Abstract

Introduction

As new treatments are becoming available for patients with myasthenia gravis (MG), it is worth reflecting on the actual status of MG treatment to determine which patients would most likely benefit from the new treatments.

Methods

We reviewed the clinical files of all MG patients seen at the Department of Neurology of the Antwerp University Hospital during the years 2019, 2020 and 2021.

Results

163 patients were included. Age at diagnosis varied from the first to the eighth decades, with a peak of incidence from 60 to 70 years for both genders, and an additional peak from 20 to 30 years in women. Diplopia and ptosis were by far the most common onset symptom. At maximum disease severity, 24% of the patients still had purely ocular symptoms and 4% needed mechanical ventilation. 97% of the patients received a treatment with pyridostigmine and 68% with corticosteroids, often in combination with immunosuppressants. More than half reported side effects. At the latest visit, 50% of the patients were symptom-free. Also, half of the symptomatic patients were fulltime at work or retired with no or mild limitations in daily living. The remaining patients were working part-time, on sick leave, or retired with severe limitations.

Discussion and conclusion

The majority of MG patients are doing well with currently available treatments, but often at the cost of side effects in the short and in the long term. A significant group is in need of better treatments.

Keywords: Myasthenia gravis, Treatment, Autoantibodies, Electromyography

Introduction

This is an exciting time for patients with myasthenia gravis (MG) and their physicians, as several new treatments with new mechanisms of action passed clinical trials and will be available shortly [1].

MG is the most common disorder affecting the neuromuscular junction [2]. It is an autoimmune disease in which autoantibodies are directed against proteins in the postsynaptic membrane, mainly against the acetylcholine receptor (AChR). Despite the existence of symptomatic and several immunomodulatory therapies that resulted in a dramatic decrease of mortality [3], a group of patients are resistant to treatment and the disease has a severe impact on their quality of life [4].

It is important to elucidate which patients could benefit from these new therapies to design treatment protocols. Data on the evolution of MG in the Belgian population under the currently available treatments, their efficacy and their side effects is not available.

Therefore, we retrospectively reviewed the files of all MG patients seen at the Neurology Department of Antwerp University Hospital during the years 2019, 2020 and 2021.

Materials and methods

We reviewed the files of all patients who had a neurology consultation in 2019, 2020 and 2021 with a diagnosis of MG or with suspicion of MG. The diagnosis of MG was retained in patients with compatible symptoms and supported by the presence of autoantibodies against AChR or muscle specific kinase (MuSK) and/or disturbed neuromuscular transmission on electromyography (EMG). In a few patients, the diagnosis was based on typical symptoms, exclusion of other pathology and sustained reaction to pyridostigmine or prednisolone. Patients with congenital myasthenic syndrome, patients with Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome and thymoma patients without symptoms or signs of myasthenia were not included.

The patients were classified according to the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America (MGFA) clinical classification at both the time of diagnosis and at the moment of maximum disease severity [5]. At the latest visit, we identified patients without symptoms of MG and with normal clinical examination, including patients in complete stable remission and pharmacological remission according to the MGFA-Post Intervention Scale (PIS) [5]. Patients with minimal manifestations (no symptoms but minor abnormalities upon clinical examination) were also identified. The remaining patients were classified according to their MGFA class at last visit.

AChR antibodies were assayed with the radioimmunoassay of RSR Ltd. at the Leiden University Hospital in the majority of patients, and with a commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay of Euroimmun in a minority. A few patients had a cell based assay with combined testing of antibodies against AChR, MuSK and low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 4 (LRP4) in Oxford [6].

EMG tests of neuromuscular transmission included repetitive nerve stimulations and jitter measurements with a concentric needle electrode under axonal stimulation [7]. For simplicity this latter test is called single fiber electromyography (SFEMG) in this paper.

Results

Patients

The diagnosis of myasthenia gravis was retained in 163 patients.

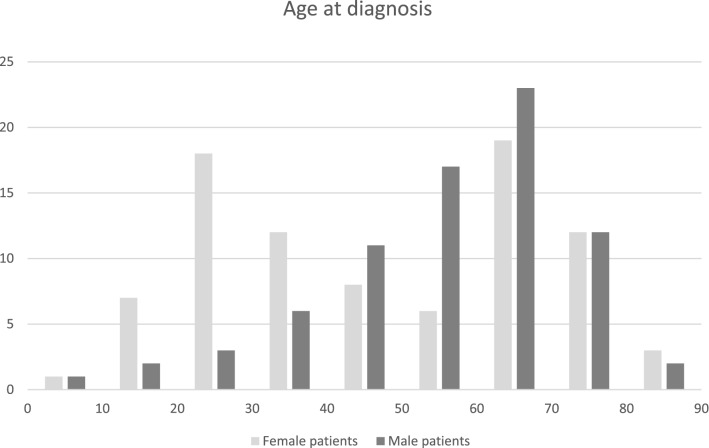

The sex and age at diagnosis are shown in Fig. 1. There was a slight preponderance of women (53%). The majority of patients (58%) were older than 50 years at diagnosis and there was an age peak between 60 and 70 in both sexes. Only women had a second age peak between 20 and 30.

Fig.1.

Age at diagnosis. Horizontal axis age in years, vertical axis number of patients

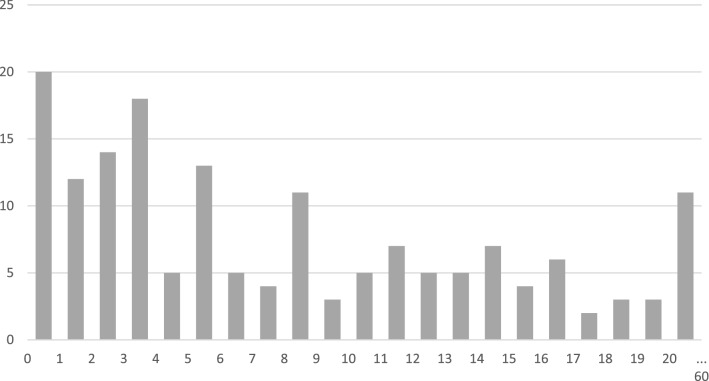

The first symptom is presented in Fig. 2. Ptosis and diplopia are by far the most frequent onset symptoms: together 71% (115 patients). Dysarthria, dysphagia, and weakness in the arms were the onset symptom in 8, 6 and 7% respectively. A few patients started with respiratory problems, facial weakness, and weakness in the legs. The median interval between first symptom and diagnosis was 2 months, and the 90th percentile was 12 months. In one exceptional case the interval was 30 years.

Fig. 2.

First symptom in 163 patients

At the time of diagnosis 63 patients (39%) belonged to MGFA class 1 with purely ocular symptoms (Fig. 3), while diplopia and/or ptosis were the onset symptom in 115 patients (71%). This indicates that 52 patients (45.2%) who started with ocular symptoms evolved to a generalized form in the first weeks or months, between onset and diagnosis. In 24 patients symptoms that were not ocular appeared between diagnosis and maximum disease severity. The time interval for generalization varied between 1 and 112 months.

Fig. 3.

MGFA clinical classification at time of diagnosis, maximum disease severity and last visit. Class 1 indicates only ocular weakness, classes 2, 3 and 4 indicate, respectively, mild, moderate and severe generalized weakness with ocular and limb predominance in “a” and bulbar and respiratory predominance in “b”. Class 5 indicates intubation for ventilation. At the last visit, patients with no MG symptoms and normal clinical examination were attributed to a fictive MGFA class 0

At maximum disease severity, 39 patients (24%) were still in MGFA class 1. There was an increase of patients in the more severe groups 3 and 4. 7 patients (4%) needed intubation for artificial ventilation (MGFA class 5).

The time interval between diagnosis and last visit is shown in Fig. 4. The median follow-up was 71 months, with a range of 0 to 684 months. In 20 patients the follow-up duration was less than one year, in 11 patients it was more than 20 years.

Fig. 4.

Time interval in years between diagnosis and last visit

At the latest visit, we identified 61 patients (37%) free of symptoms and clinical abnormalities. Thirteen of them did not take steroids or immunosuppression, but only 3 fulfilled the criteria of complete stable remission of the MGFA-PIS, with 7 patients being in remission for less than 1 year and 3 still taking a low dose of pyridostigmine. Of the 48 patients in remission under steroids or immunosuppression, 31 were in remission for more than 1 year and 17 for a shorter period. Of the 31 patients in remission for more than 1 year, 8 were still taking a low dose of pyridostigmine, leaving 23 patients in pharmacological remission according to the MGFA-PIS.

In addition, 21 patients (13%) had no symptoms of MG but showed limited abnormalities on clinical examination, mostly ptosis or diplopia on prolonged gaze fixation. Of these patients with minimal manifestations according to the MGFA-PIS, 20 belonged to MGFA class 1 and 1 to MGFA class 2a.

That means that at the latest visit 82 patients (50%) had no subjective complaints of their myasthenia.

Of the 81 patients with symptoms at the time of the latest visit, the majority were in MGFA class 1, 2a, 2b and 3a, with only 9 patients being in 3b, 4a and 4b (Fig. 3). Of these patients, 33 were retired and 12 of them described no limitations in daily living. 14 had mild limitations, leaving 7 retired patients with severe limitations. Of the patients at working age, 14 had fulltime jobs, and 9 part-time. 25 patients were on sick leave, with the MG as the main reason in 17 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Number of patients regarding their clinical status and work situation at the latest visit

| Clinical status and work situation | 82 (50%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No MG symptoms | ||||

| Normal examination | No steroids or IS | 13 (8%) | ||

| Steroids or IS | 48 (29%) | |||

| Minimal clinical abnormalities | 21 (13%) | |||

| MG symptoms present | 81 (50%) | |||

| Retired, no limitations | 12 (7%) | |||

| Retired, mild limitations | 14 (9%) | |||

| Retired, severe limitations | 7 (4%) | |||

| Fulltime at work | 14 (9%) | |||

| Parttime at work | 9 (6%) | |||

| Sick leave due to MG | 17 (10%) | |||

| Sick leave MG + other reason | 8 (5%) |

The endpoint of the study was the last consultation during the study period and there was no systematic follow-up afterwards. However, we know that 8 patients died after the study. Two cases involved complications of recurrent thymoma. The average age of the other 6 deaths was 78 years. None of the deaths could be directly related to the MG or its treatment.

Serological tests

Antibodies against AChR were documented in 135 patients (83%). They were present in 25/39 (64%) of the patients with only ocular symptoms at maximum disease severity and in 110/124 (89%) of patients with generalized disease. In the 27 patients with negative AChR antibody assay, anti-MuSK was tested in 14 and found positive in 6 (Table 2). All 6 have had bulbar symptoms during the course of the disease. Of the 8 patients that tested negative for both AChR and MuSK, 4 were purely ocular. None of the 13 AChR negative patients that were not tested for MuSK had bulbar symptoms and 10 of them were purely ocular. 14/21 (67%) of the seronegative patients for AChR antibody were purely ocular whereas only 25/141 (18%) of the seropositive patients were purely ocular. MuSK was tested negative in 12 patients positive for AChR. LRP4 was tested in 6 patients and was negative in all of them.

Table 2.

Summary of the serologic tests in patients with ocular and generalized Myasthenia Gravis

| Antibody status | All MG | Ocular | Generalized | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AChR + | 135 (83%) | 25/135 (19%) | 110/135 (81%) | ||

| AChR- | MuSK + | 6 (4%) | 0/6 (0%) | 6/6 (100%) | |

| MuSK- or not tested | 21 (13%) | 14/21 (67%) | 7/21 (33%) | ||

| AChR? | 1 |

EMG showed disturbed neuromuscular transmission in 11 of the 21 seronegative patients. In the remaining 10 patients the diagnosis was based on typical symptoms, exclusion of other pathology, and a sustained response to treatment with pyridostigmine or steroids. In a single patient with a typical myasthenia history of more than 6 decades and a thymectomy elsewhere in 1963, the result of the AChR antibody assay was not available.

Electrophysiology

Electrodiagnostic testing with repetitive nerve stimulation (RNS) was done in 89 patients. It was abnormal in 8 out of 20 patients with purely ocular symptoms at the time of diagnosis (40%). None of them was still purely ocular at maximum disease severity. It was abnormal in 46 of the 69 patients with generalized complaints (67%). SFEMG was done in 78 patients. It was abnormal in 30 out of 43 patients with purely ocular symptoms at the time of diagnosis (70%) and in 35 out of 36 patients with generalized complaints (97%). Of the 13 ocular patients with normal SFEMG, 11 were still ocular at maximum disease severity, while there was generalization in 9 out of 30 patients with abnormal SFEMG. SFEMG was done in the m. orbicularis oculi in 41 of the 43 ocular patients and in the m. frontalis in 2. In the generalized MG patients SFEMG was done in the facial muscles in 32 of the 36 patients and in the m. extensor digitorum communis in only 4. SFEMG was performed in 3 of the ocular patients with normal RNS and was found 3 times abnormal, and in 19 generalized patients with normal RNS where it was abnormal in 14 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Neurophysiologic studies in patients with ocular and generalized Myasthenia Gravis

| EMG examination | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RNS | SFEMG | ||||

| Number tested | Generalization | Number tested | Generalization | ||

| Ocular | Abnormal | 8 | 8 (100%) | 30 | 9 (30%) |

| Normal | 12 | 4 (33%) | 13 | 2 (15%) | |

| Generalized | Abnormal | 46 | 35 | ||

| Normal | 23 | 1 |

Thymectomy

Thymectomy was performed in 58 patients and 21 of them (13% of all MG patients) had a thymoma. Of the thymoma patients the World Health Organization (WHO) classification was type A in 2, type AB in 5, type B1 in 3, type B2 in 7, type B2/B3 in 2 and type B3 in 2. According to the Masaoka staging, 5 were grade I, 12 grade II, 2 grade III and 2 grade IV. In four patients there was recurrence of the thymoma after, respectively, 1 year (WHO B3, Masaoka IV), 3 years (AB, II), 12 years (B2, III) and 13 years (B1, III). In those four patients, the phrenic nerve had to be sacrificed unilaterally. From 2006 on, most thymectomies were robot-assisted, resulting in a significantly faster postoperative recovery.

The outcome at the latest visit was compared between the thymoma patients and the thymectomized patients without thymoma. More thymoma patients were in clinical remission (38 versus 19%) and less had a MGFA class 3 and 4 (10 versus 32%). However, only 2 of the 21 (10%) thymoma patients did not take steroids or immunosuppression, whereas in the non-thymoma group this number was higher (14/37 [38%]).

A similar pattern appears after comparison of the non-thymoma thymectomized patients with the generalized MG patients without thymectomy and onset before 60 years. Relatively more patients were free of symptoms and signs in the non-operated patients, but only 8/26 (31%) did not take steroids or immunosuppression in this group against the 38% in the thymectomy group.

Pharmacological treatments

The pharmacological therapies are shown in Table 4, with treatment at the latest visit in the left column and treatment along the course of the disease in the right.

Table 4.

Summary of treatments. IVIG: Intravenous immunoglobulins. IS: Immunosuppressive treatment. LV: latest visit

| Latest visit | LV ocular | LV generalized | Ever | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pyridostigmine | 91 (56%) | 15/39 | 76/124 | 158 (97%) |

| Steroids | 78 (48%) | 22/39 | 56/124 | 111 (68%) |

| Azathioprine | 51 (31%) | 9/39 | 42/124 | 77 (47%) |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 19 (12%) | 2/39 | 17/124 | 24 (15%) |

| Cyclosporin | 2 (1%) | 1/39 | 1/124 | 8 (5%) |

| Tacrolimus | 9 (6%) | 1/39 | 81/124 | 13 (8%) |

| Rituximab | 4 (2%) | |||

| IVIG | 1 | 1/124 | 7 (4%) | |

| Plasma exchange | 49 (30%) | |||

| Other | 1 | 1/124 | 2 (1%) | |

| Steroids or IS | 25/39 (64%) | 90/124 (73%) |

Most patients started a treatment with pyridostigmine, but a significant group could stop it later. Of the 5 patients who were never treated with pyridostigmine, 4 had a very benign course with remission of the symptoms at the time of diagnosis, and one had only ptosis with insufficient hindrance to provide treatment for it.

Nearly 2/3 of the patients (110 or 67%) received steroids during the course of their disease and almost half of them (78 or 48%) were still on steroids at the latest visit: 42 in monotherapy, 21 in combination with azathioprine alone and 2 more with azathioprine and tacrolimus, 5 in combination with mycophenolate mofetil alone, 2 in combination with tacrolimus alone and 6 with other combinations of immunosuppressive drugs. The median equivalent dose of methylprednisolone per day was 4 mg, although most patients took the steroids every other day. 27 patients were taking an equivalent daily dose of 8 mg or more, 11 of which had a daily dose of 16 mg or more. The highest dose was 32 mg/day in a patient with a recent relapse.

At the latest visit 51 patients were on azathioprine, of which 27 were on azathioprine alone. Of the 19 patients on mycophenolate mofetil, 9 were on monotherapy. The 9 patients on tacrolimus were also treated with steroids, azathioprine, or mycophenolate mofetil. Rituximab was very effective in 3 patients with MuSK myasthenia. A single AChR positive patient received rituximab as a treatment for rheumatoid arthritis, but it was not effective for her myasthenia.

The use of IV or SC immunoglobulins for myasthenia is not reimbursed by health insurance in Belgium, therefore we have very little experience with this treatment in our center. A single extremely severe patient with a history of 14 intensive care hospitalizations and who was treated with nocturnal non-invasive ventilation was on chronic therapy with IVIG. Six other patients had received IVIG for myasthenic crisis many years ago when it was available for compassionate use.

During the course of the disease, 49 patients underwent plasmapheresis, 42 of them around the maximum disease severity. Four more patients had plasmapheresis prior to surgery, two were treated elsewhere for mild symptoms and one was treated for concomitant Morvan syndrome. No patient was treated with chronic plasmapheresis. The two patients with “other” treatments participated in clinical trials for eculizumab and efgartigimod.

Adverse events

According to the medical files, 116 of the 158 patients (73%) who toke pyridostigmine reported side effects, the most common being increased intestinal activity and/or diarrhea in 33 patients followed by muscle cramps, fasciculations or myokymia in 22 with 11 more patients reporting both kinds of side effects. Side effects that were reported in 5 patients or less were stomach aches, salivation, eye tears, sweating, coughing fits and increase of bulbar MG symptoms. Most side effects were dose related but some patients described intolerance with doses as low as 3 X 10 mg/day. Fortunately, in most patients the side effects disappeared after some time with reasonable tolerance of a conventional dose of 3 to 6 × 60 mg/day.

In addition, many patients experienced side effects from steroid treatment. In the 112 patients who were ever treated with steroids, Cushing facies was noted in the file 36 times, often in combination with other problems like disturbed glucose tolerance, fragile skin, weight gain, glaucoma, cataract, and osteoporosis. Also 23 patients without clinical evidence of Cushing syndrome reported side effects like fragile skin in 6, myopathy with proximal weakness in 3, onset or deterioration of diabetes in 3, and further osteoporosis, stomach aches, weight gain, irritability, tendon lesions and long-lasting adrenal suppression. Clinical Cushing syndrome was seen with high doses and subsided after tapering. Osteoporosis prevention with calcium and vitamin D was started in all patients treated with steroids and further investigation and treatment were undertaken when there was clinical suspicion of osteoporosis. Thinning and fragility of the skin were probably underreported in the medical files and were often not responsive to dose reduction.

Azathioprine had to be discontinued in 19 patients due to adverse events: elevated liver enzymes in 5 patients, skin lesions in 4, leukopenia or anemia in 4, flu-like syndrome with fever and arthralgia in 3, hair loss in 1 and nonspecific intolerance in 2.

In general, mycophenolate mofetil and tacrolimus were well tolerated. Reported side effects of mycophenolate were diarrhea, headache, and nonspecific intolerance. Two patients discontinued tacrolimus due to tremor. Other side effects were stomach upset, palpitations, diarrhea and vomiting, stiff muscles and cramps, and nonspecific intolerance, each in 1 patient. Cyclosporine was stopped due to skin tumors, vomiting and muscle aches, and flu-like syndrome.

A frequent side effect of plasmapheresis was blood pressure fluctuation. Fortunately, only three patients experienced serious adverse events: one pneumothorax during catheter placement, one anaphylactic reaction to the replacement proteins and one thrombosis of the superior vena cava.

A possible side effect of thymectomy is damage to the phrenic nerve, especially when the nerve is surrounded by thymoma. It occurred in 4 patients in this series.

Discussion

With the arrival of new treatments for MG including inhibitors of the complement cascade and of the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRN), it is worth reflecting on the actual status of MG treatment to determine which patients would most likely benefit from the new treatments.

For that purpose, we reviewed the data of the MG patients who were seen at the neuromuscular reference center of the University Hospital of Antwerp during the years 2019, 2020 and 2021. We limited the study to the last 3 years to collect a population with a long-term follow-up. In fact, the median follow-up between diagnosis and last visit was nearly 6 years and only in 20 patients (12%) was the follow-up less than 1 year. A possible bias to more severe patients was the occurrence of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021 which caused some patients who felt well to postpone their consultation, but several of these patients were already seen in 2019.

The age and sex distribution of the patients are in accordance with reports of other centers worldwide [2]. In our series, there was still a slight preponderance of women. Recent series often show a preponderance of men, and in women a larger age peak after 60 than before 40 [8].

In accordance with other series, 71% of the patients started with ocular symptoms. At the time of diagnosis, 39% of the patients were still purely ocular, and at maximum disease severity 24%. The percentage of ocular MG differs largely between series [9]. We think that our number of 24% is rather low due to the selection of the patients in a tertiary neuromuscular center.

At maximum disease severity, 45 patients belonged to MGFA class 4 (severe weakness) and 7 to class 5 (intubation for artificial ventilation). Most of them responded to therapy as at last visit, only 7 patients belonged to class 4.

A particular problem in this study was the choice of the outcome parameter at the latest visit. Most recent papers prefer patient reported outcomes like activities of daily living (ADL) or health related quality of life, with MG-ADL being the primary outcome in several recent phase 2 and phase 3 trials [10−11]. Unfortunately, such data and variants like MG impairment index, single simple question and PASS (patient acceptable symptom state) question were not available for the majority of patients in this retrospective study based on hospital files [12−14]. The MGFA classification is not developed to measure study outcome [5]. The MGFA-PIS has some well characterized categories like complete stable remission, pharmacological remission, and minimal manifestations. In our study 37% of the patients had no symptoms of MG and no clinical abnormalities at the latest visit, but less than half of them fulfilled the criteria of complete stable remission or pharmacological remission as the duration of the remission was less than 1 year and as some patients were still taking a low dose of pyridostigmine, mainly for psychological reasons. Another 13% had no symptoms but minor clinical abnormalities, mostly ocular abnormalities on prolonged fixed gaze, meaning that half of the patients had no symptoms of MG anymore at the latest visit. These findings are in accordance with a recent study from the U.S. that reported 44% asymptomatic patients at latest visit [15].

In addition, half of the symptomatic patients had little or no functional impairment. To achieve this rather good outcome, the majority of patients (64% of the ocular patients and 73% of the generalized myasthenia) were taking steroids or immunosuppression at the latest visit. While prednisolone is the most commonly used steroid worldwide, methylprednisolone (MP) is more common in Belgium. Steroids are the most effective and the fastest-acting oral treatment, but their use is associated with numerous and major side effects [16]. In addition, there is a risk of a temporary worsening of the myasthenia, usually in the first or second week of treatment. Published reports indicate a risk up to more than 50% when using high doses [17]. In our experience, transient deterioration is rare with doses of 16 mg MP/day or lower.

In general, a dose of 5 mg of prednisolone or the equivalent of 4 mg of MP/day is considered a safe dose with acceptable side effects in the long term [16]. However, 37 of our patients needed a higher dose than 4 mg MP, despite 19 of them taking an additional immunosuppressive treatment. The patients with the high doses of 24 or 32 mg MP/day were unstable patients with recent diagnosis or recent relapse. The question when to stop these drugs is a difficult one. Relapses on decreasing the dose of the steroids are very common. Even some of our patients who were in long time remission with a dose of MP as low as 4 mg on alternating days had a relapse after further tapering or stopping.

In accordance with international recommendations, we consider azathioprine as a first choice when adding of immunosuppression to the steroids is needed, because it has been used for decades and the side effects are well known [18]. An important concern is the late appearance of the effect: onset at the earliest after 3 months and maximum effect after a year or more [19]. Other problems are the need for close monitoring of blood formula and liver enzymes [20] and a possible interaction with allopurinol. In the study period we did not measure the thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) activity or genetic status, as also patients without a TPMT mutation need close monitoring when giving azathioprine [21]. An additional point is an increased risk for skin tumors [22]. As a precaution, we recommend that patients on azathioprine avoid excessive exposure to sunlight and consult a dermatologist if in doubt about changing skin lesions. The decision to stop azathioprine in patients in remission under monotherapy is even more difficult than for stopping steroids, as the risk of relapse is more than 50% and a relapse does not occur until after several months, while it takes again several months before azathioprine has a clinical effect after restarting [19].

Mycophenolate mofetil is considered to be stronger and faster than azathioprine [19]. We use it sometimes instead of steroids to avoid deterioration of diabetes. But for mycophenolate maximum activity can also take more than 6 months. This is probably the reason why an international mycophenolate trial could not demonstrate the efficacy of the drug [23].

While mycophenolate is usually started with the same dose as for renal transplantation, tacrolimus is used in myasthenia in a low dose, usually 3 mg/day [19]. This dose causes remarkably few side effects. However, two of our patients had to stop the medication because of a marked increase in tremors. We prefer tacrolimus to cyclosporine because of the low dose needed and the lower nephrotoxicity.

Rituximab is considered to be very effective for MuSK myasthenia [24] and less effective in AChR MG [25].

Although IVIG is considered to be equivalent to plasmapheresis for the treatment of myasthenic crisis and it is less invasive for the patient, it is not reimbursed by the health insurance in Belgium and therefore it is only used very exceptionally.

Plasmapheresis is a very fast treatment but if it is not accompanied by steroids or immunosuppression, its effect does not last longer than 1–2 months. It is mainly used for myasthenic crisis and sometimes preoperatively or to avoid a transient deterioration after starting steroids. We believe that plasmapheresis is too invasive to be used as a chronic treatment [26].

A special feature of AChR MG is the relation with thymic hyperplasia and thymoma [27]. Adult AChR MG patients have a risk of 10 to 15% to have a thymoma, with a higher risk at older age [28]. A thymoma is an indication for thymectomy for oncological reasons. Thymic hyperplasia is much more common than thymoma in the early onset group but not seen in the late onset group, where the difference between early and late onset is not clear: in earlier studies 50 years old was often considered as the limit, but in the large international thymectomy trial patients up to 65 years old were included. That trial confirmed that thymectomy induced an improvement in non-thymoma patients with generalized AChR positive myasthenia gravis [29]. The effect of thymectomy in non-thymoma ocular MG, MuSK MG or seronegative MG is less well documented.

While it is generally accepted that MG linked to thymoma has a more severe course than non-thymoma MG [30], in our series the thymoma patients had a better outcome at latest visit than the non-thymoma thymectomized patients. This is probably due to the fact that nearly all thymoma patients were treated with steroids and/or immunosuppression.

In this limited series, non-thymoma thymectomized patients had no better outcome than early onset non-thymectomized generalized MG patients, except that a higher proportion did not take steroids or immunosuppression as of the latest visit. Probable confounding factors are selection bias with milder patients not opting for thymectomy, and the fact that patients in stable remission after thymectomy did not come to the hospital for follow-up especially during the Covid-19 pandemic. Our study does not give information about the efficacy of thymectomy.

As new treatments become available for MG, the decision about which therapy to use is becoming more difficult. This decision must be individualized for each patient, and in order to do so, it would be desirable to be able to predict the course of the disease. More specifically, it would be of great interest to predict which patients with only ocular symptoms at the time of diagnosis will remain ocular during the course of the disease. Unfortunately, no test can give a reliable prediction [9]. Generalization is more frequent in the AChR + group than in the seronegative group, and very few ocular patients with MuSK myasthenia are described [9]. In this limited series, generalization is common when repetitive nerve stimulations are abnormal, and rare when SFEMG in the facial muscles is normal.

While other studies suggest a sensitivity of SFEMG in the facial muscles for diagnosing ocular MG of 95% or more [31, 32], in a previous study we found a sensitivity of 80% [7]. In the present study even 30% of the MG patients limited to ocular symptoms had a normal SFEMG in the m.orbicularis oculi.

In conclusion, despite the limitations of a retrospective single-center study, our findings are remarkable by the very long follow-up of the patients. They confirm that most MG patients can be treated rather well with the presently available therapies: half of the patients are asymptomatic at the time of the latest visit and, of the symptomatic patients, half had little or no functional impairment, while only 4% of the patients were in MGFA class 4 with severe weakness.

To achieve this result, steroids and/or immunosuppression are necessary in the majority of patients. Although these therapies are very effective in MG, they are not specific for this disease, and they have many side effects and risks on the short and on the long-term, which sometimes limit their use.

New treatments can initially be targeted at the patients who do not respond adequately to the current ones. If their safety is also established in the long term and if their pricing allows it, they can possibly also be used more widely to avoid the side effects of steroids and current immunosuppressants.

Finally, it should be emphasized that the currently available complement and FcRN inhibitors are not specific for myasthenia and that a disease-specific immunological treatment still does not exist.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mr. John Wilkos for his language advice.

Data Availability

The data processed in this paper are all available.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was waived by the local Ethics Committee of the Antwerp University Hospital in view of the retrospective nature of the study and all the procedures being performed were part of the routine care.

Research involving human and animal participants

Rudy Mercelis received consultancy fees of Alexion and ArgenX and Alicia Alonso-Jiménez has participated in advisory boards for Alexion and UCB.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Verschuuren JJ, Palace J, Murai H, Tannemaat MR, Kaminski HJ, Bril V. Advances and ongoing research in the treatment of autoimmune neuromuscular junction disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21(2):189–202. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00463-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Punga AR, Maddison P, Heckmann JM, Guptill JT, Evoli A. Epidemiology, diagnostics, and biomarkers of autoimmune neuromuscular junction disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2022;21(2):176–188. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00297-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Westerberg E, Punga AR. Mortality rates and causes of death in Swedish Myasthenia Gravis patients. Neuromuscul Disord. 2020;30(10):815–824. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2020.08.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cortés-Vicente E, et al. Drug-refractory myasthenia gravis: Clinical characteristics, treatments, and outcome. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2022;9(2):122–131. doi: 10.1002/acn3.51492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaretzki A, et al. Myasthenia gravis: recommendations for clinical research standards. Neurology. 2000;55:16–23. doi: 10.1212/WNL.55.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vincent A, et al. Antibodies identified by cell-based assays in myasthenia gravis and associated diseases. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2012;1274:92–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mercelis R, Merckaert V. Diagnostic utility of stimulated single-fiber electromyography of the orbicularis oculi muscle in patients with suspected ocular myasthenia. Muscle Nerve. 2011;43(2):168–170. doi: 10.1002/mus.21853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanders DB, Raja SM, Guptill JT, Hobson-Webb LD, Juel VC, Massey JM. The Duke myasthenia gravis clinic registry: I. Description and demographics. Muscle Nerve. 2021;63(2):209–216. doi: 10.1002/mus.27120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Evoli A, Iorio R. Controversies in Ocular Myasthenia Gravis. Front Neurol. 2020 doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.605902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lehnerer S, et al. Burden of disease in myasthenia gravis: taking the patient’s perspective. J Neurol. 2021;269(6):3050. doi: 10.1007/s00415-021-10891-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muppidi S, Silvestri NJ, Tan R, Riggs K, Leighton T, Phillips GA. Utilization of <scp>MG-ADL</scp> in myasthenia gravis clinical research and care. Muscle Nerve. 2022 doi: 10.1002/mus.27476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barnett C, Bril V, Kapral M, Kulkarni AV, Davis AM. Myasthenia gravis impairment index. Neurology. 2017;89(23):2357–2364. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abraham A, Breiner A, Barnett C, Katzberg HD, Bril V. The utility of a single simple question in the evaluation of patients with myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve. 2017 doi: 10.1002/mus.25720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mendoza M, Tran C, Bril V, Katzberg HD, Barnett C. Patient-acceptable symptom states in myasthenia gravis. Neurology. 2020;95(12):e1617–e1628. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anil R, et al. Exploring outcomes and characteristics of myasthenia gravis: Rationale, aims and design of registry – The EXPLORE-MG registry. J Neurol Sci. 2020;414:116830. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2020.116830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Imai T, et al. Oral corticosteroid therapy and present disease status in myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve. 2014 doi: 10.1002/mus.24438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lotan I, Hellmann MA, Wilf-Yarkoni A, Steiner I. Exacerbation of myasthenia gravis following corticosteroid treatment: what is the evidence? A systematic review. J Neurol. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-10264-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sanders DB, et al. International consensus guidance for management of myasthenia gravis: Executive summary. Neurology. 2016;87(4):419–425. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gotterer Do L, Li Y. Maintenance immunosuppression in myasthenia gravis. J Neurol Sci. 2016;369:294–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2016.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jack KL, Koopman WJ, Hulley D, Nicolle MW. A Review of Azathioprine-Associated hepatotoxicity and myelosuppression in myasthenia gravis. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis. 2016;18(1):12–20. doi: 10.1097/CND.0000000000000133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lorenzoni PJ, Kay CSK, Zanlorenzi MF, Ducci RDP, Werneck LC, Scola RH. Myasthenia gravis and azathioprine treatment: Adverse events related to thiopurine S-methyl-transferase (TPMT) polymorphisms. J Neurol Sci. 2020;412:116734. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2020.116734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pedersen EG, et al. Risk of non-melanoma skin cancer in myasthenia patients treated with azathioprine. Eur J Neurol. 2014;21(3):454–458. doi: 10.1111/ene.12329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanders DB, et al. An international, phase III, randomized trial of mycophenolate mofetil in myasthenia gravis. Neurology. 2008;71(6):400–406. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000312374.95186.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hehir MK, et al. Rituximab as treatment for anti-MuSK myasthenia gravis. Neurology. 2017;89(10):1069–1077. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nowak RJ, et al. Phase 2 Trial of rituximab in acetylcholine receptor antibody-positive generalized myasthenia gravis: The BeatMG Study. Neurology. 2021 doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000013121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guptill JT, et al. A retrospective study of complications of therapeutic plasma exchange in myasthenia. Muscle Nerve. 2013;47(2):170–176. doi: 10.1002/mus.23508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jayam Trouth A, Dabi A, Solieman N, Kurukumbi M, Kalyanam J. Myasthenia gravis: a review. Autoimmun Dis. 2012;1(1):10. doi: 10.1155/2012/874680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marx A, et al. Thymoma related myasthenia gravis in humans and potential animal models. Exp Neurol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolfe GI, et al. Randomized trial of thymectomy in myasthenia gravis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(6):511–522. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maggi L, et al. Thymoma-associated myasthenia gravis: outcome, clinical and pathological correlations in 197 patients on a 20-year experience. J Neuroimmunol. 2008;201–202:237–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanders DB, Stålberg EV. AAEM minimonograph 25: Single-fiber electromyography. Muscle Nerve. 1996;19(9):1069–1083. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4598(199609)19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Padua L, Stalberg E, LoMonaco M, Evoli A, Batocchi A, Tonali P. SFEMG in ocular myasthenia gravis diagnosis. Clin Neurophysiol. 2000;111(7):1203–1207. doi: 10.1016/S1388-2457(00)00307-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data processed in this paper are all available.