Abstract

Colistin is a last-line antibiotic against Gram-negative pathogens. However, the emergence of colistin resistance has substantially reduced the clinical effectiveness of colistin. In this study, synergy between colistin and capric acid was examined against twenty-one Gram-negative bacterial isolates (four colistin-susceptible and seventeen colistin-resistant). Checkerboard assays showed a synergistic effect against all colistin-resistant strains [(FICI, fractional inhibitory concentration index) = 0.02–0.38] and two colistin-susceptible strains. Time–kill assays confirmed the combination was synergistic. We suggest that the combination of colistin and capric acid is a promising therapeutic strategy against Gram-negative colistin-resistant strains.

Keywords: colistin resistance, combination therapy, capric acid, synergy

Global antimicrobial resistance poses a serious threat to human health. Over the last decade, there has been a rapid increase in the number of multidrug-resistant (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) Gram-negative bacteria [1,2]. Of particular concern is the emergence of carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative pathogenic bacteria such as Acinetobacter baumannii, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Klebsiella pneumoniae which represent a special clinical challenge [3,4]. This situation has only been made worse by the slow development of new antibiotics and the rapid spread of drug-resistant genes, which have led to a decline in the number of effective antibiotics available to treat infections caused by MDR bacteria. Thus, the emergence of such pathogens including carbapenemase-producing Enterobacterales has resulted in the reintroduction of colistin as a last-resort antibiotic treatment [5]. Colistin, a polymyxin antibiotic discovered in the 1950s, is a cationic polypeptide antibiotic produced by Bacillus polymyxa which acts as a bactericidal agent by targeting the polyanionic lipid A of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria [6]. However, widespread use of this agent has given rise to a remarkable increase in colistin-resistant strains [7]. Polymyxin resistance was previously thought to be due solely to mutations in chromosomal genes which led to the modification of lipid A with phosphoethanolamine (pEtN) and/or 4-amino-4-deoxy-L-arabinose (L-Ara4N), thereby reducing the interaction of lipid A with polymyxins [7]. This paradigm changed when we reported for the first time plasmid-mediated colistin resistance via the mcr-1 gene in an isolate from China [8]. Subsequently, more than 60 countries and regions have demonstrated the presence of mcr-1-harboring strains [9], with other mcr family genes (mcr-2 to mcr-10) having since been reported worldwide [10]. The mcr genes encode a pEtN transferase that modifies lipid A with pEtN residues [10]. These reports have led to global concern regarding the efficacy of colistin, raising an urgent need for the identification of new antimicrobial compounds to address these challenges.

Synergy with colistin has been investigated for a variety of traditional antimicrobial agents including rifampicin, rifabutin, carbapenems, clarithromycin, novobiocin, macrolides, minocycline, tigecycline, and glycopeptides [11]. MacNair, C. R et al., demonstrated that when used in combination with colistin, the best synergistic killing activity was achieved with rifampicin, novobiocin, rifabutin, minocycline, and clarithromycin [11]. Synergy with polymyxins has also been shown with several FDA-approved non-antibiotic drugs, representing another promising alternative treatment pathway that is currently underexplored [12,13,14]. Of these, particularly noteworthy are recent studies that have described synergy against a variety of MDR Gram-negative bacteria with colistin in combination with the signal peptidase inhibitor MD3, the antiretroviral HIV drugs zidovudine and azidothymidine, as well as curcumin, netropsin, and auranofin [15,16,17,18]. For example, Martinez-Guitian et al., confirmed that not only did the combination of MD3 and colistin increase the susceptibility of colistin-susceptible clinical isolates of A. baumannii, but that potent synergy with this combination was also observed against colistin-resistant strains with mutations in pmrB and phosphoethanolamine modification of lipid A [15]. Similarly, Feng et al., reported potent synergy when colistin was combined with auranofin against problematic colistin-resistant Gram-negative bacteria both in vitro (K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii, E. coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa) and in vivo (K. pneumoniae, A. baumannii) [18]. Altogether, these results suggest that the use of colistin in combination with such compounds has the potential to enhance bacterial killing of MDR pathogens and prolong the utility of this increasingly important last-line antibiotic. Accordingly, the aim of this study was to find an agent with potential synergistic activity with colistin and assess the in vitro activity of the combination against colistin-susceptible and -resistant Gram-negative bacterial isolates.

We initially screened over 200 compounds for antimicrobial activity against a colistin-resistant E. coli strain, with capric acid identified as a candidate compound. Capric acid is a saturated free fatty acid (FFA) with 10 carbon atoms in the carbon chain and a carboxyl group (–COOH) at one end and a methyl group (–CH3) at the other [19]. FFAs are found in marine organisms and plants and have been reported to show antimicrobial activity by targeting the cell membrane and causing damage to cellular energy production and enzyme activity [20,21]. Although capric acid has been shown to have killing activity against the Gram-positive organism Cutibacterium acnes [22] and the fungus Candida albicans cells [23], activity against Gram-negative organisms has not been investigated. We examined the synergistic potential of capric acid in combination with colistin in vitro against 21 Gram-negative bacterial isolates.

Four colistin-susceptible and seventeen colistin-resistant strains were tested (Table 1), comprising K. pneumoniae (n = 7), E. coli (n = 7), Salmonella (n = 5), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n = 2). Of the colistin-resistant strains, twelve carried the mcr-1 gene, three the mcr-8 gene, while two harbored mutations in chromosomal genes associated with colistin-resistance. The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of colistin and capric acid determined for all strains using broth dilution as per the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (M07-A11) are shown in Table 1. The colistin MICs of the colistin-resistant strains were ≥4 mg/L, while the colistin MICs of susceptible strains ranged from 0.5 to 1 mg/L. The MICs of capric acid were all ≥3200 mg/L, suggesting capric acid had no antimicrobial activity against the tested strains when used as monotherapy.

Table 1.

FICI and MIC (mg/L) values for the strains tested in this study.

| Strain | Origin | PCR for mcr-1 a | MIC (mg/L) | FICI b | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single Drug | Combination | ||||||

| Colistin | Capric Acid | Colistin | Capric Acid | ||||

| K. pneumoniae P11 | Human | - | 1 | >3200 | 0.13 | 400 | 0.26 |

| K. pneumoniae P11+ pHNSHP45 | Transformant | + | 8 | >3200 | 0.5 | 200 | 0.13 |

| K. pneumoniae 117 | Pig | + | 16 | >3200 | 2 | 400 | 0.26 |

| K. pneumoniae 281 | Pig | + | 16 | >3200 | 1 | 200 | 0.13 |

| K. pneumoniae SDQ8C53R c | Chicken | - | >512 | 3200 | 1 | 50 | 0.02 |

| K. pneumoniae HNJ9C285 c | Chicken | - | >512 | 3200 | 4 | 200 | 0.07 |

| K. pneumoniae HNJ9C245 c | Chicken | - | >512 | 3200 | 2 | 100 | 0.04 |

| E. coli C600 | - | - | 0.5 | >3200 | 0.125 | 200 | 0.26 |

| E. coli C600 + pHNSHP45 | Transformant | + | 8 | >3200 | 0.5 | 200 | 0.13 |

| E. coli 2D-8 d | Pig | - | 8 | >3200 | 0.5 | 200 | 0.13 |

| E. coli SHP7 | Pig | + | 8 | >3200 | 2 | 200 | 0.31 |

| E. coli SHP8 | Pig | + | 8 | >3200 | 1 | 200 | 0.19 |

| E. coli SHP50 | Pig | + | 8 | >3200 | 0.5 | 200 | 0.13 |

| E. coli GDF36 | Fish | + | 8 | 3200 | 1 | 800 | 0.38 |

| Salmonella SA316 | Pig | + | 8 | >3200 | 1 | 400 | 0.26 |

| Salmonella SH271 | Pig | + | 4 | 3200 | 1 | 50 | 0.27 |

| Salmonella SH138 | Pig | + | 8 | >3200 | 1 | 400 | 0.26 |

| Salmonella SH47 | Pig | - | 1 | >3200 | 0.25 | 800 | 0.51 |

| Salmonella SH17 | Pig | + | 4 | 3200 | 1 | 50 | 0.27 |

| P. aeruginosa 10104 | CVCC f | - | 1 | >3200 | 1 | >3200 | 2.00 |

| P. aeruginosa 10104 (R) e | Induced | - | 8 | >3200 | 1 | 400 | 0.26 |

a + and - indicate positive and negative for mcr-1. b FICI—Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index. c K. pneumoniae strains harboring colistin resistance gene mcr-8. d E. coli 2D-8 harbors mutations in phoP (Y114I), phoQ (E232D), and pmrA (L3S). e P. aeruginosa 10104 (R) harbors mutations in phoQ (K151R), parS (T222R), colR (L1M), and cprR (T171P). f CVCC—China Veterinary Culture Collection Center.

Synergy between colistin and capric acid was then evaluated by checkerboard assay in a 96-well microtiter plate as previously described [24]. In brief, serial 2-fold dilutions of colistin and capric acid were undertaken with the final concentrations ranging from 0.06 to 32 mg/L for colistin and from 25 to 3200 mg/L for capric acid. Each test organism was added to a density of 5 × 106 CFU/mL, with the final volume in each well being 200 μL. The 96-well plate was then incubated at 37 °C for 18 h. The fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI) for the interaction of the combination was calculated as follows: FICI = FIC of drug A + FIC of drug B = [(MIC of drug A in combination/MIC of drug A alone) + (MIC of drug B in combination/MIC of drug B alone)]. The FICI was interpreted as follows: FICI ≤ 0.5, synergy; FICI > 0.5–4, indifference; FICI > 4, antagonism. The antibacterial activity of colistin increased when used in combination with capric acid, with synergy observed against 19 of the 21 strains, including against all four bacterial species examined (FICI values ranged from 0.02 to 0.38; Table 1). Importantly, the combination of colistin and capric acid was synergistic against all colistin-resistant strains. The only two strains for which synergy was not observed were Salmonella SH47 (FICI, 0.51) and P. aeruginosa 10104 (FICI, 2) (Table 1).

To further examine the potential for synergy with capric acid combined with an antibiotic, we repeated the checkerboard study above using two E. coli isolates (2D-8 and SHP50) and ciprofloxacin, cefotaxime, neomycin, tetracycline, and ampicillin. As shown in Table 2, synergy between capric acid and other antimicrobials was not observed (FICI range, 1–2).

Table 2.

MIC (mg/L) values of capric acid and various antibiotics and FICI values of capric acid when combined with each antibiotic against two colistin-resistant E. coli strains.

| Strain | Antibiotic | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colistin | Ciprofloxacin | Cefotaxime | Neomycin | Tetracycline | Ampicillin | ||

| E. coli 2D-8 | MIC a | 8 | 0.5 | 0.06 | 256 | 32 | 128 |

| FICI b | 0.13 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| E. coli SHP50 | MIC a | 8 | 32 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 128 | 8 |

| FICI b | 0.19 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

a MIC of the single drug. b FICI—Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index.

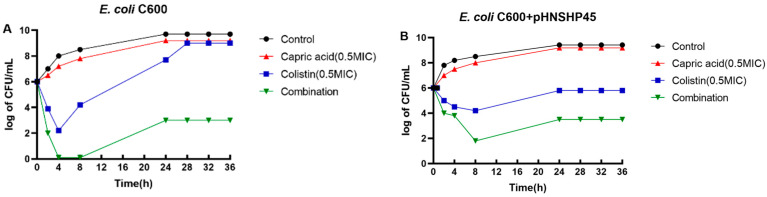

Based on the checkerboard study results, the potential for enhanced bacterial killing with the combination of colistin (0.5× MIC) and capric acid (800 mg/L) was examined using time-kill studies against a colistin-susceptible reference strain (E. coil C600) and mcr-1-positive colistin-resistant strain (E. coli C600 + pHNSHP45) according to a previously reported method [25]. The starting inoculum was ~106 CFU/mL and experiments were conducted for 36 h. Antibiotic-free Mueller-Hinton broth served as the control. Synergy was considered to be a ≥2-log10 reduction in CFU/mL with the combination when compared to the most active monotherapy at the specified time [26]. Bacterial cultures (5 mL) were incubated with shaking (180 rpm) at 37 °C and samples (5 mL) collected at 0, 2, 4, 8, 24, 28, 32 and 36 h for viable counting. The results of time–kill studies are shown in Figure 1. For both strains, no bacterial killing was observed with capric acid monotherapy and growth mirrored that of the growth control. For the colistin-susceptible reference strain (E. coli C600), initial bacterial killing of ~4 log10 CFU/mL with colistin monotherapy at 4 h was followed by rapid regrowth that had returned to control values by 28 h (Figure 1A). Amplification of colistin-resistant subpopulations in heteroresistant isolates, namely susceptible isolates based upon their MICs but which contain resistant subpopulations, is known to contribute to regrowth following polymyxin monotherapy [27]. However, synergy was observed with combination therapy from 4 h onwards such that no viable bacteria were observed across 4–8 h, with subsequent regrowth remaining at ~5 log10 CFU/mL below that of the control and monotherapies. Synergistic killing was also observed from 8 h onwards with the mcr-1-positive colistin-resistant strain (E. coli C600 + pHNSHP45), although the enhancement of bacterial killing with the combination was less than that observed with E. coli C600 (Figure 1B). Altogether, the time-kill experiments showed good bactericidal activity (≥3 log10 CFU/mL) and synergy with combination therapy against both strains (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Time-kill study performed with E. coli C600 (A) and E. coli C600 + pHNSHP45 (B) with colistin monotherapy (0.5× MIC), capric acid monotherapy (800 mg/L), and their combination (equivalent concentrations).

Resistance genes are often associated with various mobile genetic structures, facilitating their dissemination among different Enterobacterales species. The plasmid-mediated transmission of the colistin resistance gene mcr-1 has raised serious concerns for the efficacy of colistin, pointing to the urgent need for new agents to effectively treat clinical infections caused by colistin-resistant isolates [8]. Here, we demonstrated synergistic bacterial killing with the combination of colistin and capric acid against a variety of mcr-1-positive Gram-negative bacterial strains (Table 1 and Figure 1). While the specific mechanism(s) for the observed synergy with this combination is not yet known, one possible explanation is that capric acid disturbs the stability and activity of the bacterial membrane, enabling more colistin to target lipid A. Like other FFAs, capric acid can cross the cell membrane and disrupt the electron transport chain, resulting in a reduction of ATP production [19]. It has previously been shown that capric acid has anti-adhesion activity and inhibits the adhesion of C. albicans cells to abiotic surfaces [23]. A recent study by Jakub et al., showed that capric acid combined with either fluconazole or amphotericin B achieved synergistic killing of C. albicans by causing the MDR transporter Cdr1p to relocalize from the plasma membrane to the interior of the cell, leading to reduced efflux activity of Cdr1p [28]. These findings raise the possibility that capric acid may have an impact on the function/integrity of bacterial membranes, thereby enabling more colistin to bind lipid A and thus increasing bacterial susceptibility to colistin.

Another possible mechanism for the synergy between colistin and capric acid involves the prevention of lipid A modifications by capric acid. The bactericidal activity of colistin begins when it binds to the lipid A component of LPS. The LPS structure can be altered via two-component regulatory systems (TCSs, e.g., PmrAB, ParRS, CprRS, PhoPQ and CrrAB) [7]. The TCSs are sensitive to environmental stimuli including exposure to exogenous compounds or metal ions such as Mg2+ and Fe2+, which usually results in the modification of the lipid A phosphate groups via the addition of cationic L-Ara4N and/or pEtN moieties [7]. MCR-1 is phosphoethanolamine (pEtN) transferase that leads to the addition of pEtN to lipid A. It is possible that exogenous capric acid prevents such modifications of lipid A, thereby retaining sensitivity to colistin. However, further studies specifically examining the mechanism(s) of synergy are required.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that capric acid can enhance bacterial killing of colistin-resistant Gram-negative bacteria when combined with colistin. Although the underlying mechanism(s) of synergy with this combination remains to be elucidated, our results suggest that further exploration of this combination against MDR pathogens is warranted.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.-Y.L. and X.-F.P.; methodology, Y.-Y.L., H.-Y.Y. and L.-M.D.; software, H.-Y.Y. and Z.-L.Z.; validation, H.-Y.Y. and W.-Y.H.; formal analysis, Y.-Y.L.; investigation, Y.-Y.L.; resources, Z.-L.Z., Z.-H.Q. and X.-F.P.; data curation, Y.-Y.L. and P.J.B.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.-Y.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.-Y.L., P.J.B. and J.-H.L.; visualization, Y.-Y.L. and H.-Y.Y.; supervision, X.-F.P. and J.-H.L.; project administration, X.-F.P. and J.-H.L.; funding acquisition, J.-H.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31830099), Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou (No. 202201010300), Project of Educational Commission of Guangdong Province of China (2021KQNCX006), Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou, China (202201010300), the Innovation Team Project of Guangdong University (No. 2019KCXTD001), and the 111 Project (No. D20008). The APC was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31830099).

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.De Oliveira D., Forde B.M., Kidd T.J., Harris P., Schembri M.A., Beatson S.A., Paterson D.L., Walker M.J. Antimicrobial Resistance in ESKAPE Pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2020;33:e00181-19. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00181-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Du H., Chen L., Tang Y.W., Kreiswirth B.N. Emergence of the mcr-1 colistin resistance gene in carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016;16:287–288. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dortet L., Cuzon G., Ponties V., Nordmann P. Trends in carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae, France, 2012 to 2014. Eurosurveillance. 2017;22:30461. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2017.22.6.30461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schuelter-Trevisol F., Schmitt G.J., Araujo J.M., Souza L.B., Nazario J.G., Januario R.L., Mello R.S., Trevisol D.J. New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase-1-producing Acinetobacter spp. infection: Report of a survivor. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2016;49:130–134. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0150-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Livermore D.M., Warner M., Mushtaq S., Doumith M., Zhang J., Woodford N. What remains against carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae? Evaluation of chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, colistin, fosfomycin, minocycline, nitrofurantoin, temocillin and tigecycline. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2011;37:415–419. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdul R.N., Cheah S.E., Johnson M.D., Yu H., Sidjabat H.E., Boyce J., Butler M.S., Cooper M.A., Fu J., Paterson D.L., et al. Synergistic killing of NDM-producing MDR Klebsiella pneumoniae by two ‘old’ antibiotics-polymyxin B and chloramphenicol. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015;70:2589–2597. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poirel L., Jayol A., Nordmann P. Polymyxins: Antibacterial Activity, Susceptibility Testing, and Resistance Mechanisms Encoded by Plasmids or Chromosomes. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2017;30:557–596. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00064-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Y.Y., Wang Y., Walsh T.R., Yi L.X., Zhang R., Spencer J., Doi Y., Tian G., Dong B., Huang X., et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: A microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2016;16:161–168. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nang S.C., Li J., Velkov T. The rise and spread of mcr plasmid-mediated polymyxin resistance. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2019;45:131–161. doi: 10.1080/1040841X.2018.1492902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hussein N.H., Al-Kadmy I., Taha B.M., Hussein J.D. Mobilized colistin resistance (mcr) genes from 1 to 10: A comprehensive review. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021;48:2897–2907. doi: 10.1007/s11033-021-06307-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macnair C.R., Stokes J.M., Carfrae L.A., Fiebig-Comyn A.A., Coombes B.K., Mulvey M.R., Brown E.D. Overcoming mcr-1 mediated colistin resistance with colistin in combination with other antibiotics. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:458. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-02875-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hussein M., Schneider-Futschik E.K., Paulin O., Allobawi R., Crawford S., Zhou Q.T., Hanif A., Baker M., Zhu Y., Li J., et al. Effective Strategy Targeting Polymyxin-Resistant Gram-Negative Pathogens: Polymyxin B in Combination with the Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Sertraline. ACS Infect. Dis. 2020;6:1436–1450. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.0c00108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Falagas M.E., Voulgaris G.L., Tryfinopoulou K., Giakkoupi P., Kyriakidou M., Vatopoulos A., Coates A., Hu Y. Synergistic activity of colistin with azidothymidine against colistin-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae clinical isolates collected from inpatients in Greek hospitals. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2019;53:855–858. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2019.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou Y.F., Liu P., Dai S.H., Sun J., Liu Y.H., Liao X.P. Activity of Tigecycline or Colistin in Combination with Zidovudine against Escherichia coli Harboring tet(X) and mcr-1. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020;65:e01172-20. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01172-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinez-Guitian M., Vazquez-Ucha J.C., Odingo J., Parish T., Poza M., Waite R.D., Bou G., Wareham D.W., Beceiro A. Synergy between Colistin and the Signal Peptidase Inhibitor MD3 Is Dependent on the Mechanism of Colistin Resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016;60:4375–4379. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00510-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung J.H., Bhat A., Kim C.J., Yong D., Ryu C.M. Combination therapy with polymyxin B and netropsin against clinical isolates of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:28168. doi: 10.1038/srep28168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dai C., Wang Y., Sharma G., Shen J., Velkov T., Xiao X. Polymyxins-Curcumin Combination Antimicrobial Therapy: Safety Implications and Efficacy for Infection Treatment. Antioxidants. 2020;9:506. doi: 10.3390/antiox9060506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feng X., Liu S., Wang Y., Zhang Y., Sun L., Li H., Wang C., Liu Y., Cao B. Synergistic Activity of Colistin Combined With Auranofin Against Colistin-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2021;12:676414. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.676414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Desbois A.P., Smith V.J. Antibacterial free fatty acids: Activities, mechanisms of action and biotechnological potential. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010;85:1629–1642. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2355-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McGaw L.J., Jäger A.K., Van Staden J., Houghton P.J. Antibacterial effects of fatty acids and related compounds from plants. South Afr. J. Bot. 2002;68:417–423. doi: 10.1016/S0254-6299(15)30367-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li L., Chen H., Liu Y., Xu S., Wu M., Liu Z., Qi C., Zhang G., Li J., Huang X. Synergistic effect of linezolid with fosfomycin against Staphylococcus aureus in vitro and in an experimental Galleria mellonella model. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2020;53:731–738. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2018.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang W.C., Tsai T.H., Chuang L.T., Li Y.Y., Zouboulis C.C., Tsai P.J. Anti-bacterial and anti-inflammatory properties of capric acid against Propionibacterium acnes: A comparative study with lauric acid. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2014;73:232–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2013.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Murzyn A., Krasowska A., Stefanowicz P., Dziadkowiec D., Bukaszewicz M. Capric acid secreted by S. boulardii inhibits C. albicans filamentous growth, adhesion and biofilm formation. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e12050. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vidaillac C., Benichou L., Duval R.E. In vitro synergy of colistin combinations against colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012;56:4856–4861. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05996-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Betts J.W., Sharili A.S., La Ragione R.M., Wareham D.W. In Vitro Antibacterial Activity of Curcumin-Polymyxin B Combinations against Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria Associated with Traumatic Wound Infections. J. Nat. Prod. 2016;79:1702–1706. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.6b00286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pillai S.K., Moellering R.C., Eliopoulos G.M. Antimicrobial combinations. In: Lorian V., editor. Antibiotics in Laboratory Medicine. 5th ed. The Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Co.; Philadelphia, PA, USA: 2005. pp. 365–440. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bergen P.J., Smith N.M., Bedard T.B., Bulman Z.P., Cha R., Tsuji B.T. Rational Combinations of Polymyxins with Other Antibiotics. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019;1145:251–288. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-16373-0_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suchodolski J., Derkacz D., Bernat P., Krasowska A. Capric acid secreted by Saccharomyces boulardii influences the susceptibility of Candida albicans to fluconazole and amphotericin B. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:6519. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-86012-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.