Abstract

Response surface methodology (RSM) was used to optimize the ultrasound-assisted extraction conditions of Ginkgo biloba leaves polysaccharide (GBLP). The optimum extraction conditions for the ultrasound-assisted extraction of GBLP were obtained as liquid to material ratio of 30 mL/g, ultrasonic power of 340 W, and extraction time of 50 min. Under these conditions, the yield of GBLP was 5.37 %. Two chemically modified polysaccharides, CM-GBLP and Ac-GBLP, were obtained by carboxymethylation and acetylation of GBLP. The physicochemical properties of these three polysaccharides were comparatively studied and their in vitro antioxidant activities were evaluated comprehensively. The results showed that the solubility of the chemically modified polysaccharides was significantly enhanced and the in vitro antioxidant activity was somewhat improved. This suggests that carboxymethylation and acetylation are effective methods to enhance polysaccharide properties, but the results exhibited some uncontrollability. At the same time, GBLP has also shown high potential for research and application.

Keywords: Polysaccharide; Ginkgo biloba leaves; Ultrasound-assisted extraction, Properties

1. Introduction

Recently, ultrasound-assisted extraction has been widely favored for its compliance with the concept of green chemistry and economic chemistry, and it has been increasingly used in natural product extraction. Compared with the traditional solvent extraction method, ultrasound-assisted extraction takes less time, requires lower temperature and has higher extraction efficiency. Therefore, it is suitable for the extraction of some temperature-sensitive products. Meanwhile, it is simpler and more economical than some emerging extraction methods, such as microwave extraction, supercritical fluid extraction, enzyme extraction, etc. The principle of ultrasound-assisted extraction is based on the ability of ultrasound to produce cavitation, thermal and mechanical effects, among which cavitation is considered to be the most important factor [8]. When the ultrasonic wave acts on the extraction solvent, the liquid in the solvent will be torn into many small cavities in some areas of weak tension, and these small cavities will rapidly expand and close so that the violent impact between the liquid particles occurs. This impact action can easily break the plant cell wall, thus releasing intracellular substances into the extraction solvent, while thermal and mechanical effects also contribute to this process. It has been well documented that ultrasound-assisted extraction not only increases the extraction rate, but also improves the activity of polysaccharides extracted by ultrasound [24]. In view of this, the RSM was used to optimize the conditions of ultrasound-assisted extraction of polysaccharides from Ginkgo biloba leaves. RSM is a statistical method to find the optimal process parameters and solve the multivariate problems through the analysis of regression equations, which is commonly used in the design of natural product extraction experiments. These schemes are used to solve the problems of low efficiency and long time consumption of polysaccharides extraction.

Plant polysaccharides are a class of natural polymers composed of more than ten monosaccharides connected by glycosidic bonds, which are widely present in natural plants, including starch, cellulose, polysaccharides, pectin and so on. Some water-soluble plant polysaccharides with obvious resistance are called plant active polysaccharides, which have anti-tumor, immunomodulatory, hypoglycemic, antioxidant, hepatoprotective, antiviral and intestinal regulation activities [10], [9], [28], [32], [29], [49], [31], [33], [13], [35], [36], [37], [38], [30], [34]. Because of its easy accessibility, low toxicity and biodegradability, it has become a hotspot for research on bioactive substances. Recently, a large number of new plant polysaccharides have been reported, and GBLP is one of them. Ginkgo biloba L. is a plant of the Ginkgo genus under the family Ginkgoaceae, which is called a “living fossil” and is an ancient tree species native to China. Fresh Ginkgo biloba leaves are light green fan-shaped leaves with long stalks, and are used as a medicinal herb in China for its antitussive, blood-promoting, anti-depressant and cholesterol-lowering properties [15]. Polysaccharides play an important role in the activity of Ginkgo biloba leaves. At present, there are relatively few studies on GBLP, and it indicates that GBLPs have good antioxidant activity and immunomodulatory activity [16]. Therefore, GBLPs still have a wide range of research value and space.

The activity of polysaccharides is influenced by various factors, such as molecular weight, spatial structure, solubility, etc. Some inactive or less active polysaccharides are difficult to be applied. Chemical modification of polysaccharides provides a solution to this difficulty, as it is an effective means to improve activity, which includes sulfation, selenization, phosphorylation, carboxymethylation, acetylation, amination, etc [4], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [35], [39], [48], [49]. Chemical modification will change the type of polysaccharide substituent, number of substituents, spatial structure, molecular weight, solubility, etc., so as to achieve the purpose of improving the activity. In this study, GBLP was modified by acetylation and carboxymethylation, and the solubility and in vitro antioxidant activity of the modified and unmodified polysaccharides were analyzed and compared. This provides some clues to solve the difficult problem of poor polysaccharide activity and solubility, and also provides some reference values for the application of GBLPs.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials and reagents

Ginkgo biloba leaves picked from the campus of Chongqing Normal University were washed and dried in an oven at 60 ℃ and then ground into powder for use. Petroleum ether, n-butanol, chloroform, chloroacetic acid, isopropyl alcohol, acetic anhydride, ethanol, salicylic acid, H2O2, FeSO4, thiobarbituric acid, trichloroacetic acid were obtained from Chengdu Cologne Chemical Co., Ltd. (Chengdou, China). Concentrated sulfuric acid, concentrated hydrochloric acid and NaOH were obtained from Chuandong Chemical Co., Ltd. (Chengdou, China). Soy lecithin was obtained from Shanghai yuanye Bio-Technology Co., Ltd .(Shanghai, China). DPPH was obtained from RHAWN Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). All other relevant reagents were of analytical purity grade.

2.2. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of GBLPs

The dried powder of Ginkgo biloba leaves was added to petroleum ether (1:15 g/mL) and refluxed at 80 ℃ for 2 h to remove lipids and pigments. After reflux, the residue was collected by filtration and dried. Five milligrams of the above residue was added to a certain proportion of distilled water to extract polysaccharides by ultrasound-assisted extraction under certain temperature, power and time conditions. After the reaction was completed, the filtrate collected by filtration was concentrated to 50 mL under reduced pressure, and then 20 mL of Sevag reagent (n-butanol: chloroform = 1:4) was added and reacted under shaking for 25 min to remove the protein. Then, the supernatant was collected by centrifugation after the mixture was allowed to stand for 15 min, and this supernatant was dialyzed overnight with distilled water in a 3500 Da dialysis bag. Finally, anhydrous ethanol was added to the dialysate to make the final concentration of ethanol reach 75 %, and the solid was collected by centrifugation. This solid was washed with anhydrous ethanol, acetone and ether in turn and then freeze-dried to obtain GBLPs. The total sugar content was determined by phenol-sulfuric acid method [7]. The yield of GBLPs was calculated according to the following equation:

| (1) |

2.3. Single-factor experiments

Single-factor experiments of liquid to material ratio, extraction time and ultrasonic power were performed sequentially according to the extraction method in 2.2 to determine the range of variables. The resulting optimal single-factor was used as a fixed condition for the next single-factor experiment. The single-factor experimental conditions of liquid to material ratio included 10 mL/g, 20 mL/g, 30 mL/g, 40 mL/g, and 50 mL/g; The single-factor experimental conditions of extraction time included 20 min, 30 min, 40 min, 50 min, and 60 min; The single-factor experimental conditions of ultrasonic power included 216 W, 252 W, 288 W, 324 W, and 360 W.

2.4. Experimental design for optimal conditions

The liquid to material ratio (A), ultrasonic power (B), and extraction time (C) were used as three factors to explore the optimal conditions for ultrasound-assisted extraction of GBLPs using RSM. Based on the results of the single-factor test, three appropriate levels were selected for each factor (Table 1). RSM experiments with three factors and three levels were designed according to the Box-Behnken central combination model using the yield of GBLPs as the response value. The regression fitting model was represented by the following second order polynomial:

| (2) |

Where Y is the predicted response value; Ai, Aii, and Aij are the primary term coefficients, quadratic term coefficients, and interaction term coefficients, respectively; and Xi and Xj are independent variables.

Table 1.

Three independent variables and their levels.

| Factor | Unit | Symbol | Levels |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −1 | 0 | 1 | |||

| Ratio of liquid to material | mL/g | A | 15 | 25 | 35 |

| Ultrasonic power | W | B | 288 | 324 | 360 |

| Extraction time | min | C | 40 | 50 | 60 |

2.5. Preparation of CM-GBLPs

The carboxymethylation of GBLPs was slightly modified from the previous method [6]. One gram of GBLPs was added to 80 mL of NaOH (20 %, w/v) and stirred for 1 h to dissolve it fully, and then 80 mL of chloroacetic acid-isopropanol solution (1.2 g/mL) was slowly added to react at 55 ℃ for 5 h. After the reaction was completed, the pH value was adjusted to neutral with 2 mol/L HCl. Then, the reaction solution was dialyzed with running water and distilled water sequentially for 1 d, and ethanol was added to precipitate to obtain CM-GBLPs.

The substitution degree of CM-GBLPs was determined by titration method [3]. Ten milligrams of CM-GBLPs was added to 10 mL of NaOH solution (0.01 mol/L) and stirred in a water bath at 45 ℃ for 30 min. The above solution was titrated with 0.01 mol/L HCl using phenolphthalein as indicator. The degree of substitution of CM-GBLPs was calculated according to the following equation:

| (3) |

Where m is the amount of NaOH consumed per gram of sample calculated from the titration.

2.6. Preparation of Ac-GBLPs

The preparation of Ac-GBLPs was referred to the method of Xie et al [19]. Briefly, 1 g of GBLPs was dissolved in 25 mL of distilled water and its pH value was adjusted to 9 with NaOH (10 mol/L) solution. Next, 10 mL of acetic anhydride was slowly added to the above solution, and the pH value was adjusted with NaOH solution to keep the pH value between 9 and 10 throughout the process. After the above operation was completed, the reaction solution was reacted at room temperature for 2 h, and then the pH value was adjusted to neutral with HCl solution. Finally, the above reaction solution was dialyzed with running water and distilled water for one day in turn, and ethanol was added to it for precipitation to obtain Ac-GBLPs.

The substitution degree of Ac-GBLPs was determined by titration method [19]. Briefly, 20 mg of Ac-GBLPs was added to 10 mL of NaOH solution (0.01 mol/L) and stirred in a water bath at 50 ℃ for 2 h. The above solution was titrated with 0.01 mol/L HCl using phenolphthalein as indicator. The degree of substitution of Ac-GBLPs was calculated according to the following equation:

| (4) |

where n (%) is the amount of acetyl group calculated from the titration.

2.7. Solubility test

The determination of solubility was slightly improved on the method described by Kong et al [11]. Briefly, 40 mg of polysaccharide samples were added to a 50 mL flask containing 10 mL of distilled water and allowed to dissolve by magnetic stirring (200 r/min) in a water bath at different temperatures (20 ℃, 40 ℃, 60 ℃, 80 ℃, 100 ℃). The time consumed for complete dissolution was recorded and plotted linearly against temperature. Another 120 mg of polysaccharide samples were taken with 10 mL of centrifuge tube, and 4 mL of distilled water was added to dissolve it by ultrasonication at room temperature for 30 min. The precipitate obtained by centrifugation of the above mixture was dried and weighed, and the weight was recorded as × (g). The maximum solubility was calculated according to the following equation:

| (5) |

2.8. Infrared spectroscopy and nuclear magnetic resonance determination

The appropriate amounts of polysaccharide samples were ground evenly together with KBr and pressed into a thin slice for determination by infrared spectrometer. A thin slice composed entirely of KBr was used as the background, and the detection wavelength was 4000 to 400 cm−1.

The polysaccharide samples (45 mg) were fully dissolved in 0.5 mL of heavy water (99.99 %) in an ultrasonic water bath and transferred to a nuclear magnetic tube for NMR analysis.

2.9. Determination of hydroxyl radical scavenging activity

The method for the determination of hydroxyl radical scavenging activity was slightly modified on the previous method [14]. Briefly, 1 mL FeSO4 (8 mmol/L), 1 mL salicylic acid–ethanol solution (8 mmol/L), and 1 mL H2O2 (8 mmol/L) were added sequentially to 1 mL polysaccharide solution (0.125 mg/L, 0.25 mg/L, 0.5 mg/L, 1.0 mg/L, 2.0 mg/L, 4.0 mg/L) to initiate the reaction. The reaction was carried out in a water bath at 37 ℃ for 30 min. The absorbance of the reaction solution was measured at 510 nm using distilled water as a blank control and Vc as a positive control. The hydroxyl radical scavenging activity was calculated according to the following equation:

| (6) |

Where a1 is the absorbance of the sample; a2 is the background absorbance of the sample; a0 is the absorbance of the blank.

2.10. Determination of DPPH radical scavenging ability

The DPPH radical scavenging ability was determined according to the method described by Chen et al [2]. Briefly, 4 mL of DPPH-ethanol solution (0.5 mmol/L) and 2 mL of polysaccharide solution (0.125 mg/L, 0.25 mg/L, 0.5 mg/L, 1.0 mg/L, 2.0 mg/L, 4.0 mg/L) were mixed and reacted for 50 min in the dark. The absorbance of the above reaction solution was measured at 517 nm using distilled water as a blank control and Vc as a positive control. The anti-lipid peroxidation ability was calculated according to the following equation:

| (7) |

Where b1 is the absorbance of the sample; b2 is the background absorbance of the sample; b0 is the absorbance of the blank.

2.11. Determination of anti-lipid peroxidation ability

The anti-lipid peroxidation ability was determined by referring to the method of Chen et al. [2]. Briefly, 2 mL of soy lecithin solution configured from PBS (pH = 7) and 0.4 mL of FeSO4 solution (10 mmol/L) were added sequentially to 2 mL of polysaccharide solution (0.125 mg/L, 0.25 mg/L, 0.5 mg/L, 1.0 mg/L, 2.0 mg/L, 4.0 mg/L) and this reaction was carried out in a 37 ℃ water bath for 50 min. After the reaction was completed and the reaction liquid was cooled to room temperature, 1 mL TCA (20 %, w/v) and 1 mL thiobaric acid (0.8 %, w/v) were added and transferred to a boiling water bath for reaction for 20 min. Then, the reaction solution was allowed to cool to room temperature and the supernatant was obtained by centrifugation. The absorbance of the above supernatant was measured at 535 nm using Vc as a positive control and PBS solution as a blank control. The anti-lipid peroxidation ability was calculated according to the following equation:

| (8) |

Where c1 is the absorbance of the sample; c2 is the background absorbance of the sample; c0 is the absorbance of the blank.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Effect of different factors on ultrasound-assisted extraction efficiency

As shown in Fig. 1A, the yield of GBLPs increased faster with the increase of the liquid to material ratio at lower liquid to material ratios. This may be explained by the increase in solvent ratio resulting in higher osmotic pressure of the cells and thus accelerating the efflux of intracellular material. On the other hand, the increase in solvent volume led to a larger area of ultrasonic action, which resulted in greater ultrasonic efficiency. This trend continued until the liquid to material ratio reached 25 mL/g, at which time the yield of GBLPs also reached the extreme value. After that, the yield of GBLPs gradually decreased as the liquid to material ratio continued to increase, which may be due to the excessive liquid to material ratio reduced the intermolecular interactions, resulting in a significant reduction of ultrasonic penetration [26].

Fig. 1.

Single-factor analysis: (A) Effect of ratio of liquid to material on yield of GBLPs; (B) Effect of ultrasonic power on the yield of GBLPs; (C) Effect of extraction time on yield of GBLPs.

As shown in Fig. 1B, the yield of GBLPs increased sharply when the ultrasonic power increased from 200 W to 300 W, and then the increase of yield of GBLPs leveled off. With the increase of ultrasonic power, the cavitation effect, thermal effect and mechanical effect were enhanced, which leaded to the increase of yield of GBLPs. However, when the ultrasonic power was too high, the polysaccharides in the solvent were subjected to ultrasound leading to the degradation of polysaccharides [27]. These two mechanisms may be responsible for the trend of GBLPs yields in Fig. 1B.

As shown in Fig. 1C, the yield of GBLPs increased rapidly with the increase of extraction time, and reached the extreme value at 50 min. Subsequently, the yield of GBLPs started to decrease with the increase of extraction time. This trend may be the result of a combination of two factors. On the one hand, with the increase of time, the accumulation of thermal effect accelerated the outflow of polysaccharide from raw materials, so the yield of GBLPs increased. On the other hand, the increase in extraction time caused the solution concentration to become larger, resulting in a smaller cellular osmotic pressure. At the same time, the polysaccharides in the solution were degraded due to the time accumulation effect, so the yield of polysaccharide decreased [27].

3.2. Optimization of ultrasonic extraction conditions

3.2.1. Model fitting and statistical analysis

The matrix of RSM was designed by Design-Expert 12 software (Table 2). The experiment was randomly divided into 17 groups, of which 12 groups were interactive experiments and the other 5 groups were central repeated experiments for error analysis. Through multiple regression analysis, the relationship between the response value and the factors was obtained as follows:

Table 2.

Box-Behnken experimental design with results for extraction of GBLPs yield.

| Run Order | Ratio of liquid to material (mL/g) |

Ultrasonic power (W) |

Extraction time (min) |

Yield (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | Actual Value | Predicted Value | |

| 1 | 25 | 288 | 40 | 4.92 | 4.94 |

| 2 | 15 | 324 | 60 | 4.48 | 4.48 |

| 3 | 35 | 324 | 40 | 4.82 | 4.82 |

| 4 | 25 | 360 | 40 | 5.21 | 5.22 |

| 5 | 25 | 324 | 50 | 5.37 | 5.34 |

| 6 | 25 | 288 | 60 | 5.11 | 5.1 |

| 7 | 15 | 288 | 50 | 4.33 | 4.34 |

| 8 | 25 | 324 | 50 | 5.32 | 5.34 |

| 9 | 25 | 324 | 50 | 5.31 | 5.34 |

| 10 | 25 | 324 | 50 | 5.36 | 5.34 |

| 11 | 35 | 360 | 50 | 5.11 | 5.1 |

| 12 | 35 | 324 | 60 | 4.86 | 4.89 |

| 13 | 15 | 324 | 40 | 4.28 | 4.25 |

| 14 | 25 | 324 | 50 | 5.32 | 5.34 |

| 15 | 25 | 360 | 60 | 5.37 | 5.35 |

| 16 | 35 | 288 | 50 | 4.84 | 4.82 |

| 17 | 15 | 360 | 50 | 4.57 | 4.59 |

Yield (%) = 5.336 + 0.24625 * A + 0.1325 * B + 0.07375 * C + 0.0075 * AB − 0.04 * AC − 0.0075 * BC − 0.583 * A2 − 0.0405 * B2 − 0.143 * C2(8).

The results of statistical analysis of the model are shown in Table 3. F-value is used to detect the overall significance of the model. In this model the F-value was 260.84, which indicated that the model is significant. P-value is used to detect the significance of items, and items are considered significant when P-value is <0.05. Under this condition, the P-value of the model terms was <0.0001 indicating that the item is highly significant. Meanwhile, all primary terms were significant, while only AC was significant in the interaction term. The Lack of Fit F-value of 1.75 meant that it is not significant relative to the pure error. The value of the coefficient of variation (C.V.) was only 0.6239 %, which indicated that the experiment is well reproducible and the model is reliable. In addition, the coefficient of determination R2 is used to evaluate the quality of the model. When the value of R2is closer to 1, it indicates that the regression equation fits the observations better. The R2values and adjusted R2values in this model were 0.997 and 0.9932, respectively, which indicated that only 0.68 % of the total variance can not be explained by this model, so the model has a good goodness of fit. In summary, the model was established successfully and was statistically significant.

Table 3.

ANOVA of the response surface quadratic model of GBLPs yields.

| Source | Sum of Squares | Mean Square | F-value | P-value | Significanta |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 2.26 | 0.2513 | 260.84 | < 0.0001 | ☆☆ |

| A (Ratio of liquid to material) | 0.4851 | 0.4851 | 503.45 | < 0.0001 | ☆☆ |

| B (Ultrasonic power) | 0.1405 | 0.1405 | 145.76 | < 0.0001 | ☆☆ |

| C (Extraction time) | 0.0435 | 0.0435 | 45.16 | 0.0003 | ☆☆ |

| AB | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | 0.2335 | 0.6437 | – |

| AC | 0.0064 | 0.0064 | 6.64 | 0.0366 | ☆ |

| BC | 0.0002 | 0.0002 | 0.2335 | 0.6437 | – |

| A2 | 1.43 | 1.43 | 1485.22 | < 0.0001 | ☆☆ |

| B2 | 0.0069 | 0.0069 | 7.17 | 0.0317 | ☆ |

| C2 | 0.0861 | 0.0861 | 89.36 | < 0.0001 | ☆☆ |

| Residual | 0.0067 | 0.001 | |||

| Lack of Fit | 0.0038 | 0.0013 | 1.75 | 0.2956 | – |

| Pure Error | 0.0029 | 0.0007 | |||

| Cor Total | 2.27 | ||||

| R2 = 0.997 | |||||

| Adjusted R2 = 0.9932 | |||||

| C.V. = 0.6239 % |

☆☆: means highly significant (P < 0.001); ☆: means significant (P < 0.05); -: means not significant.

3.2.2. Confirmation of optimal conditions

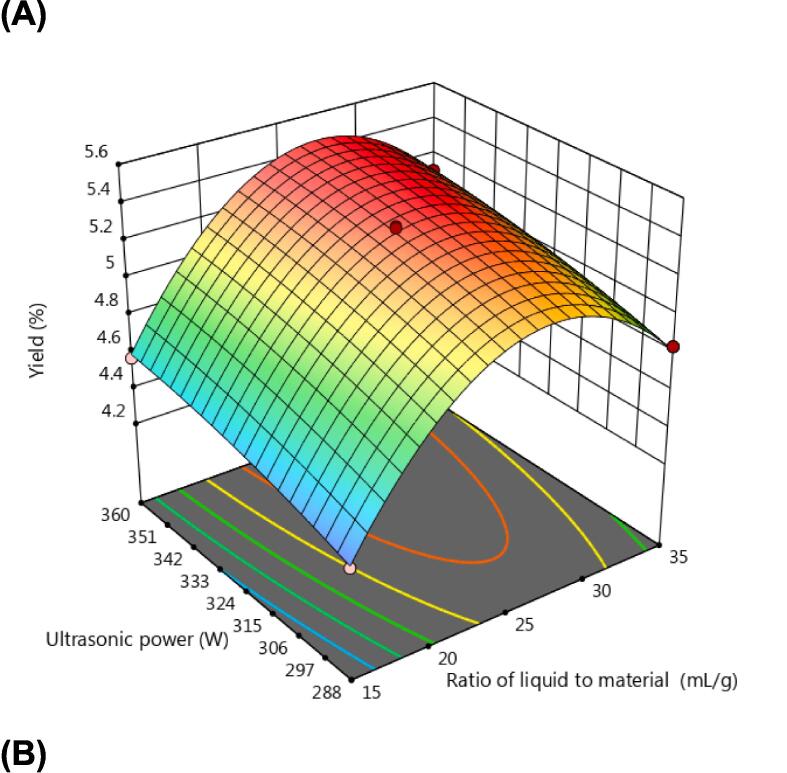

The response surface of Three-dimension (3D) can be used to evaluate the interaction between the two factors. As shown in Fig. 2, Fig. 2B was relatively steep, which indicated that the interaction between liquid to material ratio and extraction time has a significant impact on yield of GBLPs. This was consistent with the results in Table 3. In addition, the color change rate of the contour line can reflect the significance of each factor on the response value. It is obvious that the liquid to material ratio had the greatest influence on the yield of GBLPs among the three factors. However, this is influenced by the selection of factor levels. In this model, factor A was selected 3 levels with a wide range, however, both factor B and factor C were selected at a narrower range for reasons such as equipment and efficiency. This resulted in a large difference in the significance of the response values for the different factors. Based on the response surface analysis, the optimal extraction conditions were obtained as follows: liquid to material ratio of 28.449 mL/g, ultrasonic power of 336.85 W, extraction time of 51.51 min, and the predicted value of yield of 5.4 % under these conditions.

Fig. 2.

Three-dimensional response surface analysis: (A) Interaction between ratio of liquid to material and ultrasonic power; (B) Interaction between ratio of liquid to material and extraction time; (C) Interaction between ultrasonic power and extraction time.

3.2.3. Verification of optimal conditions

In order to investigate the adequacy of the model, the optimal conditions predicted by the model would be selected for the experiments. The experimental conditions would be slightly modified for the convenience of the experiments: liquid to material ratio of 30 mL/g, ultrasonic power of 340 W, and extraction time of 50 min. The experiments were carried out three times, and the average yield of GBLPs was 5.37 % under these conditions, which was in good agreement with the predicted value. Therefore, the model is adequate and accurate.

3.3. Analysis of chemical modifications

CM-GBLPs was obtained by reaction using chloroacetic acid as the carboxymethylation reagent, which is based on the principle of using alkali to alkalize the polysaccharide and then using the electrophilic nature of chloroacetic acid for the etherification reaction. The yield of CM-GBLPs was 89.5 %. Its sugar content measured by phenol-sulfuric acid method was 49.6 % <72.5 % of GBLPs, which is similar to the conclusion of Wang et al [18]. The reaction in acidic and medium temperature conditions caused the hydrolysis of some polysaccharides, so the sugar content decreased. The degree of substitution of CM-GBLPs calculated by the formula was 0.72, which is a high degree of substitution, and it is related to the amount of carboxymethylation reagent, reaction temperature, reaction time and other factors.

The yield of Ac-GBLPs prepared by acetic anhydride method was 58.8 %, which is lower than the result of Xie et al [19]. The sugar content of Ac-GBLPs was 55.2 %, which is slightly lower than that of GBLPs, but higher than that of CM-GBLPs. The acetylation reaction is a nucleophilic substitution reaction, and the reaction process is more sensitive to the pH value, so the pH value needs to be controlled between 9 and 10 to maintain an alkaline environment. The stability of the pH value has a large effect on the yield and polysaccharide content. The acetylation degree of substitution calculated by the formula was 0.35, which is in a more reasonable range [17].

3.4. Analysis of solubility

Macromolecular polysaccharides are almost insoluble in organic solutions, and some polysaccharides have a certain solubility in water. Solubility is an important index to evaluate the application value of polysaccharides, so the solubility of three polysaccharides was evaluated by dissolution rate and maximum dissolution amount. As shown in Fig. 3, the dissolution rate of the three polysaccharides was gradually accelerated with the increase of temperature, and the fastest growth rate was found in the range from room temperature to 40 ℃. The dissolution rate of CM-GBLPs was not much different from that of GBLPs at lower temperatures, but it was faster than GBLPs at higher temperatures, while Ac-GBLPs dissolved faster at all temperatures compared to GBLPs. The maximum solubilities of GBLPs, Ac-GBLPs, and CM-GBLPs calculated according to the method of 2.8 were 39.87 %, 61.13 %, and 44.22 %, respectively. The mechanism by which chemical modification enhances the solubility of polysaccharides is thought to be that the modification group changes the spatial structure of the polysaccharide, causing the aggregated polysaccharide molecules to stretch more, which results in the exposure of more hydrophilic hydroxyl groups [9]. It is obvious that Ac-GBLPs and CM-GBLPs showed not only an improvement in the dissolution rate but also a substantial increase in the maximum solubility. This is also consistent with what has been reported [20]. In addition, different degrees of substitution can have different effects on polysaccharide solubility, and Kurita et al. concluded that an acetylation degree of substitution between 0.4 and 0.6 is most favorable for increasing solubility [12]. The solubility of Ac-GBLPs was greater than that of CM-GBLPs, which may be due to the difference in substitution.

Fig. 3.

Dissolution rate of three polysaccharides.

3.5. Analysis of infrared spectroscopy

Infrared spectroscopy was used to identify the functional groups and specific structures present in the polysaccharides, and the results of the infrared spectroscopic identification of the three polysaccharides are shown in Fig. 4. The broad peak at 3297 cm−1 was attributed to the O—H bond stretching vibration of the hydroxyl group on the sugar ring of GBLPs, and the smaller peak near it at 2923 cm−1 was attributed to the C—H bond stretching vibration of the methyl and methylene groups of GBLPs. The peaks at 1603 cm−1 and 1411 cm−1 were attributed to the stretching vibration of the carboxyl group, which indicated the possible presence of uronic acid in GBLPs. The peak present at 1025 cm−1 in the fingerprint region was attributed to the asymmetric stretching vibration of the C—O—C bond, which is the characteristic peak of the pyranose ring [13]. Compared with GBLPs, Ac-GBLPs showed a new peak at 1180 cm−1, which is the characteristic peak of the ester group, and it was caused by the stretching vibration of the C—O bond of the acetyl group [19]. In addition, the peak intensity of the peak at 1626 cm−1 became stronger, which was caused by the stretching vibration of C O in the acetyl group. These changes proved that the acetylation of the polysaccharide was successful. In the Infrared spectroscopy of CM-GBLPs, the peaks at 1588 cm−1, 1415 cm−1, and 1325 cm−1 were attributed to the stretching vibration of the C O bond, the symmetric stretching vibration of the –COO bond, and the variable angle vibration of the –CH- bond, respectively. They are characteristic absorption peaks of carboxymethyl. These characteristics indicated that the carboxymethylation of polysaccharide was successful. It is noteworthy that the chemically modified polysaccharides showed a change in peak shape and chemical shift in the characteristic absorption peak region of the hydroxyl group around 3300 cm−1, indicating that the chemical modification had changed the number and association degree of the hydroxyl group. Besides, in most other regions, the three polysaccharides had similar peak patterns, which proved that the chemical modification did not change the main structure of the polysaccharide.

Fig. 4.

Infrared spectroscopy of three polysaccharides.

3.6. Analysis of NMR

Three polysaccharides were evaluated by NMR analysis. As shown in Fig. 5A, the anomeric carbon signals of GBLPs were concentrated in the region from 95 to 110 ppm. There were five more obvious signals in this region, which reflected that GBLPs has a complex glycosidic bond linkage. The region between δ 50 and δ 90 is the distribution region of the C2 to C6 signals of monosaccharide residues. The signals at around δ 60 were attributed to the C6 signal of the hexose. The strong peak at δ 16.78 in the high field region was attributed to the signal of the primary carbon, which indicated the presence of deoxygenated sugar residues in the structure of GBLPs. Based on previous studies, this signal was inferred to be the C6 signal of rhamnose [13]. In the low-field region, the presence of δ 175.19 indicated the presence of acidic groups in the structure of GBLPs, which is consistent with the results of infrared spectroscopy. Compared with the 13C NMR of GBLPs, Ac-GBLPs increased two signals at δ 173.00 and δ 170.27 in the low-field region (Fig. 5B), which were attributed to the acyl carbon of the acetyl group. At the same time, the signal of δ 21.06 was increased in the high-field region, which comes from the primary carbon and was attributed to the signal of the methyl carbon atom on the acetyl group [5]. The de-shielding effect of the carbonyl group makes it shift to lower fields compared to the normal methyl carbon signal. In addition to these changes, most of the signals in the region from 55 to 110 ppm were chemically shifted due to the introduction of acetyl groups. Looking at the signals in this region as a whole, it was clear that the signal of Ac-GBLPs overlapped more severely compared to that of GBLPs. This may be caused by two reasons. On the one hand, the introduction of the acetyl group as an electron-withdrawing group weakened the electron-withdrawing effect of the hydroxyl group, which indirectly leaded to the narrowing of the chemical shift gap between carbon atoms. On the other hand, as discussed in 3.4, the stretching of polysaccharides by acetylation weakened the effect of spatial effects on chemical shifts. Similarly, these changes were also reflected in the 13C NMR of CM-GBLPs, which had a much stronger signal overlap in this region than the acetylated polysaccharide. At the same time, two new characteristic signals at δ 177.32 and δ 178.69 appeared in the 13C NMR of CM-GBLPs due to the introduction of the carboxymethyl group, and this result was similar to that obtained by Yang et al [22]. In addition, chemical shifts are used to determine the derivatization site, but this only applies to structurally simple polysaccharides. Even so, it is still possible to get some useful information from it. The signals of the chemically modified polysaccharides around δ 60 were significantly displaced. As inferred above, this region was mainly attributed to the C6 signals of monosaccharide residues, which implied that C6 is an important chemical modification site. This is reasonable in terms of chemical structure because C6 carbon has a smaller rigidity and larger spatial extent than carbon at other positions. Of course, the chemical shift of the signals in the range of 65 to 90 ppm also suggested that the chemical modification occurred at other sites at the same time. In conclusion, the NMR analysis once again demonstrated that the two chemical modifications were successful.

Fig. 5.

13C NMR spectra: (A) GBLPs; (B) Ac-GBLPs; (C) CM-GBLPs.

3.7. In vitro antioxidant activity analysis

3.7.1. Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity

The hydroxyl radical scavenging activity of three polysaccharides was tested by Fenton reaction system. Hydroxyl radical is a kind of highly oxidizing reactive oxygen species, which has attracted wide attention because of its correlation with aging and the pathology of certain diseases in the human body [1]. Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity is one of the most commonly used indexes to evaluate antioxidant activity in vitro. As shown in Fig. 6A, there was a significant positive correlation between the polysaccharide concentration and the scavenging rate. When the concentration of GBLPs reached 2 mg/mL, the scavenging rate basically reached its maximum value, which was not very satisfactory. Hydroxyl radical scavenging ability is related to the properties of the material itself, which is influenced by various factors such as solubility, molecular weight, and spatial structure of the material. Similar hydroxyl radical scavenging activity had also been found in previous literature for polysaccharides from Ginkgo biloba leaves [16]. The hydroxyl radical scavenging activities of the chemically modified polysaccharides were significantly improved at most concentrations, and the effect of carboxymethylation modification was more significant. CM-GBLPs reached half the scavenging rate of the positive control at a concentration of 4 mg/mL. At the same time, it should be noted that the scavenging rate of Ac-GBLPs and CM-GBLPs still tended to increase when they reached their maximum concentration, which is different from GBLPs. Possible reasons for the ability of chemical modifications to enhance hydroxyl radical scavenging were considered to be two points. One is that the introduction of the modification group enhances the hydrogen donating capacity of the polysaccharide, leading to the enhancement of the activity [19]. Although this point had been demonstrated in most studies, the different derivatizations showed large differences. In this respect, phosphorylation modifications tended to be more prominent [13]. Second, the introduction of the modification group changes the spatial structure of polysaccharide, resulting in more reaction sites exposed [25]. This was mentioned in the discussion of solubility. Based on this, some seemingly complex conclusions are well explained. For example, different chemical modification sites have different effects on anti-oxidative activity, which may be caused by the different benefits of different chemical modification sites on enhancing hydrogen supply capacity. The effect of different degrees of substitution on antioxidant activity may be attributed to the second reason mentioned above. In this experiment, CM-GBLPs exhibited superior hydroxyl radical scavenging activity to Ac-GBLPs. However, in the solubility experiment, Ac-GBLPs showed better solubility than CM-GBLPs, indicating that the acetylation modified polysaccharide had more hydrophilic hydroxyl groups exposed. Therefore, the first mechanism played a decisive role in this experiment. Overall, both carboxymethylation modification and acetylation modification were effective in enhancing the hydroxyl radical scavenging activity of GBLPs.

Fig. 6.

Antioxidant activity in vitro: (A) Hydroxyl radical scavenging rate; (B) DPPH radical scavenging rate; (C) lipid peroxidation scavenging rate.

3.7.2. DPPH radical scavenging activity

The scavenging ability of the three polysaccharides on DPPH radicals is shown in Fig. 6B. On the whole, the scavenging activity of these polysaccharides for DPPH radicals was extremely low compared to the positive control. Locally, acetylation showed a greater enhancement of the DPPH radical scavenging ability of GBLPs. This boost still tends to increase at the maximum concentration. This implied that greater DPPH radical scavenging activity can be obtained by increasing the concentration of Ac-GBLPs. In contrast, the enhancement of DPPH radical scavenging ability by carboxymethylation was very limited, and its scavenging activity basically reached the maximum at a concentration of 2 mg/L. DPPH radical is a relatively stable free radical, and it is generally believed that polysaccharides achieve its scavenging in a form of single electron transfer [23]. Under this mechanism, polysaccharides are required to have strong electron donating ability, so GBLPs is not a good electron donor, but acetylation modification can effectively improve the electron donating ability of polysaccharides. In conclusion, acetylation has the ability to enhance the DPPH scavenging activity of polysaccharides to a certain extent, but it is limited by the poor DPPH radical scavenging ability of GBLPs itself and does not have a promising application in this regard.

3.7.3. Anti-lipid peroxidation ability

The anti-lipid peroxidation ability of the three polysaccharides was tested using lipid peroxidation induced by soy lecithin. Lipid peroxidation refers to the oxidative degradation of polyunsaturated fatty acids and lipids, which is an oxidation that is harmful to the human body. During this process, a large number of different free radicals are generated, and polysaccharides indirectly act against lipid peroxidation by inhibiting these free radicals. As shown in Fig. 6C, in this system, the activity of the polysaccharide modified by acetylation and carboxymethylation was improved to a certain extent at all concentrations. The activity grew faster with increasing concentration before the concentration of 2 mg/L, and the activity growth leveled off after 2 mg/L. However, there was still a gap compared to the positive control. Notably, the enhancement of antioxidant activity of GBLPs by acetylation modification and carboxymethylation modification did not remain consistent in the three in vitro antioxidant experiments. This may be due to the fact that different in vitro antioxidant experiments have different reaction mechanisms, while different chemical modifications have different effects on the properties of the same polysaccharide. In addition, from the above discussion, it can be seen that the factors affecting the antioxidant activity of chemically modified polysaccharides are various, and the previous studies also showed uneven levels [21]. Therefore, we conclude that chemical modification has some ability to enhance the antioxidant activity of polysaccharides, but for the extent of enhancement is not controllable. It is related to various factors such as the degree of substitution of chemical modification, substitution sites, substituent groups and the reaction mechanism of the antioxidant experiment itself. This needs to be supported by more accurate and complete data.

4. Conclusion

In summary, the conditions of ultrasound-assisted extraction of GBLPs were optimized by RSM. The optimum yield of GBLPs was 5.37 % at a liquid to material ratio of 30 mL/g, an ultrasonic power of 340 W and an extraction time of 50 min. CM-GBLPs with a substitution degree of 0.72 and Ac-GBLPs with a substitution degree of 0.35 were obtained by carboxymethylation and acetylation of the polysaccharide extracted from Ginkgo biloba leaves. The solubility analysis showed that the chemical modification could effectively improve the solubility of polysaccharides, with a better effect of acetylation. Infrared spectroscopy and NMR analysis proved that the chemical modification was successful and revealed some structural features of acetylation and carboxymethylation. In vitro antioxidant experiments showed that acetylation modification could effectively improve the hydroxyl radical, DPPH radical and lipid peroxidation scavenging ability of polysaccharides, while carboxymethylation modification could only effectively improve the hydroxyl radical and lipid peroxidation scavenging ability.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Contributor Information

Gangliang Huang, Email: huangdoctor226@163.com.

Hualiang Huang, Email: hlhuang@wit.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Blakeborough M., Owen R., Bilton R. Free radical generating mechanisms in the colon: their role in the induction and promotion of colorectal cancer? Free Radical Research Communications. 1989;6(6):359–367. doi: 10.3109/10715768909087919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen F., Huang G., Yang Z., Hou Y. Antioxidant activity of Momordica charantia polysaccharide and its derivatives. International journal of biological macromolecules. 2019;138:673–680. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.07.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen S., Huang H., Huang G. Extraction, derivatization and antioxidant activity of cucumber polysaccharide. International journal of biological macromolecules. 2019;140:1047–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.08.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cumpstey, I. (2013). Chemical modification of polysaccharides. International scholarly research notices. 2013.

- 5.Deng Y., Li M., Chen L.-X., Chen X.-Q., Lu J.-H., Zhao J., Li S.-P. Chemical characterization and immunomodulatory activity of acetylated polysaccharides from Dendrobium devonianum. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2018;180:238–245. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duan S., Zhao M., Wu B., Wang S., Yang Y., Xu Y., Wang L. Preparation, characteristics, and antioxidant activities of carboxymethylated polysaccharides from blackcurrant fruits. International journal of biological macromolecules. 2020;155:1114–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.11.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dubois M., Gilles K.A., Hamilton J.K., Rebers P.t., Smith F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Analytical chemistry. 1956;28(3):350–356. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ebringerová A., Hromádková Z. An overview on the application of ultrasound in extraction, separation and purification of plant polysaccharides. Central European Journal of Chemistry. 2010;8(2):243–257. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo M.Q., Hu X., Wang C., Ai L. Polysaccharides: structure and solubility. Solubility of polysaccharides. 2017;2:8–21. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang H., Huang G. Extraction, separation, modification, structural characterization, and antioxidant activity of plant polysaccharides. Chemical biology & drug design. 2020;96(5):1209–1222. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.13794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kong L., Yu L., Feng T., Yin X., Liu T., Dong L. Physicochemical characterization of the polysaccharide from Bletilla striata: Effect of drying method. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2015;125:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurita K., Kamiya M., Nishimura S.-I. Solubilization of a rigid polysaccharide: controlled partial N-acetylation of chitosan to develop solubility. Carbohydrate Polymers. 1991;16(1):83–92. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li J., Shi H., Yu J., Lei Y., Huang G., Huang H. Extraction and properties of Ginkgo biloba leaf polysaccharide and its phosphorylated derivative. Industrial Crops and Products. 2022;189 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu D., Sheng J., Li Z., Qi H., Sun Y., Duan Y., Zhang W. Antioxidant activity of polysaccharide fractions extracted from Athyrium multidentatum (Doll.) Ching. International journal of biological macromolecules. 2013;56:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2013.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu L., Wang Y., Zhang J., Wang S. Advances in the chemical constituents and chemical analysis of Ginkgo biloba leaf, extract, and phytopharmaceuticals. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 2021;193 doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2020.113704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ren Q., Chen J., Ding Y., Cheng J., Yang S., Ding Z., Dai Q., Ding Z. In vitro antioxidant and immunostimulating activities of polysaccharides from Ginkgo biloba leaves. International journal of biological macromolecules. 2019;124:972–980. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.11.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song Y., Yang Y., Zhang Y., Duan L., Zhou C., Ni Y., Liao X., Li Q., Hu X. Effect of acetylation on antioxidant and cytoprotective activity of polysaccharides isolated from pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo, lady godiva) Carbohydrate Polymers. 2013;98(1):686–691. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.06.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Z.-J., Xie J.-H., Shen M.-Y., Tang W., Wang H., Nie S.-P., Xie M.-Y. Carboxymethylation of polysaccharide from Cyclocarya paliurus and their characterization and antioxidant properties evaluation. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2016;136:988–994. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xie J.-H., Zhang F., Wang Z.-J., Shen M.-Y., Nie S.-P., Xie M.-Y. Preparation, characterization and antioxidant activities of acetylated polysaccharides from Cyclocarya paliurus leaves. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2015;133:596–604. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu J., Liu W., Yao W., Pang X., Yin D., Gao X. Carboxymethylation of a polysaccharide extracted from Ganoderma lucidum enhances its antioxidant activities in vitro. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2009;78(2):227–234. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu Y., Wu Y.-J., Sun P.-L., Zhang F.-M., Linhardt R.J., Zhang A.-Q. Chemically modified polysaccharides: Synthesis, characterization, structure activity relationships of action. International journal of biological macromolecules. 2019;132:970–977. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.03.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang L., Zhao T., Wei H., Zhang M., Zou Y., Mao G., Wu X. Carboxymethylation of polysaccharides from Auricularia auricula and their antioxidant activities in vitro. International journal of biological macromolecules. 2011;49(5):1124–1130. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yarley O.P.N., Kojo A.B., Zhou C., Yu X., Gideon A., Kwadwo H.H., Richard O. Reviews on mechanisms of in vitro antioxidant, antibacterial and anticancer activities of water-soluble plant polysaccharides. International journal of biological macromolecules. 2021;183:2262–2271. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.05.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yin D., Sun X., Li N., Guo Y., Tian Y., Wang L. Structural properties and antioxidant activity of polysaccharides extracted from Laminaria japonica using various methods. Process Biochemistry. 2021;111:201–209. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Z., Wang X., Zhao M., Qi H. O-acetylation of low-molecular-weight polysaccharide from Enteromorpha linza with antioxidant activity. International journal of biological macromolecules. 2014;69:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.04.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng Q., Ren D., Yang N., Yang X. Optimization for ultrasound-assisted extraction of polysaccharides with chemical composition and antioxidant activity from the Artemisia sphaerocephala Krasch seeds. International journal of biological macromolecules. 2016;91:856–866. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2016.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu C.-P., Zhai X.-C., Li L.-Q., Wu X.-X., Li B. Response surface optimization of ultrasound-assisted polysaccharides extraction from pomegranate peel. Food Chemistry. 2015;177:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin B., Huang G. An important polysaccharide from fermentum. Food Chemistry: X. 2022;15 doi: 10.1016/j.fochx.2022.100388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li B., Huang G. Preparation, structure-function relationship and application of Grifola umbellate polysaccharides. Industrial Crops and Products. 2022;186 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou S., Huang G., Huang H. Extraction, derivatization and antioxidant activities of onion polysaccharide. Food Chemistry. 2022;388 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.133000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang Z., Huang G. Extraction, structure, and activity of polysaccharide from Radix astragali. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy. 2022;150 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin B., Huang G. Extraction, isolation, purification, derivatization, bioactivity, structure-activity relationship, and application of polysaccharides from White jellyfungus. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 2022;119(6):1359–1379. doi: 10.1002/bit.28064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tang Q., Huang G. Improving method, properties and application of polysaccharide as emulsifier. Food Chemistry. 2022;376 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li J., Fan Y., Huang G., Huang H. Extraction, structural characteristics and activities of Zizylphus vulgaris polysaccharides. Industrial Crops and Products. 2022;178 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou S., Huang G. Extraction, derivatization, and antioxidant activity of Morinda citrifolia polysaccharide. Chemical Biology and Drug Design. 2022;99(4):603–608. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.14023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang W., Yang Z., Zou Y., Sun X., Huang G. Extraction and deproteinization process of polysaccharide from purple sweet potato. Chemical Biology and Drug Design. 2022;99(1):111–117. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.13935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fan Y., Zhou X., Huang G. Preparation, structure, and properties of tea polysaccharide. Chemical Biology and Drug Design. 2022;99(1):75–82. doi: 10.1111/cbdd.13924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang W., Huang G. Preparation, structural characteristics, and application of taro polysaccharides in food. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2022;102:6193–6201. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.12058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou S., Huang G. Extraction, structural analysis and antioxidant activity of aloe polysaccharide. Journal of Molecular Structure. 2023;1273 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mei X., Tang Q., Huang G., Long R., Huang H. Preparation, structural analysis and antioxidant activities of phosphorylated (1→3)-β-d-glucan. Food Chem. 2020;309 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Benchamas G., Huang G., Huang S., Huang H. Preparation and biological activities of chitosan oligosaccharides. Trends in Food Science and Technology. 2021;107:38–44. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen F., Huang G., Huang H. Preparation, analysis, antioxidant activities in vivo of phosphorylated polysaccharide from Momordica charantia. Carbohydrate Polymers. 2021;252 doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.117179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang G., Chen F., Yang W., Huang H. Preparation, deproteinization and comparison of bioactive polysaccharides. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021;109:564–568. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu Y., Huang G. Extraction and derivatisation of active polysaccharides. Journal of Enzyme Inhibition and Medicinal Chemistry. 2019;34(1):1690–1696. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2019.1660654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang W., Huang G. Extraction methods and activities of natural glucans. Trends in Food Science and Technology. 2021;112:50–57. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang W., Huang G., Chen F., Huang H. Extraction/synthesis and biological activities of selenopolysaccharide. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021;109:211–218. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou S., Huang G. Preparation, structure and activity of polysaccharide phosphate esters. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2021;144 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou S., Huang G., Chen G. Extraction, structural analysis, derivatization and antioxidant activity of polysaccharide from Chinese yam. Food Chemistry. 2021;361 doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.130089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou S., Jiang W., Chen G., Huang G. Design and synthesis of novel double-ring conjugated enones as potent anti-rheumatoid arthritis agents. ACS Omega. 2022;7(48):44065–44077. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.2c05492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]