Abstract

Varying reports across different laboratories or across different analysers in the same lab for the same sample is not an uncommon phenomena. Experts call this a lack of harmonization. A test that is harmonized provides the same results regardless of the manufacturer of reagents used or the laboratory where the test is performed. When laboratory tests are not harmonized, the entire continuum of patient care can be affected in a number of ways. Here, we present a case of varying reports for a single serum human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) sample on two different immunoassay platforms for a young female presenting with an abdominopelvic mass. The lab reports for serum hCG for this particular patient showed inconsistent results with the same sample within the same lab. The phenomena behind this was lack of harmonization of test results. We introspect many of the factors responsible for lack of uniformity in hCG results amongst the major ones being with use of antibodies directed against different epitopes of hCG (analyte) and the heterogeneity of the hCG molecule itself. Harmonization is a process to ensure that different clinical testing procedures used by different laboratories give equivalent results. Harmonizing test results will enable healthcare providers to use clinical guidelines with greater confidence for diagnosing disease and managing patients.

Keywords: Case report, Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), Immunoassay, Harmonization

Introduction

The idea behind bringing this case report is to highlight the importance of harmonization of laboratory testing and provide impetus for the profession dealing with laboratory medicine to understand the significance of harmonization universally. The problem of reports differing amongst different platforms with the sample being given at the same time and day is a phenomena known to occur amongst different labs (inter-lab) and also within the same lab on different machines (intra lab). Experts call this a lack of harmonization [1]. A test that is harmonized provides the same results regardless of the manufacturer or lab [1, 2].

Case Description

A 21 year old unmarried female presented to the Surgical Oncology Department with an abdominopelvic mass in April 2020. Examination revealed a bulky uterus corresponding to 28 weeks size and presence of ascites. Ultrasonography revealed mild to moderate ascites and large multilobulated mixed echogenic lesion occupying bilateral adnexa. CT scan revealed grossly enlarged, well demarcated hypodense space occupying lesion at left ovary which could not be visualized separately. Right ovary was compressed with omental caking, multiple peri-pancreatic, mesenteric and perigastric nodes likely to be metastatic. Cytology of ascitic fluid was reported negative for malignancy and histopathology revealed poorly differentiated malignancy.

Immunoassay for tumor markers revealed serum CA 125 of 522.7 U/L, total beta hCG values of 206.06 m IU/ml, AFP at 4.09 ng/ml, CA 19.9 at 13.04 U/ml, CEA at < 0.5 ng/ml and serum LDH as 18304U/L on 14th April 2020. The high values of both CA 125 and total beta hCG in a young patient presented a diagnostic dilemma. CA 125 values are high in epithelial cell ovarian tumors seen in the elderly population while rise of beta hCG points towards a germ cell tumor commonly seen in young patients. A repeat blood sample was asked by the lab for rechecking the level of hCG as the treating surgeon expected it to be on a higher side than the values that were released. What followed left us baffled! The total beta hCG value with the fresh sample sent on 28th April 2020 was now reported as 39 mIU/ml on ADVIA CENTAUR XP chemiluminescence based immunoassay analyser (SIEMENS) without any intervention from the treating clinician in the interim period. The sample was repeated on another chemiluminescence based immunoassay analyser Beckman Coulter Access 2. The total beta hCG value was reported at 110.3 m IU/ml. Noting the significant discrepancy in the values on two different platforms for the same sample, a dilution (1 in 2) for total beta hCG was run on both the instruments to check for hook effect and possible interferences by heterophilic antibodies. The final total beta hCG values (after taking care of multiplication factor for dilution) came at 22.7 m IU/ml on Siemens ADVIA CENTAUR XP platform and as 110 m IU/ml on Beckman Coulter Access2. The same sample was sent to an outside lab where it was run on a dry chemistry platform by Ortho Clinical Diagnostics where the value was reported as 37 m IU/ml. We decided to run urine samples on both the platforms to rule out the presence of heterophilic antibodies as the patient’s family had a business dealing in poultry and farm animals. The urine sample was run neat as well as in dilution despite the fact that urine is not a recommended specimen for hCG on Beckman Coulter Access2 and Siemens ADVIA CENTAUR XP. Urine for hCG was reported as116.4 m IU/mL on Siemens ADVIA CENTAUR XP and 314.3 m IU/mL on Beckman Coulter Access 2. However, urine sample was negative by the rapid card test for hCG. Finally, the patient was operated on 5th May 2020 due to sudden onset of breathlessness secondary to massive ascites. Procedure done was exploratory laparotomy with left salphingo-oopherectomy. Operative findings revealed 20 × 30 cm fragile mucinous left ovarian mass and presence of multiple peritoneal metastases. Immunohistochemistry revealed presence of markers suggestive of ovarian Germ cell tumor. Post-operative serum levels of tumor markers on 12th June were reported as normal with serum AFP, CA 125 and total beta hCG values at 4.76 ng/ml, 15 U/ml and < 0.1 mIU/ml respectively (investigation details tabulated in Table 1).

Table 1.

Investigation details during hospital stay and post-operative period

| Date | Beckman coulter access 2 | Siemens ADVIA CENTAUR XP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum | CA-125 | ThCG | AFP | CEA | CA 19.9 | CA125 | ThCG |

| 14-04-2020 | 206 m IU/ml | 4.09 ng/ml | 0.5 ng/ml | 13.04 U/ml | 522 U/L | – | |

| 28-04-2020 | 110.3 m IU/ml | 39 m IU/ml | |||||

| 28-04-2020 (repeat check in dilution (1:1) | 110 m IU/ml | 22.7 m IU/ml | |||||

| Urine (28-04-2020) | 314.3 m IU/ml | 116 m IU/ml | |||||

| Patient was operated on 05-05-2020 | |||||||

| Blood sample after left salphingo-opherctomy was analysed at a private lab due to onset of Corona pandemic and travel restrictions | |||||||

| 12-06-2020 (post operative) | CA-125 | ThCG | AFP | CEA | |||

| 15 U/ml | < 0.1 m IU/ml | 4.76 ng/ml | – | ||||

Adnexal mass was sent to an outside lab for immunohistochemistry markers which reported features suggestive of Ovarian Germ cell tumour.

Discussion

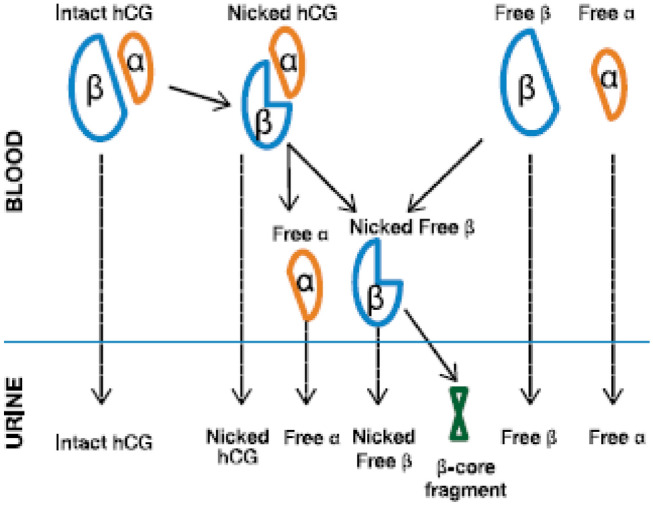

The molecule focused here is total beta hCG measured by chemiluminescence based immunoassay principle on two different platforms: ADVIA CENTAUR XP (Siemens) and Beckman Coulter Access 2. hCG is secreted by the trophoblastic placental cells, a variety of tumors, and the pituitary. hCG, is a heterodimer with a 92 amino acid α-subunit and a β-subunit (hCGβ) containing 145 amino acids. Only the intact hCG αβ-heterodimer is biologically active. hCG exists not only as the intact heterodimer but also as free subunits that are recognized by different hCG assays to a variable degree. There are multiple forms found in the serum and urine during pregnancy including the intact hormone and each of the free subunits [3]. hCG variants are increasingly important for the clinical laboratory to understand because their recognition by immunoassays shows marked inter-assay variability [4]. In a normal pregnancy, the primary morphologic form of the hormone is the native α–β dimer (intact hCG). In early pregnancy from implantation to ~ 3 weeks, the predominant form of hCG is a hyperglycosylated variant (hCG-h) that has additional carbohydrate terminals on the N- and O-linked oligosaccharide side chains. Patients with gestational trophoblastic disease (GTD) and germ cell tumor (GCT) often have increased proportions of hCGβ and hCG-h in their serum. In certain disease states other metabolites of hCG can become predominant forms in circulation [5]. The other forms include Intact hCG (both α and β subunit together), free β hCG, free α hCG, nicked beta hCG together with α subunit of hCG, nicked free beta hCG (Fig. 1) [6]. Enzymic degradation of hCG by tissue or circulating proteases released either from placenta or activated leukocytes produces nicked forms, result in more rapid dissociation into the free alpha- and free beta-hCG subunits. The dissociated and various nicked isoforms are more rapidly cleared from the circulation. Approximately 80 percent of hCG is metabolized by the liver and 20 percent by the kidney [7]. The beta subunit is degraded in the kidney to make a core fragment known as β core fragment (βcf) which is the predominant form in urine and is measured by urine hCG tests. Apart from action of proteases as discussed above, degradation in the proximal renal tubule also results in hCGbn in urine. The rate of enzymic nicking is an important determinant of hCG clearance from the circulation and, hence, directly affects serum and urine concentrations [8]. Nicked forms are more rapidly cleared from the circulation than intact hCG and, due to their comparative abundance, more greatly affect urine than serum measurements [9]. The urine concentrations of intact hCG and the free beta-subunit of hCG are similar to those in serum. However, total hCG in urine also includes hCGbcf, which is often present in concentrations similar to those of intact hCG. As a result, total hCG in urine is often higher than in serum, which includes only minute levels of hCGbcf. Urine total hCG concentrations, though strongly correlated to those in serum, vary considerably due to greater heterogeneity of isoforms present and the diluting effects of the kidneys. Hence, determination of urinary hCG does not reflect hCG-producing disease status as accurately as serum measurement [10].

Fig. 1.

Metabolism of variants forms of hCG (adapted from Cole LA, Clinical Chemistry)

Apart from fast clearance of nicked forms from serum, immunoreactivity in some immunoassays for the nicked forms is reduced or lost. Although most of the commercially available total hCG assays are able to detect both hCGn and hCGbn, relative detection is variable and is a significant source of measurement discrepancy between assays.

For hormones composed of subunits (e.g. gonadotrophins) both the intact and free subunits can circulate in blood. Immunometric assays can be made specific for intact molecules by pairing an antibody specific for the α-β bridge site of the subunit with a second subunit specific for the β subunit. Assays using these two antibody pairs retain the two antibody low cross -reactivity needed for measuring gonadotropins and do not react with the free subunit forms of the hormones. It is notable that there are many different combinations of antibodies used in commercial assays [11]. This results in heterogeneous results with as much as a 50-fold difference in immunoassay results [12, 13]. This is clinically relevant, particularly when comparing results from different laboratories/instruments. Because of the variable forms of hCG present in malignancy, most hCG assays used in the management of GTN and GCT recognize both intact hCG and hCGβ. Such methods are commonly referred to as “total hCG” assays. Different assays for hCG may produce significantly discrepant results due to the following causes [14, 15]:

epitope recognition by antibodies in the assay

differential response to variant forms of hCG

interferences (e.g. human anti-animal antibodies)

sensitivity and specificity for the medical condition being tested for

linearity of the method

standardization of the assay.

The Beckman Coulter Access 2 total βhCG (5th IS) employs antibodies that recognize immunologically distinct sites on the βsubunit of the molecule measuring virtually all clinically useful variants of the hormone which include intact hCG, the free β-subunit of hCG, nicked intact hCG and the nicked free β subunit of hCG [16].

The ADVIA Centaur Total hCG (ThCG on Siemens XP platform) assay is a two-site sandwich immunoassay using direct chemiluminometric technology, which uses constant amounts of two antibodies specific for different epitopes that are present on both the free β subunit and the β subunit of intact hCG [17].

What happened probably in our case described above was that the sample sent earlier on 14th April 2020 was run on Beckman Coulter immunoassay analyser (Beckman Coulter Access 2) and then unknowingly a fresh sample was run on 28th April on ADVIA Centaur XP (Siemens) immunoassay analyser thereby resulting in gross differences in values noted for hCG. This was an incidental finding which was noted in the case of hCG as a repeat sample run on different immunoassay analyser from the previous one to just recheck the findings of the previously released report.

Between-method variation in total hCG assay results due to analyte heterogeneity and variation in assay specificity is a long-standing and widely recognized problem [18]. This is especially true for samples from patients with gestational trophoblastic disease, germ cell tumors, and other neoplasias, in which higher proportions of free subunits, partially degraded fragments, and abnormally glycosylated variants of hCG may be present [19].

Immunoassays for the measurement of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) have been available for over six decades [20]. The heterogeneity of hCG as discussed above poses an analytical challenge and results in a significant between-method variation [21, 22]. This variation is attributed to the use of different reagent antibody pairs, which will determine the specific hCG variants that are detected, and differences in the secondary standards used by manufacturers to calibrate hCG assays [23]. hCG assays are commercially available that detect only dimeric forms of the hormone (hCG and hCGn), dimeric and hCGβ/hCGβn forms, and the latter plus hCGβcf. To further complicate matters, the detected variants are frequently not measured in equimolar quantities. For oncology purposes, broad and equimolar recognition of isoforms is preferable in order to detect both intact hCG and the free beta-subunit of hCG, as well as nicked and fragment forms derived from the free beta-subunit of hCG. Marked under- or over-reactivity, especially to the free beta-subunit of hCG, is likely the greatest source of interassay variability in serum hCG measurements in oncology [24]. In consideration of the biological and analytical complexities, one can appreciate that the use of hCG as a tumor marker is not a straightforward matter and much more data is needed. Moreover, there is need for a more desirable reference population on whom decision limits in oncology for hCG would be based rather than generalizing the existing reference ranges for antenatal females trimester wise [25]. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of germ cell tumors recommend the measurements of hCG and/or free hCGβ subunit for earlier identification of the residual disease, for the prognostic evaluation and for the post-chemotherapy surveillance. However, the marketed hCG assays are validated and approved only for pregnancy purposes, with the sole exception of the Elecsys ‘hCG + β’ assay (Roche Diagnostics), cleared in Europe for oncological application [26]. Theoretically, the hCG assay design for oncological purposes should fulfil the recommendations of the International Society of Oncology and Biomarkers requiring the use of antibodies displaying an equimolar recognition of both intact hCG and hCGβ monomer [27]. Further analytical requirements should also be considered, such as optimal analytical sensitivity to allow an early tumor detection and low cross-reactivity for luteinizing hormone (LH). It is also important to clearly define the decision limits of hCG for oncologic purposes. There is an urgent need to create awareness amongst health care providers regarding the utility of hCG as a tumor marker and to advocate the clinical use of selective, highly sensitive and precise assays clearly defining the antibodies used and their target epitopes, specifically manufactured for cancer application while dealing with cancer patients.

Lastly, laboratorians may play a very important role in selecting and offering appropriate hCG assays that are fit for the clinical purpose for which they are used. In the present scenario the laboratory professionals hardly get to know why an hCG test was asked for by the clinicians. This becomes all the more important when different immunoassay platforms are available in the same lab so as to ensure running of the samples for hCG of those patients in whom serial monitoring is needed on the same platform to avoid problems due to lack of harmonisation. Some clinicians ask for hCG assays to be capable of detecting hCG and hCGβ [26]. Others have advocated for separate assays that specifically detect hCG and hCGβ due to their potential to provide improved diagnostic sensitivity for patients with testicular cancer [24, 26]. One report identified 9% of laboratories reporting hCG test results as “total hCG” when, in fact, the assays detected only intact hCG and 13% of laboratories reporting results as “intact hCG” when the assay was specific for total hCG [27]. While such reporting errors are unlikely to affect a pregnancy diagnosis, reporting a total hCG result from an intact hCG-specific assay will fail to identify some individuals with malignancy-associated hCG. A contributor to this problem is the manufacturer’s failure to clearly state what hCG variants are detected by their assays.

Harmonization is a process to ensure that different clinical testing procedures used by different laboratories give equivalent results. It is a concept to be applied with an aim to bring about greater consistency in reporting. Harmonizing test results will enable healthcare providers to use clinical guidelines with greater confidence for diagnosing disease and managing patients. When laboratory tests are not harmonized, the entire continuum of patient care gets affected in profound but not always obvious ways. Harmonized laboratory tests allow more accurate decision making by physicians, reducing diagnostic dilemmas and treatment errors [28]. Very crucial factor in the implementation of guidelines using biomarkers is the assumption that results across all testing sites are comparable, but unfortunately this important assumption is rarely questioned.

At the laboratory level the problems arising due to lack of harmonisation with respect to hCG can be minimized by:

Clarity about what is being measured

Clarity about clinical origins of sample: oncological or reproductive

Avoidance of different immunoassay platforms in cases of serial sampling of the same patient.

Optimum use of delta check so as to avoid unnecessary discrepancies in results

Better communication between lab incharges and treating physician.

Clinical laboratory tests are essential for providing high-quality healthcare, but test results can be misinterpreted unless steps are taken to ensure that the results generated are consistent, irrespective of where they are performed.

Acknowledgements

We are extremely thankful to the patient, technical staff and all concerned individuals with respect to patient management.

Author contributions

MM, AB and MK conceptualised the study and reviewed literature for the same. MM wrote the first draft and MM, AB, MK, SK and JP approved of the final version. JP was the treating physician.

Funding

None.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical Approval

Not required for case studies from our institute. However, written informed consent has been taken from the patient concerned for publishing the data in medical journals.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Miller WG, Tate JR, Barth JH. Harmonisation: The sample, the measurement and the report. Ann Lab Med. 2014;34:187–197. doi: 10.3343/alm.2014.34.3.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sacks DB. In: Tietz textbook of clinical chemistry and molecular diagnostics. 5. Burtis CA, Ashwood ER, Bruns DE, editors. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2012. p. 719. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stenman UH, Tiitinen A, Alfthan H, et al. The classification, functions and clinical use of different isoforms of HCG. Hum Reprod Update. 2006;12:769. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dml029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greene DN, Petrie MS, Pyle AL. Performance characteristics of the Beckman Coulter totalβhCG (5th IS) assay. Clin Chim Acta. 2015;439:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2014.09.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fournier T, Guibourdenche J, Evain-Brion D. Review: hCGs: Different sources of production, different glycoforms and functions. Placenta. 2015;36:S60–S65. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cole LA. hCG, five independent molecules. Clin Chim Acta Int J Clin Chem. 2012;413:48–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2011.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cole LA. Immunoassay of human chorionic gonadotropin, its free subunits and metabolites. Clin Chem. 1997;43(12):2233–2243. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/43.12.2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mann K, Saller B, Hoermann R. Clinical use of HCG and hCG beta determinations. Scand J Clin Lab Investig Suppl. 1993;216:97. doi: 10.1080/00365519309086910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McChesney R, Wilcox AJ, O'Connor JF, Weinberg CR, Baird DD, Schlatterer JP, et al. Intact HCG, free HCG beta subunit and HCG beta core fragment: longitudinal patterns in urine during early pregnancy. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(4):928. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nisula BC, Blithe DL, Akar A, Lefort G, Wehmann RE. Metabolic fate of human choriogonadotropin. J Steroid Biochem. 1989;33:733. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(89)90485-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stenman UH, Alfthan H. Determination of human chorionic gonadotropin. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;27:783. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2013.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sturgeon CM, Berger P, Bidart J-M, Birken S, Burns C, Norman RJ, et al. Differences in recognition of the 1st WHO international reference reagents for hCG-related isoforms by diagnostic immunoassays for human chorionic gonadotropin. Clin Chem. 2009;55:1484–1491. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.124578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whittington J, Fantz CR, McCudden GAM, C, Mullins R, Sokoll L, , et al. The analytical specificity of human chorionic gonadotropin assays determined using WHO International Reference Reagents. Clin Chim Acta. 2010;411:81–85. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pretorius C, du Toit S, Wilgen U, Klingberg S, Jones M, Ungerer PJJ, et al. How comparable are total human chorionic gonadotropin (hCGt) tumour markers assays. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2020;58:438–444. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2019-0457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stenman UH. Pitfalls in hormone determinations. Best Pract Clin Endocrinal Metab. 2013;27:743. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beckman Coulter Access Immunoassay systems IFU. 2020 Beckman coulter Inc. All rights reserved. Access Total βhCG 5th IS Beta hCG Reference A85264.

- 17.ADVIA CENTAUR, Ready Pack and ACS: 180 are trademarks of Siemens Health care Diagnostics 2008 Siemens Health care Diagnostics Inc. All rights reserved.

- 18.Mitchell H, Seckl MJ. Discrepancies between commercially available immunoassays in the detection of tumour-derived hCG. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2007;260–262:310. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stenman U, Alfthan H, Hotakainen K. Human chorionic gonadotropin in cancer. Clin Biochem. 2004;37:549–561. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2004.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bock JL. hCG assays. A plea for uniformity. Am J Clin Pathol. 1990;93(3):432. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/93.3.432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berger P, Sturgeon CM, Bidart JM, Paus E, Gerth R, Niang M, et al. The ISOBM TD-7 workshop on hCG and related molecules. Towards user-oriented standardization of pregnancy and tumor diagnosis: assignment of epitopes to the three-dimensional structure of diagnostically and commercially relevant monoclonal antibodies directed against human chorionic gonadotropin and derivatives. Tumour Biol. 2002;23:1–38. doi: 10.1159/000048686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sturgeon CM, Berger P, Bidart JM, Birken S, Burns C, Norman RJ, Stenman UH. Differences in recognition of the 1st WHO international reference reagents for hCG-related isoforms by diagnostic immunoassays for human chorionic gonadotropin. Clin Chem. 2009;55:1484–1491. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2009.124578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Armbuster D, Donnelly J. Harmonization of clinical laboratory test results: the role of the IVD industry. JIFCC. 2016;27(2):37–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferraro S, Trevisiol C, Gion M, Mauro P. Human chorionic gonadotropin assays for testicular tumors: closing the gap between clinical and laboratory practice. Clin Chem. 2018;64(2):270–278. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2017.275263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berger P, Sturgeon C. Human chorionic gonadotropin isoforms and their epitopes: diagnostic utility in pregnancy and cancer. Expert Opin Med Diagn. 2008;2:1347. doi: 10.1517/17530050802558907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferraro S, Panteghini M. A step forward in identifying the right human chorionic gonadotropin assay for testicular cancer. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2019;58(3):357–360. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2019-0319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cao ZT, Rej R. Are laboratories reporting serum quantitative hCG results correctly? Clin Chem. 2008;54(4):761–764. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.098822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The need to harmonize clinical laboratory test results. A white paper of American Association for clinical chemistry. 2015.