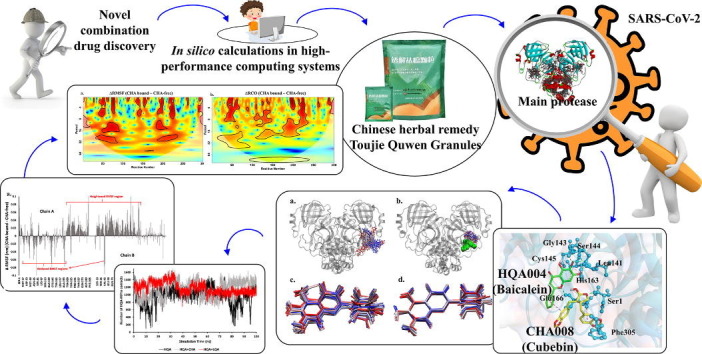

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Combination drug therapy, Natural products, COVID-19, Virus diseases, Computers molecular, Computer simulation

Abbreviations: ADME/T, absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion and toxicity; COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; H-bonds, hydrogen bonds; LD50, median lethal dose; MD, molecular dynamics; MM-PBSA, molecular mechanics Poisson Boltzmann surface area; Mpro, main protease; PAINS, Pan-assay interference compounds; RCO, inter-residue contact order; RMSF, root-mean-square-fluctuation; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; SMILES, Simplified Molecular-input Line-entry System; TCMSP, traditional Chinese medicine systems pharmacology database and analysis platform; TQG, Toujie Quwen Granule

Abstract

Combination drugs have been used for several diseases for many years since they produce better therapeutic effects. However, it is still a challenge to discover candidates to form a combination drug. This study aimed to investigate whether using a comprehensive in silico approach to identify novel combination drugs from a Chinese herbal formula is an appropriate and creative strategy. We, therefore, used Toujie Quwen Granules for the main protease (Mpro) of SARS-CoV-2 as an example. We first used molecular docking to identify molecular components of the formula which may inhibit Mpro. Baicalein (HQA004) is the most favorable inhibitory ligand. We also identified a ligand from the other component, cubebin (CHA008), which may act to support the proposed HQA004 inhibitor. Molecular dynamics simulations were then performed to further elucidate the possible mechanism of inhibition by HQA004 and synergistic bioactivity conferred by CHA008. HQA004 bound strongly at the active site and that CHA008 enhanced the contacts between HQA004 and Mpro. However, CHA008 also dynamically interacted at multiple sites, and continued to enhance the stability of HQA004 despite diffusion to a distant site. We proposed that HQA004 acted as a possible inhibitor, and CHA008 served to enhance its effects via allosteric effects at two sites. Additionally, our novel wavelet analysis showed that as a result of CHA008 binding, the dynamics and structure of Mpro were observed to have more subtle changes, demonstrating that the inter-residue contacts within Mpro were disrupted by the synergistic ligand. This work highlighted the molecular mechanism of synergistic effects between different herbs as a result of allosteric crosstalk between two ligands at a protein target, as well as revealed that using the multi-ligand molecular docking, simulation, free energy calculations and wavelet analysis to discover novel combination drugs from a Chinese herbal remedy is an innovative pathway.

1. Introduction

Combination drugs, which have been utilized for the management of serval diseases for many years, is a medicine that consists of more than one active ingredient combined into a single dosage form [1]. Famous combination drugs, such as paxlovid (nirmatrelvir/ritonavir) for Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) [2], caduet (amlodipine/atorvastatin) for cardiovascular diseases [3], and cafergot (ergotamine/caffeine) for headaches [4], have been widely used in clinical practice. The primary reason for using combination drugs is because it may produce better therapeutic effects, based on the most desirable interaction of the ingredients, synergism [5]. Relieving the toxicity of the ingredients, which may lead to fewer adverse events [6], and reducing the incidence of drug resistance, which is a challenge for the management of cancer and microbial infections [7], are the other purposes to develop combination drugs. However, finding two or more ingredients with synergistic effects that may have the potential to form a combination drug is still a challenge.

Traditional Chinese medicine is an important part of primary health care in Asian countries that has utilized complex herbal formulations (consisting of two or more medicinal herbs) for treating diseases for thousands of years. There seems to be a general assumption that the synergistic therapeutic effects of Chinese herbal medicine derive from the complex interactions between the multiple bioactive components within the herbs and/or herbal formulations. It is reasonable to believe that the identification of compounds with synergistic effects from a Chinese herbal formula whose treatment effects have been supported by clinical evidence is a better choice, compared to conventional approaches to screening potential candidates from small molecular or approved drug databases. Here, we used a Chinese herbal remedy, Toujie Quwen Granules (TQG), for the management of COVID-19 as a case study, for investigating whether the identification of novel combination drugs from a Chinese herbal formula via multi-ligand molecular docking, simulation, free energy calculations and wavelet analysis is an appropriate and innovative strategy.

COVID-19 was declared a pandemic on the 11th of March 2020 [8]. The infectious agent responsible for causing this disease was identified as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [9]. For treatment options, a number of vaccines have since been established, resulting in reductions in the likelihood of severe illnesses [10]. There is also a focus on drug repurposing however more recent studies question the effectiveness of such drugs for COVID-19 [11]. Moreover, no COVID-19-specific antiviral drugs have yet been approved by the Food and Drug Administration, with only paxlovid approved for emergency use, but only for patients at risk of severe diseases [12]. The simultaneous prevalence of both COVID-19 and influenza, especially during winter, is also a particular cause for public health concerns, and reinforces the urgency of effective treatments for both [13].

The main protease (Mpro), also called 3-chymotrypsin-like protease, is one of the significant targets of SARS-CoV-2 [14]. Evidence showed that the ∼34 KDa (306 amino acid residues) Mpro plays an essential role in the viral life cycle as it can release functional polypeptides when translated RNA via dealing with viral polyproteins [15]. Mpro is a homodimer with biological activities and it involves two protomers (monomer A and monomer B) and their catalytic dyad on each one is defined by two key residues (Cys145 and His41) [15], [16]. The search for Mpro inhibitors with antiviral effects against SARS-CoV-2 is of particular interest in response to mitigating the current severe scenario [15], [17], [18], [19]. The effort for finding such inhibitors has extended to medicinal plants, typically used for traditional herbal medicine, and thus far various natural compounds have been identified as Mpro inhibitors through computational methods [20], [21], [22], [23], [24]. These methods include molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulation, and other binding free energy calculations such as molecular mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann and surface area (MM-PBSA), which are the standard techniques for computer-aided drug discovery today [25], [26]. Besides seeking inhibitors at the active binding sites, some researchers believe that there are other approaches to restrict the catalytic activity of the protease via small molecules or peptides since they may hinder the dimerization of the two protomers [27].

Traditional Chinese medicine has been used for the management of epidemics for thousands of years in China [28]. The terminology of Wen Yi (pestilence), presenting similar COVID–19–related symptoms, was first recorded in Su Wen (Plain Questions) approximately 2000 years ago [29]. Nowadays, Chinese medicine still plays an important role in the COVID–19 outbreak in China [30]. Within all herbal formulae used in clinical practice, TQG is a novel COVID-19 Chinese herbal medicine, comprised of 16 herbs, and has been highly recommended in China as a complementary remedy for patients in the early stage of the disease [31]. Recently published studies regarding TQG for SARS-CoV-2 claimed that compounds identified in TQG may restrict viral infection, regulate the human immune system and relieve inflammation, and the Mpro of SARS-CoV-2 may be one of the drug targets of TQG compounds [31], [32]. This study, therefore, through a case study, aimed to utilize a comprehensive approach including multi-ligand molecular docking, simulation, free energy calculations and wavelet analysis, to investigate the possible synergy of multiple compounds from TQG bound to the same target, Mpro of SARS-CoV-2. This study also provided insights into novel combination drug discovery.

2. Materials and methods

All modeling was performed on the National Computational Infrastructure high-performance computing system 'Gadi' (24-core Intel Xeon Scalable ‘Cascade Lake’ processors), the Pawsey supercomputing system 'Magnus' (12-core Intel Xeon E5-2690 V3 'Haswell' processors), and the GPGPU partition of the University of Melbourne Research Services system 'Spartan' (Intel Xeon CPU E5-2650 v4 with P100 Nvidia GPUs).

2.1. Chemical compounds identified from the TQG’s ingredients

We used the same methods as the recently published TQG papers to identify compounds from the formula [31], [32]. Specifically, we searched the Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database and Analysis Platform (TCMSP; https://tcmsp-e.com/) to identify chemical compounds from TQG’s ingredients [33]. The TCMSP is a comprehensive platform that has been widely used to investigate the systems pharmacology of a herbal formula for a disease, receiving more than 300 citations. It includes all the 499 herbs in the Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of Chinese with 12,144 herbal compounds, as well as the pharmacokinetic properties of the compounds [33]. All data in the database was manually collected and updated by its developers and maintainers. The Chinese pinyin names of the 16 herbs were used as the keywords to search in the database. Oral bioavailability and drug-likeness were set as ‘≥ 30%’ and ‘≥ 0.18′ respectively that were recommended by the database, as compounds with these characteristics may appear drug-like properties with great oral bioactivities [32]. To better understand the mechanisms of action of a compound in relation to the herbs from which the compound originated, duplicated compounds were retained at this stage.

Two researchers (H.L. and M.L.) screened the searching data and extracted them into a pre-designed Excel form, including compound names, molecular identity, molecular weight, and their pharmacokinetic properties (AlogP, hydrogen-bond donors and acceptors, oral bioavailability, drug-likeness, blood–brain barrier, fractional water accessible surface area of all atoms with a negative partial charge, human intestinal cell line Caco-2 permeability and drug half-life). All data was checked by another researcher (A.Y.). Any disagreement among these three researchers was discussed with the third party (A.H.) where needed.

2.2. Acquisition of structures of identified ligands

For the structures of each compound from TQG, we searched them in the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) for its PubChem CID/SID number and 3D structures [34]. We obtained each compound structure in standard Simplified Molecular-input Line-entry System (SMILES) (SDF file) format. For compounds without 3D structures in the PubChem database, MOL2 files of the compounds were downloaded from the TCMSP database [33]. Then we converted all ligand structures into conventional protein structure PDB file format using Discovery Studio Visualizer 2019 [35].

2.3. Preparation of target proteins of SARS-CoV-2

The main protease of SARS-CoV-2 was selected for this study. Mpro is a pivotal enzyme of SARS-CoV-2 to mediate viral replication and transcription [36]. As we reported in our recently published papers, due to the functional significance of Mpro for the virus, it has been used as a drug target with great potential [14], [37]. The structures of Mpro (PDB ID: 6LU7) with the structural resolution of 2.16 Å were downloaded from the RCSB PDB Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org) in PDB format [36]. Then the protein structure was examined and compared using the protein visualization and analysis software Visual Molecular Dynamics [38]. The protein structure retrieved from the RCSB database was pre-processed using PyRx for subsequent computational docking studies [39].

2.4. Single ligand molecular docking between ligands and Mpro for SARS-CoV-2

Single ligand molecular docking of the ligands and target proteins was performed by AutoDock Vina (v1.1.2) using the PyRx GUI (v0.8) as a front–end for ligand and receptor preparation, and production of docking parameter files [35], [39], [40]. Although the active sites of the protease are known, blind docking was performed in which the entire protein was searched for possible ligand binding sites, since alternative sites are also possible sites for potential inhibitors [41]. All ligand and protein files were converted to PDBQT format in preparation for docking by PyRx from their PDB files. A grid box was defined (Supplementary Information S1), the size of which was selected to cover the entire protein and accommodate the compounds from the herbal ingredients applied for blind docking [31]. This was achieved by using the ‘maximize box’ function provided in PyRx [35]. The conformations of the proteins and ligands were respectively set to rigid and flexible [35]. All parameters were set as default, with the exhaustiveness parameter set to 48 for all dockings. All rotatable torsions were activated for the ligands, while the receptors were assumed to be rigid [35]. All molecules were ranked according to their predicted docking score, which was based on the empirical free energy function [35].

3D structures and 2D visualizations of ligand–residue interactions were analyzed at their predicted docking poses by the Discovery Studio Visualizer 2019, which was also used to show the ligand-residue contact plots [35]. Then, we searched the RCSB Protein Data Bank database to identify the known active binding sites and the key active binding site residues of Mpro protein [42]. The number of hydrogen bonds (H-bonds) between compounds located at the active binding sites and key active site residues was calculated [35]. Potential inhibitors from the formula were identified based on the above analyses.

2.5. Inhibitors identified from single ligand docking selected to build the Ligand-target complex for Multi-ligand docking based on Text-mining data

We searched three English databases including PubMed, EMBASE and CINAHL from their respective earliest records to 28th September 2021 and updated them on 16th December 2021 to identify potentially relevant pharmacological studies. We selected the following keywords including the names of predicted compounds identified from single ligand docking, COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, main protease, 3C-like protease, and their synonyms. The reference list of review papers was also screened manually to identify potential research (search strategy in Supplementary Table S1). We considered all types of original pharmacological studies of the potential inhibitors, published in English, regardless of the type of studies (in vitro or in vivo). We included the studies if they used the potential compounds as the intervention. We excluded the studies if they were review articles or did not include pharmacological experiments or did not test the pharmacological effects of the potential compounds for the main protease of SARS-CoV-2 or were published in a non-English language. We descriptively summarized the characteristics of the included pharmacological studies and identified the known inhibitors within the potential compounds from single ligand molecular docking. The known inhibitors were selected for subsequent analyses.

2.6. Multiple ligands docking to investigate synergistic interactions within compounds from TQG

Potential synergistic interactions were investigated between known inhibitors identified in Section 2.5 and all compounds from TQG. Known inhibitors identified from text-mining were selected to create an inhibitor-target complex for multi-ligand molecular docking. To build the inhibitor-Mpro complex, firstly, we performed single ligand docking. Considering the Mpro contains two chains, the difference is that we conducted ‘focused’ docking on monomer A and monomer B of Mpro protein, respectively, to receive predicted binding positions of the same inhibitors in both chains. Then, we utilized Discovery Studio Visualizer 2019 to manually combine both inhibitors to the Mpro protein [35]. Thirdly, we used MGLTools 1.5.6 to convert the Mpro protein and the two identical inhibitors’ PDB files to the ‘receptor.PDBQT’ files [43]. Finally, we utilized Autodock Vina in command line mode to perform dockings of other ligands identified from TQG to the receptor.PDBQT files, as usual [40].

This round of docking predicted the docking positions and orientations of second ligands to those of the initial ligand (known inhibitors). The interaction energy between the first ligand and the second ligand, together with Mpro protein, was predicted using molecular docking scoring functions in Autodock Vina, to predict and identify supportive ligands which could substantially enhance the binding affinity of the original inhibitors [40]. Concurrently, second ligands whose predicted binding positions were directly close to initial inhibitors were selected to perform structural analyses via Discovery Studio Visualizer 2019, to visualize the 3D structures and 2D visualizations of ligand–residue interactions [35]. The numbers of H-bonds between second ligands and Mpro were calculated. Second ligands, which are physically close to the initial ligands and form H-bonds with Mpro, as well as could significantly enhance the binding affinity of the original inhibitors, may therefore serve as synergistic compounds which could improve the efficacy of the originally identified inhibitors.

2.7. Virtual pharmacokinetic and toxicity prediction

The successful development of a drug relies critically on understanding its pharmacokinetics and potential toxicity, as well as its propensity to be falsely identified as bioactive [44]. Herbal compounds located at the known active binding sites of Mpro were selected for absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion and toxicity (ADME/T) prediction. Pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS) amongst herbal compounds which may produce false positives in biological screening assays were assessed by an online platform False Positive Remover (https://www.cbligand.org/PAINS/) [45]. Subsequently, herbal compounds which were most likely to be suitable candidates for potential therapies were then examined for their ADME/T properties using two online platforms, including SwissADME (https://www.swissadme.ch/) and Pro Tox-Ⅱ (https://tox.charite.de) [46], [47]. The ADME/T properties of each identified herbal compound were measured to assess the pharmacokinetic attributes of the compound within the human body using ADME/T descriptor functions implemented in these methods. These methods quantitatively predict properties by a set of rules that specify ADME/T characteristics, such as human intestinal absorption, aqueous solubility, blood–brain barrier permeation, drug-likeness, predicted median lethal dose (LD50), predicted toxicity class and hepatotoxicity [46], [47].

2.8. Molecular dynamics simulations and analyses

We used GROMACS 2018.2 to perform MD simulation [37], [48], [49] with the CHARMM27 force field [50], [51]. We utilized SwissParam to generate ligand topology for HQA004, CHA008, LQA003, and the peptidomimetic ligand N3 [52]. We solved the protein-initial ligand-second ligand complexes identified from Section 2.6 in a dodecahedral box filled with TIP3P water and we set a minimum of 2.0 nm distance between any protein atoms to the closest box edge [53]. To neutralize the charge, we added sodium ions into the box. We used a steepest-descent gradient approach to minimize energy with a maximum of 500,000 steps. Then, we utilized isothermal-isochloric and isothermal-isobaric ensembles to restrain each complex for 100 ps. We maintained temperature and pressure at 310 K and 1.0 bar, using a modified Berendsen thermostat [54] and a Parrinello-Rahman barostat [55], respectively. We applied the LINCS algorithm to restrict bond lengths [56] and concurrently, we used the particle-mesh Ewald scheme to calculate their long-range electrostatic forces with a 0.16 nm grid space [57]. For short-range nonbonded interactions, we used cutoff ratios of 1.2 nm for Coulomb and van der Waals potentials. A total of 100 ns simulations were conducted with a time-step of 2 fs in triplicate. The velocities were generated randomly based on a Maxwell distribution. To analyze and visualize the simulation trajectories, we used Visual Molecular Dynamics 1.9.3 [38], [58]. Additionally, we used MM-PBSA to perform the free energy calculations [59] via the g_mmpbsa tool [60] on 1 ns segments of the triplicate stabilized trajectories [61]. Then, we utilized the Adaptive Poisson-Boltzmann Solver to calculate the energy contributions from electrostatic, van der Waals, and polar solvation terms [62]. We set the grid spacing to 0.05 nm and we set a value of 80 and 2, respectively, for solvent and solute dielectric constants. For the non-polar energy contribution, we used solvent-accessible surface area to calculate (probe radius set to 0.14 nm). However, we did not calculate the entropic energy terms in this study. Other MD simulation analyses including root-mean-square-deviation, root-mean-square-fluctuation (RMSF), radius of gyration and inter-residue contact order (RCO) were calculated using the suite of analysis tools implemented in GROMACS.

Wavelet analysis was performed on residue sequential data derived from RMSF and RCO in order to extract further details of the impact of synergistic ligand binding on the dynamics and intramolecular contacts of Mpro [63]. This analysis enabled the determination of periodic behavior in dynamics or residue contacts at each position by estimating the contributions of different periodic functions with a range of frequencies [63]. Wavelet power spectra were calculated using R-4.2.1 [64] and the biwavelet library version 0.20.21 (github.com/tgouhier/biwavelet) for per-residue RMSF and RCO data on both HQA004 and HQA004/CHA008-bound complex simulations using the default Morlet wavelet and associated parameters.

3. Results

3.1. HQA004 (baicalein) in TQG is the only known inhibitor of Mpro identified from docking and text-mining

Based on the ingredients of TQG, we searched the TCMSP database to identify the natural agents for subsequent analyses. Details of the herbs from TQG were provided in Table 1 . A total of 1489 compounds were identified and 238 of them were included in this study. Characteristics of the 238 compounds and their SMILES are presented in Supplementary Tables S2 and S3. We then performed single ligand molecular docking for the 238 compounds against the Mpro, receiving 238 docking results. The more negative the binding score in a molecular docking result, the better the binding affinity of the compound to the target protein [35]. The total binding affinity of all these 238 compounds was −1830.1 kcal/mol, with an average binding energy of −7.69 kcal/mol, which means most herbal compounds from TQG bound with intermediate binding affinity to the protease. Details of the docking results are shown in Supplementary Tables S4 and S5. The clusters of predicted binding positions indicated by ligand−binding poses are presented in Fig. 1 a. A sum of 186 compounds was predicted to bind at the inter-monomer interface of domain III of Mpro (residues 200–300), involving ligands with the top 10 binding affinities. Compounds located at these primary binding pockets were generally large molecules with diverse structures, occupying 78.15% of all TQG compounds. It is important to note that there is no currently known inhibitor located at the primary binding sites.

Table 1.

Ingredients of Toujie Quwen Granules and numbers of compounds identified from the database.

| Chinese Pinyin names | Pharmaceutical names | Chinese names | Dosages | Abbr. | Search results | Included compounds | Category of medicinals | Sub-category of medicinals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lian qiao | Forsythiae Fructus | 连翘 | 30 | LQA | 150 | 23 | Heat-clearing medicinals | Heat-clearing and detoxicating medicinals |

| Shan ci gu | Pseudobulbus Cremastrae Seu Pleiones | 山慈菇 | 20 | SCG | 18 | 3 | Heat-clearing medicinals | Heat-clearing and detoxicating medicinals |

| Jin yin hua | Lonicerae Japonicae Flos | 金银花 | 15 | JYH | 236 | 23 | Heat-clearing medicinals | Heat-clearing and detoxicating medicinals |

| Huang qin | Scutellariae Radix | 黄芩 | 10 | HQA | 143 | 36 | Heat-clearing medicinals | Heat-clearing and dampness-drying medicinals |

| Da qing ye | Isatidis Folium | 大青叶 | 10 | DQY | 45 | 10 | Heat-clearing medicinals | Heat-clearing and detoxicating medicinals |

| Chai hu | Bupleuri Radix | 柴胡 | 5 | CHA | 349 | 17 | Exterior-releasing medicinals | Pungent-cool exterior-releasing medicinals |

| Qing hao | Artemisiae Annuae Herba | 青蒿 | 10 | QHA | 126 | 22 | Heat-clearing medicinals | Deficiency heat-clearing medicinals |

| Chan tui | Cicadae Periostracum | 蝉蜕 | 10 | N/A | 8 | 0 | Exterior-releasing medicinals | Pungent-cool exterior-releasing medicinals |

| Qian hu | Peucedani Radix | 前胡 | 5 | QHB | 101 | 24 | Expectorant antitussive and antiasthmetics medicinals | Phlegm-resolving medicinals |

| Chuan bei mu | Fritillariae Cirrhosae Bulbus | 川贝 | 10 | CBM | 63 | 13 | Expectorant antitussive and antiasthmetics medicinals | Phlegm-resolving medicinals |

| Zhe bei mu | Fritillariae Thunbergii Bulbus | 浙贝 | 10 | ZBM | 17 | 7 | Expectorant antitussive and antiasthmetics medicinals | Phlegm-resolving medicinals |

| Wu mei | Mume Fructus | 乌梅 | 30 | WMA | 40 | 8 | Astringent medicinals | Lung-intestine astringent medicinals |

| Xuan shen | Scrophulariae Radix | 玄参 | 10 | XSA | 47 | 9 | Heat-clearing medicinals | Heat-clearing and blood-cooling medicinals |

| Huang qi | Scutellariae Radix | 黄芪 | 45 | HQB | 87 | 20 | Tonifying and replenishing medicinals | Qi-tonifying medicinals |

| Fu ling | Poria | 茯苓 | 30 | FLA | 34 | 15 | Dampness-resolving medicinals | Dampness-draining diuretic medicinals |

| Tai zi shen | Pseudostellariae Radix | 太子参 | 15 | TZS | 25 | 8 | Tonifying and replenishing medicinals | Qi-tonifying medicinal |

Note: Abbr.: Abbreviations. Data was retrieved from the Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database and Analysis Platform (TCMSP; https://tcmsp-e.com/).

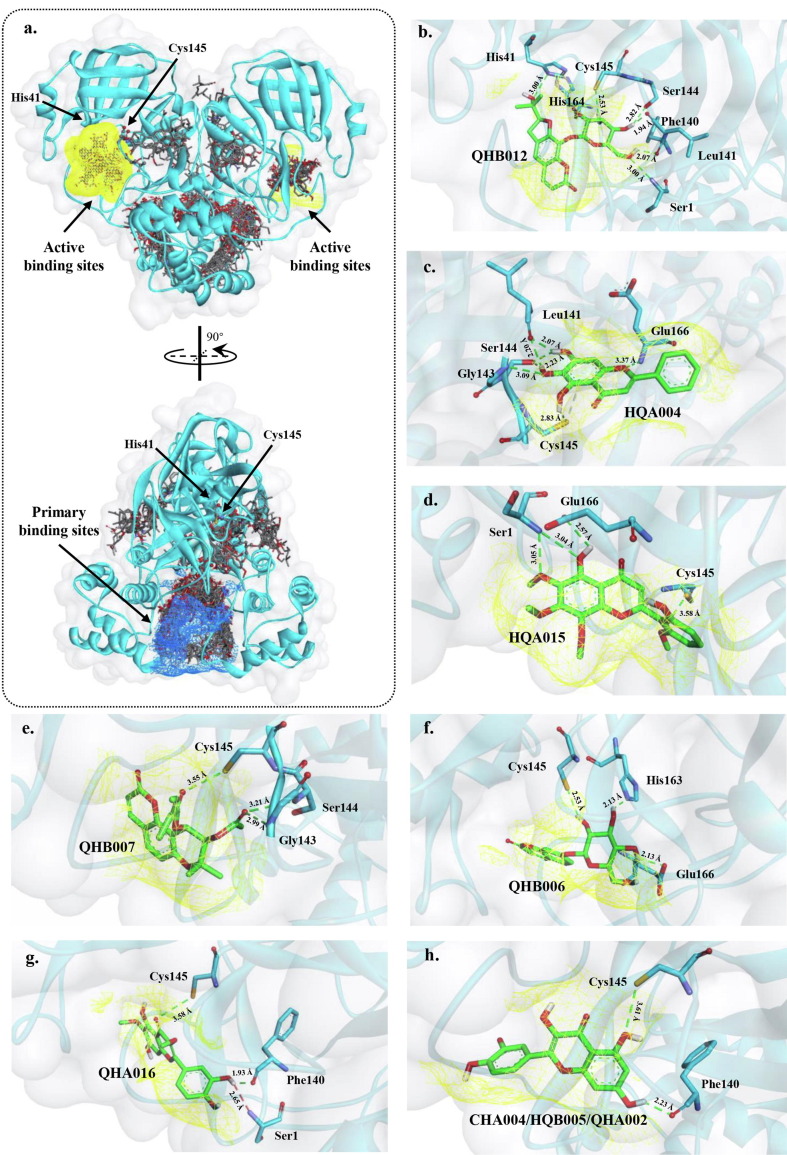

Fig. 1.

Crystal structures of SARS-CoV-2 main protease in complex with compounds from the herbal remedy Toujie Quwen Granules. a) Docking pose interactions between all compounds and the protease. The yellow wire mesh is the surface area of the active binding sites of the protease, whereas the surface of primary binding pockets is labeled in blue wire mesh. His41 and Cys145 are the key active binding site residues. b-h) interactions formed between the seven potential inhibitors identified from single ligand molecular docking and surrounding residues. The yellow wire mesh is the surface area of their binding pockets. Hydrogen bonds are presented by green dashed lines and their distances are labeled respectively. Corresponding compound names were presented in Supplementary Table S3.

Additionally, herbal compounds that were predicted to bind at the two known active sites at each monomer may be more likely to act as inhibitors of Mpro. A total of 32 compounds were located directly at these two active sites and all the 32 components formed H-bonds with one of the residues in the areas (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table S6). Compounds, which directly formed an H-bond to two key active site residues (catalytic dyad residues His41 and Cys145) [65], may restrict the normal enzymatic function of these side chains, resulting in inhibiting the biological function of Mpro [14], [66]. Nine compounds formed H-bonds with one or more catalytic dyad residues. After the removal of duplicated compounds, seven compounds are listed in Fig. 1b to i and Supplementary Fig. S1. These seven compounds were chosen for subsequent analyses, whereas other compounds that formed H-bonds with other residues could be considered for further pharmacological investigation.

We used a comprehensive text-mining approach to identify inhibitors to construct an initial ligand-target complex for multi-ligand molecular docking. We identified 26 studies and 3 of them that met the inclusion criteria were included for analysis [66], [67], [68]. Combining the evidence from our single ligand molecular docking as well as cells and computational investigation in the included studies, HQA004 (baicalein), as a known inhibitor of the Mpro, was chosen to create the initial compound-protein complex. Detailed information regarding the text-mining section can be found in Supplementary Information S2, Supplementary Fig. S2, and Supplementary Tables S7 and S8.

Additionally, we also compared the binding poses of HQA004 and two other standard inhibitors, including the synthetic peptidomimetic inhibitor of 6LU7, N3 [36], as well as nirmatrelvir, one of the ingredients of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved drug paxlovid (PDB ID 7TE0) [69] (Supplementary Fig. S3). It is easy to note that all three ligands formed seven H-bonds with the protease respectively, even though they have different structures. Both HQA004 and nirmatrelvir bound to the same key binding site residue Cys145, and the distance of H-bonds between HQA004 and Mpro (2.83 Å) was shorter than nirmatrelvir (3.06 Å). Other residues, such as Glu166, which can be found in all three ligand-target complexes, as well as Gly143, which can be seen in N3-Mpro and HQA004-Mpro complexes, are formed H-bonds with the ligands. Interestingly, most of the residues that formed H-bonds with the ligands were different, such as Leu141 and Ser144 in HQA004-Mpro complex, Phe140, Gln189 and Thr190 in N3-Mpro, and His163 and Gln192 in nirmatrelvir-Mpro. Comparing the binding positions among these three compounds, we believed that HQA004 may appear similar therapeutic effects to nirmatrelvir and N3 for the protease, as they interacted with serval key active site residues of the protein.

3.2. Docking identifies HQA004 and CHA008 as a synergistic inhibitor-modulator pair

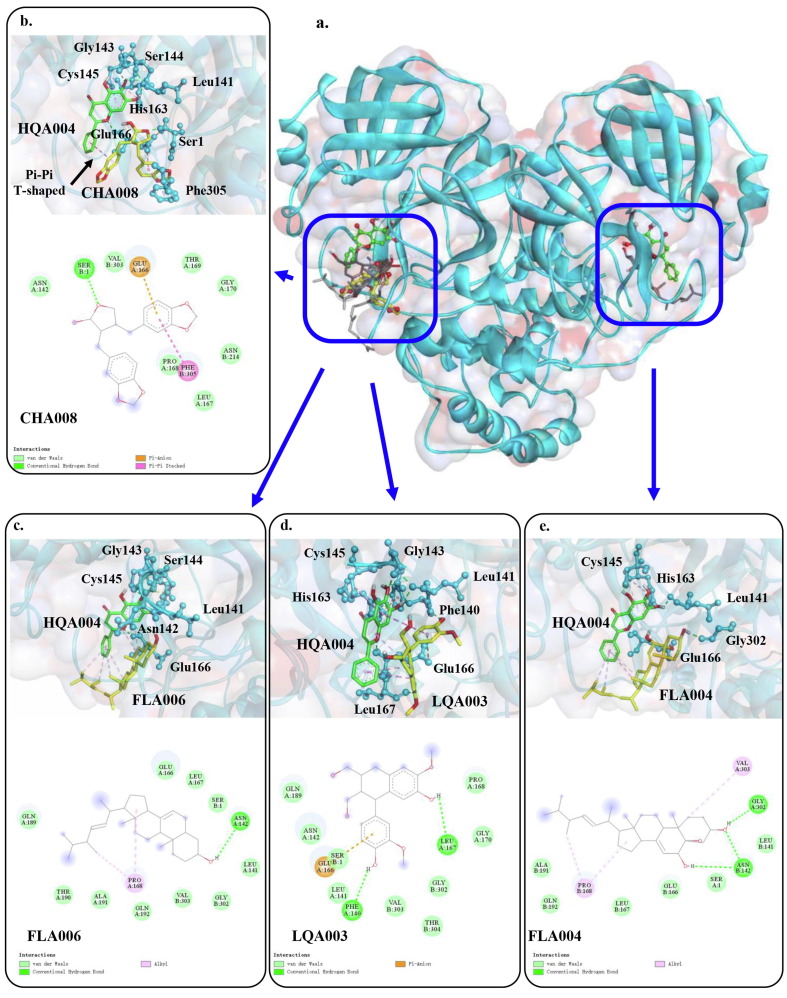

We performed multiple ligand molecular docking between all TQG compounds and the HQA004-Mpro complex. A total of 238 docking results were predicted (affinity range: −4.6 to −10.3 kcal/mol; total binding affinity: −1862.6 kcal/mol; average binding score: −7.67 kcal/mol). Details of the multi-ligand docking data are listed in Supplementary Table S9. The clusters of predicted multi-ligand binding positions are presented in Fig. 2 a and Supplementary Fig. S4a. More specifically, five compounds including CHA008 (cubebin; −8 kcal/mol), FLA004 (cerevisterol; −8.2 kcal/mol), FLA006 (ergosta-7,22E-dien-3β-ol; −7.9 kcal/mol), HQA029 (supraene; −6.3 kcal/mol) and LQA003 ((2R,3R,4S)-4-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxy-phenyl)-7-methoxy-2,3-dimethylol-tetralin-6-ol; −6.9 kcal/mol) from TQG were predicted directly connecting to HQA004 and locating at one of the active binding sites. Three compounds were bound with intermediate affinity (−7 to −9 kcal/mol) to the HQA004-Mpro complex, which means that they might interact selectively with the receptor. Although two weak binding affinity compounds were reported (>−7 kcal/mol), they cannot be ignored as dynamic interactions may happen, such as ‘ligand swapping’ and reversible binding, between the two compounds and the complex structure. However, it can only be examined in further studies.

Fig. 2.

Synergistic binding modes of the four compounds directly connected to HQA004 (baicalein) against the main protease of SARS-CoV-2. HQA004 is presented in green color sticks. a) Overview of the structure of HQA004 bound to the four compounds. b-e) 3D/2D binding poses of the four compounds complex with HQA004 and their surrounding residues that were predicted by multiple ligand molecular docking. Hydrogen bonds are presented by green dashed lines while hydrophobic bonds are in pink. Corresponding compound names were presented in Supplementary Table S3.

Hydrophobic bonds were found between all five compounds and the aromatic groups of HQA004, including Pi-Pi T-shaped, Pi-Alkyl and Pi-Sigma. When two hydrophobic molecules attract and move together, interactions of Pi-electron cloud (hydrophobic bonds) are formed. These interactions may be behind the stability of HQA004 at the active binding pocket. H-bonds (primarily an electrostatic force) were found between the four compounds (CHA008, FLA004, FLA006 and LQA003) and Mpro. The formation of such strong bonds indicates that these four compounds may produce biological activity upon the receptor, stabilizing the helical structure of the protein around the active binding sites, and hence securing HQA004 in place. Fig. 2b to e and Supplementary Fig. S4b present the actual binding poses between the five compounds and the HQA004-Mpro complex.

Further structural analysis suggests that the CHA008-HQA004-Mpro complex is more stable than the four other complexes. When CHA008 was placed into the space occupied by HQA004, more interactions were predicted among the ligands and the protein. One of the aromatic groups of CHA008 formed a Pi-Pi T-shaped interaction with the aromatic group of HQA004, with a distance of 4.77 Å (Fig. 2b). At the same time, the other aromatic group of CHA008 formed two hydrophobic bonds, on either side of itself, with the residues of Glu166 (Pi-Anion, 3.25 Å) and Phe305 (Pi-Stacked, 4.04 Å). Furthermore, H-bond was found between CHA008 and Ser1, with a short distance of 1.88 Å. These three bonds provided forces between CHA008 and the three residues including Ser1, Glu166 and Phe305 from three different directions simultaneously, and these bonds may be contributing to a final total affinity from CHA008 to HQA004 via the Pi-Pi T-shaped interaction. Noting that Glu166 has been claimed by a previous study as a critical residue for ligand-Mpro binding [70]. These complex bond formations made the helical structures of the active binding pocket difficult to open, stabilizing HQA004 to connect with the catalytic residue Cys145 via H-bonds. Although a similar structure was also found in LQA003, the distances of LQA003 to HQA004 and multiple residues of the protein were longer than CHA008, partly contributing to the lower binding affinity of LQA003 to the HQA004-Mpro complex than CHA008. However, multiple ligand molecular docking can only provide a preliminary understanding of the possible synergistic effects between the five compounds and HQA004 against Mpro. We, therefore, provided multiple ligand MD simulations to further test their dynamic interactions in the virtual physiological environment.

3.3. Most of the compounds with therapeutic potentials identified from docking were druglike and non-toxic

The ADME/T properties of the 37 herbal compounds were predicted. Table 2 provides the pharmacokinetics and toxicity properties of the 37 compounds identified from TQG. These 37 compounds belonged to two different groups, including compounds located at the active binding pockets from the single ligand molecular docking, and compounds that were close to HQA004 (the initial know inhibitor) from multiple ligand molecular docking. Evaluation on the online PAINS platform showed 34 compounds passed through the PAINS filter. However, three compounds, including CHA016, QA010, and QHA016, did not pass, which means these three compounds may lead to false positives in biological screening tests [71].

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties of the potential compounds identified from Toujie Quwen Granules.

| No. | Compounds codes | PAINS | GI absorption | BBB permeant |

Lipophilicity consensus Log Po/w |

Water solubility (ESOL) | Drug-likeness | Toxicity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted LD50 (mg/kg) | Predicted toxicity Class | Hepatotoxicity | ||||||||

| (I) Compounds located at the active binding sites identified from the single ligand molecular docking | ||||||||||

| 1 | CHA004 | Pass | High | No | 1.65 | Soluble | Yes | 5000 | 5 | Inactive |

| 2 | CHA005 | Pass | High | No | 1.58 | Soluble | Yes | 3919 | 5 | Inactive |

| 3 | CHA010 | Pass | High | No | 0.98 | Very soluble | Yes | 1770 | 4 | Inactive |

| 4 | CHA016 | Fail | High | No | 1.57 | Soluble | Yes | 500 | 4 | Inactive |

| 5 | HQA001 | Pass | High | No | 2.52 | Moderately soluble | Yes | 4000 | 5 | Inactive |

| 6 | HQA002 | Pass | High | No | 2.54 | Moderately soluble | Yes | 3919 | 5 | Inactive |

| 7 | HQA004 | Pass | High | No | 2.24 | Moderately soluble | Yes | 3919 | 5 | Inactive |

| 8 | HQA009 | Pass | High | No | 1.94 | Soluble | Yes | 2000 | 4 | Inactive |

| 9 | HQA010 | Fail | High | No | 1.58 | Soluble | Yes | 3919 | 5 | Inactive |

| 10 | HQA011 | Pass | High | Yes | 2.88 | Moderately soluble | Yes | 4000 | 5 | Inactive |

| 11 | HQA015 | Pass | High | No | 2.4 | Moderately soluble | Yes | 5000 | 5 | Inactive |

| 12 | HQA027 | Pass | High | Yes | 2.4 | Moderately soluble | Yes | 200 | 3 | Inactive |

| 13 | HQA034 | Pass | High | No | 1.87 | Soluble | Yes | 2000 | 4 | Inactive |

| 14 | HQB005 | Pass | High | No | 1.65 | Soluble | Yes | 5000 | 5 | Inactive |

| 15 | HQB013 | Pass | High | No | 2.01 | Soluble | Yes | 10 | 2 | Inactive |

| 16 | HQB014 | Pass | High | No | 2.3 | Soluble | Yes | 2500 | 5 | Inactive |

| 17 | HQB015 | Pass | High | No | 1.58 | Soluble | Yes | 3919 | 5 | Inactive |

| 18 | JYH018 | Pass | Low | No | −0.78 | Very soluble | No; 2 violations: MW > 350, Rotors > 7 | 2000 | 4 | Inactive |

| 19 | LQA004 | Pass | High | Yes | 3.47 | Moderately soluble | Yes | 2000 | 4 | Inactive |

| 20 | LQA019 | Pass | High | No | 1.58 | Soluble | Yes | 3919 | 5 | Inactive |

| 21 | QHA002 | Pass | High | No | 1.65 | Soluble | Yes | 5000 | 5 | Inactive |

| 22 | QHA006 | Pass | High | No | 1.58 | Soluble | Yes | 3919 | 5 | Inactive |

| 23 | QHA015 | Pass | High | No | 2.11 | Soluble | Yes | 2500 | 5 | Inactive |

| 24 | QHA016 | Fail | High | No | 1.73 | Soluble | Yes | 5000 | 5 | Inactive |

| 25 | QHA018 | Pass | High | No | 2.11 | Soluble | Yes | 2500 | 5 | Inactive |

| 26 | QHB005 | Pass | High | Yes | 3.05 | Moderately soluble | Yes | 1000 | 4 | Inactive |

| 27 | QHB006 | Pass | High | No | −0.29 | Very soluble | Yes | 4500 | 5 | Inactive |

| 28 | QHB007 | Pass | High | No | 3.12 | Moderately soluble | Yes | 832 | 4 | Inactive |

| 29 | QHB012 | Pass | Low | No | −0.2 | Soluble | No; 1 violation: MW > 350 | 1000 | 4 | Inactive |

| 30 | WMA001 | Pass | High | No | 1.84 | Soluble | Yes | 2000 | 4 | Inactive |

| 31 | ZBM001 | Pass | High | No | 1.76 | Soluble | Yes | 500 | 4 | Inactive |

| 32 | ZBM004 | Pass | High | No | 1.22 | Soluble | Yes | 1500 | 4 | Inactive |

| (II) Compounds closed to HQA004 identified from the multiple ligand molecular docking | ||||||||||

| 1 | CHA008 | Pass | High | Yes | 2.9 | Moderately Soluble | No; 1 violation, MW > 350 | 980 | 4 | Inactive |

| 2 | FLA004 | Pass | High | No | 4.99 | Moderately Soluble | No; 2 violation, MW > 350, XLOGP3 > 3.5 | 2340 | 5 | Inactive |

| 3 | FLA006 | Pass | Low | No | 6.57 | Poorly soluble | No; 2 violations: MW > 350, XLOGP3 > 3.5 | 2000 | 4 | Inactive |

| 4 | HQA029 | Pass | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A; Flexibility alarm, numbers of rotatable bonds > 9 | 5000 | 5 | Inactive |

| 5 | LQA003 | Pass | High | No | 2.02 | Soluble | No; 1 violation: MW > 350 | 5000 | 5 | Inactive |

Note: BBB: Blood-brain barrier; ESOL: Estimated solubility; GI: Gastrointestinal; LD50: median lethal dose; MW: Molecular weight; N/A: Not applicable; PAINS: Pan-assay interference compounds. Drug-likeness parameters from SWISSADME: 250 ≤ MW ≤ 350, XLOGP ≤ 3.5, numbers of ratable bonds ≤ 7. Predicted toxicity class from Pro Tox-Ⅱ: Class 1: Fatal if swallowed (LD50 ≤ 5), Class 2: Fatal if swallowed (5 < LD50 ≤ 50), Class III: Toxic if swallowed (50 < LD50 ≤ 300), Class 4: Harmful if swallowed (300 < LD50 ≤ 2000), Class 5: May be harmful if swallowed (2000 < LD50 ≤ 5000), Class 6: Non-toxic (LD50 > 5000). Corresponding compound names were provided in Table S3.

SwissADME and Protox-II were used to predict the pharmacokinetics and toxicity properties of compounds for the early stage of drug design and evaluation [46], [47]. Chemical properties as followed were calculated, such as gastrointestinal absorption, blood–brain barrier permeant, lipophilicity, water-solubility, drug-likeness, and toxicity including predicted median lethal dose (LD50), predicted toxicity class and hepatotoxicity. It is worth mentioning that 30 compounds (81.08%) were drug-like and ideal candidates for the condition. This helps to optimize pharmacokinetics and drug properties, such as solubility and chemical stability. All five compounds from multiple ligand molecular docking appeared to have poor drug-likeness. It is significant to know that the main reason contributing to poor results is that their molecular weight is greater than 350 g/mol. Concerning absorption parameters, 33 compounds provided promising oral availability, and most compounds exhibited low blood–brain barrier permeability (89%). Dosage forms are important for drug formulation because they may affect the rate and degree of absorption of the drug in the body. The results of consensus Log Po/w and water solubility (estimated solubility) demonstrated that most of the compounds appeared to have good water solubility, which could provide a reference for the formulation design of pharmaceutical preparations.

In terms of toxicity prediction, all 37 compounds presented no hepatotoxicity. For toxicity class prediction, 35 compounds were level 4 or 5 compounds, which means they are non-toxic compounds (94.6%). Only one compound (HQA027) showed toxicity if swallowed (predicted LD50 200 mg/kg) and one compound (HQB013) may be fatal if swallowed (predicted LD50 10 mg/kg). It should be cautious when applying these two compounds for further studies, especially for dosage determination. Virtual pharmacokinetic and toxicity prediction is an important component in assessing whether a drug is toxic or absorbable in drug discovery [72]. Based on our findings, most of the compounds identified from docking and simulation were potentially therapeutic and non-toxic chemicals, showing the desired characteristic behavior of drug-like molecules. Considering the drug-likeness and toxicity properties of the five compounds identified from multi-ligand molecular docking, we selected the complex of CHA008-HQA004-Mpro, as our priority for our subsequent MD simulation and detailed biophysical analysis. The five compounds which were predicted, through docking, to be in close proximity to the main inhibitor HQA004, are detailed in Table 2. Amongst this list, compounds FLA004 and FLA006 exhibit 2 violations of druglikeness (including poor lipophilicity), and are likely to be poor candidates for further therapeutic development. HQA029 has no gastrointestinal absorption, and violates druglikeness in terms of the number of rotatable bonds and molecular size. Therefore, based on ADMET considerations, FLA004, FLA006 and HQA029 were excluded for consideration as favorable synergistic co-ligands to HQA004. The remaining compounds, CHA008 and LQA003, exhibit similar generally favorable structural and ADMET properties, and were considered for MD simulation and analysis. However, as detailed in section 3.5, free energy calculations strongly suggest that CHA008 is a potentially far more effective synergistic co-ligand than LQA003.

To provide a degree of validation for the soundness of our MD simulation methodology, we have performed MD simulations of the synthetic peptidomimetic inhibitor, N3, bound to Mpro, based on the co-crystal structure 6LU7. The stability of the N3 ligand binding position is confirmed by MD simulation, and is shown in Supplementary Fig. S5. The stability of the N3 binding pose is entirely consistent with the experimentally-acquired co-crystal structure, and provides support for the validity of our MD simulation methodology to study stability of novel ligands binding to Mpro.

3.4. Synergistic compound CHA008 freely diffuses between the active site and putative allosteric sites on Mpro

All-atom, fully solvated MD simulations were performed on four complexes: Mpro-HQA004; Mpro-HQA004-CHA008, Mpro-HQA004-LQA003, and (for reference) Mpro-N3. Both the singly and doubly bound Mpro complexes exhibit overall conformational stability and retention of molecular dimensions comparable to that of apo Mpro (Supplementary Information S3, and Supplementary Figs. S6 and S7). The behaviors of the protein and ligands were computationally observed for 0.1 microseconds, followed by MM-PBSA calculations to quantify the binding free energy between the protein and ligands. We note that LQA003 remains apparently stably bound to its initial docking site throughout the trajectory (Fig. S8a). Far more interesting, however, is the behavior of CHA008, which exhibits a range of dynamics and diffusional motions, and is also more likely to be more effective as a synergistic ligand (see section 3.5 below). Therefore, first, we examined how CHA008 behaves and stabilizes the interaction between HQA004 and Mpro. We subsequently examined how CHA008 binding affected the structure and dynamics of Mpro, and therefore provided an explanation for the allosteric effects of CHA008 over HQA004-Mpro binding.

Our trajectories showed a persistent binding of HQA004 within the Mpro catalytic site proximal to the catalytic dyad, Cys145 and His41. Such binding behavior was observed in both complexes. However, the CHA008-bound system provided better structural stability for HQA004 in terms of its contact and interaction with Mpro. CHA008 was observed in our trajectories undergoing free diffusion across a pathway commencing from the catalytic site beside HQA004, to the back of Mpro to nest within a binding pocket proximal to residues Gln110, His246, Pro293 from 6100 ps onwards until the end of the trajectories (Fig. 3 a; Supplementally Video 1). Metastable contacts were formed between CHA008 and three Mpro residues at various points during the trajectory, which may be used to track this synergistic ligand’s progression. Initially, CHA008 formed close contacts with Ser1 and HQA004, as shown in the ligand-residue distance time series plot in Fig. 3b, and the 2D ligand interaction diagram in Fig. 3e. These contacts were severed after ∼20 ns, and new contacts were formed with Pro184 (Fig. 3c), which assumed the role of an intermediate site, persists between 20 and 60 ns. Thereafter, CHA008 established a tight salt bridge interaction with Asn203 from 60 ns until the end of the trajectory (Fig. 3d and f). Ser1, Pro184 and Asn203, therefore, constituted a triad of ‘checkpoint residues’ which facilitated the free diffusion of CHA008 between the active and allosteric sites (identified as ‘pocket 8′ by Weng et al. [73]). From the degree of stability of HQA004 that was observed to be distinct from the CHA008-free complex, it is assumed that CHA008 continued to influence the behavior of HQA004 despite its shift to pocket 8, indicating its possible role as an allosteric modulator. This binding site is yet to be studied extensively, and hence the exact allosteric mechanisms remain unclear. These possible mechanisms are explored in the following sections.

Fig. 3.

Simulated diffusion pathway of synergistic ligand CHA008. a) Multi-frame overlays for compound CHA008 from the initial synergistic docking position (red licorice representation) to the final stably-bound position (blue licorice representation), shown every 2 ns. Mpro is shown as light grey ribbons, with compound HQA004 as yellow spheres. b-d) Time series plots for minimum-contact distances between CHA008 and Ser1, Pro108, and Asn203 respectively. Graphical insets below the plots illustrate ligand positions. ‘Checkpoint’ residues on Mpro are shown as multicolored spheres. HQA004 is shown in yellow, and CHA008 is shown in light green. e-f) 2D ligand interaction diagrams are displayed for CHA008 bound at the initial docking-predicted site (e) and the final potential allosteric site (f).

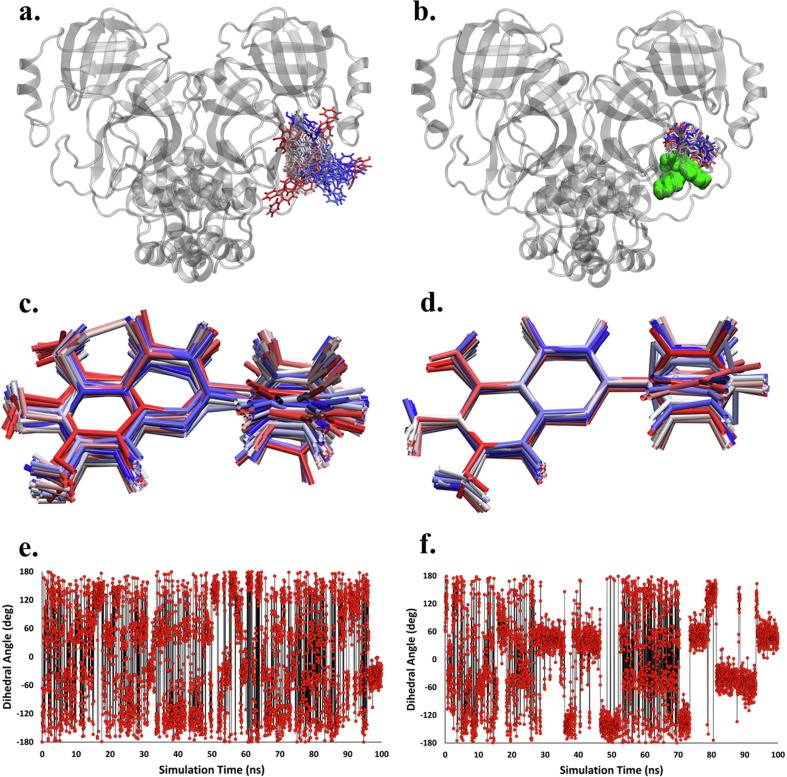

3.5. CHA008 stabilizes and strengthens active site binding by HQA004

The presence of CHA008 has a substantial impact on the tightness of binding and conformational flexibility of HQA004. In the absence of CHA008, HQA004 exhibited marked orientational shifts and positional fluctuations throughout the trajectory. It can be seen that the ligand dynamically occupied a relatively large volume of space around the active site pocket, with a span of approximately 30 Å (Fig. 4a). Additionally, the ligand exhibits substantial internal conformational flexibility, with its central C–C dihedral angle exhibiting frequent changes throughout the entire trajectory, as illustrated by the structural overlay (Fig. 4c) and the time series plot of the dihedral angle (Fig. 4e). In contrast, with CHA008 present, the ligand HQA004 exhibited far less positional changes, and the ligand occupied a small volume of space confined to the active site pocket when it was supported by the synergistic ligand, as illustrated in Fig. 4b (CHA008 shown as large green spheres). The ligand also exhibited far more limited internal conformational flexibility (Fig. 4d), and the central C–C dihedral rotation occurred in a discrete, stepwise manner (Fig. 4f; a similar behavior is exhibited for the HQA + LQA double bound complex, shown in Supplementary Fig. S8b and S8c), rather than via rapid inter-conversions observed for the CHA008-free complex (Fig. 4e). The higher structural stability of HQA004 was also observed in the trajectories of the system with CHA008 (Supplementary Video S1).

Fig. 4.

CHA008 promotes the conformational stability of HQA004. a-b) Multi-frame overlays for compound HQA004 from the initial docking pose (red licorice representation) to the final MD-simulated pose (blue licorice representation), shown every 2 ns. Mpro is shown as light grey ribbons, with compound CHA008 as light green spheres. Singly-bound HQA004-Mpro complex is shown in a), and doubly-bound HQA004-CHA008-Mpro complex is shown in b). c-d) Structurally-aligned multi-frame overlays for the HQA004 molecule within the c) singly-bound and d) doubly-bound Mpro complex. e-f) Time-series plots of the central C–C dihedral angle of HQA004 for e) singly-bound and f) doubly-bound Mpro complex.

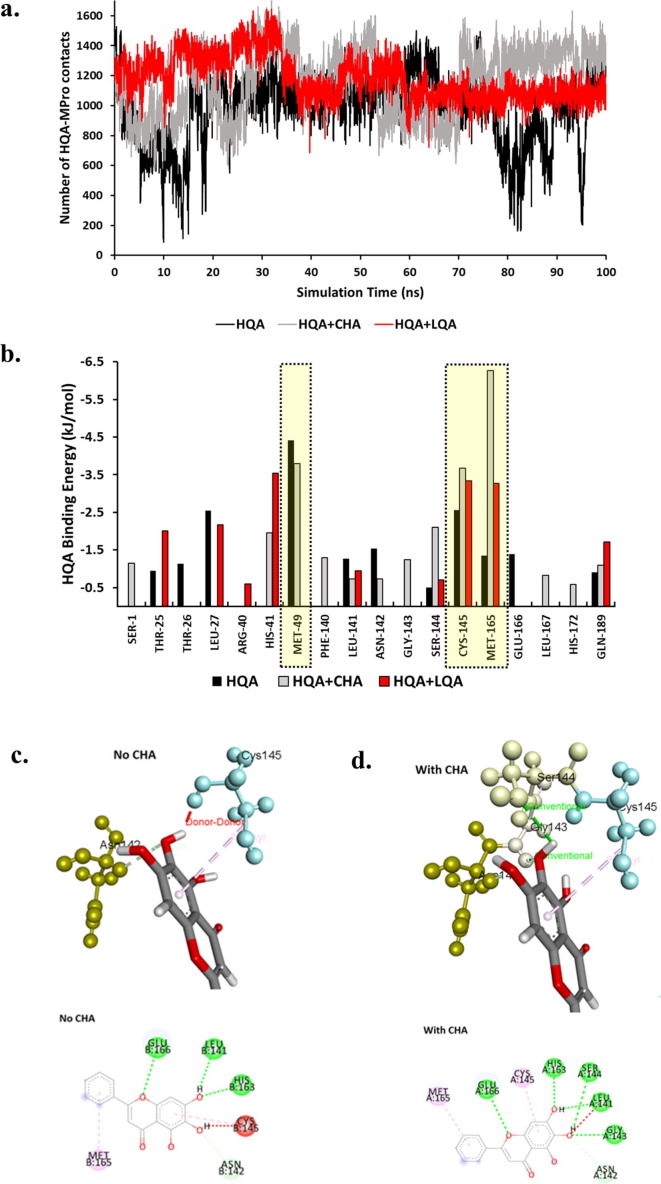

The presence of CHA008 enhanced the total number of contacts between HQA004 and Mpro (Fig. 5 a). It is interesting to note that LQA003 (red line) also promotes a higher number of contacts between HQA004 and Mpro, albeit to a far lesser extent compared to CHA008 (grey line), especially towards the end of the trajectory between 70 and 100 ns. In particular, HQA004 maintained close contact with Cys145 of Mpro, part of the catalytic dyad of Mpro, an important drug target for SARS-CoV-2 [44]. To further elucidate the impact of CHA008 on the binding between HQA004 and Mpro, free energy calculations using MM-PBSA were performed to estimate the extent of the contribution made by the synergistic ligand to the binding affinity between HQA004 and Mpro. The total binding affinity between Mpro and HQA004 was −42.5 kJ/mol for the CHA008-free complex whereas the complex bound with CHA008 resulted in a marginally higher affinity of −46.2 kJ/mol. In contrast, when doubly-bound with LQA003, the total binding affinity between Mpro and HQA004 is reduced to –32.9 kJ/mol, suggesting that although LQA003 remains in its initial docked position during the simulation and appears to stabilize (at least structurally) the internal conformation of HQA004 (Supplementary Fig. S8), it actually reduces the interaction energy between Mpro and HQA004, thereby possibly also reducing its inhibitory activity. Given the apparent weakness of LQA003 at enhancing the binding affinity of HQA004 to Mpro, therefore, the present work focuses on the detailed structural and biophysical analysis of CHA008 as a potential synergistic ligand which may serve as a support co-ligand to the main inhibitor, HQA004.

Fig. 5.

CHA008 promotes the binding affinity of HQA004. a) Time-series plot of the total number of inter-atomic contacts between HQA004 and Mpro for singly- (black) and doubly-bound Mpro with CHA008 (grey) or LQA003 (red). b) Per-residue binding free energy contribution of Mpro residues towards HQA004, calculated using MM-PBSA, for singly-bound (black bars) and doubly-bound Mpro with CHA008 (grey bars) or LQA003 (red bars). c-d) Graphical illustrations of the impact of CHA008 on specific contacts between HQA004 and the surrounding active site residues for the c) singly-bound and d) doubly-bound Mpro complex. HQA004 is shown in multicolored licorice format, while active site residues are shown as spheres-and-sticks, and color-coded according to residue name. 2D ligand interaction diagrams are inset underneath.

To explain the reason behind this difference in binding free energy, decompositions of the contributions of individual amino acids towards the total binding affinity of HQA004 to the active site were performed. Free energy decomposition graphs are shown for the HQA004 and doubly bound (Fig. 5b) complexes. The catalytic site residue Cys145 is amongst the few residues contributing the most favorable free energy towards the binding, consistent with the close contact observed in the 2D ligand interaction diagram (Fig. 2b). The close contact was maintained better in the complex with CHA008 as evident in the greater final binding affinity value between Cys145 and HQA004 being −3.7 kJ/mol, compared to a marginally lower affinity of −2.56 kJ/mol being predicted when CHA008 was absent. The closer proximity to Mpro and the conformational stability of HQA004, achieved by the presence of CHA008, maybe the factors contributing to its ability to recruit and bind to two nearby residues, Gly143 (contribution value −1.2 kJ/mol) and Ser144 (−2.1 kJ/mol) (Fig. 5c) in which residues bind to oxygen-hydrogen bonds of HQA004 and enabled its rotation away from Cys145 to mitigate the atomic clash (such a clash is observed in the system absent of CHA008), hence further contributing to the overall interaction stability between Mpro and HQA004 (Fig. 5d, bottom panel). Additionally, HQA004 in the CHA008-bound complex bonded strongly to a wider range of residues, including His41, another catalytic dyad residue. In contrast, for the LQA003-bound complex, several residues no longer make substantial contributions to HQA004-binding. For example, Met49 loses the capability to contribute to HQA004′s binding free energy when LQA003 is present (Fig. 5b, indicated by the yellow box; note the absence of the ‘red bar’). Further, LQA003 only weakly promotes free energy contribution by the key residue Met145 (Fig. 5b, second yellow box) compared to CHA008. The reduction or total loss of interaction between HQA004 and several key active-site residues of Mpro, as a result of LQA003 co-binding, explains the weaker total binding affinity of HQA induced by LQA, providing further support for the relative importance of CHA008 as a potential, far more important synergistic ligand.

3.6. CHA008 is synergistically coupled to HQA004 via a see-saw mechanism

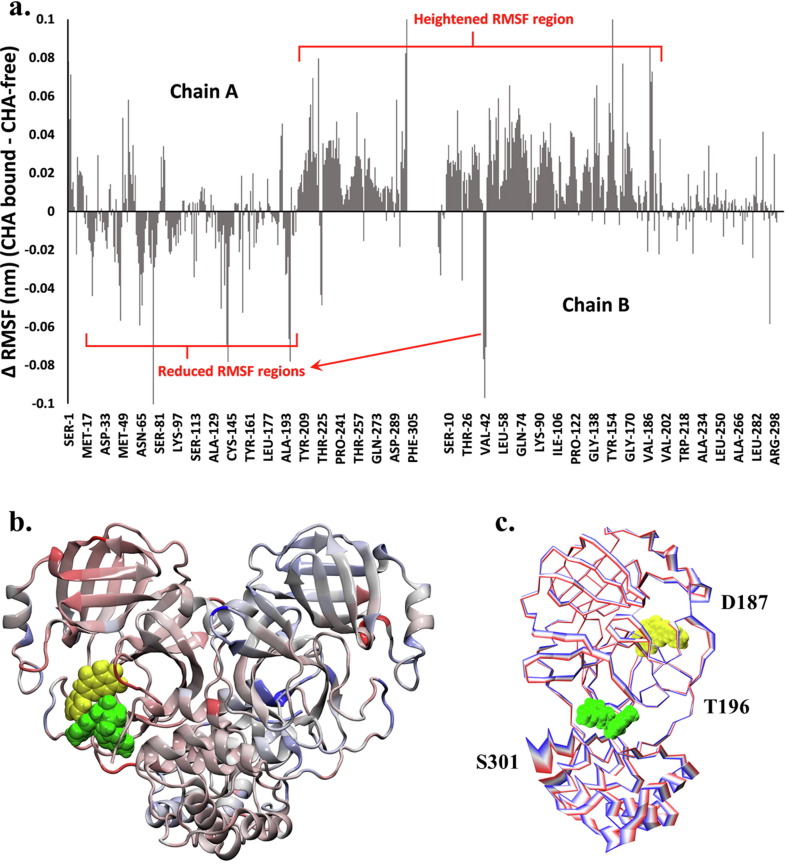

The residue-based root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) was used to analyze the flexibility of the residues of Mpro over the trajectories. The calculation was performed separately for Chain A and Chain B of Mpro for both complexes. Tyr154 and Arg222 in Chain A and Gln189 in Chain B have shown greater flexibility in the CHA008-bound complex when compared with the complex without CHA008 (Fig. 6 a). We note that the residue Arg222 from the CHA008-bound complex (0.3842 nm) showed a similar degree of flexibility to the one from Mpro apo form (0.3851 nm), while the flexibility only reached 0.2588 nm in the CHA008-free complex. The addition of CHA008 induced a clear pattern of change in residue fluctuation relative to the HQA004-only complex. Fig. 6a shows the suppression of RMSF in the N-terminal segment comprising residues Ser1 to Leu205 of chain A, but an increase in RMSF at the C-terminal segment of chain A comprising residues Leu205 to Glu290, as well as the N-terminal segment of chain B comprising residues Glu14 to Thr201 (in contrast when LQA003 is bound, only Chain A is impacted in terms of reduction in RMSF, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S9. Thus, the impact of LQA003 is localized only to the immediate vicinity of its binding location). This uneven impact of CHA008 co-binding on the RMSF, illustrated by the color-coded ribbon structure in Fig. 6b, strongly suggests that CHA008 binding not only has an immediate impact on RMSF in the region of the monomer to which it is bound, but that its influence extends throughout the dimeric Mpro, hinting at a possible mechanism which couples the HQA004-bound active site (residues around Cys145) with that of the allosteric ‘pocket 8′ (residues around Asn203).

Fig. 6.

Proposed allosteric mechanism of CHA008. a) Per-residue differences in root-mean-square-fluctuation (ΔRMSF) for doubly-bound Mpro relative to singly-bound Mpro, with negative values indicating enhanced stability due to CHA008 synergistic binding, and vice versa. b) Mpro shown in ribbon representation, with segments color-coded according to ΔRMSF value using a scheme comprising red (lowest ΔRMSF), white (intermediate ΔRMSF), and blue (highest ΔRMSF). HQA004 is shown as yellow spheres, with CHA008 as green spheres. c) Multi-frame overlays of the Cα trace of the first principal component (vibrational mode) of the doubly-bound Mpro complex, color-coded using a red-white-blue scheme to represent concerted motions.

To determine possible dynamic pathways connecting these two CHA008-binding sites, the trajectories were further examined using vibrational mode analysis. An overlay of the backbone structure extracted from the first vibrational mode of Mpro for the CHA008-bound trajectory (Fig. 6c). Regions that undergo concerted, large-scale motions are shown as broad, multi-colored stripes. It may be seen that the HQA004-bound region (yellow spheres), comprising Asp187 to Gln192, moved in tandem with the CHA008 site (green spheres) comprising Thr291 to Ser301. These two regions were linked via a stationary hinge point centered at Thr196 which acted as a fulcrum, enabling a see-saw-like tipping motion between the two binding sites. Thus, vibrational analysis suggests one mechanism by which CHA008 binding may influence HQA004, as these two regions were dynamically coupled.

Wavelet analysis was performed on residue sequential data derived from differences in RMSF (△RMSF), shown in Fig. 7 a. Furthermore, we calculated the residue contact order at each residue for both complexes, which measures the total number of residues surrounding each residue in Mpro, and serves as a proxy for the compactness of intramolecular interactions throughout the sequence. Subsequently, the △RCO for each residue was calculated in a similar manner as △RMSF. A wavelet power spectrum for △RCO is shown in Fig. 7b. Together, wavelet power spectra for △RMSF and △RCO facilitated extraction of further subtle details of the impact of synergistic ligand binding on the dynamics and intramolecular contacts of Mpro. More specifically, wavelet power spectra enables the identification of possible periodic behavior in dynamics or residue contacts at each position by estimating the contributions of different periodic functions with a range of frequencies.

Fig. 7.

Wavelet power spectra for the ligand-bound chain A of Mpro, calculated for △RMSF (a) and △RCO (b), where the differences were calculated at each residue by subtracting the RMSF/RCO value obtained for the singly-bound (CHA-free) from that of the doubly-bound (CHA bound) complex. The black contours show a 10% significance level, and the color code reflects the strength of the spectrum, ranging from blue (low power) to red (high power). Regions of special interest described in the manuscript text are indicated by the dashed box.

The wavelet power spectrum of △RMSF (Fig. 7a) indicates that numerous short segments of Mpro exhibited short-range changes to RMSF as a result of synergistic binding of CHA008, as shown by regions of high wavelet power for low period (high frequency) oscillations of approximately 4–8 residues in length. Higher period (lower frequency) oscillations with periods of up to 32 residues were observed at residues 50–100, and between residues 170–250. This pattern of separation in regions of high wavelet power suggested that changes in RMSF due to the additional binding of CHA008 were localized to discrete segments of Mpro, with the impact extending no further than approximately 32 residues within each segment.

In contrast, the wavelet power spectrum of △RCO (Fig. 7b) indicates that very broad segments of Mpro exhibited long-range changes to inter-residue contacts as a result of synergistic binding of CHA008, as shown by extended regions of high wavelet power for high period (low frequency) oscillations of approximately 32 residues in length, and even more prominently at residues 100–250. This pattern of contiguous regions of high wavelet power suggested that changes in intramolecular residue contact due to the additional binding of CHA008 were broad, and cause widespread changes in protein compactness across the entire protein chain. The regions of the particularly stark contrast between △RMSF and △RCO were indicated by dashed boxes in Fig. 7.

Therefore, while synergistic binding of CHA008 appeared to promote isolated, short segments to undergo concerted reductions in △RMSF (Fig. 7a), its effect appeared to be the opposite for △RCO, where synergistic binding promotes broad, widespread propagation of changes in inter-residue contacts (Fig. 7b). This suggested that the fragmentation of concerted dynamical motions into short discrete segments was associated with the disruption of inter-residue contacts over a broad segment of the Mpro sequence.

4. Discussion

The ‘one drug, one target, one disease’ approach has for some time remained the conventional pharmaceutical approach to the development of medicines and treatment strategies [35]. However, over the last decade, this mono-substance therapy model has gradually shifted towards the adoption of combination therapies, in which multiple active components are employed. This paradigm shift has been partly driven by the limited effectiveness of monotherapy in treating chronic diseases, the emergence of treatment resistance, and the side effects of synthetic mono-drugs [74]. Recent evidence has demonstrated the greater benefits of combination therapy for diseases with complex etiology and pathophysiology such as acquired immune deficiency syndrome, cancer, atherosclerosis and diabetes, which are normally difficult to treat by the single drug target approach [75], [76]. With regards to COVID-19, a clear successful example of the combination therapy is indeed Pfizer’s paxlovid, in which the main ingredient, nirmatrelvir, is boosted by ritonavir, and co-packaged for oral use for the treatment of mild-to-moderate COVID-19 in adults as well as children who are at high risk for severe diseases and have positive direct test results for SARS-CoV-2 [77]. Therefore, paxlovid provides an exemplary paradigm of the effectiveness of synergy.

Synergy is also a core concept within Chinese herbal medicine practice, an important part of primary health care in Asian countries which has utilized complex herbal formulations (consisting of two or more medicinal herbs) to treat diseases for thousands of years. The general assumption is that the synergistic therapeutic effects of Chinese herbal formulations derive from the complex interactions between the multiple bioactive components within the herbs and/or herbal formulations. However, evidence to support these synergistic effects remains weak and controversial due to several reasons, including the very complex nature of Chinese herbal medicine, misconceptions about synergy and methodological challenges to the study design [78].

At the molecular level, synergy may occur by allostery. For example, allosteric crosstalk in chromatin can mediate drug-drug synergy, and previous work investigated whether the interplay between Nef's flexible regions and its core domain could allosterically influence ligand selection. It was found that the flexible regions can associate with the core domain in different ways, producing distinct conformational states that alter the way in which Nef selects for SH3 domains and exposes some of its binding motifs. The ensuing crosstalk between ligands might promote functionally coherent Nef-bound protein ensembles by synergizing certain subsets of ligands while excluding others [79].

Our present study aimed to explore the synergy within herbal compounds from the TQG, the recommended Chinese herbal remedy for COVID-19 treatment. Due to the complex nature of the synergy study, we used a comprehensive approach including multi-ligand molecular docking, simulation, free energy calculations and wavelet analysis for this study. Our computational modeling indicated that HQA004 (baicalein) is a strong binder of Mpro while CHA008 (cubebin) could serve as a synergistic compound by binding near HQA004. CHA008 binds at two possible sites and may freely diffuse between the two via a number of checkpoints. CHA008 stabilizes the conformation and binding location of HQA004 while it also increases the number of favorable HQA004-Mpro contacts. CHA008, at pocket 8, can influence the dynamics of HQA004 at pocket 1, via coupled motions between the two sites facilitated by a hinge point along the β-strand composed of residues Thr190 to Ile200. Therefore, CHA008 can act synergistically even when not bound directly near HQA004, akin to being an allosteric compound. Further, our novel wavelet power spectrum analysis elucidated more subtle changes in both the dynamics and structure of Mpro as a result of CHA008 binding, suggesting that the synergistic ligand may disrupt inter-residue contact across a wide swarth of the protein while modulating the fluctuations of individual residues in a more localized, targeted manner. Such a synergistic mechanism of interaction between multiple ligands has not been extensively studied so far; all the known potential inhibitors of Mpro including phytochemicals previously studied have been a single compound and interacted mostly with the catalytic dyad His41 and Cys145 [80].

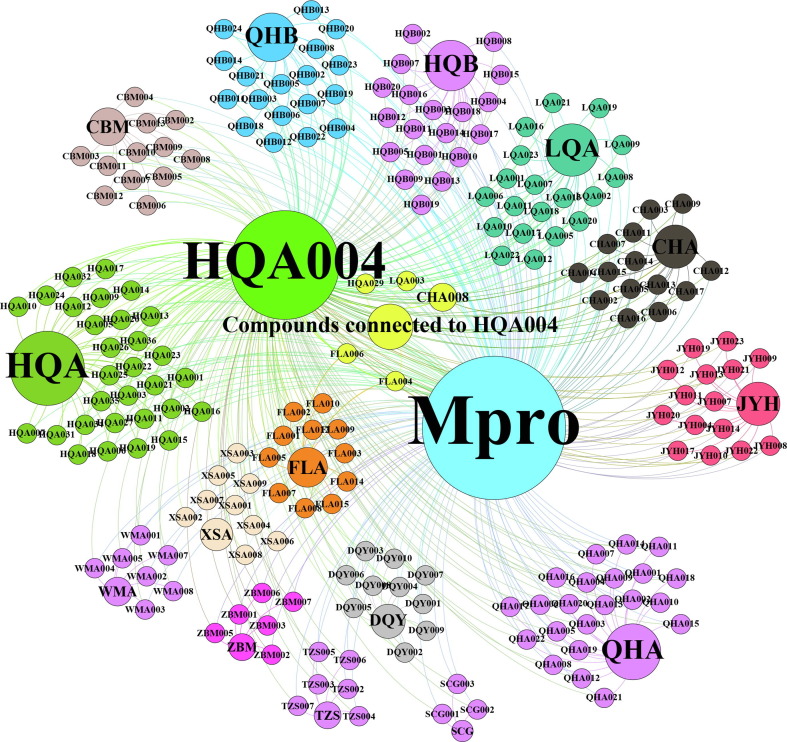

We further generated a synergistic mechanism network for the TQG compounds (Fig. 8 ). According to the network based on the collection of previous in silico and in vitro studies, HQA004 was the only known inhibitor of Mpro among all the herbal compounds from the TQG, confirming its fundamental role in the synergistic network of the TQG. The network also indicated that 206 herbal compounds, accounting for 86.55% of all the identified components in TQG, may produce synergistic effects with HQA004. Further studies are warranted to explore their synergistic interactions with HQA004 and their contribution to the overall inhibitory action. The result from the network analysis reinforces the benefit of using multiple herbs (‘holistic medicine’) as a remedy rather than a single herb or mono-compound, because the presence of numerous compounds can promote synergism and allosteric crosstalk amongst the compounds to deliver superior therapeutic effects. Detailed information for the network is shown in Supplementary Information S4.

Fig. 8.

Synergistic mechanism network model between HQA004 and other 206 compounds from Toujie Quwen Granules. For corresponding herbal names, please refer to Table 1; Corresponding compound names were presented in Supplementary Table S2.

Our computational work has demonstrated the mechanisms of synergistic interactions between two herbal compounds that worked together to amplify the inhibition of Mpro, while encouraging further research to explore similar synergistic actions for other compounds that exist in the TQG remedy. Our work is albeit disadvantaged by a few shortfalls that computational methods commonly encounter, such as calculation inaccuracies as well as result discrepancies when the compounds proceed to laboratory experiments including in vitro and in vivo studies. The high binding affinity values and favorable molecular behaviors do not always equate with desired biological effects. The inhibitory effect of baicalein upon Mpro has previously been studied in vitro by another research group [67]. They experimented with SARS-CoV-2 infected Vero CCL-81 cells and demonstrated the antiviral activity of baicalein being superior to many of the previous studies compounds and the antiviral effect was close to the one of chloroquine and remdesivir. The expression of Mpro was restricted by baicalein at IC50 of 0.39 µM, and viral replication was inhibited at EC50 of 2.9 µM [67]. They also carried out X-ray crystallography to analyze the crystal structure of baicalein bound Mpro complex at a resolution of 2.2 Å and determined a couple of key residues that interacted with the ligand [81]. Many of these key residues including Cys44, Met49, Leu141, Asn142, Ser144, Met165, Glu166, and Gln189 were also the highly contributing residues found from our residue contribution analysis by MM-PBSA. Another in vitro study by FRET-based protease assay has also shown that baicalein significantly restricts the expression of Mpro at IC50 of 0.94 µM, and inhibits the viral replication at EC50 2.94 µM [66]. Further laboratory experiments are indeed warranted to further verify the therapeutic effects and safety of the compound. And finally, it should be noted that synergistic effects may not only focus on one drug target, but also target multiple proteins in the human body. Nonetheless, our comprehensive approach did provide a solution for the discovery of synergistic candidates for novel combination drugs focusing on the same target. In the future, artificial intelligence and machine learning, based on our data sample, could be used to thoroughly investigate the synergistic effects of compounds from a herbal formula.

5. Conclusions

In our study, we selected TQG for Mpro of SARS-CoV-2 as an example, using multi-ligand molecular docking, simulation, free energy calculations and wavelet analysis to identify potential compounds with synergic effects from a Chinese herbal remedy, revealing that it is an innovative pathway for novel combination drug discovery. The screening of TQG herbal compounds showed HQA004 to be the most favorable active site binding ligand of Mpro and it interacted with CHA008 in synergy. By interacting with CHA008, HQA004 achieved higher structural stability by reducing its conformational flexibility, increasing the number of overall residue interactions with Mpro, and forming more favorable contacts with certain residues. The synergistic interaction moreover induced an unusual residue fluctuation across the dimeric Mpro as influenced by CHA008, suggesting its role as an allosteric modulator. The tandem and see-saw-like tipping motion observed between HQA004 bound site and that of CHA008 further endorsed the idea of such allostery. Additionally, our novel wavelet power spectrum analysis indicated that as a result of CHA008 binding, the dynamics and structure of Mpro were observed to have more subtle changes, demonstrating that the inter-residue contacts within Mpro were disrupted by the synergistic ligand. Our work demonstrated through computational molecular modeling and network method the synergy that exists between two compounds, exerting a concerted effort to inhibit Mpro. This work invites further studies that aim to uncover the mechanisms of synergy within complex multi-compound herbal medicine that may be potential candidates for novel combination drugs, as well as experimental studies including enzyme assays to validate the therapeutic effects and safety of such regimens.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are included in the paper and/or its supplementary information files.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China [grant numbers 2020YFC2003100, 2020YFC2003101], Key Project of National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 81830117], National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 8220140209], Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation [grant numbers 2021A1515110082, 2019A1515010400], China Postdoctoral Science Foundation [grant number 2022M711534], and Science & Technical Plan of Guangzhou, Guangdong, China [grant number 201903010069].

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Hong Li: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization, Funding acquisition. Akari Komori: Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization. Mingdi Li: Software, Validation, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing. Xiaomei Chen: Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing. Angela Wei Hong Yang: Methodology, Validation, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision. Xiaomin Sun: Methodology, Validation, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision. Yanyan Liu: Methodology, Validation, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Andrew Hung: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration. Xiaoshan Zhao: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition. Lin Zhou: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Investigation, Resources, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Computational Infrastructure (NCI), which is supported by the Australian Government, and the Pawsey Supercomputing Centre, which is supported by the Western Australian Government and the Australian Government, and the University of Melbourne Research Computing Services facilities, for providing resources and services to enable the computational work in this study. We also thank Ms Manlin Peng, who provided copyediting and proofreading voluntary services.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molliq.2023.121253.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are included in the paper and/or its supplementary information files.

References

- 1.Collier R. Reducing the “pill burden”. CMAJ. 2012;184:E117. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-4076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wen W., Chen C., Tang J., Wang C., Zhou M., Cheng Y., Zhou X., Wu Q., Zhang X., Feng Z., Wang M., Mao Q. Efficacy and safety of three new oral antiviral treatment (molnupiravir, fluvoxamine and Paxlovid) for COVID-19:a meta-analysis. Ann. Med. 2022;54:516. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2022.2034936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curran M.P. Amlodipine/atorvastatin: a review of its use in the treatment of hypertension and dyslipidaemia and the prevention of cardiovascular disease. Drugs. 2012;70:191. doi: 10.2165/11204420-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diener H.C., Jansen J.P., Reches A., Pascual J., Pitei D., Steiner T.J. Efficacy, tolerability and safety of oral eletriptan and ergotamine plus caffeine (Cafergot) in the acute treatment of migraine: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison. Eur. Neurol. 2002;47:99. doi: 10.1159/000047960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sun W., Sanderson P.E., Zheng W. Drug combination therapy increases successful drug repositioning. Drug Discov. Today. 2016;21:1189. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2016.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li C., Jia W.-W., Yang J.-L., Cheng C., Olaleye O.E. Multi-compound and drug-combination pharmacokinetic research on Chinese herbal medicines. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2022:1. doi: 10.1038/s41401-022-00983-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chou T.C. Theoretical basis, experimental design, and computerized simulation of synergism and antagonism in drug combination studies. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006;58:621. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cucinotta D., Vanelli M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020;91:157. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng J. SARS-CoV-2: an emerging coronavirus that causes a global threat. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020;16:1678. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.45053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watson O.J., Barnsley G., Toor J., Hogan A.B., Winskill P., Ghani A.C. Global impact of the first year of COVID-19 vaccination: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2022;22:1293. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(22)00320-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]