Abstract

Bacteroides forsythus is a gram-negative anaerobic bacterium associated with periodontitis. The bspA gene encoding a cell surface associated leucine-rich repeat protein (BspA) involved in adhesion to fibronectin and fibrinogen was recently cloned from this bacterium in our laboratory. We now describe the construction of a BspA-defective mutant of B. forsythus. This is the first report describing the generation of a specific gene knockout mutant of B. forsythus, and this procedure should be useful in establishing the identity of virulence-associated factors in these organisms.

Bacteroides forsythus, a gram-negative fusiform anaerobe first described by Tanner et al. (19), has recently been recognized as one of the periodontal pathogens associated with periodontal disease. The clinical studies of Grossi et al. (6, 7) and Ximenez-Fyvie et al. (20) have shown a strong association of B. forsythus with the severity of periodontitis in adult patients. Due to the fastidious nature for growth of this bacterium and the difficulties in cultivating it from the human oral cavity, its role in the progression of periodontal disease has been difficult to determine. To date, only a few putative virulence factors have been identified in this organism based on their in vitro properties. These include, a trypsin-like protease (19), a sialidase (9), N-benzoyl-Val-Gly-Arg-p-nitroanilide-specific protease encoded by the prtH gene (15), and a cell surface-associated BspA protein (16). Recent studies have also shown B. forsythus to possess cell surface-associated apoptosis-inducing activity in host cells (1). The bspA gene encoding the BspA protein was cloned and expressed in our laboratory (16), and the deduced amino acid sequence of the BspA protein showed 14 tandem repeats of a 23-amino-acid leucine-rich (LRR) motif. The LRR motifs are present in a number of other proteins with diverse functions and cellular locations in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes (11). Our in vitro studies showed that the BspA protein bound to extracellular matrix components (fibronectin and fibrinogen) and therefore could be an important virulence factor involved in B. forsythus colonization of the oral cavity.

There is little known concerning how the putative B. forsythus virulence factors may contribute to its pathogenesis in vivo. This is partly due to the lack of genetic systems for obtaining specific gene “knockout” mutants of B. forsythus. Although transposon-based random mutagenesis has been described for Bacteroides sp. (18), the extent to which these genetic systems can be applied to B. forsythus is unknown. The present study was undertaken to develop a specific gene knockout system for use in B. forsythus. We utilized the targeted insertional mutagenesis strategy based on use of a suicide plasmid system to inactivate the B. forsythus bspA gene.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and culture conditions.

B. forsythus ATCC 43037 was grown in BF broth composed of brain heart infusion broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) containing 0.5% yeast extract, 5 μg of hemin per ml, 0.5 μg of vitamin K per ml, 0.001% N-acetylmuramic acid (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.), 0.1% l-cysteine (Sigma), and 5% fetal bovine serum (Gibco-BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.) or on BF agar plates (1.5% Difco agar in BF broth). B. forsythus cell were grown in BF broth or on BF agar under anaerobic conditions (85% N2, 10% H2, 5% CO2) at 37°C. Since B. forsythus 43037 is inherently resistant to gentamicin, 200 μg of gentamicin per ml was added in BF broth and BF agar plates in mating experiments for selection. Escherichia coli DH5α, used as a host for plasmid maintenance was grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (Gibco-BRL) or on LB agar plates. pMJF-3 (4) is a Bacteroides sp.-E. coli shuttle plasmid containing a pUC19 replicon (ori) for replication in E. coli, a replicon (repA) for replication in Bacteroides sp., and a mobilization region (mobA), which allows it to be mobilized from E. coli to Bacteroides sp. by broad-host-range IncP plasmids. RK231 (16), a broad-host-range mobilizing IncP plasmid was obtained from M. Malamy (Tufts University, Boston, Mass.). The antibiotics added for plasmid selection were ampicillin (100 μg/ml) for pMJF-3 and pMJF-R11 and kanamycin (50 μg/ml) for RK231.

Construction of a bspA mutant of B. forsythus.

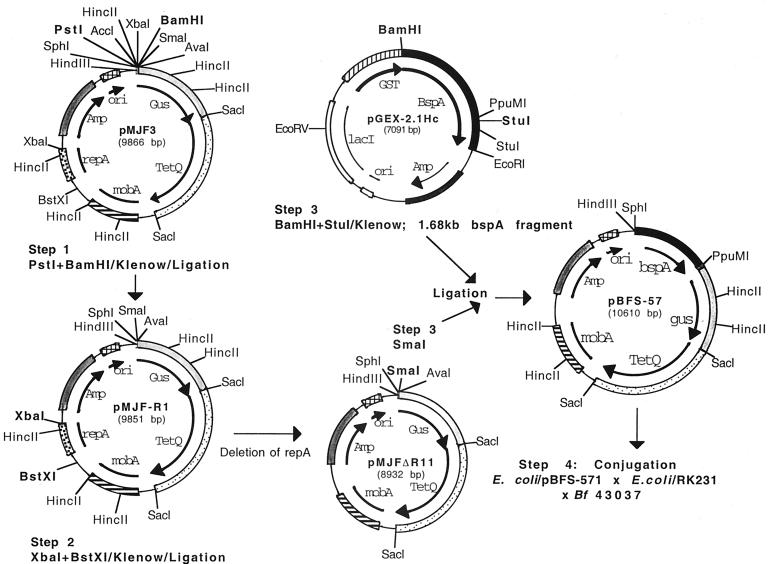

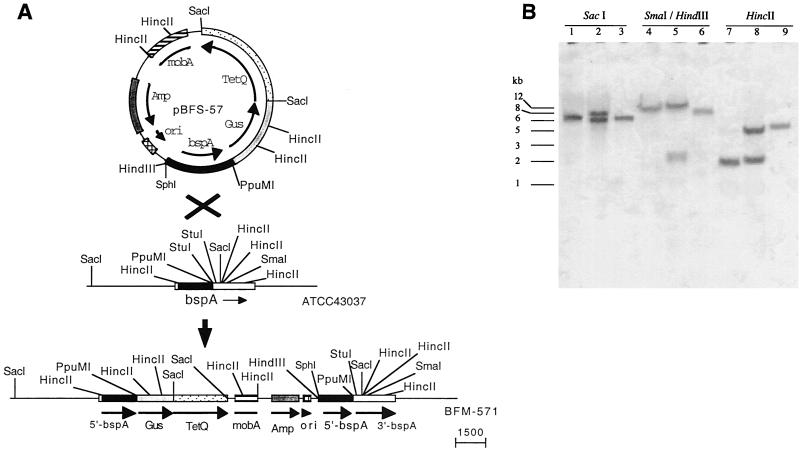

The strategy for B. forsythus BspA mutant construction is depicted in Fig. 1. All recombinant DNA manipulations were carried out according to standard molecular biology protocols (2). Plasmid pMJF-3, a shuttle vector for Bacteroides sp. and E. coli was digested with PstI and BamHI to remove intervening AccI and XbaI sites, followed by treatment with Klenow enzyme to make blunt-ended DNA. The linearized blunt-ended plasmid was circularized by ligation reaction with DNA ligase to result in plasmid pMJF-R1. Plasmid pMJF-R1 was then digested with XbaI and BstXI to delete repA; this was followed by Klenow treatment and ligation. The resulting plasmid (pMJF-ΔRII) was thus devoid of the functional repA gene required for replication in Bacteroides. The bspA gene fragment for cloning into pMJF-ΔRII plasmid was obtained from a previously constructed expression vector (18; labeled pGEX-2.1Hc in the present study). pGEX-2.1Hc contains 2.1-kb HincII fragment of the bspA gene in frame with the glutathione S-transferase gene for the expression of BspA (amino acid residues 17 to 724 of the BspA)–glutathione S-transferase fusion protein. The 1.68-kb bspA fragment was excised from pGEX-2.1Hc by digestion with BamHI (located outside of bspA) and StuI (located within the bspA fragment), followed by Klenow treatment to make blunt-ended DNA. The blunt-ended fragment was ligated into the SmaI site of pMJF-ΔRII, resulting in pBFS-57. pBFS-57 was then utilized for targeted insertional inactivation of the bspA locus in the B. forsythus genome by homologous recombination. This was carried out by triparental conjugation between E. coli harboring pBFS-57, E. coli RK231 to supply conjugal transfer function, and B. forsythus ATCC 43037. A triparental mating procedure described previously for Bacteroides sp. was adapted (18). Briefly, E. coli/pBFS-57 and E. coli/RK231 were aerobically grown to a density of 2 × 108 cells/ml at 37°C in LB broth containing ampicillin and kanamycin, respectively. B. forsythus ATCC 43037 was grown anaerobically to 5 × 105 cells/ml at 37°C in BF broth containing gentamicin at 200 μg/ml (B. forsythus 43037 is inherently resistant to gentamicin at the concentrations used). Then, 1 ml cultures of E. coli/pBF-57 and E. coli/RK 231 were mixed with a 30-ml culture of B. forsythus, and the cells were pelleted by centrifugation (2,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C). The bacterial mixture was then resuspended in 200 μl of LB broth and spotted onto BF blood agar plates. The plates were incubated at 37°C for 18 h under aerobic conditions, and the cells were recovered from the plates. The cells were then resuspended in 200 μl of LB broth and plated onto BF blood agar plates containing gentamicin (200 μg/ml) and tetracycline (1 μg/ml), and the plates were incubated anaerobically at 37°C for 10 to 15 days. Tetracycline-resistant B. forsythus transformants were obtained at a frequency of approximately 8 × 10−5 per recipient. The transconjugates were analyzed by Southern blot analysis for confirmation of plasmid integration into the bspA locus due to single crossover recombination. Briefly, the chromosomal DNA isolated from wild type strain ATCC 43037 and the transconjugate were digested with restriction enzymes prior to Southern blotting and probe hybridization (17). A digoxigenin-labeled fragment of the bspA gene (1.68-kb BamHI-StuI fragment) was used as a probe. Probe labeling, hybridization, and detection were carried out with the DIG DNA Labeling and Detection Kit (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The results of Southern blot analysis of one of the representative transconjugates (labeled BFM-571) is shown in Fig. 2B. As expected from the predicted chromosomal structure of the mutant depicted in Fig. 2A, the bspA probe hybridized to 6.5-and 7.5-kb SacI fragments, 2.5- and ∼12-kb SmaI-HindIII fragments, and 2.3- and 5.1-kb HincII fragments from mutant BFM-571 strain (Fig 2B, lanes 2, 5, and 8). In contrast, the bspA probe hybridized to 6.5-kb SacI, 8-kb SmaI-HindIII, and 2.1-kb HincII fragments from the wild-type ATCC 43037 strain (Fig 2B, lanes 1, 4, and 7). pBFS-57 plasmid DNA digested with corresponding enzymes was used as a positive control (Fig 2B, lanes 3, 6, and 9). In addition, a 2.5-kb SacI fragment of the tetracycline resistance gene (tetQ) used as a probe hybridized only to chromosomal DNA from the mutant (BFM-571) and did not hybridize to chromosomal DNA from the wild-type strain (data not shown). Taken together, these results confirmed that the suicide vector disrupted the bspA gene of B. forsythus via integration into the bspA locus.

FIG. 1.

Schematics of B. forsythus suicide vector construction.

FIG. 2.

(A) Schematics of the integration of suicide plasmid pBFS-57 into the bspA locus of the B. forsythus genome. (B) Southern hybridization. Genomic DNA isolated from B. forsythus wild-type (ATCC 43037, lanes 1, 4, and 7), mutant (BFM-571, lanes 2, 5, and 8), and suicide plasmid DNA (pBFS-57, lanes 3, 6, and 9) digested with restriction enzymes shown on top were hybridized with the bspA probe. Numbers on the left indicate sizes in kilobases.

Expression of the BspA protein.

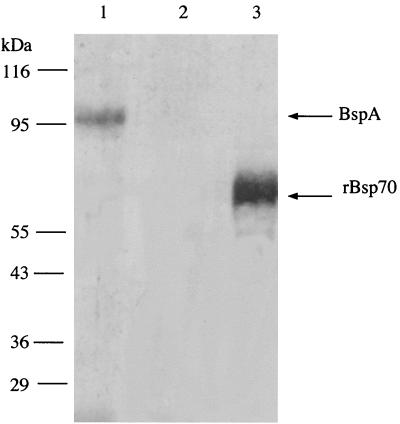

To confirm that the mutant BFM-571 was defective in the expression of the BspA protein, whole-cell lysates were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western immunoblot analysis using a polyclonal anti-BspA rabbit antibody as a probe. This antibody was raised against the recombinant 70-kDa BspA polypeptide (rBsp70, amino acid residues 17 to 724 of BspA) (16). The results showed that the ∼95-kDa BspA protein present in the wild-type cells (reacting positively, Fig. 3, lane 1) was missing from the cell lysates of mutant strain BFM-571 (Fig. 3, lane 2). The rBsp70 was used as a positive control (Fig. 3, lane 3). Based on the fragment length of the bspA utilized for single-crossover recombination, expression of a truncated form of the BspA protein was expected. However, we did not detect any truncated BspA protein in the mutant cell extracts. A possible explanation for this observation could be that the truncated BspA protein formed in the mutant cell was unstable and quickly degraded after synthesis. Additionally, it is possible that the bspA transcript formed from the truncated gene was unstable. The lack of detection of truncated forms of proteins in mutants constructed by homologous recombination via a single-crossover event has been reported in Porphyromonas gingivalis. For instance, the FimA-defective mutants of P. gingivalis (8, 13) do not show any truncated FimA proteins.

FIG. 3.

Western immunoblot analysis of wild-type and mutant B. forsythus. Proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes after separation on an SDS–10% PAGE gel. Membranes were probed with anti-rBspA antibody (16). Lanes: 1, total cell lysate of wild-type B. forsythus ATCC 43037; 2, total cell lysate of mutant BFM-571; 3, recombinant BspA protein (70-kDa rBsp70). The positions of molecular mass standards (in kilodaltons) are shown on the left.

Functional properties of the BspA mutant.

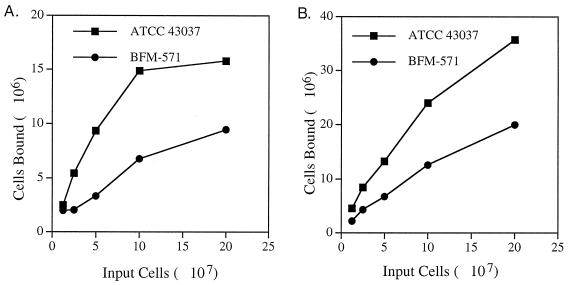

We have shown previously that the BspA protein binds to extracellular matrix components (fibronectin and fibrinogen) via protein-protein interactions (16). The ability of the B. forsythus bspA mutant to adhere to fibronectin and fibrinogen was compared to wild-type strain by use of a modified in vitro adherence assay (3). Briefly, 48-well microtiter plates (Costar, Cambridge, Mass.) were coated with 200 μl of a fibronectin (Sigma) or fibrinogen (Sigma) solution (5 μg/well in 0.05 M sodium bicarbonate buffer at pH 9.6) and incubated for 16 h at 4°C. The plates were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Sigma) containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBST) and were blocked with 2% bovine serum albumin in PBS (250 μl per well for 1 h at room temperature). Cells were labeled by inoculating a late-log-phase culture (1:100) into 5 ml of BF broth containing 25 μCi of [3H]adenosine (NEN Research). After growth at 37°C under anaerobic conditions for 3 days, cells were harvested and adjusted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 1.0. Both the wild-type and mutant strains showed similar growth rates (data not shown) and showed similar specific activities (9,200 ± 900 cpm/108 cells). For the binding assay, 1.25 × 107 to 2 × 108 cells of 3H-labeled wild-type B. forsythus ATCC 43037 and BFM-571 mutant cells resuspended in 200 μl of PBS were applied to fibronectin- or fibrinogen-coated microtiter wells in duplicates and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. After incubation, the plates were washed three times with PBST to remove nonadherent bacteria, and the bound bacteria were then dissociated by the addition of 100 μl of 1% SDS–0.5 N NaOH solution per well. After a 20-min incubation at room temperature, 100 μl of 0.5 N HCl was added to each well, and the contents from each well were subjected to liquid scintillation counting to determine the bound radioactivity. Binding curves for fibronectin or fibrinogen were plotted as the number of bacteria bound (calculated from bound counts per minute) at each of the input cell concentration. The results (Fig. 4) showed reduced ability of BspA mutant (BFM-571) to bind to fibronectin and fibrinogen compared to the wild-type strain (ATCC 43037). These results thus confirmed BspA's role binding to extracellular matrix (ECM) components and further lend support to the hypothesis that BspA may be an important factor for bacterial colonization.

FIG. 4.

Binding curves of wild-type B. forsythus ATCC 43037 and BFM-571 mutant to immobilized fibronectin (A) and fibrinogen (B). Fibonectin- or fibrinogen-coated microtiter wells were incubated for 1 h with different numbers of 3H-labeled wild-type and mutant bacteria (1.25 × 107 to 2 × 108 cells of each). Both strains showed similar specific activities (9,200 ± 900 cpm/108 cells). After the nonadherent cells were washed, the numbers of cells bound per well were calculated from the bound radioactivity. The results presented are the mean values of duplicate samples representative of two independent experiments.

In addition, we also measured the hydrophobicity of the BspA mutant. The hydrophobicity of bacterial cells has been correlated with colonization potential (14). Evaluation of cell hydrophobicity was carried out as described previously (5, 10). Briefly, B. forsythus ATCC 43037 and mutant (BFM-571) were suspended in 0.15 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.1) containing 0.3 M urea and 6.7 mM MgSO4 (PUM buffer) (9) and adjusted to an OD400 of 0.5. To a 1.2-ml bacterial suspension in a glass tube (10 by 70 mm), 600 μl of n-hexadecane (Sigma) was added. The tubes were vigorously mixed for 60 s by vortexing, followed by incubation for 15 min at room temperature, and the absorbance of the aqueous phase was measured at 400 nm. The percent hydrophobicity was calculated as follows: % hydrophobicity = [(A400 before mixing − A400 after mixing)/A400 before mixing] × 100. Each isolate was assayed six times, and the values obtained were averaged. The results showed a significant reduction (P < 0.01) in the hydrophobicity of mutant BFM-571 (24% ± 4%; mean ± the standard error) compared to the wild-type strain (54% ± 8%; mean ± the standard error).

In summary, we have developed a suicide plasmid based gene deletion system in B. forsythus. The suicide plasmid pMJF-R1 constructed in this study should be useful for generating specific gene knockouts of B. forsythus. Additionally, the chromosomally integrated gus gene, which expresses an active glucoronidase enzyme in Bacteroides sp. (4), could be useful as a reporter enzyme in studies of the regulation of specific gene promoters in B. forsythus.

This is the first report of the construction of a specific gene knockout mutant of B. forsythus and should be useful in establishing the identity of putative virulence-associated factors of B. forsythus in pathogenesis. Due to its ability to bind ECM, BspA may be involved in B. forsythus colonization following tissue destruction induced by P. gingivalis. Tissue destruction would make ECM easily accessible for colonization by B. forsythus. The pathogenic potential of the BspA mutant, BFM-571, defective in the expression of the BspA protein, in animal models should provide insight into the in vivo role of the BspA protein.

Acknowledgments

Plasmid pMJF-3 was kindly provided by N. Hamada (Kanagawa Dental College, Yokosuka, Japan) and E. coli/RK231 was kindly provided by M. M. Malamy (Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, Mass.).

This study was supported by NIDCR grant DE 12320.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arakawa S, Nakajima T, Ihikura H, Ichinose S, Ishikawa I, Tsuchida N. Novel apoptois-inducing activity in Bacteroides forsythus: a comparative study with three serotypes of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Infect Immun. 2000;68:4611–4615. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.8.4611-4615.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ausubel F A, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chia J S, Yeah C Y, Chen J Y. Identification of a fibronectin binding protein from Streptococcus mutans. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1864–1870. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.4.1864-1870.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feldhaus M J, Hwa V, Cheng Q, Salyers A A. Use of an Escherichia coli β-glucuronidase gene as a reporter gene for investigation of Bacteroides promoters. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4540–4543. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.14.4540-4543.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gibbons R J, Etherden I, Skobe S. Association of fimbriae with the hydrophobicity of Streptococcus sanguis FC-1 and adherence to salivary pellicles. Infect Immun. 1983;41:414–417. doi: 10.1128/iai.41.1.414-417.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grossi S G, Zambon J J, Ho A W, Koch G, Dunford R G, Machtei E E, Norderyed O M, Genco R J. Assessment of risk for periodontal disease. I. Risk indicators for alveolar bone loss. J Periodontol. 1994;65:260–267. doi: 10.1902/jop.1994.65.3.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grossi S G, Genco R J, Machtei E E, Ho A W, Koch G, Dunford R G, Zambon J J, Hausmann E. Assessment of risk for periodontal disease II. Risk for indicators for alveolar bone loss. J Periodontol. 1995;66:23–29. doi: 10.1902/jop.1995.66.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamada N, Watanabe K, Sasakawa C, Yoshikawa M, Yoshimura F, Umemoto T. Construction and characterization of a fimA mutant of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1696–1704. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.1696-1704.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holt S C, Barman T E. Factors in virulence expression and their role in periodontal disease pathogens. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1991;2:177–281. doi: 10.1177/10454411910020020301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishihara K, Kuramitsu H K, Miura T, Okuda K. Dentilisin activity affects the organization of the outer sheath of Treponema denticola. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:3837–3844. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.15.3837-3844.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kobe B, Deisenhofer J. The leucine-rich repeat: a versatile binding motif. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19:415–421. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malek R, Fisher J G, Caleca A, Stinson M, van Oss C, Lee J Y, Cho M I, Genco R J, Evans R T, Dyer D W. Inactivation of the Porphyromonas gingivalis fimA gene blocks periodontal damage in gnotobiotic rats. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:1052–1059. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.4.1052-1059.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naito Y, Tohda H, Okuda K, Takazoe I. Adherence and hydrophobicity of invasive and noninvasive strains of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1993;8:195–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1993.tb00559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saito T, Ishihara K, Kato T, Okuda K. Cloning, expression, and Sequencing of a protease gene from Bacteroides forsythus ATCC 43037 in Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4888–4891. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4888-4891.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharma A, Sojar H T, Glurich I, Honma K, Kuramitsu H K, Genco R J. Cloning, expression, and sequencing of a cell surface antigen containing a leucine-rich repeat motif from Bacteroides forsythus ATCC 43037. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5703–5710. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.5703-5710.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Southern E M. Detection of specific sequence among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J Mol Biol. 1975;98:503–517. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang Y P, Malamy M H. Isolation of Bacteroides fragilis mutans with in vivo growth defects by using Tn4400′, a modified Tn4400 transposon system, and a new screening method. Infect Immun. 2000;68:415–419. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.415-419.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanner A C R, Listgarten M A, Ebersole J L, Strzempko M N. Bacteroides forsythus sp. nov., a slow-growing, fusiform Bacteroides sp. from the human oral cavity. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1986;36:213–221. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ximenez-Fyvie L A, Haffajee A D, Socransky S S. Comparison of the microbiota of supra- and subgingival plaque in health and periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27:648–657. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2000.027009648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]