Abstract

The infectivities of 66 Listeria monocytogenes isolates were assessed by intragastric inoculation of mice. Eight were poorly infective. Serovars 4b and 1/2 were more infective than serovars 3 and 4nonb. A noninfective isolate was cleared more rapidly from the cecum than were infective isolates, suggesting that survival in the gut may relate to infectivity.

Although Listeria monocytogenes is a foodborne pathogen and is relatively common in foods (7, 16, 30), human infections are rare. Reasons include host susceptibility and dose, but little is known about how L. monocytogenes causes disease or whether all isolates are equally infective via the oral route in humans.

Virulent isolates are hemolytic, with the hemolysin (5) enabling bacteria to escape from phagolysosomes; however, even hemolytic isolates vary in virulence for mice (11, 29), and additional virulence genes have been identified (23, 25). Most studies of virulence have used intravenous (i.v.) or intraperitoneal routes of inoculation of mice or cell culture models to assess the behavior of wild-type, laboratory, or genetically manipulated strains (4, 8, 11, 19, 28). Yet the ability of L. monocytogenes to survive in the gastrointestinal tract and invade through the mucosa may be limiting factors for natural infection and require virulence factors different from those necessary for survival and growth in the reticuloendothelial system or for invasion and multiplication within cells in vitro.

The behavior of L. monocytogenes in mice following intragastric (i.g.) inoculation has been studied previously (1, 14, 24), but the number of isolates examined has been small. This note reports on a study of the infectivity of 66 phenotypically characteristic smooth hemolytic isolates from different sources and belonging to a range of serovars following i.g. inoculation into immunocompetent mice. In a preliminary experiment, growth curves were determined for specially selected isolates to establish that differences in infectivity could be detected by i.g. inoculation and to choose the best time to screen for infectivity for a large number of isolates.

Preliminary in vivo growth curves.

Methods for preparation of mouse-passaged log phase cultures, i.g. inoculation of BALB/c mice, and viable bacterial counts in liver and spleen have been described previously (2). Cecal contents were also removed and weighed, dilutions performed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and viable counts were performed on PALCAM agar plates (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom), which were incubated for 48 h at 30°C.

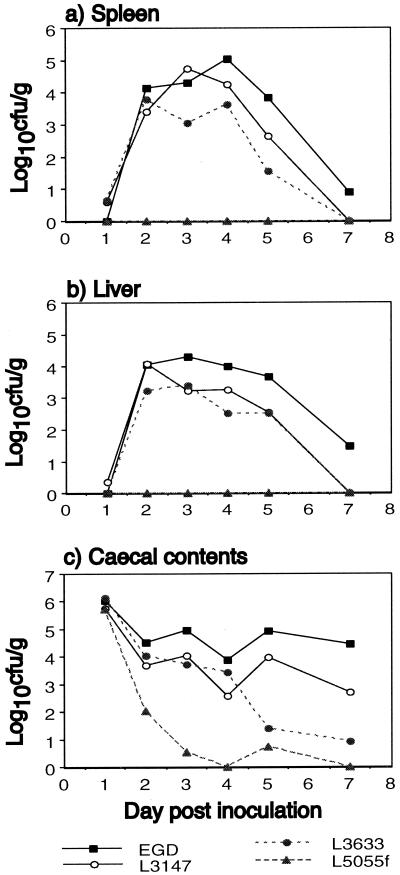

Growth curves (Fig. 1) demonstrated that selected isolates of L. monocytogenes (the mouse-virulent EGD [serovar 1/2a] [13], nonvirulent L5055f [1/2a] [29], clinical isolate L3147 [4bX], and L3633 [3c] from food) varied in their ability to translocate from the gut and grow in liver and spleen following i.g. inoculation of 2 × 109 CFU. Maximum levels were reached in liver and spleen over 2 to 4 days postinoculation. Thereafter, numbers declined, with bacteria being mostly cleared by day 7. Infective isolates cleared from the cecum over the course of 7 to 14 days. L5055f was not detected in the liver or spleen at any time and was cleared more rapidly from the cecal contents. Listeria ivanovii NCTC 11846 and Listeria innocua NCTC 11288 were also investigated as representatives of these species. L. innocua was not isolated by direct culture from any spleens or livers. L. ivanovii was detected (< 100 CFU/g) in the liver of one mouse only on day 4. L. innocua was cleared rapidly from the cecal contents, but interestingly, L. ivanovii persisted at high levels (106 to 107 CFU/g) for 5 days (not shown).

FIG. 1.

Viable bacterial counts in spleen (a), liver (b), and cecal contents (c) of mice inoculated i.g. with 2 × 109 CFU of selected isolates of L. monocytogenes. Each point represents the mean of the log10s of the viable count per gram of tissue for three mice on days 1 to 4 and two mice on days 5 and 7.

Screening experiments.

The infectivities of 66 L. monocytogenes isolates of different serovars from different sources were then assessed. Each serovar group included both clinical and food isolates except 4nonb, for which no clinical isolates were available. Four groups also contained environmental isolates. Three mice were inoculated i.g. with 2 × 109 CFU, and viable bacterial counts in spleen and liver were determined 3 days later, as described previously (2). The means of the log10s of the viable counts were then calculated. Isolates with a mean of <103 CFU in the spleen and/or liver were arbitrarily defined as being poorly infective. Many experiments were repeated at least once to confirm results.

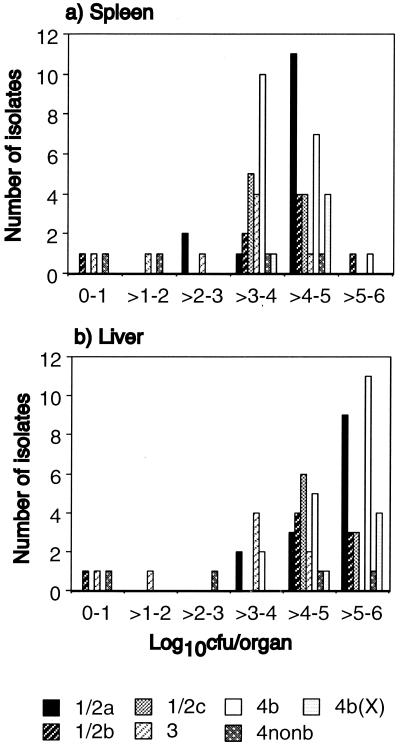

Isolates demonstrated a wide variation in infectivity (Fig. 2). The majority were of intermediate or high infectivity, with 103 to 106 CFU being recovered from the spleen and liver. Eight isolates (12%) were poorly infective, and one of these, a food isolate of serovar 1/2b, was not recovered from any livers or spleens.

FIG. 2.

Infectivities of 66 isolates of L. monocytogenes, grouped by serovar, assessed by viable bacterial counts in spleen (a) and liver (b) 3 days following i.g. inoculation with 2 × 109 CFU. Results are expressed as the means of the log10s of the viable counts per organ from three mice per isolate grouped in 1-log intervals.

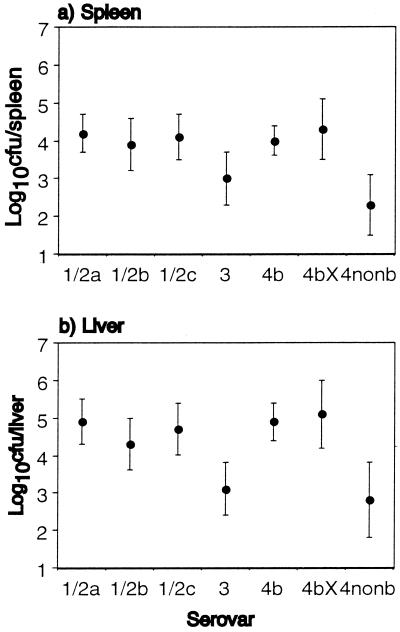

Isolates of serovar 4b cause most outbreaks of listeriosis and at least as many sporadic infections as isolates of serovar 1/2 (3, 6, 9, 12, 18, 26), despite being found less commonly in foods (10, 20, 21, 22, 27), which suggests that serovar 4b is more virulent. In our study, no isolate from serovars 1/2c (9 isolates), 4b (18 isolates), and 4b(X) (5 isolates) was poorly infective. Three of 8 isolates of serovar 3, 2 of 4 isolates of 4nonb, 2 of 14 isolates of 1/2a, and 1 of 8 isolates of 1/2b were poorly infective (Fig. 2). The proportions of poorly infective isolates of serovar 4b (0 of 18) and 1/2a, 1/2b, and 1/2c combined (3 of 31) were not significantly different at the 95% level by Fisher's exact probability test, nor were proportions of poorly infective food (excluding clinical and environmental) isolates only (0 of 7 for 4b and 3 of 14 for 1/2). Figure 3 shows the mean of the results for each serovar. The mean infectivities of serovars 4b, 1/2a, 1/2b, and 1/2c were comparable. Serovars 3 and 4nonb were the least infective. Serovar 4b(X) showed the greatest infectivity overall. This difference in mean infectivity between the seven serovars was significant at the 95% level, even after controlling for source (analysis of variance and Kruskal-Wallis test), the significance being accounted for by the low average infectivity of serovars 3 and 4nonb.

FIG. 3.

The average (mean) infectivity of the different serovars of L. monocytogenes assessed by viable bacterial counts in spleen (a) and liver (b) 3 days following i.g. inoculation with 2 × 109 CFU. The graph shows the mean of results from each serovar expressed as log10 CFU per organ ± 95% confidence interval (error bars).

While fewer isolates of serovar 4b were poorly infective compared to serovar 1/2, a significantly higher level of virulence of serovar 4b over 1/2, either in the proportion of poorly infective isolates or average infectivity across the serovar, was not demonstrated. However, factors not tested in this model, such as growth and expression of virulence factors under natural conditions and in the human gastrointestinal tract, may differ between these serovars and confer an advantage to serovar 4b in causing natural human infection. Serovars 4b and 1/2, commonest in human infection were, however, significantly more infective than 3 and 4nonb. The isolates of serovar 4b(X) were associated with an outbreak in England and Wales in 1987 to 1989 (15, 17). These were probably closely related or the same strain, resulting in a falsely high average level of virulence for this serovar. The relative proportions of isolates from the different serovars were not chosen to correlate with those occurring naturally in foods; thus, it is not possible to estimate the proportion of naturally occurring food and environmental isolates that are likely to be poorly infective for humans.

One might expect clinical isolates to represent the most infective end of the spectrum. One (serovar 3 from a blood culture) of 23 (4%) clinical isolates and 7 of 43 (16%) food and environmental isolates were poorly infective. Other clinical isolates were not all at the most infective end of the range, but the mean infectivity of the clinical isolates was higher than that of the food and environmental isolates combined. These differences, however, were not statistically significant at the 95% level (chi-square, analysis of variance, and Kruskal-Wallis tests). The poor infectivity of the clinical isolate was confirmed by more-detailed experiments (2). Irreversible changes in virulence may have taken place during storage. Alternatively, perhaps any isolate can cause disease providing that the dose is sufficiently high, the gastrointestinal conditions are optimal, and/or the patient is sufficiently immunocompromised.

The validity of the results obtained by screening was confirmed by determining in vivo growth curves of five isolates representing a range of infectivity. The results of three have been published previously (2).

Two other studies (4, 29) examined the virulence of a large number of wild-type L. monocytogenes isolates following intraperitoneal inoculation of immunocompromised mice, with death used as an end point. However, these only demonstrated two groups, pathogenic and nonpathogenic. Our study with a more natural route of infection demonstrated a range of infectivity. We have also compared infectivity by i.g. versus i.v. inoculation (2) and shown that some isolates that were moderately virulent for mice by i.v. inoculation were poorly infective via the i.g. route. Poorly infective isolates may be less well adapted for survival in the gastrointestinal contents, as demonstrated here with L. monocytogenes L5055f, or for translocation across the gastrointestinal mucosa.

We have found that i.g. inoculation of normal immunocompetent mice is a useful model for detecting poorly infective isolates of L. monocytogenes.

REFERENCES

- 1.Audurier A, Pardon P, Marly J, Lantier F. Experimental infection of mice with Listeria monocytogenes and Listeria innocua. Ann Microbiol (Inst Pasteur) 1980;131B:47–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbour A H, Rampling A, Hormaeche C E. Comparison of the infectivity of isolates of Listeria monocytogenes following intragastric and intravenous inoculation in mice. Microb Pathog. 1996;20:247–253. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1996.0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bille J. Epidemiology of listeriosis in Europe with special reference to the Swiss outbreak. In: Miller A, Smith J L, Somkuti G A, editors. Foodborne listeriosis. New York, N.Y: Elsevier Science Publishers, Inc.; 1990. pp. 71–74. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conner D E, Scott V N, Sumner S S, Bernard D T. Pathogenicity of foodborne, environmental and clinical isolates of Listeria monocytogenes in mice. J Food Sci. 1989;54:1553–1556. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cossart P, Vicente M F, Mengaud J, Baquero F, Perez-Diaz J C, Berche P. Listeriolysin O is essential for virulence of Listeria monocytogenes: direct evidence obtained by gene complementation. Infect Immun. 1989;57:3629–3636. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.11.3629-3636.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farber J M, Peterkin P I. Listeria monocytogenes, a foodborne pathogen. Microbiol Rev. 1991;55:476–511. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.3.476-511.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farber J M, Sanders G W, Johnston M A. A survey of various foods for the presence of Listeria species. J Food Protect. 1989;52:456–458. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-52.7.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaillard J L, Berche P, Mounier I, Richard S, Sansonetti P. In vitro model of penetration and intracellular growth of Listeria monocytogenes in the human enterocyte-like cell line Caco-2. Infect Immun. 1987;55:2822–2829. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.11.2822-2829.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goulet V, Rocourt J, Rebiere I, Jacquet C, Moyse C, Dehaumont P, Salvat G, Veit P. Listeriosis outbreak associated with the consumption of rilletes in France in 1993. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:155–160. doi: 10.1086/513814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heisick J E, Wagner D E, Nierman M L, Peeler J T. Listeria spp. found on fresh market produce. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1989;55:1925–1927. doi: 10.1128/aem.55.8.1925-1927.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hof H, Hefner P. Pathogenicity of Listeria monocytogenes in comparison to other Listeria species. Infection. 1988;16(Suppl. 2):S141–144. doi: 10.1007/BF01639737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linnan M J, Mascola L, Xiao Dong Lou, Goulet V, May S, Salminen C, Hird D W, Yonekura M L, Hayes P, Weaver R, Audurier A, Plikaytis B D, Fannin S L, Kleks A, Broome C V. Epidemic listeriosis associated with Mexican-style cheese. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:823–828. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198809293191303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mackaness G B. Cellular resistance to infection. J Exp Med. 1962;116:381–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marco A J, Altimira J, Prats N, Lopez S, Dominguez L, Domingo M, Briones V. Penetration of Listeria monocytogenes in mice infected by the oral route. Microb Pathog. 1997;23:255–263. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1997.0144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McLauchlin J, Crofts N, Campbell D M. A possible outbreak of listeriosis caused by an unusual strain of Listeria monocytogenes. J Infect. 1989;18:179–187. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(89)91290-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McLauchlin J, Gilbert R J. Listeria in food. Report from the PHLS Committee on Listeria and Listeriosis. PHLS Microbiol Digest. 1990;7:54–55. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLauchlin J, Hall S M, Velani S K, Gilbert R J. Human listeriosis and pate: a possible association. Br Med J. 1991;303:773–775. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6805.773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McLauchlin J. Distribution of serovars of Listeria monocytogenes isolated from different categories of patients with listeriosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1990;9:210–213. doi: 10.1007/BF01963840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nair S, Frehel C, Nguyen L, Escuyer V, Berche P. ClpE, a novel member of the HSP100 family, is involved in cell division and virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:185–196. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pini P N, Gilbert R J. The occurrence in the U.K. of Listeria species in raw chickens and soft cheeses. Int J Food Microbiol. 1988;6:317–326. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(88)90025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pinner R W, Schuchat A, Swaminathan B, Hayes P S, Deaver K A, Weaver R E, Plikaytis B D, Reeves M, Broome C V, Wenger J D the Listeria Study Group. Role of foods in sporadic listeriosis. II. Microbiologic and epidemiologic investigation. J Am Med Assoc. 1992;267:2046–2050. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pinto B, Reali D. Prevalence of Listeria monocytogenes and other listerias in Italian-made soft cheeses. Zentbl Hyg Umweltmed. 1996;199:60–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Portnoy D A, Chakraborty T, Goebel W, Cossart P. Molecular determinants of Listeria monocytogenes pathogenesis. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1263–1267. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.4.1263-1267.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roll J T, Czuprynski C J. Hemolysin is required for extraintestinal dissemination of Listeria monocytogenes in intragastrically inoculated mice. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3147–3150. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.9.3147-3150.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rouquette C, Berche P. The pathogenesis of infection by Listeria monocytogenes. Microbiologia. 1996;12:245–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schlech W F, III, Lavigne P M, Bortolussi R A, Allen A C, Haldane E V, Wort A J, Hightower A W, Johnson S E, King S H, Nicholls E S, Broome C V. Epidemic listeriosis-evidence for transmission by food. N Engl J Med. 1983;308:203–206. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198301273080407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schönberg A, Teufel P, Weise E. Serovars of Listeria monocytogenes and Listeria innocua in food. Acta Microbiol Hung. 1989;36:249–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun A N, Camilli A, Portnoy D A. Isolation of Listeria monocytogenes small-plaque mutants defective for intracellular growth and cell-to-cell spread. Infect Immun. 1990;58:3770–3778. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.11.3770-3778.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tabouret M, de Rycke J, Audurier A, Poutrel B. Pathogenicity of Listeria monocytogenes isolates in immunocompromised mice in relation to listeriolysin production. J Med Microbiol. 1991;34:13–18. doi: 10.1099/00222615-34-1-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wong H C, Chao W L, Lee S J. Incidence and characterisation of Listeria monocytogenes in foods available in Taiwan. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:3101–3104. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.10.3101-3104.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]