Abstract

Bisphenol A (BPA) is a common environmental chemical with a range of potential adverse health effects. The impact of environmentally-relevant low dose of BPA on the electrical properties of the hearts of large animals (e.g., dog, human) is poorly defined. Perturbation of cardiac electrical properties is a key arrhythmogenic mechanism. In particular, delay of ventricular repolarization and prolongation of the QT interval of the electrocardiogram is a marker for the risk of malignant arrhythmias. We examined the acute effect of 10−9 M BPA on the electrical properties of female canine ventricular myocytes and tissues. BPA rapidly delayed action potential repolarization and prolonged action potential duration (APD). The dose response curve of BPA on APD was nonmonotonic. BPA rapidly inhibited the IKr K+ current and ICaL Ca2+ current. Computational modeling indicated that the effect of BPA on APD can be accounted for by its suppression of IKr. At the tissue level, BPA acutely prolonged the QT interval in 4 left ventricular wedges. ERβ signaling contributed to the acute effects of BPA on ventricular repolarization. Our results demonstrate that BPA has QT prolongation liability in female canine hearts. These findings have implication for the potential proarrhythmic cardiac toxicity of BPA in large animals.

Keywords: Bisphenol A, Canine heart, Low dose, hERG channel, QT prolongation, arrhythmia marker

INTRODUCTION

Bisphenol A (BPA) is a synthetic chemical that is used extensively in the manufacturing of plastic products. The presence of BPA in the environment is near ubiquitous and there is wide human exposure to BPA through diet, inhalation, dermal and other exposure routes (Calafat et al., 2008; Geens et al., 2012; Vandenberg et al., 2007). The geometric mean of urinary BPA concentration in the US population is in the low μg/L, or low nM, range (CDC, 2017). As an estrogenic endocrine disrupting chemical (EDC), BPA has a range of potentially adverse impacts on human health (Catenza et al., 2021; Diamanti-Kandarakis et al., 2009; Gore et al., 2015). BPA has been demonstrated to affect multiple systems. For example, in vivo studies in mice showed that BPA exposure resulted in impairment of immune function and increased susceptibility to infection and autoimmune disease (Malaisé et al., 2020; Park et al., 2021; Predieri et al., 2020; Rogers et al., 2017; Win-Shwe et al., 2021). Growing evidence suggests that BPA may have adverse impacts on the cardiovascular system. Multiple epidemiological studies demonstrate that higher BPA exposure is associated with cardiovascular diseases or cardiovascular disease risk factors in humans (Cai et al., 2020; Fu et al., 2020; Gao and Wang, 2014; Moon et al., 2021). Experimental studies shown that BPA exposure in rodents results in cardiac remodeling, alteration of cardiac function, oxidative stress, and altered autonomic regulation (Aboul Ezz et al., 2015; Belcher et al., 2015; Cooper and Posnack, 2022; Dias et al., 2022; Nagarajan et al., 2021; Patel et al., 2013). In large animals, maternal BPA exposure has been shown to cause changes in expression of genes related to cardiovascular pathology in rhesus monkeys (Chapalamadugu et al., 2014), and both prenatal and postnatal exposures to BPA have been shown to result in transcriptional changes in the heart in sheep (Koneva et al., 2017).

BPA has been shown to disrupt cardiac ion channels and electrophysiology, and promote arrhythmia in the heart. Acute exposure to 10-100 μM BPA impaired electrical conduction in isolated rat hearts, resulting in delay of atrioventricular conduction and decreased ventricular conduction velocity (Posnack et al., 2014). Such BPA-induced electric perturbations may be attributable to its alterations of key cardiac ion channels as BPA at micromolar range was found to inhibit cardiac ion channels including the L-type Ca2+ channel (ICaL), the sodium channel (INa) and the rapid delayed rectifier K+ channel (IKr) expressed in HEK cells (Prudencio et al., 2021). In human-induced pluripotent stem cell derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CMs), 1-100 μM BPA reduced field potential duration and amplitude, and dose-dependently inhibited ICa, INa or IKr channels (Hyun et al., 2021). In Zebrafish, exposure to BPA at 250 μg/L reduced the heart rate (Moreman et al., 2018). In past studies, we showed that environmentally-relevant low dose (nM range) BPA acutely altered Ca2+ handling in rodent cardiac myocytes, and promoted the development of arrhythmia in rodent hearts (Gao et al., 2013; Yan et al., 2011; Yan et al., 2013).

A notable gap in the current knowledge of the cardiac toxicity of BPA is its impact on the electrical properties of the hearts of large animals. Mammalian species share similar general cardiac physiology. However, due to the demands imposed by different body size, the hearts of large animals (eg, human, dog, pig) and small animals (eg, rodents) have distinct properties and, consequently, unique arrhythmogenic mechanisms. Hearts of large animals have slower heart rates and broad action potentials (APs) with a characteristic “spike and dome” morphology (Rosati et al., 2008). A prominent arrhythmogenic mechanism in large animals, including humans, is delay of ventricular repolarization (Pogwizd and Bers, 2004). Since the QT interval of the electrocardiogram (EKG) is a measurement of the duration of ventricular excitation, ventricular repolarization delay manifests as QT prolongation (Kramer and Zimetbaum, 2011). Excessive delay of ventricular action potential repolarization can lead to ectopic excitations of the ventricular myocytes, malignant ventricular tachycardiac, and sudden cardiac death (Goldenberg et al., 2008; Kramer and Zimetbaum, 2011). Ventricular repolarization delay and QT prolongation can be produced by genetic mutations of cardiac ion channels, giving rise to the idiopathic long QT (LQT) syndrome (Bezzina et al., 2015; Kass and Moss, 2003; Keating, 1996).

QT prolongation can also be produced by adverse blockade of cardiac ion channels by drugs or environmental chemicals, and is one of the central issues in cardiac safety and cardiotoxicity assessment (Kannankeril et al., 2010; Pollard et al., 2010; Sanguinetti and Tristani-Firouzi, 2006; Turker et al., 2017; Witchel, 2011). The most common target of adverse drug/chemical action is the rapid delayed rectifier K+ channel (i.e., the hERG channel), or IKr (Brown, 2004; Kannankeril et al., 2010; Vandenberg et al., 2012; Witchel, 2011). Examples of QT prolongation-related cardiac toxicity of environmental chemicals include trivalent arsenic As3+ and organophosphate poisoning (Chen et al., 2013; Chiang et al., 2002; Shiyovich et al., 2018; Thandar et al., 2021). In the present study, we examined the acute impact of low dose BPA on the electrical properties of female canine ventricular myocytes and tissues, with a focus on its effect on ventricular repolarization.

METHODS

Materials and reagents.

Bisphenol A, CAS 80-05-7, was from TCI America, lot 111909 (ground by Battelle), and was provided by the Division of the National Toxicology Program at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institute of Health. BPA was prepared as 10 mM stock solution in HPLC-grade dimethyl sulfoxide (DMS) and diluted in Tyrode’s or Krebs-Henseleit solution (see below) to reach the final experimental concentrations. With the exception of the dose-response experiment shown in Fig 1D to 1G, 1 nM BPA was used throughout the study based on the reported low nM BPA exposure level in humans (CDC, 2017). E-4031 dihydrochloride (E4031; a selective IKr/hERG channel blocker), 2,3-bis(4-Hydroxyphenyl)-propionitrile (DPN; an estrogen receptor, or ER, β agonist), Methyl-piperidino-pyrazole, 1,3-Bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-4-methyl-5-[4-(2-piperidinylethoxy)phenol]-1H-pyrazole dihydrochloride (MPP; an ERα antagonist), 4-[2-Phenyl-5,7-bis(trifluoromethyl)pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidin-3-yl]phenol (PHTPP; an ERβ antagonist), 4-Hydroxytamoxifen (4-OHT; an estrogen related receptor γ, or ERRγ deactivator), and ICI 182,780 (an ER α and β antagonist) were prepared as stock solutions in HPLC-grade DMSO. Experimental solutions were prepared in glassware, using BPA-free ultrapure water (18 MΩ; < 6 ppb total oxidizable organics) generated by the Milli-Q IQ7000 water purification system (MilliporeSigma, MA, USA). All experimental apparatuses were free of polycarbonate plastic. Chemicals used in this study were from Tocris Bioscience (Minneapolis, MN) or Sigma (St Louis, MO) unless otherwise stated.

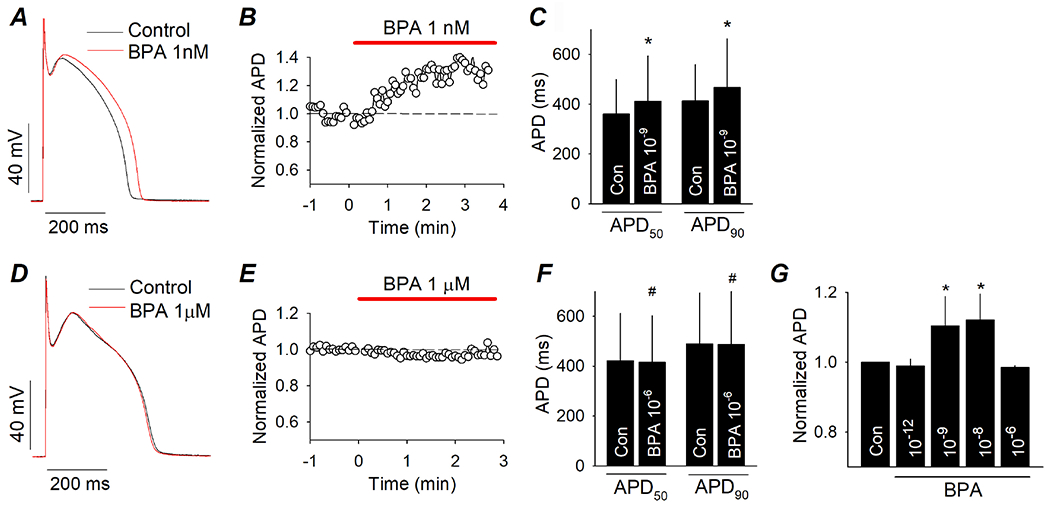

Figure 1. Low dose BPA delays repolarization in female canine ventricular myocytes.

(A) Representative AP recorded from canine ventricular myocytes under control and upon exposure to 10−9 M BPA. (B) Time course of the action of 10−9 M BPA on APD. APD were normalized to the average value in control (dash line). (C) Average APD50 and APD90 under control and after acute exposure to 10−9 M BPA. N = 5 myocytes from 3 hearts. (D) Representative AP under control and upon exposure to 10−6 M BPA. (E) Time course of the action of 10−6 M BPA on APD. (F) Average APD50 and APD90 under control and after acute exposure to 10−6 M BPA. N = 4 myocytes from 2 hearts. (G) Average APD90 under control and upon acute exposure to BPA at indicated doses. N = 3 to 5 myocytes from 3 hearts. *: P < 0.05 vs control in a paired t-test or ANOVA. #: P > 0.1 vs control in a paired t-test. Error bars are S.D.

Ethical approval.

Handling and usage of animals were in accordance with protocols approved by the University of Cincinnati Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol number 18-11-26-01), and in compliance with recommendations of the Panel on Euthanasia of the American Veterinary Medical Association.

Animals.

Adult female mongrel dogs, weighing 15-20 kg (approximately 6 – 8 months old), were obtained from a USDA approved vendor. A total of 5 dogs were used in the study. The animals were verified to be in normal health condition and free of signs of stress or illness upon arrival. The animals were not housed onsite or subjected to any treatment/surgery, and were euthanized upon arrival. For euthanasia, the front leg was shaved and prepped with betadine or nolvasan scrub and alcohol rinsed 3 times. A 18-20 gauge intravenous (IV) catheter was placed in the cephalic vein and secured with porous tape. Euthasol was administered IV (150 mg/kg body weight) and death was confirmed by negative heart auscultation as determined by stethoscope exanimation by a Laboratory Animal Medical Services veterinarian staff. Hearts were excised and washed, and tissues were collected from the hearts and used for ventricular myocytes isolation or ventricular wedge studies.

Canine cardiomyocyte isolation.

Wedge-shaped left ventricular (LV) free wall was dissected and cannulated via a descending branch of the left circumflex artery, and ventricular myocytes were dissociated using an enzymatic method as previous described (Dong et al., 2010). Briefly, LV wedge was perfused with a Tyrode’s solution containing 140 unit ml−1 collagenase (type II, Worthington, Lakewood, NJ, USA), 25 μM leupeptin and 0.32 unit ml−1 protease at 37°C. Pieces of tissue were dissected from the LV tissue following the initial digestion and further agitated and digested in the presence of collagenase (110 unit ml−1). Isolated myocytes were harvested, rinsed, and stored in a standard Tyrode solution containing 0.1 mM Ca2+.

Electrophysiological recordings.

Isolated ventricular myocytes were perfused with Tyrode’s solution containing (in mM): NaCl 140, KCl 5.4, MgCl2 1, CaCl2 1.8, HEPES 5, and glucose 10 (pH 7.4), and recorded using perforated patch-clamp as previously described (Dong et al., 2011). Glass pipettes were back-filled with a pipette solution containing (in mM): K-aspartate 110, KCl 20, NaCl 8, HEPES 10, MgCl2 2.5, CaCl2 0.1, and 240 mg/ml amphotericin B (pH adjusted to 7.2 with KOH), and had a resistance of 1.5 – 2.0 MΩ. APs were triggered with just-threshold 2 ms current steps at 1Hz at and recorded at steady state. Voltage clamp recordings of the transient outward current (Ito), the rapid delayed rectifier current (IKr), and the L-type Ca2+ current (ICaL) were performed at room temperature (24°C) as we previously described (Dong et al., 2006; Dong et al., 2010; Liang et al., 2014). All experiments were performed with an Axopatch-1B amplifier. Data were collected using pCLAMP9 (Axon Instruments, CA, USA) through an Axon Digidata 1322A data acquisition system (Axon instruments, CA, USA).

Surface electrocardiogram (EKG) recording from canine LV wedges.

Following dissection, LV wedges were quickly cannulated via a descending branch of the left circumflex artery, and perfused on a Langendorff apparatus with 37°C Krebs-Henseleit solution containing (in mM) NaCl 118, KCl 4.7, MgSO4 1.2, KH2PO4 1.2, EDTA 0.5, CaCl2 2.5, NaHCO3 25, and glucose 11, pH 7.4, bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2, at a pressure of 80 mmHg and perfusion rate of ~15 ml/min. Wedges were perfused under control conditions for at least 1 hour to allow stabilization before exposure to solution containing treatment drug. Wedges were continuously paced with 1.5x threshold 2 ms pulses at 1 Hz using a Grass S48 stimulator (Grass Instruments, Quincy, MA) through electrodes placed on the endocardial surface of the tissue. Bipolar EKG was continuously measured from the epicardial surface of the heart, with electrodes positioned at the base and apex ends of the wedge. Data collection and analysis were performed using the PowerLab 4/30 data acquisition system and LabChart 7 software (AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO).

Computation modeling.

Computational modeling of canine ventricular myocytes was constructed in MATLAB® based on the Hund-Rudy dynamic (HRD) model (Hund and Rudy, 2004) and a model that we described previously (Dong et al., 2011). To simulate the effects of BPA on IKr and ICaL, the IKr and ICaL conductances were modified by a static modifier of 0.7 and 0.9, respectively. The voltage clamp simulation was conducted by setting a current stimulus such that dV/dt is equal to zero. For IcaL, holding potential (VHold) was set to −50 mV and held for 10 sec to ensure the currents were stable, and then set to −50 mV to +10 mV in 10 mV increments, and then set back to VHold at −50 mV. For IKr, VHold was set at −40 mV, and then set to −30 mv to +30 mv in 10 mV increments and back to −40 mV.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using paired Student’s t-test for comparisons of variables before and after BPA exposure measured in the same myocyte or tissue (e.g., Figs 1C, 1F, 2B, 4C), or one-way ANOVA (Fig 1G), performed with GraphPad Prism 9.2.0 or SigmaPlot 11.0. Differences were considered statistically significant at a value of P < 0.05. N values indicate the number of myocytes with the exception of the results shown in Fig 4 where N indicates the number of ventricular wedges. Data were analyzed with SigmaPlot 11.0 or Microsoft Excel and expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

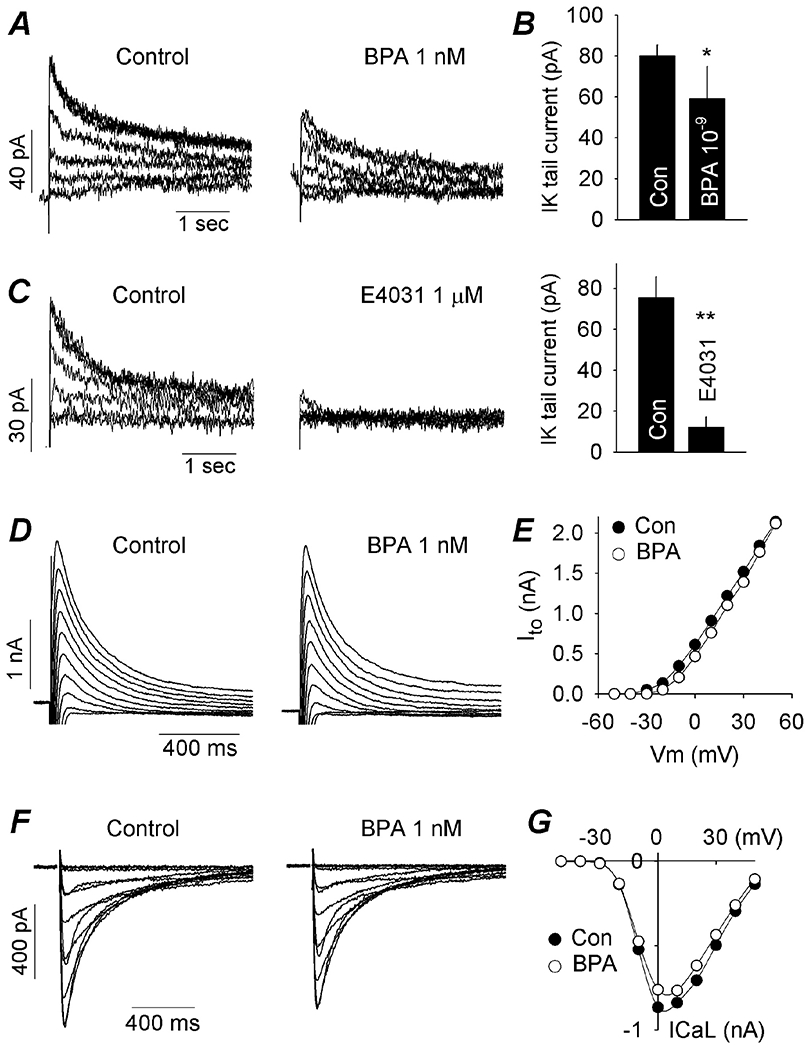

Figure 2. Acute impact of 10−9 M BPA on ionic currents in female canine ventricular myocytes.

(A) IKr tail current under control and upon rapid exposure to BPA. Tail currents were in response to depolarizing steps ranging from −20 to +30 mV in 10 mV increments from a holding potential of −40 mV, and recorded at −40 mV. (B) Average IKr tail current amplitude under control and after exposure to BPA. N = 5 myocytes from 5 hearts. (C) Effect of the selective IKr blocker E4031 on IKr tail current, confirming the identity of IKr. Right, average IKr tail current amplitude under control and in the presence of E4031. N = 3 myocytes from 2 hearts. (D) Representative Ito under control and upon exposure to BPA. Ito was activated with depolarizing steps ranging from - 30 to +50 mV in 10 mV increments, from a holding potential of −70mV at a frequency of 0.1 Hz. (E) Effect of BPA on Ito current-voltage relationship. (F) Representative ICaL under control and upon exposure to BPA. ICaL was elicited by voltage steps from −40 to +40 mV in 10 mV increment, from a holding potential of −50 mV at a frequency of 0.1 Hz. (G) Effect of BPA on ICaL current-voltage relationship. *: P < 0.05, **: P < 0.01 vs control in a paired t-test. Error bars are S.D.

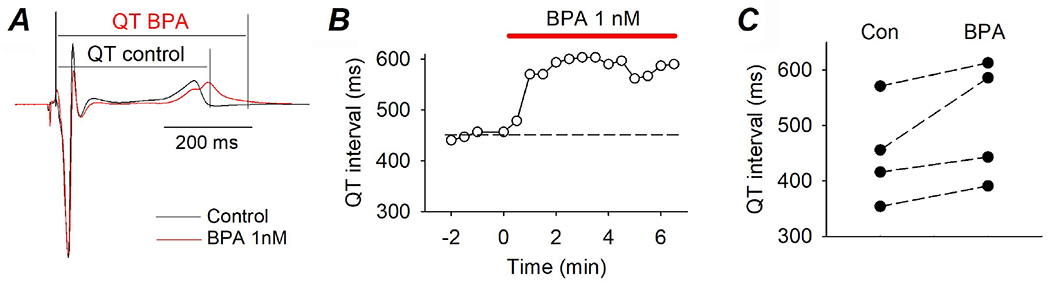

Figure 4. Acute impact of 10−9 M BPA on QT interval in canine LV wedges.

(A) Representative EKG recorded from the same LV wedge under control and upon exposure to BPA. QT intervals are indicated. (B) Time course of the effect of BPA on QT interval. (C) QT intervals recorded from 4 LV wedges under control and upon exposure to 10−9 M BPA.

RESULTS

Acute exposure to low dose BPA prolonged the action potential duration (APD) in female canine ventricular myocytes

The effect of BPA on cellular electrical properties of female canine ventricular myocytes was examined using whole-cell patch clamp recordings. Myocytes were maintained and perfused in a BPA-free solution. Exposure to 10−9 M BPA rapidly delayed action potential repolarization and prolonged APD without significantly altering the AP waveform morphology (Fig 1A). The BPA-induced APD prolongation occurred over a time course of ~ 5 min (Fig 1B). The average APD at 50% and 90% repolarization (APD50 and APD90) were 301 and 350 ms in control, respectively, and were 331 and 382 ms in the presence of 10−9 M BPA (n = 4, P < 0.05 for both, Fig 1C). In contrast to the effect of 10−9 M BPA, high dose 10−6 M BPA had no detectable effect on APD or morphology during the time period that was tested (up to 10 min; Fig 1D and E). Neither APD50 and APD90 was affected by 10−6 M BPA (Fig 1F). The dose response curve of BPA on canine ventricular APD was nonmonotonic with an inverted-U shape (Fig 1G).

BPA prolonged APD in canine ventricular myocytes through suppression of the IKr channel

The ionic mechanism of BPA-induced APD prolongation in canine ventricular myocytes was examined. 10−9 M BPA rapidly inhibited the IKr (hERG) K+ current, measured using standard voltage clamp protocol as the tail current following depolarizing steps (Fig 2A). The average IKr tail current amplitude was reduced from 80 pA prior to BPA exposure to 59 pA in the presence of BPA, measured in the same myocytes before and after exposure (n = 5, P < 0.05). The delayed rectifier current in the heart has two components, IKr (hERG) current and IKs (KCNQ1) current (Sanguinetti and Zou, 1997), and the recorded tail current could comprise both IKr and IKs. The identity of the recorded tail current was confirmed using the hERG-selective blocker E4031 in the absence of BPA (Fig 2C). E4031 blocked nearly the entire tail current, indicating that the tail current was indeed predominantly IKr. The amplitude or kinetics of the transient outward K+ current (ie, the Ito current), which can also have minor effect on canine cardiac APD (Sun and Wang, 2005), was not affected by 10−9 M BPA (Fig 2D and E). 10−9 M BPA resulted in a small suppression of the L-type Ca2+ (ICaL) current by an average of 9% (n = 7, P < 0.05; Fig 2F and G).

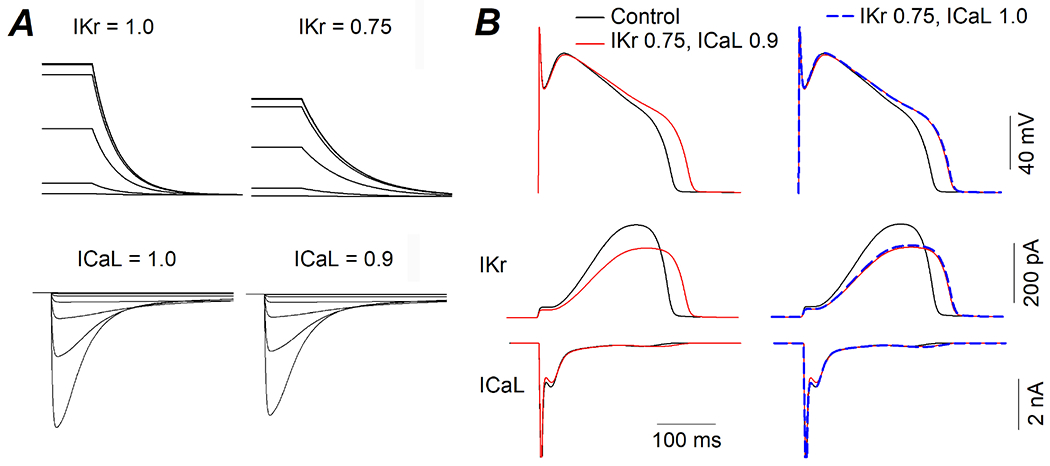

To determine whether the BPA-induced APD prolongation can be quantitatively accounted for by the observed effects of BPA on ionic currents, we performed mathematical modeling of canine ventricular myocyte based on a canine myocyte model that we described previously (Dong et al., 2011). Mathematical modeling, with its distinct strengths, is a powerful tool in biomedical research (Wooley et al., 2005). Model simulations allowed us to quantitatively identify key factors (in this case, key ionic conductances) that contributed to the BPA-induced APD prolongation, and gain insights into the current flows and interactions during the action potentials, IKr and ICaL were reduced by a factor of 0.25 and 0.1, respectively, based on the voltage clamp results to simulate the effects of BPA on ionic currents (Fig 3A). Such simulated “BPA exposure” produced a prolongation of the APD of the model myocyte (30 ms, or 13% prolongation of APD90) that closely resembled the experimental observation, as well as a notable reduction of IKr and a small reduction of ICaL during the action potential (Fig 3B, left). The relative impact of IKr and ICaL reductions on APD were examined. IKr reduction alone produced an APD prolongation that was almost the same as reductions of both IKr and ICaL, and ICaL reduction had only a very minor impact on APD (Fig 3B, right). These results suggest that the APD-prolongation effect of BPA on canine ventricular repolarization was mediated by suppression of IKr.

Figure 3. Computational modeling of the effects of BPA on canine ventricular myocytes.

(A) Simulated voltage clamp experiments of Ikr (top) and ICaL (bottom) under control condition (current = 1.0) and simulated BPA exposure where IKr was reduced by a factor of 0.25 (25%) and ICaL was reduced by a factor of 0.1 (10%). (B) Action potentials (top) and concurrent IKr and ICaL currents (middle and bottom) that were elicited by the action potentials under indicated conditions.

BPA acutely prolonged the QT interval in canine left ventricular (LV) wedges

Surface EKG was recorded from perfused and paced female LV wedges, and had distinct QRS complex and T wave (but no P wave which reflects atrial excitation). BPA (10−9 M) resulted in a moderate prolongation of the QT interval (Fig 4A). The effect occurred within minutes of exposure (Fig 4B), consistent with a rapid mechanism. The QT prolongation effect was consistently observed in all 4 LV wedges examined, from 4 hearts (Fig 4C), although the result did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.06) due to the small sample size and the large variation in baseline QT intervals.

ERβ contributes to the acute effects of BPA on canine ventricular repolarization

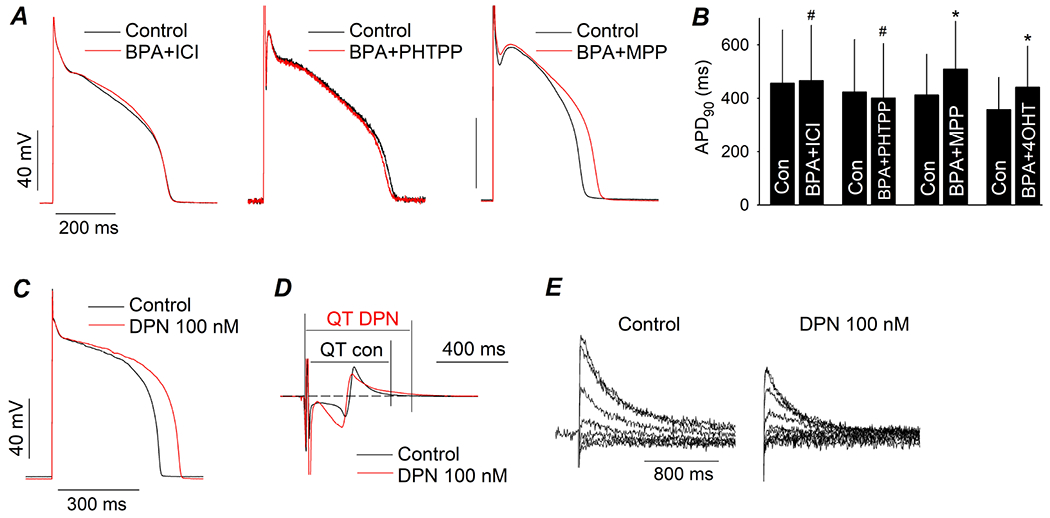

The acute effect of BPA on APD was abolished by the classic ER α and β blocker ICI 182,780 (Fig 5A). Further, the APD-prolongation effect of BPA was blocked by the ERβ antagonist PHTPP (n = 4, P > 0.1 PHTPP pretreatment vs PHTPP plus BPA), but not by the ERα antagonist MPP (n = 3, P < 0.05 MPP pretreatment vs MPP plus BPA) or by the ERRγ deactivator 4-OHT (n = 3, P < 0.05 4-OHT pretreatment vs 4-OHT plus BPA; Fig 5A and B). 100 nM DPN, an ERβ agonist, mimicked the effects of BPA and resulted in APD prolongation in ventricular myocytes (Fig 5C), prolongation of the QT interval in perfused LV wedges (n = 3, P = 0.09; Fig 5D), and suppression of the IKr tail current (n = 4, P < 0.05; Fig 5E). These results indicate that ERβ played a major role in mediating the effects of BPA on ventricular repolarization in canine heart.

Figure 5. ERβ contributes to the effects of BPA on canine ventricular repolarization.

(A) Representative AP recorded from canine ventricular myocytes under control and upon exposure to 1 nM BPA in the presence of 1 μM ICI 182,780, 5 μM PHTPP, or 1 μM MPP. Myocytes were pretreated with the ER blocker for 15 min prior to exposure to BPA. (B) Average APD90 under control and upon exposure to BPA in the presence of ICI 182,780, PHTPP, MPP, or 1 μM 4-OHT. N = 3 to 4 myocytes from 1 to 3 hearts. (C to E), representative effect of 100 nM DPN on AP in ventricular myocytes, surface EKG from LV wedge, and IKr tail current. #: P > 0.1, *: P < 0.05 vs control in a paired t-test. Error bars are S.D.

DISCUSSION

Delay of ventricular repolarization and QT prolongation due to adverse effects of chemical or pharmaceutical agents is one of the central issues in cardiac toxicity. Remarkably, the impact of BPA, a near-ubiquitous estrogenic EDC, on the electrical properties of the heart in large animals, particularly its impact on cardiac repolarization, is unknown. Here we showed that acute exposure to environmentally-relevant low dose BPA delayed AP repolarization in female canine ventricular myocytes and prolonged QT interval in female canine LV wedges. The ionic mechanism of the APD prolongation effect of BPA involved inhibition of the IKr current, counterbalanced by a small inhibition of ICaL. These results demonstrate that BPA has QT prolongation action in female canine hearts, and have potentially important implication for the proarrhythmic cardiac toxicity of BPA in large animals.

Delay of ventricular repolarization and QT prolongation is well-accepted as a marker for the risk of malignant ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death (Behere and Weindling, 2015; Bezzina et al., 2015; Kass and Moss, 2003; Veglio et al., 2004). In large animals, cardiac APs are broad with a distinct phase 2 plateau phase (Dong et al., 2011; Rosati et al., 2008). The morphology and duration of the cardiac action potential are tightly controlled by the balance between inward ionic currents (e.g., ICaL) and outward K+ currents (e.g., IKr). Perturbation of such balance can result in excessive prolongation of APD, which allows the cardiac Na+ and/or ICaL channels to recover from inactivation during the action potential and spontaneously reactivate, generating a type of ectopic electric activity known as early afterdepolarization, or EAD (Pogwizd and Bers, 2004; Sanguinetti and Tristani-Firouzi, 2006; Wit, 2018). Such aberrant spontaneous excitation is well-understood as a mechanism of arrhythmogenesis (Pogwizd and Bers, 2004; Sanguinetti and Tristani-Firouzi, 2006; Wit, 2018). Our study is the first to examine the impact of BPA on cardiac repolarization in the hearts of large animals and suggests that environmentally relevant concentration of BPA has QT liability. It is important to note that QT liability represents a risk factor for LQT-related arrhythmia, but does not necessarily translate to cardiac arrhythmias in normal hearts. The effects of BPA on ventricular APD and QT were modest, and these effects alone are unlikely to result in clinically-significant arrhythmia events in normal hearts under physiological conditions. Indeed, we did not observe any arrhythmia activities at the myocyte or tissue levels in our experiments. However, the QT prolongation toxicity of BPA may increase the risk of arrhythmias under pathophysiological conditions such as genetic LQT syndrome or reduced baseline cardiac repolarization capacities in cardiac diseases (e.g., heart failure).

The rapid effect of BPA on ventricular repolarization in female canine hearts was blocked by the classic ER receptor blocker ICI 182,780, and likely represents an estrogenic effect. This notion is consistent with the influence of estrogen on QT prolongation. It is known that the female gender is an independent risk factor for symptomatic LQT syndrome (Gowd and Thompson, 2012; James et al., 2007; Krahn et al., 2022; Lehmann et al., 1996). Females have a longer corrected QT interval (QTc) compared with males (Abi-Gerges et al., 2004; Cheng, 2006; Du et al., 2006), and are more prone to the development of lethal ventricular arrhythmias under drug/chemical-induced QT prolongation, with the majority of such cases happening in women (Drici et al., 1998; Lehmann et al., 1996; Locati et al., 1998; Makkar et al., 1993). Animal studies in rabbits have also demonstrated longer QT interval in females (Drici et al., 1996; Valverde et al., 2003) and higher susceptibility in females to lethal arrhythmias induced by QT-prolonging chemicals (Pham et al., 2001; Ruan et al., 2004; Spear and Moore, 2000). It is likely that female sex hormones, including estrogen, contribute to the gender difference in QT interval. Susceptibility to drug/chemical-induced QT prolongation varies during the menstrual cycle in women, and is greater in the late follicular phase, coinciding with a higher level of estrogen (Rodriguez et al., 2001). Estrogen replacement therapy has been shown to prolong QT in postmenopausal women (Carnethon et al., 2003; Haseroth et al., 2000; Kadish et al., 2004). Prolongation of QT interval by estrogen replacement was also observed in ovariectomized female rabbits (Drici et al., 1996). It is reasonable to speculate that estrogen plays a key role in establishing and maintaining the sensitivity of female canine ventricular myocytes to BPA-induced cardiac repolarization delay. It is possible that myocytes in male and ovariectomized female canine hearts do not have the same response to acute exposure to BPA as female canine cardiomyocytes, although this remains to be experimentally tested. Our results resemble the acute effects of 17β-estradiol (E2) in female guinea pig ventricular myocytes; it has been shown that physiological concentration of E2 acutely suppressed the hERG channel and prolonged APD in female guinea pig ventricular myocytes (Kurokawa et al., 2008).

The effect of BPA on APD in canine ventricular myocytes was likely mediated by ERβ signaling; thus, BPA’s rapid effect was blocked by the ERβ blocker PHTPP, but not by the ERα blocker MPP, and was mimicked by ERβ activation. Both ERα and ERβ, including those localized to the membrane, have been shown to be expressed in cardiomyocytes from species including rat and human (Arias-Loza et al., 2008; Chung et al., 2004; Mendelsohn and Karas, 2005). Membrane ERs have been shown to activate kinases including protein kinase A and C (Fu and Simoncini, 2008; Levin, 2008), which are known to modulate various elements involved in myocyte Ca2+ handling (Bers, 2002; Bers and Guo, 2005). ERβ-mediated signaling has been shown to play a central role in the rapid actions of BPA and the related analog bisphenol S (BPS) in female rodent cardiac myocytes (Gao et al., 2013; Gao et al., 2015; Yan et al., 2011). A similar key role of ERβ in mediating the rapid effects of estrogenic EDCs has been described in cerebellar granular cells (Le and Belcher, 2010). Further, we showed in previous studies that ERα and ERβ have opposing actions on myocyte Ca2+ handling and arrhythmogenesis in rodent cardiac myocytes, and that the counterbalance of ERβ- and ERα-signaling is the prime regulator of sex-specific estrogen sensitivity of rodent cardiac myocytes (Belcher et al., 2012; Gao et al., 2015).

Ion channels are a target that is affected by BPA. BPA has been shown to affect the expression and function of a variety of ion channels in various systems (Soriano et al., 2016). Other examples of BPA affecting ion channels include micromolar BPA inducing vasodilation in rat aorta smooth muscle through inhibition of ICal (Feiteiro et al., 2018), and BPA increasing sodium ramp currents in mousse dorsal root ganglion neurons (Soriano et al., 2019). In mice treated with BPA (100 μg/kg/day), decreased expression and function of Na+ and K+ currents was found in in pancreatic islets (Martinez-Pinna et al., 2019). Acute exposure to BPA analogs has been shown to diminished KATP channel activity in mouse pancreatic β-cells (Marroqui et al., 2021). We showed that at the ionic current level, BPA rapidly affected two currents, the outward IKr current, and the inward ICaL current. BPA rapidly suppressed the IKr channel, which is commonly found as the central mediator of chemical/drug induced QT prolongation (Brown, 2004; Kannankeril et al., 2010; Roden, 2019; Vandenberg et al., 2012; Witchel, 2011). The critical role of IKr (hERG) in mediating cardiac repolarization is illustrated by the fact that loss-of-function mutations of hERG result in the type 2 idiopathic LQT syndrome (Sanguinetti and Tristani-Firouzi, 2006). BPA also suppressed ICaL channel, an effect similar to the small suppression of ICaL in rodent cardiac myocytes by low dose BPA (Liang et al., 2014). The two effects of BPA should have the opposite effects on AP repolarization; suppression of IKr prolongs APD while suppression of ICaL reduces APD. Using mathematical modeling of canine ventricular myocytes, we showed that suppression of IKr by BPA had a dominant effect on APD that was only very slightly counterbalanced by reduction of ICaL. Our modeling results indicate that IKr suppression mediated the APD prolongation effect of BPA.

We examined the effect of BPA on cardiac repolarization at environmentally-relevant low dose. Low dose BPA is defined as ≤ 100 nM by the Chapel Hill expert panel (Wetherill et al., 2007), and typical environmentally-relevant human internal exposure dose is at the low nM range (CDC, 2017). Low and high doses of BPA can have distinct effects on cardiac electrical properties. In the sub nM to 1 μM dose range, the effect of BPA on canine cardiac AP had a nonmonotonic dose response (Fig 1), and the low dose effect of BPA in canine myocytes contrasts with the effects of high dose BPA in human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes (iPSC-CMs). It has been shown that mid to high μM range BPA acutely shortened APD in iPSC-CMs (Hyun et al., 2021; Kofron et al., 2021; Prudencio et al., 2021). Interestingly, the effect of high dose BPA on APD likely was also mediated by suppression of ICaL and IKr, with the suppression of ICaL appeared to be the dominant one (Hyun et al., 2021; Prudencio et al., 2021). Indeed, a recent study using human iPSC-CM cardiac microtissue demonstrated such opposite effect of BPA at low and high dose on iPSC-CM repolarization; BPA prolonged APD at 1 nM, and shortened APD at μM concentration (Kofron et al., 2021). Our results are consistent with the findings by Kofron et al, and defined the dose-dependent effect of BPA on canine ventricular repolarization and underlying ionic mechanism using patch clamp, which is the gold standard of cellular electrophysiological analysis.

Limitations of the study: Our previous studies demonstrated that BPA and related chemicals had female-specific proarrhythmic cardiac toxicity in rodent hearts through alteration of Ca2+ handling (Gao et al., 2013; Gao et al., 2015; Yan et al., 2011). Here, we show that BPA had an additional proarrhythmic mechanism through alteration of cardiac repolarization in female canine ventricular myocytes. We had very limited access to canine hearts and focused only on female hearts due to the known impact of estrogen on cardiac repolarization in females. It would be of interest to further define the sex-specificity of BPA’s QT prolongation action. The estrous cycle stage of the animals was not determined, which is another limitation. In future studies, defining the impact of BPA exposure in heart models that are prone to QT prolongation-induced arrhythmia such as LQT syndrome would be of clinical significance.

CONCLUSION

In female canine hearts, acute exposure to environmentally-relevant low dose BPA delayed ventricular AP repolarization and prolonged QT interval, which are well-known markers for the risk of malignant ventricular arrhythmias. The effect of BPA on ventricular repolarization was mediated by inhibition of the IKr current. BPA exposure has QT prolongation liability and potential pro-arrhythmic toxicity in female canine heart, and possibly the hearts of other large animals.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) grant ES027855 and the University of Cincinnati Center for Environmental Genetics through the NIEHS award P30ES006096.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Credit Author Statement

Jianyong Ma: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing Paul Niklewski: Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis Hong-Sheng Wang: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

REFERENCES

- Abi-Gerges N, Philp K, Pollard C, Wakefield I, Hammond TG, Valentin JP, 2004. Sex differences in ventricular repolarization: from cardiac electrophysiology to Torsades de Pointes. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 18, 139–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aboul Ezz HS, Khadrawy YA, Mourad IM, 2015. The effect of bisphenol A on some oxidative stress parameters and acetylcholinesterase activity in the heart of male albino rats. Cytotechnology 67, 145–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arias-Loza PA, Jazbutyte V, Pelzer T, 2008. Genetic and pharmacologic strategies to determine the function of estrogen receptor alpha and estrogen receptor beta in cardiovascular system. Gend Med 5 Suppl A, S34–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behere SP, Weindling SN, 2015. Inherited arrhythmias: The cardiac channelopathies. Ann Pediatr Cardiol 8, 210–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belcher SM, Chen Y, Yan S, Wang HS, 2012. Rapid estrogen receptor-mediated mechanisms determine the sexually dimorphic sensitivity of ventricular myocytes to 17β-estradiol and the environmental endocrine disruptor bisphenol A. Endocrinology 153, 712–720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belcher SM, Gear RB, Kendig EL, 2015. Bisphenol A alters autonomic tone and extracellular matrix structure and induces sex-specific effects on cardiovascular function in male and female CD-1 mice. Endocrinology 156, 882–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bers DM, 2002. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature 415, 198–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bers DM, Guo T, 2005. Calcium signaling in cardiac ventricular myocytes. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1047, 86–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bezzina CR, Lahrouchi N, Priori SG, 2015. Genetics of sudden cardiac death. Circ Res 116, 1919–1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AM, 2004. Drugs, hERG and sudden death. Cell Calcium 35, 543–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai S, Rao X, Ye J, Ling Y, Mi S, Chen H, Fan C, Li Y, 2020. Relationship between urinary bisphenol a levels and cardiovascular diseases in the U.S. adult population, 2003-2014. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 192, 110300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calafat AM, Ye X, Wong LY, Reidy JA, Needham LL, 2008. Exposure of the U.S. population to bisphenol A and 4-tertiary-octylphenol: 2003-2004. Environ Health Perspect 116, 39–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnethon MR, Anthony MS, Cascio WE, Folsom AR, Rautahaiju PM, Liao D, Evans GW, Heiss G, 2003. A prospective evaluation of the risk of QT prolongation with hormone replacement therapy: the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Ann Epidemiol 13, 530–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catenza CJ, Farooq A, Shubear NS, Donkor KK, 2021. A targeted review on fate, occurrence, risk and health implications of bisphenol analogues. Chemosphere 268, 129273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC, 2017. “National report on human exposure to environmental chemicals”. https://wwwcdcgov/biomonitoring/pdf/FourthReport_UpdatedTables_Volume1_Jan2017pdf.

- Chapalamadugu KC, Vandevoort CA, Settles ML, Robison BD, Murdoch GK, 2014. Maternal bisphenol a exposure impacts the fetal heart transcriptome. PLoS One 9, e89096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Wu F, Parvez F, Ahmed A, Eunus M, McClintock TR, Patwary TI, Islam T, Ghosal AK, Islam S, Hasan R, Levy D, Sarwar G, Slavkovich V, van Geen A, Graziano JH, Ahsan H, 2013. Arsenic exposure from drinking water and QT-interval prolongation: results from the Health Effects of Arsenic Longitudinal Study. Environ Health Perspect 121, 427–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J, 2006. Evidences of the gender-related differences in cardiac repolarization and the underlying mechanisms in different animal species and human. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 20, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang CE, Luk HN, Wang TM, Ding PY, 2002. Prolongation of cardiac repolarization by arsenic trioxide. Blood 100, 2249–2252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung TH, Wang SM, Wu JC, 2004. 17beta-estradiol reduces the effect of metabolic inhibition on gap junction intercellular communication in rat cardiomyocytes via the estrogen receptor. J Mol Cell Cardiol 37, 1013–1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper BL, Posnack NG, 2022. Characteristics of Bisphenol Cardiotoxicity: Impaired Excitability, Contractility, and Relaxation. Cardiovasc Toxicol 22, 273–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Bourguignon JP, Giudice LC, Hauser R, Prins GS, Soto AM, Zoeller RT, Gore AC, 2009. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: an Endocrine Society scientific statement. Endocr Rev 30, 293–342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias P, Tvrdý V, Jirkovský E, Dolenc MS, Peterlin Mašič L, Mladěnka P, 2022. The effects of bisphenols on the cardiovascular system. Crit Rev Toxicol 52, 66–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong M, Niklewski PJ, Wang HS, 2011. Ionic mechanisms of cellular electrical and mechanical abnormalities in Brugada syndrome. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300, H279–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong M, Sun X, Prinz AA, Wang HS, 2006. Effect of simulated I(to) on guinea pig and canine ventricular action potential morphology. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291, H631–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong M, Yan S, Chen Y, Niklewski PJ, Sun X, Chenault K, Wang HS, 2010. Role of the transient outward current in regulating mechanical properties of canine ventricular myocytes. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 21, 697–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drici MD, Burklow TR, Haridasse V, Glazer RI, Woosley RL, 1996. Sex hormones prolong the QT interval and downregulate potassium channel expression in the rabbit heart. Circulation 94, 1471–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drici MD, Knollmann BC, Wang WX, Woosley RL, 1998. Cardiac actions of erythromycin: influence of female sex. Jama 280, 1774–1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du XJ, Fang L, Kiriazis H, 2006. Sex dimorphism in cardiac pathophysiology: experimental findings, hormonal mechanisms, and molecular mechanisms. Pharmacol Ther 111, 434–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feiteiro J, Mariana M, Gloria S, Cairrao E, 2018. Inhibition of L-type calcium channels by Bisphenol A in rat aorta smooth muscle. J Toxicol Sci 43, 579–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu X, Xu J, Zhang R, Yu J, 2020. The association between environmental endocrine disruptors and cardiovascular diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Res 187, 109464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu XD, Simoncini T, 2008. Extra-nuclear signaling of estrogen receptors. IUBMB Life 60, 502–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Liang Q, Chen Y, Wang HS, 2013. Molecular mechanisms underlying the rapid arrhythmogenic action of bisphenol A in female rat hearts. Endocrinology 154, 4607–4617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Ma J, Chen Y, Wang HS, 2015. Rapid responses and mechanism of action for low-dose bisphenol S on ex vivo rat hearts and isolated myocytes: evidence of female-specific proarrhythmic effects. Environ Health Perspect 123, 571–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Wang HS, 2014. Impact of bisphenol a on the cardiovascular system - epidemiological and experimental evidence and molecular mechanisms. Int J Environ Res Public Health 11, 8399–8413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geens T, Aerts D, Berthot C, Bourguignon JP, Goeyens L, Lecomte P, Maghuin-Rogister G, Pironnet AM, Pussemier L, Scippo ML, Van Loco J, Covaci A, 2012. A review of dietary and non-dietary exposure to bisphenol-A. Food Chem Toxicol 50, 3725–3740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg I, Zareba W, Moss AJ, 2008. Long QT Syndrome. Curr Probl Cardiol 33, 629–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gore AC, Chappell VA, Fenton SE, Flaws JA, Nadal A, Prins GS, Toppari J, Zoeller RT, 2015. EDC-2: The Endocrine Society’s Second Scientific Statement on Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals. Endocr Rev 36, E1–e150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowd BM, Thompson PD, 2012. Effect of female sex on cardiac arrhythmias. Cardiol Rev 20, 297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haseroth K, Seyffart K, Wehling M, Christ M, 2000. Effects of progestin-estrogen replacement therapy on QT-dispersion in postmenopausal women. Int J Cardiol 75, 161–165; discussion 165–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hund TJ, Rudy Y, 2004. Rate dependence and regulation of action potential and calcium transient in a canine cardiac ventricular cell model. Circulation 110, 3168–3174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyun SA, Lee CY, Ko MY, Chon SH, Kim YJ, Seo JW, Kim KK, Ka M, 2021. Cardiac toxicity from bisphenol A exposure in human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 428, 115696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James AF, Choisy SC, Hancox JC, 2007. Recent advances in understanding sex differences in cardiac repolarization. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 94, 265–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadish AH, Greenland P, Limacher MC, Frishman WH, Daugherty SA, Schwartz JB, 2004. Estrogen and progestin use and the QT interval in postmenopausal women. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 9, 366–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannankeril P, Roden DM, Darbar D, 2010. Drug-induced long QT syndrome. Pharmacol Rev 62, 760–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kass RS, Moss AJ, 2003. Long QT syndrome: novel insights into the mechanisms of cardiac arrhythmias. The Journal of clinical investigation 112, 810–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating MT, 1996. The long QT syndrome. A review of recent molecular genetic and physiologic discoveries. Medicine (Baltimore) 75, 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kofron CM, Kim TY, Munarin F, Soepriatna AH, Kant RJ, Mende U, Choi BR, Coulombe KLK, 2021. A predictive in vitro risk assessment platform for pro-arrhythmic toxicity using human 3D cardiac microtissues. Sci Rep 11, 10228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koneva LA, Vyas AK, McEachin RC, Puttabyatappa M, Wang HS, Sartor MA, Padmanabhan V, 2017. Developmental programming: Interaction between prenatal BPA and postnatal overfeeding on cardiac tissue gene expression in female sheep. Environ Mol Mutagen 58, 4–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krahn AD, Laksman Z, Sy RW, Postema PG, Ackerman MJ, Wilde AAM, Han HC, 2022. Congenital Long QT Syndrome. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 8, 687–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer DB, Zimetbaum PJ, 2011. Long-QT syndrome. Cardiol Rev 19, 217–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurokawa J, Tamagawa M, Harada N, Honda S, Bai CX, Nakaya H, Furukawa T, 2008. Acute effects of oestrogen on the guinea pig and human IKr channels and drug-induced prolongation of cardiac repolarization. J Physiol 586, 2961–2973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le HH, Belcher SM, 2010. Rapid signaling actions of environmental estrogens in developing granule cell neurons are mediated by estrogen receptor B. Endocrinology 151, 5689–5699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann MH, Hardy S, Archibald D, quart B, MacNeil DJ, 1996. Sex difference in risk of torsade de pointes with d,l-sotalol. Circulation 94, 2535–2541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ER, 2008. Rapid signaling by steroid receptors. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295, R1425–1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Q, Gao X, Chen Y, Hong K, Wang HS, 2014. Cellular mechanism of the nonmonotonic dose response of bisphenol A in rat cardiac myocytes. Environ Health Perspect 122, 601–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locati EH, Zareba W, Moss AJ, Schwartz PJ, Vincent GM, Lehmann MH, Towbin JA, Priori SG, Napolitano C, Robinson JL, Andrews M, Timothy K, Hall WJ, 1998. Age- and sex-related differences in clinical manifestations in patients with congenital long-QT syndrome: findings from the International LQTS Registry. Circulation 97, 2237–2244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makkar RR, Fromm BS, Steinman RT, Meissner MD, Lehmann MH, 1993. Female gender as a risk factor for torsades de pointes associated with cardiovascular drugs. Jama 270, 2590–2597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malaisé Y, Lencina C, Cartier C, Olier M, Ménard S, Guzylack-Piriou L, 2020. Perinatal oral exposure to low doses of bisphenol A, S or F impairs immune functions at intestinal and systemic levels in female offspring mice. Environ Health 19, 93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marroqui L, Martinez-Pinna J, Castellano-Muñoz M, Dos Santos RS, Medina-Gali RM, Soriano S, Quesada I, Gustafsson JA, Encinar JA, Nadal A, 2021. Bisphenol-S and Bisphenol-F alter mouse pancreatic β-cell ion channel expression and activity and insulin release through an estrogen receptor ERP mediated pathway. Chemosphere 265, 129051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Pinna J, Marroqui L, Hmadcha A, Lopez-Beas J, Soriano S, Villar-Pazos S, Alonso-Magdalena P, Dos Santos RS, Quesada I, Martin F, Soria B, Gustafsson J, Nadal A, 2019. Oestrogen receptor β mediates the actions of bisphenol-A on ion channel expression in mouse pancreatic beta cells. Diabetologia 62, 1667–1680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendelsohn ME, Karas RH, 2005. Molecular and cellular basis of cardiovascular gender differences. Science 308, 1583–1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon S, Yu SH, Lee CB, Park YJ, Yoo HJ, Kim DS, 2021. Effects of bisphenol A on cardiovascular disease: An epidemiological study using National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003–2016 and meta-analysis. Sci Total Environ 763, 142941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreman J, Takesono A, Trznadel M, Winter MJ, Perry A, Wood ME, Rogers NJ, Kudoh T, Tyler CR, 2018. Estrogenic Mechanisms and Cardiac Responses Following Early Life Exposure to Bisphenol A (BPA) and Its Metabolite 4-Methyl-2,4-bis( p-hydroxyphenyl)pent-1-ene (MBP) in Zebrafish. Environ Sci Technol 52, 6656–6665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagarajan M, Raja B, Manivannan J, 2021. Exposure to a “safe” dose of environmental pollutant bisphenol A elevates oxidative stress and modulates vasoactive system in hypertensive rats. Hum Exp Toxicol 40, S654–s665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park YJ, Pang WK, Ryu DY, Adegoke EO, Rahman MS, Pang MG, 2021. Bisphenol A exposure increases epididymal susceptibility to infection in mice. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 208, 111476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel BB, Raad M, Sebag IA, Chalifour LE, 2013. Lifelong exposure to bisphenol a alters cardiac structure/function, protein expression, and DNA methylation in adult mice. Toxicol Sci 133, 174–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham TV, Sosunov EA, Gainullin RZ, Danilo P Jr., Rosen MR, 2001. Impact of sex and gonadal steroids on prolongation of ventricular repolarization and arrhythmias induced by I(K)-blocking drugs. Circulation 103, 2207–2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogwizd SM, Bers DM, 2004. Cellular basis of triggered arrhythmias in heart failure. Trends Cardiovasc Med 14, 61–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard CE, Abi Gerges N, Bridgland-Taylor MH, Easter A, Hammond TG, Valentin JP, 2010. An introduction to QT interval prolongation and non-clinical approaches to assessing and reducing risk. British journal of pharmacology 159, 12–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posnack NG, Jaimes R 3rd, Asfour H, Swift LM, Wengrowski AM, Sarvazyan N, Kay MW, 2014. Bisphenol A exposure and cardiac electrical conduction in excised rat hearts. Environ Health Perspect 122, 384–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Predieri B, Bruzzi P, Bigi E, Ciancia S, Madeo SF, Lucaccioni L, Iughetti L, 2020. Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals and Type 1 Diabetes. Int J Mol Sci 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prudencio TM, Swift LM, Guerrelli D, Cooper B, Reilly M, Ciccarelli N, Sheng J, Jaimes R, Posnack NG, 2021. Bisphenol S and Bisphenol F Are Less Disruptive to Cardiac Electrophysiology, as Compared With Bisphenol A. Toxicol Sci 183, 214–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roden DM, 2019. A current understanding of drug-induced QT prolongation and its implications for anticancer therapy. Cardiovasc Res 115, 895–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez I, Kilborn MJ, Liu XK, Pezzullo JC, Woosley RL, 2001. Drug-induced QT prolongation in women during the menstrual cycle. Jama 285, 1322–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers JA, Mishra MK, Hahn J, Greene CJ, Yates RM, Metz LM, Yong VW, 2017. Gestational bisphenol-A exposure lowers the threshold for autoimmunity in a model of multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114, 4999–5004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosati B, Dong M, Cheng L, Liou SR, Yan Q, Park JY, Shiang E, Sanguinetti M, Wang HS, McKinnon D, 2008. Evolution of ventricular myocyte electrophysiology. Physiol Genomics 35, 262–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruan YF, Liu N, Zhou Q, Li Y, Wang L, 2004. Experimental study on the mechanism of sex difference in the risk of torsade de pointes. Chin Med J (Engl) 117, 538–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanguinetti MC, Tristani-Firouzi M, 2006. hERG potassium channels and cardiac arrhythmia. Nature 440, 463–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanguinetti MC, Zou A, 1997. Molecular physiology of cardiac delayed rectifier K+ channels. Heart Vessels Suppl 12, 170–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiyovich A, Matot R, Elyagon S, Liel-Cohen N, Rosman Y, Shrot S, Kassirer M, Katz A, Etzion Y, 2018. QT Prolongation as an Isolated Long-Term Cardiac Manifestation of Dichlorvos Organophosphate Poisoning in Rats. Cardiovasc Toxicol 18, 24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano S, Gil-Rivera M, Marroqui L, Alonso-Magdalena P, Fuentes E, Gustafsson JA, Nadal A, Martinez-Pinna J, 2019. Bisphenol A Regulates Sodium Ramp Currents in Mouse Dorsal Root Ganglion Neurons and Increases Nociception. Sci Rep 9, 10306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano S, Ripoll C, Alonso-Magdalena P, Fuentes E, Quesada I, Nadal A, Martinez-Pinna J, 2016. Effects of Bisphenol A on ion channels: Experimental evidence and molecular mechanisms. Steroids 111, 12–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear JF, Moore EN, 2000. Gender and seasonally related differences in myocardial recovery and susceptibility to sotalol-induced arrhythmias in isolated rabbit hearts. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 11, 880–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Wang HS, 2005. Role of the transient outward current (Ito) in shaping canine ventricular action potential--a dynamic clamp study. J Physiol 564, 411–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thandar SM, Naing KT, Sein MT, 2021. Serum High-sensitivity C-reactive Protein Level and Corrected QT Interval in Agricultural Workers in Myanmar Exposed to Chronic Occupational Organophosphate Pesticides. J uoeh 43, 173–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turker I, Ai T, Itoh H, Horie M, 2017. Drug-induced fatal arrhythmias: Acquired long QT and Brugada syndromes. Pharmacol Ther 176, 48–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valverde ER, Biagetti MO, Bertran GR, Arini PD, Bidoggia H, Quinteiro RA, 2003. Developmental changes of cardiac repolarization in rabbits: implications for the role of sex hormones. Cardiovasc Res 57, 625–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg JI, Perry MD, Perrin MJ, Mann SA, Ke Y, Hill AP, 2012. hERG K(+) channels: structure, function, and clinical significance. Physiological reviews 92, 1393–1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg LN, Hauser R, Marcus M, Olea N, Welshons WV, 2007. Human exposure to bisphenol A (BPA). Reproductive toxicology 24, 139–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veglio M, Chinaglia A, Cavallo-Perin P, 2004. QT interval, cardiovascular risk factors and risk of death in diabetes. J Endocrinol Invest 27, 175–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetherill YB, Akingbemi BT, Kanno J, McLachlan JA, Nadal A, Sonnenschein C, Watson CS, Zoeller RT, Belcher SM, 2007. In vitro molecular mechanisms of bisphenol A action. Reprod Toxicol 24, 178–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Win-Shwe TT, Yanagisawa R, Koike E, Takano H, 2021. Dietary exposure to bisphenol A affects memory function and neuroimmune biomarkers in allergic asthmatic mice. J Appl Toxicol 41, 1527–1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wit AL, 2018. Afterdepolarizations and triggered activity as a mechanism for clinical arrhythmias. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witchel HJ, 2011. Drug-induced hERG block and long QT syndrome. Cardiovasc Ther 29, 251–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wooley JC, Lin HS, Council NR, 2005. Computational modeling and simulation as enablers for biological discovery, Catalyzing inquiry at the interface of computing and biology. National Academies Press (US). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan S, Chen Y, Dong M, Song W, Belcher SM, Wang HS, 2011. Bisphenol A and 17β-estradiol promote arrhythmia in the female heart via alteration of calcium handling. PLoS One 6, e25455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan S, Song W, Chen Y, Hong K, Rubinstein J, Wang HS, 2013. Low-dose bisphenol A and estrogen increase ventricular arrhythmias following ischemia-reperfusion in female rat hearts. Food Chem Toxicol 56, 75–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]