Abstract

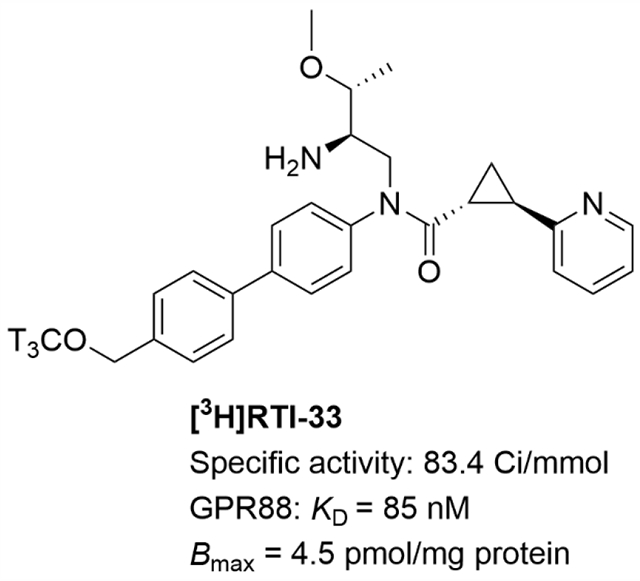

GPR88 is an orphan G protein-coupled receptor which has been implicated in a number of striatal-associated disorders. Herein we describe the synthesis and pharmacological characterization of the first GPR88 radioligand, [3H]RTI-33, derived from a synthetic agonist RTI-13951-33. [3H]RTI-33 has a specific activity of 83.4 Ci/mmol and showed one-site, saturable binding (KD of 85 nM) in membranes prepared from stable PPLS-HA-hGPR88-CHO cells. A competition binding assay was developed to determine binding affinities of several known GPR88 agonists. This radioligand represents a powerful tool for future mechanistic and cell-based ligand-receptor interaction studies of GPR88.

Keywords: GPR88, [3H]RTI-33, Radioligand binding

Graphical Abstract

GPR88 is a Gαi/o-coupled orphan G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) that has robust expression in both striatonigral and striatopallidal pathways of the striatum.1-3 Studies in both animals and humans support the premise that GPR88 is a novel drug target for the treatment of several central nervous system (CNS) disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia, drug addiction, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). A number of studies using GPR88 knockout (KO) mice demonstrated that genetic ablation of GPR88 induced a state of hypersensitivity to the dopamine system and produced multiple behavioral phenotypes including disrupted prepulse inhibition of startle response, motor hyperactivity, poor motor coordination and balance, improved spatial learning, and low anxiety.4-10 Recent studies also demonstrated that GPR88 KO mice had increased alcohol drinking and seeking behaviors and showed higher motor impulsivity and reduced attention, which link GPR88 to the risk of alcoholism and ADHD.11, 12 Moreover, human genetic studies have found positive association between the Gpr88 gene and several psychiatric disorders including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, childhood speech delay, learning disabilities, and chorea.13, 14 Given the potential therapeutic applications of GPR88, elucidating the signaling mechanisms, pharmacology and function of the receptor are of importance for both basic orphan GPCR research and drug discovery. In this regard, radioligand binding is a gold standard method but is currently unavailable for GPR88 research.

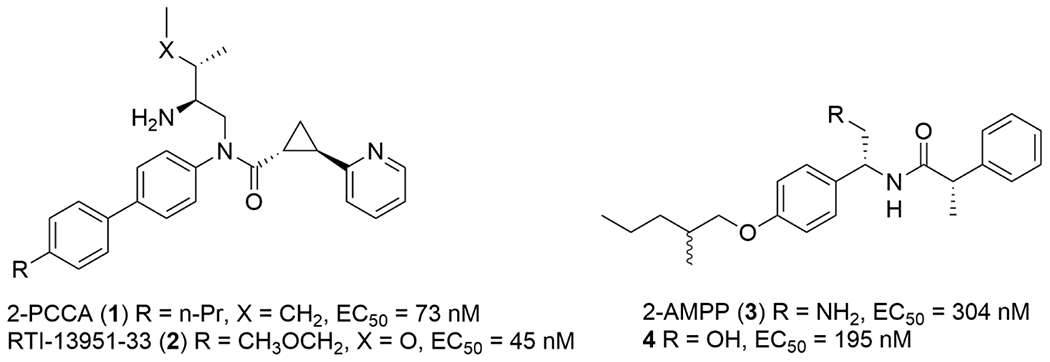

To date, the endogenous ligand for GPR88 has not been discovered. In order to characterize GPR88 signaling mechanisms and biological functions, our laboratory, as well as others, has carried out a medicinal chemistry campaign to develop GPR88 synthetic agonists.15-24 These agonists are mainly based on two scaffolds: 2-PCCA [(1R,2R)-2-(pyridin-2-yl)cyclopropane carboxylic acid ((2S,3S)-2-amino-3-methylpentyl)-(4’-propylbiphenyl-4-yl)amide (1)] and 2-AMPP [(2S)-N-((1R)-2-amino-1-(4-(2-methylpentyloxy)-phenyl)ethyl)-2-phenylpropanamide (3), Figure 1]. We recently developed a potent, selective, and brain-penetrant GPR88 agonist, RTI-13951-33 (2), that we deemed suitable for radiolabeling to study ligand-receptor interactions due to its high specific binding for the target receptor and low non-specific binding to other endogenous binding sites. RTI-13951-33 had an EC50 of 45 nM in an in vitro cAMP functional assay and significantly increased [35S]GTPγS binding (EC50 = 535 nM) in mouse striatal membranes but not in membranes from GPR88 KO mice even at a concentration of 100 μM, indicating the compound has GPR88-specific agonist signaling activity in the striatum.21 In addition, the compound had no significant binding affinities at over 60 CNS targets, including GPCRs, ion channels, and neurotransmitter transporters when screened at Eurofins Panlabs21 and the NIMH Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (Supporting Information Table 1). RTI-13951-33 is highly water-soluble, has a low lipophilicity (clogP 3.34) suggesting the potential for low non-specific binding, and can penetrate into the brain in the pharmacokinetic studies.21 Notably, RTI-13951-33 significantly reduced alcohol intake and preference in wild-type mice but not in GPR88 KO mice, suggesting a specific GPR88-mediated effect on alcohol drinking.25 Collectively, the favorable physiochemical properties and pharmacology profile make RTI-13951-33 a suitable ligand for radiolabeling and receptor binding studies of GPR88. Herein, we describe the synthesis and pharmacological validation of the first radioligand for GPR88, [3H]RTI-33, derived from RTI-13951-33.

Figure 1.

Selected GPR88 agonists.

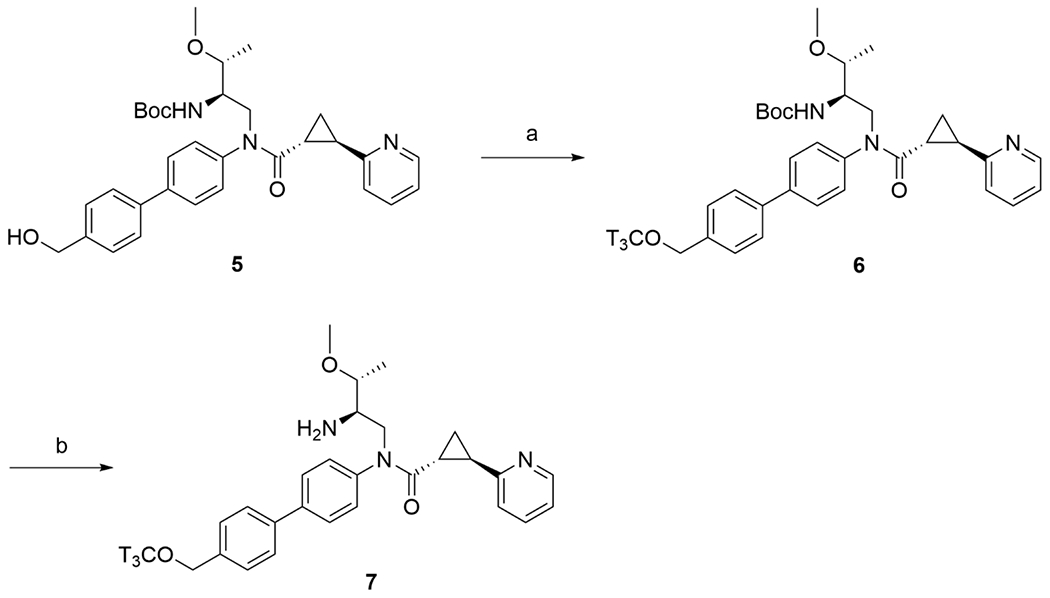

[3H]RTI-33 (7) was prepared following the procedure depicted in Scheme 1. Alcohol 518, 21 was treated with sodium hexamethyldisilazide (NaHMDS) in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) solution to generate the alkoxide anion. Commercially-available tritium-labelled methyl nosylate ([3HMeONs]) was concentrated from the supplied ethyl acetate and hexane solution, then reconstituted as a solution in DMF and transferred into the 5 alkoxide solution. The room temperature reaction was monitored by HPLC with radioactivity flow-monitoring until the reaction was complete. The intermediate 6 was purified by preparative HPLC, then stored as a solution in ethanol until needed. To afford the desired 7, a sample of the ethanol solution of 6 was evaporated under a stream of nitrogen then treated with hydrogen chloride in methanol. The methanol solution was similarly evaporated. The sample was reconstituted in ethanol solution to give [3H]RTI-33 (7) with a radiochemical purity of 98% and specific activity of 83.4 Ci/mmol.

Scheme 1.

Reagents and conditions: (a) NaHMDS, [3H]methyl nosylate, DMF, rt; (b) HCl, CH3OH, rt.

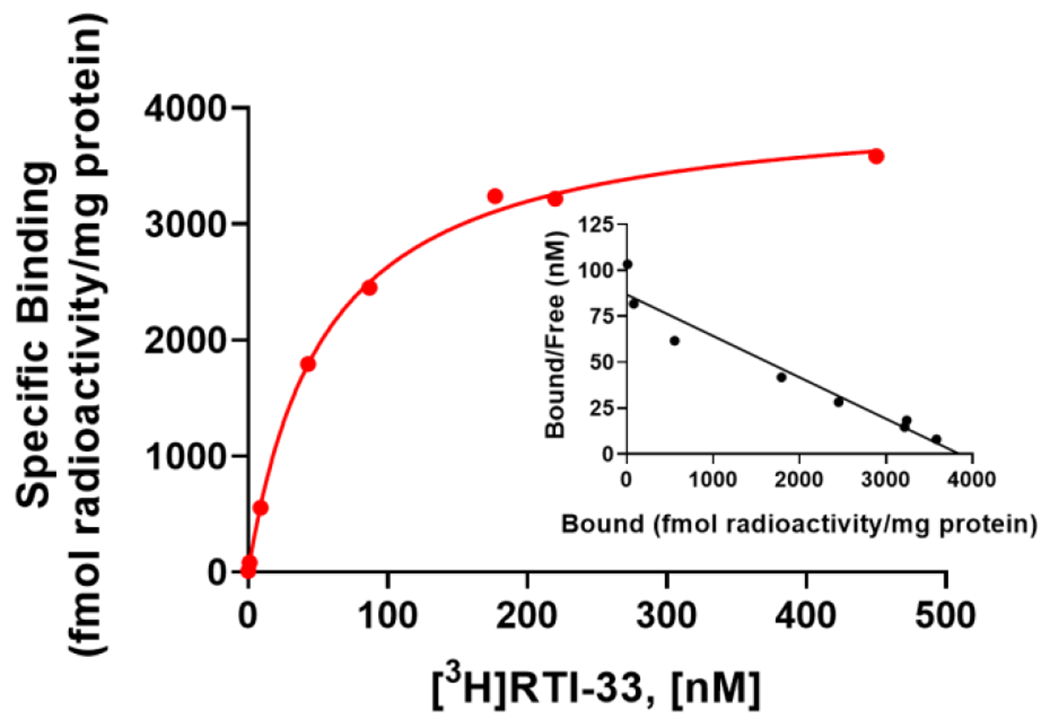

We characterized the synthesized [3H]RTI-33 to establish a pharmacological binding profile26 by carrying out saturation and competition binding studies using membranes prepared from our stable PPLS-HA-hGPR88-CHO cells, which have been used to characterize GPR88 ligands in cAMP assays.18, 20-23 Saturation binding studies were used to determine the affinity (KD) of the radioligand, as well as the binding site density (Bmax) using filtration-based methods. In this assay, 8 different radioligand concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 450 nM were tested in the presence of vehicle (total binding) or 10 μM RTI-13951-33 (non-specific binding, NSB). One-site specific [3H]RTI-33 binding was observed with KD = 85 nM and Bmax = 4.5 pmol/mg protein (Figure 2). The in vitro cAMP EC50 value of unlabeled RTI-13951-33 is 45 nM, which compares well with the KD of 85 nM.

Figure 2.

Saturation curve for one-site specific [3H]RTI-33 binding to PPLS-HA-hGPR88-CHO membranes using filtration methods. Data points are the means ± SEM of three independent experiments, each performed with duplicate determinations. Inset: Scatchard plot of the same data.

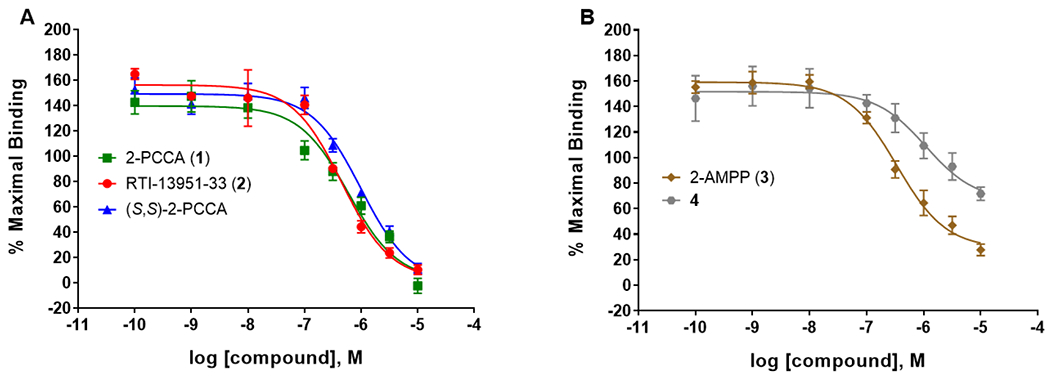

Next, we performed competition binding studies using analogs from both the 2-PCCA15, 18, 21 and 2-AMPP20 scaffold families to characterize the ligand recognition properties of the radioligand binding site and to determine whether the binding affinity (Ki) correlates with the functional activity (Figure 3). Three analogs are from the 2-PCCA family [2-PCCA (1), (S,S)-2-PCCA, and RTI-13951-33 (2)] and two analogs are from the 2-AMPP family [2-AMPP (3) and 4, Figure 1]. These assays were run with 70 nM of [3H]RTI-33 because the NSB at this concentration amounted to 41% of the total binding and was thus in a tolerable range.27, 28 Compound Ki values are presented in Table 1 along with the in vitro functional cAMP EC50 values. The Ki/EC50 ratio was calculated to track the difference between binding affinity and functional activity.

Figure 3.

Competition binding of selected GPR88 agonists with [3H]RTI-33 in PPLS-HA-hGPR88-CHO membranes using filtration methods. Data points are the means ± SEM of three independent experiments, each performed with duplicate determinations. (A) Competition binding of RTI-13951-33, 2-PCCA, and (S,S)-2-PCCA. (B) Competition binding of 2-AMPP and compound 4.

Table 1.

Comparison of binding affinities and in vitro functional EC50 values for GPR88 agonists.

| Compound | cAMP EC50 (nM) | Ki (nM)a | Ki/EC50 Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| RTI-13951-33 (2) | 45 | 224 ± 36 | 5.0 |

| 2-PCCA (1) | 74 | 277 ± 39 | 3.7 |

| (S,S)-2-PCCA | 1738 | 487 ± 46 | 0.3 |

| 2-AMPP (3) | 304 | 219 ± 54 | 0.7 |

| 4 | 195 | 612 ± 86 | 3.1 |

Ki values are the means ± SEM of at least three independent experiments, each performed with duplicate determinations.

Unlabeled RTI-13951-33 has a binding affinity of 224 nM, a functional potency of 45 nM, and a Ki/EC50 ratio of 5.0. Compared to RTI-13951-33, 2-PCCA has a 1.2-fold lower affinity (Ki = 277 nM), a 1.6-fold lower functional potency (EC50 = 74 nM), and a slightly smaller Ki/EC50 ratio of 3.7. Surprisingly, although the (S,S)-isomer of 2-PCCA (EC50 = 1738 nM) is 23-fold less potent than 2-PCCA (EC50 = 74 nM), it has a moderate binding affinity (Ki of 487 nM) at GPR88. This suggests that the compound has a stronger affinity for the GPR88 receptor compared to its ability to functionally activate the receptor. Note: the (R,R)-isomer and (S,S)-isomer are differentiated only at two chiral centers of the cyclopropane ring, whereas the side chains in both isomers are derived from L-isoleucine (Figure 1). In general, the rank order of the binding affinities of 2-PCCA analogs is consistent with that of EC50 values in the functional cAMP assay. Two compounds from the 2-AMPP series were also examined. 2-AMPP has a Ki = 219 nM, which is similar to its cAMP potency (EC50 = 304 nM). On the other hand, compound 4 has a Ki = 612 nM, which is 3.1-fold lower that its functional potency. Overall, these results indicate that all functional GPR88 agonists tested in this study were able to displace [3H]RTI-33 in a competitive manner. These results also validate our radioligand for use in determining binding affinities of potential GPR88 ligands. Recently, a cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structure of GPR88 in complex with 2-PCCA was reported.29 Interestingly, 2-PCCA is an allosteric agonist binding to a pocket formed by transmembrane segments 5, 6 and the C terminus of the α5 helix of the Gi1 protein. [3H]RTI-33 radioligand binding, in combination with site-directed mutagenesis studies, will further our understanding of the GPR88 ligand binding sites and possibly mechanisms of activation of this novel receptor.

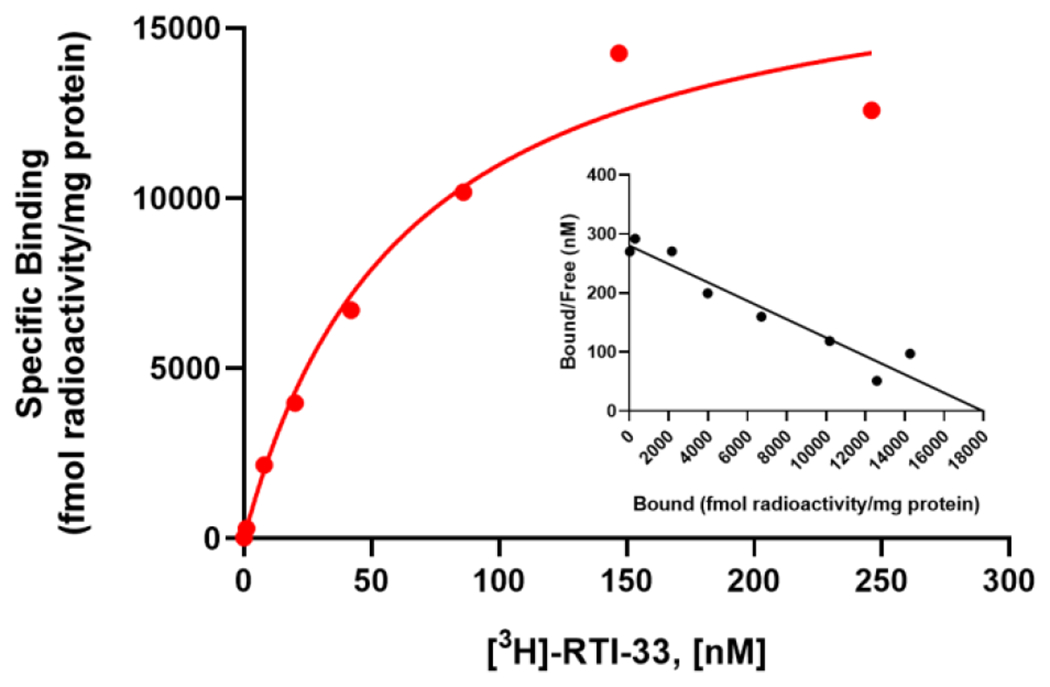

Finally, we determined the affinity (KD) of the radioligand, as well as the binding site density (Bmax) in native tissue by performing saturation binding in striatal membranes prepared from wild-type mice.21 In this assay, 8 different radioligand concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 250 nM were tested in the presence of vehicle (total binding) or 10 μM RTI-13951-33 (NSB). One-site specific [3H]RTI-33 binding was observed with KD = 41 nM and Bmax = 15 pmol/mg protein (Figure 4). The KD of [3H]RTI-33 in mouse striatal membranes also compares very well with the in vitro cAMP EC50 of unlabeled RTI-13951-33 (45 nM) and is 2-fold more potent than the KD obtained in the PPLS-HA-hGPR88-CHO membranes (85 nM). Similarly, the Bmax in native tissue is 3-fold higher compared to the Bmax in the PPLS-HA-hGPR88-CHO membranes (4.5 pmol/mg protein). The favorable KD and Bmax values in native tissue indicate the versatility of the [3H]RTI-33 radioligand to study GPR88 ligand-receptor interactions in native as well as recombinant systems.

Figure 4.

Saturation curve for one-site specific [3H]RTI-33 binding to wild-type mouse striatal membranes using filtration methods. Data points are the means ± SEM of three independent experiments, each performed with duplicate determinations. Inset: Scatchard plot of the same data.

In conclusion, we have developed the first radioligand for the orphan receptor GPR88 and characterized its binding properties through saturation and competition binding studies. [3H]RTI-33 can be easily prepared with a radiochemical purity of 98% and specific activity of 83.4 Ci/mmol through a 2-step procedure. [3H]RTI-33 has a high affinity for the GPR88 receptor in recombinant membrane preparations and native mouse striatal tissue. Competition binding with a selection of 2-PCCA and 2-AMPP analogs revealed that GPR88 functional agonists were able to competitively displace [3H]RTI-33. This new GPR88 radioligand represents a powerful tool to study GPR88 receptor-ligand interactions and for the discovery of novel GPR88 ligands.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

[3H]RTI-33 is the first radioligand for the GPR88 receptor.

[3H]RTI-33 has high affinity for GPR88 in PPLS-HA-hGPR88-CHO membranes.

GPR88 functional agonists competitively displace [3H]RTI-33.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA, grants R01AA026820 to C.J. and B.L.K. and R03AA029013 to C.J. and D.H.), National Institutes of Health, USA.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data (including off-target profile of RTI-13951-33, chemistry experimental procedures, and radioligand binding methods) to this article can be found online at [location TBD].

Data availability

Data is available upon request.

References

- 1.Mizushima K, Miyamoto Y, Tsukahara F, Hirai M, Sakaki Y, Ito T. A novel G-protein-coupled receptor gene expressed in striatum. Genomics. 2000;69(3): 314–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Massart R, Guilloux JP, Mignon V, Sokoloff P, Diaz J. Striatal GPR88 expression is confined to the whole projection neuron population and is regulated by dopaminergic and glutamatergic afferents. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30(3): 397–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Waes V, Tseng KY, Steiner H. GPR88 - a putative signaling molecule predominantly expressed in the striatum: Cellular localization and developmental regulation. Basal Ganglia. 2011;1(2): 83–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Logue SF, Grauer SM, Paulsen J, et al. The orphan GPCR, GPR88, modulates function of the striatal dopamine system: a possible therapeutic target for psychiatric disorders? Mol Cell Neurosci. 2009;42(4): 438–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quintana A, Sanz E, Wang W, et al. Lack of GPR88 enhances medium spiny neuron activity and alters motor- and cue-dependent behaviors. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(11): 1547–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meirsman AC, Le Merrer J, Pellissier LP, et al. Mice lacking GPR88 show motor deficit, improved spatial learning, and low anxiety reversed by delta opioid antagonist. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(11): 917–927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meirsman AC, Robe A, de Kerchove d’Exaerde A, Kieffer BL. GPR88 in A2AR neurons enhances anxiety-like behaviors. eNeuro. 2016;3(4): 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meirsman AC, Ben Hamida S, Clarke E, de Kerchove d’Exaerde A, Darcq E, Kieffer BL. GPR88 in D1R-type and D2R-type medium spiny neurons differentially regulates affective and motor behavior. eNeuro. 2019;6(4): 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mantas I, Yang Y, Mannoury-la-Cour C, Millan MJ, Zhang X, Svenningsson P. Genetic deletion of GPR88 enhances the locomotor response to L-DOPA in experimental parkinsonism while counteracting the induction of dyskinesia. Neuropharmacology. 2020;162: 107829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomson DM, Openshaw RL, Mitchell EJ, et al. Impaired working memory, cognitive flexibility and reward processing in mice genetically lacking Gpr88: Evidence for a key role for Gpr88 in multiple cortico-striatal-thalamic circuits. Genes Brain Behav. 2021;20(2): e12710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ben Hamida S, Mendonca-Netto S, Arefin TM, et al. Increased alcohol seeking in mice lacking Gpr88 involves dysfunctional mesocorticolimbic networks. Biol Psychiatry. 2018;84(3): 202–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ben Hamida S, Sengupta SM, Clarke E, et al. The orphan receptor GPR88 controls impulsivity and is a risk factor for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2022; doi: 10.1038/s41380-022-01738-w. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Del Zompo M, Deleuze JF, Chillotti C, et al. Association study in three different populations between the GPR88 gene and major psychoses. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2014;2(2): 152–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alkufri F, Shaag A, Abu-Libdeh B, Elpeleg O. Deleterious mutation in GPR88 is associated with chorea, speech delay, and learning disabilities. Neurol Genet. 2016;2(3): e64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jin C, Decker AM, Huang XP, et al. Synthesis, pharmacological characterization, and structure-activity relationship studies of small molecular agonists for the orphan GPR88 receptor. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2014;5(7): 576–587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bi Y, Dzierba CD, Fink C, et al. The discovery of potent agonists for GPR88, an orphan GPCR, for the potential treatment of CNS disorders. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2015;25(7): 1443–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dzierba CD, Bi Y, Dasgupta B, et al. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of phenylglycinols and phenyl amines as agonists of GPR88. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2015;25(7): 1448–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jin C, Decker AM, Harris DL, Blough BE. Effect of substitution on the aniline moiety of the GPR88 agonist 2-PCCA: Synthesis, structure-activity relationships, and molecular modeling studies. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2016;7(10): 1418–1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Decker AM, Gay EA, Mathews KM, et al. Development and validation of a high-throughput calcium mobilization assay for the orphan receptor GPR88. J Biomed Sci. 2017;24(1): 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jin C, Decker AM, Langston TL. Design, synthesis and pharmacological evaluation of 4-hydroxyphenylglycine and 4-hydroxyphenylglycinol derivatives as GPR88 agonists. Bioorg Med Chem. 2017;25(2): 805–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jin C, Decker AM, Makhijani VH, et al. Discovery of a potent, selective, and brain-penetrant small molecule that activates the orphan receptor GPR88 and reduces alcohol intake. J Med Chem. 2018;61(15): 6748–6758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rahman MT, Decker AM, Langston TL, et al. Design, synthesis, and structure-activity relationship studies of (4-alkoxyphenyl)glycinamides and bioisosteric 1,3,4-oxadiazoles as GPR88 agonists. J Med Chem. 2020;63(23): 14989–15012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rahman MT, Decker AM, Laudermilk L, et al. Evaluation of amide bioisosteres leading to 1,2,3-triazole containing compounds as GPR88 agonists: Design, synthesis, and structure-activity relationship studies. J Med Chem. 2021;64(16): 12397–12413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quibell M, Schulz-Utermoehl T, Murray F, Pichowicz M. Modulators of G protein-coupled receptor 88. WO 2022/129933 A1, June 12, 2022.

- 25.Ben Hamida S, Carter M, Darcq E, et al. The GPR88 agonist RTI-13951-33 reduces alcohol drinking and seeking in mice. Addict Biol. 2022;27: e13227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bylund DB, Toews ML. Radioligand binding methods for membrane preparations and intact cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;746: 135–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kose M, Ritter K, Thiemke K, Gillard M, Kostenis E, Muller CE. Development of [(3)H]2-carboxy-4,6-dichloro-1H-indole-3-propionic acid ([(3)H]PSB-12150): A useful tool for studying GPR17. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2014;5(4): 326–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hulme EC, Trevethick MA. Ligand binding assays at equilibrium: validation and interpretation. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;161(6): 1219–1237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen G, Xu J, Inoue A, et al. Activation and allosteric regulation of the orphan GPR88-Gi1 signaling complex. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1): 2375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data is available upon request.