Summary

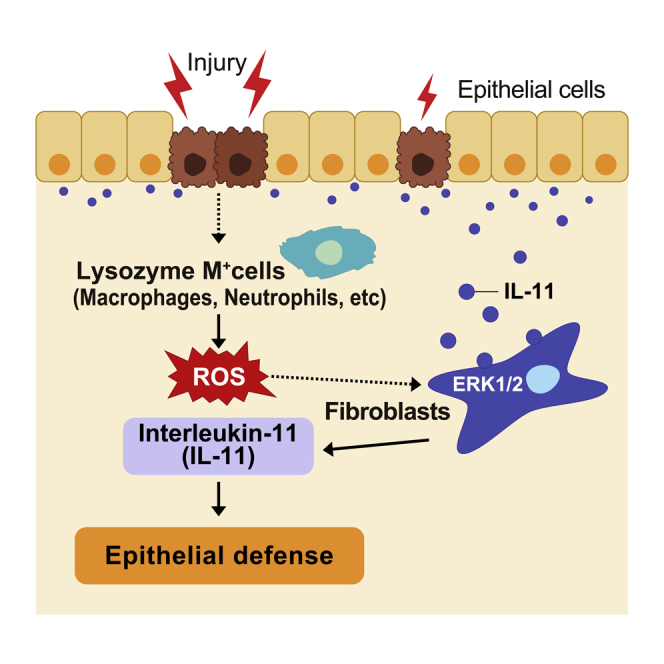

Intestinal homeostasis is tightly regulated by epithelial cells, leukocytes, and stromal cells, and its dysregulation is associated with inflammatory bowel diseases. Interleukin (IL)-11, a member of the IL-6 family of cytokines, is produced by inflammatory fibroblasts during acute colitis. However, the role of IL-11 in the development of colitis is still unclear. Herein, we showed that IL-11 ameliorated DSS-induced acute colitis in mouse models. We found that deletion of Il11ra1 or Il11 rendered mice highly susceptible to DSS-induced colitis compared to the respective control mice. The number of apoptotic epithelial cells was increased in DSS-treated Il11ra1- or Il11-deficient mice. Moreover, we showed that IL-11 production was regulated by reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced by lysozyme M-positive myeloid cells. These findings indicate that fibroblast-produced IL-11 plays an important role in protecting the mucosal epithelium in acute colitis. Myeloid cell-derived ROS contribute to the attenuation of colitis through the production of IL-11.

Subject areas: Components of the immune system, Immunology, Molecular physiology

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

IL-11/IL-11 receptor axis is required for the attenuation of DSS-induced colitis

-

•

IL-11 enhances the survival and growth of colon epithelial cells

-

•

Reactive oxygen species enhance IL-11 production in colonic fibroblasts

-

•

Lysozyme M+ cells are responsible for IL-11 induction during colitis

Components of the immune system; Immunology; Molecular physiology

Introduction

The intestinal epithelium is continuously exposed to large quantities of foreign proteins and microorganisms.1,2 Immune responses against antigens and epithelial regeneration processes are induced in response to tissue damage to maintain intestinal homeostasis. In addition, resident mesenchymal cells, including fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and podocytes, also play an important role in regulating tissue repair processes.3,4,5 However, the molecular mechanisms by which mesenchymal cells regulate colon tissue repair are still unclear. Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an inflammatory bowel disease characterized by mucosal inflammation in the distal colon and rectum.6,7 Although accumulating studies have suggested that genetic and environmental factors contribute to UC development, the underlying mechanisms are not fully understood. Various animal models have been used to investigate the mechanism underlying UC.8 Among them, dextran sulfate sodium (DSS), a sulfated polysaccharide, is the most popular agent used to induce colitis in mice as a model of human UC.9

Interleukin (IL)-11 is a member of the IL-6 family of cytokines and binds to IL-11Rα1 and glycoprotein 130 kDa (gp130).10,11 The binding of IL-11 to the receptors leads to the activation of intracellular signaling pathways, including the STAT3, MAPK, and AKT pathways.12 It has been reported that several cytokines induce IL-11 production, including TGFβ, IL-1β, IL-17A, and IL-22.13,14,15,16 We previously reported that reactive oxygen species (ROS) and an electrophile known as 1,2-naphthoquinone induce IL-11 production, thereby promoting tissue repair in the liver and intestine, respectively.17,18 Previous studies have shown that alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA)-negative stromal fibroblasts produce IL-11 in chemical-induced inflammatory bowel disease in mice.19,20,21 We very recently reported that IL-11 production is enhanced by oxidative stress and tightly regulated by MEK/ERK pathway activation in the colon of DSS-treated mice.19 A polymorphism in the IL11 gene is associated with increased susceptibility to UC in human patients.22 While the expression of IL11 is increased in patients with mild UC, the expression of IL11 is decreased in patients with severe UC.23 Microarray data in humans show that high IL-11 levels predict severe colitis and lack of response to biological therapy.24 Notably, single-cell RNA sequencing analysis revealed that colon samples of patients with UC include a unique subset of fibroblasts, termed inflammation-associated fibroblasts, that have high expression of IL11, IL24, IL13RA2, and TNFSFR11 and are enriched in patients who are resistant to anti-TNF treatment.25 Along the same lines, transgenic murine Il11 in α-smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts results in inflammation and fibrosis in the intestine of mice.26 These studies suggest a correlation between IL-11 expression and the degree of inflammation or disease severity. In sharp contrast, human IL-11 treatment ameliorates tissue damage in animal models of intestinal injury.27,28,29 However, a previous study suggested that recombinant human IL-11 acts as an inhibitor of endogenous mouse IL-11 in mice.30 Therefore, the contribution of IL-11 to the attenuation or exacerbation of colitis appears to be context dependent.

In the present study, we sought to uncover the role of IL-11 in intestinal homeostasis by using DSS-induced colitis mouse models. We revealed that deletion of Il11ra1 or Il11 renders mice highly susceptible to DSS-induced colitis compared to the respective control mice. Mechanistically, lysozyme M-positive cells produce ROS that subsequently induce IL-11 production by stromal fibroblasts in DSS-induced colitis. Then, IL-11 inhibits apoptosis of intestinal epithelial cells, thereby attenuating colitis. These findings indicate that IL-11 plays an important role in maintaining colon homeostasis.

Results

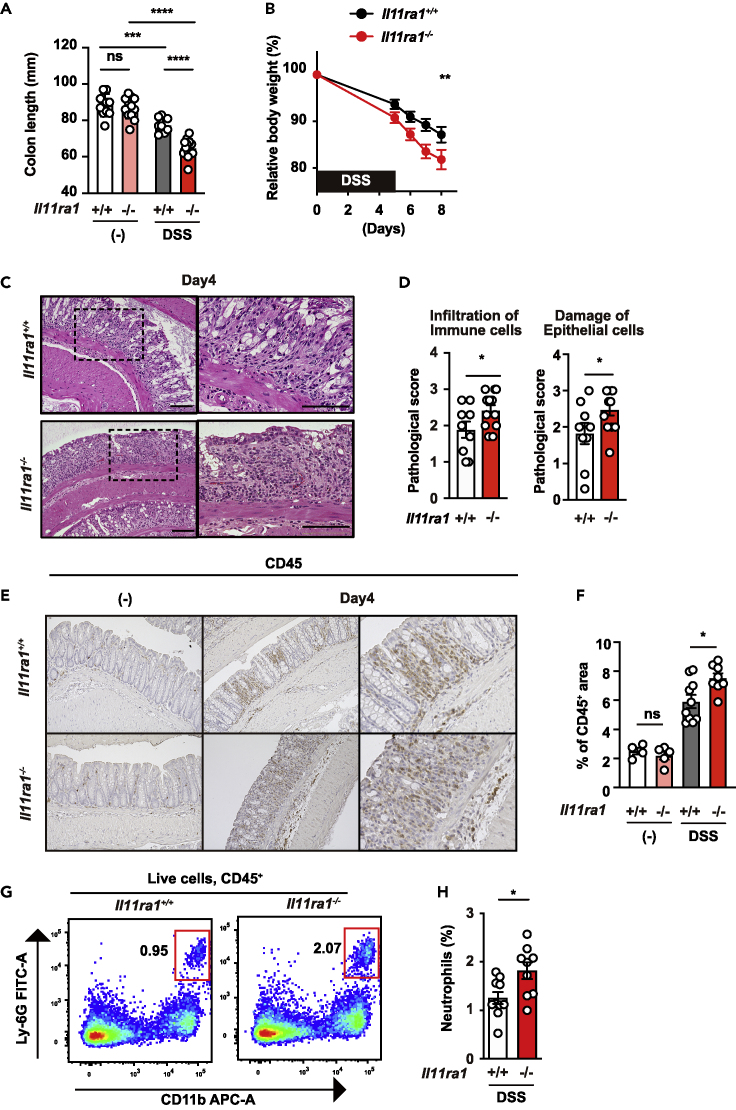

DSS-induced colitis is exacerbated in Il11ra1−/− mice

We previously reported that IL-11 expression was very low in the colon of mice, suggesting that IL-11 does not play a role in the colon of mice under homeostatic conditions.17 On the other hand, it has been suggested that developmental abnormalities may exist in Il11ra1−/− mice.30,31 Therefore, we analyzed Il11ra1+/+ and Il11ra1−/− mice to determine whether any intestinal abnormalities were observed. We found that there were no differences in the lengths of the colon between Il11ra1+/+ and Il11ra1−/− mice (Figure 1A). To investigate the role of IL-11 in the development of colitis, we treated Il11ra1+/+ and Il11ra1−/− mice with DSS. Body weight loss and shortening of the colon, hallmarks of the severity of colitis, were significantly exacerbated in DSS-treated Il11ra1−/− mice compared to wild-type mice (Figures 1A and 1B). Due to the differences in body weights being observed relatively early after DSS treatment, we analyzed the histology on day 4 after DSS treatment. Histology revealed exacerbated tissue injury and increased immune cell infiltration (Figures 1C and 1D). Immunohistochemistry confirmed that CD45+ immune cell infiltration was increased in the colon of DSS-treated Il11ra1−/− mice compared to wild-type mice (Figures 1E and 1F). Flow cytometry analysis showed that neutrophil accumulation was increased in the colon of Il11ra1−/− mice compared to wild-type mice following DSS treatment (Figures 1G and 1H and S1A). These results indicate that the IL-11/IL-11ra axis is required for the attenuation of DSS-induced colitis.

Figure 1.

DSS-induced colitis is exacerbated in Il11ra1-/- mice

(A) The colon length of untreated or DSS-treated mice was determined on day 15 after DSS treatment. The results are the mean ± SEM. n = 10 (untreated Il11ra1+/+), 13 (untreated Il11ra1−/−), 8 (DSS-treated Il11ra1+/+), or 13 (DSS-treated Il11ra1−/−) mice. Pooled data from four independent experiments.

(B) Il11ra1+/+ or Il11ra1−/− mice were treated with 1.5% DSS in their drinking water for 5 days and then received normal drinking water again. The body weight of the mice was determined on day 5 and after that day. The results are expressed as percentages of initial body weight. The results are the mean ± SEM. n = 19 (Il11ra1+/+) or 18 (Il11ra1−/−) mice; pooled data from four independent experiments.

(C and D) Hematoxylin and eosin (HE)-stained colonic sections of Il11ra1+/+ or Il11ra1−/− mice on day 4 after DSS administration. n = 9 (Il11ra1+/+) or 12 (Il11ra1−/−) mice; pooled data from two independent experiments. Right panels are enlarged images of the boxes in the left panels. Scale bar, 100 μm. (C) The severity of colitis was quantified based on the infiltration of immune cells (left panel) and damage to epithelial cells (right panel) as described in the STAR Methods. The results are the mean ± SEM. n = 9 (Il11ra1+/+) or 12 (Il11ra1−/−) mice; pooled data from four independent experiments (D).

(E and F) Colon sections were stained with anti-CD45 antibodies (E). The CD45+ area and total area were calculated, and the percentages of CD45+ area per area are expressed (F). The results are the mean ± SEM. n = 4 (untreated Il11ra1+/+), 5 (untreated Il11ra1−/−), 10 (DSS-treated Il11ra1+/+), or 8 (DSS-treated Il11ra1−/−) mice.

(G and H) The percentages of infiltrated neutrophils were increased in the colon of Il11ra1−/− mice compared with Il11ra1+/+ mice. Colonic lamina propria cells were prepared from untreated mice or mice treated with DSS on day 12, stained with the indicated antibodies, and analyzed by flow cytometry. Representative plots (G) of two independent experiments and percentages of neutrophils in the colon of an individual mouse after DSS treatment (H) are shown. The results are the mean ± SEM (n = 9 mice). Pooled data from two independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test (D and H), two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (A and F) or Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test (B). ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, not significant. See also Figure S1.

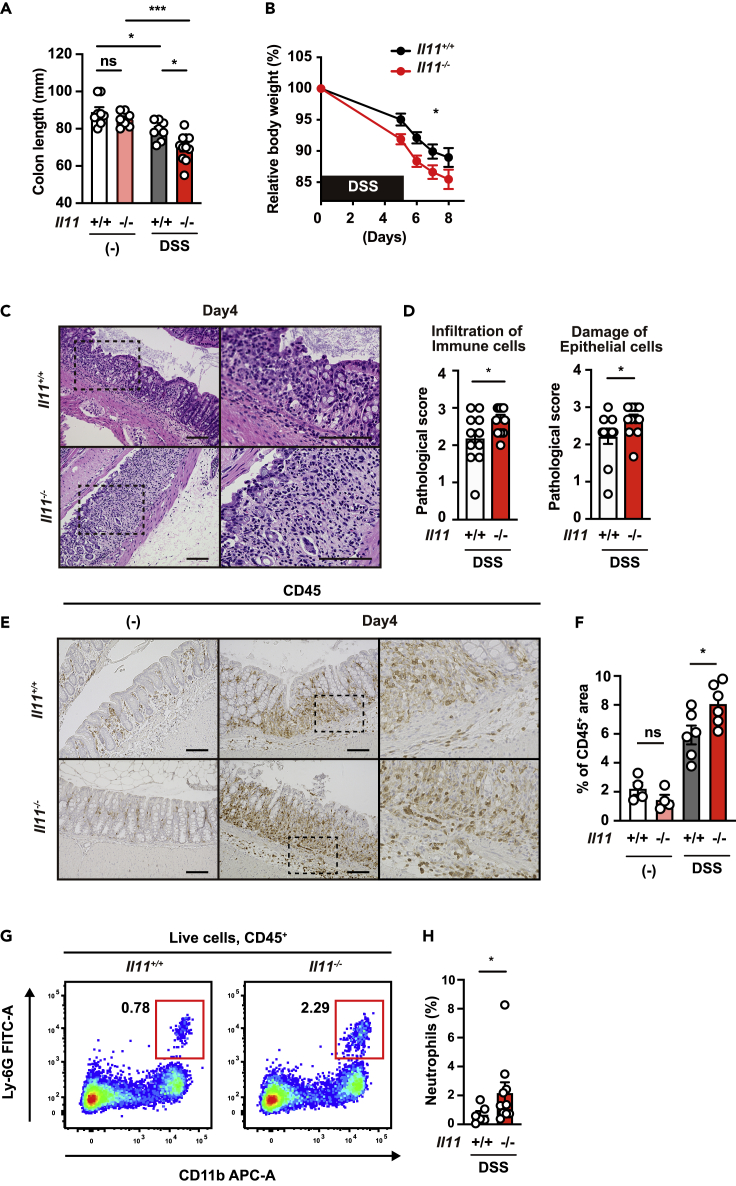

DSS-induced colitis is exacerbated in Il11−/− mice

Because some genes have different phenotypes in receptor-deficient and ligand-deficient mice, we used Il11−/− and Il11+/+ mice to examine whether IL-11, the ligand of IL-11Ra1, is required to attenuate colitis.32 Although no differences were observed in colon length between Il11−/− mice and Il11+/+ mice under normal conditions (Figure 2A), body weight loss and shortening of the colon were significantly exacerbated in DSS-treated Il11−/− mice compared to Il11+/+ mice (Figures 2A and 2B). Moreover, tissue injury, immune cell infiltration, and neutrophil accumulation were increased in the colon of Il11−/− mice compared to Il11+/+ mice following DSS treatment (Figures 2C–2H). These results indicate that the IL-11/IL-11Ra1 axis plays an important role in attenuating DSS-induced colitis in a relatively early stage.

Figure 2.

DSS-induced colitis is exacerbated in Il11-/- mice

(A) Il11+/+ or Il11−/− mice were treated as in Figure 1. The colon length of untreated or DSS-treated mice was determined on day 15 after DSS treatment. The results are the mean ± SEM. n = 8 (untreated Il11+/+), 7 (untreated Il11−/−), 8 (DSS-treated Il11+/+), or 11 (DSS-treated Il11−/−) mice. Pooled data from two independent experiments.

(B) The body weight of the mice was determined on day 5 and thereafter. The results are expressed as percentages of initial body weight. The results are the mean ± SEM. n = 16 (Il11+/+) or 19 (Il11−/−) mice; pooled data from four independent experiments.

(C and D) Hematoxylin and eosin (HE)-stained colonic sections of Il11+/+ or Il11−/− mice on day 4 after DSS administration. Right panels are enlarged images of the boxes in the left panels. Scale bar, 100 μm. The severity of colitis was quantified based on the infiltration of immune cells (left panel) and damage to epithelial cells (right panel) as described in STAR Methods (D). The results are the mean ± SEM. n = 11 (Il11+/+) or 13 (Il11−/−) mice; pooled data from two independent experiments.

(E and F) Colon sections were stained with anti-CD45 antibodies (E). The CD45+ area and total area were calculated, and the percentages of CD45+ area per total area are expressed (F). The results are the mean ± SEM. n = 4 (untreated Il11+/+), 4 (untreated Il11−/−), 6 (DSS-treated Il11+/+), 6 (DSS-treated Il11-/) mice.

(G and H) The percentages of infiltrated neutrophils were increased in the colon of Il11−/− mice compared with Il11+/+ mice. Colonic lamina propria cells were prepared and analyzed as in Figure 1F. Representative plots (G) and percentages of neutrophils (H) in the colon of an individual mouse after DSS treatment (right panels) are shown. The results are the mean ±SEM. n = 6 (Il11+/+) or 11 (Il11−/−) mice. Pooled data from two independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (A and F), Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons test (B), a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test (D), or two-tailed Mann–Whitney U test (H). ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

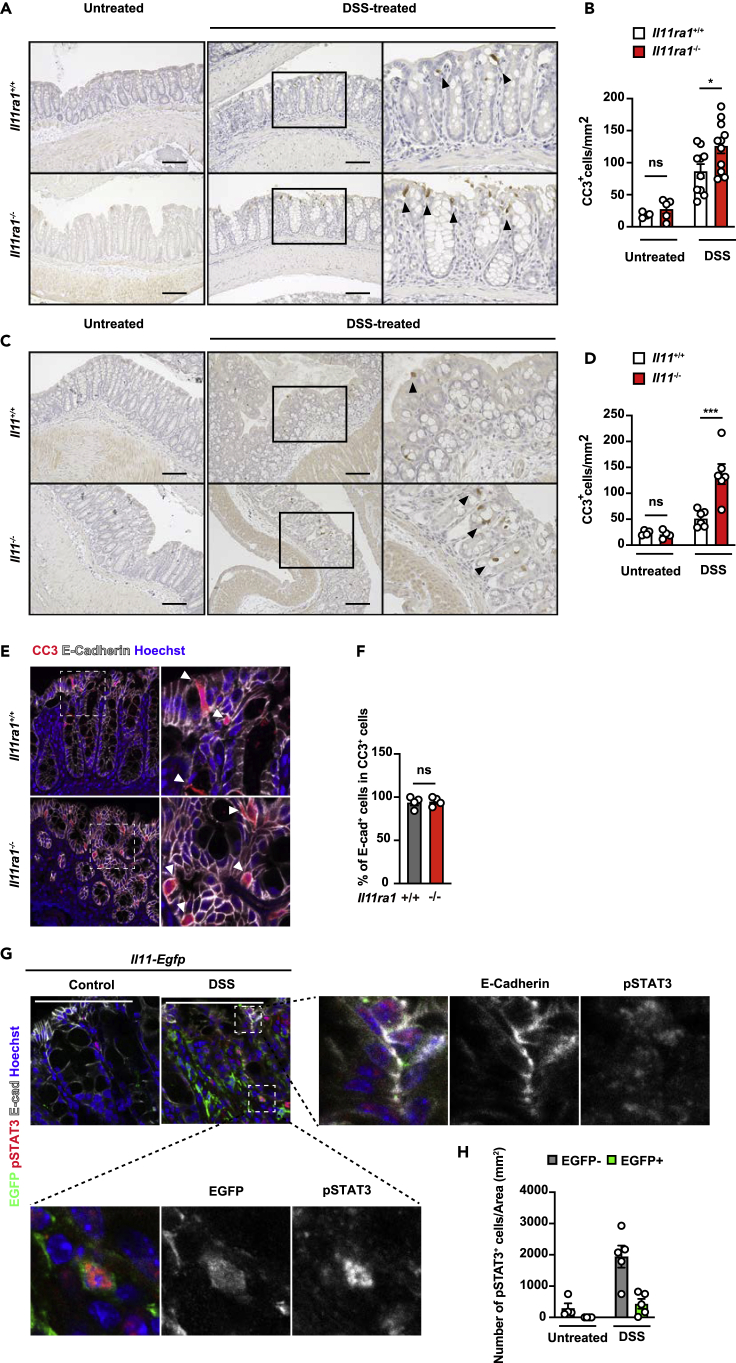

IL-11 enhances the survival and growth of colon epithelial cells

The fact that DSS-induced colitis was exacerbated in Il11ra1−/− and Il11−/− mice prompted us to test whether intestinal epithelial cell death was enhanced in these mice.33 To test whether IL-11 regulates the survival of epithelial cells in DSS-induced colitis, we performed cleaved caspase 3 (CC3) staining, which is a hallmark of apoptosis. Although there were no differences between untreated wild-type mice and Il11ra1−/− or Il11−/− mice, we found that the number of CC3-positive cells was increased in the colon of DSS-treated Il11ra1−/− or Il11−/− mice compared to control DSS-treated wild-type mice (Figures 3A–3D). In addition, we also found that TUNEL (a hallmark of apoptosis)-positive cells were increased in the colon of DSS-treated Il11ra1−/− or Il11−/− mice compared to wild-type mice (Figures S2A–S2D). Notably, the majority of CC3+ cells expressed E-cadherin, an intestinal epithelial cell (IEC) marker (Figures 3E and 3F), suggesting that IL-11 prevents apoptosis of IECs in DSS-induced colitis. We previously reported that IL-11 signals to colonic epithelial cells and fibroblasts.19 To determine whether STAT3 activation is observed in IECs and IL-11-producing fibroblasts in vivo, we treated Il11-Egfp reporter mice with DSS to label IL-11-producing cells EGFP+ (Figures 3G and 3H). Although there were few pSTAT3+ cells in the colon of untreated Il11-Egfp reporter mice, pSTAT3+ cells were observed in the EGFP+ fibroblasts and EGFP− IECs in the colon of DSS-treated Il11-Egfp reporter mice. These results suggested that IL-11 may attenuate the cell death of IECs by directly activating IECs and indirectly activating IL-11-producing fibroblasts.

Figure 3.

IL-11 enhances the survival and growth of colon epithelial cells

(A and B) Il11ra1+/+ or Il11ra1−/− mice were treated with 1.5% DSS in the drinking water for 4 days. Colon sections were prepared on Day 4 and stained with anti-cleaved caspase-3 (CC3) antibody (A). The right panels show an enlargement of the left boxes. The numbers of CC3+ cells were calculated, and the ratios of CC3+ cells/total tissue areas (%) are plotted (B). The results are the mean ± SEM. n = 4 (control, Il11ra1+/+), 10 (DSS-treated, Il11ra1+/+), 5 (control, Il11ra1−/−), or 11 (DSS-treated, Il11ra1−/−) mice; pooled data from two independent experiments.

(C and D) Il11+/+ or Il11−/− mice were treated with 1.5% DSS in the drinking water for 4 days. Colon sections were prepared on Day 4 and stained with anti-CC3 antibodies (C). The right panels show an enlargement of the left boxes (C). The numbers of CC3+ cells were calculated, and the ratios of CC3+ cells/total tissue areas (%) are plotted (D). Black arrowheads indicate CC3+ cells (A and C). The results are the mean ± SEM. n = 4 (control, Il11+/+), 6 (DSS-treated, Il11+/+), 4 (control, Il11−/−), or 6 (DSS-treated, Il11−/−) mice; pooled data from two independent experiments.

(E and F) Colon sections were stained with anti-CC3 (red), anti-E-cadherin (gray), and Hoechst 33,258 (blue) antibodies. The numbers of CC3+and E-cadherin+ cells were counted, and the percentages of both CC3- and E-cadherin-positive CC3+ cells are expressed (F). The results are the mean ± SEM. n = 4 (DSS-treated Il11ra1+/+) or 4 (DSS-treated Il11ra1−/−) mice.

(G and H) Representative immunostaining of IL-11+ cells in the colon of DSS-treated mice. Colon tissue sections were prepared from untreated or DSS-treated Il11-Egfp reporter mice on day 5 following DSS treatment. Colon tissue sections were stained with anti-GFP (green), anti-E-cadherin (gray), and anti-phospho-STAT3 (pSTAT3) (red) antibodies and Hoechst 33,258 (blue). pSTAT3+ and EGFP+ cells were counted and normalized to the total tissue area (H). Scale bars, 100 μm (A, C, E, and G). Statistical significance was determined by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (B and D) and a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test (F). ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ns, not significant. See also Figure S2.

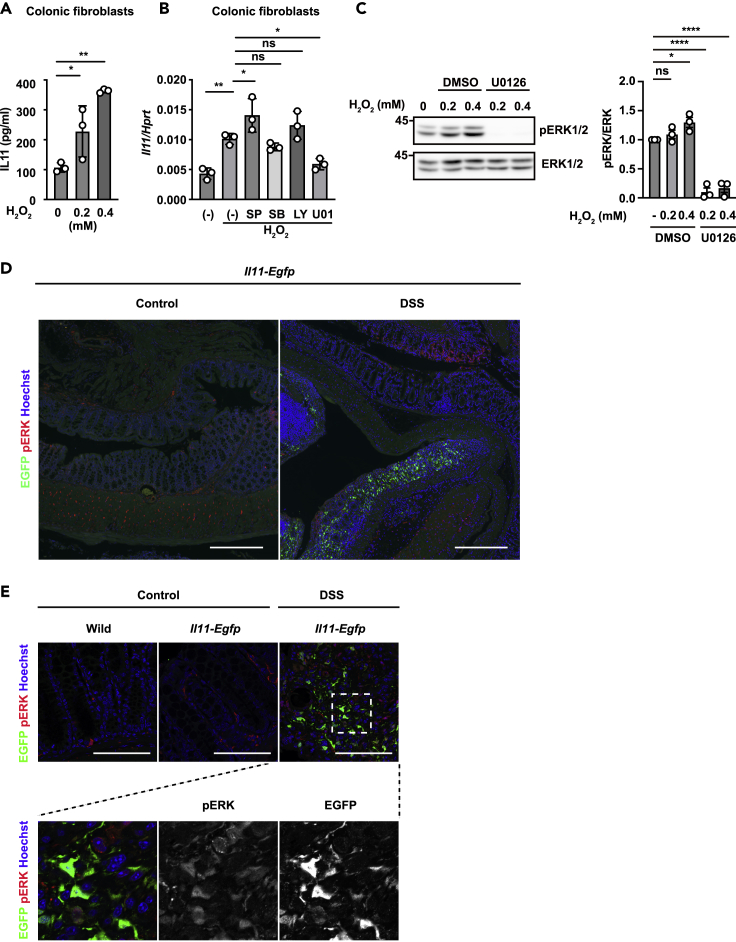

Reactive oxygen species enhance IL-11 production in colonic fibroblasts

We previously reported that the expression of Il11 mRNA was increased in a MEK/ERK-dependent manner, and treatment with N-acetylcysteine, an antioxidant, significantly decreased the increase in Il11 expression in the colon of DSS-treated mice.19 To test whether reactive oxygen species directly induce IL-11 production, we purified primary colon fibroblasts and treated the fibroblasts with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). We found that IL-11 production was increased by H2O2 treatment in colon fibroblasts (Figure 4A). Oxidative stress activates various signaling pathways, including the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and AKT pathways, depending on the cell type.34,35 To address which signaling pathways are responsible for Il11 induction, we treated colonic fibroblasts with H2O2 in the presence of various MAPK inhibitors, including U0126 (a MEK inhibitor), SB203580 (a p38 inhibitor), SP600125 (a JNK inhibitor), or LY294002 (an AKT inhibitor) (Figure 4B). U0126 treatment substantially decreased Il11 expression, suggesting that IL-11 is induced by activating the MEK/ERK pathway enhanced by H2O2 in fibroblasts. In addition, H2O2 treatment increased the phosphorylation of ERK in colonic fibroblasts (Figure 4C). To determine whether ERK activation is observed in IL-11-producing fibroblasts in vivo, we examined the colons of DSS-treated Il11-Egfp reporter mice (Figures 4D and 4E). Immunohistochemical analysis (IHC) revealed that EGFP-positive cells were not found in the colon of untreated wild mice or Il11-Egfp reporter mice. However, IL-11-producing EGFP-positive cells appeared in the lamina propria, where intestinal epithelial cells were detached due to inflammation in Il11-Egfp reporter mice (Figure 4D). In addition, phosphorylation of ERKs was observed in EGFP-positive IL-11-producing cells (Figure 4E). Together, these findings suggest that ERK activation in fibroblasts is involved in the induction of IL-11 expression.

Figure 4.

Reactive oxygen species enhance IL-11 production in colonic fibroblasts

(A) Mouse colonic fibroblasts were established from wild-type mice as described in the STAR Methods. Mouse colonic fibroblasts were stimulated with H2O2 at the indicated concentrations for 18 h. The amount of IL-11 in culture supernatants was determined by ELISA. The results are the mean ± SD (n = 3). The results are representative of two independent experiments.

(B) Mouse colonic fibroblasts were stimulated with 0.6 mM H2O2 in the presence or absence of SP600125 (SP), SB203580 (SB), LY294002 (LY), or U0126 (U01) for 4 h. Relative amounts of Il11 mRNA were determined by qPCR and are presented as the means ± SDs (n = 3). Data are presented relative to Hprt expression. The results are representative of two independent experiments.

(C) Primary colon fibroblasts were treated with the indicated concentration of H2O2 in the presence or absence of U0126 (20 μM) for 30 min. Total ERK and phosphorylated ERK (pERK) were analyzed by western blotting. The results are representative of three independent experiments. ERK and pERK signaling intensities were calculated by Fiji. The averages of the relative pERK/ERK ratios at the indicated points are shown (n = 3 independent experiments).

(D and E) Representative immunostaining of IL-11+ cells in the colon of DSS-treated mice. Colon tissue sections were prepared from untreated or DSS-treated wild-type or Il11-Egfp reporter mice on day 5 following DSS treatment. Colon tissue sections were stained with anti-GFP (green), anti-phospho-ERK1/2 (pERK) antibodies (red), and Hoechst 33,258 (blue). Scale bars, 300 μm (D), or 100 μm (E). Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (A, B, and C). ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

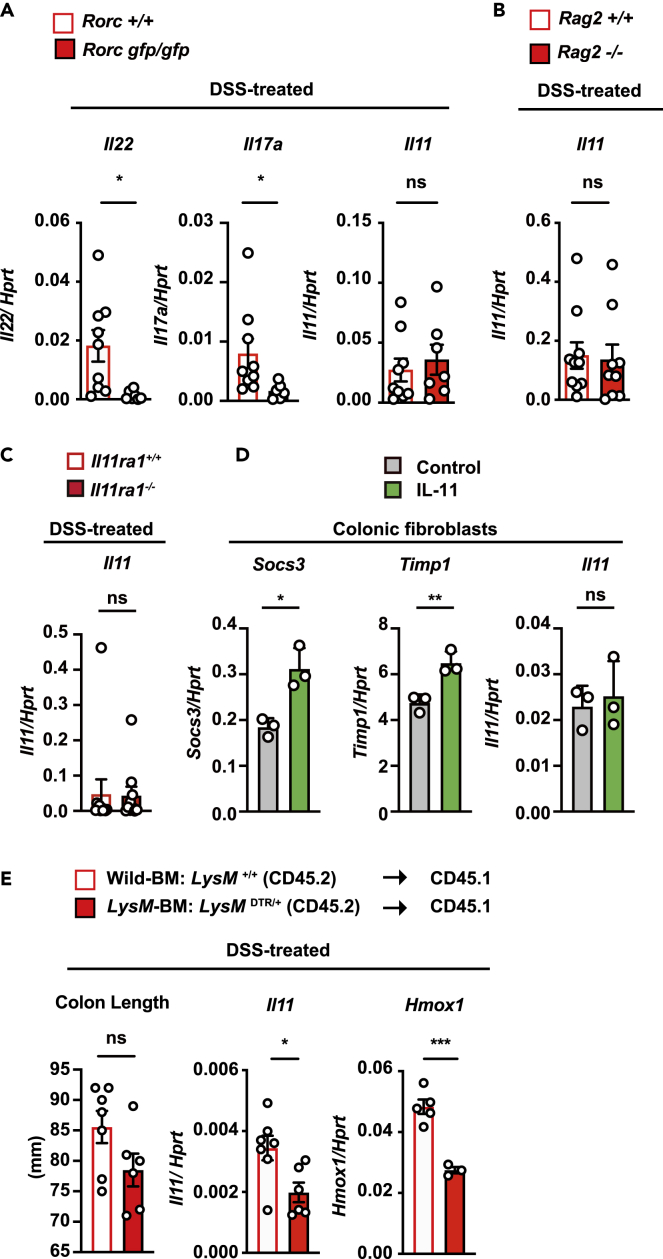

T cells, B cells, and RORγt+ cells are not responsible for IL-11 induction

Previous studies have shown that several cytokines induce the production of IL-11, including IL-1β, IL-17A, IL-22, and TNF, in vitro and in vivo.13,14,15,16 We then aimed to identify the factor(s) that induce IL-11 expression during DSS-induced colitis. Previous studies have reported that IL-22 plays a crucial role in DSS-induced colitis by upregulating a set of tissue repair genes, including Reg3b and Reg3g.36 Rorc encodes the transcription factor RORγt; this molecule is essential for the development of Th17 cells and type 3 innate lymphoid cells (ILC3s), which produce IL-22.37,38 Consistent with a previous study,39 the deletion of Rorc blocked the expression of Il22 and Il17a in the colon of DSS-treated mice (Figure 5A). However, DSS-induced expression of Il11 in the colon of Rorcgfp/gfp mice was comparable to that in the colon of Rorc+/+ mice (Figure 5A). Moreover, the expression of Il11 was not impaired in the colons of Rag2−/− mice, which lack both T and B cells (Figure 5B). Together, IL22, RORγt+ cells, which include ILC3s and Th17 cells, and T or B cells are not responsible for the expression of Il11 mRNA in the colon of DSS-treated mice.

Figure 5.

T cells, B cells, and RORγt+ cells are not responsible for IL-11 production

(A) Il22, Il17a, and Il11 mRNA levels in the colonic tissue from DSS-treated Rorc+/+ or Rorcgfp/gfp mice. On day 5 after DSS treatment, Il22, Il17a, and Il11 mRNA expression was determined by qPCR. The results are the mean ± SEM. n = 9 (Rorc+/+) or 7 (Rorcgfp/gfp) mice; pooled results from two independent experiments.

(B) Il11 expression is not altered in the colon between DSS-treated Rag2+/+ and Rag2−/− mice. On day 5 after DSS treatment, Il11 expression was determined by qPCR. The results are the mean ± SEM. n = 10 (Rag2+/+) or 9 (Rag2−/−) mice; pooled results from two independent experiments.

(C) Il11 expression is not altered in the colon between DSS-treated Il11ra1+/+ and Il11ra1−/− mice. On day 5 after DSS treatment, Il11 expression was determined by qPCR. The results are the mean ± SEM. n = 11 (Il11ra1+/+) or 10 (Il11ra1−/−) mice; pooled results from three independent experiments.

(D) Mouse colonic fibroblasts were established from wild-type mice and stimulated with IL-11 (100 ng/mL) for 4 h. Il11 mRNA expression was determined by qPCR. The results are the mean ± SD (n = 3). The results are representative of two independent experiments.

(E) LysM+ cells contribute to the increased expression of Il11 in DSS-treated mice. Bone marrow (BM) cells were prepared from LysMDTR/+ mice (CD45.2) or littermate wild-type mice. Then, the BM cells were transferred to CD45.1 recipient mice that had been exposed to lethal irradiation. At 8 weeks after transfer, the BM-transferred mice were treated with 1.5% DSS for 5 days and then injected with DT. The colon lengths were analyzed on day 7. Il11 and Hmox1 expression in the colonic tissue on day 7. We referred to CD45.1 wild-type recipient mice reconstituted with BM cells from wild-type and LysMDTR/+ mice as wild-type BM and LysM-BM mice, respectively. Statistical significance was determined by a two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test. ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001; ns, not significant. See also Figure S3.

IL-11 induces the activation of the MEK/ERK pathway. However, deletion of Il11ra1 did not abolish the upregulation of Il11 in the colon of DSS-treated mice (Figure 5C). In addition, IL-11 treatment increased the expression of Timp1 and Socs3, which are target genes of STAT3, in colonic fibroblasts. In contrast, Il11 expression was not elevated in IL-11-treated fibroblasts (Figure 5D). These results suggest that ERK activation by H2O2 upregulated Il11 expression at the transcriptional level. However, IL-11-induced ERK activation was not sufficient for Il11 induction.

It is known that oxidative stress is closely associated with an increase in lysozyme M (LysM)-expressing myeloid cells, including neutrophils, macrophages, monocytes, and some dendritic cells, in immune responses during colitis.40,41,42 To examine whether LysM-positive cells are involved in IL-11 induction in vivo, we used human diphtheria toxin receptor (DTR)-expressing mice under the control of the LysM promoter (LysM+/DTR).43 Although murine cells are resistant to DT, the expression of human DTR renders murine cells susceptible to DT-induced apoptosis.44 To clarify whether only myeloid cells are involved in the induction of IL-11, since LysM is also expressed in type II alveolar epithelial cells,43,45 we generated bone marrow (BM) chimeric mice. We referred to wild-type mice reconstituted with BM cells from wild-type and LysM DTR/+ mice as wild-type BM and LysM-BM mice, respectively. A previous study reported that the presence of myeloid cells affects the pathogenesis of DSS-induced colitis.46 Therefore, we depleted LysM-positive cells by administering DT on day 5 following DSS administration and analyzed the expression of Il11 in the colon on day 7. As expected, we found that DT treatment decreased the populations of CD11b+ Ly-6G− cells, including macrophages, monocytes, and some dendritic cells, and CD11b+ Ly-6G+ cells, including neutrophils, in the colons of DSS-treated LysM-BM mice compared with those in the colons of wild-type BM mice (Figures S3A–S3D). The expression of Il11 and the oxidative stress-inducible gene Hmox1 in the colon of DT-treated LysM-BM mice was significantly lower than that in the colon of DT-treated wild-type BM mice (Figure 5E). These results indicated that the increase in IL-11 was regulated by LysM-positive cells.

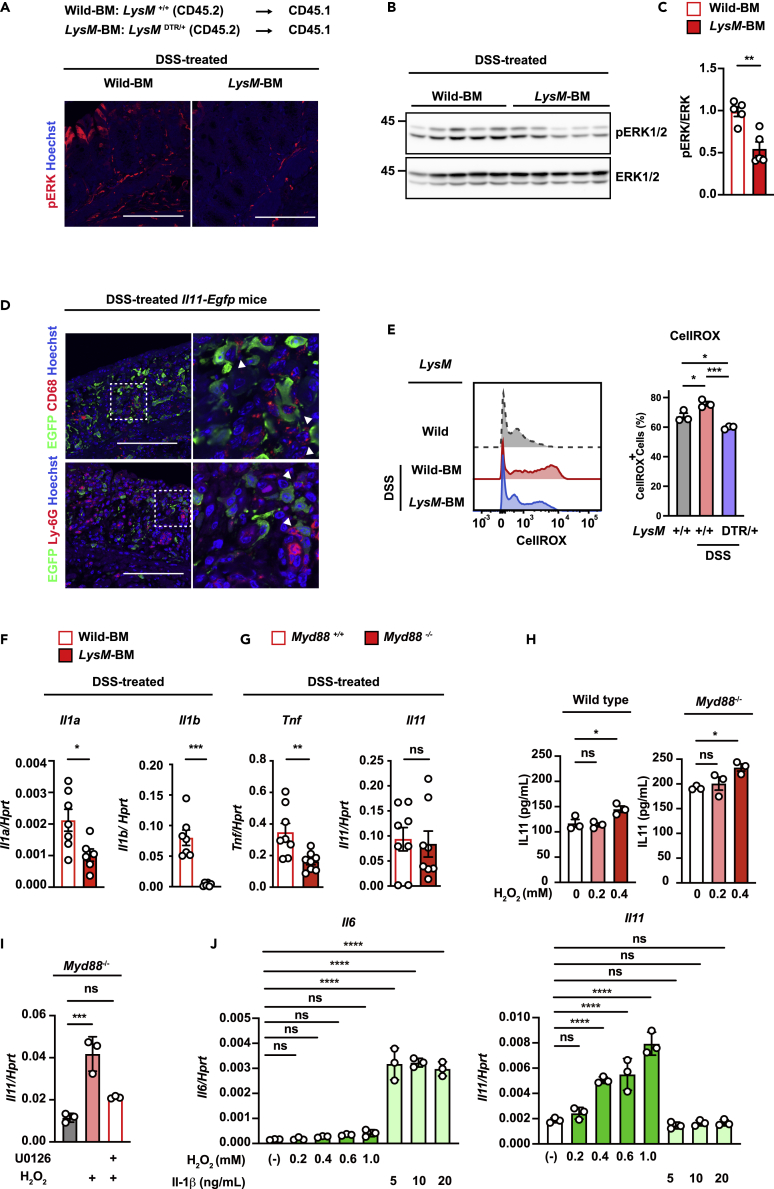

Lysozyme M-positive cells are responsible for IL-11 induction during DSS-induced colitis

Il11 expression was increased in a MEK/ERK-activation-dependent manner in the colon of DSS-treated mice.19 IHC and western blot analysis revealed that ERK1/2 phosphorylation was decreased in the colon of DSS-treated LysM-BM mice compared with that in the colon of DSS-treated wild-type BM mice (Figures 6A–6C). Moreover, IL-11-producing cells were found to exist close to macrophages (CD68+ cells) and neutrophils (Ly-6G+ cells) in the colon of DSS-treated Il11-Egfp reporter mice (Figure 6D). These results suggest that LysM-positive cells induce IL-11 expression in fibroblasts in DSS-induced colitis.

Figure 6.

Lysozyme M (LysM)-positive cells promote IL-11 expression during DSS-induced colitis

(A–C) ERK activation was reduced in the colon of mice lacking LysM-positive cells. Wild-type BM and LysM-BM mice were prepared and treated as shown in Figure 5C. Colon tissue sections from untreated or DSS-treated wild-type BM or LysM-BM mice were immunostained with an anti-phospho-Erk1/2 antibody (pERK) (A). Scale bar, 100 μm. (n = 5 mice). Total ERK and pERK in the colonic tissue of wild-type BM or LysM-BM mice were analyzed by Western blotting (B). Total ERK and pERK signal intensities were calculated by Fiji, and the relative ratios of pERK/ERK are shown (C). The results are the mean ± SEM. (n = 5 mice); pooled results from two independent experiments.

(D) Colon tissue sections were prepared from DSS-treated Il11-Egfp reporter mice on day 5 following DSS treatment. Colon tissue sections were stained with anti-GFP antibody (green) and anti-CD68 or Ly-6G antibody (red). The right panels show enlarged images of white dashed boxes from the left panels. White arrowheads indicate the interactions of GFP+ cells and CD68+ cells or Ly-6G+ cells. Scale bar, 100 μm. (n = 5 mice).

(E) Colon cells were prepared and stained with CellROX-Green, and ROS accumulation was analyzed by flow cytometry. Left panels show representative histograms of ROS levels in colon cells. Right panels show the percentages of CellROX-Green+ cells from an individual mouse. The results are the mean ± SEM. (n = 3 mice).

(F) Il1a and Il1b expression in the colonic tissue from DSS-treated wild-type BM or LysM-BM mice. Il1a and Il1b mRNA expression was determined by qPCR. The results are the mean ± SEM. n = 7 (wild-type BM) or 6 (LysM-BM) mice; pooled results from two independent experiments.

(G) The expression of Tnf and Il11 in the colonic tissue from DSS-treated Myd88+/+ or Myd88−/− mice. The expression of Tnf and Il11 was determined by qPCR. The results are the mean ± SEM. (n = 8 mice).

(H) Mouse colonic fibroblasts were established from wild-type mice or Myd88-/- mice as described in the STAR Methods. Mouse colonic fibroblasts were stimulated with H2O2 at the indicated concentrations for 12 h. The amount of IL-11 in culture supernatants was determined by ELISA. The results are the mean ± SD (n = 3). The results are representative of two independent experiments.

(I) Mouse colonic fibroblasts established from Myd88−/− mice were stimulated with 0.6 mM H2O2 in the presence or absence of U0126 (20 μM) for 4 h. Il11 mRNA expression was determined by qPCR. The results are the mean ± SD (n = 3). The results are representative of two independent experiments.

(J) Mouse colonic fibroblasts were established from wild-type mice stimulated with H2O2 or IL-1β at the indicated concentrations for 4 h. Il11 mRNA expression was determined by qPCR. The results are the mean ± SD (n = 3). The results are representative of two independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using the two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test (C, F, and G) or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (E, H, I, and J). ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001; ns, not significant.

To identify whether LysM-positive cells are involved in the induction of oxidative stress, we tested the levels of ROS in the colons of DSS-treated mice. Analysis of mouse colonic cells using CellROX, a fluorescent ROS reporter, revealed that DSS treatment significantly increased ROS levels in the colons of DT-treated wild-type BM mice but not in the colons of DT-treated LysM-BM mice (Figures 6E and S3E). These results indicate that LysM-positive cells enhanced oxidative stress in the colon of DSS-treated mice. Moreover, it is known that LysM-positive cells produce IL-1α and IL-1β and regulate intestinal homeostasis.47,48 IL-1α and IL-1β induce gene expression in cells via Myd88, a critical component of the signaling pathway through the IL-1 receptor.49,50 Indeed, DT-treated LysM-BM mice showed reduced colonic expression of Il1a and Il1b compared to control DSS-treated wild-type BM mice (Figure 6F). To examine whether the IL-1-Myd88 axis is involved in IL-11 induction in colitis, we used Myd88-deficient mice.50 Although Tnf expression in the colon of DSS-treated Myd88−/− mice was lower than that in Myd88+/+ mice, the increase in Il11 expression was not impaired in the colon of Myd88−/− mice (Figure 6G). In addition, we found that IL-11 production was increased by H2O2 treatment in primary colonic fibroblasts prepared from Myd88−/− mice (Figure 6H). U0126 treatment substantially decreased Il11 expression in H2O2-treated Myd88−/− colonic fibroblasts compared to untreated H2O2-treated Myd88−/− fibroblasts (Figure 6I). These results suggested that H2O2 treatment increased IL-11 expression in a MyD88-independent manner. Moreover, to examine the contribution of IL-1, we treated fibroblasts with IL-1β or H2O2. We found that IL-1β treatment increased Il6 expression but not Il11 expression in colonic fibroblasts (Figure 6J). These studies indicate that the increase in IL-11 is regulated by LysM-positive cells in an oxidative stress-dependent but not IL-1/Myd88 axis-dependent manner.

Discussion

In this study, we showed that deficiency of Il11ra1 and Il11 resulted in the exacerbation of DSS-induced colitis. Our analysis revealed that the MEK-ERK pathway, which was activated by ROS, contributed to the induction of IL-11 expression in colonic fibroblasts. The increase in IL-11 expression was regulated by LysM+ cells but not T cells or B cells in the colon of DSS-treated mice. Our study suggests that LysM+ cells regulated the expression of IL-11 in an ROS-dependent but not IL-1- or Myd88-dependent manner.

The numbers of apoptotic intestinal epithelial cells were increased in the colon of Il11ra1−/− and Il11−/− mice following DSS treatment. Along this line, IL-11 has been shown to inhibit cell death of cultured intestinal epithelial cells induced by X-ray irradiation,51 and IL-11 prevents apoptosis and accelerates recovery of small intestinal mucosa in mice treated with combined chemotherapy and radiation.52 Moreover, IEC-specific gain-of-function mutants of gp130-expressing mice exhibit less severe colitis and weight loss than WT mice, reduced colon shortening, and fewer CC3-positive cells in crypts during DSS-induced colitis.53 IEC-specific Stat3-deficient mice showed severe colitis with a higher number of apoptotic IECs after DSS treatment.36 Furthermore, we previously reported that IL-11 induces the gene expression of chemokines and matrix proteases in intestinal stromal cells.19 We showed that pSTAT3 signals were observed in both IL-11-producing fibroblasts and E-cadherin-positive IECs. Together, IL-11 attenuates DSS-induced colitis through two distinct mechanisms: (1) IL-11 suppresses apoptosis of intestinal epithelial cells, and (2) IL-11 regulates gene expression in intestinal stromal cells. On the other hand, we and others previously reported that tumor development was attenuated in Il11ra1−/− and Il11−/− mice using colitis-associated colorectal cancer models.19,54 This may be caused by the impaired postinjury regeneration of intestinal epithelial cells lacking IL-11, a limitation that would attenuate tumor development. Indeed, IL-11 induces the activation of STAT3 and ERK, which are known to promote cell survival and proliferation in murine tumor organoids.19,55

IL-11 expression is increased in the colon of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).24,23,56,57,25 High IL-11 levels predict severe colitis and lack of response to biological therapy.24 It has been reported that the colon samples of those who do not respond to anti-TNF antibody treatment contain IL-11-producing intestinal fibroblasts.25 On the other hand, polymorphisms in the IL11 gene have been associated with increased susceptibility to ulcerative colitis in human patients.58,59 Decreased expression of IL-11 is observed in patients with severe UC.23 In addition, reduced expression of IL11 in patients with necrotizing enterocolitis has been observed and may be involved in the pathogenesis.60,61 These observations suggest a beneficial function of IL-11 in IBD in the context of epithelial defense, and decreased expression of IL-11 might be one of the mechanisms of colitis exacerbation and involved in the pathogenesis. Indeed, several studies have reported that recombinant human IL-11 treatment has beneficial effects on the intestinal mucosa using different rodent models.29,28,62,63 The therapeutic efficiency of IL-11 administration has also been investigated in Crohn disease.64,65 However, in mouse experiments, it was suggested that recombinant human IL-11 may inhibit the function of mouse IL-11.30 In addition, transgenic overexpression of IL-11 in smooth muscle cells has been reported to cause colon shortening and colon dilation in mice, along with inflammation in the other organs.26 In their study, SMMHC-CreERT2 mice, which regulate gene expression in α-SMA+ smooth muscle cells, and Col1a2-CreER mice, which regulate gene expression in α-SMA+ vascular smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts, were used to induce IL-11 expression. In contrast, in DSS-treated mice, IL-11 expression was transient and localized, as IL-11-producing cells were observed only in the injured areas, and increased IL-11 expression was decreased by nine days after DSS treatment.19 We previously reported that IL-11-producing cells are predominantly α-SMA-negative fibroblasts in DSS-induced colitis and 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid-treated mice.19,20 Thus, our study suggests that IL-11 production is tightly regulated and that the function of IL-11 may be altered depending on the duration of IL-11 production and the tissue microenvironment.

In the present study, we showed that IL-11 production by fibroblasts is important for attenuating colitis. We also previously reported that IL-11-producing fibroblasts express several cytokines, including epiregulin and Fgf7.19 These cytokines have also been reported to be expressed in stromal cells of human patients with IBD.25,66,67 In addition, these cytokines have been reported to attenuate colitis and facilitate wound healing in mice.68,69,70 These reports indicate that the existence of IL-11-producing fibroblasts not only predicts colitis severity but that IL-11-producing fibroblasts also have diverse functions, and a more detailed analysis of molecular mechanisms mediated by fibroblasts will be important in understanding human pathogenesis.

RORγt+ Th17 cells and ILC3s produce IL-22 and IL-17 and play an important role in tissue homeostasis of the colon. Previous studies reported that IL-22 or IL-17 upregulates the expression of IL-11 in human colonic myofibroblasts and bronchial fibroblasts.13,15 Moreover, IL-1α, IL-1β, and TNFα increase the expression of IL-11 in intestinal myofibroblasts or rheumatoid synovial fibroblasts.14,71 However, we found that IL-11 expression was not decreased in the colon of Rag2−/− (lacking T and B cells), Rorc−/− (lacking Th17 cells and ILC3s), or Myd88−/− (deficient in IL-1 signaling) mice following DSS treatment. This difference in activation mechanisms is probably due to differences in the pattern of injury and the importance of activated cells in acute DSS-induced colitis in mice. Notably, we found that IL-11 production in fibroblasts was induced by ROS derived from LysM+ myeloid cells. Impaired barrier function triggered by DSS results in intestinal bacterial invasion into the lamina propria that subsequently induces ROS production by LysM+ myeloid cells. ROS play a crucial role in the elimination of bacteria.41,35 We previously reported that Il11 expression in the colon of DSS-treated mice was significantly decreased by antibiotic treatment.19 Although epithelial cells also express Duox and Nox, which produce ROS,72 this study revealed that myeloid cells are primarily responsible for ROS production and subsequent Il11 expression by fibroblasts in DSS-induced colitis.

Recent studies have highlighted that the IL-1 signaling pathway regulates intestinal homeostasis and the pathogenesis of colitis via stromal cells.73,74 Il1r1-deficient mice show increased susceptibility and a reduced regenerative response in Citrobacter rodentium infection and DSS-induced colitis. In Il1r1-deficient mice, the induction of R-spondin 3 (RSPO3), a WNT antagonist produced by fibroblasts, is decreased, leading to a reduced ability to repair tissue.73 In addition, a cohort study of patients with IBD showed that a subset of patients defined by high neutrophil infiltration and activation of fibroblasts at sites of ulceration matched nonresponders to several therapies. This study has shown that activated fibroblasts produce neutrophil chemoattractants in an IL-1R signaling-dependent manner. Interestingly, we revealed that although LysM+ myeloid cells are important for IL-1 upregulation in DSS-induced colitis,74 the IL-1-Myd88 axis is not involved in the induction of IL-11 in fibroblasts during colitis. Moreover, our study indicates that myeloid cells induce IL-11 expression by increasing oxidative stress. These findings suggest a novel mechanism of interaction between fibroblasts and myeloid cells and dysregulation of the mechanism that may contribute to the pathogenesis of IBD.

Limitations of the study

Our study showed the important role of IL-11 in attenuating intestinal inflammation in the DSS-induced acute colitis model. However, it is still unclear which types of IL11ra1-expressing cells are essential for attenuating DSS-induced colitis. Further analysis using conditional knockout Il11 or Il11ra1 mice should be performed in future studies to elucidate the molecular mechanisms in more detail and to exclude the possibility that developmental artifacts may exist in global knockout mice.30

Our study previously revealed that treatment with the ROS quencher N-acetyl-L-cysteine inhibited the increase in IL-11 during DSS-induced colitis.17 In addition, we showed that the activation of the ROS-ERK axis in fibroblasts is important for the induction of IL-11 expression in this study. However, all EGFP+ cells were not positive for pERK signals. In addition, not all stromal cells (α-SMA-positive cells and CD31-positive endothelial cells) express IL-11.17 These results indicate that factor(s) other than ROS may contribute to maintaining the properties of IL-11-producing cells.

In addition, although we used a DSS-induced colitis model, this model does not fully mimic human disease because ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease are chronic and recurrent inflammatory diseases. We think it is important to use models that more closely resemble human disease for analysis to advance our findings and to understand human IBD pathology.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Purified anti-beta-Actin antibody | BioLegend | 622102; RRID:AB_315946 |

| Phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (Thr202/Tyr204) antibody | CST | 4370; RRID:AB_2315112 |

| p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) Antibody | CST | 9102; RRID:AB_330744 |

| GFP (green fluorescent protein) antibody | Frontier Institute | GFP-Go-Af1480; RRID:AB_2571574 |

| Phospho-Stat3 (Tyr705) (D3A7) XP Rabbit mAb antibody | CST | 9145; RRID:AB_2491009 |

| Cleaved Caspase-3 (Asp175) Antibody | CST | 9661; RRID:AB_2341188 |

| CD68 (E3O7V) Rabbit mAb | CST | 97778 |

| Ly-6G (E6Z1T) Rabbit mAb antibody | CST | 87048; RRID:AB_2909808 |

| Donkey Anti-Rabbit IgG, Whole Ab ECL Antibody, HRP Conjugated | GE Healthcare | NA934; RRID:AB_772206 |

| Donkey anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor™ 488 | Invitrogen | A-21206; RRID:AB_2535792 |

| Donkey anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor™ 594 | Invitrogen | A-21207; RRID:AB_141637 |

| Donkey anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor™ Plus 594 | Invitrogen | A32754; RRID:AB_2762827 |

| Anti-Human/Mouse CD11b APC | TONBO biosciences | 20-0112; RRID:AB_2621556 |

| Anti-Mouse CD45.2 FITC | TONBO biosciences | 35-0454; RRID:AB_2621692 |

| PE anti-mouse CD45.2 Antibody | Biolegend | 109808; RRID:AB_313445 |

| FITC Rat anti-Mouse Ly-6G | BD Bioscience | 551460; RRID:AB_394207 |

| APC Anti-Mouse CD62L (L-Selectin) (MEL-14) antibody | TONBO biosciences | 20-0621; RRID:AB_2621582 |

| PE Anti-Human/Mouse CD44 (IM7) Antibody | TONBO biosciences | 50-0441; RRID:AB_2621762 |

| APC Anti-Mouse CD45.1 (A20) antibody | TONBO biosciences | 20-0453; RRID:AB_2621575 |

| ImmPRESS-VR Horse anti-Rabbit IgG Polymer kit | Vector laboratories | MP-6401 |

| Donkey anti-Goat IgG (H + L) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 | Invitrogen | A-11055; RRID:AB_2534102 |

| Fc gamma RIIb/CD16-2 (2.4G2) antibody | Made in house | N/A |

| Mouse IL-11 Biotinylated Antibody | R&D Systems | BAF418; RRID:AB_2296004 |

| Mouse IL-11 Antibody | R&D Systems | MAB4181, RRID:AB_2125627 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Recombinant IL-1 beta | Genzyme-Techne | N/A |

| Tissue-Tek® O.C.T. Compound | Sakura Finetek | 4583 |

| Sodium Dextran Sulfate MW36,000 - 50,000 | MP Biomedicals, Inc. | 160110 |

| RPMI 1640 with L-Gln, liquid | NACALAI TESQUE, INC. | 30264-56 |

| Collagenase | Wako | 032-22364 |

| DNase I | Roche | 11284932001 |

| TRI Reagent | Molecular Research Center, Inc. | TR118 |

| Sepasol-RNA I Super G | NACALAI TESQUE, INC. | 09379-55 |

| 10 %-Formaldehyde Neutral Buffer Solution | NACALAI TESQUE, INC. | 37152-51 |

| Citrate Buffer Solution | LSI Medicine | RM-102C |

| Hoechst 33252 | Dojindo | 343-07961 |

| CellROX™ Green Reagent, for oxidative stress detection | Invitrogen | C10444 |

| Fetal Bovine Serum | Gibco | 10270106 |

| Amphotericin B solution | SIGMA | A2942 |

| TSA PLUS CYANINE 3 50-150 SLIDES | AKOYA Biosciences | NEL744001KT |

| Biotin-16-dUTP | Roche | 11093070910 |

| Hydrogen Peroxide | NACALAI TESQUE, INC. | 18411-25 |

| 2-Mercaptoethanol | NACALAI TESQUE, INC. | 21418 |

| U0126 | Calbiochem | 662005 |

| SP600125 | Calbiochem | 420119 |

| SB 203580 | Calbiochem | 559389 |

| LY 294002 | Calbiochem | 440206 |

| Fixation and Permeabilization Solution | BD Biosciences | 554722 |

| Methanol | NACALAI TESQUE, INC. | 21914-74 |

| Triton® X-100 | Alfa aesar | N/A |

| Normal Donkey Serum | Jackson ImmunoResearch | 017-000-121 |

| MEM Non-Essential Amino Acids Solution(100x) | NACALAI TESQUE, INC. | 06344-56 |

| Recombinant Mouse IL-11 Protein | R&D Systems | 418-ML-025 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| RevertraAce qPCR RT Kit | TOYOBO | FSQ-101 |

| In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit | Roche Diagnostics | N/A |

| Can Get Signal® Immunoreaction Enhancer Solution | TOYOBO | NKB-101 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Il11-/- mice (Il11em1Tsak) | Deguchi et al., 201832 | MGI:6715991 |

| Il11ra1-/- mice (Il11ra1tm1Wehi) | Nandurkar et al., 199775 | MGI:2177778 |

| Rorcgfp/gfp (B6.129P2(Cg)-Rorctm2Litt/J) | Eberl et al., 200437 | Jackson Laboratory #007572 (RRID:IMSR_JAX:007572) |

| MyD88-/- | Adachi et al., 199850., Oriental Bioservice | IMSR_OBS:1 (C57BL/6) |

| Rag2-/- | Hao et al., 2001 | Jackson Laboratory #008449 |

| LysMDTR/+ Tg (B6; 129-Lyz2) | Miyake et al., 2007 | RBRC04394 |

| C57BL/6 | Japan-SLC | N/A |

| C57BL/6-SJL | Japan-SLC | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| See Table S1 for qPCR primers | N/A | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| ZEN software (Black Zen software) | Zeiss | RRID:SCR_018163 |

| FlowJo | FlowJo | RRID:SCR_008520 |

| GraphPad Prism 9 software | GraphPad | RRID:SCR_002798 |

| Fiji | Fiji | RRID:SCR_002285 |

| BZ-X Analyzer | Keyence | N/A |

| BD FACSDiva Software | BD Bioscience | RRID:SCR_001456 |

| 7500 SDS software | Thermo Fisher Scientific | N/A |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Dr. Takashi Nishina (takashi.nishina@med.toho-u.ac.jp).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents or materials. Any materials used in the study will be made available with a material transfer agreement.

Experimental model and subject details

Mice

Il11−/− mice32 (generated in our laboratory) and Il11ra1−/− mice75 (provided by L. Robb) were previously described. Rorcgfp/gfp37 (Jackson Laboratory #007572), MyD88−/−50 (Oriental Bioservice), Rag2−/− 76 (Jackson Laboratory #008449), and LysMDTR/+ mice43 were provided by the indicated sources and previously described. C57BL/6 (CD45.2+) and C57BL/6-SJL (CD45.1+) mice were purchased from Japan-SLC.

Male nine-to fifteen-week-old mice were used in this study. Mice were housed at 23 ± 2 °C, a humidity of 55 ± 5%, and a light/dark cycle of 12 h:12 h. Mice in different cages or derived from different sources were cohoused for 2 weeks to achieve a uniform microbiota composition before experiments. It has been reported that a few Il11ra1-deficient mice have a shortened and twisted snout.77 Mice that have a shortened and twisted snout were not included in this study. All animals were housed and maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions in the animal facility at Toho University School of Medicine. All experiments were performed according to the guidelines approved by the Institutional Animal Experiment Committee of Toho University School of Medicine (21-53-414, 21-53-411).

Method details

Reagents

The following antibodies used in this study were obtained from the indicated sources: anti-β-actin (622102, BioLegend), anti-phospho-ERK (4370, CST), anti-ERK (9102, CST), anti-GFP (GFP-Go-Af1480, Frontier Institute), anti-phospho-STAT3 (9145, CST), anti-cleaved caspase-3 (9661, CST), anti-CD68 (97778, CST) and anti-Ly-6G (87048, CST). Anti-horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (NA934) was purchased from GE Healthcare. Recombinant mouse IL-1β was obtained from Genzyme-Techne. Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (A21206), Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (A21207), Alexa Fluor Plus 594-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (A32754), and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG (A11055) antibodies were purchased from Invitrogen.

The following antibodies were used for flow cytometry and were obtained from the indicated sources: anti-human/mouse CD11b APC (20-0112, clone M1/70, TONBO Biosciences), anti-CD16/CD32-mAb (2.4G2) (made in-house), APC anti-mouse CD45.1 antibody (20-0453, clone A20, TONBO Biosciences), anti-mouse CD45.2 FITC (35-0454, clone 104, TONBO Biosciences), PE anti-mouse CD45.2 Antibody (109808, clone 104, Biolegend), and FITC rat anti-mouse Ly-6G (551460, Biolegend).

Induction of dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis in mice

Nine-to fifteen-week-old male mice received 1.5% DSS (MW: 36,000-50,000 Da; MP Biomedicals) ad libitum in their drinking water for five days, after which they received regular water again. The littermates and the genotypes were cohoused from birth or at least two weeks before and during the experiments to achieve a uniform microbiota composition.

Pathology scores of disease severity

Disease severity was estimated by scoring (1) infiltration of immune cells and (2) damage to epithelial cells as previously described.78 (1) The presence of inflammatory cells in the colonic lamina propria was counted as 0 = increased numbers of inflammatory cells, 1 = confluence of inflammatory cells, 2 = extension of inflammatory cells into the submucosa, and 3 = transmural extension of the inflammatory cell infiltrate. (2) The damage to epithelial cells was scored as follows: 0 = absence of mucosal damage, 1 = discrete focal lymphoepithelial lesions, 2 = mucosal erosion and ulceration, and 3 = extensive mucosal damage and extension through a deeper structure of the intestinal tract wall.

Flow cytometry

To obtain single cells from the colon, we minced mouse colons with scissors. We digested them in RPMI 1640 (Nacalai Tesque) containing 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 1 mg/mL collagenase (Wako), 0.5 mg/mL DNase (Roche), and 2% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco) for 60 min. Single-cell suspensions were prepared, and cells were stained with the indicated antibodies and analyzed by an LSRFortessa X-20 (BD Biosciences). Data were processed by FACSDiva Software (BD Bioscience) and FlowJo software (FlowJo).

Generation of bone marrow chimeras

For reciprocal BM transfer experiments, BM cells were prepared from LysM DTR/+ mice (CD45.2) or littermate wild-type mice. Then, 3-5×106 BM cells were transferred to 8-week-old recipient mice [C57BL/6-SJL mice (CD45.1)] that had been exposed to lethal irradiation (9.0 Gy).

At 8 weeks after transfer, peripheral blood mononuclear cells were collected and stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD45.1 and allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated anti-CD45.2 antibodies. The chimerism of bone marrow cells was calculated by counting the percentages of CD45.1+ and CD45.2+ cells by flow cytometry, and the average chimerism was more than 90%.

qPCR assays

Total RNA was extracted from the indicated tissues of mice by using TRI Reagent (Molecular Research Center) or Sepasol I Super G (Nacalai Tesque), and cDNAs were synthesized with the RevertraAce qPCR RT Kit (Toyobo). To remove residual DSS, we prepared mRNAs from the colon of mice treated with DSS and then purified mRNAs by LiCl precipitation as described previously.79 qPCR analysis was performed with the 7500 Real-Time PCR detection system with SYBR green method of the target genes and murine Hprt as an internal control with 7500 SDS software (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The primers used in this study are shown in Table S1.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Tissues were fixed in 10% formalin (Nacalai Tesque) and embedded in paraffin blocks. Paraffin-embedded colonic sections were used for H&E staining and immunohistochemical and immunofluorescence analyses. For immunohistochemistry, paraffin-embedded sections were treated with Instant Citrate Buffer Solution (RM-102C, LSI Medicine) appropriate to retrieve antigen. Then, tissue sections were stained with the indicated antibodies, followed by visualization of Alexa-conjugated secondary antibodies using Hoechst 33258 (Dojindo) or biotin-conjugated secondary antibodies followed by streptavidin-HRP (Vector Laboratories).

For the staining for pSTAT3, excised tissues were incubated in a fixation and permeabilization solution (554722, BD Bioscience) overnight followed by dehydration in 30% sucrose before embedding in OCT compound (Sakura Finetek) as described previously.80 Eighteen-micrometer sections were cut on a Tissue-Tek Polar cryostat (Sakura Finetek) and adhered to MAS-coated glass slides (MATSUNAMI). Frozen sections were treated with 0.3% H2O2 in methanol (Nacalai Tesque) for 20 min at −20°C and permeabilized and blocked in PBS containing 0.3% Triton X-100 (Alfa Aesar) and 5% normal donkey serum (Jackson Immunoresearch) followed by staining with primary antibodies diluted in PBS containing 5% BSA (Sigma‒Aldrich). Then, tissue sections were stained with Alexa-conjugated secondary antibodies, ImmPRESS-VR Horse anti-Rabbit IgG Polymer kit (MP-6401, Vector laboratories), and Hoechst 33,258. The TSA Plus Cyanine 3 System (NEL744001KT, AKOYA Biosciences) was used for the amplification of the pSTAT3-positive signal.

Pictures were obtained with an all-in-one microscope (BZ-X700, Keyence) and analyzed with BZ-X Analyzer (Keyence) software. Confocal microscopy was performed on an LSM 880 (Zeiss). Images were processed and analyzed using ZEN software (Zeiss) or Fiji’s image-processing package (https://fiji.sc/).

Isolation of colonic fibroblasts

Primary mouse colonic fibroblasts were obtained as described previously with some modifications.81 Briefly, we cut mouse colons into 0.5-1-cm pieces with scissors and washed them with HBSS containing 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 2.5 μg/mL amphotericin B (Sigma‒Aldrich). The pieces were incubated with HBSS containing antibiotics, 5 mM EDTA, and 1 mM DTT for 20 min at 37 °C on a shaker. The intestinal pieces were washed with HBSS containing the antibiotics and then incubated with RPMI 1640 containing 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, 2.5 μg/mL amphotericin B, 1 mg/mL collagenase (Wako), 0.5 mg/mL DNase (Roche), and 2% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco) for 60 min at 37 °C on a shaker. Single-cell suspensions were cultured in DMEM (Nacalai Tesque) containing 10% FBS, 0.0004% 2-mercaptoethanol (2-ME) (Nacalai Tesque), 1 mM HEPES, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, non-essential amino acids (Nacalai Tesque), and 2.5 μg/mL amphotericin B. Cells were stimulated with the indicated concentrations of H2O2 in the absence or presence of 20 μM SP600125 (Calbiochem), SB203580 (Calbiochem), U0126 (Calbiochem), or LY294002 (Calbiochem) for the indicated times in the absence of 2-ME.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 25 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM sodium fluoride, 1 mM PMSF, 1 μg/mL aprotinin, and 1 μg/mL leupeptin). After centrifugation, cell lysates were subjected to SDS–PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore). The membranes were developed with Super Signal West Dura extended duration substrate (Thermo Scientific) and analyzed by an Amersham Biosciences imager 600 (GE Healthcare). In some experiments, blots were quantified using the freeware program Fiji.

ELISA

Primary mouse colonic fibroblasts (5 × 105 cells/mL) were stimulated with the indicated concentrations of H2O2 for 12 h. Concentrations of murine IL-11 were determined by a sandwich ELISA with rat anti-mouse IL-11 antibody (MAB4181, R&D) as the capture antibody, biotin-conjugated goat anti-mouse IL-11 antibody (BAF418, R&D) as the detection antibody, and mouse IL-11 protein (R&D) as the standard. To increase detection sensitivity, the antibody was diluted in Can Get Signal Solution (NKB-101, TOYOBO).

Measurement of ROS levels

The intracellular ROS level was measured using CellROX-Green (Molecular Probes) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, single cells from the colon were labeled with a 1.7 μM CellROX-Green solution at 37 °C for 30 min, washed with 0.1% BSA/PBS, and then analyzed by flow cytometry.

Quantification and statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined by the unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test, Mann–Whitney U test, two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, and Mantel–Cox log rank test as indicated. ∗p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 9 software (GraphPad Software).

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Robb for the Il11ra1−/− mice, K. Honda for the Rorc-gfp/gfp mice, and M. Tanaka for the LysM DTR/+ mice. We thank M. Ohmuraya, K. Araki, and T. Yamamoto for generating Il11−/− mice and M. Ohtsuka for generating Il11-Egfp mice. We also thank N. Inohara; the members of the Atopy Research Center; Juntendo University; and our laboratory members for helpful discussion. This work was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) 20H03475 (to H.N.); Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) 19K07391 (to T.N.); 22K06932 (to T.N.) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS); the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) through AMED-CREST (JP20gm1210002, to H.N.); Extramural Collaborative Research Grant of Cancer Research Institute, Kanazawa University (to T.N., and H.N.); the Project Research Grant of Initiative for Realizing Diversity in the Research Environment, Toho University (to T.N.); and research grants from the Uehara Memorial Foundation (to T.N.), the SGH Foundation (to T.N.), the Koyanagi-Foundation (to T.N.), the Takeda Science Foundation (to T.N.), the Okinaka Memorial Institute for Medical Research (to T.N.), The Mochida Memorial Foundation for Medical and Pharmaceutical Research (to T.N.), the Ube kosan Foundation (to T.N.), Toho University Grant for Research Initiative Program (TUGRIP) (to H.N.), the Science Research Promotion Fund, and The Promotion and Mutual Aid Corporation for Private Schools of Japan (to S.Y., and H.N.).

Author contributions

Conceptualization, T.N. and H.N.; Investigation, T.N., Y.D., M.K., and X.C.; Resources, S.Y. and T.M.; Writing – Original Draft, T.N. and H.N.; Writing – Review & Editing, T.N. and H.N.; Project Administration, T.N. and H.N.; Funding Acquisition, T.N. and H.N.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that no competing interests exist.

Published: February 17, 2023

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2023.105934.

Contributor Information

Takashi Nishina, Email: takashi.nishina@med.toho-u.ac.jp.

Hiroyasu Nakano, Email: hiroyasu.nakano@med.toho-u.ac.jp.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its supplementary information files. This study did not generate novel code, software, or algorithms. No data were generated that required submission in public repositories. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

References

- 1.Peterson L.W., Artis D. Intestinal epithelial cells: regulators of barrier function and immune homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014;14:141–153. doi: 10.1038/nri3608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leoni G., Neumann P.A., Sumagin R., Denning T.L., Nusrat A. Wound repair: role of immune-epithelial interactions. Mucosal Immunol. 2015;8:959–968. doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurashima Y., Kiyono H. Mucosal ecological network of epithelium and immune cells for gut homeostasis and tissue healing. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2017;35:119–147. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-051116-052424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Powell D.W., Pinchuk I.V., Saada J.I., Chen X., Mifflin R.C. Mesenchymal cells of the intestinal lamina propria. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2011;73:213–237. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nowarski R., Jackson R., Flavell R.A. The stromal intervention: regulation of immunity and inflammation at the epithelial-mesenchymal barrier. Cell. 2017;168:362–375. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Souza H.S.P., Fiocchi C. Immunopathogenesis of IBD: current state of the art. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016;13:13–27. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Henderson P., van Limbergen J.E., Schwarze J., Wilson D.C. Function of the intestinal epithelium and its dysregulation in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2011;17:382–395. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wirtz S., Neufert C., Weigmann B., Neurath M.F. Chemically induced mouse models of intestinal inflammation. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:541–546. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okayasu I., Hatakeyama S., Yamada M., Ohkusa T., Inagaki Y., Nakaya R. A novel method in the induction of reliable experimental acute and chronic ulcerative colitis in mice. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:694–702. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90290-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giraldez M.D., Carneros D., Garbers C., Rose-John S., Bustos M. New insights into IL-6 family cytokines in metabolism, hepatology and gastroenterology. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021;18:787–803. doi: 10.1038/s41575-021-00473-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fung K.Y., Louis C., Metcalfe R.D., Kosasih C.C., Wicks I.P., Griffin M.D.W., Putoczki T.L. Emerging roles for IL-11 in inflammatory diseases. Cytokine. 2022;149:155750. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2021.155750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lokau J., Kespohl B., Kirschke S., Garbers C. The role of proteolysis in interleukin-11 signaling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Mol. Cell Res. 2022;1869:119135. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2021.119135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andoh A., Zhang Z., Inatomi O., Fujino S., Deguchi Y., Araki Y., Tsujikawa T., Kitoh K., Kim-Mitsuyama S., Takayanagi A., et al. Interleukin-22, a member of the IL-10 subfamily, induces inflammatory responses in colonic subepithelial myofibroblasts. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:969–984. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.06.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bamba S., Andoh A., Yasui H., Makino J., Kim S., Fujiyama Y. Regulation of IL-11 expression in intestinal myofibroblasts: role of c-Jun AP-1- and MAPK-dependent pathways. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2003;285:G529–G538. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00050.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Molet S., Hamid Q., Davoine F., Nutku E., Taha R., Pagé N., Olivenstein R., Elias J., Chakir J. IL-17 is increased in asthmatic airways and induces human bronchial fibroblasts to produce cytokines. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2001;108:430–438. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.117929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang W., Yang L., Yang Y.C., Leng S.X., Elias J.A. Transforming growth factor-beta stimulates interleukin-11 transcription via complex activating protein-1-dependent pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:5506–5513. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishina T., Komazawa-Sakon S., Yanaka S., Piao X., Zheng D.-M., Piao J.-H., Kojima Y., Yamashina S., Sano E., Putoczki T., et al. Interleukin-11 links oxidative stress and compensatory proliferation. Sci. Signal. 2012;5:ra5. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nishina T., Deguchi Y., Miura R., Yamazaki S., Shinkai Y., Kojima Y., Okumura K., Kumagai Y., Nakano H. Critical contribution of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2) to electrophile-induced interleukin-11 production. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292:205–216. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.744755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishina T., Deguchi Y., Ohshima D., Takeda W., Ohtsuka M., Shichino S., Ueha S., Yamazaki S., Kawauchi M., Nakamura E., et al. Interleukin-11-expressing fibroblasts have a unique gene signature correlated with poor prognosis of colorectal cancer. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:2281. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22450-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takeda W., Nishina T., Deguchi Y., Kawauchi M., Mikami T., Yagita H., Nishiyama C., Nakano H. Stromal fibroblasts produce interleukin-11 in the colon of TNBS-treated mice. Toho J Med. 2020;6:111–120. doi: 10.14994/tohojmed.2020-003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jasso G.J., Jaiswal A., Varma M., Laszewski T., Grauel A., Omar A., Silva N., Dranoff G., Porter J.A., Mansfield K., et al. Colon stroma mediates an inflammation-driven fibroblastic response controlling matrix remodeling and healing. PLoS Biol. 2022;20:e3001532. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3001532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klein W., Rohde G., Arinir U., Hagedorn M., Dürig N., Schultze-Werninghaus G., Epplen J.T. A promotor polymorphism in the Interleukin 11 gene is associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Electrophoresis. 2004;25:804–808. doi: 10.1002/elps.200305773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sabzevary-Ghahfarokhi M., Shohan M., Shirzad H., Rahimian G., Bagheri N., Soltani A., Deris F., Ghatreh-Samani M., Razmara E. The expression analysis of Fra-1 gene and IL-11 protein in Iranian patients with ulcerative colitis. BMC Immunol. 2018;19:17. doi: 10.1186/s12865-018-0257-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arijs I., Quintens R., Van Lommel L., Van Steen K., De Hertogh G., Lemaire K., Schraenen A., Perrier C., Van Assche G., Vermeire S., et al. Predictive value of epithelial gene expression profiles for response to infliximab in Crohn's disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2010;16:2090–2098. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smillie C.S., Biton M., Ordovas-Montanes J., Sullivan K.M., Burgin G., Graham D.B., Herbst R.H., Rogel N., Slyper M., Waldman J., et al. Intra- and inter-cellular rewiring of the human colon during ulcerative colitis. Cell. 2019;178:714–730.e22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lim W.W., Ng B., Widjaja A., Xie C., Su L., Ko N., Lim S.Y., Kwek X.Y., Lim S., Cook S.A., Schafer S. Transgenic interleukin 11 expression causes cross-tissue fibro-inflammation and an inflammatory bowel phenotype in mice. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0227505. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuenzler K.A., Pearson P.Y., Schwartz M.Z. Interleukin-11 enhances intestinal absorptive function after ischemia-reperfusion injury. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2002;37:457–459. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2002.30861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qiu B.S., Pfeiffer C.J., Keith J.C., Jr. Protection by recombinant human interleukin-11 against experimental TNB-induced colitis in rats. Dig. Dis. Sci. 1996;41:1625–1630. doi: 10.1007/BF02087911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gibson D.L., Montero M., Ropeleski M.J., Bergstrom K.S.B., Ma C., Ghosh S., Merkens H., Huang J., Månsson L.E., Sham H.P., et al. Interleukin-11 reduces TLR4-induced colitis in TLR2-deficient mice and restores intestinal STAT3 signaling. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1277–1288. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Widjaja A.A., Dong J., Adami E., Viswanathan S., Ng B., Pakkiri L.S., Chothani S.P., Singh B.K., Lim W.W., Zhou J., et al. Redefining IL11 as a regeneration-limiting hepatotoxin and therapeutic target in acetaminophen-induced liver injury. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021;13:eaba8146. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aba8146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sims N.A., Jenkins B.J., Nakamura A., Quinn J.M.W., Li R., Gillespie M.T., Ernst M., Robb L., Martin T.J. Interleukin-11 receptor signaling is required for normal bone remodeling. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2005;20:1093–1102. doi: 10.1359/Jbmr.050209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Deguchi Y., Nishina T., Asano K., Ohmuraya M., Nakagawa Y., Nakagata N., Sakuma T., Yamamoto T., Araki K., Mikami T., et al. Generation of and characterization of anti-IL-11 antibodies using newly established Il11-deficient mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018;505:453–459. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.09.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eichele D.D., Kharbanda K.K. Dextran sodium sulfate colitis murine model: an indispensable tool for advancing our understanding of inflammatory bowel diseases pathogenesis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017;23:6016–6029. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i33.6016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reczek C.R., Chandel N.S. ROS-dependent signal transduction. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2015;33:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mittal M., Siddiqui M.R., Tran K., Reddy S.P., Malik A.B. Reactive oxygen species in inflammation and tissue injury. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2014;20:1126–1167. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.5149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pickert G., Neufert C., Leppkes M., Zheng Y., Wittkopf N., Warntjen M., Lehr H.A., Hirth S., Weigmann B., Wirtz S., et al. STAT3 links IL-22 signaling in intestinal epithelial cells to mucosal wound healing. J. Exp. Med. 2009;206:1465–1472. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Eberl G., Marmon S., Sunshine M.J., Rennert P.D., Choi Y., Littman D.R. An essential function for the nuclear receptor RORgamma(t) in the generation of fetal lymphoid tissue inducer cells. Nat. Immunol. 2004;5:64–73. doi: 10.1038/ni1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ivanov I.I., McKenzie B.S., Zhou L., Tadokoro C.E., Lepelley A., Lafaille J.J., Cua D.J., Littman D.R. The orphan nuclear receptor RORgammat directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell. 2006;126:1121–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shindo R., Ohmuraya M., Komazawa-Sakon S., Miyake S., Deguchi Y., Yamazaki S., Nishina T., Yoshimoto T., Kakuta S., Koike M., et al. Necroptosis of intestinal epithelial cells induces type 3 innate lymphoid cell-dependent lethal ileitis. iScience. 2019;15:536–551. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2019.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cross M., Mangelsdorf I., Wedel A., Renkawitz R. Mouse lysozyme M gene: isolation, characterization, and expression studies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:6232–6236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.17.6232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dupré-Crochet S., Erard M., Nüβe O. ROS production in phagocytes: why, when, and where? J. Leukoc. Biol. 2013;94:657–670. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1012544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jakubzick C., Bogunovic M., Bonito A.J., Kuan E.L., Merad M., Randolph G.J. Lymph-migrating, tissue-derived dendritic cells are minor constituents within steady-state lymph nodes. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205:2839–2850. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miyake Y., Kaise H., Isono K.I., Koseki H., Kohno K., Tanaka M. Protective role of macrophages in noninflammatory lung injury caused by selective ablation of alveolar epithelial type II Cells. J. Immunol. 2007;178:5001–5009. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.5001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saito M., Iwawaki T., Taya C., Yonekawa H., Noda M., Inui Y., Mekada E., Kimata Y., Tsuru A., Kohno K. Diphtheria toxin receptor-mediated conditional and targeted cell ablation in transgenic mice. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001;19:746–750. doi: 10.1038/90795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kurosawa T., Miyoshi S., Yamazaki S., Nishina T., Mikami T., Oikawa A., Homma S., Nakano H. A murine model of acute lung injury identifies growth factors to promote tissue repair and their biomarkers. Gene Cell. 2019;24:112–125. doi: 10.1111/gtc.12659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qualls J.E., Kaplan A.M., van Rooijen N., Cohen D.A. Suppression of experimental colitis by intestinal mononuclear phagocytes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2006;80:802–815. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1205734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bauer C., Duewell P., Mayer C., Lehr H.A., Fitzgerald K.A., Dauer M., Tschopp J., Endres S., Latz E., Schnurr M. Colitis induced in mice with dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) is mediated by the NLRP3 inflammasome. Gut. 2010;59:1192–1199. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.197822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jiang X., Yu J., Shi Q., Xiao Y., Wang W., Chen G., Zhao Z., Wang R., Xiao H., Hou C., et al. Tim-3 promotes intestinal homeostasis in DSS colitis by inhibiting M1 polarization of macrophages. Clin. Immunol. 2015;160:328–335. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Deguine J., Barton G.M. MyD88: a central player in innate immune signaling. F1000Prime Rep. 2014;6:97. doi: 10.12703/P6-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Adachi O., Kawai T., Takeda K., Matsumoto M., Tsutsui H., Sakagami M., Nakanishi K., Akira S. Targeted disruption of the MyD88 gene results in loss of IL-1- and IL-18-mediated function. Immunity. 1998;9:143–150. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80596-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Uemura T., Nakayama T., Kusaba T., Yakata Y., Yamazumi K., Matsuu-Matsuyama M., Shichijo K., Sekine I. The protective effect of interleukin-11 on the cell death induced by X-ray irradiation in cultured intestinal epithelial cell. J. Radiat. Res. 2007;48:171–177. doi: 10.1269/jrr.06047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Orazi A., Du X., Yang Z., Kashai M., Williams D.A. Interleukin-11 prevents apoptosis and accelerates recovery of small intestinal mucosa in mice treated with combined chemotherapy and radiation. Lab. Invest. 1996;75:33–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Taniguchi K., Wu L.W., Grivennikov S.I., de Jong P.R., Lian I., Yu F.X., Wang K., Ho S.B., Boland B.S., Chang J.T., et al. A gp130-Src-YAP module links inflammation to epithelial regeneration. Nature. 2015;519:57–62. doi: 10.1038/nature14228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Putoczki T.L., Thiem S., Loving A., Busuttil R.A., Wilson N.J., Ziegler P.K., Nguyen P.M., Preaudet A., Farid R., Edwards K.M., et al. Interleukin-11 is the dominant IL-6 family cytokine during gastrointestinal tumorigenesis and can be targeted therapeutically. Cancer Cell. 2013;24:257–271. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eissmann M.F., Dijkstra C., Jarnicki A., Phesse T., Brunnberg J., Poh A.R., Etemadi N., Tsantikos E., Thiem S., Huntington N.D., et al. IL-33-mediated mast cell activation promotes gastric cancer through macrophage mobilization. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:2735. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10676-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.West N.R., Hegazy A.N., Owens B.M.J., Bullers S.J., Linggi B., Buonocore S., Coccia M., Görtz D., This S., Stockenhuber K., et al. Oncostatin M drives intestinal inflammation and predicts response to tumor necrosis factor-neutralizing therapy in s with inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Med. 2017;23:579–589. doi: 10.1038/nm.4307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nayar S., Morrison J.K., Giri M., Gettler K., Chuang L.S., Walker L.A., Ko H.M., Kenigsberg E., Kugathasan S., Merad M., et al. A myeloid-stromal niche and gp130 rescue in NOD2-driven Crohn's disease. Nature. 2021;593:275–281. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03484-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Klein W., Tromm A., Griga T., Fricke H., Folwaczny C., Hocke M., Eitner K., Marx M., Duerig N., Epplen J.T. A polymorphism in the IL11 gene is associated with ulcerative colitis. Genes Immun. 2002;3:494–496. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Putoczki T.L., Dobson R.C.J., Griffin M.D.W. The structure of human interleukin-11 reveals receptor-binding site features and structural differences from interleukin-6. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2014;70:2277–2285. doi: 10.1107/S1399004714012267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nadler E.P., Stanford A., Zhang X.R., Schall L.C., Alber S.M., Watkins S.C., Ford H.R. Intestinal cytokine gene expression in infants with acute necrotizing enterocolitis: interleukin-11 mRNA expression inversely correlates with extent of disease. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2001;36:1122–1129. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2001.25726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pan H.X., Zhang C.S., Lin C.H., Chen M.M., Zhang X.Z., Yu N. Mucin 1 and interleukin-11 protein expression and inflammatory reactions in the intestinal mucosa of necrotizing enterocolitis children after surgery. World J. Clin. Cases. 2021;9:7372–7380. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i25.7372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Boerma M., Wang J., Burnett A.F., Santin A.D., Roman J.J., Hauer-Jensen M. Local administration of interleukin-11 ameliorates intestinal radiation injury in rats. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9501–9506. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]