Abstract

After implantation of a biomaterial, both the host immune system and properties of the material determine the local immune response. Through triggering or modulating the local immune response, materials can be designed towards a desired direction of promoting tissue repair or regeneration. High-throughput sequencing technologies such as single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) emerging as a powerful tool for dissecting the immune micro-environment around biomaterials, have not been fully utilized in the field of soft tissue regeneration. In this review, we first discussed the procedures of foreign body reaction in brief. Then, we summarized the influences that physical and chemical modulation of biomaterials have on cell behaviors in the micro-environment. Finally, we discussed the application of scRNA-seq in probing the scaffold immune micro-environment and provided some reference to designing immunomodulatory biomaterials. The foreign body response consists of a series of biological reactions. Immunomodulatory materials regulate immune cell activation and polarization, mediate divergent local immune micro-environments and possess different tissue engineering functions. The manipulation of physical and chemical properties of scaffolds can modulate local immune responses, resulting in different outcomes of fibrosis or tissue regeneration. With the advancement of technology, emerging techniques such as scRNA-seq provide an unprecedented understanding of immune cell heterogeneity and plasticity in a scaffold-induced immune micro-environment at high resolution. The in-depth understanding of the interaction between scaffolds and the host immune system helps to provide clues for the design of biomaterials to optimize regeneration and promote a pro-regenerative local immune micro-environment.

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Biomaterials, Immunomodulation, Single-cell technologies

Introduction

The host immune responses following biomaterial implantation are collectively called the foreign body response (FBR) [1]. This sequential reaction includes protein adsorption on the scaffold surface, inflammatory cell recruitment and infiltration, foreign body giant cells (FBGCs) formation, activation of fibroblast, and ultimately fibrotic encapsulation [2]. Scaffolds implanted can be made of natural or synthetic materials, in the forms of films, nanofibers, hydrogels, et al. [3]. When implanted in vivo, synthetic materials showed high immunogenicity and led to severe fibrotic response. The extracellular matrix (ECM) scaffold treated by decellularization treatment has well solved the problems above and showed good biocompatibility in native tissue [4, 5]. Since recruitment of immune cells is dictated by the tissue location where the biomaterial is implanted, degree of trauma, and the physiochemical properties of the scaffold [6], efforts have been made to improve the surgical procedures and scaffold design [7–9]. Different biological uses of the material require different physical and chemical properties, in some occasions, scaffolds are expected to function with very low degeneration and minimal fibrotic encapsulation [10], whereas others are designed to keep pace with tissue growth [11]. Biomaterials are therefore envisioned to be capable of modulating the local immune micro-environment to induce a favorable condition for tissue regeneration [3, 12]. The strategies of scaffold design mainly focus on the adjustment of physical cues and surface chemistries of materials [13]. The physical cues for modulation mostly including fiber size, stiffness, wettability, surface topography, pore size, etc., affect the adsorption of proteins and the biological reaction of immune cells to influence the process of acute and chronic inflammatory reactions, resulting in different outcomes of tissue fibrosis or regeneration [14–17]. Chemical methods include material composition, surface chemical modification, combination of bioactive substances. By reducing the first step of protein adsorption, then alleviating successive inflammatory responses, or releasing bioactive molecules with immunomodulatory function, the local immune micro-environment can be mediated into the direction of promoting tissue regeneration [14].

Immune cells such as granulocytes (neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils), mast cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, and lymphocytes (B cells, T cells) play different roles in mediating the foreign body response [18]. Neutrophil infiltration is predominant for the initial two days following implant placement. Then at day 3, the primary immune cell type becomes tissue-resident macrophages or monocyte-derived macrophages [19, 20]. Cells of the monocyte-macrophage lineage are highly heterogenous and plastic [21]. Macrophages might transition into pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages [induced by toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands and interferon-γ, (IFN-γ)] or anti-inflammatory M2 activation [induced by interleukin-4/interleukin-13, (IL-4/IL-13)] dictated by diverse environmental cues. The polarization of macrophages mirrors the T helper 1 (Th1)-Th2 transition of T cells [22, 23]. Recently, numerous studies have focused on the regulation of M2 macrophages on tissue regeneration and further explored the specific phenotype controlling regeneration and how these phenotypes switch within this heterogeneous and versatile lineage [24, 25]. Other cells besides macrophages also determine whether the tissue is headed for fibrosis or regeneration. The phenotypes, activation states and differentiation trajectories of immune cells in different anatomical niches have not been fully understood. In the past decade, emerging technologies like scRNA-seq and mass cytometry allow more accurate and high-resolution detection of the biosystem [26, 27]. Our understanding of the heterogeneity of immune cells populations, functions, and the diversity of their phenotypes continues to deepen [28, 29].

In this review, we briefly discuss the processes of foreign body response (FBR) and different types of immune response after biomaterial implantation. Then, we summarize the physical and chemical strategies used in developing immunomodulatory biomaterials. Finally, we discuss the application of scRNA-seq in probing the scaffold immune micro-environment to better inform biomaterials-directed regenerative immunoengineering design.

FBR and immune micro-environment around biomaterials

Foreign body response

Implantation of biomaterials can cause a series of chain reactions including protein adsorption, acute and chronic inflammatory reactions, formation of foreign body giant cells and fibrosis, which are collectively called FBR [7]. After implantation of the scaffold, proteins from blood and other body fluids, including albumin, fibronectin, fibrinogen, and chemoattractants generated by activated complement system, adhere to the biomaterial surface by intrinsic contact activation of the coagulation cascade and the alternative pathway of activation of completement system, forming provisional matrix, which is determined by biomechanical properties of materials [30, 31]. Then inflammatory cells possessing adhesion receptors interact with the adsorbed proteins on scaffold surface by pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMPS) and integrin-mediated interaction, leading to recognition of the biomaterials [1].

During the second stage of FBR, namely acute inflammation, granulocytes and mast cells infiltrate into the area. The damage associated molecular patterns (DAMP) like heat-shock proteins, and double-stranded DNA are released, and recruit granulocytes to the implantation sites [30, 32]. Neutrophils engulf and destroy cell debris by antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) [33]. These inflammatory cells then produce cytokines like IL-8, MCP-1, IL-4, IL-13, MIP1b, histamine and CXCL13. The released cytokines and chemokines recruit more leukocytes, especially macrophages, to the wound defect area to establish the chronic inflammation phase [34, 35]. Driven by DAMPs and natural killer cell-derived interferon-γ, macrophages polarize towards pro-inflammatory phenotype (M1) [36]. M1 macrophages synthesize matrix metalloprotease (MMPs) that can digest ECM and aid in their migration [32, 37, 38].

With the resolution of acute inflammation, the M1 macrophages polarize towards the alternatively activated M2 macrophage [13, 36]. M2 macrophages are further divided into M2a, M2b, M2c, and other subtypes, among which M2a and M2c subtypes promote angiogenesis and tissue repair [39–41]. During wound healing, colony stimulating factor-1(CSF-1)–dependent macrophages promote neoangiogenesis by secreting MMPs to accelerate matrix remodeling [42].

Macrophages fuse into FBGCs, which is considered a hallmark of FBR [34], perhaps to improve their functions or to avoid apoptosis [43]. This phenomenon appears to be harmful to biocompatibility of the scaffolds, and is regarded as a target for intervention [44]. As the chronic inflammation and FBGC formation proceed, a collagenous envelope surrounding the scaffold builds up. Triggered by pro-fibrotic signals, like TGF-β, fibroblasts and endothelial cells deposit collagen and other extracellular proteins on the surface of scaffolds [30, 34, 45]. This layer of granulation tissue may grow into a thick fibrotic tissue with extremely few infiltrated immune cells and poor vascularization, which might eventually lead to local infections [46]. The immune cells, inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and receptors involved in FBR are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Cells, proteins, cytokines and chemokines involved in FBR

| No. | Phase of FBR | Cell type | Cytokine | Chemokine | Protein | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Protein adsorption | Albumin, fibrinogen, kninogen, fibronectin, vitronectin, C3a, C5a | [1, 30, 31] | |||

| 2 | Acute inflammation | Granulocytes, mast cells, neutrophils, macrophages, endothelial cells, natural killer cells | IL-1,IL-4, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-13, MCP-1, MIP1b, histamine, interferon-γ,TNFα | Coagulation factor VII, XI, von Willebrand factor (vWF), PF4 or P-selectin,CXCL13 | DAMPs, MMPs, integrin receptors, Toll-like receptor (TLR) | [30, 32–38] |

| 3 | Chronic inflammation | Macrophage/monocytes, lymphocytes, mast cells | CSF-1, TGF-β, PDGF, MIP-1a, MIP-1b, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, IL-13, IL-4, IL-10 |

Complement factors, PF4, MCP-1,2,3,4, RANTES |

Mmps, TLR, scavenger receptors, integrin receptors | [13, 36, 39–42] |

| 4 | Formation of foreign body gigantic cells | Foreign body giant cells (FBGC), T cells, mast cells | IL-13, IL-4, IL-1a; IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, IL-10, TGF-β | MCP-1 | β-integrin receptors, mannose receptors, CD44, CD47, E-cadherin, CD11, CD45 | [34, 43, 44] |

| 5 | Fibrosis | FBGC, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, myofibroblasts | TGF-β, PDGF, VEGF | MMPs | [30, 34, 45, 46] |

Immune micro-environment around biomaterials

Scaffold implanted, local tissue environment and immune cells together constitute the local immune micro-environment [47]. Immune cells (neutrophils, macrophages, monocytes, NK cells, lymphocytes, mast cells, etc.) are the first fighters confronted with foreign bodies, and then send signals to activate fibroblasts in the tissue environment. The intercellular and intracellular signaling networks between immune cells and stromal cells lead to different physiological outcomes by directing cell behaviors and secreting cytokines, chemokines, or active substances [47].

In the regeneration process regulated by immunomodulatory biomaterials, cells of the innate and adaptive immune system play different, yet interactive roles. The type 1 immune polarization, driven by Th1(T-helper cell 1) cells from the adaptive immune system, is considered pro-inflammatory. M1 macrophages express nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and tumour necrosis factor (TNF) in response to the stimulation of IFN-γ produced by Th1 cells, TLRs, and other intracellular pattern recognition receptors. In reverse, cytokines and chemokines secreted by M1 macrophages, e.g., IL-12, CXCL9, and CXCL10, can recruit Th1 cells and promote the Type 1 polarization [48]. On the contrary, Type 2 immune polarization is characterized by the production of type 2 cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, IL-13, and is related to tissue repair and regeneration after wounding. Main cell types associated with type 2 immunity include Th2(T-helper cell 2) cells, macrophages activated by type 2 cytokines, mast cells and type 2 innate lymphoid cells [6, 49, 50]. Type 17 immune response has also been reported to promote chronic fibrosis in tissue around breast implants. Implantation of synthetic materials increased the expression level of IL-17 secreted by group 3 innate lymphoid cells, γδ T cells, and CD4+ adaptive T cells (Th17). It has been shown that elevated IL-17 expression was associated with fibrosis, while the blocking of IL-17 signaling reduced fibrotic response [51].

Synthetic and biological materials usually induce diverging immune micro-environments. When used in muscle wound, uncrosslinked ECM scaffolds induced increased levels of Th2-associated genes and genes related to DAMP signaling (Mbl2, Clec7a), which might contribute to the formation of pro-regenerative immune environment [52]. On the contrary, synthetic materials were usually associated with extensive and chronic neutrophil infiltration and various extents of fibrosis, depending on the material’s stiffness and size [52]. The exploration of immune cell activities around specific biomaterials implanted will provide new clues for the design of immunomodulatory materials.

Advances in the design and fabrication of immunomodulatory biomaterials

Upon implantation of biomaterials, host immune response might lead to impaired device function [53, 54]. To engineer immunomodulatory biomaterials, researchers usually focus on the incorporation and controlled release of immunomodulatory agents, regulation of target cell population, minimizing systemic toxicity, and modulation of scaffold physicochemical properties [55–59]. Here, we summarize the features of some of the immunomodulatory biomaterials used in soft tissue environment (skin/muscle). (Table 2).

Table 2.

Physical and chemical modifications and the modulatory effects of biomaterials

| No. | Author | Modification methods | Target immune cell | Modulatory effects | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical modification | |||||

| 1 | McWhorter et al. | Micropattern | Macrophages | Elongation of macrophages stimulated polarization toward an M2 phenotype | [60] |

| 2 | Luu et al. | Micro and nano-pattern | Macrophages | Microscale grooves activated M2 phenotype | [57] |

| 3 | Friedemann et al. | Matrix stiffness | Macrophages | Increase in matrix stiffness led to an anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotype | [61] |

| 4 | Abebayehu et al. | Fiber size and pore diameter | Mast cells | Pore size ≥ 4 μm diminished inflammatory cytokine production | [62] |

| 5 | Veiseh et al. | Dimensions of spheres | Macrophages | Spheres of ≥ φ1.5 mm mitigated foreign reactions and fibrosis | [56] |

| Modulation of surface chemistries | |||||

| 6 | Swartzlander et al. | Oligopeptide RGD | Macrophages | RGD reduced the fibrous capsule density and thickness | [63] |

| 7 | Alapure et al. | Mesenchymal stem cells loaded | Macrophages | Increase in M2 macrophages, and reduction of M1 macrophages | [64] |

| 8 | Zhang et al. | Prostaglandin E2 | Macrophages | Promoting the M2 phenotypic transformation of macrophages | [55] |

| 9 | Sok MCP et al. | AT-RvD1 and IL-10 | Mononuclear phagocytes | Recruiting CD206+ macrophages (M2a/c) and IL-10 expressing dendritic cells | [65] |

| 10 | Yan et al. | Sialidase | THP-1, macrophages | Transiently activating macrophages in a sialic acid-dependent manner | [66] |

| 11 | Dong et al. | IFN-γ, mesenchymal stem cells loaded | Macrophages | Promoting polarization of M2 macrophages, reducing FBR, and avoiding tendon adhesion | [67] |

| 12 | He et al. | Modifying L-nitroarginine and PEA copolymers | Macrophages | Reducing NO, and increasing the arginase activity in macrophages | [68] |

| 13 | Jiang et al. | Mannose-decorated globular lysine dendrimers (MGLDs) | Macrophages | Targeting M2 polarization, inhibiting the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and increasing the production of TGF-β1 | [69] |

| 14 | Welch et al. | B7-33 | Fibroblasts | Reducing the fibrous encapsulation | [70] |

| 15 | Chu et al | EGCG | Macrophages | Promoting M2 polarization | [71–78] |

Modulation of physical cues

Microscale and nanoscale structural properties of biomaterials can regulate cellular responses and alter cell fates [79]. In the internal environment, physical cues of the scaffolds, including fiber size, stiffness, wettability, surface topography and porosity of the biomaterial, can modulate FBR by tuning phenotypes of immune cells [56, 58, 80]. Nanofiber structure is more similar to extracellular interstitial structure according to its porous structure and high specific surface area, which facilitates cell adhesion, nutrient exchange and waste transport, and can guide specific immune cell phenotypic differentiation and promote tissue maturation [79, 81, 82]. Dhivya et al. summarized matrix characteristics that promote anti-inflammatory immunophenotypes by concluding the regulation of specific fiber diameter, aperture, and fiber orientation on the fate of innate immune cells [83]. In response to diverse surface topography of ECM structures, bone marrow-derived macrophages showed different cell shape. According to Liu et al., cell elongation enhanced the expression of M2-related arginase-1 and mitigated the expression of M1-related iNOS [60]. The same group also found that cultured on groove sizes ranging from 400 nm–5 μm in width are along with higher levels of anti-inflammatory IL-10 secrection of macrophages [57]. As for engineered 3D Coll based matrices, variation of matrix stiffness by EDC crosslinking and covalent glycosaminoglycan (GAG) modification affected the polarization states of macrophages [61]. An increase in matrix stiffness resulted in an anti-inflammatory macrophage phenotype [61]. Mast cells were also necessary in FBR [84]. When they were seeded on electrospun polydioxanone (PDO) scaffolds with diverse fiber size and pore diameter and stimulated with IL-33 or lipopolysaccharide (LPS), inflammatory cytokine production was greatly reduced on scaffolds with larger pore size (at or more than 4 μm) [62]. To explore the role of spherical biomaterial geometry on FBR, Zandstra et al. injected monodisperse microspheres of defined size and polydisperse microspheres under rat skin. Macrophage infiltration and collagen encapsulation increased in small microspheres compared to large ones [85]. It was further demonstrated that the spherical shape and spheres with diameter of 1.5 mm or greater significantly alleviated foreign reactions and fibrosis [56].

Modulation of surface chemistries

Molecules, drugs, and ions are often applied to biomaterials to regulate FBR [70]. Among the candidate materials, hydrogels with the properties of high permeability, low immunogenicity and adjustable mechanical properties can mimic physicochemical structure of natural ECM to restore and rebuild tissue function and were used to treat soft tissue wounds in a number of studies [86, 87]. To reduce protein adsorption at the first step of FBR, some authors incorporated arginine-glycine-aspartic acid (RGD) into poly (ethylene) glycol (PEG) hydrogels, which reduced the density and thickness of fibrotic capsules [63]. Alapure et al. synthesized a biodegradable hybrid hydrogel (ACgels) and evaluated its effects in burn wounds. Significantly higher re-epithelialization and angiogenesis was observed for the ACgels seeded with mesenchymal stem cells [64]. Zhang et al. incorporated PGE2 into chitosan (CS) hydrogel. The composite hydrogel enhanced the secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines in macrophages and promoted angiogenesis in vitro, characterized by increased expression of M2-associated genes [55]. Sok et al. combined aspirin-triggered resolvin-D1 (AT-RvD1) and IL-10 in the hydrogel synthesis process. AT-RvD1 can mediate the reorientation of immune cell, limit neutrophil migration, and regulate macrophage maturation. The combined application of AT-RvD1 and IL-10 enhanced the expression of macrophages and dendritic cells in the tissue defect area, and promoted wound healing by facilitating the recruitment of anti-inflammatory macrophages [65]. In addition, mucins can also be added into hydrogels as regulatory molecules, transiently activating macrophages possibly by influencing sialic acid receptors such as siglecs [66].

In addition to hydrogels, tissue-derived ECM and other synthetic materials can be chemically modified to regulate surrounding immune micro-environment as well. Dong et al. modified polycaprolactone/silk fibroin (PCL/SF) composite fibrous scaffold with ECM derived from MSC, and stimulated ECM with IFN-γ to obtain immunomodulatory ECM (iECM). They found that iECM-modified scaffold promoted polarization of M2 macrophages to reduce FBR and tendon adhesion [67]. L-nitroarginine (NOArg) based polyester amide (NOArg-PEA) and NOArg-Arg PEA copolymers can be chemically modified to tune levels of NO, cytokine, and growth factors produced from macrophages. The application of NOArg-Arg co-PEA to diabetic rat skin wound promoted wound healing and re-epithelialization, lowered inflammatory cell infiltration, and induced higher M2/M1 ratio [68]. Jiang et al. implanted mannose-decorated globular lysine dendrimers (MGLDs) into full-thickness skin defect of type 2 diabetic mice. This design also effectively promoted the wound healing by targeting M2 polarization, inhibiting pro-inflammatory cytokines secretion and promoting the production of TGF-β1 [69]. B7-33, a truncated B-chain analogue of relaxin (antifibrotic), was incorporated into poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid (PLGA) coatings. The sustaining release of B7-33 reduced the fibrous encapsulation surrounding a subcutaneous implant [70, 88]. Collagen membranes cross-linked by Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) were able to improve cell proliferation and differentiation [71–74], and promoted bone regeneration when combined with nanohydroxyapatite coatings [75]. According to more recent findings, EGCG-modified collagen membranes successfully ameliorated FBR by enhancing M2 polarization of macrophages [76, 77], which might be associated with C–C chemokine receptor type 2 (CCR2) signaling [78].

Current available skin and gingival grafts and future perspectives

The currently available soft tissue grafts in clinic are summarized in Table 3 [89–95]. The skin and gingival substitutes are either biological (autologous, allogeneic, xenogeneic) or synthetic, some of them contain autologous or allogeneic cells. For volumetric muscle loss (VML) injuries, however, clinical treatments besides autografting are lacking. Engineered muscle graft by means of electrospinning, bioprinting, dielectrophoresis, and microfluidic techniques were reported [79, 96, 97]. So far, no commercially available tissue engineered skin grafts possess all properties of an ‘ideal’ skin substitute [92]. The above-mentioned immune-modulatory biomaterials (listed in Table 3) might provide references for the design of future soft tissue grafts.

Table 3.

| Manufacturer | Description | Indications |

|---|---|---|

| Skin: commercially available or marketed dermo-epidermal skin grafts | ||

| Allograft | ||

| Allograft | Native human skin with cells | Temporary dressing for large burns |

| Karoskin | Native human cadaver skin | |

| Cellular-autologous | ||

| Epicel | Autologous keratinocytes transplanted using petrolatum gauze support | Burns and congenital nevus |

| EpiDex | Cultured hair follicle keratinocytes (confluent cell sheet) | Chronic leg ulcers |

| CellSpray | Autologous keratinocytes (subconfluent cell suspension) | Partial-thickness and donor site wounds |

| MySkin | Cultured autologous keratinocytes seeded on silicone supported layer | Ulcers, superficial burns and skin graft donor sites |

| PolyActive | Autologous keratinocytes and fibroblasts cultured in PEO/PBT scaffold | Partial-thickness wounds and skin graft donor sites |

| TissueTech autograft system | Autologous keratinocytes and fibroblasts seeded in a hyaluronic acid scaffold | Diabetic foot ulcers, ischaemic and neuropathic wounds, post-surgical ulcers |

| Laserskin (Vivoderm) | Autologous keratinocytes seeded on a hyaluronic acid membrane | Excised wounds |

| Bioseed-S | Autologous keratinocytes (subconfluent cell suspension) on fibrin sealant | Chronic ulcers |

| Hyalograft | Autologous fibroblasts seeded on hyaluronic acid ester scaffold | Feet ulcer |

| Acellular | ||

| Integra | Dermal layer: bovine collagen-chondroitin-6-sulfate matrix; epidermal layer: synthetic silicone polymer | Deep partial- or full-thickness burns |

| Biobrane | Semipermeable silicone membrane bonded to nylon fabric | Temporary wound covering for partial-thickness excised burns and donor sites |

| AlloDerm | Human acellular lyophilized dermis | Dermal graft for burns and other wounds |

| Terudermis | Fibrillar atelocollagen and heat-denatured collagen | Dermal or mucosal defect |

| Pelnac | Silicone fortified with silicone gauze TREX, atelocollagen derived from pig tendon | Temporary dermal substitute matrix for all skin loss wounds |

| SureDerm | Human acellular lyophilized dermis | Hypertrophic scar revision and burns |

| GraftJacket | Human acellular pre-meshed dermis | Tendon and low extremity wounds repair |

| Matriderm | Bovine non-cross-linked lyophilized dermis, coated with a-elastin hydrolysate | Deep dermal defects and a split-thickness skin graft |

| Permacol | Porcine acellular crosslinked dermis | Complex and recurrent hernia repair |

| OASIS wound matrix | Porcine acellular lyophilized small intestine submucosa | Partial and full-thickness wounds, tunneled wounds, and ulcers |

| EZ Derm | Porcine aldehyde cross-linked reconstituted dermal collagen | Partial-thickness burns |

| Hyalomatrix PA | Hyaluronic acid derivatives layered on silicone membrane | Deep partial-thickness burns, wounds after dermabrasion, and deep paediatric burns |

| Cellular-allogeneic | ||

| TransCyte | Neonatal fibroblasts seeded on silicon film, nylon mesh, porcine dermal collagen | Temporary covering for excised deep partial- and full-thickness burns before autografting |

| Dermagraft | Neonatal fibroblasts seeded on polyglactin mesh scaffold | Full-thickness chronic diabetic foot ulcers |

| Apligraf | Allogeneic neonatal keratinocytes and fibroblasts cultured in bovine collagen gel | Chronic foot ulcers and venous leg ulcers; burn wounds and epidermolysis bullosa (EB) |

| OrCel | Allogeneic keratinocytes and fibroblasts cultured in bovine collagen sponge | Split-thickness donor sites |

| Gingiva: marketed gingival substitute | ||

| Mucograft | Porcine collagen matrix without cross-linking | Recession coverage and regeneration of keratinized mucosa around teeth and implants |

| Fibro-Gide | Porcine, porous, resorbable and volume-stable collagen matrix with smart chemically cross-linking | Thicken the soft tissue around teeth and implants and under pontics |

| Mucograft Seal | A ready-to-use matrix with a convenient circular shape | Cover extraction sockets during Ridge Preservation |

This list might not be all-inclusive

The continuous exploration on the modification of physical and chemical properties of materials has achieved gratifying results. Most of the researches focused on the characterization of material properties and the exploration of superficial biological and immunological reactions, while the in-depth study of the complex and dynamic immune micro-environment around materials is relatively lacking [47]. The deepening interpretation of the interaction mechanism between materials, local tissue and immune cells may provide possible cellular targets for the design of immunomodulatory materials.

Application of single-cell RNA-seq analysis in studying host response against biomaterials

Advances in biological techniques at the protein and gene levels have led to a deeper understanding of the cellular responses surrounding the biomaterials implanted. Traditional protein-level detecting biotechnologies like flow cytometry, western blot, and immunohistochemical/immunofluorescent staining are able to classify immune cells roughly according to few predefined surface markers, but there exists a certain bias. Conventional gene-level techniques such as quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) can measure population gene expression level based on pre-determined maker genes [98]. However, these markers might be expressed by multiple cell lineages, and plasticity of immune cells may lead to inaccurate classification [99]. In recent years, new analytical techniques have been developed, such as proteomics, mass cytometry, spectral flow cytometry, single-cell transcriptomics, and spatial transcriptomics. These techniques provide powerful tools for in-depth analysis of the immune micro-environment around materials [100, 101].

Bulk RNA-seq can help us understand the molecular mechanisms involved in specific biological process through the analysis of differential gene expression or the entire transcriptome in a mixture of tissues or cell populations [102, 103]. Nevertheless, this type of analysis did not reveal differences between individual cells, which was common in an internal environment regulated by numerous influencing factors [104]. The application of scRNA-seq has enabled thousands of gene expression to be studied at the level of individual cells simultaneously [105, 106], which is being widely applied to discover rare cell types, immunology, tumor heterogeneity, and human disease progress and treatment [107–109]. In recent years, scRNA-seq is increasingly being used to reveal meaningful cell-to-cell gene expression [108, 110, 111], disclose key processes in cell development [112–114], uncover signaling pathways involved in biological processes [115], and reflect intricate intercellular communications in the micro-environment [116].

By using scRNA-seq, previous studies have uncovered unknown heterogeneity of dendritic cells, CD127 + innate lymphoid cells, and pathogenic Th17 cells to name a few [117–120]. In recent years, studies on the biomaterial-induced immune micro-environment at high resolution are emerging (Table 4). Cherry et al. implanted biologic (ECM) and synthetic (PCL) biomaterial scaffolds into murine muscle defects. By analyzing the map of transcriptome, they characterized previously undefined cell subpopulations including NK cells and fibroblast subpopulations [47]. Huang et al. applied high fiber density and low fiber density silk scaffold to rat models. They found previously undefined macrophage subpopulations that are related to the loss of function of the biomaterials implanted: Mmp12+/Spp1+ (MD1), Mmp9+/mk67+ (MD2), Mt3+/Ckb+ (MD3), and further evaluated their functions under different fiber densities [121]. In another investigation, human split-thickness skin grafts (hSTSGs) were implanted into murine full-thickness excisional wounds. Using scRNA-seq, the authors identified a specific subpopulation of macrophages with high expression of the lipid receptor Trem2 (triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells), which showed a great potential to accelerate wound repair [122]. In the study by Sommerfeld et al., murine volumetric muscle injuries received treatment with ECM or synthetic biomaterial. CD45+CD64+F4/80hi+ macrophages were sorted for single-cell analysis. Nine clusters were computationally determined and could be distinguished by Cd301b, Cd9, and Cd74 [123]. Hu et al. dissected the immune micro-environment around electrospun scaffolds implanted into murine skin excisional wounds. Immune cells including macrophages and T cells showed great heterogeneity. They also found that the aligned scaffold fiber structure can accelerate the transition from innate immunity to adaptive immunity [124]. In addition to T cells and macrophages which are mostly explored, the function and heterogeneity of B cells around biomaterials are gradually being explored. To investigate the immune response of B cells to implanted biomaterials, Moore et al. implanted natural biomaterial (ECM) or synthetic biomaterial (PCL) into muscle wounds, and revealed the phenotype and differentiation of B cells using scRNA-seq. The results showed that ECM treatment accelerated germinal centers formation in spleen and lymph nodes. On the contrary, PCL group prolonged the appearance time of B cells and induces B cell antigen presentation and fibrosis [125]. In summary, all these findings mentioned above provide a deeper understanding of immune micro-environment around biomaterials, which may offer potential targets for future immunomodulatory biomaterial design [121].

Table 4.

Studies that analyze the immune micro-environments around scaffolds by using single-cell RNA-seq analysis

| No. | Authors | Scaffold implanted | Experimental model | Key findings | Referenecs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cherry et al. | ECM and PCL | Murine volumetric muscle injuries | Characterized previously undefined cell subpopulations including NK cells and fibroblast subpopulations | [47] |

| 2 | Huang et al. | High fiber density and low fiber density silk scaffold | Murine skin excisional wounds | Found previously undefined macrophage subpopulations related to the loss of function of the biomaterials implanted: Mmp12+/Spp1+ (MD1), Mmp9+/mk67+ (MD2), Mt3+/Ckb+ (MD3) | [121] |

| 3 | Henn et al. | Human split-thickness skin grafts | Murine full-thickness excisional wounds | Identified a specific subpopulation of macrophages with a high expression of the lipid receptor Trem2 | [122] |

| 4 | Sommerfeld et al. | UBM and PCL | Murine volumetric muscle injuries | The macrophage phenotypes associated with regeneration were defined as R1 (phagocytic F4/80+CD301b+CD9−CD206+) and R2 (non-phagocytic F4/80+CD301b+CD9+CD11c+). CD301b−CD9hi macrophages were related to fibrosis, which were dependent on IL-17 signaling and associated with autoimmunity | [123] |

| 5 | Hu et al. | Electrospun scaffolds | Murine skin excisional wounds | Immune cells including macrophages and T cells showed great heterogeneity. Topography of scaffolds controls the T cell response | [124] |

| 6 | Moore et al. | ECM and PCL | Murine volumetric muscle injuries | Implanted ECM scaffolds accelerated germinal center formation in spleen and lymph nodes while PCL scaffolds prolonged the appearance time of B cells and induces B cell antigen presentation and fibrosis | [125] |

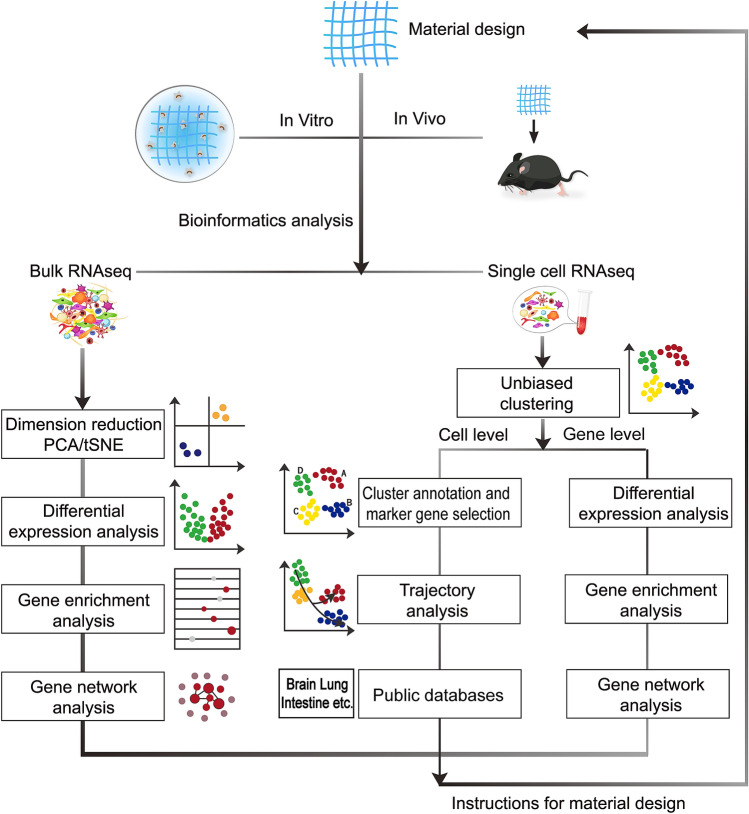

High-throughput sequencing techniques such as bulk tissue RNA sequencing (bulk RNA-seq), scRNA-seq and proteomics can provide massive information on the gene and protein expression profiles of tissue surrounding scaffolds. A brief workflow that can be used in studying scaffold-induced micro-environment using sequencing techniques is shown in Fig. 1 [105, 126]. After in vitro and in vivo evaluation of the biomaterial, harvested samples can be used for bulk RNA-seq, which reveals the differences in gene expression between groups, function of enriched gene sets, signaling pathways for enriched genes, as well as the interplay among them. For scRNA-seq, besides gene level analysis as listed above, cellular analysis including defining cell identity and states, discovering new cell types, and generating pseudotime trajectories can be realized [123, 127]. So far, studies that use scRNA-seq technique to explore host response to biomaterials are in their infancy. Future developments in spatiotemporal profiling of single cells will aid in in-depth understanding of the communication among immune cells, stem cells, and other cell types in regeneration or fibrosis induced by biomaterials [26, 128].

Fig. 1.

A brief workflow that shows how sequencing techniques can be used in studying scaffold-induced micro-environment. After in vitro and in vivo evaluation of the biomaterial, harvested samples can be used for bulk RNA-seq. Through the analysis of PCA or tSNE dimensional-reduction data, gene expression differences between groups, gene functions, signaling pathways and gene network can be interpreted. For scRNA-seq, besides gene level analysis as listed above, we can also analyze from cell level including identifying subpopulations, defining cell states, inferring cell developmental trajectories over the course of a dynamic process and building public databases of important organs. These results may provide better instructions for material design.

Conclusion

The foreign body response consists of a series of biological reactions. The implanted biomaterials, together with immune cells, local tissue environment constitute the local immune micro-environment. The communication between and within cell populations through receptor-ligand interactions and the secretion of molecules and factors forms a signal network, which determines different outcomes of tissue repair or fibrosis. Implantation of synthetic and biological materials usually induce divergent immune micro-environments. By regulating the physical and chemical properties of synthetic and biological scaffolds, materials are designed to provide immune micro-environments that mitigate fibrosis and render the recruited cells polarize towards regenerative phenotypes. In recent years, new technologies like scRNA-seq open a new avenue to identify the rare populations of immune cells that may be activated by biomaterial implants and to examine global transcriptomic changes in different sub-populations of immune cells, which had not been possible with existing technologies. With the help of high-throughput sequencing techniques, massive information on the gene and protein expression profiles of tissue surrounding scaffolds can be obtained to elucidate scaffold-induced micro-environment. Understanding the immune response against biomaterials will aid in the efficient design of biomaterials.

Acknowledgements

C.H. acknowledges funding through National Natural Science Foundation of China (81970965), Research Funding from West China School/Hospital of Stomatology Sichuan University, No. RCDWJS2022-(3) and Sichuan University postdoctoral interdisciplinary Innovation Fund.

National Natural Science Foundation of China, 81,970,965,Chen Hu, Research Funding from West China School/Hospital of Stomatology Sichuan University, No. RCDWJS2022-(3), Chen Hu, National Postdoctoral Program for Innovative Talents.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest related to this manuscript.

Ethical statement

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Nanyan Bian and Chenyu Chu have contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Jie Lin, Email: 84204362@qq.com.

Chen Hu, Email: 616266702@qq.com.

References

- 1.Anderson JM, Rodriguez A, Chang DT. Foreign body reaction to biomaterials. Semin Immunol. 2008;20:86–100. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kastellorizios M, Tipnis N, Burgess DJ. Foreign body reaction to subcutaneous implants. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2015;865:93–108. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-18603-0_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nour S, Baheiraei N, Imani R, Khodaei M, Alizadeh A, Rabiee N, et al. A review of accelerated wound healing approaches: biomaterial- assisted tissue remodeling. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2019;30:120. doi: 10.1007/s10856-019-6319-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Massaro MS, Pálek R, Rosendorf J, Červenková L, Liška V, Moulisová V. Decellularized xenogeneic scaffolds in transplantation and tissue engineering: Immunogenicity versus positive cell stimulation. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2021;127:112203. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2021.112203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samojlik MM, Stabler CL. Designing biomaterials for the modulation of allogeneic and autoimmune responses to cellular implants in type 1 diabetes. Acta Biomater. 2021;133:87–101. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2021.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sadtler K, Singh A, Wolf MT, Wang X, Pardoll DM, Elisseeff JH. Design, clinical translation and immunological response of biomaterials in regenerative medicine. Nat Rev Mater. 2016;1:16040. doi: 10.1038/natrevmats.2016.40. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang H, Yang B, Zhang K, Pan Q, Yuan W, Li G, et al. Immunoregulation of macrophages by dynamic ligand presentation via ligand-cation coordination. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1696. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09733-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu W, Li J, Cheng M, Wang Q, Qian Y, Yeung KWK, et al. A surface-engineered polyetheretherketone biomaterial implant with direct and immunoregulatory antibacterial activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Biomaterials. 2019;208:8–20. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu R, Zhu X, Zhu Y, Wang Z, He X, Wu Z, et al. Immunomodulatory layered double hydroxide nanoparticles enable neurogenesis by targeting transforming growth factor-β receptor 2. ACS Nano. 2021;15:2812–2830. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c08727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng YF, Gu XN, Witte F. Biodegradable metals. Mater Sci Eng R Rep. 2014;77:1–34. doi: 10.1016/j.mser.2014.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alshemary AZ, Engin Pazarceviren A, Tezcaner A, Evis Z. Fe(3+) /SeO42(-) dual doped nano hydroxyapatite: A novel material for biomedical applications. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater. 2018;106:340–352. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.33838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rowley AT, Nagalla RR, Wang SW, Liu WF. Extracellular matrix-based strategies for immunomodulatory biomaterials engineering. Adv Healthc Mater. 2019;8:e1801578. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201801578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin KE, García AJ. Macrophage phenotypes in tissue repair and the foreign body response: implications for biomaterial-based regenerative medicine strategies. Acta Biomater. 2021;133:4–16. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2021.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li J, Jiang X, Li H, Gelinsky M, Gu Z. Tailoring materials for modulation of macrophage fate. Adv Mater. 2021;33:e2004172. doi: 10.1002/adma.202004172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McWhorter FY, Davis CT, Liu WF. Physical and mechanical regulation of macrophage phenotype and function. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2015;72:1303–1316. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1796-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hotchkiss KM, Reddy GB, Hyzy SL, Schwartz Z, Boyan BD, Olivares-Navarrete R. Titanium surface characteristics, including topography and wettability, alter macrophage activation. Acta Biomater. 2016;31:425–434. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang J, Li Z, Wang H, Wang Y, Carlson MA, Teusink MJ, et al. Expanded 3D nanofiber scaffolds: cell penetration, neovascularization, and host response. Adv Healthc Mater. 2016;5:2993–3003. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201600808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chu C, Liu L, Rung S, Wang Y, Ma Y, Hu C, et al. Modulation of foreign body reaction and macrophage phenotypes concerning microenvironment. J Biomed Mater Res, Part A. 2020;108:127–135. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.36798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodrigues M, Gurtner G. Black, white, and gray: macrophages in skin repair and disease. Curr Pathobiol Rep. 2017;5:333–342. doi: 10.1007/s40139-017-0152-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barman PK, Pang J, Urao N, Koh TJ. Skin wounding-induced monocyte expansion in mice is not abrogated by IL-1 receptor 1 deficiency. J Immunol. 2019;202:2720–2727. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1801481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sica A, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and polarization: in vivo veritas. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:787–795. doi: 10.1172/JCI59643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Locati M, Curtale G, Mantovani A. Diversity, mechanisms, and significance of macrophage plasticity. Annu Rev Pathol. 2020;15:123–147. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-012418-012718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bosurgi L, Cao YG, Cabeza-Cabrerizo M, Tucci A, Hughes LD, Kong Y, et al. Macrophage function in tissue repair and remodeling requires IL-4 or IL-13 with apoptotic cells. Science. 2017;356:1072–1076. doi: 10.1126/science.aai8132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shook B, Xiao E, Kumamoto Y, Iwasaki A, Horsley V. CD301b+ macrophages are essential for effective skin wound healing. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:1885–1891. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.05.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shook BA, Wasko RR, Rivera-Gonzalez GC, Salazar-Gatzimas E, Lopez-Giraldez F, Dash BC, et al. Myofibroblast proliferation and heterogeneity are supported by macrophages during skin repair. Science. 2018;362:eaar2971. doi: 10.1126/science.aar2971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stuart T, Butler A, Hoffman P, Hafemeister C, Papalexi E, Mauck WM, et al. Comprehensive integration of single-cell data. Cell. 2019;177:1888–902e21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu H, Han S, Wu B, Du X, Sheng Z, Lin J, et al. Single-cell mass cytometry reveals in vivo immunological response to surgical biomaterials. Appl Mater Today. 2019;16:169–178. doi: 10.1016/j.apmt.2019.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perciani CT, MacParland SA. Lifting the veil on macrophage diversity in tissue regeneration and fibrosis. Sci Immunol. 2019;4:eaaz0749. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaz0749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Young AMH, Kumasaka N, Calvert F, Hammond TR, Knights A, Panousis N, et al. A map of transcriptional heterogeneity and regulatory variation in human microglia. Nat Genet. 2021;53:861–868. doi: 10.1038/s41588-021-00875-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Franz S, Rammelt S, Scharnweber D, Simon JC. Immune responses to implants - a review of the implications for the design of immunomodulatory biomaterials. Biomaterials. 2011;32:6692–6709. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.05.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rahmati M, Silva EA, Reseland JE, Heyward CA, Haugen HJ. Biological responses to physicochemical properties of biomaterial surface. Chem Soc Rev. 2020;49:5178–224. doi: 10.1039/D0CS00103A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frazão LP, de Vieira CJ, Neves NM. In vivo evaluation of the biocompatibility of biomaterial device. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1250:109–24. doi: 10.1007/978-981-15-3262-7_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodrigues M, Kosaric N, Bonham CA, Gurtner GC. Wound healing: a cellular perspective. Physiol Rev. 2019;99:665–706. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00067.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klopfleisch R, Jung F. The pathology of the foreign body reaction against biomaterials. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2017;105:927–940. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.35958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Veiseh O, Vegas AJ. Domesticating the foreign body response: recent advances and applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2019;144:148–161. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2019.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Galli SJ, Borregaard N, Wynn TA. Phenotypic and functional plasticity of cells of innate immunity: macrophages, mast cells and neutrophils. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:1035–1044. doi: 10.1038/ni.2109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sorokin L. The impact of the extracellular matrix on inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:712–723. doi: 10.1038/nri2852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mosser DM, Edwards JP. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:958–969. doi: 10.1038/nri2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klopfleisch R. Macrophage reaction against biomaterials in the mouse model - Phenotypes, functions and markers. Acta Biomater. 2016;43:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2016.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lai YS, Wahyuningtyas R, Aui SP, Chang KT. Autocrine VEGF signalling on M2 macrophages regulates PD-L1 expression for immunomodulation of T cells. J Cell Mol Med. 2019;23:1257–1267. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.14027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ferrante CJ, Pinhal-Enfield G, Elson G, Cronstein BN, Hasko G, Outram S, et al. The adenosine-dependent angiogenic switch of macrophages to an M2-like phenotype is independent of interleukin-4 receptor alpha (IL-4Rα) signaling. Inflammation. 2013;36:921–931. doi: 10.1007/s10753-013-9621-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okuno Y, Nakamura-Ishizu A, Kishi K, Suda T, Kubota Y. Bone marrow-derived cells serve as proangiogenic macrophages but not endothelial cells in wound healing. Blood. 2011;117:5264–5272. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-330720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brodbeck WG, Shive MS, Colton E, Nakayama Y, Matsuda T, Anderson JM. Influence of biomaterial surface chemistry on the apoptosis of adherent cells. J Biomed Mater Res. 2001;55:661–668. doi: 10.1002/1097-4636(20010615)55:4<661::AID-JBM1061>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anderson JM, McNally AK. Biocompatibility of implants: lymphocyte/macrophage interactions. Semin Immunopathol. 2011;33:221–233. doi: 10.1007/s00281-011-0244-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li AG, Quinn MJ, Siddiqui Y, Wood MD, Federiuk IF, Duman HM, et al. Elevation of transforming growth factor beta (TGFbeta) and its downstream mediators in subcutaneous foreign body capsule tissue. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;82:498–508. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robotti F, Sterner I, Bottan S, Monne Rodriguez JM, Pellegrini G, Schmidt T, et al. Microengineered biosynthesized cellulose as anti-fibrotic in vivo protection for cardiac implantable electronic devices. Biomaterials. 2020;229:119583. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cherry C, Maestas DR, Han J, Andorko JI, Cahan P, Fertig EJ, et al. Computational reconstruction of the signalling networks surrounding implanted biomaterials from single-cell transcriptomics. Nat Biomed Eng. 2021;5:1228–1238. doi: 10.1038/s41551-021-00770-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li CGC, Fitzpatric V, Ibrahim A, Zwierstra MJ, et al. Design of biodegradable, implantable devices towards clinical translation. Nat Rev Mater. 2019;5:61–81. doi: 10.1038/s41578-019-0150-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gieseck RL, Wilson MS, Wynn TA. Type 2 immunity in tissue repair and fibrosis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18:62–76. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sadtler K, Estrellas K, Allen BW, Wolf MT, Fan H, Tam AJ, et al. Developing a pro-regenerative biomaterial scaffold microenvironment requires T helper 2 cells. Science. 2016;352:366–370. doi: 10.1126/science.aad9272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chung L, Maestas D R, Jr., Lebid A, Mageau A, Rosson G D, Wu X, et al. Interleukin 17 and senescent cells regulate the foreign body response to synthetic material implants in mice and humans. Sci Transl Med. 2020;12(539). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Sadtler K, Wolf MT, Ganguly S, Moad CA, Chung L, Majumdar S, et al. Divergent immune responses to synthetic and biological scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2019;192:405–415. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Farah S, Doloff JC, Muller P, Sadraei A, Han HJ, Olafson K, et al. Long-term implant fibrosis prevention in rodents and non-human primates using crystallized drug formulations. Nat Mater. 2019;18:892–904. doi: 10.1038/s41563-019-0377-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chu C, Deng J, Sun X, Qu Y, Man Y. Collagen membrane and immune response in guided bone regeneration: recent progress and perspectives. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2017;23:421–435. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2016.0463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang S, Liu Y, Zhang X, Zhu D, Qi X, Cao X, et al. Prostaglandin E2 hydrogel improves cutaneous wound healing via M2 macrophages polarization. Theranostics. 2018;8:5348–5361. doi: 10.7150/thno.27385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Veiseh O, Doloff JC, Ma M, Vegas AJ, Tam HH, Bader AR, et al. Size- and shape-dependent foreign body immune response to materials implanted in rodents and non-human primates. Nat Mater. 2015;14:643–651. doi: 10.1038/nmat4290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Luu TU, Gott SC, Woo BW, Rao MP, Liu WF. Micro- and Nanopatterned topographical cues for regulating macrophage cell shape and phenotype. ACS Appl Mater Interface. 2015;7:28665–28672. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b10589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guo R, Merkel AR, Sterling JA, Davidson JM, Guelcher SA. Substrate modulus of 3D-printed scaffolds regulates the regenerative response in subcutaneous implants through the macrophage phenotype and Wnt signaling. Biomaterials. 2015;73:85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sun G. Pro-regenerative hydrogel restores scarless skin during cutaneous wound healing. Adv Healthc Mater. 2017;6:1700659. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201700659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McWhorter FY, Wang T, Nguyen P, Chung T, Liu WF. Modulation of macrophage phenotype by cell shape. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:17253–17258. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308887110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Friedemann M, Kalbitzer L, Franz S, Moeller S, Schnabelrauch M, Simon J-C, et al. Instructing human macrophage polarization by stiffness and glycosaminoglycan functionalization in 3D collagen networks. Adv Healthc Mater. 2017;6:1600967. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201600967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Abebayehu D, Spence AJ, McClure MJ, Haque TT, Rivera KO, Ryan JJ. Polymer scaffold architecture is a key determinant in mast cell inflammatory and angiogenic responses. J Biomed Mater Res Part A. 2019;107:884–892. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.36605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Swartzlander MD, Barnes CA, Blakney AK, Kaar JL, Kyriakides TR, Bryant SJ. Linking the foreign body response and protein adsorption to PEG-based hydrogels using proteomics. Biomaterials. 2015;41:26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alapure BV, Lu Y, He M, Chu CC, Peng H, Muhale F, et al. Accelerate healing of severe burn wounds by mouse bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-seeded biodegradable hydrogel scaffold synthesized from arginine-based poly(ester amide) and chitosan. Stem Cell Dev. 2018;27:1605–1620. doi: 10.1089/scd.2018.0106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sok MCP, Baker N, McClain C, Lim HS, Turner T, Hymel L, et al. Dual delivery of IL-10 and AT-RvD1 from PEG hydrogels polarize immune cells towards pro-regenerative phenotypes. Biomaterials. 2021;268:120475. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yan H, Hjorth M, Winkeljann B, Dobryden I, Lieleg O, Crouzier T. Glyco-modification of mucin hydrogels to investigate their immune activity. ACS Appl Mater Interface. 2020;12:19324–19336. doi: 10.1021/acsami.0c03645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dong L, Li L, Song Y, Fang Y, Liu J, Chen P, et al. MSC-derived immunomodulatory extracellular matrix functionalized electrospun fibers for mitigating foreign-body reaction and tendon adhesion. Acta Biomater. 2021;133:280–296. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2021.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.He M, Sun L, Fu X, McDonough SP, Chu CC. Biodegradable amino acid-based poly(ester amine) with tunable immunomodulating properties and their in vitro and in vivo wound healing studies in diabetic rats' wounds. Acta Biomater. 2019;84:114–132. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jiang Y, Zhao W, Xu S, Wei J, Lasaosa FL, He Y, et al. Bioinspired design of mannose-decorated globular lysine dendrimers promotes diabetic wound healing by orchestrating appropriate macrophage polarization. Biomaterials. 2022;280:121323. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.121323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Welch NG, Mukherjee S, Hossain MA, Praveen P, Werkmeister JA, Wade JD, et al. Coatings releasing the relaxin peptide analogue B7–33 reduce fibrotic encapsulation. ACS Appl Mater Interface. 2019;11:45511–45519. doi: 10.1021/acsami.9b17859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chu C, Deng J, Xiang L, Wu Y, Wei X, Qu Y, et al. Evaluation of epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) cross-linked collagen membranes and concerns on osteoblasts. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2016;67:386–394. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2016.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chu C, Deng J, Cao C, Man Y, Qu Y. Evaluation of epigallocatechin-3-gallate modified collagen membrane and concerns on schwann cells. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:9641801. doi: 10.1155/2017/9641801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chu C, Deng J, Hou Y, Xiang L, Wu Y, Qu Y, et al. Application of PEG and EGCG modified collagen-base membrane to promote osteoblasts proliferation. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2017;76:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2017.02.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chu C, Deng J, Man Y, Qu Y. Green tea extracts epigallocatechin-3-gallate for different treatments. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:5615647. doi: 10.1155/2017/5615647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chu C, Deng J, Man Y, Qu Y. Evaluation of nanohydroxyapaptite (nano-HA) coated epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) cross-linked collagen membranes. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2017;78:258–264. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2017.04.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chu C, Liu L, Wang Y, Wei S, Wang Y, Man Y, et al. Macrophage phenotype in the epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG)-modified collagen determines foreign body reaction. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2018;12:1499–1507. doi: 10.1002/term.2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chu C, Wang Y, Wang Y, Yang R, Liu L, Rung S, et al. Evaluation of epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) modified collagen in guided bone regeneration (GBR) surgery and modulation of macrophage phenotype. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2019;99:73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2019.01.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chu C, Liu L, Wang Y, Yang R, Hu C, Rung S, et al. Evaluation of epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG)-modified scaffold determines macrophage recruitment. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2019;100:505–513. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2019.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Guo Y, Wang X, Shen Y, Dong K, Shen L, Alzalab AAA. Research progress, models and simulation of electrospinning technology: a review. J Mater Sci. 2022;57:58–104. doi: 10.1007/s10853-021-06575-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Garg K, Pullen NA, Oskeritzian CA, Ryan JJ, Bowlin GL. Macrophage functional polarization (M1/M2) in response to varying fiber and pore dimensions of electrospun scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2013;34:4439–4451. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.02.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Law JX, Liau LL, Saim A, Yang Y, Idrus R. Electrospun collagen nanofibers and their applications in skin tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2017;14:699–718. doi: 10.1007/s13770-017-0075-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sharma R, Kumar S, Bhawna S, Gupta A, Dheer N, Jain P. An insight of nanomaterials in tissue engineering from fabrication to applications. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2022;19:927–960. doi: 10.1007/s13770-022-00459-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Venugopal D, Vishwakarma S, Kaur I, Samavedi S. Electrospun fiber-based strategies for controlling early innate immune cell responses: towards immunomodulatory mesh designs that facilitate robust tissue repair. Acta Biomater. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2022.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.da Silva EZ, Jamur MC, Oliver C. Mast cell function: a new vision of an old cell. J Histochem Cytochem Off J Histochem Soc. 2014;62:698–738. doi: 10.1369/0022155414545334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zandstra J, Hiemstra C, Petersen AH, Zuidema J, van Beuge MM, Rodriguez S, et al. Microsphere size influences the foreign body reaction. Eur Cell Mater. 2014;28:335–347. doi: 10.22203/eCM.v028a23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chen S, Shi J, Zhang M, Chen Y, Wang X, Zhang L, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-laden anti-inflammatory hydrogel enhances diabetic wound healing. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18104. doi: 10.1038/srep18104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sontyana AG, Mathew AP, Cho KH, Uthaman S, Park IK. Biopolymeric in situ hydrogels for tissue engineering and bioimaging applications. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2018;15:575–590. doi: 10.1007/s13770-018-0159-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Samuel CS, Royce SG, Hewitson TD, Denton KM, Cooney TE, Bennett RG. Anti-fibrotic actions of relaxin. Br J Pharmacol. 2017;174:962–976. doi: 10.1111/bph.13529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Supp DM, Boyce ST. Engineered skin substitutes: practices and potentials. Clin Dermatol. 2005;23:403–412. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2004.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Price RD, Das-Gupta V, Leigh IM, Navsaria HA. A comparison of tissue-engineered hyaluronic acid dermal matrices in a human wound model. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2985–2995. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Burd A, Chiu T. Allogenic skin in the treatment of burns. Clin Dermatol. 2005;23:376–387. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2004.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Shevchenko RV, James SL, James SE. A review of tissue-engineered skin bioconstructs available for skin reconstruction. J R Soc Interface. 2010;7:229–258. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2009.0403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Naves LB, Dhand C, Almeida L, Rajamani L, Ramakrishna S. In vitro skin models and tissue engineering protocols for skin graft applications. Essay Biochem. 2016;60:357–369. doi: 10.1042/EBC20160043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Schmitt CM, Moest T, Lutz R, Wehrhan F, Neukam FW, Schlegel KA. Long-term outcomes after vestibuloplasty with a porcine collagen matrix (Mucograft(®) versus the free gingival graft: a comparative prospective clinical trial. Clin Oral Implant Res. 2016;27:e125–e133. doi: 10.1111/clr.12575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ghanaati S, Schlee M, Webber MJ, Willershausen I, Barbeck M, Balic E, et al. Evaluation of the tissue reaction to a new bilayered collagen matrix in vivo and its translation to the clinic. Biomed Mater. 2011;6:015010. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/6/1/015010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mohammadi MH, Obregon R, Ahadian S, Ramon-Azcon J, Radisic M. Engineered muscle tissues for disease modeling and drug screening applications. Curr Pharm Des. 2017;23:2991–3004. doi: 10.2174/1381612823666170215115445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lim WL, Liau LL, Ng MH, Chowdhury SR, Law JX. Current progress in tendon and ligament tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2019;16:549–571. doi: 10.1007/s13770-019-00196-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Palit S, Heuser C, de Almeida GP, Theis FJ, Zielinski CE. Meeting the challenges of high-dimensional single-cell data analysis in immunology. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1515. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.See P, Lum J, Chen J, Ginhoux F. A single-cell sequencing guide for immunologists. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2425. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Spitzer MH, Nolan GP. Mass cytometry: single cells. Many Feature Cell. 2016;165:780–791. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zhang T, Lei T, Yan R, Zhou B, Fan C, Zhao Y, et al. Systemic and single cell level responses to 1 nm size biomaterials demonstrate distinct biological effects revealed by multi-omics atlas. Bioact Mater. 2022;18:199–212. doi: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2022.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chen G, Ning B, Shi T. Single-cell RNA-Seq technologies and related computational data analysis. Front Genet. 2019;10:317. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Li X, Wang CY. From bulk, single-cell to spatial RNA sequencing. Int J Oral Sci. 2021;13:36. doi: 10.1038/s41368-021-00146-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Mereu E, Lafzi A, Moutinho C, Ziegenhain C, McCarthy DJ, Alvarez-Varela A, et al. Benchmarking single-cell RNA-sequencing protocols for cell atlas projects. Nat Biotechnol. 2020;38:747–755. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0469-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Luecken MD, Theis FJ. Current best practices in single-cell RNA-seq analysis: a tutorial. Mol Syst Biol. 2019;15:e8746. doi: 10.15252/msb.20188746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Svensson V, Vento-Tormo R, Teichmann SA. Exponential scaling of single-cell RNA-seq in the past decade. Nat Protoc. 2018;13:599–604. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2017.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Papalexi E, Satija R. Single-cell RNA sequencing to explore immune cell heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18:35–45. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Levitin HM, Yuan J, Sims PA. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of tumor heterogeneity. Trends in Cancer. 2018;4:264–268. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Liu X, Chen W, Zhu G, Yang H, Li W, Luo M, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing identifies an Il1rn(+)/Trem1(+) macrophage subpopulation as a cellular target for mitigating the progression of thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection. Cell Discov. 2022;8:11. doi: 10.1038/s41421-021-00362-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Guerrero-Juarez CF, Dedhia PH, Jin S, Ruiz-Vega R, Ma D, Liu Y, et al. Single-cell analysis reveals fibroblast heterogeneity and myeloid-derived adipocyte progenitors in murine skin wounds. Nat Commun. 2019;10:650. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-08247-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Tan L, Sandrock I, Odak I, Aizenbud Y, Wilharm A, Barros-Martins J, et al. Single-cell transcriptomics identifies the adaptation of scart1(+) vgamma6(+) T cells to skin residency as activated effector cells. Cell Rep. 2019;27:3657–71 e4. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.05.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Zeis P, Lian M, Fan X, Herman JS, Hernandez DC, Gentek R, et al. In situ maturation and tissue adaptation of type 2 innate lymphoid cell progenitors. Immunity. 2020;53:775–92 e9. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Joost S, Zeisel A, Jacob T, Sun X, La Manno G, Lonnerberg P, et al. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals that differentiation and spatial signatures shape epidermal and hair follicle heterogeneity. Cell Syst. 2016;3:221–37 e9. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2016.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Joost S, Annusver K, Jacob T, Sun X, Dalessandri T, Sivan U, et al. The molecular anatomy of mouse skin during hair growth and rest. Cell Stem Cell. 2020;26:441–57.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2020.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wright SC, Canizal MCA, Benkel T, Simon K, Le Gouill C, Matricon P, et al. FZD5 is a galphaq-coupled receptor that exhibits the functional hallmarks of prototypical GPCRs. Sci Signal. 2018;11:eaar5536. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aar5536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Williams DW, Greenwell-Wild T, Brenchley L, Dutzan N, Overmiller A, Sawaya AP, et al. Human oral mucosa cell atlas reveals a stromal-neutrophil axis regulating tissue immunity. Cell. 2021;184:4090–104.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Jaitin DA, Kenigsberg E, Keren-Shaul H, Elefant N, Paul F, Zaretsky I, et al. Massively parallel single-cell RNA-seq for marker-free decomposition of tissues into cell types. Science. 2014;343:776–779. doi: 10.1126/science.1247651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Björklund ÅK, Forkel M, Picelli S, Konya V, Theorell J, Friberg D, et al. The heterogeneity of human CD127+ innate lymphoid cells revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Nat Immunol. 2016;17:451–460. doi: 10.1038/ni.3368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Gaublomme JT, Yosef N, Lee Y, Gertner RS, Yang LV, Wu C, et al. Single-cell genomics unveils critical regulators of Th17 Cell pathogenicity. Cell. 2015;163:1400–1412. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Chen B, Zhu L, Yang S, Su W. Unraveling the heterogeneity and ontogeny of dendritic cells using single-cell RNA Sequencing. Front Immunol. 2021;12:711329. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.711329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Huang J, Fan C, Chen Y, Ye J, Yang Y, Tang C, et al. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals functionally distinct biomaterial degradation-related macrophage populations. Biomaterials. 2021;277:121116. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.121116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Henn D, Chen K, Fehlmann T, Trotsyuk AA, Sivaraj D, Maan ZN, et al. Xenogeneic skin transplantation promotes angiogenesis and tissue regeneration through activated trem2(+) macrophages. Sci Adv. 2021;7:eabi4528. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abi4528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Sommerfeld SD, Cherry C, Schwab RM, Chung L, Maestas DR, Laffont P, et al. Interleukin-36 gamma-producing macrophages drive IL-17-mediated fibrosis. Sci Immunol. 2019;4:eaax4783. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aax4783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Hu C, Chu C, Liu L, Wang C, Jin S, Yang R, et al. Dissecting the microenvironment around biosynthetic scaffolds in murine skin wound healing. Sci Adv. 2021;7:eabf0787. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abf0787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Moore EM, Maestas DR, Cherry CC, Garcia JA, Comeau HY, Davenport Huyer L, et al. Biomaterials direct functional B cell response in a material-specific manner. Sci Adv. 2021;7:eabi5830. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abj5830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Andrews TS, Kiselev VY, McCarthy D, Hemberg M. Tutorial: guidelines for the computational analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing data. Nat Protoc. 2021;16:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41596-020-00409-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Aldridge S, Teichmann SA. Single cell transcriptomics comes of age. Nat Commun. 2020;11:4307. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18158-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Peng G, Suo S, Cui G, Yu F, Wang R, Chen J, et al. Molecular architecture of lineage allocation and tissue organization in early mouse embryo. Nature. 2019;572:528–532. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1469-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]