Graphical abstract

Keywords: solid-state NMR, structure determination, membrane curvature, viroporin, oligomerization

Abstract

The severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) envelope (E) protein forms a pentameric ion channel in the lipid membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC) of the infected cell. The cytoplasmic domain of E interacts with host proteins to cause virus pathogenicity and may also mediate virus assembly and budding. To understand the structural basis of these functions, here we investigate the conformation and dynamics of an E protein construct (residues 8–65) that encompasses the transmembrane domain and the majority of the cytoplasmic domain using solid-state NMR. 13C and 15N chemical shifts indicate that the cytoplasmic domain adopts a β-sheet-rich conformation that contains three β-strands separated by turns. The five subunits associate into an umbrella-shaped bundle that is attached to the transmembrane helices by a disordered loop. Water-edited NMR spectra indicate that the third β-strand at the C terminus of the protein is well hydrated, indicating that it is at the surface of the β-bundle. The structure of the cytoplasmic domain cannot be uniquely determined from the inter-residue correlations obtained here due to ambiguities in distinguishing intermolecular and intramolecular contacts for a compact pentameric assembly of this small domain. Instead, we present four structural topologies that are consistent with the measured inter-residue contacts. These data indicate that the cytoplasmic domain of the SARS-CoV-2 E protein has a strong propensity to adopt β-sheet conformations when the protein is present at high concentrations in lipid bilayers. The equilibrium between the β-strand conformation and the previously reported α-helical conformation may underlie the multiple functions of E in the host cell and in the virion.

Introduction

The SARS-CoV-2 is the causative agent of the COVID-19 pandemic, which claimed more than six million lives worldwide by the end of 2022. Although COVID vaccines are now widely available, antiviral treatments for infected individuals are still limited. One antiviral drug target is the envelope (E) protein, one of the three membrane proteins of the virus.1 In SARS-CoV-1, the E protein consists of 76 amino acid residues: a short N-terminus spans residues 1–7, a transmembrane (TM) domain spans residues 8–38, and a C-terminal cytoplasmic domain (CTD) encompasses residues 39–76. The protein localizes to the ERGIC compartment of infected cells, with the C-terminus oriented towards the cytoplasm.2 E shows ion channel activities in three constructs: a transmembrane construct (ETM, residues 8–38),3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 a cytoplasmic-truncated construct (ETR, residues 8–65),10 and full-length E (EFL).11 The channel activity of E is a virulence factor: channel-inactivating mutations3 in mouse-adapted SARS-CoV reduced lung edema and lowered the proinflammatory cytokine levels.6 Ca2+ fluxes through the E channel are implicated in the pathogenicity of SARS-CoV-1 by activating the NOD-, LRR- and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasomes.5 This Ca2+ flux follows a three-orders-of-magnitude concentration gradient, from ∼0.4 mM in the ERGIC lumen to ∼0.1 μM in the cytoplasm.12, 13 The E protein of SARS-CoV-2 is highly homologous to the SARS-CoV counterpart, differing only by three residues and one deletion, all localized in the CTD. The TM sequence of the two proteins is identical. Therefore, the structure and function of these two proteins are likely similar.

The structure and stoichiometry of ETM have been investigated in a variety of membrane-mimetic environments. Gel electrophoresis and sedimentation equilibrium data in perfluorooctanoic acid (PFO) and dodecylphosphocholine (DPC) detergents suggested that ETM forms pentamers.9 This stoichiometry was recently firmly established for membrane-bound ETM using 19F spin diffusion NMR,14 where the protein was reconstituted in a cholesterol-containing ERGIC-mimetic lipid bilayer. Pentamer formation was also reported for ETR10 and EFL11, 15 based on gel electrophoresis and sedimentation equilibrium data obtained from PFO, C14 betaine and DPC/sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS) micelles. Solution NMR data indicate that ETM is α-helical in DPC micelles,16 and infrared spectra of DMPC bilayer-bound ETM showed amide I and II bands that are consistent with a helical conformation.17 Recently, the high-resolution structure of SARS-CoV-2 ETM bound to ERGIC-mimetic membranes was determined using solid-state NMR (ssNMR).18 13C and 15N chemical shifts indicate that most of the TM domain is α-helical, but moderate helix non-ideality exists in the middle of the segment where three Phe residues are spaced every three residues apart.19 Interhelical 13C-15N and 13C-19F correlations constrained the structure of the five-helix bundle, showing a channel with a pore diameter of 11–14 Å and a small helix tilt angle of ∼10°. An asparagine (Asn) residue at position 15 is the main polar residue in the pore lumen, consistent with the observation that an N15A mutation abolished the ion channel activity.3, 8 This structure was solved at neutral pH in the absence of calcium ions, and likely represents a closed state of the channel.

While the TM domain of E mediates ion conduction, the CTD of E in SARS and other coronaviruses contains a C-terminal PDZ-binding motif (residues DLLV) that interacts with host proteins.20, 21, 22, 23 This host interaction is implicated in the pro-inflammatory cytokine release associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection, which causes severe tissue and organ damage.24 For example, the cell-surface receptor TLR2 recognizes the E protein to initiate priming of the inflammasome.25 E in other coronaviruses such as the infectious bronchitis virus also functions in virus assembly and budding,26 potentially through interactions with the viral matrix (M) and spike (S) proteins.1 To understand the mechanisms with which E carries out these diverse functions, it is important to elucidate the structure of the E cytoplasmic domain. For this purpose, ETR is a valuable model, as removal of the last ten residues of EFL has been shown to not affect the virulence of the virus in mice.27

To date, biophysical studies of the E CTD have yielded inconsistent information about the structure of this domain. Solution NMR studies of SARS-CoV ETR in SDS/DPC micelles showed that the CTD contains a single amphipathic helix, which spans residues 55–65.10 But in LMPG (1-myristoyl-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1′-rac-glycerol)) micelles, two amphipathic helices are reported, at residues 38–47 and 52–65.28 In n-hexadecyl-phosphocholine (HPC) micelles, SARS-CoV-2 EFL shows chemical shifts and residual 15N-1H dipolar couplings that are consistent with a single helix spanning residues 52–60.29 Thus, these data indicate that detergent-bound ETR and EFL are predominantly α-helical but the helices occur at variable positions in the amino acid sequence. Compared to these studies in detergent micelles, EFL and ETR in lipid bilayers and short cytoplasmic peptides in solution have been reported to adopt β-sheet conformations. A synthetic peptide corresponding to residues 46–60 of the CTD has a high tendency to aggregate in solution and absorbs at 1635 cm−1 in Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra,10, 30 indicating β-sheet formation. Similarly, a nine-residue peptide corresponding to residues 55–63 of the CTD assembles into amyloid fibrils in solution.31 FT-IR spectra of DMPC-bound EFL show a shoulder at 1635 cm−1, consistent with β-sheet conformation.10 The same peak is reported for ERGIC membrane-bound SARS-CoV-2 EFL and ETR.15 Therefore, these data suggest a significant propensity of the CTD to form β-sheet conformations under certain conditions.

To clarify and investigate the structure of the E CTD in a residue-specific manner, here we employ magic-angle-spinning (MAS) ssNMR spectroscopy. We reconstituted SARS-CoV-2 ETR into DMPC/DMPG membranes and measured its 13C and 15N chemical shifts and inter-residue contacts using two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) correlation experiments. The chemical shifts and distance constraints indicate that the CTD folds into a triple-stranded β-sheet, which oligomerizes into an umbrella-shaped β-bundle outside the membrane. This β-sheet structure coexists with the TM helices, indicating a clear separation of the ion channel function of E from its host-interaction and virus assembly functions.

Materials and methods

Cloning, expression and purification of SARS-CoV-2 ETR (residues 8–65)

The SARS-CoV-2 ETR (8ETG TLIVNSVLLF LAFVVFLLVT LAILTALRLA AYAANIVNVS LVKPSFYVYS RVKNL65) spans residues 8–65 of the full-length protein and contains three Cys to Ala mutations, C40A, C43A, and C44A. The construct was derived from a SARS-CoV ETR construct in the pNIC28-Bsa4 plasmid10, 32 by introducing two changes at T55S and V56F, which are the only two residues that differ between SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 E proteins between residues 1–68. The DNA sequence was confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Axil Scientific, Singapore). The plasmid was transformed into competent E. coli BL21 CodonPlus (DE3) pLysS cells (Agilent) for protein expression and then kept at −80 °C as a glycerol stock.

A 50 mL LB starter culture was inoculated from the glycerol stock and grown overnight with shaking at 37 °C. This starter culture was used to inoculate 0.8 L of ZYM-505 media33 at an inoculum ratio of 1:100. The culture was grown in a 1 L fermenter (Winpact, USA) at 37 °C with the dissolved oxygen level maintained at 40% by controlling the agitation (up to 900 rpm), aeration (up to 1 vessel volume per minute), and oxygen supplementation, cascaded in the listed order. After 6 h, cells were collected by centrifugation at 7500g for 8 min at 30 °C. The pellet was resuspended in 0.8 L M9 media for high-cell density culture34 containing 0.1% w/v NH4Cl and 0.4% w/v glucose. The culture was transferred into a sterile 1 L fermenter vessel and further grown under the same condition as before centrifugation. After 1 hour, the temperature was lowered to 18 °C, the media was supplemented with 0.1% w/v NH4Cl and 0.4% w/v glucose, and protein expression was induced by adding 0.5 mM IPTG. Expression proceeded overnight, then the cells were harvested the next day by centrifugation at 7500g for 10 min at 4 °C. The pellets were flash-frozen with liquid nitrogen and kept at −80 °C until used. Isotopically labeled ETR samples were produced by substituting unlabeled NH4Cl and glucose with 15N-labeled NH4Cl and uniformly 13C-labeled glucose (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories). Three isotopically labeled proteins were produced: 15N-labeled ETR, 13C-labeled ETR, and doubly 15N, 13C-labeled ETR.

Frozen cell pellets were resuspended, lysed, clarified, and applied to Ni-NTA resin for purification by affinity column chromatography as described previously.10 The only change is that the elution buffer in the current study contained 0.1% w/v of N,N-dimethyldodecylamine N-oxide (LDAO). Following elution, the His6 tag was cleaved by adding 1:10 mol/mol TEV protease in the presence of 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). The reaction mixture was agitated by rolling at 4˚C for 64 hours, then precipitated using trichloroacetic acid, and lyophilized. The lyophilized powder was dissolved in 5% v/v TFA in acetonitrile and injected into a Phenomenex Jupiter C18 column (10 µm particle size, 250 × 21.2 mm). The cleaved protein was fractionated from uncleaved protein using a linear gradient of isopropanol: acetonitrile (4:1 v/v with 0.1% v/v TFA) on a Shimadzu Prominence HPLC system. The identity and purity of the fractions was assessed by SDS-PAGE and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. The solvent was removed from pooled fractions in a vacuum concentrator, then the protein was lyophilized in the presence of 1 mM HCl. The isotopic labeling level was found to be close to 100% based on the MS spectra. The final ETR yield ranged from 5–10 mg per liter of M9 culture.

Membrane sample preparation for solid-state NMR experiments

Five membrane samples were prepared for this study. Three samples contained uniformly 13C, 15N-labeled ETR, one contained 13C-labeled ETR, and one contained a 1: 1 mixture of 13C-labeled and 15N-labeled ETR. All membrane samples were prepared in a pH 7.5 Tris buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA and 0.2 mM NaN3).

All lipids were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids. Most ssNMR spectra were measured on ETR bound to a dimyristoyl-phosphatidylcholine (DMPC):dimyristoyl-phosphoglycerol (DMPG) (4:1) membrane. This membrane is denoted as DMPX in this work. A second lipid mixture is an ERGIC-mimetic membrane that consists of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC), 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (POPE), bovine phosphatidylinositol (PI), 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-serine (POPS), and cholesterol (Chol) at a molar ratio of 45:20:13:7:15.18 Thus, both membranes have similar negative charge fractions of 20–24 mol%, excluding cholesterol. Most NMR samples used a protein/lipid molar ratio (P/L) of 1:20, where the concentrations of phospholipids but not cholesterol are considered. ETR (residues 8–65) has an isoelectric point of 9.8 and an estimated charge of +2.9 at pH 7.0. Thus, at the P/L of 1:20, the protein and membrane charges are approximately balanced.

To assess spectral resolution and sensitivity, we prepared DMPX and ERGIC membrane samples that contained only 2 mg 13C, 15N-labeled ETR. We found similar chemical shifts between the two samples and higher spectral resolution for the DMPX sample. Therefore, for 3D correlation experiments that require extensive signal averaging, we used the DMPX-bound ETR. About 5 mg 13C, 15N-labeled ETR was used for these resonance assignment experiments. Intermolecular 2D NHHC and long-mixing 2D CC experiments were conducted on a sample containing 4 mg each of 13C-labeled ETR and 15N-labeled ETR. This mixture was reconstituted into the DMPX membrane at P/L 1: 15 to obtain sufficient spectral sensitivity.

Proteoliposomes of ETR were prepared using an organic-phase mixing protocol. Care was taken to ensure that the protein was fully dissolved throughout the sample preparation process, since ETR has a propensity for aggregation. Lipids were first dissolved in 400 μL chloroform, then chloroform was removed under a gentle stream of nitrogen gas, and the mixture was dried overnight under vacuum at room temperature to obtain a clear film. We dissolved 1 mg aliquots of lyophilized ETR in 0.5 mL trifluoroethanol (TFE). The solubility of ETR in TFE was ∼1 mg/250 μL, thus the solution was free of aggregates. The protein solution was added to the dry lipid film, mixed by pipetting up and down, then vortexed. TFE was then removed with nitrogen gas, and the mixture was dried overnight under vacuum at room temperature. The mixed 13C-labeled and 15N-labeled ETR was prepared similarly. Here, the appropriate amount of lipids was dissolved in 400 µL chloroform, separated into four 100-µL aliquots and dried. 1 mg aliquots of 13C-labeled or 15N-labeled ETR were separately dissolved in 0.5 mL TFE, then combined and added to one of the four aliquots of dry lipids. This procedure was repeated until all 8 mg of ETR were mixed with the lipids.

For all samples, the dry proteoliposome film was resuspended in 3 mL of buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 5 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM NaN3) by bath sonication at 25˚C for at least 30 min until the suspension became homogeneous. This sonication step was not necessary for ETM but was found to be important for obtaining homogeneous suspensions of ETR.18 The solution was subjected to nine freeze–thaw cycles between liquid nitrogen and a 42 °C water bath. The resulting proteoliposome solution appeared homogeneous and translucent. The solution was ultracentrifuged for 2 hours at 164,000g and 4 °C to obtain a membrane pellet. This pellet was placed in a desiccator until it reached a hydration level of 40% (w/w), before it was spun into an MAS rotor for ssNMR experiments.

Measurements of ETR ion channel activities in lipid bilayers

Planar lipid bilayers were formed by apposition of two lipid monolayers on a 15 μm-thick Teflon partition with a 100 μm diameter orifice that separated two identical chambers.35, 36 All lipids were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). A lipid mixture that mimics the ERGIC membranes contained dioleoyl-phosphatidylcholine (DOPC), dioleoyl-phosphatidylethanolamine (DOPE), dioleoyl-phosphatidylserine (DOPS), dioleoyl-phosphatidylinositol (DOPI), and cholesterol (Chol) with a DOPC: DOPE: DOPI: DOPS: Chol molar ratio of 45:20:13:7:15. Prior to addition to the chamber, lipids dissolved in chloroform were mixed at the desired ratio, then chloroform was evaporated under an Argon constant flow followed by pentane addition. The orifice was pretreated with a 1% solution of hexadecane in pentane. Aqueous solutions were 100 mM CaCl2 at pH 6.0. The pH of the solution was controlled using a GLP22 pH meter (Crison). All measurements were performed at room temperature (23 ± 1 °C).

ETR (residues 8–65) was inserted into the ERGIC-mimetic membrane by adding 0.5–1.0 μl of a 2.5 mg/mL ETR solution in acetonitrile: isopropanol (40:60) to one side of the chamber (cis side). An electrical potential was applied using Ag/AgCl electrodes in 2 M KCl, 1.5% agarose bridges assembled within standard 250 μL pipette tips. The potential was defined as positive when it was higher on the cis side, whereas the trans side was set to ground. An Axopatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) in the voltage-clamp mode was used to measure the current and the applied potential. Data were filtered by an integrated low pass 8-pole Bessel filter at 10 kHz, saved at a sampling frequency of 50 kHz with a Digidata 1440A (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) and analyzed using the pClamp 10.7 software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). For visualization, current traces were digitally filtered at 500 Hz using a low-pass Bessel (8-pole) filter. The chamber and the headstage were isolated from external noise sources with a double metal screen (Amuneal Manufacturing Corp., Philadelphia, PA). Channel conductance was obtained from currents measured under an applied potential of +100 mV in symmetrical salt solutions. Current was calculated from a single-Gaussian fitting of the histogram of current jump amplitudes generated after addition of ETR to the chamber. The standard deviation of the data corresponds to the sigma obtained from the Gaussian fit. The histogram contains events from a minimum of 3 independent experiments.

Solid-state NMR experiments

All ssNMR spectra were measured on a Bruker Avance II 800 MHz (18.8 T) spectrometer using a Black Fox 3.2 mm MAS probe. The MAS frequencies were 14 kHz or 10.5 kHz. Typical radiofrequency (RF) field strengths were 50–91 kHz for 1H, 50–63 kHz for 13C, and 33–42 kHz for 15N. Sample temperatures were estimated from the water 1H chemical shift δwater in ppm using the equation Tsample = (7.762-δwater) × 96.9 K.37 13C chemical shifts are reported on the tetramethylsilane scale using the adamantane CH2 chemical shift at 38.48 ppm as an external standard. 15N chemical shifts are reported on the liquid ammonia scale using the N-acetylvaline peak at 122.00 ppm as an external standard.

2D 13C–13C correlation (CC) experiments were conducted using COmbined R2nv-Driven (CORD) mixing38 for 13C spin diffusion. 2D 15N-13C correlation (NC) experiments and 3D NCACX, NCOCX and CONCA39 correlation experiments used SPECtrally Induced Filtering In Combination with Cross Polarization (SPECIFIC-CP)40 for 15N-13C polarization transfer. Water-edited 2D NC spectra41, 42 were measured using 1H mixing times of 9 ms and 100 ms. The experiment selects the water 1H magnetization using a Hahn echo containing a Gaussian 180˚ pulse of 0.95 ms, then transfers this magnetization to protein protons for detection through 13C. An Hγ-edited 2D CC spectrum was measured using the same pulse sequence, except that the 1H carrier frequency was placed at 3.264 ppm to be on resonance with the DMPC Hγ peak. The Gaussian 180˚ pulse length for this Hγ selection was 2.86 ms and the 1H mixing time was 25 ms. 2D 1H–13C heteronuclear correlation (HETCOR) spectra43, 44 were measured using a 1H spin diffusion mixing time of 4 ms and a total 1H T2 filter time of 1.43 ms, which corresponded to 20 rotor periods under 14 kHz MAS. 2D NHHC correlation spectra45 for obtaining intermolecular correlations were measured using a 1H mixing time of 0.5 ms. Additional parameters for the solid-state NMR experiments are given in Table S1.

NMR spectra were processed using the Bruker TopSpin software, and chemical shifts were assigned using the Sparky software.46 Backbone (ϕ, ψ) torsion angles were calculated using the TALOS-N software47 after converting the 13C chemical shifts to the DSS scale. 2D hydration maps of water-edited 2D NC spectra were obtained by dividing the intensities of the 9 ms spectrum (S) by the 100 ms spectrum (S0) using a Python script.42, 48 The intensities of the two spectra were read using the NMRglue package.49 Spectral noise was filtered by setting signals lower than 3.5 times the noise level to zero for the 9 ms spectrum and to a large number (900,000) for the 100 ms spectrum. This 2D hydration map reflects the water accessibilities of the protein residues.

XPLOR-NIH structure calculations

We calculated the ETR structure using the XPLOR-NIH software50 hosted on the NMRbox.51 For each simulated annealing run, five extended monomers (residues 8–65) were placed in a fivefold symmetric geometry, with each monomer parallel to the C5 axis of the pentamer and the center of each monomer being 20 Å from the symmetry axis. TM residues E8-R38 were included in the structure calculation. However, due to the scarcity of interhelical contacts for these residues in ETR, we used previously reported interhelical 15N-13C contacts obtained from the NHHC spectra of the ETM peptide.18 The TM helices and their inter-residue contacts are not necessary for constraining the CTD structure; however, their inclusion in simulated annealing prevented undesirable entanglement of the initial CTD random coils, which resulted in structures with poorly folded conformations.

A total of 10,000 independent simulated annealing runs were performed with 5,000 steps of torsion angle dynamics at 5,000 K, followed by annealing to 20 K in decrements of 10 K with 100 steps at each temperature. Energy minimization was subsequently carried out in torsion angle and then Cartesian coordinates. The five monomers were restrained to be identical using the non-crystallographic symmetry term PosDiffPot and the translational symmetry term DistSymmPot, with scales of 1000 and 100, respectively. Chemical-shift constrained (ϕ, ψ) torsion angles were implemented with the dihedral angle restraint term CDIH, with scale ramped from 50 to 500. Due to ambiguity in resonance assignment, we excluded the TALOS predictions for residues 8–11 and 37–44. Torsion angle ranges were set to the higher value between twice the TALOS-N predicted uncertainty and 20°. Experimentally measured distance constraints were included using the NOE potential, which was set to “soft”, with a scale ramped from 2 to 30. Distance upper limits were set to 9.0 Å for the NHHC restraints measured with 0.5 ms 1H mixing45 and 7.0 Å for the CC restraints measured with 250 ms mixing.18 Implicit hydrogen bonds were included with the HBDB potential. Standard bond angles and lengths were set with terms BOND, ANGL and IMPR, and the nonbonded potential was implemented with XPLOR’s VDW term.

Spin diffusion contacts were applied to each of the five monomers: intermolecular contacts could be with either the molecule on the left or on the right of the source molecule, so they were set to have a twofold directional ambiguity in the structure calculation. Contacts that have unknown intramolecular or intermolecular origins were set to have threefold ambiguity, contacting the molecule on the left, on the right, or to the same molecule. NHHC contacts are unambiguously intermolecular because they are between 15N-labeled monomers and 13C-labeled monomers. Contacts observed in the 250 ms 2D CC spectrum of the 1:1 diluted sample were sorted by the intensity ratios (S/S0) between the diluted and undiluted spectra into intramolecular (S/S0 > 0.8), intermolecular (S/S0 < 0.6), or unknown (0.6 < S/S0 < 0.8). The intensity cutoffs were validated by the fact that all intra-residue contacts have intensity ratios of 0.8–1.2 between diluted and undiluted samples. Contacts from all other spectra were set to have unknown intramolecular or intermolecular origins, with the exception of sequential contacts, which were assumed to be intramolecular. Table S3 summarizes the number of spin diffusion contacts of different types, and Table S4 lists all contacts used for structure calculation.

The 10,000 simulated structures were sorted by total energy. The structures did not converge. Thus we sorted the topology of the 20 lowest energy structures based on the relative orientation of the three β-strands (residues 45–65). Four topologies were identified. We took the lowest energy structure of a given topology as representative of that class, and measured the pairwise all-atom RMSD from every other structure with the same topology to the class representative. This analysis showed that the all-atom RMSD within each topology class is always less than 4 Å for residues 45–65. The next 80 lowest energy structures were also characterized for topology and RMSD to the four classes, and all but 22 out of 80 structures fit into one of the four classes with an RMSD of less than 4 Å. The all-atom RMSDs between different topologies range from 3 to 15 Å. Most of the remaining models showed putatively unphysical threading of one monomer through loops in the adjacent monomers. Images of the ETR structural models were generated in PyMOL v2.3.4.

Results

In this study, we investigate the SARS-CoV-2 E cytoplasmic structure using the ETR construct (residues 8–65) instead of EFL, because EFL is prone to aggregation30 and mouse data show that removal of the last ten residues of the full-length protein did not reduce the virulence of the virus.27 We expressed ETR as a His-tagged fusion protein, which was then cleaved and purified using affinity chromatography and HPLC. The HPLC chromatogram and SDS-PAGE (Figure S1) indicate high purity of the protein for structural analysis by ssNMR.

Ion channel activity of ETR

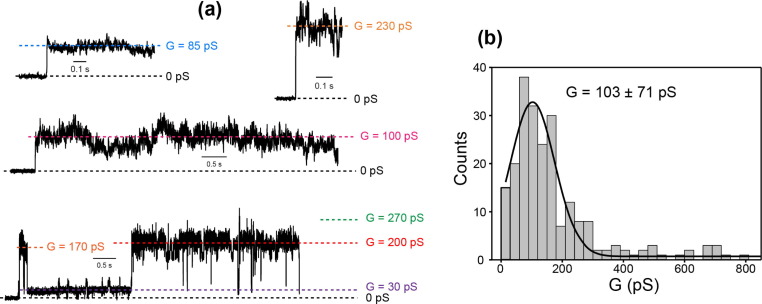

To verify the ion channel activities of ETR and investigate whether they differ from those of ETM, we measured the conductance of ETR in an ERGIC-mimetic lipid membrane. In 100 mM CaCl2 at pH 6, ETR exhibits both single and multi-channel insertion events and conductance jumps, with variable conductance and stability (Figure 1 (a)). The most probable conductance is 103 pS, which is similar to the most probable conductance of 110 ± 40 pS for ETM under similar conditions.5, 8 The ETR conductance is more variable than ETM, as shown by a larger standard deviation of 71 pS. We attribute this variability to the destabilizing effects of the cytoplasmic residues to the TM helices. Overall, these data indicate that ETR forms functional channels in ERGIC-mimetic lipid membranes.

Figure 1.

Membrane-bound ETR conducts ions across ERGIC-mimetic lipid bilayers. (a) Representative current recordings (reported in pS) show channel opening events with variable durations and conductance. The measurements were conducted in solutions containing 100 mM CaCl2. Applied voltage was +100 mV. (b) Histogram of conductance jumps of ETR in 100 mM CaCl2 solution under +100 mV applied voltage. Solid line indicates Gaussian fitting of the histogram, which yields a most probable G value of 103 pS with a standard deviation of 71 pS. The total number of events was 240.

Backbone conformation of ETR in lipid bilayers

We measured most ssNMR spectra of ETR in the DMPX membrane. One-dimensional (1D) 13C NMR spectra show relatively resolved signals, whose intensities are twofold higher in the gel phase of the DMPX membrane at 263 K compared to the liquid-crystalline phase at 303 K (Figure 2 (a)). This temperature dependence indicates that ETR is partially mobile in the liquid-crystalline membrane. 2D NC and CC spectra show many α-helical chemical shifts, as expected for the TM domain. In addition, we also observed β-sheet signals at characteristic chemical shifts of Ser, Val and Ile residues (Figure 2(b, c)). These β-sheet chemical shifts are absent from the ETM spectra. The 13C and 15N linewidths of the β-sheet signals are 0.6–0.8 ppm and 1.0–1.3 ppm, respectively, indicating high conformational homogeneity. In comparison, the α-helical signals have linewidths of 1.0–1.2 ppm for 13C and 1.5–2.0 ppm for 15N. These linewidths are broader than the α-helical signals of ETM, even though the average chemical shifts remain the same. Therefore, the TM domain becomes more disordered in the presence of the CTD. Given these broader linewidths, and because the TM helix structure is known from recent studies of ETM,14, 18, 19 we focus on structure determination of the CTD in this study.

Figure 2.

1D and 2D NMR spectra of ETR in the DMPC: DMPG membrane. (a) 13C cross-polarization (CP) and direct-polarization (DP) spectra of ETR (black) at 305 K and 275 K. The CP spectra preferentially detect immobilized residues whereas the DP spectrum preferentially detects mobile residues. The CP spectrum of ETM (orange) is also shown for comparison. (b) 2D NC spectrum of ETR (blue) measured at 305 K, overlaid with the ETM spectrum (orange) for comparison. ETR assignments obtained from 3D correlation spectra are indicated. (c) 2D CC spectrum of ETR (blue) measured at 305 K, overlaid with the ETM spectrum (orange). β-sheet chemical shifts are observed for residues such as Ser and Val, which are absent in the ETM spectrum.

To assess if the conformational disorder of ETR is sensitive to the membrane environment, we compared the spectra of ETR in the DMPX membrane versus the ERGIC membrane (Figure S2(a, b)). The 13C and 15N chemical shifts are identical, but the linewidths are larger in the ERGIC membrane, suggesting that the cholesterol- and PI-containing ERGIC lipid mixture increases the protein disorder without affecting the average conformation. Thus, we used the DMPX membrane for 3D correlation experiments. To assess if the β-sheet conformation of the CTD is a result of high protein concentrations or is intrinsic to the amino acid sequence, we reduced the P/L ratio from 1:20 to 1:60. The diluted sample shows a nearly identical 2D CC spectrum as the 1:20 sample, with β-sheet chemical shifts coexisting with α-helical signals (Figure S2(c)). Thus, within the P/L range of 1:20 to 1:60, the β-sheet conformation of the CTD is intrinsic to membrane-bound ETR.

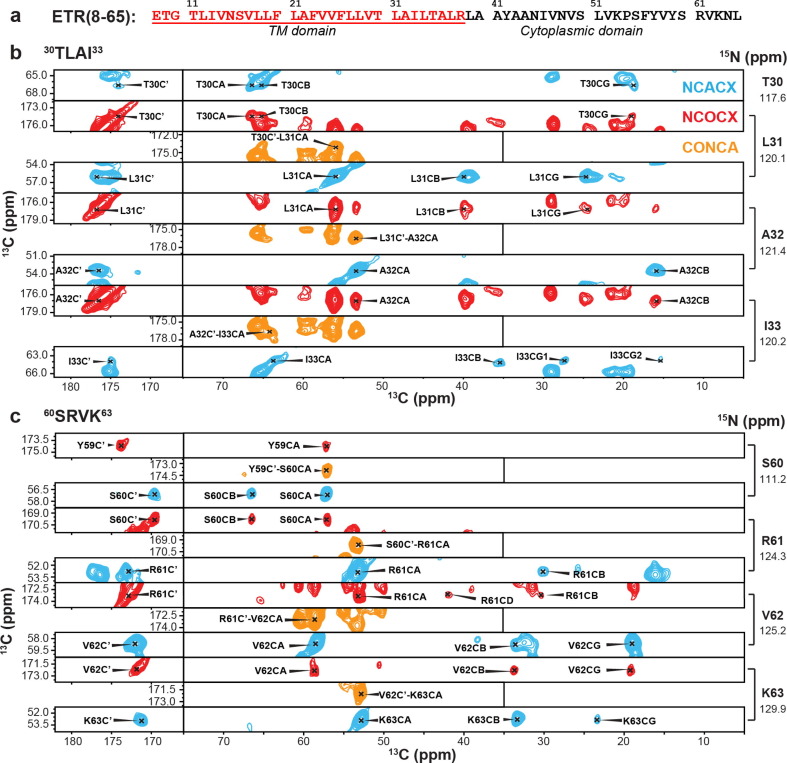

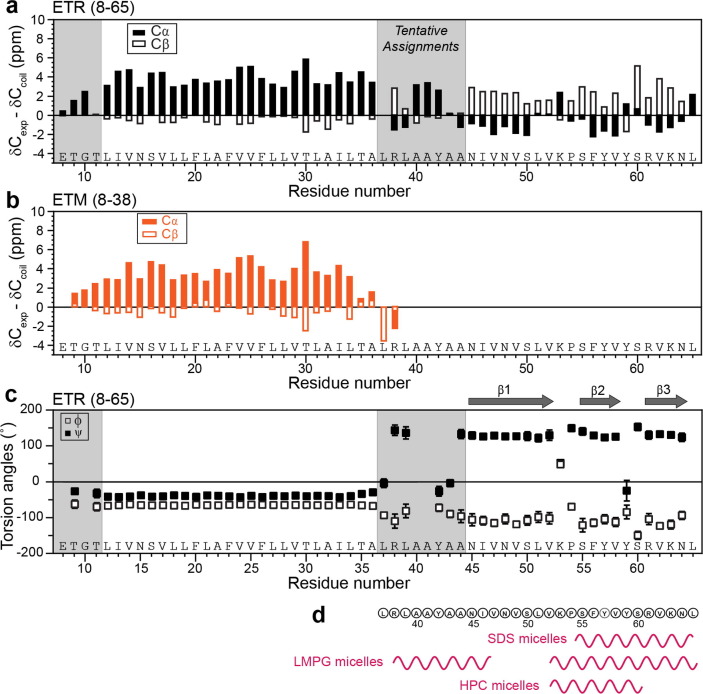

To determine the residue-specific conformation of ETR, we resolved and assigned the 13C and 15N chemical shifts using 3D NCACX, NCOCX and CONCA correlation experiments. Figure 3 shows representative strips for TM and CTD residues. Well-resolved signals are observed for both domains, which allowed sequential assignment of 46 out of the 58 residues (Table S2). α-helical chemical shifts are observed for residues from the N-terminus to A36, whereas β-sheet chemical shifts are observed for residues N45 to L65 (Figure 4 (a)). The TM residues exhibit similar chemical shifts as in ETM, except for residues 8–13 and 34–38 (Figure 4(b)).18 The (ϕ, ψ) torsion angles predicted from these chemical shifts indicate that residues 12–36 form the α-helical core of ETR, whereas residues 45–64 contain three β-strands (Figure 4(c)). The β1 strand extends from N45 to V52, β2 from S55 to V58, and β3 from R61 to N64. These three β-strands are separated by the Pro-containing 53KP54 and by 59YS60.

Figure 3.

Resonance assignment of ETR bound to DMPC: DMPG membranes. (a) Amino acid sequence of ETR (residues 8–65). The TM residues are colored in red. (b, c) Representative 3D strips of the NCACX, NCOCX and CONCA spectra for (b) TM residues 30TLAI33 and (c) cytoplasmic residues 60SRVK63.

Figure 4.

Secondary structure of membrane-bound ETR obtained from 13C and 15N chemical shifts. (a) Cα and Cβ secondary chemical shifts. Most CTD residues show negative Cα and positive Cβ secondary shifts, indicating a β-sheet conformation. Residues 8–11 and 37–44 are tentatively assigned. (b) Cα and Cβ secondary chemical shifts of ETM.18 (c) (φ, ψ) torsion angles of ETR. Membrane-bound E shows three β-strands in the CTD, separated by K53-P54 and Y59-S60. (d) Comparison of the secondary structures of the E CTD in different membrane-mimetic environments.16, 28, 29 Detergent-bound E has α-helical CTD conformations.

Membrane topology of the cytoplasmic domain

To probe the membrane topology of the triple-stranded CTD, we measured the depth of insertion of ETR in the DMPX membrane using a 2D 1H–13C HETCOR experiment.52 The experiment correlates the lipid and water 1H chemical shifts with the protein 13C signals after a 1H mixing period. Even with a short mixing time of 4 ms, the 2D spectrum already exhibits extensive correlation peaks between the lipid chain protons at 1.3 ppm and the α-helical chemical shifts of Val, Leu and Ala residues. This indicates that the α-helical TM residues are well inserted into the membrane (Figure 5 (a, b)). The water 1H cross section at 4.7 ppm shows many cross peaks with β-sheet signals of the cytoplasmic residues such as S60 and S55 Cβ, P54 Cδ, and F56 and Tyr aromatic carbons. In the aromatic region of the HETCOR spectrum, F20, F23 and F26 in the TM domain show cross peaks with the lipid chain protons whereas the cytoplasmic F56 exhibits cross peaks with water. Strong cross peaks between Tyr and water are also observed. There are three Tyr residues in ETR, all located in the CTD, thus these Tyr-water cross peaks indicate the high water accessibility of the CTD. These Phe and Tyr residues have partially resolved 13C chemical shifts (Figure S3), which make them informative probes of the differential depths of insertion and water exposure of the TM and cytoplasmic domains. Together, these data indicate that the β-sheet CTD is well exposed to water while the middle of the TM domain is deeply inserted into the membrane.

Figure 5.

Depth of insertion and water accessibility of DMPC:DMPG membrane-bound ETR. (a) 2D 1H–13C HETCOR spectrum measured with 4 ms 1H mixing. (b) 1D cross sections of the HETCOR spectrum at the lipid CH2, headgroup Hγ, and water 1H chemical shifts. These cross sections show the signals of deeply inserted residues, membrane-surface residues, and water accessible residues, respectively. (c) Water-edited 2D NC spectrum. Contour levels represent the intensity ratios of spectra measured with 9 ms (S) and 100 ms (S0) 1H mixing. High intensities indicate high water accessibility. (d) Water-transferred intensities of ETR versus ETM. Closed and open symbols indicate resolved and overlapping peaks, respectively.

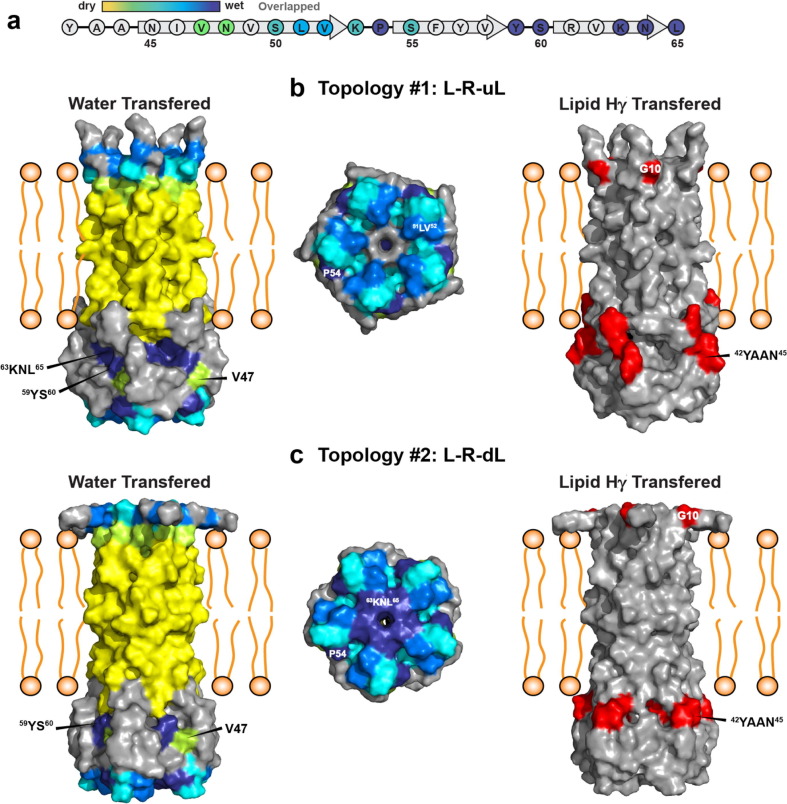

The lipid headgroup Hγ cross section at 3.26 ppm in the HETCOR spectrum provided additional information about the membrane topology of ETR. Cross peaks with G10, A43/A44/N45, and a Tyr sidechain are observed. The most likely Tyr that gives rise to this cross peak is Y42, since Y57 and Y59 are adjacent to F56 and other CTD residues and are thus most likely well hydrated. These results indicate that the linker between the TM and cytoplasmic domains lies near the membrane surface. Other cross peaks at both α-helical and β-sheet chemical shifts are also detected. To better resolve the signals of these membrane-surface residues, we conducted a Hγ-edited 2D CC experiment, which selectively transfers the Hγ magnetization to protein protons for detection through 13C (Figure S4). With a 1H mixing time of 25 ms, the Hγ-edited 2D CC spectrum exhibited residual intensities for α-helical Val and Leu residues, β-sheet CTD residues such as V47 or V49, and Ala and Tyr residues in the linker region. Intensity analysis indicates that the α-helical Val and Leu residues have low Hγ-transferred intensities while the 42YAA44 segment has high Hγ-transferred intensities. However, this Hγ transfer reduces the spectral sensitivity by 100-fold compared to the unedited 2D CC experiment, thus the intensity differences are not significantly larger than the experimental uncertainty. Thus, we only consider the 4 ms 1H–13C HETCOR spectrum in evaluating the relative merit of the various membrane topologies obtained from the structure calculation.

Complementing the 2D 1H–13C HETCOR spectrum, we also measured water-edited 2D NC spectra to determine the water-accessible residues.41, 42 The 2D NC spectrum has higher site resolution than the 2D CC spectrum, and detects water magnetization transfer to amide protons, which is independent of the presence or absence of exchangeable protons in the amino acid sidechains. Thus, the 2D NC spectrum is advantageous over the 2D CC spectrum for the water accessibility analysis. Two water-edited NC spectra were measured, using 9 ms and 100 ms 1H mixing. Their intensity ratios represent the relative water accessibility of the amide protons. Well hydrated residues show high intensities in the 9 ms spectrum whereas dry residues exhibit low intensities. Figure 5(d) shows that residues in the middle of the TM domain display low water-transferred intensities whereas β-sheet signals have high water-edited intensities. Among the CTD residues, V47 and N48 have the lowest hydration, comparable to the water accessibility of TM residues, indicating that this portion of the CTD is shielded from water. This result is consistent with the close contact of 47VNVSL51 with the membrane surface Hγ.

To obtain information about the three-dimensional fold of the CTD, we prepared a 1:1 mixture of 13C-labeled ETR and 15N-labeled ETR, and measured its 2D NHHC spectrum (Figure 6 (a)). Due to the mixed labeling, all correlation signals are intermolecular. We observed intermolecular contacts between S60 and S60, L65 and N64, and S60 and N48. The first two contacts indicate that the β3 strands of different subunits are in close proximity, thus β3 should reside near the C5 symmetry axis of the pentamer. We assigned all peaks that could not correspond to the helical domain, and found 60 ambiguous contacts in addition to the 3 unambiguous contacts (Table S3, Table S4).

Figure 6.

Long-range intramolecular and intermolecular contacts of ETR. (a) NHHC spectrum of mixed 13C-labeled ETR and 15N-labeled ETR. All contacts are intermolecular. Selected assignments are indicated. (b) Region of the 250 ms 2D CC spectra of uniformly 13C-labeled ETR and 50% diluted 13C-labeled sample. Intermolecular contacts should decrease in relative intensity by 2-fold upon dilution (red assignment), while intramolecular contacts do not decrease in intensity (blue assignment). Dashed circles indicate S60-L51 cross peaks, which are more apparent in the diluted spectra due to increased signal averaging, and which are assigned to intramolecular contacts. (c) 2D cross sections of the 250 ms 3D CCC spectrum. Magenta assignments indicate long-range cross peaks. S55-I46/N64 and N48-S55 contacts are observed, which could be either intramolecular or intermolecular. (d) A representative cross section of the 250 ms 3D NCACX spectrum. A V47-V62/K63 correlation is observed (magenta assignment), which could be either intramolecular or intermolecular.

To supplement the NHHC data with additional intermolecular contacts, and to identify intramolecular long-range contacts, we measured 2D CC spectra with 250 ms 13C spin diffusion (Figure 6(b)). The experiment was conducted on both uniformly 13C, 15N-labeled ETR and the 1:1 mixed labeled sample, where the 13C-labeled ETR is diluted by an equal amount of unlabeled monomers. The two spectra are similar, except for a subset of peaks that disappeared in the diluted spectrum. These peaks include, for example, S50Cβ-N48Cα and L51/R61/K63Cα-P54Cδ. Due to the two-fold dilution, the intensities of purely intermolecular peaks are attenuated by 50%, while purely intramolecular peaks do not change intensity. Thus, these two contacts are intermolecular. The S60Cβ-L51Cβ cross peaks become more apparent in the diluted spectrum. Accounting for signal averaging differences, this cross peak has identical intensity in the diluted and undiluted samples, and is thus intramolecular.

Due to resonance overlap, few of the contacts in these 2D CC spectra can be assigned unambiguously. We thus carried out additional 3D CCC and 3D NCACX experiments with 250 ms 13C spin diffusion (Figure 6(c, d)). These spectra were measured on uniformly 13C, 15N-labeled ETR, so that the correlations can be either intramolecular or intermolecular. However, even with the additional spectral dimension, resonance overlap persists among the CTD residues and between CTD and TM residues, which precluded unambiguous assignment of many cross peaks. In total, we observed 191 inter-residue correlations for CTD residues, among which 85 can be unambiguously assigned (Table S3, Table S4). For intermolecular contacts, there is a two-fold ambiguity about which of the two neighboring monomers is in close contact with the central monomer. These multiple possibilities are taken into account in the structure calculation of membrane-bound ETR.

Structural modeling of ETR cytoplasmic domain

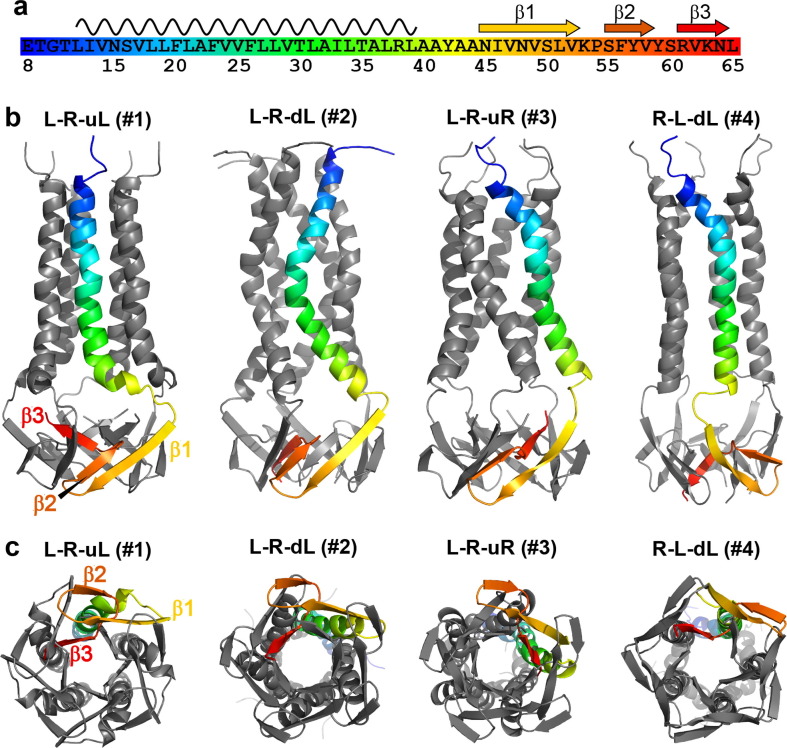

We modeled the membrane-bound structure of the CTD in XPLOR-NIH50 using 48 (ϕ, ψ) chemical-shift derived torsion angle restraints and 191 inter-residue distance restraints per monomer.14 To maintain the proper topology with respect to the TM domain, we also included 32 NHHC intermolecular restraints for the TM domain obtained from the previous study of ETM.18 We found that these restraints were insufficient to converge the simulated annealing to a single structure for residues 45–65. Instead, 78 of the lowest-energy 100 structures, including all of the 20 lowest energy structures, converged to one of four topologies (Figure 7 ). In all models, the CTD exhibits three β-strands that span approximately N45-V52, S55-V58 and R61-N64 (Figure 7(a)). While chemical shifts clearly indicate three β-strands, simulated annealing did not find hydrogen bonds for these β-strands, likely due to an insufficient number of long-range contacts. These cytoplasmic β-strands are connected to the TM domain by a linker at residues 37–44. The linker structure is poorly defined in the models due to low spectral intensities of these residues, suggesting that the linker is dynamically disordered. In all models, β1 and β2 strands are antiparallel, separated by a turn around K53-P54. β2 is followed by a turn into the radial center of the pentamer around S60, with the short β3 strand contacting β3 from other monomers and projecting in one of four directions. The four topologies in the 20 lowest energy structures differ by the orientations of the three β-strands: β1 proceeds down from the TM domain to either the left or the right; β2 is always above and antiparallel to β1; β3 proceeds radially inwards, but can point either up toward the TM domain or down toward the cytoplasm (Figure 7(b, c)). Specifically, topology 1 has a left–right-up left (L-R-uL) displacement for the three β-strands, topology 2 L-R-dL, topology 3 L-R-uR, and topology 4 R-L-dL. These four topologies represent 36, 19, 11 and 12 models among the top 100 structures. Among the 20 lowest energy models, 15 models point β3 towards the membrane (topologies 1 and 3) while 5 models point the β3 strand down toward the cytoplasm (topologies 2 and 4). The two most prevalent topologies, 1 and 2, are nearly identical, except for whether β3 is pointed up towards the membrane or down towards the solvent. Since the β3 strand is highly water accessible (Figure 8 (a)), the second topology is more probable than the first while the fourth topology is more probable than the third. Indeed, hydration surface plots (Figure 8) indicate that the second topology agrees with the water-edited data better than the first topology. The lower likelihood of the first and third topologies is also consistent with the fact that the C-terminus of full-length E contains a PDZ-binding motif that interacts with host proteins. Sequestering the β3 residues near the membrane surface is unlikely to expose the C-terminus of full-length E to the protein surface. We also depicted the membrane-surface Hγ-proximal residues in surface plots (Figure 8). These residues include G10, V12, and 42YAAN45 in the linker between the TM and CTD domains, and are satisfied in all four topologies.

Figure 7.

Range of structural models for the cytoplasmic domain of SARS-CoV-2 E in lipid bilayers. (a) Amino acid sequence of ETR, with secondary structures and color schemes indicated. (b, c) Four structural topologies of ETR obtained from simulated annealing. (b) Side views. (c) Views from the C-terminus. The NMR data do not uniquely constrain a structure, instead agree with four topologies for the cytoplasmic domain. The water accessibility of the C-terminal residues makes the first and third topologies less likely, as the C-terminus is hidden in the β-bundle, pointing towards the TM helices. We expect the true structure to be similar to one of these models, but unlike these models should have β-sheet hydrogen bonding. The helical TM domain is shown here only for context, and its structure varied widely in the simulated annealing. The variations among these models should only be considered for the cytoplasmic domain.

Figure 8.

Water accessible and membrane-surface Hγ accessible residues in ETR. (a) Relative water accessibility of the cytoplasmic residues based on the water-edited spectra. The N-terminal portion of the CTD is less hydrated than the C-terminal portion. (b, c) Water (left and middle columns) and Hγ (right column) surface plots of the first and second topologies of ETR. Hγ-proximal residues, including G10 and linker residues 42YAAN45, are shown in red. (b) In topology 1, the C-terminal 63KNL65 residues are occluded in the center of the β-bundle, inconsistent with the water-edited data. (c) In topology 2, the C-terminal residues are exposed to the solvent on the bottom surface of the β-bundle, thus this model agrees with the water-edited spectra. The hydration of residues 8–38 in ETR is represented by the water-edited data of ETM, which has similar hydration as ETR for these TM residues.

Discussion

Helix-sheet conformational difference of the E CTD

These solid-state NMR data show that the CTD of the SARS-CoV-2 E protein adopts a β-sheet rich conformation when bound to lipid bilayers at P/L ratios ranging from 1:20 to 1:60. This β-sheet conformation is observed in both DMPC: DMPG membranes and in cholesterol-containing ERGIG-mimetic membranes. This β-rich conformation differs qualitatively from the α-helical conformation found in detergent micelles and at low protein concentrations in lipid bilayers.10, 28, 29 Several factors could affect the secondary structure of the CTD: the lipid headgroup charge, the protein concentration, and the membrane curvature. We observed this β-sheet conformation in lipid bilayers containing 20–24 mol% negatively charged lipids, including DMPG, POPS and PI. This negative charge density is similar to that of eukaryotic membranes.53 Solution NMR data showed that the CTD adopts α-helical conformation in a wide range of detergents, from negatively charged SDS and LMPG to neutral HPC.29 A mixed detergent of DPC: SDS (4: 1) mixture10, 28 was also used, which has the same charge density as the DMPC: DMPG (4:1) membrane used here. An α-helical CTD was also observed in this mixed detergent. Thus, the β-sheet conformation in the current phospholipid bilayers cannot be attributed to different electrostatic interactions between the micelle samples and the membrane samples.

Instead, we attribute the β-sheet conformation to a combination of high protein concentration, low membrane curvature, and the amino acid sequence of this domain. The α-helical CTD is so far only observed at low P/L ratios and low protein/detergent (P/D) molar ratios of less than 1:100.10, 28, 29 A recent FT-IR study of ETR in the ERGIC membrane and the POPC: POPG membrane showed a β-sheet amide I peak (1632 cm−1) at P/L 1:20, which disappears at lower P/L values of 1:100 and 1:400.15 In C14 betaine micelles, ETR forms pentamers at a high P/D of 1:25 but monomers at a low P/D of 1:250. Thus, high protein concentrations both promote the pentamer state and the β-sheet conformation in lipid bilayers. In comparison, it has not been shown whether the α-helical conformation at low P/L ratios is associated with monomers or pentamers. But since E functions as a viroporin, we hypothesize that it retains the pentamer stoichiometry in lipid bilayers even at low protein concentrations. Sedimentation equilibrium data of full-length E in C14 betaine yielded a dissociation constant of P/D 1:83. Helix-helix interactions are known to be stronger in lipid bilayers than in detergent micelles.54 Thus the dissociation constant is expected to be lower (i.e. smaller P/L values). Thus, the α-helical conformation seen at low P/L ratios in the FT-IR data may be associated with the pentamer state. At high P/L ratios of ∼1:20, recent 19F ssNMR data of ETM revealed clustering of the pentamers in phosphatidylinositol (PI)-containing membranes. This clustering is manifested by the decay of the 19F spin diffusion equilibrium intensity below the value of 0.20 expected for a pentamer.14 This pentamer clustering implies that the local concentration of the E protein in the ERGIC membrane is higher than predicted by the P/L ratio. This high local concentration may promote the β-sheet conformation of the CTD by virtue of its compact shape.15

While the E concentration affects the CTD conformation,15 the data shown here and in the literature so far do not exclude the possibility that the membrane curvature also contributes to the cytoplasmic conformation. All solution NMR studies that reported an α-helical CTD were conducted in high-curvature detergent micelles, whereas all ss-NMR and FT-IR studies that reported a β-sheet CTD were conducted in low-curvature lipid bilayers. Whether the CTD adopts an α-helical conformation in high-curvature lipid bilayers will require future investigation.

Apart from the environmental effects of protein concentration and membrane curvature, the amino acid sequence of the CTD encodes for a β-sheet propensity. A Val and Tyr-rich nine-residue peptide, 55TVYVYSRVK63, forms amyloid fibrils in solution.31 Similar peptides (residues 46–60 and 36–76) in DMPC bilayers show β-sheet signals in FT-IR spectra30 but α-helical signals in detergents.55 The 56XYVY59 motif within this nine-residue segment is also present in other coronavirus E proteins, and has been shown to form β-strand conformation.10, 56 Mutation of 56XYVY59 to Ala abolished the β-sheet signals.10 We hypothesize that the conformational plasticity of this nine-residue segment may be promoted by the coexistence of β-branched Val's (Val58 and Val62), aromatic residues (Tyr57, Tyr59), and cationic residues (Arg61 and Lys63), all of which can interact with negatively charged membrane surfaces through electrostatic as well as hydrophobic interactions. In this way, the local membrane curvature and the membrane surface charge may contribute to the conformational equilibrium of the CTD.

How would the helix-sheet conformational equilibrium of the CTD support the function of E? The number of E proteins in each virion varies considerably among different coronaviruses. Estimates range from 15-30 for the α-CoV transmissible gastroenteritis virus57 to ∼100 for the γ-CoV infectious bronchitis virus.58 In infected cell membranes, the E protein is believed to be present at higher concentrations, as it interacts with the M, S, and the nucleocapsid (N) proteins to modulate the cell secretory pathway, S maturation, and production of virus-like particles.59 We hypothesize that the β-sheet CTD conformation may be operative when E is present abundantly in the low-curvature ERGIC membrane (Figure 9 ) where the β-sheet CTD interacts with the other virus proteins and with host proteins. When a new SARS-CoV-2 virus is ready to bud into the ERGIC lumen, sequestering a small number of E proteins into the virion envelope, we hypothesize that the high membrane curvature at the neck of the budding virus may shift the CTD to the α-helical conformation. This hypothesis is made by analogy with the influenza viroporin M2, which possesses an amphipathic helix C-terminal to the TM domain.60 This amphipathic helix mediates membrane scission in the last step of the influenza virus budding, by causing membrane curvature in a cholesterol-dependent manner.61, 62, 63 Mutation of aromatic residues in this amphipathic helix inhibits membrane scission and influenza virus release. Assuming that the α-helical CTD of SARS-CoV-2 E observed at low concentrations in lipid bilayers is associated with pentamers, then an amphipathic helical domain in E may similarly mediate SARS-CoV-2 budding, by inducing and sensing membrane curvature at the neck of the budding virus.

Figure 9.

Proposed model of the locations of the SARS-CoV-2 E protein with β-sheet and α-helical cytoplasmic conformations. The β-sheet cytoplasmic conformation might exist in low-curvature ERGIC membranes where the E concentration is high. Here E may interact with M and S proteins to modulate the cell secretory pathway and mediate virus assembly and budding. The α-helical cytoplasmic conformation might occur in the high-curvature neck of the budding virus or the high-curvature virion envelope, where the E concentration is low. Here the amphipathic helix in the cytoplasmic domain might generate and/or sense negative Gaussian curvature.

Interestingly, the structure of the membrane protein M of the SARS-CoV-2 virus was recently solved and found to exhibit a cytoplasmic β-sheet sandwich that connects with the TM helices.64, 65 Although M is much larger than E and is dimeric instead of pentameric, its β-sheet cytoplasmic shape is similar to the E CTD conformation. In infectious bronchitis virus and SARS-CoV, M and E proteins are known to interact through their cytoplasmic domains, and this interaction is important for the formation of virus-like particles.66, 67 We speculate that either the β-sheet CTD or the α-helical CTD of E interacts with the cytoplasmic domain of the M protein, and this M−E interaction may occur when both proteins are present at high copy numbers in the ERGIC membrane. Thus, the helix-sheet conformational equilibria of E CTD might be important for the multiple functions of E at different stages of the virus lifecycle, in membranes with different curvatures, and in contact with different proteins.

Comparison of SARS-CoV-2 E with other viroporins

The SARS-CoV-2 E protein is multi-functional and multi-domain, a characteristic that is reminiscent of the properties of other viroporins68 such as influenza A M2 (AM2), HIV Vpu,69, 70 and hepatitis C virus p7.71 Extensive high-resolution structural data60, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77 and biochemical data78, 79, 80 showed that the TM domain of AM2 forms a four-helix bundle, whereas its cytoplasmic domain contains an amphipathic helix.81, 82, 83 In cholesterol- and phosphoethanolamine-rich membranes, this cytoplasmic helix causes membrane curvature,84, 85, 86, 87 which interferes with binding of the antiviral drug amantadine to the TM pore.88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95

The cytoplasmic helix of influenza AM2 does not exhibit any β-sheet tendency, but other virus membrane proteins have been reported to undergo conformational changes in response to membrane curvature or to cause membrane curvature. In the trimeric PIV5 F protein, the C-terminal TM domain adopts an α-helical conformation in phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylglycerol membranes. But in phosphatidylethanolamine membranes, the two termini of the TM domain convert to β-strands.96, 97 These β-strand segments increase the membrane curvature, dehydrate the membrane, and promote membrane fusion. The N-terminal fusion peptides of PIV5 and HIV gp41 also exhibit membrane-dependent conformations.98, 99, 100 In cholesterol-rich lipid bilayers, they adopt β-sheet conformations while in detergents and non-cholesterol membranes they mainly adopt α-helical structures.101, 102 The β-sheet conformation of the HIV gp41 fusion peptide is associated with membrane-curvature generation and sensing.103, 104 For influenza M2, the proton channel activity and tetramerization are accomplished by the TM domain, while the membrane scission function is accomplished by the cytoplasmic domain. The latter contains a curvature-inducing amphipathic helix and a disordered tail.61, 94 The SARS-CoV-2 E protein has various similarities to these viral membrane proteins. Like the PIV5 fusion protein TM domain and the PIV5 and HIV fusion peptides, the E CTD can adopt both helical and sheet conformations depending on its membrane environment. Like M2, E is a homo-oligomeric single-pass TM viroporin, with the CTD containing both a structured portion and a disordered tail. Future studies are required to understand whether it is the α-helical or β-sheet conformation of the E CTD that causes membrane curvature, and if this conformational transition is a sensor or a cause of membrane curvature.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Aurelio J. Dregni: Formal analysis, Validation, Writing – review & editing. Matthew J. McKay: Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. Wahyu Surya: Investigation. Maria Queralt-Martin: Investigation. João Medeiros-Silva: Formal analysis. Harrison K. Wang: Formal analysis. Vicente Aguilella: Investigation, Supervision. Jaume Torres: Investigation, Supervision. Mei Hong: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Acknowledgement

This work is supported by NIH grant GM088204 to M.H. The NMR experiments used equipment at the MIT-Harvard Center for Magnetic Resonance, which is supported by the P41 grant GM132079. A.J.D. was partially supported by an NIH fellowship F31AG069418. J.M.-S. gratefully acknowledges a Rubicon Fellowship 452020132 supported by the Dutch Research Council (NWO). J.T. acknowledges support of Singapore MOE Tier 1 grant RG92/21. M.Q.M. and V.M.A. acknowledge support from the Government of Spain MCIN/AEI/https://doi.org/10.13039/501100011033 (project no. 2019-108434GB-I00 AEI/FEDER, UE and IJC2018-035283-I/AEI) and Universitat Jaume I (project no. UJI-A2020-21).

Edited by Ichio Shimada

Footnotes

Tables of detailed experimental parameters, assigned chemical shifts and internuclear correlations. Additional NMR spectra, structural topologies, and ETR purification results are also provided. Supplementary material to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2023.167966.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary material to this article:

References

- 1.Schoeman D., Fielding B.C. Coronavirus envelope protein: current knowledge. Virol. J. 2019;16:69. doi: 10.1186/s12985-019-1182-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nieto-Torres J.L., DeDiego M.L., Álvarez E., Jiménez-Guardeño J.M., Regla-Nava J.A., Llorente M., et al. Subcellular location and topology of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus envelope protein. Virology. 2011;415:69–82. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2011.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torres J., Maheswari U., Parthasarathy K., Ng L., Liu D.X., Gong X. Conductance and amantadine binding of a pore formed by a lysine-flanked transmembrane domain of SARS coronavirus envelope protein. Protein Sci. 2007;16:2065–2071. doi: 10.1110/ps.062730007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson L., McKinlay C., Gage P., Ewart G. SARS coronavirus E protein forms cation-selective ion channels. Virology. 2004;330:322–331. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nieto-Torres J.L., Verdiá-Báguena C., Jimenez-Guardeño J.M., Regla-Nava J.A., Castaño-Rodriguez C., Fernandez-Delgado R., et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus E protein transports calcium ions and activates the NLRP3 inflammasome. Virology. 2015;485:330–339. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nieto-Torres J.L., DeDiego M.L., Verdia-Baguena C., Jimenez-Guardeno J.M., Regla-Nava J.A., Fernandez-Delgado R., et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus envelope protein ion channel activity promotes virus fitness and pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004077. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verdia-Baguena C., Nieto-Torres J.L., Alcaraz A., Dediego M.L., Enjuanes L., Aguilella V.M. Analysis of SARS-CoV E protein ion channel activity by tuning the protein and lipid charge. BBA. 2013;1828:2026–2031. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verdiá-Báguena C., Nieto-Torres J.L., Alcaraz A., DeDiego M.L., Torres J., Aguilella V.M., et al. Coronavirus E protein forms ion channels with functionally and structurally-involved membrane lipids. Virology. 2012;432:485–494. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parthasarathy K., Ng L., Lin X., Liu D.X., Pervushin K., Gong X., et al. Structural flexibility of the pentameric SARS coronavirus envelope protein ion channel. Biophys. J. 2008;95:L39–L41. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.133041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Y., Surya W., Claudine S., Torres J. Structure of a conserved Golgi complex-targeting signal in coronavirus envelope proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:12535–12549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.560094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parthasarathy K., Lu H., Surya W., Vararattanavech A., Pervushin K., Torres J. Expression and purification of coronavirus envelope proteins using a modified β-barrel construct. Protein Expr. Purif. 2012;85:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Appenzeller-Herzog C., Hauri H.P. The ER-Golgi intermediate compartment (ERGIC): in search of its identity and function. J. Cell Sci. 2006;119:2173–2183. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murakami T., Ockinger J., Yu J., Byles V., McColl A., Hofer A.M., et al. Critical role for calcium mobilization in activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. PNAS. 2012;109:11282–11287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117765109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Somberg N.H., Wu W.W., Medeiros-Silva J., Dregni A.J., Jo H., DeGrado W.F., et al. SARS-CoV-2 Envelope Protein Forms Clustered Pentamers in Lipid Bilayers. Biochemistry. 2022;61:2280–2294. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.2c00464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Surya W., Torres J. Oligomerization-Dependent Beta-Structure Formation in SARS-CoV-2 Envelope Protein. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23:13285. doi: 10.3390/ijms232113285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pervushin K., Tan E., Parthasarathy K., Lin X., Jiang F.L., Yu D., et al. Structure and Inhibition of the SARS Coronavirus Envelope Protein Ion Channel. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Torres J., Parthasarathy K., Lin X., Saravanan R., Kukol A., Liu D.X. Model of a putative pore: the pentameric alpha-helical bundle of SARS coronavirus E protein in lipid bilayers. Biophys. J. 2006;91:938–947. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.080119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mandala V.S., McKay M.J., Shcherbakov A.A., Dregni A.J., Kolocouris A., Hong M. Structure and drug binding of the SARS-CoV-2 envelope protein transmembrane domain in lipid bilayers. Nature Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020;27:1202–1208. doi: 10.1038/s41594-020-00536-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Medeiros-Silva J., Somberg N.H., Wang H.K., McKay M.J., Mandala V.S., Dregni A.J., et al. pH- and Calcium-Dependent Aromatic Network in the SARS-CoV-2 Envelope Protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022;144:6839–6850. doi: 10.1021/jacs.2c00973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Teoh K.T., Siu Y.L., Chan W.L., Schlüter M.A., Liu C.J., Peiris J.S., et al. The SARS coronavirus E protein interacts with PALS1 and alters tight junction formation and epithelial morphogenesis. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2010;21:3838–3852. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-04-0338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jimenez-Guardeño J.M., Regla-Nava J.A., Nieto-Torres J.L., DeDiego M.L., Castaño-Rodriguez C., Fernandez-Delgado R., et al. Identification of the Mechanisms Causing Reversion to Virulence in an Attenuated SARS-CoV for the Design of a Genetically Stable Vaccine. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1005215. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Toto A., Ma S., Malagrinò F., Visconti L., Pagano L., Stromgaard K., et al. Comparing the binding properties of peptides mimicking the Envelope protein of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 to the PDZ domain of the tight junction-associated PALS1 protein. Protein Sci. 2020;29:2038–2042. doi: 10.1002/pro.3936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Javorsky A., Humbert P.O., Kvansakul M. Structural basis of coronavirus E protein interactions with human PALS1 PDZ domain. Commun. Biol. 2021;4:724. doi: 10.1038/s42003-021-02250-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jose R.J., Manuel A. COVID-19 cytokine storm: the interplay between inflammation and coagulation. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020;8:e46–e47. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30216-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng M., Karki R., Williams E.P., Yang D., Fitzpatrick E., Vogel P., et al. TLR2 senses the SARS-CoV-2 envelope protein to produce inflammatory cytokines. Nature Immunol. 2021;22:829–838. doi: 10.1038/s41590-021-00937-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruch T.R., Machamer C.E. The coronavirus E protein: assembly and beyond. Viruses. 2012;4:363–382. doi: 10.3390/v4030363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Regla-Nava J.A., Nieto-Torres J.L., Jimenez-Guardeño J.M., Fernandez-Delgado R., Fett C., Castaño-Rodríguez C., et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronaviruses with mutations in the E protein are attenuated and promising vaccine candidates. J. Virol. 2015;89:3870–3887. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03566-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Surya W., Li Y., Torres J. Structural model of the SARS coronavirus E channel in LMPG micelles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2018;1860:1309–1317. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2018.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park S.H., Siddiqi H., Castro D.V., De Angelis A.A., Oom A.L., Stoneham C.A., et al. Interactions of SARS-CoV-2 envelope protein with amilorides correlate with antiviral activity. PLoS Pathog. 2021;17:e1009519. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Surya W, Samsó M, Torres J. Structural and Functional Aspects of Viroporins in Human Respiratory Viruses: Respiratory Syncytial Virus and Coronaviruses. In: Vats M, editor. Respiratory Disease and Infection – A New Insight2013.

- 31.Ghosh A., Pithadia A.S., Bhat J., Bera S., Midya A., Fierke C.A., et al. Self-Assembly of a Nine-Residue Amyloid-Forming Peptide Fragment of SARS Corona Virus E-Protein: Mechanism of Self Aggregation and Amyloid-Inhibition of hIAPP. Biochemistry. 2015;54:2249–2261. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Savitsky P., Bray J., Cooper C.D., Marsden B.D., Mahajan P., Burgess-Brown N.A., et al. High-throughput production of human proteins for crystallization: the SGC experience. J. Struct. Biol. 2010;172:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Studier F.W. In: Structural Genomics: General Applications. Chen Y.W., editor. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 2014. Stable Expression Clones and Auto-Induction for Protein Production in E. coli; pp. 17–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sivashanmugam A., Murray V., Cui C.X., Zhang Y.H., Wang J.J., Li Q.Q. Practical protocols for production of very high yields of recombinant proteins using Escherichia coli. Protein Sci. 2009;18:936–948. doi: 10.1002/pro.102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bezrukov S.M., Vodyanoy I. Probing alamethicin channels with water-soluble polymers. Effect on conductance of channel states. Biophys. J. 1993;64:16–25. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81336-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Montal M., Mueller P. Formation of bimolecular membranes from lipid monolayers and a study of their electrical properties. PNAS. 1972;69:3561–3566. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.12.3561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Böckmann A., Gardiennet C., Verel R., Hunkeler A., Loquet A., Pintacuda G., et al. Characterization of different water pools in solid-state NMR protein samples. J. Biomol. NMR. 2009;45:319–327. doi: 10.1007/s10858-009-9374-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hou G.J., Yan S., Trebosc J., Amoureux J.P., Polenova T. Broadband homonuclear correlation spectroscopy driven by combined R2(n)(v) sequences under fast magic angle spinning for NMR structural analysis of organic and biological solids. J. Magn. Reson. 2013;232:18–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rienstra C.M., Hohwy M., Hong M., Griffin R.G. 2D and 3D 15N–13C−13C NMR Chemical Shift Correlation Spectroscopy of Solids: Assignment of MAS Spectra of Peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:10979–10990. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baldus M., Petkova A.T., Herzfeld J., Griffin R.G. Cross polarization in the tilted frame: assignment and spectral simplification in heteronuclear spin systems. Mol. Phys. 1998;95:1197–1207. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Williams J.K., Hong M. Probing membrane protein structure using water polarization transfer solid-state NMR. J. Magn. Reson. 2014;247:118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dregni A.J., Duan P., Hong M. Hydration and Dynamics of Full-Length Tau Amyloid Fibrils Investigated by Solid-State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance. Biochemistry. 2020;59:2237–2248. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.0c00342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caravatti P., Braunschweiler L., Ernst R.R. Heteronuclear correlation spectroscopy in rotating solids. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1983;100:305–310. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roberts J.E., Vega S., Griffin R.G. Two-dimensional heteronuclear chemical shift correlation spectroscopy in rotating solids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984;106:2506–2512. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lange A., Luca S., Baldus M. Structural Constraints from Proton-Mediated Rare-Spin Correlation Spectroscopy in Rotating Solids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:9704–9705. doi: 10.1021/ja026691b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goddard TD, Kneller DG. SPARKY 3. University of California, San Francisco.

- 47.Shen Y., Bax A. Protein backbone and sidechain torsion angles predicted from NMR chemical shifts using artificial neural networks. J. Biomol. NMR. 2013;56:227–241. doi: 10.1007/s10858-013-9741-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mandala V.S., Loftis A.R., Shcherbakov A.A., Pentelute B.L., Hong M. Atomic structures of closed and open influenza B M2 proton channel reveal the conduction mechanism. Nature Struct. Mol. Biol. 2020;27:160–167. doi: 10.1038/s41594-019-0371-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Helmus J.J., Jaroniec C.P. Nmrglue: an open source Python package for the analysis of multidimensional NMR data. J. Biomol. NMR. 2013;55:355–367. doi: 10.1007/s10858-013-9718-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schwieters C.D., Kuszewski J.J., Tjandra N., Clore G.M. The Xplor-NIH NMR molecular structure determination package. J. Magn. Reson. 2003;160:65–73. doi: 10.1016/s1090-7807(02)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maciejewski M.W., Schuyler A.D., Gryk M.R., Moraru I.I., Romero P.R., Ulrich E.L., et al. NMRbox: A Resource for Biomolecular NMR Computation. Biophys. J. 2017;112:1529–1534. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huster D., Yao X.L., Hong M. Membrane Protein Topology Probed by 1H Spin Diffusion from Lipids Using Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:874–883. doi: 10.1021/ja017001r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Meer G., Voelker D.R., Feigenson G.W. Membrane lipids: where they are and how they behave. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008;9:112–124. doi: 10.1038/nrm2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stouffer A.L., Ma C., Cristian L., Ohigashi Y., Lamb R.A., Lear J.D., et al. The interplay of functional tuning, drug resistance, and thermodynamic stability in the evolution of the M2 proton channel from the influenza A virus. Structure. 2008:1067–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ghosh A., Bhattacharyya D., Bhunia A. Structural insights of a self-assembling 9-residue peptide from the C-terminal tail of the SARS corona virus E-protein in DPC and SDS micelles: A combined high and low resolution spectroscopic study. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2018;1860:335–346. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2017.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Combet C., Blanchet C., Geourjon C., Deléage G. NPS@: network protein sequence analysis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000;25:147–150. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01540-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Godet M., L'Haridon R., Vautherot J.F., Laude H. TGEV corona virus ORF4 encodes a membrane protein that is incorporated into virions. Virology. 1992;188:666–675. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90521-P. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu D.X., Inglis S.C. Association of the infectious bronchitis virus 3c protein with the virion envelope. Virology. 1991;185:911–917. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90572-S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Boson B., Legros V., Zhou B., Siret E., Mathieu C., Cosset F.L., et al. The SARS-CoV-2 envelope and membrane proteins modulate maturation and retention of the spike protein, allowing assembly of virus-like particles. J. Biol. Chem. 2021;296 doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA120.016175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sharma M., Yi M., Dong H., Qin H., Peterson E., Busath D.D., et al. Insight into the mechanism of the influenza A proton channel from a structure in a lipid bilayer. Science. 2010;330:509–512. doi: 10.1126/science.1191750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rossman J.S., Jing X.H., Leser G.P., Lamb R.A. Influenza Virus M2 Protein Mediates ESCRT-Independent Membrane Scission. Cell. 2010;142:902–913. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Elkins M.R., Williams J.K., Gelenter M.D., Dai P., Kwon B., Sergeyev I.V., et al. Cholesterol-binding site of the influenza M2 protein in lipid bilayers from solid-state NMR. PNAS. 2017;114:12946–12951. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1715127114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Elkins M.R., Sergeyev I.V., Hong M. Determining Cholesterol Binding to Membrane Proteins by Cholesterol 13C Labeling in Yeast and Dynamic Nuclear Polarization NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:15437–15449. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b09658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhang Z., Nomura N., Muramoto Y., Ekimoto T., Uemura T., Liu K., et al. Structure of SARS-CoV-2 membrane protein essential for virus assembly. Nature Commun. 2022;13:4399. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-32019-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dolan K.A., Dutta M., Kern D.M., Kotecha A., Voth G.A., Brohawn S.G. Structure of SARS-CoV-2 M protein in lipid nanodiscs. Elife. 2022;11 doi: 10.7554/eLife.81702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Corse E., Machamer C.E. The cytoplasmic tails of infectious bronchitis virus E and M proteins mediate their interaction. Virology. 2003;312:25–34. doi: 10.1016/S0042-6822(03)00175-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mortola E., Roy P. Efficient assembly and release of SARS coronavirus-like particles by a heterologous expression system. FEBS Lett. 2004;576:174–178. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nieva J.L., Madan V., Carrasco L. Viroporins: structure and biological functions. Nature Rev. Microbiol. 2012;10:563–574. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Park S.H., Mrse A.A., Nevzorov A.A., Mesleh M.F., Oblatt-Montal M., Montal M., et al. Three-dimensional structure of the channel-forming trans-membrane domain of virus protein “u” (Vpu) from HIV-1. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;333:409–424. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.08.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lu J.X., Sharpe S., Ghirlando R., Yau W.M., Tycko R. Oligomerization state and supramolecular structure of the HIV-1 Vpu protein transmembrane segment in phospholipid bilayers. Protein Sci. 2010 doi: 10.1002/pro.474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.OuYang B., Xie S., Berardi M.J., Zhao X., Dev J., Yu W., et al. Unusual architecture of the p7 channel from hepatitis C virus. Nature. 2013;498:521–525. doi: 10.1038/nature12283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hong M., DeGrado W.F. Structural basis for proton conduction and inhibition by the influenza M2 protein. Prot. Sci. 2012;21:1620–1633. doi: 10.1002/pro.2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hu F., Schmidt-Rohr K., Hong M. NMR detection of pH-dependent histidine-water proton exchange reveals the conduction mechanism of a transmembrane proton channel. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:3703–3713. doi: 10.1021/ja2081185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]