Abstract

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are involved in human monocyte activation by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and Staphylococcus aureus Cowan (SAC), suggesting that gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria may trigger similar intracellular events. Treatment with specific kinase inhibitors prior to cell stimulation dramatically decreased LPS-induced cytokine production. Blocking of the p38 pathway prior to LPS stimulation decreased interleukin-1α (IL-1α), IL-1ra, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) production, whereas blocking of the ERK1/2 pathways inhibited IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-1ra but not TNF-α production. When cells were stimulated by SAC, inhibition of the p38 pathway did not affect cytokine production, whereas only IL-1α production was decreased in the presence of ERK kinase inhibitor. We also demonstrated that although LPS and SAC have been shown to bind to CD14 before transmitting signals to TLR4 and TLR2, respectively, internalization of CD14 occurred only in monocytes triggered by LPS. Pretreatment of the cells with SB203580, U0126, or a mixture of both inhibitors did not affect internalization of CD14. Altogether, these results suggest that TLR2 signaling does not involve p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways, indicating that divergent pathways are triggered by gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, thereby inducing cytokine production.

Invasive infection by gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria in humans results in septic shock and death. The early cellular response to both groups of microorganisms is still unclear. Several investigators have proposed that lipopolysaccharides (LPS) from gram-negative bacteria, as well as several components from gram-positive bacteria, trigger monocytic cytokine production following interaction with membrane-bound CD14 (mCD14) and activation of Toll-like receptors (TLRs; the human homologues of Drosophila Toll) which are present on the cell membrane (23, 30, 43, 61). Several lines of evidence suggest that after binding to mC14, LPS initiates intracellular signaling pathways activating a number of tyrosine kinases as an initial step. Various α subunits of heterodimeric G proteins and Src kinases, physically associated with membrane-bound CD14 molecules in LPS-stimulated normal human monocytes, induce p38 mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase activation, which is involved in cytokine synthesis (44). Other proteins that are phosphorylated upon LPS stimulation include p42 and p44 MAP kinases, which are encoded by the erk2 and erk1 genes, respectively (10, 25). However, the upstream events that occur during ERK1, ERK2, and p38 kinase phosphorylation remain unclear. There is some evidence that LPS activates Ras and consequently Raf, resulting in MEK-1 and MAP kinase phosphorylation, but the precise pathways are not fully understood (8). In addition to MEK and MAP kinase activation, Syk molecules are phosphorylated upon LPS stimulation of macrophages. However, several studies have indicated that neither Syk, Src family tyrosine kinases, Hck, Lyn, nor Fgr is indispensable to the macrophage response to LPS (3, 9, 10, 45). LPS is also known to induce a strong NF-κB translocation which is involved in cytokine production (11, 12, 24, 57, 60). This phenomenon may depend on p38 MAP kinase activation (5, 39, 52). A CD14-dependent NF-κB translocation has been shown to occur upon stimulation of cells with Staphylococcus aureus (61). Altogether, these results suggest that gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria may trigger similar intracellular pathways following their interaction with CD14 and TLRs.

In this study, we compared cytokine production by human monocytes stimulated with Neisseria meningitidis LPS or heat-killed S. aureus Cowan (SAC) and cultured in the presence or absence of the specific p38, ERK1, and ERK2 kinase pathway inhibitors (32, 41). Several studies have shown that LPS, a major compound of the outer cell membrane of gram-negative bacteria, as well as peptidoglycans (PGN) and lipoteichoic acids (LTA) of gram-positive bacteria, elicit several of the biological effects reported to occur during bacterial infection and trigger similar intracellular events. Thus, Schwandner et al. reported recently (43) that LPS is capable of eliciting immunostimulatory effects similar to those elicited by whole bacteria and demonstrated that whole gram-positive bacteria (Streptococcus pyogenes) induced cell activation similar to that induced by PGN or LTA derived from the same bacteria, using HEK293 cells expressing TLR2. Moreover, data obtained using the murine macrophage RAW264,7 cell line or differentiated human THP-1 cell line demonstrated an activation of CREB/ATF and AP-1 transcription factors by PGN or by any other component of gram-positive bacteria (23). We demonstrated that both LPS and heat-killed SAC induce cytokine production but only LPS-mediated events are highly dependent on the p38, ERK1, and ERK2 kinase activation pathways. Furthermore, our data suggest that in inducing specific cytokine production, LPS and SAC trigger different pathways. We also demonstrated, for the first time, that interaction of LPS with CD14-positive monocytes induced internalization of mCD14, whereas SAC had no effect.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents and antibodies.

Endotoxin-free reagents and plastics were used in all experiments. BioWhittaker Europe (Verviers, France) provided RPMI 1640 (with l-glutamine) and penicillin-streptomycin. MSL (medium for separation of lymphocytes) was from Eurobio (Les Ulis, France). N. meningitidis LPS was obtained as previously described (56). Pansorbin cells (SAC) were from Calbiochem-Novabiochem Corporation (San Diego, Calif.). Biotest Pharma GmbH (Dreieich, Germany) provided chromatographically purified intravenous human immunoglobulin. Brefeldin A, saponin, formaldehyde, and bovine serum albumin (BSA) were from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.). Murine monoclonal anti-human molecule antibodies (MAbs) used in this study were anti-CD14 (My4)-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), anti-CD14 (My4)-phycoerythrin (PE), and isotypic controls from Immunotech (Beckman Coulter, Villepinte, France). Anti-CD3-peridenin chlorophyll protein (PerCP), anti-CD11b-PE, anti-CD15-FITC, anti-CD56-PE, anti-CD19-FITC, anti-CD14-allophycocyanin (APC), anti-interleukin-1α (IL-1α)-PE, anti-IL-1β-PE, anti-IL-1ra-PE, anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α)-APC, and anti-IL-8-PE antibodies and isotypic controls were from Becton Dickinson (Le Pont de Claix, France). Rabbit anti-fluorescein-Texas red conjugate was from Molecular Probes (Eugene, Oreg.). Proteinase K (from Tritirachium album) was from Interchim (Montlucon, France). Mowiol and MAP kinase p38 inhibitor SB203580 were from Calbiochem (La Jolla, Calif.). ERK1/2 cascade kinase inhibitor U0126 (MEK inhibitor) was from Promega (Madison, Wis.).

Enriched monocyte cell preparation.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated from buffy coats of healthy donors by centrifugation on an MSL gradient (Eurobio). For isolation of monocytes, suspensions of peripheral blood mononuclear cells were adjusted to 106 monocytes/ml of RPMI 1640. Percentage of monocytes was determined by flow cytometry or by nonspecific esterase staining using α-naphthyl acetate as the substrate (49). Cell suspensions containing 2 mM l-glutamine and antibiotics (100 U of penicillin-streptomycin per ml) were allowed to adhere to six-well plastic culture dishes (Costar, Cambridge, Mass.) in the absence of serum for 45 min at 37°C. Nonadherent cells were removed. Under these conditions, adherent cells contained more than 90% monocytes, as assessed by morphological analysis and immunohistochemical staining.

Induction of cytokine production.

Adherent cells were first incubated for 20 min at room temperature in medium with or without the kinase inhibitor SB203580 (5 μM) or U0126 (10 μM) or a mixture of SB203580 (5 μM) and U0126 (10 μM). Dose-response studies were performed to determine the amounts of kinase inhibitors required to obtain the maximum effect. Cell viability, measured using trypan blue, was not affected by the presence of the different inhibitors. Monocytes were cultured in the presence of N. meningitidis LPS (1 μg/106 cells/ml) or SAC (100 μg/106 cells/ml) in humidified 5% CO2 in air at 37°C. A dose response was determined for each stimulant of cytokine production. To avoid cytokine release, brefeldin A (10 μg/106 cells/ml) was present throughout the 18 h of stimulation. Assessment of cytokine production at a single-cell level was performed by fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis. In parallel experiments, cytokine mRNA expression was assessed after LPS stimulation for 3 h.

Phenotypical characterization of purified monocytes.

Membrane antigens of the cell subsets were analyzed by FACS using four-color direct immunofluorescence and MAbs conjugated with either FITC, PE, PerCP, or APC. Cells were incubated with decomplemented normal human AB serum (NHSAB, 1.5 ml) for 15 min at 4°C to decrease nonspecific binding and centrifuged. The pellet was incubated with the different MAbs for 30 min at 4°C; cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing azide (0.01%) and BSA (0.2%) and fixed using a 4% formaldehyde–PBS buffer solution for 5 min. The following mouse anti-human antibodies were used: anti-CD14 (My4)-FITC, anti-CD14 (My4)-PE, anti-CD14-APC, anti-CD3-PerCP, anti-CD56-PE, and anti-CD19-FITC.

Cytokine production.

Flow cytometric determination of intracellular IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-8, IL-1ra, and TNF-α production at the single-cell level was performed as previously described (15). Briefly, after stimulation, cells were saturated with NHSAB for 20 min at 4°C. The cell pellet was incubated with the different specific MAbs for 30 min at 4°C. Cells were washed twice with cold PBS containing azide (0.01%) and BSA (0.2%). Cells were then fixed for 10 min at 4°C with PBS containing 4% formaldehyde. Cells were washed in PBS. To assess cytokine production by monocytes, fluorescent MAbs (1 μg/106 cells) were used in the presence of 50 μl of saponin buffer (PBS containing 0.01% azide, 0.2% BSA, and 0.5% saponin), and cells were incubated for 20 min at room temperature. The following mouse anti-human cytokine antibodies were used: anti-IL-1α-PE, anti-IL-1β-PE, anti-IL-1ra-PE, anti-IL-8-PE, and anti-TNF-α-APC. Cells were washed first in saponin buffer and then in PBS. Samples were analyzed the same day.

FACS analysis.

Stained cells were analyzed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometer Systems, Palo Alto, Calif.) and the CellQuest software. Ten thousand events were collected in list mode files for each test. Fluorescence parameters were collected using a four-decade logarithmic amplification. Dead cells and lymphocytes were excluded by forward and side scatter gating. Monocyte cells were identified in the linear forward versus side scatter plot and by use of anti-CD14 MAb. The gated population did not contain neutrophils and did not express CD19, CD56, or CD3 molecules (data not shown). The area of positivity was determined using isotype-matched MAbs. In all experiments, the negative control peak was between 0 and 10 on the log scale with no changes in compensation values.

Analysis of cytokine mRNA expression by RPA.

Total RNA was extracted from stimulated cells using TRIzol (GIBCO/BRL, Life Technologies) as recommended by the manufacturer. The RNase protection assay (RPA) was carried out using a RiboQuant multiprobe kit (PharMingen, San Diego, Calif.). Briefly, multiprobe template sets hCK-2 (containing DNA templates for IL-12 p35, IL-12 p40, IL-10, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-1ra, IL-6, and gamma interferon [IFN-γ]), hCK-3 (containing DNA templates for TNF-β, TNF-α, IFN-γ, IFN-β, transforming growth factor β1 [TGF-β1], TGF-β2, and TGF-β3), and hCK-5 (containing DNA templates for RANTES, MIP-1α, MIP-1β, MCP-1, and IL-8) were used to synthesize the (α-32P)UTP-labeled probes (3,000 Ci/mmol, 10 mCi/ml; ICN Biomedicals NV/SA, Costa Mesa, Calif.) in the presence of a GACU nucleotide pool and T7 RNA polymerase. Hybridization using 2 μg of each targeted RNA was performed overnight and followed by digestion with RNase A-RNase T1 mix according to the PharMingen standard protocol. The samples were treated with proteinase K and then extracted with chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (50:1) and precipitated in the presence of 4 M ammonium acetate. The RNase-protected duplexes were resolved on an acrylamide-urea sequencing gel next to the undigested labeled probe and run at 50 W with 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA. The gel was absorbed onto filter paper, dried under vacuum at 80°C, and exposed on film (Kodak Biomax-MS) in a cassette with an intensifying screen at −70°C. Taking undigested probes as markers, a standard curve was plotted on semilog graph paper and used to establish the identity of RNase-protected bands in the experimental samples. The films were quantified using Molecular Analyst software (Bio-Rad, Ivry sur Seine, France). Each amount (arbitrary units) of mRNA for each cytokine was expressed as a percentage of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) present in each sample, to correct for potential differences in sample loading, and then normalized to the amount of GAPDH present in unstimulated cells.

CD14 internalization assays. (i) Fluorescence-quenching assay.

The fluorescence-quenching assay was adapted from the method described by Kitchens and Munford (29). Monocytes (106/ml) were incubated with or without N. meningitidis LPS (1 μg/106 cells/ml) for 5 min at 37°C. Cells were then washed with cold PBS, incubated for 20 min at 4°C in the presence of intravenous human immunoglobulin (0.2 mg/ml for 106 cells) to saturate Fc receptors, and washed again. Mouse human monoclonal anti-CD14 (My4)-FITC was added for 30 min at 4°C. Cells were washed in cold PBS and split into 100-μl aliquots. In one aliquot, cells were permeabilized as described above, and anti-CD14-FITC was added for 30 min at 4°C to allow intracellular CD14 staining. To prevent quenching of fluorescein during the fixing procedure, the intracellular pH was raised by incubating the cells in cold PBS containing 20 mM Tris (pH 8.0) and 3% paraformaldehyde. This aliquot was used for FACS measurement of total surface-exposed and intracellular CD14. Rabbit anti-fluorescein-Texas red conjugate (Molecular Probes) was added to a second aliquot (50 μg/ml, final concentration), and the cells were incubated on ice for 30 min to bind and efficiently quench the fluorescence of surface-exposed anti-CD14-FITC MAb. The cells were then washed in cold PBS, fixed in 1 ml of 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 3% paraformaldehyde for 30 min on ice, washed again, permeabilized, and incubated with anti-CD14 (My4)-FITC. To prevent quenching of fluorescein during the last procedure, the intracellular pH was raised as described above. This second aliquot allowed determination of intracellular anti-CD14-FITC. The mean fluorescence intensity in each cell population was analyzed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometer Systems) and the CellQuest software.

(ii) Laser confocal microscope imaging.

Monocytes (106/ml) were incubated with or without N. meningitidis LPS (1 μg/106 cells/ml) or SAC (100 μg/106 cells/ml) in culture dishes on sterilized 22- by 22-mm glass coverslips (no. 1; Cole Parmer, Vernon Hills, Ill.) for 5 min at 37°C. Adherent monocytes were pretreated with SB203580 and/or U0126 as described above. Cells were first stained using mouse human monoclonal anti-CD14-APC to detect mCD14, fixed, and then permeabilized to allow intracellular CD14 staining using mouse human monoclonal anti-CD14 (My4)-PE as described previously. Cells were further treated with or without 1 ml of ice-cold 0.02% proteinase K, kept on ice for 30 min, and then washed in cold PBS. Cells were fixed for 30 min on ice in 1 ml of 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 3% paraformaldehyde and then washed in PBS. Cells treated with proteinase K allowed detection of intracellular staining alone.

The slides were mounted with one drop of mounting solution (Mowiol) on poly-l-lysine-coated slides. Cells were viewed with a CLEICA TCS SP laser confocal imaging system equipped with an Arkr laser (Leica Microsystems, Heidelberg, Germany). A dual-wavelength laser was used to excite PE and APC fluorochromes at 488 and 647 nm, respectively. The fluorescence signals from the two fluorochromes were recorded sequentially (562 to 636 nm for PE/662 to 800 nm for APC). The power laser was adapted to avoid the effects of cell autofluorescence. For all confocal images presented, acquisition parameters were kept constant.

RESULTS

Effect of kinase inhibitors on mRNA cytokine expression by monocytes stimulated with LPS.

We first investigated the effects of p38 MAP kinase inhibitor SB203580 and MEK kinase inhibitor U0126, separately and together, on specific mRNA cytokine accumulation in purified human monocytes stimulated with LPS. Monocytes were treated with SB203580, U0126, or a mixture of SB203580 and U0126 for 20 min and then cultured in the presence of N. meningitidis LPS for 3 h at 37°C. Negative controls, without LPS stimulation but treated with SB203580, U0126, or a mixture of both kinase inhibitors, were also included. We assessed IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-1ra, IL-8, and TNF-α mRNA production in cultured monocytes by RPA using cytokine multiprobe templates (21). Stimulation with LPS increased IL-1α (10- to 20-fold increase), IL-1β (5- to 10-fold increase), IL-1ra (4- to 10-fold increase), and TNF-α (10- to 20-fold increase) mRNA levels compared to unstimulated monocytes (data not shown). mRNA for IL-8 was found in unstimulated cells and did not increase upon stimulation (data not shown). Pretreatment of the cells with SB203580 prior to LPS stimulation caused a marked decrease in IL-1α, IL-1ra, and TNF-α mRNA levels compared to LPS-stimulated cells (Table 1). Treatment of the cells with U0126 prior to LPS stimulation also induced a decrease in IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-1ra, and TNF-α mRNA expression compared to LPS-stimulated cells (Table 1). Addition of both inhibitors resulted in an additive inhibition for IL-1ra and TNF-α compared to cells pretreated with only one inhibitor (Table 1). Results for unstimulated cells were similar to those obtained in the presence of SB203580 and/or U0126 alone (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

RPA analysis of mRNA expression for IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-1ra, and TNF-α by LPS-stimulated monocytesa

| Treatment | % Inhibition of cytokine mRNA levelsb (mean ± SEM)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1α | IL-1β | IL-1ra | TNF-α | |

| LPS + SB203580 | 56 ± 7∗ | 0.1 ± 0.01 | 24 ± 13∗ | 64 ± 7∗ |

| LPS + U0126 | 65 ± 25∗ | 61 ± 12∗ | 32 ± 9∗ | 50 ± 6∗ |

| LPS + SB203580+U0126 | 77 ± 11∗ | 64 ± 3∗ | 53 ± 6∗ | 91 ± 6∗ |

Purified human monocytes (106/ml) were treated with 5 μM SB203580, with 10 μM U0126, or with a mixture of SB203580 and U0126 and cultured for 3 h at 37°C with LPS (1 μg/ml). Total cellular RNA was isolated after 3 h of culture and hybridized with 32P-labeled riboprobes. Following RNase digestion, samples were resolved by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and gels were exposed on film. Quantification of cytokine mRNA levels was first normalized to the amount of GAPDH present in each sample and to the GAPDH present in unstimulated cells.

Compared to unstimulated cells. Results are those obtained from five experiments performed with cells from different donors. ∗, P < 0.01.

Effect of kinase inhibitors on cytokine production by monocytes stimulated with LPS.

We further investigated intracellular cytokine production by human monocytes of healthy donors by means of flow cytometry using specific labeled MAbs directed against IL-1α, IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-1ra, and IL-8. Cells were first treated with SB203580, U0126, or a mixture of both inhibitors for 20 min and then cultured in the presence of N. meningitidis LPS for 30 min, 3 h, and 18 h at 37°C. Stimulations were performed in the presence of brefeldin A to avoid the release of cytokines in the culture supernatant. Negative controls included unstimulated cells or cells cultured in the presence of inhibitors alone. When treated cells were cultured in the presence of LPS, we observed intracellular IL-1α (18% versus 0% positive cells), IL-1β (53% versus 0% positive cells), IL-8 (59% versus 23% positive cells), IL-1ra (17% versus 0% positive cells), and TNF-α (59% versus 0% positive cells) production by CD14-positive-cells compared to cells cultured in the absence of LPS (Table 2). The first cytokine to accumulate intracellularly was IL-8 (30 min), whereas IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-1ra and TNF-α were detectable after 3 h of culture (data not shown) and all cytokine levels were maximal after 18 h of culture (Table 2). When SB203580-treated cells were cultured in the presence of LPS, intracellular IL-1α and IL-1ra production was inhibited compared to cells cultured in the presence of LPS alone (5% versus 18% and 3% versus 17% positive cells, respectively) (Table 2), and intracellular production of TNF-α was partially inhibited (40% versus 59%) (Table 2). The percentage of IL-1β- and IL-8-positive cells was not affected by pretreatment with SB203580 (50% versus 53% and 63% versus 59% positive cells, respectively) (Table 2). When cells were cultured in the presence of MEK inhibitor prior to LPS stimulation, intracellular production of IL-1α and IL-1ra was blocked (7% versus 18% and 4% versus 17% positive cells, respectively), that of IL-1β was partially inhibited (22% versus 53% positive cells), and that of TNF-α was unaffected (54% versus 59% positive cells) (Table 2). The presence of MEK inhibitor increased intracellular IL-8 content in cells stimulated with LPS even though the number of IL-8-positive cells decreased (data not shown). When monocytes were cultured in the presence of a mixture of both inhibitors (SB203580 and U0126), the production of IL-1α, IL-1ra, and TNF-α by LPS-stimulated cells was totally inhibited whereas that of IL-1β was partially inhibited. Intracellular IL-8 production was decreased but to a lesser extent (Table 2). Both inhibitors did not affected cell viability (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Effects of SB203580 and U0126 on intracellular IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-8, IL-1ra and TNF-α production by LPS-stimulated monocytesa

| Treatment | % of cytokine-positive CD14+-gated monocytesb

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1α | IL-1β | IL-8 | IL-1ra | TNF-α | |

| RPMI | 1 | 1 | 12 | 2 | 3 |

| LPS | 18 | 53 | 59 | 17 | 59 |

| LPS + SB203580 | 5 | 50 | 63 | 3 | 40 |

| LPS + U0126 | 7 | 22 | 43 | 4 | 54 |

| LPS + SB203580 + U0126 | 0 | 15 | 47 | 0 | 4 |

Purified human monocytes (106/ml) were cultured for 18 h at 37°C without or with LPS (1 μg/ml) and treated with 5 μM SB203580, with 10 μM U0126, or with a mixture of SB203580 and U0126. Intracellular cytokine production was detected using either specific monoclonal anti-cytokine-PE or anti-cytokine-APC. An isotypic control was used as a negative control. Monocytes were gated using either anti-CD14-FITC or anti-CD14-PE MAbs. At least 5,000 CD14+ events were acquired for intracellular cytokine analysis.

Compared to isotypic negative controls. Results are those depicted from one representative experiment out of eight obtained with cells from different donors.

CD14 internalization in LPS-stimulated monocytes.

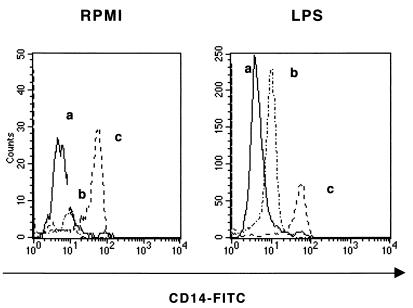

As it is proposed that cytokine production by LPS-stimulated monocytes is dependent on CD14 expression, we investigated whether the inhibitory effect of kinase inhibitors on this cytokine production was due to a downmodulation of the CD14 molecule. Several authors have suggested that CD14 internalization is the first step in cellular events after stimulation with LPS (13, 47, 48). First, we assessed LPS-induced CD14 internalization in monocytes by the fluorescence-quenching assay. The fluorescence histograms depicted in Fig. 1 indicate that CD14 was internalized in most of the monocytes stimulated with LPS for 5 min compared to unstimulated cells.

FIG. 1.

Measurement of mCD14 and intracellular CD14 by fluorescence-quenching assay. mCD14 and intracellular CD14 were detected by staining unstimulated monocytes (left) and LPS-stimulated monocytes (1 μg/ml) (right) with anti-CD14-FITC MAba. Histograms represent cells incubated with (b) or without (c) rabbit anti-fluorescein-Texas red conjugate, fixed, and analyzed by FACS. At least 3,000 CD14+ events/sample were acquired for analysis. An isotypic control was used as negative control (a). Results are expressed as log green fluorescence intensity versus number of cells. Results are those from one representative experiment out of three performed with cells from different donors.

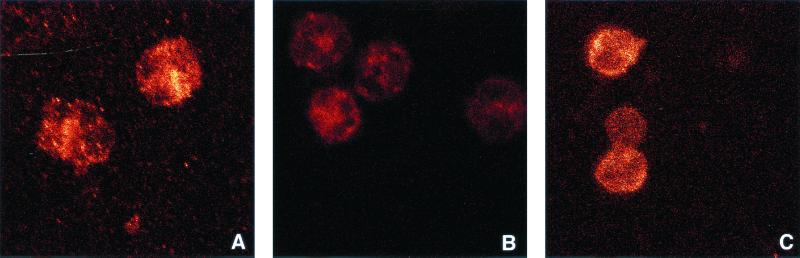

In another set of experiments, we used laser confocal microscopy to visualize the effect of the kinase inhibitors on CD14 trafficking. mCD14 and intracellular CD14 were detected using anti-CD14-APC and anti-CD14-PE MAbs. To avoid interchannel cross-talk phenomena, fluorescence signals from the two fluorochromes were recorded sequentially, and the power laser was adapted to avoid the effects of cell autofluorescence. In unstimulated cells, monocytes strongly expressed CD14 on the cell membrane (Fig. 2A), whereas intracellular CD14 was undetectable (Fig. 2E). Treatment of the cells with proteinase K removed the fluorescence signal (anti-CD14-APC antibodies) from the cell membrane (Fig. 2B). When cells were stimulated with LPS, CD14 was mostly internalized (Fig. 2G), with very few focal accumulations remaining on the cell surface (Fig. 2C). The latter were abolished upon treatment by proteinase K (Fig. 2D). However, the resolution of this method is not sufficient to distinguish whether the foci at the cell periphery are on the outer or the inner membrane, and we cannot exclude the possibility that some of these foci represent CD14 that accumulates in membrane invaginations. Treatment of LPS-stimulated cells with proteinase K did not abolish the fluorescence signal (anti-CD14-PE), confirming that CD14 is internalized (Fig. 2H). When monocytes were pretreated with SB203580, U0126, or a mixture of both inhibitors, CD14 internalization was not downmodulated upon LPS stimulation (Fig. 3). As the results depicted in Fig. 2 and 3 were obtained with the same cell preparation at the same time using the same acquisition parameters, we compared the pixel brightness of Fig. 2G and 3A. We observed a 47% increase in CD14 internalization when cells were pretreated with p38 MAP kinase inhibitor compared to cells stimulated with LPS alone (31,315 pixels versus 670 pixels per equivalent surface units).

FIG. 2.

Assessment of CD14 internalization in LPS-stimulated monocytes by laser confocal microscopy. mbound CD14 (A to D) and intracellular CD14 (E to H) were detected by staining unstimulated monocytes (A, B, E, and F) and monocytes stimulated with LPS (1 μg/106/ml) (C, G, D, and H) with antibodies as described in Materials and Methods. Cells were then treated with proteinase K (B, D, F, and H) to remove mCD14, fixed, and mounted on slides. Results are those from one representative experiment out of three performed with cells from different donors.

FIG. 3.

Effects of kinase inhibitors on CD14 internalization viewed by laser confocal microscopy. Purified human monocytes (106/ml) were first treated with SB203580 (5 μM) (A), U0126 (10 μM) (B), or a mixture of both inhibitors (C) and then stimulated with LPS (1 μg/106/ml) as described in Materials and Methods. Intracellular CD14 was detected as described for Fig. 4. Results are those from one representative experiment out of three performed with cells from different donors.

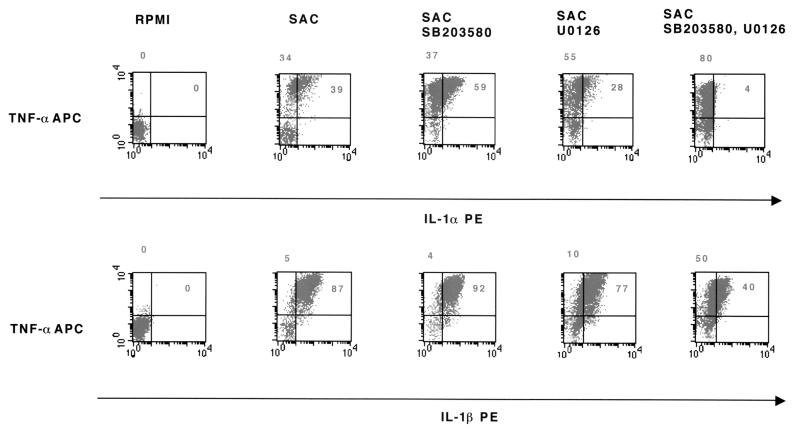

Effects of kinase inhibitors on cytokine production by monocytes stimulated with SAC.

To investigate if SAC induces intracellular events similar to those induced by LPS, we treated monocytes with SB203580, U0126, or a mixture of both kinase inhibitors for 1 h and then stimulated them with SAC. We observed (Table 3) that SAC stimulation was more efficient in inducing cytokine production than LPS stimulation: IL-1α (37% versus 18% positive cells), IL-1β (77% versus 53% positive cells), IL-8 (70% versus 59% positive cells), IL-1ra (21% versus 17% positive cells), and TNF-α (78% versus 59% positive cells). When cells were precultured with kinase inhibitors, SB203580 partially inhibited intracellular production of IL-8 and IL-ra (Table 3). U0126 partially inhibited the intracellular production of IL-1α but did not affect IL-1β, IL-8, IL-1ra, and TNF-α production compared to cells stimulated with SAC alone (Table 3 and Fig. 4). When monocytes were treated with both inhibitors prior to SAC stimulation, only IL-1α production was partially inhibited (18% versus 36%). Production of IL-1ra, IL-8, and TNF-α was unchanged (Fig. 4 and Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Effects of SB203580 and U0126 on intracellular IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-8, IL-1ra, and TNF-α production by SAC-stimulated monocytesa

| Treatment | % of cytokine-positive CD14+-gated monocytesb

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1α | IL-1β | IL-8 | IL-1ra | TNF-α | |

| RPMI | 2 | 0 | 12 | 2 | 0 |

| SAC | 37 | 77 | 70 | 21 | 78 |

| SAC + SB203580 | 54 | 89 | 39 | 15 | 92 |

| SAC + U0126 | 27 | 74 | 74 | 26 | 81 |

| SAC + SB203580 + U0126 | 18 | 68 | 71 | 22 | 87 |

a Purified human monocytes (106/ml) were cultured for 18 h at 37°C without or with SAC (100 μg/ml) and treated with 5 μM SB203580, with 10 μM U0126, or with a mixture of SB203580 and U0126. Intracellular cytokine production was detected using specific anti-cytokine-PE or anti-cytokine-APC MAbs. An isotypic control was used as a negative control. Monocytes were gated using either anti-CD14-FITC or anti-CD14-PE MAbs. At least 5,000 CD14+ events were acquired for intracellular cytokine analysis.

b Compared to isotypic negative controls. Results are those from one representative experiment out of three performed with cells from different donors.

FIG. 4.

Effects of kinase inhibitors on intracellular IL-1α, IL-1β, and TNF-α production by SAC-stimulated monocytes. Purified human monocytes (106/ml) were first treated with SB203580 (5 μM), U0126 (10 μM), or a mixture of both inhibitors and then cultured either in the absence (RPMI) or in the presence of SAC (100 μg/106/ml). Intracellular cytokine production was assessed using specific anticytokine fluorescent MAbs. An isotypic control was used as negative control. Monocytes were gated using fluorescent anti-CD14 MAbs. At least 5,000 CD14+ events were acquired for intracellular cytokine analysis. Results are presented as representative dot plots. Reported numbers in each quadrant represented the percentage of cells that are positive compared to isotypic negative controls. Results are those from one representative experiment out of four performed with cells from different donors.

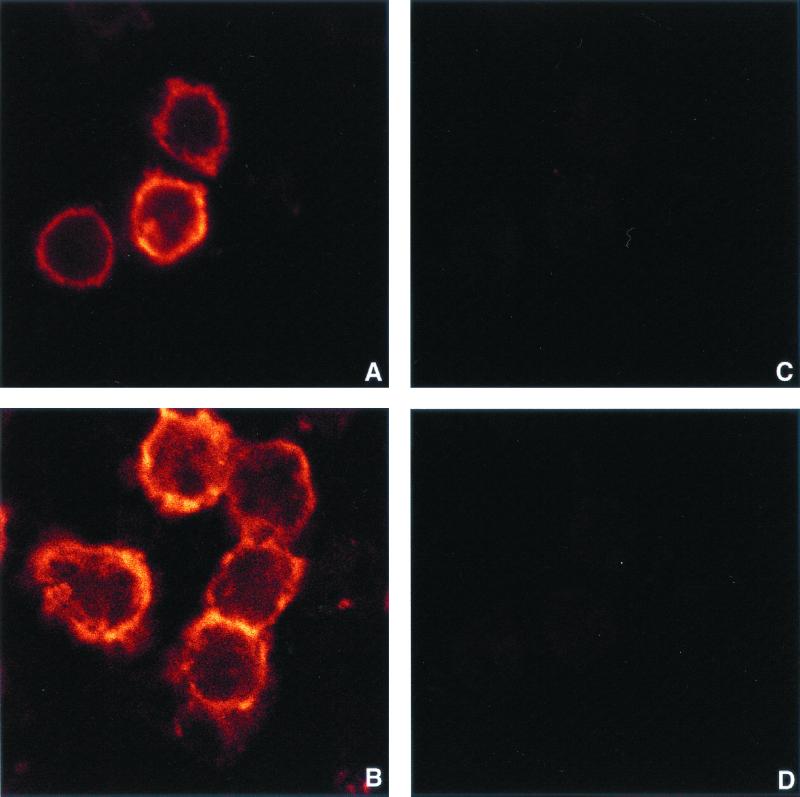

CD14 internalization in SAC-stimulated monocytes.

Several studies suggest that CD14 may also be the receptor for the cell wall component of gram-positive bacteria (26), and it has been reported that S. aureus contains molecules that bind to CD14 and induce a cellular response (30). According to our results, the CD14 molecule is not internalized following SAC stimulation (Fig. 5A and B). Treatment of the SAC-stimulated cells with 0.02% proteinase K abrogated APC-anti-CD14 labeling on monocytes (Fig. 5C and D). Moreover, we did not find any intracellular PE-anti-CD14 staining in monocytes, which indicates that CD14 internalization did not occur (Fig. 5C and D).

FIG. 5.

Lack of CD14 internalization in SAC-stimulated monocytes viewed by laser confocal microscopy. mCD14 (A and B) and intracellular CD14 (C and D) were detected by staining unstimulated monocytes (A and C) and monocytes stimulated with SAC (100 μg/106/ml) (B and D) with MAbs as described in Materials and Methods. Cells were then treated with proteinase K (C and D) to remove mCD14, fixed, and mounted on slides. For all confocal images presented, acquisition parameters were kept constant. Results are those from one representative experiment out of three performed with cells from different donors.

DISCUSSION

Monocytes/macrophages are thought to be an essential target for gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. They are involved in adaptive immunity activation, as they are the main source of inflammatory cytokines (1, 3, 4, 17, 19, 20, 27, 38). The LPS component of the bacterial cell wall is the main pathogenic factor implicated in the clinical syndrome of septic shock. Several lines of evidence indicate that the primary target of LPS on monocytes/macrophages is the mCD14 molecule, which triggers, together with TLRs including the receptor-associated adapter proteins (MyD88), intracellular signaling pathways leading to cytokine production (28, 33, 37, 58, 59). Several studies have demonstrated that different components of gram-positive bacteria also interact with the CD14 molecule (16, 30, 34, 42, 55). By using the murine macrophage RAW264,7 cell line or differentiated human THP-1 cell line, Gupta et al. demonstrated that whole bacteria activated CREB/ATF and AP-1 transcription factors similarly to PGN (23). However, the role of the CD14 molecule during cell activation induced by gram-positive or gram-negative bacteria is still controversial (27, 30, 42, 54, 55, 62). Using different cell lines, it has been demonstrated that mammalian TLRs (members of the IL-1 receptor [IL-1R] family) are involved in the activation of macrophages by both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria (58, 59, 61). Schwandner et al. (43) identified an intracellular domain of TLR2 (TLR2 1-720) expressed by human embryonic kidney HEK293 cells as a signal transducer for both soluble PGN- and LTA-induced stimulation. Coexpression of CD14 with TLR2 led to a very slight increase in PGN cellular activation, which was not found upon LTA stimulation (43). As animals lacking TLR4 do not respond to LPS, it has been proposed that TLR4 controls the innate response to gram-negative bacteria (40, 50). Several studies suggest that TLR2 may also transmit LPS cell signals (58). It was suggested that the CD14 molecule recruits LPS to TLR proteins, thereby facilitating optimal signal transduction (35). Flo et al. using TLR2- or CD14-transfected cells, demonstrated that LPS-stimulated CHO-TLR2 cells could produce IL-6 in the absence of CD14 and that anti-TLR2 MAbs did not inhibit IL-6 production by LPS-stimulated CHO-CD14 cells (16). However, they have shown that TLR2 is not required for Salmonella enterica serovar Minnesota LPS-induced TNF-α production in human monocytes (16), whereas Brightbill et al. showed that anti-TLR2 MAbs could inhibit IL-12 production by human monocytes stimulated with LPS from S. enterica serovar Typhosa (6). Thieblemont et al. reported recently that LPS aggregates are internalized and then delivered to the Golgi apparatus (48). Internalization of monomeric LPS occurred after its interaction with mCD14 without accompanying LPS during endocytic movement. In contrast, aggregates of LPS were internalized in association with mCD14 (53). Whether LPS interacts with TLR4 before or after transport to the Golgi apparatus remains to be demonstrated. It is noteworthy that TLR receptors, as IL-1R family proteins, trigger a cascade that includes MAP kinase pathways and translocation of NF-κB factor (36, 58, 59). Taken together, these data suggest that gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria may share with the IL-1R family a similar cascade of intracellular events leading to cytokine production, despite the fact that cellular activation is triggered, depending on the bacterial species, via two different TLRs (i.e., TLR2 and TLR4). To address this issue, we compared the intracellular events triggered by bacterial LPS and heat-inactivated S. aureus. We observed that the blocking of the p38 activation pathway decreased cytokine gene transcription and/or mRNA stability, dramatically affected synthesis of IL-1α and IL-1ra, and decreased TNF-α production upon LPS stimulation. Production of IL-1β and IL-8 was unaltered. Blocking the ERK pathway inhibited IL-1α and IL-1ra production, decreased IL-1β production, but did not affect TNF-α production. When both inhibitors were present, production of all tested cytokines except for IL-8 was abrogated. Similar experiments performed in the presence of SAC demonstrated that the two inhibitors, whether alone or combined, did not alter cytokine production except for the inhibition of IL-1α which was observed in the presence of ERK inhibitor or both inhibitors. It is of note that almost all cells that produced TNF-α also produced IL-1β, whereas only those producing high amounts of TNF-α were also stained with anti-IL-1α antibodies. This observation is in agreement with previous data indicating that the intracellular signaling pathways leading to IL-1α and IL-1β production are not similar (2, 18). An important observation is that the intracellular events leading to TNF-α production are different under LPS or SAC stimulation, suggesting that gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria may trigger TNF-α synthesis via distinct pathways. Despite the fact that TNF-α production by LPS-stimulated cells is dependent on NF-κB translocation, we have previously shown that addition of human growth hormone, which blocks NF-κB translocation and TNF-α production upon LPS stimulation, does not alter these two phenomena induced by phorbol myristate acetate-stimulated monocytes (24). These results indicate that TNF-α production, which has been implicated as a critical step in septic shock, may be triggered through several intracellular pathways. This finding must be taken into account in therapeutic strategies.

Several studies indicate that the interaction between LPS or gram-positive bacterial components and the CD14 molecule expressed on monocytes is a prerequisite to initiation of the early cascade of signaling events involved in cytokine synthesis (7, 20, 22, 28, 31, 34, 43). However, previous data suggest that other CD14-independent mechanisms may trigger cell activation (26, 33, 42, 51). Several lines of evidence suggest that after binding to mCD14, LPS is internalized as CD14-LPS complexes and may initiate intracellular signaling leading to a cellular response (48). The internalization process may induce at least three different intracellular signaling pathways: activation of the TLR families triggering activation of MAP kinase pathways and transcription of NF-κB, association with lipid-linked signal transduction molecules, and association with various heterotrimeric G proteins (44, 47, 58). In the present study, we first investigated if LPS and SAC trigger CD14 internalization to induce intracellular signaling. According to our FACS analysis, CD14 internalization was detectable when monocytes were cultured in the presence of LPS. This result was further investigated using laser confocal microscopy imaging. We observed that SAC stimulation did not trigger CD14 internalization, whereas CD14 localized only intracellularly in LPS-stimulated cells. Pretreatment of the cells with kinase inhibitors did not affect CD14 internalization.

Altogether, our data suggested that gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria do not trigger monocyte activation through similar pathways. LPS but not SAC used CD14 internalization to induce cellular activation, resulting in p38 MAP kinase and ERK kinase activation pathways. These findings are in accordance with recent studies demonstrating that different TLR proteins triggering by gram-positive and gram-negative components mediate cellular activation (46). Dziarski et al. demonstrated that PGN strongly activates ERK1 and ERK2 but weakly activates p38 in murine macrophages (14), suggesting that TLR2 signaling does not involve p38 MAP kinase signaling pathways. Our results suggested that although specific TLRs are involved in cellular activation by gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria, they do not induce similar pathways of intracellular signaling.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by INSERM, Université Pierre et Marie-Curie, Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (ARC no. 9273), and SIDACTION. Lila Rabehi is a recipient of a grant from SIDACTION.

We thank Michel Paing and Pierre Kitmatcher for their help with artwork. We also acknowledge the help of the staff of the transfusion center at Broussais Hospital, Paris, France.

REFERENCES

- 1.Astiz M, Saha D, Lustbader D, Lin R, Rackow E. Monocyte response to bacterial toxins, expression of cell surface receptors, and release of anti-inflammatory cytokines during sepsis. J Lab Clin Med. 1996;128:594–600. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(96)90132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auron P E, Webb A C. Interleukin-1: a gene expression system regulated at multiple levels. Eur Cytokine Netw. 1994;5:573–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beaty C D, Franklin T L, Uchara Y, Wilson C B. Lipopolysaccharide-induced cytokine production in human monocytes: role of tyrosine phosphorylation in transmembrane signal transduction. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:1278–1284. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blumenstein M, Boekstegers P, Fraunberger P, Andreesen R, Ziegler-Heitbrock H W, Fingerle-Rowson G. Cytokine production precedes the expansion of CD14+CD16+ monocytes in human sepsis: a case report of a patient with self-induced septicemia. Shock. 1997;8:73–75. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199707000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bohuslav J, Kravchenko V V, Parry G C N, Erlich J H, Gerondakis S, Mackman N, Ulevitch R J. Regulation of an essential innate immune response by the p50 subunit of NF-κB. J Clin Investig. 1998;102:1645–1652. doi: 10.1172/JCI3877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brightbill H D, Libraty D H, Krutzik S R, Yang R B, Belisle J T, Bleharski J R, Maitland M, Norgard M W, Plevy S E, Smale S T, Brennan P J, Bloom B R, Godowski P J, Modlin R L. Host defense mechanisms triggered by microbial lipoproteins through toll-like receptors. Science. 1999;285:732–736. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5428.732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chu A J, Prasad J K. Antagonism by IL-4 and IL-10 of endotoxin-induced tissue factor activation in monocytic THP-1 cells: activating role of CD14 ligation. J Surg Res. 1998;80:80–87. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1998.5346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coso O A, Chiariello M, Yu J-C, Teramoto H, Crespo P, Xu N, Miki T, Gutkind S. The small GTP-binding proteins Racl and Cdc42 regulate the activity of the JNK/SAPK signaling pathway. Cell. 1995;81:1137–1146. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crowley M T, Harmer S L, DeFranco A L. Activation-induced association of a 145kDa tyrosine-phosphorylated protein with Shc and Syk in B lymphocytes and macrophages. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:1145–1152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeFranco A L, Crowley M T, Finn A, Hambleton J, Weinstein S L. The role of tyrosine kinases and map kinases in LPS-induced signaling. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1998;397:119–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delude R, Yoshimura A, Ingalls R R, Golenbock D. Construction of a lipoposaccharide reporter cell line and its use in identifying mutants defective in endotoxin, but not TNF-alpha, signal transduction. J Immunol. 1998;161:3001–3009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Delude R L, Savedra R, Jr, Yamamoto S, Golenbock D T. Use of CD14 transfected cells to study LPS-antagonist action. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1995;392:487–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ding A, Thieblemont N, Zhu J, Jin F, Zhang J, Wright S. Secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor interferes with uptake of lipopolysaccharide by macrophages. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4485–4489. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.9.4485-4489.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dziarski R, Jin Y, Gupta D. Differential activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) 1, ERK2, p38, and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase mitogen-activated protein kinases by bacterial peptidoglycan. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:777–785. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.4.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Escourt C, Rousseau Y, Sadeghi H M, Thièblemont N, Carreno M P, Weiss L, Haeffner-Cavaillon N. Flow-cytometric assessment of in vivo cytokine-producing monocyte in HIV-infected patients. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1997;83:60–67. doi: 10.1006/clin.1996.4323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flo T H, Halaas O, Lien E, Ryan L, Teti G, Golenbock D T, Sundan A, Espevik T. Human Toll-like receptor 2 mediates monocyte activation by Listeria monocytogenes, but not by group B streptococci or lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 2000;164:2064–2069. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foey A D, Parry S L, Williams L M, Feldmannn M, Foxwell B M, Brennan F M. Regulation of monocyte IL-10 synthesis by endogenous IL-1 and TNF-alpha: role of the p38 and p42/44 mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Immunol. 1998;160:920–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Furutani Y. Molecular studies on interleukin-1α. Eur Cytokine Netw. 1994;5:533–538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geppert T D, Whitehurst C E, Thompson P, Beutler B. Lipopolysaccharide signals activation of tumor necrosis factor biosynthesis through the Ras/Raf-1/MEK/MAPK pathway. Mol Med. 1994;1:93–103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giambartolomei G H, Dennis V A, Lasater B L, Philipp M T. Induction of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines by Borrelia burgdorferi lipoproteins in monocytes is mediated by CD14. Infect Immun. 1999;67:140–147. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.1.140-147.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilman N. Ribonuclease protection assay, P. 471–478. In F. M. Ausubel, H. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl (ed.), Current protocols in molecular biology. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta D, Kirkland T N, Viriyakosol S, Dziarski R. CD14 is a cell-activating receptor for bacterial peptidoglycan. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23310–23316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gupta D, Wang Q, Vinson C, Dziarski R. Bacterial peptoglycan induces CD14-dependent activation of transcription factors CREB/ATF and AP-1. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:14012–14020. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.14012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haeffner A, Thieblemont N, Déas O, Marelli O, Charpentier B, Senik A, Wright S D, Haeffner-Cavaillon N, Hirsch F. Inhibitory effect of growth hormone on TNF-α secretion and nuclear factor-κB translocation in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human monocytes. J Immunol. 1997;158:1310–1314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han J, Lee J D, Bibbs L, Ulevitch R J. A MAP kinase targeted by endotoxin and hyperosmolarity in mammalian cells. Science. 1994;265:808–811. doi: 10.1126/science.7914033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haziot A, Hijiya N, Schultz K, Zhang F, Gangloff S C, Goyert S M. CD14 plays no major role in shock induced by Staphylococcus aureus but down-regulates TNF-α production. J Immunol. 1999;162:4801–4805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heumann D, Barras C, Severin A, Glauser M P, Tomasz A. Gram-positive cell walls stimulate synthesis of tumor necrosis factor alpha and interleukin-6 by human monocytes. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2715–2721. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.7.2715-2721.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kirschning C J, Wesche H, Merrill Ayres T, Rothe M. Human toll-like receptor 2 confers responsiveness to bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2091–2097. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.11.2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kitchens R L, Munford R S. CD14-dependent internalization of bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is strongly influenced by LPS aggregation but not by cellular responses to LPS. J Immunol. 1998;160:1920–1928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kusunoki T, Hailman E, Juan T S, Lichenstein H S, Wright S D. Molecules from Staphylococcus aureus that bind CD14 and stimulate innate immune responses. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1673–1682. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.6.1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kyriakis J M, Banerjee P, Nikolakaki E, Dai T, Rubie E A, Ahmad M F, Avruch J, Woodgett J R. The stress-activated subfamily of c-jun kinases. Nature. 1994;369:156–160. doi: 10.1038/369156a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee J C, Laydon J T, McDonnell P C, Gallagher T F, Kumar S, Green D, McNulty D, Blumenthal M J, Heys J R, Landvatter S W, Strickler J E, McLaughlin M M, Siemens I R, Fisher S M, Livi G P, White J R, Adams J L, Young P R. A protein kinase involved in the regulation of inflammatory cytokine biosynthesis. Nature. 1994;372:739–746. doi: 10.1038/372739a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Means T K, Wang S, Lien E, Yoshimura A, Golenbock D T, Fenton M J. Human toll-like receptors mediate cellular activation by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol. 1999;163:3920–3927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Medvedev A E, Flo T, Ingalls R R, Golenbock D T, Teti G, Vogel S N, Espevik T. Involvement of CD14 and complement receptors CR3 and CR4 in nuclear factor-kappaB activation and TNF production induced by lipopolysaccharide and group B streptococcal cell walls. J Immunol. 1998;160:4535–4542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Modlin R L, Brightbill H D, Godowski P J. The toll of innate immunity on microbial pathogens. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1834–1835. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906103402312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muzio M, Natoli G, Saccani S, Levrero M, Mantovani A. The human toll signaling pathway: divergence of nuclear factor kappaB and JNK/SAPK activation upstream of tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6) J Exp Med. 1998;187:2097–2101. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.12.2097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nagata Y, Takahashi N, Davis R J, Todokoro K. Activation of p38 MAP kinase and JNK but not ERK is required for erythropoietin-induced erythroid differentiation. Blood. 1998;92:1859–1869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Netea M G, Kullberg B J, van der Meer J M W. Lipopolysaccharide-induced production of tumour necrosis factor and interleukin-1 is differentially regulated at the receptor level: the role of CD14-dependent and CD14-independent pathways. Immunology. 1998;94:340–344. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00532.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nick J A, Avdi N J, Young S K, Lehman L A, McDonald P P, Courtney Frasch S, Billstrom M A, Henson P M, Johnson G L, Scott Worthen G. Selective activation and functional significance of p38α mitogen-activated protein kinase in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated neutrophils. J Clin Investig. 1999;103:851–858. doi: 10.1172/JCI5257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I, Liu M Y, Huffel C V, Du X, Birdwell D, Alejos E, Silva M, Galanos C, Freudenberg M, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Layton B, Beutler B. Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: mutations in T1r4 gene. Science. 1998;282:2085–2088. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scherle P A, Jones E A, Favata M F, Daulerio A J, Covington M B, Nurnberg S A, Magolda R L, Trzaskos J M. Inhibition of MAP kinase prevents cytokine and prostaglandin E2 production in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated monocytes. J Immunol. 1998;161:5681–5686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schromm A B, Brandenburg K, Rieschel E T, Flad H D, Caroll S F, Seydel U. Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein mediates CD14-independent intercalation of lipopolysaccharide into phospholipid membranes. FEBS Lett. 1996;399:267–271. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01338-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schwandner R, Dziarski R, Wesche H, Rothe M, Kirschning C. Peptoglycan- and lipoteichoic acid-induced cell activation is mediated by toll-like receptor 2. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17406–17409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Solomon K R, Kurt-Jones E A, Saladino R A, Stack A M, Dunn I F, Ferretti M, Golenbock D, Fleisher G R, Finberg R W. Heterometric G proteins physically associated with the lipopolysaccharide receptor CD14 modulate both in vivo and in vitro responses to lipopolysaccharide. J Clin Investig. 1998;102:2019–2027. doi: 10.1172/JCI4317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stefanova I, Corcoran M L, Horak E V, Wahl L M, Bolen J B, Horak I D. Lipopolysaccharide induces activation of CD14-associated protein tyrosine kinase p53/56lyn J. Biol Chem. 1993;268:20725–20728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Takeuchi O, Hoshino K, Kawai T, Sanjo H, Takada H, Ogawa T, Takeda K, Akira S. Differential roles of TLR2 and TLR4 in recognition of gram-negative and gram-positive bacterial cell wall components. Immunity. 1999;11:443–451. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80119-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thieblemont N, Thieringer R, Wright S D. Innate immune recognition of bacterial lipopolysaccharide: dependence. Immunity. 1998;8:771–777. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80582-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thieblemont N, Wright S D. Transport of bacterial lipopolysaccharide to the Golgi apparatus. J Exp Med. 1999;190:523–534. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.4.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tucker S B, Pierre R V, Jordon R E. Rapid identification of monocytes in a mixed mononuclear cell preparation. J Immunol Methods. 1977;14:267–269. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(77)90137-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ulevitch R J. Toll gated for pathogen selection. Nature. 1999;401:755–756. doi: 10.1038/44490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Underhill D M, Ozinsky A, Hajjar A M, Stevens A, Wilson C B, Bassetti M, Aderem A. The toll-like receptor 2 is recruited to macrophage phagosomes and discriminates between pathogens. Nature. 1999;401:811–815. doi: 10.1038/44605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vanden Berghe W, Plaisance S, Boone E, De Bosscher K, Schmitz M L, Fiers W, Haegeman G. p38 and extracellular signal-regulated kinase mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways are required for nuclear factor-kappaB 65 transactivation mediated by tumor necrosis factor. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:3285–3290. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.6.3285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vasselon T, Hailman E, Thieringer R, Detmers P A. Internalization of monomeric lipopolysaccharide occurs after transfer out of cell surface CD14. J Exp Med. 1999;190:509–521. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.4.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weidemann B, Brade H, Rietschel E T, Dziarski R, Bazil V, Kusumoto S, Flad H D, Ulmer A J. Soluble peptidoglycan-induced monokine production can be blocked by anti-CD14 monoclonal antibodies and by lipid A partial structures. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4709–4715. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.4709-4715.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weidemann B, Schletter J, Dziarski R, Kusumoto S, Stelter F, Rietschel E T, Flad H D, Ulmer A J. Specific binding of soluble peptidoglycan and muramyldipeptide to CD14 on human monocytes. Infect Immun. 1997;65:858–864. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.3.858-864.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weiss L, Haeffner-Cavaillon N, Laude M, Cavaillon J M, Kazatchkine M D. Human T cells and interleukin-4 inhibit the release of interleukin 1 induced by lipopolysaccharide in serum-free cultures of autologous monocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1989;19:1347–1350. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830190731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yamamoto H, Hanada K, Nishijima M. Involvement of diacylglycerol production in activation of nuclear factor κB by a CD14-mediated lipopolysaccharide stimulus. Biochem J. 1997;325:223–228. doi: 10.1042/bj3250223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang R-B, Mark M R, Gray A, Huang A, Xie M H, Zhang M, Goddard A, Wood W I, Gurney A L, Godowski P J. Toll-like receptor-2 mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced cellular signalling. Nature. 1998;395:284–288. doi: 10.1038/26239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang R B, Mark M R, Gurney A L, Godowski P J. Signaling events induced by lipopolysaccharide-activated toll-like receptor 2. J Immunol. 1999;163:639–643. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yao J, Mackman N, Edgington T S, Fan S T. Lipopoplysaccharide induction of the tumor necrosis factor-alpha promoter in human monocytic cells. Regulation by Egr-1, c-jun, and NF-kappaB transcription factors. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17795–17801. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yoshimura A, Lien E, Ingalls R R, Tuomanen E, Dziarski R, Golenbock D. Cutting edge: recognition of Gram-positive bacterial cell wall components by the innate immune system occurs via Toll-like receptor 2. J Immunol. 1999;163:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ziegler-Heitbrock H W. Heterogeneity of human blood monocytes: the CD14+CD16+subpopulation. Immunol Today. 1996;17:424–428. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)10029-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]