Abstract

Monoamine oxidase B and Adenosine A2A receptors are used as key targets for Parkinson’s disease. Recently, hMAO-B and hA2AR Dual-targets inhibitory potential of a novel series of Phenylxanthine derivatives has been established in experimental findings. Hence, the current study examines the interactions between 38 compounds of this series with hMAO-B and hA2AR targets using different molecular modeling techniques to investigate the binding mode and stability of the formed complexes. A molecular docking study revealed that the compounds L24 ((E)-3-(3-Chlorophenyl)-N-(4-(1,3-dimethyl-2,6-dioxo-2,3,6,7-tetrahydro-1H-purin-8-yl) phenyl) acrylamide and L32 ((E)-3-(3-Chlorophenyl)-N-(3-(1,3-dimethyl-2,6-dioxo-2,3,6,7-tetrahydro-1H-purin-8-yl)phenyl)acrylamide) had a high affinity (S-score: −10.160 and −7.344 kcal/mol) with the pocket of hMAO-B and hA2AR targets respectively, and the stability of the studied complexes was confirmed during MD simulations. Also, the MEP maps of compounds 24 and 32 were used to identify the nucleophilic and electrophilic attack regions. Moreover, the bioisosteric replacement approach was successfully applied to design two new analogs of each compound with similar biological activities and low energy scores. Furthermore, ADME-T and Drug-likeness results revealed the promising pharmacokinetic properties and oral bioavailability of these compounds. Thus, compounds L24, L32, and their analogs can undergo further analysis and optimization in order to design new lead compounds with higher efficacy toward Parkinson’s disease.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40203-023-00139-3.

Keywords: Phenylxanthine derivatives, Parkinson’s disease, Molecular docking/dynamics, MEP maps, Bioisosteric replacement, ADME-T

Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases (NDs) represent a major health problem in the world. Recently, the prevalence of these diseases has increased significantly in the aging population, especially in developed countries (Abdullah et al. 2015). Many studies refer those NDs to a group of aging-related neurodegenerative disorders of the central nervous system (CNS) that lead to a progressive degeneration and loss of neuronal structures by various molecular mechanisms and display different clinical manifestations (Tzvetkov and Antonov 2017; Meredith et al. 2009; Belaidi and Bush 2016). Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), Huntington’s disease (HD), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) are the most common neurodegenerative diseases, each with different clinical presentations affecting various neuronal populations and brain regions (Stephenson et al. 2018). On the other hand, Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD) rank first compared to other NDs by various experimental and theoretical studies devoted to these two diseases (Dunkel et al. 2012; Jankovic and Poewe 2012). Moreover, recent researches showed that the interaction of molecules with a single known biological target is insufficient to inhibit, retard, halt or reverse NDs (Kakkar and Dahiya 2015; Pisani et al. 2011; Freitas and Fox 2016). Therefore, new alternative approaches have recently gained considerable attention to develop multi-target ligands (MTDL), and suggest molecules that interact with two biological targets in order to increase therapeutic efficacy (Załuski et al. 2019). In this context, we found that recently published papers (Simeonova et al. 2021; Wenzel and Klegeris 2018; Wu et al. 2017; Yang et al. 2020; Tóth et al. 2019) were based on MTDLs to design a molecule to treat NDs such as: Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD). In PD and AD diseases, dual-target directed therapeutics are expected to be advantageous and very efficient over single-target treatments (Brunschweiger et al. 2014; Koch et al. 2013). Monoamine oxidase B and Adenosine A2A receptors are used as key targets for the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders in the case of PD (Petzer et al. 2009). However, the current therapy is based mainly on dopamine replacement strategies with l-DOPA and dopamine agonist drugs as the most beneficial agents (Olanow et al. 2009) through monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibition. Sometimes, we note that these drugs are not effective and we need to replace dopamine with the recently explored non-dopaminergic approach, adenosine receptor blockade (Schwarzschild et al. 2006; Walt et al. 2015). On the other side, a synergistic effect may appear in the treatment of PD with dual-target-directed compounds that antagonize adenosine receptors (i.e. facilitate dopamine release and signaling) and inhibit MAO-B (i.e. reduce the central catabolism of dopamine) (Anighoro et al. 2014; Cavalli et al. 2008). Therefore, these compounds may have an enhanced and very potent therapeutic value in the treatment of PD.

The previous studies (Song et al. 2012; Hu et al. 2012) have shown that the structure based on xanthines derivatives and non-xanthine derivatives are potent inhibitors of monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) (Riederer et al. 2004; Youdi et al. 2006), however, A2AAR target has also been reported (Stosel et al. 2013; Walt et al. 2015; Rivara et al. 2013).

We found that some selective MAO-B inhibitors such as Rasagiline, Selegiline and Safinamide are used as PD therapeutics to increase the dopamine concentration in the brain (Finberg 2014; Talati et al. 2009; Carradori and Petzer 2014). Moreover, various studies have shown that the group of Methylxanthines such as Caffeine and Theophylline are unselective AR antagonists. Also, other researchers have reported that some Xanthine derivatives are a potent and selective A2AAR antagonist (Bonaventura et al. 2014), among them: Istradefylline that has been approved for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease (Dungo and Deeks 2013), while the 8-chlorostyrylcaffeine (CSC) is one of the first antagonists of A2AAR with supplementary MAO-B inhibitory activity (Rivara et al. 2013).

In this research, we try to elucidate how a new series of phenylxanthine (PX) derivatives synthesized by Wang (2017) interact with two targets: A2AAR and MAO-B involved in Parkinson’s disease.

For that purpose, different computational approaches such as molecular docking, MD simulation, molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) maps, bioisosteric replacement approach, and ADMET prediction were carried out to explore the binding of these derivatives with hMAO-B and hA2AAR targets. To validate our results, we conducted a comparative study between the previously mentioned clinical drugs for both targets: MOA-B and A2AAR, with the best compounds obtained through these approaches depending on the score value and interactions.

Materials and methods

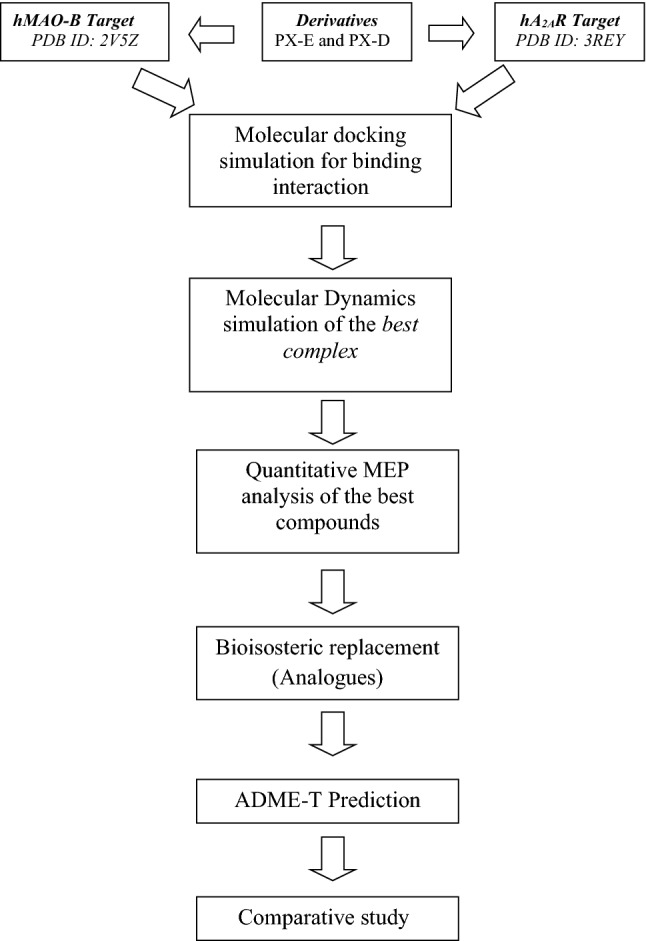

In the following flowchart, we demonstrated a general protocol in which we presented all the steps of the calculation as well as the methods used in our study (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

General protocol of calculation steps, as well as the methods used in the study

Targets and compounds preparations

Targets retrieval

Both crystallographic structures of human MAO-B in complex with Safinamide (SAF) (PDB code: 2V5Z; Resolution = 1.6 Å) (Binda et al. 2002) and human A2AAR in complex with Xanthine amine congener (XAC) (PDB code: 3REY; Resolution = 3.31 Å) (Doré et al. 2011) were retrieved from the (RCSB) Protein Data Bank (PDB; http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/home/home.do).

Preparation of ligands

The geometry optimization and frequency calculation of Phenylxanthine (PX) Derivatives (Wang et al. 2017) (Table 1) (with no imaginary frequencies) were performed using Gaussian 09 program package (Frisch et al. 2009). The Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations were performed using the B3LYP functional (Raghavachari 2000; Bartolotti and Flurchick 1996; Lee et al. 1988) and 6-31++ G(d, p) basis set for all atoms. In addition, the database was created by converting the structures of the studied compounds into “*. mdb” format to use as input in the Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) version 2014.09 (Chemical Computing Group Inc., Montreal, QC, Canada) (Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) 2014) that performs the molecular docking/dynamics simulations.

Table 1.

Biological data and structure–activity relationship (SAR) of A2AAR affinities (Ki) and MAO-B inhibitory potencies (Ki) for the tested compounds (Wang et al. 2017)

| Compounds | L1-38 | –HNCO | R1 | R2 | R3 | Ki hA2AR (µM) | Ki hMAO-B (µM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Istradefylline | 0.05 ± 0.01 | > 10 | |||||

| PX-D-P1 | L1 | para- | H | H | H | 2.31 ± 0.31 | 1.32 ± 0.11 |

| PX-D-P2 | L2 | para- | H | H | CH3 | 2.87 ± 0.21 | 2.06 ± 0.25 |

| PX-D-P3 | L3 | para- | H | H | OCH3 | 2.67 ± 0.14 | 2.94 ± 0.31 |

| PX-D-P4 | L4 | para- | H | Cl | H | 1.52 ± 0.16 | 0.25 ± 0.05 |

| PX-D-P5 | L5 | para- | H | OCH3 | OCH3 | 4.27 ± 0.51 | 1.92 ± 0.25 |

| PX-D-P6 | L6 | para- | CH3 | H | H | 0.33 ± 0.09 | 0.29 ± 0.03 |

| PX-D-P7 | L7 | para- | CH3 | H | CH3 | 0.39 ± 0.06 | 1.21 ± 0.15 |

| PX-D-P8 | L8 | para- | CH3 | H | OCH3 | 1.19 ± 0.12 | 0.47 ± 0.12 |

| PX-D-P9 | L9 | para- | CH3 | Cl | H | 0.27 ± 0.08 | 1.51 ± 0.19 |

| PX-D-P10 | L10 | para- | CH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | 1.34 ± 0.16 | 2.97 ± 0.37 |

| PX-D-M1 | L11 | meta- | H | H | H | 2.91 ± 0.21 | 3.11 ± 0.42 |

| PX-D-M2 | L12 | meta- | H | H | CH3 | 4.51 ± 0.57 | 2.17 ± 0.29 |

| PX-D-M3 | L13 | meta- | H | H | OCH3 | 3.77 ± 0.55 | 2.57 ± 0.37 |

| PX-D-M4 | L14 | meta- | H | Cl | H | 3.61 ± 0.41 | 1.27 ± 0.18 |

| PX-D-M5 | L15 | meta- | H | OCH3 | OCH3 | 4.99 ± 0.75 | 2.36 ± 0.31 |

| PX-D-M6 | L16 | meta- | CH3 | H | H | 2.03 ± 0.25 | 2.26 ± 0.29 |

| PX-D-M7 | L17 | meta- | CH3 | H | CH3 | 2.78 ± 0.33 | 2.57 ± 0.31 |

| PX-D-M8 | L18 | meta- | CH3 | H | OCH3 | 3.05 ± 0.36 | 2.86 ± 0.21 |

| PX-D-M9 | L19 | meta- | CH3 | Cl | H | 2.44 ± 0.21 | 0.76 ± 0.11 |

| PX-D-M10 | L20 | meta- | CH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | 3.59 ± 0.36 | 2.54 ± 0.31 |

| PX-E-P1 | L21 | para- | H | H | H | 4.97 ± 0.59 | 8.11 ± 1.03 |

| PX-E-P2 | L22 | para- | H | H | F | 3.41 ± 0.47 | 9.36 ± 1.21 |

| PX-E-P3 | L23 | para- | H | CF3 | H | 5.18 ± 0.67 | 4.22 ± 0.55 |

| PX-E-P4 | L24 | para- | H | Cl | H | 6.43 ± 0.98 | 1.75 ± 0.15 |

| PX-E-P5 | L25 | para- | CH3 | H | H | 1.46 ± 0.17 | > 10 |

| PX-E-P6 | L26 | para- | CH3 | H | F | 0.79 ± 0.11 | 5.04 ± 0.53 |

| PX-E-P7 | L27 | para- | CH3 | CF3 | H | 1.98 ± 0.15 | > 10 |

| PX-E-P8 | L28 | para- | CH3 | Cl | H | 0.85 ± 0.11 | 0.63 ± 0.11 |

| PX-E-M1 | L29 | meta- | H | H | H | 9.65 ± 0.98 | 3.42 ± 0.32 |

| PX-E-M2 | L30 | meta- | H | H | F | 7.23 ± 0.86 | 2.48 ± 0.23 |

| PX-E-M3 | L31 | meta- | H | CF3 | H | 7.44 ± 0.91 | 2.63 ± 0.31 |

| PX-E-M4 | L32 | meta- | H | Cl | H | 9.58 ± 1.13 | > 10 |

| PX-E-M5 | L33 | meta- | H | OCH3 | OCH3 | > 10 | 2.11 ± 0.19 |

| PX-E-M6 | L34 | meta- | CH3 | H | H | 5.25 ± 0.65 | 3.72 ± 0.52 |

| PX-E-M7 | L35 | meta- | CH3 | H | F | 7.74 ± 0.92 | 2.58 ± 0.37 |

| PX-E-M8 | L36 | meta- | CH3 | CF3 | H | 7.1 ± 0. 84 | 4.76 ± 0.68 |

| PX-E-M9 | L37 | meta- | CH3 | Cl | H | 9.18 ± 1.23 | 2.93 ± 0.41 |

| PX-E-M10 | L38 | meta- | CH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | 6.24 ± 0.77 | 2.55 ± 0.24 |

Computational methods

Molecular docking protocol and validation

Before running molecular docking calculations using the Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) version 2014.09 (Chemical Computing Group Inc., Montreal, QC, Canada) (Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) 2014), all crystallographic structures (X-ray) of the selected targets were simplified by removing water molecules, ions, cofactors and co-crystal ligands from their PDB structures. Also, we followed the same protocol of Molecular docking simulation used in our previous studies (Daoud et al. 2018; Chenafa et al. 2021). The following default parameters were used: Placement: Triangle Matcher; Rescoring 1: London dG. The London dG scoring function was employed to estimate the lowest score energy of the complex for the best pose of the tested compounds.

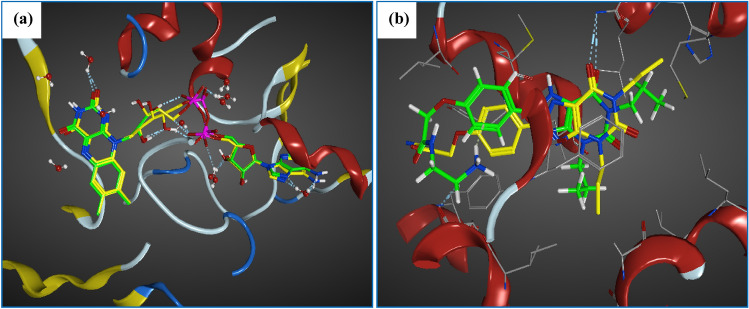

In order to validate the docking method, both native ligands: SAF and XAC were re-docked (Fig. 1) into their targets hMAO-B (PDB ID: 2V5Z) and hA2AAR (PDB ID: 3REY), respectively using MOE software (Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) 2014). We found that the root mean square deviation (RMSD) value is between 1 and 2 Å (Hevener et al. 2009; Bajda et al. 2013) which justifies the accuracy of this method. Finally, both selected targets (PDB ID: 2V5Z and PDB ID: 3REY) were used to investigate the possible bonding of the tested compounds with the pocket of hMAO-B and hA2AAR targets.

Fig. 1.

Validation of molecular docking protocol by re-docking; a SAF into the MOA-B, b XAC into the hA2AAR

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation

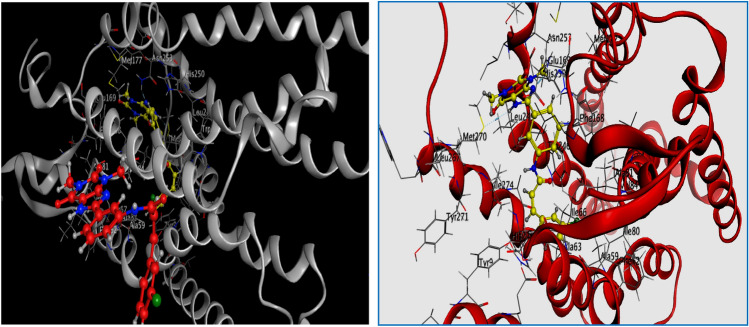

Potential hits with high negative score energy and at least one stable interaction against hMAO-B and hA2AR targets were subjected to Molecular dynamics simulations. MD simulations were performed by NAMD algorithm for 100 ns achieved for both complex (2V5Z—compound 24) and (3REY—compound 32) with the pocket of hMAO-B and hA2AAR targets, respectively were carried out through MOE software (Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) 2014). The Langevin equation (Toda et al. 1991) was used in NAMD to generate the Boltzmann distribution (canonical, isobar-isotherm for ensemble and simulations. The Brunger–Brooks–Karplus (BBK) method was used to integrate the Langevin equation (Brünger et al. 1984). The equations of motion are described by Fokker–Planck (Wang and Skeel 2003). Analysis of simulation results for complex-L24 and complex-L32 against hMAO-B and hA2AR targets, respectively are listed in (Figs. 4 and 5). Moreover, the best conformation obtained in the MD simulation of two complexes was analyzed by iMODS Server (López-Blanco et al. 2011, 2014; Kovacs et al. 2004) to investigate the eigenvalues, variance, deformability, co-variance map, and elastic network. In addition, MOE software has proven its performance in several recent studies (Mesli et al. 2019; Stitou et al. 2021; Belkadi et al. 2021; Toumi et al. 2021) and has been invoked.

Fig. 4.

The compound 24; docked (pink) well into the binding site of hMAO-B and has the highest dock score; there is also a clear difference between the final ligand pose and the docking pose (green) after a molecular dynamics (MD) (pink) simulation in NVT

Fig. 5.

The compound 32; docked (yellow) well into the binding site of hA2AR and has the highest dock score; there is also a clear difference between the final ligand pose and the docking pose (red) after a molecular dynamics (MD) (yellow) simulation in NVT

Molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) and bioisosteric replacement

The quantitative MEP analysis was performed using the multifunctional wave function analyzer code Multiwfn 3.8, (Lu and Chen 2012) in combination with the Cubegen utility of Gaussian software. The ESP-mapped molecular van der Waals surface was rendered using the Visual Molecular Dynamics (VMD) software (Humphrey et al. 1996) based on the outputs of Multiwfn. Furthermore, some statistical descriptors defined by Murray et al. (1994), were investigated to draw quantitative interpretations around the van der Waals molecular surface. These descriptors concern the following statistical quantities: total variance (TV), positive variance (PV), negative variance (NV), positive surface area (PS), and negative surface area (NS).

In addition, the bioisosteric replacement for the rational modification of the best compounds obtained after molecular docking/dynamics simulations was conducted to design new analogs with similar biological activity and additional improved characteristics. For this purpose, we used the online web server Molopt (Shan and Ji 2020) that replaces molecular substructures by chemical groups with similar biological properties.

ADME-T prediction and chemical properties

SwissADME server (http://www.swissadme.ch/) (Daina et al. 2017) was used to calculate the different physicochemical properties such as TPSA, nROT, MW, LogP, Number of hydrogen bond acceptors (nHA), and Number of hydrogen bond donors (nHD) in order to verify the different rules namely: Lipinski, Veber, and Egan. In ADME-T part, we used the pkCSM server (http://biosig.unimelb.edu.au/pkcsm/prediction) (Pires et al. 2015) to predict: the absorption [Caco-2: colon adenocarcinoma, HIA: human intestinal absorption, skin permeability (log Kp)], distribution [CNS: central nervous system permeability, BBB: blood–brain barrier permeability, VDss (human) (the volume of distribution, metabolism (CYP1A2 inhibitor, CYP2C19 inhibitor, CYP2D6 inhibitor, CYP2D substrate, CYP3A4 substrate)], excretion (renal OCT2 substrate: organic cation transporter 2: total clearance).

In addition, using the Protox II server (Banerjee et al. 2018a, 2018b; Drwal et al. 2014), the toxicological pathways, including organ toxicity, toxicity, and stress response pathways were tested successively to determine the toxicity of the selected compounds L24, L32, and their analogs, as well as Rasagiline (standard drug) for hMAO-B and Istradefylline (standard drug) for hA2AR.

Results and discussion

Score energy and pose analysis

We can reveal the potency of the studied compounds by measuring their score energy and analyzing the non-covalent interactions between the compounds and the binding site pockets of selected targets. After docking all compounds into active site residues of both targets (PDB ID: 2V5Z and PDB ID: 3REY), the docking results were analyzed and discussed based on various parameters such as affinity (S-score), interactions (types and distances). First, the stability of the target-compound complex depends on the high binding affinity between these two entities, which is justified by the negative energy score of the formed complex. Second, non-covalent bonds (hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions…) ensure the formation of complexes (target-compound), and they can be classified in the following ranges.

According to the literature, H-bond distances belonging to the interval between 2.5 and 3.1 Å are considered strong interactions, and those ranging between 3.1 and 3.55 Å are assumed to be weak (Imberty et al. 1991; Jeffrey and Jeffrey 1997; Wade and Goodford 1989). Hydrophobic interactions: according to Janiak (2000) who suggests that the optimal range of hydrophobic interactions is between: 3.3–3.8 Å. While other researchers have suggested a relatively higher range (Burley and Petsko 1985; Piovesan et al. 2016).

Poses and bonding interaction of compounds with the active site of the hMAO-B target (PDB ID: 2V5Z)

The docking results of the best Phenylexanthine (PX) derivatives with the hMAO-B target pocket are listed in Table 2 (for other compounds see Table S1 in the S.I section).

Table 2.

S-score (energy), RMSD, and interactions between the best compounds and the active site residues of hMAO-B target

| hMAO-B (PDB ID: 2V5Z) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compounds | S-score (kcal/mol) | RMSD | Bonds between atoms of compounds and the active site residues of hMAO-B | ||||

| Atom of compound | Involved receptor atoms | Involved receptor residues | Type of interaction bond | Distance (Å) | |||

| Native ligand (SAF) | − 7.604 | 2.760 | 6-ring | CA | ILE199(A) | pi–H | 4.79 |

| 6-ring | 6-ring | TYR398(A) | pi–H | 3.91 | |||

| L9 | − 9.218 | 3.159 | O25 | SG | CYS397(A) | H-donor | 3.17 |

| C27 | SG | CYS397(A) | H-donor | 4.22 | |||

| 6-ring | CB | TYR398(A) | pi–H | 3.92 | |||

| L10 | − 9.882 | 3.187 | O25 | SG | CYS397(A) | H-donor | 3.34 |

| C27 | SG | CYS397(A) | H-donor | 4.22 | |||

| 6-ring | CA | ILE199(A) | pi–H | 3.79 | |||

| 6-ring | CB | TYR398(A) | pi–H | 3.90 | |||

| 5-ring | 6-ring | TYR398(A) | pi–pi | 3.85 | |||

| L24 | − 10.160 | 2.467 | Cl 48 | O | LEU164(A) | H-donor | 3.60 |

| 5-ring | 6-ring | TYR398(A) | pi–pi | 3.58 | |||

| 6-ring | 6-ring | TYR398(A) | pi–pi | 3.90 | |||

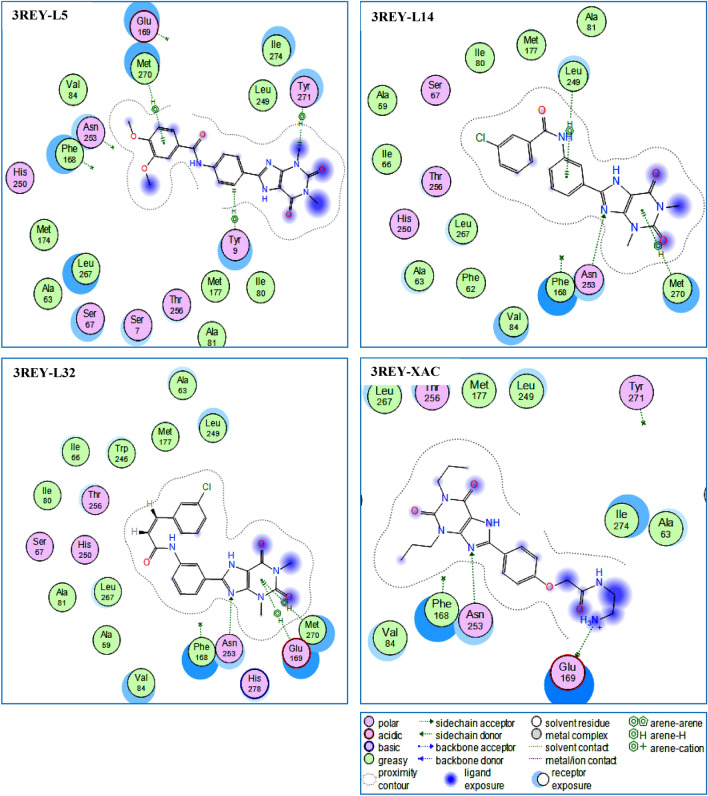

Score energies and the amino acid interactions of the three best compounds with the MAO-B target are shown in Table 2 and Table S1 in S.I section. Almost all of them have hydrogen and/or hydrophobic bonding interactions with common active site residues from the pocket: Tyr60, GLY58, Cys397, Ile199, Gln206, Tyr326, and Tyr398 (see Figure S1 in S.I section).

According to the docking and score energy results, compounds L13, L24 and L33 showed the best binding affinity (Docking score = − 10.086, − 10.160, and − 10.186 kcal/mol, respectively.) with the pocket of hMAO-B target. In addition, we can note clearly that compound L24 establishes more interactions than both compounds L13 and L33 (see Table 2, Table S1 and Figure S1 in S.I section). On the other side, as presented in Table 2, compounds L9 and L10 interacted with the active site residues of the hMAO-B target and gave high negative energy score by displaying several types of interactions.

The compound L33 was involved in a single hydrophobic interaction (pi–H) with the binding site of hMAO-B. Moreover, no interactions appeared between compound L13 and the binding pocket of the hMAO-B (see Table S1 and Figure S1 in S.I section).

The compound L24 shows one weak (Imberty et al. 1991; Jeffrey and Jeffrey 1997; Wade and Goodford 1989) hydrogen bond (H-donor) established between the chlorine atom of this compound and the active site residue LEU164(A) of hMAO-B at a distance of 3.60 Å. Also, two hydrophobic interactions are observed for this compound with the same residue: TYR398(A) (see Table 2).

Although the complex formed by compound L10 did not show the highest negative energy score compared to other derivatives, however, it established five binding interactions with the active site residues of the hMAO-B target. Therefore, this compound was involved in the formation of two weak (Imberty et al. 1991; Jeffrey and Jeffrey 1997; Wade and Goodford 1989) hydrogen bonds (H-donor), the first one formed between the O25 atom of the compound and SG of the CYS397(A) at a distance of 3.34 Å, and the second formed between the atom O27 and the same residue at a distance of 4.22 Å. Three other hydrophobic interactions were found, two pi–H interactions established between the 6-ring of the compound and both residues: ILE199(A)/TYR398(A), as well as a pi–pi interaction formed between the 5-ring of this compound and the TYR398(A) (Table 2).

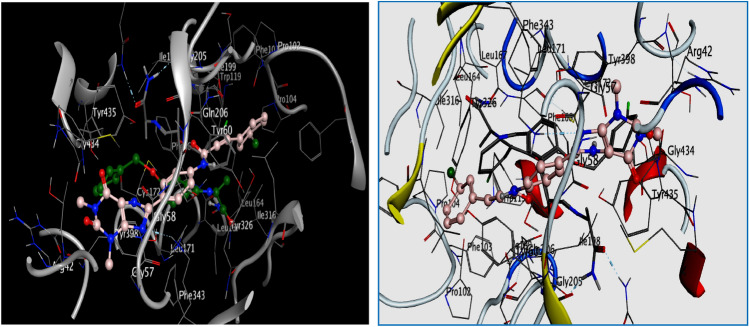

Likewise, the interaction of L9 with the pocket of the hMAO-B target showed a low energy score (docking score = − 9.218 kcal/mol) which was confirmed by the formation of two hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interaction with the residue of the active site of hMAO-B target. Two weak (Imberty et al. 1991; Jeffrey and Jeffrey 1997; Wade and Goodford 1989) hydrogen bonds (3.17 and 4.22 Å respectively) were formed between the O25 and O27 atom of the compound L9 and SG of the same residue CYS397(A), another hydrophobic interaction pi–H formed between 6-ring of this compound and CB of TYR398(A) (Table 2, Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

2D Visualization of the binding modes of the best compounds L9, L10, L24, and SAF inside the active site of hMAO-B target

Another point, the literature (Rivara et al. 2013) indicates that the position of SAF is quite special such that the halogenated aromatic ring is in the inlet cavity, while the polar part is placed in an aromatic cage and directed toward the cofactor flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD). In addition, some previous studies (Binda et al. 2002, 2007; Colibus et al. 2005) indicated that the pocket cavity of MAO-B contains two parts that can be identified as the entrance cavity and the substrate cavity in front of the FAD (Table 2).

As can be seen in Fig. 2, the docked compound L10 in the binding pocket of MAO-B is oriented in a similar manner as the native co-crystallized ligand SAF (Binda et al. 2002).

Furthermore, several studies (Azam et al. 2019; Mellado et al. 2019; Chaurasiya et al. 2019; Hong and Li 2019; Dasgupta et al. 2021) have reported that TYR398(A) and ILE199(A) have an important role in the binding site of the hMAO-B target observed through their hydrophilic interactions with the native ligand SAF. Similarly, these residues also serve as a contributor to the hydrophilic interactions of the docked compound 10 (Table 2). Also, as mentioned earlier, this compound established two weak hydrogen bonds with the same residue CYS397(A) at distances of 3.34 and 4.22 Å, respectively (Table 2, Fig. 2).

In addition, compounds L9 and L24 established hydrophilic interactions with TYR398(A) and other residues like CYS397(A) and LEU164(A).

Turning now to the experimental results (Ki) (Wang et al. 2017) and in comparison with our results, a good correlation was observed between the in vitro/and in silico results, implying a strong relationship between the affinity (between hMAO-B target and these compounds) and the activity of compounds on that target. Overall, it can be stated that all compounds fit well within the hMAO-B binding pocket that forms the expected receptor–ligand interactions.

Poses and bonding interaction of compounds with the active site of hA2AAR target (PDB ID: 3REY)

The docking results of the best Phenylexanthine (PX) derivatives with the hA2AR target pocket are shown in Table 3 (for other compounds see Table S2 in the S.I section).

Table 3.

S-score (energy), RMSD, and interactions between the best compounds and the active site residues of the hA2AR target

| hA2AR (PDB ID: 3REY) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compounds | Energy S-score (kcal/mol) | RMSD (Å) | Bonds between atoms of compounds and the active site residues of hA2AR | ||||

| Atom of compound | Involved receptor atoms | Involved receptor residues | Type of interaction bond | Distance (Å) | |||

| Native ligand (XAC) | − 7.618 | 6.813 | N6 | OE2 | GLU169(A) | H-donor | 2.80 |

| N3 | ND2 | ASN253(A) | H-acceptor | 3.32 | |||

| L5 | − 6.926 | 2.019 | C11 | 6-ring | TYR9(A) | H–pi | 4.21 |

| C28 | 6-ring | TYR271(A) | H–pi | 4.74 | |||

| 6-ring | CE | MET270(A) | pi–H | 3.86 | |||

| L14 | − 7.281 | 2.140 | N 8 | ND2 | ASN253(A) | H-acceptor | 2.94 |

| 6-ring | CD2 | LEU249(A) | pi–H | 4.44 | |||

| 6-ring | CE | MET270(A) | pi–H | 3.67 | |||

| L32 | − 7.344 | 1.547 | N 8 | ND2 | ASN253(A) | H-acceptor | 2.85 |

| 6-ring | CB | GLU169(A) | pi–H | 4.54 | |||

| 6-ring | CE | MET270(A) | pi–H | 3.73 | |||

As presented in Table 3, we found that three compounds L5, L14, and L32 (Fig. 3) were predicted to have the best affinity with hA2AAR, forming the most stable complexes with the lowest energy score −6.926, −7.281, and −7.344 kcal/mol respectively, which interact with several active site residues of hA2AAR target.

Fig. 3.

2D Visualization of the binding modes of the best compounds L5, L14, L32, and XAC inside the active site of hA2AAR target

The compounds L14 and L32 were deeply buried in the hA2AAR binding site and formed strong (Imberty et al. 1991; Jeffrey and Jeffrey 1997; Wade and Goodford 1989) hydrogen acceptor bonds with ASN253(A) at: 2.94 and 2.85 Å, respectively (Table 3, Fig. 3). On the other hand, a considerable amount of literature (Szabo et al. 2015; Załuski et al. 2019; Jaiteh et al. 2018; Zhukov et al. 2011) has been published confirming that both: ASN253(A) and MET270(A) are the key amino acids in the binding site of hA2AAR target.

Noteworthy, the score value of compound L32 is very close to that of native ligand XAC (−7.344 kcal/mol) vs. −7.618 kcal/mol (Table 3). In addition, this compound gave a high negative score value compared to the four standard drugs named: Caffeine, 8-chlorostyrylcaffeine, Istradefylline, and Theophylline (−7.344 kcal/mol vs. −5.256, −6.416, −7.343, and −4.723 kcal/mol) (Table 3).

From the co-crystallized ligand XAC, two hydrogen bonds (H-acceptor and H-donor) are formed with the active site of hA2AAR (Table 3, Fig. 3). It follows that XAC is strongly bound to the pocket, explaining its complete inhibition of this enzyme.

Compound L32 shares the same binding region with a similar pose to the native ligand XAC (Fig. 3). However, this compound forms one H-bond and two hydrophobic interactions.

The strong (Imberty et al. 1991; Jeffrey and Jeffrey 1997; Wade and Goodford 1989) hydrogen acceptor bond appears between the nitrogen atom (N8) of the compound and the key residue: ASN253(A) at a distance of 2.85 Å (Fig. 3). Moreover, two pi–H interactions are observed, the first one is established between 6-ring of the compound and GLU169(A), the second is formed between 6-ring of the compound and MET270(A) (Fig. 3).

Likewise, we noted that two compounds L5 and L14 were involved in forming more interactions (three interactions) with the target pocket of hA2AAR compared to the other studied compounds (Table 3, Fig. 3). Additionally, the compound L14 gave a score value (−7.281 kcal/mol) that is very close to the native ligand XAC (−7.618 kcal/mol) while establishing three interactions with the active site residues of hA2AAR. The strong (Imberty et al. 1991; Jeffrey and Jeffrey 1997; Wade and Goodford 1989) hydrogen acceptor bond appears between the nitrogen atom (N8) of this compound and the key residue: ASN253(A) at a distance of 2.94 Å (Table 3). Also, two pi–H interactions were observed, the first one is established between 6-ring of the compound and LUE249(A), the second is formed between 6-ring of the compound and MET270(A) (Fig. 3).

The complex formed with compound L5 has the highest S-score energy (−6.926 kcal/mol, Table 3) compared to the native compound (XAC. Compound L5 exhibits two H–pi interactions: the first formed between the carbon atom (C11) and the 6-ring of TYR9(A); the second was established between the carbon atom (C28) and the 6-ring of TYR271(A). Moreover, the 6-ring of the compound L5 displays one pi–H interaction with MET270(A) (Table 3, Fig. 3). Furthermore, it is worth noting that some compounds such as L15, L28, L31, L33, and L35 have high negative energy scores compared to the native compound (XAC) and other compounds, but unfortunately, these compounds could not establish any interaction with the active site residues of hA2AAR target (Table S2 and Figure S2 in the S.I section).

The comparison between the experimental (Wang et al. 2017) and in silico results reveals a strong correlation between them, which can be explained by the existence of a relationship between the energy score (affinity) and the Ki (activity). It is therefore, realistic to compare a measured activity with the energy score value.

Molecular dynamics simulation

Thermodynamic properties

The evolution of the thermodynamic properties of the best results (L24 and L32) was studied in the NVT ensemble. Also, the energy minimization was carried out on the best complexes obtained after docking at 600 ps, then followed by a simulation up to (MD production cycles) 100 ns in three stages under constraints (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Thermodynamic properties calculated in reels units

| Stage | Method | H | U | EKT | P | V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SP1 | L24NVT | 25.236 ± 0.001 | −1256.33 ± 0.021 | 4523.22 ± 0.030 | −42.23 ± 0.050 | 44,205.320 |

| L32NVT | 33.215 ± 0.002 | −2550.22 ± 0.031 | 5123.00 ± 0.001 | −44.23 ± 0.020 | 54,510.230 | |

| L24NVT | 12.32 ± 0.004 | −2200.00 ± 0.201 | 5620.36 ± 0.050 | 55.21 ± 0.010 | 46,520.231 | |

| L32NVT | 27.256 ± 0.001 | −3230.22 ± 0.101 | 623.00 ± 0.040 | −46.23 ± 0.0240 | 46,402.230 | |

| L24NVT | 14.214 ± 0.005 | −4052.00 ± 0.051 | 4015.22 ± 0.021 | 70.25 ± 0.120 | 55,402.550 | |

| L32NVT | 42.56 ± 0.004 | −4652.22 ± 0.021 | 4320.22 ± 0.041 | 162.33 ± 0.50 | 54,232.005 | |

| SP2 | L24NVT | 12.50 ± 0.001 | −2401.72 ± 0.041 | 3562.22 ± 0.011 | −220.32 ± 0.060 | 45,602.236 |

| L32NVT | 49.254 ± 0.005 | −3620.20 ± 0.001 | 5523.22 ± 0.020 | −204.01 ± 0.022 | 55,802.506 | |

| L24NVT | 52.23 ± 0.044 | −3120.55 ± 0.021 | 4560.23 ± 0.016 | 155.23 ± 0.050 | 57,801.230 | |

| L32NVT | 40.00 ± 0.045 | −4201.23 ± 0.051 | 5236.22 ± 0.001 | −48.50 ± 0.055 | 49,502.236 | |

| L24NVT | 29.203 ± 0.042 | −3562.55 ± 0.041 | 4156.32. ± 0.025 | −120.30 ± 0.062 | 48,532.0452 | |

| L32NVT | 52.036 ± 0.052 | −4482.96 ± 0.001 | 5236.22 ± 0.061 | −55.63 ± 0.040 | 47,625.520 | |

| SP3 | L24NVT | 55.26 ± 0.052 | −4540.56 ± 0.051 | 4524.55 ± 0.042 | −60.23 ± 0.004 | 57,052.236 |

| L32NVT | 21.22 ± 0.052 | −5220.36 ± 0.010 | 5526.23 ± 0.101 | −46.55 ± 0.040 | 46,500.210 | |

| L24NVT | 54.152 ± 0.055 | −3623.55 ± 0.001 | 5580.35 ± 0.100 | −47.55 ± 0.0050 | 46,235.850 | |

| L32NVT | 45.236 ± 0.042 | −4256.23 ± 0.001 | 6963.66 ± 0.200 | 123.22 ± 0.0010 | 55,520.369 | |

| L24NVT | 49.303 ± 0.040 | −4640.25 ± 0.001 | 4940.23 ± 0.300 | −60.23 ± 0.060 | 54,723.230 | |

| L32NVT | 57.520 ± 0.053 | −5265.25 ± 0.001 | 56,438.90 ± 0.070 | 46.25 ± 0.050 | 4545.236 |

Pressure P = P*ε/σ−3. Energy of configuration U = U* Nε. Translation kinetic energy EKT = EKT* Nε and enthalpy H = H* Nε

The results summarized in Table 4 revealed that the energy of complex hA2AR-Compound 32 is low compared to complex hMAO-B-Compound 24 in the NVT units, and the pressure fluctuation of the complex receiver is significant. Therefore, compounds 32 and 24 were predicted to be the most interactive systems for both targets hA2AR and MAO-B, respectively.

Finally, these results are in full agreement with molecular docking results (see Figs. 4 and 5). In addition, we can clearly see that complex hA2AR-Compound 32 is more stable compared to complex hMAO-B-Compound 24, which means that the latter is in Para position, which is less stable than Meta position.

Structural dynamics properties

The evolution of structural dynamics was studied for both best complexes obtained after molecular docking hMAO-B-L24 and hA2AR-L32.

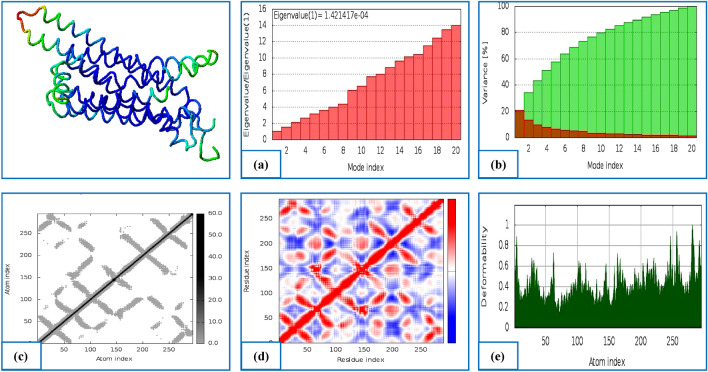

The normal mode analysis (NMA) of both complexes: hMAO-B-Ligand 24 and hA2AR-Ligand 32 were illustrated in Figs. 6a–e and 7a–e. From the molecular dynamics study, it was clear that the prepared two complexes had a high eigenvalue of 8.551418e−05 and 1.421417e−04, respectively as illustrated in Figs. 6a, 7a.

Fig. 6.

Results of molecular dynamics simulation of hMAO-B-L24 docked complex. a Eigenvalue, b variance (red color indicates individual variances and green color indicates cumulative variances), c elastic network (darker grey regions indicate stiffer regions) of the complex, d co-variance map (correlated (red), uncorrelated (white) or anti-correlated (blue) motions), e B-Factor mobility

Fig. 7.

Results of molecular dynamics simulation of the hA2AR-L32 docked complex. a eigenvalue, b variance (red color indicates individual variances and green color indicates cumulative variances), c elastic network (darker grey regions indicate stiffer regions) of the complex, d co-variance map (correlated (red), uncorrelated (white) or anti-correlated (blue) motions), e B-Factor mobility

However, the variance map showed a higher degree of cumulative variances than individual variances (Figs. 6b, 7b). The elastic network map and co-variance also produced quite satisfactory results as represented in Figs. 6c, d and 7c, d, respectively. The deformability graphs of the complexes hMAO-B-Ligand 24 and hA2AR-Ligand 32 illustrate the peaks in the graphs that correspond to regions of the protein with deformability (Figs. 6e, 7e).

Finally, the two selected Phenylxanthine (PX) derivatives can be used as potential agents for the treatment of NDs such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Overall, in our study, the compounds: L24 and L32 emerged as the most potent anti-Parkinson disease with significant inhibition of hMAO-B and hA2AR targets, respectively. However, more in vitro and in vivo research should be performed on L24 and L32 in order to confirm the findings of this study.

Quantitative MEP analysis

The electrostatic potential (ESP) is a relevant guide in revealing and predicting non-covalent interactions between the interacting molecules (Murray and Politzer 2011). The sign of ESP at each point on the molecular surface is determined by one of the two dominant charge distributions (electrons and nuclei). ESP-mapped van der Waals surfaces with 0.001 a.u. isosurface of electron density, the surface extrema, and some of the statistically-based molecular descriptors of L24 and L32 are shown in Fig. 8. Orange and cyan tiny spheres correspond to maxima and minima, respectively. The values labeled with an asterisk refer to the global extrema.

Fig. 8.

ESP-mapped van der Waals surfaces (kcal/mol) using a color scale ranging from red (negative ESP) through white (neutral ESP) to blue (positive ESP). The blue regions are prone to nucleophilic attack, and the red regions are sites for electrophilic attack. The grid spacings were set to 0.2 Bohr, and the van der Waals surface denotes the isosurface of ρ = 0.001*e/Bohr3 (a.u). The bold numbers in the bottom right-hand corner are the positive ESP variance (PV), negative ESP variance (NV), positive surface area (A +), and negative surface area (A −) whose units are (Kcal/mol)2, Å2, respectively

The attractive (negative ESP) and repulsive (positive ESP) regions correspond to the red and blue colors, respectively. Positive regions are vulnerable to nucleophilic attack, whereas negative regions preferentially attract electrophilic reagents. The ESP value is close to zero in the regions colored in shades of white, where the molecule is mostly non-polar. As expected, the electron-rich sites are located around the heteroatoms, mainly due to the lone electron pairs and the electronegative effect exerted by these atoms. For L32, the most electron-rich site (global minima) with a value of −37.35 kcal/mol is observed at the oxygen atom (O-37) in the carbonyl group. This molecular site is most reactive towards electrophilic attacks. Besides, the most electron-deficient site (global maxima) with a value of 54.87 kcal/mol is located around H-20 attached to the nitrogen atom. Typically, hard bases preferentially attack this molecular site where the electrostatic potential reaches its maximum positive value. The same nucleophilic and electrophilic sites are located for L24, but with slightly lower magnitudes with values of −35.68 and 54.05 kcal/mol for the global minima and global maxima, respectively. It is worth noting that this difference in the magnitude of the global extrema will certainly influence the reactivity of the two molecules. Compared to L32, the L24 molecule reduces its propensity to undergo an electrostatic electrophilic attack by about 1.67 kcal/mol and its propensity to undergo an electrostatic nucleophilic attack is reduced by about 0.82 kcal/mol.

The total variances (TV = PV + NV, expressed as the sum of positive and negative contributions) obtained for L24 and L32 are 203.50 and 194.26 (kcal/mol)2, respectively. This result implies a strong charge density fluctuation for L24 compared to L32. For both molecules, we found NV > PV indicating a strong dispersion of the negative regions compared to the positive ones, this is typical behavior of organic molecules (Murray et al. 2009). Indeed, the contribution of NV is about 60% compared to the total variance. Further, we also found PS > NS, and therefore the positive surface areas cover larger zones (with a contribution of 63% compared to the total surface area). This positive electrostatic potential is primarily generated by the hydrogen atoms, which contribute more to the positive surface.

Bioisosteric analogues

The bioisosteric replacement approach is used to rationally modify both compounds L24 and L32 (which are considered potent inhibitors against hMAO-B and hA2AR targets, respectively) in order to design analogs of these latter with similar biological activity and additional improved characteristics. All results are regrouped in Table 5.

Table 5.

In silico bioisosteric replacement based on similarity comparison method

| Compounds | Structures | Replacable group | Transformation in previous studies | Analogue structure | Smiles | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L24 (para-position) |

|

|

J. Med. Chem., 1992, 35, 177–184 | Analog-1-(L24) |

|

Cn1c(=O)c2[nH]c(–c3ccc(NC(=O)C=Cc4cccc(Cl)c4)cc3)nc2n([N+](=O)[O–])c1=O |

|

Bioorg. Med. Chem., 2008, 16, 10,061–10,074 | Analog-2-(L24) |

|

Cn1c(=O)c2[nH]c(–c3ccc(NC(=O)OCc4cccc(Cl)c4)cc3)nc2n(C)c1=O | ||

| L32 (meta-position) |

|

|

Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett., 2011, 21, 1498–1501 | Analog-1-(L32) |

|

Cn1c(=O)c2[nH]c(–c3cccc(NC(=O)OC=Cc4cccc(Cl)c4)c3)nc2n(C)c1=O |

|

J. Med. Chem., 2008, 51, 6348–6358 | Analog-2-(L32) |

|

Cn1c(=O)c2[nH]c(–c3cccc(NC(=O)NC(=O)c4cccc(Cl)c4)c3)nc2n(C)c1=O | ||

According to the data obtained from the previous Tables 2, 3, 4, it is clear that L24 and L32 are the best compounds among the tested Phenylxanthine (PX) derivatives. Therefore, we considered proposing another molecule using fragments of both compounds that have good affinity against the sites of hMAO-B and hA2AR targets respectively. So the solution is to replace a fragment. These identified bioisosteric fragments will then be studied further to determine if they can be used to enhance the properties of a lead compound.

Evaluation of the ADME-T properties and drug-likeness

ADME-T predictions, physicochemical properties calculations, and drug-likeness evaluation of the best compounds obtained from molecular docking: L9, L10, and L24 with hMAO-B target and the compounds: L5, L14, and L32 with hA2AAR target were performed by using two servers online: SwissADME and pkCSM. The results for compounds L24 and L32 are given in Tables 5 and 6 (The results for compounds: L9, L10, L5, and L14 were grouped in Table S3 and Table S4 in Section S.I).

Table 6.

Physicochemical Properties and Drug Likeliness of the best compounds: L24 and L32

| Compds | Physicochemical properties | Drug likeliness | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPSA (Å2) | n-ROT | MW (g/mol) | MLog P | n-HA | n-HD | Lipinski | Veber | Egan | |

| WLogP | |||||||||

| (0–140) | (0–11) | (100–500) | (0–5) | (0–12) | (0–7) | ||||

| Best compounds of the hMAO-B | |||||||||

| L24 | 97.16 | 5 | 437.88 | 2.82 | 3 | 3 | Accepted | Accepted | Accepted |

| 1.16 | |||||||||

| Best compounds of the hA2AR | |||||||||

| L32 | 101.78 | 5 | 435.86 | 2.69 | 4 | 2 | Accepted | Accepted | Accepted |

| 2.63 | |||||||||

TPSA topological polar surface area; n-ROT number of rotatable; MW molecular weight; Log P logarithm of partition coefficient of compound between n-octanol and water; n-HA number of hydrogen bond acceptors; n-HD number of hydrogen bonds donors

Drug-likeness evaluation

Different parameters of physicochemical properties were calculated in order to verify the drug-likeness rules using the SwissADME server and all results are presented in Table 6.

It is apparent from this table that both compounds: L24 and L32 have a number of hydrogen bond donors < 7 [n-HD: (0–7)] and hydrogen bond acceptors < 12 [n-HA: (0–12)]. Also, the Molecular weights of these compounds belong to the interval: 100–500 g/mol, and the MLogP, WLogP values are < 5. In addition, we note that the nROTB values are < 11, which denotes the flexibility of these compounds. In particular, these results indicate that these compounds satisfy all the criteria of drug-likeness without any violation of Lipinski, Veber, and Egan rules. On the other side, all TPSA values obtained (less than 140 Å) indicate that these compounds have good permeability in the cellular plasma membrane as they can cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB). Obviously, both compounds would not be expected to cause any problems with oral bioavailability and the pharmacokinetic parameters.

ADME properties

The absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion were calculated using the pkCSM server and all results are given in Table 7.

Table 7.

ADME properties (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion) of the compounds: L24 and L32

Caco-2 colon adenocarcinoma; HIA human intestinal absorption; CNS central nervous system permeability; BBB blood–brain barrier permeability; VDss(human) the volume of distribution; Renal OCT2 substrate organic cation transporter 2

Green = good,

Green = good,  Yellow = tolerable,

Yellow = tolerable,  Red = bad

Red = bad

As can be seen from the above table, compounds L24 and L32 have an average Caco-2 permeability (with yellow color). In addition, both tested compounds have higher HIA values than 30%, suggesting that these compounds can be administered orally and are highly absorbed by the gastrointestinal system into the bloodstream of the human body. We also note that these compounds showed average skin permeability because their LogKp values are between −2.5 < LogKp < −3.0 (Table 7).

According to data from this table, we can see that logPS values for compounds L24 and L32 are between: −3 < logPS < −2 (with yellow color), which means that these compounds are able to penetrate the CNS. Additionally, the logBB values of the compounds L24 and L32 are −0.963 and −0.961, respectively (with yellow color) and this indicates that both compounds are moderately distributed in the brain. Also, as Table 7 shows, both compounds give low VDss (LogVDss < −0.15).

Data from this table indicates that compounds L24 and L32 would be inhibitors of CYP1A2 and CYP2C19 isoforms. In addition, both compounds are not CYP2D6 inhibitors and substrates. However, we can also see that these compounds could be CYP2D substrates.

Further analysis of the table showed that compounds L24 and L32 are not likely to be OCT2 substrates. Moreover, we can clearly see that both compounds (with green color) have low clearances (< 5 mL/min/kg) (Table 7).

Prediction toxicity risk

All results of toxicological pathways, including organ toxicity, toxicity, and stress response pathways of the selected compounds L24, L32, their analogs, and Rasagiline for hMAO-B and Istradefylline for hA2AR are listed in Table 8.

Table 8.

Organ toxicity, toxicity, and stress response pathways report of two best compounds (L24 and L32), their analogs, and two best control ligands (Rasagilinen and Istradefylline)

A active; I inactive

According to data from this table, we can note that Rasagiline gave a predicted LD50 value of 250 mg/kg and the predicted Toxicity Class: 3, also, the Istradefylline gave a predicted LD50 of 19 mg/kg and predicted toxicity Class: 2. In addition, both control drugs (Rasagiline and Istradefylline) present the active mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) and Mutagenicity test. Besides, the compounds L24 and L32 appeared inactive for all toxic effects, however, they were active for Hepatotoxicity. Also, we note that analog 1 for L24 is the best compound according to Table 7, which has an average similarity of 42.36% and prediction accuracy of 54.26%. In addition, we can say that analog 2 of L32 was the best compound according to Table 7: average similarity: 58.48% and prediction accuracy: 67.38%.

Finally, as shown in Table 8, the predicted toxicity (Class: 4) for all analogs > L24, L32 and the Rasagiline (Class: 3) > Istradefylline (Class: 2).

Comparative study

In addition, the validation of our results was confirmed by the comparative study of the best compounds L24 and L32 (Phenylxanthine (PX) derivatives and the clinical agents for the treatment of NDs (Rasagiline and Selegiline) for hMAO-B, and (caffeine, 8-chlorostyrylcaffeine, istradefylline, and theophylline) for hA2AR. All the obtained results are mentioned in Table 9.

Table 9.

The energy balance of complex formed with hMAO-B and hA2AR under potent clinical agents for the treatment of NDs and our results

| hMAO-B (PDB ID: 2V5Z) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compounds | Energy S-score (kcal/mol) | RMSD | Bonds between atoms of compounds and the active site residues of hMAO-B | ||||

| Atom of compound | Involved receptor atoms | Involved receptor residues | Type of interaction bond | Distance (Å) | |||

| Test clinic | |||||||

| Rasagiline | − 6.168 | 1.701 | N1 | OE1 | GLN206(A) | H-donor | 2.87 |

| Selegiline | − 5.995 | 1.226 | N1 | OE1 | GLN206(A) | H-donor | 3.05 |

| C12 | 6-ring | TYR326(A) | H–pi | 4.46 | |||

| Our results | |||||||

| L24 | − 10.160 | 2.467 | Cl48 | O | LEU164(A) | H-donor | 3.60 |

| 5-ring | 6-ring | TYR398(A) | pi–pi | 3.58 | |||

| 6-ring | 6-ring | TYR398(A) | pi–pi | 3.90 | |||

| Analogue-1 | − 10.115 | 1.044 | N1 | CB | ILE199(A) | H-donor | 3.33 |

| O17 | SG | CYS397(A) | H-donor | 3.81 | |||

| O28 | CA | TYR435(A) | H-acceptor | 3.50 | |||

| N10 | 6-ring | TYR435(A) | H–pi | 4.60 | |||

| 5-ring | 6-ring | TYR398(A) | pi–pi | 3.58 | |||

| Analogue-2 | − 10.135 | 1.808 | C7 | 6-ring | TYR435(A) | H–pi | 4.62 |

| C7 | 6-ring | TYR398 (A) | H–pi | 4.06 | |||

| 6-ring | CB | ILE199(A) | pi–H | 3.64 | |||

| 6-ring | CB | TYR398 (A) | pi–H | 3.67 | |||

| hA2AR (PDB ID: 3REY) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compounds | S-score (kcal/mol) | RMSD (Å) | Bonds between atoms of compounds and the active site residues of hA2AR | ||||

| Atom of compound | Involved receptor atoms | Involved receptor residues | Type of interaction bond | Distance (Å) | |||

| Test clinic | |||||||

| Caffeine | − 5.256 | 1.043 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 8-chlorostyrylcaffeine | − 6.416 | 1.734 | C14 | 5-ring | HIS278(A) | H–pi | 4.41 |

| Istradefylline | − 7.343 | 0.924 | 6-ring | CE | MET270(A) | pi–H | 3.81 |

| Theophylline | −4.723 | 2.934 | N5 | 6-ring | PHE168(A) | H–pi | 3.94 |

| Our results | |||||||

| L32 | − 7.344 | 1.547 | N 8 | ND2 | ASN253(A) | H-acceptor | 2.85 |

| 6-ring | CB | GLU169(A) | pi–H | 4.54 | |||

| 6-ring | CE | MET270(A) | pi–H | 3.73 | |||

| Analogue-1 | − 7.269 | 1.660 | N8 | ND2 | ASN253(A) | H-acceptor | 3.77 |

| 6-ring | CD2 | LEU267(A) | pi–H | 4.12 | |||

| 5-ring | 6-ring | PHE168(A) | pi–pi | 3.98 | |||

| Analogue-2 | − 7.657 | 2.887 | O27 | ND2 | ASN253(A) | H-acceptor | 2.92 |

| 6-ring | CB | GLU169(A) | pi–H | 4.06 | |||

| 6-ring | CE | MET270(A) | pi–H | 3.89 | |||

It is apparent from this table that the results of our current study (molecular docking/dynamics) with new hMAO-B and hA2AR inhibitors are very encouraging compared with clinical results, confirming that both Phenyl Xanthine (PX) derivatives L24 and L32 were the most effective in inhibiting these enzymes and can be good drug candidates (Table 9).

In addition, it is worth mentioning here that the most common adverse effects of Rasagiline are: severe recurrent hypoglycemia (Ibrahim et al. 2017) orthostatic hypotension, headache, and nausea (Sun and Armstrong 2021), as well as the problem of drug–drug interactions (McCormack 2014). Also, the most commonly reported adverse effect of istradefylline was dyskinesia. Other common side effects that occurred with greater frequency than placebo were dizziness, constipation, nausea, hallucinations, and insomnia (Chen and Cunha 2020; Sako et al. 2017; Cummins and Cates 2022).

From the previous discussion, it can be seen that the new compounds L24 and L32 formed stable complexes with high negative energy scores, which is ensured by the presence of different interactions with hMAO-B and hA2AR targets, respectively.

Finally, from the comparison of our results with different clinical drugs (see Table 9), we can conclude that our compounds could be excellent drug candidates because they exhibit a high affinity with both targets (hMAO-B and hA2AR), implying a good inhibition of these enzymes compared to other compounds (Table S3 in the S.I section).

In addition, the ADME-T prediction showed that both compounds L24 and L32 satisfy all the criteria of drug-likeness without any violation of Lipinski, Veber, and Egan rules. Also, these compounds were characterized by high lipophilicity and a high coefficient of skin permeability LogKp, therefore, penetrating the CNS.

Conclusion

The present work focused on studying and screening of the hMAO-B and hA2AR inhibitory activities of phenylxanthine (PX) derivatives in a quest to find low-cost and potent anti-Parkinson disease molecules with no or minimum toxicity.

A library of 38 phenylxanthine (PX) derivatives has been tested using five computational approaches: molecular docking, molecular dynamic simulations, MEP, bioisosteric replacement, and ADME/T properties.

The molecular docking/dynamics results revealed that among all evaluated compounds of phenylxanthine (PX) derivatives, compounds L24 and L32 showed a high affinity (high negative score) with hMAO-B and hA2AR targets, respectively, which was confirmed by the formation of the strong hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic interactions with the active residues of both targets.

In addition, MEP maps were used to identify positive regions that are vulnerable to nucleophilic attacks and negative regions that preferentially attract electrophilic reagents of both compounds L24 and L32 in order to help the bioisosteric replacement approach creating and designing new analogs for each compound with similar biological activities and additional enhanced characteristics.

Moreover, compounds L24, L32, and their analogs were identified and their ADME-T and Drug-likeness prediction reveal promising pharmacokinetic properties and oral bioavailability.

Also, the comparative study of our results with clinical tests confirmed that compounds L24, L32, and their analogs are potent hMAO-B and hA2AR inhibitors and may have enhanced and very potent therapeutic value in the treatment of the PD.

Finally, these results suggested that compounds L24, L32, and their analogs are good multi-targets drug candidates for designing a lead compound for Parkinson’s disease.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Authors thanks the Algerian Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research for the support under the PRFU project (approval No. B00L01UN130120190009) and ensure that there is no conflict of interest regarding this paper.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

All data related to this study are included herein otherwise available on request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abdullah R, Basak I, Patil KS, Alves G, Larsen JP, Møller SG. Parkinson’s disease and age: the obvious but largely unexplored link. Exp Gerontol. 2015;68:33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anighoro A, Bajorath J, Rastelli G. Polypharmacology: challenges and opportunities in drug discovery. J Med Chem. 2014;57:7874–7887. doi: 10.1021/jm5006463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azam F, Abodabos HS, Taban IM, Rfieda AR, Mahmood D, Anwar MJ, Khan S, Sizochenko N, Poli G, Tuccinardi T, Ali HI. Rutin as promising drug for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease: an assessment of MAO-B inhibitory potential by docking, molecular dynamics and DFT studies. Mol Simul. 2019;45(18):1563–1571. doi: 10.1080/08927022.2019.1662003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bajda M, Więckowska A, Hebda M, Guzior N, Sotriffer CA, Malawska B. Structure-based search for new inhibitors of cholinesterases. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14(3):5608–5632. doi: 10.3390/ijms14035608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee P, Eckert AO, Schrey AK. ProTox-II: a webserver for the prediction of toxicity of chemicals. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(W1):W257–W263. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee P, Dehnbostel FO, Preissner R. Prediction is a balancing act: importance of sampling methods to balance sensitivity and specificity of predictive models based on imbalanced chemical data sets. Front Chem. 2018 doi: 10.3389/fchem.2018.00362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolotti LJ, Flurchick K. An introduction to density functional theory. In: Lipkowitz KB, Boyd D, editors. Reviews in computational chemistry. New York: VCH; 1996. pp. 187–260. [Google Scholar]

- Belaidi AA, Bush AI. Iron neurochemistry in Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease: targets for therapeutics. J Neurochem. 2016;139:179–197. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belkadi A, Kenouche S, Melkemi N, Daoud I, Djebaili R. K-means clustering analysis, ADME/pharmacokinetic prediction, MEP, and molecular docking studies of potential cytotoxic agents. Struct Chem. 2021;32(6):2235–2249. doi: 10.1007/s11224-021-01796-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Binda C, Newton-Vinson P, Hubalek F, Edmondson DE, Mattevi A. Structure of human monoamine oxidase B, a drug target for the treatment of neurological disorders. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9(1):22–26. doi: 10.1038/nsb732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binda C, Wang J, Pisani L, Caccia C, Carotti A, Salvati P, Edmondson DE, Mattevi A. Structures of human monoamine oxidase B complexes with selective noncovalent inhibitors: safinamide and coumarin analogs. J Med Chem. 2007;50(23):5848–5852. doi: 10.1021/jm070677y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaventura J, Rico AJ, Moreno E, et al. L-DOPA-treatment in primates disrupts the expression of A2A adenosine-CB1 cannabinoid-D2 dopamine receptor heteromers in the caudate nucleus. Neuropharmacology. 2014;79:90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brünger A, Brooks IIICL, Karplus M. Stochastic boundary conditions for molecular dynamics simulations of ST2 water. Chem Phys Lett. 1984;105(5):495–500. doi: 10.1016/0009-2614(84)80098-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brunschweiger A, Koch P, Schlenk M, Pineda F, Küppers P, Hinz S, Müller CE. 8-Benzyltetrahydropyrazino [2, 1-f] purinediones: water-soluble tricyclic xanthine derivatives as multitarget drugs for neurodegenerative diseases. Chem Med Chem. 2014;9(8):1704–1724. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201402082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burley SK, Petsko GA. Aromatic–aromatic interaction: a mechanism of protein structure stabilization. Science. 1985;229(4708):23–28. doi: 10.1126/science.3892686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carradori S, Petzer JP. Novel monoamine oxidase inhibitors: a patent review (2012–2014) Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2014;25:91–101. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2014.982535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli A, Bolognesi ML, Mìnarini A, Rosini M, Tumiatti V, Recanatini M, Melchiorre C. Multi-target-directed ligands to combat neurodegenerative diseases. J Med Chem. 2008;51:347–372. doi: 10.1021/jm7009364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaurasiya ND, Zhao J, Pandey P, Doerksen RJ, Muhammad I, Tekwani BL. Selective inhibition of human monoamine oxidase B by acacetin 7-methyl ether isolated from turnera diffusa (Damiana) Molecules. 2019;24(4):810. doi: 10.3390/molecules24040810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JF, Cunha RA. The belated US FDA approval of the adenosine A2A receptor antagonist istradefylline for treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Purinergic Signal. 2020;16(2):167–174. doi: 10.1007/s11302-020-09694-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenafa H, Mesli F, Daoud I, Achiri R, Ghalem S, Neghra A. In silico design of enzyme α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitors using molecular docking, molecular dynamic, conceptual DFT investigation and pharmacophore modelling. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2021 doi: 10.1080/07391102.2021.1882340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins L, Cates ME. Istradefylline: a novel agent in the treatment of “off” episodes associated with levodopa/carbidopa use in Parkinson disease. Mental Health Clin. 2022;12(1):32–36. doi: 10.9740/mhc.2022.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daina A, Michielin O, Zoete V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):1–13. doi: 10.1038/srep42717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daoud I, Melkemi N, Salah T, Ghalem S. Combined QSAR, molecular docking and molecular dynamics study on new acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitors. Comput Biol Chem. 2018;74:304–326. doi: 10.1016/j.compbiolchem.2018.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta S, Mukherjee S, Sekar K, Mukhopadhyay BP. The conformational dynamics of wing gates Ile199 and Phe103 on the binding of dopamine and benzylamine substrates in human monoamine Oxidase B. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2021;39(5):1879–1886. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1734483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Colibus L, Li M, Binda C, Lustig A, Edmondson DE, Mattevi A. Three-dimensional structure of human monoamine oxidase A (MAO A): relation to the structures of rat MAO A and human MAO B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(36):12684–12689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505975102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doré AS, Robertson N, Errey JC, Ng I, Hollenstein K, Tehan B, Hurrell E, Bennett K, Congreve M, Magnani F, Tate CG, Weir M, Marshall FH. Structure of the adenosine A2A receptor in complex with ZM241385 and the xanthines XAC and caffeine. Structure. 2011;19(9):1283–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drwal MN, Banerjee P, Dunkel M, Wettig MR, Preissner R. ProTox: a web server for the in silico prediction of rodent oral toxicity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(W1):W53–W58. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dungo R, Deeks ED. Istradefylline: first global approval. Drugs. 2013;73(8):875–882. doi: 10.1007/s40265-013-0066-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunkel P, Chai CL, Sperlagh B, Huleat PB, Matyus P. Clinical utility of neuroprotective agents in neurodegenerative disease: current status of drug development for Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and Huntington’s diseases, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Exp Opin Investig Drugs. 2012;21:1267–1308. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2012.703178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finberg JPM. Update on the pharmacology of selective inhibitors of MAO-A and MAO-B: Focus on modulation of CNS monoamine neurotransmitter release. Pharmacol Ther. 2014;143(2):133–152. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas ME, Fox SH. Nondopaminergic treatments for Parkinson’s disease: current and future prospects. Neurodegener Dis Manage. 2016;6(3):249–268. doi: 10.2217/nmt-2016-0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch MJ, Trucks GW, Schlegel HB, Scuseria GE, Robb MA, Cheeseman JR, Scalmani G, Barone V, Mennucci B, Petersson G, Nakatsuji H. Gaussian 09, Revision d. 01. Wallingford, CT: Gaussian. Inc.; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hevener KE, Zhao W, Ball DM, Babaoglu K, Qi J, White SW, Lee RE. Validation of molecular docking programs for virtual screening against dihydropteroate synthase. J Chem Inf Model. 2009;49(2):444–460. doi: 10.1021/ci800293n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong R, Li X. Discovery of monoamine oxidase inhibitors by medicinal chemistry approaches. Med Chem Comm. 2019;10(1):10–25. doi: 10.1039/C8MD00446C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu SW, Nian SY, Qin KY, Xiao T, Li L, Qi X, Ye F, Liang G, Hu G, He J, Yu Y, Song B. Design, synthesis and inhibitory activities of 8-(substituted styrol-formamido) phenyl-xanthine derivatives on monoamine oxidase B. Chem Pharm Bull. 2012;60:385–390. doi: 10.1248/cpb.60.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey W, Dalke A, Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J Mol Graph. 1996;14(1):33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim FAB, Rashid F, Hussain AAB, Alawadi F, Bashier A. Rasagiline-induced severe recurrent hypoglycemia in a young woman without diabetes: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2017;11(1):1–4. doi: 10.1186/s13256-017-1202-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imberty A, Hardman KD, Carver JP, Perez S. Molecular modelling of protein-carbohydrate interactions. Docking of monosaccharides in the binding site of concanavalin A. Glycobiology. 1991;1(6):631–642. doi: 10.1093/glycob/1.6.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaiteh M, Zeifman A, Saarinen M, Svenningsson P, Bréa J, Loza MI, Carlsson J. Docking screens for dual inhibitors of disparate drug targets for Parkinson’s disease. J Med Chem. 2018;61(12):5269–5278. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janiak C. A critical account on n–n stacking in metal complexes with aromatic nitrogen-containing ligands. J Chem Soc Dalton Trans. 2000;21:3885–3896. doi: 10.1039/b003010o. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jankovic J, Poewe W. Therapies in Parkinson’s disease. Curr Opin Neurol. 2012;25:433–447. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e3283542fc2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffrey GA, Jeffrey GA. An introduction to hydrogen bonding. New York: Oxford University Press; 1997. p. 228. [Google Scholar]

- Kakkar AK, Dahiya N. Management of Parkinson’s disease: current and future pharmacotherapy. EurJ Pharmacol. 2015;750:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch P, Akkari R, Brunschweiger A, Borrmann T, Schlenk M, Küppers P, Müller CE. 1, 3-Dialkyl-substituted tetrahydropyrimido [1, 2-f] purine-2, 4-diones as multiple target drugs for the potential treatment of neurodegenerative diseases. Bioorg Med Chem. 2013;21(23):7435–7452. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.09.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs JA, Chacón P, Abagyan R. Predictions of protein flexibility: first-order measures. Proteins Struct Funct Bioinform. 2004;56(4):661–668. doi: 10.1002/prot.20151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Yang W, Parr RG. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys Rev B. 1988;37(2):785–789. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Blanco JR, Garzón JI, Chacón P. iMod: multipurpose normal mode analysis in internal coordinates. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(20):2843–2850. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Blanco JR, Aliaga JI, Quintana-Ortí ES, Chacón P. iMODS: internal coordinates normal mode analysis server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:W271–W276. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T, Chen F. Multiwfn: a multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J Comput Chem. 2012;33(5):580–592. doi: 10.1002/jcc.22885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack PL. Rasagiline: a review of its use in the treatment of idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. CNS Drugs. 2014;28(11):1083–1097. doi: 10.1007/s40263-014-0206-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellado M, Salas CO, Uriarte E, Viña D, Jara-Gutiérrez C, Matos MJ, Cuellar M. Design, synthesis and docking calculations of prenylated chalcones as selective monoamine oxidase B inhibitors with antioxidant activity. Chemistry Select. 2019;4(26):7698–7703. doi: 10.1002/slct.201901282. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith GE, Totterdell S, Beales B, Meshul CK. Impaired glutamate homeostasis and programmed cell death in a chronic MPTP mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Exp Neurol. 2009;219(1):334–340. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesli F, Daoud I, Ghalem S. Antidiabetic activity of Nigella sativa (BLACK SEED)-by molecular modeling elucidation, molecular dynamic, and conceptual DFT investigation. Pharmacophore. 2019;10(5):57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) (2014) 2014.09. Chemical Computing Group Inc.: 1010 Sherbooke St. West, Suite #910, Montreal, QC, Canada, H3A 2R7

- Murray JS, Politzer P. The electrostatic potential: an overview. Wiley Interdiscipl Rev Comput Mol Sci. 2011;1(2):153–163. doi: 10.1002/wcms.19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murray JS, Brinck T, Lane P, Paulsen K, Politzer P. Statistically-based interaction indices derived from molecular surface electrostatic potentials: a general interaction properties function (GIPF) J Mol Struct (Theochem) 1994;307:55–64. doi: 10.1016/0166-1280(94)80117-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Murray JS, Concha MC, Politzer P. Links between surface electrostatic potentials of energetic molecules, impact sensitivities and C-NO2/N–NO2 bond dissociation energies. Mol Phys. 2009;107(1):89–97. doi: 10.1080/00268970902744375. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olanow CW, Rascol O, Hauser R, Feigin PD, Jankovic J, Lang A, Langston W, Melamed E, Poewe W, Stocchi F, Tolosa E. A double-blind, delayed-start trial of rasagiline in Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(13):1268–1278. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petzer JP, Castagnoli N, Schwarzschild MA, Chen JF, Van der Schyf CJ. Dual-target-directed drugs that block monoamine oxidase B and adenosine A2A receptors for Parkinson’s disease. Neurotherapeutics. 2009;6:141–151. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2008.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piovesan D, Minervini G, Tosatto SCE. The RING 2.0 web server for high quality residue interaction networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):W367–W374. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pires DE, Blundell TL, Ascher DB. pkCSM: predicting small-molecule pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties using graph-based signatures. J Med Chem. 2015;58(9):4066–4072. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisani L, Catto M, Leonetti F, Nicolotti O, Stefanachi A, Campagna F, Carotti A. Targeting monoamine oxidases with multipotent ligands: an emerging strategy in the search of new drugs against neurodegenerative diseases. Curr Med Chem. 2011;18(30):4568–4587. doi: 10.2174/092986711797379302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavachari K. Perspective on “Density functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange”. Theor Chem Acc. 2000;103:361–363. doi: 10.1007/s002149900065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riederer P, Lachenmayer L, Laux G. Clinical applications of MAO-inhibitors. Curr Med Chem. 2004;11:2033–2043. doi: 10.2174/0929867043364775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivara S, Piersanti G, Bartoccini F, Diamantini G, Pala D, Riccioni T, Stasi MA, Cabri W, Borsini F, Mor M, Tarzia G, Minetti P. Synthesis of (E)-8-(3-chlorostyryl)caffeine analogues leading to 9-deazaxanthine derivatives as dual A2A antagonists/MAO-B inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2013;56(3):1247–1261. doi: 10.1021/jm301686s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sako W, Murakami N, Motohama K, Izumi Y, Kaji R. The effect of istradefylline for Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:18018. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-18339-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzschild MA, Agnati L, Fuxe K, Chen JF, Morelli M. Targeting adenosine A2A receptors in Parkinson’s disease. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29(11):647–654. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan J, Ji C. MolOpt: a web server for drug design using bioisosteric transformation. Curr Comput Aided Drug Des. 2020;16(4):460–466. doi: 10.2174/1573409915666190704093400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simeonova R, Zheleva D, Valkova I, Stavrakov G, Philipova I, Atanasova M, Doytchinova I. A novel galantamine-curcumin hybrid as a potential multi-target agent against neurodegenerative disorders. Molecules. 2021;26(7):1865. doi: 10.3390/molecules26071865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song B, Xiao T, Qi X, Li LN, Qin K, Nian S, Hu GX, Yu Y, Liang G, Ye F. Design and synthesis of 8-substituted benzamido-phenylxanthine derivatives as MAO-B inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012;22:1739–1742. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.12.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson J, Nutma E, van der Valk P, Amor S. Inflammation in CNS neurodegenerative diseases. Immunology. 2018;154(2):204–219. doi: 10.1111/imm.12922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitou M, Toufik H, Bouachrine M, Lamchouri F. Quantitative structure–activity relationships analysis, homology modeling, docking and molecular dynamics studies of triterpenoid saponins as Kirsten rat sarcoma inhibitors. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2021;39(1):152–170. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2019.1707122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stosel A, Schlenk M, Hinz S, Küppers P, Heer J, Gütschow M, Müller CE. Dual targeting of adenosine A2A receptors and monoamine oxidase B by 4H–3,1-benzothiazin-4-ones. J Med Chem. 2013;56(11):4580–4596. doi: 10.1021/jm400336x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C, Armstrong MJ. Treatment of Parkinson’s disease with cognitive impairment: current approaches and future directions. Behav Sci. 2021;11(4):54. doi: 10.3390/bs11040054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo M, Lim HD, Klein Herenbrink C, Christopoulos A, Lane JR, Capuano B. Proof of concept study for designed multiple ligands targeting the dopamine D2, serotonin 5-HT2A, and muscarinic M1 acetylcholine receptors. J Med Chem. 2015;58:1550–1555. doi: 10.1021/jm5013243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talati R, Reinhart K, Baker W, White CM, Coleman CI. Pharmacologic treatment of advanced Parkinson’s disease: a meta-analysis of COMT inhibitors and MAO-B inhibitors. Park Relat Disord. 2009;15(7):500–505. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toda M, Kubo R, Saitō N, Hashitsume N. Statistical physics II: nonequilibrium statistical mechanics. New York: Springer Science & Business Media; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Tóth A, Antal Z, Bereczki D, Sperlágh B. Purinergic signalling in Parkinson’s disease: a multi-target system to combat neurodegeneration. Neurochem Res. 2019;44(10):2413–2422. doi: 10.1007/s11064-019-02798-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toumi A, Boudriga S, Hamden K, Daoud I, Askri M, Soldera A, Jean-Francois L, Carsten S, Lukas B, Knorr M. Diversity-oriented synthesis of spiropyrrolo [1, 2-a] isoquinoline derivatives via diastereoselective and regiodivergent three-component 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reactions: in vitro and in vivo evaluation of the antidiabetic activity of rhodanine analogues. J Org Chem. 2021;86(19):13420–13445. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.1c01544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzvetkov NT, Antonov L. Subnanomolar indazole-5-carboxamide inhibitors of monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) continued: indications of iron binding, experimental evidence for optimised solubility and brain penetration. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2017;32(1):960–967. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2017.1344980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Walt MM, Terre’Blanche G, Petzer A, Petzer JP. The adenosine receptor affinities and monoamine oxidase B inhibitory properties of sulfanylphthalimide analogues. Bioorg Chem. 2015;59:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2015.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade RC, Goodford PJ. The role of hydrogen-bonds in drug binding. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1989;289:433–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Skeel RD. Analysis of a few numerical integration methods for the Langevin equation. Mol Phys. 2003;101(14):2149–2156. doi: 10.1080/0026897031000135825. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Han C, Xu Y, Wu K, Chen S, Hu M, Wang L, Ye Y, Ye F. Synthesis and evaluation of phenylxanthine derivatives as potential dual A2AR antagonists/MAO-B inhibitors for Parkinson’s disease. Molecules. 2017;22(6):1010. doi: 10.3390/molecules22061010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel TJ, Klegeris A. Novel multi-target directed ligand-based strategies for reducing neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Life Sci. 2018;207:314–322. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2018.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu WY, Dai YC, Li NG, Dong ZX, Gu T, Shi ZH, Duan JA. Novel multitarget-directed tacrine derivatives as potential candidates for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2017;32(1):572–587. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2016.1210139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang T, Sui X, Yu B, Shen Y, Cong H. Recent advances in the rational drug design based on multi-target ligands. Curr Med Chem. 2020;27(28):4720–4740. doi: 10.2174/0929867327666200102120652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youdi MBH, Edmondson D, Tipton KF. The therapeutic potential of monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:295–309. doi: 10.1038/nrn1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Załuski M, Schabikowski J, Schlenk M, Olejarz-Maciej A, Kubas B, Karcz T, Kieć-Kononowicz K. Novel multi-target directed ligands based on annelated xanthine scaffold with aromatic substituents acting on adenosine receptor and monoamine oxidase B. Synthesis, in vitro and in silico studies. Bioorg Med Chem. 2019;27(7):1195–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2019.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhukov A, Andrews SP, Errey JC, Robertson N, Tehan B, Mason JS, Marshall FH, Weir M, Congreve M. Biophysical mapping of the adenosine A2A receptor. J Med Chem. 2011;54(13):4312–4323. doi: 10.1021/jm2003798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data related to this study are included herein otherwise available on request.