Introduction

Multiple clinical, scientific, and authoritative bodies recognize the health impacts of environmental chemical pollution on adverse maternal and child heath outcomes[1-4] Chronic health conditions both in the United States and globally have increased over the last several decades [5], many of which are impacting those who are more susceptible to impacts of toxic chemicals, including pregnant people and children and more highly contaminated populations and communities. Increasing trends in maternal and child health chronic disease conditions include pregnancy related conditions, such as gestational diabetes [6] and childhood diseases, such as neurodevelopmental outcomes (e.g. autism) [7]), metabolic disorders [8], early ages of pubertal onset [9-11], and certain childhood cancers[12]. The increasing prevalence of maternal and child health diseases over a relatively short period of time cannot be due to genetic change, and only a small portion of chronic diseases are due to genetics. Thus fossil fuel related exposures, including petrochemical production and use, has been identified as one potential influence on these trends [3,5,13].

The population is exposed to anthropogenically produced petrochemicals chemicals via air, food, water, and dermal contact. And biomonitoring show that multiple chemicals are measured in humans, including during sensitive life stages [16-18]. Examples of ubiquitously used and measured chemical groups include chemicals in plastic production (e.g. phthalates), flame retardants (e.g. organophosphate flame retardants), phenols (e.g. BPA and parabens), pesticides (e.g. organophosphate pesticides), and stain repellant chemicals (e.g. PFAS). One challenge in characterizing and addressing the extent to which petrochemicals impact maternal and child health is that exposure and health data are not required for many chemicals used on the marketplace in countries like the US; this results in more than 70% of chemicals have no data on exposures or health effects [19,20]. For petrochemicals with sufficient data there are examples of where authoritative or systematic reviews of the evidence find a relationship to maternal and child health outcomes. For example, chemicals in plastic production such as phthalates can increase risk of preterm delivery [21], which is the strongest risk factor for infant mortality [22] and they are known male reproductive developmental toxicants [23]. Another plastic related chemical, BPA, has been identified as a known reproductive toxicant for its effects on the female ovary [24] and authoritative bodies have also linked BPA to multiple other health effects including effects on mammary glands, immune, and metabolic effects [25] Exposure to petrochemical based-fertilizers during pregnancy has also been linked to higher odds of low birthweight, especially among disadvantaged populations [26]. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are linked to several adverse reproductive and developmental disorders [27].

Chronic health conditions also disproportionately affect Black, Brown and Indigenous populations, creating persistent and ongoing health inequities [14,15]. Exposure to anthropogenic chemicals is also a source of health inequities both in the United States and globally [28]. Evidence shows marginalized communities are more likely to live near coal and oil-burning power plants [29] and near freeways and other sources of toxic air pollution [30]. Children who are non-white and lower income face higher exposures both at home [31] and at school [32]. Fossil fuel related chemicals are in some cases at higher in levels in economically marginalized communities [33]– These exposure disparities can contribute to risk maternal and child health inequities in preterm birth, neurodevelopment, among others [5,34,35]. It should be, however, noted that not all exposures are shown to be higher in marginalized communities. Tyrell et al. Observed higher chemical exposures in groups of higher socioeconomic status. While the exact reason behind this trend is unknown, it could be attributed to higher purchasing power. Groups with higher purchasing power could be introducing more consumer products to their indoor environment and thus more chemicals contained in consumer products [36].

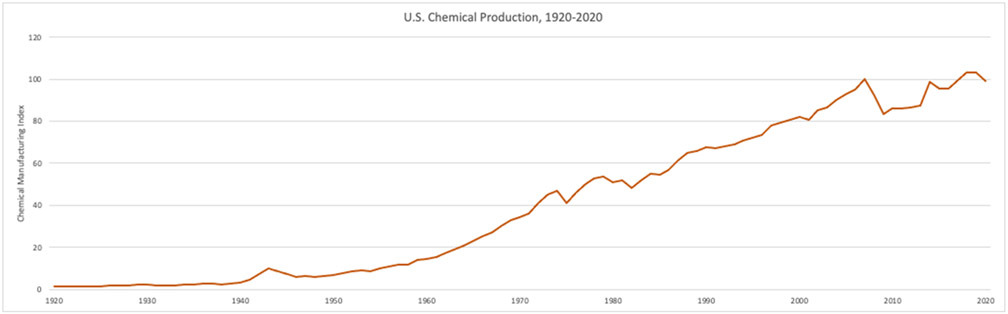

Chemical production has increased in the United States and globally (Figure 1). The U.S. chemical industry is nearly 25% of the nation’s GDP [37], and chemical production has grown significantly between 1920-2020. The U.S. chemical industry is the world’s second largest producer of chemicals, after China, accounting for 13% of the world’s total chemical production. [37].

Figure 1.

US Chemical Production, 1920-2020.

In less than 20 years, between 2000 and 2017, the global chemical industry’s production capacity virtually doubled, from about 1.2 to 2.3 billion tons. Recent projections find this capacity will double again by 2030 with both the production and consumption of chemicals shifting towards emerging and developing economies [38,39]. Projections estimate that China will account for more than half of the world’s chemical production by 2030. The petroleum and chemical industry has taken a major role in the Chinese economy and accounted for 12% of the gross national industrial product in 2017 [40]. Many parts of Africa and the Middle East are also expected to experience high rates of chemical production and consumption in the coming years. Global chemical production is expected to grow at a rate of ~3% a year, outpacing population growth of 1.1% per year [41,42].

The link between fossil fuels and petrochemical production

Fossil fuels, which are the primary driver of climate change and contribution to greenhouse gas emissions and link to climate change [43] are also the principal contributor to petrochemical production, the primary source of chemicals used in products that contaminate air, food and water [43].

Petrochemicals comprise a broad and diverse group of chemical compounds that are isolated from petroleum during the refining process. Some of the most commonly produced petrochemical classes are olefins and aromatics. Olefins (AKA alkenes) are aliphatic hydrocarbons that contain at least one double bond, such as ethene, propene, butene and butadiene. Aromatics are mono- and polycyclic compounds with one or more benzene rings, for example, benzene, toluene, and xylene. Olefins and aromatics are the building blocks of oligomers and polymers that are used in the production of everyday consumer products, such as plastics, fibers, resins, elastomers, lubricants, and gels. Other notable uses for aromatics include dyes, detergents, and polyurethane foams [44].

Fossil fuel production is inextricably linked to plastics production as well as plastics pollution. Approximately 25% of the crude oil produced in North America is used in petrochemical production, primarily ethylene, rather than for transportation fuel [45]. Additionally, fossil fuels, either from oil or gas extraction, make up the feedstock for most of the plastics produced. The most common feedstocks for plastics production are propylene, used to make polypropylene, and ethylene to produce PVC, polyethylene, polystyrene, and polyethylene terephthalate (PET) plastics [46].

The production of ethylene as a feedstock is more lucrative than the sale of methane and ethane for fuel, heat, or electricity [45]. Ethelene production comes primarily from natural gas production and the abundance of cheap shale gas in the U.S. has spurred the investment new plastics manufacturing facilities in the U.S., Europe, and China [46]. The American Chemical Council estimates the construction of 148 projects, totaling over 100 billion, over the next 10 years, to construct facilities to process and produce ethylene [45]. Increased natural gas production in the U.S. has led to increases in the investment and construction of plastics manufacturing plants in the U.S., despite concerns from local communities and global health impacts of increased plastics production and waste [46]. Furthermore, facilities that that produce ethylene and propylene contribute to environmental pollution and increase the potential for adverse health outcomes in surrounding communities. The EPA’s toxic release inventory found that in 2024 and 2015, 28 facilities in Texas released 14 million pounds of pollution to air, land, and water [47].

Single use plastics make up the largest proportion of plastic produced. And 98% of single use plastics are from fossil fuels. In addition, single use plastics contain fossil fuel derived plasticizers (such as phthalates) that are linked to adverse health outcomes and adverse human reproduction and development. The production cycle of plastics, through petrochemical feedstocks, their consumer use as plastics and their degradation in the environment lead to a global problem and a perpetual cycle of EDC exposure and long-term contamination where the health effects and environmental consequences are not well evaluated or regulated.

Conclusion

Fossil fuels are the primary source of petrochemicals, which are increasing in production volume. These chemicals are detected widely in maternal and child populations globally and are risk factors for multiple chronic diseases, many of which are increasing among pregnant people and children and aggravate health inequities, especially among these susceptible populations. Thus, fossil fuels are a twin source of threats to global health through both climate change and hazardous chemical exposures which will more adversely impact maternal and child health and exacerbate health inequities Efforts to reduce fossil fuel use will mitigate exacerbations of maternal and child health inequities due to climate change while also decreasing a source of chemical production, which could contribute to a double benefit to health.

Synopsis:

Fossil fuels contribute to climate change and petrochemicals, which increase disease. Reducing fossil fuels can reap a double benefit for climate change and improved health.

Acknowledgement

We would like to acknowledge the JPB Foundation, the Passport Foundation and UCSF Environmental Research and Translation for Health Center (EaRTH Center, NIH P30ES030284) for supporting this research.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no known conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

There is no research conducted for this paper and thus this section does not apply.

References

- [1].American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Obstetric Practice. Reducing Prenatal Exposure to Toxic Environmental Agents: ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 832. Obstet Gynecol 2021;138:e40–54. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bennett D, Bellinger DC, Birnbaum LS, Bradman A, Chen A, Cory-Slechta DA, et al. Project TENDR: Targeting Environmental Neuro-Developmental Risks The TENDR Consensus Statement. Environ Health Perspect 2016;124:A118–122. 10.1289/EHP358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Di Renzo GC, Conry JA, Blake J, DeFrancesco MS, DeNicola N, Martin JN, et al. International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics opinion on reproductive health impacts of exposure to toxic environmental chemicals. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2015;131:219–25. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Gore AC, Chappell VA, Fenton SE, Flaws JA, Nadal A, Prins GS, et al. Executive Summary to EDC-2: The Endocrine Society’s Second Scientific Statement on Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals. Endocr Rev 2015;36:593–602. 10.1210/er.2015-1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Giudice LC. Environmental impact on reproductive health and risk mitigating strategies. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2021;33:343–9. 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Shah NS, Wang MC, Freaney PM, Perak AM, Carnethon MR, Kandula NR, et al. Trends in Gestational Diabetes at First Live Birth by Race and Ethnicity in the US, 2011-2019. JAMA 2021;326:660–9. 10.1001/jama.2021.7217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Maenner MJ. Prevalence and Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years — Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2018. MMWR Surveill Summ 2021;70. 10.15585/mmwr.ss7011a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].US EPA O. ACE: Health - Obesity 2015. https://www.epa.gov/americaschildrenenvironment/ace-health-obesity (accessed April 18, 2022).

- [9].Biro FM, Greenspan LC, Galvez MP. Puberty in girls of the 21st century. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2012;25:289–94. 10.1016/j.jpag.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Brix N, Ernst A, Lauridsen LLB, Parner E, Støvring H, Olsen J, et al. Timing of puberty in boys and girls: A population-based study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2019;33:70–8. 10.1111/ppe.12507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Leone T, Brown LJ. Timing and determinants of age at menarche in low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health 2020;5:e003689. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].US EPA O. ACE: Health - Childhood Cancer 2015. https://www.epa.gov/americaschildrenenvironment/ace-health-childhood-cancer (accessed April 18, 2022).

- [13].O’Rourke D, Connolly S. Just Oil? The Distribution of Environmental and Social Impacts of Oil Production and Consumption. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 2003;28:587–617. 10.1146/annurev.energy.28.050302.105617. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Cunningham TJ, Croft JB, Liu Y, Lu H, Eke PI, Giles WH. Vital Signs: Racial Disparities in Age-Specific Mortality Among Blacks or African Americans - United States, 1999-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66:444–56. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6617e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Williams DR. Miles to go before we sleep: racial inequities in health. J Health Soc Behav 2012;53:279–95. 10.1177/0022146512455804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Woodruff TJ, Zota AR, Schwartz JM. Environmental chemicals in pregnant women in the United States: NHANES 2003-2004. Environ Health Perspect 2011;119:878–85. 10.1289/ehp.1002727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wang A, Padula A, Sirota M, Woodruff TJ. Environmental influences on reproductive health: the importance of chemical exposures. Fertil Steril 2016;106:905–29. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.07.1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Buckley JP, Kuiper JR, Bennett DH, Barrett ES, Bastain T, Breton CV, et al. Exposure to Contemporary and Emerging Chemicals in Commerce among Pregnant Women in the United States: The Environmental influences on Child Health Outcome (ECHO) Program. Environ Sci Technol 2022;56:6560–73. 10.1021/acs.est.1c08942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Judson R. ToxValDB: Compiling Publicly Available In Vivo Toxicity Data 2019. 10.23645/epacomptox.7800653.v1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Program NRC (U S) SC on I of T and PTC for C by the NT. Toxicity testing: strategies to determine needs and priorities. Washington, D.C: National Academy Press; 1984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Welch BM, Keil AP, Buckley JP, Calafat AM, Christenbury KE, Engel SM, et al. Associations Between Prenatal Urinary Biomarkers of Phthalate Exposure and Preterm Birth: A Pooled Study of 16 US Cohorts. JAMA Pediatr 2022. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.2252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Ely DM, Driscoll AK. Infant Mortality in the United States, 2017: Data From the Period Linked Birth/Infant Death File. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2019;68:1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Radke EG, Braun JM, Meeker JD, Cooper GS. Phthalate exposure and male reproductive outcomes: A systematic review of the human epidemiological evidence. Environ Int 2018;121:764–93. 10.1016/j.envint.2018.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Monserrat L. Bisphenol A (BPA). OEHHA; 2015. https://oehha.ca.gov/proposition-65/chemicals/bisphenol-bpa (accessed August 5, 2022). [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bisphenol A ∣ EFSA; n.d. https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/topics/topic/bisphenol (accessed August 4, 2022). [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lin S, Li J, Wu J, Yang F, Pei L, Shang X. Interactive effects of maternal exposure to chemical fertilizer and socio-economic status on the risk of low birth weight. BMC Public Health 2022;22:1206. 10.1186/s12889-022-13604-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Drwal E, Rak A, Gregoraszczuk EL. Review: Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)-Action on placental function and health risks in future life of newborns. Toxicology 2019;411:133–42. 10.1016/j.tox.2018.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Perera F. Pollution from Fossil-Fuel Combustion is the Leading Environmental Threat to Global Pediatric Health and Equity: Solutions Exist. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017;15:E16. 10.3390/ijerph15010016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Faber DR, Krieg EJ. Unequal exposure to ecological hazards: environmental injustices in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Environ Health Perspect 2002;110 Suppl 2:277–88. 10.1289/ehp.02110s2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Hajat A, Hsia C, O’Neill MS. Socioeconomic Disparities and Air Pollution Exposure: a Global Review. Curr Environ Health Rep 2015;2:440–50. 10.1007/s40572-015-0069-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Chakraborty J, Zandbergen PA. Children at risk: measuring racial/ethnic disparities in potential exposure to air pollution at school and home. J Epidemiol Community Health 2007;61:1074–9. 10.1136/jech.2006.054130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Grineski SE, Collins TW. Geographic and social disparities in exposure to air neurotoxicants at U.S. public schools. Environ Res 2018;161:580–7. 10.1016/j.envres.2017.11.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Nguyen VK, Kahana A, Heidt J, Polemi K, Kvasnicka J, Jolliet O, et al. A comprehensive analysis of racial disparities in chemical biomarker concentrations in United States women, 1999–2014. Environment International 2020;137:105496. 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Clifford A, Lang L, Chen R, Anstey KJ, Seaton A. Exposure to air pollution and cognitive functioning across the life course--A systematic literature review. Environ Res 2016;147:383–98. 10.1016/j.envres.2016.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Klepac P, Locatelli I, Korošec S, Künzli N, Kukec A. Ambient air pollution and pregnancy outcomes: A comprehensive review and identification of environmental public health challenges. Environ Res 2018;167:144–59. 10.1016/j.envres.2018.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Tyrrell J, Melzer D, Henley W, Galloway TS, Osborne NJ. Associations between socioeconomic status and environmental toxicant concentrations in adults in the USA: NHANES 2001-2010. Environ Int 2013;59:328–35. 10.1016/j.envint.2013.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].American Chemistry Council. Guide to the Business of Chemistry. American Chemistry Council; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- [38].OECD. Global Material Resources Outlook to 2060: Economic Drivers and Environmental Consequences. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [39].United Nations Environment Programme. From Legacies to Innovative Solutions: Implementing the 2013 Agenda for Sustainable Development- Synthesis Report. United Nations Enviornment Programme; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [40].Wang B, Wu C, Reniers G, Huang L, Kang L, Zhang L. The future of hazardous chemical safety in China: Opportunities, problems, challenges and tasks. Sci Total Environ 2018;643:1–11. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.06.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Wilson MP, Schwarzman MR. Toward a new U.S. chemicals policy: rebuilding the foundation to advance new science, green chemistry, and environmental health. Environ Health Perspect 2009;117:1202–9. 10.1289/ehp.0800404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Population growth (annual %) ∣ Data n.d. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.GROW (accessed April 18, 2022).

- [43].IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change 2021. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg3/ (accessed April 18, 2022).

- [44].Speight JG, editor. Title page. The Refinery of the Future (Second Edition), Gulf Professional Publishing; 2020, p. i–iii. 10.1016/B978-0-12-816994-0.00016-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Yadav VG, Yadav GD, Patankar SC. The production of fuels and chemicals in the new world: critical analysis of the choice between crude oil and biomass vis-à-vis sustainability and the environment. Clean Techn Environ Policy 2020;22:1757–74. 10.1007/s10098-020-01945-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Center for Environmental Law. How Fracked Gas, Cheap Oil, and Unburnable Coal are Driving the Plastics boom. Center for Environmental Law; n.d. [Google Scholar]

- [47].Food and Water Watch. How Fracking Supports the Plastic Industry. Food and Water Watch; 2017. [Google Scholar]