Abstract

A 16-kbp DNA region that contains genes involved in the biosynthesis of the capsule of Mannheimia (Pasteurella) haemolytica A1 has been characterized. The gene cluster can be divided into three regions like those of the typical group II capsule biosynthetic clusters in gram-negative bacteria. Region 1 contains four genes (wzt, wzm, wzf, and wza) which code for an ATP-binding cassette transport apparatus for the secretion of the capsule materials across the membranes. The M. haemolytica A1 wzt and wzm genes were able to complement Escherichia coli kpsT and kpsM mutants, respectively. Further, the ATP binding activity of Wzt was demonstrated by its affinity for ATP-agarose, and the lipoprotein nature of Wza was supported by [3H]palmitate labeling. Region 2 contains six genes; four genes (orf1/2/3/4) code for unique functions for which no homologues have been identified to date. The remaining two genes (nmaA and nmaB) code for homologues of UDP–N-acetylglucosamine-2-epimerase and UDP–N-acetylmannosamine dehydrogenase, respectively. These two proteins are highly homologous to the E. coli WecB and WecC proteins (formerly known as RffE and RffD), which are involved in the biosynthesis of enterobacterial common antigen (ECA). Complementation of an E. coli rffE/D mutant with the M. haemolytica A1 nmaA/B genes resulted in the restoration of ECA biosynthesis. Region 3 contains two genes (wbrA and wbrB) which are suggested to be involved in the phospholipid modification of capsular materials.

Mannheimia (Pasteurella) haemolytica A1 is the principal microorganism responsible for bovine pneumonic pasteurellosis, a major cause of sickness and economic loss to the feed lot industry (15, 46). Some of its characterized virulence factors include a leukotoxin, a sialoglycoprotease, neuraminidase, and transferrin-binding proteins (9). In addition, the bacterium produces an extracellular capsular polysaccharide (CPS) which has been implicated to play a role in pathogenesis. The role of CPS in the virulence of a number of gram-negative pathogens has been well documented. Some of these activities include adherence (11), prevention of desiccation (30), and resistance to host immune defense (29).

For M. haemolytica A1, the activities of CPS in virulence and protection have not been well defined. It has been reported that CPS is important in the adherence of the bacterium to alveolar surfaces (6, 45) and inhibition of complement-mediated serum killing (7) as well as inhibition of the phagocytic and bactericidal activities of neutrophils (12, 43). Preliminary studies by Yates et al. (47) using crude CPS preparations of M. haemolytica A1 suggested that the capsule conferred some protection against experimental pasteurellosis; however, it was unclear which molecule(s) in the preparation was responsible for this protection. On the contrary, Conlon and Shewen (10) showed that purified M. haemolytica A1 CPS did not elicit protection against experimental challenge. It has been suggested by Gatewood et al. (19) that the antigenic nature of the CPS could be influenced by the culture conditions and that only CPS produced during growth in the host could stimulate a protective immune response.

The CPS of M. haemolytica A1 is composed of a disaccharide repeat of N-acetylmannosaminuronic acid (ManNAcA) β1,4 linked with N-acetylmannosamine (ManNAc) (2). ManNAcA is one of the sugar moieties in enterobacterial common antigen (ECA) (26). Other than this, little is known about the biosynthesis of CPS. As a first step in understanding the biosynthesis of the CPS and elucidating its role in pathogenesis and in immune protection, we report here the isolation and characterization of the genetic locus that contains the capsule biosynthetic genes of M. haemolytica A1.

Proposal of nomenclature scheme.

There are numerous reports in the literature that identified and named the various genes and proteins involved in CPS biosynthesis. For example, the genes that code for the ATP-binding transporter that have been named are kps in Escherichia coli (38), bex in Haemophilus influenzae (22), ctr in Neisseria meningitidis (17), cpx in Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae (44), and hex in Pasteurella multocida (8), to name a few. These cognate genes and proteins have been shown in most cases to be functionally interchangeable by complementation studies. These various gene designations create confusion in the literature, especially when researchers are examining homologous functions or the construction of hybrid genes and proteins. As more genetic loci involved in CPS biosynthesis are characterized, additional nomenclature will be introduced. During a consultation, P. Reeves suggested a uniform nomenclature for the genes in the CPS cluster that follows the scheme that has been established for the genes in bacterial polysaccharide biosynthesis (34). Using the M. haemolytica A1 CPS biosynthetic cluster as an example, it is proposed that the four genes in region 1 that code for the ATP-binding transporter be designated wza, wzf, wzm, and wzt in the order of their genetic organization, that the two genes in region 2 that code for homologues of the ManNAcA pathway be designated nmaA and nmaB, and that the two genes in region 3 that code for functions in phospholipid modification be designated wbrA and wbrB. The remaining four genes in region 2 with uncharacterized functions are designated orf1, orf2, orf3, and orf4 until their functions are determined. When the same gene from different organisms is being referred to, a suitable subscript will be added, e.g., wzaM.h. A summary of this proposed scheme, together with enzymatic functions of the encoded proteins and the names from other systems, is presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Proposed nomenclature for genes in the CPS biosynthetic cluster

| M. haemolytica gene | Gene(s) homologous to those in CPS cluster

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. influenzae | N. meningitidis | A. pleuropneumoniae | E. coli | P. multocida | Properties of the proteins | |

| wza | bexD | ctrA | cpxD | hexD | Lipoprotein | |

| wzf | bexC | ctrB | cpxC | kpsE | hexC | Periplasm-spanning protein |

| wzm | bexB | ctrC | cpxB | kpsM | hexB | Inner membrane protein |

| wzt | bexA | ctrD | cpxA | kpsT | hexA | ATPase |

| nmaA | rffE, wecB | ManNAc synthesis | ||||

| nmaB | rffD, wecC | ManNAcA synthesis | ||||

| wbrA | lipA | kpsC | phyA | Phospholipid substitution | ||

| wbrB | lipB | kpsS | phyB | Phospholipid substitution | ||

Only those genes whose products have characterised activities were assigned nomenclature. A blank space indicates that no similar genes or homologues were present.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

The E. coli strain XL1-Blue (Strategene, La Jolla, Calif.) was used for the cloning of all recombinant plasmids. E. coli strain CSR603 (41) was used for the maxi-cell labeling experiments. E. coli RS2436 (EV36 ΔkspT) and RS2604 (EV36 ΔkpsM) was obtained from R. Silver (University of Rochester, Rochester, N.Y.). E. coli 21566 (mutant rffD and rffE) was obtained from D. Bitter-Suermann (University of Hanover, Hanover, Germany). Plasmid pCW-1C (44), which encodes the cpx cluster of A. pleuropneumoniae, was provided by Thomas Inzana (Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, Va.). The M. haemolytica A1 λ library was obtained from George Weinstock (University of Texas, Houston, Tex.). The λ library was constructed by the use of EcoRI linkers ligated to randomly sheared DNA and packaged into the λZAP vector system (Stratagene). E. coli strains were cultured in Luria-Bertani broth supplemented with thymine (50 μg/ml) and with ampicillin (100 μg/ml) when required. M. haemolytica A1 was cultured in brain heart infusion broth. All cultures were grown at 37°C unless stated otherwise.

Enzymes, chemicals, and antibodies.

Restriction endonucleases, T4 DNA ligase, and protein and DNA molecular weight standards were purchased from Pharmacia Chemicals (Baie d'Urfe, Quebec, Canada), GIBCO/Bethesda Research Laboratories (Burlington, Ontario, Canada), or Bio-Rad Laboratories (Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) and used according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Screening of λ library and characterization of cloned DNA.

The λ library was plated out on E. coli XL1-Blue cells to produce approximately 300 plaques per plate. Plaques were lifted from the agar plates, and the phage DNA was prepared for hybridization as described by the supplier. A 1.5-kbp HindIII DNA fragment from pCW-1C was isolated, radiolabeled with [α-32P]dATP (ICN Pharmaceuticals, Montreal, Quebec, Canada) by using a random primer labeling kit (Boehringer Mannheim, Laval, Quebec, Canada), and used to hybridize against the λ library at high stringency (42°C, 50% formamide). Positively hybridizing plaques were recovered and screened a second time, and the plasmid was excised from the phagemid according to the manufacturer's instructions (Stratagene). Plasmid DNA was isolated from E. coli cells using Qiagen columns (Chatsworth, Calif.). Standard techniques were used for restriction analysis, subcloning, ligation, and recovery of DNA fragments (40).

Overlapping clones were isolated from the λ library by chromosome walking using internal fragments from the recombinant plasmid as probes. Briefly, an appropriate fragment was recovered from the plasmid after digestion and recovery from a low-melting-point agarose gel. The DNA was extracted from the gel by Gene-Clean (Bio101, La Jolla, Calif.), labeled with [α-32P]dATP (ICN Pharmaceuticals), and used to hybridize against the λ library as described above. Plasmids from positively hybridizing plaques were recovered and mapped, and those that contained DNA beyond the previously cloned regions were chosen for further studies.

Alternatively, overlapping DNA was identified by restriction mapping of the genomic DNA by Southern hybridization using an appropriate fragment from the cloned DNA. Briefly, the DNA fragment was labeled with digoxigenin and hybridized against total genomic DNA digests according to the protocol from the supplier (Boehringer Mannheim). A suitable DNA fragment was recovered from an agarose gel and cloned into plasmid pBlueScript SKII(+) (Stratagene). DNA from recombinant plasmids were sequenced to identify overlapping DNA and into newly cloned regions.

The nucleotide sequence of the cloned DNA was determined by the dideoxy sequencing method according to our laboratory procedure (24) by using a combination of manual and automated sequencing approaches. Automated sequencing was performed at the Laboratory Services Division at the University of Guelph by using a 377 Prism automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.).

Nucleotide sequence and homology analyses.

The nucleotide sequences were analyzed using the software programs Gene Runner (Hastings Software, New York, N.Y.) and PC/Gene (IntelliGenetics, Mountain View, Calif.). Nucleotide and amino acid sequence homology comparisons were carried out with GenBank DNA and protein sequence databases using the National Center for Biotechnology Information BLAST network server (3). The sequences were also examined using the ψ-BLAST analysis (3).

Maxi-cell labeling of plasmid-encoded proteins.

The proteins expressed from recombinant plasmids were radiolabeled in an E. coli maxi-cell system according to our laboratory procedure (1, 41). Briefly, E. coli CSR603/pPHCPX2.2 (or pPHCPX10.1) cells were subcultured from a saturated culture into fresh Davis minimal medium supplemented with 0.5% Casamino Acids and ampicillin. After 2 h of growth, 10 ml of the culture was irradiated with an UV lamp at 400 μW/cm2 on a petri plate. After growth for another 2 h, 100 μl of d-cycloserine (2 mg/ml) was added and the culture was grown overnight. A 3-ml aliquot was centrifuged and washed, and the cells were resuspended in 0.5 ml of Davis minimal medium supplemented with threonine and proline at 100 μg/ml and arginine and leucine at 150 μg/ml. The cell suspension was grown for 1 h at 37°C, after which 25 μCi of Trans35S-label (ICN Pharmaceuticals) or 50 μCi of [3H]palmitate (New England Nuclear, Guelph, Ontario, Canada) was added. After labeling for 2 h, the cells were recovered and washed once with the supplemented Davis medium. The [3H]palmitate-labeled sample was washed twice with methanol, air dried, and resuspended in 100 μl of 2× sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) sample buffer. A 20- to 30-μl aliquot was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. The 35S-labeled sample was used for the ATP-agarose binding experiment (see below).

Functional analysis of open reading frames (ORFs). (i) Complementation of E. coli kpsT or kpsM

E. coli strains RS2436ΔkpsT and RS2604ΔkpsM, which were defective in the biosynthesis of the K1 CPS, were complemented with pPHCPX2.2. Briefly, the E. coli strains were transformed with pPHCPX2.2 or the pBluescript vector and selected by ampicillin resistance. E. coli RS2604 cells were grown at 25°C to avoid selecting for secondary mutations. The transformants were examined for phage sensitivity to the K1 capsule specific phages E and K1F (33) by spotting a serial dilution of the phages on a lawn of the E. coli cells and grown at 37°C overnight.

(ii) Binding of Wzt to ATP.

The affinity of Wzt to ATP was demonstrated by the binding of Wzt to ATP-agarose. Briefly, ATP affinity matrix (Sigma, Oakville, Ontario, Canada) was swollen in 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 7.2)–0.1% Triton X-100 at 4°C overnight and washed extensively with the same buffer. E. coli CSR603/pPHCPX2.2 cells containing the 35S-labeled proteins were suspended in the same buffer and sonicated at 100 W four times at 15 s each. After centrifugation at 3,000 × g to remove whole cells and debris, the supernatant was applied to the ATP-agarose affinity column. The column was washed with 10 volumes of the same buffer, after which the bound proteins were eluted with 0.125 mM ATP in the same buffer. The eluant was collected, and an aliquot was examined by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography from the dried gel.

(iii) Complementation of E. coli rffD and rffE defective in ECA biosynthesis.

A 3.9-kbp fragment that contains only the complete nmaA and nmaB genes was amplified by PCR using primers based on the flanking sequences. The restriction sites KpnI and XbaI were introduced at the ends of the fragment to facilitate its cloning into pBluescript SK. The resulting plasmid pNMA was transformed into E. coli 21566 (mutant rffD and rffE) cells, and ECA was prepared from the transformants according to the method of Rick et al. (36). The ECA preparations were electrophoresed in SDS–12% PAGE, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and immunostained with monoclonal antibody (MAb) 898 as previously described (32). A second antibody detection was carried out using rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin G alkaline phosphatase conjugate (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc., West Grove, Pa.) according to our laboratory procedures (25). Afterwards, the blot was developed colorimetrically with nitroblue tetrazolium and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate (BCIP) as described previously.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in GenBank under the accession no. AF170495.

RESULTS

Isolation and characterization of pPHCPX2.2.

Using the 1.5-kbp HindIII fragment from the A. pleuropneumoniae cpx cluster as a probe, positively hybridizing plaques were isolated from the λ library and rescreened, and the plasmid was excised for further analysis. A plasmid designated pPHCPX2.2 (Fig. 1) that was recovered from one of the clones was shown to contain approximately 6 kbp of insert DNA that hybridized to the probe. Nucleotide sequence analysis showed that this DNA contains ORFs that are highly homologous to the ATP-binding cassette 2 subfamily transporters (20, 35). These transporters are involved in polysaccharide export across the inner and outer membranes in a number of gram-negative bacteria (see below).

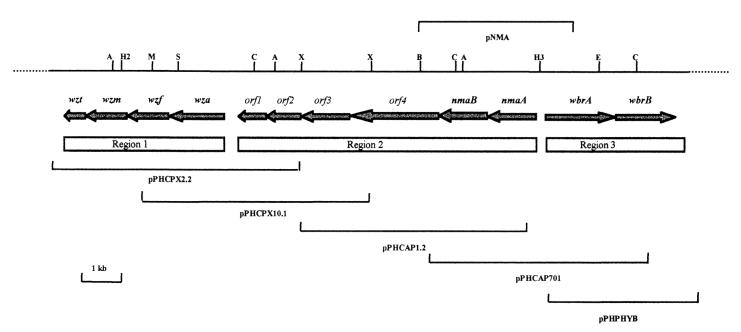

FIG. 1.

Genetic organization of M. haemolytica A1 CPS cluster. The DNA cluster is divided into three regions with 12 total ORFs, shown with their direction of expression. The four λ clones (pPHCPX2.2, pPHCPX10.1, pPHCAP1.2, and pPHCAP7010) and the plasmid clone (pPHPHYB) containing the overlapping DNA are as indicated. The position of the 3.9-kbp fragment cloned in pNMA is indicated. Enzyme abbreviations are as follows: A, AvaI; B, BamHI; C, ClaI; E, EcoRV; H2, HincII; M, MluI; S, StyI; X, XbaI; and H3, HindIII.

Isolation of overlapping clones containing the remaining capsule biosynthetic cluster.

Using the approach of chromosome walking, three additional λ clones were isolated, each containing insert DNA overlapping to the right of the cloned DNA in pPHCPX2.2 (Fig. 1). A fifth plasmid clone (pPHPHYB) that contains DNA further to the right of the cluster was also isolated by direct cloning of the DNA flanking pPHCAP701. Together, these five clones contained a total of 16 kbp of DNA that was analyzed.

It was immediately apparent from the analysis of the sequence data and assignment of ORFs that the M. haemolytica A1 CPS cluster has the same genetic organization as other well-characterized group II capsule biosynthetic clusters (5, 21, 37). The cluster was divided into three regions, and the proteins encoded in each region are examined in the following sections. The DNA that flanked the CPS cluster does not contain information that is involved directly in the biosynthesis of the capsule. However, they may code for regulatory functions, as in the case of the N. meningitidis CPS cluster.

Analysis of proteins in region 1.

Examination of the nucleotide sequence in region 1 identified four ORFs in tandem on the same DNA strand. These ORFs were designated wza, wzf, wzm, and wzt (Fig. 1) by following the proposal presented here (Table 1). Each of the encoded polypeptides showed high amino acid homology with the cognate Cpx proteins in A. pleuropneumoniae (44), the Bex proteins of H. influenzae (22), the Ctr proteins of N. meningitidis (17), and the Kps proteins of E. coli K5 (38). The E. coli K5 CPS cluster does not contain a Wza homologue, but a Wza homologue from E. coli 09a:K30 was included for comparison (13). Additional homology was also observed with ATP transport proteins from other bacterial systems, but for simplicity, only the A. pleuropneumoniae Cpx, the H. influenzae Bex, the N. meningitidis Ctr, and the E. coli K5 proteins were included in this comparison (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Comparison of the proteins encoded by the ORFs in the M. haemolytica A1 CPS cluster with proteins in several other CPS clusters

| M. haemolytica protein | Similar protein (source) | Accession no. | % Identity | % Similarity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wzt | CpxA (A. pleuropneumoniae) | U36397 | 81.9 | 93.9 |

| BexA (H. influenzae) | P10604 | 81.4 | 91.6 | |

| CtrD (N. meningitidis) | P32016 | 76.9 | 90.6 | |

| KpsT (E. coli K5) | P24586 | 45.6 | 68.4 | |

| Wzm | CpxB (A. pleuropneumoniae) | U36397 | 81.4 | 91.6 |

| BexB (H. influenzae) | P19391 | 74.3 | 86.5 | |

| CtrC (N. meningitidis) | P32015 | 67.2 | 82.2 | |

| KpsM (E. coli K5) | P24584 | 29.9 | 48.2 | |

| Wzf | CpxC (A. pleuropneumoniae) | U36397 | 63.0 | 77.4 |

| BexC (H. influenzae) | P22930 | 70.8 | 80.6 | |

| CtrB (N. meningitidis) | P32014 | 49.9 | 68.4 | |

| KpsE (E. coli K5) | P42214 | 26.3 | 48.9 | |

| Wza | CpxD (A. pleuropneumoniae) | U36397 | 79.7 | 90.7 |

| BexD (H. influenzae) | P22236 | 74.5 | 87.2 | |

| CtrA (N. meningitidis) | P32758 | 51.6 | 73.8 | |

| Wza (E. coli 09:K30) | AF104912.1 | 28.9 | 45.7 | |

| NmaA | WecB (E. coli K12) | 2367283 | 56.7 | 72.7 |

| NmaB | WecC (E. coli K12) | P27829 | 62.5 | 75.4 |

| WbrA | LipA (N. meningitidis) | Q05013 | 63.3 | 69.3 |

| PhyA (P. multocida) | AF067175 | 52.5 | 69.3 | |

| KpsC (E. coli K5) | P42217 | 50.9 | 63.9 | |

| WbrB | LipB (N. meningitidis) | Q05014 | 50.6 | 64.2 |

| PhyB (P. multocida) | AF067175 | 55.5 | 69.3 | |

| KpsS (E. coli K5) | P42218 | 35.7 | 55.3 |

Analysis of proteins in region 2.

Six ORFs were identified in region 2. Of the six, four showed no significant homology with sequences in the data banks by BLAST or ψ-BLAST searches. The remaining two ORFs showed significant homologies to the E. coli wecB and wecC genes and were named nmaA and nmaB, respectively. The E. coli wecB and wecC genes (formerly named rffE and rffD, respectively) are involved in the biosynthesis of ECA (28). wecB codes for UDP–N-acetylglucosamine-2-epimerase, which catalyzes the conversion of UDP–N-acetylglucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) to UDP-ManNAc. wecC codes for UDP-ManNAc dehydrogenase, which oxidizes UDP-ManNAc to UDP-ManNAcA. ManNAcA is one of the three sugars in ECA, whereas both ManNAc and ManNAcA are components of the M. haemolytica A1 CPS. A homology comparison of the corresponding proteins is shown in Table 2.

Analysis of the proteins in region 3.

Two ORFs were identified in region 3. The first ORF is homologous to kpsC, lipA, and phyA of the E. coli K5 (38), N. meningitidis (18), and P. multocida (8) CPS clusters, respectively, and was designated wbrA. The next ORF is homologous to kpsS, lipB, and phyB from the same CPS clusters and was designated wbrB. In N. meningitidis, the two proteins LipA and LipB have been shown to be responsible for substitution of phospholipids on the CPS at the reducing ends of the polysaccharide chains (18). This lipid modification is necessary for the translocation of the CPS to the cell surface and the anchoring of CPS to the outer membrane (18). Therefore, it is likely that the two homologous M. haemolytica A1 proteins perform the same functions during CPS biosynthesis.

Functional analysis of M. haemolytica A1 Wz* proteins.

To demonstrate the function of the Wz* transport proteins, the plasmid pPHCPX2.2 was transformed into E. coli kpsM or kpsT mutants which are defective in the synthesis of the K1 capsule. In E. coli K1, KpsM and KpsT have been hypothesized to form an inner membrane complex for the transport of CPS (31, 33). Based on the homology comparison, we predicted that Wzm is a functional homologue of KpsM and that Wzt is a functional homologue of KpsT. After transformation of the E. coli mutants, the colonies were examined for phage sensitivity to phages E and K1F. The results showed that the E. coli mutants were complemented by pPHCPX2.2 and phage sensitivity was restored. Even though the complementation studies were not carried out with subclones which carry only wzm or wzt separately, the extensive similarities between the proteins as well as similar complementation data from other systems are consistent with the interpretation that the M. haemolytica Wzm and Wzt proteins are functional homologues to E. coli KpsM and KpsT, respectively. Minimally, these data showed that the M. haemolytica A1 transporter is capable of translocating the E. coli K1 capsular materials across the membranes.

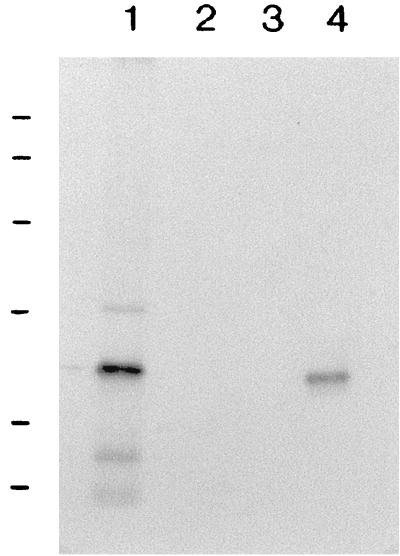

The analysis of Wzt showed that it contains the typical ATP-binding domains (42) which are also present in the homologous BexA, CtrD, and KpsT proteins. The results in Fig. 2 show a 35S-labeled protein with a molecular mass of approximately 24 kDa which bound to the ATP affinity matrix and eluted with ATP. The molecular mass of this protein was as expected for Wzt expressed from the plasmid pPHCPX2.2. This binding assay demonstrated that the Wzt protein exhibits ATP binding activity as predicted.

FIG. 2.

An autoradiogram of an SDS-PAGE gel showing the elution of 35S-labeled Wzt from an ATP-agarose affinity column. Wzt expressed from pPHCPX2.2 was labeled with 35S in the E. coli maxi-vell system, and the sonicated cell extract was applied to the column, washed extensively, and eluted with 0.125 mM ATP. Lane 1, material applied to the column; lanes 2 and 3, products of the first and second washes, respectively; lane 4, final elution with 0.125 mM ATP showing a 24-kDa labeled band, the expected molecular mass of Wzt. Molecular mass markers (97.4, 66.2, 45, 31, 21.5, and 14.4 kDa [from top to bottom]) are indicated on the left.

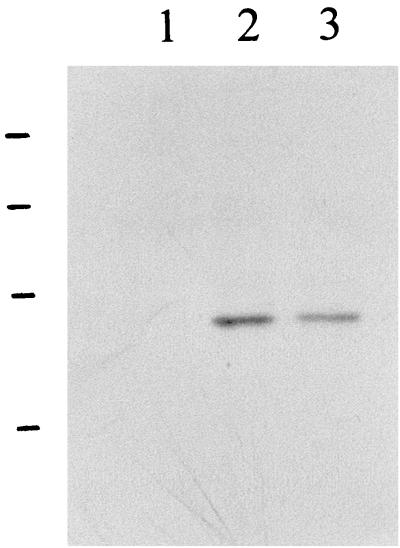

The analysis of Wza suggested that it is a lipoprotein homologous to BexD and CtrA. Wza contains the typical lipoprotein leader as well as the signal peptidase II cleavage site. To demonstrate that Wza is a lipoprotein, plasmid-encoded proteins expressed from pPHCPX2.2 were labeled with [3H]palmitic acid in the E. coli maxi-cell system. The results in Fig. 3 show that a 43-kDa protein corresponding to the predicted molecular mass of Wza was labeled with [3H]palmitic acid, supporting the prediction that Wza is a lipoprotein.

FIG. 3.

An autoradiogram of an SDS-PAGE gel showing [3H]palmitate labeling of Wza. Wza expressed from the recombinant plasmids was labeled in the E. coli maxi-cell system with [3H]palmitate and separated by SDS-PAGE. Lane 1, pBluescript SK; lane 2, pPHCPX2.2; lane 3, pPHCPX10.1 showing the 42-kDa Wza. Molecular mass standards (97.4, 66.2, 45, and 31 kDa [from top to bottom]) are indicated on the left.

Complementaion of ECA biosynthesis.

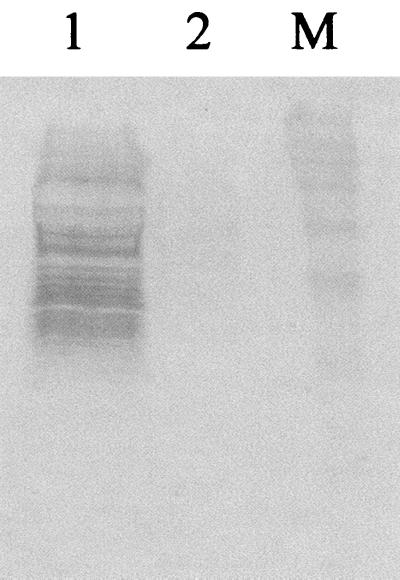

Based on the above analysis, region 2 of the M. haemolytica A1 CPS cluster contains two genes which are involved in the biosynthesis of UDP-ManNAc and UDP-ManNAcA. To demonstrate the activities of these two gene products, they were tested for functional complementation of the E. coli wecB/C genes. When the plasmid pNMA was transformed into E. coli 21566 (mutant wecB and wecC), it was observed that ECA biosynthesis was restored (Fig. 4). This showed the activities of the M. haemolytica A1 nmaA and nmaB genes and demonstrated that the biosynthesis of the amino sugars for incorporation into CPS in M. haemolytica A1 utilized a pathway similar to that of the production of UDP-ManNAc and UDP-ManNAcA from UDP-GlcNAc in ECA biosynthesis.

FIG. 4.

Restoration of ECA production in E. coli 21566 (mutant wecB and wecC) by the M. haemolytica A1 nmaA and nmaB genes. ECA was prepared from the E. coli strains, separated by SDS-PAGE, Western blotted, and immunostained with MAb 898. Lane 1, E. coli 21566 carrying pNMA; lane 2, E. coli 21566 carrying pBluescript SK; lane M, molecular mass standards (98, 64, 50, 36, 30, 16, and 6.4 kDa [from top to bottom]).

DISCUSSION

The results here show that the genetic organization of the M. haemolytica A1 CPS biosynthetic cluster is the same as that reported for group II capsules. This is consistent with the hypothesis regarding the evolution of the CPS biosynthetic clusters in gram-negative bacteria (16, 39). The moles percent of G+C of the DNA in regions 1, 2, and 3 are 36.2, 35.7, and 36.8, respectively, which are very similar to the overall 39 mol% G+C of M. haemolytica A1 DNA (23). This indicates that these DNAs were probably not recently acquired by the bacterium. However, on closer analysis, the four uncharacterized ORFs in region 2 have a moles percent G+C of only 33.3. Since no significant homologies with these sequences were detected in the data banks, this region may be entirely unique to M. haemolytica A1 and might have been acquired elsewhere from an unidentified source.

Examination of the nucleotide sequences of the wz* genes showed that they are located on the same DNA strand, with 70 nucleotides between wza and wzf and fewer than 2 nucleotides between wzf and wzm and between wzm and wzt, as in the case of the cognate genes in A. pleuropneumoniae (44). This similar organization with related CPS clusters is consistent with analysis that suggests that one promoter upstream of wza regulates the expression of the wz* genes in region 1. There is an alternative possibility that a second promoter may be present upstream of wzf; experiments are in progress to address this issue. Separate promoters (in opposite orientations) between nmaA and wbrA could be involved in the regulation of expression of the genes in regions 2 and 3. The complementation of ECA biosynthesis using the insert DNA in pNMA suggested that a promoter located upstream of nmaA is responsible for its expression. In E. coli K5, three promoters have been identified for the expression of the genes in region 2 (37), whereas a separate promoter is responsible for the expression of kpsT and kpsM in region 3 (31). For P. multocida, it has been suggested that one promoter is responsible for the expression of the genes in regions 1 and 2 together, whereas a different promoter regulates the genes in region 3 (8). Transcriptional analysis will be performed on the M. haemolytica A1 CPS cluster to examine the expression of these genes and regulatory mechanisms involved in CPS biosynthesis.

The complementation of the E. coli K1 kpsT and kpsM mutants with M. haemolytica A1 wzt and wzm showed that the export of CPS through the inner membrane follows a similar mechanism as in the export of polysialic acid in E. coli K1. Analysis of the amino acid sequences showed that the KpsM and KpsT proteins from the K1 and K5 clusters are essentially identical. Further, the cpx genes from A. pleuropneumoniae have been shown to complement the E. coli K5 kps mutants (44), and we chose to complement the E. coli K1 mutants instead. According to the model proposed by Bliss and Silver (4), the KpsM and KpsT proteins are responsible for interaction with the polysaccharide chain to initiate the insertion of the complex into the inner membrane for export. To complete the export process, KpsE has been postulated to be involved in creating localized fusions of the inner and outer membranes and KpsD likely functions in the recruitment of a porin to facilitate export of the polysaccharide out of the cell. It would be of interest to examine the complementation of the remaining wz* genes with the corresponding E. coli mutants to determine if the components in subsequent steps of export are interchangeable. Recently, it has been shown that in E. coli 09a:K30 cells, Wza forms ring-shaped multimeric complexes which may be involved in the translocation of CPS materials across the membranes (13).

One interesting observation from this work is the restoration of ECA biosynthesis in an E. coli wecB/C mutant by the M. haemolytica A1 nmaA/B genes. The E. coli mutant 21566 was generated by Tn10 mutagenesis and was originally thought to have a transposon insertion in rffD (wecC). However, it was shown by Marolda and Valvano (27) that in addition to a transposon insertion in rffD, 21566 also contains a small insertion in the upstream rffE gene, resulting in the loss of both epimerase and dehydrogenase activities. Therefore, the complementation experiment carried out with both nma genes showed that the two M. haemolytica A1 enzymes can complement both missing activities. The biosynthesis of ECA takes place at the inner membrane and involves a stepwise transfer of the amino sugars to the lipid carrier undecaprenyl monophosphate. The complementation results showed that the enzymes involved in the biosynthesis of UDP-ManNAcA from UDP-ManNac and UDP-GlcNAc in E. coli and M. haemolytica A1 cells are functional homologues. This also shows that the pathways for the synthesis of the amino sugars for incorporation into CPS or ECA are essentially the same.

The four ORFs in region 2 of the CPS showed no significant homologies with any of the sequences in the data banks. This region usually encodes functions involved in the biosynthesis of sugar moieties or glycosyl-transferase enzymes (37). Presently, there is no indication of the function(s) of these proteins and whether they are involved in capsule biosynthesis. Further characterization by mutagenesis experiments may help to elucidate their activities.

With the present data in hand, experiments are being done to examine the role of CPS in pathogenesis. DNA flanking the CPS cluster is being characterized to determine if any regulatory functions are encoded there, as in the CPS locus of N. meningitidis. In addition, using the gene replacement procedure described by Federova and Highlander (14), an acapsular mutant in which the nmaA and nmaB genes have been knocked out has been created (unpublished results). The properties of this acapsular mutant are being examined.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported by a research grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

We thank T. Inzana, G. Weinstock, R. Silver, and D. Bitter-Suermann for their supply of plasmids, E. coli strains, capsule-specific phages, and MAb. We thank P. Reeves for the proposed nomenclature for the CPS biosynthetic genes. We also thank C. Whitfield for valuable suggestions in the writing of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdullah K M, Lo R Y C, Mellors A. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and expression of the Pasteurella haemolytica A1 glycoprotease gene. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5597–5603. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.18.5597-5603.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adlam C, Knights J M, Mugridge A, Lindon J C, Baker P R W, Beesley J E, Spacey B, Craig G R, Nagy L K. Purification, characterization and immunological properties of the serotype-specific capsular polysaccharide of Pasteurella haemolytica (serotype A1) organisms. J Gen Microbiol. 1984;130:2415–2426. doi: 10.1099/00221287-130-9-2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altshul S F, Madden T L, Shäffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bliss J M, Silver R P. Coating the surface: a model for expression of capsular polysialic acid in Escherichia coli K1. Mol Microbiol. 1996;21:221–231. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.6461357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boulnois G J, Roberts I S. Genetics of capsular polysaccharide production in bacteria. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1990;150:1–18. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-74694-9_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brogden K A, Adlam C, Lehmkuhl H D, Cutlip R C, Knights J M, Engen R L. Effect of Pasteurella haemolytica (A1) capsular polysaccharide on sheep lung in vivo and on pulmonary surfactant in vitro. Am J Vet Res. 1989;50:555–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chae C H, Gentry M J, Confer A W, Anderson G A. Resistance to host immune defense mechanisms afforded by capsular material of Pasteurella haemolytica, serotype 1. Vet Microbiol. 1990;25:241–251. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(90)90081-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chung J Y, Zhang Y, Adler B. The capsule biosynthetic locus of Pasteurella multocida A:1. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;166:289–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Confer A W, Clinkenbeard K D, Murphy G L. Pathogenesis and virulence of Pasteurella haemolytica in cattle: an analysis of current knowledge and future approaches. In: Donachie W, Lainson F A, Hodgson J C, editors. Haemophilus, Actinobacillus, and Pasteurella. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1995. pp. 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conlon J A R, Shewen P E. Clinical and serological evaluation of a Pasteurella haemolytica A1 capsular polysaccharide vaccine. Vaccine. 1993;11:767–771. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(93)90263-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costerton J W, Cheng K-J, Geesey G G, Ladd T I, Nickel J C, Dasgupta M, Marrie T J. Bacterial biofilm in nature and disease. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1987;41:435–464. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.41.100187.002251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Czuprynski C J, Noel E J, Adlam C. Modulation of bovine neutrophil antibacterial activities by Pasteurella haemolytica A1 purified capsular polysaccharide. Microb Pathog. 1989;6:133–141. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(89)90016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drummelsmith J, Whitfield C. Translocation of group 1 capsular polysaccharide to the surface of Escherichia coli requires a multimeric complex in the outer membrane. EMBO J. 2000;19:57–66. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.1.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Federova N D, Highlander S K. Generation of targeted nonpolar gene insertions and operon fusions in Pasteurella haemolytica and creation of a strain that produces and secretes inactive leukotoxin. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2593–2598. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.7.2593-2598.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frank G H. Pasteurellosis of cattle. In: Adlam C, Rutter J M, editors. Pasteurella and pasteurellosis. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press; 1989. pp. 197–222. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frosch M, Edwards U, Bousset K, Krausse B, Weisgerber C. Evidence for a common molecular origin of capsular gene loci in Gram-negative bacteria expressing group II capsule polysaccharides. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1251–1263. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frosch M, Weisgerber C, Meyer T F. Molecular characterization and expression in Escherichia coli of the gene complex encoding the polysaccharide capsule of Neisseria meningitidis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:1669–1673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.5.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frosch M, Muller A. Phospholipid substitution of capsular polysaccharides and mechanisms of capsule formation in Neisseria meningitidis. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:483–493. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gatewood D M, Fenwick B W, Chengappa M M. Growth-condition dependent expression of Pasteurella haemolytica A1 outer membrane proteins, capsule, and leukotoxin. Vet Microbiol. 1994;41:221–233. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(94)90103-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins C F, Hiles I D, Salmond G P, Gill D R, Downie J A, Evans I J, Holland I B, Gray L, Buckel S D, Bell A W, Hermodson M A. A family of related ATP-binding subunits coupled to many distinct biological processes in bacteria. Nature. 1986;323:448–450. doi: 10.1038/323448a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jann B, Jann K. Structure and biosynthesis of the capsular antigens of Escherichia coli. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1990;150:19–42. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-74694-9_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kroll J S, Loynds B, Brophy L N, Moxon E R. The bex locus in encapsulated Haemophilus influenzae: a chromosomal region involved in capsular polysaccharide export. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1853–1862. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb02034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lo R Y C. An analysis of the codon usage of Pasteurella haemolytica A1. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;100:125–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1992.tb14030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lo R Y C, Strathdee C A, Shewen P E. Nucleotide sequence of the leukotoxin genes of Pasteurella haemolytica A1. Infect Immun. 1987;55:1987–1996. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.9.1987-1996.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lo R Y C, Mellors A. The isolation of recombinant plasmids expressing secreted antigens of Pasteurella haemolytica A1 and the characterization of an immunogenic 60 kDa antigen. Vet Microbiol. 1996;51:381–391. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(96)00052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lugowski C, Romanowske E, Kenne J, Lindberg B. Identification of a trisaccharide repeating-unit in the enterobacterial common-antigen. Carbohydr Res. 1983;118:173–181. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marolda C L, Valvano M A. Genetic analysis of the dTDP-rhamnose biosynthesis region of the Escherichia coli VW187(07:K1) gene cluster: identification of functional homologs of rfbB and rffA in the rff cluster and correct location of the rffE gene. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:5539–5546. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.19.5539-5546.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meier-Dieter U, Starman R, Barr K, Mayer H, Rick P D. Biosynthesis of enterobacterial common antigen in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:13490–13497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moxon E R, Kroll J S. The role of bacterial polysaccharide capsules as virulence factors. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1990;150:65–85. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-74694-9_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ophir T, Gutnick D. A role for exopolysaccharides in the protection of microorganisms from desiccation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:740–745. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.2.740-745.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pavelka M S, Wright L F, Silver R P. Identification of two genes, kpsM and kpsT, in region 3 of the polysialic gene cluster of Escherichia coli K1. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4603–4610. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.15.4603-4610.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peters H, Jürs M, Jann B, Jann K, Timmis K N, Bitter-Suermann D. Monoclonal antibodies to enterobacterial common antigen and to Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide outer core: demonstration of antigenic determinant shared by enterobacterial common antigen and E. coli K5 capsular polysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1985;50:459–466. doi: 10.1128/iai.50.2.459-466.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pigeon R P, Silver R P. Topological and mutational analysis of KpsM, the hydrophobic component of the ABC-transporter involved in the export of polysialic acid in Escherichia coli K1. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:871–881. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reeves P R, Hobbs M, Valvano M A, Skurnik M, Whitfield C, Coplin D, Kido N, Klena J, Maskell D, Raetz C R H, Rick P D. Bacterial polysaccharide synthesis and gene nomenclature. Trends Microbiol. 1996;4:495–503. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(97)82912-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reizer J, Reizer A, Saier M H. A new subfamily of bacterial ABC-type transport systems catalysing export of drugs and carbohydrates. Protein Sci. 1992;1:1232–1236. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560011012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rick P D, Mayer H, Neumeyer B A, Wolski S, Bitter-Suermann D. Biosynthesis of enterobacterial common antigen. J Bacteriol. 1985;162:494–503. doi: 10.1128/jb.162.2.494-503.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roberts I S. The biochemistry and genetics of capsular polysaccharide production in bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1996;50:285–351. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roberts I S, Mountford R, High N, Bitter-Suermann D, Jann K, Timmis K N, Boulnois G J. Molecular cloning and analysis of the genes for the production of the K5, K7, K12, and K92 capsular polysaccharides in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1986;168:1228–1233. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.3.1228-1233.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roberts I S, Mountford R, Hodge R, Jann K B, Boulnois G J. Common organization of gene clusters for production of different capsular polysaccharides (K antigens) in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:1305–1310. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.3.1305-1310.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sancar A, Hack A M, Rupp W D. Simple method for identification of plasmid-coded proteins. J Bacteriol. 1979;137:692–693. doi: 10.1128/jb.137.1.692-693.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walker J E, Sarste M, Runswick M J, Gay N J. Distantly related sequences in the α- and β-subunits of ATP synthase, myosin, kinases and other ATP-requiring enzymes, and a common nucleotide binding fold. EMBO J. 1982;1:945–951. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01276.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Walker R D, Hopkins F M, Shultz T W, McCracken M D, Moore R N. Changes in leukocyte populations in pulmonary lavage fluids of calves after inhalation of Pasteurella haemolytica. Am J Vet Res. 1985;46:2429–2433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ward C K, Inzana T J. Identification and characterization of a DNA region involved in the export of capsular polysaccharide by Actinobacillus pleuropneumoniae serotype 5a. Infect Immun. 1997;65:2491–2496. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2491-2496.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Whitely L O, Maheswaran S K, Weiss D J, Ames T R. Immunohistochemical localization of Pasteurella haemolytica A1-derived endotoxin, leukotoxin, and capsular polysaccharide in experimental bovine pasteurella pneumonia. Vet Pathol. 1990;27:150–161. doi: 10.1177/030098589002700302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yates W D G. A review of infectious bovine rhinotracheitis, shipping fever pneumonia and viral-bacterial synergism in respiratory disease of cattle. Can J Comp Med. 1982;46:225–263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yates W D G, Stockdale P H G, Babiuk L A, Smith R J. Prevention of experimental bovine pneumonic pasteurellosis with an extract of Pasteurella haemolytica. Can J Comp Med. 1983;47:250–256. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]