Abstract

Study Design.

A cross-sectional observational study utilizing the National Ambulatory and National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Surveys between 1997 and 2010.

Objective.

The aim of this study was to characterize national physical therapy (PT) referral trends during primary care provider (PCP) visits in the United States.

Summary of Background Data.

Despite guidelines recommending PT for the initial management of low back pain (LBP), national PT referral rates remain low.

Methods.

Race, ethnicity, age, payer type, and PT referral rates were collected for patients aged 16 to 90 years who were visiting their PCPs. Associations among demographic variables and PT referral were determined using logistic regression.

Results.

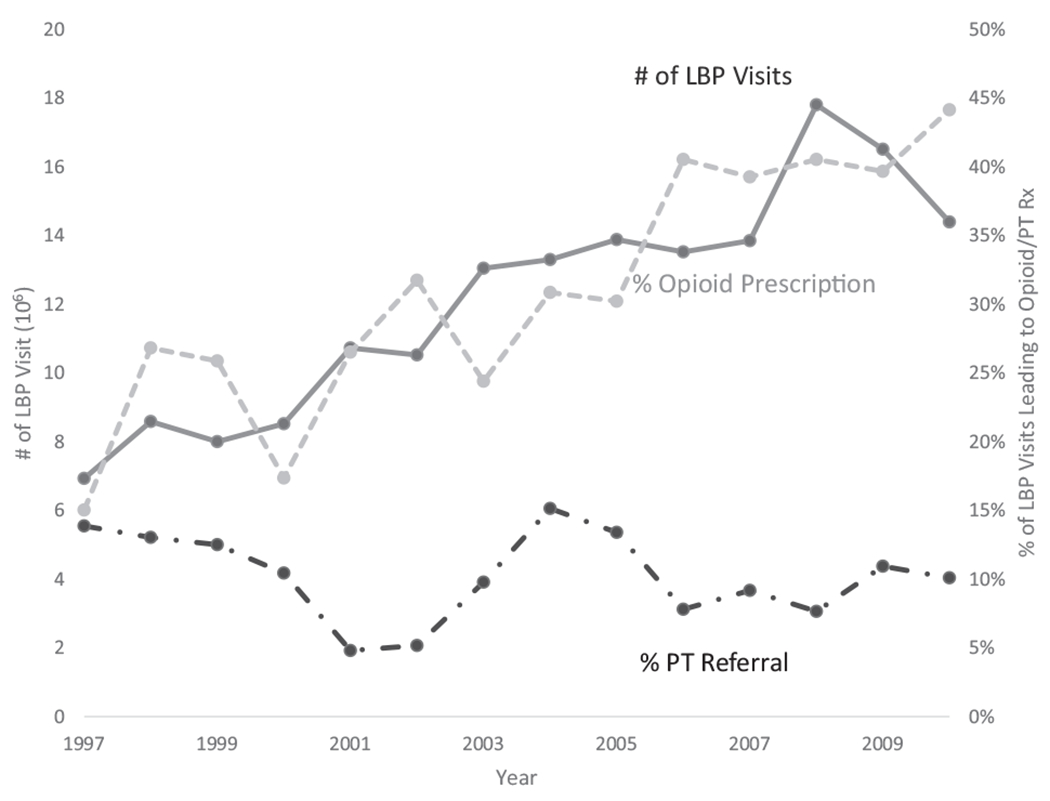

Between 1997 and 2010, we estimated 170 million visits for LBP leading to 17.1 million PT referrals. Average proportion of PCP visits associated with PT referrals remained stable at about 10.1% [odds ratio (OR) 1.00, 95% confidence interval (95% CI) 0.96–1.04)], despite our prior finding of increasing number of visits associated with opioid prescriptions in the same timeframe.

Lower PT referral rates were observed among visits by patients who were insured by Medicaid (OR 0.48, 95% CI 0.33–0.69) and Medicare (OR 0.50, 95% CI 0.35–0.72). Furthermore, visits not associated with PT referrals were more likely to be associated with opioid prescriptions (OR 1.69, 95% CI 1.22–2.35).

Conclusion.

Although therapies delivered by PTs are promoted as a first-line treatment for LBP, PT referral rates remain low. There also exist disparately lower referral rates in populations with more restrictive health plans and simultaneous opioid prescription. Our findings provide a broad overview to PT prescription trend and isolate concerning associations requiring further explorations.

Keywords: chronic pain, epidemiology, insurer status, low back pain, opioid prescription, physical therapy, primary care, socioeconomic disparity, temporal trend, therapy

Low back pain (LBP) has a lifetime incidence of 11% to 80% in Americans.1,2 It accounts for one of the leading reasons for physician visits, health care utilization,3,4 and disability reported globally.5 Concerningly, the health care burden of LBP is likely to rise, as studies show that the overall prevalence of LBP has been increasing in the last decades.3,6

Multiple national and international guidelines have recommended education, exercise therapy, spinal manipulation, acupuncture, massage, and psychological therapies as initial management strategies for LBP, especially given their benign safety profiles.7 Physical therapists (PTs) are among those able to prescribe the recommended tailored exercises, manual therapy (massage, mobilization, manipulation) as well as individualized education, though individual PTs’ treatment choices can vary from evidence-based practice recommendations.8 Evidence suggests that earlier referral to PT can lead to sooner return to work,9 and PT referral in general might decrease utilization of prescriptions, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and injections resulting in lower overall medical costs in the treatment of LBP.10–13 As such, multiple national guidelines have recommended forms of PT for the management of LBP.14,15

Despite such evidence in support of PT, national referral rates are estimated to be only 7% to 20%.10,11 Recently, Mafi et al.16 found that although the number of visits for LBP is increasing, the overall national PT referral trends from 1999 to 2010 have remained stable. This is in sharp contrast to increasing opioid prescription in the same population,16,17 despite the lack of evidence and guidelines supporting the use of opioids for the treatment of chronic LBP. However, the influence of demographic and socioeconomic variables on PT referral patterns remains unexplored. Here, we used the same national surveys to further characterize patterns of PT referrals during clinic visits with primary care providers (PCPs).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data Source

Our analysis utilized data from the national surveys National Hospital and Ambulatory Medical Center Survey (NHAMCS) and National Ambulatory Medical Center Survey (NAMCS) administered by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) as well as sample survey data obtained from Emergency Departments (EDs). These two surveys are designed to collect nationally representative information about ambulatory medical care services in the United States. Data are obtained for a sample of visits to nonfederal-employed, office-based physicians (NAMCS), and outpatient departments (NHAMCS). Specially trained interviewers from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) visit the physicians and conduct training before survey administration. Each physician is randomly assigned to a 1-week reporting period, during which a random sample of visits are recorded by the physician or office staff. Data obtained include the patients’ symptoms, physicians’ diagnoses, and medications ordered or provided; demographics; and ambulatory services provided, including diagnostic procedures, patient management, and planned future treatment.

For this study, we analyzed survey data from clinics collected in NHAMCS and NAMCS between the years 1997 and 2010. Only visits for patients between ages 16 and 90 years were considered. Complete data were considered because missing data fields were rare.

Back Pain Visits

For outpatient clinic surveys, ICD-9 codes indicating a diagnosis of back pain were utilized to examine the incidence of back pain related diagnoses as we previously detailed:17 353.1, lumbosacral plexus lesions; 722.1, displacement of thoracic or lumbar intervertebral disk without myelopathy; 722.52, degeneration of lumbar or lumbosacral intervertebral disk; 722.83, postlaminectomy syndrome, lumbar region; 724.02, spinal stenosis, lumbar region, without neurogenic claudication; 724.2, lumbago; 724.4, thoracic or lumbosacral neuritis or radiculitis, unspecified; 724.5, backache, unspecified; 738.4, acquired spondylolisthesis; 739.3, nonallopathic lesions, lumbar region; 756.1, congenital anomalies of spine; 756.12, spondylolisthesis; 839.2, closed dislocation thoracic and lumbar vertebra; 846, sprains and strains of sacroiliac region; 847.2, sprain of lumbar; and 847.9, and sprain of unspecified site of back.

Demographic Variables

Patient race and ethnicity were summarized using the provided variables from the databases. Age was broken down into four groups: 16 to 29, 30 to 44, 45 to 59, and 60 to 90 years. This grouping was chosen to create comparably sized groups to maximize descriptive power. Gender was obtained directly from the databases. We created a three-level race/ethnicity variable of white, black, and patients of any race who identified as Hispanic.

Primary Care Physician

This study focused on visits seen by primary care physicians (PCPs). In both NHAMCS and NAMCS, the “PRIMCARE” variable was employed to analyze the subset of ambulatory visits attributable to PCPs.

Insurance Payer Source

The primary insurance payer source is reported in both NHAMCS and NAMCS. There is a slight coding change in the year 2005 that may impact the subpopulation with two or more insurances. A binary variable is created to indicate Medicaid or self-pay as the primary insurance source, and another variable created to indicate Medicare as the primary insurance source. Medicare is the federal United States health insurance for patients 65 years of age or older or younger patients with certain disabilities and end-stage renal disease. Medicaid is a joint federal and state program that helps with medical costs for some people with limited income and resources.

Opioid Prescription

As previously described in more detail,17 similar procedures were adopted for all ambulatory settings to code for the prescription of opioid medications. As previously explained, for 2006 to 2010, the prescription category variables were used, and values based on Multum’s therapeutic classification “CNS; analgesics; narcotic” and “CNS; analgesics; narcotic analgesic combinations” were employed to indicate the prescription of opioid medications. For 1997 to 2005, National Drug Code Directory, 1995 edition, drug classification was employed, with the value “analgesics-narcotic” indicating prescription of opioid medications. Manual inspection identified occasional discrepancies in coding, which were reconciled before analyses.

Physical Therapy

Physical therapy referral was available and coded as “physioth” between 1997 and 2004 and as “PT” between 2005 and 2010. The surveys did not state specific definitions for physical therapy.

Statistical Modeling

NAMCS and NHAMCS nonrandomly sampled clusters of practices, clinics, and hospitals. Hence, frequency of visits associated with LBP, physical therapy referral, demographic variables, and payer source were analyzed using weighted survey frequency estimation procedures in SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) released by the National Center for Health Statistics. To ensure that no additional bias was added during the analysis of the subpopulations of interest, domain analysis was employed to compute statistics for subpopulations of interest by using the entire sample to estimate the variance of domain estimates. Initially, a univariate analysis was used to estimate the odds ratio (OR) of each covariate—year (as compared with 1997), female gender (as compared with male gender), black race (as compared with white race), Hispanic ethnicity (as compared with non-Hispanic), Medicare (as compared with private pay), and Medicaid (as compared with private pay). Subsequently, a multivariable analysis using weighted logistic regression was used to estimate the adjusted ORs while controlling for other significant covariates (P < 0.05)—year, gender, race, ethnicity, payer status, opioids. The outcome was the probability of a given visit leading to a physical therapy referral.

RESULTS

Between 1997 and 2010, we estimated 170 million visits for LBP leading to 17.1 million PT referrals (Table 1). The average age of patients seen at visits for LBP with PT referral was 50.4 years; 84.5 million (49.3%) were female; 19.8 million were White, 12.4 million were Black, and 2.3 million were Hispanic. About 22.3 million patients had Medicare, and 2.0 million had Medicaid as the primary insurance (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Trend of PT Referral From PCP Visits for LBP

| # LBP Visits | # PT Referral | Percentage of # LBP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 169,666,459 | 17,147,184 | 10.1 |

| 1997 | 6,933,323 | 961,963 | 13.9 |

| 1998 | 8,589,861 | 1,120,063 | 13.0 |

| 1999 | 8,005,355 | 1,001,426 | 12.5 |

| 2000 | 8,526,785 | 890,674 | 10.4 |

| 2001 | 10,732,439 | 516,051 | 4.8 |

| 2002 | 10,527,373 | 545,027 | 5.2 |

| 2003 | 13,052,197 | 1,277,625 | 9.8 |

| 2004 | 13,304,436 | 2,015,460 | 15.1 |

| 2005 | 13,886,533 | 1,862,488 | 13.4 |

| 2006 | 13,529,802 | 1,057,260 | 7.8 |

| 2007 | 13,853,822 | 1,272,089 | 9.2 |

| 2008 | 17,808,220 | 1,363,498 | 7.7 |

| 2009 | 16,515,770 | 1,808,478 | 11.0 |

| 2010 | 14,400,543 | 1,455,082 | 10.1 |

LBP indicates low back pain; PT, physical therapist.

TABLE 2.

Patient Characteristics of PT Referral From PCP Visits for LBP

| # LBP Visits | # PT Referral | Percentage of # PT | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16–29 | 16,301,616 | 2,021,779 | 11.8 |

| 30–44 | 46,829,374 | 5,653,156 | 33.0 |

| 45–59 | 60,748,191 | 6,239,246 | 36.4 |

| 60–90 | 45,787,278 | 3,233,003 | 18.9 |

| Female sex | 96,063,528 | 8,450,777 | 49.3 |

| Black race | 496,053,166 | 6,405,611 | 37.4 |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 447,611,104 | 4,984,976 | 29.1 |

| Medicare insurance | 30,563,538 | 1,828,563 | 10.7 |

| Medicaid insurance | 29,903,167 | 1,958,836 | 11.4 |

LBP indicates low back pain; PT, physical therapist.

Average number of PCP visits associated with PT referrals had remained stable over this time period at about 10.1% (OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.96–1.04; Figure 1; Table 1), despite our prior finding of increasing number of visits associated with opioid prescriptions in this same population.17 Lower PT referral rates were observed among visits by patients who were insured by Medicaid (OR 0.48, 95% CI 0.33–0.69) and Medicare (OR 0.50, 95% CI 0.35–0.72) (Table 3). Furthermore, visits not associated with PT referrals were more likely to be associated with opioid prescriptions (OR 1.69, 95% CI 1.22–2.35).

Figure 1.

Temporal trends in physical therapy and opioid prescriptions associated with visits for low back pain.

TABLE 3.

Predictors of Physical Therapy Referral

| Covariate | Adjusted Odds Ratio |

|---|---|

| Year (as compared with 1997) | 1.00 (0.96–1.04) |

| Female gender | 0.75 (0.57–1.00) |

| Black race (as compared with white race) | 0.91 (0.56–1.47) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 1.18 (0.78–1.80) |

| Medicare | 0.47 (0.32–0.68) |

| Medicaid | 0.54 (0.37–0.79) |

| Opioid prescription | 0.57 (0.41–0.80) |

Odds ratios reported are associated with physical therapy referral (95% confidence interval).

DISCUSSION

The PT referral rates observed during PCP visits between 1997 and 2010 have remained stable. We noted disparities in PT referral rates during PCP visits by Medicaid and Medicare-insured patients and in patients who received simultaneous opioid prescription. Although this population-based study lacks the individual patient granularity needed to differentiate between new versus repeat visits and referrals along with individual patient differences that may explain for the trends observed, we believe that our results prompt further studies to characterize these socioeconomic disparities in PT referral.

The ideal physical therapy referral rate has yet to be defined. The 10.1% noted in our study is in the middle of the range previously described.10,11 Fritz et al.10 noted that in a national database of employer-sponsored health plans, about 7% of patients with LBP were referred for physical therapy. However, studies of workers compensated for back injuries, who have been previously documented to be most likely referred to physical therapy, reveal referral rates as high as 18% to 27%.6,11

One proposed explanation for the stable low rates of PT referral would be increased visits to PCP for less severe back pain. We do not agree this is the case, as in both Mafi’s analysis and prior work by our group on this same population, there has been an increasing number of visits associated with opioid prescriptions.16,17 This observation of increased opioid rates suggest that additional visits include people with nontrivial pain and counters the argument that the stable low rates of PT referral would be increased visits to PCP for less severe back pain.

Here, we also found that patients who are not referred to PT are more likely to receive opioid prescriptions. Although our study was not equipped to answer why this association exists, this finding needs to be further validated and explored. One can conjecture that cost can be a driving issue. One systematic review suggests that 17% of all direct medical costs for lower back pain was spent on physical therapy.18 In comparison, the cost of opioid prescriptions can be as low as $22 to $109 in terms of Medicare reimbursement per prescription after visit for each person treated with back pain.19 However, although opioid prescription may be cheaper in the shorter run, the direct cost of opioids abuse has been estimated to be 8.6 billion dollars.20 Indeed, as aberrant medication-taking behaviors occur in up to 24% of patients receiving opioids for chronic back pain,21 the rising rates of opioid prescriptions likely are contributing to the rising opioid analgesic abuse and addiction.22 With more evidence that PT is an effective method of treating back pain,10–13 there needs to be a push for more insurance coverage of PT referrals to avoid overutilization of cheaper but less effective, and potentially harmful, forms of treatments.

The decreased access based on payer status we noted has been previously described. In other fields of medicine, payer status has been associated with disparate access to laparoscopic surgeries,23,24 cardiac outcomes,25,26 and even mortality.27 Fewer studies have looked specifically at how payer status impact management of LBP. Freburger et al.6 noted that the rate of referral to physical therapy was 11.6% for Medicaid paid PCP visits as compared with 17.7% for visits paid by private insurance, Medicare, worker’s compensation, or self-pay. Previously, Fritz et al.10 have shown through analysis of an employer-sponsored health plan that patients insured through a Preferred Provider Organization (PPO) plan were more likely to receive early treatment from a PT (53.4%) as compared with those insured through a Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) plan (44.7%). The reason for these disparities is unclear. Perhaps, PCPs, who often serve as gatekeepers of care, feel obligated to be more cost-effective as historically, PCPs working for HMOs have lower mean total estimated outpatient charges than orthopedic surgeons and chiropractors when caring for patients with LBP.28 These disconcerting economic disparities need to be quantified, elucidated, and addressed.

Our study is limited by the lack patient granularity, which limits our ability to differentiate new versus repeat visits for LBP and PT referrals. Although the visits analyzed were all for a primary diagnosis of LBP, we cannot be sure that patients were referred to physical therapy for other pathologies. More granular data will be needed to further characterize the concerning associations with regard to payer status.

Overall, our findings provide a broad overview of the national trend of PT referral for the management of LBP and isolate concerning associations with regard to payer status and association with opioid prescription. Our study is limited by the lack of individual patient and diagnosis granularity in the dataset, which limits our ability to differentiate new versus repeat referrals and to distinguish among a wide range of spine disorders contributing to LBP. Further research is needed to determine why these disparities in PT referral exist. The continued low rates of physical therapy referrals for patients with LBP suggest that initiatives are needed to educate both providers and patients about the utility of physical therapy.

CONCLUSION

Although therapies delivered by PTs are promoted as a first-line treatment for LBP, PT referral rates continue to be steadily low. There also exist disparately lower referral rates in populations with more restrictive health plans and simultaneous opioid prescription. Our findings provide a broad overview to PT prescription trend and isolate concerning associations requiring further explorations.

Key Points.

In spite of national guidelines promoting physical therapy as first-line treatment for low back pain, there exist steadily low rates of physical therapy referrals in the United States for patients.

Populations with more restrictive health plans have disparately lower rates of PT referral.

Initiatives are needed to educate both providers and patients about the utility of physical therapy.

Acknowledgments

Relevant financial activities outside the submitted work: board membership, expert testimony, grants, stocks.

Footnotes

Level of Evidence: 3

The manuscript submitted does not contain information about medical device(s)/drug(s).

References

- 1.Walker BF. The prevalence of low back pain: a systematic review of the literature from 1966 to 1998. J Spinal Disord 2000;13:205–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Manchikanti L. Epidemiology of low back pain. Pain Phys 2000;3:167–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Deyo RA, Mirza SK, Turner JA, Martin BI. Overtreating chronic back pain: time to back off? J Am Board Fam Med JABFM 2009;22:62–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luo X, Pietrobon R, Sun SX, et al. Estimates and patterns of direct health care expenditures among individuals with back pain in the United States. Spine 2004;29:79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoy D, March L, Brooks P, et al. The global burden of low back pain: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:968–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freburger JK, Holmes GM, Carey TS. Physician referrals to physical therapy for the treatment of musculoskeletal conditions. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2003;84:1839–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chou R. In the clinic: low back pain. Ann Intern Med 2014;160;ITC6–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ladeira CE, Samuel Cheng M, Hill CJ. Physical therapists’ treatment choices for non-specific low back pain in Florida: an electronic survey. J Man Manip Ther 2015;23:109–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zigenfus GC, Yin J, Giang GM, Fogarty WT. Effectiveness of early physical therapy in the treatment of acute low back musculoskeletal disorders. J Occup Environ Med Am Coll Occup Environ Med 2000;42:35–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fritz JM, Childs JD, Wainner RS, Flynn TW. Primary care referral of patients with low back pain to physical therapy. Spine 2012;37:2114–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehrmann-Feldman D, Rossignol M, Abenhaim L, Gobeille D. Physician referral to physical therapy in a cohort of workers compensated for low back pain. Phys Ther 1996;76:150–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Staal JB, Hlobil H, van Tulder MW, et al. Return-to-work interventions for low back pain: a descriptive review of contents and concepts of working mechanisms. Sports Med 2002;32:251–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fritz JM, Cleland JA, Speckman M, et al. Physical therapy for acute low back pain: associations with subsequent healthcare costs. Spine 2008;33:1800–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med 2007;147:478–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bigos S, Bowyer O, Braen G, et al. Acute low back problems in adults:assessment and treatment. Clinical practice guideline number 14. AHCPR Pub 95-0643. Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mafi JN, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, Landon BE. Worsening trends in the management and treatment of back pain. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1573–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeffrey Kao M-C, Minh LC, Huang GY, et al. Trends in ambulatory physician opioid prescription in the United States, 1997–2009. PM R 2014;6:572–582.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dagenais S, Caro J, Haldeman S. A systematic review of low back pain cost of illness studies in the United States and internationally. Spine J 2008;8:8–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dagenais S, Haldeman S. Evidence-Based Management of Low Back Pain. St Louis, Missouri: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sa S. Economic burden of prescription opioid misuse and abuse. J Manag Care Pharm JMCP 2009;15:556–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martell BA, O’Connor PG, Kerns RD, et al. Systematic review: opioid treatment for chronic back pain: prevalence, efficacy, and association with addiction. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:116–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guller U, Jain N, Curtis LH, et al. Insurance status and race represent independent predictors of undergoing laparoscopic surgery for appendicitis: secondary data analysis of 145,546 patients. J Am Coll Surg 2004;199:567–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Varela JE, Nguyen NT. Disparities in access to basic laparoscopic surgery at U.S. academic medical centers. Surg Endosc 2011;25:1209–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LaPar DJ, Bhamidipati CM, Walters DM, et al. Primary payer status affects outcomes for cardiac valve operations. J Am Coll Surg 2011;212:759–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LaPar DJ, Stukenborg GJ, Guyer RA, et al. Primary payer status is associated with mortality and resource utilization for coronary artery bypass grafting. Circulation 2012;126:S132–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.LaPar DJ, Bhamidipati CM, Mery CM, et al. Primary payer status affects mortality for major surgical operations. Ann Surg 2010;252:544–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carey TS, Garrett J, Jackman A, et al. The outcomes and costs of care for acute low back pain among patients seen by primary care practitioners, chiropractors, and orthopedic surgeons. N Engl J Med 1995;333:913–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fishbain DA, Cole B, Lewis J, et al. What percentage of chronic nonmalignant pain patients exposed to chronic opioid analgesic therapy develop abuse/addiction and/or aberrant drug-related behaviors? A structured evidence-based review. Pain Med 2008;9:444–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]