Abstract

Objectives

The rapid onset and progressive course of the COVID-19 pandemic challenged primary care practices to generate rapid solutions to unique circumstances, creating a natural experiment of effectiveness, resilience, financial stability and governance across primary care models. We aimed to characterise how practices in Melbourne, Australia modified clinical and organisational routines in response to the pandemic in 2020–2021 and identify factors that influenced these changes.

Design

Prospective, qualitative, participatory case study design using constant comparative data analysis, conducted between April 2020 and February 2021. Participant general practitioner (GP) investigators were involved in study design, recruitment of other participants, data collection and analysis. Data analysis included investigator diaries, structured practice observation, documents and interviews.

Setting

The cases were six Melbourne practices of varying size and organisational model.

Participants

GP investigators approached potential participants. Practice healthcare workers were interviewed by social scientists on three occasions, and provided feedback on presentations of preliminary findings.

Results

We conducted 58 interviews with 26 practice healthcare workers including practice owners, practice managers, GPs, receptionists and nurses; and six interviews with GP investigators. Data saturation was achieved within each practice and across the sample. The pandemic generated changes to triage, clinical care, infection control and organisational routines, particularly around telehealth. While collaboration and trust increased within several practices, others fragmented, leaving staff isolated and demoralised. Financial and organisational stability, collaborative problem solving, creative leadership and communication (internally and within the broader healthcare sector) were major influences on practice ability to negotiate the pandemic.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates the complex influences on primary care practices, and reinforces the strengths of clinician participation in research design, conduct and analysis. Two implications are: telehealth, triage and infection management innovations are likely to continue; the existing payment system provides inadequate support to primary care in a global pandemic.

Keywords: PRIMARY CARE, Health policy, Change management, VIROLOGY

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

Our prospective case study design provided a detailed understanding of the evolution of clinical and organisational routines within Australian general practices of varying models through the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our use of general practitioners as participant investigators overcame the challenges of recruiting and collecting data from practices at a time when external researchers were unable to enter practices due to public health restrictions.

The credibility of our findings is increased by the multimethod data collection strategy (providing a detailed, intensive exploration of individuals and organisations in context) and our presentation of emergent findings to practice teams.

Practices were all from Melbourne, the region in Australia that experienced both the highest COVID-19 case numbers and most prolonged and extensive lockdowns during 2020.

Different practice routines may have emerged in other contexts, such as rural practices and those with no association with a university department of general practice.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has challenged healthcare systems1 and generated major changes in the delivery of primary care.2 While Australia was spared high COVID-19 mortality during 2020,3 two-thirds of 2020 COVID-19 cases and nearly 90% of deaths were in the Melbourne metropolitan region (5.1 million population), following a 4-month outbreak. In response, between July and October 2020, the Victorian state government imposed one of the world’s most stringent lockdowns.4

Both federal and state governments in Australia stressed the importance of primary care to the overall pandemic response. Australian primary care is largely delivered through a network of small, owner-operated general practices. Ten per cent of practices are owned by large corporate entities,5 and most states have a small number of comprehensive primary healthcare organisations, similar to community health centres (CHCs) in other nations (see table 1 for a list of all abbreviations).6 Under Australia’s federal government single-payer insurance scheme, the Medical Benefits Schedule (MBS), general practitioners (GPs) are paid a standard amount for each consultation, and can either accept that payment (‘bulk-bill’) or charge an additional ‘co-payment’ to the patient.

Table 1.

Abbreviations

| AOD | Alcohol and other drug |

| CALD | Culturally and linguistically diverse |

| CDM | Chronic disease management |

| CHC | Community health centre |

| FTE | Full-time equivalent |

| GP | General practitioner |

| MBS | Medical Benefits Schedule |

| N | Nurse |

| PPE | Personal protective equipment |

| PM | Practice manager |

| PO | Practice owner |

| R | Reception staff |

| SES | Socioeconomic status |

While complex systems such as primary care are generally robust,7 situations of instability can generate an ‘edge of chaos’ state between ‘equilibrium and complete disorder where systems have the potential to be most adaptive and creative’,8 but where ‘systems that do not successfully change can become extinct’.9 The early phase of the pandemic generated such a scenario within Australian general practice.

There is limited research on the experiences of primary care practices providing care within the systemic strains caused by the pandemic. We asked: (a) what changes to clinical and organisational routines were made during the first year of the pandemic? and; (b) what contextual, organisational and individual factors facilitated these changes? We anticipated that addressing these questions would provide insights into the adaptivity and robustness of the primary care system within Australia.

Methods

Design

We used a participatory, prospective, qualitative case study10 design, within which GP participant investigators shaped the project, and contributed to data collection and analysis.11 Design was informed by principles of participatory action research in which processes of planning, action and reflection are conducted in close collaboration with stakeholders and participants (here referring to both GP investigators and practice owners (PO) and other staff).12 Our methodology (including data collection tools, and approach to analysis) has been detailed elsewhere,12 and data collection is summarised below.

GP investigators comprised four clinician educators (JN, KA, SH and TSS) and two clinician researchers (GR and EAS), alongside two social science research fellows (JA and RL) with PhDs and experience in qualitative research. Each investigator was affiliated with a single university department of general practice. WLM and BFC acted as external advisors.

The practices constituted the cases being compared; they were the unit of analysis. Investigators were clinicians at these practices, and social scientists. Data sources were GP investigator observations, practice documents, interviews with practice clinicians and staff, responses to a presentation of interim findings to practices and reflective interviews with GP investigators.

Setting and participants

The study was set in six general practices of varying size and organisational model in metropolitan Melbourne. Aligned with the participatory approach, practices were chosen from locations where GP investigators based their clinical work. GR and EAS contacted potential participant investigators from GPs who were either current academic staff or recent PhD graduates of the Department of General Practice, prioritising those working within practices of varying size and organisational model.12 Practice interview participants included GPs, nurses, practice managers (PM) and administrative staff. The GP investigators gained written informed consent from practice participants; the social scientists gained written consent from GP investigators for their reflective interviews. Data were collected between April 2020 and February 2021.

Data collection

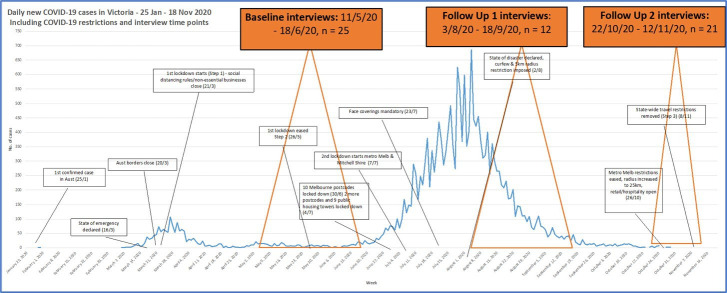

The GP investigators used structured diaries to record their experiences. They completed a practice description tool13 14; collated and photographed practice documents, signage and layout; and provided continuing input to data collection. RL and JA conducted semistructured, in-depth, audio-recorded telephone or videoconference interviews (30–60 min) with clinicians and administrative staff from each practice at three time points (see figure 1). Subsequently, each GP investigator was interviewed once in early 2021, to reflect on data collected and their experiences. Interviews focused on participants’ individual experiences, perceived practice responses and beliefs about factors influencing practice performance. Practice staff were invited to attend live video presentations by investigators of emerging findings at mid and end of the project. Responses were collected and informed analysis.

Figure 1.

COVID-19 in Victoria during 2020. Data Collection Timeline.

Data management

All digital data were stored on a secure server only accessible by JA, RL and project manager Sharon Clifford. Interviews were professionally transcribed and all identifying information removed. Interview transcripts and observational data (diaries, practice documents and field notes) were coded by JA and RL using NVivo.12 15 Our iterative coding template was based on concepts from Miller et al’s relationship-centred model of primary care practice development,16 themes derived from initial reading and familiarisation with the raw data, and further emerging data themes.

Data analysis

Data analysis used a constant comparative approach17 informed by prior approaches to investigation of primary care practice routines.14 18 JA and RL undertook data analysis, which was refined at regular meetings with GR and JN, and at a data retreat19 with all investigators.

The use of matrices facilitated cross-case comparisons.20 An initial matrix organised summarised data under thematic codes (rows) versus practices (columns). Subsequently, further summarised matrices were used to generate narratives, which described the key elements of changes in each practice. As outlined in the protocol paper, intervention narratives and the matrices were further analysed through cross-case analysis to develop hypotheses to explain the implementation, uptake and sustainability of routine changes that followed the commencement of the pandemic.12 Secondary analysis on the themes of leadership and staff burden has informed subsequent journal article submissions. Reporting followed Tong et al’s Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research.21

Patient and public involvement

Given limitations imposed by the pandemic on interaction with members of the community, this research was carried out without patient involvement.

Results

We recruited six of eight practices approached. One practice was part of a federal and state-funded CHC, another was part of a large corporate network and the remainder were general practices of varying size, organisational structure, billing practices and patient characteristics (see table 2). All were organisationally and financially stable prior to the pandemic. We conducted 58 interviews with 26 practice staff including POs, PMs, GPs, reception staff (R) and nurses (N); and six interviews with GP investigators. Data saturation was achieved at the level of each practice and across the sample. The CHC-based investigator left the practice in August 2020. Subsequently, another GP working at the practice provided liaison, but did not collect data.

Table 2.

Participating practices

| Practice pseudonym | Type of practice | Location | Billing system* | Practice population | GP FTE in practice | Nurse FTE in practice | Allied health disciplines |

| CHC | Community health centre | Inner city suburbs | Bulk billing | Lower SES, CALD, refugees, AOD | 6 FTE | 5 | Numerous health and social care disciplines |

| SE1 | Private general practice | South-eastern suburbs | Blended | High SES, children and elderly | 3.5 FTE | 2 | Dentist |

| E | Private general practice | Eastern suburbs | Blended | High SES, very few CALD | 4–5 FTE | 1 FTE (3 in total) | Diabetes educator |

| CBD | Private general practice | Central business district (CBD) |

Blended | Higher SES, tourists, multilingual GPs | 3.5 FTE | 1 FTE (2 in total) | Clinical psychology |

| SE2 | Private general practice within large corporate entitiy | South-eastern suburbs | Bulk billing | Mid to low SES, broad patient mix | 14 FTE | 3.5 FTE | Physiotherapy, dietetics |

| W | General practice and health hub | Western suburbs | Blended | Low SES, gentrifying | 15+ GPs | 3.5 FTE | Numerous colocated disciplines including psychology, dietetics, physiotherapy, podiatry |

*Bulk billing is where clinicians accept the Medicare benefit as full payment for the service. A blended system is where clinicians bulk bill some patients and require a copayment from others.

AOD, alcohol and other drug patients; CALD, culturally and linguistically diverse patients; CHC, community health centre; FTE, full-time equivalent; GP, general practitioner; SES, socioeconomic status.

Our team reflected on the time passage of the pandemic in its first year. We felt that the data would be easier to understand if it were contextualised by stages. The names were approved by consensus and are intended to provide context through which to understand the broad study findings.

Clinical and organisational routines evolved with the stages of the pandemic, patient demand and changes to MBS telehealth payments. Prepandemic plans required for practice accreditation prior to 2020 had minimal influence, and practices struggled with conflicting advice from government and professional organisations at times. Stability of the practice core, functional leadership, organisational model and communication were major influences on the ability of practices to modify routines to complex and unpredictable challenges. We begin by describing the evolution of the pandemic within the practices, followed by an interpretation of the drivers of routine change seen through the lens of the relationship-centred model.

Early chaos (February 2020 to April 2020)

Practices began to be aware of the pandemic’s implications in February 2020:

We expected to be overwhelmed with very sick people and we were basing that on what was happening in other countries… we had plans for home palliation, staggered staff shifts in case one shift was infected and the Health Department ordered everyone on that shift to disappear, so week on, week off. (CHC GP2)

The subsequent weeks were chaotic, as workplaces changed overnight:

For two weeks at the very beginning, like early-mid March, it was absolute chaos. Just in terms of the volume of patients that were calling non-stop. Mostly phone calls, and mostly people really desperately wanting testing…. At first it was like very overwhelming, but then it became a new norm to just, ‘This is the new thing. Do it. Adapt, adapt, adapt.’ (CBD R)

Many staff became increasingly frustrated by shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE) and changing advice from government and professional bodies. They were concerned for their safety and that of their families and about the potential impact of rapid community transmission. The MBS broadened the eligibility for telehealth consultations (previously limited to rural and remote areas), allowing some older GPs and other vulnerable staff to work from home, which increased the complexity of receptionists’ work.

Emerging stability (May 2020 to June 2020)

With cases falling, Victoria’s community lockdown was lifted in late May. After the early disruption, the impact was less than feared:

The initial tension, anxiety, shock where people saw the horrendous news items from overseas: you could sense that in the doctors here, and the staff.… so initially there was a run for shelter.… People feel as if things are well controlled and reasonably calm at the moment in terms of illness. (SE2 GP)

All practices had incorporated fundamental changes to their work routines (see table 3):

Table 3.

Key pandemic-generated modifications to safety, clinical, workflow and practice management routines

| Workflow routine | Definition | Description of changes |

| 1 Keeping staff and patients safe | Procedures to reduce infectious disease transmission. | Increased PPE use; enhanced cleaning practices by external cleaners and practice staff. Patient waiting routines, for example, changed waiting room layout; wait in their car/outside until appointment times. Booking processes: all practices paused patient ability to make appointments online. Receptionists began to check respiratory symptoms and travel/contact history during patient booking for appointments by telephone and on arrival. Staff-to-staff contact reduced greatly, such as closed lunch rooms, lunch to be eaten in rooms, and in some practices the wearing of surgical scrubs. (Impacts on routine 3) |

| 2 Realigned clinical work | ||

| 2.1 Telehealth | Procedures for conducting consultations via phone or video, rather than face to face. | All practices began using telehealth for many consultations—enabled by changed MBS funding for telehealth (previously limited to rural and remote areas). All practices remained open for face-to-face consultations (usually with almost all GPs on-site). Most GPs provided telehealth from the practice, but some worked from home when isolating or unwell or if they had personal risk factors such as advanced age or chronic disease:

GPs overwhelmingly used phone rather than video:

Receptionists needed to be aware of significantly modified billing schedule. |

| 2.2 Case management chronic illness/care continuity | Procedures for management of patients’ ongoing health conditions. | All practices initially paused: chronic disease management recalls; cervical cancer screening; health checks for 45–49 and 75+ years old:

Different approaches and timing for resuming chronic disease management follow-ups—often financially driven in view of falling practice income:

|

| 3 Practice management | Procedures for coordination between practice staff. | Staff meetings: pre-existing large variation between practices in frequency and attendance:

Major loss in collegiality:

|

CHC, community health centre; GP, general practitioner; MBS, Medical Benefits Schedule; PPE, personal protective equipment.

Keeping staff and patients safe. Once problems sourcing PPE were partially resolved, practices began to prioritise creation of a COVID-19 safe workplace. Clinicians began wearing scrubs, room ventilation and cleaning was improved and physical barriers and isolation areas were introduced. These came with major changes in screening, triage and booking routines. Online appointment booking was paused or amended at all practices—reception staff screened all patients for COVID-19 infection risk by telephone, while informing them about requirements relating to safety, telehealth and billing. These infection control approaches varied between practices.

Realigned clinical work. Telehealth had major impacts on clinical care delivery. Telephone, rather than video, consultations predominated due to GP preferences and some patient technological constraints. There was significant concern about patient unwillingness to attend in person, and GPs often viewed telehealth as inadequate for delivering quality care, especially for systematic chronic disease management (CDM).

Practice management. To limit virus transmission risk, practice staff began communicating differently with each other (see table 4). Face-to-face meetings ceased, replaced by emails, and in some practices, smartphone apps and virtual meetings. Formal practice meetings were mostly held infrequently. POs in the small private practices made decisions to change routines, often unilaterally. GPs became increasingly concerned about losing income due to reduced patient demand and an initial government mandate to bulk bill all telehealth consultations.

Table 4.

Practice meetings and communication

| Practice | Meeting routines | Communication tools | |||

| Pre-COVID | Early chaos | Emerging stability | Second wave | ||

| CHC | Monthly/as required—all staff. | Twice weekly. | Weekly Zoom (open to all staff, most attend, even on days off for some). Increased attendance from prepandemic. | As previous. | Set up WhatsApp group at start of COVID-19 (for general staff communication). |

| SE1 | GPs every 2–3 months, decided by owner. | Weekly Zoom from May 2020. Generated by employed doctor advocacy. | Weekly Zoom—only GPs. | As previous. | WhatsApp group for GPs at start of COVID-19. |

| E | Every 1 or 2 months. | Fortnightly by Zoom; nurses and receptionists not usually included. | No change. | At peak of 2nd wave, no meetings; leadership making all decisions. | Most communication by email. |

| CBD | Monthly. | Weekly, sometimes only GPs, sometimes nurses. Also smaller informal meetings among GPs every morning. | Nurses stopped attending. | As previous. | WhatsApp group prior to COVID-19 but used more often during pandemic. WeChat group added. |

| SE2 | No all-staff meetings—off-site managers only, no GP meetings, reception and nursing team have separate meetings. | 1 GP meeting in March 2020, clinical investigator stepped up to clinical director, started regular meetings of PM, head nurse and medical director. | No change. | No change. | Medical director set up WhatsApp group for GPs in July to communicate changes to protocols, share thoughts, information—informal, not seen as good replacement for meetings. |

| W | Partners meet 1–2 times a month, GPs’ monthly lunch meeting, all staff annual general meeting. | All staff weekly or fortnightly. | No practice-wide meetings since late March 2020. | As previous. | Couple of WhatsApp groups, delegated nurse and doctor inactive during COVID-19. |

CHC, community health centre; GP, general practitioner; PM, practice manager.

Negotiating a second wave (July 2020 to October 2020)

In early July, rapidly increasing cases led to a strict 4-month metropolitan Melbourne lockdown.22 Despite case numbers reaching 700 per day, many participants across the practices felt their earlier changes had prepared them for the challenge. Clinicians became increasingly concerned about missed diagnoses and late presentations:

[A patient has] really deteriorated in the last six weeks. … I’ve had several telephone calls to persuade him to go into hospital, and eventually he did yesterday. I got him to agree to some blood tests… his liver has packed up. And he’s jaundiced and I don’t know if he will survive, but at least he’s gone in. And if he hadn’t have gone in, I would have said, ‘Oh no, what do I do now?’ … He would have died at home. (CHC GP1)

Patients embraced telehealth, causing dilemmas for clinicians in maintaining quality care as a ‘balance’ between bringing patients to a potentially infectious location and dealing with the uncertainties of remote clinical care:

We’ve put all sort of strict guidelines around what we think’s suitable for telehealth and what’s not. So, things like say mental health plans, basic administrative things like repeat scripts…referrals to other specialists… do that over the phone. But as soon as they start saying, ‘I’ve got abdominal pain,’ or, ‘I’ve got this thing on my arm, I’m not sure what it is,’ they’ve got to come in and have an appointment. (SE1 PO)

Three practices began managing COVID-19 testing clinics:

…we took over screening [from the Department of Health, because] They were taking up to two weeks to get a positive result to a patient. …that was a significant increase in workload…. I pretty much worked seven days a week. I think for three months I didn’t have a day off, there were just lots of results coming through, notifications. The time taken to notify one positive result, to notify the Department of Health, could take one staff member two to three hours…. (CHC GP2)

As the lockdown continued, financial pressures from decreased practice income increased. New staff vacancies were unfilled, and staff and clinicians were asked to take annual leave or reduce working hours. The privately owned practices sought to diversify income; training nurses in remote CDM, systematically calling patients for recall (most practices); or providing COVID-19 testing for asymptomatic travellers at one practice (CBD). The corporate’s regional management modified CDM ‘targets’ to increase income. As cases rose, the CHC assumed responsibility for managing the pandemic response at nearby public housing towers, which required significant staffing resources and eventually attracted additional state government funding.

Entering a new normal (November 2020 to February 2021)

Strict lockdown ended in late October 2020 and heralded an uneasy optimism. With new routines embedded, staff reflected on the consequences of the strain of the experience:

We’re all pretty exhausted. And I’ve noticed—especially the past couple of months, I personally have been very, very short with patients. … I don’t indulge anyone at all anymore. I just say straight up this is how we work, you could come, you could not come. That’s it. I’m not going to spend 10 minutes on the phone with you convincing you because I have so much work to do. (CBD R)

Understanding the change

Our data showed that the characteristics of and variations between the practices in the organisation and delivery of clinical care were driven by the health policy environment, local ecology and each practice core and adaptive reserve.10

Health policy environment

While the Australian federal government provided no specific financial support to general practices during the pandemic, the impact was ameliorated by its ‘JobKeeper’ wage subsidy23 and the introduction of MBS payments for telehealth. JobKeeper was only accessed by staff from one practice (CBD), but all made extensive use of telehealth. The federal government’s Primary Health Networks24 distributed some PPE as the months passed, although practices continued to need to source these privately. While practices were aware of, and often attentive to, a steady stream of government, Primary Health Networks and professional organisation advice, shifting guidance with inadequate notice made it difficult to forge a consistent path.

Local ecology

The pandemic’s impact varied across metropolitan Melbourne—neighbourhoods surrounding practices W and CHC had four times as many COVID-19 infections compared with the other practices.25 Practice W’s (federally funded) on-site COVID-19 testing clinic was established prior to the first local infection, and was viewed as critical in keeping the general practice environment ‘safe’. The rising incidence of COVID-19 in public housing towers close to the CHC led to extensive outreach services. The extensive changes adopted by the other practices were unrelated to local infection rates, although the CBD practice created a COVID-19 testing clinic to meet the needs of its overseas worker clientele who were required to obtain COVID-19 tests prior to returning home.

Practice core

The lack of formal external support or meaningful pandemic planning left the private practices internally focused and needing to generate their own solutions to the pandemic challenges. The solutions and their uptake reflected the practice organisational models and their leaders’ internal models.

For example, the structure within SE2’s corporate model (where early decision-making was made by off-site regional managers) compounded local leaders’ frustration and made it difficult for the practice to address the demands of the pandemic.

For all practices, the introduction of MBS telehealth payments eased financial pressures that emerged with patients’ increasing reluctance to seek face-to-face care. This required new routines to manage acute illness, plan prevention and monitor CDM. Nevertheless, as the pandemic continued, financial pressures continued, with most practices reporting a 25%–60% fall in income and adjustments to staffing to offset losses.

Government financial regulations generated some perverse incentives. During the early pandemic phases, government-funded telehealth consultations could not attract copayments. As a result, several of the private practices began to encourage patients to attend the practice for face-to-face consultations, which still attracted private copayments.

Adaptive reserve

Internal motivations were similar between practices. The early preoccupation was with a safe workplace focused on structural changes, modifications to patient flow and an ongoing need for triage. As time passed, work was driven by desires to maintain both financial viability and quality clinical care. Most practice staff were increasingly concerned about their patient cohort’s welfare, especially those with mental health conditions or complex chronic disease.

Leaders were key to adaptive reserve in the four privately owned practices and were critical to the maintenance of services in the CHC and the corporate practice. Within the CHC’s complex external governance structure, management resources were rapidly redirected to the general practice, with decision-making mostly devolved to managers and staff members close to the general practice level.

By contrast, at the four private practices, POs made most of the decisions, often with minimal consultation with nurses, receptionists and contractor doctors:

The practice principals have been taking a lot of unilateral decisions recently and there has not been a doctors’ meeting for quite some time now. They even sent out an email asking for all the discussion to cease as they would be making the decisions from now on. I’m a bit worried it got everyone offside. (Deidentified participant)

Professional roles remained isolated and few leaders sought information from outside their own professional group. Prepandemic hierarchies between the owners and clinical and administrative staff were maintained and sometimes reinforced. Despite needing to ‘take on the lion’s share of the infection control and cleaning and [having] very high risk interactions’ (Deidentified N), nurses were rarely included in decision-making.

The data suggested occasional evolution of leadership approaches. The corporate practice (SE2) began with key decisions being made by the practice regional management team. Practitioners and staff feelings of disempowerment improved when a local leadership team was formed comprising the PM, a senior nurse and a medical lead. However, several changes to routines (such as temperature testing all patients) were later overturned by regional leaders on cost grounds.

In the early months of the pandemic, contractor GPs in one practice felt the practice leadership was not ‘taking it seriously enough’ (Deidentified N). Following a formal presentation of the non-owner GPs’ concerns to management, the practice transformed to become more collaborative, with weekly meetings and extensive use of social media for communication. However, nurses and administrative staff remained isolated from decision-making:

A: No, the weekly meetings are not everyone. They’re just the GPs. They do a Zoom meeting now.

Q: But not with you?

A: No, not with us. So that’s what I’m saying, we just get things told to us in the corridor. (Deidentified N)

Discussion

Despite Melbourne’s pandemic experience being the worst in Australia in 2020, practices were spared the staff deaths or multiple practice closures experienced overseas. The study practices mirrored international transformations of clinical, organisational and infection control routines. As elsewhere, PPE was difficult to access,26 practice income fell27 and practitioners worried about reduced face-to-face consultation28 and the potential impact on patients with chronic health conditions.29

Unanticipated crises, like a pandemic, can uncover the strengths, flexibility and fragility of organisations and the systems in which they are embedded.7 The pandemic acted as a natural experiment of the effectiveness of models of care predominant in Australian general practice. We believe our data emphasise the fragility of the organisational models, financial security and support underpinning Australian primary care.

Models of care

Our study data highlighted the potential of the CHC model to bridge the gap between primary care and public health.30 Victoria’s CHCs incorporate a focus on prevention, health equity and the social determinants of health.31 The combination of the CHC’s community focus and secure state funding helped it meet its mandate of addressing the evolving needs of local communities. By contrast, most of the private practices lacked the structural or organisational ability to go much beyond maintaining basic practice functions. They were isolated, internally preoccupied and, while provided with extensive information, generally left to negotiate the challenges of the pandemic alone. SE2’s remote governance and lack of internal management compounded workforce fragmentation and demoralisation, and made it difficult for the practice to align with evolving demands. Practice W was a partial exception, as its size, active leadership and community connection were reflected in the decision to host a federally funded COVID-19 testing facility.

The relative financial security of the CHC funding model and the explicit links with state health services highlighted the potential of the CHC to address local needs of vulnerable communities. Models similar to CHCs are widespread in North America and have been important in delivering quality care to underserved populations.32 Given the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on vulnerable communities, and the importance of primary care to population health, future health planning should explore the potential for either expanding the coverage of the CHC model or exploring ways to incentivise the incorporation of CHC-like functions into private primary care delivery.

Financial security

As elsewhere,33–35 all our participating practices were financially challenged by the pandemic. A recent survey found that 65% of Australian GPs, particularly in urban and more affluent areas, experienced reduced income in the early months of the pandemic.36 Similar early financial impacts were reported in many other nations,37–39 with losses per full-time equivalent physician in the USA estimated as over $65 000 in 2020. Waitzberg et al observed that dramatically decreased income from patient visits combined with minimal direct governmental control ‘reverses the conventional financial positions of payers and providers and acts as a further hurdle to prioritizing public health’.37

Given the fee-for-service payment model for GPs in private businesses and the CHC, our participants unsurprisingly had a preoccupation with financial security and modifying routines to maintain income and avoid practice closures. This challenge could have been addressed by directed government financial support.

Some degree of practice-directed financial support could be considered in future pandemics. Even relatively small capitated payments from payers (ie, the federal government in Australia) could be used to mitigate losses and keep practices open.40

Leading change at the practice level

It has been suggested that COVID-19 highlights the weak points in systems, but also provides an opportunity for transformation.41 While practices in this study were all able to realign their organisational and clinical routines, transformation was constrained by hierarchical leadership structures, rigid financial models and pervasive professional boundaries.

As others have found, our data identified isolated examples of increased collaboration42 and, at times (especially within the CHC), evidence of visionary, operational and distributed leadership.43 However, overall, our data supported Gerada’s contention that practices can both ‘crave’ for authoritative leaders at times of distress, but also find such approaches to be disempowering.44 Practice models and financing provided minimal incentives for leaders to be attentive to the local environment,16 or open to creating links between organisations.45

Limitations

While data were collected from a range of organisational models, these were within a single Australian metropolitan area in the first year of a moderate COVID-19 pandemic. It is feasible that different routines would have emerged in practices in a different health policy or local environment context, such as rural practices, those not faced by a metropolitan area lockdown, and with no association with a university department of general practice. While it was possible that key routines were not revealed, our external investigators, iterative approach and inclusion of international experts decreased this possibility.

The GP investigators were involved in recruitment and data collection in their practice, and were closely involved in data analysis. Their views are inevitably influenced by their personal experiences of practice dynamics. This adds important insights into practice functioning, but also has the potential to over-ride the views of other practice participants. This possibility is countervailed by two key factors: (1) the vast majority of data analysis, including all coding of data, was undertaken by the social scientists; (2) feedback sessions by practice staff on interim data provided member checking of data validity.

Conclusion

Our study represented a natural experiment of the resilience, financial stability and governance within models of primary care in Australia. We found a fragile primary care sector that struggled to be fit for purpose in dealing with a pandemic. Practice isolation and financial strain were early and pervasive challenges to practice security. Leadership was critical, but many routine changes followed both financial and clinical priorities. Nevertheless, innovations in telehealth, triage and infection management are likely to be long lasting.

The Australian federal government’s 10-year vision for improving primary care46 highlights the importance of leadership at all levels and reconsideration of federal and state responsibilities in supporting general practices. Our findings point to the potential value of models such as the CHC for organising and delivering care to highly vulnerable populations, and to the key role of practice leaders. The significant financial burdens experienced by several practices raise concerns as to the abilities of a purely fee-for-service system to both innovate and manage the critical primary care challenges of a global pandemic.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contributions of Sharon Clifford, project manager, who helped coordinate the study, and John Furler, a clinician at one site.

Footnotes

Twitter: @grantrussell17, @RikiLane, @LizSturgiss

Contributors: GR led the project and is responsible for the overall content as guarantor. GR, EAS, JN, KA, TSS and SH acted as participant investigators. BFC and WLM provided expert advice. JA and RL conducted and coded the interviews and led the data analysis. This paper was written by GR, JA and RL with contributions from TSS, EAS, JN, SH, BFC, WLM and KA. All authors contributed to study design and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

No data are available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (2020-23950). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Hick JL, Biddinger PD. Novel Coronavirus and Old Lessons - Preparing the Health System for the Pandemic. N Engl J Med 2020;382:e55. 2020/05/14. 10.1056/NEJMp2005118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huston P, Campbell J, Russell G, et al. COVID-19 and primary care in six countries. BJGP Open 2020;4. 10.3399/bjgpopen20X101128. [Epub ahead of print: 27 10 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braithwaite J, Tran Y, Ellis LA, et al. The 40 health systems, COVID-19 (40HS, C-19) study. Int J Qual Health Care 2021;33. 10.1093/intqhc/mzaa113. [Epub ahead of print: 20 Feb 2021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boroujeni M, Saberian M, Li J. Environmental impacts of COVID-19 on Victoria, Australia, witnessed two waves of coronavirus. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2021;28:14182–91. 10.1007/s11356-021-12556-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erny-Albrecht K, Bywood P. Corporatisation of general practice – impact and implications. PHCRIS Policy Issue Review 2016:1–53. [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDonald J, Ward B, Lane R, et al. How are co-located primary health care centres integrating care for people with chronic conditions? Int J Integr Care 2017;17:51. 10.5334/ijic.3163 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carmeli A, Schaubroeck J. Organisational Crisis-Preparedness: the importance of learning from failures. Long Range Plann 2008;41:177–96. 10.1016/j.lrp.2008.01.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Plsek PE, Greenhalgh T. Complexity science: the challenge of complexity in health care. BMJ 2001;323:625–8. 10.1136/bmj.323.7313.625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller WL, Crabtree BF, McDaniel R, et al. Understanding change in primary care practice using complexity theory. J Fam Pract 1998;46:369–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yin R. Case study research: Design and methods. 3rd ed. Sage, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Buul LW, Sikkens JJ, van Agtmael MA, et al. Participatory action research in antimicrobial stewardship: a novel approach to improving antimicrobial prescribing in hospitals and long-term care facilities. J Antimicrob Chemother 2014;69:1734–41. 10.1093/jac/dku068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Russell G, Advocat J, Lane R, et al. How do general practices respond to a pandemic? protocol for a prospective qualitative study of six Australian practices. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e046086. 01-Sep-2021. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balasubramanian BA, Chase SM, Nutting PA, et al. Using learning teams for reflective adaptation (ultra): insights from a team-based change management strategy in primary care. Ann Fam Med 2010;8:425–32. 2010. 10.1370/afm.1159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lane R, Russell G, Bardoel EA. When colocation is not enough: a case study of general practitioner super clinics in Australia. Aust J Prim Health. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.NVivo qualitative data analysis software. version 12 2018.

- 16.Miller WL, Crabtree BF, Nutting PA, et al. Primary care practice development: a relationship-centered approach. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8 Suppl 1:S68–79. May 1, 2010. 10.1370/afm.1089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glaser BG. The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Soc Probl 1965;12:436–45. 10.2307/798843 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Russell G, Advocat J, Geneau R, et al. Examining organizational change in primary care practices: experiences from using ethnographic methods. Fam Pract 2012;29:455–61. 10.1093/fampra/cmr117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strauss AL. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2nd ed.. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldana J, Oaks T, ed. Qualitative data analysis : a methods sourcebook. Third edition. Califorinia: SAGE Publications, Inc, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:349–57. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Australian Broadcasting Commission . Melbourne placed under stage 4 coronavirus lockdown, stage 3 for rest of Victoria as state of disaster declared. ABC. accessed 13/02/2022, Melbourne placed under stage 4 coronavirus lockdown, stage 3 for rest of Victoria as state of disaster declared.

- 23.Australian Government: Treasury. JobKeeper Payment . Commonwealth of Australia. Available: https://treasury.gov.au/coronavirus/jobkeeper [Accessed 13/02/2022].

- 24.Australian Government: Department of Health . Primary health networks. Commonwealth of Australia. Available: https://www.health.gov.au/initiatives-and-programs/phn [Accessed 12/02/2022].

- 25.Australian Broadcasting Commission . Postcode data on coronavirus cases reveals Victoria’s COVID-19 hotspots. 12/02/2022, Postcode data on coronavirus cases reveals Victoria’s COVID-19 hotspots.

- 26.Alsnes IV, Munkvik M, Flanders WD, Oyane N, et al. How well did Norwegian general practice prepare to address the COVID-19 pandemic? Fam Med Community Health 2020;8. 10.1136/fmch-2020-000512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roehr B. Covid-19 is threatening the survival of US primary care. BMJ 2020;369:m2333. 10.1136/bmj.m2333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu Z, Fan J, Ding J, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on primary care general practice consultations in a teaching hospital in Shanghai, China. Front Med 2021;8:642496. 10.3389/fmed.2021.642496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rawaf S, Allen LN, Stigler FL, et al. Lessons on the COVID-19 pandemic, for and by primary care professionals worldwide. Eur J Gen Pract 2020;26:129–33. 10.1080/13814788.2020.1820479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Russell GM. Is prevention unbalancing general practice? Med J Aust 2005;183:104–5. 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2005.tb06942.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Powell Davies G, McDonald J, Jeon Y, et al. A narrative synthesis of models of integrated primary care centres/polyclinics, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagel DA, Keeping-Burke L, Pyrke RJL, et al. Frameworks for evaluation of community health centers' services and outcomes: a scoping review protocol. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep 2019;17:451–60. 10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilson G, Currie O, Bidwell S, et al. Empty waiting rooms: the New Zealand general practice experience with telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic. N Z Med J 2021;134:89–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Filippi MK, Callen E, Wade A. COVID-19’s Financial Impact on Primary Care Clinicians and Practices. J Am Board Fam Med. May 2021;34:489–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krist AH, DeVoe JE, Cheng A, et al. Redesigning primary care to address the COVID-19 pandemic in the midst of the pandemic. Ann Fam Med 2020;18:349–54. 10.1370/afm.2557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scott A. The impact of COVID-19 on GPs and non-GP specialists in private practice. Melbourne Institute of Applied Economic and Social Research 2020:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waitzberg R, Quentin W, Webb E, et al. The structure and financing of health care systems affected how providers Coped with COVID-19. Milbank Q 2021;99:542–64. 10.1111/1468-0009.12530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kippen R, O'Sullivan B, Hickson H, et al. A national survey of COVID-19 challenges, responses and effects in Australian general practice. Aust J Gen Pract 2020;49:745–51. 10.31128/AJGP-06-20-5465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roth C, Breckner A, Moellinger S, et al. Beliefs and practices among primary care physicians during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Baden-Wuerttemberg (Germany): an observational study. BMC Fam Pract 2021;22:86. 10.1186/s12875-021-01433-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Basu S, Phillips RS, Phillips R, et al. Primary care practice finances in the United States amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Aff 2020;39:1605–14. 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Friedman TL. We Need Great Leadership Now, and Here’s What It Looks Like. New York Times. April 21, 2020. Available: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/21/opinion/covid-dov-seidman.html?referringSource=articleShare

- 42.Renaa T, Brekke M. Restructuring in a GP practice during the COVID-19 pandemic - a focus-group study. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. Feb 2 2021;141(2)Driftsomlegging ved et fastlegekontor under covid-19-pandemien - en fokusgruppestudie. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Donahue KE, Halladay JR, Wise A, et al. Facilitators of transforming primary care: a look under the hood at practice leadership. The Annals of Family Medicine 2013;11:S27–33. 10.1370/afm.1492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gerada C. Reflections on leadership during the Covid pandemic. Postgrad Med 2021;133:717–20. 10.1080/00325481.2021.1903218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Westfall JM, Liaw W, Griswold K, et al. Uniting public health and primary care for healthy communities in the COVID-19 era and beyond. J Am Board Fam Med 2021;34:S203–9. 10.3122/jabfm.2021.S1.200458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Commonwealth of Australia (Department of Health) . Consultation Draft - Future focused primary health care: Australia’s Primary Health Care 10 Year Plan 2022-2032. Commonwealth of Australia [Accessed 12/02/2022].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No data are available.