Abstract

Context:

Multiple myeloma and extensive lytic skeletal metastases may appear similar on positron-emission tomography and computed tomography (PET-CT) in the absence of an obvious primary site or occult malignancy. Radiomic analysis extracts a large number of quantitative features from medical images with the potential to uncover disease characteristics below the human visual threshold.

Aim:

This study aimed to evaluate the diagnostic capability of PET and CT radiomic features to differentiate skeletal metastases from multiple myeloma.

Settings and Design:

Forty patients (20 histopathologically proven cases of multiple myeloma and 20 cases of a variety of bone metastases) underwent staging 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET-CT at our institute.

Methodology:

A total of 138 PET and 138 CT radiomic features were extracted by manual semi-automatic segmentation and standardized. The original dataset was subject separately to receiver operating curve analysis and correlation matrix filtering. The former showed 16 CT and 19 PET parameters to be significantly related to the outcome at 5%, whereas the latter resulted in 16 CT and 14 PET features. Feature selection was done with 7 evaluators with stratified 10-fold cross-validation. The selected features of each evaluator were subject to 14 machine-learning algorithms. In view of small sample size, two approaches for model performance were adopted: The first using 10-fold stratified cross-validation and the second using independent random training and test samples (26:14). In both approaches, the highest area under the curve (AUC) values were selected for 5 CT and 5 PET features. These 10 features were combined and the same process was repeated.

Statistical Analysis Used:

The quality of the performance of the models was assessed by MSE, RMSE, kappa statistic, AUC, area under the precision-recall curve, F-measure, and Matthews correlation coefficient.

Results:

In the first approach, the highest AUC = 0.945 was seen with 5 CT parameters. In the second approach, the highest AUC = 0.9538 was seen with 4 CT and one PET parameter. CT neighborhood gray-level different matrix coarseness and CT gray-level run-length matrix LGRE were common parameters in both approaches. Comparison of AUC of the above models showed no significant difference (P = 0.9845). Feature selection by principal components analysis and feature classification by the multilayer perceptron machine-learning model using independent training and test samples yielded the overall highest AUC.

Conclusions:

Machine-learning models using CT parameters were found to differentiate bone metastases from multiple myeloma better than models using PET parameters. Combined models using PET and CECT data showed better overall performance than models using only either PET or CECT data. Machine-learning models using independent training and test sets were performed on par with those using 10-fold stratified cross-validation with the former incorporating slightly more PET features. Certain first- and second-order CT and PET texture features contributed in differentiating these two conditions. Our findings suggested that, in general, metastases were finer in CT and PET texture and myelomas were more compact.

Keywords: Computed tomography, machine learning, positron-emission tomography, radiomics, texture

Introduction

Radiomics is a field of medical study that aims to extract a large number of quantitative features from medical images using data characterization algorithms. It has the potential to uncover disease characteristics that are difficult to identify by human vision alone and uses a process of image processing, segmentation, feature extraction, and model validation.[1]

Multiple myeloma is the most common primary malignant bone neoplasm in adults. It presents most commonly as multiple lytic bone lesions and less commonly as diffuse osteopenia, solitary plasmacytoma, and an Osteo-sclerosing variant (3%).[2] Skeletal metastases account for 70% of all malignant bone tumors and are seen in a vast number of primary cancers although primaries from the lung, breast, kidney, and prostate account for approximately 80% of all skeletal metastases.[3] They can present as lytic, sclerotic, or mixed lesions. Myeloma tends to spare the vertebral pedicles and involve the mandible, whereas metastatic carcinoma does the reverse. Multiple myeloma and extensive lytic skeletal metastases may appear similar on positron-emission tomography and computed tomography (PET-CT) in the absence of an obvious primary site or occult malignancy and in such cases, histopathology remains the gold standard supplemented by biochemical, immunohistochemical, and molecular data. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET is used to detect the distribution (including extraskeletal), activity, complications, and response evaluation of minimal residual disease in line with International Myeloma Working Group guidelines.[4] High FDG uptake in the bone may be considered a positive lesion even in the absence of osteolysis. The differential for both is benign and malignant tumors, infection, trauma, and osteonecrosis.

Methodology

Patients

This retrospective analytical study was conducted in June 2021 in the Department of Radiology and Imaging Sciences in our institute utilizing the database of PET-CT cases from March 2017 to May 2021. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee with a waiver for patient consent.

A total of 40 patients were selected, each of whose PET-CT reports diagnosed a differential of skeletal metastases or multiple myeloma based on multiple focal or diffuse FDG avid lytic bone lesions with or without soft tissue components. All of them underwent histopathological examination. 20 patients were diagnosed with multiple myeloma and the rest with metastases from a variety of malignancies.

Inclusion criteria included patients referred to PET-CT to differentiate multiple myeloma from metastatic lesions and were subsequently biopsied based on the findings.

Exclusion criteria were PET-CT data incompatible with feature extraction software, unavailable histopathology data, and patients whose biopsy depicted benign lesions, infection, or inflammation.

Positron-emission tomography and computed tomography examination

18F-FDG PET-CT was performed on a 16-slice Biograph Horizon clinical PET-CT system with TrueV-4 Ring (Siemens Healthcare Erlangen Germany) and a Siemens (VJ21B) PETsyngo acquisition workplace user interface. All cases were injected with 5–10 mCi (1 mCi/7–10 kg) of 18F-FDG approximately 40 min before the examination. The patients' blood glucose level was below 150 mg/dL at the time of FDG administration.

The examination started with a contrast-enhanced routine spiral CT scan from the vertex to the mid-thigh for attenuation correction using 60–80 ml of nonionic iodinated contrast material (OMNIPAQUE™ Iohexol injection, solution GE Healthcare Inc.) at 1.5–2 mL/s. The venous phase images were acquired 65 s post injection. The parameters of the CT scan were 130 kV, 80–150 mAs (CAREDose4D auto mAs), slice thickness of 5 mm, 512 × 512 reconstruction matrix, display matrix of 1024 × 1024, scan length – 1024 mm, transverse FOV – 700 mm, pitch of 0.95, 0.6 mm slice collimation, gantry rotation time of 0.6 s, and kernel B20s for reconstruction. Then, PET imaging was performed at 1 min/bed position for 7 beds, 4 mm slice thickness, 256 matrix and covering the same field of view using a Gaussian filter with FWHM of 5 mm and reconstructed with iterative plus Time of Flight method (attenuation-weighted, three iterations and 10 subsets, matrix size of 256, zoom of 1, isotropic CT resolution of 24 lp/mm with 0.21 mm uniform resolution throughout the Field of View) and temporal resolution up to 105 ms.

Whole-body PET and CT images in DICOM 3.0 format were loaded on three-dimensional workstations for visual evaluation and data analysis (Siemens Syngo. via VB10, Siemens AG, Healthcare Sector, Erlangen, Germany). On CECT, disease sites were identified in the presence of lytic or sclerotic bony lesions with or without associated soft tissue mass, abnormal postcontrast enhancement. In PET, abnormality was detected if there was increased FDG uptake with SUVmax higher than physiologic hepatic background activity (SUVmax). Interpretation was conducted by three experienced radiologists blinded to histology results.

Radiomics pipeline

Radiomic feature extraction

LifeX software v7.0[5] was used to segment and extract radiomic features from unfiltered PET and CT (1.5 mm slice thickness, venous phase reconstructed with B20s filter) images. Semi-automated segmentation of attenuation corrected PET images was done by selecting an absolute SUVmax threshold of 2.2. Bin size was 0.7936508 and the number of gray levels was 64 in intensity discretization for PET images. An absolute intensity rescaling of minimum bounds of zero and maximum of 50 was selected. For CT images, bin size was 10, and the number of gray levels was 400 for intensity discretization. Kernel 3 was used and an intensity rescaling of minimum bound of −1000 and maximum bound of 3000 was used. A circular 3D region of interest (ROI) in the area of most FDG avid bone lesion was chosen [Figure 1] and a total of 138 imaging biomarker standardization initiative-compliant first- and second-order texture features were extracted under first-order features – conventional PET/CT parameters (SUV and TLG), histogram (HISTO), and shape value and second-order features – gray-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM), gray-level run-length matrix (GLRLM), neighborhood gray-level different matrix (NGLDM), and gray-level zone length matrix (GLZLM) [Supplementary Table 1]. A similar process was followed for CT images (1.5 mm slice thickness venous phase images) where 3D ROIs were manually drawn in the area of the most visually (independent) destructive lytic bone lesions or soft tissue mass. The PET and CT ROIs did not always correspond to the same lesion and were kept at nearly equal sizes for uniformity.

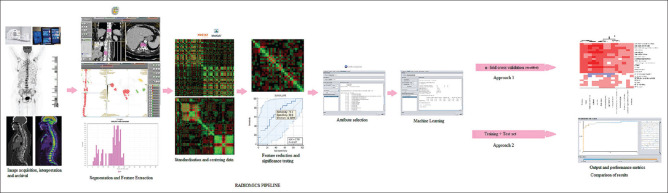

Figure 1.

Radiomics pipeline utilized in the study

Table S1.

List of first and second order unfiltered parameters extracted from PET and CT images on LifeX software

| First order | Second order |

|---|---|

| 1.Conventional/Discretized CONV/DISCRET_min, mean, max, std) CONV/DISCRET_peak 0.5 mL CONV/DISCRET_peak 1 mL CONV/DISCRET_CAS CONV/DISCRET_TLG (for TP, MN) CONV/DISCRET_RIM_(min, mean, sd, max) CONV/DISCRET_(Q1, Q2, Q3) 2. Histogram (HISTO): The histogram features consist of simple statistics that are asso- ciated with pixel values in images while the spatial patterns of the pixel values are not included. Entropy and energy are calculated. HISTO_Skewness HISTO_Kurtosis HISTO_Entropy_log10 HISTO_Entropy log2 HISTO_Energy AUC_CSH 3.Shape value Shape_Sphericity Shape_Compacity Shape_Volume_mL Shape_Volume_vx Shape_SurfaceArea |

1.Gray Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM) GLCM_Homogeneity GLCM_Energy GLCM_Contrast GLCM_Correlation GLCM_Entropy GLCM_Dissimilarity 2.Gray-Level Run Length Matrix (GLRLM)- The GLRLM describes the number of the consecutive pixels of the same gray-level value for 4 directions in 2D or 13 directions in 3D GLRLM_SRE (Short run emphasis) GLRLM_LRE (Long run emphasis) GLRLM_LGRE (Low gray-level run emphasis) GLRLM_HGRE (High gray-level run emphasis) GLRLM_SRLGE (Short run low gray-level emphasis) GLRLM_SRHGE (Short run high gray-level emphasis) GLRLM_LRGLE (Long run low gray-level emphasis) GLRLM_LRHGE (Long run high gray-level emphasis) GLRLM_GLNU (Gray-level non-uniformity) GLRLM_RLNU (Run length non-uniformity) GLRLM_RP (Run percentage) 3.Neighborhood Gray-Level Different Matrix (NGDLM): Described the difference of grey levels between adjacent voxels in 2D and 26 in 3D NGLDM_Coarseness NGLDM_Contrast NGLDM_Busyness 4. Gray-Level Zone Length Matrix (GLZLM) : Describes the number of homogenous zones of the same grey level value in 2D or 3D GLZLM_SZE (Short-zone emphasis) GLZLM_LZE (Long-zone emphasis) GLZLM_LGZE (Low gray-level zone emphasis) GLZLM_HGZE (High gray-level zone emphasis) GLZLM_SZLGE (Short-zone low gray-level emphasis) GLZLM_SZHGE (Short-zone high gray-level emphasis) GLZLM_LZGLE (Long-zone low gray-level emphasis) GLZLM_LZHGE (Long-zone high gray-level emphasis) GLZLM_GLNU (Gray-level non-uniformity for zone) GLZLM_ZLNU (Zone length non-uniformity) GLZLM_ZP (Zone percentage) |

HISTO: Histogram, GLCM: Gray level co-occurrence matrix, GLRLM: Gray-level run-length matrix, SRE: Short-run emphasis, LRE: Long-run emphasis, LGRE: Low gray-level run emphasis, HGRE: High gray-level run emphasis, SRLGE: Short-run low gray-level emphasis, SRHGE: Short-run high gray-level emphasis, LRGLE: Long-run low gray-level emphasis, LRHGE: Long-run high gray-level emphasis, GLNU: Gray-level nonuniformity, RLNU: Run-length nonuniformity, RP: Run percentage, NGDLM: Neighborhood gray-level different matrix, GLZLM: Gray-level zone length matrix, SZE: Short-zone emphasis, LZE: Long-zone emphasis, LGZE: Low gray-level zone emphasis, HGZE: High gray-level zone emphasis, SZLGE: Short-zone low gray-level emphasis, SZHGE: Short-zone high gray-level emphasis, LZGLE: Long-zone low gray-level emphasis, LZHGE: Long-zone high gray-level emphasis, ZLNU: Zone length nonuniformity, ZP: Zone percentage, AUC: Area under the curve, PET: Positron-emission tomography, CT: Computed tomography, CSH: : Cumulative standardized uptake value (SUV)-volume histogram , CAS: Calcium Agatston Score, TLG: Total Lesion Glycolysis, RIM: Radial Intensity Mean

Feature preprocessing and dimension reduction

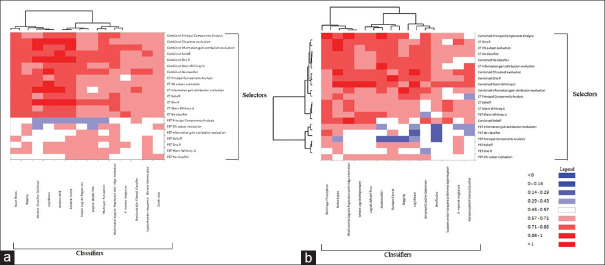

Receiver operating curve (ROC) analysis was done using MedCalc® statistical software[6] for the 138 texture parameters extracted for both PET and CT selecting those most significantly correlated to the outcome (P < 0.05) in both groups. 19 PET and 16 CT parameters were found to be significant. The data obtained for all 138 parameters were of different ranges and hence were standardized (n-1) resulting in a matrix with values ranging from −1 to +1. A correlation matrix using Karl Pearson coefficient of correlation (r) between all the variables showed two clusters of significant correlation [Figure 2a and b]. Highly correlated parameters were removed to yield a final matrix of 16 CT and 14 PET parameters with majority of the parameters having an r < 0.5 and VIF (variation inflation fFactor) of <10, thus mitigating the issue of multicollinearity [Figure 3abc]. While pruning the correlation matrix, parameters with P > 0.05 on ROC curve analysis were preferentially discarded. Multivariate analysis of features is more reliable than bivariate analysis. Features selected after filtering the correlation matrix were given precedence over features with a significance of 5% in ROC analysis. [Supplementary Table 2].

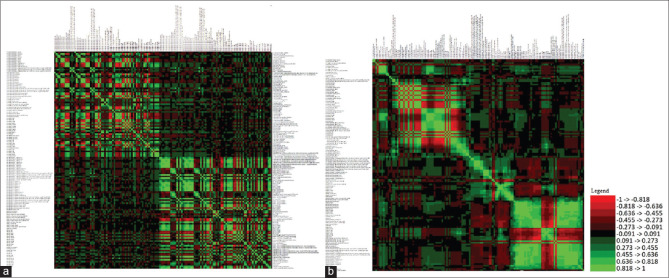

Figure 2.

Pearson's correlation matrix of all parameter values. (a) Absolute values before and (b) after standardizing (n = 1) and centering

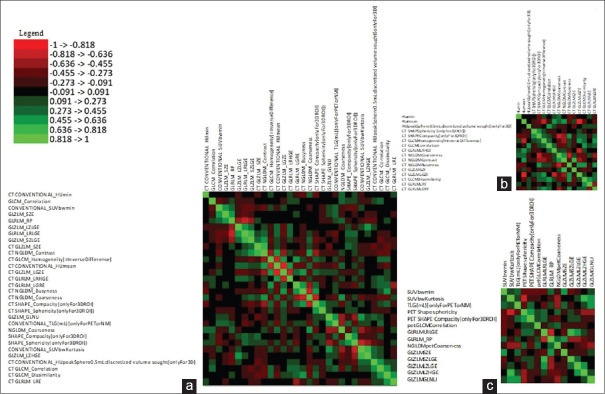

Figure 3.

Pearson's correlation matrix of absolute r values after filtering redundant and multicollinear features for combined positron-emission tomography and computed tomography (a), C (b) and positron-emission tomography (c) data

Table S2.

Features in PET and CT images selected with high area under ROC (significance of 5%) versus features selected after filtering Pearson correlation matrix

| Features with high area under ROC (significance of 5%) | Features selected after filtering Pearson correlation matrix |

|---|---|

| PET CONVENTIONAL_SUVbwmean CONVENTIONAL_SUVbwQ1 CONVENTIONAL_SUVbwQ2 CONVENTIONAL_SUVbwQ3 DISCRETIZED_AUC_CSH SHAPE_Compacity[onlyFor3DROI] GLCM_Homogeneity[=InverseDifference] GLRLM_SRE GLRLM_LRE GLRLM_LRLGE GLRLM_RP NGLDM_Contrast GLZLM_SZE GLZLM_LZE GLZLM_LGZE GLZLM_SZHGE GLZLM_LZLGE GLZLM_LZHGE GLZLM_ZP CT CONVENTIONAL_HUmin DISCRETIZED_HUmin SHAPE_Volume (mL) SHAPE_Volume (vx) SHAPE_Compacity[onlyFor3DROI] GLRLM_LRHGE GLRLM_GLNU GLRLM_RLNU NGLDM_Coarseness NGLDM_Busyness GLZLM_LGZE GLZLM_HGZE GLZLM_SZLGE CT GLRLM_LGRE GLRLM_SRLGE GLRLM_SRE |

PET CONVENTIONAL_SUVbwmin CONVENTIONAL_SUVbwKurtosis CONVENTIONAL_TLG (mL)[onlyForPETorNM] SHAPE_Sphericity[onlyFor3DROI]) SHAPE_Compacity[onlyFor3DROI] GLCM_Correlation GLRLM_LRLGE GLRLM_RP NGLDM_Coarseness GLZLM_SZE GLZLM_SZLGE GLZLM_LZLGE GLZLM_LZHGE GLZLM_GLNU CT CT CONVENTIONAL_HUmin CT CONVENTIONAL_HUmean CT CONVENTIONAL_HUpeakSphere0.5mL: discretized volume sought[onlyFor3D] CT SHAPE_Sphericity[onlyFor3DROI]) CT SHAPE_Compacity[onlyFor3DROI] CT GLCM_Homogeneity[=InverseDifference] CT GLCM_Correlation CT GLRLM_LRHGE CT NGLDM_Coarseness CT NGLDM_Contrast CT NGLDM_Busyness CT GLZLM_SZE CT GLZLM_LGZE CT GLCM_Dissimilarity CT GLRLM_LRE CT GLRLM_LGRE |

GLCM: Gray level co-occurrence matrix, GLRLM: Gray-level run-length matrix, SRE: Short-run emphasis, LRE: Long-run emphasis, LGRE: Low gray-level run emphasis, SRLGE: Short-run low gray-level emphasis, LRLGE: Long-run low gray-level emphasis, LRHGE: Long-run high gray-level emphasis, GLNU: Gray-level nonuniformity, RLNU: Run-length nonuniformity, RP: Run percentage, NGLDM: Neighborhood gray-level different matrix, GLZLM: Gray-level zone length matrix, SZE: Short-zone emphasis, LZE: Long-zone emphasis, LGZE: Low gray-level zone emphasis, HGZE: High gray-level zone emphasis, SZLGE: Short-zone low gray-level emphasis, SZHGE: Short-zone high gray-level emphasis, LZGLE: Long-zone low gray-level emphasis, LZHGE: Long-zone high gray-level emphasis, ZLNU: Zone length nonuniformity, ZP: Zone percentage, AUC: Area under the curve, ROC: Receiver operating curve, PET: Positron-emission tomography, CT: Computed tomography, CSH: Cumulative standardized uptake value (SUV)-volume histogram, SUV: Standardised Uptake Value

Radiomic feature and selection

The final set of 16 CT and 14 PET parameters was individually subjected to 6 feature selection algorithms using Weka Data Mining v3.8.5[7] and XLSTAT statistical software v2021.2 with 10-fold stratified cross-validation. A seventh method employed all the values (no selection).

Machine learning and model validation

Up to 5 of the most relevant features in each of the resulting PET and CT selections were subject to 14 machine-learning classifiers via two approaches – the first using 10-fold cross-validation and the second using independent random training and test samples (26:14). This was done instead of a hold-out strategy in view of the small dataset. This yielded a total of 588 confusion matrices and AUC outputs. Machine-learning algorithms were performed in Weka Data Mining v3.8.5 and XLSTAT software with randomization with random seed of 1 [Table 1]. The highest AUC values were selected for 5 CT, PET, and combined parameters with each approach. From these, the feature selector-classifier combination with the highest AUC was selected and those 5 CT and 5 PET parameters were then subject to the same selection and classification process. The selector-classifier combination with the highest AUC was selected as the most appropriate and the parameters used in building the model were denoted as the most significant ones in each approach to differentiate skeletal metastases from multiple myeloma.

Table 1.

Attribute selection and machine-learning classification methods along with the protocol used in the study

| Attribute evaluator + search method | Classifier |

|---|---|

| 1. CFS subset evaluator + greedy stepwise 2. Information gain attribute evaluator + ranker 3. Principal components analysis + ranker* 4. ReliefF attribute evaluator + ranker - number of nearest neighbors (k): 10 Equal influence nearest neighbors 5. OneRules attribute evaluator + ranker 6. Mann–Whitney U-test with P<0.05 7. No selection |

1. Naive Bayes updateable 2. OneRules 3. Multinomial logistic regression using a ridge estimator - logistic regression with ridge parameter of 1.0E-8 4. Simple logistic regression 5. Multilayer perceptron using sigmoid nodes 6. Logistic model tree – LM_1: 6/6 (40) Number of leaves: 1, size of the tree: 1 7. Random forest - bagging with 100 iterations and base learner 8. AdaBoostM1, weight: 0.25 Number of performed iterations: 10 9. Bagging – bagging with 10 iterations and base learner 10. Iterative classifier optimizer 11. Randomizable filtered classifier - IB1 instance-based classifier using 1 nearest neighbor (s) for classification 12. K-Nearest neighbors – IB1 instance-based classifier using 1 nearest neighbour (s) for classification 13. Support vector machine using sequential minimal optimization - IB1 instance-based classifier using 1 nearest neighbor (s) for classification 14. LogitBoost – number of performed iterations: 10 |

*All feature selection and classification methods were 10-fold cross-validated (stratified) with seed value=1 except for principal components analysis + ranker. Confusion matrices were obtained for each classifier along with performance metrics. CFS: Correlation-based feature selection

Statistical analysis

T-test for independent samples was done to assess variability in the distribution of sexes between both groups. Mann–Whitney U-test was done to compare the ages of both groups. Histopathology was regarded as the gold standard according to which metastases and myeloma groups were divided.

The feature selection methods employed 10-fold stratified cross-validation for increased robustness.

In view of the small sample size, a hold-out three-step training, validation, and independent testing were not feasible. Hence, two approaches were adopted and compared: 10-fold stratified cross-validation and independent training and test sets (26:14). When the dataset is too small to employ a hold-out strategy with train/validation/test splits, cross-validation can be used to replace the inner train/validation split of model selection and also outer (train/test) split of model evaluation which we have employed in the first approach.[8]

The quality of the performance of the models was assessed by MSE, RMSE, kappa statistic, AUC, area under the precision-recall curve, F-measure, and Matthews correlation coefficient.

Results

Demographic analysis

Fourteen patients were male and 6 females in the metastases group, whereas the myeloma group had 12 male and 8 female patients. T-test for independent samples was not significant at 5% (P = 1.0)

The mean age in the metastases group was 52.2 ± 19.48 years and in the myeloma group was 61.95 ± 8.47 years. Mann–Whitney test U-value was 126.5 for age. The critical value of U at P < 0.05 was 127. Therefore, it was a significant result at P < 0.05. According to data from various population-based cancer registries under the National Cancer Registry Programme, majority of the newly diagnosed MM cases (31.1%, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 29.1%–33.2%) in India belonged to the 60–69 years age group.[9] However, more recent studies show that the younger patients are increasingly being affected with a median age of 55 years.[10]

Advancing age is the most important risk factor for cancer overall and India exhibits heterogeneity in cancer with lung, oral, stomach, and nasopharyngeal cancers being the most common in men and breast and uterine cervical cancers the most common in women.[11] The risk of developing cancer before the age of 75 years was 10.4% in India (International Agency for Research on Cancer, WHO, March 2021), and bone metastases usually present at an advanced stage. The most common cancers that spread to the bone are cancers of the breast, prostate, lung, kidney, and thyroid. The mean age seen in our sample could be a combination of the chosen sample, aggressive malignancies, delay in diagnosis, or treatment failures.

The metastases group included two cases of lung carcinoma, four cases of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (ALK + large cell, T-cell, high grade, and DLBCL), one case of secondary Hodgkin's lymphoma, four cases of leukemia (two B-cell acute lymphoid leukemia, one small lymphocytic leukemia, one acute myeloid leukemia [AML] coexisting with metastatic rhabdomyosarcoma, and one AML coexisting with adenocarcinoma colon), one case each of adenocarcinoma breast and pancreas, two cases of adenocarcinoma prostate, one case of squamous cell carcinoma of esophagus, one case of high-grade transitional cell carcinoma of urinary bladder, and one case of metastatic carcinomatous deposits from an unknown epithelial primary site.

Receiver operating curve analysis results

ROC analysis revealed 19 PET and 16 CT parameters which were significantly correlated to outcome (P < 0.05) with the highest significance for Discretized HU_min and NGLDM_Coarseness (P = 0.007) in CT and for GLZLM_ZP (P = 0.009) for PET. Most features in the original dataset were redundant due to multicollinearity and were removed by pruning the correlation matrix so that majority of features had r < 0.5 while preferentially preserving the parameters with P < 0.05 in the ROC analysis. This resulted in a feature set of 16 CT and 14 PET parameters.

Two-tailed t-test for independent samples at 5% significance for these parameters with significant ROC and those obtained after correlation matrix filtering revealed that the metastases group showed significantly higher mean CT conventional HU_min (t = 2.30, P = 0.0268), discretized HU_min (t = 2.27, P = 0.0286), CT NGLDM_Coarseness (t = −2.52, P = 0.0158), CONVENTIONAL_SUVbwQ1 (t = 2.02, P = 0.0496), PET GLRLM_SRE (t = 2.14, P = 0.0381), PET GLZLM_SZE (t = 2.35, P = 0.0240), and PET GLZLM_ZP (t = 2.14, P = 0.0383). CT Shape_Compacity (t = 2.78, P = 0.0084), PET SHAPE_Compacity (t = −2.26, P = 0.0294), PET GLRLM_LRE (t = −2.18, P = 0.0353), and PET GLRLM_RP (t = 2.40, P = 0.0214) were higher in the myeloma group. Hence, the majority of the parameters suggested that metastases were finer textured on CT and PET and had lower minimum HU than myelomas. On the other hand, myelomas had a more compact shape relative to a sphere.

Parameters

Computed tomography

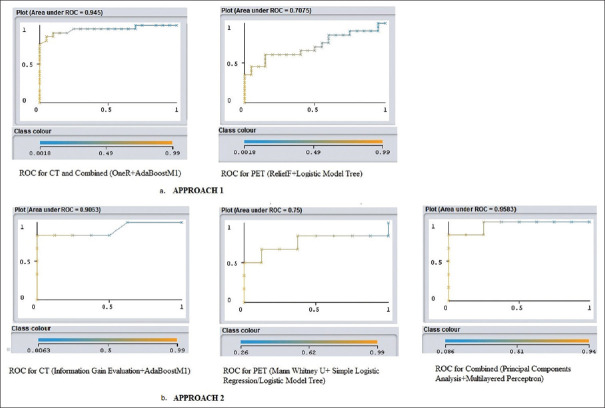

In the first approach, highest AUC of 0.945 for 5 CT parameters (CT NGLDM_Coarseness, CT GLZLM_LGZE, CT GLCM_Dissimilarity, CT GLRLM_LRE and CT GLRLM_LGRE) was obtained using OneR selector and AdaBoostM1 classifier (κ = 0.75, MSE = 0.1996, RMSE = 0.3106, F = 0.875, MCC = 0.751 and PRC = 0.943). The highest combined AUC was the same as the AUC for the CT parameters.

In the second approach, highest AUC of 0.9063 for 5 CT parameters (CT NGLDM_Coarseness, CT Shape_Compacity for 3D ROI, CT GLCM_Correlation, CT GLCM_Homogeneity [=InverseDifference and CT GLRLM_LGRE] was obtained using Information Gain Evaluation selector and AdaBoostM1 classifier (κ =0.5714, MSE = 0.2175, RMSE = 0.3601, F = 0.786, MCC = 0.577 and PRC = 0.914).

Comparison of AUCs showed a difference of −0.0387 (SE = 0.476, Z statistic = −0.0814, and P = 0.9351).

Positron-emission tomography

In the first approach, highest AUC of 0.7075 for 5 PET parameters (Shape_Compacity for 3D ROI, GLRLM_RP, GLZLM_SZLGE, GLZLM_SZE and GLZLM_LZLGE) was obtained using RelieF selector and Logistic Model Tree classifier (κ = 0.15, MSE = 0.4125, RMSE = 0.4852, F = 0.605, MCC = 0.152 and PRC = 0.782).

In the second approach, highest AUC of 0.75 for 5 PET parameters (Shape_Compacity for 3D ROI, GLRLM_RP, GLRLM_LRLGE, GLZLM_LZHGE and GLZLM_LZLGE) was obtained using Mann–Whitney U-test as selector and logistic model tree/simple logistic regression analysis as classifier (κ =0.075, MSE = 0.4591, RMSE = 0.5461, F = 0. 5, MCC = 0.101, and PRC = 0.761).

Comparison of AUCs showed a difference of − 0.0425 (SE = 0.731, Z statistic = −0.0582 and P = 0.9536).

Combined

In the approach utilizing cross-validation for machine learning, highest AUC of 0.945 for 5 parameters (CT NGLDM_Coarseness, CT GLZLM_LGZE, CT GLCM_Dissimilarity, CT GLRLM_LRE and CT GLRLM_LGRE) was obtained using OneR selector and AdaBoostM1 classifier (TP = 0.875, FP = 0.125, Precision = 0.876, Recall = 0.875, κ =0.75, MSE = 0.1996, RMSE = 0.3106, F = 0.875, MCC = 0.751, and PRC = 0.943).

In the approach utilizing independent training and test sets, highest AUC of 0.9538 for 5 parameters (CT NGLDM_Coarseness, CT GLCM_Homogeneity [=InverseDifference], CT GLRLM_LGRE, CT SHAPE_Compacity [onlyFor3DROI], and PET GLRLM_LRGLE) was obtained using principal components analysis selector + multilayered perceptron classifier (TP = 0.857, FP = 0.107, Precision = 0.893, Recall = 0.857, κ =0.72, MSE = 0.2532, RMSE = 0.3282, F = 0.857, MCC = 0.75, and PRC = 0.965).

Comparison of AUCs showed a difference of −0.0088 (SE = 0.452, Z statistic = −0.0195 and P = 0.9845).

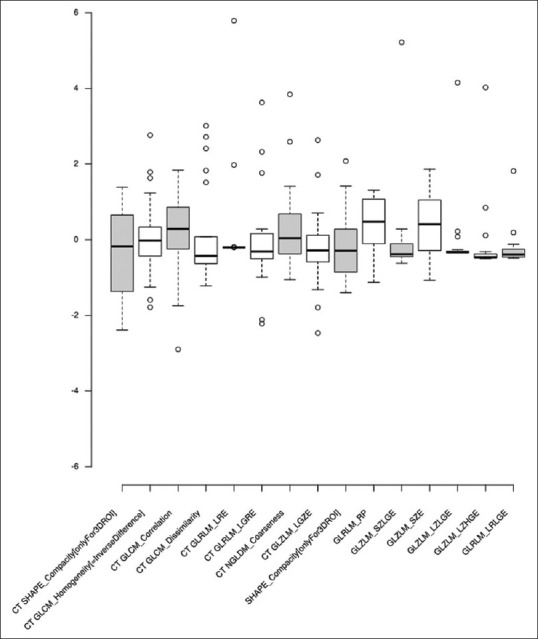

AUC values of the models created from CT and combined PET and CT parameters in both approaches are represented as heat maps [Figure 4a and b]. The ROCs for the highest performing models are plotted [Figure 5a and b]. Standardized PET [Figure 6] and CT [Figure 7] parameters used to train the models are represented as box plots.

Figure 4.

Heat map of the area under the curve values of positron-emission tomography, computed tomography, and combined parameters in the (a) first approach and (b) second approach

Figure 5.

Area under curve for five most predictive parameters in the a. first and b. second approaches

Figure 6.

Boxplot of the myeloma group standardized computed tomography and positron-emission tomography parameter values used in models in both approaches yielding the highest area under the curve values

Figure 7.

Boxplot of the metastases group standardized computed tomography and positron-emission tomography parameter values used in models in both approaches yielding the highest area under the curve values

CT SHAPE_Compacity (onlyFor3DROI), CT GLZLM_LGZE, CT GLCM_Dissimilarity, CT GLRLM_LGRE, and PET GLRLM_LRGLE were all higher for the myeloma group. CT NGLDM_Coarseness and CT GLCM_Homogeneity (=InverseDifference) were higher in the metastases group. CT GLRLM_LRE was higher in the metastases group owing to two outliers (one case of prostate carcinoma and one of T-cell NHL).

Discussion

Texture is a repeating pattern of local variations in image intensity and is undefinable for a point. A GLCM contains information about the positions of pixels having similar gray-level values. Correlation is a measure of image linearity. Correlation is high if an image contains a considerable amount of linear structure. A run length is a set of constant intensity pixels located in a line. Run-length statistics are calculated by counting the number of runs of a given length (from 1 to n) for each gray level. In a coarse texture, it is expected that long runs will occur relatively often, whereas a fine texture will contain a higher proportion of short runs.[12]

Neighboring gray-level dependence matrix (NGLDM) for texture classification was presented by Sun et al.[13] The major properties of this approach were as follows: (a) texture features can be easily computed for the overall texture; (b) they are essentially invariant under spatial rotation; and (c) they are invariant under linear gray-level transformation and can be made insensitive to monotonic gray-level transformation.[14] It was suggested as an alternative to the gray-level co-occurrence matrix. Coarseness is a measure of average difference between the center voxel and its neighborhood and is an indication of the spatial rate of change. A higher value indicates a lower spatial change rate and a locally more uniform texture.

Multiple myeloma is a genetically complex entity evolving from premalignant MGUS to smoldering MM and symptomatic disease. Owing to this, fewer studies have been performed in AI Radiomics and most of the available studies are new.[15] A recent study by Fiz et al.[16] radiomics in MM showed that radiomics improved the accuracy of diagnosis and characterization of focal and diffuse myeloma on CT by improving the area under the curve (AUC) of radiologists from 64% to 79%. In a study by Ripani et al.,[17] PET texture features, especially second- and higher-order texture features, showed a significant association with disease progression in areas of subtle distribution in the axial and peripheral bone marrow. Parameters extracted from VOIs placed on T5-T7 and L2-L4 did not significantly differ among the patients with regard to progression to symptomatic MM and length of time to progression, except for the GLZLM–short-zone low-gray-level emphasis (GLZLM_SZLGRE) and GLZLM–low gray-level zone emphasis (GLZLM_LGLZE). Yildirim and Baykara[18] reported minimum, median, and maximum gray-level parameters to be significantly higher in lytic bone metastases than multiple myeloma on HISTO analysis.

In a study by Xiong et al.,[19] T1 and T2 MRI feature extraction and machine-learning validation of 60 MM and 118 metastatic lesions revealed that the most discriminatory features derived from GLCM indicating intralesional heterogeneity. The study found that the entropy of metastases from T2WI images was higher than that of myelomas signaling a higher heterogeneity in the former. Multiple myeloma is classified as a small cell round tumor of bone. It is usually composed of uniform, round, or oval-shaped cells with highly packed arrangement with small interstitial spaces and high nuclear cytoplasmic ratio. Our study shows that while myelomas are more compact texturally, metastases were finer textured on CT and PET images. This may be due to intratumoral heterogeneity in the former. Since the sample size was small, tumors were at various stages of presentation in both groups and ROI selection bias, these findings must be substantiated in further large-scale radiomic-molecular correlation studies.

In a study by Schenone et al.,[20] preliminary results showed that MM is associated with extension of the intrabone volume for the whole body and that machine learning can identify CT image features mostly correlating with the disease evolution.

In a study by Tagliafico et al.,[21] 22 diffuse and 39 focal multiple myeloma cases found that 9 features were different (P < 0.05) in the diffuse and focal patterns (n = 2/9 features were shape-based: major axis length and sphericity; n = 7/9 were gray-level run-length matrix (GLRLM) based.

In a study by Mesguich et al.,[22] radiomics analysis of 18-FDG PET/CT images in 30 patients was done after visual analysis by MRI. A machine-learning model employing 5 radiomic features overcame the limitations of visual analysis by MRI yielding a highly accurate and more reliable diagnosis of diffuse bone marrow infiltration in multiple myeloma. A study by Morvan et al.[23] confirmed the predictive value of radiomics for MM patients, demonstrating that quantitative/heterogeneity image-based features reduce the error of the predicted progression.

A CT radiomics-based random forest model was more accurate in differentiating bone islands from osteoblastic metastases compared to an inexperienced radiologist in a study by Hong et al.[24] In a study by Mayerhoefer et al.,[25] 18F FDG-PET texture features improved SUV-based prediction of bone marrow involvement in mantle cell lymphoma.

In a study by Li and et al.,[26] 18F-FDG PET/CT radiomic analysis with a random forest machine-learning model provided a quantitative, objective, and efficient mechanism for identifying bone marrow infiltration in suspected relapsed AL. The authors suggested it particularly for diagnosis in cases with 18F-FDG diffuse uptake patterns.

In a study by Fan et al.[27] for the differential diagnosis of spinal metastases by 18F-FDG PETCT, there were 51 texture parameters that differed meaningfully between benign and malignant lesions, of which four had higher AUC than SUVmax. The texture parameters were input to build a classification model using logistic regression, support vector machine, and decision tree. The accuracy of classification was 87.5, 83.34, and 75%, respectively. The accuracy of the manual diagnosis was 84.27%.

A study by Shin et al.[28] inferred that there was a significant difference in SUVmax between benign and malignant musculoskeletal tumors in total (P < 0.002), soft tissue tumors (P < 0.05), and bone tumors (P < 0.02). Sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic accuracy were 80%, 65.2%, and 73% in total with cutoff SUV (max) 3.8; 80%, 68.4%, and 75% in the soft tissue tumors with cutoff SUV (max) 3.8; and 80%, 63%, and 70% in the bone tumors with cutoff SUV (max) 3.7.

18F-FDG PET can also show false-positive findings in Schmorl's nodes,[29] fractures,[30] and discontinuous degenerative disease and spinal tuberculosis; therefore; clinical and ancillary investigative data are needed for diagnosis.[31,32]

In a study by Kenawy et al.,[33] 44 patients with pathologically proven lymphoma analysis of ROC curves from PET radiomic images showed that high-intensity long-run emphasis 4 bin, high-intensity large zone emphasis 64 bin, long-run emphasis (LRE) 64 bin, large-zone emphasis 64 bin, max spectrum 8 bin, busyness 64 bin, and code similarity 32 and 64 bin were significant discriminators of bone marrow infiltration among other features (area under curve >0.682, P < 0.05). Univariate analyses of texture features showed that code similarity and long-run emphasis (both 64 bin) were significant predictors of bone marrow involvement. Multivariate analyses revealed that LRE (64 bin, P = 0.031) with an odds ratio of 1.022 and 95% CI of (1.002–1.043) were independent variables for bone marrow involvement, hence concluding that 18F-FDG PET-CT radiomic features are synergistic to visual assessment of bone marrow infiltration in lymphoma.

In a study by Eary et al.,[34] 18F-FDG PET tumor image heterogeneity analysis method was validated for the ability to predict patient outcome in a clinical population of patients with sarcoma. They indicated that this method can be extended to other PET image datasets in which heterogeneity in tissue uptake of a radiotracer may predict patient outcome.

This is a retrospective study of a small sample. One of the challenges of radiomic studies is high dimensionality and low sample size which leads to sparsity of data, overfitting, high probability of a false-positive result. This can affect the reproducibility and generalizability of the findings.[35] Tumor heterogeneity influencing PET and CECT metrics, choice of ROI, and sampling bias in histopathology are limiting factors.

Texture analysis has shown positive predictive and prognostic value in studies on many tumor types but is complicated by the definitions of what constitutes a parameter, number of parameters, and the number of ways in which they can be calculated. Variability can occur due to acquisition protocol, scanner type, quantitative corrections, voxels in the ROI, type of reconstruction algorithm and parameters, post-reconstruction processing, etc., These need to be reduced by statistical validation to remove redundant parameters, introducing process and parameter standardization, and robust machine-learning algorithms in the future.

Conclusions

This study aimed to evaluate the diagnostic capability of models based on first- and second-order texture features of PET and CT images in the differentiation of skeletal metastases and multiple myeloma. The most distinguishing features suggested that metastases were finer textured on CT and MRI with a lower minimum HU and myelomas had a more compact shape.

A larger multi-institutional study with standardized protocols and performance analysis of models in real-world scenarios would further modify the findings of this study. In addition, clinical-stage, hematological, molecular, genomic, and biochemical parameters could be added to strengthen the relationship between imaging, pathology, and laboratory data as they tend to be interrelated.

Integrated big data from the omics disciplines such as radiomics have the potential to development of models that predict intratumoral heterogeneity, complement and substantiate invasive tissue diagnosis, and pave the way for personalized medicine.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Gillies RJ, Kinahan PE, Hricak H. Radiomics: Images are more than pictures, they are data. Radiology. 2016;278:563–77. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2015151169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yochum TR, Rowe LJ. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Essentials of Skeletal Radiology; p. c2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenspan A, Jundt G, Remagen W. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams&Wilkins; Differential Diagnosis in Orthopaedic Oncology; p. c2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cavo M, Terpos E, Nanni C, Moreau P, Lentzsch S, Zweegman S, et al. Role of 18F-FDG PET/CT in the diagnosis and management of multiple myeloma and other plasma cell disorders: A consensus statement by the International Myeloma Working Group. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:e206–17. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30189-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nioche C, Orlhac F, Boughdad S, Reuzé S, Goya-Outi J, Robert C, et al. LIFEx: A freeware for radiomic feature calculation in multimodality imaging to accelerate advances in the characterization of tumor heterogeneity. Cancer Res. 2018;78:4786–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MedCalc Statistical Software Version 19.2.6 (MedCalc Software bv, Ostend, Belgium. 2020. [Last accessed on 2021 Jun 20]. Available from: https://www. medcalc.org .

- 7.Frank E, Hall MA, Witten IH. Online Appendix for “Data Mining: Practical Machine Learning Tools and Techniques”. 4th. San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann; 2016. The WEKA Workbench. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duchesnay E, Lofstedt T, Younes F. Engineering School. France: 2020. [Last accessed on 2021 Jun 18]. Statistics and Machine Learning in Python. Available from: http://hal 03038776v2 . [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bora K. Distribution of multiple myeloma in India: Heterogeneity in incidence across age, sex and geography. Cancer Epidemiol. 2019;59:215–20. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2019.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar L, Nair S, Vadlamani SP, Chaudhary P. Multiple myeloma: An update. J Curr Oncol. 2020;3:72–80. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mathur P, Sathishkumar K, Chaturvedi M, Das P, Sudarshan KL, Santhappan S, et al. Cancer statistics, 2020: Report From National Cancer Registry Programme, India. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:1063–75. doi: 10.1200/GO.20.00122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wirth MA. University of Guelph Computing and Information Science Image Processing Group ©2004. [Last accessed on 2021 Jun 21]. Available from: http://www.cyto.purdue.edu/cdroms/micro2/content/education/wirth06. pdf .

- 13.Sun C, Wee W. Neighboring gray level dependence matrix for texture classification. Comput Graph Image Process. 1982;20:297.. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zwanenburg A, Vallières M, Abdalah MA, Aerts HJ, Andrearczyk V, Apte A, et al. The image biomarker standardization initiative: Standardized quantitative radiomics for high-throughput image-based phenotyping. Radiology. 2020;295:328–38. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020191145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tagliafico AS, Dominietto A, Belgioia L, Campi C, Schenone D, Piana M. Quantitative imaging and radiomics in multiple myeloma: A potential opportunity? Medicina (Kaunas) 2021;57:94.. doi: 10.3390/medicina57020094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fiz F, Marini C, Piva R, Miglino M, Massollo M, Bongioanni F, et al. Adult advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia: Computational analysis of whole-body CT documents a bone structure alteration. Radiology. 2014;271:805–13. doi: 10.1148/radiol.14131944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ripani D, Caldarella C, Za T, Rossi E, De Stefano V, Giordano A. Progression to symptomatic multiple myeloma predicted by texture analysis-derived parameters in patients without focal disease at 18F-FDG PET/CT. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2021;21:536–44. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2021.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yildirim M, Baykara M. Differentiation of multiple myeloma and lytic bone metastases: Histogram analysis. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2020;44:953–5. doi: 10.1097/RCT.0000000000001086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiong X, Wang J, Hu S, Dai Y, Zhang Y, Hu C. Differentiating between multiple myeloma and metastasis subtypes of lumbar vertebra lesions using machine learning-based radiomics. Front Oncol. 2021;11:601699.. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.601699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schenone D, Lai R, Cea M, Rossi F, Torri L, Bignotti B, et al. Radiomics and artificial intelligence analysis of CT data for the identification of prognostic features in multiple myeloma. Proc SPIE. 2020;11314:1605–7422. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tagliafico AS, Cea M, Rossi F, Valdora F, Bignotti B, Succio G, et al. Differentiating diffuse from focal pattern on computed tomography in multiple myeloma: Added value of a radiomics approach. Eur J Radiol. 2019;121:108739.. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2019.108739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mesguich C, Hindie E, de Senneville BD, Tlili G, Pinaquy JB, Marit G, et al. Improved 18-FDG PET/CT diagnosis of multiple myeloma diffuse disease by radiomics analysis. Nucl Med Commun. 2021;42:1135–43. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0000000000001437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morvan L, Carlier T, Jamet B, Bailly C, Bodet-Milin C, Moreau P, et al. Leveraging RSF and PET images for prognosis of multiple myeloma at diagnosis. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg. 2020;15:129–39. doi: 10.1007/s11548-019-02015-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hong JH, Jung JY, Jo A, Nam Y, Pak S, Lee SY, et al. Development and validation of a radiomics model for differentiating bone islands and osteoblastic bone metastases at abdominal CT. Radiology. 2021;299:626–32. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2021203783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mayerhoefer ME, Riedl CC, Kumar A, Dogan A, Gibbs P, Weber M, et al. [18F] FDG-PET/CT radiomics for prediction of bone marrow involvement in mantle cell lymphoma: A retrospective study in 97 patients. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:1138.. doi: 10.3390/cancers12051138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li H, Xu C, Xin B, Zheng C, Zhao Y, Hao K, et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT radiomic analysis with machine learning for identifying bone marrow involvement in the patients with suspected relapsed acute leukemia. Theranostics. 2019;9:4730–9. doi: 10.7150/thno.33841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fan X, Zhang H, Yin Y, Zhang J, Yang M, Qin S, et al. Texture analysis of 18F-FDG PET/CT for differential diagnosis spinal metastases. Front Med (Lausanne) 2020;7:605746.. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.605746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shin DS, Shon OJ, Han DS, Choi JH, Chun KA, Cho IH. The clinical efficacy of (18) F-FDG-PET/CT in benign and malignant musculoskeletal tumors. Ann Nucl Med. 2008;22:603–9. doi: 10.1007/s12149-008-0151-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Z, Ma D, Yang J. 18F-FDG PET/CT can differentiate vertebral metastases from Schmorl's nodes by distribution characteristics of the 18F-FDG. Hell J Nucl Med. 2016;19:241–4. doi: 10.1967/s002449910406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shon IH, Fogelman I. F-18 FDG positron emission tomography and benign fractures. Clin Nucl Med. 2003;28:171–5. doi: 10.1097/01.RLU.0000053508.98025.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gao X, Ye XD, Yuan Z, Yang CS. Non-contiguous spinal tuberculosis with a previous presumptive diagnosis of lung cancer spinal metastases. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;45:e178.. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezu047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosen RS, Fayad L, Wahl RL. Increased 18F-FDG uptake in degenerative disease of the spine: Characterization with 18F-FDG PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:1274–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kenawy MA, Khalil MM, Abdelgawad MH, El-Bahnasawy HH. Correlation of texture feature analysis with bone marrow infiltration in initial staging of patients with lymphoma using 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography combined with computed tomography. Pol J Radiol. 2020;85:e586–94. doi: 10.5114/pjr.2020.99833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eary JF, O'Sullivan F, O'Sullivan J, Conrad EU. Spatial heterogeneity in sarcoma 18F-FDG uptake as a predictor of patient outcome. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:1973–9. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.053397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park JE, Park SY, Kim HJ, Kim HS. Reproducibility and generalizability in radiomics modeling: Possible strategies in radiologic and statistical perspectives. Korean J Radiol. 2019;20:1124–37. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2018.0070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]