Abstract

Background

Cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy treatment, have a higher risk to foodborne infections as compared to other populations. Oncology nurses, having a direct significant contact with these patients, could be the first information source concerning food safety and play a pivotal role in reducing these risks.

Objective

This study aims to assess the level of knowledge regarding food safety among oncology nurses, as well as their attitudes and practices in private hospitals in Lebanon.

Methods

A self-administered questionnaire was filled by Oncology nurses (n = 134) working in eighteen private hospitals in Lebanon located in Mount Lebanon (n = 11) and Beirut (n = 7).

Results

Overall, oncology nurses scored 76%, 95%, 86.9% and 83.4% on the knowledge, attitude, and practices questions, and overall composite knowledge, attitude, practices (KAP) score, respectively. Knowledge scores were higher among nurses holding a graduate degree (mean = 85; p < 0.05), and those who attended a training course (mean = 79; p < 0.05). Attitude scores of nurses who read brochures were higher (p < 0.001). Attending conferences on food safety showed statistically significant effect on better practice scores (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Accordingly, the findings highlight the need to develop standardized food safety curriculum and training necessary to allow oncology nurses to contribute to the education of cancer patients and decrease their risk of foodborne infection.

Keywords: Attitudes, Cancer patients, Food safety, Knowledge, Oncology nurses, Practices

1. Introduction

Cancer is the main reason behind the number of deaths across the world, with an estimate of 1,762,450 new cancer diagnosed and 606,880 patient dead in 2019 [1]. Chemotherapy is a common treatment for cancer. It uses cytotoxic drugs that decrease the lymphocytes’ count, inducing immunosuppression [2]. These patients suffering from severe neutropenia (the count of neutrophil cells in blood is ≤ 1000 cells/μL [3] are highly prone to infections, including foodborne diseases [4,5].

A scope of foodborne infections, such as listeriosis, salmonellosis, campylobacteriosis, and toxoplasmosis were determined to be more common among cancerous patients as compared to healthy individuals [6]. Cancer patients are very susceptible to Saccharomyces cerevisiae, toxoplasma gondii, due to immunosuppression and they experience highly aggressive infection by Eschericha coli [[7], [8], [9]]. This leads to a higher mortality rate since the treatment of these opportunistic pathogens is very difficult and lengthy due to patients’ low immunity [6]. According to the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention people with weakened immune systems are more likely to have a lengthier illness, undergo hospitalization, or even die as a result of foodborne disease [10].

Patients with gynecological cancer are at 66-times greater risk for infection by Listeria monocytogenes than healthy people, while those with blood cancer are 1364-times more susceptibilty to infection [11]. Salmonella and Campylobacter cause infections in the gastrointestinal tract in patients with hematological malignancies more than people without a malignancy [12].

Cancer and chemotherapy treatment were the most commonly reported morbidities among the non-pregnancy-associated cases of listeriosis in the United States [13]. Furthermore, in the United Kingdom, cancer was the most frequent cause behind recorded cases of listeriosis (26%) in 2014 [14]. Moreover, research estimated that an elevation of listeriosis occurrence in cancerous people has been reported in the United Kingdom between 1999 and 2009. These patients were shown to have a five-fold high risk of listeriosis [6].

Consuming undercooked meat, unpasteurized milk, raw oysters, contaminated veggies, and having any contact with infected cat feces, or environmental contamination, are all sources of infection from these pathogens [15]. These patients are recommended to follow a neutropenic diet, that is known to restrict certain types of foods (fresh fruits and vegetables, raw or undercooked meat and poultry …) to decrease the frequency of bacterial translocation from the gut to the bloodstream, hence lowering the likelihood of having a foodborne infection [6].

Food handling and preparation measures at every step in the food supply chain process and especially in healthcare facilities, are critical for the prevention of foodborne pathogens. This highlights the significant role of caregivers including physicians, nurses and dietitians, in providing safety guidelines to cancer patients [16]. According to the literature, it is suggested that if cancer patients were being provided with more awareness and better understanding of recommended practices, they might be more likely to tolerate food safety guidance [6]. Moreover, studies found that patients with cancer showed positive behavior towards getting food safety education and are seemingly willing to adhere to the recommendations; nevertheless, these patients need to get proper food safety information from sources known to be credible and reliable [6,17].

The corona virus outbreak has made people pay more attention to food safety. For example, Chinese medical caregivers became more aware after the pandemic about food safety toward their patients, especially the immunocompromised ones infected with Covid-19 [18].

Medical professionals have an impact on the public, which makes them capable of making people understand food safety and paying it more attention. Moreover, their role is not only limited to public influence, they can also enhance the understanding of food safety in their work settings, consequently leading to protecting the health of the public in general [18].

All healthcare providers, especially those working with highly susceptible individuals, particularly targeting immunocompromised populations must educate their patients concerning their high vulnerability to infections and teach them how to protect themselves against foodborne pathogens [19]. Two main categories of healthcare providers-registered nurses and registered dietitians-were shown to play a significant role in providing adequate and reliable information regarding food safety to high-risk patients [17]. For example, it was reported that after the corona virus pandemic, medical professionals showed an increased readiness to give food safety advices compared to before the outbreak and they approved that patients consider them a reliable source for food safety education [18]. Registered dietitians were more likely to have attended training courses regarding food safety as compared to registered nurses (85% and 28%, respectively). However, nurses are the main provider of information to patients [19]. Nursing service is 24/7 in hospitals and nurses are considered to be the only caregivers to have a direct contact with the patients at all times, and at each mealtime. Thus, they have an essential role in providing the patients’ nutritional care and monitoring their meal experience [20].

Worldwide, few studies were conducted to assess the food safety knowledge, attitudes, and practices among nurses; including one in China [18], one in South Africa [21], one in Nigeria [22] and another one in Italy [23]. These studies recruited general nurses serving in different wards. To the best of our knowledge, no study had addressed specialized nurses and those working with the most vulnerable patients. Therefore, the objective of the current study was to assess the food safety knowledge, attitudes and practices of oncology nurses working in Lebanese hospitals located in Beirut and Mount Lebanon. This study also aims to identify the awareness of oncology nurses regarding their role in reducing the risk of foodborne infection among chemotherapy patients.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Study design

A cross-sectional study between July and October 2019 was conducted recruiting oncology nurses working in Lebanese hospitals located in Mount Lebanon and Beirut. Most hospitals in Lebanon were located in this area and the remaining hospitals outside this geographical area were excluded from this study. Forty-nine hospitals were originally contacted, out of which 26 did not meet the eligibility criteria of having specialized oncology nurses that are involved in administering chemotherapy treatment for cancer patients. Among the eligible ones, 5 did not accept to be part of the study and 18 accepted and were recruited. The number of registered oncology nurses were determined by the nursing director of each hospital. All nurses in the department of oncology were requested to participate in the study. After the hospitals ‘approval, the self-administered questionnaires were distributed in total to 134 oncology nurses accounting for 100% response.

2.2. Questionnaire and data collection

A questionnaire was used for data collection. The questionnaire was a ready to use (Supplementary material S1) set of questions with a clear answer evaluation, adapted from [22–24]. It included mostly multiple-choice questions and some open-ended questions. It comprised seven sections covering: 1) socio-demographic characteristics; 2) employment status and the type of hospital where they work; 3) knowledge on types of food for patients under chemotherapy based on the Food Safety During and After Cancer Treatment [25]; 4) general food safety knowledge about food hygiene, storage time and temperature conditions, pathogens and foodborne illnesses (12 questions); 5) attitudes regarding prevention of foodborne diseases (8 questions); 6) food safety practices used to prevent foodborne diseases (9 questions); (7) questions addressing opinion of oncology nurses regarding food safety trainings. Questions on knowledge had answers including yes/no/I don't know some others were multiple choice questions or open-ended questions. The percentage of correct answers were pooled against the incorrect ones which also included the “don't know” responses. The questions about attitude had yes/often/no as answers they were also segregated as correct and incorrect. The questions related to the behavior had always, often, rarely and never as answers. The questionnaire was in English, translated into Arabic and back translated into English. It was piloted on 5 oncology nurses in order to assess its length and check for any incongruences or unclear questions. The questionnaire was distributed to all targeted healthcare professionals working in oncology units, after getting the approval from each hospital.

2.3. Ethical considerations

The data collection took place after the NDU-IRB approval (Ref #: IRBSP2019_7_FNHS). Before the study was conducted, permission was asked from the hospitals to participate in the research. The study participants were informed about the research objectives and their consent was obtained in order to fill the questionnaire. Anonymity and confidentiality were guaranteed.

2.4. Plan for analysis

After the data collection, all the questionnaires were recoded and interpreted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25 (IBM, Inc, Chicago, IL). Qualitative variables were presented by frequencies and percentages, while quantitative variables were displayed by means and standard deviations. Each category had its responses frequency and percentages computed and organized. Independent sample t-test, ANOVA and correlation (confidence interval 95%) were applied to compare selected test variables such as gender, age, education level and work experience with selected questions about knowledge, attitudes and practices. Age was recategorized into 4 separate classes similar to the ones defined by Ref. [22]. Each question answered correctly was attributed a one-point score and each incorrect answer, “I don't know”, “Uncertain”, “Often” answers were attributed a null score. The KAP scores were classified as poor (less than and equal to 50%), fair (51–79%) and good (80% and above) [26]. Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Sample characteristics

Socio-demographic characteristics of oncology nurses in Lebanese hospitals are presented in Table 1. The mean age of the recruited oncology nurses (n = 134) was equal to 30 ± 8 years old, 84% were females, 58% were married, 83% had a bachelor in nursing, and 55% had a work experience less than 5 years.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics of the socio-demographic characteristics of the oncology nurses (n = 134).

| Socio-demographic characteristics | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | 22 | 16.0 |

| Male | 111 | 84.0 |

| Female | ||

| Age (in years) Mean ± SDa [20–30] | 30 ± 8 | 57.0 |

| [31–40] | 77 | 31.0 |

| [41–50] | 41 | 6.0 |

| >50 | 8 | 6.0 |

| 8 | ||

| Marital Status | ||

| Single | 56 | 42.0 |

| Ever married (married, divorced, widowed) | 77 | 58.0 |

| Level of Education | ||

| Technical degree | 8 | 6.0 |

| Bachelor in Nursing | 108 | 83.0 |

| Graduate degree: Master's or Doctorate degree | 14 | 11.0 |

| Years of Experience (in years) | 68 | 55.0 |

| <5 [5–10] | 34 | 27.0 |

| >10 | 22 | 18.0 |

| Attending a course on food safety for chemotherapy patients | ||

| No | 75 | 56.0 |

| Yes | 58 | 44.0 |

| Sources of information about food safetyb | ||

| Media | 47 | 36.0 |

| TV | 26 | 20.0 |

| Audio | 6 | 5.0 |

| Brochures | 62 | 47.0 |

| Conferences | 97 | 74.0 |

SD = Standard Deviation.

The total is not 134 because participants can select more than one answer.

3.2. Nurses’ knowledge on neutropenic diet

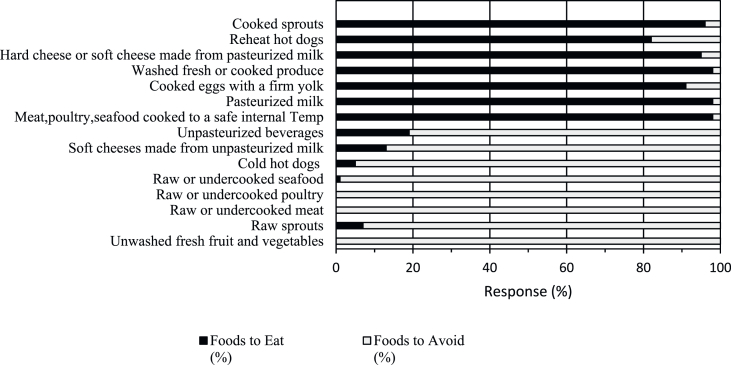

All the nurses (100%) agreed that unwashed fresh fruits and vegetables as well as raw or undercooked food should be avoided by cancer patients especially those undergoing chemotherapy treatment. Most of them agreed that food should be heat treated and washed before consumption. However, 19% and 13% of nurses misstated respectively that soft cheeses and unpasteurized beverages should be avoided (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Type of foods recommended to consume or to avoid for cancer patients (n = 134).

Among the participants, only 44% attended a course on food safety for chemotherapy patients and 74% relied on conferences as a source of information about food safety, 47% relied on brochures, 36% on media, 20% on TV, and 5% on Audio.

3.3. Food safety knowledge

The participants' mean knowledge score was 76 ± 12, ranging from 38 to 95 (Table 2). The findings showed that 74% of nurses were aware that the preparation of food in advance could contribute to food poisoning and that reheating food is likely to contribute to food contamination. Most of the participants (95% and 98%, respectively) acknowledged that inappropriate application of cleaning and sanitization methods on equipment can elevate the likelihood of foodborne infection, and that hand washing before handling food can reduce the risk of food contamination. Moreover, 78% of nurses agreed that wearing hand gloves while handling food reduces the risk of transmitting infection to patients' food. On the other hand, only 65% of nurses were aware about the right temperature for a refrigerator, while 65% and 64%, stated properly the storage temperature for hot and cold ready to eat foods, respectively. Concerning oncology nurses’ knowledge on foodborne diseases, their correct answers ranged from 72 to 82% to the related questions.

Table 2.

Knowledge of oncology nurses on food safety and hygiene (n = 134).

| Item | Description | Correct (%) | Incorrect (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4.1 | Preparation of food in advance is likely to contribute to food poisoning (Yes) | 99 (74.0) | 35 (26.0) |

| 4.2 | Reheating of food is likely to contribute to food contamination (Yes) | 99 (74.0) | 35 (26.0) |

| 4.3 | Incorrect application of cleaning/sanitizing procedures on equipment (refrigerator, slicing machine) can increase the risk of foodborne disease to inpatients (Yes) | 127 (95.0) | 7 (5.0) |

| 4.4 | Hand washing before handling food can reduce the risk of food contamination (Yes) | 131 (98.0) | 3 (2.0) |

| 4.5 | Wearing hand gloves while handling food reduces the risk of transmitting foodborne infection to patients' food (Yes) | 105 (78.0) | 29 (22.0) |

| 4.6 | The correct temperature for a refrigerator is (<5 °C) (Yes) | 87 (65.0) | 47 (35.0) |

| 4.7 | Hot ready to eat foods should be maintained at (>60 °C) (Yes) | 86 (64.0) | 48 (36.0) |

| 4.8 | Cold ready to eat foods should be maintained at (<5 °C) (Yes) | 80 (60.0) | 54 (40.0) |

| 4.9 | Hepatitis B can be transmitted by food (Yes) | 37 (28.0) | 97 (72.0) |

| 4.10 | Cholera can be transmitted by food (Yes) | 110 (82.0) | 24 (18.0) |

| 4.11 | Food items are associated to the transmission of Vibrio cholerae(Yes) | 98 (73.0) | 36 (27.0) |

| 4.12 | Food items are associated to the transmission of gastroenteritis (Yes) | 121 (90.0) | 13 (10.0) |

| Knowledge score | Mean ± SD | Min-Max | |

| 76 ± 12 | 38–95 | ||

3.4. Food safety attitudes

The participants’ mean attitude score was 95 ± 10 ranging from 50 to 100 (Table 3). Ninety-eight percent of nurses noted the necessity of checking the refrigerator/freezer operating conditions periodically, proper storage of foods, and washing hands at critical times in order to reduce food spoilage and health risks to patients. Ninety-six percent and 95% of nurses agreed respectively that wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) before handling food and separating cooked foods from raw ones may cause health hazard to consumers. Moreover, 92% of nurses believed that healthcare workers with respiratory/diarrhea diseases should be excluded from food handling until full recovery. Ninety percent of nurses agreed that “food-handler with abrasions or cuts on hands should not touch unwrapped food” and 89% stated that “defrosted foods should not be refrozen”.

Table 3.

Attitudes of oncology nurses on food safety and hygiene (n = 134).

| Item | Description | Correct (%) | Incorrect (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5.1 | Raw foods should be kept separated from cooked foods | 127 (95.0) | 7 (5.0) |

| 5.2 | Defrosted food should not be refrozen | 119 (89.0) | 15 (11.0) |

| 5.3 | It is necessary to check the refrigerator/freezer operating conditions periodically to reduce the risk of food spoilage | 132 (98.0) | 2 (2.0) |

| 5.4 | The risk of food contamination will reduce if we wear personal protective equipment before handling food | 129 (96.0) | 5 (4.0) |

| 5.5 | Improper storage of foods may cause health hazard to consumers | 131 (98.0) | 3 (2.0) |

| 5.6 | Hand washing at critical times contributes to food safety and hygiene | 132 (98.0) | 2 (2.0) |

| 5.7 | Nurses with respiratory/diarrhea diseases should be excluded from food handling until full recovery | 123 (92.0) | 11 (8.0) |

| 5.8 | Food-service staff with abrasions or cuts on hands should not touch unwrapped food | 121 (90.0) | 13 (10.0) |

| Attitude score | Mean ± SD | Min-Max | |

| 95 ± 10 | 50–100 | ||

3.5. Food safety practices

The participants’ mean practices score was 86.9 ± 15.2, with 33 and 100 as the minimum and maximum scores respectively (Table 4). The practice of handwashing among oncology nurses before and after handling unwrapped raw foods is 84% and 91%, respectively. While for cooked foods, the participants declared that they always wash their hands before and after touching food (84% and 86%, respectively). Sixty-five percent of nurses stated that they use separate kitchen utensils to prepare cooked and raw food. Out of the respondents, only 59% and 58% reported always checking the integrity of hospital wheeler-bin foods as well as the shelf-life before serving to patients, respectively. Furthermore, half of nurses mentioned that they always wear personal protective equipment before handling food. Finally, 45% of nurses stated that they always thaw frozen food at room temperature.

Table 4.

Practices of oncology nurses on food safety and hygiene (n = 134).

| Item | Description | Always (%) | Often (%) | Rarely (%) | Never (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6.1 | Do you wash your hands before touching unwrapped raw food? | 112 (84.0) | 15 (11.0) | 7 (5.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 6.2 | Do you wash your hands after touching unwrapped raw food? | 122 (91.0) | 9 (7.0) | 3 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 6.3 | Do you wash your hands before touching unwrapped cooked food? | 113 (84.0) | 17 (13.0) | 4 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 6.4 | Do you wash your hands after touching unwrapped cooked food? | 114 (86.0) | 18 (13.0) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 6.5 | Do you use separate kitchen utensils to prepare cooked and raw food? | 87 (65.0) | 26 (19.0) | 15 (11.0) | 6 (4.0) |

| 6.6 | Do you thaw frozen food at room temperature? | 61 (45.0) | 36 (27.0) | 25 (19.0) | 12 (9.0) |

| 6.7 | Do you wear personal protective equipment before handling food? | 66 (50.0) | 28 (21.0) | 27 (20.0) | 12 (9.0) |

| 6.8 | Do you check and certify external food items before consumption by patients? | 77 (58.0) | 36 (27.0) | 15 (11.0) | 5 (4.0) |

| 6.9 | Do you check integrity of hospital wheeler-bin foods before packaging to patients? | 79 (59.0) | 33 (25.0) | 12 (9.0) | 9 (7.0) |

| Practices score | Mean ± SD | Min-max | |||

| 87 ± 15 | 33 ± 100 | ||||

3.6. Oncology nurses’ opinion

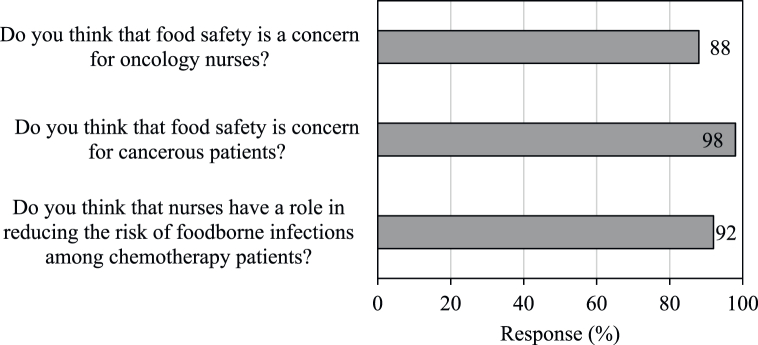

Around 92% of oncology nurses stated that they have a role in reducing the risk of foodborne infections among chemotherapy patients. According to Fig. 2, 88% of nurses believed that food safety is a concern for cancerous patients, 57% and 34% of them agreed and strongly agreed to this statement, respectively. Moreover, 98% nurses believed that food safety is a concern for oncology nurses, 57% agreed and 25% of them strongly agreed to such statement.

Fig. 2.

Food safety perception of oncology nurses (n = 134).

3.7. Association between socio-demographic characteristics and knowledge, attitude, practices dimensions

Table 5 displays the relationship between socio-demographic characteristics and knowledge, attitude, practices (KAP) dimensions. The results showed a significant relationship between marital status and the practices score (p = 0.04). Single oncology nurses scored the highest in practices with a mean score 91 and a standard deviation of 13, as compared to the married and ever married nurses which had each a mean practice score of 85 and 83, respectively. Moreover, a statistical significance was found between the level of education and knowledge score (p < 0.001). The results showed that nurses holding a graduate degree scored (mean = 85) more than the ones holding a technical degree (mean = 80). While nurses holding a university undergraduate degree, (Bachelor in Nursing) had the lowest mean score (74). Regarding the relationship between gender and KAP scores, no statistical significance was found. The same applies for age.

Table 5.

Association between socio-demographic characteristics and knowledge, attitude, practices dimensions (n = 134).

| Dimensions/Variables | Knowledge Mean ± SD | Pa | Attitude Mean±SDb | Pa | Practice Mean + SDb | Pa | KAP Mean ± SD | Pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.99 | 0.21 | 0.26 | 0.89 | ||||

| Male | 75 ± 13 | 91 ± 12 | 92 ± 13 | 83.07 ± 10.89 | ||||

| Female | 76 ± 12 | 95 ± 10 | 86 ± 15 | 83.38 ± 9.15 | ||||

| Age [20–30] | 76 ± 12 | 0.30 | 90 ± 13 | 0.05 | 94 ± 11 | 0.66 | 84.06 ± 9.5 | 0.41 |

| [31–40] | 74 ± 13 | 84 ± 18 | 96 ± 8 | 81.83 ± 9.3 | ||||

| [41–50] | 74 ± 10 | 78 ± 17 | 95 ± 6 | 79.7 ± 8.5 | ||||

| >50 | 83 ± 6 | 92 ± 11 | 97 ± 9 | 86.2 ± 5.97 | ||||

| Marital Status | 0.17 | 0.32 | 0.04 | 0.099 | ||||

| Single | 78 ± 13 | 94 ± 12 | 91 ± 13 | 85.52 ± 10.28 | ||||

| Married | 74 ± 11 | 96 ± 7 | 85 ± 17 | 81.94 ± 8.75 | ||||

| Ever married | 72 ± 14 | 92 ± 14 | 83 ± 13 | 82.07 ± 8.47 | ||||

| Level of Education | 0.00 | 0.09 | 0.30 | 0.002 | ||||

| Technical degree | 80 ± 11 | 89 ± 15 | 94 ± 11 | 83.91 ± 8.69 | ||||

| Bachelor in Nursing | 74 ± 12 | 84 ± 10 | 86 ± 15 | 82.05 ± 9.59 | ||||

| Graduate degree | 85 ± 2 | 99 ± 3 | 90 ± 11 | 90.19 ± 6.63 | ||||

| Years of Experience | 76 ± 12 | 0.82 | 94 ± 10 | 0.39 | 88 ± 14 | 0.70 | 83.72 ± 9.20 | 0.71 |

| Less than 5 [5–10] | 76 ± 12 | 94 ± 9 | 86 ± 16 | 82.12 ± 9.32 | ||||

| More than 10 | 75 ± 13 | 97 ± 8 | 85 ± 17 | 83.94 ± 10.46 | ||||

| Training for a relevant course | 0.00 | 0.90 | 0.35 | 0.023 | ||||

| No | 73 ± 14 | 94 ± 10 | 86 ± 16 | 81.7 ± 10.14 | ||||

| Yes | 79 ± 9 | 95 ± 11 | 89 ± 13 | 85.43 ± 7.99 | ||||

| Sources of information | 0.12 | 0.06 | 0.32 | 0.26 | ||||

| Media | ||||||||

| No | 77 ± 11 | 95 ± 10 | 87 ± 16 | 84.09 ± 9.7 | ||||

| Yes | 74 ± 13 | 93 ± 11 | 88 ± 13 | 82.17 ± 8.79 | ||||

| TV | 72 ± 15 | 0.01 | 94 ± 9 | 0.81 | 88 ± 12 | 0.33 | 80.77 ± 10.47 | 0.11 |

| Audio | 75 ± 20 | 0.01 | 98 ± 5 | 0.09 | 81 ± 17 | 0.43 | 82.76 ± 11.12 | 11.12 |

| Brochures | 77 ± 13 | 0.30 | 97 ± 8 | 0.00 | 88 ± 15 | 0.44 | 85.2 ± 9.9 | 0.039 |

| Conferences | 76 ± 11 | 0.00 | 94 ± 16 | 0.33 | 86 ± 16 | 0.00 | 83.36 ± 9.9 | 0.92 |

P: p-value.

SD: standard deviation.

A significant association was found between knowledge score and attending a course on food hygiene and foodborne diseases for chemotherapy patients (p < 0.001). Nurses that attended such course had higher mean knowledge score (79) than the ones who did not (73). Another significant association was observed between knowledge score and the following sources of information about food safety: TV (p = 0.01), conferences (p < 0.001), and audio (p = 0.01). Furthermore, results showed a significant association between attitude score and nurses who read brochures to get information about food safety (p < 0.001). And finally, a statistically significant association was found between practice score and attending conferences to get information about food safety (p < 0.001).

Moreover, the overall composite KAP score was 83.4%. The results showed that nurses with higher education (graduate degree) obtained significantly higher KAP (90.2%) than those with bachelor or technical degree (83.9, 82.1%, respectively with p = 0.002). Those who had a training in food safety (85.4%; p = 0.023) and those who obtain information from brochures (85.2 p = 0.39) had significant higher KAP scores as compared to the other nurses. There was no statistically significant relationship between years of experience and KAP dimensions.

4. Discussion

This study presents many critical information regarding the knowledge, attitudes and practices of oncology nurses working in private hospitals located in Beirut and Mount Lebanon, with patients during their chemotherapy treatments.

4.1. Knowledge on neutropenic diet

Most of oncology nurses participating in this study agreed that they have an important role in educating their patients in order to reduce foodborne illness. Food safety remains a concern to most of them and their patients. In a previous study, chemotherapy patients reported that they were provided with food safety recommendations only when experiencing neutropenia, and they stated that it was preferable to be informed earlier [3]. Previous studies have shown that although patients receiving chemotherapy reported awareness of food safety practices, self-reporting indicated that potentially unsafe practices may be used in relation to temperature control, handwashing, safe cooking and adherence to use-by-dates [27]. Hence, food safety education for chemotherapy patients should be implemented by oncology nurses during the first six months after diagnosis, and at the beginning of chemotherapy treatment. Moreover, food safety instructions on how to decrease the risk of foodborne infections must be added as a standard of practice for health professionals working with vulnerable populations as found in Ref. [19]. It is also suggested that inconsistencies on the nurses’ interpretation of neutropenic diet can lead to patient being misinformed about food safety standards and permitted foods in their diet [28]. Accordingly, it is suggested that the low knowledge on neutropenic diet could be alleviated if patients are educated on food safety to improve the safe food preparation and storage as well as implement best attitudes and safe practices.

The main sources of information about food safety were cited from the most used to the least one: conferences (74%), brochures (47%), media (36%), TV (20%), audio (5%). In contrast to the findings of [23], where the most frequently adopted sources of information reported were mass media, and audio/visual materials. Buffer et al. (2013) [19] also reported that more than half of nurses (56%) did not attend a course on food safety for chemotherapy patients. These findings show that most of the nurses obtained their food safety knowledge through unreliable sources that are not always valid and could be not very accurate or science based.

Moreover [18], highlighted the positive impact of covid-19 outbreak on food safety knowledge. They revealed that the agreement rate of Chinese medical caregivers (n = 1431) with various food safety statements have changed after the covid-19 pandemic compared to before the pandemic. The number of participants who agreed that patient education toward food safety is crucial increased from 398 to 595 before and after the pandemic, respectively. Furthermore, the agreement that when patients are well educated about food safety, their foodborne infection risks will be reduced, increased among participants after the pandemic (279) as compared to before the outbreak (190) [18].

4.2. Knowledge of safe food preparation and storage

Lebanese oncology nurses showed a good knowledge regarding safe food preparation and reheating, proper working temperature of refrigerators, and appropriate storage temperature for both hot and cold ready to eat food with 60%–99% range of correct answers to the related questions. Similar results were reported by Refs. [22,23] where 68.1% (n = 401) and 70% (n = 340) of nurses respectively agreed that preparation of food in advance may contribute to food poisoning, while 91.5% and 43.7% of them respectively agreed that reheating food may lead to food contamination. Furthermore, it was also reported that among 254 food handlers working in Lebanese hospitals, 58.7% and 78.3% of them were aware of the hazards behind the preparation of food in advance and reheating it, respectively [24]. In the present study, 65% of the Lebanese nurses demonstrated good understanding of correct working temperature of a refrigerator to maintain food under healthy conditions. A similar score was shown with Italian nurses [23] where among 401 nurses, 67.1% demonstrated proper knowledge of temperature controls for food storage, in contrast to the score of Nigerian nurses [22] where only 27.1% were knowledgeable of such information. Moreover, 49.7% of 163 food service staff working in hospitals in Saudi Arabia answered correctly food storage questions [29]. Among 254 food handlers working in Lebanese hospitals, most of them (72.4%) acknowledged the correct working temperature of a refrigerator [24]. The proper storage temperature of hot and cold ready to eat food was expressed by 64% and 60% of respondents of the current study, respectively. Buccheri et al. (2007) [23] reported higher percentage of nurses unable to provide proper temperature controls for cold and hot, ready-to-eat food (83.5% and 37.7%, respectively). Furthermore, among 340 Nigerian nurses, 80.6% and 93.5% of them were not aware of the correct storage temperature of hot and cold ready to eat foods, respectively [22]. However, similar to this study, among 254 food handlers working in Lebanese hospitals, 66.5% and 67.3%, respectively specified correctly the storage temperature for hot and cold ready to eat foods [24].

In consistence with this study findings, among 401 nurses, more than 95% knew that the incorrect application of cleaning/sanitizing procedures on equipment (refrigerator, slicing machine) can increase the risk of foodborne disease to inpatients [23]. Moreover, the same results were reported by Ref. [24], where among 254 food handlers, 91.7% answered correctly to the relevant questions.

Around 96% of nurses were informed about the hospital's standard operating procedure for food handling reflected by a very high score in comparison to the findings of [22], where among 340 nurses working in Nigerian hospitals, only 40.1% of participants were aware of these standards. Accordingly, almost all oncology nurses (98%) agreed that hand washing before handling food can reduce the risk of food contamination, which is consistent with the findings of [22] where 97% of respondents acknowledged this statement. In addition, about 78% of respondents were aware of the importance of wearing gloves while handling food to reduce the risk of transmitting foodborne infection to patients' food, in contrast to the findings of other studies where only 61.1% (n = 401) and 51.3% (n = 340) of participants answered correctly to the question [23]. Moreover, according to the findings of [24], among 254 food handlers working in Lebanese hospitals, 66.1% stated that wearing gloves while handling food reduces the risk of transmitting infection to consumers.

These conflicting results and low level of knowledge among oncology nurses in Lebanese hospitals could be due to the fact that less than half of them had attended a course on food safety and they mostly based their information on conferences, brochures, media and TV. A more structured and standardized training could be suggested for these nurses. Free and routine training could be also suggested in order to reach out to large number of these nurses.

4.3. Knowledge on foodborne diseases

This study results showed that oncology nurses working in Lebanese hospitals had lower knowledge on food associated with the transmission of cholera (82%) and hepatitis B (28%) as compared to nurses working in Nigerian hospitals (87.4% for hepatitis B and 98.5% cholera) [22].

This shows that oncology nurses working in Lebanese hospitals lack knowledge regarding the transmission of foodborne diseases, which might be due to inadequate training courses. These findings represent a crucial concern specially that it was reported that cancerous patients have a five times higher risk of listeriosis and that 15%–25% of serious salmonellosis occur among them [27]. Thus, it is recommended to adopt training courses for oncology nurses targeting the causes of foodborne infections, the sources of organisms causing these infections, and the appropriate preventive measures. It is also suggested to empower these nurses to communicate correct information by supporting them with needed training tools, documents, and adapted flyers. The communication with nurses, patients and their families is important in order to share and deliver information and advice on food safety issues and emerging risks. The communication activities range from providing science based and accurate information to developing educational programs and to training patients, nurses and other health workers [16].

4.4. Total knowledge score and associations

Nurses working in Lebanese hospitals (n = 134) showed a fair mean knowledge score (76%) toward food safety, in contrast to the mean knowledge score of nurses working in Nigerian and Italian hospitals which was 29.4% (n = 340) and 51.1% (n = 401), respectively [22,23]. This fair score could be a result of the continual influx of research providing new information about food, which is challenging for nurses to stay up to date and well informed on a broad variety of health subjects [19]. This knowledge score could be also the result of the food safety campaign launched in 2014 via the social media across the country [24]. In Lebanon, nurses scored higher on knowledge (76%) as compared to food handlers working in the same hospitals (59.2%) [24], food handlers working in different types of food business management (56.6%) [30] and Lebanese university students (53.6%) [16]. These findings might be due to the fact that nurses are more familiar with hygiene protocols, infection sources and the measures to prevent it, since these points are considered as a priority in their daily nursing care plan.

According to literature, it is expected nurses must score higher since working with vulnerable patients is a key motivator to the health caregivers to engage the nurses to be more knowledgeable about food safety and educate their patients to prevent the risk of a foodborne infection [19]. According to Ref. [31], nursing students in Chongqing, China have a significant deficiency in food safety education as compared to medical students and education students.

Moreover, the findings of this study proved that attending a course on food hygiene and foodborne diseases was significantly associated with a higher mean knowledge score (p < 0.001). Similarly [24], reported that trained food handlers (60.8%) (n = 254) who work in Lebanese hospitals showed remarkable high scores in knowledge (p = 0.001) compared to the food handlers that had not attended any training course. Moreover, the same was reported in the study of [23], where they concluded that nurses who attended a minimum of one educational course performed way better in knowledge questions. Similarly [32], found that the knowledge level (8.50 ± 2.01) among 90 food vendors in public primary schools in Abeokuta, Ogun State, Nigeria significantly increased after a food safety training conducted by nurses (9.77 ± 2.24).

These findings highlight the need to include food safety chapters in the training curriculum of nurses at all levels and there should be a credible standardized food safety source specific for chemotherapy patients.

4.5. Attitude toward food safety

Most of the oncology nurses (98%) knew the necessity of checking the refrigerator/freezer operating conditions periodically, to reduce food spoilage and health risks to patients, similarly to the nurses in Italian hospitals [23] and food handlers in the Lebanese hospitals [24]. Moreover, the majority of nurses (96%) noted the importance of wearing protective equipment before handling food, similarly to the Italian nurses (more than 95%) [23] and much better that the Nigerian nurses (80.4%) [22] and the food handlers who work in hospitals Lebanon (40% out of 254) [24]. The high knowledge of oncology nurses in regard to the refrigerator/freezer operating temperatures could be due to the fact that Lebanon experience frequent electricity shortage that may lead to fluctuating temperatures and even spoilage incidences. This highlight the fact that knowledge could be developed from previous experiences.

Furthermore, 95% of oncology nurses in this study acknowledged the importance of separating raw food from cooked ones. However, those findings were higher among oncology nurses as compared to nurses serving general wards in Italy and Nigeria [22,23], where 78.3% (n = 401) and 86% (n = 340) of respondents, respectively stated that they adopted this key measure to avoid cross-contamination. Similar results were reported by Ref. [31] where among 918 nursing students from China colleges, 88.2% agreed on the importance of this measure.

Moreover, 90% of Italian nurses and 94.1% of food handlers in Lebanon stated that food-service staff with abrasions or cuts on hands should not touch unwrapped food which is consistent with the findings the previous studies mentioned [23,24].

Most of the oncology nurses (89%) in this study acknowledged that defrosted foods should not be refrozen; showing a higher score than that of the food handlers who work in Lebanese hospitals where 79.9% of them (n = 254) knew this [24]. Moreover, only 13.2% of the nurses in Italian hospital were aware of not refreezing defrosted foods [23].

Those findings suggest the importance of forming a special food safety committee in each hospital to enforce food safety and hygiene protocols and monitor the staff's attitude.

4.5.1. Attitude score

In general, nurses had a good attitude score 95%, in contrast to other studies where only out of 340 and 401 nurses, 57% and 58.1% respectively exhibited a good attitude towards food safety and hygiene [22,23].

Yet, similar results to the present study were reported by Ref. [24], where 254 food handlers working in Lebanese hospitals had a score of 83.7% on attitudes questions. Furthermore [16], also reported consistent attitudes score of food handlers working in various types of food business management in Lebanon which was 86.3% over 100 possible points.

The reasons behind these scores being higher than the other studies, might be related to the fact that this study was conducted recently, where food safety is being taken more into consideration and more awareness is being spread in the country. Moreover, food safety incidents are reported more frequently in the news and goes viral on social media.

4.6. Practices toward food safety

Similar to this study findings [16,24], reported that the majority of food handlers wash their hands with soap and water before eating or preparing food. Moreover [30], also reported that among 1172 Lebanese university students, 87% stated that proper hand washing before and after touching food reduce the risk of food contamination. Surprisingly, only 30.6% out of 918 nursing students from Chongqing in China always wash their hands before handling food [31].

Most of the nurses agreed that permanent handwashing before and after handling unwrapped raw and cooked foods is important in preventing foodborne illnesses. The study findings were slightly better than those reported by Ref. [23], in which 78.3% and 78.6% of participants adopted this practice respectively, for raw foods and for cooked foods, 77.3% and 83.6% of participants implemented this practice, respectively.

Only 65% of nurses stated that they “always” use separate kitchen utensils to prepare cooked and raw food. A very close percentage was also reported among 401 nurses working in Italian hospitals where only 63.1% of the participants stated “always” as an answer. However [16,24], reported that 89.5% (n = 80) and 77% (n = 254) of food handlers, respectively used separate kitchen utensils and cutting boards to prepare raw and cooked foods.

Moreover, more than half of the participants (59%) noted that they “always” check the integrity of hospital wheeler-bin foods before packaging to patients, while none of the respondents (0%) in Ref. [22] study adopted this practice. Only fifty-eight percent of nurses noted that they “always” check shelf life of the products and integrity of packages, which is considered an unsatisfactory adopted behavior compared to the findings of [23,24] where the majority of respondents reported checking shelf life of food products and the integrity of the packaging.

Furthermore, half of nurses mentioned that they “always” wear PPE before handling food, which represents a significantly high score as compared to results reported by the nurses in Italian hospital where among 340 nurses, only 7.4% of respondents noted that they “always” wear PPE.

Finally, 45% of nurses mentioned that they “always” thaw frozen food at room temperature compared to the findings reported by Refs. [23,24] where 61.3% (n = 401) and 78.2% (n = 254), respectively stated that they still adopt this practice that is not a safe one and more education is required for nurses. Similarly, only 32% of nursing students (n = 918) in China, knew that frozen food should be thawed in refrigerators [31]. Moreover, in another study conducted in nine hospitals in South Africa, it was reported that chefs (n = 34) significantly knew more than nurses on how to safely thaw frozen food (n = 148) [21]. It is suggested that having deficiency and hesitance in food safety knowledge, will generate a negative attitude and subsequently affect safe food handling practices.

4.6.1. Practices score

The participants’ mean practices score was good (86.9%), while 54% and 73.7% of nurses who work in Nigerian and Italian hospitals respectively demonstrated a good food handling practice [22,23]. Interestingly, food service staff (n = 163) from different hospitals in Al Madinah city, Saudi Arabia had a high practices score of 92.6% [29]. This high score was found to be associated with the high level of education as well as receiving a training on food hygiene and food safety practices [29].

In Lebanon, 254 food handlers working in Lebanese hospitals scored 83.2% on the practices’ questions [24], 80 food handlers working in different types of food business management scored 61.3% [16], and 1172 Lebanese university students scored 44.7% [30]. Hence, Lebanese oncology nurses recorded the highest practices scores among other populations working in Lebanon. It is suggested that food safety practices could be affected by lack of continuous education and training.

4.7. KAP composite score

In this study, the overall KAP mean score were considered good (80% and above) as suggested by Ref. [26]. Those scores were good (83.5%) and remarkably higher among participants who had higher education (bachelor degree) and those obtaining information from brochures. Other attributes did not significantly affect the overall score. Similar to these findings, the KAP score was also high among food handlers working in hospital in Jordan (87.9%), while the score was higher among those with higher educational level where the respondents who have obtained a college (90.7) and university degrees (92.1%) scored higher than the ones with elementary (79.7%) and secondary degrees (86.2%) [33]. The scores between females (90.0%) and males (86.6) were also remarkably different (p < 0.05) [33]. Contrary to our results, food handlers in Lebanese hospitals had lower KAP score of 75.4% [24]. Based on these results it could be supposed that the knowledge related to food safety is mostly acquired during bachelor's degree and maybe incorporating additional chapters or courses could improve further the score. Moreover, the use of brochure as communication route for these information could have a significant effect on improving the KAP of nurses. To date several studies assessed the KAP score and association. It is suggested that the KAP model is capable of ensuring the hygienic-sanitary quality of food. It is concluded that oncology nurses given suitable food safety trainings and food hygiene knowledge, are able to change their attitudes and improve their practices voluntary [34].

5. Concluding remarks

This study supplies valuable data regarding the level of knowledge, attitude and practices in food safety of oncology nurses working in Lebanese private hospitals located in Beirut and Mount Lebanon. Overall, participating oncology nurses showed good scores in both attitudes and practices parts towards food safety, however their knowledge scores were fair and thus considered less satisfactory. Furthermore, the overall combined KAP score was good. Some limitations are present in this type of study in term of bias in false reporting good practices. The study population represents mainly Lebanese oncology nurses who work in private hospitals located in Beirut and Mount Lebanon. Moreover, public hospitals were not included in the study because the hospital IRB approval was lengthy and complicated. Accordingly, it is suggested that the figures are better than the reality. On the other hand, the knowledge deficit is attributed to lack of training for oncology nurses regarding food safety measures for patients receiving chemotherapy and could be a risk for this category of patients. Hence, routine and frequent interventions are required for the prevention and reduction of foodborne illnesses. Nurses’ knowledge could be improved through the implementation of standardized food safety training courses especially those working with vulnerable populations. This educational intervention will help them in having more confidence in their knowledge, making them a reliable source of information for patients, as well as generating a positive attitude and enhancing safe food handling practices. Moreover, a special food safety committee in each hospital governed by the Ministry of public health could be formed, to enforce food safety protocols, monitor and evaluate staff performance, and keep the staff up to date with new standards.

Funding sources

No external funding.

Author contribution statement

-

1

- Conceived and designed the experiments; Angy Mallah, Najwa El Gerges, Christelle Bou Mitri, Layal Karam

-

2

- Performed the experiments; Angy Mallah

-

3

- Analyzed and interpreted the data; Najwa El Gerges, Christelle Bou Mitri, Maya Abou Jaoude, Layal Karam

-

4

- Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Angy Mallah, Najwa El Gerges

-

5

– Wrote the paper: Angy Mallah, Christelle Bou Mitri, Maya Abou Jaoude, Layal Karam

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding was provided by the Qatar National Library.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e12853.

Contributor Information

Layal Karam, Email: lkaram@qu.edu.qa.

Christelle Bou Mitri, Email: cboumitri@ndu.edu.lb.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2019;69(1):7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mehrling T. Chemotherapy is getting “smarter”. Future Oncol. 2015;11(4):549–552. doi: 10.2217/fon.14.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paden H., Hatsu I., Kane K., Lustberg M., Grenade C., Bhatt A., Diaz Pardo D., Beery A., Ilic S. Assessment of food safety knowledge and behaviors of cancer patients receiving treatment. Nutrients. 2019;11(8):1897. doi: 10.3390/nu11081897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Vol. 62. 2013. Vital Signs: Listeria Illnesses, Deaths, and Outbreaks — United States; pp. 448–452. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barkley J., Viveiros B., Michael Gosciminski M.T., Utpala Bandy M.D. Preventing foodborne and enteric illnesses among at-risk populations in the United States and Rhode Island. R. I. Med. J. 2016;99(11):25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans E.W., Redmond E.C. An assessment of food safety information provision for UK chemotherapy patients to reduce the risk of foodborne infection. Publ. Health. 2017;153:25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2017.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clemons K.V., Salonen J.H., Issakainen J., Nikoskelainen J., McCullough M.J., Jorge J.J., Stevens D.A. Molecular epidemiology of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in an immunocompromised host unit. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2010;68(3):220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edvinsson B., Lappalainen M., Anttila V.J., Paetau A., Evengård B. Toxoplasmosis in immunocompromized patients. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 2009;41(5):368–371. doi: 10.1080/00365540902783319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin H.M., Campbell B.J., Hart C.A., Mpofu C., Nayar M., Singh R., Englyst H., Williams H.F., Rhodes J.M. Enhanced Escherichia coli adherence and invasion in Crohn's disease and colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(1):80–93. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.FDA U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Food Safety for older adults and people with cancer, diabeter, HIV/AIDS, organ translplants and autoimmune diseases. 2020. https://www.fda.gov/media/83744/download

- 11.FAO/WHO . WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2004. Risk Assessment of Listeria Monocytogenes. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gradel K.O., Nørgaard M., Dethlefsen C., Schønheyder H.C., Kristensen B., Ejlertsen T., Nielsen H. Increased risk of zoonotic Salmonella and Campylobacter gastroenteritis in patients with haematological malignancies: a population-based study. Ann. Hematol. 2009;88(8):761–767. doi: 10.1007/s00277-008-0662-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silk B.J., Date K.A., Jackson K.A., Pouillot R., Holt K.G., Graves L.M., Ong K.L., Hurd S., Meyer R., Marcus R., Shiferaw B. Invasive listeriosis in the Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet), 2004–2009: further targeted prevention needed for higher-risk groups. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;54(suppl_5):S396–S404. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Public Health Laboratory Service Health protection report infection reports. Listeriosis in England and Wales in 2014. 2015;9 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lund B.M., O'Brien S.J. The occurrence and prevention of foodborne disease in vulnerable people. Foodb. Pathog. Dis. 2011;8(9):961–973. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2011.0860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Faour-Klingbeil D., Kuri V., Todd E. Investigating a link of two different types of food business management to the food safety knowledge, attitudes and practices of food handlers in Beirut, Lebanon. Food Control. 2015;55:166–175. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Medeiros L.C., Chen G., Kendall P., Hillers V.N. Food safety issues for cancer and organ transplant patients. Nutr. Clin. Care. 2004;7(4):141–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luo L., Ni J., Zhou M., Wang C., Wen W., Jiang J., Cheng Y., Zhang X., Wang M., Wang W. Food safety knowledge, attitudes, and self-reported practices among medical staff in China before, during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Risk Manag. Healthc. Pol. 2021;14:5027. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S339274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buffer J., Kendall P., Medeiros L., Schroeder M., Sofos J. Nurses and dietitians differ in food safety information provided to highly susceptible clients. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2013;45(2):102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Department of Health, Social Services & Public Safety . 2007. Get Your 10 a Day! the Nursing Care Standards for Patient Food in Hospital. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teffo L.A., Tabit F.T. An assessment of the food safety knowledge and attitudes of food handlers in hospitals. BMC Publ. Health. 2020;20(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-8430-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oludare A.O., Ogundipe A., Odunjo A., Komolafe J., Olatunji I. Knowledge and food handling practices of nurses in a tertiary health care hospital in Nigeria. J. Environ. Health. 2016;78(6):32–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buccheri C., Casuccio A., Giammanco S., Giammanco M., La Guardia M., Mammina C. Food safety in hospital: knowledge, attitudes and practices of nursing staff of two hospitals in Sicily, Italy. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2007;7(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bou-Mitri C., Mahmoud D., El Gerges N., Abou Jaoude M. Food safety knowledge, attitudes and practices of food handlers in lebanese hospitals: a cross-sectional study. Food Control. 2018;94:78–84. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Food Safety During and After Cancer Treatment Retrieved from cancer. 2018. https://www.cancer.net/survivorship/healthy-living/food-safety-during-and-after-cancer-treatment

- 26.Norhaslinda R., Norhayati A., Mohd A. Knowledge, attitudes and practices (KAP) on good manufacturing practices (GMP) among food handlers in Terengganu hospitals. Int. J. Pharm. Pharmaceut. Sci. 2016;8:53–59. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Evans E.W., Redmond E.C. Food safety knowledge and self-reported food-handling practices in cancer treatment. Oncol. Nurs. Forum. 2018, September;45(No. 5) doi: 10.1188/18.ONF.E98-E110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sosa S.G., Tweedy E., Araujo P., Alencar A., Alencar M.C. Optimizing oncology nurses knowledge on neutropenic diet and food safety standards through evaluation and education. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2019;25(3):S436–S437. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alqurashi N.A., Priyadarshini A., Jaiswal A.K. Evaluating food safety knowledge and practices among foodservice staff in Al Madinah Hospitals, Saudi Arabia. Saf. Now. 2019;5(1):9. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hassan H.F., Dimassi H. Food safety and handling knowledge and practices of Lebanese university students. Food Control. 2014;40:127–133. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Luo X., Xu X., Chen H., Bai R., Zhang Y., Hou X., Zhang F., Zhang Y., Sharma M., Zeng H., Zhao Y. Food safety related knowledge, attitudes, and practices (KAP) among the students from nursing, education and medical college in Chongqing, China. Food Control. 2019;95:181–188. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sodimu Jeminat O., Asonye Christian C.C. 2020. Effectiveness of a Nurse-Led Training on Food Safety Practices Among Public Primary Schools Food Vendors in Abeokuta South Local Government. (Ogun State) [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharif L., Obaidat M.M., Al-Dalalah M.R. Food hygiene knowledge, attitudes and practices of the food handlers in the military hospitals. Food Nutr. Sci. 2013;4(3):245. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baş M., Ersun A.Ş., Kıvanç G. The evaluation of food hygiene knowledge, attitudes, and practices of food handlers' in food businesses in Turkey. Food Control. 2006;17(4):317–322. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.