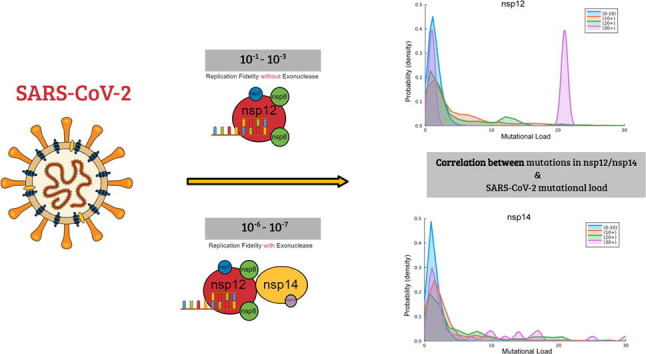

Graphical abstract

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, exoribonuclease, viral replication fidelity, mutation

Abstract

The SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus has caused a global pandemic. Despite the initial success of vaccines at preventing infection, genomic variation has led to the proliferation of variants capable of higher infectivity. Mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 genome are the consequence of replication errors, highlighting the importance of understanding the determinants of SARS-CoV-2 replication fidelity. The RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) is the central catalytic subunit for SARS-CoV-2 RNA replication and genome transcription. Here, we report the fidelity of ribonucleotide incorporation by SARS-CoV-2 RdRp (nsp12), along with its co-factors nsp7/nsp8, using steady-state kinetic analysis. Our analysis suggests that in the absence of the proofreading subunit (nsp14), the nsp12/7/8 complex has a surprisingly low base substitution fidelity (10−1–10−3). This is orders of magnitude lower than the fidelity reported for other coronaviruses (10−6–10−7), highlighting the importance of proofreading for faithful SARS-CoV-2 replication. We performed a mutational analysis of all reported SARS-CoV-2 genomes and identified mutations in both nsp12 and nsp14 that appear likely to lower viral replication fidelity through mechanisms that include impairing the nsp14 exonuclease activity or its association with the RdRp. Our observations provide novel insight into the mechanistic basis of replication fidelity in SARS-CoV-2 and the potential effect of nsp12 and nsp14 mutations on replication fidelity, informing the development of future antiviral agents and SARS-CoV-2 vaccines.

Introduction

Coronaviruses (CoV) are a group of RNA viruses that lead to respiratory illness in humans. In the past two decades, two highly pathogenic CoV strains led to outbreaks with high mortality, namely severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV, 2002), and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV, 2012).1 2019 saw the emergence of SARS-CoV-2, which shares 79.6% sequence identity with SARS-CoV, and 50% with MERS-CoV.2 The resulting outbreak of Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has developed into a global pandemic.3 According to JHU CSSE,4 in the two years following the first case reported in Wuhan, China, over 200,000,000 cases have been reported worldwide, along with over 5,000,000 deaths. With the emergence of the new Delta and Omicron variants, and long-COVID symptoms lasting for months or years despite vaccination or recovery,5 the pandemic has not yet reached its end.6

Since Aug. 2021, the FDA has approved several COVID-19 vaccines to help control the widespread transmission of SARS-CoV-2.7 However, the quick emergence of SARS-CoV-2 variants limit the efficacy of current vaccines, which were designed against the wild-type strain. Host factors, such as age, sex, serostatus and comorbidities also contribute to the declining humoral immunity after full vaccination.8 The most concerning variants include Variant Delta, which was responsible for a massive increase of infections in the United States,9 and Variant Omicron, the most recent variant found in countries worldwide.10 Importantly, viral treatments, such as vaccines and antiviral drugs, can act as a source of selective pressure that facilitates the emergence of new variants. Accordingly, these variants are thus more likely to escape vaccine-induced immune responses.11, 12, 13 As a result, breakthrough infections among fully vaccinated individuals have been reported widely.14

Viral replication fidelity is constrained to balance genome stability and viral fitness.15 Low fidelity leads to a better adaptive ability, but also carries a risk, as an excessive mutational load can decrease viral fitness. Conversely, high fidelity more faithfully maintains the integrity of the viral genome, but the lower frequency of mutation reduces the adaptive ability of the virus to the changing environment during the infection process.16, 17 Many factors contribute to the fidelity of RNA viruses. Genomic alterations can be introduced through replication errors, genetic recombination or host-mediated RNA editing.18 Out of these, the fidelity of the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) is likely the main factor responsible for the emergence of variants. This replicative enzyme tends to have a low fidelity of synthesis compared to cellular RNA polymerases or even viral DNA polymerases, resulting in the characteristic low replication fidelity of RNA viruses.19, 20

The coronaviral genome encodes six functional open reading frames (ORFs).21 The first two ORFs (ORF1a and ORF1ab) are the non-structural genes, which are translated into 16 proteins (nsp) to facilitate viral replication and transcription. Those 16 nsps assemble into cytoplasmic viral replication and transcription complexes (TRCs), which harbor a wide variety of RNA processing activities. Among them, the RdRp (also known as nsp12) is the catalytic subunit, which is central to the TRCs.22 Along with its cofactors nsp7 and nsp8 that enhance RNA binding and processivity, nsp12 plays an essential role in viral RNA replication and transcription.23 Interestingly, in addition to the RdRp activity, which is generally found in RNA viruses, CoVs also encode a 3’-5’ exoribonuclease activity (ExoN) in nsp14. nsp14 can remove 3’ mismatches and therefore provide a proofreading activity for CoVs.24 As a result, CoVs have a high fidelity ∼10−6 to 10−7compared to other RNA viruses (typically 10−3 to 10−5).25 Inactivation of ExoN in CoVs introduces a ∼15- to 20-fold increase in mutation rates.26 nsp14 needs to associate with its partner, nsp10, to maintain full ExoN activity. Studies show that nsp10 enhances nsp14 ExoN activity ∼35-fold in vitro, and mutations that disrupt the nsp14-nsp10 interaction decrease or abolishes this enhancement.27

There is evidence suggesting that alterations in nsp12 and nsp14 could play an important role in the emergence of viral variants. Viral strains containing nsp12 mutations have on average a higher number of total mutations compared to wild-type strains.28 This implies that when nsp12 mutations are present, other mutations are more likely to occur. Furthermore, a recent clinical case report associated a mutation in nsp12 (E802D) with remdesivir resistance.29 Finally, mutations in nsp14 have the strongest association with an increase in the SARS-CoV-2 mutation density.30 This strongly suggests that mutations in nsp12 and nsp14 can alter the error rate of SARS-CoV-2 replication, in turn influencing the emergence of viral variants and drug resistance.

In this study, we report the base replication fidelity of recombinant nsp12 along with its cofactors nsp7 and nsp8. We find that in the absence of proofreading activity, SARS-CoV-2 has a high misincorporation frequency. Our results suggest that the exoribonuclease activity of nsp14 plays an essential role in maintaining the relatively high-fidelity of viral replication, which is an obstacle for nucleoside analogs being developed into antiviral drugs. Taking advantage of published cryo-EM structures of nsp12 and nsp14, we analyzed all reported SARS-CoV-2 sequences for mutations in both active sites, especially the ones related to known and concerning variants. Our analysis sheds light on the rapid evolution of various SARS-CoV-2 variants, and thus provides hints for designing antivirals against SARS-CoV-2.

Materials and Methods

Protein expression

SARS-CoV-2 nsp12 was expressed in Sf9 insect cells. The donor plasmid (Addgene #154759) was transformed into DH10Bac to generate a bacmid that was then used to infect Sf9 cells. SARS-CoV-2 nsp7 (Addgene #154757) and nsp8 (Addgene #154758) were overexpressed separately in Escherichia ColiBL21(DE3) Arctic Express cells at 16 °C for 16hrs.

Protein purification

nsp12. Cells were resuspended in lysis buffer (300 mM NaCl, 50 mM HEPES PH7.4, 10% glycerol, 10 mM Imidazole, 3 mM MgCl2, 5 mM βME and protease inhibitors), lysed by sonication and cleared by centrifugation. The supernatant was bound to a Histrap HP, followed by a MBPtrap. Fractions containing the target protein were pooled and incubated with TEV protease at 4 °C overnight. The cleaved sample was flowed through a Histrap HP and a HiTrap Heparin and applied to a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex200. The peak containing nsp12 was concentrated, snap-frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80 °C.

nsp7 and nsp8 were purified separately. Cells were resuspended in lysis buffer (300 mM NaCl, 50 mM HEPES PH7.4, 10% glycerol, 10 mM Imidazole, 5 mM βME and protease inhibitors), lysed by sonication and cleared by centrifugation. The sample was applied onto a Histrap HP and eluted using a gradient. Peak fractions containing the target protein were pooled and incubated with TEV protease at 4 °C overnight. The cleaved sample was flowed through a Histrap HP and a HiTrap Q. nsp7 or nsp8-containing fractions were concentrated, snap-frozen with liquid N2 and stored at −80 °C.

RNA extension assays

The RNA extension assay was performed in a reaction buffer containing 50 mM KCl, 100 mM Tris-HCl (PH8.0) and 1 mM DTT. A fluorescent-labeled RNA primer (/Cy3/rGrUrCrArUrUrCrUrCrCrUrArArGrArArGrCrUrA) was annealed to a 40nt RNA template (rCrUrArUrCrCrCrCrArUrGrUrGrArUrUrUrUrArArUrArGrCrUrUrCrUrUrArGrGrArGrArArUrGrArC) . SARS-CoV-2 RdRp (nsp12) was incubated with its co-factors, nsp7 and nsp8 (1:2:2 molar ratio) on ice for 20 min prior to the extension reaction. The reactions (20 μl) contained the indicated divalent metal, 500 nM RNA substrate, and 500 μM rNTPs, and were initiated by the addition of 1 μM pre-incubated RdRp complex at 37 °C. The reactions were terminated after 60 min by adding 10 μl of stop solution (95% formamide, 20 mM EDTA), analyzed by PAGE and visualized using a Typhoon Imager.

SARS-CoV-2 RdRp fidelity assays

Single nucleotide incorporation assays were performed in a reaction buffer containing 50 mM KCl, 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH7.5) and 1 mM DTT. A fluorescently-labeled RNA primer (/Cy3/rGrUrCrArUrUrCrUrCrCrUrArArGrArArGrCrUrA) was annealed to a 25nt RNA template (Template A: rCrUrGrCrArUrArGrCrUrUrCrUrUrArGrGrArGrArArUrGrArC; Template U: rCrArGrCrUrUrArGrCrUrUrCrUrUrArGrGrArGrArArUrGrArC; Template C: rUrArGrUrCrUrArGrCrUrUrCrUrUrArGrGrArGrArArUrGrArC; Template G: rCrUrArCrGrUrArGrCrUrUrCrUrUrArGrGrArGrArArUrGrArC). The four templates, named A, U, C, G, included the corresponding ribonucleotide on its (+1) position. Reactions (20 μl) contained 5 mM MnCl2, 500 nM RNA substrate, and 600 nM–5 μM pre-incubated RdRp complex, and were initiated by the addition of single ribonucleotides. All reactions were carried out in 37 °C and terminated after 60 min by adding 10 μl of stop solution (95% formamide, 20 mM EDTA). RNA products were analyzed by PAGE and visualized using a Typhoon Imager.

Mutational dataset and analysis

Reported point mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 were derived from the GISAID database31 filtered from December 2019 to July 2022, which consisted of a dataset containing 11,393,744 reported genomes. We performed an initial analysis to identify the location of mutations in the structure that was limited to mutations reported with at least a 1/10,000 frequency. We subsequently decided to analyze all mutations present in five representative SARS-CoV-2 proteins (nsp2, nsp6, nsp12, nsp14 and nsp15). We selected three non-structural proteins (nsp2, nsp6, nsp15) to represent the overall mutational load.

The amino acid sequence of each protein was first aligned to the GISAID reference sequence (hCoV-19/Wuhan/WIV04/2019) using BioJulia packages. Point mutations were identified for each sequence. To calculate the mutational load for individual mutations, we calculated the mean of the mutational load for each individual sequence containing that mutation. Subsequent analysis was carried out using Python. For the purposes of this analysis, we ignored indel mutations. Furthermore, only mutations that alter the protein sequence were collected for our study. The mutational analysis of nsp12 and nsp14 took advantage of the published cryo-EM structures (PDB codes 7EIZ, 7EGQ). The statistical analysis was scaled with Bonferroni correction.

Results

Biochemical determinants of the in vitro activity of SARS-CoV-2 nsp12

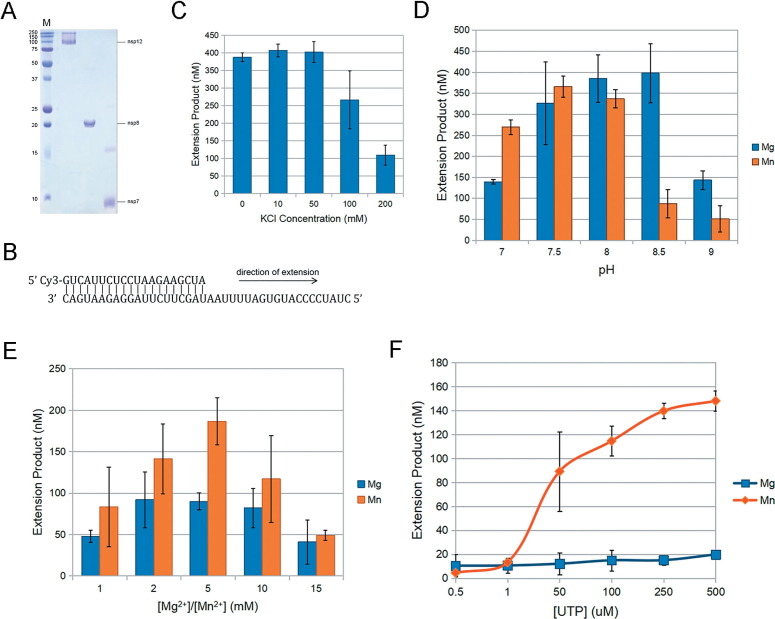

Recombinant nsp12 was expressed in Sf9 insect cells and was purified by affinity chromatography (Figure 1 (A)). As previously reported, purified nsp12 alone was unable to extend an RNA primer-template substrate in vitro.32 However, along with its co-factors nsp7/nsp8, which were both expressed in Escherichia Coli, the RdRp complex showed processive RNA-extension activity. Therefore, we characterized the ribonucleotide incorporation ability of SARS-CoV-2 RdRp using purified recombinant nsp12, nsp7 and nsp8 using in vitro RNA-extension assays. The standard RNA substrate used in this assay contains a template that mimicks the 3’-terminal 40nt of the SARS-CoV-2 genome (Figure 1(B)).

Figure 1.

Biochemical determinants of SARS-CoV-2 nsp12 activity. (A) Purified recombinant nsp12, nsp7 and nsp8. (B) Schematic showing the structure of the double-stranded RNA substrate that served as a template for primer extension. (C) Enzyme activity is highest at 10 mM-50 mM KCl. Subsequent steady-state reactions were carried out with 50 mM KCl. (D and E) The effect of pH or Mg2+/Mn2+ concentration on nsp12 activity. All reactions are carried out with 5 mM Mn2+ at pH 7.5. (F) Single rUTP incorporation with double-stranded RNA template. Results showed a ∼7.5-fold higher activity with Mn2+ than Mg2+. Error bars in C, D, E and F represent standard deviation of the mean (n = 3)

First, we determined the influence of ionic strength on RdRp activity. The polymerization activity was higher in the low KCl range (0 mM–50 mM) compared to higher KCl concentrations (Figure 1(C)). Although we did not observe a significant difference in specific activity between 0 and 50 mM KCl, we decided to conduct all subsequent experiments using 50 mM, since it is closer to physiological conditions.

We then determined the influence of pH on RdRp activity. As shown in Figure 1(D), we did not observe a significant difference in RdRp activity within pH 7.5-8.0. Therefore, we decided to conduct all experiments at physiological pH 7.5.

It is well established that polymerases rely on two or perhaps three divalent cations for polymerization.33 Metal ions bind the incoming nucleotide and facilitate the nucleophilic attack of the 3’-O on the primer to the α-phosphate of the incoming ribonucleotide to form a phosphodiester bond.34 While most polymerases use Mg2+ as their cofactors, some polymerases, such as DNA Pol μ, prefer Mn2+ for various functions in vivo. 35 Furthermore, viral RdRps, such as Bovine viral diarrhea virus (BVDV) and hepatitis C Virus (HCV), prefer Mn2+ in de novo RNA-dependent RNA synthesis.36, 37 We thus decided to test SARS-CoV-2 RdRp activity with varying Mg2+/Mn2+ concentrations. Although both Mg2+ and Mn2+ had a strong influence on nsp12 activity, Mn2+ enhanced nsp12 activity 2-fold greater than Mg2+ in vitro, and reached its optimal activity at 5 mM (Figure 1(E)). We further confirmed the biochemical determinants in single-nucleotide incorporation assays using rUTP as the substrate. As shown in Figure 1(F), Mn2+ had ∼7.5-fold higher activity than Mg2+ in single-nucleotide incorporation assays (Figure 1(F)). Thus, we decided to conduct all the steady state, single-nucleotide incorporation assays using 5 mM Mn2+.

Misincorporation frequency of the SARS-CoV-2 RdRp

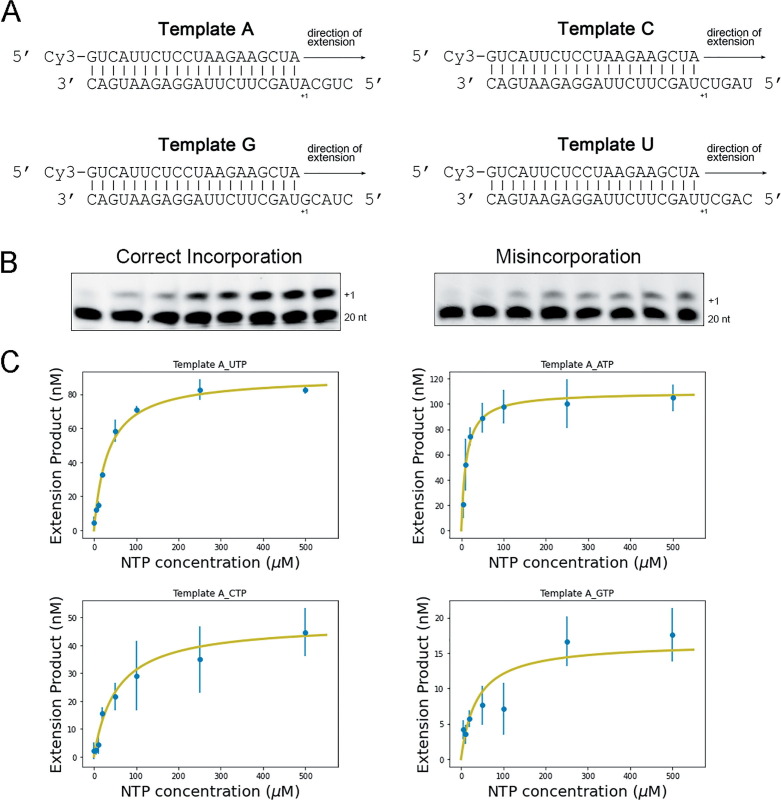

We next decided to examine the base substitution fidelity of SARS-CoV-2 nsp12. Although M13-based assays have been successfully used to determine the fidelity of DNA polymerases,38 their application to RNA polymerases involves a retrotranscription step. Hence, it becomes challenging to distinguish between errors introduced by the polymerase being studied and those made by the retrotranscriptase. We thus opted for a gel-based kinetic assay to determine the fidelity of synthesis of nsp12. We first designed template primer substrates that would allow us to determine the insertion fidelity for every possible base pair (Figure 2 (A) shows a scheme of all four RNA templates used for these experiments). We then used these substrates to establish conditions to carry out steady-state kinetic analysis of single-nucleotide incorporation for every single ribonucleotide (rAMP or rUMP or rCMP or rGMP) incorporation opposite every possible templating base. In order to ensure steady-state conditions, reactions were carried out in conditions that resulted in less than 20% of primer extension (see Figure 2(B) for a representative example and see Materials and Methods). We were able to detect and quantify the catalytic efficiency of misincorporation for all possible mispairs except for incorporation of rUMP opposite template C, which was too infrequent to allow us to observe a signal. We then determined the kinetic parameters (Km and kcat for each incorporation event by fitting to a Michaelis-Menten Equation (see Materials and Methods; Table 1 ). Figure 2(C) shows the fitted Michaelis-Menten curves for a few representative examples.

Figure 2.

Steady-state reactions with single ribonucleotide. (A) Schematic showing the four double-stranded RNA substrates for single ribonucleotide incorporation assays. (B) Representative acrylamide denaturing gels for correct incorporation and misincorporation. The 20nt labels indicate the position of the RNA primer, while +1 corresponds to the extension product. (C) Michaelis-Menten fit for reactions opposite Template A. Error bars represent standard deviation of the mean (n = 3)

Table 1.

Misincorporation frequency of SARS-CoV-2 replication complex.

| NTP | kcat(min−1) | km(mM) | kcat/km(μM−1min−1) | Misincorporation Frequencya |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Template A | ||||

| UTP | 0.0026 ± 0.0001 | 0.035 ± 0.007 | 7.28 × 10−5 | |

| ATP | 0.00028 ± 0.00003 | 0.021 ± 0.002 | 1.35 × 10−5 | 1.85 × 10−1 |

| CTP | 0.00016 ± 0.00003 | 0.068 ± 0.02 | 2.34 × 10−6 | 3.21 × 10−2 |

| GTP | 0.000075 ± 0.00001 | 0.12 ± 0.06 | 6.09 × 10−7 | 8.36 × 10−3 |

| Template G | ||||

| CTP | 0.0033 ± 0.0001 | 0.021 ± 0.002 | 1.60 × 10−4 | |

| ATP | 0.00011 ± 0.00002 | 0.0036 ± 0.001 | 2.90 × 10−5 | 1.81 × 10−1 |

| UTP | 0.00024 ± 0.00001 | 0.025 ± 0.006 | 9.00 × 10−6 | 5.61 × 10−2 |

| GTP | 0.00011 ± 0.00002 | 0.15 ± 0.09 | 7.19 × 10−7 | 4.49 × 10−3 |

| Template U | ||||

| ATP | 0.00045 ± 0.00003 | 0.0041 ± 0.001 | 1.11 × 10−4 | |

| UTP | 0.000029 ± 0.00001 | 0.031 ± 0.04 | 9.18 × 10−7 | 8.27 × 10−3 |

| CTP | 0.000033 ± 0.000007 | 0.13 ± 0.09 | 2.57 × 10−7 | 2.31 × 10−3 |

| GTP | 0.000072 ± 0.00002 | 0.081 ± 0.03 | 8.96 × 10−7 | 8.07 × 10−3 |

| Template C | ||||

| GTP | 0.0043 ± 0.0002 | 0.020 ± 0.002 | 2.09 × 10−4 | |

| ATP | 0.000072 ± 0.00002 | 0.0057 ± 0.003 | 1.27 × 10−5 | 6.08 × 10−2 |

| CTP | 0.000043 ± 0.000002 | 0.046 ± 0.006 | 9.32 × 10−7 | 4.46 × 10−3 |

| UTP | NDb | NDb | – | – |

Misincorporation frequency=(kcat/km)incorrect rNTP/(kcat/km)correct rNTP.68

ND: signal not detected.

Next, we calculated the misincorporation frequency for each pair as the ratio of the catalytic efficiency for the incorrect incorporation over the catalytic efficiency for the correct incorporation (Table 1 and see Materials and Methods).39 Surprisingly, the misincorporation frequencies of the SARS-CoV-2 RdRp complex were quite high, within the range 1.85 × 10−1–2.31 × 10−3 (Table 1). The base substitution fidelity was particularly low for events that involved incorporation of AMP (1.85 × 10−1–6.08 × 10−2). In fact, rAMP was misincorporated at a ∼10-fold higher frequency than average (4.5 × 10−2), perhaps suggesting that the RdRp has a preference for this ribonucleotide or some ability to carry out untemplated synthesis. Interestingly, the highest base substitution fidelity was observed when the RdRp was incorporating opposite a template U (8.27 × 10−3–2.31 × 10−3), while reactions with a templating C resulted in an intermediate fidelity (6.08 × 10−2–4.46 × 10−3). It is important to note that we were not able to detect extension products to a level that would permit adequate quantification, in particular for misincorporation events, and thus Mn2+ was used as the divalent ion for the fidelity assays. Mn2+ has been shown to affect the fidelity of many polymerases. In extreme cases, it can accelerate ribonucleotide misincorporation by ∼10-20 fold.40, 41, 42 Nevertheless, even accounting for this possibility, our results strongly suggest that the RdRp of SARS-CoV-2 has a surprisingly low base substitution fidelity, and that, in the absence of the proofreading activity conferred by nsp14, the RdRp has substantially lower fidelity than that observed for other RNA viruses (10−3–10−5).

Viral variants of SARS-CoV-2 carry mutations in nsp12 and nsp14 with the potential to affect replication fidelity

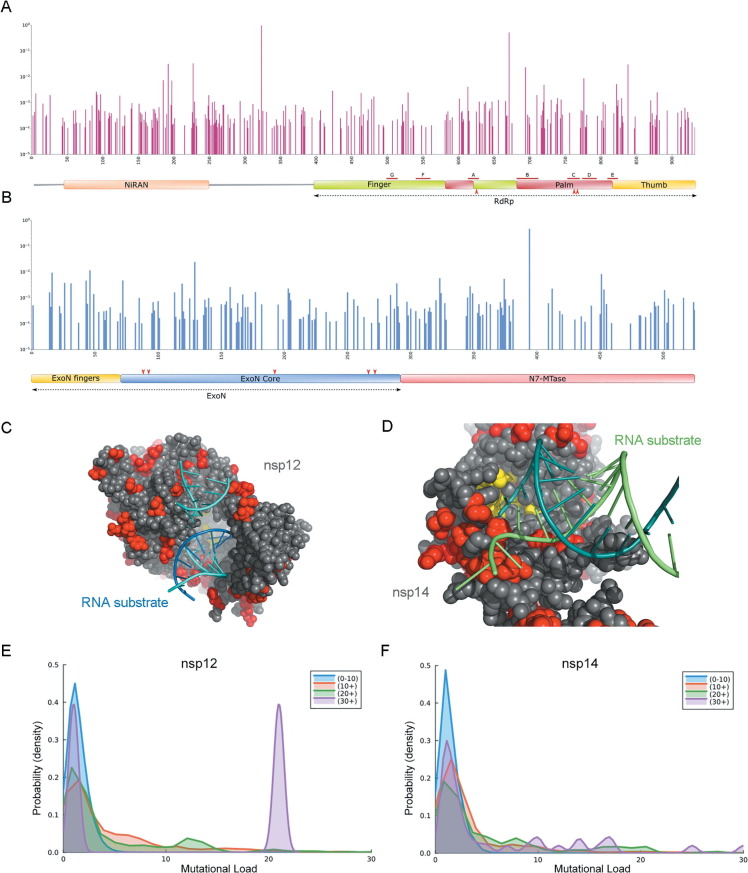

Given that our results suggest that SARS-CoV-2 might be particularly dependent on the activity of nsp14 to maintain replication fidelity, we next asked whether viral variants carry mutations in these genes that might conceivably alter the overall replication fidelity of SARS-CoV-2. We initially conducted a survey of all mutations reported worldwide located on nsp12 and nsp14 using the GISAID database. We restricted the analysis to mutations reported with at least a 1/10,000 frequency (see Materials and Methods) and mapped those mutations to the primary structure of nsp12 and nsp14. (Figure 3 (A), (B)) This revealed that no mutations are found in any of the residues known to be essential for catalysis (Asp623, Asp760, Asp761 for nsp12; Asp90, Glu92, Glu191, His268, Asp273 for nsp14). However, while most mutations appear to be distributed in the protein surface, both for nsp12 (Figure 3(C)) and nsp14 (Figure 3(D)), several mutations are in close proximity of the active site or the RNA binding residues, and often appear as clusters. This prompted us to examine whether there is a correlation between the presence of mutations in nsp12 and nsp14 and an increased mutational load. We collected 11,393,744 genomes from the GISAID database and chose three non-structural proteins (nsp2, nsp6 and nsp15) to represent the overall mutational load (see Materials and Methods). We first compared the average mutational load (sum of mutations in nsp2, nsp6 and nsp15) for sequences carrying no mutations in either nsp12 (1.12) or nsp14 (1.01) to that in sequences carrying at least one mutation in either nsp12 (1.35) or nsp14 (1.46). This difference was statistically significant (p value < 10−99). We then decided to compare the mutational load distribution depending on nsp12 or nsp14 mutation counts. As shown in Figure 3(E) and (F), when the nsp12 or nsp14 mutation counts increase, there is an increase in the probability of higher mutational load. For sequences carrying more than 30 mutations in nsp12, there is a considerable proportion of sequences showing more than 20 mutations in nsp2, nsp6 and nsp15 (Figure 3(E)). This suggested that some mutations in nsp12 and nsp14 might correlate with a higher mutational load. We thus further examined if mutations in specific residues in nsp12 or nsp14 could associate with a higher mutational load throughout the genome, prompting these differences. We determined the average mutational load for sequences carrying each distinct mutation observed in the dataset in either nsp12 or nsp14. We limited the analysis to mutations observed in at least 0.01% of sequences. We found 53 point substitutions in nsp12 and 32 substitutions for nsp14 that correlate with a significant increase in the number of total mutations compared to the mean (1.35 mutations/genome, average from 11,393,744 reported genomes). (see Table S1). We selected a threshold of a 40% increase in the mutational load to consider increases significant.

Figure 3.

SARS-CoV-2 mutational analysis. (A) Bar graph highlighting the location of point mutations in nsp12. Red lines indicated the location of conserved motifs A-G. Red arrows indicated the positions of the three catalytic residues (Asp 623, Asp760, Asp761). (B) Bar graph showing mutations on nsp14. Red arrows indicated the positions of the five catalytic residues (Asp90, Glu92, Glu191, His268, Asp273) located in the ExoN core. (C) Location of mutations on the nsp12 catalytic core (PDB code: 7C2K). Reported mutations are red. Catalytic residues are yellow. (D) Location of mutations on the structure of nsp14 (PDB code: 7N0B). Reported mutations are red. Catalytic residues are yellow. (E/F) Density plot showing the probability of a certain mutational load as a function of nsp12 (E) or nsp14 (F) mutation counts.

Discussion

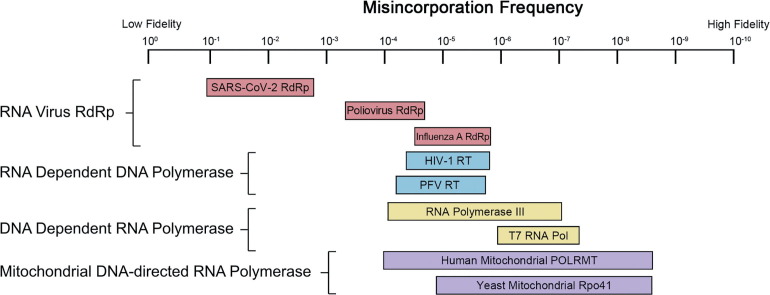

Replication fidelity is the result of several synergistic processes. DNA or RNA polymerase fidelity is often enhanced by the presence of proofreading exonucleases, and residual errors can be corrected by post-replicative repair.43, 44 Although the cellular mismatch repair system appears capable of correcting viral replicase errors,45 viral replication mainly takes advantage of polymerase fidelity and only in rare cases of proofreading. Furthermore, compared to DNA organisms, RNA viruses generally replicate their genome with low fidelity. This is in large part due to their lack of proofreading, but also to the low fidelity of RdRps.46 As a result, in the course of an infection, RNA viruses exist as a wide diversity of related genotypes, referred as “quasispecies”.17, 47 It is the large diversity of viral quasispecies that often enables the virus to escape host immunity and to develop drug resistance. The fidelity of the viral RdRp is the primary determinant of quasispecies diversity in RNA virus populations. When compared to other replicative enzymes, RdRps have the lowest fidelities, at best on par with that of retrotranscriptases (enzymes that are notorious for their low fidelity, leading to the frequent emergence of drug resistance) (Figure 4 ). Moreover, our results suggest that the SARS-CoV-2 RdRp might be one of the RdRps with the lowest fidelity. This is striking, as most other RNA viruses restrict their genome size, but coronaviruses have the largest and most complicated RNA genomes (up to 32 kb of RNA) known.48 This implies that the 3’-5’ exoribonuclease activity in their nsp14 might be crucial to achieve the replication fidelity necessary for viral fitness. It is important to stress, as stated earlier, that our approach to determine the fidelity of the RdRp has limitations. It is also unable to detect the frequency of insertions and deletions, although these have been reported to be rare.49

Figure 4.

Schematic showing the reported misincorporation frequency of selected RdRp (pink), RdDp (blue), DdRp (yellow) and mitochondrial DdRp (purple) enzymes. SARS-CoV-2 RdRp (1.85 × 10−1–2.31 × 10−3); Poliovirus RdRp (∼10−4); Influenza A RdRp (3 × 10−5–2.7 × 10−6); HIV-1 RT (6.3 × 10−5–1.4 × 10−6); PFV RT (∼5.8 × 10−5); RNA Polymerase III (2 × 10−7–1.8 × 10−4); T7 RNA Polymerase (1.35 × 10−6–9 × 10−8); Human mitochondrial POLRMT (1.3 × 10−4–5 × 10−9); Yeast Mitochondrial Rpo41 (1.06 × 10−5–5.9 × 10−9).61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67

Functional consequences of nsp12 mutations

Viral RdRps share a conserved structure that consists of a “right-handed” architecture, constituted of finger, palm and thumb subdomains.50 The active site, located in the palm subdomain, is connected to the finger subdomain through a template channel, where RNA recognition occurs.51 The regions of the RdRp that are involved in catalysis are highly conserved,52 and therefore, no mutation was observed in the nsp12 catalytic residues (Asp623, Asp760, Asp761), and very few were found in the conserved polymerase region. However, apart from the catalytic core subunit, the N-terminal portion of nsp12 contains a nidovirus RdRp-associated nucleotidyltransferase domain (NiRAN),53 where clusters of mutations were observed to enhance SARS-CoV-2 mutational load. We examined the structural context of each of the 53 mutations that is correlated with a higher mutational load, taking advantage of existing structures (See Materials and Methods). Most of these residues are located on the protein surface and are key residues for protein-protein/protein-RNA interactions. Many of these mutations would appear to affect proper formation of the RTC complex. For example, residue V435 and P918 interact with nsp14 to form an in trans backtracking dimer for proofreading.54 The V435 and P918 mutations , might thus perturb the proofreading activity by disrupting the dimer formation of nsp12 and nsp14. (Figure 5 (A)) Mutation in residue G228 might disrupt the interaction between nsp12 and nsp9. (Figure 5(B)) Since nsp9 has been reported to stabilize the nsp12-nsp14 interaction,54 these mutations could affect the proper formation of a RTC complex. Mutations on residues V675 (2.80), S384 (2.78) and V330 (1.89) which form a salt bridge between nsp12 and its cofactor nsp8, presumably alter the nsp12/nsp8 interaction. (Table S1) (Figure 5(C)).

Figure 5.

Mutations on nsp12 and nsp14 that correlate with a higher mutational load. (A) V435 and P918 (green) are on the region of nsp12 (red) that interacts with nsp14 (orange) to form a trans dimer for proofreading (PDB code: 7EGQ). (B-E) PDB code: 7EIZ. (B) G228 (green) is on the region of nsp12 (red) that interacts with nsp9 (blue). (C) V330, V675 and S384 (green) are on the interaction region between nsp12 (red) and nsp8 (blue). (D) H26, A23 and M57 (green) on nsp14 (orange) that interact with nsp10 (blue). (E) Y154 (green) on nsp14 (orange) interacts with nsp12 (red). (F) M501 (green) is on the region of nsp14 (orange) that interacts with nsp12 (magenta) to form a trans dimer for proofreading (PDB code: 7EGQ).

Functional consequences of nsp14 mutations

nsp14 contains an ExoN domain on its N-terminus, which can be further subdivided into a finger region and ExoN core, and an N7-MTase domain on its C-terminus, which catalyzes mRNA capping (Figure 3(B)). The reported exonuclease catalytic residues (Asp90, Glu92, Glu191, His268 and Asp273), are located in the ExoN core, which concerts with nsp12 and helicases for proofreading.55, 56 Many of the mutations that we identified would appear to affect proofreading by altering protein-protein interactions. Mutations in nsp14, H26, A23 and M57 might disrupt the interaction between nsp14 and its cofactor nsp10. (Figure 5(D)) Mutation in Y154, might similarly disrupt the interaction with nsp12. (Figure 5(E), Table S1).Interestigly, we also observed a correlation between the M501L mutation and a higher mutational load. (Figure 5(F)) M501 is located in the nsp14 N7-MTase domain, which is not involved in RTC formation. However, it stabilizes the conformation of a helix which interacts with nsp12 to form a backtracking dimer for proofreading.54 This is consistent with previous reports.57

Conclusions

The evolutionary rate of SARS-CoV-2 has been estimated to be between 2 × 10−3–4 × 10−4 per nucleotide per year.58 This low fidelity likely explains the rapid rise of SARS-CoV-2 variants, which have prolonged the pandemic. Our results suggest that given the low intrinsic fidelity of the RdRp, some mutations that through different mechanisms are able to impair the proofreading activity of nsp14 might lead to a drastic increase in mutational rates, which might contribute to the rapid emergence of variants in SARS-CoV-2. This would also imply that pharmacological inactivation of nsp14 might decrease replication fidelity to a sufficient extent to result in error catastrophe, and a critical decrease in viral fitness.59 This approach, lethal mutagenesis, has been previously suggested as a therapeutic strategy for RNA viruses. For example, Ribavirin increases the mutation rate of Poliovirus by four-fold, and reduced viral fitness to by 95%.60 Inactivation of nsp14 in other CoVs results in an increase of 15-20 fold in the mutation rate, and although the resulting strains are viable,26 the same might not be true for SARS-CoV-2 given the potentially lower RdRp fidelity. Inhibition of nsp14 might also serve as a coadjuvant therapy to ribonucleotide analogs, as it would prevent removal of incorporated analogs by the exonuclease.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Xingyu Yin: Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Horia Popa: Investigation. Anthony Stapon: Investigation. Emilie Bouda: Investigation. Miguel Garcia-Diaz: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Dr. Zihe Rao (Tsinghua University) and Dr. Xiuna Yang (ShanghaiTech Univerisity) for providing the SARS-CoV-2 nsp12/nsp7/nsp8 plasmids for Escherichia Coli system. We thank Dr. Vladyslava Sokolova and Dr. Dongyan Tan (Stony Brook University) for their technical assistance and helpful discussion on the Sf9 cell system. This work was funded by a seed grant from the Office of the Vice President for Research, Stony Brook University. We gratefully acknowledge all data contributors, i.e., the Authors and their Originating laboratories responsible for obtaining the specimens, and their Submitting laboratories for generating the genetic sequence and metadata and sharing via the GISAID Initiative, on which this research is based.

Edited by Eric O. Freed

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2023.167973.

Appendix A. Supplementary Data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Cui J., Li F., Shi Z.L. Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019;17(3):181–192. doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou P., Yang X.L., Wang X.G., Hu B., Zhang L., Zhang W., Si H.R., Zhu Y., et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J., Zhao X., Huang B., et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. New Engl. J. Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.“COVID-19 Data Repository by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University” (2020) Available at: https://github.com/CSSEGISandData/COVID-19.

- 5.Notarte K.I., Catahay J.A., Velasco J.V., Pastrana A., Ver A.T., Pangilinan F.C., Peligro P.J., Casimiro M., et al. Impact of COVID-19 vaccination on the risk of developing long-COVID and on existing long-COVID symptoms: A systematic review. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;53:101624. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2022.101624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dong E., Du H., Gardner L. An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20(5):533–534. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ndwandwe D., Wiysonge C.S. COVID-19 vaccines. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2021;71:111–116. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2021.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Notarte K.I., Guerrero‐Arguero I., Velasco J.V., Ver A.T., Santos de Oliveira M.H., Catahay J.A., Khan M.S.R., Pastrana A., et al. Characterization of the significant decline in humoral immune response six months post-SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination: A systematic review. J. Med. Virol. 2022;94(7):2939–2961. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown C.M., Vostok J., Johnson H., Burns M., Gharpure R., Sami S., Sabo R.T., Hall N., et al. Outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 infections, including COVID-19 vaccine breakthrough infections, associated with large public gatherings—Barnstable County, Massachusetts, July 2021. Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2021;70(31):1059. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7031e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.WHO. “Classifification of Omicron (B.1.1.529): SARS-CoV-2 Variant of Concern.” (2021). Available at: https://www.who.int/news/item/26-11-2021-classifification-of-omicron-(b.1.1.529)-sars-cov-2-variant-of-concern.

- 11.Choi B., Choudhary M.C., Regan J., Sparks J.A., Padera R.F., Qiu X., Solomon I.H., Kuo H.H., et al. Persistence and evolution of SARS-CoV-2 in an immunocompromised host. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;383(23):2291–2293. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2031364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tarhini H., Recoing A., Bridier-Nahmias A., Rahi M., Lambert C., Martres P., Lucet J.C., Rioux C., et al. Long term SARS-CoV-2 infectiousness among three immunocompromised patients: from prolonged viral shedding to SARS-CoV-2 superinfection. J. Infect. Dis. 2021;223(9):1522–1527. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiab075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leung W.F., Chorlton S., Tyson J., Al-Rawahi G.N., Jassem A.N., Prystajecky N., Masud S., Deans G.D., et al. COVID-19 in an immunocompromised host: persistent shedding of viable SARS-CoV-2 and emergence of multiple mutations: a case report. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022;114:178–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.10.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burki T. Understanding variants of SARS-CoV-2. Lancet. 2021;397(10273):462. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00298-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith E.C., Sexton N.R., Denison M.R. Thinking outside the triangle: replication fidelity of the largest RNA viruses. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2014;1(1):111–132. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-031413-085507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mokili J.L., Rohwer F., Dutilh B.E. Metagenomics and future perspectives in virus discovery. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2012;2(1):63–77. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vignuzzi M., Stone J.K., Arnold J.J., Cameron C.E., Andino R. Quasispecies diversity determines pathogenesis through cooperative interactions in a viral population. Nature. 2006;439(7074):344–348. doi: 10.1038/nature04388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mistry P., Barmania F., Mellet J., Peta K., Strydom A., Viljoen I.M., James W., Gordon S., et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants, vaccines, and host immunity. Front. Immunol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.809244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Domingo E.J.J.H., Holland J.J. RNA virus mutations and fitness for survival. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1997;51:151. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.51.1.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drake J.W., Holland J.J. Mutation rates among RNA viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1999;96(24):13910–13913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.13910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ziebuhr J. The coronavirus replicase. Coronavirus Replicat. Reverse Genet. 2005:57–94. doi: 10.1007/3-540-26765-4_3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahn D.G., Choi J.K., Taylor D.R., Oh J.W. Biochemical characterization of a recombinant SARS coronavirus nsp12 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase capable of copying viral RNA templates. Arch. Virol. 2012;157(11):2095–2104. doi: 10.1007/s00705-012-1404-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kirchdoerfer R.N., Ward A.B. Structure of the SARS-CoV nsp12 polymerase bound to nsp7 and nsp8 co-factors. Nat. Commun. 2019;10(1):1–9. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10280-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Minskaia E., Hertzig T., Gorbalenya A.E., Campanacci V., Cambillau C., Canard B., Ziebuhr J. Discovery of an RNA virus 3′→ 5′ exoribonuclease that is critically involved in coronavirus RNA synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006;103(13):5108–5113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508200103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sevajol M., Subissi L., Decroly E., Canard B., Imbert I. Insights into RNA synthesis, capping, and proofreading mechanisms of SARS-coronavirus. Virus Res. 2014;194:90–99. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2014.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eckerle L.D., Becker M.M., Halpin R.A., Li K., Venter E., Lu X., Scherbakova S., Graham R.L., et al. Infidelity of SARS-CoV Nsp14-exonuclease mutant virus replication is revealed by complete genome sequencing. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(5):e1000896. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bouvet M., Imbert I., Subissi L., Gluais L., Canard B., Decroly E. RNA 3'-end mismatch excision by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus nonstructural protein nsp10/nsp14 exoribonuclease complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012;109(24):9372–9377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1201130109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pachetti M., Marini B., Benedetti F., Giudici F., Mauro E., Storici P., Masciovecchio C., Angeletti S., et al. Emerging SARS-CoV-2 mutation hot spots include a novel RNA-dependent-RNA polymerase variant. J. Transl. Med. 2020;18(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02344-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gandhi S., Klein J., Robertson A.J., Peña-Hernández M.A., Lin M.J., Roychoudhury P., Lu P., Fournier J., et al. De novo emergence of a remdesivir resistance mutation during treatment of persistent SARS-CoV-2 infection in an immunocompromised patient: a case report. Nat. Commun. 2022;13(1):1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29104-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eskier D., Suner A., Oktay Y., Karakülah G. Mutations of SARS-CoV-2 nsp14 exhibit strong association with increased genome-wide mutation load. PeerJ. 2020;8:e10181. doi: 10.7717/peerj.10181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khare S., Gurry C., Freitas L., Schultz M.B., Bach G., Diallo A., Akite N., Ho J., et al. GISAID’s role in pandemic response. China CDC Weekly. 2021;3(49):1049. doi: 10.46234/ccdcw2021.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peng Q., Peng R., Yuan B., Zhao J., Wang M., Wang X., Wang Q., Sun Y., et al. Structural and biochemical characterization of the nsp12-nsp7-nsp8 core polymerase complex from SARS-CoV-2. Cell Rep. 2020;31(11):107774. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang J., Konigsberg W.H. Two-metal-ion catalysis: Inhibition of DNA polymerase activity by a third divalent metal ion. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022;9 doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2022.824794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steitz T.A., Steitz J.A. A general two-metal-ion mechanism for catalytic RNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1993;90(14):6498–6502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang Y.K., Huang Y.P., Liu X.X., Ko T.P., Bessho Y., Kawano Y., Maestre-Reyna M., Wu W.J., et al. Human DNA polymerase μ can use a noncanonical mechanism for multiple Mn2+-mediated functions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141(21):8489–8502. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b01741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yi G.H., Zhang C.Y., Cao S., Wu H.X., Wang Y. De novo RNA synthesis by a recombinant classical swine fever virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Eur. J. Biochem. 2003;270(24):4952–4961. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ranjith-Kumar C.T., Kim Y.C., Gutshall L., Silverman C., Khandekar S., Sarisky R.T., Kao C.C. Mechanism of de novo initiation by the hepatitis C virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase: role of divalent metals. J. Virol. 2002;76(24):12513–12525. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.24.12513-12525.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boyer J.C., Bebenek K., Kunkel T.A. Unequal human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcriptase error rates with RNA and DNA templates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1992;89(15):6919–6923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.15.6919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Creighton S., Goodman M.F. Gel kinetic analysis of DNA polymerase fidelity in the presence of proofreading using bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase (∗) J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270(9):4759–4774. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aggarwal S., Bradel-Tretheway B., Takimoto T., Dewhurst S., Kim B. Biochemical characterization of enzyme fidelity of influenza A virus RNA polymerase complex. PLoS One. 2010;5(4):e10372. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Achuthan V., DeStefano J.J. Alternative divalent cations (Zn2+, Co2+, and Mn2+) are not mutagenic at conditions optimal for HIV-1 reverse transcriptase activity. BMC Biochem. 2015;16:12. doi: 10.1186/s12858-015-0041-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vashishtha A.K., Konigsberg W.H. The effect of different divalent cations on the kinetics and fidelity of Bacillus stearothermophilus DNA polymerase. AIMS Biophys. 2018;5(2):125–143. doi: 10.3934/biophy.2018.2.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fijalkowska I.J., Schaaper R.M., Jonczyk P. DNA replication fidelity in Escherichia coli: a multi-DNA polymerase affair. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2012;36(6):1105–1121. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2012.00338.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kunkel T.A., Bebenek K. DNA replication fidelity. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2000;69:497. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tang L.Y., Zhang J. The cellular mismatch repair system is able to repair mismatches within MLV retroviral double-stranded DNA at a low frequency. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(12):2302–2306. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.12.2302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steinhauer D.A., Domingo E., Holland J.J. Lack of evidence for proofreading mechanisms associated with an RNA virus polymerase. Gene. 1992;122(2):281–288. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90216-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Domingo E., Sheldon J., Perales C. Viral quasispecies evolution. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2012;76(2):159–216. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.05023-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Saberi A., Gulyaeva A.A., Brubacher J.L., Newmark P.A., Gorbalenya A.E. A planarian nidovirus expands the limits of RNA genome size. PLoS Pathog. 2018;14(11):e1007314. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mercatelli D., Giorgi F.M. Geographic and genomic distribution of SARS-CoV-2 mutations. Front. Microbiol. 2020;11:1800. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gao Y., Yan L., Huang Y., Liu F., Zhao Y., Cao L., Wang T., Sun Q., et al. Structure of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from COVID-19 virus. Science. 2020;368(6492):779–782. doi: 10.1126/science.abb7498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cameron C.E., Moustafa I.M., Arnold J.J. Fidelity of nucleotide incorporation by the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from poliovirus. The Enzymes. 2016;39:293–323. doi: 10.1016/bs.enz.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jiang Y., Yin W., Xu H.E. RNA-dependent RNA polymerase: Structure, mechanism, and drug discovery for COVID-19. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021;538:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.08.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang H., Rao Z. Structural biology of SARS-CoV-2 and implications for therapeutic development. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021;19(11):685–700. doi: 10.1038/s41579-021-00630-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yan L., Yang Y., Li M., Zhang Y., Zheng L., Ge J., Huang Y.C., Liu Z., et al. Coupling of N7-methyltransferase and 3′-5′ exoribonuclease with SARS-CoV-2 polymerase reveals mechanisms for capping and proofreading. Cell. 2021;184(13):3474–3485. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu C., Shi W., Becker S.T., Schatz D.G., Liu B., Yang Y. Structural basis of mismatch recognition by a SARS-CoV-2 proofreading enzyme. Science. 2021;373(6559):1142–1146. doi: 10.1126/science.abi9310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moeller N.H., Shi K., Demir Ö., Belica C., Banerjee S., Yin L., Durfee C., Amaro R.E., et al. Structure and dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 proofreading exoribonuclease ExoN. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 2022;119(9) doi: 10.1073/pnas.2106379119. e2106379119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Takada K., Ueda M.T., Watanabe T., Nakagawa S. Genomic diversity of SARS-CoV-2 can be accelerated by a mutation in the nsp14 gene. bioRxiv. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2023.106210. 2020-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tao K., Tzou P.L., Nouhin J., Gupta R.K., de Oliveira T., Kosakovsky Pond S.L., Fera D., Shafer R.W. The biological and clinical significance of emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2021;22(12):757–773. doi: 10.1038/s41576-021-00408-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eigen M. Error catastrophe and antiviral strategy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2002;99(21):13374–13376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212514799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Graci J.D., Cameron C.E. Quasispecies, error catastrophe, and the antiviral activity of ribavirin. Virology. 2002;298(2):175–180. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim H., Ellis V.D., III, Woodman A., Zhao Y., Arnold J.J., Cameron C.E. RNA-dependent RNA polymerase speed and fidelity are not the only determinants of the mechanism or efficiency of recombination. Genes. 2019;10(12):968. doi: 10.3390/genes10120968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pauly M.D., Procario M.C., Lauring A.S. A novel twelve class fluctuation test reveals higher than expected mutation rates for influenza A viruses. Elife. 2017;6:e26437. doi: 10.7554/eLife.26437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weiss K.K., Bambara R.A., Kim B. Mechanistic role of residue Gln151 in error prone DNA synthesis by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) reverse transcriptase (RT): pre-steady state kinetic study of the Q151N HIV-1 RT mutant with increased fidelity. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277(25):22662–22669. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200202200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Boyer P.L., Stenbak C.R., Hoberman D., Linial M.L., Hughes S.H. In vitro fidelity of the prototype primate foamy virus (PFV) RT compared to HIV-1 RT. Virology. 2007;367(2):253–264. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.05.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sultana S., Solotchi M., Ramachandran A., Patel S.S. Transcriptional fidelities of human mitochondrial POLRMT, yeast mitochondrial Rpo41, and phage T7 single-subunit RNA polymerases. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292(44):18145–18160. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.797480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Huang J., Brieba L.G., Sousa R. Misincorporation by wild-type and mutant T7 RNA polymerases: identification of interactions that reduce misincorporation rates by stabilizing the catalytically incompetent open conformation. Biochemistry. 2000;39(38):11571–11580. doi: 10.1021/bi000579d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Alic N., Ayoub N., Landrieux E., Favry E., Baudouin-Cornu P., Riva M., Carles C. Selectivity and proofreading both contribute significantly to the fidelity of RNA polymerase III transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2007;104(25):10400–10405. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704116104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Boosalis M.S., et al. DNA polymerase insertion fidelity. Gel assay for site-specific kinetics. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262(30):14689–14696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.