190 lucd | B. garinii | Sweden | CSF | NA | NA | Steere et al.12 |

| LU222 | B. garinii | Sweden | CSF | LNBc | NA | Steere et al.12 |

EM, erythema migrans; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; LNB, Lyme neuroborreliosis; NA, not available.

B. burgdorferi sensu stricto/ML23 pBBE22luc gene transfected.13

Individuals diagnosed with EM were19–69 years of age.

Individuals diagnosed with LNB were 4–7 years of age.

B. garinii G1/pBBE22luc ectopically producing luciferase.

Figure 1.

Blood-brain barrier organoids support entry of Borrelia burgdorferi

(A) 3D Z-projections of blood-brain barrier (BBB)-organoids (Magnification ×20) stained for Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. (CFSE, green), nuclei (DAPI, blue) and actin cytoskeleton (phalloidin, red). Scale bar 100 μm.

(B left panel) Z-projection of BBB-organoid exposed to B. garinii LU116 for 4 h. White box and inset shows higher magnification image of single spirochete interacting with the surface of the organoid, lying perpendicular to the surface. Scale bar 100 μm.

(B right panel) Orthogonal view from 54 μm within the organoid. White box shows invaded spirochete in Z, X, and Y axis.

(C) Z-projections of BBB-organoids (magnification ×20) 24 h post-exposure to B. garinii LU116 showing the aggregation on the surface of each organoid. Each panel (A-D) shows a representative organoid from each group. ntotal organoids = 276.

Figure 2.

Volumetric quantification of sub-surface Borrelia burgdorferi within blood-brain barrier-organoids

(A) Graph plotting the total volume (μm3) of carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE) signal within the organoids after 24 h exposure to B. garinii, B. afzelii, and B. burgdorferi s. s.

(B) Maximum intensity Z-projection of CFSE signal from B. afzelii LU68 exposed organoid (magnification ×20). White asterisk denotes diffuse green stain indicative of phagocytosis. Scale bar 100 μm. ntotal organoids = 276.

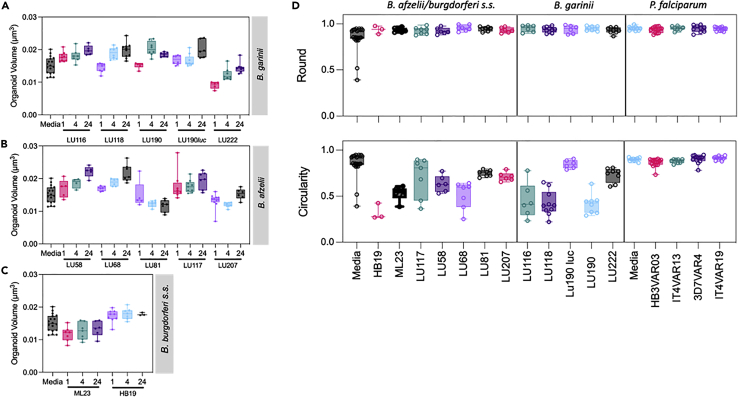

B. burgdorferi induce volumetric changes and alterations in organoid integrity postexposure

In LNB swelling of the meninges leads to meningitis.32 Recently, we demonstrated BBB-organoids to model the effect of the brain swelling observed in cerebral malaria, where parasites associated with cerebral malaria selectively altered the volume of organoids.22 Here we used a similar approach to determine the impact of Borrelia spirochetes on BBB-organoids, and we measured the volume, morphology (round), and integrity (circularity) of each organoid 24 h post-exposure (Figures 3A–3C). Although there was a clear distinction between the LNB and non-LNB isolates with their ability to enter the organoids, all isolates induced an increase in volume except for a single isolate (B. afzelii LU81) which showed a decrease post-exposure (Figures 3A–3C). Further morphometric analysis of the organoids demonstrated they retained their general morphology (round), while their cohesion (circularity) and structural integrity was impaired (Figure 3D). Circularity measurements drastically decreased compared to controls for all but one isolate (B. garinii LU190 luc). To determine if this was a specific response to the Borrelia bacteria, or generalized toward any pathogen, we analyzed the gross morphology of organoids exposed to erythrocytes infected by P. falciparum isolates associated with cerebral malaria (Figure 3D). We have previously shown these isolates to selectively disrupt the BBB and induce swelling.22 With P. falciparum-infected erythrocytes, we observed no alterations in the gross morphology of the organoids, and the roundness and circularity values were comparable to untreated controls, underpinning the observation that the negative responses by the organoids are specific to Borrelia exposure (Figure 3D). The B. burgdorferi s.l. exposed BBB-organoids presented with multiple fragmented nuclei and giant cells extending and detaching from the outer surface. The cellular cytoskeleton visualized with phalloidin showed multiple foci and irregular staining compared to the untreated control BBB-organoids (Figures 4A–4C).

Figure 3.

Morphometric analysis of blood-brain barrier-organoids post-exposure with Borrelia burgdorferi

The BBB organoids were co-incubated with ten different isolates of B. burgdorferi s. l., and two isolates of B. burgdorferi s. s. (Table 1), and red blood cells infected (IRBC) by four different P. falciparum lines.

Box and whisker plots, showing min/max values (A–D) of BBB-organoid volume (μm3). Graphs (A–C) showed alterations post-Borrelia exposure. The gross morphology of organoids was measured by organoid roundness, i.e., general shape (D top panel), or the circularity i.e., organoid integrity. (D bottom panel). BBB-organoids were also exposed to P. falciparum lines (D both panels). The P. falciparum lines associated with cerebral (HB3VAR03, PFD1235w) has been shown to cross the BBB of organoids, while malaria parasites associated with uncomplicated (IT4VAR13, IT4VAR19) malaria did not.22 ntotal organoids = 276 (Borrelia), ntotal organoids = 61 (P. falciparum).

Figure 4.

Internalization of Borrelia by blood-brain barrier-organoids

Blood-brain barrier (BBB)-organoids co-incubated with B. burgdorferi s. l. isolates.

(A) 3D Z-projection of organoids (magnification ×20) showing Carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE stained) Borrelia in green, nuclei in blue (DAPI), and actin in red (phalloidin). The organoids were exposed to neurotropic (B. garinii LU118) or non-neurotrophic (B. afzelii LU207 and LU68) spirochetes. Composite images show overlays of CSFE, DAPI, and phalloidin stained images.

(B) Orthogonal view of organoid exposed to B. garinii LU118.White filled arrows point toward a large aggregate of spirochetes extending from the surface and into the organoid.

(C) Z-projection of BBB-organoid (magnification ×63) showing giant cell (white arrow) extending from the surface. Open arrows point to actin foci (phalloidin, red), whilst the asterisk denotes B. garinii LU116 spirochetes extending from surface into the cell (CFSE, green). Scale bar 100 μm. ntotal spheroids = 276 total.

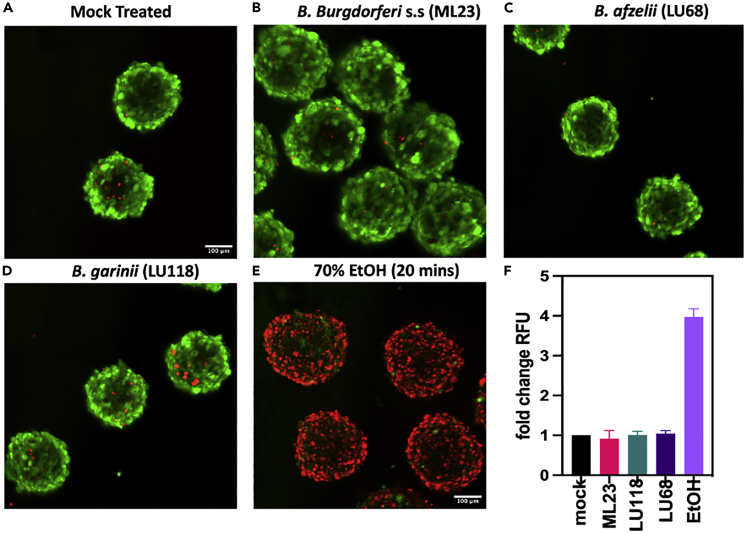

B. burgdorferi spirochetes result in loss of tight junctions but fail to trigger significant cell death in organoids

The gross morphological analysis of the organoids exposed to spirochetes demonstrated a loss of integrity (Figures 3A–3C). To determine if exposure was impacting the expression of tight-junctions, organoids were co-incubated for 24 h with spirochetes representing each of the groups tested (ML23, LU118, and LU68). After fixation, organoids were stained for the tight-junction protein ZO-1 and imaged with a confocal microscope. Mock treated controls showed intact tight junctions, with staining localized around the periphery of cells and within the cytosol (Figure 5A top panel). Organoids treated with VEGF (50 ng/mL) a known disruptor of tight junctions show diffuse staining in the cytosol and not at the periphery (Figure 5B middle panel). Line intensity plots show peak fluorescence intensity at the peripheral boundary of the organoid, with no fluorescence in the center (Figure 5, bottom panel). Organoids exposed to ML23, LU118, or LU68 spirochetes display a fluorescence pattern similar to VEGF treated organoids, where fluorescence intensity is low and diffuse, demonstrating that the junctions have been disrupted (Figures 5C–5E). Given the observed loss of integrity and tight junctions (Figures 3D and 5C-5E), a live/dead assay was performed to assess the degree of cell death among the organoids exposed to the different Borrelia spp. Organoids were exposed to ML23, LU118, or LU68 spirochetes for 24 h, then imaged with a confocal microscope. Live cells stain intensely green, and interestingly, spirochete exposed organoids showed little evidence of cell death (red stain) and were comparable to the mock treated organoids (Figures 6A–6D). In contrast, the negative control organoids that were treated with 70% ethanol (EtOH) for 20 min before staining show mostly dead cells (red, Figure 6E). Analysis of the fold change in fluorescence intensity confirms very little cell death between the mock treated controls or Borrelia-exposed organoids; while the EtOH treated organoids had an almost 4-fold increase in fluorescence intensity (Figure 6F).

Figure 5.

Spirochete exposure leads to a loss of tight junctions

Representative confocal images of organoids exposed to spirochetes for 24 h were fixed and then stained for the tight junction protein ZO-1 (green, AF488).

(A) Z-projection of mock treated organoids showing bright ZO-1 stain around the periphery of the cells and diffuse within the cytosol. The dashed line from slices imaged at 90 μm depth (middle panel) represents the position analyzed to generate the intensity plots of ZO-1 stain (bottom panel).

(B) Organoids exposed to vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), show disrupted tight junctions and diffuse stain, while those exposed to (C) B. burgdorferi s.s. ML23, (D) B. garinii LU118, or (E) B. afzelii LU68 show low intensity, diffuse stain (red, AF647) ntotal spheroids = 60 total. Scale bar = 100 μm.

Figure 6.

Live/Dead analysis of organoids post-spirochete exposure

(A–D) To determine the level of cell death post-spirochete exposure, organoids were treated with Live/Dead stain. Live cells in the organoids stain green, while dead cells stain red. Very few red stained are observed in the mock treated controls (A), or in the organoids exposed to (B) B. burgdorferi s.s. (B) ML23, (C) B. garinii LU118, or (D) B. afzelii LU68 spirochetes after 24 h co-incubation. The negative control organoids (E) were treated with 70% EtOH for 20 min and most cells were dead.

(F) plot showing the fold change in cell death compared to mock treated controls (+/−SD), with very little change post-spirochete exposure. ntotal spheroids = 60 total. Scale bar = 100 μm.

Discussion

BBB-organoids provide a unique opportunity to investigate the neurotropic properties of different pathogens. They are comprised of the same component cells found in vivo and can self-assemble within 48 h.29 Although they present with an “inside-out” cellular architecture compared to that found in vivo, they readily form tight junctions, control the passage of solutes, and with the endothelial cells exposed on the outer surface, making them ideal for investigating the effect pathogens have on the BBB.22 Previous studies combining BBB-organoids and P. falciparum infected red blood cells show malaria parasites are taken up by brain endothelial cells, causing breakdown of the BBB, and swelling of BBB-organoids.22,30 In this study, we show that Borrelia spirochetes readily enter the BBB-organoids and induce considerable alterations in both volume and integrity, and trigger loss of tight junctions. Of the panel of 12 isolates studied, all the B. garinii (5/5) genospecies readily colonized the BBB-organoid surface and invaded to depths of 20 μm. Single, intact spirochetes were observed even deeper at depths of 101 μm. In contrast, only two out of five B. afzelii entered the BBB-organoids. Indeed, there are reports of patients infected with B. afzelii presenting with LNB. There were several diffuse green cells observed within the BBB-organoids, indicating phagocytosis may have occurred. Exposure to any genospecies failed to trigger cell death in the organoids and though the integrity is significantly decreased, the cells within the organoids remain viable. Although endothelial cells, astrocytes, and pericytes important components of the BBB are not professional phagocytic cells, they are capable of clearing blood clots post-stroke and pathogens such as P. falciparum from their surface and extravasating them peri-vascularly.22,33 The remaining B. burgdorferi s.s. isolates, including the tick isolate, failed to interact with the surface or enter the BBB-organoids. This variability in infectivity suggests that different genospecies have a varied affinity for the ability to cross the BBB and this may reflect the differences observed in clinical presentation of LB between different geographical locations.34

The murine model has shown spirochetal entry into the meninges and induction of swelling.35 Here, the majority of investigations examining the interactions between borrelial proteins and host tissues have concentrated upon other regions of the body and using cell lines such as human umbilical vein (HUVEC) and human brain microvascular cells (HBMEC), or cell lines derived from non-human sources.35,36,37,38

While there was a clear difference in the ability to enter the BBB-organoids, all spirochetes irrespective of genotype triggered alteration in the gross morphology and integrity of the BBB-organoids. This is in stark contrast to organoids exposed to red blood cells infected with P. falciparum isolates associated with cerebral malaria, the most frequently fatal form of malaria. On exposure to P. falciparum-infected red blood cells BBB-organoids demonstrated BBB-dysfunction (increased permeability), but not a lack of cell integrity.22,39 Alterations in the actin cytoskeleton and nuclei are markers of cellular stress and inflammation and has been observed previously using endothelial monolayer experiments showing damage to cultured endothelial cells (HUVEC and HBMEC) after spirochete exposure.38,40,41 Monolayer studies also identified the upregulation and triggering of plasminogen and metalloproteases post-exposure to B. burgdorferi s.l. spirochetes, and the initiation of the fibrinolytic cascade may contribute to BBB-dysfunction.42,43

The exact mechanism for crossing the BBB is not fully understood, and both paracellular and transcellular entry have been proposed.42,44 Monolayer studies have identified a potential role for cell adhesion molecules such as E-selectin, ICAM-1, and VCAM-1, while other groups have implicated integrins and glycosaminoglycans such as heparan sulfate as playing a role.45,46,47 Others have proposed that in place of a direct receptor-ligand interaction, spirochetes trigger cytokine release by host cells such as endothelial cells or neutrophils. These molecules trigger the opening of tight junctions, leading to paracellular migration across the endothelial layer. In the murine model, the role of neutrophils has been shown, and mice devoid of neutrophils have limited extravasation when infected with borreliae.44 Our current model demonstrates the migration of B. garinii isolates in the absence of immune cells. Tan et al. used derivates from B. burgdorferi strain B31, a tick isolate from North America where LNB is a rarely diagnosed. The ability to migrate in the absence of immune cells might contribute to the differences between the North American and European clinical presentations of LB. To our knowledge, this is the first study using organoids and a large panel of low passage Borrelia isolates from different biological origin and clinical manifestations in humans for studying Borrelia spp. and their impact on the BBB. Using low passage isolates avoids the risk of plasmid loss and genomic alternations due to prolonged in vitro culturing. Previous literature demonstrated the ability of Borrelia spp. to invade endothelial cells from HUVEC and HBMEC in vitro,35,38 whereas murine infection studies also show organotropism, but use a limited number of isolates, or laboratory-adapted strains.36,48,49 In conclusion, BBB-organoids appear to be an ideal model for LNB - not only for studies of the cellular and molecular biological mechanisms of spirochetal invasion of the CNS, but their ease of use, rapid generation, and reproducibility also make them suitable for screening chemotherapeutics for the treatment of LNB.

Limitations of the study

This study investigates at a limited number of B. burgdorferi s.l isolates LNB and future work could expand on this by assessing more isolates originating from different geographic and biological origin, and particularly Borrelia isolates confirmed to cause LB like Borrelia bavariensis, Borrelia spielmanii. and Borrelia mayonii, respectively. The BBB-organoids used for this study lack immune cells such as microglia, or other cells like oligodendrocytes which can contribute to the integrity of the BBB, and act as phagocytic cells in response to pathogens or damage.50,51,52,53 While not the focus of this study, the model is expandable and to date a maximum of six different cell types have been cultured in tandem, including microglia and oligodendrocytes.54,55 Taken together, these data highlight the usefulness of BBB-organoids for the investigation of neurotropic pathogens such as B. burgdorferi s.l.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| HB19 | Sven Bergström and Katharina Ornstein | N/A |

| ML23 | Professor John Skare | N/A |

| LU58 | Sven Bergström and Katharina Ornstein | N/A |

| LU68 | Sven Bergström and Katharina Ornstein | N/A |

| LU171 | Sven Bergström and Katharina Ornstein | N/A |

| LU207 | Sven Bergström and Katharina Ornstein | N/A |

| LU116 | Sven Bergström and Katharina Ornstein | N/A |

| LU118 | Sven Bergström and Katharina Ornstein | N/A |

| LU190 | Sven Bergström and Katharina Ornstein | N/A |

| LU190 luciferase | Professor Peter Kraiczy | N/A |

| LU222 | Sven Bergström and Katharina Ornstein | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Celltrace CFSE cell proliferation kit | Thermofisher | C34554 |

| Phalloidin | Merck | P1951;RRID:AB_2315148 |

| DAPI | Merck | D9542 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| hCMEC/D3 | Cederland Labs | CLU512;RRID:CVCL_U985 |

| Astrocytes | Neuromics | HMP202 |

| Pericytes | Neuromics | HMP104 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Fiji | open source | https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2019 |

| GraphPad Prism v9.5.0 | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/ |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests may be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact Yvonne Adams, yadams@sund.ku.dk (Y.A.).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new, unique reagents. The strains provided by Professor Sven Bergström were a kind gift for the purposes of the manuscript and ownership is retained by Professor Bergström.

Experimental model and subject details

B. burgdorferi sensu lato and sensu stricto strains

A panel of 12 B. burgdorferi s.l. patient isolates (Table 1) comprising different genotypes isolated from skin biopsies or cerebrospinal fluid was assessed. The genotypes included five B. garinii (LNB), five B. afzelii (LB), and two B. burgdorferi s.s. (LB). The Borrelia spirochetes were cultured in Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly medium (BSK-H) supplemented with 6% rabbit serum (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) under conventional microaerobic conditions (1–5% CO2, 33°C) created in OxoidTM Compact Plastic Pouches (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) with a OxoidTM CampygenTM Compact sachet (Thermo Fisher Scientific), sealed airtight with a sealing clip.56 Growth was recorded using dark-field microscopy.

Malaria parasites

The P. falciparum lines selected for surface expression of specific P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1) molecules (P. falciparum 3D7 expressing PFD1235w, HB3 expressing HB3VAR03, and IT4 expressing IT4VAR13 or IT4VAR19) were maintained in in vitro blood culture and were selected using antibodies against DBLβ_D4 domains of specific PfEMP1s as previously described.22,39,57,58 Phenotypes were verified by flow cytometry and Q-PCR as previously described.39,57,58,59,60

Human cell cultures

The human brain microvascular endothelial cell line (hCMEC)/D3 (CLU512, Cedarlane Labs, CA.) was maintained on collagen-coated (50 μg/mL, rat tail type I, BD Biosciences) flasks and grown in VascuLife VEGF – Mv media (LL0005, CellSystems) supplemented with rhVEGF (5 ng/mL), rhEGF (5 ng/mL), rhFGF (5 ng/mL), rhIGF-1 (15 ng/mL), L-Glutamine (10 mM), hydrocortisone hemisuccinate (1 μg/mL), heparin sulphate (0.75 U/mL), ascorbic acid (50 μg/mL), fetal bovine serum (FBS, 5%), 10,000 U/mL penicillin, 10,000 μg/mL streptomycin, and 25 μg/mL amphotericin B. Primary human brain microvascular pericytes and astrocytes (Neuromics, USA), were maintained on poly-L-lysine (10 μg/mL) coated flasks with pericyte (HMP104) and astrocyte (PGB003) growth medium (Neuromics). Astrocytes and pericytes were used at passages 3–5 and hCMEC/D3 at passage 27–29.

Method details

Blood-brain barrier-organoids

Human pericytes, primary astrocytes, and hCMEC/D3 released by 0.025% trypsin/EDTA (Sigma Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO) were resuspended in BBB-working medium (Vasculife-Mv supplemented with 2% normal human serum with antibiotics omitted), and 1.5 ×103 of each cell type (final volume of 100 μL/well) were seeded onto sterile 1% w/v solid agarose (Sigma) pre-dispensed into low binding 96-well plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific). A further 100 μL of BBB working media (BBBM) was added to bring the volume in each well to a total of 200 μL. Multicellular BBB organoids were allowed to self-assemble (48–72 h) in a humidified 5% CO2-incubator at 37°C.22,30 The orientation of the component cells was determined by pre-staining astrocytes with 1μM CellTrace Far Red (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 20minat 37°C in the dark prior to assembling organoids. Staining for CD31 on endothelial cells and NG2 on pericytes was performed post-formation. Once organoids formed, they were washed, pooled, and fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde for 10 min prior to staining for 45 min with anti-CD31 (1:200, R&D Systems) and anti-NG2 (1:200, Millipore) post-permeabilization with 0.1% Triton X-100. The receptors were visualized with anti-mouse-IgG Alexa Fluor 450 (CD31) and anti-rabbit-IgG Alexa Flour 488 (NG2). Images were captured with Zeiss LSM 780 and line plot analysis conducted in Fiji.

Co-culture of Borrelia spp. and 3D blood-brain barrier-organoids

Borrelia isolates were grown in 5 mL BSK-H medium for 7 days prior to assay. On day 7, spirochetes were stained with 5 μM Syto 9 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and with 5 μM Syto 60 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) before determination of the cell density using flow cytometry.61 The bacteria were washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), centrifuged 3minat 5500 × g, and resuspended in CFSE (Invitrogen) in PBS (500 μL) was added to a final concentration of 5 μM CFSE and incubated 10 min in the dark at room temperature. Spirochetes were washed twice with PBS containing 5% FBS adjusted to 30,000 B. burgdorferi s.l./well in BBBM and BSK-H medium (1:1 ratio). Spirochetes were added (100 μL/well) and incubated at 37°C for 1, 4, and 24 h. At the end of the assay, organoids were pooled in groups, then washed in PBS and fixed for 10 min in 3.7% v/v formaldehyde. The organoids were transferred to 12-well chamber slides (Ibidi, Germany), following incubation with Phalloidin and DAPI (300 nM), prior to being imaged with a Zeiss LSM 780 confocal microscope (Zeiss, Germany). Z-stacks were captured to 102.8 μm depth at 2.32 μm intervals (×10). To determine the amount of B. burgdorferi s.l. sp. within each organoid, the color channels were split in Fiji, and the 3D objects counter was deployed to calculate the volume of CFSE signal (green channel) throughout the Z-stack. The volume was calculated for each organoid and expressed as total CFSE volume (μm3) per organoid. The volume of individual organoids (mm3), circularity, and roundness were calculated from (×20) brightfield images at 102.8 μm depth from diameter measurements generated in Fiji.62 To calculate volume, the following equation was used, V = 4/3πr3. To calculate circularity the following equation was used 4π∗area/perimeter2, while roundness is calculated using the following formula - 4∗area/(π∗major axis)2.

Tight junction protein ZO-1 immunofluorescence and live/dead staining

Organoids were exposed to Borrelia spp. for 24 h, then pooled in groups and washed in PBS before fixing for 10 min in 3.7% v/v formaldehyde. Organoids were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 min, before washing (PBS + 5% goat serum) prior to staining with anti-ZO-1 (Thermo Fisher) 1:200 for 45 min. The organoids were then washed (PBS+5% goat serum) before incubating for 45 min in the dark with anti-goat Alexa Fluor 488, or Alexa Fluor 647 at room temperature. Organoids were washed, incubated with DAPI (300 nM), then transferred to 12-well chamber slides (Ibidi, Germany) prior to being imaged a Zeiss LSM 780 confocal microscope (Zeiss, Germany). Z-stacks were captured to 102.8 μm depth at 2.32 μm intervals (×10). The amount of cell death post-spirochete exposure was determined using Live/Dead stain (Thermo Fisher). The positive control group were pre-treated for 20 min with 70% EtOH prior to staining to kill the organoids. Images were captured using Zeiss LSM780 confocal microscope. Line plot analysis was performed on the resulting images using Fiji.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Confocal images were analyzed using Fiji and results plotted with GraphPad Prism 9. Specific information for each experiment can be found in the figure legends.

Additional resources

This paper did not create any additional resources.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mette Ulla Madsen and the Core Facility for Integrated Microscopy, Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen for excellent technical assistance. We also thank Professor Sven Bergström, Umeå University, Sweden, for kindly providing the clinical isolates of B. burgdorferi s.l. and Professor Jon Skare, Texas A&M University, USA for providing the plasmid pBBE22luc. The research performed at the Centre for Medical Parasitology, University of Copenhagen was supported by grants from the Danish Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Fisheries (3R-Center Research Grant), and the Lundbeck Foundation (R180-2014-3098, R313-2019-322 and R324-2019-2029). The research performed at the Department of Infectious Diseases, University Hospital, Rigshospitalet was supported by a grant from the Lundbeck Foundation (R366-2021-127). This study was partially supported by a grant of the European Union through the European Regional DevelopmentFund and the Interreg NorthSea Region Program 2014–2020 as part of the NorthTick project (reference number J-No: 38-2-7-19).

Author contributions

A.R.J., Y.A., A.S.C., and A.M. L. were responsible for planning of experiments. A.R.J., Y.A., and A.M.L. were responsible for writing the manuscript A.R.J. and Y.A. were responsible for data interpretation and funding acquisition. A.R.J. was responsible for project strategy and management. Y.A. did the organoid production, performed experiments, and microscopy. P.W., A.H., M.L., P.E.L., P.K., A.K., and A.M.L. were responsible for the panel of B. burgdorferi ss./s.l. strains, A.S.C., M.L., K.N.K., and T.B. did the culturing. P.Ø.J. did the flow cytometry. All authors have critically reviewed the data and commented on the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

Disclosures: Outside of the present work: A.M.L. reports speaker’s honorarium/travel grants and advisory board activity from Gilead, GSK, and Pfizer. The other authors declare no competing interests exist. P.E.L. has been an external scientific expert to Valneva Austria GmbH and Pfizer Inc. and received speaker’s honorarium and travel grants.

Published: January 20, 2023

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2022.105838.

Contributor Information

Yvonne Adams, Email: yadams@sund.ku.dk.

Anja R. Jensen, Email: atrj@sund.ku.dk.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

-

•

All data is reported and available in this paper.

-

•

This paper does not use or report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

References

- 1.Kullberg B.J., Vrijmoeth H.D., van de Schoor F., Hovius J.W. Lyme borreliosis: diagnosis and management. BMJ. 2020;369:m1041. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berglund J., Eitrem R., Ornstein K., Lindberg A., Ringér A., Elmrud H., Carlsson M., Runehagen A., Svanborg C., Norrby R. An epidemiologic study of Lyme disease in southern Sweden. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;333:1319–1327. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511163332004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rupprecht T.A., Koedel U., Fingerle V., Pfister H.-W. The pathogenesis of Lyme neuroborreliosis: from infection to inflammation. Mol. Med. 2008;14:205–212. doi: 10.2119/2007-00091.Rupprecht. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garcia-Monco J.C., Benach J.L. Lyme neuroborreliosis: clinical outcomes, controversy, pathogenesis, and polymicrobial infections. Ann. Neurol. 2019;85:21–31. doi: 10.1002/ana.25389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hansen K., Lebech A.-M. The Clinical and Epidemiological profile of Lyme Neuroborreliosis in Denmark 1985-1990: a prospective study of 187 patients with Borrelia burgdorferi specific intrathecal antibody production. Brain. 1992;115:399–423. doi: 10.1093/brain/115.2.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hansen K., Crone C., Kristoferitsch W. In: Handbook of Clinical Neurology Peripheral Nerve Disorders. Said G., Krarup C., editors. Elsevier; 2013. Chapter 32 - Lyme neuroborreliosis; pp. 559–575. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurokawa C., Narasimhan S., Vidyarthi A., Booth C.J., Mehta S., Meister L., Diktas H., Strank N., Lynn G.E., DePonte K., et al. Repeat tick exposure elicits distinct immune responses in Guinea pigs and mice. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2020;11:101529. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2020.101529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Batool M., Hillhouse A.E., Ionov Y., Kochan K.J., Mohebbi F., Stoica G., Threadgill D.W., Zelikovsky A., Waghela S.D., Wiener D.J., Rogovskyy A.S. New Zealand white rabbits effectively clear Borrelia burgdorferi B31 despite the bacterium’s functional vlsE antigenic variation system. Infect. Immun. 2019;87:e00164–e00219. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00164-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foley D.M., Gayek R.J., Skare J.T., Wagar E.A., Champion C.I., Blanco D.R., Lovett M.A., Miller J.N. Rabbit model of Lyme borreliosis: erythema migrans, infection-derived immunity, and identification of Borrelia burgdorferi proteins associated with virulence and protective immunity. J. Clin. Invest. 1995;96:965–975. doi: 10.1172/JCI118144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Appel M.J., Allan S., Jacobson R.H., Lauderdale T.L., Chang Y.F., Shin S.J., Thomford J.W., Todhunter R.J., Summers B.A. Experimental Lyme disease in dogs produces arthritis and persistent infection. J. Infect. Dis. 1993;167:651–664. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.3.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ornstein K., Berglund J., Nilsson I., Norrby R., Bergström S. Characterization of Lyme Borreliosis Isolates from Patients with Erythema Migrans and Neuroborreliosis in Southern Sweden. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2001;39:1294–1298. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.4.1294-1298.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steere A.C., Grodzicki R.L., Kornblatt A.N., Craft J.E., Barbour A.G., Burgdorfer W., Schmid G.P., Johnson E., Malawista S.E. The Spirochetal Etiology of Lyme Disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 1983;308:733–740. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198303313081301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hyde J.A. Borrelia burgdorferi Keeps Moving and Carries on: A Review of Borrelial Dissemination and Invasion. Frontiers in Immunology. 2017;8 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Casselli T., Divan A., Vomhof-DeKrey E.E., Tourand Y., Pecoraro H.L., Brissette C.A. A murine model of Lyme disease demonstrates that Borrelia burgdorferi colonizes the dura mater and induces inflammation in the central nervous system. PLoS Pathog. 2021;17:e1009256. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Divan A., Casselli T., Narayanan S.A., Mukherjee S., Zawieja D.C., Watt J.A., Brissette C.A., Newell-Rogers M.K. Borrelia burgdorferi adhere to blood vessels in the dura mater and are associated with increased meningeal T cells during murine disseminated borreliosis. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0196893. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gadila S.K.G., Rosoklija G., Dwork A.J., Fallon B.A., Embers M.E. Detecting Borrelia spirochetes: a case study with validation among autopsy specimens. Front. Neurol. 2021;12:628045. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.628045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacDonald A.B. Borrelia in the brains of patients dying with dementia. JAMA. 1986;256:2195–2196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacDonald A.B., Miranda J.M. Concurrent neocortical borreliosis and Alzheimer’s disease. Hum. Pathol. 1987;18:759–761. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(87)80252-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miklossy J., Kasas S., Zurn A.D., McCall S., Yu S., McGeer P.L. Persisting atypical and cystic forms of Borrelia burgdorferiand local inflammation in Lyme neuroborreliosis. J. Neuroinflammation. 2008;5:40. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-5-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dupin N., Lecuyer H., Carlotti A., Poyart C., Coureuil M., Chanal J., Schmitt A., Vacher-Lavenu M.-C., Taha M.-K., Nassif X., Morand P.C. Chronic meningococcemia cutaneous lesions involve meningococcal perivascular invasion through the remodeling of endothelial barriers. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;54:1162–1165. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kolappan S., Coureuil M., Yu X., Nassif X., Egelman E.H., Craig L. Structure of the Neisseria meningitidis Type IV pilus. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:13015. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adams Y., Olsen R.W., Bengtsson A., Dalgaard N., Zdioruk M., Satpathi S., Behera P.K., Sahu P.K., Lawler S.E., Qvortrup K., et al. Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 variants induce cell swelling and disrupt the blood–brain barrier in cerebral malaria. J. Exp. Med. 2021;218:e20201266. doi: 10.1084/jem.20201266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Disson O., Lecuit M. Targeting of the central nervous system by Listeria monocytogenes. Virulence. 2012;3:213–221. doi: 10.4161/viru.19586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hussain B., Fang C., Chang J. Blood–brain barrier breakdown: an emerging biomarker of cognitive impairment in normal aging and dementia. Front. Neurosci. 2021;15:688090. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2021.688090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al-Bachari S., Naish J.H., Parker G.J.M., Emsley H.C.A., Parkes L.M. Blood–brain barrier leakage is increased in Parkinson’s disease. Front. Physiol. 2020;11:593026. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.593026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kamintsky L., Cairns K.A., Veksler R., Bowen C., Beyea S.D., Friedman A., Calkin C. Blood-brain barrier imaging as a potential biomarker for bipolar disorder progression. Neuroimage Clin. 2020;26:102049. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2019.102049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dudek K.A., Dion-Albert L., Lebel M., LeClair K., Labrecque S., Tuck E., Ferrer Perez C., Golden S.A., Tamminga C., Turecki G., et al. Molecular adaptations of the blood–brain barrier promote stress resilience vs. depression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:3326–3336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1914655117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dion-Albert L., Cadoret A., Doney E., Kaufmann F.N., Dudek K.A., Daigle B., Parise L.F., Cathomas F., Samba N., Hudson N., et al. Vascular and blood-brain barrier-related changes underlie stress responses and resilience in female mice and depression in human tissue. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:164. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-27604-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Urich E., Patsch C., Aigner S., Graf M., Iacone R., Freskgård P.O. Multicellular self-assembled spheroidal model of the blood brain barrier. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:1500. doi: 10.1038/srep01500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cho C.-F., Wolfe J.M., Fadzen C.M., Calligaris D., Hornburg K., Chiocca E.A., Agar N.Y.R., Pentelute B.L., Lawler S.E. Blood-brain-barrier spheroids as an in vitro screening platform for brain-penetrating agents. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:15623. doi: 10.1038/ncomms15623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adams Y., Jensen A.R. In: Malaria Immunology: Targeting the Surface of Infected Erythrocytes Methods in Molecular Biology. Jensen A.T.R., Hviid L., editors. Springer US); 2022. 3D organoid assay of the impact of infected erythrocyte adhesion on the blood–brain barrier; pp. 587–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramesh G., Didier P.J., England J.D., Santana-Gould L., Doyle-Meyers L.A., Martin D.S., Jacobs M.B., Philipp M.T. Inflammation in the pathogenesis of Lyme neuroborreliosis. Am. J. Pathol. 2015;185:1344–1360. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2015.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lam C.K., Yoo T., Hiner B., Liu Z., Grutzendler J. Embolus extravasation is an alternative mechanism for cerebral microvascular recanalization. Nature. 2010;465:478–482. doi: 10.1038/nature09001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andreasen A.M., Dehlendorff P.B., Knudtzen F.C., Bødker R., Kjær L.J., Skarphedinsson S. Spatial and temporal patterns of Lyme neuroborreliosis on funen, Denmark from 1995–2014. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:7796. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-64638-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grab D.J., Nyarko E., Nikolskaia O.V., Kim Y.V., Dumler J.S. Human brain microvascular endothelial cell traversal by Borrelia burgdorferi requires calcium signaling. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2009;15:422–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2009.02869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Caine J.A., Coburn J. A short-term Borrelia burgdorferi infection model identifies tissue tropisms and bloodstream survival conferred by adhesion proteins. Infect. Immun. 2015;83:3184–3194. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00349-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Embers M.E., Hasenkampf N.R., Jacobs M.B., Tardo A.C., Doyle-Meyers L.A., Philipp M.T., Hodzic E. Variable manifestations, diverse seroreactivity and post-treatment persistence in non-human primates exposed to Borrelia burgdorferi by tick feeding. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0189071. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Comstock L.E., Thomas D.D. Characterization of Borrelia burgdorferi invasion of cultured endothelial cells. Microb. Pathog. 1991;10:137–148. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(91)90074-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lennartz F., Adams Y., Bengtsson A., Olsen R.W., Turner L., Ndam N.T., Ecklu-Mensah G., Moussiliou A., Ofori M.F., Gamain B., et al. Structure-guided identification of a family of dual receptor-binding PfEMP1 that is associated with cerebral malaria. Cell Host Microbe. 2017;21:403–414. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gergel E.I., Furie M.B. Activation of endothelium by Borrelia burgdorferi in vitro enhances transmigration of specific subsets of T lymphocytes. Infect. Immun. 2001;69:2190–2197. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.4.2190-2197.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tkáčová Z., Bhide K., Mochnáčová E., Petroušková P., Hruškovicová J., Kulkarni A., Bhide M. Comprehensive mapping of the cell response to Borrelia bavariensis in the brain microvascular endothelial cells in vitro using RNA-seq. Front. Microbiol. 2021;12:760627. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.760627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grab D.J., Perides G., Dumler J.S., Kim K.J., Park J., Kim Y.V., Nikolskaia O., Choi K.S., Stins M.F., Kim K.S. Borrelia burgdorferi, host-derived proteases, and the blood-brain barrier. Infect. Immun. 2005;73:1014–1022. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.2.1014-1022.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gebbia J.A., Monco J.C., Degen J.L., Bugge T.H., Benach J.L. The plasminogen activation system enhances brain and heart invasion in murine relapsing fever borreliosis. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;103:81–87. doi: 10.1172/JCI5171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tan X., Petri B., DeVinney R., Jenne C.N., Chaconas G. The Lyme disease spirochete can hijack the host immune system for extravasation from the microvasculature. Mol. Microbiol. 2021;116:498–515. doi: 10.1111/mmi.14728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sellati T.J., Abrescia L.D., Radolf J.D., Furie M.B. Outer surface lipoproteins of Borrelia burgdorferi activate vascular endothelium in vitro. Infect. Immun. 1996;64:3180–3187. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3180-3187.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ebnet K., Brown K.D., Siebenlist U.K., Simon M.M., Shaw S. Borrelia burgdorferi activates nuclear factor-kappa B and is a potent inducer of chemokine and adhesion molecule gene expression in endothelial cells and fibroblasts. J. Immunol. 1997;158:3285–3292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Böggemeyer E., Stehle T., Schaible U.E., Hahne M., Vestweber D., Simon M.M. Borrelia burgdorferi upregulates the adhesion molecules E-selectin, P-selectin, ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 on mouse endothelioma cells in vitro. Cell Adhes. Commun. 1994;2:145–157. doi: 10.3109/15419069409004433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin Y.-P., Tan X., Caine J.A., Castellanos M., Chaconas G., Coburn J., Leong J.M. Strain-specific joint invasion and colonization by Lyme disease spirochetes is promoted by outer surface protein C. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16:e1008516. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coburn J., Medrano M., Cugini C. Borrelia burgdorferi and its tropisms for adhesion molecules in the joint. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol. 2002;14:394–398. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200207000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hanisch U.-K., Kettenmann H. Microglia: active sensor and versatile effector cells in the normal and pathologic brain. Nat. Neurosci. 2007;10:1387–1394. doi: 10.1038/nn1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Greenmyer J.R., Gaultney R.A., Brissette C.A., Watt J.A. Primary human microglia are phagocytically active and respond to Borrelia burgdorferi with upregulation of chemokines and cytokines. Front. Microbiol. 2018;9:811. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kimura I., Dohgu S., Takata F., Matsumoto J., Watanabe T., Iwao T., Yamauchi A., Kataoka Y. Oligodendrocytes upregulate blood-brain barrier function through mechanisms other than the PDGF-BB/PDGFRα pathway in the barrier-tightening effect of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells. Neurosci. Lett. 2020;715:134594. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2019.134594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bradl M., Lassmann H. Oligodendrocytes: biology and pathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2010;119:37–53. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0601-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kumarasamy M., Sosnik A. Heterocellular spheroids of the neurovascular blood-brain barrier as a platform for personalized nanoneuromedicine. iScience. 2021;24:102183. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.102183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sokolova V., Mekky G., van der Meer S.B., Seeds M.C., Atala A.J., Epple M. Transport of ultrasmall gold nanoparticles (2 nm) across the blood–brain barrier in a six-cell brain spheroid model. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:18033. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-75125-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hubálek Z., Halouzka J., Heroldová M. Growth temperature ranges of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato strains. J. Med. Microbiol. 1998;47:929–932. doi: 10.1099/00222615-47-10-929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Olsen R.W., Ecklu-Mensah G., Bengtsson A., Ofori M.F., Kusi K.A., Koram K.A., Hviid L., Adams Y., Jensen A.T.R. Acquisition of IgG to ICAM-1-binding DBLβ domains in the Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 antigen family varies between Groups A, B and C. Infect. Immun. 2019;87:e00224–e00319. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00224-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bengtsson A., Joergensen L., Rask T.S., Olsen R.W., Andersen M.A., Turner L., Theander T.G., Hviid L., Higgins M.K., Craig A., et al. A novel domain cassette identifies Plasmodium falciparum PfEMP1 proteins binding ICAM-1 and is a target of cross-reactive, adhesion-inhibitory antibodies. J. Immunol. 2013;190:240–249. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lennartz F., Bengtsson A., Olsen R.W., Joergensen L., Brown A., Remy L., Man P., Forest E., Barfod L.K., Adams Y., et al. Mapping the binding site of a cross-reactive Plasmodium falciparum PfEMP1 monoclonal antibody inhibitory of ICAM-1 binding. J. Immunol. 2015;195:3273–3283. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Joergensen L., Bengtsson D.C., Bengtsson A., Ronander E., Berger S.S., Turner L., Dalgaard M.B., Cham G.K.K., Victor M.E., Lavstsen T., et al. Surface Co-expression of two different PfEMP1 antigens on single Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes facilitates binding to ICAM1 and PECAM1. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001083. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Skovsbo Clausen A., Ørbæk M., Renee Pedersen R., Oestrup Jensen P., Lebech A.-M., Kjaer A. 64Cu-DOTATATE positron emission tomography (PET) of Borrelia burgdorferi infection: in vivo imaging of macrophages in experimental model of Lyme arthritis. Diagnostics. 2020;10:790. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics10100790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schindelin J., Arganda-Carreras I., Frise E., Kaynig V., Longair M., Pietzsch T., Preibisch S., Rueden C., Saalfeld S., Schmid B., et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

-

•

All data is reported and available in this paper.

-

•

This paper does not use or report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.