Abstract

Objective

To investigate the influence of age at onset of spinal cord injury on length of stay, inpatient therapy and nursing hours, independence at discharge and risk of institutionalization.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Participants

A total of 250 patients with a newly acquired traumatic or non-traumatic spinal cord injury undergoing primary inpatient rehabilitation in a Swiss spinal cord injury specialized clinic between 2017 and 2019.

Methods

Multiple regression analysis was used to determine if age, in addition to clinical characteristics (co-morbidities, secondary complications and spinal cord injury severity), affects inpatient rehabilitation parameters (length of stay, daily nursing hours and daily therapy hours), independence at discharge (Spinal Cord Independence Measure III) and place of discharge (private residence vs institution).

Results

Chronological age correlated with the number of co-morbidities and secondary complications. Older age was associated with increased daily nursing care and reduced independence at discharge. However, both were also influenced by co-morbidities, secondary complications and severity of spinal cord injury. Length of stay and daily therapy hours were age-independent. Odds for institutionalization after discharge increased significantly, by 1.03-fold per year of age.

Conclusion

Age at onset of spinal cord injury predicted inpatient nursing care, independence at discharge and the risk of institutionalization after primary inpatient rehabilitation. Co-morbidities, secondary complications and severity of spinal cord injury were also important influencing factors.

LAY ABSTRACT

The age at which people have a spinal cord injury is increasing, and there has been a shift from traumatic towards more non-traumatic causes, particularly at an advanced age. The aim of this study was to determine the influence of age at onset of spinal cord injury on the inpatient rehabilitation process and on independence at discharge. A total of 250 patients, with a median age of 57.0 years, undergoing primary inpatient rehabilitation in a Swiss spinal cord injury specialized clinic were included in the study. Older age was associated with a higher number of co-morbidities and more secondary complications. Age significantly predicted daily nursing hours, but not length of stay or daily therapy hours. Moreover, older age was associated with reduced independence at discharge and increased the risk of institutionalization after discharge. In addition to age, co-morbidities, secondary complications and severity of spinal cord injury were important influencing factors.

Key words: spinal cord injury, age of onset, rehabilitation, functional independence, physical therapy modalities, occupational therapy, nursing care

Despite being a low-prevalence condition, the complexity of spinal cord injury (SCI) challenges health systems worldwide (1). Only a handful of high-income countries are able to provide national statistics, hence there are limited data on the global burden of SCI and on rehabilitation outcomes thereafter (1). However, the demographic characteristics of the SCI population have changed continuously over recent decades (2, 3). Although young men still show the highest incidence of SCI (1), the mean age of people with a newly acquired SCI is increasing (3). There has also been a shift in aetiology from traumatic towards more non-traumatic causes, as observed particularly at older ages (1, 4). Moreover, the life expectancy of people with SCI and the proportion of women in the SCI population are increasing (1). Finally, incomplete tetraplegia has become a more frequent SCI diagnosis worldwide (3, 5, 6).

Rehabilitation services, on the other hand, are often targeted at people of working age (7), and older patients are considered to have reduced rehabilitation potential (7, 8). This, consequently, impedes effective and efficient inpatient rehabilitation for the older SCI population (7, 9). There is evidence to suggest that age at onset of SCI affects the extent of the perceived disability and the rehabilitation process after injury (10). However, there is either contradictory or only limited evidence regarding how age influences rehabilitation parameters and outcomes (11, 12). Studies lack appropriate sample sizes or have failed to include a representative sample covering all adult age groups. Furthermore, many studies either focus solely on tetraplegia or paraplegia or are outdated regarding rehabilitation standards (10, 12). This disagreement in the literature and the change in demographic characteristics and aetiology of patients with newly acquired SCI highlight the need for contemporary research on this matter.

This retrospective cohort study aimed to outline current characteristics and to describe key features of the primary rehabilitation stay of people with a newly acquired SCI undergoing inpatient rehabilitation in a Swiss SCI specialized clinic. Multiple regression analysis was used to test the hypothesis that age at SCI onset influences inpatient rehabilitation parameters (length of stay (LOS), daily nursing hours, and daily therapy hours), independence at discharge (Spinal Cord Independence Measure III (SCIM III)) and place of discharge (i.e. private residence or institution).

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Participants and settings

This retrospective cohort study included patients with newly acquired traumatic or non-traumatic SCI completing their primary rehabilitation programme at the Swiss Paraplegic Centre (SPC) in Nottwil, Switzerland between 1 January 2017 and 31 December 2019. Participants were eligible if they were admitted within the first year after injury, ≥ 18 years of age and with complete data available concerning the study endpoint variables. Patients were informed upon admission that their coded health-related data might be used for research purposes. Patients with documented verbal or written rejection of further use of their health-related data were excluded. All data were collected within clinical routine and obtained from the electronic clinic information systems. The results are reported in alignment with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist (see Appendix S1).

Inpatient rehabilitation parameters and outcomes

To explore causal effects of age on rehabilitation parameters and outcome, and to identify the relevant explanatory variables, a directed acyclic graph (DAG) was constructed (see Appendix S2). Collected variables were aligned with the recommendations of the International SCI Core Data Set (13) in order to ensure international comparability. Response variables describing inpatient rehabilitation parameters were: (i) LOS, the combined duration of stay on the intensive care unit of the SPC and inpatient rehabilitation in days; (ii) therapy treatment time, mean hours spent on physical, occupational and sports therapy including active therapy and patient-related administrative work per day; (iii) nursing care, mean hours of nursing care spent on the patient per day. Response variables describing the rehabilitation outcome were: (iv) independence at discharge, assessed using the SCIM III at the time of discharge as per standard protocols. Scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating a higher level of independence (14–16); (v) place of discharge, defined as either private residence or institution.

In addition, the following predictors were collected: (i) age, defined as chronological age at onset of SCI; (ii) SCI severity, using the recommended SCI groups, as defined by the International SCI Core Data Set (i.e. C1–C4 American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale (AIS) A/B/C, C5–C8 AIS A/B/C, Th1–S3 AIS A/B/C and AIS D) (13); (iii) number of co-morbidities, patient charts at admission were screened for predefined co-morbidities in accordance with previous studies in this field (8, 17, 18). Moreover, these co-morbidities needed to be coded in the clinical information systems, finally resulting in the documentation of adiposity, diabetes mellitus, neurological disorders, psychological disorders, cardiovascular diseases, pulmonary diseases and osteoporosis; (iv) number of secondary complications during rehabilitation. Patient charts were screened for predefined secondary complications during inpatient rehabilitation in accordance with the literature (8, 13), including pressure sores, pneumonia, urinary tract infections, other infections, fractures during inpatient rehabilitation, thromboses, heterotrophic ossification, psychological, cardiovascular and pulmonary complications. Notably, only the incidence of each co-morbidity and secondary complication per patient were documented as binary variable. Hence, duration, recurrence and severity were not considered.

In order to present a comprehensive dataset, sociodemographic variables, diagnosis-related variables (International Standards for Neurological Classification of SCI (ISNCSCI) at admission (19, 20)), aetiology and further variables that could potentially influence rehabilitation outcomes, such as spinal surgery, traumatic brain injury, vertebral injury, non-vertebral fractures, organ injury and chemotherapy off site, were also obtained from the chart review (13).

Statistical analysis

Kolmogorov–Smirnov tests were used to test for normal distribution. Results were confirmed through visual inspection of normality plots. Descriptive statistics including median first and third quartile were compiled for all demographic and endpoint variables. To do so, patients were divided into 5 age groups (i.e. 18–34, 35–49, 50–64, 65–74, ≥ 75 years). Age groups, as recommended by the International SCI Core Data Set (13), could not be applied, since only patients ≥ 18 years of age were included in this study and because the retirement age in Switzerland is 65 years. SCI severity, on the other hand, was described using the recommended SCI groups (as described above) (13).

To be able to unveil a potential influence of age, but under consideration of other explanatory variables, as revealed by the DAG (Appendix S2), multiple linear regression was used to determine if age in addition to clinical characteristics (i.e. number of co-morbidities, number of secondary complications and SCI severity) affects inpatient rehabilitation parameters (LOS, daily therapy hours and daily nursing hours) and independence at discharge (SCIM III). To do so, SCI severity was coded as dummy variables, i.e. C1–C4 AIS A/B/C, C5–C8 AIS A/B/C, Th1–S3 AIS A/B/C and AIS D, with the latter acting as reference. In addition, binary logistic regression was used to determine if age, besides the above-mentioned factors, predicts institutionalization of SCI patients after discharge. Furthermore, Spearman rank correlations were used to investigate the relationship between chronological age and the number of predefined co-morbidities and secondary complications. Finally, a Kruskal–Wallis test for independent samples was used to compare clinical characteristics between age groups.

A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using R statistical package (21).

Compliance with ethics standards

This project complies with the regulatory requirements of the Swiss Human Research Act, the Swiss Human Research Ordinance and Good Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ethics approval was granted by the Ethikkommission Nordwest- und Zentralschweiz (EKNZ, Project-ID: 2020-00537, approved on 8 April 2020). The Clinical Trial Unit of the SPC assisted in maintaining regulatory guidelines.

RESULTS

Demographics

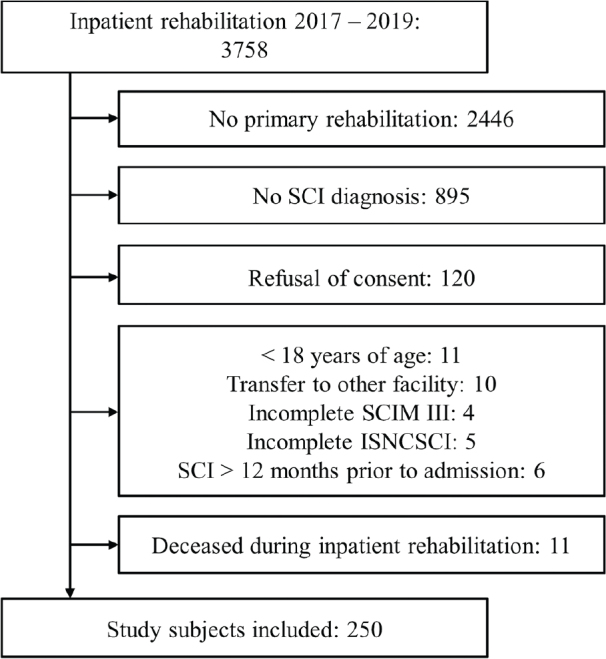

From the 3,758 patients treated at the SPC between 2017 and 2019, 1,312 patients were in their primary rehabilitation, of whom 417 were diagnosed with a newly acquired SCI. A total of 261 patients met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Eleven patients died over the course of their rehabilitation stay and were only analysed descriptively (see Appendix S3).

Fig. 1.

Chart of study population selection in this retrospective cohort study. SCI: spinal cord injury; SCIM III: Spinal Cord Independence Measure III; ISNCSCI: International Standards for Neurological Classification of SCI.

Characteristics and endpoint parameters of the remaining 250 patients overall, and separated per age group, are shown in Tables I and II, respectively.

Table I.

Characteristics of study population

| Characteristics | 18–34 years 1. age group | 35–49 years 2. age group | 50–64 years 3. age group | 65–74 years 4. age group | ≥ 75 years 5. age group | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of individuals, n (%) | 50 (20.0) | 44 (17.6) | 70 (28.0) | 49 (19.6) | 37 (14.8) | 250 (100) |

| Age at onset of SCI, years, median (Q1–Q3) | 26.0 (22.0–29.0) | 43.5 (39.0–45.8) | 58.0 (54.0–61.0) | 70.0 (67.0–72.0) | 79.0 (76.0–81.0) | 57.0 (39.8–70.0) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||

| Male | 35 (70.0) | 32 (72.7) | 55 (78.6) | 28 (57.1) | 21 (56.8) | 171 (68.4) |

| Female | 15 (30.0) | 12 (27.3) | 15 (21.4) | 21 (42.9) | 16 (43.2) | 79 (31.6) |

| Nationality, n (%) | ||||||

| Swiss | 38 (76.0) | 29 (65.9) | 52 (74.3) | 44 (89.8) | 32 (86.5) | 195 (78.0) |

| Other | 12 (24.0) | 15 (34.1) | 18 (25.7) | 5 (10.2) | 5 (13.5) | 55 (22.0) |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||||||

| Single | 45 (90.0) | 12 (27.3) | 8 (11.4) | 6 (12.2) | 3 (8.1) | 74 (29.6) |

| Married/registered partnership | 4 (8.0) | 28 (63.6) | 48 (68.6) | 32 (65.3) | 21 (56.8) | 133 (53.2) |

| Divorced | 1 (2.0) | 3 (6.8) | 11 (15.7) | 8 (16.3) | 3 (8.1) | 26 (10.4) |

| Separated | 0 (0) | 1 (2.3) | 2 (2.9) | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0) | 4 (1.6) |

| Widowed | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.4) | 2 (4.1) | 10 (27.0) | 13 (5.2) |

| SCI aetiology, n (%) | ||||||

| Traumatic | 44 (88.0) | 28 (63.6) | 38 (54.3) | 18 (36.7) | 16 (43.2) | 144 (57.6) |

| Non-traumatic | 6 (12.0) | 16 (36.4) | 32 (45.7) | 31 (63.3) | 21 (56.8) | 106 (42.4) |

| Neurological level upon admission, n (%) | ||||||

| Cervical (C1–C8) | 14 (28.0) | 17 (38.6) | 29 (41.4) | 18 (36.7) | 18 (48.6) | 96 (38.4) |

| Thoracic (Th1–Th12) | 25 (50.0) | 18 (40.9) | 36 (51.4) | 26 (53.1) | 14 (37,8) | 119 (47.6) |

| Lumbar (L1–L5) | 11 (22.0) | 8 (18.2) | 5 (7.1) | 5 (10.2) | 5 (13.5) | 34 (13.6) |

| Sacral (S1–S3) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.4) |

| AIS score upon admission, n (%) | ||||||

| A | 24 (48.0) | 12 (27.3) | 24 (34.3) | 11 (22.4) | 9 (24.3) | 80 (32.0) |

| B | 7 (14.0) | 9 (20.5) | 8 (11.4) | 8 (16.3) | 4 (10.8) | 36 (14.4) |

| C | 7 (14.0) | 6 (13.6) | 11 (15.7) | 10 (20.4) | 7 (18.9) | 41 (16.4) |

| D | 12 (24.0) | 17 (38.6) | 27 (38.6) | 20 (40.8) | 17 (45.9) | 93 (37.2) |

| E | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| SCI groups, n (%) | ||||||

| C1–C4, AIS A/B/C | 4 (8.0) | 1 (2.3) | 9 (12.9) | 5 (10.2) | 4 (10.8) | 23 (9.2) |

| C5–C8, AIS A/B/C | 8 (16.0) | 6 (13.6) | 3 (4.3) | 6 (12.2) | 6 (16.2) | 29 (11.6) |

| Th1–S3, AIS A/B/C | 26 (52.0) | 20 (45.5) | 31 (44.3) | 18 (36.7) | 10 (27.0) | 105 (42.0) |

| AIS D | 12 (24.0) | 17 (38.6) | 27 (38.6) | 20 (40.8) | 17 (45.9) | 93 (37.2) |

| Spinal surgery, n (%) | 7 (14.0) | 4 (9.1) | 10 (14.3) | 5 (10.2) | 3 (8.1) | 29 (11.6) |

| Associated injury, n (%) | ||||||

| Traumatic brain injury | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.3) | 5 (7.1) | 3 (6.1) | 2 (5.4) | 12 (4.8) |

| Vertebral injury | 43 (86.0) | 30 (68.2) | 40 (57.1) | 20 (40.8) | 17 (45.9) | 150 (60.0) |

| Non-vertebral fractures | 12 (24.0) | 9 (20.5) | 20 (28.6) | 4 (8.2) | 5 (13.5) | 50 (20.0) |

| Organ injury | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.8) |

| Co-morbidities, n (%) | ||||||

| Adiposity | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.3) | 5 (7.1) | 2 (4.1) | 1 (2.7) | 10 (4.0) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0) | 8 (11.4) | 9 (18.4) | 11 (29.7) | 29 (11.6) |

| Neurological disorders | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.3) | 3 (4.3) | 3 (6.1) | 3 (8.1) | 11 (4.4) |

| Psychological disorders | 5 (10.0) | 3 (6.8) | 4 (5.7) | 3 (6.1) | 0 (0) | 15 (6.0) |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 6 (12.0) | 8 (18.2) | 32 (45.7) | 32 (65.3) | 33 (89.2) | 111 (44.4) |

| Pulmonary diseases | 0 (0) | 1 (2.3) | 7 (10.0) | 4 (8.2) | 5 (13.5) | 17 (6.8) |

| Osteoporosis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.9) | 4 (8.2) | 0 (0) | 6 (2.4) |

| Secondary complications during rehabilitation, n (%) | ||||||

| Pressure sores | 10 (20.0) | 5 (11.4) | 24 (34.3) | 13 (26.5) | 9 (24.3) | 61 (24.4) |

| Pneumonia | 6 (12.0) | 7 (15.9) | 20 (28.6) | 9 (18.4) | 13 (35.1) | 55 (22.0) |

| Urinary tract infections | 21 (42.0) | 17 (38.6) | 26 (37.1) | 18 (36.7) | 9 (24.3) | 91 (36.4) |

| Other infections | 7 (14.0) | 5 (11.4) | 15 (21.4) | 10 (20.4) | 10 (27.4) | 47 (18.8) |

| Fractures | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Thromboses | 0 (0) | 1 (2.3) | 3 (4.3) | 3 (6.1) | 0 (0) | 7 (2.8) |

| Heterotrophic ossification | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.8) |

| Psychological complications | 8 (16.0) | 3 (6.8) | 8 (11.4) | 4 (8.2) | 1 (2.7) | 24 (9.6) |

| Cardiovascular complications | 2 (4.0) | 2 (4.5) | 12 (17.1) | 15 (30.6) | 11 (29.7) | 42 (16.8) |

| Pulmonary complications | 7 (14.0) | 6 (13.6) | 15 (21.4) | 10 (20.4) | 6 (16.2) | 44 (17.6) |

| Chemotherapy off site, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.9) | 2 (4.1) | 0 (0) | 4 (1.6) |

AIS: American Spinal Injury Association Impairment Scale; Q1: first quartile; Q3: third quartile; SCI: spinal cord injury.

Table II.

Study endpoint variables by age group

| Outcome parameters | 18–34 years 1. age group | 35–49 years 2. age group | 50–64 years 3. age group | 65–74 years 4. age group | ≥ 75 years 5. age group | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length of stay, days, median (Q1–Q3) | 173.5 (121.8–226.3) | 177.5 (158.3–232.0) | 191.0 (159.5–240.5) | 177.0 (129.0–238.0) | 171.0 (133.5–208.0) | 177.5 (140.5–233.0) |

| Days on ICU, days, median (Q1–Q3) | 0 (0–6.0) | 0 (0–3.5) | 0 (0–3.0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–2.0) |

| Therapy treatment time in total, h, median (Q1–Q3) | 319.1 (176.4–466.9) | 359.3 (250.1–508.4) | 411.5 (273.1–544.8) | 307.2 (206.7–495.3) | 275.2 (201.2–275.2) | 348.0 (228.4–511.3) |

| Therapy treatment time per day, h, median (Q1–Q3) | 1.8 (1.5–2.2) | 1.9 (1.7–2.4) | 1.9 (1.6–2.5) | 1.8 (1.6–2.6) | 1.7 (1.3–2.3) | 1.8 (1.5–2.4) |

| Nursing care total, h, median (Q1–Q3) | 248.0 (101.6–413.3) | 192.5 (118.3–378.4) | 384.2 (157.6–637.0) | 346.1 (199.0–567.5) | 441.9 (336.7–728.8) | 316.0 (158.5–545.0) |

| Nursing care per day, h, median (Q1–Q3) | 1.5 (0.9–2.0) | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) | 1.9 (1.1–2.8) | 2.1 (1.3–3.1) | 3.1 (2.2–3.8) | 1.9 (1.0–2.8) |

| SCIM III score, points, median (Q1–Q3) | ||||||

| Upon admission | 22.0 (14.5–31.3) | 27.0 (15.3–47.5) | 23.0 (11.8–45.5) | 18.0 (14.0–29.0) | 16.0 (8.0–27.0) | 21.0 (13.0–34.3) |

| Upon discharge | 75.5 (62.8–91.3) | 76.0 (68.0–85.8) | 63.0 (38.8–78.0) | 64.0 (34.5–74.5) | 31.0 (17.5–60.5) | 68.0 (41.0–81.0) |

| Difference | 46.0 (31.5–59.3) | 41.5 (24.3–54.0) | 30.0 (13.8–41.5) | 29.0 (13.5–48.5) | 20.0 (5.5–29.5) | 33.0 (15.0–50.0) |

| Sum of co-morbidities, median (Q1–Q3) | 0 (0–1.0) | 0 (0–1.0) | 1.0 (0–1.0) | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) | 1.0 (0–1.0) |

| Sum of secondary complications during rehab, median (Q1–Q3) | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) | 1.0 (1.0–2.3) | 1.0 (1.0–2.5) | 2.0 (1.0–2.0) | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) |

| Place of residence upon admission, n (%) | ||||||

| Private residence | 49 (98.0) | 44 (100) | 69 (98.6) | 48 (98.0) | 37 (100) | 247 (98.8) |

| Institution | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0) | 3 (1.2) |

| Place of discharge, n (%) | ||||||

| Private residence | 45 (90.0) | 42 (95.5) | 60 (85.7) | 44 (89.8) | 20 (54.1) | 211 (84.4) |

| Institution | 5 (10.0) | 2 (4.5) | 10 (14.3) | 5 (10.2) | 17 (45.9) | 39 (15.6) |

ICU: intensive care unit; h: hours; Q1: first quartile; Q3: third quartile; SCIM III: Spinal Cord Independence Measure III.

Length of stay

The linear regression model explained 28.6% (adjusted R2) of the variance in LOS (F(6, 243) = 17.6, p < 0.001). Age did not predict LOS (β = 0.176, t = –0.752, p = 0.453). However, LOS was longer with additional secondary complications (β = 16.5, t = 5.95, p < 0.001) and with increasing severity of SCI (C1–C4 AIS A/B/C: β = 79.2, t = 5.59, p < 0.001; C5–C8 AIS A/B/C: β = 62.3, t = 4.93, p < 0.001 and Th1–S3 AIS A/B/C: β = 21.7, t = 2.53, p = 0.012; all vs AIS D, respectively).

Therapy treatment time

Collectively, the predictors of the study analysis model accounted for only 3.6% of the variance in daily therapy hours (F(6, 243) = 2.56, p = 0.020). Additional co-morbidities significantly reduced the amount of therapy per day (β = –0.218, t = –3.16, p = 0.002). Age also played a role, but did not quite reach significance level (β = 0.006, t = 1.92, p = 0.056).

Nursing care

The factors in the study analysis model accounted for 51.3% of the variance in daily nursing hours (F(6, 243) = 44.7, p < 0.001). Age was found to significantly affect daily nursing hours (β = 0.018, t = 5.40, p < 0.001), which were, however, also influenced by the number of co-morbidities (β = 0.237, t = 3.48, p < 0.001) and secondary complications (β = 0.204, t = 5.21, p < 0.001) as well as severity of SCI (C1–C4 AIS A/B/C: β = 1.84, t = 9.17, p < 0.001; C5–C8 AIS A/B/C: β = 1.21, t = 6.77, p < 0.001 and Th1–S3 AIS A/B/C: β = 0.438, t = 3.61, p < 0.001; all vs AIS D, respectively).

Independence at discharge

Regarding independence at discharge, the above-described factors collectively accounted for 49.9% of the variance in SCIM III values at discharge (F(6, 243) = 42.3, p < 0.001). Older age (β = –0.435, t = –5.90, p < 0.001), a greater number of co-morbidities (β = –6.42, t = –4.23, p < 0.001), more secondary complications (β = –4.00, t = –4.57, p < 0.001) and more severe SCI characteristics (C1–C4 AIS A/B/C: β = –32.2, t = –7.22, p < 0.001; C5–C8 AIS A/B/C: β = –30.9, t = –7.75, p < 0.001 and Th1–S3 AIS A/B/C: β = –10.9, t = –4.05, p < 0.001; all vs AIS D, respectively) were associated with reduced independence at discharge.

Place of discharge

Of the 250 patients, 211 (84.4%) were discharged to a private residence and only 39 (15.6%) patients had to be referred to an institution. The odds for institutionalization after discharge changed by 1.03-fold (95% confidence interval (95% CI) [1.01, 1.06]) for each additional year of age (p = 0.022). In addition to age, co-morbidities (OR 1.71 [1.13, 2.62]; p = 0.012) and more severe SCI (i.e. C1–C4 AIS A/B/C vs AIS D, OR 4.00 [1.23, 13.00], p = 0.020) were also found to be significant risk factors for institutionalization.

Age influence on other factors

A strong correlation between age at onset of SCI and the sum of co-morbidities (rSpearman = 0.507, p < 0.001) was found, as confirmed by significant differences between age groups ( χ2(4) = 63.599, p < 0.001), suggesting more co-morbidities in older patients. In addition, a weak association was observed between age at onset of SCI and the sum of complications during the rehabilitation process (rSpearman = 0.189, p = 0.003). However, differences in secondary complications between age groups were not significant ( χ2(4) = 9.389, p = 0.052).

DISCUSSION

This study aimed to describe patient characteristics and key features of the primary rehabilitation stay of people with a newly acquired SCI undergoing inpatient rehabilitation in a Swiss SCI specialized clinic, as well as the influence of age on inpatient rehabilitation parameters (i.e. length of stay, therapy and nursing hours) and the rehabilitation outcome (independence at discharge and place of discharge). The main findings were that chronological age predicted hours of nursing care and independence at discharge, was a significant risk factor for institutionalization, and correlated with the number of co-morbidities and secondary complications. LOS and therapy treatment time, however, were found to be age-independent.

Demographics

Characteristics of the study sample were in accordance with current literature on SCI epidemiology, as older patients were more frequently female, more often had non-traumatic SCI and showed more cervical lesions compared with younger age groups (Table I) (4, 5, 10). There is a general trend towards an increase in mean age at onset of SCI (3); however, with quite some variation between countries, which can be attributed to prevailing medical, geographic and social conditions (1, 3). In the USA, for example, the mean age at onset of SCI has increased from 29 years in 1970 to 43 years in 2018 (6). In comparison, a recent study in Switzerland showed a median age of people with newly acquired SCI of 53.5 years (22). In the current study this was slightly higher, at 57.0 years.

Length of stay

LOS did not vary with age. However, LOS was markedly influenced by the severity of the SCI, whereby more severe SCI characteristics correlated with longer LOS. Secondary complications and co-morbidities are also known to lengthen LOS (23). Here, however, this was true only for secondary complications, but not for co-morbidities. Direct comparisons with other studies remain difficult, as many of them are from the USA where LOS typically is markedly shorter. Even within Europe, LOS varies greatly between different countries, probably because of differences between the various healthcare systems (3). Moreover, studies with mixed populations including para- and tetraplegic patients as well as traumatic and non-traumatic SCI are scarce (4, 10, 24). It is evident, however, that rehabilitation stays have become progressively shorter in the last few years (10, 24).

Therapy treatment time

Age at onset of SCI was not associated with therapy treatment time (although there was a trend). Obviously, there is a lot of unexplained variance remaining that needs to be explained by other factors not included in the current analysis.

A therapy treatment time of 1.8 h per day was in accordance with the results of 2 studies based on the SCIRehab Project (USA). However, the mean LOS for inpatient rehabilitation in these 2 studies was 55 days (25, 26), which differs greatly from the median LOS of 177.5 days observed in this study, and hence also resulting in large differences in total inpatient therapy time. No studies could be found investigating age influences on therapy treatment time or the impact of different treatment times on rehabilitation outcome after SCI.

Nursing care

Nursing care per day was significantly higher the older patients were at SCI onset. Unfortunately, there is only limited evidence to compare this with. In a study with patients from the SCIRehab Project, a mean of 4.03 h of nursing care per week over a mean inpatient rehabilitation stay of 55 days was reported (27); however, no information on how this value varied with age was provided. It is notable that for the analysis presented here, only hours of nursing care spent on the patient were included, whereas in the study of the SCIRehab Project time for patient education and nursing management (e.g. planning of discharge) was also considered. In addition to age at SCI onset, the amount of nursing care per day was strongly influenced by SCI severity, but also by the sum of secondary complications and co-morbidities. When keeping all other factors constant, a patient categorized as C1–C4 AIS A, B or C required an estimate of 1.84 h more nursing care per day than a patient categorized as AIS D.

Independence at discharge

Independence at discharge varied significantly with age at onset of SCI, reducing SCIM III at discharge by ~0.44 points per additional year of age. This is in line with other studies showing greater independence at discharge in younger compared with older patients, although only investigating traumatic SCI (28–30). Younger people seem to show a greater improvement in independence during inpatient rehabilitation (10). Reasons for this could be a better adaptability and higher functional reserve (30). Older people, on the other hand, tend to more frequently have incomplete SCIs, which is thought to benefit functional gains and, eventually, independence at discharge (4, 31). Furlan et al. (32, 33) described similar neurobiological responses to SCI between younger and older individuals, therefore suggesting a similar rehabilitation potential. However, more frequent co-morbidities and secondary complications during inpatient rehabilitation limit functional gains in older adults (4, 31). It is noteworthy that lower independence levels might have already prevailed before onset of SCI. This would partially explain the lower SCIM III scores at discharge compared with younger individuals (Table II). However, patients at older age are also capable of considerable improvements in SCIM III scores (Table II). There are a number of studies suggesting that, for older individuals, the translation of functional gains into increased independence requires individually tailored multidisciplinary rehabilitation programmes and that, compared with younger individuals, older people might benefit even more from these programmes to achieve their full recovery potential (7, 9, 10, 28, 34).

Place of discharge

The vast majority of patients were discharged to home settings (Table II). Yet, the need for institutional placement after discharge was significantly associated with older age, indicating that older patients have higher care needs at discharge. Specifically, the odds for institutionalization after discharge changes by 1.031-fold for each additional year of age. Consistent with the literature, age thus is a significant predictor for institutionalization [7,10].The number of co-morbidities and particularly severe SCI characteristics (i.e. C1–C4 AIS A/B/C vs AIS D) were also found to be significant risk factors for institutionalization. The place of discharge may further be impacted by the patient’s pre-existing housing situation, insurance situation, private financial resources, as well as marital status (35). In addition, a greater acceptability for older patients being discharged into an institution compared with younger patients is being discussed (7). Nonetheless, the current study indicates that individually tailored rehabilitation programmes lead to significant improvements in independence and a low institutionalization rate, therefore possibly reducing the burden for healthcare systems in the long-term. Hence, these findings may help in negotiation with third-party payers, as the inpatient rehabilitation of patients with SCI is very cost-intensive.

Age influence on other factors

Older patients had significantly more co-morbidities at admission than younger individuals. These findings are confirmed by studies in people with traumatic SCI (8, 17, 18). In particular, osteoporosis, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases tend to negatively influence the rehabilitation process (36). The physiological process of ageing may foster the increased incidence of co-morbidities in older adults (37), which, in turn, was found to be an explanatory factor for reduced independence at discharge as well as the higher number of hours spent on nursing care at a greater age. Even treatment decisions, such as, for example, timely scheduling of spinal surgery may be influenced by co-morbidities and the associated medication, therefore relevantly influencing the rehabilitation process (37, 38).

A weak correlation between secondary complications and age at onset of SCI was found. A higher total of secondary complications in older adults is controversial (8, 39). The risk of developing secondary complications is increased in patients over 50 years of age (40). However, the neurological level of injury is a major influencing factor for secondary complications in inpatient rehabilitation. In particular, urinary tract infections, pressure sores and pneumonias seem to be common complications in all age groups. Similar to co-morbidities, the physiological process of ageing seems to favour the occurrence of secondary complications, although to a smaller extent. Consequently, training of healthcare professionals in screening for relevant co-morbidities at admission and prevention of secondary complications, especially in the older SCI population, could reduce their impact on the inpatient rehabilitation process as well as independence at discharge.

Study limitations

This study is limited by its retrospective design. Moreover, no comprehensive summary of all prevalent co-morbidities and secondary complications could be given because the chart review was restricted to a predefined list of each (see Table I). Furthermore, although recommended for the SCI population, the use of the SCIM III assessment is not yet established worldwide, which makes comparisons between studies challenging.

Age-groups, as recommended by the International SCI Core Data Set (13), could not be applied, as only patients ≥ 18 years of age were included and the retirement age of 65 years in Switzerland has a significant impact on the insurance situation of an individual and thus required consideration.

Finally, the amount of therapy was measured by merging occupational, physical, and sport therapy treatment times together, as there are considerable differences in the task area between centres, regions and countries.

CONCLUSION

Age influenced inpatient rehabilitation parameters, even though an individual rehabilitation stay is not explicitly adapted according to the age of a patient. Older age at onset of a SCI was associated with additional nursing hours per day, reduced independence, more co-morbidities and secondary complications, and higher risk of institutionalization after discharge. LOS and daily therapy hours were found to be age-independent. Taking the findings of the current study into consideration within a multidisciplinary case management may facilitate the organization of the primary inpatient rehabilitation process and, consequently, impact on rehabilitation outcomes.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study is based on data retrieved from the electronic clinical information systems of the SPC. The authors thank Wolfram Schwegmann, Medical Controlling, SPC, for his invaluable contribution in the formation of this dataset and Dr Jürgen Pannek, Neurourology, SPC, for his thoughtful input to the manuscript.

Data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO) . International Perspectives on Spinal Cord Injury. 2013. [accessed 2022 Feb 1]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/international-perspectives-on-spinal-cord-injury

- 2.Fekete C, Brach M, Ehrmann C, Post MWM, Stucki G. Cohort profile of the international spinal cord injury community survey implemented in 22 countries. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2020; 101: 2103–2111. DOI: 10.1016/j.apmr.2020.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kang Y, Ding H, Zhou H, Wei Z, Liu L, Pan D, et al. Epidemiology of worldwide spinal cord injury: a literature review. J Neurorestoratology 2018; 6: 1–9. DOI: 10.2147/jn.S143236 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scivoletto G, Miscusi M, Forcato S, Ricciardi L, Serrao M, Bellitti R, et al. The rehabilitation of spinal cord injury patients in Europe. Acta Neurochir Suppl 2017; 124: 203–210. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-39546-3_31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brinkhof MWG, Al-Khodairy A, Eriks-Hoogland I, Fekete C, Hinrichs T, Hund-Georgiadis M, et al. Health conditions in people with spinal cord injury: Contemporary evidence from a population-based community survey in Switzerland. J Rehabil Med 2016; 48: 197–209. DOI: 10.2340/16501977-2039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Center NSCIS . Spinal cord injury facts and figures at a glance: 2019 SCI Data Sheet. 2019. [accessed 2020 Apr 21]. Available from: https://www.nscisc.uab.edu/Public/Facts%20and%20Figures%202019%20-%20Final.pdf

- 7.Khoo TC, FitzGerald A, MacDonald E, Bradley L. Outcomes for older adults in inpatient specialist neurorehabilitation. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2019; 63: 340–343. DOI: 10.1016/j.rehab.2019.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krassioukov AV, Furlan JC, Fehlings MG. Medical co-morbidities, secondary complications, and mortality in elderly with acute spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma 2003; 20: 391–399. DOI: 10.1089/089771503765172345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wirz M, Dietz V. Recovery of sensorimotor function and activities of daily living after cervical spinal cord injury: the influence of age. J Neurotrauma 2015; 32: 194–199. DOI: 10.1089/neu.2014.3335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harnett A, Bateman A, McIntyre A, Parikh R, Middleton J, Arora M, et al. Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation Practices. Spinal cord injury rehabilitation evidence (SCIRE). 2021. [accessed 2021 Jan 20]. Available from: http://scireproject.com/evidence/rehabilitation-evidence/rehabilitation-practices/ [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chamberlain JD, Ronca E, Brinkhof MWG. Estimating the incidence of traumatic spinal cord injuries in Switzerland: using administrative data to identify potential coverage error in a cohort study. Swiss Med Wkly 2017; 147: 1–16. DOI: 10.4414/smw.2017.14430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodakowski J, Skidmore ER, Anderson SJ, Begley A, Jensen MP, Buhule OD, et al. Additive effect of age on disability for individuals with spinal cord injuries. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2014; 95: 1076–1082. DOI: 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.01.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biering-Sørensen F, DeVivo MJ, Charlifue S, Chen Y, New PW, Noonan VK, et al. International Spinal Cord Injury Core Data Set (version 2.0) — including standardization of reporting. Spinal Cord 2017; 55: 759–764. DOI: 10.1038/sc.2017.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ackerman P, Morrison SA, McDowell S, Vazquez L. Using the Spinal Cord Independence Measure III to measure functional recovery in a post-acute spinal cord injury program. Spinal Cord 2010; 48: 380–387. DOI: 10.1038/sc.2009.140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson KD, Acuff ME, Arp BG, Backus D, Chun S, Fisher K, et al. United States (US) multi-center study to assess the validity and reliability of the Spinal Cord Independence Measure (SCIM III). Spinal Cord 2011; 49: 880–885. DOI: 10.1038/sc.2011.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Catz A, Itzkovich M, Agranov E, Ring H, Tamir A. SCIM-spinal cord independence measure: a new disability scale for patients with spinal cord lesions. Spinal Cord 1997; 35: 850–856. DOI: 10.1038/sj.sc.3100504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeVivo MJ, Kartus PL, Rutt RD, Stover SL, Fine PR. The influence of age at time of spinal cord injury on rehabilitation outcome. Arch Neurol 1990; 47: 687–691. DOI: 10.1001/archneur.1990.00530060101026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roth EJ, Lovell L, Heinemann AW, Lee MY, Yarkony GM. The older adult with a spinal cord injury. Paraplegia 1992; 30: 520–526. DOI: 10.1038/sc.1992.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.ASIA, Committee IIS . The 2019 revision of the International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury (ISNCSCI) – what’s new? Spinal Cord 2019; 57: 815–817. DOI: 10.1038/s41393-019-0350-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roberts TT, Leonard GR, Cepela DJ. Classifications in brief: American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Impairment Scale. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2017; 475: 1499–1504. DOI: 10.1007/s11999-016-5133-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.R Core Team . R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria. 2020. [accessed 2022 May 12]. Available from: https://www.r-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fekete C, Gurtner B, Kunz S, Gemperli A, Gmünder HP, Hund-Georgiadis M, et al. Inception cohort of the Swiss Spinal Cord Injury cohort study (SwiSCI): Design, participant characteristics, response rates and non-response RESPONSE. J Rehabil Med 2021; 53. DOI: 10.2340/16501977-2795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gross-Hemmi MH, Pacheco D. People with Spinal Cord Injury in Switzerland. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2017; 96: S116–S119. DOI: 10.1097/phm.0000000000000571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gutenbrunner C, Blumenthal M, Geng V, Egen C. Rehabilitation services provision and payment. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2017; 96: S35–S40. DOI: 10.1097/phm.0000000000000668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Foy T, Perritt G, Thimmaiah D, Heisler L, Offutt JL, Cantoni K, et al. The SCIRehab project: treatment time spent in SCI rehabilitation. Occupational therapy treatment time during inpatient spinal cord injury rehabilitation. J Spinal Cord Med 2011; 34: 162–175. DOI: 10.1179/107902611x12971826988093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor-Schroeder S, LaBarbera J, McDowell S, Zanca JM, Natale A, Mumma S, et al. Physical therapy treatment time during inpatient spinal cord injury rehabilitation. J Spinal Cord Med 2011; 34: 149–161. DOI: 10.1179/107902611x12971826988057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rundquist J, Gassaway J, Bailey J, Lingefelt P, Reyes IA, Thomas J. The SCIRehab project: treatment time spent in SCI rehabilitation. Nursing bedside education and care management time during inpatient spinal cord injury rehabilitation. J Spinal Cord Med 2011; 34: 205–215. DOI: 10.1179/107902611x12971826988255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Furlan JC, Fehlings MG. The impact of age on mortality, impairment, and disability among adults with acute traumatic spinal cord injury. J Neurotrauma 2009; 26: 1707–1717. DOI: 10.1089/neu.2009.0888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gulati A, Yeo CJ, Cooney AD, McLean AN, Fraser MH, Allan DB. Functional outcome and discharge destination in elderly patients with spinal cord injuries. Spinal Cord 2011; 49: 215–218. DOI: 10.1038/sc.2010.82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seel RT, Huang ME, Cifu DX, Kolakowsky-Hayner SA, McKinley WO. Age-related differences in length of stays, hospitalization costs, and outcomes for an injury-matched sample of adults with paraplegia. J Spinal Cord Med 2001; 24: 241–250. DOI: 10.1080/10790268.2001.11753581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kennedy P, Evans MJ, Berry C, Mullin J. Comparative analysis of goal achievement during rehabilitation for older and younger adults with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2003; 41: 44–52. DOI: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Furlan JC. Effects of age on survival and neurological recovery of individuals following acute traumatic spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2022; 60: 81–89. DOI: 10.1038/s41393-021-00719-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Furlan JC, Liu Y, Dietrich WD, Norenberg MD, Fehlings MG. Age as a determinant of inflammatory response and survival of glia and axons after human traumatic spinal cord injury. Exp Neurol 2020; 332: 1–11. DOI: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2020.113401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rapidi C-A, Tederko P, Moslavac S, Popa D, Branco CA, Kiekens C, et al. Evidence-based position paper on physical and rehabilitation medicine (PRM) professional practice for persons with spinal cord injury. The European PRM position (UEMS PRM Section). Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2018; 54: 797–807. DOI: 10.23736/s1973-9087.18.05374-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anzai K, Young J, McCallum J, Miller B, Jongbloed L. Factors influencing discharge location following high lesion spinal cord injury rehabilitation in British Columbia, Canada. Spinal Cord 2006; 44: 11–18. DOI: 10.1038/sj.sc.3101778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ikpeze TC, Mesfin A. Spinal cord injury in the geriatric population: risk factors, treatment options, and long-term management. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil 2017; 8: 115–118. DOI: 10.1177/2151458517696680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pili R, Gaviano L, Pili L, Petretto DR. Ageing, disability, and spinal cord injury: some issues of analysis. Curr Gerontol Geriatr Res 2018: 1–7. DOI: 10.1155/2018/4017858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahn H, Bailey CS, Rivers CS, Noonan VK, Tsai EC, Fourney DR, et al. Effect of older age on treatment decisions and outcomes among patients with traumatic spinal cord injury. CMAJ 2015; 187: 873–880. DOI: 10.1503/cmaj.150085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arul K, Ge L, Ikpeze T, Baldwin A, Mesfin A. Traumatic spinal cord injuries in geriatric population: etiology, management, and complications. J Spine Surg 2019; 5: 38–45. DOI: 10.21037/jss.2019.02.02 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jensen MP, Truitt AR, Schomer KG, Yorkston KM, Baylor C, Molton IR. Frequency and age effects of secondary health conditions in individuals with spinal cord injury: a scoping review. Spinal Cord 2013; 51: 882–892. DOI: 10.1038/sc.2013.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.