Abstract

Haemophilus ducreyi is a gram-negative obligate human pathogen that causes the genital ulcer disease chancroid. Chancroid lesions are deep necrotic ulcers with an immune cell infiltrate that includes macrophages. Despite the presence of these phagocytic cells, chancroid ulcers can persist for months and live H. ducreyi can be isolated from these lesions. To analyze the interaction of H. ducreyi with macrophages, we investigated the ability of H. ducreyi strain 35000 to adhere to, invade, and survive within U-937 cells, a human macrophage-like cell line. We found that although H. ducreyi strain 35000 adhered efficiently to U-937 cells, few bacteria were internalized, suggesting that H. ducreyi avoids phagocytosis by human macrophages. The few bacteria that were phagocytosed in these experiments were rapidly killed. We also found that H. ducreyi inhibits the phagocytosis of a secondary target (opsonized sheep red blood cells). Antiphagocytic activity was found in logarithmic, stationary-phase, and plate-grown cultures and was associated with whole, live bacteria but not with heat-killed cultures, sonicates, or culture supernatants. Phagocytosis was significantly inhibited after a 15-min exposure to H. ducreyi, and a multiplicity of infection of approximately 1 CFU per macrophage was sufficient to cause a significant reduction in phagocytosis by U-937 cells. Finally, all of nine H. ducreyi strains tested were antiphagocytic, suggesting that this is a common virulence mechanism for this organism. This finding suggests a mechanism by which H. ducreyi avoids killing and clearance by macrophages in chancroid lesions and inguinal lymph nodes.

Haemophilus ducreyi is a gram-negative, obligate human pathogen that causes chancroid, a sexually transmitted genital ulcer disease. Chancroid lesions involve cells of the epidermis and dermis and contain an immune cell infiltrate consisting of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs), T cells, and macrophages (2, 25, 26, 42, 43). Despite this immune cell infiltrate, viable H. ducreyi can be isolated from these ulcers weeks or months after initial infection (31). Inguinal lymphadenopathy occurs in up to 50% of untreated chancroid cases, and viable H. ducreyi can be isolated from infected lymph nodes (31). The mechanism used by H. ducreyi to persist and cause disease at these sites despite the presence of an apparently vigorous immune response is not understood.

Several potential virulence factors have been identified in H. ducreyi, including the cell-associated hemolysin (33, 48, 50), the secreted cytolethal distending toxin (8, 36), lipooligosaccharide (4), a hemoglobin uptake protein (11), a serum resistance protein (3, 12) and PAL, a peptidoglycan-associated lipoprotein (14). The target cell ranges of the two known H. ducreyi toxins, hemolysin and cytolethal distending toxin, have been studied in some detail. The cell-associated hemolysin lyses human foreskin epithelial cells (keratinocytes), fibroblasts, and immune cells including macrophages, T cells, and B cells and may thus contribute to tissue destruction and immune evasion (34, 50). The secreted cytolethal distending toxin is thought to contribute to immune evasion by inhibiting the proliferation of T cells and inducing apoptosis (17). Epithelial cells treated with cytolethal distending toxin become enlarged, arrest in the G2 phase, and die several days following exposure (8, 9, 36). Both cytolethal distending toxin and hemolysin may thus contribute to the formation of ulcers, evasion of the immune response, and the delayed healing common to chancroid (8, 9, 36).

Because H. ducreyi survives in the presence of macrophages, both in chancroid lesions and in regional lymph nodes, we studied the interactions of H. ducreyi with the human macrophage-like cell line, U-937 (45). We found that H. ducreyi inhibits phagocytosis of both itself and a secondary phagocytosis target, opsonized sheep red blood cells (SRBC). The results of this study suggest a mechanism by which H. ducreyi avoids immune clearance in the human host.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are described in Table 1. Plasmid pJL300, H. influenzae Rd, H. ducreyi strain CIP542, and H. ducreyi strain HMC56 were gifts from Eric Hansen (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center), Marilyn Roberts (University of Washington), Leslie Slaney (University of Manitoba), and M. R. de Quinones (Instituto Dermatologico, Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic), respectively. H. ducreyi was cultured on chocolate agar plates or in Hd broth containing 10% fetal bovine serum (49); Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium were cultured on Luria-Bertani plates or broth (41). H. influenzae was grown on chocolate agar plates or in Hd broth lacking fetal bovine serum.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Bacterial strain | Relevant characteristic | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| HB101 | Noninvasive strain, negative control | 27 |

| DH5α(pJL300) | E. coli expressing plasmid-encoded cdtABC | 44 |

| S. enterica serovar Typhimurium SL1344 | Virulent strain, positive control for macrophage survival | 16, 21 |

| H. influenzae Rd | Avirulent strain, negative control | 38 |

| H. ducreyi | ||

| 35000 | Wild-type strain isolated in Winnepeg, Canada, in 1976 | 10, 19 |

| 35000ΔAPC | 35000 hhdA::cat, nonhemolytic, Cmr | 50 |

| LA228R | Rabbit-passaged, wild-type strain isolated in Los Angeles, Calif., in 1982 | 10, 47 |

| CHIA | Wild-type strain stocked in VDRL stock collection (Atlanta, Ga.) in 1958 | 10, 20 |

| V-1168 | Wild-type strain isolated in Seattle, Wash., in 1980 | 10, 46 |

| CIP A75 | Wild-type strain isolated in London, England, in 1952 | 10, 32 |

| CIP A77 | Wild-type strain isolated in London, England, in 1952 | 10, 32 |

| HMC56 | Wild-type strain isolated in the Dominican Republic in 1995 | 10 |

| HMC62 | Wild-type strain isolated in Thailand in 1984 | 10 |

| HMC64 | Wild-type strain isolated in Kenya in 1984 | 10, 20 |

Bacterial adherence, uptake, and intracellular survival assays.

The human macrophage-like cell line U-937 (45) was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, Va.) and cultured routinely in RPMI medium containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 100 μg each of ampicillin and streptomycin per ml. Adherence to and phagocytosis by U-937 cells was measured as follows. U-937 cells were plated in 24-well tissue culture plates at a density of 5 × 105 cells per well in medium containing 100 ng of phorbal myristate acetate (PMA; Sigma) per ml of to induce differentiation and adherence (23). After 48 h, the medium containing nonadherent cells was aspirated and the adherent U-937 cells were cultured for an additional 24 h in medium lacking PMA. The U-937 cells were washed three times in PBS, and then 1 ml of medium (without ampicillin and streptomycin) containing ∼5 × 106 CFU was added. The bacteria were centrifuged onto the U-937 cells at 150 × g for 10 min and then incubated at 33°C in humidified 5% CO2–95% air for 30 min to allow phagocytosis or invasion. The nonadherent bacteria were then removed by washing three times with PBS. The U-937 cells in one set of three wells were lysed with trypsin-EDTA, and the total number of cell-associated (adherent and intracellular) bacteria was determined by dilution plate counts. The remaining wells were treated with gentamicin (30 μg/ml of RPMI) for 30 min to kill extracellular bacteria. The 0-h wells were then washed, the U-937 cells were lysed, and bacterial plate counts were done. The 6- and 24-h wells were incubated for an additional 5 or 23 h, respectively, in medium containing 3 μg of gentamicin per ml and then washed, the U-937 cells were lysed, and the bacteria were plated as described above. We have previously shown that H. ducreyi 35000, E. coli HB101, and S. enterica SL 1344 do not differ in their susceptibility to gentamicin (50).

Opsonization of SRBCs.

SRBCs (150 μl of defibrinated sheep blood; PML Microbiologicals, Wilsonville, Oreg.) were washed in 150 mM NaCl, resuspended in 3 ml of 150 mM NaCl containing 6 μl of anti-SRBC antiserum (Rockland Immunochemicals), and then incubated at 37°C with shaking for 30 min. Opsonized SRBCs were then centrifuged for 5 min at 300 × g, resuspended in 3 ml of 150 mM NaCl, and added to the phagocytosis assay mixture as described below.

Phagocytosis assays.

Phagocytosis assays were performed using U-937 cells treated with PMA as described above, except that the U-937 cells were allowed to adhere to glass coverslips placed in the tissue culture wells. Bacterial cultures were microcentrifuged for 1 min and then resuspended to an optical density at 540 nm of 0.7 to 1.0 in RPMI containing 10% fetal bovine serum. A 100-μl volume of bacterial suspension was added to each well, and the wells were incubated at 33°C in humidified 5% CO2–95% air for 60 min. Note that the bacteria were not centrifuged onto the U-937 cells except in the dose response experiment (see Fig. 6), in which centrifugation for 10 min at 150 × g was used to synchronize contact with the U-937 cells. Opsonized or nonopsonized SRBCs (100 μl) were added, and the mixture was centrifuged for 2 min at 150 × g. The plate was then incubated at 37°C in humidified 5% CO2–95% air for 60 min to allow phagocytosis. Extracellular SRBCs were lysed with distilled water as previously described (23). The coverslips were then fixed in methanol, mounted on glass slides, and stained with the Diff-Quik stain set (Dade Diagnostics, Aguada, Puerto Rico). The slides were viewed (blinded) by light microscopy, and the percentage of 100 to 200 cells containing intracellular SRBCs was determined (percentage of U-937 cells with intracellular SRBC).

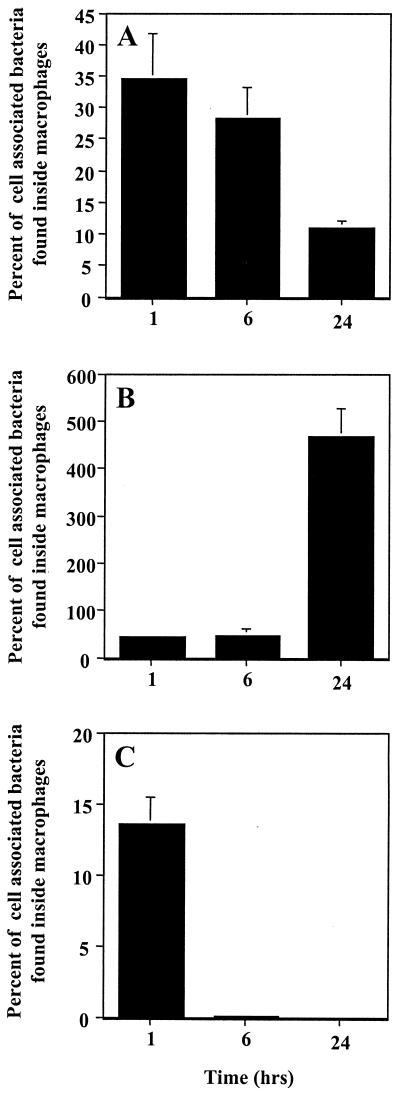

FIG. 6.

Dose response of inhibition of phagocytosis. U-937 macrophages were treated with the dose of H. ducreyi 35000ΔAPC shown for 1 h then allowed to phagocytose opsonized SRBCs for 1 h. The mean and standard error for a typical experiment performed in duplicate are shown; the experiment was performed three times with similar results.

Assay for cytolethal distending toxin activity.

Supernatants of overnight cultures of H. ducreyi and E. coli strain DH5α(pJL300) were assayed for cytolethal distending toxin activity against HeLa cells as previously described (8).

Fractionation of H. ducreyi.

H. ducreyi was sonicated by the method of Carlone et al. (5). Briefly, overnight cultures were diluted 1:5 in Hd broth with 10% fetal bovine serum and incubated at 35°C with shaking for 4 to 5 h. A 20-μl sample of this logarithmic-phase culture was centrifuged at 6,000 × g for 10 min and then resuspended in 2 ml of 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4). A 250-μl volume was set aside (“whole cells”; approximately 5 × 108 CFU/ml), and the remaining suspension was sonicated (3 to 4 15-s bursts on ice) to disrupt the cells. The cell lysate was microcentrifuged for 2 min to remove unlysed cells and debris, and a 250-μl aliquot was set aside (“total-cell lysate”). The remaining lysate was microcentrifuged for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant (1.5 ml; “soluble fraction”) was collected, while the pellet (“membrane fraction”) was suspended in 500 μl of 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4). A 100-μl aliquot of each fraction was added to the phagocytosis assay mixtures as described above. The membrane fraction is thus concentrated threefold relative to the other fractions.

RESULTS

H. ducreyi adheres efficiently to U-937 cells, but few are phagocytosed.

We first performed experiments to investigate the adherence, uptake, and intracellular survival of H. ducreyi in the human macrophage-like cell line, U-937. Overnight (nonhemolytic) cultures of H. ducreyi strain 35000 were added to differentiated U-937 macrophages at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of ∼10 bacteria per macrophage. After 30 min the wells were washed to remove nonadherent bacteria and the total number of cell-associated (adherent and intracellular) bacteria was determined by plate counts. In a parallel experiment, extracellular bacteria were killed with gentamicin and the intracellular bacteria were enumerated. Avirulent E. coli HB101 and virulent S. enterica serovar Typhimurium SL1344 served as controls in this experiment. HB101 was expected to adhere to macrophages and be phagocytosed but not survive intracellularly, while SL1344 should adhere, invade, and multiply intracellularly.

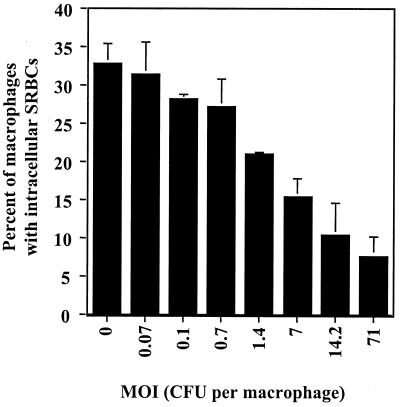

As shown in Fig. 1A, the total number of cell-associated bacteria was approximately 16% for E. coli HB101, 22% for S. enterica SL1344, and 28% for H. ducreyi strain 35000 compared to the total inoculum. Thus, H. ducreyi strain 35000 associated with U-937 cells at a level that equaled or exceeded that of E. coli HB101 and S. enterica SL1344. When the number of intracellular bacteria was determined (expressed as a percentage of the inoculum), it was found that 5.6% ± 1.2% of E. coli HB101, 9.2% ± 1.8% of S. enterica SL1344, and 3.8% ± 0.5% of H. ducreyi strain 35000 were located intracellularly (data not shown). When the number of intracellular bacteria was compared to the number of cell-associated bacteria (Fig. 1B), it was found that similar percentages of the cell-associated E. coli HB101 and S. enterica SL1344 were internalized (35 and 43% of the cell-associated bacteria were intracellular, respectively). However, far fewer H. ducreyi strain 35000 bacteria were found inside U-937 cells with only 13.6% of the cell-associated H. ducreyi located intracellularly (Fig. 1B). Thus, in comparison to S. enterica SL1344 and E. coli HB101, H. ducreyi adhered efficiently to U-937 cells but few bacteria were phagocytosed.

FIG. 1.

Interaction of H. ducreyi, E. coli, and S. enterica serovar Typhimurium with U-937 macrophages. Adherence to (A) or phagocytosis (B) by U-937 macrophages of E. coli HB101, S. enterica SL1344, and H. ducreyi 35000 is shown. Bacteria at an approximate MOI of 10 were centrifuged onto macrophages, and the number of cell-associated or intracellular bacteria was determined as described in Materials and Methods. Cell-associated bacteria are shown as a percentage of the total inoculum, while intracellular bacteria are shown as a percentage of the cell-associated bacteria. The mean and standard error for a typical experiment performed in triplicate are shown; the experiment was performed three times with similar results.

Intracellular H. ducreyi are rapidly killed by U-937 cells.

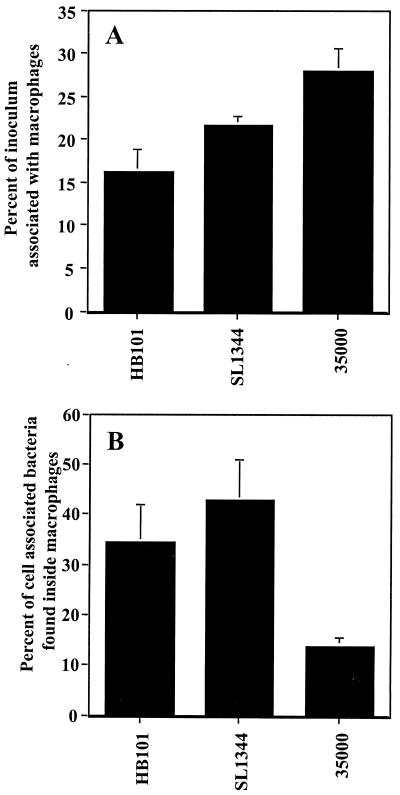

To investigate the fate of the few H. ducreyi that were phagocytosed by U-937 cells, we performed a time course experiment to monitor the survival of intracellular bacteria over a 24-h period. As shown in Fig. 2A, most (∼70%) of the intracellular E. coli HB101 bacteria were killed during the 24-h incubation period. As expected, S. enterica SL1344 multiplied in U-937 cells, consistent with the known virulence capabilities of this organism (Fig. 2B) (16). In comparison, intracellular H. ducreyi strain 35000 were rapidly killed by the U-937 cells (Fig. 2C); after 6 h the number of intracellular bacteria was reduced by 99.8% and no intracellular H. ducreyi bacteria were viable after 24 h. Thus, H. ducreyi, like E. coli, did not replicate or survive in U-937 cells but instead were killed.

FIG. 2.

Intracellular survival of H. ducreyi in U-937 macrophages. The intracellular survival of E. coli HB101 (A), S. enterica SL1344 (B), or H. ducreyi 35000 (C) was monitored over time as described in Materials and Methods. The number of intracellular bacteria as a percentage of the total cell-associated bacteria is shown. The mean and standard error for a typical experiment performed in triplicate are shown; the experiment was performed three times with similar results.

H. ducreyi inhibits phagocytosis by U-937 macrophages.

Our observation that few H. ducreyi bacteria are internalized by U-937 cells suggested that H. ducreyi is able to avoid or inhibit phagocytosis. To test the latter possibility, we developed an assay to measure the phagocytosis of a secondary phagocytosis target (opsonized SRBCs) after exposure of U-937 cells to H. ducreyi. We used this assay because (i) extracellular (nonphagocytosed) SRBCs can be lysed with distilled water, thus simplifying the identification of U-937 containing intracellular SRBCs (23), and (ii) inhibition of phagocytosis can be measured separately from bacterial killing by the U-937 cells. To avoid lysis of the target SRBCs by H. ducreyi hemolysin, a nonhemolytic mutant (35000ΔAPC) derived from 35000 (50) was used in these experiments. Strain 35000ΔAPC did not differ from wild-type strain 35000 in the ability to inhibit phagocytosis (see below). PMA-treated U-937 cells were exposed to cultures of H. ducreyi strain 35000ΔAPC or controls of cytochalasin B (an inhibitor of actin polymerization) or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, solvent for cytochalasin B) and then allowed to phagocytose SRBCs. Extracellular SRBCs were lysed, and the percentage of U-937 cells containing intracellular SRBCs was determined by light microscopy. As shown in Fig. 3, approximately 30% of untreated (medium -only) U-937 cells phagocytosed opsonized SRBCs while only ∼2% of U-937 cells phagocytosed nonopsonized SRBCs (data not shown), indicating that opsonization is required for phagocytosis of SRBCs by U-937 cells. The solvent control, DMSO, had no effect, while cytochalasin B treatment inhibited the phagocytosis of opsonized SRBCs. Treatment of U-937 cells with H. ducreyi strain 35000ΔAPC at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of approximately 70 CFU per macrophage inhibited the phagocytosis of SRBCs to a level similar to that caused by cytochalasin B. This effect was observed with log-phase and stationary-phase cultures grown in broth and, to a lesser extent, with H. ducreyi grown on plates. Treatment of U-937 cells with avirulent E. coli HB101 or avirulent H. influenzae strain Rd had no effect on the phagocytosis of SRBCs (Fig. 3) suggesting that inhibition of phagocytosis was specific to H. ducreyi.

FIG. 3.

Inhibition of phagocytosis by H. ducreyi. Differentiated U-937 macrophages were treated with DMSO, cytochalasin B (cyto B), logarithmic (log), overnight (ON), or plate-grown (plate) cultures of H. ducreyi, or logarithmic cultures of E. coli HB101 (HB101) or H. influenzae strain Rd (Rd) as indicated for 1 h and then exposed to opsonized SRBCs for 1 h. Extracellular SRBCs were lysed, and phagocytosis was determined by light microscopy. The percentage of U-937 cells with intracellular SRBCs is shown. The mean and standard error for a typical experiment performed in triplicate are shown; the experiment was performed at least three times with similar results.

Trypan blue staining revealed that untreated and H. ducreyi 35000ΔAPC-treated U-937 cells did not differ in the percentage of viable cells. More than 98% of the macrophages were viable in both experiments (data not shown), suggesting that inhibition of phagocytosis was not due to macrophage cytotoxicity.

Characterization of the antiphagocytic activity of H. ducreyi.

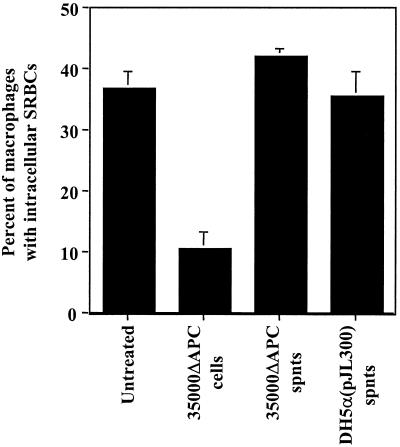

To determine whether the antiphagocytic activity of H. ducreyi was secreted or cell associated, U-937 cells were pretreated with whole cells or supernatants from overnight cultures of H. ducreyi 35000ΔAPC. As shown in Fig. 4, the antiphagocytic activity was associated only with whole cells and not with culture supernatants. Supernatants from E. coli DH5α(pJL300) expressing plasmid-encoded cytolethal distending toxin (44) were also unable to inhibit phagocytosis by U-937 cells (Fig. 4). Both H. ducreyi 35000ΔAPC and E. coli DH5α(pJL300) culture supernatants contained active cytolethal distending toxin as determined by the HeLa cell assay (reference 8 and data not shown). These results suggest that the antiphagocytic activity requires cell contact and that the secreted cytolethal distending toxin, known to act on immune cells (17), is not sufficient to inhibit phagocytosis.

FIG. 4.

Inhibition of phagocytosis by H. ducreyi cells and supernatants. U-937 macrophages were treated with the samples indicated for 1 h and then allowed to phagocytose opsonized SRBCs for an additional 1 h. cells, washed H. ducreyi cells; spnts, culture supernatants. The mean and standard error for a typical experiment performed in duplicate are shown; the experiment was performed three times with similar results.

We hypothesized that the antiphagocytic factor might be secreted by H. ducreyi into cell culture supernatants only after contact with macrophages. To test this hypothesis, we treated U-937 cells with log-phase H. ducreyi strain 35000ΔAPC at a high MOI (300 to 400 CFU per macrophage) for 1 h, collected the cell culture supernatants, centrifuged them, and added untreated macrophages. After an additional 1-h incubation, we determined the phagocytosis of SRBCs. In this experiment, U-937 cells treated with these supernatants did not differ from untreated macrophages in their phagocytic ability (data not shown), indicating that the active antiphagocytic factor is not found in cell culture supernatants after contact of H. ducreyi with target U-937 cells.

To further characterize the antiphagocytic factor produced by H. ducreyi, U-937 cells were treated with live H. ducreyi, cellular fractions of H. ducreyi, or H. ducreyi that had been killed by being heated at 65°C for 1 h. Whole, live cells of H. ducreyi inhibited phagocytosis, but heat-killed bacteria, whole-cell lysates (sonicates), soluble fractions, and membrane preparations of H. ducreyi were unable to inhibit phagocytosis (data not shown). Together, these results suggest that the antiphagocytic activity is associated only with live, intact H. ducreyi cells, although we cannot exclude the possibility that the local concentration of the antiphagocytic factor at the U-937 cell surface may be higher in experiments using whole cells than in experiments using soluble fractions.

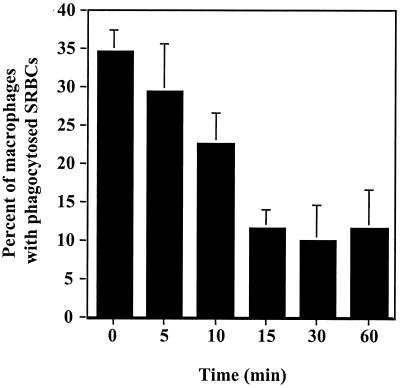

A time course experiment was performed to determine how quickly H. ducreyi inhibits phagocytosis (Fig. 5). U-937 cells were pretreated with H. ducreyi 35000ΔAPC cells for 5 to 60 min, ampicillin and streptomycin were added to kill H. ducreyi, and then the ability to phagocytose opsonized SRBCs was determined. We confirmed that the treatment with ampicillin and streptomycin killed 100% of the inoculum (data not shown). This experiment revealed that a decrease in phagocytosis was detectable after a 10-min pretreatment with a significant reduction (P < 0.05) after 15 min. Longer incubation periods (30 or 60 min) were not more inhibitory than the 15-min period was.

FIG. 5.

Time course of inhibition of phagocytosis. U-937 macrophages were treated with H. ducreyi 35000ΔAPC at an MOI of 50 to 100 CFU per macrophage for the times indicated. Ampicillin and streptomycin were added to kill H. ducreyi, and the macrophages were allowed to phagocytose opsonzed SRBC for 1 h. The mean and standard error for a typical experiment performed in duplicate are shown; the experiment was performed three times with similar results.

Experiments were performed to determine the minimum number of bacteria needed to inhibit phagocytosis. In this experiment, log-phase cultures of H. ducreyi strain 35000ΔAPC were diluted from 1:10 to 1:10,000 and then centrifuged onto the U-937 cells to synchronize contact. Opsonized SRBCs were added after a 1-h incubation, and phagocytosis was measured after an additional 1-h incubation. As shown in Fig. 6, a MOI of approximately 1 CFU per U-937 cell was sufficient to inhibit phagocytosis (P < 0.05); higher MOIs were increasingly inhibitory.

Antiphagocytic activity is a common characteristic of H. ducreyi isolates.

Eight H. ducreyi isolates were tested for their ability to inhibit phagocytosis by U-937 cells. These strains (Table 1) were isolated at different times from various geographical locations and also differed in their antimicrobial susceptibilities, ribotyping patterns, and plasmid content (reference 20 and data not shown). As shown in Fig. 7, all of the strains tested inhibited phagocytosis, suggesting that this potential virulence trait is conserved among H. ducreyi strains. Interestingly, H. ducreyi strain CIP A75 inhibited phagocytosis to a lesser degree than the other strains did.

FIG. 7.

Inhibition of phagocytosis by various strains of H. ducreyi. U-937 macrophages were untreated or treated with the strains indicated (MOI ∼ 100 bacteria per macrophage) for 1 h and then allowed to phagocytose opsonized SRBCs. The mean and standard error for a typical experiment performed in duplicate are shown; the experiment was performed twice with similar results.

DISCUSSION

In vivo, H. ducreyi is found in association with macrophages in naturally acquired chancroid lesions and in the human experimental infection model (2, 25, 26, 31, 42, 43). To understand the mechanisms by which H. ducreyi persists and survives in the presence of these phagocytes, we explored the in vitro interactions of H. ducreyi with the human macrophage-like cell line, U-937. In this study, we found that H. ducreyi strain 35000 adhered to U-937 cells efficiently but resisted phagocytosis. The few H. ducreyi bacteria that were phagocytosed in our experiments were killed by the U-937 cells within 24 h, suggesting that H. ducreyi lacks the ability to survive intracellularly under these conditions. Using a secondary target, opsonized SRBCs, we were able to show that H. ducreyi inhibits Fc-mediated phagocytosis by U-937 macrophages.

We characterized the antiphagocytic activity of H. ducreyi and found that it is associated with whole cells and not with culture supernatants, whole-cell lysates, soluble or membrane fractions, or heat-killed bacteria. Expression of antiphagocytosis was not growth phase dependent and was found in bacteria grown either on plates or in broth. The antiphagocytic activity acts quickly since a 15-min exposure of U-937 cells to H. ducreyi was sufficient to inhibit phagocytosis. Low, physiologically relevant MOIs (∼1 bacterium per macrophage) were sufficient to inhibit phagocytosis, while higher MOIs were more inhibitory. Based on these results, we hypothesize that the antiphagocytic activity of H. ducreyi is active in vivo and enhances the ability of H. ducreyi to avoid clearance by the macrophages found in chancroid lesions. Our finding that H. ducreyi inhibits the phagocytosis of secondary targets (opsonized SRBCs) suggests that antiphagocytic activity may also contribute to the establishment of secondary infections often found in chancroid lesions, because the ability of macrophages to phagocytose other pathogens may be impaired. Antiphagocytosis might also be a mechanism for survival of H. ducreyi in inguinal lymph nodes.

Other organisms can avoid the killing mechanisms of phagocytes by inhibiting attachment to phagocytes or by inhibiting phagocytosis itself. Production of a capsule or slime layer prevents the attachment and uptake of a number of organisms including Streptococcus pyogenes, S. pneumoniae, Cryptococcus neoformans, and Klebsiella pneumoniae (30). S. pyogenes M protein, considered the major virulence factor of group A streptococci, prevents phagocytosis by reducing the opsonization of streptococci by complement (22). Similarly, YadA of Yersinia enterocolitica prevents opsonization by complement and thereby avoids uptake and killing by PMNs (7). These mechanisms are different from the antiphagocytic activity expressed by H. ducreyi, which adhered to U-937 cells and prevented the phagocytosis of a secondary target, opsonized SRBCs. While we cannot exclude the possibility that H. ducreyi avoids opsonization (possibly mediated through DsrA [12]), the antiphagocytic activity described here is distinct since complement was omitted in our experiments.

Other bacteria use toxins to inhibit phagocytosis. For example, the E. coli alpha-hemolysin inhibits leukocyte function, including phagocytosis, at sublytic doses (6), while the YopE and ExoS cytotoxins of Yersinia species and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, respectively, disrupt actin microfilaments, thereby avoiding uptake by macrophages (15, 40). We were unable to detect overt toxicity in our assays since treated macrophages were viable (by trypan blue exclusion) in our assays. The H. ducreyi cytolethal distending toxin is known to act on immune cells, but supernatants containing active secreted cytolethal distending toxin were unable to inhibit phagocytosis in our experiments. Furthermore, whole-cell sonicates, previously shown to contain active cytolethal distending toxin (36), did not inhibit phagocytosis, suggesting that cell-associated cytolethal distending toxin is also not sufficient for antiphagocytosis. However, definitive proof awaits experiments comparing the antiphagocytic activity of wild-type H. ducreyi whole cells to cells of a mutant deficient in cytolethal distending toxin expression. Our experiments also suggest that the cell-associated hemolysin does not play a predominant role in antiphagocytosis since a hemolysin mutant, 35000ΔAPC, retains antiphagocytic activity.

Perhaps the best understood mechanism of antiphagocytosis in macrophages is that used by Yersinia species. The Yersinia YopH protein is a tyrosine phosphatase that is specifically translocated into target cells via a contact-dependent type III secretion system, where it interferes with host cell phosphotyrosine signaling (1, 35). Mutants lacking YopH are unable to inhibit phagocytosis and are avirulent (1, 13, 39). Similar to H. ducreyi, Yersinia species not only prevent their own uptake but also inhibit the uptake of other phagocytosis targets (13). Inhibition of phagocytosis by enteropathogenic E. coli is similar to that of Yersinia spp. in that a type III secretion system is required and dephosphorylation of host proteins occurs (18). However, no tyrosine phosphatase activity is associated with the enteropathogenic E. coli-secreted proteins, suggesting that E. coli uses a different mechanism from Yersinia to alter macrophage protein phosphorylation and thus inhibit phagocytosis (18). BLAST searches of the recently completed H. ducreyi genome failed to identify homologs of a type III secretion system and the known antiphagocytic proteins YopH, YopE, and M protein, suggesting these mechanisms may not exist in H. ducreyi (data not shown). Finally, Helicobacter pylori inhibits phagocytosis via a mechanism that involves a type IV secretion system, although the secreted factor responsible for antiphagocytosis is not yet known (37). Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans contains a gene cluster (tadA-G) involved in adherence, and the TadA protein is similar to a component of type IV secretion systems (24). The tad gene cluster is also present in H. ducreyi, where it plays a role in adherence (E. J. Hansen, personal communication), but the role of these gene products in the antiphagocytic activity of H. ducreyi has not yet been examined.

The work described here complements that of other groups who studied the interactions of H. ducreyi with phagocytes in vitro and in vivo (2, 28, 32). Odumeru et al. demonstrated that virulent H. ducreyi strains resist phagocytosis and killing by PMNs while avirulent strains do not (32). We tested two of their avirulent strains, CIP A75 and CIP A77, in our macrophage phagocytosis assay and found that both strains were antiphagocytic although CIP A75 was less inhibitory than the other strains. Lagergard et al. (28) also studied the interactions of PMNs with H. ducreyi and found that H. ducreyi resists killing by PMNs but that killing could be greatly increased by the addition of human serum containing either complement or anti-H. ducreyi antibodies. However, even in the presence of 70% fresh serum, 10% of the bacteria survived exposure to PMNs, suggesting the presence of a mechanism to avoid phagocytic killing (28). It will be interesting to perform similar experiments using human macrophages to study the effects of normal and immune serum on the phagocytosis of H. ducreyi. Finally, Bauer et al. (2) found that H. ducreyi associates with phagocytes (macrophages and PMNs) in experimental human lesions but remains extracellular. The authors suggest that H. ducreyi resists phagocytic killing in vivo, a hypothesis supported by our in vitro data.

Although determination of the in vivo role of antiphagocytosis awaits further experiments, the following observations support a role for antiphagocytosis in H. ducreyi virulence: (i) all strains tested were antiphagocytic; (ii) inhibition of phagocytosis occurs at low, physiologically relevant MOIs; and (iii) phagocytosis is inhibited shortly after exposure to H. ducreyi. Furthermore, H. ducreyi is found in association with macrophages in vivo, suggesting that a mechanism must exist to avoid killing by these cells. The goal of future studies will be the elucidation of the antiphagocytic mechanism including identification of the gene product(s) involved and the in vivo importance of this potential virulence trait in the animal models of chancroid.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grant AI33522 from NIH to P.A.T. G.E.W. was supported by NIH STD/AIDS Research Training Grant T32 AI07140. The H. ducreyi genome-sequencing project was funded by NIH grant AI45091.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andersson K, Carballeira N, Magnusson K, Persson C, Stendahl O, Wolf-Watz H, Fallman M. YopH of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis interrupts early phosphotyrosine signalling associated with phagocytosis. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:1057–1069. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauer M E, Goheen M P, Townsend C A, Spinola S M. Haemophilus ducreyi associates with phagocytes, collagen, and fibrin and remains extracellular throughout infection of human volunteers. Infect Immun. 2001;69:2549–2557. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.4.2549-2557.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bong C T H, Throm R E, Fortney K R, Katz B P, Hood A F, Elkins C, Spinola S M. DsrA-deficient mutant of Haemophilus ducreyi is impaired in its ability to infect human volunteers. Infect Immun. 2001;69:1488–1491. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.3.1488-1491.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campagnari A A, Wild L M, Griffiths G E, Karalus R J, Wirth M A, Spinola S M. Role of lipooligosaccharides in experimental dermal lesions caused by Haemophilus ducreyi. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2601–2608. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.8.2601-2608.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlone G M, Thomas M L, Rumschlag H S, Sottnek F O. Rapid microprocedure for isolating detergent-insoluble outer membrane proteins from Haemophilus spp. J Clin Microbiol. 1986;24:330–332. doi: 10.1128/jcm.24.3.330-332.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cavalieri S J, Snyder I S. Effect of Escherichia coli alpha-hemolysin on human peripheral leukocyte function in vitro. Infect Immun. 1982;37:966–974. doi: 10.1128/iai.37.3.966-974.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.China B, N'guyen B T, Bruyere M D, Cornelis G R. Role of YadA in resistance of Yersinia enterocolitica to phagocytosis by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1275–1281. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.4.1275-1281.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cope L D, Lumbley S, Latimer J L, Klesney-Tait J, Stevens M K, Johnson L S, Purven M, Munson J R S, Lagergard T, Radolf J D, Hansen E J. A diffusible cytotoxin of Haemophilus ducreyi. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4056–4061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cortes-Bratti X, Chaves-Olarte E, Lagergard T, Thelestam M. The cytolethal distending toxin from the chancroid bacterium Haemophilus ducreyi induces cell-cycle arrest in the G2 phase. J Clin Investig. 1999;103:107–115. doi: 10.1172/JCI3831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dutro S M, Wood G E, Totten P A. Prevalence, antibody response, and protective immunity induced by the Haemophilus ducreyi hemolysin. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3317–3328. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.7.3317-3328.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elkins C. Identification and purification of a conserved heme-regulated hemoglobin-binding outer membrane protein from Haemophilus ducreyi. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1241–1245. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.4.1241-1245.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elkins C, Morrow J K J, Olsen B. Serum resistance in Haemophilus ducreyi requires outer membrane protein DsrA. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1608–1619. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1608-1619.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fallman M, Andersson K, Hakansson S, Mangusson K, Stendahl O, Wolf-Watz H. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis inhibits Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis in J774 cells. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3117–3124. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.3117-3124.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fortney K R, Young R S, Bauer M E, Katz B P, Hood A F, Munson J R S, Spinola S M. Expression of peptidoglycan-associated lipoprotein is required for virulence in the human model of Haemophilus ducreyi infection. Infect Immun. 2000;68:6441–6448. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.11.6441-6448.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frithz-Lindsten E, Du Y, Rosqvist R, Forsberg A. Intracellular targeting of exoenzyme S of Pseudomonas aeruginosa type III-dependent translocation induces phagocytosis resistance, cytotoxicity and disruption of actin filaments. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:1125–1139. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5411905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Furness G. Interaction between Salmonella typhimurium and phagocytic cells in cell culture. J Infect Dis. 1958;103:272–277. doi: 10.1093/infdis/103.3.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gelfanova V, Hansen E J, Spinola S M. Cytolethal distending toxin of Haemophilus ducreyi induces apoptotic death of Jurkat T cells. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6394–6402. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.12.6394-6402.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goosney D L, Celli J, Kenny B, Finlay B B. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli inhibits phagocytosis. Infect Immun. 1999;67:490–495. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.2.490-495.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hammond G W, Lian C J, Wilt J C, Ronald A R. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Haemophilus ducreyi. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1978;13:608–612. doi: 10.1128/aac.13.4.608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haydock A K, Martin D H, Morse S A, Cammarata C, Mertz K J, Totten P A. Molecular characterization of Haemophilus ducreyi strains from Jackson, MS and New Orleans, LA. J Infect Dis. 1999;179:1423–1432. doi: 10.1086/314771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoiseth S K, Stocker B A D. Aromatic-dependent Salmonella typhimurium are non-virulent and effective as live vaccines. Nature. 1981;291:238–239. doi: 10.1038/291238a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horstmann R D, Sievertsen H J, Knobloch J, Fischetti V A. Antiphagocytic activity of streptococcal M protein: selective binding of complement control protein factor H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:1657–1661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.5.1657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hosoya H, Marunouchi T. Differentiation and dedifferentiation of the human monocytic leukemia cell line, U-937. Cell Struct Funct. 1992;17:263–269. doi: 10.1247/csf.17.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kachlany S C, Planet P J, Bhattacharjee M K, Kollia E, DeSalle R, Fine D H, Figurski D H. Nonspecific adherence by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans requires genes widespread in Bacteria and Archaea. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:6169–6176. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.21.6169-6176.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.King R, Choudhri S H, Nasio J, Gough J, Nagelkerke N J D, Plummer F A, Ndinya-Achola J O, Ronald A R. Clinical and in situ cellular responses to Haemophilus ducreyi in the presence or absence of HIV infection. Int J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 1998;9:531–536. doi: 10.1258/0956462981922773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.King R, Gough J, Ronald A, Nasio J, Ndinya-Achola J O, Plummer F, Wilkins J A. An immunohistochemical analysis of naturally occurring chancroid. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:427–430. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.2.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Korth M J, Schneider R A, Moseley S L. An F41–K88-related genetic determinant of bovine septicemic Escherichia coli mediates expression of CS31A fimbriae and adherence to epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2333–2340. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.7.2333-2340.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lagergard T, Frisk A, Purven M, Nilsson L. Serum bactericidal activity and phagocytosis in host defence against Haemophilus ducreyi. Microb Pathog. 1995;18:37–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lagergard T, Purven M, Frisk A. Evidence of Haemophilus ducreyi adherence to and cytotoxin destruction of human epithelial cells. Microb Pathog. 1993;14:417–431. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1993.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mims C A, Dimmeck N J, Nash A, Stephen J. Mims' pathogenesis of infectious disease. 4th ed. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1995. pp. 75–105. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morse S A. Chancroid and Haemophilus ducreyi. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1989;2:137–157. doi: 10.1128/cmr.2.2.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Odumeru J A, Wiseman G A, Ronald A R. Virulence factors of Haemophilus ducreyi. Infect Immun. 1984;43:607–611. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.2.607-611.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palmer K L, Grass S, Munson J R S. Identification of a hemolytic activity elaborated by Haemophilus ducreyi. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3041–3042. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.7.3041-3043.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palmer K L, Thornton A C, Fortney K R, Hood A F, Munson J R S, Spinola S M. Evaluation of an isogenic hemolysin-deficient mutant in the human model of Haemophilus ducreyi infection. J Infect Dis. 1998;178:191–199. doi: 10.1086/515617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Persson C, Nordfelth R, Holmstrom A, Hakansson S, Rosqvist R, Wolf-Watz H. Cell-surface-bound Yersinia translocate the protein tyrosine phosphatase YopH by a polarized mechanism into the target cell. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:135–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18010135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Purven M, Lagergard T. Haemophilus ducreyi, a cytotoxin-producing bacterium. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1156–1162. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.1156-1162.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramarao N, Gray-Owen S D, Backert S, Meyer T F. Helicobacter pylori inhibits phagocytosis by professional phagocytes involving type IV secretion components. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:1389–1404. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roberts M, Stull T L, Smith A L. Comparative virulence of Haemophilus influenzae with a type b or type d capsule. Infect Immun. 1981;32:518–524. doi: 10.1128/iai.32.2.518-524.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosqvist R, Bolin I, Wolf-Watz H. Inhibition of phagocytosis in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis: a virulence plasmid-encoded ability involving the Yob2b protein. Infect Immun. 1988;56:2139–2143. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.8.2139-2143.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosqvist R, Forsberg A, Rimpilainen M, Bergman T, Wolf-Watz H. The cytotoxic protein YopE of Yersinia obstructs the primary host defence. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:657–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sambrook J, Frisch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spinola S M, Orazi A, Arno J N, Fortney K, Kotylo O, Chen C, Campagnari A A, Hood A F. Haemophilus ducreyi elicits a cutaneous infiltrate of CD4 cells during experimental human infection. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:394–402. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.2.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spinola S M, Wild L M, Apicella M A, Gaspari A A, Campagnari A A. Experimental human infection with Haemophilus ducreyi. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:1146–1150. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.5.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stevens M K, Latimer J L, Lumbley S R, Ward C K, Cope L D, Lagergard T, Hansen E J. Characterization of a Haemophilus ducreyi mutant deficient in expression of cytolethal distending toxin. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3900–3908. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.3900-3908.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sundstrom C, Nilsson K. Establishment and characterization of a human histiocytic lymphoma cell line (U-937) Int J Cancer. 1976;17:565–577. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910170504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Totten P A, Handsfield H H, Peters D, Holmes K K, Falkow S. Characterization of ampicillin resistance plasmids from Haemophilus ducreyi. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1982;21:622–627. doi: 10.1128/aac.21.4.622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Totten P A, Lara J C, Norn D V, Stamm W E. Haemophilus ducreyi attaches to and invades cultured human foreskin epithelial cells in vitro. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5632–5640. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.12.5632-5640.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Totten P A, Norn D V, Stamm W E. Characterization of the hemolytic activity of Haemophilus ducreyi. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4409–4416. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4409-4416.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Totten P A, Stamm W E. Clear broth and plate media for culture of Haemophilus ducreyi. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2019–2023. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.8.2019-2023.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wood G E, Dutro S M, Totten P A. Target cell range of Haemophilus ducreyi hemolysin and its involvement in invasion of human epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3740–3749. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.8.3740-3749.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]