Abstract

Significant changes occur in intestinal epithelial cells after infection with enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC). However, it is unclear whether this pathogen alters rates of apoptosis. By using a naturally occurring weaned rabbit infection model, we determined physiological levels of apoptosis in rabbit ileum and ileal Peyer's patches (PP) and compared them to those found after infection with adherent rabbit EPEC (REPEC O103). Various REPEC O103 strains were first tested in vitro for characteristic virulence features. Rabbits were then inoculated with the REPEC O103 strains that infected cultured cells the most efficiently. After experimental infection, intestinal samples were examined by light and electron microscopy. Simultaneously, ileal apoptosis was assessed by using terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) and caspase 3 assays and by apoptotic cell counts based on morphology (hematoxylin-and-eosin staining). The highest physiological apoptotic indices were measured in PP germinal centers (median = 14.7%), followed by PP domed villi (8.1%), tips of absorptive villi (3.8%), and ileal crypt regions (0.5%). Severe infection with REPEC O103 resulted in a significant decrease in apoptosis in PP germinal centers (determined by TUNEL assay; P = 0.01), in the tips of ileal absorptive villi (determined by H&E staining; P = 0.04), and in whole ileal cell lysates (determined by caspase 3 assay; P = 0.001). We concluded that REPEC O103 does not promote apoptosis. Furthermore, we cannot rule out the possibility that REPEC O103, in fact, decreases apoptotic levels in the rabbit ileum.

Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) is the leading cause of bacterium-mediated infantile diarrhea, killing several hundred thousand children every year (19, 30). Natural animal disease models such as rabbits infected with rabbit EPEC serogroup O103 (REPEC O103) have been used to study pathogenesis. Apart from its chromosome-encoded adhesive factor (AF/R2) that triggers initial diffuse adherence to intestinal epithelial cells, REPEC O103 possesses the same virulence factors and mechanisms as human EPEC. It secretes several effector proteins via a type III secretion system (EspA, EspB, EspD, and Tir), it produces the outer membrane protein intimin, and it is a Shiga toxin-negative strain (1, 28, 32). Binding between intimin and its translocated receptor, Tir, results in the formation of attaching-and-effacing lesions characterized by intimate attachment between the bacterium and the host epithelial cell with effacement of microvilli resulting with the pathogen residing upon actin-rich pedestals (9, 21). Despite significant research, the pathogenic mechanisms by which EPEC causes diarrheal disease remain undefined. Specific host responses could include apoptotic changes in macrophages and/or intestinal epithelial cells, as have been reported for a variety of pathogens in vitro. However, to date, neither histopathologic reports nor in vivo investigations have described changes in apoptotic activities due to EPEC infection (10, 38).

Invasive and/or toxin-producing enteropathogens such as Salmonella, Shigella, and Yersinia species, enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC), and Helicobacter pylori increase apoptosis in macrophages and/or epithelial cells in vivo (18, 20, 23, 27, 29, 34, 42, 45, 46). Similarly, Listeria and enteroinvasive E. coli increase apoptosis in vitro (22, 45). Cell lines such as T84 and HeLa cells infected with EPEC also show features of apoptosis (6). However, the cell permeability to vital dyes such as trypan blue and propidium iodide that was observed is not a definitive feature of apoptosis (late apoptotic cells are propidium iodide positive), and dye-positive cells were not consistently seen beneath adherent bacteria. In addition, infected cells rarely showed distinct morphologic characteristics of apoptosis, including DNA breakdown, and the increase in apoptotic signals was, in general, much weaker than that caused by invasive or toxin-producing pathogens. Other investigators found that EPEC, REPEC serogroup O15 (RDEC-1), and Citrobacter rodentium directly inhibit the production of interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-4, and gamma interferon, suggesting that these pathogens do not increase apoptosis (26). In addition, researchers have speculated that EPEC adherence potentially stimulates some antiapoptotic pathways within the host cell due to activation of protein kinase C, tyrosine kinases, and the nuclear transcription factor NF-κB, leading to the expression of IL-8 (7, 36, 39).

Based on these conflicting reports, we set out to determine the influence of EPEC infection on apoptotic intestinal activities in vivo by using the naturally infected, weaned rabbit model. Several REPEC O103 strains isolated in different countries were first tested in vitro for Esp and Tir protein secretion, plasmid profile, and adherence. Animals were then inoculated with strains expressing characteristic representative virulence traits. We evaluated the incidence of apoptosis in sections from the ileum and ileal Peyer's patches (PP), sites that REPEC colonizes (14). The methods used included terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) and caspase 3 assays and counting of apoptotic cells based on their characteristic morphology in sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). We found that apoptotic activities in the rabbit ileum and ileal PP were significantly decreased when REPEC O103 disease was fully established.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

Various REPEC O103 strains isolated from weaned rabbits with heavy diarrhea were kindly provided by Jorge Blanco (Laboratorio de Referencia de E. coli, Lugo, Spain), Johan E. Peeters (National Institute of Veterinary Research, Brussels, Belgium), and Michael Davis (Gastro-Enteric Disease Laboratory, University Park, Pa.). Detailed strain characteristics are listed in Table 1. Bacterial strains were grown in Luria-Bertani broth at 37°C overnight without shaking prior to infection. To evaluate antibiotic resistance, strains were tested on Luria-Bertani broth plates containing 12 different antibiotics. To select the most appropriate REPEC O103 strains for rabbit infection, strains were screened for characteristic features, including the profile of type III secreted effector proteins, plasmid profile, HeLa cell adherence characteristics, and Shiga toxin production (1, 25, 32, 37).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Strain | Characteristic(s) | Location (yr) of isolation | Reference or source | Antibiotic resistanceb | Shiga toxin production |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B6/RD10a | REPEC O103, biotype B6a | Spain | 3 | Sp | − |

| B6/RD21a | REPEC O103, biotype B6 | Spain | 3 | Sp, St, Te | − |

| B14/RD41a | REPEC O103, biotype B14 | Spain | 3 | K, Ne, Sp, St, Te, Tr | − |

| B14/RD55a | REPEC O103, biotype B14 | Spain | 3 | C, Sp, St | − |

| B14/RDZ12 | REPEC O103, biotype B14 | Spain | 3 | Sp, St, Te | − |

| B20/RD32a | REPEC O103, biotype B20 | Spain | 3 | V | − |

| ECRC 01 | E. coli standard, serotype O1 | − | |||

| ECRC O103 | REPEC O103 | United States (1986–1987) | − | ||

| ECRC 88-0990/103-2 | REPEC O103 | Hungary (1988) | − | ||

| 85/150 | REPEC O103:K-:H2 | Belgium | 31 | C, St, Te, Tr | − |

| 84/110 | REPEC O103:K-:H2 | Belgium | 31 | C, Sp, St, Te, Tr | − |

| 85/150Nal+ | Derivative of 85/150 | 1 | Na | − | |

| EPEC 2348/69 | EPEC wild type, serotype O127:K63:H6 | Taunton, United Kingdom | 25 | St | − |

| cfm 14-2-1 | EPEC 2348/69, type III secretion-defective mutant | 8 | K, Ne, St | − | |

| EHEC 86-24 | Human EHEC, serotype O157:H7, Shiga toxin II positive | Walla-Walla, Wash. | 13 | + | |

| EHEC 87-23 | EHEC O157:H7, toxin-negative mutant | Phillip Tarr | − |

Biotypes according to the simplified biotyping scheme of Camguilhem and Milon (4).

Sp, spectinomycin; St, streptomycin; Te, tetracycline; K, kanamycin; Ne, neomycin; Tr, trimetoprim; C, chloramphenicol; V, vancomycin; Na, nalidixic acid.

Profile of type III secreted effector proteins.

Bacterial overnight cultures were diluted 1:100 in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium and incubated for 6 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. After removal of bacteria by centrifugation, the supernatant was precipitated with 10% ice-cold trichloroacetic acid and kept on ice for 1 h. After centrifugation, the pellets were resuspended in Laemmli sample buffer and analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate–12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (24). Production of Tir and EspA to -D was then characterized.

Plasmid profile.

Bacterial overnight cultures were centrifuged, and the pellet was resuspended in TAE (40 mM Tris-acetate, 2 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) and lysis solution (3% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 50 mM Tris-base, 2 N NaOH) and kept at 55°C for 30 min. After repeated phenol extraction and ethanol precipitation, pellets were analyzed on a 1% agarose gel.

Adherence and immunofluorescence on HeLa cells.

HeLa cells (104) were inoculated on coverslips and grown overnight in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium containing 10% (vol/vol) fetal calf serum at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. At 70% confluent growth, cells were infected for 5 h with bacterial overnight cultures of REPEC O103 strains and for 3 h with wild-type EPEC and the EPEC cfm mutant strain. Cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then fixed with 2.5% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4) for 10 min at 37°C. After five wash in PBS, cells were permeabilized with 0.2% saponin in PBS in the presence of antiphosphotyrosine antibodies, clone 4G10 (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, N.Y.). Alexa 594-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulins G and M (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.) were used as secondary antibodies to visualize tyrosine-phosphorylated proteins beneath adherent bacteria. To stain filamentous actin, cells were incubated with Alexa 488-conjugated phalloidin (Molecular Probes). Adherence of REPEC O103 strains and immunostaining of the samples were visualized and analyzed by using a Zeiss Axioskop microscope.

Shiga toxin.

A Shiga-toxin-producing E. coli strain, serotype O103:H2, was isolated from a 6-year-old girl with hemolytic-uremic syndrome after a urinary tract infection (40). To confirm the absence of Shiga toxin in REPEC O103 strains with the same serotype, bacteria were tested by using the Premier EHEC test kit (Meridian Diagnostics, Inc., Cincinnati, Ohio) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. In addition to the positive and negative controls provided with the test kit, EHEC strains 86-24 and 87-23 (kindly provided by Phillip Tarr) were used as positive and negative controls, respectively.

Rabbit infection and experimental design.

Weaned New Zealand White rabbits (female, 532 to 890 g, 28 to 33 days old) were obtained from Joe Bet Rabbits Limited (Abbottsford, British Columbia, Canada). Before infection, fecal suspensions were spread on MacConkey plates to ensure the absence of REPEC O103. All rabbit stools were confirmed to be free of the pathogen by slide agglutination with O103 antiserum (Gastro-Enteric Disease Laboratory). In addition, fecal suspensions were spread on MacConkey plates to screen for the presence of indigenous members of the family Enterobacteriaceae. Enterobacteriaceae were tested for antibiotic resistances, and rabbits were infected with REPEC O103 strains with different antibiotic resistances. For infection, rabbits were anesthetized and inoculated via an orogastric tube with 2 ml of overnight cultures (108 bacteria per rabbit) of REPEC O103 strains B6/RD10a (n = 6), B14/RD55a (n = 4), B20/RD32a (n = 3), and 85/150Nal+ (n = 3). Control rabbits (n = 3) received only PBS. Animals were watered and fed ad libitum before and after infection. Weight gain, symptoms of diarrhea, and fecal bacterial shedding of the inoculated strains were monitored daily. For specific identification of the test strains, fecal suspensions were spread on MacConkey plates containing specific antibiotics. Animals were sacrificed when diarrhea occurred or up to 14 days after infection. Tissue samples from the ileum and ileal PP were excised immediately after sacrifice by intravenous injection of ketamine and an overdose of sodium pentobarbital in accordance with the guidelines of the Canadian Council of Animal Care and the University of British Columbia. Samples were washed three times in PBS before further processing for histological and immunohistochemical, scanning electron microscopic (SEM), and enzymatic studies.

Tissue preparation for light microscopy, including H&E and TUNEL staining.

Tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and processed for paraffin embedding. Serial 4-μm-thick sections were cut onto glass slides and stained with H&E and Gram stain. To screen for and ensure the absence of segmented filamentous bacteria that are known to inhibit REPEC O103 infections, sections were stained with carbonin-thionin (15). Apoptosis-related DNA fragmentation was determined by the TUNEL assay using the ApopTag Peroxidase In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit (Intergen Company). Slides were first incubated overnight at 60°C to increase the adherence of sections. Samples were then processed by following the manufacturer's instructions. For color development, 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) was applied to the tissue sections. Specimens were counterstained with carmalum for morphologic definition, dehydrated in a series of ethanols and xylene, and mounted under a glass coverslip. Specimens were examined and photographed with an Olympus AH-2 light microscope. Pictures were captured with the Metaview imaging software. On TUNEL- or H&E-stained sections, apoptotic cells were enumerated by counting 100 cells in randomly selected fields of a total of 10 (i) tips of ileal absorptive villi, (ii) ileal crypts, (iii) tips of absorptive villi of PP, (iv) domed villi of PP, and (v) germinal centers of PP. Counting was done blindly. In all, 1,000 cells were enumerated at each intestinal site and the apoptotic index was expressed as the percentage of apoptotic cells per 100 cells enumerated.

Tissue preparation for SEM.

Tissues were prefixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde, rinsed in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, and postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide. After dehydration in a series of graded ethanols, specimens were critical point dried, coated with gold, and examined with a Leica 250 MK III scanning electron microscope.

Tissue preparation for the caspase 3 assay.

Tissues were kept in liquid nitrogen until processing. Caspases (cysteinyl aspartate-specific proteinases) are believed to be among the primary effector molecules of apoptosis. Once activated, caspases are responsible for cleaving various proteins, thereby disabling important cellular structural, functional, and repair processes. In the present experiments, caspase 3/7-like proteolytic activities were assessed in rabbit ileum and ileal PP. To evaluate caspase 3 activity, cell lysates were prepared by homogenization of tissue in cold cell lysis buffer (20 mM Tris [pH 8], 137 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% NP-40, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, aprotinin at 10 μg/ml). Assays were performed with 96-well microtiter plates by incubating 25 μl of cell lysate in 125 μl of reaction buffer (1% NP-40, 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 137 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol) containing the caspase 3 substrate acetyl-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp-amino-4-methylcoumarin (Ac-DEVD-AMC; Calbiochem, Cambridge, Mass.) at 100 μM. Lysates were incubated at 37°C for 2 h, and fluorescence levels were determined with a CytoFluor2350 (PerSeptive Biosystems, Burlington, Ontario, Canada) set at excitation and emission wavelengths of 380 and 460 nm, respectively.

Statistical analysis.

To compare apoptotic activities between controls (group 0) and diseased rabbits (groups 1 to 3), the unpaired Student t test was applied. The test was repeated by the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test where Gaussian distribution was not assumed. Values represent the median along with the minimum and maximum values. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Profile of proteins secreted by REPEC O103 strains.

We have previously shown that REPEC O103 strain 85/150Nal+ secretes EspA, EspB, and EspD into its culture medium (1). Likewise, strains B6/RD10a, B6/RD21a, B14/RD55a, B20/RD32a, ECRC 88-0990, 85/150, and 85/150Nal+ secreted EspA, EspB, EspD, and Tir into their culture media (data not shown). In the remaining strains, these proteins were difficult to detect by Coomassie blue staining after polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Since it is likely that the reduced amount or absence of these secreted proteins could decrease virulence, we did not use these strains for rabbit infections.

Plasmid profile of REPEC O103 strains.

It has been shown that the initial adherence of REPEC O103 is due to a chromosomally encoded adhesin, AF/R2 (adhesive factor/rabbit 2) (28, 33). The initial adherence of EPEC and another REPEC strain (RDEC-1), however, is mediated by the plasmid-encoded bundle-forming pilus and AF/R1 (adherence factor/rabbit 1), respectively (5, 11). We found that, except for ECRC O1 and ECRC O103, all strains harbor two to five plasmids of various sizes (data not shown). The plasmid profiles of Spanish strains B6/RD10a, B14/RD55a, and B20/RD32a and Belgian strain 85/150Nal+, which were used for the in vivo infection study, were only partially identical. While rabbits infected with the Spanish strains experienced heavy diarrhea (see below), rabbits infected with the Belgian strain showed only moderate disease symptoms. As the profiles of the Spanish strains also differed in size, our observations indicate that there is no specific conserved plasmid that is required for REPEC O103 virulence.

Adherence to HeLa cells and pedestal formation.

We have previously shown that bacterial adherence, actin accumulation, and tyrosine-phosphorylation of host cell proteins in vitro are essential for REPEC O103 virulence in vivo (1). As shown in Table 2, the REPEC O103 strains tested in this study adhered to HeLa cells (except for ECRC O103) in low (+), moderate (++), high (+++), or very high (++++) numbers in a diffuse way, whereas EPEC strains formed microcolonies showing localized adherence. In most cases, cytoskeletal actin accumulated beneath attached bacteria, resulting in pedestal formation. Additionally, host cell proteins were tyrosine phosphorylated at attachment sites, resulting in distinct horseshoe-shaped structures.

TABLE 2.

Features of HeLa cells after infection with various E. coli strainsa

| Strain | Bacterial adherence | Actin accumulation | Tyrosine phosphorylation |

|---|---|---|---|

| B6/RD10a | DA, ++ | +++ | +++ |

| B6/RD21a | DA, + | + | ++ |

| B14/RD41a | DA, ++ | ++ | ++ |

| B14/RD55a | DA, ++++ | +++ | ++++ |

| B14/RDZ12 | DA, ++ | − | − |

| B20/RD32a | DA, ++ | ++ | +++ |

| ECRC O1 | − | − | − |

| ECRC O103 | − | − | − |

| ECRC 88-0990/103-2 | DA, ++ | (+) | + |

| 85/150 | DA, +++ | +++ | +++ |

| 84/110 | DA, + | + | + |

| 85/150Nal+ | DA, +++ | +++ | +++ |

| EPEC 2348/69 | LA, ++++ | +++ | ++++ |

| cfm 14-2-1 | LA, +++ | − | − |

DA, diffuse adherence; LA, localized adherence. Scale: −, none; (+), very low; +, low; ++, moderate; +++, high; ++++, very high.

Shiga toxin is not present in REPEC O103 strains.

As expected, all of the REPEC O103 strains tested in the present study did not produce detectable toxins (Table 1). In contrast, control strain EHEC 86-24, secreting Shiga toxin II, showed a positive result.

Virulence of REPEC O103 strains in rabbits.

Based on the in vitro characteristics described above, Spanish REPEC O103 strains B6/RD10a, B14/RD55a, and B20/RD32a and Belgian strain 85/150Nal+ were chosen for further infection studies. Rabbits inoculated with strains B6/RD10a (n = 6), B14/RD55a (n = 4), and B20/RD32a (n = 3) showed weight loss and experienced moderate to heavy diarrhea (4 of 6, 1 of 4, and 2 of 3, respectively), which began between 2 and 7 days after infection. Fecal concentrations of the pathogen reached 4 × 1011 CFU/g of stool. Rabbits infected with the Belgian strain (n = 3) experienced weight loss (2 of 3). Stools were soft and harbored up to 5 × 109 CFU/g. When indigenous Enterobacteriaceae were detected in rabbit stools before experimental infection (5 of 16), lack of weight gain was insignificant and no change in stool consistency was observed. These findings support the hypothesis that indigenous bacteria may inhibit bacterial infections in a competitive way (2, 35).

Light and SEM observations of REPEC O103-infected ileum and ileal PP.

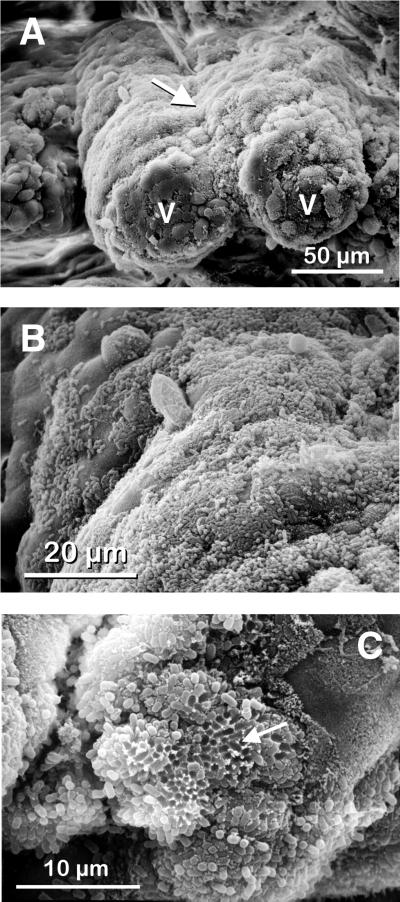

Consistent with previous reports, intestinal epithelial changes were prominent (1, 14). SEM observations (Fig. 1) illustrate that villi were blunted, stunted, and fused together (Fig. 1A; see also Fig. 2G and H). Bacteria intimately attached to ileal absorptive villi, heavily covering wide parts of their surfaces in a diffuse pattern (Fig. 1B; see also Fig. 2G). After bacterial detachment, honeycomb-like structures were visible (Fig. 1C). Compared to uninfected tissue (Fig. 2A and B), crypt regions from infected rabbits were enlarged and goblet cells were increased in number (Fig. 3A). Luminal mucus covered wide parts of the ileum, and macrophages were found assembled above the epithelium. H&E staining showed distinct immigration of polymorphonuclear leukocytes, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and sometimes erythrocytes into the mucosal epithelium of absorptive villi, reflecting increased tissue inflammation (Fig. 2H). The height and width of PP domed villi were diminished during the later stages of infection, when disease symptoms were severe. In contrast, absorptive villi decreased in height but grew in width due to the influx of inflammatory cells. Segmented filamentous bacteria (15) were not detected in any of the rabbit tissues by either SEM or carbonin-thionin staining.

FIG. 1.

Scanning electron micrographs of rabbit ileum after infection with REPEC O103. (A) Intestinal villi (v) are blunted, stunted, and fused together (arrow). (B) Bacteria heavily cover the intestinal surfaces in a diffuse pattern. (C) After bacterial detachment, honeycomb-like structures are visible (arrow).

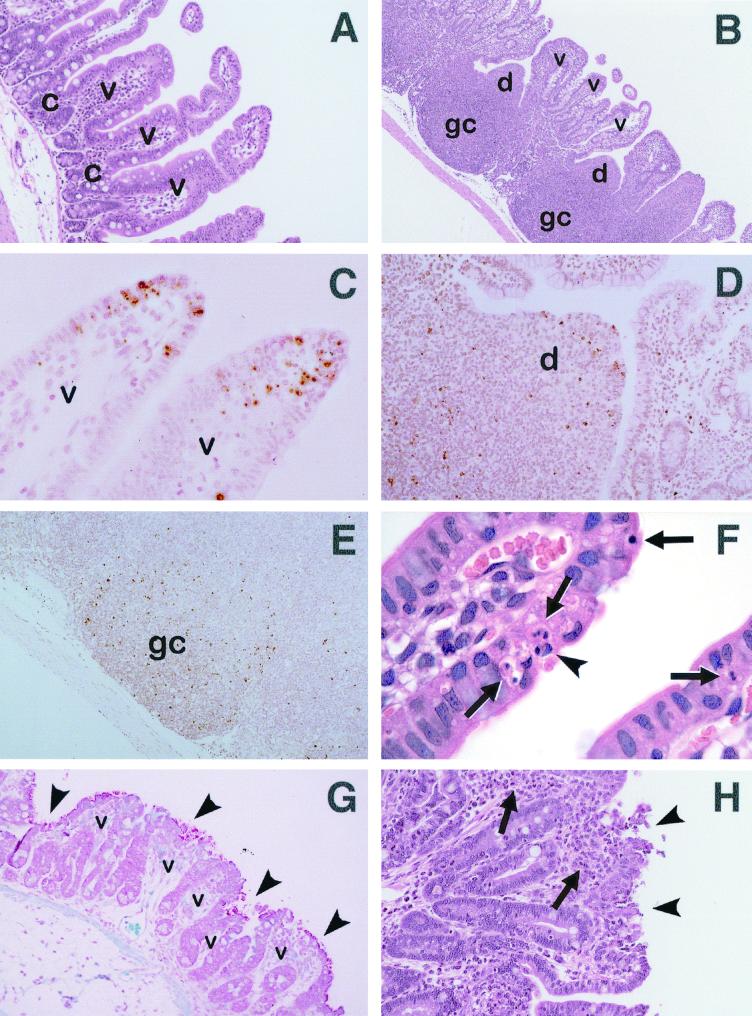

FIG. 2.

Light micrographs of rabbit ileum (A, C, F, G, and H) and ileal PP (B, D, and E), uninfected (A to F) or after severe infection with REPEC O103 (G and H) after H&E (A, B, F, and H), TUNEL (C to E), or Gram (G) staining. (A) Ileal absorptive villi (v) display their physiological long shape, while ileal crypt regions (c) are short (magnification, ×400). (B) Germinal centers (gc) and domed villi (d) of ileal PP are separated by absorptive villi (v) (magnification, ×160). (C) At the tips of ileal villi (v), numerous apoptotic cells can be distinguished from adjacent cells by their distinctive dark brown stain, forming an apoptotic cuff (magnification, ×800). (D) A number of dark-brown-stained apoptotic cells are evenly distributed in a PP domed villus (d) (magnification, ×500). (E) Numerous apoptotic cells scattered in a PP germinal center (gc) are recognizable as tiny dark-brown-stained spots (magnification, ×330). (F) A cell in the early stages of apoptosis is indicated (arrowhead). Note the two masses of chromatin which have condensed to form sharply circumscribed masses that abut the nuclear membrane. Several apoptotic bodies containing small rounded pieces of chromatin are also shown (arrows) (magnification, ×1,000). (G) Bacteria attached to ileal absorptive villi (v), heavily covering most parts of their surfaces (arrowheads). Villi are stunted, blunted, and fused together (magnification, ×500). (H) Ileal villi are fused together. They gained in width due to the influx of inflammatory cells (arrows). At villus tips, the cell layer is disrupted and cells are being shed into the lumen (arrowheads) (magnification, ×660).

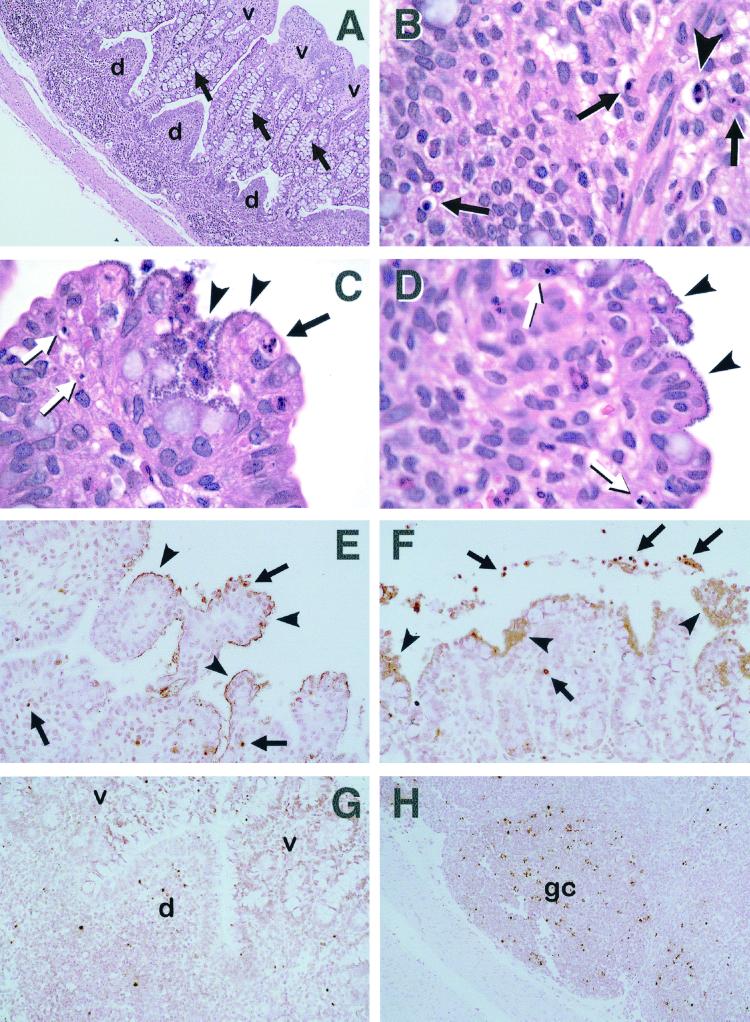

FIG. 3.

Light micrographs of rabbit ileal PP (A, B, G, and H) and ileum (C, D, E, and F) after severe infection with REPEC O103. Sections were stained with H&E (A to D) or TUNEL (E to H). (A) Domed villi (d) have dwindled. Absorptive villi (v) are thickened and fused together. Note the prominent increase in the amount of goblet cells (arrows), resulting in distinct enlargement of the crypt region (magnification, ×132). (B) Early apoptosis cell (arrowhead) showing two masses of condensed chromatin abutting the nuclear membrane. Later, this cell will bud to form apoptotic bodies. Several apoptotic bodies containing uniformly dense masses of chromatin (arrows) are also indicated (magnification, ×1,000). (C) Bacteria diffusely cover the tip of an ileal villus (arrowheads). An apoptotic cell contains several small masses of condensed chromatin (apoptotic bodies, black arrow). Two other cells in the later stages of apoptosis both contain two small, uniformly dense masses of chromatin (white arrows) (magnification, ×1,000). (D) Bacteria diffusely cover the tip region of an ileal villus (arrowheads). Two cells in the late stages of apoptosis are indicated (arrows). Note the single rounded mass of nuclear chromatin (magnification, ×1,000). (E) Masses of dark-brown-stained bacteria line the surfaces of ileal villi (arrowheads) that are mainly fused. Occasionally, apoptotic cells with condensed chromatin (arrows) can still be seen. However, note the lack of apoptotic cells beneath adherent bacteria, in contrast to the apoptotic cuff observed in uninfected tissue (magnification, ×660). (F) Masses of dark-brown-stained bacteria are diffusely attached to the ileal surface (arrowheads). Apoptotic cells cannot be seen beneath attachment sites. Instead, they can occasionally be found in the deeper tissue or shed into the lumen (arrows) (magnification, ×660). (G) A domed villus (d) diminished in size and flanked by absorptive villi (v) that are fused. Note that the incidence of dark-brown-stained apoptotic cells is greatly decreased in the domed villus (magnification, ×500). (H) Apoptotic cells can still be seen in PP germinal centers (gc). However, cell counts reveal that the apoptotic incidence has dropped compared to that in uninfected tissue (magnification, ×400).

Apoptosis—a physiological feature of the rabbit ileum.

Tissue samples from uninfected control rabbits (n = 3) and from rabbits that did not show disease symptoms despite experimental infection (n = 5) were examined for the presence of apoptotic cells in the ileum and ileal PP after TUNEL or H&E staining and by the caspase 3 assay. Cells with dark brown nuclei were considered TUNEL positive (Fig. 2C to E). For H&E counts, cells were identified as apoptotic on the basis of their morphology by using previously defined characteristics. Thus, total apoptotic cell counts included cells showing the early apoptotic changes (cytoplasmic condensation and perinuclear margination of aggregated chromatin) (Fig. 2F and 3B) through to the later stages of membrane-bound cell fragments containing uniformly dense masses of nuclear chromatin (apoptotic bodies) (Fig. 2F and 3B to D).

Depending on the intestinal site, tissue samples from all of the rabbits studied had similar amounts of apoptotic cells (Table 3, group 0). Apoptotic indices were high in PP germinal centers (median, up to 14.7%), moderate in PP domed villi and tips of ileal and PP absorptive villi (8.1, 3.8, and 3.8%, respectively), and low in ileal crypts (less than 1%). At ileal villi, apoptotic cells were scattered only at tips, similar to observations made in the small intestines of rats, where this distribution was referred to as an apoptotic cuff (Fig. 2C) (43). Apoptotic cells were observed both in the depth of the villus tip and close to the epithelial surface (Fig. 2C). In PP, apoptotic cells were equally distributed over the entire area of domed villi and germinal centers (Fig. 2D and E). Evaluation of apoptosis by the caspase 3 assay gave similar results. Ac-DEVD-AMC cleavage activities were demonstrable both in the ileum and in ileal PP (the medians were 2,209 [range, 2,027 to 2,486] and 1,215 [range, 866 to 2,194], respectively).

TABLE 3.

Median apoptotic indices in the ileum and ileal PP after infection with REPEC O103 as evaluated by the TUNEL assay and by apoptotic morphology (H&E staining)a

| Intestinal tissue | Median (range) apoptotic index (%)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 0 | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | |

| Tips of ileal absorptive villi | 3.6 (1.6–16.8), 3.8 (1.5–9.4) | 3 (2.1–6.3), 4.6 (3.2–5) | 3.8 (3–4), 3.4 (2.5–3.8) | 2.4 (0.9–5), 1.1 (0.8–3.2)b |

| Ileal crypts | 0.4 (0.3–2.6), 0.5 (0.2–1.8) | 0.6 (0.2–1.5), 0.9 (0.3–1.8) | 1.8 (1–2), 1.4 (1–1.5) | 0.8 (0.3–2.5), 0.7 (0.5–2.2) |

| Tips of PP absorptive villi | 3.8 (2.1–8.1), 3.8 (2–5.8) | 2.5 (0.3–3.6), 2.7 (0.4–3) | 4.6 (4.6–4.7), 3.5 (2.3–4.2) | 4.3 (1.8–5.6), 3.6 (1.8–5.9) |

| PP domed villi | 8.1 (2.7–13.7), 8.1 (5.2–14) | 5.8 (5–16.5), 6.3 (5.2–14.5) | 9.2 (9–9.4), 8.7 (6.4–9.4) | 3.6 (1.3–11), 3.5 (2.4–8.6) |

| PP germinal center | 11 (3.5–44), 14.7 (6–31.2) | 20 (6.2–24), 9.8 (6–19) | 10.5 (2–19), 4.5 (3.5–19.8) | 3.1 (1.2–8.1),b 6.6 (2.6–3.3) |

The values determined by the TUNEL assay are followed by those determined by H&E staining. A total of 10 randomly selected fields was assessed at each intestinal site. Results for control rabbits (group 0) and rabbits with mild (group 1), moderate (group 2), or severe (group 3) disease symptoms after experimental infection are shown.

Significantly different (P < 0.05) from value for the noninfected control group as calculated by the Mann-Whitney U test.

Indigenous Enterobacteriaceae have no influence on the incidence of apoptosis.

The presence of indigenous Enterobacteriaceae in the rabbit intestine (four of eight rabbits within group 0) had no influence on apoptosis levels in the ileum or ileal PP. Apoptotic indices evaluated by TUNEL or H&E staining were similar to those found in tissues from rabbits that were culture free of Enterobacteriaceae (Table 4). Likewise, Ac-DEVD-AMC cleavage activities in tissues with and without Enterobacteriaceae had similar levels in the ileum (medians were 2,209 [range, 2,027 to 2,455] and 2,289 [range, 2,094 to 2,486], respectively) and in ileal PP (medians were 1,276 [range, 1,100 to 1,437] and 1,104 [range, 866 to 2,194], respectively). The values did not differ significantly from each other.

TABLE 4.

Median apoptotic indices in the ileum and ileal PP of control rabbits with and without colonization by indigenous Enterobacteriaceae as evaluated by the TUNEL assay and by apoptotic morphology (H&E staining)a

| Intestinal tissue | Median (range) apoptotic index (%)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Enterobacteriaceae | No Enterobacteriaceae | |

| Tips of ileal absorptive villi | 3.7 (2.8–16.8), 4.7 (3.5–9.4) | 2.7 (1.6–5.3), 2.2 (1.5–6.5) |

| Ileal crypts | 1.2 (0.3–2.6), 0.8 (0.4–1.8) | 0.3 (0.3–0.7), 0.4 (0.2–0.5) |

| Tips of PP absorptive villi | 3.8 (3.8–8.1), 3.8 (2.4–5.6) | 3.6 (2.1–6.4), 3.5 (2–5.8) |

| PP domed villi | 8.1 (6.7–10), 8.1 (6–9.8) | 8.9 (2.7–13.7), 8.8 (5.2–14) |

| PP germinal center | 10.9 (8.5–11), 12.8 (9.4–17.5) | 17.9 (3.5–44), 19.4 (6–31.2) |

Values determined by the TUNEL assay are followed by those determined by H&E staining. A total of 10 randomly selected fields was assessed at each intestinal site.

Decrease in apoptosis in the ileum and ileal PP after infection with REPEC O103 evaluated by TUNEL staining.

For apoptotic assessment, rabbits were grouped according to disease severity after infection with REPEC O103 strains. Group 0 (n = 8) contained control rabbits or animals that did not show disease symptoms. Group 1 (n = 3) showed mild symptoms (soft stool pellets with up to 7 × 107 CFU of the inoculated pathogen/g of stool, reduced weight gain, and adherence of low numbers of bacteria to intestinal surfaces as evaluated by SEM). Group 2 (n = 3) showed moderate disease (soft to watery stools with up to 5 × 109 CFU/g, weight loss, and bacterial adherence in moderate numbers). Group 3 (n = 5) experienced severe disease (diarrhea with up to 4 × 1011 CFU/g, severe weight loss, and adherence of high numbers of the pathogen). Apoptosis was assessed at tips of ileal absorptive villi and in the ileal crypt regions, as well as at tips of PP absorptive villi, PP domed villi, and PP germinal centers (Table 3).

In tips of ileal absorptive villi, PP domed villi, and PP germinal centers, apoptotic cells progressively decreased as disease symptoms increased. When disease symptoms were severe (group 3), masses of bacteria could be seen diffusely lining the intestinal surface at ileal villus tips. They exhibited a distinct dark brown staining, probably due to increased bacterial DNA synthesis (Fig. 3E and F). At this time-point, the physiological incidence of apoptotic cells could no longer be detected. Apoptotic cells were rarely seen beneath attachment sites. Additionally, the number of apoptotic cells in the depth of the villus tips was decreased. Occasionally, apoptotic cells were seen in the intestinal lumen (consistent with the observation that apoptotic intestinal cells are often shed into the lumen) (Fig. 3F). Similarly, domed villi and germinal centers of PP had fewer apoptotic cells when disease was severe (Fig. 3G and H). In germinal centers, the apoptotic index of group 3 differed significantly from that of group 0 (P = 0.01, Mann-Whitney U test). In ileal crypts and tips of PP absorptive villi, levels of apoptosis remained more or less unchanged among the four rabbit groups.

Decrease in apoptosis in the ileum and ileal PP after infection with REPEC O103 evaluated by morphologic assessment (H&E staining).

Rabbits were grouped, and intestinal sites were examined for the presence of apoptotic cells as already described (Table 3). Consistent with the observations made after TUNEL staining, the number of apoptotic cells in the ileum and ileal PP progressively decreased as disease symptoms increased. In ileal villi, the apoptotic index of group 3 differed significantly from that of group 0 (P = 0.04, Mann-Whitney U test). In PP, both domes and germinal centers showed decreased apoptosis, reaching borderline significance in group 3 (domes, P = 0.06; germinal centers, P = 0.06). Levels of apoptosis in ileal crypts and PP villus tips remained constant.

Decrease in apoptotic activity in the ileum after infection with REPEC O103 evaluated with the caspase 3 assay.

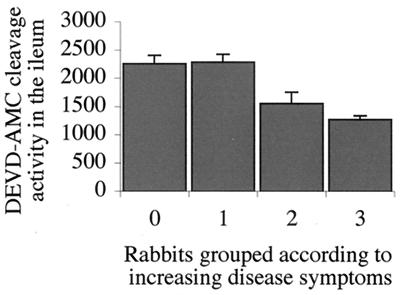

To measure intestinal caspase 3 activation, whole lysates from rabbit ileum and ileal PP (without differentiation among absorptive villi, crypts, domed villi, or germinal centers) were incubated with the caspase 3 fluorescent substrate Ac-DEVD-AMC and fluorescence excitation of AMC was measured. To compare cleavage activities among rabbit tissues, animals were grouped based on disease symptoms as described above. Distinct caspase 3 activity was evident in ileal tissue samples from both uninfected control rabbits and animals that did not respond or only slightly responded to REPEC O103 infection (Fig. 4). When disease symptoms were moderate or severe (groups 2 and 3), levels of activated caspase 3 were significantly decreased (P = 0.01 and 0.003, respectively; Mann-Whitney U test). Apoptotic activities in PP were, in general, lower than in ileal tissues and did not significantly differ within the four animal groups.

FIG. 4.

Mean Ac-DEVD-AMC cleavage activity in the rabbit ileum evaluated with the caspase 3 assay after experimental infection with REPEC O103. Groups: 0, control rabbits; 1, 2, and 3, rabbits with mild, moderate, and severe disease symptoms, respectively. The mean apoptotic incidence dropped significantly when disease symptoms were moderate (P = 0.01, Mann-Whitney U test) or severe (P = 0.003).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we demonstrated that apoptosis physiologically occurs in the rabbit ileum. When REPEC O103 disease was fully established and animals had heavy diarrhea, apoptosis was significantly decreased in the rabbit ileum and ileal PP. Tips of ileal absorptive villi and germinal centers of PP were the sites of most apparent changes in apoptotic activity.

It is known that apoptosis maintains a continuous 3- to 6-day cell turnover in the small intestines of humans and rats, where the Fas ligand and receptor are coexpressed (12, 17). The number of apoptotic cells increases from ileal crypts to ileal villus tips with the formation of an apoptotic cuff before enterocytes are shed into the lumen (16, 42, 43; S. F. Moss and P. R. Holt, Letter, Gastroenterology 111:567–568, 1996). In our study, we demonstrated that the rabbit ileum shows similar features of physiological apoptosis, with apoptotic cells sparse in the ileal crypt region but increasingly scattered toward the villus tip. In addition, high levels of caspase 3 activity in tissues obtained from control rabbits confirm that the ileum is a site of physiological cell turnover. In particular, we noticed a high incidence of apoptosis in germinal centers of PP. This observation is attributable to germinal centers harboring large numbers of activated immune cells that contain granzyme B, which activates caspase 3. Interestingly, we also found that the presence of indigenous nonadherent Enterobacteriaceae had no apparent influence on physiological levels of apoptosis. Apoptotic indices were equal in animals with or without cultivatable Enterobacteriaceae. This may indicate that the regulatory machinery for programmed cell death is not regulated by the indigenous ileal flora. As the number of control rabbits colonized by Enterobacteriaceae was relatively small (n = 4), further studies using a larger number of animals are required to determine if indigenous nonadherent Enterobacteriaceae affect the physiological levels of apoptosis.

The various REPEC O103 strains that were used for the experimental infection are considered highly pathogenic. They were isolated from Spanish and Belgian rabbits experiencing severe diarrhea (1, 3). Our in vitro studies showed that all of the strains adhered well to cultured cells and triggered actin accumulation and tyrosine phosphorylation, features that are critical for EPEC disease. We believe that the various isolates are almost identical in pathogenicity. We therefore grouped animals only according to disease symptoms that occurred after experimental infection, regardless of the strain that was used to infect the animals.

Invasive enteropathogens (such as Shigella, Salmonella, and enteroinvasive E. coli species) trigger enhanced expression of proinflammatory genes in intestinal epithelial cells, which subsequently causes a massive increase in the incidence of apoptotic cells in the epithelium and PP lymphoid follicles (22, 46). Similarly, E. coli strains such as Shiga toxin-producing EHEC O157:H7 and verotoxin-producing AEEC O5:H− promote cytokine expression, followed by increased apoptosis (20, 41). These infections that result in activation and proliferation of immune cells are usually accompanied by an enhanced release of granzyme B, resulting in the increase in apoptosis (44). Noninvasive and non-toxin-producing EPEC, EHEC, RDEC-1, and C. rodentium, however, are believed to decrease cytokine release, which might decrease levels of apoptosis (26). In addition, EPEC activates intracellular pathways that are believed to promote slower host cell killing (7, 36, 39). In this study, we observed that the incidence of apoptosis was not increased after infection with REPEC O103. Even though severe REPEC O103 infection is characterized by increased inflammation with a massive influx of inflammatory cells into the ileal villi, apoptosis was decreased in the ileum (as shown by a caspase 3 assay), particularly at the tips of ileal absorptive villi (as determined by H&E staining) and in germinal centers of PP (as shown by TUNEL staining). It is tempting to interpret the decrease in the number of apoptotic cells as a decrease in the rate of apoptosis, suggesting that REPEC O103 may, in fact, decrease apoptosis. However, the decrease in the incidence of apoptotic cells may also be attributable to the influx of lymphocytes and macrophages into the immune compartment and therefore the relative increase in their numbers there. In this instance, the rate of apoptosis may remain constant but the rate of clearance of apoptotic debris by macrophages may be increased. This may well be the case, as apoptotic cells undergo surface changes to ensure rapid phagocytosis by macrophages. Investigations into this matter, however, are beyond the scope of this study.

As shown in Table 3, apoptotic indices did not differ significantly among groups 0, 1, and 2. Eventually, values even increased in groups 1 and 2. Only when disease was severe (group 3 rabbits) did the decrease become significant. At this time, tissue morphology and cell composition had dramatically changed. It may be the case that the rabbit host initially attempted to clear the infection. Apoptosis may have been initially increased. Simultaneously or later on, the host may have tried to discard the attached pathogen and to restore intestinal cell integrity by shedding damaged epithelial cells, together with apoptotic cells, into the lumen (Fig. 3F). This may explain the observed fluctuations in the incidence of apoptosis in rabbits that were not severely diseased yet. It may reflect an immune response to an intestinal infection in general. Only when REPEC O103 disease was fully established was the decrease in apoptosis attributable to the pathogen. Whatever the case, this is an alternative interpretation. Yet, it was striking that intestinal segments harbored fewer apoptotic cells where masses of bacteria were attached (Fig. 3F). In summary, it seems obvious that REPEC O103 does not promote apoptosis compared to other enteropathogens such as Salmonella and Shigella species. REPEC O103, and possibly EPEC, may have evolved survival strategies to escape host cell defenses. Alternatively, as these pathogens remain attached to host cells for the duration of the infection, pathogenic potential may be enhanced by prolonging the life of the host cell. Studies with a larger number of animals may help to consolidate our findings and to precisely determine initial apoptotic fluctuations and events that occur later on, when the disease is established.

We demonstrated that apoptotic activities were significantly diminished in germinal centers of ileal PP when tissues were assessed by the TUNEL assay. However, apoptotic activities did not differ significantly within the four animal groups when PP were assessed by the caspase 3 assay. As whole lysates from ileal PP had to be processed for this assay, evaluation of single compartments was not possible, in contrast to the TUNEL assay, where light microscopic assessment allows differentiation of various fields. Thus, with the caspase 3 assay, apoptotic changes in PP germinal centers alone may not be sufficient to demonstrate deviations in apoptotic levels of the entire PP.

Caspase 3 plays a key role in the regulation of apoptosis. Inhibition of caspase 3, as observed in the ileum, prevents cell death by apoptosis. It has yet to be determined whether virulence proteins secreted by REPEC O103 directly inhibit caspase 3 activities. The pathogen may also inhibit apoptosis by altering the expression of Fas or FasL or producing analogues that bind to Fas but do not activate the apoptotic signal transduction pathways. It is also possible that the pedestals themselves influence the occurrence of apoptosis.

Collectively, these findings show that REPEC O103, in contrast to most other enteropathogens, does not promote apoptosis. In contrast, REPEC O103 seems to decrease apoptosis in the ileum and in germinal centers of ileal PP. If this is the case, REPEC O103 may have evolved strategies to slow down physiological cell turnover and thus to extend the time of its own attachment and to delay rapid clearance of the infection. EPEC strains thus may have evolved this strategy to counteract host cell defense mechanisms. Elucidation of the mechanisms by which these pathogens inhibit apoptosis may hold therapeutic potential for diseases caused by enhanced apoptosis (e.g., autoimmune disorders).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jorge Blanco, Johan E. Peeters, Phillip Tarr, and Michael Davis for sending the rabbit EPEC and EHEC strains. We thank Ronald H. Silverman, Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y., for help with the statistical analysis and Julie Chow for technical assistance with the histology studies.

This work was supported by a Howard Hughes International Research Scholar Award and an operating grant to B.B.F. from the Medical Research Council of Canada (MRC). B.B.F. is an MRC Scientist.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe A, Heczko U, Hegele R G, Finlay B B. Two enteropathogenic Escherichia coli type III secreted proteins, EspA and EspB, are virulence factors. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1907–1916. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.10.1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berg R D. Inhibition of Escherichia coli translocation from the gastrointestinal tract by normal cecal flora in gnotobiotic or antibiotic-decontaminated mice. Infect Immun. 1980;29:1073–1081. doi: 10.1128/iai.29.3.1073-1081.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blanco J E, Blanco M, Blanco J, Mora A, Balaguer L, Mourino M, Juarez A, Jansen W H. O serogroups, biotypes, and eae genes in Escherichia coli strains isolated from diarrheic and healthy rabbits. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:3101–3107. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.12.3101-3107.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Camguilhem R, Milon A. Biotypes and O serogroups of Escherichia coli involved in intestinal infections of weaned rabbits: clues to diagnosis of pathogenic strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:743–747. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.4.743-747.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheney C P, Schad P A, Formal S B, Boedeker E C. Species specificity of in vitro Escherichia coli adherence to host intestinal cell membranes and its correlation with in vivo colonization and infectivity. Infect Immun. 1980;28:1019–1027. doi: 10.1128/iai.28.3.1019-1027.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crane J K, Majumdar S, Pickhardt D F., 3rd Host cell death due to enteropathogenic Escherichia coli has features of apoptosis. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2575–2584. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.5.2575-2584.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crane J K, Oh J S. Activation of host cell protein kinase C by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3277–3285. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3277-3285.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donnenberg M S, Calderwood S B, Donohue-Rolfe A, Keusch G T, Kaper J B. Construction and analysis of TnphoA mutants of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli unable to invade HEp-2 cells. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1565–1571. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.6.1565-1571.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B, Finlay B B. Interactions between enteropathogenic Escherichia coli and host epithelial cells. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:109–114. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01000-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fagundes-Neto U, Freymuller E, Gandolfi Schimitz L, Scaletsky I. Nutritional impact and ultrastructural intestinal alterations in severe infections due to enteropathogenic Escherichia coli strains in infants. J Am Coll Nutr. 1996;15:180–185. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1996.10718586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giron J A, Ho A S, Schoolnik G K. An inducible bundle-forming pilus of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Science. 1991;254:710–713. doi: 10.1126/science.1683004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Granville D J, Carthy C M, Hunt D W, McManus B M. Apoptosis: molecular aspects of cell death and disease. Lab Investig. 1998;78:893–913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Griffin P M, Ostroff S M, Tauxe R V, Greene K D, Wells J G, Lewis J H, Blake P A. Illnesses associated with Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections. A broad clinical spectrum. Ann Intern Med. 1988;109:705–712. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-109-9-705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heczko U, Abe A, Finlay B B. In vivo interactions of rabbit enteropathogenic Escherichia coli O103 with its host: an electron microscopic and histopathologic study. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:5–16. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)00291-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heczko U, Abe A, Finlay B B. Segmented filamentous bacteria prevent colonization of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli O103 in rabbits. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1027–1033. doi: 10.1086/315348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iwanaga T, Hoshi O, Han H, Takahashi-Iwanaga H, Uchiyama Y, Fujita T. Lamina propria macrophages involved in cell death (apoptosis) of enterocytes in the small intestine of rats. Arch Histol Cytol. 1994;57:267–276. doi: 10.1679/aohc.57.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones B A, Gores G J. Physiology and pathophysiology of apoptosis in epithelial cells of the liver, pancreas, and intestine. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:G1174–G1188. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.6.G1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones N L, Day A S, Jennings H A, Sherman P M. Helicobacter pylori induces gastric epithelial cell apoptosis in association with increased Fas receptor expression. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4237–4242. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.4237-4242.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaper J B, McDaniel T K, Jarvis K G, Gomez-Duarte O. Genetics of virulence of enteropathogenic E. coli. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1997;412:279–287. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1828-4_47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karpman D, Hakansson A, Perez M T, Isaksson C, Carlemalm E, Caprioli A, Svanborg C. Apoptosis of renal cortical cells in the hemolytic-uremic syndrome: in vivo and in vitro studies. Infect Immun. 1998;66:636–644. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.636-644.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kenny B, DeVinney R, Stein M, Reinscheid D J, Frey E A, Finlay B B. Enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) transfers its receptor for intimate adherence into mammalian cells. Cell. 1997;91:511–520. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80437-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim J M, Eckmann L, Savidge T C, Lowe D C, Witthoft T, Kagnoff M F. Apoptosis of human intestinal epithelial cells after bacterial invasion. J Clin Investig. 1998;102:1815–1823. doi: 10.1172/JCI2466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kiyokawa N, Taguchi T, Mori T, Uchida H, Sato N, Takeda T, Fujimoto J. Induction of apoptosis in normal human renal tubular epithelial cells by Escherichia coli Shiga toxins 1 and 2. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:178–184. doi: 10.1086/515592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levine M M, Bergquist E J, Nalin D R, Waterman D H, Hornick R B, Young C R, Sotman S. Escherichia coli strains that cause diarrhoea but do not produce heat-labile or heat-stable enterotoxins and are non-invasive. Lancet. 1978;i:1119–1122. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)90299-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malstrom C, James S. Inhibition of murine splenic and mucosal lymphocyte function by enteric bacterial products. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3120–3127. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3120-3127.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mills S D, Boland A, Sory M P, van der Smissen P, Kerbourch C, Finlay B B, Cornelis G R. Yersinia enterocolitica induces apoptosis in macrophages by a process requiring functional type III secretion and translocation mechanisms and involving YopP, presumably acting as an effector protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12638–12643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Milon A, Esslinger J, Camguilhem R. Adhesion of Escherichia coli strains isolated from diarrheic weaned rabbits to intestinal villi and HeLa cells. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2690–2695. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.8.2690-2695.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monack D M, Mecsas J, Bouley D, Falkow S. Yersinia-induced apoptosis in vivo aids in the establishment of a systemic infection of mice. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2127–2137. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.11.2127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neter E. Enteritis due to enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Am J Dig Dis. 1965;10:883–886. doi: 10.1007/BF02236098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peeters J E, Geeroms R, Orskov F. Biotype, serotype, and pathogenicity of attaching and effacing enteropathogenic Escherichia coli strains isolated from diarrheic commercial rabbits. Infect Immun. 1988;56:1442–1448. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.6.1442-1448.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peeters J E, Pohl P, Okerman L, Devriese L A. Pathogenic properties of Escherichia coli strains isolated from diarrheic commercial rabbits. J Clin Microbiol. 1984;20:34–39. doi: 10.1128/jcm.20.1.34-39.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pillien F, Chalareng C, Boury M, Tasca C, de Rycke J, Milon A. Role of adhesive factor/rabbit 2 in experimental enteropathogenic Escherichia coli O103 diarrhea of weaned rabbit. Vet Microbiol. 1996;50:105–115. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(96)00012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Richter-Dahlfors A, Buchan A M J, Finlay B B. Murine salmonellosis studied by confocal microscopy: Salmonella typhimurium resides intracellularly inside macrophages and exerts a cytotoxic effect on phagocytes in vivo. J Exp Med. 1997;186:569–580. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.4.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roach S, Tannock G W. Indigenous bacteria influence the number of Salmonella typhimurium in the ileum of gnotobiotic mice. Can J Microbiol. 1979;25:1352–1358. doi: 10.1139/m79-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenshine I, Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B, Finlay B B. Signal transduction between enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) and epithelial cells: EPEC induces tyrosine phosphorylation of host cell proteins to initiate cytoskeletal rearrangement and bacterial uptake. EMBO J. 1992;11:3551–3560. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05438.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rosenshine I, Ruschkowski S, Stein M, Reinscheid D J, Mills S D, Finlay B B. A pathogenic bacterium triggers epithelial signals to form a functional bacterial receptor that mediates actin pseudopod formation. EMBO J. 1996;15:2613–2624. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rothbaum R J, Partin J C, Saalfield K, McAdams A J. An ultrastructural study of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli infection in human infants. Ultrastruct Pathol. 1983;4:291–304. doi: 10.3109/01913128309140582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Savkovic S D, Koutsouris A, Hecht G. Activation of NF-kappaB in intestinal epithelial cells by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:C1160–7. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.4.C1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tarr P I, Fouser L S, Stapleton A E, Wilson R A, Kim H H, Vary J C, Jr, Clausen C R. Hemolytic-uremic syndrome in a six-year-old girl after a urinary tract infection with Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli O103:H2. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:635–638. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608293350905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wada Y, Mori K, Iwanaga T. Apoptosis of enterocytes induced by inoculation of a strain of attaching and effacing Escherichia coli and verotoxin. J Vet Med Sci. 1997;59:815–818. doi: 10.1292/jvms.59.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watson A J. The role of apoptosis in intestinal disease. J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:414–423. doi: 10.1007/BF02934503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Westcarr S, Farshori P, Wyche J, Anderson W A. Apoptosis and differentiation in the crypt-villus unit of the rat small intestine. J Submicrosc Cytol Pathol. 1999;31:15–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zapata J M, Takahashi R, Salvesen G S, Reed J C. Granzyme release and caspase activation in activated human T-lymphocytes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:6916–6920. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.12.6916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zychlinsky A, Sansonetti P J. Apoptosis as a proinflammatory event: what can we learn from bacteria-induced cell death? Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:201–204. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zychlinsky A, Thirumalai K, Arondel J, Cantey J R, Aliprantis A O, Sansonetti P J. In vivo apoptosis in Shigella flexneri infections. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5357–5365. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5357-5365.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]