Abstract

Live attenuated Salmonella strains that express a foreign antigen are promising oral vaccine candidates. Numerous genetic modifications have been empirically tested, but their effects on immunogenicity are difficult to interpret since important in vivo properties of recombinant Salmonella strains such as antigen expression and localization are incompletely characterized and the crucial early inductive events of an immune response to the foreign antigen are not fully understood. Here, methods were developed to directly localize and quantitate the in situ expression of an ovalbumin model antigen in recombinant Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium using two-color flow cytometry and confocal microscopy. In parallel, the in vivo activation, blast formation, and division of ovalbumin-specific CD4+ T cells were followed using a well-characterized transgenic T-cell receptor mouse model. This combined approach revealed a biphasic induction of ovalbumin-specific T cells in the Peyer's patches that followed the local ovalbumin expression of orally administered recombinant Salmonella cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Interestingly, intact Salmonella cells and cognate T cells seemed to remain in separate tissue compartments throughout induction, suggesting a transport of killed Salmonella cells from the colonized subepithelial dome area to the interfollicular inductive sites. The findings of this study will help to rationally optimize recombinant Salmonella strains as efficacious live antigen carriers for oral vaccination.

Vaccination is an effective approach to control infectious diseases, but for many pathogens efficacious vaccines have not yet been developed. Live attenuated Salmonella strains that express a foreign antigen can be administered via the easy, safe, and well-accepted oral route and can induce strong mucosal and systemic immune responses to the foreign antigen that confer protective immunity against numerous pathogens in several animal models (3, 24, 41). Despite encouraging preclinical results, the few clinical trials with live recombinant Salmonella strains showed weak to undetectable human immune responses to the foreign antigens, indicating the need for further optimization.

In general, antigen localization, dose, and timing are key parameters for the optimization of an immune response (47). Indeed, numerous genetic modifications of recombinant Salmonella, including attenuating mutations and antigen expression systems that are likely to influence in vivo localization and antigen expression have been shown to result in altered immune responses (10–12, 30, 31, 44, 45). However, the results are difficult to interpret since the in vivo localization and antigen expression levels of the various Salmonella strains are still largely unknown. Moreover, the crucial early events of the induction of an immune response have not been characterized in detail because of technical problems due to the low precursor frequency of antigen-specific immune cells. As a result of this incomplete understanding, the optimization of live recombinant Salmonella strains has remained largely empirical.

Here, novel methods were used to localize and quantitate the in vivo antigen expression of an orally administered live recombinant Salmonella strain. In parallel, the early inductive events of an antigen-specific CD4+ T-cell response were followed using a well-characterized transgenic T-cell receptor (tgTCR) mouse model (37). The results of this combined approach show how vaccine properties in vivo relate to the induction of a cellular immune response and suggest several options for the rational optimization of these promising oral vaccines.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of recombinant Salmonella strains.

An ovalbumin peptide (amino acids 319 to 343) that is recognized by DO11.10 T cells (33) was fused to the C terminus of a bright variant of green fluorescent protein (GFP) (7) and expressed from the Ptac promoter in the medium-copy-number plasmid pKK223-3 (Pharmacia), yielding pGFP_OVA (Bumann, unpublished data). As a control, a similar plasmid encoding GFP without fused ovalbumin was also constructed (pGFP). Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium aroA strain SL3261 (15) was electrotransformed with either pGFP or pGFP_OVA.

SDS-PAGE, immunoblotting, and quantification of expression in vitro.

Samples of late-log-phase cultures of SL3261(pGFP) and SL3261(pGFP_OVA) were applied to standard sodium dodecyl sulfate–12% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–12% PAGE) gels, electroblotted onto nitrocellulose, and stained with polyclonal rabbit antibodies to GFP or ovalbumin followed by a peroxidase-coupled antibody to rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) and chemoluminescence detection. All antibodies were preadsorbed with SL3261 lysate to reduce nonspecific binding.

To estimate the expression levels of GFP and GFP_OVA, SL3261, SL3261(pGFP), and SL3261(pGFP_OVA) were grown to the mid-logarithmic growth phase and lysed by sonification. The lysate was centrifuged and filtered through a 0.2-μm-pore-size filter to remove residual intact bacteria and absorbance spectra were measured in the range of 400 to 600 nm. The spectra were normalized for lysate protein content as determined with the bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce) and the spectrum of SL3261 was subtracted from the other spectra for background correction. The peak absorption at 485 nm was used to calculate the amount of GFP or GFP_OVA based on an extinction coefficient of 55,000 cm−1 M−1 (Living Colors™ red fluorescent protein, October 1999, p. 1; Clontech, Palo Alto, Calif.).

Mice, adoptive transfer, and immunization.

BALB/c mice and DO11.10 mice (33) were bred in the Bundesamt für Gesundheitlichen Verbraucherschutz und Veterinärmedizin, Berlin, Germany, and were kept under specific-pathogen-free conditions in full accordance with German guidelines for animal care. All experiments were approved by the local Animal Welfare Committee.

Ammonium chloride-treated splenocytes from 8- to 12-week-old female DO11.10 × BALB/c crosses were transferred by tail vein injection into sex- and age-matched BALB/c recipient mice (4 × 106 tgTCR CD4+ T cells per recipient mouse), and mice were immunized 1 day later. For oral immunization, an overnight culture of SL3261(pGFP) or SL3261(pGFP_OVA) cells was diluted 1:8 in fresh Luria-Bertani (LB) medium and grown to the late logarithmic growth phase at 37°C and 200 rpm. The bacteria were harvested by centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 5 min, washed in LB medium containing 3% NaHCO3, and resuspended in the same medium to 1.2 × 1010 to 4 × 1011 CFU ml−1, and 100 μl of this suspension was intragastrically administered to mice with a round-tip stainless steel needle.

For immunization with inactivated bacteria, SL3261(pGFP_OVA) cells were grown to the late logarithmic phase and heated for 5 min to 80°C or for 2 h to 60°C. Alternatively, live bacteria were treated with 2% formalin in phosphate-buffered saline for 1 h. After inactivation, the bacterial suspensions were washed, resuspended, and administered as described for live Salmonella cells.

Recovery of bacteria from colonized mice.

At various time intervals postimmunization, mice were anesthetized and killed. The spleens, mesenteric lymph nodes, and Peyer's patches were prepared. Single-cell suspensions of the various organs were treated with 0.1% Triton X-100 and plated on LB plates containing 90 μg of streptomycin ml−1 or 90 μg of streptomycin ml−1 plus 100 μg of ampicillin ml−1.

Immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry.

To localize Salmonella cells that expressed GFP_OVA with confocal microscopy, cryosections (20 μm) of Peyer's patches were fixed with 2% formalin in phosphate-buffered saline and stained with a polyclonal rabbit antibody to Salmonella lipopolysaccharide (LPS) serogroup B (Sifin) and an Alexa546-conjugated polyclonal antibody to rabbit IgG (Molecular Probes). Stack projections (15 μm) of optical sections (0.2 to 0.4 μm) are shown.

To colocalize Salmonella cells and ovalbumin-specific T-helper cells, cryosections were fixed with ethanol, stained with biotinylated monoclonal antibodies KJ1-26 (14) and ABC (Vector) using the substrate 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (AEC), blocked with 0.4% peroxide, and stained with a rabbit polyclonal antibody to Salmonella LPS serogroup B and a peroxidase-coupled polyclonal antibody to rabbit IgG using the substrate 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) in the presence of nickel.

Flow cytometry.

To measure bacterial antigen expression, SL3261(pGFP_OVA) cultures or Triton X-100-treated tissue samples were analyzed for green and orange fluorescence (channels FL-1 [515 to 545 nm] and FL-2 [563 to 607 nm], respectively) without compensation for spectral overlap as described previously (Bumann, unpublished data) using a FACScan flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). Salmonella cells expressing GFP were identified based on their typical emission ratios (FL-2/FL-1), which were about 1 order of magnitude smaller than those of autofluorescent tissue fragments.

To measure ovalbumin-specific T-helper-cell activation, single-cell suspensions of Peyer's patches, mesenteric lymph nodes, and spleens were stained with biotinylated anti-tgTCR clonotype antibody KJ1-26 (14), anti-CD4–fluorescein, anti-CD69–phycoerythrin, and anti-B220–allophycocyanin, followed by streptavidin-FarRed (Gibco), and analyzed with a Calibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). CD4+ tgTCR+ B220− lymphocytes were analyzed for their forward scatter and CD69 expression. Alternatively, cells were stained with biotinylated KJ1-26, anti-CD45RB–fluorescein, anti-CD4–phycoerythrin, and anti-B220–allophycocyanin, followed by streptavidin-FarRed (Gibco), and CD4+ tgTCR+ B220− lymphocytes were analyzed for CD45RB expression. To analyze the in vivo division of the transgenic T cells in the chimeric mice, the cells were labeled prior to their adoptive transfer with 0.5 μM carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) (Molecular Probes) for 10 min at 37°C as previously described (36).

RESULTS

Construction and characterization of SL3261(pGFP_OVA).

To follow the interaction of Salmonella cells and the adaptive immune response of the host, GFP was fused to a minimal part of ovalbumin (amino acids 319 to 343) consisting of a dominant I-Ad-restricted T-cell epitope and the four adjacent N- and C-terminal amino acid residues that might influence antigen processing for class II presentation (34). The fusion protein GFP_OVA was expressed from the Ptac promoter (pGFP_OVA). As a control, an analogous construct was made for the expression of GFP alone without the fused ovalbumin epitope (pGFP).

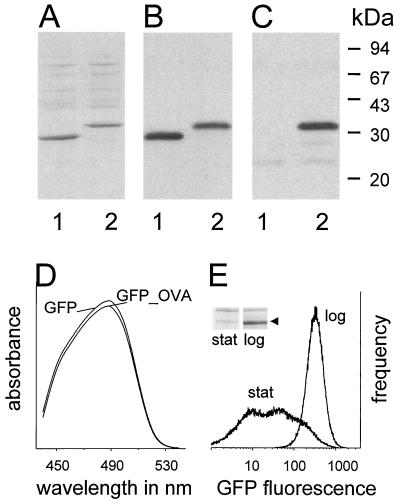

The well-characterized attenuated strain S. enterica serovar Typhimurium SL3261 carrying aroA (15) was used as a prototype Salmonella carrier. The transformants SL3261(pGFP) and SL3261(pGFP_OVA) expressed an additional protein band with the expected molecular mass (28 or 31 kDa, respectively; Fig. 1A). Both proteins were recognized by an antibody to GFP (Fig. 1B), and the fusion protein GFP_OVA was recognized by a polyclonal antibody to ovalbumin (Fig. 1C). Almost all the detectable GFP and ovalbumin was part of the intact GFP_OVA fusion protein, suggesting that the GFP fluorescence in SL3261(GFP_OVA) can be used as an estimate for the expression level of the model T-cell epitope.

FIG. 1.

In vitro characterization of Salmonella strains expressing GFP (lanes 1) or GFP_OVA (lanes 2). (A) SDS-PAGE. (B) Immunoblot with an antibody to GFP. (C) Immunoblot with an antibody to ovalbumin. (D) Absorbance spectra of Salmonella lysates. (E) Flow cytometry of SL3261(pGFP_OVA) cultures at the logarithmic (log) and stationary (stat) growth phases. The inset shows an SDS-PAGE gel of both cultures, with the arrow marking GFP_OVA. Similar data were obtained for three independent experiments.

Absorption spectra of lysates from logarithmic-phase SL3261(pGFP_OVA) and SL3261(pGFP) cultures were identical, indicating that the fusion of the ovalbumin epitope to GFP did not alter its spectroscopic properties (Fig. 1D). SL3261(pGFP) and SL3261(pGFP_OVA) expressed almost identical GFP and GFP_OVA levels of 30 ± 10 ng of protein per 106 bacteria, equivalent to 600,000 copies of the ovalbumin epitope per cell for SL3261(pGFP_OVA). Flow cytometry of logarithmic-phase cultures showed that GFP expression was high and homogeneous in all bacteria, but it was downregulated and heterogeneous in stationary-phase cultures (Fig. 1E), although the bacteria remained viable and retained the functional expression plasmid, as determined by plating with or without ampicillin selection and flow cytometry of fresh subcultures. The growth phase-dependent expression of GFP_OVA was confirmed by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1E, inset). Low GFP_OVA levels during the stationary phase could reflect a decreased promoter activity and/or an enhanced degradation of transcripts and proteins. Otherwise identical plasmids in which alternative promoters other than Ptac drive gfp_ova transcription show the opposite expression pattern, with increased GFP_OVA levels during stationary phase (Bumann, unpublished data), suggesting that promoter activities play a major role in differential regulation in SL3261(pGFP_OVA), although mRNA and protein turnover might also contribute to regulation. The downregulation of Ptac during stationary phase might be related to inefficient binding of the alternative ς-factor RpoS to the Ptac promoter and/or to the relaxation of negative supercoiling of the expression plasmid (1), which is known to diminish the Ptac promoter strength (42).

Colonization in mice and localization within Peyer's patches.

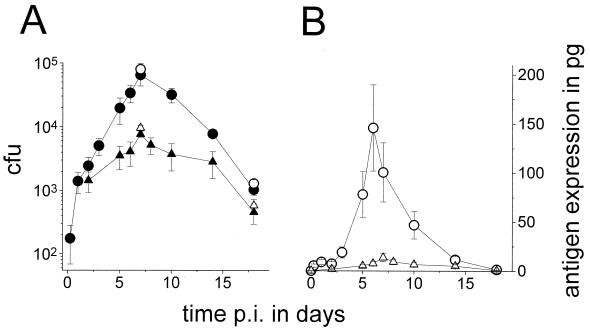

Mice were intragastrically inoculated with 4 × 1010 SL3261(pGFP_OVA) cells, and colonization was determined by plating. The few hundred clones that were present in the Peyer's patches at 6 h expanded exponentially until day 7, with a peak number of recovered CFU around 6 × 104 (Fig. 2A) followed by a decline over the next 2 weeks, which is in close agreement with previous studies using similar doses of recombinant SL3261 (11). The mesenteric lymph nodes were colonized with similar kinetics but with 10-fold-lower peak numbers (Fig. 2A), whereas the spleen was colonized by only a few hundred Salmonella cells for some mice (data not shown). Plating on medium with or without ampicillin revealed that at 7 and 18 days postimmunization more than 80% of the ex vivo clones still retained the expression plasmid (Fig. 2A). All of the plasmid-containing clones expressed large amounts of GFP in vitro, as indicated by their yellow color and flow cytometric data.

FIG. 2.

Colonization and in situ antigen expression of orally administered live SL3261(pGFP_OVA) cells. Averages and SEMs of CFU values for three mice per data point are shown. (A) Colonization of Peyer's patches (○, ●) and mesenteric lymph nodes (▵, ▴). The open symbols represent all recovered Salmonella cells, whereas the closed symbols represent Salmonella cells that retained the plasmid as determined by plating on selective medium. Similar results were obtained for three independent experiments. p.i., postimmunization. (B) Total in situ expression of GFP_OVA in the Peyer's patches (○) and mesenteric lymph nodes (▵) as determined by two-color flow cytometry (see text for description). (C) Subepithelial dome of a Peyer's patch 7 days postimmunization. Bar, 50 μm. The dotted line represents the apical border of the follicle-associated epithelium. L, intestinal lumen. (D) Enlarged micrograph of a single infected cell in the subepithelial dome 7 days postinfection. Bar, 5 μm. Similar images were obtained for 10 mice at various time points postimmunization from two independent experiments.

To visualize the localization of the recombinant Salmonella cells in colonized Peyer's patches, cryosections were stained with an antibody to Salmonella LPS and viewed by confocal microscopy. While control sections from naive mice did not stain for Salmonella LPS, Peyer's patches from colonized mice contained many LPS-positive particles with a size of about 1 μm, representing individual bacteria (Fig. 2C and D). Serial sections of mice sacrificed at various time points postimmunization showed that throughout the colonization period, most Salmonella cells localized to the subepithelial dome area, with few bacteria in the follicles and almost none in the interfollicular T-cell area. At time points later than 5 h, no Salmonella cells were detected in the intestinal lumen or in the crypts. A similar localization of recombinant Salmonella to the subepithelial dome area has been previously observed for a Salmonella PhoPc strain at a very early time point (4 h postimmunization) (16, 17).

In situ antigen expression as measured by two-color flow cytometry.

A strong background of abundant small autofluorescent particles makes it difficult to detect bacterial GFP expression in the host by one-color flow cytometry (16, 23), but two-color flow cytometry efficiently separates autofluorescence from GFP emission (Bumann, unpublished data). In this approach, the green GFP fluorescence is discriminated from the yellowish autofluorescence based on the differential spectral components that can be measured in channels FL-1 (515 to 545 nm) and FL-2 (563 to 607 nm) of the FACScan flow cytometer. Autofluorescence has a stronger orange emission component (FL-2) compared to GFP, which results in a larger FL-2/FL-1 emission ratio. A quantitative analysis of GFP expression by SL3261(pGFP_OVA) in colonized mice suggested that almost all Salmonella cells expressed GFP in situ but did so at levels that decreased about 10-fold over the first 2 days and then remained at 25,000 to 80,000 copies per bacterium (Bumann, unpublished data). This low expression level was similar to that of fully stationary in vitro cultures (Fig. 1E) and was not a consequence of plasmid loss or mutation, as more than 80% of the Salmonella cells retained the plasmid and the ability to produce large amounts of GFP_OVA in vitro throughout colonization. Instead, differential promoter activities and/or enhanced degradation of transcripts and proteins might be involved. Otherwise identical constructs in which alternative promoters other than Ptac drive gfp_ova transcription show increased in vivo GFP_OVA levels compared to the respective in vitro cultures (Bumann, unpublished data), suggesting that transcriptional regulation plays a major role in vivo, as it does in stationary in vitro cultures (see above). The gene regulation of Salmonella grown in vivo has previously been observed to resemble in vitro stationary cultures (27, 35). In addition to transcriptional regulation, stress proteases such as HtrA that are known to be induced in vivo (19, 38) might further decrease the in vivo GFP_OVA levels (see Discussion).

To determine the total in situ amount of ovalbumin peptide, the integrated GFP levels from flow cytometric profiles were multiplied by the number of CFU (Fig. 2B). After a small initial antigen peak caused by the still-elevated GFP_OVA expression level at day 1, there was a strong increase in the antigen amount until day 6, with a peak level of some 150 pg for all Peyer's patches of an individual mouse followed by a steady decline over the next 10 days. Much lower total amounts were expressed in the mesenteric lymph nodes.

Confocal microscopy of Peyer's patches showed that all detectable GFP_OVA fluorescence was confined to particles with a size of about 1 μm that were also positive for S. enterica serovar Typhimurium LPS (Fig. 2C and D). In agreement with flow cytometry, GFP_OVA expression varied widely between individual bacteria. Bacteria with both high and low expression levels occurred together in single host cells and were scattered throughout the colonized tissue with no obvious differential distribution. No green fluorescence above background was detected in mice colonized by SL3261 not expressing GFP.

Induction of ovalbumin-specific T cells.

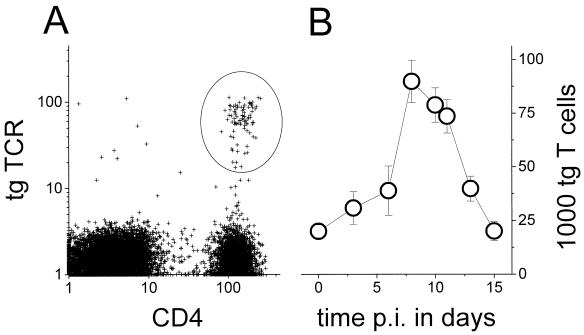

To determine the site and kinetics of induction for T cells that specifically recognize an antigen expressed by Salmonella, a well-characterized tgTCR adoptive transfer system was used (37). CD4+ T cells from DO11.10 mice that are transgenic for a major histocompatibility complex class II-restricted TCR recognizing an ovalbumin epitope (33) were transferred to syngeneic, nontransgenic BALB/c mice. In the chimeric mice, the ovalbumin-specific transgenic T cells were traced using a clonotypic monoclonal antibody (14) (Fig. 3A). One day after transfer, 0.5% ± 0.1% (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]) of the total splenic lymphocytes (B and T cells), 0.8% ± 0.2% of the mesenteric lymph node lymphocytes, and 0.2% ± 0.05% of the Peyer's patch lymphocytes in the chimeric mice were CD4+ T cells expressing the ovalbumin-specific tgTCR, whereas BALB/c control mice contained no positive cells, which was in good agreement with previous data (5, 21). The rather small transgenic population in the Peyer's patches partially reflects the small proportion of naive T cells in this compartment (32). The transgenic T-cell population declined slowly in all lymphoid organs of nonimmunized chimeric mice, with a half-life of about 2 weeks, indicating that there was a typical slow loss but no rejection.

FIG. 3.

Detection of transgenic ovalbumin-specific T cells in chimeric mice after immunization with a recombinant Salmonella strain. (A) Flow cytometry of adoptively transferred ovalbumin-specific tgTCR CD4+ T cells in Peyer's patches of a recipient 1 day after transfer. (B) Total number of ovalbumin-specific T cells in Peyer's patches after various time intervals postimmunization (p.i.) with SL3261(pGFP_OVA). Averages and SEMs of values for three to seven mice per data point from two independent experiments are shown.

After oral administration of SL3261(pGFP_OVA) cells to chimeric mice, there was a weak biphasic accumulation of ovalbumin-specific transgenic CD4+ T cells in the Peyer's patches around day 3 and from day 7 to day 12, with a transient decay around day 5. This weak pattern was observed consistently in three independent experiments and was absent in control mice colonized by SL3261(pGFP) cells, but individual variation prevented statistically significant results. To calculate the total numbers of ovalbumin-specific T cells, the concentrations were multiplied by the total number of lymphocytes in the Peyer's patches for each time point (Fig. 3B). There was a large increase of specific T cells with a peak at day 8 followed by a decline to the initial values, but the whole pattern largely followed the general accumulation of lymphocytes in the Peyer's patches during Salmonella colonization. A similar accumulation was observed in the mesenteric lymph nodes and the spleen.

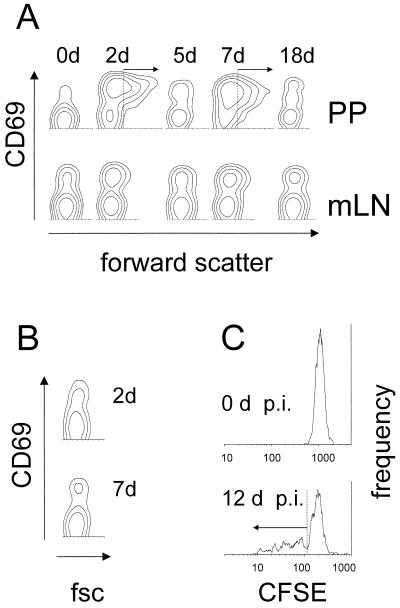

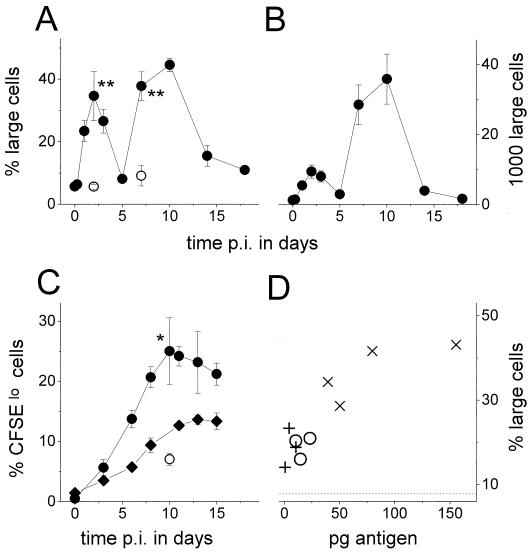

Despite their weak selective accumulation, many ovalbumin-specific T cells became activated after administration of SL3261(pGFP_OVA) cells. Within 2 days, many ovalbumin-specific T cells in the Peyer's patches upregulated the very early activation marker CD69 and became larger, as indicated by their increased forward scattering (Fig. 4A and 5A and B). A small fraction of ovalbumin-specific T cells in the mesenteric lymph nodes also became activated (Fig. 4A), whereas no activation was observed in the spleen. A second wave of strong ovalbumin-specific T-cell activation occurred in the Peyer's patches from day 7 to day 10 (Fig. 4A and 5A). Because of the large general accumulation (Fig. 3B), a greater total number of ovalbumin-specific T cells became activated during this second activation wave than during the first wave around day 2 (Fig. 5B). The second wave coincided with the maximal Salmonella colonization and antigen expression around day 7 and ceased together with the decay of in situ antigen levels (Fig. 2B). The T-cell activation was antigen specific since in mice colonized by SL3261(pGFP), ovalbumin-specific T cells were not activated in both Peyer's patches (Fig. 4B and 5A) and mesenteric lymph nodes (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Activation of ovalbumin-specific T cells after immunization with a recombinant Salmonella strain. (A) CD69 expression and forward scatter of ovalbumin-specific T cells in Peyer's patches (PP) and mesenteric lymph nodes (mLN) after oral immunization with SL3261(pGFP_OVA). Similar results were obtained for three independent experiments. d, days. (B) CD69 expression and forward scatter (fsc) of ovalbumin-specific T cells in Peyer's patches 2 and 7 days (d) after oral immunization with SL3261(pGFP). (C) Fluorescence of CFSE-labeled ovalbumin-specific T cells prior to or 12 days (d) after oral immunization (p.i.) with SL3261(pGFP_OVA).

FIG. 5.

Blast formation and in vivo division of ovalbumin-specific T cells after oral immunization with a recombinant Salmonella strain. p.i., postimmunization. (A) Fraction of large cells (gated as in Fig. 4A) among ovalbumin-specific T cells in the Peyer's patches after oral immunization with SL3261(pGFP_OVA) (●) or SL3261(pGFP) (○). Averages and SEMs of values for three to seven mice per data point are shown. The statistical significance of differences between SL3261(pGFP) and SL3261(pGFP_OVA) was analyzed with the t test (∗∗, P < 0.001). Similar results were obtained for three independent experiments. (B) Total number of large ovalbumin-specific T cells in the Peyer's patches after oral immunization with SL3261(pGFP_OVA). (C) Fraction of CFSE10 cells (gated as in Fig. 4C) among ovalbumin-specific T cells in the Peyer's patches (○, ●) and mesenteric lymph nodes (⧫) after immunization with SL3261(pGFP_OVA) (●, ⧫) or SL3261(pGFP) (○). Averages and SEMs of values for three mice per data point are shown. The statistical significance of differences between SL3261(pGFP) and SL3261(pGFP_OVA) was analyzed with the t test (∗, P < 0.05). Similar results were obtained for two independent experiments. (D) Dose-response relationship between in situ expression of GFP_OVA and the fraction of large cells (gated as in Fig. 4A) among ovalbumin-specific T cells in the Peyer's patches 7 days after oral immunization with 1.2 × 109 (+), 6 × 109 (○), or 4 × 1010 (×) SL3261(pGFP_OVA) cells. The dotted line represents background staining after immunization with 4 × 1010 SL3261(pGFP) cells. The statistical significance of differences between SL3261(pGFP) and SL3261(pGFP_OVA) was analyzed with the t test (1.2 × 109 CFU, P < 0.05; 6 × 109 CFU, P < 0.01; 4 × 1010 CFU, P < 0.001).

The occurrence of a second T-cell response about 7 to 10 days after the initial response resembled a prime-boost immunization with initially primed T cells becoming restimulated. However, among the ovalbumin-specific large T cells that were formed at day 7 in the Peyer's patches, 86 to 94% expressed high levels of CD45RB, indicating that the cells activated during the second response were mostly naive and distinct from the ones that had been initially activated.

The size increase of many ovalbumin-specific T cells during SL3261(pGFP_OVA) colonization suggested blast formation. This was confirmed by CFSE labeling of the transgenic T cells prior to their adoptive transfer. After oral administration of SL3261(pGFP_OVA) but not SL3261(pGFP) cells to chimeric mice, many ovalbumin-specific T cells in the Peyer's patches (Fig. 4C and 5C) and in the mesenteric lymph nodes (Fig. 5C) lost part of their CFSE fluorescence, indicating blast formation and in vivo division.

There was a clear dose-response relationship between the amount of antigen expressed in situ and the amplitude of the ovalbumin-specific T-cell response at day 7 (R = 0.88, P < 0.001; Fig. 5D). A minimum of about 5 pg of GFP_OVA fusion protein expressed in live Salmonella cells was sufficient to observe a significant specific T-cell activation (P < 0.05). This corresponded to an initial inoculum of 1.2 × 109 CFU, which is a rather low dose compared to what is commonly used for murine immunization studies (1 × 109 to 5 × 1010 CFU). To obtain strong responses, 4 × 1010 CFU was administered for all other experiments.

Ovalbumin-specific T-cell activation was dependent on a viable recombinant Salmonella strain, since SL3261(pGFP_OVA) cells that had been inactivated by mild heat or formalin treatments yet contained unchanged amounts of fusion protein as determined by SDS-PAGE failed to induce a detectable response at days 2 and 7 (data not shown).

Colocalization of SL3261(pGFP_OVA) and ovalbumin-specific T cells.

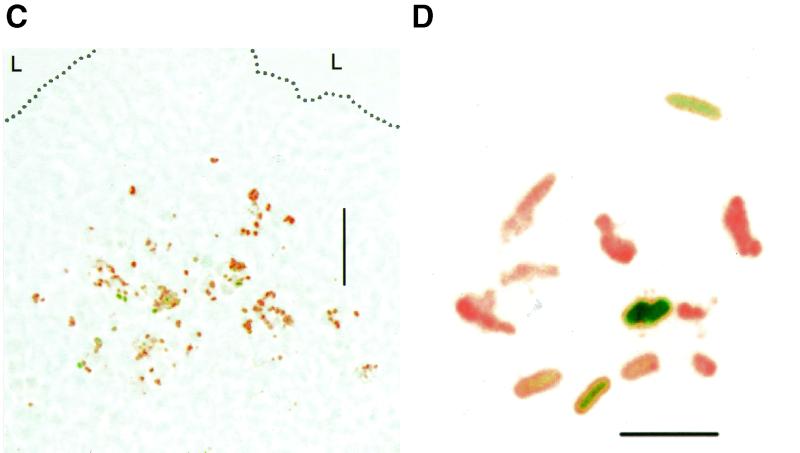

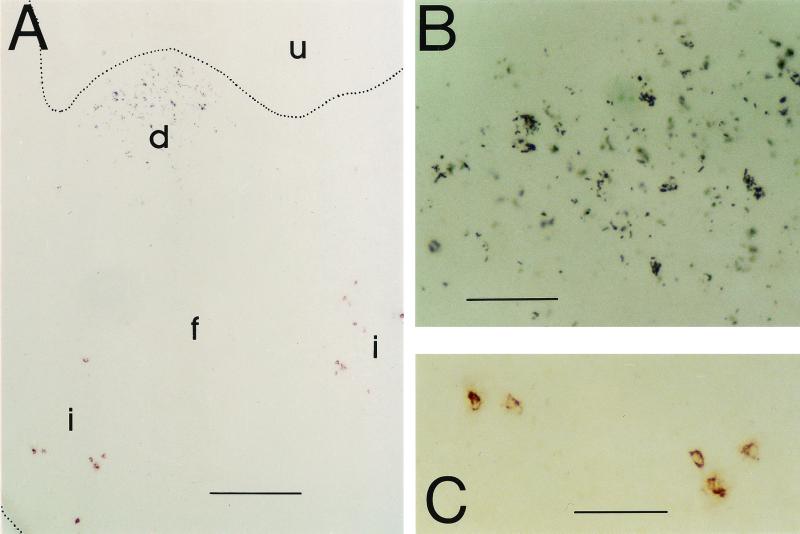

To investigate the spatial relationship between SL3261(pGFP_OVA) and antigen-specific T cells during their induction, cryosections of Peyer's patches were stained using antibodies to the tgTCR and to Salmonella LPS (Fig. 6). While Salmonella cells mostly localized to the subepithelial dome areas of the Peyer's patches throughout the colonization period, confirming the confocal data (Fig. 2C), almost all ovalbumin-specific T cells remained confined to the interfollicular T-cell areas, which were some hundreds of micrometers away from the Salmonella-colonized areas. This spatial separation of Salmonella and T cells was observed throughout the entire colonization and T-cell induction process, although only around day 7 were Salmonella and ovalbumin-specific T cells frequent enough to colocalize them on single sections. Naive chimeric mice were negative for Salmonella LPS, and BALB/c mice were negative for the tgTCR.

FIG. 6.

Colocalization of Salmonella cells (black) and ovalbumin-specific T cells (red) in the Peyer's patches 8 days after oral immunization with SL3261(pGFP_OVA). (A) Overview at low magnification. u, lumen; d, subepithelial dome; f, follicle; i, interfollicular region. Bar, 200 μm. (B) Dome area at higher magnification. Bar, 50 μm. (C) Interfollicular area at higher magnification. Bar, 50 μm.

DISCUSSION

Live attenuated Salmonella strains are promising oral vaccine carriers for heterologously expressed foreign antigens. Several parameters of such recombinant constructs are known to influence the vaccine efficacy, but optimization is still largely empirical because key properties such as antigen amount, timing, and localization as well as early events of the immune response have been incompletely characterized in vivo.

The amount of antigen that is being produced by recombinant Salmonella strains can be very different in vitro and in vivo due to complex regulatory networks (9). To measure the levels of antigen expression in situ, a model T-cell epitope was expressed as a GFP fusion protein and quantified using two-color flow cytometry. GFP fluorescence was also used to localize Salmonella cells that express the fusion protein in situ by confocal microscopy. Almost the entire protein chain of GFP is required for fluorescence (25); hence, most proteolytic fragments of GFP_OVA would escape flow cytometric detection, resulting in an underestimation of the amount of immunogenic ovalbumin peptide that is actually present. On the other hand, this underestimation might be moderate, since major bacterial proteases generate mostly small peptides (46) which are unlikely to preserve the ovalbumin 13-mer peptide that is required for an efficient binding of the DO11.10 T-cell receptor (39).

To relate live vaccine properties to the early inductive events of a specific T-cell response, a well-characterized tgTCR mouse model was used in which a few transgenic T cells recognizing ovalbumin are adoptively transferred into syngeneic, nontransgenic mice (37). After oral administration of attenuated Salmonella cells expressing GFP_OVA, there was a strong accumulation of lymphocytes but only a weak selective accumulation of ovalbumin-specific T cells in the Peyer's patches. An explanation for this result could be that many other T cells recognizing various Salmonella antigens, including the dominant antigen flagellin C (29), competed for a limited number of antigen-presenting cells. In contrast to our results, a strong selective accumulation of ovalbumin-specific T cells has been observed in the identical transgenic mouse model following subcutaneous injection of an ovalbumin-expressing Salmonella strain (6). In these experiments 108 CFU was injected so that over 1,000 times more Salmonella entered the body, in contrast to our oral immunizations with a peak colonization of only about 6 × 104 CFU, and this possibly explains the differential accumulation. Interestingly, the ca. 3 × 104 Salmonella cells that persisted in the draining lymph node from day 5 to day 12 after subcutaneous injection also failed to sustain the selective accumulation of ovalbumin-specific T cells, confirming that many Salmonella cells are required for specific T-cell accumulation. Despite the weak selective accumulation after oral administration, a substantial fraction of the ovalbumin-specific T cells became specifically activated and divided in vivo, indicating that T-cell activation was a more sensitive measurement compared to selective accumulation.

The combined data for in situ antigen expression and T-cell activation were in good agreement with a model according to which antigen localization regulates the induction of immune responses in a dose- and time-dependent fashion (47). An in situ antigen expression concentrated in the Peyer's patches and persistent over several days induced a dose-dependent localized T-cell response in the Peyer's patches with a similar time course. Peyer's patches were functional induction sites, and many locally formed T-cell blasts remained there until their first division cycles and then migrated through the mesenteric lymph nodes as expected (32).

Both the in situ antigen expression and the T-cell response exhibited biphasic kinetics, but the initial T-cell activation was much stronger compared to the small antigen peak at day 1. Possibly early antigen levels in the Peyer's patches as calculated from the number of viable bacteria (CFU) were underestimated. In vitro and in vivo data suggest that after entry of host phagocytic cells, most Salmonella cells are rapidly killed before the residual bacteria adapt to the intracellular environment, survive, and replicate (2, 28, 40). Possibly many Salmonella cells are similarly killed early after invasion of the Peyer's patches and thereby escape detection by plating and flow cytometry although they have delivered their antigen. Such an undetected initial release of antigen might explain the rather strong early activation of cognate T cells.

There was a continuous spatial separation of Salmonella and specific T cells in the Peyer's patches, although many of the T cells became activated, which requires physical contact with antigen-presenting cells. Host cells that have killed all their intracellular bacteria or that have taken up the remnants of killed cells and bacteria might migrate from the colonized subepithelial dome area to the interfollicular T-cell area where they activate cognate T cells, although such migrating cells containing killed Salmonella have not yet been detected. A migration pathway within the Peyer's patches has been previously postulated for dendritic cells (18, 22). Alternatively, infected dendritic cells might reach the interfollicular area with processes that can sometimes be as long as several hundred micrometers (43). Further studies are required to test these and other possibilities.

The data obtained in this study could be used to further optimize recombinant live Salmonella strains as carriers for foreign antigens. The in vivo downregulation of Ptac-driven antigen expression provides an additional explanation for why this promoter is suboptimal for live recombinant Salmonella-based vaccines (4). A rational optimization could be possible based on in situ expression levels and T-cell induction data for several other promoters. In addition to transcriptional regulation, antigen degradation by Salmonella stress proteases might affect the amount of antigen that can be delivered. Selective mutation of proteases such as HtrA or regulatory genes such as htpR might significantly increase the antigen level, resulting in an enhanced immune response. Moreover, secretion or surface display of the antigen instead of cytoplasmic expression (20) as well as the use of carriers with different attenuations might enhance antigen presentation to cognate T cells.

The approach and methods developed in this study make it possible to directly test these and other concepts in vivo. The findings from the transgenic system can then be validated with efficacy testing of Salmonella-based vaccines in normal hosts. One particularly attractive application would be the murine Helicobacter pylori infection model in which Salmonella-based vaccines elicit protective immunity in a CD4+ T-cell-dependent manner (8, 13, 26). Such studies might lead to a more detailed understanding of how recombinant Salmonella strains induce cellular immune responses and, eventually, to an efficient rational optimization of these promising oral vaccines.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank Thomas F. Meyer and Toni Aebischer for helpful discussions and generous support and Meike Wendland for excellent technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Balke V L, Gralla J D. Changes in the linking number of supercoiled DNA accompany growth transitions in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:4499–4506. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.10.4499-4506.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benjamin W H, Jr, Hall P, Roberts S J, Briles D E. The primary effect of the Ity locus is on the rate of growth of Salmonella typhimurium that are relatively protected from killing. J Immunol. 1990;144:3143–3151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bumann D, Hueck C, Aebischer T, Meyer T F. Recombinant live Salmonella spp. for human vaccination against heterologous pathogens. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2000;27:357–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2000.tb01450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chatfield S N, Charles I G, Makoff A J, Oxer M D, Dougan G, Pickard D, Slater D, Fairweather N F. Use of the nirB promoter to direct the stable expression of heterologous antigens in Salmonella oral vaccine strains: development of a single-dose oral tetanus vaccine. Biotechnology. 1992;10:888–892. doi: 10.1038/nbt0892-888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Y, Inobe J, Weiner H L. Inductive events in oral tolerance in the TCR transgenic adoptive transfer model. Cell Immunol. 1997;178:62–68. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1997.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Z-M, Jenkins M K. Clonal expansion of antigen-specific CD4 T cells following infection with Salmonella typhimurium is similar in susceptible (Itys) and resistant (Ityr) BALB/c mice. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2025–2029. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.4.2025-2029.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cormack B P, Valdivia R H, Falkow S. FACS-optimized mutants of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) Gene. 1996;173:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00685-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corthésy-Theulaz I E, Hopkins S, Bachmann D, Saldinger P F, Porta N, Haas R, Zheng-Xin Y, Meyer T, Bouzourène H, Blum A L, Kraehenbuhl J-P. Mice are protected from Helicobacter pylori infection by nasal immunization with attenuated Salmonella typhimurium phoPc expressing urease A and B subunits. Infect Immun. 1998;66:581–586. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.581-586.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cotter P A, DiRita V J. Bacterial virulence gene regulation: an evolutionary perspective. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2000;54:519–565. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Covone M G, Brocchi M, Palla E, Dias D S, Rappuoli R, Galeotti C L. Levels of expression and immunogenicity of attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strains expressing Escherichia coli mutant heat-labile enterotoxin. Infect Immun. 1998;66:224–231. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.224-231.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunstan S J, Simmons C P, Strugnell R A. Comparison of the abilities of different attenuated Salmonella typhimurium strains to elicit humoral immune responses against a heterologous antigen. Infect Immun. 1998;66:732–740. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.732-740.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dunstan S J, Simmons C P, Strugnell R A. Use of in vivo-regulated promoters to deliver antigens from attenuated Salmonella enterica var. Typhimurium. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5133–5141. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.10.5133-5141.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomez-Duarte O G, Lucas B, Yan Z X, Panthel K, Haas R, Meyer T F. Protection of mice against gastric colonization by Helicobacter pylori by single oral dose immunization with attenuated Salmonella typhimurium producing urease subunits A and B. Vaccine. 1998;16:460–471. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00247-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haskins K, Kubo R, White J, Pigeon M, Kappler J, Marrack P. The major histocompatibility complex-restricted antigen receptor on T cells. I. Isolation with a monoclonal antibody. J Exp Med. 1983;157:1149–1169. doi: 10.1084/jem.157.4.1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoiseth S K, Stocker B A. Aromatic-dependent Salmonella typhimurium are non-virulent and effective as live vaccines. Nature. 1981;291:238–239. doi: 10.1038/291238a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hopkins S A, Kraehenbuhl J P. Dendritic cells of the murine Peyer's patches colocalize with Salmonella typhimurium avirulent mutants in the subepithelial dome. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1997;417:105–109. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-9966-8_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hopkins S A, Niedergang F, Corthesy-Theulaz I E, Kraehenbuhl J P. A recombinant Salmonella typhimurium vaccine strain is taken up and survives within murine Peyer's patch dendritic cells. Cell Microbiol. 2000;2:59–68. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2000.00035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang F P, Platt N, Wykes M, Major J R, Powell T J, Jenkins C D, MacPherson G G. A discrete subpopulation of dendritic cells transports apoptotic intestinal epithelial cells to T cell areas of mesenteric lymph nodes. J Exp Med. 2000;191:435–444. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.3.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson K, Charles I, Dougan G, Pickard D, O'Gaora P, Costa G, Ali T, Miller I, Hormaeche C. The role of a stress-response protein in Salmonella typhimurium virulence. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:401–407. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb02122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaufmann S H, Hess J. Impact of intracellular location of and antigen display by intracellular bacteria: implications for vaccine development. Immunol Lett. 1999;65:81–84. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(98)00128-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kearney E R, Pape K A, Loh D Y, Jenkins M K. Visualization of peptide-specific T cell immunity and peripheral tolerance induction in vivo. Immunity. 1994;1:327–339. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90084-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelsall B L, Strober W. Distinct populations of dendritic cells are present in the subepithelial dome and T cell regions of the murine Peyer's patch. J Exp Med. 1996;183:237–247. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee S H, Camilli A. Novel approaches to monitor bacterial gene expression in infected tissue and host. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2000;3:97–101. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(99)00058-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levine M M, Galen J, Barry E, Noriega F, Tacket C, Sztein M, Chatfield S, Dougan G, Losonsky G, Kotloff K. Attenuated Salmonella typhi and Shigella as live oral vaccines and as live vectors. Behring Inst Mitt. 1997;98:120–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li X, Zhang G, Ngo N, Zhao X, Kain S R, Huang C C. Deletions of the Aequorea victoria green fluorescent protein define the minimal domain required for fluorescence. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28545–28549. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lucas B, Bumann D, Walduck A, Koesling J, Develioglu L, Meyer T F, Aebischer T. Adoptive transfer of CD4(+) T cells specific for subunit A of Helicobacter pylori urease reduces H. pylori stomach colonization in mice in the absence of interleukin-4 (IL-4)/IL-13 receptor signaling. Infect Immun. 2001;69:1714–1721. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1714-1721.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marshall D G, Haque A, Fowler R, Del Guidice G, Dorman C J, Dougan G, Bowe F. Use of the stationary phase inducible promoters, spv and dps, to drive heterologous antigen expression in Salmonella vaccine strains. Vaccine. 2000;18:1298–1306. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00417-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mastroeni P, Vazquez-Torres A, Fang F C, Xu Y, Khan S, Hormaeche C E, Dougan G. Antimicrobial actions of the NADPH phagocyte oxidase and inducible nitric oxide synthase in experimental salmonellosis. II. Effects on microbial proliferation and host survival in vivo. J Exp Med. 2000;192:237–248. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McSoriey S J, Cookson B T, Jenkins M K. Characterization of CD4+ T cell responses during natural infection with Salmonella typhimurium. J Immunol. 2000;164:986–993. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Medina E, Paglia P, Nikolaus T, Muller A, Hensel M, Guzman C A. Pathogenicity island 2 mutants of Salmonella typhimurium are efficient carriers for heterologous antigens and enable modulation of immune responses. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1093–1099. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1093-1099.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Medina E, Paglia P, Rohde M, Colombo M P, Guzman C A. Modulation of host immune responses stimulated by Salmonella vaccine carrier strains by using different promoters to drive the expression of the recombinant antigen. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:768–777. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200003)30:3<768::AID-IMMU768>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mowat A M, Viney J L. The anatomical basis of intestinal immunity. Immunol Rev. 1997;156:145–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb00966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murphy K M, Heimberger A B, Loh D Y. Induction by antigen of intrathymic apoptosis of CD4+CD8+TCR10 thymocytes in vivo. Science. 1990;250:1720–1723. doi: 10.1126/science.2125367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nelson C A, Vidavsky I, Viner N J, Gross M L, Unanue E R. Amino-terminal trimming of peptides for presentation on major histocompatibility complex class II molecules. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:628–633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nickerson C A, Curtiss R. Role of sigma factor RpoS in initial stages of Salmonella typhimurium infection. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1814–1823. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1814-1823.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oehen S, Brduscha-Riem K, Oxenius A, Odermatt B. A simple method for evaluating the rejection of grafted spleen cells by flow cytometry and tracing adoptively transferred cells by light microscopy. J Immunol Methods. 1997;207:33–42. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(97)00089-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pape K A, Kearney E R, Khoruts A, Mondino A, Merica R, Chen Z M, Ingulli E, White J, Johnson J G, Jenkins M K. Use of adoptive transfer of T-cell-antigen-receptor-transgenic T cells for the study of T-cell activation in vivo. Immunol Rev. 1997;156:67–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb00959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roberts M, Li J, Bacon A, Chatfield S. Oral vaccination against tetanus: comparison of the immunogenicities of Salmonella strains expressing fragment C from the nirB and htrA promoters. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3080–3087. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3080-3087.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robertson J M, Jensen P E, Evavold B D. DO11.10 and OT-II T cells recognize a C-terminal ovalbumin 323–339 epitope. J Immunol. 2000;164:4706–4712. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.9.4706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwan W R, Huang X Z, Hu L, Kopecko D J. Differential bacterial survival, replication, and apoptosis-inducing ability of Salmonella serovars within human and murine macrophages. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1005–1013. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1005-1013.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sirard J C, Niedergang F, Kraehenbuhl J P. Live attenuated Salmonella: a paradigm of mucosal vaccines. Immunol Rev. 1999;171:5–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1999.tb01340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Su T T, McClure W R. Selective binding of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase to topoisomers of minicircles carrying the TAC16 and TAC17 promoters. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:13511–13521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Szakal A K, Gleringer R L, Kosco M H, Tew J G. Isolated follicular dendritic cells: cytochemical antigen localization, Nomarski, SEM, and TEM morphology. J Immunol. 1985;134:1349–1359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Valentine P J, Devore B P, Heffron F. Identification of three highly attenuated Salmonella typhimurium mutants that are more immunogenic and protective in mice than a prototypical aroA mutant. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3378–3383. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3378-3383.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vancott J L, Chatfield S N, Roberts M, Hone D M, Hohmann E L, Pascual D W, Yamamoto M, Kiyono H, McGhee J R. Regulation of host immune responses by modification of Salmonella virulence genes. Nat Med. 1998;4:1247–1252. doi: 10.1038/3227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wickner S, Maurizi M R, Gottesman S. Posttranslational quality control: folding, refolding, and degrading proteins. Science. 1999;286:1888–1893. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5446.1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zinkernagel R M, Ehl S, Aichele P, Oehen S, Kundig T, Hengartner H. Antigen localisation regulates immune responses in a dose- and time-dependent fashion: a geographical view of immune reactivity. Immunol Rev. 1997;156:199–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb00969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]