Abstract

A promising live attenuated typhoid vaccine candidate strain for mucosal immunization was developed by introducing a deletion in the guaBA locus of pathogenic Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi strain Ty2. The resultant ΔguaBA mutant, serovar Typhi CVD 915, has a gene encoding resistance to arsenite replacing the deleted sequence within guaBA, thereby providing a marker to readily identify the vaccine strain. CVD 915 was compared in in vitro and in vivo assays with wild-type strain Ty2, licensed live oral typhoid vaccine strain Ty21a, or attenuated serovar Typhi vaccine strain CVD 908-htrA (harboring mutations in aroC, aroD, and htrA). CVD 915 was less invasive than CVD 908-htrA in tissue culture and was more crippled in its ability to proliferate after invasion. In mice inoculated intraperitoneally with serovar Typhi and hog gastric mucin (to estimate the relative degree of attenuation), the 50% lethal dose of CVD 915 (7.7 × 107 CFU) was significantly higher than that of wild-type Ty2 (1.4 × 102 CFU) and was only slightly lower than that of Ty21a (1.9 × 108 CFU). Strong serum O and H antibody responses were recorded in mice inoculated intranasally with CVD 915, which were higher than those elicited by Ty21a and similar to those stimulated by CVD 908-htrA. CVD 915 also elicited potent proliferative responses in splenocytes from immunized mice stimulated with serovar Typhi antigens. Used as a live vector, CVD 915(pTETlpp) elicited high titers of serum immunoglobulin G anti-fragment C. These encouraging preclinical data pave the way for phase 1 clinical trials with CVD 915.

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi strain Ty21a pioneered the concept that an attenuated strain could be sufficiently well tolerated and protective to gain licensure as a live oral typhoid vaccine (9, 27, 32, 46, 57). Despite its many positive attributes, Ty21a, which was developed in the early 1970s by chemical mutagenesis of wild-type serovar Typhi strain Ty2 (11), exhibits only modest immunogenicity. Consequently, three or four spaced doses of Ty21a must be administered to confer an adequate level of enduring protection (9, 27, 29, 46, 57).

Attenuated ΔaroC ΔaroD serovar Typhi strain CVD 908 (18) advanced the field by demonstrating that a live oral typhoid vaccine strain could be clinically well tolerated yet highly immunogenic with a single dose (49, 50). However, 50 and 100% of the subjects who ingested, respectively, 107 or 108 CFU of CVD 908 manifested silent vaccinemias on one or more occasions between days 4 and 8 after vaccination (50). Although these vaccinemias were not associated with adverse clinical consequences and were spontaneously cleared (50), it was deemed desirable to seek a further derivative that did not cause vaccinemias. This was accomplished by introducing a deletion in htrA, which encodes a stress protein that functions as a serine protease (6). Chatfield et al. (6) had shown that serovar Typhimurium strains harboring mutations in htrA were attenuated and could protect orally immunized mice from a challenge that was lethal for unimmunized control mice. Indeed, in phase 1 and 2 clinical trials, a single dose of CVD 908-htrA proved to be well tolerated and immunogenic but, unlike CVD 908, was not associated with silent vaccinemias (52, 53). Two other attenuated serovar Typhi live oral vaccine candidates, ΔphoP phoQ strain Ty800 and Δcya Δcrp Δcdt strain X4073 have also yielded promising results in phase 1 clinical trials (15, 51). Nevertheless, despite the encouraging results observed in clinical trials with these candidate serovar Typhi vaccine strains, experience over the years has taught the wisdom of having backup strains ready to enter clinical evaluation if deficiencies or reactogenicity are identified in subsequent phase 2 clinical trials. Moreover, important nonscientific issues such as the status of intellectual property and the anticipated ease of large-scale manufacture of the candidate vaccine also influence decisions about which vaccines are ultimately selected for further development and at what priority (31). Accordingly, based on the attractive balance of attenuation and immunogenicity achieved with Shigella flexneri 2a harboring deletion mutations in the guaBA operon, which interferes with the biosynthesis of guanine nucleotides (3, 37), we constructed CVD 915, a ΔguaBA mutant of serovar Typhi. Herein we report the construction of CVD 915, its phenotypic characterization by in vitro assays and virulence studies in the mouse model, and its ability to induce immune responses when used as a live vector following mucosal immunization.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of CVD 915.

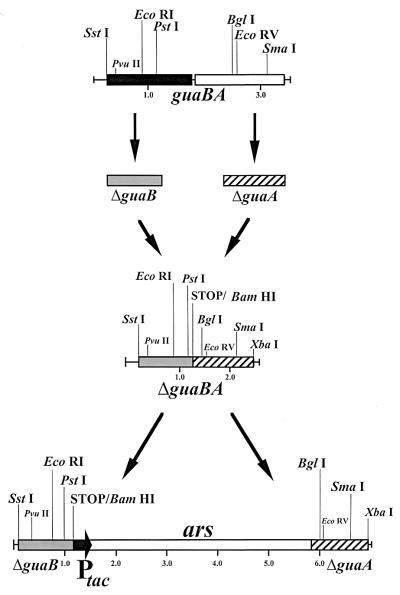

The methods used in the construction of the ΔguaBA allele were analogous to those described in the engineering of ΔguaBA S. flexneri 2a strain CVD 1204 (37). DNA segments that include the 5′ terminus of guaB and the 3′ terminus of guaA were amplified by PCR using serovar Typhi strain Ty2 genomic DNA as the template and then fused in a second PCR, thereby giving rise to the ΔguaBA allele (Fig. 1). In the first PCR, the primers used to amplify the 5′ terminus of the guaBA allele were 5′-CGAGCTCGCGAGCTCGGTAAAGTACCAGTGACCGGAAGCTGGTTGCGT-3′ (primer N127) and 5′-GGGCCCGGGGGATCCTCAACCGACGCCAGTCACGATACGAGTTGTACAGAT-3′ (primer N116) and the primers used to amplify the 3′ terminus of the ΔguaBA allele were 5′-TGAGGATCCCCCGGGCCCGGCTACGCGCAGGTTGAAGTCGTAAACGACAGC-3′ (primer N115) and 5′-GC TCTAGAGCTCTAGAGCTCATTCCCACTCAATGGTAGCTGGCGGCTT- 3′ (primer N126). An in-frame stop codon (TGA) was introduced within the internal primers upstream of two unique restriction sites (ApaI and BamHI) (underlined) that were added to facilitate the introduction of foreign genes into the chromosome in the ΔguaBA allele. The stop signal was introduced to avoid translational fusions of the ΔguaB and ΔguaA products. In addition, these internal primers added sequences that served as the complementary region (shown in bold) with which the 5′ and 3′ PCR products were fused in a second PCR, as described previously (37). Thus, 900 bp of the guaBA operon were not amplified, giving rise to ΔguaBA (Fig. 1). The unique restriction sites (SstI and Xbal) (underlined) were introduced into the extreme primers and used to clone the ΔguaBA allele into the temperature-sensitive pSC101-based (5) suicide plasmid pFM307A cleaved with SstI and XbaI (37), thereby generating pFM307ΔguaBA. In addition, it was considered advantageous to insert a nonantibiotic selection marker (ars, encoding arsenite resistance) into the middle of the ΔguaBA allele to facilitate the exchange of the ΔguaBA for the proficient guaBA allele in Ty2 and to provide a selection marker that will allow the identification of the vaccine strain. The 5.0-kb arsenite resistance (ars) operon of the R factor R773 was obtained as a HindIII fragment from pUM1 (7) (kindly provided by Barry Rosen, Wayne State University, Detroit, Mich.) and cloned under regulation of the Ptac promoter in pKK223-3 (Pharmacia, Piscataway, N.J.). Subsequently, the (blunt-ended) Ptac-ars NaeI-DraI segment was cloned in the ApaI site (blunt ended by T4 polymerase) of the ΔguaBA allele in pFM307ΔguaBA, yielding pJW101. This plasmid was used to introduce the ΔguaBA::Ptac-ars allele into wild-type serovar Typhi strain Ty2 by homologous recombination, as described previously (37, 38), except that 6.0 μM sodium arsenite (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) was present in the medium throughout the procedure.

FIG. 1.

Primers were designed to amplify the 5′-proximal and 3′-distal regions of the guaBA operon. A homologous sequence engineered within the internal primers allowed PCR fusion of these two amplification products, creating a synthetic ΔguaBA locus. Prior to introduction of this inactivated locus into the chromosome of Ty2 by allelic exchange, a synthetic ars operon was inserted into the middle of ΔguaBA. This enabled selection for the desired recombinant strain in which the wild-type guaBA locus was replaced with ΔguaBA::ars within the chromosome of serovar Typhi strain Ty2.

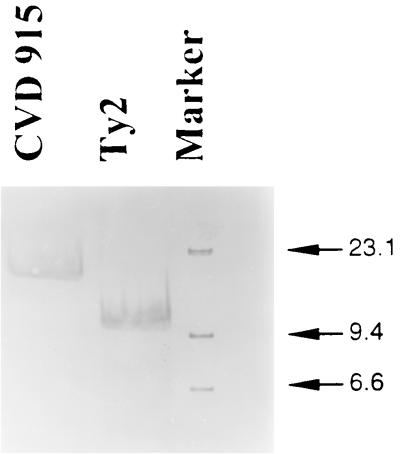

Candidate bacterial clones were grown at 37°C overnight in a grid pattern on Luria agar plates supplemented with 6.0 μM sodium arsenite or in minimal medium. Colonies growing on the arsenite-supplemented Luria agar, but not growing in minimal medium, were then transferred to no. 541 filter paper (Whatman, Maidstone, England), blotted as described by Gicquelais et al. (12), and probed using a γ-32P labeled 40 bp oligonucleotide, 5′-GGGCGGCCTGCGCTCCTGTATGGGTCTGACCGGCTGTGGT-3′, corresponding to a deleted portion of the guaBA wild-type allele (negative probe). Clones that failed to hybridize with the γ-32P-labeled 40-bp oligonucleotide probe were selected. The deletion mutation in the guaBA operon and the Ptac-ars insertion in the ΔguaBA allele were confirmed by Southern blot hybridization with a digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.) ΔguaBA operon, the ars operon, and the guaBA-negative probe described above. The resultant ΔguaBA::Ptac-ars serovar Typhi strain was designated CVD 915.

A plasmid carrying the gene encoding fragment C under the control of the powerful constitutive promoter Plpp was introduced into CVD 915 by electroporation, resulting in CVD 915(pTETlpp) (10), to evaluate the characteristics of the strain when it is used as a mucosally administered live vector.

Complementation of ΔguaBA by construction of a chromosomal guaBA merodiploid.

The wild-type chromosomal guaBA locus from serovar Typhi was recovered using primers N126 and N127 and Ty2 genomic DNA as described above for the construction of CVD 915. The resulting 3,457-bp fragment was again inserted into pFM307A cleaved with SstI and XbaI, generating pFM307guaBA. The pFM307guaBA suicide vector was then introduced into CVD 915 by electroporation, and cointegrates were selected on Ty2 minimal medium (TMM) without guanine supplementation. The composition of TMM is as follows: K2HPO4, 7 g/liter; KH2PO4, 1 g/liter; Mg2SO4, 0.2 g/liter; sodium citrate, 0.5 g/liter; cysteine, 0.1 g/liter; tryptophan, 0.1 g/liter; ammonium ferric citrate, 0.1 g/liter; and glucose, 5 g/liter.

Tissue culture invasion assays.

Gentamicin protection assays were performed as previously described with slight modifications (38, 54). Briefly, semiconfluent Henle 407 cell monolayers in triplicate wells of 24-well plates were infected with either wild-type strain Ty2, ΔguaBA CVD 915, ΔguaBA CVD 915(pTETlpp), or ΔaroC ΔaroD ΔhtrA CVD 908-htrA at a 50:1 ratio for 90 min. Extracellular organisms were then killed by the addition of 100 μg of gentamicin per ml for 30 min; the monolayers were washed (0 h time point) and then incubated with 20 μg of gentamicin per ml. At 0 h and 4 h thereafter, triplicate infected tissue culture monolayers were lysed with sterile water and serial dilutions of that suspension were cultured overnight at 37°C on Luria agar supplemented with guanine [CVD 915 and CVD 915(pTETlpp)] or dihydroxybenzoic acid (CVD 908-htrA).

Assessment of virulence by intraperitoneal inoculation of mice.

Female BALB/c mice (Charles River Breeding Laboratories, Inc., Wilmington, Mass.) aged 6 to 8 weeks (three mice per group, three groups per vaccine strain) were injected intraperitoneally (i.p) with various 10-fold dilutions of the different serovar Typhi strains (grown in the presence of guanine and arsenite, washed, and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline PBS) mixed with 10% (wt/vol) hog gastric mucin in a final volume of 0.5 ml and monitored to detect deaths that occurred within 72 h after inoculation (18, 44). The 50% lethal dose (LD50) for each group of mice was calculated by linear regression analysis.

Immunogenicity in mice.

Strains were grown overnight in Luria broth supplemented with guanine, and vaccine organisms were harvested for immunization of mice. BALB/c mice were immunized intranasally with two 2 × 109 to 4 × 109 CFU doses of either Ty21a, CVD 915, or CVD 908-htrA spaced 28 days apart, as previously described (10, 41–43), and serologic and proliferative responses were measured (see below).

Antigens and mitogens.

Antigens used in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) and/or proliferation assays included serovar Typhi lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Difco), serovar Typhi flagella, whole-cell heat-inactivated phenol-preserved serovar Typhi (Wyeth Laboratories, Marrietta, Pa.) organisms, and fragment C of tetanus toxin (Boehringer Mannheim). Phytohemagglutinin (PHA) and bovine serum albumin (Sigma) were used as controls. The serovar Typhi flagella were purified following a bulk shearing method from the rough serovar Typhi strain Ty2R as previously described (48, 60, 61) and were shown to be free from LPS contamination by using a chromogenic Limulus assay.

Measurement of antibody responses.

Mice were bled from the retro-orbital sinus before immunization (day 0) and every 2 weeks during the immunization schedule (days 14, 28, 42, and 56), and sera were stored at −70°C until tested. Total immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies against serovar Typhi flagella, LPS and fragment C were determined by ELISA as previously described (41). Briefly, 96-well plates were coated with 100 μl of serovar Typhi flagella and LPS preparation (10 μg/ml in carbonate buffer [pH 9]) or fragment C of tetanus toxin (4 μg/ml in PBS) for 3 h at 37°C and blocked overnight with 10% dried milk in PBS. After each incubation the plates were washed with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBST) (Sigma) Sera were subjected for titer determination in eight twofold dilutions (in 10% milk PBST). Antibodies bound to the immobilized antigens were detected using peroxidase-labeled anti-mouse IgG (Boehringer Mannheim) diluted 1/1,000 in 10% dried milk in PBST and substrate solution containing o-phenylenediamine (1 mg/ml) and H2O2 (0.03%) (Sigma) in 0.1 M citrate-phosphate buffer (pH 5). Test and control sera were run in duplicate. Linear regression dose-response curves were plotted for each serum sample, and titers were calculated (through the equation parameters) as the inverse of the serum dilution that produces an optical density of 0.2 above the blank (ELISA units).

Proliferation assays.

Mice were sacrificed 2 months after the primary immunization. Single-cell suspensions were prepared from spleens (five mice/group) and resuspended in RPMI supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES, 50 μg of gentamicin per ml, and 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (HyClone, Logan, Utah). Antigen-specific proliferative responses were measured as previously described (41). Briefly, 2 × 105 splenocytes/well were incubated with serovar Typhi flagella at various final concentrations (0.02 to 2 μg/ml) or whole-cell heat-phenolized inactivated serovar Typhi (2 × 104 to 2 × 106 bacteria/well), all in a final volume of 200 μl. Bovine serum albumin at final concentrations of 0.02 to 2 μg/ml was included as the control antigen. The cells were cultured for 6 days at 37°C under 5% CO2, pulsed with 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine per well, and harvested 18 to 20 h thereafter. PHA was also included in these assays as a positive control for cell proliferation. Cellular proliferation was measured by incorporation of [3H]thymidine. The results are expressed in mean counts per minute (cpm) ± standard error of the mean. We evaluated the presence of specific proliferative responses to bacterial antigens in the different groups by using a range of antigen concentrations, and we found that proliferation increased with the antigen dose. The peak specific responses were generally observed at concentrations of 2 μg of serovar Typhi flagella per ml or 2 × 105 whole-cell inactivated serovar Typhi bacteria/well.

Statistical analysis.

For analysis of tissue culture invasiveness, data were transformed to base 10 logs prior to their analysis. The overall mean and pooled standard deviation were calculated using single-factor (i.e., date) analysis of variance, which accounted for variation among experiments run on different dates. Pairwise comparisons of strains were performed using two-factor analysis of variance (i.e., date × strain with interaction). Statistical significance was evaluated at P = 0.025, to account for multiple comparisons.

Student's test and the Mann-Whitney rank sum test were used for comparison of antibody titers and proliferative responses among different groups at different time points. Calculations were performed using SigmaStat software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill.).

RESULTS

Construction of the attenuated ΔguaBA serovar Typhi mutant strain CVD 915.

By introducing a specific deletion mutation into the guaBA operon (Fig. 1), we obtained a novel candidate serovar Typhi strain. Several ΔguaBA mutants were screened by detecting clones that were able to grow only in arsenite-supplemented agar and failed to hybridize with a γ-32P-labeled 40-bp oligonucleotide probe representing a sequence within the deleted portion of the guaBA wild-type allele. The guaBA allele was amplified by PCR from selected clones yielding a 2.3-kb product versus a 3.2-kb product of the wild-type guaBA (data not shown). The ΔguaBA serovar Typhi clones were able to grow only when minimal medium was supplemented with 10 mg of guanine per liter. After the deletions in the guaBA operon and the Ptac-ars insertion were confirmed. (Fig. 2), one ΔguaBA::Ptac-ars serovar Typhi clone was arbitrarily selected and named CVD 915.

FIG. 2.

Southern blot for Ty2 and ΔguaBA::Ptac-ars derivative strain CVD 915, confirming the expected chromosomal insertion inactivating the guaBA locus. The probe used was a DIG-labeled ΔguaBA operon SstI-XbaI restriction fragment (2.5 kb). Marker refers to a DIG-labeled DNA molecular size marker with a size range of 0.12 to 23.1 kb (Boehringer Mannheim).

Growth in TMM with and without guanine.

Wild-type parent strain Ty2 was observed to grow equally well in TMM either with or without guanine supplementation, whereas CVD 915 grew only in guanine-supplemented TMM. In contrast, the CVD 915(pFM307guaBA) merodiploid, carrying the intact guaBA operon in addition to ΔguaBA, behaved identically to Ty2 in that guanine supplementation was not required for growth.

Invasion and intracellular growth in Henle cells.

Strain CVD 915 was significantly less invasive for Henle 407 cells than was its wild-type parent Ty2 or the attenuated vaccine strain CVD 908-htrA (Table 1). In addition, CVD 915(pTETlpp), a live vector construct that carries a plasmid encoding fragment C of tetanus toxin, was significantly less invasive for Henle 407 cells in culture than was CVD 915 without the foreign antigen plasmid.

TABLE 1.

Invasiveness and intracellular growth of bacterial strains in Henle 407 cells in tissue culture

| Bacterial strain | Relevant phenotype | Intracellular bacterial counts (CFU) per well at following time after Henle 407 cell lysisa:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 h | 4 h | ||

| Serovar Typhi Ty2 | Wild-type parent | 2.5 × 103 (2.1 × 103–3.2 × 103) a | 29.3 × 103 (18.2 × 103–47.8 × 103) e |

| Serovar Typhi CVD 915 | ΔguaBA | 117 (83.2–165.9) b | 89 (70.8–112.2) f |

| Serovar Typhi CVD 915(pTETlpp) | ΔguaBA carrying a plasmid encoding fragment C of tetanus toxin | 35 (25.1–50.1) c | 30 (18.6–48.9) g |

| Serovar Typhi CVD 908-htrA | ΔaroC ΔaroD ΔhtrA | 2.1 × 103 (1.4 × 103–2.9 × 103) d | 8.1 × 103 (6.9 × 103–9.5 × 103) h |

| S. flexneri 2a M4243A | Lacks Shigella invasiveness plasmid | 8 (6.0–10.0) | 8 (6.6–10.0) |

a versus b, P < 0.001; a versus d, P < 0.034; b versus c, P < 0.001; e versus f, P < 0.001; e versus h, P < 0.001; f versus g, P < 0.001.

Comparative safety of candidate vaccine strains.

Estimations of the relative safety and degree of attenuation of the guaBA mutant in a preclinical model were evaluated using the murine hog mucin challenge assay. LD50 were determined and compared with those of the wild-type strain Ty2 and licensed serovar Typhi vaccine strain Ty21a (Table 2) to estimate the degree of attenuation; the LD50 of CVD 915 and Ty21a were found to differ by less than 0.5 log unit (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

LD50 for serovar Typhi strains in mice

| Strain | Genotype | LD50 (CFU)a |

|---|---|---|

| Ty2 | Wild-type parent | 1.4 × 102 |

| CVD 915 | ΔguaBA | 7.7 × 107 |

| Ty21a | Multiple mutationsb | 1.9 × 108 |

Mice (three mice/group, three groups/vaccine strain) were injected i.p. with 0.5-ml doses of serovar Typhi wild-type (1 × 102 to 1 × 104) and mutant derivatives (6 × 106 to 6 × 108) resuspended in 10% hog gastric mucin. LD50 were calculated 72 h after inoculation.

Ty21a has multiple mutations elicited by mutagenesis with nitrosoguanidine. These include mutations in galE, rpoS, and genes involved in expression of the Vi capsular polysaccharide.

Serologic responses.

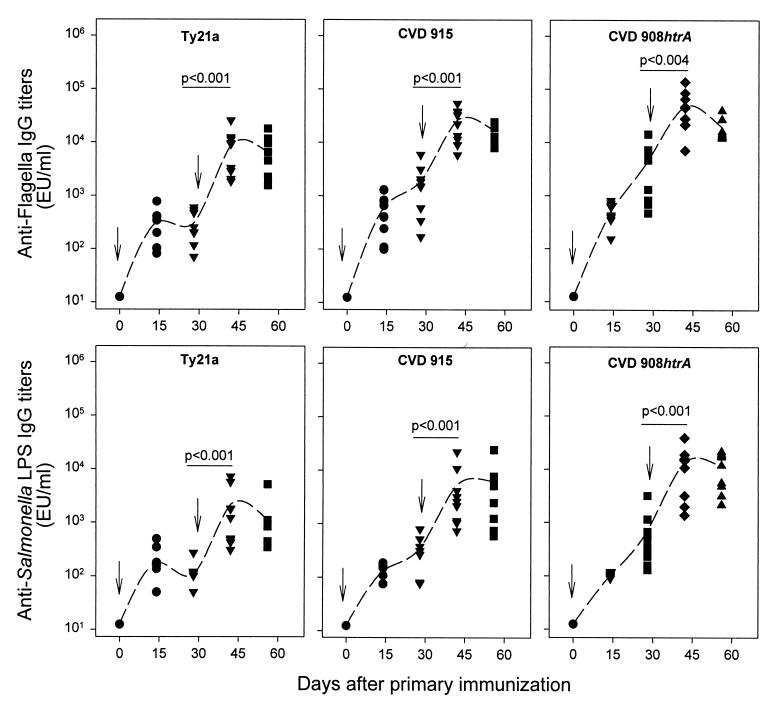

Attenuated serovar Typhi strains Ty21a, CVD 915, and CVD 908-htrA each induced high titers of serum lgG against serovar Typhi flagellar antigen and LPS (Fig. 3). Antibody responses were already evident by 14 days after the first dose and rose further after the booster. No significant differences were observed among the levels of LPS and serovar Typhi flagellar antibodies observed following the booster dose with vaccine strains CVD 915 and CVD 908-htrA. In contrast, both LPS and serovar Typhi flagellar titers elicited by Ty21a were significantly lower than those induced by CVD 915 and CVD 908-htrA (P < 0.02 for anti-LPS and P < 0.008 for anti-flagella antibodies).

FIG. 3.

Serum IgG responses to serovar Typhi flagella (top) and serovar Typhi LPS (bottom). Mice were immunized intranasally on day 0 and boosted on day 28 with 2 × 109 to 4 × 109 CFU of the indicated vaccine strains. Data represent individual titers from 8 to 10 mice in each group. Dotted lines plot the geometric mean titers. Significant increases in antibody titers that occurred after primary and secondary immunization (day 28 versus day 42) are shown.

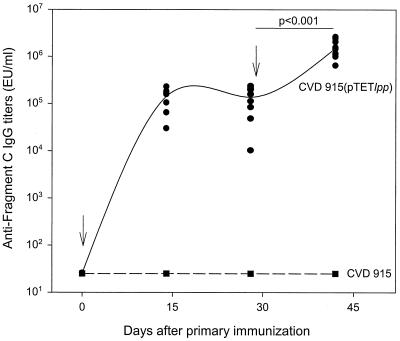

CVD 915 functioned well as a mucosally administered live vector vaccine, as shown by the strong serum IgG anti-tetanus fragment C responses in mice immunized intranasally with CVD 915(pTETlpp) (Fig. 4). High titers of serum IgG anti-fragment C were already evident 14 days after the priming intranasal immunization; the titers rose further following the booster dose (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Serum IgG responses to fragment C of tetanus toxin. Mice were immunized intranasally on days 0 and 28 with 2 × 109 to 4 × 109 CFU of vaccine strains CVD 915 (dashed line) or CVD 915(pTETlpp) (solid line). Data represent individual titers from 10 mice in each group. Significant increases in antibody titer after primary (day 28) and secondary (day 42) immunization are indicated. Anti-fragment C titers measured on day 42 contained more than 2 lU/ml compared with a reference serum previously calibrated by the in vivo toxin neutralization test in mice.

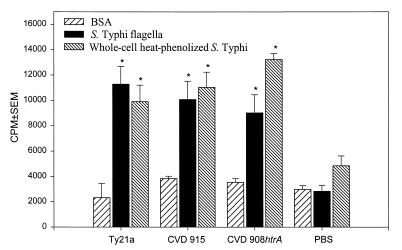

Proliferative responses.

Splenocytes from mice immunized with live serovar Typhi vaccines showed significant increases in proliferative responses following in vitro stimulation with serovar Typhi antigens (i.e., purified flagella and whole-cell heat-inactivated phenal-preserved serovar Typhi) (Fig. 5). Among the groups immunized with the different vaccine strains, there were no significant differences in the magnitude of the proliferative responses to either serovar Typhi flagella or inactivated whole bacteria. All cell populations showed significant increases in cell proliferation in response to PHA stimulation.

FIG. 5.

Proliferative responses to serovar Typhi flagella and LPS. Mice were immunized as described in the legend to Fig. 3 and sacrificed 60 days after primary immunization. Splenocytes were incubated in vitro with bacterial antigens, and proliferative responses were measured. Bars indicate responses at concentrations of 2 μg of serovar Typhi flagella per ml and 2 × 105 bacteria of whole-cell heat-phenolized serovar Typhi per well. The results are expressed as mean cpm and standard error of the mean (SEM). Mice immunized with bacterial strains showed responses to bacterial antigens that were significantly higher than those of the control PBS group (∗, P < 0.05). The results shown are representative of two separate experiments.

DISCUSSION

The heightened impetus in recent years to develop a well-tolerated yet robust and immunogenic single-dose live oral typhoid vaccine stems from the spread throughout South and Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and Northeast Africa of strains of serovar Typhi carrying stable R factor plasmids of incompatibility group H1 encoding resistance to multiple clinically relevant oral antibiotics, including chloramphenicol, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and amoxicillin (2, 4, 14, 35, 36, 40, 45, 56, 58). In many parts of the world, only oral fluoroquinolones such as ciprofloxacin and certain parenteral cephalosporins such as ceftriaxone remain as effective antibiotics; moreover, the expense of ceftriaxone and the need to administer it parenterally make it an untenable option in many communities in less developed countries. Recent reports of the appearance of clones of serovar Typhi exhibiting at least low level resistance to fluoroquinolones further complicate the situation (55, 58). Consequent to the emergence and spread of these multiple antibiotic-resistant serovar Typhi strains, the interest of public health authorities in the use of typhoid vaccines as a possible control measure has been strongly rekindled (20, 21). Viewed from this perspective, oral vaccines hold definite attractions, because of their practicality and freedom from the increasing concern over the consequences of lapses in injection safety (22). Moreover, an oral vaccine that requires only a single dose is more desirable than a vaccine that requires multiple doses.

Live oral typhoid vaccine Ty21a is one of the safest and best tolerated of all licensed vaccines (9, 27, 29, 32, 46, 57). However, the modest immunogenicity of this vaccine, which requires that three or four spaced doses be administered (with an interval of 48 h between doses) to confer credible protection, constitutes an important and practical shortcoming (21, 32). This perceived deficiency has driven efforts to identify alternative attenuated serovar Typhi strains that are as well tolerated as Ty21a but much more immunogenic so that they can be administered as single-dose live oral typhoid vaccines.

Results of clinical trials with other candidate live oral typhoid vaccine strains have revealed that one must strike a delicate balance between attenuation and immunogenicity (15–17, 19, 23, 30, 49–53). The goal is to render the strain sufficiently attenuated to preclude eliciting adverse reactions yet retain sufficient immunogenicity so that a single-dose regimen is feasible. A number of vaccine candidates, such as 541Ty, 543Ty, and Ty445, were adequately tolerated but poorly immunogenic (16, 30). In contrast, several other candidates, such as EX645, CVD 906, and X3927, were markedly more immunogenic that Ty21a but unacceptably reactogenic (19, 49). CVD 908 appeared clinically well tolerated and highly immunogenic in phase 1 clinical trials (49, 50). However, the silent vaccinemias that occurred in recipients of high doses of CVD 908, albeit short-lived and self-limited, were deemed likely to raise problems with regulatory authorities at later points in clinical development.

Presently, based on preliminary results in phase 1 and 2 clinical trials, three attenuated serovar Typhi vaccine strains appear to exhibit an encouraging balance of clinical acceptability and immunogenicity. These strains include CVD 908-htrA (52, 53), Ty800 (which harbors a deletion in the phoPQ regulatory operon that affects intracellular survival) (15), and χ4073 (which harbors mutations in cya, crp, and cdt) (8, 51).

The introduction of mutations in the de novo purine metabolic pathway in Salmonella with the purpose of attenuation was first described by McFarland and Stocker (34). Mutations of purA and purB in Salmonella, which interrupt the biosynthesis of adenine nucleotides, were so crippling that these strains were rendered nonprotective in animals (39) and were poorly immunogenic in humans (30). In contrast, mutations in several of the genes involved in the common purine pathway (i.e., purF, purG, purC, and purHD) or in guaB or guaA were reported to be minimally attenuating in serovars Dublin and Typhimurium (34). Moreover, we have previously shown that the introduction of a defined deletion mutation into the guaBA operon of S. flexneri 2a results in attenuated yet highly immunogenic strains (3, 26, 37).

For the i.p. challenge model in mice with hog gastric mucin, a preclinical test aimed to approximate the degree of residual reactogenicity in humans, we report here that CVD 915 was clearly attenuated compared to its wild-type parent (Table 2). Since CVD 915 has an LD50 only slightly lower than that of Ty21a, it will be interesting to learn in phase 1 clinical trials whether it will indeed be well tolerated.

In humans, attenuated strains of serovar Typhi stimulate mucosal and serum antibodies and a variety of cell-mediated immune responses (15, 23, 47, 48, 53). Some investigators hypothesize that cell-mediated responses are important mediators of the protection conferred by Ty21a and other attenuated serovar Typhi live oral vaccine strains. Nevertheless, evidence argues that serum and mucosal immune responses also contribute to protection and can serve as helpful indicators that a protective overall immune response has been elicited by the live vaccine. For example, with Ty21a, formulations and immunization schedules that gave the highest rates of seroconversion of serum IgG O antibody and that elicited the strongest IgA O antibody-secreting cell responses (detected among peripheral blood mononuclear cells) conferred the best protection during 36 months of surveillance in field trials in Santiago, Chile (23, 28). Since parenteral Vi polysaccharide vaccine (1, 24) and Vi conjugate vaccine (33) confer protection by stimulating serum Vi antibody (25) and since Ty21a neither expresses Vi (11) nor elicits Vi antibodies (13), one may argue that an ideal live oral vaccine will be one that stimulates Vi antibody, in addition to the other immune responses that attenuated strains can elicit and that can confer protection (59).

Because of its exceptional host restriction to humans, there are limitations to studies of immune response to serovar Typhi in mice. Oral immunization typically elicits little or no immune response. In contrast, intranasal immunization is quite effective in stimulating immune responses (10, 42, 43). At the least, the intranasal mouse immunization model allows one to document that a new candidate attenuated strain is capable of stimulating certain types of immune responses to Salmonella antigens or to foreign antigens when the serovar Typhi strain is used as a live vector vaccine (10, 42, 43). For example, we have previously reported that CVD 915 can deliver eukaryotic expression plasmids in the mouse model and elicit immune responses to fragment C encoded by a DNA vaccine (41). Mice immunized intranasally with CVD 915 also elicited CD8+-mediated, major histocompatibility complex-restricted cytotoxic responses to bacterial antigens in cervical lymph nodes and spleen (M. F. Pasetti and M. B. Sztein, unpublished observations). Moreover, by simultaneously comparing in the mouse model several attenuated strains of serovar Typhi for which immunologic data already exist from human clinical trials, it is possible to draw tentative inferences with respect to the relative immunogenicity of the strains. Obviously, only if subsequent clinical studies are carried out in humans can one document the accuracy of these inferences in predicting human immune responses. The serum O and H antibody responses elicited in mice immunized intranasally with two doses of CVD 915 showed a brisk response following the primary dose and a further rise in titer after the booster immunization. The serologic responses stimulated by CVD 915 were significantly higher than those elicited by licensed live oral vaccine strain Ty21a and similar to those stimulated by CVD 908-htrA. It is tempting to speculate that the serological responses correlate inversely with the degree of attenuation in preclinical assays and with the clinical acceptability of the strains in clinical trials.

Although the mouse model and various in vitro assays provide helpful and encouraging preclinical data that assist in guiding vaccine development, only carefully designed and performed clinical trials can ultimately determine the suitability of candidate live oral typhoid vaccines. Accordingly, based on the promising preclinical data reported here with CVD 915, it will be of interest to proceed with a phase 1 clinical trial to learn how well this candidate strikes the balance between lack of reactogenicity and adequate immunogenicity as a live oral typhoid vaccine.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants RO1 AI29471 and RO1 AI40297 (to M.M.L.) and RO1 AI36525 (to M.B.S) and by research contract NO1-AI-45251 (M.M.L., Principal Investigator) from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH, and by grant F05 TW05295 (to M.F.P.) from the Fogarty International Center, NIH. R.A. was supported by an International Fellowship from the Wellcome Trust, London, United Kingdom.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acharya V I, Lowe C U, Thapa R, Gurubacharya V L, Shrestha M B, Cadoz M, Schulz D, Armand J, Bryla D A, Trollfors B, Cramton T, Schneerson R, Robbins J B. Prevention of typhoid fever in Nepal with the Vi capsular polysaccharide of Salmonella typhi. A preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:1101–1104. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198710293171801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anand A C, Kataria V K, Singh W, Chatterjee S K. Epidemic multiresistant enteric fever in eastern India. Lancet. 1990;335:352–352. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90635-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson R, Pasetti M F, Sztein M B, Levine M M, Noriega F R. ΔguaBA attenuated Shigella flexneri 2a strain CVD 1204 as a Shigella vaccine and as a live mucosal delivery system for fragment C of tetanus toxin. Vaccine. 2000;18:2193–2202. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhutta Z A, Naqvi S H, Razzaq R A, Farooqui B J. Multidrug-resistant typhoid in children: presentation and clinical features. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13:832–836. doi: 10.1093/clinids/13.5.832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blomfield I C, Vaughn V, Rest R F, Eisenstein B I. Allelic exchange in Escherichia coli using the Bacillus subtilis sacB gene and a temperature-sensitive pSC101 replicon. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1447–1457. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chatfield S N, Strahan K, Pickard D, Charles I G, Hormaeche C E, Dougan G. Evaluation of Salmonella typhimurium strains harbouring defined mutations in htrA and aroA in the murine salmonellosis model. Microb Pathog. 1992;12:145–151. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(92)90117-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen C M, Mobley H L, Rosen B P. Separate resistances to arsenate and arsenite (antimonate) encoded by the arsenical resistance operon of R factor R773. J Bacteriol. 1985;161:758–763. doi: 10.1128/jb.161.2.758-763.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curtiss R, III, Kelly S M. Salmonella typhimurium deletion mutants lacking adenylate cyclase and cyclic AMP receptor protein are avirulent and immunogenic. Infect Immun. 1987;55:3035–3043. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.12.3035-3043.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferreccio C, Levine M M, Rodriguez H, Contreras R. Comparative efficacy of two, three, or four doses of Ty21a live oral typhoid vaccine in enteric-coated capsules; a field trial in an endemic area. J Infect Dis. 1989;159:766–769. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.4.766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galen J E, Gomez-Duarte O G, Losonsky G A, Halpern J L, Lauderbaugh C S, Kaintuck S, Reymann M K, Levine M M. A murine model of intranasal immunization to assess the immunogenicity of attenuated Salmonella typhi live vector vaccines in stimulating serum antibody responses to expressed foreign antigens. Vaccine. 1997;15:700–708. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(96)00227-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Germanier R, Furer E. Isolation and characterization of gal E mutant Ty21a of Salmonella typhi: a candidate strain for a live oral typhoid vaccine. J Infect Dis. 1975;141:553–558. doi: 10.1093/infdis/131.5.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gicquelais K G, Baldini M M, Martinez J, Maggi L, Martin W C, Prado V, Kaper J B, Levine M M. Practical and economical method for using biotinylated DNA probes with bacterial colony blots to identify diarrhea-causing Escherichia-coli. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2485–2490. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.11.2485-2490.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilman R H, Hornick R B, Woodard W E, DuPont H L, Snyder M J, Levine M M, Libonati J P. Evaluation of a UDP-glucose-4-epimeraseless mutant of Salmonella typhi as a live oral vaccine. J Infect Dis. 1977;136:717–723. doi: 10.1093/infdis/136.6.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta A. Multidrug-resistant typhoid fever in children: epidemiology and therapeutic approach. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1994;13:124–140. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199402000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hohmann E L, Oletta C A, Killeen K P, Miller S I. phoP/phoQ-deleted Salmonella typhi (Ty800) is a safe and immunogenic single-dose typhoid fever vaccine in volunteers. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:1408–1414. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.6.1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hohmann E L, Oletta C A, Miller S L. Evaluation of a phoP/phoQ-deleted, aroA-deleted live oral Salmonella typhi vaccine strain in human volunteers. Vaccine. 1996;14:19–24. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00173-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hone D M, Attridge S R, Forrest B, Morona R, Daniels D, LaBrooy J T, Bartholomeusz R C, Shearman D J, Hackett J. A galE via (Vi antigen-negative) mutant of Salmonella typhi Ty2 retains virulence in humans. Infect Immun. 1988;56:1326–1333. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.5.1326-1333.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hone D M, Harris A M, Chatfield S, Dougan G, Levine M M. Construction of genetically-defined double aro mutants of Salmonella typhi. Vaccine. 1991;9:810–816. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(91)90218-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hone D M, Tacket C, Harris A, Kay B, Losonsky G, Levine M. Evaluation in volunteers of a candidate live oral attenuated S. typhi vector vaccine. J Clin Investig. 1992;90:1–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI115876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ivanoff B, Levine M M. Typhoid fever: continuing challenges from a resilient bacterial foe. Bull Inst Pasteur. 1997;95:129–142. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ivanoff B, Levine M M, Lambert P H. Vaccination against typhoid fever: present status. Bull WHO. 1994;72:957–971. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kane A, Lloyd J, Zaffran M, Simonsen L, Kane M. Transmission of hepatitis B, hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency viruses through unsafe injections in the developing world: model-based regional estimates. Bull WHO. 1999;77:801–807. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kantele A. Antibody-secreting cells in the evaluation of the immunogenicity of an oral vaccine. Vaccine. 1990;8:321–326. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(90)90088-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klugman K, Gilbertson I T, Kornhoff H J, Robbins J B, Schneerson R, Schulz D, Cadoz M, Armand J. Protective activity of Vi polysaccharide vaccine against typhoid fever. Lancet. 1987;ii:1165–1169. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)91316-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klugman K P, Koornhof H J, Robbins J B, Le Cam N N. Immunogenicity, efficacy and serological correlate of protection of Salmonella typhi Vi capsular polysaccharide vaccine three years after immunization. Vaccine. 1996;14:435–438. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00186-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koprowski H, Jr, Levine M M, Anderson R J, Losonsky G, Pizza M, Barry E M. Attenuated Shigella flexneri 2a vaccine strain CVD 1204 expressing colonization factor antigen I and mutant heat-labile enterotoxin of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 2000;68:4884–4892. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.9.4884-4892.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levine M M, Ferreccio C, Black R E, Germanier R Chilean Typhoid Committee. Large-scale field trial of Ty21a live oral typhoid vaccine in enteric-coated capsule formulation. Lancet. 1987;i:1049–1052. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)90480-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levine M M, Ferreccio C, Black R E, Tacket C O, Germanier R. Progress in vaccines against typhoid fever. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11(Suppl 3):S552–S567. doi: 10.1093/clinids/11.supplement_3.s552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levine M M, Ferrecclo C, Cryz S, Ortiz E. Comparison of enteric-coated capsules and liquid formulation of Ty21a typhoid vaccine in randomized controlled field trial. Lancet. 1990;336:891–894. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92266-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levine M M, Herrington D, Murphy J R, Morris J G, Losonsky G, Tall B, Lindberg A, Svenson S, Baqar S, Edwards M F, Stocker B. Safety, infectivity, immunogenicity and in vivo stability of two attenuated auxotrophic mutant strains of Salmonella typhi, 541Ty and 543Ty, as live oral vaccines in man. J Clin Investig. 1987;79:888–902. doi: 10.1172/JCI112899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levine M M, Levine O S. Influence of disease burden, public perception, and other factors on new vaccine development, implementation, and continued use. Lancet. 1997;350:1386–1392. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)03253-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levine M M, Taylor D N, Ferreccio C. Typhoid vaccines come of age. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1989;8:374–381. doi: 10.1097/00006454-198906000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin F Y C, Ho V A, Khiem H B, Trach D D, Bay P V T T C, Kossaczka Z, Bryla D A, Shiloach J, Robbins J B, Schneerson R, Szu S C. The efficacy of a Salmonella typhi Vi conjugate vaccine in two-to-five-year-old children. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1263–1268. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200104263441701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McFarland W C, Stocker B A. Effect of different purine auxotrophic mutations on mouse-virulence of a Vi-positive strain of Salmonella dublin and of two strains of Salmonella typhimurium. Microb Pathog. 1987;3:129–141. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mikhail I A, Haberberger R L, Farid Z, Girgis N I, Woody J N. Antibiotic-multiresistant Salmonella typhi in Egypt. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1989;83:120–120. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(89)90734-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nguyen T A, Ha Ba K, Nguyen T D. Typhoid fever in South Vietnam, 1990–1993. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1993;86:476–478. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Noriega F R, Losonsky G, Lauderbaugh C, Liao F M, Wang M S, Levine M M. Engineered ΔguaB-A, ΔvirG Shigella flexneri 2a strain CVD 1205: construction, safety, immunogenicity and potential efficacy as a mucosal vaccine. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3055–3061. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3055-3061.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Noriega F R, Losonsky G, Wang J Y, Formal S B, Levine M M. Further characterization of ΔaroA, ΔvirG Shigella flexneri 2a strain CVD 1203 as a mucosal Shigella vaccine and as a live vector vaccine for delivering antigens of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1996;64:23–27. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.23-27.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O'Callaghan D, Maskell D, Liew F, Easmon C, Dougan G. Characterization of aromatic- and purine-dependent Salmonella typhimurium: attenuation, persistence, and ability to induce protective immunity in BALB/c mice. Infect Immun. 1988;56:419–423. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.2.419-423.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parry C, Wain J, Chinh N T, Vinh H, Farrar J J. Quinolone-resistant Salmonella typhi in Vietnam. Lancet. 1998;351:1289. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)79356-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pasetti M F, Anderson R J, Noriega F R, Levine M M, Sztein M B. Attenuated ΔguaBA Salmonella typhi vaccine strain CVD 915 as a live vector utilizing prokaryotic or eukaryotic expression systems to deliver foreign antigens and elicit immune responses. Clin Immunol. 1999;92:76–89. doi: 10.1006/clim.1999.4733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pasetti M F, Pickett T E, Levine M M, Sztein M B. A comparison of immunogenicity and in vivo distribution of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi and Typhimurium live vector vaccines delivered by mucosal routes in the murine model. Vaccine. 2000;18:3208–3213. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00142-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pickett T E, Pasetti M F, Galen J E, Sztein M B, Levine M M. In vivo characterization of the murine intranasal model for assessing the immunogenicity of attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi strains as live mucosal vaccines and as live vectors. Infect Immun. 2000;68:205–213. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.205-213.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Powell C J, Jr, DeSett C R, Lowenthal J P, Berman S. The effect of adding iron to mucin on the enhancement of virulence for mice of Salmonella typhi strain TY 2. J Biol Stand. 1980;8:79–85. doi: 10.1016/s0092-1157(80)80049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rowe B, Ward L R, Threlfall E J. Multidrug-resistant Salmonella typhi: a worldwide epidemic. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24(Suppl. 1):S106–S109. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.supplement_1.s106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simanjuntak C, Paleologo F, Punjabi N, Darmowitogo R, Soeprawato, Totosudirjo H, Haryanto P, Suprijanto E, Witham N, Hoffman S L. Oral immunisation against typhoid fever in Indonesia with Ty21a vaccine. Lancet. 1991;338:1055–1059. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91910-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sztein M B, Tanner M K, Polotsky Y, Orenstein J M, Levine M M. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes after oral immunization with attenuated vaccine strains of Salmonella typhi in humans. J Immunol. 1995;155:3987–3993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sztein M B, Wasserman S S, Tacket C O, Edelman R, Hone D, Lindberg A A, Levine M M. Cytokine production patterns and lymphoproliferative responses in volunteers orally immunized with attenuated vaccine strains of Salmonella typhi. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:1508–1517. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.6.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tacket C O, Hone D M, Curtiss R I, Kelly S M, Losonsky G, Guers L, Harris A M, Edelman R, Levine M M. Comparison of the safety and immunogenicity of aroC,aroD and cya,crp Salmonella typhi strains in adult volunteers. Infect Immun. 1992;60:536–541. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.2.536-541.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tacket C O, Hone D M, Losonsky G A, Guers L, Edelman R, Levine M M. Clinical acceptability and immunogenicity of CVD 908 Salmonella typhi vaccine strain. Vaccine. 1992;10:443–446. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(92)90392-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tacket C O, Kelly S M, Schodel F, Losonsky G, Nataro J P, Edelman R, Levine M M, Curtiss R., III Safety and immunogenicity in humans of an attenuated Salmonella typhi vaccine vector strain expressing plasmid-encoded hepatitis B antigens stabilized by the asd balanced lethal system. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3381–3385. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3381-3385.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tacket C O, Sztein M B, Losonsky G A, Wasserman S S, Nataro J P, Edelman R, Pickard D, Dougan G, Chatfield S N, Levine M M. Safety of live oral Salmonella typhi vaccine strains with deletions in htrA and aroC aroD and immune response in humans. Infect Immun. 1997;65:452–456. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.452-456.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tacket C O, Sztein M B, Wasserman S S, Losonsky G, Kotloff K L, Wyant T L, Nataro J P, Edelman R, Perry J, Bedford P, Brown D, Chatfield S, Dougan G, Levine M M. Phase 2 clinical trial of attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi oral live vector vaccine CVD 908-htrA in U.S. volunteers. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1196–1201. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1196-1201.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tartera C, Metcalf E S. Osmolarity and growth phase overlap in regulation of Salmonella typhi adherence to and invasion of human intestinal cells. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3084–3089. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.7.3084-3089.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Threlfall E J, Graham A, Cheasty T, Ward L R, Rowe B. Resistance to ciprofloxacin in pathogenic Enterobacteriaceae in England and Wales in 1996. J Clin Pathol. 1997;50:1027–1028. doi: 10.1136/jcp.50.12.1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vinh H, Wain J, Vo T N, Cao N N, Mai T C, Bethell D, Nguyen T T, Tu S D, Nguyen M D, White N J. Two or three days of ofloxacin treatment for uncomplicated multidrug- resistant typhoid fever in children. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:958–961. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.4.958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wahdan M H, Serie C, Cerisier Y, Sallam S, Germanier R. A controlled field trial of live Salmonella typhi strain Ty21a oral vaccine against typhoid: three year results. J Infect Dis. 1982;145:292–296. doi: 10.1093/infdis/145.3.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wain J, Hoa N T, Chinh N T, Vinh H, Everett M J, Diep T S, Day N P, Solomon T, White N J, Piddock L J, Parry C M. Quinolone-resistant Salmonella typhi in Viet Nam: molecular basis of resistance and clinical response to treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:1404–1410. doi: 10.1086/516128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang J Y, Noriega F R, Galen J E, Barry E, Levine M M. Constitutive expression of the Vi polysaccharide capsular antigen in attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi oral vaccine strain CVD 909. Infect Immun. 2000;68:4647–4652. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.8.4647-4652.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wyant T L, Tanner M K, Sztein M B. Potent immunoregulatory effects of Salmonella typhi flagella on antigenic stimulation of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1338–1346. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1338-1346.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wyant T L, Tanner M K, Sztein M B. Salmonella typhi flagella are potent inducers of proinflammatory cytokine secretion by human monocytes. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3619–3624. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.7.3619-3624.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]