Abstract

Global food systems are broken and in need of profound change. These imbalances and vulnerabilities are particularly strong in cities, where most of the global population lives and that are at the core of the major challenges linked with food production and consumption. The food system transition needs cities as key game-changers towards more sustainable, equitable, healthier and fairer food systems. Against this backdrop, the present article analyses the role of food policies within urban policies, with a focus on Italian cities. In particular, the article discusses data collected from representatives of 100 municipalities across Northern, Central and Southern Italy. Moreover, it addresses the types of policies and initiatives adopted at the local level, the main obstacles encountered, the role of national and international city networks and the impact of Covid-19 on urban food security, with the aim to identify potential models of urban food policies as a structural component of a broader urban agenda. By doing this, the article aims at filling a research gap in current literature, as it is the first large-scale survey on urban food policies in Italy, identifying models of urban food policies that are already being developed within broader urban development agendas.

Keywords: Urban food policies, Urban food waste, Urban food governance, Sustainable development, Food security, Urban food security, Covid-19, Italy

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Over the last decades cities have progressively come to the fore as new crucial actors in the global and local food security geography (Artioli et al., 2017; Weerabahu et al., 2021). As of today, cities host more than half of global population and they are at the core of some of the deepest food security-related transformations and contradictions (Sonnino et al., 2016), especially if we consider that over 68 % of the world's population is expected to live in urban centres by 2050 (UNDESA, 2018). Among these contradictions, the environmental footprint of our food systems (C40 Cities et al., 2019), the progressive shift towards unhealthy diets and consumer patterns (Willett et al., 2019) the increase of food waste (Fattibene et al., 2020), and the rise in the levels of overweight, obesity and Non Communicable Diseases are increasingly becoming urban problems (Cities Changing Diabetes, 2017; Mozaffarian et al., 2011). It must not be forgotten that up to 70 % of all food produced globally is already consumed in cities (FAO & RUAF, 2016), which also account for over 75 % of natural resources consumption and over 50 % of global waste production (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2019).

Hence, current and future urbanisation rates will pose tremendous pressures on global food supply chains (FAO, 2018), with 2.5 billion people forecasted to move towards urban settlements in the next three decades (FAO, 2020, FAO, 2020, FAO, 2020). As such, urbanisation requires a radical rethinking of every aspect of the food system (FAO, 2020, FAO, 2020, FAO, 2020). Cities have the potential to drive the process of food transformation by incubating and exchanging innovative approaches thanks to access capital and know-how (EUROCITIES 2020; European Commission, 2019). In this context, the City-Region Food System approach (Blay-Palmer et al., 2018) is increasingly emerging as a promising method in international, national, and regional policy agendas as a set of tools to analyse, plan and monitor material and immaterial flows of resources —food, waste, people, and knowledge — from rural to peri-urban to urban and back again, and the policies and process needed to enable sustainability.

In these years, several studies have showed that cities and local authorities are a key component of the sustainability agenda (Fattibene et al., 2019; Steel, 2008) with some estimating that more than two thirds of the 169 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) targets would require a full engagement of, and coordination with, local and regional governments to be achieved (Cavalli & Farnia, 2019; SDSN & Telos, 2019). In addition, a growing research body on urban food governance has unveiled the role that integrated urban food governance can have on several dimension of urban food security. Although some authors have argued that such studies have remained somewhat abstract rather than transformative (Candel, 2014; Sonnino, 2019), others have revealed that cities can launch innovative programs and initiatives to shorten supply chains for instance by fully exploiting the potential of greener public procurement (Morley & Morgan, 2021; Sonnino, 2009), supporting urban agriculture (RUAF, 2019) and designing effective policies to tackle food waste (Boschini et al., 2018; Cicatiello et al., 2016; Dubbeling et al., 2016). Cities' engagement and integrated urban food policies are crucial to achieve the ambitious goals set in the European Farm to Fork strategy, that, calls for a stronger Citizens' engagement to drive transition towards more sustainable food systems (European Commission, 2020).

2. Framing the analysis in the existing literature debate: filling gaps and limitations in the current literature

At the European level, an extensive literature on urban food governance has emerged in the past years. A study conducted in the Netherlands (Sibbing et al., 2021) argues that although not ubiquitous and often not in a holistic way, various food challenges have been integrated across municipal policies. However, it acknowledged that it remains to be seen whether these food policy initiatives will prove a continuing trend and to what extent integrated approaches will be also implemented in practice, i.e. whether these efforts have moved beyond paper realities. The study concludes that one of the main challenges would be to accompany local governments in addressing food issues more holistically, applying a food systems approach, by intervening in a broader range of policy domains. Another recent study on Germany (Doernberg et al., 2019) built a systemic approach aimed at identifying effective ways to implement urban food strategies, understanding mismatches between instruments and different policy domains, levels and administrative units (e.g. at the urban-rural interface), and designing of new policy instruments. The study applied a “farm to fork” approach and showed that although German cities were not visible among the pioneering cities in many international studies and practice reports about urban food governance and policy, they started to address food issues quite early even if they are not formalized or labelled as urban food policies. However, the research also showed that more knowledge about the effectiveness of the different food policy instruments and appropriate mixes is required for a targeted choice of measures and instruments. Hence, the authors state that future research would benefit from linking questions of food governance with policy instruments, examining more systematically why certain instruments are chosen and how this is related with the governance capacities of cities, or whether there are differences in the formulation and implementation of urban food policies between cities that can be explained by the economic, planning and political system.

Another study on Spain (Vara Sanchez et al. 2021) stressed the importance of involving Civil Society Organizations (CSOs) in the design of effective urban food policies through a co-production process that helps shaping urban food policies by access to situated knowledge, expertise, and training in the form of diagnosis or city-to-city exchanges. Despite a growing trust between CSOs significant barriers remain with regards to political, administrative and technical aspects, as well as a series of limitations to establishing collaborations, including a wide diversity of actors (particularly farmers), managing expectations and showcasing impact. These limits make urban food policies still unstable, complex and always unfinished processes.

These new research trends have involved other regions of the world. For example, a recent study on South Africa (Kushitor et al., 2022) assess 91 food policies across 8 domains (agriculture, environment, economic development, land and land reform, health, education, and social protection), highlighting that policy formulations continue to exist in silos offering few tangible mechanisms to address inter-linked, systemic issues. Therefore, consolidating and reorganizing policy around a “food goal” is essential to ensure policy alignment and coherence, also through effective monitoring and evaluation tools that address the root causes of the systemic failures and the interconnection of factors that underpin sustainable and healthy food systems. In addition, the authors suggest that by actively engaging the existing commitments to the SDGs would help draw these stated international commitments together to meet the constitutional duty to food rights through an overarching food and nutrition security law.

Other authors (C40 Cities et al., 2019; FAO & RUAF, 2016; Forster, 2019; Moragues-Faus, 2021; Rikolto 2019) also focused their studies on the importance of cities' networks and alliances to foster food systems transformations at the local level. A recent study (Moragues-Faus, 2021) sought to explore the aims, activities, structures and mechanisms activated by this complex landscape of networks. Results demonstrate key differences across the board related to their involvement in global and national policy debates, level of political commitment, types of member cities, expertise on specific topics, approach to urban food policies and forms of decision-making. In addition, the analysis reinforces the importance of developing more flexible understandings of policy-making processes. Efforts to align policies have mostly focused on creating policy coherence across sectors such as economic development, environment or health. Yet, the authors argue that progress to transform food systems might be limited due to the lack of systems thinking in policy making (Willett et al., 2019), this time, concerning its cross-scalar dimension. While translocal networks exhibit a unique capacity to elevate urban food policies to national and international policy arenas, the actual vertical integration of food policies across these scales is still limited and the role of networks in this remit is only just emerging. To date, existing networks are partly responsible for an unprecedented scaling-out of urban food policy action across the globe. Hence, the authors highlight that as urban food policies become the new norm, the challenge for this new infrastructure is how to scale-up urban interventions by further aligning them with broader food policy debates to improve their resilience and transformative capacity. However, despite these networks have offered useful platforms and resources to share best practices from European municipalities (EUROCITIES 2020), neither extensive surveys nor EU-wide reports have been yet conducted to grasp the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on urban food security in Europe. The lack of systematic and comparable data disaggregated at the city level has been identified as a prominent challenge to advance the urban food agenda and support policy interventions (FAO, 2019; FAO & The World Bank, 2020). Bridging this knowledge gap is as a key enabler for the development and delivery of urban food policies (IPES-Food, 2017).

At the Italian level, several studies on local food policies have been published in the past years (Dansero et al., 2019; Marino, Antonelli, et al., 2020), analysing the experience of some cities in promoting new models of governance such as the Food Policy Councils (Calori, 2015), in assessing the potential of shorter food supply chains and alternative food networks (Marino, 2016; Marino & Cicatiello, 2012) and in managing food waste (Fassio & Minotti, 2019; Fattibene, 2018). Addressing these issues is particularly relevant for the peninsula, that even before the crisis, was coping with food and nutrition challenges, especially in terms of soil degradation, water usage and Green Houses Gas emissions (Barilla Center for Food and Nutrition, 2019)), the use of synthetic pesticides in agriculture and antimicrobial resistance in farms. For instance, studies (Rete Rurale Nazionale 2020) have shown that in Italy in 2018 the level of resistance to the main categories of antibiotics for the 8 pathogens under surveillance was higher than the EU average. Additionally, other studies and polls reveal that the number of children and adults suffering from overweight and obesity is on the rise (Istituto Superiore di Sanità, 2016), while the country still experiences high levels of food waste (ISPRA, 2019; Waste Watcher, 2019)and food poverty (IPES-Food, 2017).

Against this backdrop, the Covid-19 pandemic has produced huge impacts particularly on the most fragile groups of the population (FAO, 2020c), as confirmed by the FAO-led survey, which has involved more than 850 respondents particularly from Latin America, the Caribbean and Africa (FAO, 2020b). Other studies have focused on the response undertaken by some countries like China (Fei & Ni, 2020; Zhong et al., 2021) or individual cities such as New York (City of New York, 2020a; City of New York, 2020b). In Italy, the Covid-19 pandemic has caused dramatic adverse effects on food and nutrition security, for instance triggering high levels of food poverty (Action Aid Italia, 2020). Some surveys and studies have already tried to identify some key challenges as well as mitigation strategies adopted by Italian local authorities (Curcio & Marino, 2022; Marino, Mazzocchi, et al., 2020). Nonetheless, there is a lack of systemic studies able to effectively address the role and importance attached by local policy makers to urban food policies, as well as analysis that allows to identify the dynamics that lead to sustainability transformation at the urban level.

Furthermore, in Italy the panorama of urban food policies has had a significant increase since Expo 2015, of which the signing of the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact was one of the main legacies. Although a number of research groups have studied the Italian experiences focusing on individual cities or territories, however, there is no capillary vision capable of organically representing the evolution of food-related initiatives in Italy, even beyond the cities that have signed the Milan Pact. This last aspect is particularly important to verify the effective taking charge of the food issue by the cities. For these reasons, although focusing only on the top-level officials and policy makers may present some biases and limitations, the research helps to understand the drivers behind the adoption of sectoral food policies in Italy, while seeking to provide a preliminary categorization of these approaches.

Therefore, the aim of this study is to analyse and discuss the role of urban food policies in Italy, looking at data collected from representatives of 100 municipalities across Northern, Central and Southern regions. The paper addresses the initiatives and policies adopted at the local level, the main obstacles encountered, the role of national and international city networks, the impact of Covid-19 on urban food security and the cities' responses to the challenges brought by the Covid-19 pandemic. The intention of the authors was not to address each of these aspects in depth, but to use them as keys to understand the issue of the emergence of a local urban food policy or a similar process. By following this approach, the article aims to identify potential models of urban food policies as a structural component of a broader urban agenda, by tackling two important questions:

-

1.

Is it possible to launch urban food policies, even in the absence of fully formalized and institutionalized settings and structures?

-

2.

Even in those contexts with a low level of formalization what are the main sectors where food policy initiatives or projects are carried out and generate the highest level of satisfaction among local policy makers?

To address these issues, the article is structured as follows. Section 3 presents the methodological approach rolled out in the research, focusing on the different phases followed to produce the Cluster Analysis (CA) and the modelling of urban food policies. Section 4 presents the Results of the survey submitted to the 100 Italian cities, with the aim to present the modelling of urban food policies. Section 5 provides a thorough discussion of the analysis, focusing on the common trends raising from the analysis of the 7 clusters identified in the research. Finally, section four draws some conclusions and policy recommendations, by presenting some issues where future research on urban food policy should try to focus on.

3. Methodology

The paper's methodology is based on different steps. To begin with, the research team designed the questionnaire that was submitted to the representatives of Italian municipalities. As a following step, a database with all the different answers was produced. After that, the authors conducted a Cluster analysis of the questionnaire that was functional to analyse the different results and to produce a modelling of urban food policies. Fig. 1 below visualizes the logical framework followed by the authors in the paper.

Fig. 1.

Outline of the methodology followed in the paper.

3.1. Questionnaire

As stated above, after designing the questionnaire, this was delivered to 100 Italian municipalities between June and September 2020 followed by a cluster analysis aimed at discussing and assessing the main findings of the survey, as well as identify models of urban food policies in Italy that are developed in the context of broader urban development agendas. First, a semi-structured questionnaire was designed to collect data. It included qualitative, open-ended questions, as well as and quantitative questions with nominal, ordinal and scale measures. The target population included representatives of the Local Government of Italian cities. More specifically, Mayors, Deputy Mayors, Assessors, as well as other public officials dealing with urban food policies were interviewed. Repetitions and inconsistencies were carefully avoided. The questionnaire was organized into different sections, aimed at covering all topics of interest. At the beginning, respondents were required to express their level of awareness and perception of importance of the SDGs, as well as to describe the initiatives launched to achieve them. Afterwards, respondents had to answer a few questions about the urban food policies set up in their cities, their goals, their scope, the stakeholders involved, the analyses carried out ex-ante and ex-post, as well as the barriers that prevent launching new initiatives. The focus was then shifted to the cities' networks and respondents were submitted some questions about their membership, level of involvement, as well as perceived advantages of being part of a network. Finally, some questions about the impact of Covid-19 pandemic on urban food systems were prepared. Last but not least, a few demographic and classification questions were included to profile respondents.

The fieldwork was conducted through telephone interviews, by means of the Computer Assisted Telephone Interviews (CATI) methodology, by IPSOS, a multinational market research and consulting firm. This type of interview was deemed the most appropriate approach to contact representatives of the local government, mainly due to the limitations and restrictions to carry out face-to-face interviews during the Covid-19 pandemic period. The sample consisted of 100 representatives of the local government of Italian towns, representing a population of 9,252,506 individuals (see Fig. 2 ), representing 15.7 % of the Italian population reported the 1st of January 2022. During the sample definition phase, towns were selected on the basis of geographical area, market size, as well as membership in a network of towns, to grant a good coverage. Given that a total of 329 Public Officials were invited to take part in the study, the response rate was about 30 %; this is a high figure, since the typical response rate for this type of target is almost 10 %.

Fig. 2.

Map of the cities analyzed.

As far as geographical location is concerned, two macro-areas were taken into account: i) Northwest and Northeast; ii) Centre, South and Islands. Moreover, in terms of market size, three classes were considered: i) cities up to 30,000 inhabitants; ii) cities from 30,000 to 100,000 inhabitants; iii) cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants. Finally, towns were targeted according to: i) membership to at least one city network (i.e. Patto dei Sindaci, Comuni Virtuosi, Città Creative UNESCO, Milan Urban Food Policy Pact or C40); ii) lack of membership.

Table 1 describes the parameters used for the comparison, giving an indication of the indexing methodology towards the Likert scale from 0 to 5. These scales on the one hand are deeply anchored to existing literature on urban food policies, as they look at several dynamics such as the different kinds of policies activated by urban food policies (Kushitor et al., 2022)), the level of policy integration and mismatches (Doernberg et al., 2019; Sibbing et al., 2021) the role played by city networks (Moragues-Faus, 2021) at the European and non-European level. On the other hand, they try to propose an innovative approach based on a set of indicators that are tailored to the Italian context and seek to grasp the immediate effects caused by the Covid-19 pandemic on Italy's urban food security.

Table 1.

Description of variables used for modelling food policies.

| Parameter | Survey question(s) | Methodology |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental-oriented | The urban food policies you have implemented or are you planning to implement which of the following objectives are priority? | The survey provided that the interviewee could assign two priority levels (high and medium) to each dimension (environmental, economic and social). Therefore, the responses related to the high priority level were weighted as a single unit, while the responses related to the medium priority level were weighted with the value of 0.5. The scores obtained were related to the number of cities belonging to each cluster and subsequently indexed on the scale from 0 to 5. |

| Social-oriented | ||

| Economic-oriented | ||

| Policy integration and innovation | Would having interdepartmental/inter-departmental structures with dedicated coordination staff be a realistic solution for your reality? | The survey provided that the interviewee had five ways of answering. The scores were obtained through the following weighting model:

|

| Propensity to gather data and information | With reference to the urban food policies that you have implemented, have you carried out preliminary analysis of the projects to map and understand the areas on which to intervene? With reference to the urban food policies that you have implemented, have you already carried out or do you intend to carry out ex-post impact analysis of the projects to provide an account of what has been done? |

The parameter expresses the average of the scores indexed on the scale from 0 to 5 of two questions. Regarding the first question, the interviewee had three methods of answering available, which were weighted as follows:

Regarding the second question, the interviewee had four response modes available, which were weighted as follows:

|

| COVID-19 impacts | In your opinion, to what extent has COVID-19 impacted the four dimensions of Food Security defined by FAO? | The parameter represents a synthesis of the answers obtained with respect to the four dimensions of food security: access, availability, use and use and stability. The overall number of responses of the four dimensions was related to the number of clusters and subsequently indexed with respect to the 0–5 scale. |

| Networking | If you were to judge the level of active participation of his municipality in the network(s) it belongs to, you would define it…. In your opinion, to what extent can belonging to a network represent an additional stimulus to implement urban food policies? |

The parameter expresses the average of the scores indexed on the scale from 0 to 5 of two questions. Regarding the first question, the interviewee had four methods of answering available, which were weighted as follows:

Regarding the second question, the interviewee had five response modes available, which were weighted as follows:

|

3.2. Cluster analysis

To assess the findings of the questionnaire, the authors opted for a CA (Kaufman & Rousseeuw, 2005), a very well-established explorative statistical technique, which can be defined as a way of grouping (multivariate) observations such that units in the same group look similar and units in different groups are heterogeneous, according to some standard metric.

Given a data matrix X = [x ik], i = 1, …, n; k = 1, …, p, the first step of the analysis involves calculating a distance or a dissimilarity matrix, which is the typical input for any clustering algorithm. In our case, we had qualitative variables; in particular, two of them (Question no. 2 “In your territory, what SDGs would you consider as a priority?” and Question no. Q27 “What are the main obstacles to implement urban food policies in your territory?”) allowed for multiple dichotomous responses (17 responses for variable Q2, and 11 responses for variable Q27), whereas the remaining three required one closed response. As a result, our database consisted of a 100 × 31 matrix, with 28 dichotomous (Yes/No) variables, and 3 polytomous variables.

The nature of the data made it impossible to calculate a classic distance matrix, i.e. a n × n matrix (n being the number of units) D = [d ij] with generic entry expressing the distance between units i and j (i, j = 1, …, n). Therefore, the paper opted for a measure of proximity instead, by choosing the Gower's similarity coefficient (Gower, 1971), i.e., a similarity measure involving any type of variable; the original formula states that the similarity between units i and j is equal to:

| (1) |

where the indicator w ijk = 1 if, in the data matrix, both measurements x ik and x jk, relating to the kth variable are present, and w ijk = 0 otherwise. The quantity c ijk is the contribution that kth variable gives to the similarity between units i and j; in our application, in particular: a) for polytomous characters, c ijk = 1 if units i and j share the same category, c ijk = 0 otherwise; b) for dichotomous variables the rule is the same, but, in addition, w ijk = 0 if both x ik and x jk are zero (so reducing the denominator of the similarity, s ij (G)). Gower's index ranges from 0 (minimum similarity between the units) to 1 (maximum similarity).

Once Gower's similarity score s ij (G) was obtained, it was possible to find the corresponding dissimilarity measure, d ij (G), by simply putting d ij (G) = 1 − s ij (G) (Kaufman & Rousseeuw, 2005). The research used R software routine daisy in the cluster package, which gives as output the Gower's dissimilarity matrix D(G) = [d ij (G)].

The subsequent choice was, in some way, made compulsory by the fact the research team had at its disposal dissimilarities, and not distances - which typically constitute the basis for almost all the clustering algorithms. Therefore, the research employed the so-called k-medoids (also called PAM – Partitioning Around Medoids) technique: it differs from the much more employed k-means algorithm in that, while in k-means the center of a cluster is represented by a vector of means, in k-medoids the center is a vector describing an object belonging to the cluster, the medoid, which is chosen in a way to minimize the average distance (or average dissimilarity) between the medoid and all the other objects of the same cluster. Since it accepts a dissimilarity matrix as input, the k-medoids algorithm was our natural choice, by exploiting the function pam in R.

The final decision, regarding the optimal number of clusters, was taken basing on the silhouette (Rousseeuw, 1987) Defining the silhouette for unit i as:

| (2) |

where: a(i) is the average dissimilarity of unit i with the other units belonging to the same cluster, and b(i) is the lowest average dissimilarity between unit i and any other cluster, it is clear that s(i) will be high if unit i is “near” to its cluster (low a(i)) and “far” from other clusters (high b(i)), with a maximum of 1. Averaging this result on all the units observed, the (overall) average silhouette width, is a measure of how well the units have been clustered, for a given number k of clusters. It is clear, then, that the optimal number of clusters is the one for which the average silhouette width reaches its maximum.

4. Results

The current section combines the analysis of the main results collected and discusses them. In particular, the section is divided as follows. §4.1 provides the results of the cluster analysis by listing seven models of urban food policies in Italy. This paragraph is preliminary and helps framing urban food policies models before a transversal analysis of the seven clusters by dividing them into four main thematic areas (§4.2): i) types of policies; ii) policies' implementation; iii) role of cities' networks; iv) the impact of Covid-19. Finally, §4.3 describes in detail the features of the seven models of urban food policies developed through the assessment of seven variables and, afterwards. Please consider that in §4.2 (Transversal analysis per thematic areas) the percentages refer to the whole sample of cities, while in §4.3 (Modelling urban food policies) they refer to the sample composed by the cities belonging to each cluster/urban food policy model.

4.1. Identification of clusters

The table below (Table 2 ) outlines the seven clusters that resulted from the cluster analysis (§ 2.2). The table outlines the different criteria that were selected to model how Italian cities are shaping their urban food agendas, building on sustainability criteria. In particular, these criteria regarded the size of the population, their geographical location, the SNAI class, their political experience, the years of implementation of urban food policies and finally the SDGs identified as the main drivers for adopting urban food policies. Following the methodology, all these criteria were combined to create models of urban food policies in Italy that are developed in the context of broader urban development agendas.

Table 2.

Clusters identified.

| Label | The small traditionalists | The big traditionalists | The pioneers | The ruralists | The glocalists | The localists | The newcomers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension | 30,000-100,000 | 30,000–100,000 but also big cities with more 250,000 inhabitants (e.g. Genova or Torino) | 30,000–100,000 but also big cities with more than 250,000 inhabitants (i.e. Milan) | 30–100,000 but also with more 100,000 inhabitants (e.g. Ancona, Brescia) | 30,000–100,000 but also with more 100,000 inhabitants (e.g. Bolog,a Parma, Salerno) | 30,000-100,000, but also with more 100,000 inhabitants (e.g. Bergamo, Reggio Emilia) | 30,000–100,000 but also with more 100,000 inhabitants (e.g. Livorno, Padova) |

| Location | Northern Italy | North (80 %), and in the Northwest (60 %), | Northern Italy (50 %) and Southern Italy (25 %) | Equal distribution | Central and Southern Italy (50 %) but also in the Northeast (25 %) | Northern Italy (75 %) | North-East, Central and Southern Italy |

| Political Experience | 3–5 years | 3-5 years | Less than 3 years | 3–5 years | 3–5 years | 3–5 years | Less than 3 years |

| Years of Implementation | 3 years | 3 years | 3 years | 3 years | 3 years | 3 years | 3 years |

| SNAI classificationa | Pole and Belt | Pole | Pole and Semi-Peripheral (with distribution similar to the average) | Pole and Semi-Peripheral (with distribution similar to the average) | Belt | Poles and Peripheral | Belt |

| SDGs identified as priority | Health (SDG3), education (SDG4) and Climate change (SDG13) | Poverty (SDG1), Education (SDG4), Jobs creation (SDG8), Inequalities (SDG10) | Poverty (SDG1), Education (SDG4), Innovation (SDG9) and Sustainable Communities (SDG11) | Water security (SDG6), Education (SDG4), Sustainable Communities (SDG11) and Partnerships for the Goals (SDG17) | Poverty (SDG1), Jobs creation (SDG8), Sustainable Communities (SDG11) and Climate Change (SDG13) | Clean Energy (SDG7), and Sustainable Communities (SDG11) | Health (SDG3), Clean Energy (SDG7) and Responsible production & consumption (SDG12) |

SNAI stands for the National Strategy for Internal Areas. It is a national policy that attempts to foster territorial cohesion and development, through projects that aim at reducing marginalization and demographic decline of internal and rural areas in Italy. So ar the policy has identified around 72 areas, involving 1077 municipalities, with a population of more than 2 million inhabitants. For further information please cf. https://www.agenziacoesione.gov.it/strategia-nazionale-aree-interne/

4.2. Transversal analysis per thematic areas

4.2.1. Policies

Cities interviewed identified the support of shorter supply chains and local agriculture as the most satisfactory sector (14.4 %), followed by food donations and public canteens. On the contrary, interviewees indicated as major weaknesses the management of the local food sector, the sustainability of the food supply and the economic trend of the local food sector. Cities reported a scarce ability to intervene on exogenous factors that usually lie beyond the policy perimeter at their disposal or that are dependent on economic drivers and variables linked to the overall socio-economic trend.

Against this backdrop, the support towards local/zero km productions and the promotion of a balanced diet and a healthy lifestyle were identified as the main areas of intervention for urban food policies (both achieved the 20.6 %). These sectors were followed by the management of food waste (15.2 %), programmes to ease access to food and the promotion of agriculture with a low environmental impact (both 10.3 %). Conversely, cities attached little importance to the reduction or elimination of the use of plastic (1.8 %) and the creation of opportunities for collaboration between the various stakeholders in the food sector (4.2 %). These data testify a lack of trust or knowledge of the tools and places of deliberative participation in the context of urban food policies, largely considered instead as fundamental elements of the democratization of food systems (RUAF, 2019).

In addition, the research investigated which areas or sectors were or should be most directly involved in urban food policies. School canteens (11.4 %), local/farmers' markets and consumers' education (both 10.6 %) were considered the most important sectors. This data confirms how local administrators try to harness the synergies between the enhancement of local products and the promotion of balanced and healthy diets, on the one hand, and the fundamental role that school canteens and local markets play as components of the urban foodscape (Mazzocchi & Marino, 2019; Niebylski et al., 2014); on the other hand. Moreover, this proves that cities find it crucial to invest in the final stages of the supply chain, interpreting final consumption (and the relative awareness of consumers-citizens) as a lever to guide the agri-food system. This reflects a demand-oriented vision, which in an imaginary continuum between a model guided by a planned agri-food supply pattern and one oriented to the role of the consumer as the main driver of territorial agricultural transformations, is placed closer to the second.

In this context, the answers provided showed that the formalization of food policies is not considered as a conditio sine qua non to implement them, with 75 % of cities claiming that they have been carrying out food policies for the last three years. Looking at the seven clusters in more detail, except for the glocalists and the localists (where the percentage was still above 60 %), these trends were similar across all cities. Furthermore, if we combine these performances with Q8 – where school canteens emerge as the sole institutionally-driven sector with high levels of support – it is possible to claim that local policy makers have implemented different topics typical of food policies, even in the absence of comprehensive strategies. While these results are a good sign per se, meaning that it is possible to implement urban food policies even in the absence of systemic approaches, they also prove the lack of a systemic vision across local administrators.

If we look at the “penetration degree” of different policies, meaning the frequency of the specific policy indicated as a priority, it is clear that the main ones – school canteens and food markets (65 % and 50 %. respectively) – were linked with a direct public intervention. The following priorities were linked with social and environmental aspects: the reduction of food waste and its re-use, followed by economic activities taking place at the urban and peri-urban level, the linkages between producers and consumers and the valorization of local supply chains. All these topics ranged between 20 % and 30 %, whereas other issues were considered as less relevant. The highest differences across clusters were registered between the small traditionalists and pioneers, whereas for the localists' priorities are mainly concentrated towards institutional topics such as school canteens, food markets. Moreover, the newcomers attached the highest importance to food canteens, whereas those in big traditionalists and ruralists identified as a priority local supply chains and economic activities. Finally, the glocalists were more focused on environmental and social aspects of local supply chains.

4.2.2. Implementation of urban food policies

The most successful experiences of integrated urban food policies show that the creation of horizontal interdepartmental structures is key to foster change. The cross-cutting nature of food-related policies implies a stronger degree of coordination among all those actors that are directly or indirectly working on food at the municipal level. However, current literature confirms that it is not easy to support these dynamics within the organizational routines of local institutions (Barnes et al., 2018). Against this backdrop, when asked if they already have or consider feasible to launch such horizontal interdepartmental structures, almost the majority (45 %) of all cities interviewed considered it pretty or very realistic to implement them. In particular, a closer look at the different clusters shows that the glocalists (29 %) and the small traditionalists (21 %) identified as very realistic that they would implement those structures, whereas no localist opted for this option, although the vast majority (63 %) identified as very realistic that they may implement these changes. In addition, slightly more than one city in four (27 %) declared that it is not very realistic that they will launch new horizontal interdepartmental structures, with the highest performances registered for the small traditionalists (57 %) and the newcomers (33 %).

In this context, a significant number of cities (15 % of the total sample) stated that they have already implemented such structures within their administrations, with the highest numbers concentrated in the group of pioneers (36 %) and ruralists (23 %). Finally, very few cities overall (5 %) considered it very unrealistic the implementation of these changes, and the highest skepticism was encountered by cities belonging to the localists (13 %), the ruralists (8 %) and the big traditionalists (7 %).

A considerable majority of cities interviewed (57 % of the total) stated that they have human resources that can implement urban food policies. The clusters' analysis shows that the highest levels in this sense were registered among the pioneers (82 %), the localists (63 %) and ruralists (62 %). Conversely, the lowest performances were recorded for big traditionalists and the small traditionalists where almost six out of ten cities (58 % and 57 % respectively) reported the lack of these resources to be employed to implement these kinds of policies. More precisely, when asked about what Office or Department (Assessorato) would be responsible for implementing urban food policies, the most frequent options identified by the interviewed cities were the Agricultural Department1 (especially for the small traditionalists and the glocalists), the Youth and Social Policies Departments (with the highest scores registered among the newcomers and the pioneers respectively), and the Environmental Policies Department (the glocalists). Against this backdrop, it is interesting to note that a significant number of cities attached a strong importance to the need to set up a proper inter-departmental office to design and implement these policies, with the highest consensus recorded for big traditionalists, the glocalists and the localists. The analysis of this data confirms that urban food policies continue to be considered as something belonging to the sphere of agriculture, social inclusion and environmental policies. However, the fact that inter-Departmental offices were included in the top 5 list is a very promising sign. A consistent number of cities have started to acknowledge that the cross-cutting nature of urban food policies requires proper changes at the political and bureaucratic levels.

The survey analyzed the capacity of cities to undertake preliminary studies about their local contexts, with almost two thirds (63 %) of 100 cities stating that they have undertaken them. However, a significant number of them (46 %) acknowledged that there is wide room for improvement in this field. The best performances regarded cities in the small traditionalists (29 %) and ruralists (29 %), followed by the pioneers (18 %) and big traditionalists (17 %), whereas no glocalists (47 %) and ruralists (46 %) have implemented these kinds of preliminary assessments. These data show that there is a big potential for data improvement at the cities level for what regards urban food policies.

The availability of data is crucial to give both ex ante and ex post assessment to design as well as amend urban food policies. However, the vast majority of cities interviewed (72 %) claimed that they have not launched such assessments, although almost one in five cities (18 %) stated they are ready to do so, while 11 % of them replied that they have no intention to launch these processes in the foreseeable future. Among the least motivated cities, there were the glocalists (18 %), newcomers (17 %) and the small traditionalists (14 %). In this context, it is striking to note that cities in the glocalists and the small traditionalists were also those that have already undertaken a precise assessment of their urban food policies, with 47 % and 43 % of cities respectively, followed by the localists (38 %). Conversely, the newcomers registered the lowest performance, with only 13 % of respondents claiming that they have undertaken these ex-post evaluations.

When asked about the type of purposes addressed by implemented or future urban food policies, the majority of cities identified environmental purposes as the main ones. In this group, the majority of responses came from the newcomers (26 %), the glocalists (20 %) and ruralists (13 %), whereas the localists showed the lowest share (8 %). Environmental goals were followed by social ones, with the latter playing a crucial role for cities in the small traditionalists (22 %) and for big traditionalists and the newcomers (17 % each). Interestingly to note, no city indicated economic purposes as the main driver for current or future urban food policies.

The outbreak of Covid-19 exposed Italian cities to many forms of vulnerabilities and pushed mayors and local policy makers to implement a series of policies and interventions to alleviate the impact of the crisis. In this sense, the top-3 interventions launched at the city level regarded policies to support citizens in need either through financial support or by delivering food packages at home and this was particularly the case for the localists and small traditionalists. Additionally, several cities undertook a series of initiatives to support alternative food logistics to support food distribution services, in particular among the glocalists, the small traditionalists and the pioneers. Finally, glocalists, pioneers and newcomers implemented programmes and projects to support responsible consumer behaviours even during lockdown. Only two cities addressed projects to monitor food prices and to deliver school meals at home through alternative models, showing that these issues were not considered a key priority by local policy makers – a worrisome signal as recent studies highlighted that the closure of schools and interruption of school meals deeply affected the poorest households in Italy, exposing children to food insecurity and lack of adequate nutrition (Save the Children, 2020).

4.2.3. The role of city networks

The interviews revealed a few interesting insights about the participation and role of city networks. 61 % of the 100 cities are part of the Patto dei Sindaci (Covenant of Mayors); 29 % of the Comuni Virtuosi grouping; 12 % of the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact; 10 % of the UNESCO Creative Cities Network of Gastronomy; 1 % of C40. When asked about the level of engagement in city networks, 28 cities reported a “limited” participation (especially among the newcomers, the localists and big traditionalists), one city as “no” participation. Among the reasons for the low engagement, the lack of personnel was by far the main reported reason (42 % of respondents, 38 % of which among the newcomers, 25 % among the glocalists, 19 % among the big traditionalists), followed by the lack of coordination and guidance (16 %), lack of budget (11 %) and the perception that the network plays only a formal, rather than substantial, role (11 %). The engagement in a city network could favor the implementation of urban food policies to a “high” and “fairly high” level according to 52 % and 41 % of cities, respectively. This confirmed the finding that the exchange of knowledge and practices is pivotal to support the adoption and effective development of urban food security strategies and policies (Filippini et al., 2019).

4.2.4. The impact of Covid-19

Considering the four dimensions of food security, as defined by FAO (FAO, 2008), it emerges that the food utilization dimension was the most impacted by Covid-19 (with 56 % of all cities interviewed reporting a “high” or “fairly high” impact), especially in terms of good care and feeding practices, food preparation, diversity of the diet and intra-household distribution of food. In fact, more than half (56 %) of cities registered fairly high or high impacts, while only 13 % reported low or “no impact”. In detail, the localists were those with greater impacts on food utilization (3 out of 4 cities report fairly high or high impacts), followed by the small traditionalists (64 %) and the newcomers (63 %).

As for food access, the survey showed that the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic was almost evenly distributed over the various possible modalities (from “no impact” to “high”). In this sense, those cities majorly involved in programmes dealing with poverty reduction as well as social and economic inclusion reacted better to the crisis. Only the small traditionalists and, to a lesser extent, the newcomers, reported high impacts related to access to food. This evidence can be linked to a greater predisposition that these cities have towards global issues more related to environmental and energy aspects. In confirmation of this interpretation, it emerged that the big traditionalists, more involved in local issues including poverty and economic and social inequality, were those that found less criticality regarding access to food. In fact, 58 % of them report a “low” or “no impact”.

Regarding food availability, the Covid-19 pandemic had a limited impact, with two thirds of cities reporting no or low impact. The small traditionalists belonged to most affected group, as 35 % of cities reported a fairly high or high impact. The newcomers followed in this particular ranking, showing a correlation between the problem of access and availability of food, whereas the localists suffered smaller impacts. These results are in line with a study reporting the opinion of about 80 scholars and experts on the impacts of Covid-19 in Italy (Marino, Antonelli, et al., 2020), as well as with other surveys conducted by FAO in 2020, involving more than 850 respondents from across the world (FAO, 2020b). Additionally, although the survey showed that some families initially reacted to the crisis through food hoarding and stockpiling, this had only a limited effect on the availability of raw materials (cumulatively, only 5 % of cities considered them as first level impacts). In this sense, it is no coincidence that this data is in line with the performances on food availability, that registered the lowest impact. Therefore, it can be deduced that the greatest difficulties concerned the retail phases and the shortage of some goods in the points of sale, while the agricultural and production phase has withstood the shocks deriving from the various restrictions related to the lockdown.

Finally, in terms of food stability more than half of the 100 cities interviewed (55 %) claimed they had low or “no impact”. The glocalists and the newcomers reported the greatest impacts, grouping respectively 41 % and 42 % of cities with fairly high or high impacts. Conversely, pioneers, included cities that have suffered less the impacts of Covid-19 to a lesser extent in terms of stability in the supply of food.

All in all, the survey clearly highlighted that the shutdown of local food markets (including famers' markets) as well as the difficulties to provide access to food for families in need had the greatest first level impact (respectively, 26 % and 29 % of all cities analyzed). The various waves of the Covid-19 pandemic have caused huge economic slowdowns, triggering dramatic increases in poverty, with ISTAT (ISTAT, 2021) reporting in 2020 a peak of people falling into absolute poverty in Italy since 2005.

4.3. Modelling urban food policies

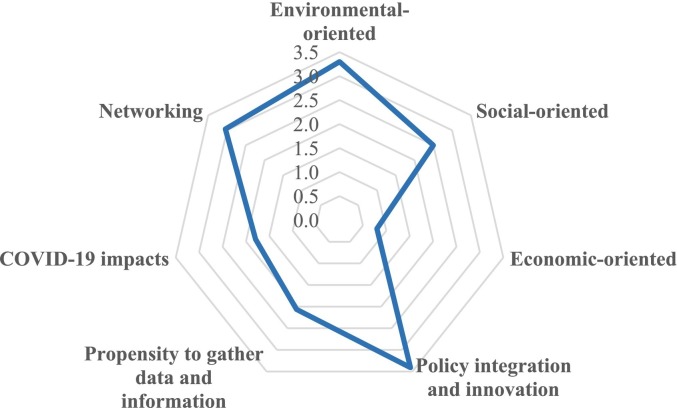

In this section, the results of the analysis have been reorganized to identify patterns of city behavior in relation to food policies, based on the seven clusters identified. For this purpose, seven variables have been compared: three of them concern the orientation of objectives with respect to the environmental, social and economic dimensions; policy integration and innovation; the propensity to collect data and information for policy monitoring; the impacts of COVID-19; the capacity to network; and the ability to manage food policies. The scores of the seven parameters have been calculated by reporting the results of the survey on a scale from 0 to 5. The graph in Fig. 3 represents the synthetic restitution of the results of the food policy modelling parameters for the seven identified clusters. The following graphs (Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig. 7, Fig. 8, Fig. 9, Fig. 10) , provide the results of the analysis per single cluster.

Fig. 3.

Scores of the seven clusters with respect to the variables identified for the modelling of food policies.

Fig. 4.

Scores of the Small Traditionalists.

Fig. 5.

Scores of the Big Traditionalists.

Fig. 6.

Scores of the Pioneers.

Fig. 7.

Scores of the Ruralists.

Fig. 8.

Scores of the Glocalists.

Fig. 9.

Scores of the Localists.

Fig. 10.

Scores of the Newcomers.

4.3.1. The small traditionalists

The small traditionalists usually have a consolidated process towards food policies, as this is the Cluster with the highest rate of cities reporting that these policies or initiatives have been implemented for more than three years. These policies have very clear local purposes, and they are strictly linked with policies directly managed by local authorities such as canteens, food markets or the reduction of food waste. For all these policies, interviewees showed a high degree of satisfaction, while they acknowledge that more room should be devoted to social issues linked to citizens' engagement, the promotion of healthier diets and access to food. These answers are in line with the profile of these cities, as these local policy goals are meant to address global environmental objectives. Against this backdrop, it seems that food policies are implemented through ordinary and traditional structures, whereas the creation of ad hoc offices is not considered realistic or suffers from the lack of dedicated personnel. The Agricultural Department is considered the most proper actor to implement these policies, and this is in line with the fact that cities indicated financial problems as the main obstacle for implementing urban food policies. Moreover, in terms of data and information available, the small traditionalists have the highest number of preliminary studies conducted (29 %), with cities envisaging also a dedicated ex-post analysis of policies implemented. Finally, Covid-19 does not seem to have impacted in a homogenous way on these cities, although this Cluster presents the highest percentage of impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on food access (29 %). The same trend regards the other dimension of food security such as food availability (with 35 % reporting a high impact, against 43 % saying it had “low” or “no impact”), food utilization (with 64 % reporting a high impact, against 29 % saying it had “low” or “no impact”) and food stability (with 21 % reporting a high impact, against 65 % saying it had “low” or “no impact”).

4.3.2. The big traditionalists

Together with those policies that are traditionally under the responsibility of local policymakers (e.g. school canteens or food markets), cities belonging to this cluster tend to prioritize the reduction of food waste. The “localized” profile of these cities is complemented by other policy goals linked to the support of local food chains, as well as the traditional and local retailers. The reduction of food waste is the sector that raises the highest level of satisfaction, but other issues such as the valorisation of local food chains, proximity agriculture and citizens' education play a big role as well. Moreover, in line with the profile of the Cluster, the main goals of urban food policies are particularly linked to environmental goals. Only two cities in this cluster present dedicated structures to undertake food policies, while almost 60 % does not have specific personnel to deal with these policies. However, in most cases (around 60 %), policy makers interviewed stressed the need to implement these innovative structures. Among them, they indicate as implementers traditional actors (e.g. the Department for Productive Activities or the one on Social issues), although in the majority of cases, they foresee the creation of a new inter-departmental structure. In this sense, it does not come as a surprise that these cities identified as main barriers for the implementation of urban food policies the lack of personnel, the electoral cycles, the lack to effectively communicate this to citizens. Only a minority of cities have undertaken ad hoc accurate studies and a vast number of cities have declared that there is big room for improvement to increase the data and information needed to implement urban food policies. The same trends were registered for ex post assessments, with a limited number of cities declaring that they have implemented these studies. Against this backdrop, the big traditionalists, more involved in local issues including poverty and economic and social inequality, are those that have found less criticality regarding access to food. In fact, 58 % of them report a low or no impact. To counter the effect of the Covid-19 pandemic, cities undertook several initiatives such as financial support to families in need, the distribution of food aid and the revision of food logistics to properly redistribute food.

4.3.3. The pioneers

Despite most cities have been elected less than three years ago, this cluster also includes the city of Milan, a pioneer of urban food policies in Italy. The interviewees revealed that urban food policies are part of a consolidated process, since in most cases they have been launched more than 3 years ago. These policies tend to address issues (e.g., school canteens, food waste, citizens' education and food markets) that are deeply rooted in local needs and that are directly managed by local public authorities. The cities interviewed showed pretty good levels of satisfaction for those policies and initiatives that contributed to reduce food waste, support local food chains, citizens' education towards a more sustainable education, as well as the management of school canteens. According to local policy makers, these local urban food policies contribute to addressing global environmental issues. Interestingly to note, cities interviewed have already implemented inter-departmental structures to manage these policies, and a very high number consider it “very realistic” or “pretty realistic” to handle them rather than using traditional policy mechanisms. This is also facilitated by the fact that these administrations consider they have dedicated staff to undertake these policies. In these contexts, these cities identified the Social Department and the Agricultural one as the main responsible to tackle with these policies, although many acknowledged that their cities are coping with several other priorities as well as with a lack of budget, and training for their staff. In terms of data availability and knowledge, most cities stated that there is a huge room for improvement with limited ex-post analyses undertaken so far, but with a strong willingness to do so in the near future. Covid-19 has had a mixed impact of food security in these cities. First, it impacted considerably to food access and food utilization. As for the former, more than two thirds of cities claimed that the Covid-19 pandemic has impacted “fairly high” (50 %) or “on average” (17 %) on food access. Second, in one quarter of cases (25 %) cities registered problems in food utilization and in 17 % of cases they said Covid-19 hit “fairly high” on food access. Third, cities in this cluster highlighted that Covid-19 had a “low” (17 %) or “no impact” (42 %) on food availability and “low” (25 %) or “no impact” (42 %) on food stability. Therefore, to tackle the impact of the crisis on food, cities in this Cluster have given financial support to families in need, for instance through food deliveries or by re-designing food logistics to support the distribution of food.

4.3.4. The ruralists

The local policymakers interviewed showed pretty good levels of satisfaction for those policies and initiatives that contributed to reduce support local food chains, educate citizens towards a more sustainable diets and tackling food waste. According to local policy makers interviewed, these local urban food policies contribute particularly to address global environmental issues. Interestingly to note, while 16 % cities interviewed stated that they have already created inter-departmental structures to manage these policies, more than a quarter stressed that consider it “very realistic” (12 %) or “pretty realistic” (14 %) to handle them rather than using traditional policy mechanisms. This is also facilitated by the fact that these administrations consider they have dedicated staff (62 %) to undertake these policies. In these contexts, these cities identified the Environmental Department and the Social Policies one as the main responsible to tackle with these policies, although many acknowledged that their cities are coping with lack of budget, personnel as well as proper training for their staff. In terms of data availability and knowledge, no one has conducted preliminary analyses whereas 54 % of cities stated that there is a huge room for improvement. In addition, despite of the fact that only few cities have undertaken accurate ex-post analyses so far (23 %), there is a strong political will (54 %) to do so in the near future. Covid-19 has had a mixed impact of food security in the cities belonging to this cluster. First, the Covid-19 pandemic impacted considerably on food access, with cities claiming that it has impacted “fairly high” (31 %) or “a lot” (8 %) on this dimension of food security. Second, when asked about food utilization, several cities reported that Covid-19 hit “fairly high” (38 %) or a lot (15 %) on food use. Third, cities stressed that the crisis had an impact on food stability, with 15 % of cities saying it impacted “a lot” and 38 % of them reporting that the Covid-19 pandemic hit in “an average” way to food stability in their boundaries. Finally, these cities highlighted that Covid-19 had a “low” (38 %) or “no impact” (23 %) on food availability. Therefore, to tackle the impact of the crisis on food, cities in this Cluster have given financial support to families in need, for instance through food deliveries or by re-designing food logistics to support the distribution of food.

4.3.5. The glocalists

The cities of this cluster showed pretty good levels of satisfaction for those policies and initiatives that contributed to reduce support local food chains, the promotion of local products through the retail sector, the education of citizens towards a more sustainable diets and tackling food waste. Even in this case, the main reason for undertaking urban food policies is to contribute to deal with global environmental issues. In more than four cases out of ten, cities stressed that they consider it “very realistic” (26 %) or “pretty realistic” (17 %) to launch innovative mechanisms to handle these policies. This is also facilitated by the fact that these administrations consider they have dedicated staff (59 %) to undertake these policies. In these contexts, these cities identified the Environmental Department and the Agricultural Policies one as the main responsible to tackle with these policies, although many acknowledged that their cities are coping with lack of personnel, the coexistence with other political priorities and finally the lack of budget to undertake these policies and initiatives. In terms of data availability and knowledge, almost one third of these cities have already conducted ex ante analysis and around one in four cities stated that, although some studies have already been delivered, there is a huge room for improvement. In addition, in this cluster there is the highest number of cities that have undertaken accurate ex-post analyses so far (47 %), whereas more than one third (36 %) is ready to do so in the near future. In this context, Covid-19 has had a mixed impact of food security in these cities. First, the Covid-19 pandemic impacted considerably on food access: “fairly high” (29 %) or “a lot” (8 %) on this dimension of food security. Second, as for utilization, several cities reported that Covid-19 hit “fairly high” (35 %) or a lot (12 %) on food use. Third, cities stressed that the crisis had an impact on food stability, with 6 % of cities saying it impacted “a lot” and 18 % of them reporting that the Covid-19 pandemic hit in “fairly high”. Finally, these cities highlighted that Covid-19 had a “low” (47 %) or “no impact” (18 %). Therefore, to tackle the impact of the crisis on food, cities in this Cluster have given financial support to families in need, for instance through food deliveries or by re-designing food logistics to support the distribution of food.

4.3.6. The localists

Similar to the small traditionalists, although looking at them from a global perspective, localists consider food public procurement, local markets, consumers' education and local/neighbourhood shops as the main priorities. Moreover, as for the small traditionalists, these cities identify as the most satisfactory sectors the valorisation of short supply chain and proximity agriculture, the recovery and redistribution of surpluses and food donations, the management of canteen services, and the reduction of food losses/waste, while placing a great emphasis on the environmental aspects of policies and to a much lesser extent on the social ones. The localists also include the cities that consider it most realistic to have interdepartmental structures with dedicated coordination staff: two thirds of them consider it quite realistic and the same percentage of cities have or could have staff dedicated to urban food policies, showing a notable propensity for administrative innovation. Coherently with the socio-environmental vocation of the localists, they state that ad hoc intra-departmental coordination office (e,g, the department for quality of life and that for environmental policies) are/should be the administrative structures most involved in the urban food policy, despite the lack of financial and human resources still represents a key barrier. As for data and information available, the localists in five out of six cases have carried out preliminary studies and intend to carry out ex-post/impact analysis of the projects implemented. Covid-19 impacted food security above all in terms of food utilization (high impact for two thirds of the cities) while not significantly on the availability of food goods. Among the most critical issues encountered are those of a social nature, such as the challenges in guaranteeing access to food for people and families in difficulty (for three out of eight cities), the increase in prices for basic necessities and the hoarding of food (both for two out of eight cities).

4.3.7. The newcomers

This group includes cities whose policies are mainly targeting public health and well-being, sustainable energy and infrastructural and industrial innovation. Despite a fairly even distribution over the different sectors (the variance is the lowest among the seven clusters), these cities identify school canteens and consumer education as the main sectors to be addressed by food policies, although there is a fair preference for other sectors as well: local markets, management and recycling/reuse of food waste, and reduction of food losses. There is a notable coherence between what food policies should pursue and what the newcomers consider a priority, with a strong focus on policies to support school canteens. Among the sectors considered most satisfactory there are the collective catering service in schools (with the highest value among all the clusters), the reduction of food waste and the enhancement of the short supply chain and local agriculture, to be set up according to a logic strongly oriented towards environmental sustainability. More than 40 % of cities consider it realistic to have interdepartmental structures with dedicated staff, while 20 % stress they already have them. Nine out of twenty-four cities consider it unrealistic, despite the 54 % of the Cluster has/could have staff members dedicated to urban food policies. Coherently with SDGs identified as the main priority, these cities indicated as a priority area public health and well-being. Moreover, they believe that the department of education and youth policies should be or could be the one most involved in urban food policy. This is by far the highest result for this department compared to the other clusters, which should/could be supported by the department for agriculture and school canteens. Nevertheless, cities seem to be affected to the largest extent by insufficient budget lines and human resources: these two aspects are the most rated as main barriers for the adoption of urban food policies with respect to the entire group of cities of the sample. In terms of preliminary analysis, the interviewed have produced data and information to orient and design food policies interventions only in very few cases, whilst the half of them would like to improve them and the 38 % has not produced any analysis. As for the impacts of Covid-19, similarly to the localists, the main effects were experienced on food utilization (for two thirds of the cities it has produced moderately high and high impacts). Similarly, with the localists, nine out of twenty-four among the newcomers have reported impacts in guaranteeing access to food for people and families in difficulty, while six have reported local and urban markets closures.

5. Discussion: common trends and assessments

The article has discussed data collected from representatives of 100 municipalities across Northern, Central and Southern Italy. It has addressed the types of policies and initiatives adopted at the local level, the main obstacles encountered, the role of national and international city networks and the impact of Covid-19 on urban food security. It followed a double-layered methodology, first with a questionnaire submitted to local policy makers between June and September 2020 and second by undertaking a cluster analysis that resulted into seven clusters of cities. By doing this, to the best of our knowledge, the study aimed at filling a research gap in current literature, as it is the first large-scale survey on urban food policies that has managed to involve 100 Italian municipalities. The paper has attempted to identify models of urban food policies that are already being developed within broader urban development agendas.

Although all seven clusters analyzed present differences and specific traits, the obtained results allow to profile cities across six main common denominators. First, and this does not come as a surprise, all clusters highlight that stakeholders interviewed have identified as priority areas for urban food policies some specific topics that are traditionally directly managed by local policy makers and administrators, such as school canteens, food markets, the support and valorization of local food chains, the reduction of food waste and the education of consumers towards healthier and more sustainable diets. These sectors are not only identified as the main ideal areas where urban food policies should focus on, but they also raise the highest level of support and satisfaction from the local policymakers interviewed. These findings confirm why the vast majority of studies conducted in the past years on urban food policies have concentrated on particular sectors such as public food procurement (Sonnino, 2009), food waste analysis and reduction (Fattibene et al., 2020; Franco & Cicatiello, 2021), urban agriculture (Halvey et al., 2021), social inclusion and equity (Cohen & Ilieva, 2020; Reisch et al., 2013) or food donations (Berti et al., 2021; Filippini et al., 2019). A recent study conducted in the United States (Halvey et al., 2021) showed that although diverse in their approaches, many cities shared common elements of enacting urban agriculture policy through both governmental and non-governmental entities, authorizing policy instruments through different mechanisms, and covering a breadth of topics at varying levels of depth and restrictiveness/support.

Second, in all clusters the environmental dimension seems to be the main driver of urban food policies, confirming the trend that has marked the experience of other global cities with more established food policies like New York (Cohen & Ilieva, 2020), London (Parsons et al., 2021) or Milan (City of Milan et al., 2018) where the environmental dimension has been a powerful catalyzer for kicking off the adoption of a more integrated policy approach to food at the urban level. This does not come as a surprise, as the environmental footprint of urban food systems has been playing a key role also within cities' networks such as the MUFPP (Giordano et al., 2018) or the C40, that in 2019 issued a Food cities declaration with 14 mayors committing to reach a series of targets such as i) aligning food procurement policies to the Planetary Health Diet; ii) Supporting an overall increase of healthy plant-based food consumption in our cities by shifting away from unsustainable, unhealthy diets; iii) Reducing food loss and waste by 50 % from 2015 figures; and iv) increasing the engagement of citizens, businesses, public institutions and other organizations to develop a joint strategy to achieve a sustainable food transition in an inclusive and equitable way (C40 Cities et al., 2019).

Third, although ordinary structures and policy mechanisms still prevail in implementing urban food policies, a very significant number of cities across all clusters have declared that they have already implemented new inter-departmental structures and that they have already at their disposal dedicated staff to perform these policies. In the meanwhile, urban food policies are still considered as a prerogative of traditional actors and Departments such the Agricultural Department, the Environmental Department or the Social Policies Department. This finding confirms on the one hand that the implementation and institutionalization of urban food policies is a slow process (Giambartolomei et al., 2021; IPES-Food, 2017; Morley & Morgan, 2021; Reisch et al., 2013) with very context-related factors that can lead to a more or less formalization of these policies (Barnes et al., 2018; Doernberg et al., 2019). On the other hand, this reveals that although very few cities have implemented integrated and comprehensive urban food policies, the limited formalization of these processes does not impede local policymakers to carry out sectoral projects or initiatives that have an impact on urban food security. This trend has been confirmed by several studies in Europe such as Germany (Doernberg et al., 2019) where despite a very limited level of institutionalization, urban food policies have gradually emerged and consolidated across several cities. The findings are also consistent with Mattion et al. (Mattioni et al., 2022), to the extent that local authorities mobilize discursive, material and organizational tools to modify the dominant narrative around food and reorient material resources towards activities that support a new approach to food.

Fourth, all clusters showed that there are a series of obstacles that hamper the development of fully integrated urban food policies. Among them, the lack of dedicated budget and personnel, the lack of training for internal staff and in some cases the coexistence with other more pressing political priorities and even the challenge of electoral cycles are considered as the main barriers for carrying out effective urban food policies. All these barriers and constraints are well in line with several studies, reports or surveys conducted in the past years at the European (European Commission, 2019), global (FAO, 2020b) and Italian level (Dansero et al., 2019). These limitations may be further exacerbated by the impact of both Covid-19 and the war in Ukraine, with local municipalities confronted with very pressing and short-term challenges that may lead to a reduction of the resources traditionally allocated to implement food-related initiatives. Future research will need to be aware of these trends, as budgetary constraints may have significant impacts even for those municipalities with traditionally strong and well-institutionalized urban food policies. In this framework, the extent to which urban food policies are harmonizing and rationalizing existing policies connected with food is questionable. Despite Sibbing et al. (Sibbing et al., 2021) study shows that allocating resources, adopting officially the strategy, creating specific units, offices, and staff, are essential governance steps to “bring food policy beyond paper realities” (Sibbing et al., 2021), coherently with Minotti et al. (Minotti et al., 2022) for the case of Rome, the level of policy integration is still at the early stages in most cities of the sample. This issue is particularly relevant as it involves the institutional coordination of policies adopted by different departments, determining the success or failure of integrated urban food policies able to overcome a silos approach.

Fifth, data gaps are still predominant across all cities interviewed, with a limited number of ex ante or ex post studies conducted to analyse, design, implement, monitor, and adjust urban food policies. However, a considerable number of cities across all clusters stressed that either they have already implemented or are willing to do so in the near future. The lack of data and the weak empirical evidence registered at the city level represents a real problem for cities' engagement in urban food issues and is in line with a recent assessment conducted by FAO (FAO & The World Bank, 2020) on nine cities across the world. Cities still have a poor understanding and knowledge of many of the basic building blocks of food systems (e.g. knowledge of what consumers are eating, how much food is wasted, urban production systems, costs and capacities for scaling up investments). Collecting evidence and developing shared and effective metrics is thus crucial to address these gaps, identify priority areas of interventions, design, implement and monitor the real impact of interventions on the ground. In this context, studies such as the one conducted in Spain (Vara Sanchez et al. 2021) have demonstrated how crucial it is for local authorities to build up solid partnerships with academia, CSOs and informal groups. These emerging actors are essential to build to leverage and foster policy change, by creating new governance spaces that support mutual learning and unlearning, build trust, generate new collective knowledge, and create a shared collaborative framework.