Abstract

Background:

Decellularized extracellular matrix (dECM) is a non-cellular scaffold with various functions in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Elastin is related to tissue elasticity and scarless wound healing, abundantly found in lung and blood vessel tissues. We studied the characteristics of blood vessel-derived dECM (VdECM) and its effect in wound healing.

Methods:

VdECM was prepared from porcine blood vessel tissue. Weight percentages of elastin of VdECM and atelocollagen were analyzed. Migratory potential of VdECM was tested by scratch assay. VdECM in hydrogel form was microscopically examined, tested for fibroblast proliferation, and examined for L/D staining. Cytokine array of various growth factors in adipocyte-derived mesenchymal stem cell (ASC) media with VdECM was done. Animal wound model showed the wound healing effect of VdECM hydrogel in comparison to other topical agents.

Results:

VdECM contained 6.7 times more elastin than atelocollagen per unit weight. Microscopic view of 0.35% VdECM hydrogel showed consistent distribution. Compared to 3% atelocollagen, 0.35% VdECM showed superior results in fibroblast migration. Fluorescent microscopic findings of L/D assay had highest percentage of cell survival in 1% VdECM compared to atelocollagen. Growth factor expression was drastically amplified when VdECM was added to ASC media. In the animal study model, epithelialization rate in the VdECM group was higher than that of control, oxytetracycline, and epidermal growth factor ointments.

Conclusion:

VdECM contains a high ratio of elastin to collagen and amplifies expressions of many growth factors. It promotes fibroblast migration, proliferation, and survival, and epithelialization comparable to other topical agents.

Keywords: Extracellular matrix, Decellularized extracellular matrix, Elastin, Wound healing

Introduction

Extracellular matrix (ECM) is a non-cellular structure made of macromolecules that support cell homeostasis and regulate various cellular activities, including cell adhesion, migration, proliferation, differentiation, and survival [1–4]. Its regenerative potential is being actively studied in various fields [5, 6]. Most of its components are fibrous-forming molecules, such as collagen, elastin, fibronectin, and glycosaminoglycans which form large fibrilar structures that interconnect and associate with each other to form a three-dimensional network [7]. They are also closely linked to various stages of wound healing and provide structure and integrity [8, 9]. Elastin, in particular, plays an important role in scarless wound healing [10]. It is a cross-linked form of tropoelastin fibers that provides elasticity in lung, blood vessels, and skin [11, 12] and builds scaffolds that reduce wound contraction by fibroblast differentiation, dermal regeneration, and improved skin elasticity [11, 13, 14]. It is studied closely to evaluate fetal wound healing, in which it promotes scaffolds for hyaluronic acid deposition to leave minimal scarring [9, 10].

Decellularized ECM (dECM) is a processed form of ECM that provides the native microenvironment for cell proliferation and differentiation [15]. Many studies in tissue engineering have shown that dECM provides not only the dermal components but also act as three-dimensional scaffolds for wound healing [15–17]. Since ECM composition varies for each organ, dECM from elastin-rich tissue was predicted to be most efficient in wound healing. Elastin is particularly abundant in blood vessels, where it is reported to take up to 32–50% of large arteries [11, 18]. Therefore, blood vessel-derived dECM (VdECM) was predicted to be a rich source of elastin molecules as well as other fiber-forming molecules that may facilitate wound healing.

In this study, we prepared a hydrogel of VdECM and compared its effectiveness in full-thickness wound healing with other dressing materials.

Materials and methods

Preparation of VdECM from porcine blood vessels

The VdECM was prepared from porcine aorta tissue from 6 months-old pigs. Connective and other soft tissues were removed from the blood vessel then the normal blood vessel was cut to 2.5 × 2.5 cm2-sized pieces. Pieces were washed with distilled water and underwent a primary virus inactivation process using n-propanol. Next, it went through a decellularization process using n-propanol and NaOH solutions and was neutralized using DNase enzyme. Next, fat removal process was performed through H2O2 and acetone solution, followed by the second virus inactivation process using peracetic acid solution. The decellularized blood vessels were freeze-dried and ground to powder form. Grossly, it shows a white, odorless, consistent powder. (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

VdECM from porcine blood vessel tissue (VdECM = blood vessel-derived decellularized extracellular matrix)

Weight composition of elastin in VdECM

Amount of elastin in VdECM was analyzed using the Fastin Elastin Assay Kit (Biocolor, F4000) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. 5-mg samples were digested in 750 μl of 0.25 M oxalic acid at 100 °C for 1 h. Digested samples were then cooled at room temperature, centrifuged for ten minutes at 10,000 rpm, and collected for the 50 to 250 μl of supernatant. This process was repeated three times using same sample. A total of three extractions were performed and the extractions were combined for each sample. The absorbance values were measured at 513 nm and compared to those of the standard curve to determine the concentration of elastin in the samples.

Fibroblast cell scratch assay in VdECM and atelocollagen

Fibroblast cells were used for in vitro cell test. Cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 1% penicillin and streptomycin (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Media change was performed every two days. Culture condition was maintained in 37 °C and 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere. Migratory potential of fibroblasts in VdECM was compared to that of fibroblasts in 3% atelocollagen (MScollagen, MSbio, Sungnam, South Korea) by an in vitro scratch assay. A scratch wound assay was performed to confirm the effect of atelocollagen and VdECM on migratory potential of cells. The fibroblast cells were seeded at a density of 2 × 105 cell/well into 6-well cell culture plate containing α-MEM (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific) culture medium supplemented with 2% FBS and incubated overnight at 37 °C, in 5% CO2 atmosphere to permit cell adhesion. After incubation, media was completely removed, and the adherent cell layer was scratched with a sterile 1000 µl pipette tip. The removed medium was replaced with 20 ml of α-MEM with 2% FBS for the control group, and 4 g of either atelocollagen or VdECM powder was added for each group. The cells were incubated at 37 °C in humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere, and scratch area was measured at 0, 12, and 24 h using ImageJ imaging Software. Cell migration was analyzed according to the following formula.

Preparation of VdECM hydrogel

For the production of hydrogel, atelocollagen was dissolved in 10−3 N HCl solution according to the manufacturer's protocol. The dissolved collagen solution was mixed with 10 × MEM (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and a reconstituted buffer at a volume ratio of 8:1:1 to produce collagen hydrogel. The reconstituted buffer consisted of 2.2 g of NaHCO3, 4.77 g of 200 mM HEPES, 0.05 N NaOH and filled with distilled water to 100 ml. This produces a 3% atelocollagen hydrogel, to which VdECM in powder form was added to wanted percent composition.. Finally, the mixed hydrogel was gelled at 37 °C for 30 min under 5% CO2 conditions. Gross form of VdECM hydrogel is shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

(A) Gross morphology of 0.35% VdECM hydrogel, (B) Microscopic examination of VdECM hydrogel shows evenly distributed with maximum diameter in the range of 50 μm. (VdECM = blood vessel-derived decellularized extracellular matrix)

Microscopic examination of VdECM hydrogel

To see the dispersion of 0.35% VdECM hydrogel (Surgicure, T&R Biofab, Pangyo, South Korea) contained hydrogel took place on the slide glass. 20 μl of each agent was evenly spread and covered with cover glass. Microscopic images ( 40, 100, 200) were taken using an Olympus fluorescent microscope (BX53F, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The purpose of this examination was to see whether the particulates were evenly distributed without clumping.

Fibroblast proliferation test in atelocollagen and VdECM hydrogel

To quantify fibroblast proliferation in hydrogel, we used the Cell Count Kit-8 (CCK-8, Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) on days 0, 1, 4, 7 and 14 after mixing. 3% atelocollagen was mixed with 0.35% or 1% VdECM hydrogel for comparison. CCK-8 solution was diluted 1:10 with culture medium and added to samples, which were then incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. The optical densities of culture supernatants were then measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Victor NIVO™ multimode plate reader, PerkinElmer, Daejeon, South Kroea). Using the OD values, the number of cells was calculated based on a standard curve generated using fibroblast.

Live/dead staining of fibroblast in atelocollagen and VdECM hydrogel

Live/dead staining was done to examine the viability of human fibroblasts in 0.35%, and 0.1% VdECM hydrogel and 3% atelocollagen. After production of hydrogels in respective composition, samples were stained using live/dead staining solution (Live/dead assay kit, Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing 2 μM calcein AM and 4 μM EthD-1 on days 0, 1, 4, 7 and 14. After washing three times with PBS solutions to remove excess cells, pictures were taken using an Olympus fluorescent microscope (BX53F, Olympus). Live and dead cells were counted, and cell viability was calculated via the following equation.

Cytokine expression of adipocyte-derived stem cell (ASC) mixed with VdECM

In order to find out how various growth factors are expressed, we also compared the expressions of various cytokines in adipocyte-derived stem cell (ASC) media with those in VdECM mixed ASC media. ASCs were seeded in 60-mm culture dishes at a density of 6000/cm2. The medium was exchanged the following day for fresh DMEM containing 1% antibiotic–antimycotic. After incubation for 72 h, the supernatant was collected and subjected to analysis using a RayBio Human Growth Factor Array C1 (RayBiotech, Norcross, GA, USA) that had been pretreated according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The membrane of the cytokine array was analyzed using an LAS 4000 (Fujifilm, Tokyo, Japan), and the relative ratios were quantified using Multi Gauge software (Fujifilm).

Wound healing effect of 0.35% VdECM hydrogel in rat models

All animal experiments were performed after receiving approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Catholic University of Korea, College of Medicine (IACUC approval No. CUMC-2021–0267-03). We used rat models to evaluate the effect of VdECM on wound healing. Twenty Sprague Dawley rats were divided into four subgroups: no topical agents, oxytetracycline ointment, EGF ointment, and 0.35% VdECM. Each rat was anesthetized by isoflurane gas inhalation before surgical procedure. Dorsal intrascapular areas were shaved and sterilized with 70% ethanol. A 2 cm-diameter full-thickness wound was made with No. 15 surgical blade at about 1 cm caudal to the mid-scapular point. Contracture prevention ring was placed concentrically to the wound and was sutured with #4–0 Nylon suture. Initial wounds were photographed. Control group rats were directly dressed with Vaseline gauze and absorbent foam dressing (Medifoam, Mundipharma, South Korea), securely fasted with adhesive tapes (Hypafix gentle touch, BSN medical GmbH, Hamburg, Germany) and bandages (Surginet, Won industries, South Korea). Each group was applied with respective treatments using a cotton swab before being dressed in identical manner. Control group was not applied any topical agent. All dressings were placed to not interfere with the animal’s movements or respiration, and changed every two days at which photographic records were taken. At two weeks, dressings were removed under isoflurane anesthesia. Wounds were cleansed with saline solution and cotton swab. Contracture prevention rings were removed and wounds were photographed for gross assay. A cross-sectional sample of about 5 mm by 4 cm was designed across the diameter of the wound, and were harvested with No. 15 blade and surgical scissors. Using the ImageJ software analysis, wound size and epithelialization percentages were measured. Re-epithelialization rate was measured by comparing initial and final areas of the wounds. Cross-section specimens were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Hematoxylin and eosin staining was done to see the proportion of epithelialization of the wounds in H & E stained slides.

Results

Weight composition of elastin in VdECM

Weight composition of elastin was analyzed for VdECM and atelocollagen. VdECM contained 544.1 μg/mg (54.4%) elastin while atelocollagen contained 81 μg/mg elastin (8.1%). By unit weight, VdECM contains 6.7 times more elastin than atelocollagen. (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Elastin composition of VdECM and atelocollagen was analyzed. VdECM contained 544.1 μg/mg (54.4%) elastin while atelocollagen contained 81 μg/mg elastin (8.1%). By unit weight, VdECM contains 6.7 times more elastin than atelocollagen. (VdECM = blood vessel-derived decellularized extracellular matrix)

Fibroblast cell scratch assay in VdECM and atelocollagen

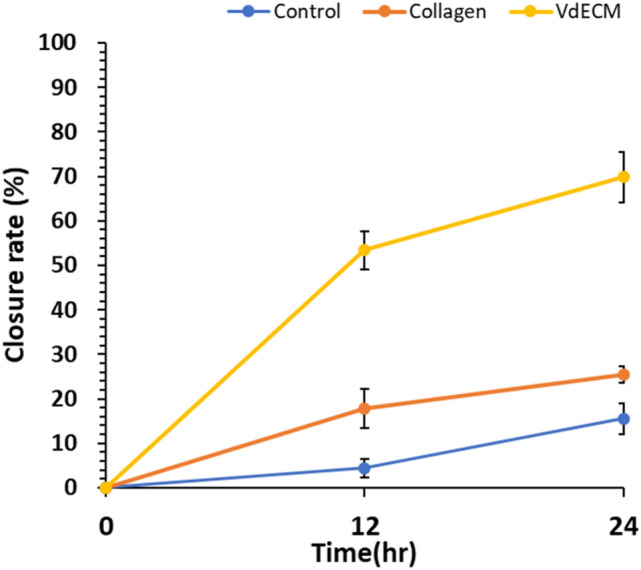

Scratch test shows the rate of cell migration to cover the cell-free area. Microscopic pictures were taken at 0, 12, 24 h to see cell migration. The pictures show a marked difference in migration rates from microscopic observation. (Fig. 3) By analysis with ImageJ, closure rates at 0, 12 and 24 h were 0, 4%, and 16% for control, 0, 18%, and 25% for atelocollagen and 0, 53%, and 70% for VdECM. (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Scratch test for control, 3% atelocollagen, and VdECM media. Migration of fibroblasts are seen at 0, 12, 24 h (VdECM = blood vessel-derived decellularized extracellular matrix)

Fig. 4.

Closure rates of scratch test in control, 3% atelocollagen, and VdECM media at 0, 12, 24 h. Control media showed 0%, 4%, and 16%, atelocollagen showed 0, 18%, 25% and VdECM showed 0, 53%, 70%, respectively. (VdECM = blood vessel-derived decellularized extracellular matrix)

Microscopic examination of VdECM hydrogel

Microscopic morphology of 0.35% VdECM hydrogel was taken with Olympus fluorescent microscope (BX53F, Olympus) at 40 × , 100 × 200 × magnifications. They are evenly distributed throughout the field, without forming a coherent structure or formation. (Fig. 5).

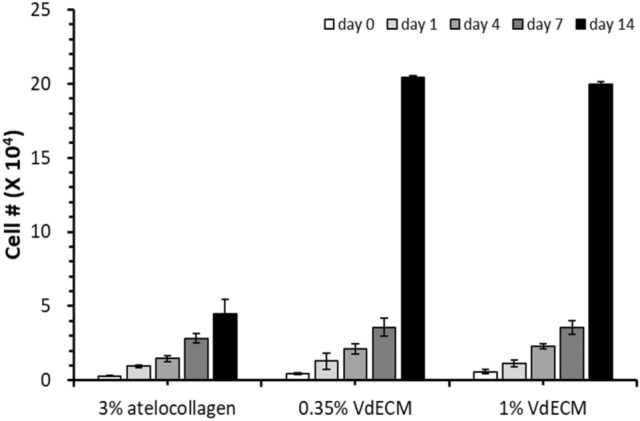

Fibroblast proliferation test in atelocollagen and VdECM hydrogel

Varying concentrations of VdECM and 3% atelocollagen were compared with 3% atelocollagen in fibroblast proliferation. Hydrogels of 3% atelocollagen, and its mixture with 0.35% or 1% VdECM media were incubated with fibroblasts. For the atelocollagen control group, the cell count was 0.30 × 104 cells, 0.96 × 104 cells, 1.46 × 104 cells, 2.30 × 104 cells, and 4.50 × 104 cells for Day 0, 1, 4, 7, 14. For 0.35% VdECM hydrogel, the cell count was 0.47 × 104 cells, 1.29 × 104 cells, 1.04 × 104 cells, 1.89 × 104 cells, and 20.40 × 104 cells respectively. For 1% VdECM hydrogel, the cell count was 0.58 × 104 cells, 1.15 × 104 cells, 1.21 × 104 cells, 6.24 × 104 cells, and 19.99 × 104 cells respectively. (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Cell proliferation of 3% atelocollagen hydrogels with different concentrations of VdECM. Cell count was markedly high for 0.35% and 1% VdECM at day 14 compared to 3% atelocollagen only group (VdECM = blood vessel-derived decellularized extracellular matrix)

Live/dead staining of fibroblast in atelocollagen and VdECM hydrogel

The live/dead assay was carried out to investigate the cell viability in the hydrogel. Fluorescence microscopic observations showed a much higher percentage of cells survived for 0, 0.35, and 1% VdECM media at day 0, 1, 4, 7, 14. (Fig. 7) Each day’s cell survival at day 0, 1, 4, 7, 14 were 99.7, 98.1, 94.6, 99.7, and 99.4% for control group respectively, 100% for all days for 0.35% VdECM, and 100, 99.3, 93.9, 99.9, and 100% for 1% VdECM, respectively.

Fig. 7.

Fibroblast cells were stained and photographed in atelocollagen, 0.35%, and 1% VdECM and taken pictures of using a fluorescent microscope. (VdECM = Vessel-derived decellularized extracellular matrix)

Cytokine expression of adipocyte-derived stem cell (ASC) mixed with VdECM

Cytokine array of growth factors in only ASC and VdECM mixed with ASC showed a different profile of growth factors between two groups. When VdECM was added in the ASC media during culture, expressions of all growth factors showed about from eight to 15- fold growth compared to those in ASC media alone, exception of IGFBP-4. (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Cytokine array of different growth factors in ASC media and VdECM added ASC media. All growth factor expressions are higher in VdECM added media. (VdECM = blood vessel-derived decellularized extracellular matrix, ASC = adipocyte derived stem cell)

Wound healing effect of 0.35% VdECM hydrogel in rat models

Wounds were dressed at days 0, 3, 5, 7, 11, and 13 at which photographic records were also taken. Wound healing occurred in all groups with time (Fig. 9). At day 13, wound healing rate was 69.9, 75.6, 69.6, and 95.5%, respectively for control, oxytetracycline, epidermal growth factor, and VdECM hydrogel groups (Fig. 10). Although VdECM hydrogel group showed the highest rate of wound healing, there was no statistical significance between the groups.Cross sections for each wound model were stained with H&E method. The wound size and epithelialization rate for VdECM hydrogel group was superior to those of control, oxytetracycline, and epidermal growth factor groups. (Fig. 11).

Fig. 9.

Progression of epithelialization for each wound model from day 0 to day 13

Fig. 10.

Wound healing rate for control, oxytetracycline, epidermal growth factor, and VdECM hydrogel groups at day 0, 7, and 13. (VdECM = blood vessel-derived decellularized extracellular matrix)

Fig. 11.

H & E stained cross sections of control, oxytetracycline, epidermal growth factor, and VdECM hydrogel wound models. (VdECM = blood vessel-derived decellularized extracellular matrix)

Discussion

ECM is a non-cellular component of scaffold structure that closely monitors the cell’s functions. It is a facilitating factor in regeneration of various tissues [Choi, 2012 #21][1], including wound healing [7, 19, 20]. It not only provides the three-dimensional scaffold structure, but also helps in fibroblast aggregation and angiogenesis induction [14, 17].

Elastin is a component of ECM that facilitates wound healing [9–11, 20]. It is deposited in the deep dermis, where it not only provides elasticity but also actively participates in antithrombosis, fibroblast aggregation, and fibroblast proliferation [21–23]. When skin injury occurs, efficient early wound response is important for tissue integrity restoration. In the inflammation process, elastin has chemotactic properties for dermal fibroblast aggregation and proliferation [24, 25], while promoting smooth muscle cell proliferation [26, 27].

There have been several attempts for fabrication of elastin substitutes. Often scarce in other tissues [9], elastin is abundantly found in lung and large vessels [11, 12]. Shiratsuchi et al. have shown that mammalian and piscine elastin peptides are effective substitutes for human elastin peptides in fibroblast aggregation and proliferation. Also, incorporation of scaffolds helps with elastin deposition [11, 21] sinceelastin peptides thicken the epidermis in systematic cross-linking layers to heal wounds [28, 29]. Therefore, we used porcine blood vessel tissue to provide elastin-rich dECM hydrogel form to facilitate wound healing and examine its properties.

We analyzed the relative elastin composition in comparison to atelocollagen. Type I collagen is another important part of skin tissue with major roles in wound healing and scar formation. Atelocollagen is a form of collagen with the immunogenic N- and C-termal telopeptides eliminated [30, 31]. Adding elastin fibers to the scaffold is reported to not only aid skin regeneration but also prevent contracture [14, 17, 18], showing better epithelialization when there is a higher ratio of elastin. Comparing VdECM’s composition to atelocollagen, VdECM contains about 6.7 times more elastin per unit mass of atelocollagen. As per previous studies, higher composition of elastin with biological scaffold of dECM may improve epithelialization rates and wound healing.

Proliferation stage in wound healing requires fibroblast aggregation. It is important for the fibroblasts to migrate and survive in the wounds to engage in activities. Inflammatory cells, such as neutrophil, lymphocyte, macrophage exude enzyme and cytokine, and those particularly emitted by microphage induces fibroblast migration to synthesize collagen fibers [10]. In our proliferation test, we could see that the fibroblast cell count increased with respect to VdECM concentration. In all experiment groups, fibroblast count increased until day seven but at day 14, all VdECM groups had drastically accelerated to 20 104 cells regardless of concentration. Considering that the proliferation stage occurs between six and 21 days of wound healing process [10], fibroblast proliferation at day 14 can be clinically significant in ECM synthesis and granulation tissue formation. L/D stain experiment shows fibroblast cell survival in the media. Cell viability was highest in 0.35% VdECM but did not differ significantly between groups. Especially in the 3% atelocollagen group the survival rate was 95%, which showed that the addition of VdECM was not detrimental to fibroblast survival.

This study also used animal wound models to see the effect of VdECM hydrogel on wound healing and epithelialization rates when applied transdermally. 0.35% VdECM hydrogel was compared to other commonly used topical agents, such as oxytetracycline and epidermal growth factor ointments. At day 13, VdECM group showed the highest wound healing rate of 96.6%. Although results were not statistically significant, it showed that 0.35% VdECM hydrogel is beneficial to wound healing.

Cross-sections of animal wounds were stained for histological analysis. H & E stain showed that the epithelialization was fastest in the VdECM wounds. Epithelialization is an important stage in successful wound healing, and a determinant in complete remission [32]. Epithelial cell growth from wound margin takes place by a complex interaction of keratinocyte, fibroblast, endothelial, and immune cells, which accelerate epithelialization and angiogenesis by producing various cytokines [33]. Cytokine array analysis was in this study was to include various factors that are related to cell life cycle including angiogenesis, proliferation, and apoptosis. Expressions for growth factors have increased drastically, from eight to 15- fold, when VdECM was introduced to the ASC media. This shows that the amplification effect of VdECM on the growth factors expressed by ASC may assist in wound healing and epithelialization.

There are several limitations to this study. In vitro composition analysis does not take into account the components other than collagen or elastin that may have positive influences on VdECM’s influence on wound healing. Also, the in vivo experiments do not isolate the sole effect of elastin composition on wound healing. It is also not able to corroborate elastin’s effect of scarless wound healing, since it does not consider the scars after wounds have healed. Cytokine array of amplified expressions does not explain specific modes of action for each cytokine. While VdECM added ASC media does show enhanced expressions, it is premature to conclude that they are beneficial to wound healing. Further analysis on these subjects may better explore the mechanisms of wound healing.

Acknowledgement

This work was financially supported by the Ministry of Trade Industry and Energy of Korea (20000325).

Author contributions

Data collection: YHR, SJL, BYK. Analysis and Interpretation of results: CRL, YHR, SJL, BYK, SHM, JWR. Draft Manuscript preparation: CRL, SJL, SHM.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Statement

The animal studies were performed after receiving approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) in Catholic University of Korea, College of Medicine (IACUC approval No. CUMC-2021-0267-03)

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wu XJ, Wang YJ, Wu Q, Li Y, Li L, Tang J, et al. Genipin-crosslinked, immunogen-reduced decellularized porcine liver scaffold for bioengineered hepatic tissue. Tissue Eng Regener Med. 2015;12:417–26. doi: 10.1007/s13770-015-0006-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hielscher AC, Gerecht S. Engineering approaches for investigating tumor angiogenesis: exploiting the role of the extracellular matrix. Cancer Res. 2012;72:6089–96. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Järveläinen H, Sainio A, Koulu M, Wight TN, Penttinen R. Extracellular matrix molecules: potential targets in pharmacotherapy. Pharmacol Rev. 2009;61:198–223. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.001289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daley WP, Peters SB, Larsen M. Extracellular matrix dynamics in development and regenerative medicine. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:255–64. doi: 10.1242/jcs.006064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi SH, Chun SY, Chae SY, Kim JR, Oh SH, Chung SK, et al. Development of a porcine renal extracellular matrix scaffold as a platform for kidney regeneration. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2015;103:1391–403. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hashim SNM, Yusof MFH, Zahari W, Noordin K, Kannan TP, Hamid SSA, et al. Angiogenic potential of extracellular matrix of human amniotic membrane. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2016;13:211–7. doi: 10.1007/s13770-016-9057-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frantz C, Stewart KM, Weaver VM. The extracellular matrix at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:4195–200. doi: 10.1242/jcs.023820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Theocharis AD, Skandalis SS, Tzanakakis GN, Karamanos NK. Proteoglycans in health and disease: novel roles for proteoglycans in malignancy and their pharmacological targeting. Febs J. 2010;277:3904–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Almine JF, Wise SG, Weiss AS. Elastin signaling in wound repair. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2012;96:248–57. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.21016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Broughton G, 2nd, Janis JE, Attinger CE. Wound healing: an overview. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(7 Suppl):1–32. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000222562.60260.f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daamen WF, Veerkamp JH, van Hest JC, van Kuppevelt TH. Elastin as a biomaterial for tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2007;28:4378–98. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Antonicelli F, Bellon G, Debelle L, Hornebeck W. Elastin-elastases and inflamm-aging. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2007;79:99–155. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(06)79005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pasquali-Ronchetti I, Baccarani-Contri M. Elastic fiber during development and aging. Microsc Res Tech. 1997;38:428–35. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19970815)38:4<428::AID-JEMT10>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Vries HJ, Middelkoop E, van Heemstra-Hoen M, Wildevuur CH, Westerhof W. Stromal cells from subcutaneous adipose tissue seeded in a native collagen/elastin dermal substitute reduce wound contraction in full thickness skin defects. Lab Invest. 1995;73:532–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim YS, Majid M, Melchiorri AJ, Mikos AG. Applications of decellularized extracellular matrix in bone and cartilage tissue engineering. Bioeng Transl Med. 2019;4:83–95. doi: 10.1002/btm2.10110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hafemann B, Ensslen S, Erdmann C, Niedballa R, Zühlke A, Ghofrani K, et al. Use of a collagen/elastin-membrane for the tissue engineering of dermis. Burns. 1999;25:373–84. doi: 10.1016/S0305-4179(98)00162-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lamme EN, van Leeuwen RT, Jonker A, van Marle J, Middelkoop E. Living skin substitutes: survival and function of fibroblasts seeded in a dermal substitute in experimental wounds. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;111:989–995. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Almine JF, Bax DV, Mithieux SM, Nivison-Smith L, Rnjak J, Waterhouse A, et al. Elastin-based materials. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39:3371–9. doi: 10.1039/b919452p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dzobo K, Motaung K, Adesida A. Recent trends in decellularized extracellular matrix bioinks for 3D printing: an updated review. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:18. doi: 10.3390/ijms20184628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xia Z, Guo X, Yu N, Zeng A, Si L, Long F, et al. The application of decellularized adipose tissue promotes wound healing. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2020;17:863–74. doi: 10.1007/s13770-020-00286-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shiratsuchi E, Nakaba M, Yamada M. Elastin hydrolysate derived from fish enhances proliferation of human skin fibroblasts and elastin synthesis in human skin fibroblasts and improves the skin conditions. J Sci Food Agric. 2016;96:1672–7. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.7270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Castro Bras LE, Frangogiannis NG. Extracellular matrix-derived peptides in tissue remodeling and fibrosis. Matrix Biol. 2020;91–92:176–87. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2020.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Almine JF, Wise SG, Hiob M, Singh NK, Tiwari KK, Vali S, et al. Elastin sequences trigger transient proinflammatory responses by human dermal fibroblasts. FASEB J. 2013;27:3455–65. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-231787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Senior RM, Griffin GL, Mecham RP, Wrenn DS, Prasad KU, Urry DW. Val-Gly-Val-Ala-Pro-Gly, a repeating peptide in elastin, is chemotactic for fibroblasts and monocytes. J Cell Biol. 1984;99:870–4. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.3.870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bisaccia F, Morelli MA, De Biasi M, Traniello S, Spisani S, Tamburro AM. Migration of monocytes in the presence of elastolytic fragments of elastin and in synthetic derivates. Structure-activity relationships. Int J Pept Protein Res. 1994;44:332–41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Wachi H, Seyama Y, Yamashita S, Suganami H, Uemura Y, Okamoto K, et al. Stimulation of cell proliferation and autoregulation of elastin expression by elastin peptide VPGVG in cultured chick vascular smooth muscle cells. FEBS Lett. 1995;368:215–9. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00641-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rnjak-Kovacina J, Wise SG, Li Z, Maitz PK, Young CJ, Wang Y, et al. Electrospun synthetic human elastin:collagen composite scaffolds for dermal tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2012;8:3714–22. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Machula H, Ensley B, Kellar R. Electrospun tropoelastin for delivery of therapeutic adipose-derived stem cells to full-thickness dermal wounds. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2014;3:367–75. doi: 10.1089/wound.2013.0513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nivison-Smith L, Rnjak J, Weiss AS. Synthetic human elastin microfibers: stable cross-linked tropoelastin and cell interactive constructs for tissue engineering applications. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:354–59. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lynn AK, Yannas IV, Bonfield W. Antigenicity and immunogenicity of collagen. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2004;71:343–54. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ochiya T, Takahama Y, Nagahara S, Sumita Y, Hisada A, Itoh H, et al. New delivery system for plasmid DNA in vivo using atelocollagen as a carrier material: the minipellet. Nat Med. 1999;5:707–10. doi: 10.1038/9560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pastar I, Stojadinovic O, Yin NC, Ramirez H, Nusbaum AG, Sawaya A, et al. Epithelialization in wound healing: a comprehensive review. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2014;3:445–64. doi: 10.1089/wound.2013.0473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rousselle P, Montmasson M, Garnier C. Extracellular matrix contribution to skin wound re-epithelialization. Matrix Biol. 2019;75:12–26. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2018.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]