Abstract

Null cyclic β-1,2-glucan synthetase mutants (cgs mutants) were obtained from Brucella abortus virulent strain 2308 and from B. abortus attenuated vaccinal strain S19. Both mutants show greater sensitivity to surfactants like deoxycholic acid, sodium dodecyl sulfate, and Zwittergent than the parental strains, suggesting cell surface alterations. Although not to the same extent, both mutants display reduced virulence in mice and defective intracellular multiplication in HeLa cells. The B. abortus S19 cgs mutant was completely cleared from the spleens of mice after 4 weeks, while the 2308 mutant showed a 1.5-log reduction of the number of brucellae isolated from the spleens after 12 weeks. These results suggest that cyclic β-1,2-glucan plays an important role in the residual virulence of the attenuated B. abortus S19 strain. Although the cgs mutant was cleared from the spleens earlier than the wild-type parental strain (B. abortus S19) and produced less inflammatory response, its ability to confer protection against the virulent strain B. abortus 2308 was fully retained. Equivalent levels of induction of spleen gamma interferon mRNA and anti-lipopolysaccharide (LPS) of immunoglobulin G2a (IgG2a) subtype antibodies were observed in mice injected with B. abortus S19 or the cgs mutant. However, the titer of anti-LPS antibodies of the IgG1 subtype induced by the cgs mutant was lower than that observed with the parental S19 strain, thus suggesting that the cgs mutant induces a relatively exclusive Th1 response.

Brucella abortus is an intracellular pathogen that causes abortion in bovines and can infect humans. Abortion in cattle is the consequence of the tropism that the bacterium has for the placenta of pregnant animals, in which it multiplies intracellularly (10). Brucellosis in humans is primarily a disease of the reticuloendothelial system, in which the bacteria multiply inside the phagocytic cell; the intermittent release of bacteria from the cells into the bloodstream causes undulant fever (17, 29). Brucellosis does not spread among humans; consequently, eradication of the disease from the natural reservoirs, cattle, pigs, sheep, goats, and other susceptible animals, will lead to elimination of human infection. In regions with high prevalence of the disease, the only way of controlling and eventually eradicating this zoonosis is by vaccination of all susceptible hosts and elimination of infected animals.

Vaccination represents an important tool for the control of bovine brucellosis. One of the most used vaccines is the attenuated strain B. abortus S19 obtained spontaneously from the virulent strain B. abortus 2308 (24, 25, 26, 29). Live attenuated B. abortus S19 has served for many years as an effective vaccine to prevent brucellosis in cattle (8, 18). The genetic defect that leads to attenuation of this strain has not yet been defined. B. abortus S19 has lost some essential unknown mechanism of virulence. Despite this fact, the vaccinal strain conserves some degree of virulence, being pathogenic for humans (37), and produces abortion and persistent infection in adult vaccinated cattle. Vaccination with B. abortus S19 is used only for sexually immature animals (25, 26). Brucella, Agrobacterium, and Rhizobium belong, according to 16S rRNA sequences, to the α-2 subgroup of the Proteobacteria (16), and comparative studies of the virulence genes of the plant pathogen Agrobacterium and the endosymbiotic Rhizobium might give us new insights on Brucella virulence factors. The Brucella two-component regulatory system (30) is highly similar to the two-component regulatory system ChvG-ChvI of Agrobacterium tumefaciens (5) and ExoS-ChvI of Rhizobium meliloti (6). These two-component regulatory genes are equivalent to Salmonella PhoP-PhoQ (31) and Bordetella bronchiseptica BvgA-BvgS systems (32). In all these bacteria, the two-component sensory systems are involved in controlling virulence or, in the case of Rhizobium, in nodule invasion. B. abortus bvrS bvrR mutants display reduced invasiveness and virulence (22, 30).

A Brucella virB operon highly homologous to the A. tumefaciens virB operon was identified in Brucella suis (20) and in B. abortus (28). A B. abortus virB10 mutant lost the ability to multiply in HeLa cells and was not recovered from the spleens of infected BALB/c mice (28). The same results were obtained with a B. suis virB10 mutant (20), thus demonstrating that in Brucella, as in Agrobacterium, the virB operon is involved in virulence.

In a recent report, a highly conserved B. abortus homologue of the R. meliloti bacA gene, which encodes a putative cytoplasmic membrane transport protein required for symbiosis, was identified (14). The B. abortus bacA mutant shows decreased survival in macrophages and reduced virulence in BALB/c mouse infection (14).

Brucella, like Agrobacterium and Rhizobium, produces cyclic β-1,2-glucans (34). chvB in A. tumefaciens and ndvB in R. meliloti were identified as the genes coding for the cyclic β-1,2-glucan synthetase (12). We recently reported that in Brucella the biosynthesis of cyclic β-1,2-glucan proceeds by the same mechanism as in Rhizobium and Agrobacterium (4). The cyclic glucan synthetase (Cgs) acts as an intermediate during the synthesis of the cyclic β-1,2-glucan (12). So far, cyclic β-1,2-glucan has been described only for bacteria that interact with plants as either pathogens or endosymbionts. This glucan is required for effective nodule invasion in symbiotic nitrogen-fixing R. meliloti and for crown gall tumor induction in A. tumefaciens (3). Agrobacterium cyclic β-1,2-glucan mutants have several altered cell surface properties including loss of motility due to a defective assembly of flagella and increased sensitivity to certain antibiotics and detergents (3).

The B. abortus S19 gene that codes for a cyclic β-1,2-glucan synthetase has previously been identified and sequenced (12). Brucella cgs, Agrobacterium chvB, and Rhizobium ndvB are interchangeable genes. Agrobacterium or Rhizobium cyclic β-1,2-glucan mutants can be complemented by the Brucella cgs genes, indicating that their functions are highly conserved (11, 12). A preliminary characterization of B. abortus S19 cgs mutants showed that they had reduced survival in BALB/c mouse spleen tissues, thus suggesting that this glucan might be a virulence factor (12). In this study, we examined the virulence of B. abortus cgs mutants in mice and their intracellular replication in HeLa cells. The protection induced in mice by a B. abortus S19 cgs mutant against a challenge with the virulent strain B. abortus 2308 was also evaluated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Brucella strains were grown in Brucella agar (BA) (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.). Escherichia coli strains were grown in Luria broth. Fuchsin, sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), Triton X-100, Zwittergent 316, and deoxycholic acid (DOC) sensitivity tests were carried out as previously described (1, 30). The absence of smooth-to-rough dissociation was checked by testing the sensitivity to smooth-specific phages (Tb, Wb, and Iz) (1).

TABLE 1.

Bacteria and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Phenotypea and/or genotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| B. abortus 2308 | Virulent, field isolated; wild type, Nalr, erythritolr | 25 |

| B. abortus S19 | Vaccine strain, Nalr, erythritols; naturally occurring derivative of B. abortus 2308 | 25 |

| B. abortus RB51 | Vaccine strain, stable rough mutant | 27 |

| BAI129 | B. abortus S19 cgs mutant; Tn3-HoHo 1::chromosome; Ampr | 12 |

| BvI129 | B. abortus 2308 cgs mutant; Tn3-HoHo 1::chromosome; Ampr | This study |

| BAI129(pBA19) | B. abortus S19 cgs mutant with cosmid pBA19; Ampr Tcr | This study |

| BvI129(pBA19) | B. abortus 2308 cgs mutant with cosmid pBA19; Ampr Tcr | This study |

| BAI129(pCD523) | B. abortus S19 cgs mutant with cosmid; pCD523; Ampr Tcr | 11 |

| BvI129(pCD523) | B. abortus 2308 cgs mutant with cosmid; pCD523; Ampr Tcr | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBA19 | pVK102 containing B. abortus S19 cgs gene; Tcr | 12 |

| pCD523 | pLAFR1 containing A. tumefaciens chvB gene; Tcr | 9 |

Nalr, nalidixic acid resistance; Ampr, ampicillin resistance; Tcr, tetracycline resistance.

HeLa cell culture and infection assay.

HeLa cells were grown at 37°C in 5% CO2 atmosphere in minimal essential medium (Gibco, Paisley, Scotland) supplemented with 5 mM glutamine and 5% fetal calf serum. Infection of cells with different Brucella strains was performed as previously described (22, 28).

Construction of B. abortus β-1,2-glucan synthetase mutant and genetic complementation.

Construction of B. abortus strains was carried out by gene replacement of the wild-type cgs gene with a Tn3-HoHo 1 mutated gene (12) (strain BAI129). Confirmation of transposon position was carried out by PCR and Southern blot hybridization. For genetic complementation of cgs mutants, plasmid pCD523 containing the A. tumefaciens chvB gene (9) or plasmid pBA19 containing the B. abortus cgs gene (12), were introduced in strains BAI129 or BvI129 by biparental mating using E. coli S17.1 as the donor strain (7, 12). Complemented B. abortus cgs mutants are described in Table 1.

Pathogenicity in mice.

Nine-week-old female BALB/c mice were injected intraperitoneally with 0.2 ml of a suspension containing the appropriate number of viable brucellae. Stock cultures were grown for 48 h on BA plates, and cells were suspended in sterile 0.15 M NaCl and adjusted turbidimetrically to the selected concentration. The exact bacterial concentration was calculated retrospectively by viable counts. At selected times postinfection, groups of five mice were bled by cardiac puncture and sera were pooled and held frozen at −20°C until use. Mice were killed by cervical dislocation. Spleens were homogenized in 5 ml of 0.15 M NaCl, serially diluted, and plated by triplicate on BA plates with the appropriate antibiotic (15).

Vaccination and evaluation of protection after challenging with virulent strain 2308.

Nine-week-old BALB/c mice were vaccinated with 104 CFU of B. abortus S19 wild type or B. abortus S19 BAI129 cgs mutant (12). At 8 weeks postvaccination, no bacteria were isolated from the spleens of animals infected with S19 or BAI129 and animals were challenged intraperitoneally with different doses of B. abortus virulent strain 2308. One week after challenge, five animals per treatment were killed the numbers of viable Brucella recovered from the spleens and the weights of the spleens were determined as described (15). In order to distinguish strain S19 from strain 2308, counts were carried out on BA plates with 0.01% erythritol as previously described (15).

Semiquantitation of IFN-γ and IL-4 mRNA in spleens of vaccinated mice.

BALB/c mice injected with 104 CFU of B. abortus S19 or the B. abortus S19 cgs mutant were sacrificed after 4 or 8 days, and total RNA was extracted from spleens with TRIzol reagent (GIBCO BRI, Gaithersburg, Md.) as previously described (21). Concentration and purity of extracted RNA were determined by determining the A260 and the A260/A280 ratio. Five micrograms of RNA were reverse transcribed using a commercial kit (Superscript II RT, GIBCO BRL) with a 12- to 18-mer deoxy-T oligonucleotide primer. Quantitation of reverse-transcribed mRNA by PCR was carried out as described previously (21). Plasmid pMus (kindly provided by D. Shire and F. Pitossi) harboring the same primer sequences for the amplification of several murine cytokines and some housekeeping mRNAs was used as a competitive fragment. The primer sequences used were as follows: for β2-microglobulin sense, TGACCGGCTTGTATGCTATC; for β2-microglobulin antisense, CAGTGTGAGCCAGGATATAG; for gamma interferon (IFN-γ) sense, GCTCTGAGACAATGAACGCT; for IFN-γ antisense, AAAGAGATAATCTGGCTCTGC; for interleukin-4 (IL-4) sense, TCGGCATTTTGAACGAGGTC; and for IL-4 antisense, GAAAAGCCCGAAAGAGTCTC. The expected sizes of the PCR products were 222 bp for β2-microglobulin, 227 bp for IFN-γ, and 216 bp for IL-4. The concentration of β2-microglobulin in each sample was determined to check reverse-transcription (RT) efficiency and the accuracy of the determination of RNA concentration. For semiquantitation of IL-4 and IFN-γ mRNA, 5 × 104 molecules of pMus were coamplified in each PCR in the presence of 3 μCi of [α-32P]dCTP. The separation of amplicons was accomplished on agarose gel (1.2%) in Tris borate buffer in the presence of ethidium bromide. The bands of the gel were inspected at 365 nm and excised, and radioactivity was counted in a liquid scintillator. For each amplification, the ratio of counts per minute of cellular amplicon to counts per minute of standard amplicon was calculated. Each individual sample was amplified by PCR at least twice to exclude casual errors. Spleen RNA samples were obtained from three mice subjected to the same treatment and analyzed separately.

Determination of antibody titers by ELISA and KELA.

Antibody titers against B. abortus lipopolysaccharide (LPS) were measured in an indirect, computer-assisted kinetics-based enzyme-linked assay (KELA), as described by Jimenez de Bagues et al. and Winter et al. (13, 36). The indirect enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to measure antibodies against Brucella LPS in the sera of mice was performed as described by Nielsen et al. (19) with some modification (7).

TLC of cyclic β-1,2-glucan and PAGE of membrane proteins.

Cyclic β(1-2) glucans were extracted by the ethanol method (70% ethanol for 1 h at 37°C) from cell pellets of the different strains. Ethanolic extracts were concentrated and submitted to thin-layer chromatography (TLC) as described previously (4). SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) of membrane proteins and fluorography were performed as previously described (4, 12).

Western blotting.

SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis of LPS O antigen were performed as described by Comerci et al. (7). Whole-cell lysates were solubilized in Laemmli buffer at 100°C, electrophoresed by SDS–12% PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose filters. The filters were reacted with M84 anti-O chain monoclonal antibody (19) (kindly provided by K. Nielsen) diluted 1:5,000 and incubated with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Sigma Chemicals Co., St. Louis, Mo.) diluted 1:10,000. Peroxidase activity was detected by the ECL Western blotting kit from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech.

Statistical analysis.

Differences between the means of experimental and control groups were analyzed using the Student t test. Differences were considered significant at P values of <0.05.

RESULTS

Characterization of B. abortus cgs mutants.

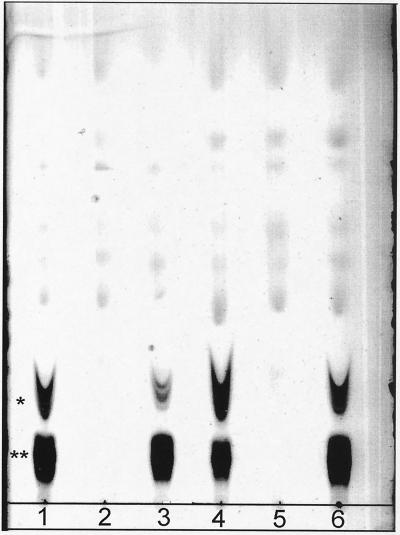

The B. abortus 2308 cgs mutant (strain BvI129) and the B. abortus S19 cgs mutant (strain BAI129) were obtained by targeted insertional mutagenesis as described in Materials and Methods. Both mutants were complemented with plasmid pBA19 containing the B. abortus cgs gene or with plasmid pCD523 containing the A. tumefaciens chvB gene. Some of the phenotypic characteristics of the mutants and complemented strains are shown in Table 2. B. abortus cgs mutants do not form cyclic β-1,2-glucan, and the synthesis was restored by plasmid pBA19 (Fig. 1 and Table 2). Complementation of β-1,2-glucan synthesis of cgs mutants was also achieved with plasmid pCD523, which contains the Agrobacterium cyclic β-1,2-glucan synthetase gene (11), thus indicating that Agrobacterium Cgs is also active in the Brucella background. Brucella cgs mutants did not grow in media containing DOC, SDS, Zwittergent, or fuchsin (Table 2), suggesting that the lack of the Cgs membrane protein or the inability to produce cyclic β-1,2-glucan determines a major membrane defect that affects susceptibility to these compounds. All these inhibitions were relieved when the mutants were complemented with Agrobacterium chvB or Brucella cgs genes.

TABLE 2.

Phenotypic characterization of B. abortus strains

| Characteristic | Result for B. abortus strain:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S19 | BAI129 | BAI129 (pBA19)a | 2308 | BvI129 | BvI129 (pBA19)a | |

| β (1-2) Glucanb | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| 316-kDa proteinc | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| Fuchsind | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| DOCd | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| Zwittergentd | + | − | + | + | − | + |

| SDSd | + | − | + | + | − | + |

Strains BAI129 and BvI129 were complemented with plasmid pBA19.

The presence of β(1-2)glucan was determined by TLC of 70% ethanol extract.

A 316-kDa protein was detected by SDS-PAGE as described in Materials and Methods.

Sensitivity to DOC (0.4 mg/ml), Zwittergent (20 μg/ml), SDS (20 μg/ml), and fuchsin (20 μg/ml) assays were carried out as previously described (1).

FIG. 1.

TLC of cyclic β-1,2-glucans accumulated by different B. abortus strains. Cyclic β-1,2-glucans were extracted and submitted to TLC as described in Materials and Methods. Lanes: 1, B. abortus 2308; 2, B. abortus 2308 cgs mutant (BvI129 strain); 3, B. abortus strain BvI129 complemented with plasmid pBA19; 4, B. abortus S19; 5, B. abortus S19 cgs mutant (BAI129 strain); 6, B. abortus strain BAI129 complemented with plasmid pBA19. ∗ and ∗∗, migration of charged and neutral B. abortus cyclic β-1,2-glucans, respectively.

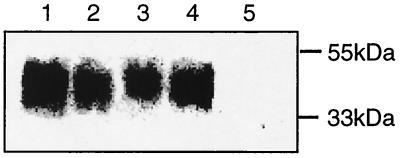

The O antigen transfer to the outer membrane of the cgs mutants was demonstrated by studying sensitivity to three different lytic phages that are known to recognize the O chain of the Brucella LPS (phages Tb, Wb, and Iz) and resistance to one phage that recognizes rough strains (phage Rc) (1). The presence of the O chain in cgs mutants was confirmed by Western blot analysis using monoclonal antibody against the Brucella LPS O antigen (Fig. 2) (19).

FIG. 2.

Western blot of different B. abortus strains. Whole-cell lysates of different B. abortus strains were electrophoresed and transferred, and LPS O antigen was detected as described in Materials and Methods. Lanes: 1, B. abortus 2308 (wild-type strain); 2, B. abortus 2308 BvI129 (cgs mutant); 3, B. abortus S19 (vaccinal strain); 4, B. abortus S19 BAI129 (cgs mutant); 5, B. abortus RB51.

B. abortus cgs mutants have reduced virulence in mice.

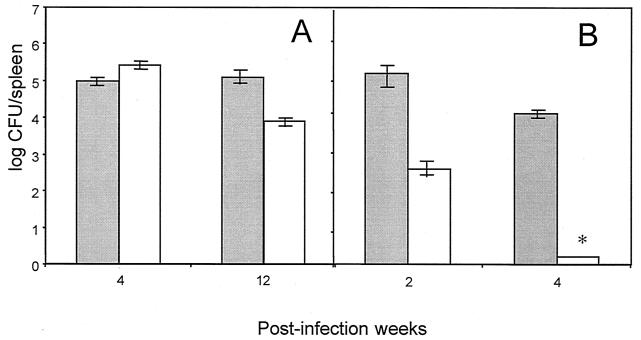

The recovery of B. abortus 2308 and B. abortus S19 cgs mutants (strains BvI129 and BAI129) from the spleens of mice was studied as described in Materials and Methods. Twelve weeks postinfection, the persistence of the B. abortus 2308 cgs mutant (strain BvI129) in the spleens of mice inoculated with 104 CFU per mouse was reduced by 1.5 logs (P < 0.01) compared to the parental wild-type strain (Fig. 3A), while the B. abortus 2308-infected mice remained relatively at the same value at 4 and 12 weeks.

FIG. 3.

Brucella persistence in spleens of mice inoculated with different strains of B. abortus. Mice were inoculated intraperitoneally as described in Materials and Methods with 104 CFU of B. abortus. (A) Shaded bars, B. abortus 2308 (wild-type strain); open bars, B. abortus 2308 BvI129 (cgs mutant). (B) Shaded bars, B. abortus S19 (vaccinal strain); open bars, B. abortus S19 BAI129 cgs mutant. At different times postinfection (2, 4, or 12 weeks) five mice per group were killed and their spleens were removed. The numbers of CFU in spleen tissues were determined as indicated in Materials and Methods.

It can be seen in Fig. 3B that at the same infection dose no B. abortus S19 cgs mutant was recovered from the spleens after 4 weeks. These results indicate that the persistence of B. abortus in mouse spleens is reduced by the cgs mutation, although the effect was more drastic in the attenuated B. abortus S19 strain. The time of clearance of B. abortus S19 cgs mutant depends on the doses (Table 3); even when the initial dose was as high as 7 × 108 CFU/animal, the recovery from the spleen after 4 weeks was reduced by 3 logs compared to the parental wild-type strain (Table 3), thus suggesting that this gene might code for a function that is required, but not sufficient, for virulence.

TABLE 3.

Recovery of B. abortus S19 and B. abortus S19 cgs mutant from the spleens of BALB/c micea

| Dose (CFU) | Time (wks) | Log CFU/spleen inoculated with:

|

Wt (mg) of spleen inoculated with:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S19 | BAI129 | BAI129(pBA19) | S19 | BAI129 | BAI129(pBA19) | ||

| 7 × 108 | 2 | 7.04 ± 0.04 | 5.56 ± 0.19 | 7.11 ± 0.08 | 993 ± 21 | 668 ± 13 | 1,140 ± 44 |

| 4 | 5.98 ± 0.06 | 3.19 ± 0.01 | 5.00 ± 0.07 | 409 ± 13 | 189 ± 8 | 392 ± 32 | |

| 5 × 106 | 2 | 6.88 ± 0.05 | 5.70 ± 0.09 | NDb | 750 ± 33 | 131 ± 7 | ND |

| 4 | 6.98 ± 0.04 | 1.70 ± 0.01 | ND | 564 ± 12 | 104 ± 7 | ND | |

| 103 | 2 | 6.2 ± 0.02 | 1.9 ± 0.02 | ND | 102 ± 11 | 90 ± 10 | ND |

| 4 | 5.1 ± 0.05 | 0 | ND | 115 ± 12 | 87 ± 9 | ND | |

Mice inoculated with 7 × 108 CFU of B. abortus cgs mutant complemented with plasmids pBA19 or pCD523 showed values not statistically different from those observed with the wild-type parental strain. Mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with different doses of B. abortus S19 or B. abortus BAI129 cgs mutant. At different times postinfection, five mice were killed and their spleens were processed as described in Materials and Methods. The mean spleen weight for noninfected mice was 90 ± 10 mg. Bacterial doses were calculated retrospectively. Results are means ± standard errors of values obtained in triplicate.

ND, not determined.

Complementation of B. abortus cgs mutants with plasmid pBA19 or pCD523 restored to wild-type levels the numbers of Brucella organisms isolated from spleens 4 weeks postinfection (Table 3), thus suggesting that Cgs is responsible for persistence in the spleen and that the Agrobacterium gene is correctly expressed in the Brucella background.

Induction of splenomegaly.

As shown in Table 3, B. abortus S19 induces a dose-dependent transient splenomegaly as a consequence of inflammatory response. At all the tested doses, B. abortus S19 cgs mutant induced a reduced response compared to that of the wild-type strain. Complementation of cgs mutant with plasmids pBA19 or pCD523 restored the induction of splenomegaly (Table 3). The pathogenic B. abortus strain 2308 at infection doses of 104 CFU per animal induced a threefold increase in spleen weight 2 weeks postinfection (225 ± 25 mg [mean ± standard deviation]) which persisted after 12 weeks (249 ± 60 mg). Although the numbers of bacteria recovered from spleens of mice infected with wild-type strains and from those infected with cgs mutant strains were not significantly different, no induction of splenomegaly was observed with the B. abortus 2308 cgs mutant at 2 weeks postinfection (77 ± 30 mg). At 12 weeks postinfection the splenomegaly increased twofold (170 ± 27).

These results suggest a correlation between the presence of cyclic β-1,2-glucan and/or Cgs protein and the induction of spleen inflammatory response in mice.

HeLa cells infection.

B. abortus is able to infect and multiply inside HeLa cells. The infection process has two phases, invasion and replication. The invasion phase (0 to 8 h postinfection) is a period during which Brucella enters into the cells but does not multiply (28). During the replication phase, Brucella organisms reach the rough endoplasmic reticulum and start to replicate, causing no cytopathological cell signs (22).

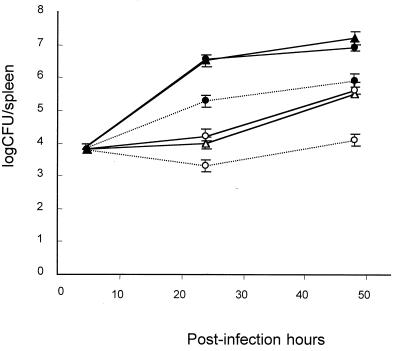

It is shown in Fig. 4 that 4 h postinfection the same numbers of intracellular bacteria were recovered from cells inoculated with B. abortus 2308, B. abortus S19, and their respective cgs mutants. These results indicate that the absence of cyclic glucan does not affect cell invasion. After 4 h, virulent B. abortus strain 2308 started multiplying exponentially, reaching 1.7 × 107 CFU at 48 h (Fig. 4). The B. abortus 2308 cgs mutant (strain BvI129) displayed a lower rate of intracellular replication than the wild-type parental strain, reaching 9 × 105 CFU at 48 h (Fig. 4). The attenuated B. abortus strain S19 has an intracellular rate of replication similar to that observed with the B. abortus 2308 cgs mutant BvI129, reaching a similar number (3.5 × 105 CFU) at 48 h (Fig. 4). On the other hand, the B. abortus S19 cgs mutant strain BAI129 multiplies at a very low rate, reaching 1.2 × 104 CFU at 48 h (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Intracellular replication of different strains of B. abortus. HeLa cells were inoculated with 5 × 107 CFU of different strains of B. abortus. After 2 h of incubation at 37°C, cells were washed and streptomycin and gentamicin were added as described in Materials and Methods. Numbers of CFU were determined at the indicated times. Each determination is the average of two independent experiments carried out in duplicate. In all cases, the standard error for each point was less than 5%. Symbols: ●——●, B. abortus 2308; ●----●, B. abortus BvI129 (cgs mutant strain); ○——○, B. abortus S19; ○····○; B. abortus BAI129 (cgs mutant strain); ▴——▴, B. abortus BvI129 (pBA19); ▴----▴, B. abortus BAI129(pBA19).

The intracellular replication of BvI129 and BAI129 cgs mutants was restored by plasmid pBA19 (Fig. 4). These results suggest that the cyclic glucan and/or the Cgs protein is required for normal B. abortus intracellular replication in both the pathogenic 2308 strain and the attenuated S19 strain.

B. abortus BAI129 as vaccine.

One of the drawbacks of the vaccine strain B. abortus S19 is that in cattle, mice, and humans it displays some degree of virulence, causing abortion in pregnant cows (10). In order to determine if the less pathogenic B. abortus BAI129 (cgs mutant) remains immunogenic, experiments of protection in mice were carried out. The B. abortus S19 cgs mutant strain BAI129 protected mice against a challenge with the virulent strain B. abortus 2308 to the same extent as the wild-type B. abortus S19 strain (Table 4). This indicates that this mutant, although having reduced virulence and impaired ability to multiply intracellularly in HeLa cells, completely retained the ability to protect mice. As shown in Table 4, protection experiments with B. abortus S19 or B. abortus BAI129 were carried out and the animals were challenged with different doses of the wild-type pathogenic strain. No significant differences were observed between the B. abortus S19 wild type and the cgs mutant at any dose.

TABLE 4.

Protection against B. abortus 2308 provided to BALB/c mice after vaccination with B. abortus S19 or the B. abortus BAI129 cgs mutanta

| Challenge dose (CFU) | Vaccination strainb | Log CFU/spleen 1 wk p.i.c (mean ± SD) | Spleen wt (g) (mean ± SD) | Protectiond |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 109 | None | 8.60 ± 0.04 | NDe | 0.00 |

| S19 | 6.44 ± 0.03 | 0.51 ± 0.02 | 2.16 | |

| BAI129 | 6.79 ± 0.03 | 0.44 ± 0.03 | 1.91 | |

| 107 | None | 6.27 ± 0.10 | 0.34 ± 0.03 | 0.00 |

| S19 | 3.52 ± 0.01 | 0.19 ± 0.05 | 3.05 | |

| BAI129 | 2.99 ± 0.56 | 0.14 ± 0.01 | 3.29 | |

| 105 | None | 6.55 ± 0.05 | 0.20 ± 0.04 | 0.00 |

| S19 | 0f | 0.18 ± 0.04 | 6.55 | |

| BAI129 | 0f | 0.13 ± 0.04 | 6.55 |

Mice were inoculated intraperitoneally with 104 CFU of B. abortus S19 or B. abortus BAI129. One month postvaccination, mice were challenged with different doses of B. abortus 2308. Eight week later, the animals were killed and their spleens were removed and weighed. Spleens were processed as described in Materials and Methods.

Vaccination doses were 104 CFU.

p.i., postinfection

Protection = log CFU of control non-vaccinated mice − log CFU of vaccinated mice (15).

ND, not determined.

Detection limit was 102 CFU.

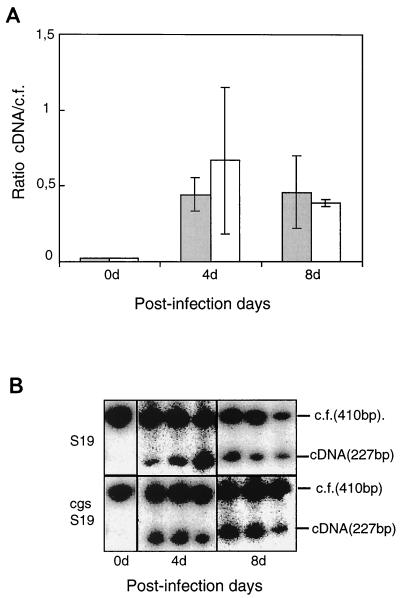

Quantitation of IFN-γ and IL-4 mRNA in spleens of infected mice.

BALB/c mice were infected with 104 CFU of B. abortus S19 or the B. abortus S19 cgs mutant and at different postinfection times spleens were removed and total RNA was extracted. Quantitation of IFN-γ and IL-4 mRNA was carried out by RT-PCR as described in Materials and Methods. At 4 days postinfection B. abortus S19 or the B. abortus S19 cgs mutant induced in the spleen an accumulation of IFN-γ mRNA that persisted after 8 days (Fig. 5). No induction of IL-4 mRNA was detected at any time with the mutant or the parental S19 strain (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Quantitation of IFN-γ in spleen of infected mice. BALB/c mice were infected with 104 CFU of B. abortus S19 (shaded bars) or B. abortus cgs mutant (open bars). At different times postinfection, spleens were removed and total RNA was extracted and analyzed separately. (A) Quantitation of IFN-γ mRNA was carried out by RT-PCR as described in Materials and Methods. Error bars indicate standard deviations. (B) Agarose gel of the amplicon products from three mice at each time point. After the gel dried, radioactivity was detected by autoradiograph.

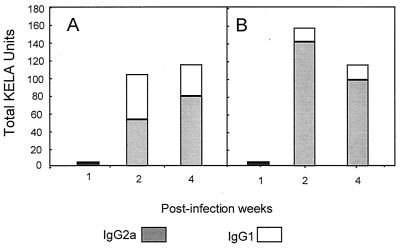

Patterns of immunoglobulins elicited in mice by B. abortus S19 and B. abortus BAI129 cgs mutant.

The Th1 cytokine IFN-γ promotes switching to IgG2a, whereas IL-4, a product of Th2 cells, promotes switching to IgG1 and IgE (25, 37). An ELISA for IgG1 and IgG2a was carried out to estimate the Th1/Th2 ratio of host immune response to B. abortus S19 and the B. abortus S19 cgs mutant. Figure 6 shows the anti-LPS antibody titers of serum pools obtained from animals infected with 7 × 108 CFU of B. abortus S19 and the B. abortus S19 cgs mutant BAI129 (Fig. 6A and B, respectively) at different postinfection times. It is observed that BAI129 induced a switching to IgG2a with low levels of IgG1, thus confirming a good IFN-γ response and the absence of IL-4 induction (see “Quantitation of IFN-γ and IL-4 mRNA in spleens of infected mice” above) (23, 35).

FIG. 6.

Pattern of immunoglobulins elicited by B. abortus S19 or the B. abortus BAI129 cgs mutant. KELA results for pooled sera from five mice inoculated with 7 × 108 CFU of B. abortus S19 (A) or B. abortus BAI129 (B) obtained at 1, 2, or 4 weeks postinfection are shown. IgG1 plus IgG2a give total KELA units.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we showed that the absence of cyclic β-1,2-glucan in B. abortus is associated with a reduction of virulence in mice and defective intracellular multiplication in HeLa cells.

B. abortus cgs mutants display increased sensitivity to surfactant compounds. This association between reduction of virulence and sensitivity to surfactants was also observed in B. abortus mutants in the two-component regulatory system (30). With cgs mutants no correlation was observed between sensitivity to surfactants and virulence. B. abortus 2308 and S19 cgs mutants have the same sensitivity to DOC, SDS, and Zwittergent. However, in strain 2308 the effect on attenuation of virulence was lower than that observed with the attenuated vaccinal S19 strain, even though this may be the result of multiple defects in S19.

Some reports suggest that the presence of cyclic β-1,2-glucan in the bacterial periplasm may stabilize membrane proteins against improper assembly or disassembly (33). For example, Swart et al. (33) showed that chvB mutants of A. tumefaciens produced an inactive form of the protein rhicadhesin which resulted in the attachment-minus phenotype of chvB mutant and that the normal phenotype was restored by the addition of the purified rhicadhesin from a wild-type strain. Banta et al. (2) showed that the chvB mutant of A. tumefaciens exhibits lower levels of the VirB10 protein than does the wild type. VirB10 is a transmembrane protein that is part of the type IV secretion system required for T-DNA delivery into plant cells; it has been recently demonstrated that this type IV secretion system is conserved in B. abortus and that virB10 null mutants are avirulent (28). Rhizobium and Agrobacterium cgs mutants are nonmotile due to a defective assembly of the flagella, a process that is known to take place in the periplasmic space (34). All these observations suggest that the absence of cyclic glucan and/or Cgs inner membrane may be important for virulence. On the other hand, it cannot be excluded that the Cgs 316-kDa inner membrane protein may have a direct effect on virulence by itself.

Our results demonstrate that the residual virulence of B. abortus S19 depends on the presence of cyclic β-1,2-glucan, since BAI129 (cgs S19 mutant) was strongly attenuated in mice and displayed no intracellular multiplication in HeLa cells.

Montaraz and Winter (15) have shown that the number of CFU recovered from spleens of mice infected with B. abortus S19 peaked at 2 weeks postinfection with doses of 3.8 × 104 or 3.8 × 105 CFU. The behavior of the B. abortus S19 cgs mutant (strain BAI129) showed a different pattern of growth with a sharp declination of spleen counts after 2 weeks at all tested doses, thus indicating the inability of the mutant to replicate in the mice.

Despite the fact that the B. abortus S19 cgs mutant was cleared from the infected mice faster than the parental strain, due to reduction of virulence, our results showed that the mutant protected the mice against a challenge with the pathogenic B. abortus strain 2308 to the same extent as the parental vaccinal S19 strain.

In a recent study, Power et al. (23) proposed that the dose of the Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccine is crucial in determining the Th1/Th2 nature of the immune response. They demonstrated that relatively low doses lead to an almost exclusive cell-mediated Th1 response, while higher doses induce a mixed Th1/Th2 response. We show that mice inoculated with the B. abortus S19 cgs mutant present equivalent levels of IFN-γ mRNA as well as lower titers of anti-LPS antibodies of IgG1 subtype than those observed in mice vaccinated with the parental S19 strain, suggesting an almost exclusively Th1 response. These results may be explained by the limited replication of the mutant in the spleen.

The decreased virulence with retention of the capacity to confer immunity suggests that exploring the cgs S19 mutant as a potential improvement of the B. abortus S19 vaccine might be worthwhile.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank J. J. Cazzulo, A. C. C. Frasch, D. Comerci, and J. Ugalde for helpful comments, and Fabio Fraga, Ernesta Bissi, and Juan Benitez for technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants from the Ministerio de Cultura y Educación, República Argentina, to the Instituto de Investigaciones Biotecnológicas de la Universidad Nacional de General San Martín (Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica PICT 97-00080-01768 and PICT 99-06565). N.I.D.I. and R.A.U. are members of the Research Career of CONICET. M.R. is a fellow of the Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas CONICET. G.B., A.V., and P.S.P. are members of CNEA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alton G G, Jones L M, Angus R D, Verger J M. Techniques for the brucellosis laboratory. Paris, France: INRA; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banta L M, Bohne J, Lovejoy S D, Dostal K. Stability of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens VirB10 protein is modulated by growth temperature and periplasmic osmoadaption. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6597–6606. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.24.6597-6606.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Breedveld M B, Miller K. Cyclic glucan of members of family Rhizobiaceae. Microbiol Rev. 1994;58:145–161. doi: 10.1128/mr.58.2.145-161.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Briones G, Iñón de Ianino N, Steinberg M, Ugalde R A. Periplasmic cyclic 1,2-β-glucan in Brucella spp. is not osmoregulated. Microbiology. 1997;143:1115–1124. doi: 10.1099/00221287-143-4-1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charles T C, Nester E W. A chromosomally encoded two-component sensory transduction system is required for virulence of Agrobacterium tumefaciens. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6614–6625. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.20.6614-6625.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng H P, Walker G C. Succinoglycan production by Rhizobium meliloti is regulated through the ExoS-ChvI two-component regulatory system. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:20–26. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.1.20-26.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Comerci D J, Pollevick G D, Vigliocco A M, Frasch A C C, Ugalde R A. Vector development for the expression of foreign proteins in the vaccine strain Brucella abortus S19. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3862–3866. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3862-3866.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corner L A, Alton G G. Persistence of Brucella abortus S19 infection in adult cattle vaccinated with reduced doses. Res Vet Sci. 1981;31:342–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Douglas C J, Staneloni R J, Rubin R A, Nester E W. Identification and genetic analysis of an Agrobacterium tumefaciens chromosomal virulence region. J Bacteriol. 1985;161:850–860. doi: 10.1128/jb.161.3.850-860.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Enright F M. The pathogenesis and pathobiology of Brucella infection in domestic animals. In: Nielsen K, Duncan J R, editors. Animal brucellosis. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1990. pp. 153–197. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iñón de Iannino N, Briones G, Iannino F, Ugalde R A. Osmotic regulation of cyclic 1,2-β-glucan synthesis. Microbiology. 2000;146:1735–1742. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-7-1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iñón de Iannino N, Briones G, Tolmasky M, Ugalde R A. Molecular cloning and characterization of cgs, the Brucella abortus cyclic β(1-2) glucan synthetase gene: genetic complementation of Rhizobium meliloti ndvB and Agrobacterium tumefaciens chvB mutants. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4392–4400. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.17.4392-4400.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jimenez de Bagues M P, Elzer P H, Jones S M, Blasco J M, Enright F M, Schurig G G, Winter A J. Vaccination with Brucella abortus rough mutant RB51 protects BALB/c mice against virulent strains of Brucella abortus, Brucella melitensis, and Brucella ovis. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4990–4996. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.4990-4996.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LeVier K, Phillips R W, Grippe V K, Roop II R M, Walker G C. Similar requirements of a plant symbiont and a mammalian pathogen for prolonged intracellular survival. Science. 2000;287:2492–2493. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5462.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Montaraz J A, Winter A J. Comparison of living and nonliving vaccines for Brucella abortus in BALB/c mice. Infect Immun. 1986;53:245–251. doi: 10.1128/iai.53.2.245-251.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moreno E, Stackebrandt E, Dorsch M, Wolters J, Busch M, Mayer H. Brucella abortus 16S rRNA and lipid A reveal a phylogenetic relationship with members of the alpha-2 subdivision of the class Proteobacteria. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3569–3576. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.7.3569-3576.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nicoletti P. Relationship between animal and human disease. In: Young E J, Corbell M J, editors. Brucellosis: clinical and laboratory aspects. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1989. pp. 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicoletti P. Vaccination. In: Nielsen K, Duncan J R, editors. Animal brucellosis. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press; 1990. pp. 283–300. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nielsen K H, Kelly L, Gall D, Nicoletti P, Kelly W. Improved competitive enzyme immunoassay for the diagnosis of bovine brucellosis. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 1995;46:285–291. doi: 10.1016/0165-2427(94)05361-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Callaghan D, Cazevieille C, Allardet-Servent A, Boschiroli M L, Bourg G, Foulongne V, Frutos P, Kulakov Y, Ramuz M. A homologue of the Agrobacterium tumefaciens VirB and Bordetella pertussis Pti type IV secretion systems is essential for intracellular survival of Brucella suis. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:1210–1220. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pitossi F, del Rey A, Kabiersch A, Besedovsky H. Introduction of cytokine transcripts in the central nervous system and pituitary following peripheral administration of endotoxin to mice. J Neurosci Res. 1997;48:287–298. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4547(19970515)48:4<287::aid-jnr1>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pizarro-Cerdá J, Meresse S, Parton R G, Goot G, Sola-Landa A, Lopez-Goñi I, Moreno E, Gorvel J P. Brucella abortus transits through the autophagic pathway and replicates in the endoplasmic reticulum of nonprofessional phagocytes. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5711–5724. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.5711-5724.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Power C A, Wei G, Bretscher P A. Mycobacterial dose defines the Th1/Th2 nature of the immune response independently of whether immunization is administered by the intravenous, subcutaneous, or intradermal route. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5743–5750. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.5743-5750.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sangari F J, Agüero J. Molecular basis of Brucella pathogenicity: an update. Microbiol SEM. 1996;12:207–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sangari F J, Garcia-Lobo J M, Agüero J. The Brucella abortus strain B19 carries a deletion in the erythritol catabolic genes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;121:337–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sangari F, Grilló M J, Jimenez de Bagués M P, Gonzalez-Carreró M I, Garcia Lobo J M, Blasco J M, Agüero J. The defect in the metabolism of erythritol of the Brucella abortus B19 vaccine strain is unrelated with its attenuated virulence in mice. Vaccine. 1998;16:1640–1645. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schurig G G, Roop R M, Bagchi T, Boyle S, Buhrman D, Sriranganathan N. Biological properties of RB 51; a stable rough strain of Brucella abortus. Vet Microbiol. 1991;28:171–188. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(91)90091-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sieira R, Comerci D J, Sanchez D O, Ugalde R A. A homologue of an operon required for DNA transfer in Agrobacterium is required in Brucella abortus for virulence and intracellular multiplication. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:4849–4855. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.17.4849-4855.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith L D, Ficht T A. Pathogenesis of Brucella. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1990;17:209–229. doi: 10.3109/10408419009105726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sola-Landa A, Pizarro-Cerda J, Grillo M J, Moreno E, Moriyon I, Blasco J M, Gorvel J P, Lopez-Goñi I. A two-component regulatory system playing a critical role in plant pathogens and endosymbionts is present in Brucella abortus and controls cell invasion and virulence. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:125–138. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Soncini F C, Groisman E A. Two-component regulatory systems can interact to process multiple environmental signals. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6796–6801. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.23.6796-6801.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stibitz S, Yang M-S. Subcellular localization and immunological detection of proteins encoded by the vir locus of Bordetella pertussis. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4288–4296. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.14.4288-4296.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Swart S, Smit G, Lugtenberg B J J, Kijne J W. Restoration of attachment, virulence and modulation of Agrobacterium tumefaciens chvB mutants by rhicadhesin. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:597–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb00931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ugalde R A. Intracellular life style of Brucella spp. Common genes with other animal pathogens, plant pathogens, and endosymbionts. Microbes Infect. 1999;1:1211–1219. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(99)00240-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vemulapalli R, Duncan A J, Boyle S M, Sriranganathan N, Toth T E, Schurig G G. Cloning and sequencing of yajC and secD homologs of Brucella abortus and demonstration of immune responses to YajC in mice vaccinated with B. abortus RB51. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5684–5691. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.5684-5691.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Winter A J, Rowe G E, Duncan J R, Eis M J, Widom J, Ganem B, Morein B. Effectiveness of natural and synthetic complexes of porin and O polysaccharide as vaccines against Brucella abortus in mice. Infect Immun. 1988;56:2808–2817. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.11.2808-2817.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Young E J. Human brucellosis. Rev Infect Dis. 1983;5:821–842. doi: 10.1093/clinids/5.5.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]