Abstract

Cyclin-dependent kinase-like 5 Deficiency Disorder (CDD) is a rare neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by infantile-onset refractory epilepsy, profound developmental delays, and cerebral visual impairment (CVI). While there is evidence that the presence of CVI in CDD is common, the potential impact of CVI severity on developmental attainment has not been explored directly. Focusing on a cohort of 46 children with CDD, examination features indicative of CVI were quantified and compared to developmental achievement. The derived CVI severity score was inversely correlated with developmental attainment, bolstering the supposition that CVI severity may provide a useful early biomarker of disease severity and prognosis. This study demonstrates the utility of a CVI score to better capture the range of CVI severity in the CDD population and further elucidates the interaction between CVI and developmental outcomes.

Introduction

Cyclin-dependent kinase-like 5 Deficiency Disorder (CDD) is a rare monogenic neurodevelopmental disorder typified by early onset epilepsy and profound global developmental delays.1–4 The CDKL5 gene is highly expressed in the developing nervous system and has been demonstrated to encode for a kinase involved in a multitude of functions crucial for neurodevelopment, including neuronal division, maturation, migration, and synaptic transmission.5–9 Pathogenic changes in CDKL5 are one of the more common genetic etiologies underlying developmental epileptic encephalopathies.10 Seizures in CDD often develop in the first weeks of life and prove refractory to medical management.11–13 Developmentally, most children with CDD never achieve independent ambulation or complex speech.4,14,15 Cerebral visual impairment (CVI), a brain-based disorder of vision, has recently been recognized as an additional common feature of CDD, with evidence of suggesting that as many as 75% children with CDD suffering some degree of CVI.16,17

CVI has been repeatedly demonstrated to confer far-ranging consequences for children with a variety of neurologic disorders; it is associated with impaired developmental achievement, reduced independent mobility and diminished quality of life.18–23 In West syndrome, there is some evidence of CVI serving as a potential marker of clinical improvement.24,25 However, the clinical impact of CVI has been underexplored among children with CDD specifically—and developmental epileptic encephalopathies more generally.26 Functional limitations common among children with severe epileptic encephalopathies like CDD complicate the accurate and efficient clinical assessment of CVI. While there are several published neuropsychological visual perception tests for CVI in children, they can be technically arduous and time-consuming to administer, often require skills not always attained by children with CDD and other epileptic encephalopathies (e.g., identification of letters or shapes on an acuity chart, color matching, intact language comprehension, ability to follow complex directions, fine-motor fluidity, and/or special equipment and training).27–32 Consequently, there remains no gold-standard method for diagnosing or grading CVI among children with CDD or other epileptic encephalopathies.

Despite the general paucity of systematic studies of CVI within the CDD patient population, there is compelling evidence that quantification of CVI may provide for a useful marker for CDD disease severity and prognosis, particularly as it relates to developmental outcomes.16,33 A global provider impression of visual function found, for example, that the presence of CVI correlated with reduced achievement of developmental milestones within patients with CDD.16 Of the variables explored (i.e., seizure types, history of hypsarrhythmia, periods of seizure freedom, genetic variant classification), the presence of CVI was the only CDD feature correlated with developmental attainment; severity of CVI was not explored.

As there are currently no validated functional vision tools or CVI assessments specifically developed for use in the clinical setting with children with CDD, we sought: (1) to investigate whether a routine, clinically-focused neurologic exam could be used to quantify CVI severity; and (2)to explore whether CVI severity in CDD was predictive of developmental achievement as determined by a previously published 7-point developmental scale and a novel 16-point developmental scale. We hypothesize that CVI is a determinative clinical feature of children with CDD such that severity is negatively correlated with developmental scores.

Patients and Methods

A cross-sectional study exploring phenotypic features associated with CDD was performed on patients seen at the Children’s Hospital Colorado CDKL5 Center of Excellence between April 2014 and April 2020. The study was approved by the local IRB (CO, protocol 13-2020) with postcard opt-out patient consent. Data collection forms were developed, modified, and expanded based on investigator experience in evaluating patients with CDD in clinical care and in the NIH Rett and Rett-Related Disorders Natural History Study consortium (U54 HD061222 (Percy)) and in collaboration with the International Foundation for CDKL5 research Centers of Excellence. All data was collected in the time-frame of a routine clinical visit. Utilizing these standardized history and examination forms, data were collected on demographics, development, exam findings, age of seizure onset, and longest period of seizure freedom.

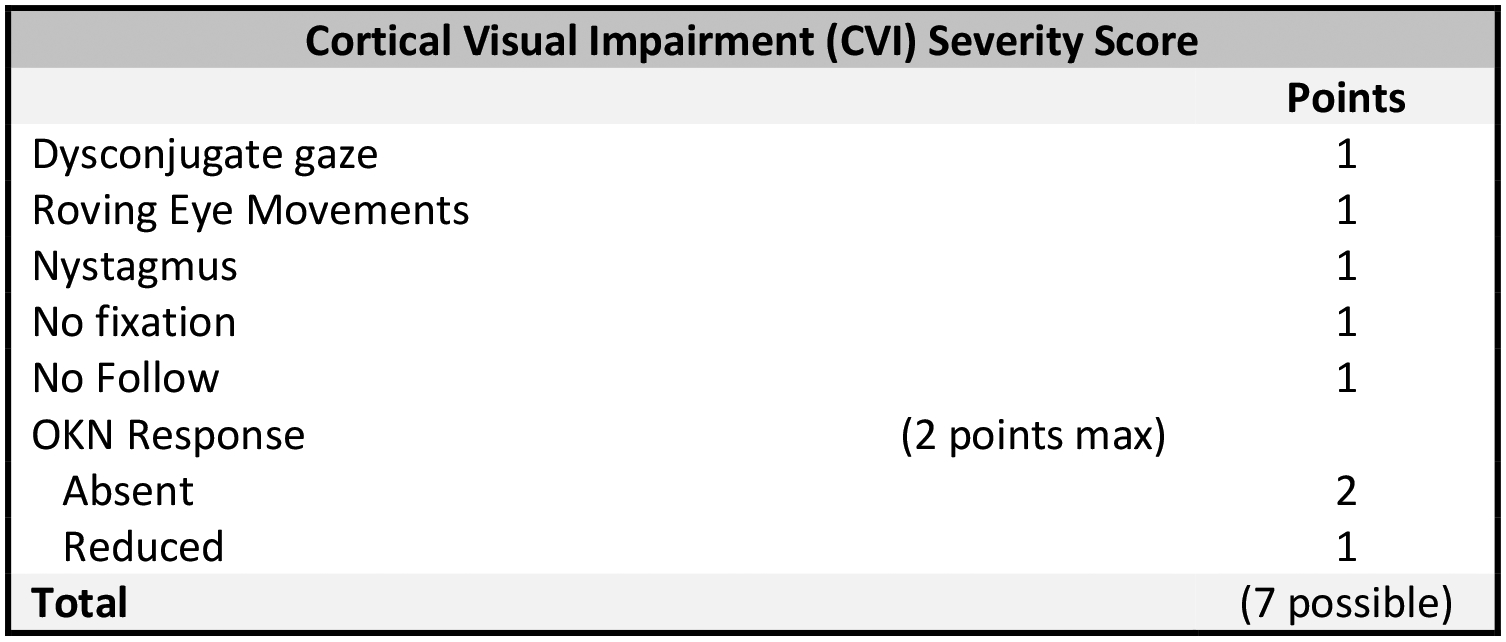

CVI severity was quantified via development of a novel CVI score adapted from the available physical exam data, including the presence of dysconjugate gaze, nystagmus, roving eye movements, abnormal optokinetic nystagmus response (reduced or absent), and impaired fixation and follow. All exams were performed by the same examiner. Optokinetic nystagmus was assessed with lights dimmed using the OptoK iPad application on an eleven-inch iPad. The resulting scale corresponds with reasonable fidelity to the variables included in the Neonatal Assessment Visual European Grid (NAVEG) scale previously shown to predict neurologic risk in patients admitted to the Neonatal ICU.34The presence of observed or known structural eye abnormalities was also assessed. The CVI severity (ranging from 0 −7) was then calculated by summing the number of abnormal exam findings (Figure 1). Developmental outcomes were scored based on a previously published 7-pointCDKL5 Developmental Score calculated by summing the number of milestones achieved: independent sitting, independent standing, independent walking, raking grasp, pincer grasp, consonant babble, and spoken language comprising single words at a minimum (Figure 2).16 An expanded 16-point developmental scale was constructed extending the original 7-point scale, adding more granularity to the gross motor, fine motor, and expressive language domains as well as a fourth domain focused on social and cognitive milestones (Figure 3). All developmental milestones evaluated would be expected to be fulfilled by a typically developing 12–15-month-old child. Both developmental scales were divided into subscales comprised of gross motor, fine motor/hand function, expressive communication milestones; a fourth subscale containing cognitive/social milestones was included for the expanded 16-point developmental scale.

Figure 1.

CVI Severity Score: List of CVI Variables and their Corresponding ‘Points.’ The Variables, when Present on Exam, are Summed According to their Value. Minimum Score Possible = 0; Maximum Points Possible = 7.

Figure 2.

7-Point Development Scale: Variables included in the 7-Point Developmental Scale, Subdivided into Three Domains (i.e., Gross Motor, Hand Function, Expressive Communication). The Variables within each Domain are Considered Ordinal, such that the Presence of more Advanced Milestones Assume Preceding Milestones if not otherwise Indicated on History. Minimum Score Possible = 0; Maximum Points Possible = 7.

Figure 3.

16-Point Development Scale: Variables Included in the Expanded 16-point Developmental Scale, Subdivided into four Domains (i.e., Gross Motor, Hand Function, Expressive Communication, Social/Cognitive). Expressive Communication was Further Divided into Verbal and Nonverbal Communication. Each Domain has a Maximum of four Possible Points. Minimum Score Possible = 0; Maximum Points Possible = 16.

A descriptive table was created for patient characteristics with categorical variables displayed as frequencies and percentages and continuous variables as medians and interquartile ranges.

Multivariable analyses were performed to assess the association between CVI and both outcomes of interest, the 7- and 16-point development scales, using general linear models. Age at most recent visit and gender were identified a priori for inclusion in models. Additional variables, age at seizure onset and period of seizure freedom, were considered as additional covariates based on bivariable analysis with the outcomes. Bivariable analysis was performed with simple linear regression. Variables with a p-value less than 0.2 in bivariable analysis were included in the multivariable model. This resulted in both of the multivariable models having four explanatory variables, each variable contributing one degree of freedom, which we determined was acceptable given a sample size of 46.

An exploratory factor analysis was conducted for the CVI and developmental scales to evaluate internal consistency/reliability. The subscales within the developmental scales were used as the individual items in the factor analysis, but the 7 items comprising the CVI score were all used in the factor analysis for the CVI scale. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated along with the correlation of each item with the total of the other items, and a common factor analysis was performed to see if individual items loaded onto the same construct.

All analyses were performed using SAS v.9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 48 patients with CDD were evaluated in the Colorado Children’s CDKL5 Center of Excellence during the study period between April 2014 and April 2020. Twenty-one patients had at least one follow-up visit, and seven patients were seen for two follow-up visits. The most recent clinic visits for a given patient was used for analysis. Two patients were excluded from final analysis due to incomplete history or examination data; forty-six patients were subsequently included for final analysis (Table 1). Forty-one (89%) patients were female. The median age at the most recent clinic visit was five years old (interquartile range: 2.0–14.0). The median age of seizure onset was five weeks old. There was a mean CVI score of 4.3 (SD = 2.0, range 0–7), with a CVI score of four or more observed in 32 patients (70%). Only three patients (6.5%) did not have any evidence of vision impairment on exam, while six patients (13%) received a maximum CVI severity score of seven (Table 2). One patient was noted on history and exam to have a structural eye abnormality, namely, a history of cataract several years post removal at the time of the most recent visit. No patients were noted to have retinal disease or optic nerve abnormalities on fundoscopic examination. There was a mean7- point developmental score of 2.4 (SD = 2.1, range 0–7) and mean 16-point score of 6.5 (SD = 3.2, range 1–14). Ten patients (22%) had a 7-point developmental scale score of zero, but no patients had a score of zero on the 16-point scale.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics and Seizure History.

| Variable | Total n=46 |

|---|---|

| Age at most recent visit (years) | 5.0 (2.0–14.0)* |

| Age at seizure onset (weeks) | 5.0 (3.0–8.0) |

| Child’s gender at birth | |

| Female | 89.1% (41) |

| Male | 10.9% (5) |

| Age at seizure onset (weeks) | |

| 0 to <5 | 45.7% (21) |

| 5 to <13 | 47.8% (22) |

| 13 and older | 6.5% (3) |

| Age at most recent visit (years) | |

| <1 | 8.7% (4) |

| 1 to <2 | 10.9% (5) |

| 2 to <5 | 26.1% (12) |

| 5 and older | 54.3% (25) |

| Period of Seizure Freedom (months) | |

| <1 | 32.6% (15) |

| 1 to <3 | 19.6% (9) |

| 3 to <6 | 15.2% (7) |

| 6 to <12 | 17.4% (8) |

| 12 or more | 15.2% (7) |

Cells are N (%) or Median (IQR)

Table 2.

CVI Severity Score Distribution: The Frequency (Total & Percentage; N=46) of Patients with each CVI Severity Score is Displayed.

| CVI Severity Score Distribution | ||

|---|---|---|

| Score | Frequency | % |

| 0 | 3 | 6.5 |

| 1 | 2 | 4.4 |

| 2 | 5 | 10.9 |

| 3 | 4 | 8.7 |

| 4 | 8 | 17.4 |

| 5 | 10 | 21.7 |

| 6 | 8 | 17.4 |

| 7 | 6 | 13.0 |

Bivariate analyses performed to assess the relationship between the individual variables of interest and developmental outcome revealed CVI severity to be the only variable investigated that significantly correlated with developmental achievement. Specifically, neither gender, earlier age of seizure onset, nor period of seizure freedom correlated significantly with developmental outcome. Age did show a small effect, but only for the expanded 16-point developmental scale; on average, the 16-point developmental score increased by 0.14 for each year increase in age at most recent visit at most recent visit (p = 0.02). CVI severity, in contrast, was found to be inversely correlated with developmental achievement as quantified by both the 7-point and 16-point developmental scales(Table 3). Bivariable analyses revealed that a one unit increase in the CVI severity corresponded to a 0.61-point decrease in the calculated 7-point developmental score (p <0.0001) and a 0.90-point decrease in the calculated 16-point development score (p < 0.0001). Adjusting for possible confounders identified in the bivariate analysis, the multivariable linear regression model (Table 3) found a statistically significant moderate negative association between CVI severity and the 7-point developmental scale and a robust negative association with the 16-point scale. Specifically, one unit increase in the CVI severity corresponded to a 0.56-point decrease in the calculated 7-point developmental score (p = 0.0002) and a 0.80-point decrease in the calculated 16-point development score (p < 0.0003). Scatterplots containing regression lines were constructed to illustrate the inverse relationship between the CVI severity scores and the two developmental scales (Figure 4).

Table 3.

Bivariate and Multiple Linear Regression Results – CVI Score, Age, and Seizure History Compared to Developmental Scores.

| Variable | 7-Point Developmental Score | 16-Point Developmental Score | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binary analysis | Multiple regression | Binary analysis | Multiple regression | |||||

| Regression* coefficient | P-value | Regression coefficient | P-value | Regression coefficient | P-value | Regression coefficient | P-value | |

| CVI Severity Score (1 unit increase) | −0.61 | <.0001 | −0.56 | 0.0002 | −0.90 | <.0001 | −0.80 | 0.0003 |

| Gender (Female vs Male) | 0.21 | 0.83 | 0.19 | 0.83 | −0.16 | 0.92 | −0.27 | 0.84 |

| Age at most recent visit (1 year increase) | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.036 | 0.30 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.10 |

| Period of seizure freedom (<3 vs >3 months) | −0.82 | 0.20 | −0.38 | 0.51 | −1.30 | 0.17 | −0.73 | 0.39 |

Age of seizure onset was not included in multivariable analysis due to failure to meet inclusion criteria based on bivariate analysis results.

Figure 4.

Scatterplot of CVI scores vs developmental scores. Adjusted R-Square and prediction line based on multiple linear regression model. A jitter option was used to see overlapping points.

An exploratory factor analysis for the 7-point development scale found that the three subscales (gross motor, fine motor, expressive communication) all loaded onto one factor, and had adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.68). Factor analysis for the four subscales for the 16-point developmental score similarly found that the subscales factored together onto one factor, with Social/Cognitive having the weakest correlation to the overall factor (Cronbach’s Alpha = 0.71). Results indicate adequate internal consistency between the subscales for both developmental scales. An exploratory factor analysis for the CVI severity scale found a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.72, which suggests satisfactory internal consistency, but further factor analysis showed that the scale was not unidimensional.

Discussion

This is the first investigation to quantitatively explore the relationship between the severity of CVI in children with CDD and their respective developmental attainment. The CVI features included in the novel CVI severity scale are compatible with well-documented examination findings of children with CVI, and largely correspond with the variables assessed by the NAVEG scale, which has been validated for use in the NICU setting.34,35 This study confirms that CVI is a common characteristic of CDD, with the vast majority of patients demonstrating multiple exam features indicative of visual impairment—and nearly 1/3 of children with abnormalities on six or more of the seven variables assessed. While skewed some toward higher scores, less than 15% of the cohort demonstrated a floor or ceiling effect, indicating reasonable sensitivity to change.36,37 Further, CVI severity demonstrated a significantly stronger relationship to developmental attainment than any other variable assessed, including age at most recent visit, age at seizure onset, duration of seizure freedom, or gender. We recognize that the present study cannot speak to a causal relationship between CVI and development, leaving open the question of whether CVI is one of myriad drivers of development or marker of overall disease severity. The absence of a clear correlation between age and developmental scores was not a priori expected, though does substantiate a clear role for early biomarkers of disease severity and prognosis in CDD. That is, as CVI can be assessed reliably in infancy—prior to most major gross and fine-motor milestones—its potential for acting as a predictive biomarker is highlighted by these results. A prospective study should be performed to assess the use of this CVI scale as a predictive biomarker of development.

The developmental scales investigated herein were intended to be clinically relevant to the CDD population. The 7-point scale was previously published in the CDD population and found to be a reasonable outcome measure; the derivative 16-point scale was intended to provide additional and clinically meaningful granularity.14,16 While the variables included in each scale would be expected to be achieved by a typically developing 15-month-old, we found that they reasonably captured the developmental spectrum seen in CDD, despite a majority of patients being 5 years of age or older at the time of assessment. As intended, the score distribution was more evenly dispersed within the expanded 16-point scale. Exploratory factor analysis of the subscales found that there was adequate internal consistency for both scales. Overall, the two developmental scores showed similar relationships to each other. This adds some additional support for the use of the 7-point developmental score as an outcome measure in CDD cohorts, though further investigation and refinement of these scales will be necessary to confirm their validity.

There were several important limitations of the present study. The novel CDD CVI Severity Score developed for use in this investigation is limited by the available examination data set. While the assessed variables do cohere well with established CVI assessments, there is an opportunity for future improvements by including additional items in prospective investigations (e.g., light-gazing, visual threat response, visual field preference, visually guided touch, preferential looking and/or color preference). Additionally, we note that many of the included CVI features captured on examination overlap with what may be seen in children with structural eye abnormalities or retinal disease. However, the existence of either is uncommon among children with CDD, evidenced by the low rates observed in this study population. Consequently, the use of the available examination findings is reasonably considered to reflect visual dysfunction of cerebral origin.

Conclusion

As CVI can be assessed in infancy, there is compelling reason to believe that early identification may provide for earlier prognostication and possibly intervention by adopting of more therapies that accommodate and incorporate CVI (i.e., low-vision therapy, vision re/habilitation therapy and the use of CVI friendly methods for other therapies) during critical periods of development.31 The principal aim is to ensure robust interaction of the child with their environment, and in turn to optimize their function and ability to participate in daily life.27 The absence of clinically appropriate, valid and reliable CVI assessments for CDD therefore hinders inclusive functional appraisal, clinical guidance, and the timely adoption of valuable interventions critical to the furtherment of developmental potential in this population. This study provides proof of concept that in children with CDD that a brief, focused neurologic exam can be used to assess for and quantify CVI—and affirms CVI as a common and important feature of CDD. CVI severity is further substantiated as a potential clinical marker of disease severity and developmental prognosis within this cohort—and raises the additional possibility that it may translate straightforwardly to use in other severe developmental and epileptic encephalopathies associated with CVI.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the International Foundation for CDKL5 Research (IFCR).

Disclosures /Declaration of Conflicting Interests

Scott Demarest: funding from IFCR; consultancy for Upsher-Smith, Biomarin and Neurogene, Marinus and Ovid Therapeutics; all remuneration has been made to his department. Dylan Brock: funding from IFCR; all remuneration has been made to his department.Tim A. Benke: funding from the NIH, International Foundation for CDKL5 Research, and Children’s Hospital Colorado Foundation; consultancy for AveXis, Ovid, GW Pharmaceuticals, International Rett Syndrome Foundation, Takeda, and Marinus; Clinical Trials with Acadia, Ovid, GW Pharmaceuticals, Marinus and RSRT; all remuneration has been made to his department. The other authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose. The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the International Foundation for CDKL5 Research (Brock, Benke, Demarest), the NIH-NINDS (U54 HD061222 (Percy)) Natural History Study of Rett and Rett-related disorders (Benke,) and Children’s Hospital Colorado Foundation Ponzio Family Chair in Neurology Research (Benke).

Footnotes

Ethical Approval /Patient Consent

The study was approved by the local IRB (CO, protocol 13-2020) with postcard opt-out patient consent. All patients were seen at the Children’s Hospital Colorado CDKL5 Center of Excellence between April 2014 and April 2020.

References:

- 1.Weaving LS, Christodoulou J, Williamson SL, et al. Mutations of CDKL5 cause a severe neurodevelopmental disorder with infantile spasms and mental retardation. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75(6):1079–1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bahi-Buisson N, Bienvenu T. CDKL5-Related Disorders: From Clinical Description to Molecular Genetics. Mol Syndromol. 2012;2(3–5):137–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bahi-Buisson N, Villeneuve N, Caietta E, et al. Recurrent mutations in the CDKL5 gene: genotype-phenotype relationships. Am J Med Genet A. 2012;158A(7):1612–1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moseley BD, Dhamija R, Wirrell EC, Nickels KC. Historic, clinical, and prognostic features of epileptic encephalopathies caused by CDKL5 mutations. Pediatr Neurol. 2012;46(2):101–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuchs C, Trazzi S, Torricella R, et al. Loss of CDKL5 impairs survival and dendritic growth of newborn neurons by altering AKT/GSK-3beta signaling. Neurobiol Dis. 2014;70:53–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Q, Zhu YC, Yu J, et al. CDKL5, a protein associated with rett syndrome, regulates neuronal morphogenesis via Rac1 signaling. J Neurosci. 2010;30(38):12777–12786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin C, Franco B, Rosner MR. CDKL5/Stk9 kinase inactivation is associated with neuronal developmental disorders. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14(24):3775–3786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Okuda K, Kobayashi S, Fukaya M, et al. CDKL5 controls postsynaptic localization of GluN2B-containing NMDA receptors in the hippocampus and regulates seizure susceptibility. Neurobiol Dis. 2017;106:158–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paine SM, Munot P, Carmichael J, et al. The neuropathological consequences of CDKL5 mutation. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2012;38(7):744–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindy AS, Stosser MB, Butler E, et al. Diagnostic outcomes for genetic testing of 70 genes in 8565 patients with epilepsy and neurodevelopmental disorders. Epilepsia. 2018;59(5):1062–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Archer HL, Evans J, Edwards S, et al. CDKL5 mutations cause infantile spasms, early onset seizures, and severe mental retardation in female patients. J Med Genet. 2006;43(9):729–734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fehr S, Wilson M, Downs J, et al. The CDKL5 disorder is an independent clinical entity associated with early-onset encephalopathy. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013;21(3):266–273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao Y, Zhang X, Bao X, et al. Clinical features and gene mutational spectrum of CDKL5-related diseases in a cohort of Chinese patients. BMC Med Genet. 2014;15:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fehr S, Downs J, Ho G, et al. Functional abilities in children and adults with the CDKL5 disorder. Am J Med Genet A. 2016;170(11):2860–2869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takeda K, Miyamoto Y, Yamamoto H, Ishii A, Hirose S, Yamamoto H. Clinical features of early myoclonic encephalopathy caused by a CDKL5 mutation. Brain Dev. 2020;42(1):73–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Demarest ST, Olson HE, Moss A, et al. CDKL5 deficiency disorder: Relationship between genotype, epilepsy, cortical visual impairment, and development. Epilepsia. 2019;60(8):1733–1742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demarest S, Pestana-Knight EM, Olson HE, et al. Severity Assessment in CDKL5 Deficiency Disorder. Pediatr Neurol. 2019;97:38–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sonksen PM, Dale N. Visual impairment in infancy: impact on neurodevelopmental and neurobiological processes. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2002;44(11):782–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boot FH, Pel JJ, van der Steen J, Evenhuis HM. Cerebral Visual Impairment: which perceptive visual dysfunctions can be expected in children with brain damage? A systematic review. Res Dev Disabil. 2010;31(6):1149–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fazzi E, Bova SM, Uggetti C, et al. Visual-perceptual impairment in children with periventricular leukomalacia. Brain Dev. 2004;26(8):506–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chadha RK, Subramanian A. The effect of visual impairment on quality of life of children aged 3–16 years. Br J Ophthalmol. 2011;95(5):642–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsuba CA, Jan JE. Long-term outcome of children with cortical visual impairment. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2006;48(6):508–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dale N, Sonksen P. Developmental outcome, including setback, in young children with severe visual impairment. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2002;44(9):613–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guzzetta F, Frisone MF, Ricci D, Rando T, Guzzetta A. Development of visual attention in West syndrome. Epilepsia. 2002;43(7):757–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rando T, Bancale A, Baranello G, et al. Visual function in infants with West syndrome: correlation with EEG patterns. Epilepsia. 2004;45(7):781–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scheffer IE, Berkovic S, Capovilla G, et al. ILAE classification of the epilepsies: Position paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia. 2017;58(4):512–521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang MY, Borchert MS. Advances in the evaluation and management of cortical/cerebral visual impairment in children. Surv Ophthalmol. 2020;65(6):708–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Good WV. Development of a quantitative method to measure vision in children with chronic cortical visual impairment. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2001;99:253–269. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Genderen M, Dekker M, Pilon F, Bals I. Diagnosing cerebral visual impairment in children with good visual acuity. Strabismus. 2012;20(2):78–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lehman SS. Cortical visual impairment in children: identification, evaluation and diagnosis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2012;23(5):384–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roman-Lantzy C Cortical visual impairment: an approach to assessment and intervention. New York: AFB Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roman-Lantzy C Cortical visual impairment: advanced principles. Louisville, KY: APH Press, American Printing House for the Blind; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mazziotti R, Lupori L, Sagona G, et al. Searching for biomarkers of CDKL5 disorder: early-onset visual impairment in CDKL5 mutant mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26(12):2290–2298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rossi A, Gnesi M, Montomoli C, et al. Neonatal Assessment Visual European Grid (NAVEG): Unveiling neurological risk. Infant Behav Dev. 2017;49:21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Good WV, Jan JE, DeSa L, Barkovich AJ, Groenveld M, Hoyt CS. Cortical visual impairment in children. Surv Ophthalmol. 1994;38(4):351–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gulledge CM, Lizzio VA, Smith DG, Guo E, Makhni EC. What Are the Floor and Ceiling Effects of Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Computer Adaptive Test Domains in Orthopaedic Patients? A Systematic Review. Arthroscopy. 2020;36(3):901–912 e907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kemp JL, Collins NJ, Roos EM, Crossley KM. Psychometric properties of patient-reported outcome measures for hip arthroscopic surgery. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(9):2065–2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]