Abstract

Despite increasing knowledge on the biology of Helicobacter pylori, little is known about the expression pattern of its genome during infection. While mouse models of infection have been widely used for the screening of protective antigens, the reliability of the mouse model for gene expression analysis has not been assessed. In an attempt to address this question, we have developed a quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) that allowed the detection of minute amounts of mRNA within the gastric mucosa. The expression of four genes, 16S rRNA, ureA (encoding urease A subunit), katA (catalase), and alpA (an adhesin), was monitored during the course of a 6-month infection of mice and in biopsy samples from of 15 infected humans. We found that the selected genes were all expressed within both mouse and human infected mucosae. Moreover, the relative abundance of transcripts was the same (16S rRNA > ureA > katA > alpA), in the two models. Finally, results obtained with the mouse model suggest a negative effect of bacterial burden on the number of transcripts of each gene expressed per CFU (P < 0.05 for 16S rRNA, alpA, and katA). Overall, this study demonstrates that real-time RT-PCR is a powerful tool for the detection and quantification of H. pylori gene expression within the gastric mucosa and strongly indicates that mice experimentally infected with H. pylori provide a valuable model for the analysis of bacterial gene expression during infection.

Helicobacter pylori is a spiral-shaped, microaerophilic, gram-negative microorganism which persistently colonizes the stomach mucosa of 30 to 50% of the human population (9). Since its discovery and isolation in 1983 (25, 35), H. pylori has been identified as the major causative agent of chronic active gastritis and peptic ulcer disease and contributes to the development of intestinal type gastric carcinoma and B-cell mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma (9). Therefore, infection by H. pylori causes a major health problem. Moreover, the rapid emergence of H. pylori strains resistant to two drugs, clarythromycin and metronidazole (1), used to treat H. pylori infection and the fact that antibiotic therapy does not prevent reinfection (5) have led to extensive research on the development of a vaccine against this pathogen.

Many studies of the biology of H. pylori have been carried out during the past decade in order to identify virulence factors associated with colonization of the gastric lumen and responsible for pathogenesis (33). Among these factors are urease (which allows H. pylori to survive in the very acidic conditions of the stomach) (7, 8); multiple adhesins like BabA responsible for binding to Lewisb histo blood group antigen (18) or a lipoprotein AlpA (26); catalase (16, 27); the cytotoxin VacA (3); and H. pylori neutrophil-activating protein (30). In parallel to the identification of virulence factors, mouse models have been widely used to identify protective antigens for inclusion in a vaccine against H. pylori infection, such as urease (10, 13, 14, 21), the cytotoxin VacA (24), the catalase (28), and HspA and HspB (11). In all cases, while a strong protective effect was found with several antigens, complete cure or prevention of infection was rarely seen (32). The lack of sterilizing immunity in these models raised the question of whether H. pylori modulates the expression of its genome in response to disparate environments, thereby evading immune responses to specific antigens (32). Despite the importance of H. pylori-induced diseases and the publication of the complete sequence of the genomes of two strains (2, 33), little is known about the temporal expression of the genes encoding virulence factors either in animal models or during human infection. The only reports available to date concern the effect of growth phase during in vitro culture on the production of a few H. pylori proteins: CagA (20) and penicillin binding proteins (22) (accumulation during latency phase), the cytotoxin VacA, and the product of luxS (4) (accumulation during mid-exponential phase). Despite the significance of these studies, most of the results on growth phase effects were not standardized for the number of bacteria, and thus the increase in the total amount of mRNA or protein may simply be the consequence of an increasing bacterial cells. Moreover, the relevance between a growth phase effect observed on the production of a specific protein during laboratory grown bacteria and bacteria found during the course of infection has not been demonstrated. As the expression of virulence factors in vitro may not accurately reflect expression in the host tissue, the patterns of expression of the genes encoding virulence factors within the gastric mucosa remain to be determined not only in animal models but also in infected human tissues.

To address this issue, an accurate and reproducible technique for the detection of minute amounts of H. pylori mRNA within the gastric mucosa was needed. For this purpose, we developed a quantitative real-time reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) assay that allowed, us to determine the levels of four H. pylori genes within mouse and human gastric mucosae. In this report, we demonstrate that the mouse model is valuable for the prediction of transcript abundance within the gastric mucosa.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strain, media, and growth conditions.

H. pylori X43-2AN, a streptomycin-resistant strain adapted to mice by serial passage, was a gift from H. Kleanthous (Acambis, Cambridge, Mass.). H. pylori was grown overnight on blood agar medium containing an antibiotic mixture. The plates were incubated for 3 days at 37°C under microaerobic conditions. The preculture was used to inoculate one 75-cm2 vented flask (Costar) containing 25 ml of blood agar overlaid with 20 ml of Brucella broth (Difco) and supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (HyClone) plus antibiotics. The flask was kept under microaerobic conditions with constant shaking (100 rpm) for 24 h and was checked for purity and identity (Gram staining; urease and catalase activities). The 24-h bacterial suspension was controlled for motility by contrast phase microscopy before infection of mice. To determine the exact number of CFU per milliliter, viable counts were performed by serial dilutions of bacterial suspension as described previously (14).

Collection of clinical samples.

Clinical samples were obtained from 20 volunteers, 18- to 50 year-old healthy males and females, enrolled in a clinical research trial conducted from June 1999 to June 2000 in the hepato-gastro-enterology department of J.-A. Chayvialle, Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Edouard Herriot Lyon, France. Of the 20 volunteers, 15 were H. pylori infected and 5 were not. Patients who had taken nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, proton pump inhibitors, or antibiotics during the preceding 3 months were excluded from the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all volunteers. The protocol was approved by the French ethics committee, the Comité Consultatif de Protection des Personnes dans la Recherche Biomédicale. H. pylori status of the volunteers was determined by serological Pyloriset Dry test (Orion Diagnostica) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay as pre-endoscopy screening. This was confirmed by four different PCRs performed on total DNA extracted from gastric biopsy samples, using specific primers for the amplification of either H. pylori 16S rRNA, ureA, katA, or alpA and by an in-house enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay on blood samples (data not shown). All endoscopies, performed with a videogastroscope (Olympus series 140), were carried out under local anesthesia. At the time of endoscopy, two biopsy samples were obtained from adjacent areas of the gastric antrum; the samples were immediately stored in RNA-later medium (Ambion) and kept at 4°C until RNA extraction.

Animal model and evaluation of infection by quantitative culture.

Sixty-five 6 to 8-week-old outbred Swiss female mice were purchased from IFFA-CREDO (Lyon, France). During the studies, the cages were covered (using Isocaps), mice were given filtered water and irradiated food, and autoclaved bedding material was used. Mice were infected by gastric gavage with 300 μl of a suspension of H. pylori X47-2AN grown as described above and harvested 24 h after initiation of growth. At each time point (from 1 h to 6 months postinfection), five mice per group were euthanized, and the mucosa of one half stomach was stored in RNA-later medium for total RNA extraction. A group of five uninfected control mice were processed in the same manner to evaluate absence of cross-contamination by H. pylori in different groups. At 1 h and 1 week postinfection, one half stomach from each of the 10 mice was stored in a culture transport medium (Portagerm; Biomerieux) and then homogenized in a sterile Dounce tissue grinder containing 1 ml of Brusella broth. Serial dilutions to 10−3 were prepared, and 100 μl of each dilution was inoculated onto blood agar plates for viable counts as described previously (14).

RNA extraction.

Tissue samples were transferred from RNA-later medium and lysed in tissue grinder containing 1 ml of Trizol LS (Gibco BRL) according to the manufacturer's instructions. RNA quantification was carried out by spectrophotometry, and each sample then aliquoted and frozen at −80°C until required. In each case, quantification and crude quality assessment were done by measuring the A260/A280 ratio and by examination on nondenaturing agarose gels (1%) in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer (pH 7.8) stained with ethidium bromide. The RNA preparation was considered acceptable for further use if the presence of the dominant 16S and 23S rRNA species appeared as a fairly sharp intense band and if the A260/A280 ratio was between 1.8 and 2.1. Contaminating chromosomal DNA was digested with DNase I (Gibco BRL) (1 U/ 1 μg of RNA) for 15 min at room temperature. The DNase I was inactivated by the addition of 1 μl of 25 mM EDTA solution to the reaction mixture and heated for 10 min at 65°C.

Reverse transcription and PCR primers.

First-strand complementary DNA synthesis was performed on 5 μg of DNase I-treated total RNA with random hexamers and Moloney murine leukemia virus RT, using a ProSTAR First Strand RT-PCR kit (Stratagene). Complementary DNA PCR primers for 16S rRNA (16SA), ureA (HP73), katA (HP875), and alpA (HP912) were designed using Prime software contained in the Genetics Computer Group (GCG) package in order to match the sequences found in both TIGR and ASTRA databases (http://www.tigr.org/tdb/mdb/hpdb/hpdb.html and http://scriabin.astrazeneca-boston.com/hpylori). Mouse and human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene (G3PDH)-specific primers were obtained using Prime software from a 1,228-bp mRNA sequence (GenBank accession number M32599) and a 1,272-bp mRNA sequence (EMBL accession number X01677), respectively. Amplification of the G3PDH gene on cDNA from mouse or human mRNA was used as a control of total RNA extraction and for standardization of results of target gene transcriptional activity. Primers were purchased from MWG-Biotech, and the corresponding sequences are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Primers used to amplify the internal fragments of the target genes

| Gene | Forward primera | Antisense primera | PCR product (nucleotides) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16S rRNA (16SA) | 5′-GGAGGATGAAGGTTTTAGGATTG-3′ | 5′-TCGTTTAGGGCGTGGACT-3′ | 390 |

| ureA (TIGR 73) | 5′-AAACGCAAAGAAAAAGGC-3′ | 5′-CCATCCATCACATCATCC-3′ | 160 |

| katA (TIGR 875) | 5′-AGAGGTTTTGCGATGAAGT-3′ | 5′-CGTTTTTGAGTGTGGATGAA-3′ | 120 |

| alpA (TIGR 912) | 5′-ACGCTTTCTCCCAATACC-3′ | 5′-AACACATTCCCCGCATTC-3′ | 304 |

| G3PDH (mouse) | 5′-ACTCCCACTCTTCCACCTTC-3′ | 5′-TCTTGCTCAGTGTCCTTGC-3′ | 185 |

| G3PDH (human) | 5′-TGAGAAGTATGACAACAGCC-3′ | 5′-TGAGTCCTTCCACGATACC-3′ | 113 |

Coordinates are available upon request.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR assay.

The real-time RT-PCR assay used the double-stranded DNA-specific dye SYBR Green I (17). PCR was performed using a LightCycler (LC) (36), which is a combination microvolume fluorimeter and rapid thermocycler (Roche Diagnostic). To amplify the cDNA, 2 μl of reverse-transcribed cDNA was subjected to PCR amplification in 20 μl containing 0.5 μM each primer (see above), 3 to 4 mM MgCl2, and 2 μl of ready-to-use LightCycler DNA Master SYBR Green I (10 ×, containing Taq DNA polymerase, reaction buffer, deoxynucleoside triphosphate mix with dUTP instead of dTTP, SYBR Green I dye, and 10 mM MgCl2; Roche Diagnostics). For hot-start PCR, TaqStart antibody (0.16 μl/sample; Clontech) was added before the addition of primers and template cDNA. The reactions were cycled in the LC using the following parameters: 1 cycle of Taq antibody denaturation at 94°C for 90 s; then 45 cycles (temperature transition of 20°C/s) of 94°C for 1 s, 50 to 65°C for 15 s (50°C for ureA, 55°C for katA, 63°C for 16S rRNA, and 65°C for alpA), followed by 72°C for 20 s.

Detection and quantification.

Quantitative analysis was performed using the LC software (Roche Diagnostics). The generation of quantitative data was based on different PCR kinetics of samples with different levels of target gene expression. We used a relative quantification in which the expression levels of H. pylori target genes were compared to the data from a standard curve which was generated by amplifying serial dilutions of a known quantity of amplicons: for each primer set, PCR was performed in parallel reactions using different amount of H. pylori strain X47-2AN chromosomal DNA. Genomic DNA was extracted from 24-h-grown bacteria in biphasic media using a QIA Amp DNA mini kit (Qiagen) and quantified using a PicoGreen double-stranded DNA quantification kit (Molecular Probes). The amount of chromosome equivalent per microliter was calculated considering the length of the H. pylori chromosome, 1.67 Mb (33), and assuming two copies per genome for DNA encoding 16S rRNA gene and one copy per genome for the three other genes. Quantification data were analyzed using the LC analysis software. In this analysis, the background fluorescence is removed by setting manually a noise band. The log-linear portion of the standard's amplification curve is identified, and the crossing point is the intersection of the best-fit line through the log-linear region and the noise band. The standard curve is the plot of the crossing point versus the log copy numbers (Fig. 1). The LC quantification software determines the unknown concentration by interpolating the noise band intercept of an unknown sample against the standard curve of known concentrations (36). As shown in Fig. 1, the quantitative data were calculated from the kinetic curve of the PCR. For this approach, the identity and specificity of the PCR product were confirmed by melting curve analysis, which is part of the LC analysis program. The specific melting point of the PCR product was correlated with the molecular weight as determined by agarose gel electrophoresis. The melting protocol consisted of heating the samples to 96°C, followed by cooling to 50°C and slowly heating at 0.1°C/s to 97°C while monitoring fluorescence.

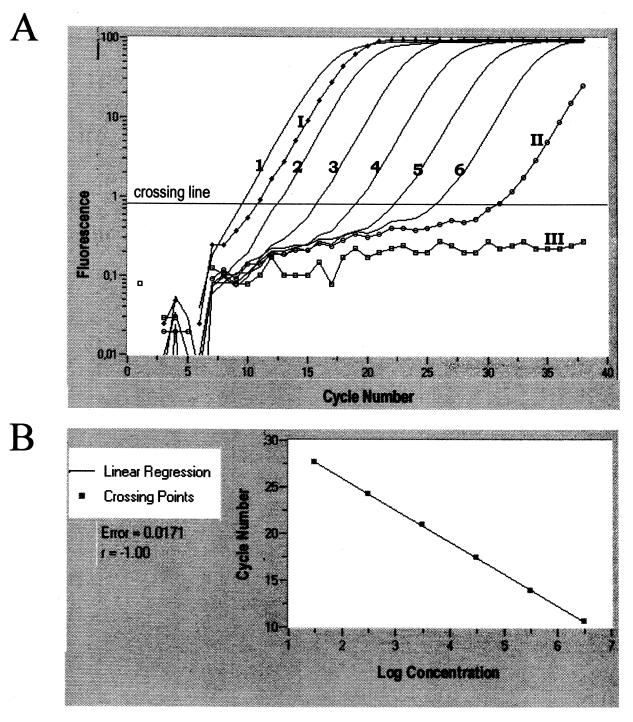

FIG. 1.

Quantitative real-time PCR of alpA expression. Six reactions, each initiated with a different number of template molecules (3 × 106 to 30 copies/sample), were incubated with primers specific for alpA in the amplifications reactions. Standard 10-fold dilution series are indicated (curves numbered from 1 to 6). One infected mouse stomach sample with an unknown amount of alpA transcripts is shown (curve I). Two negative controls obtained by introducing water instead of DNA (curve II) or by omitting the reverse transcription step on DNaseI-treated total RNA corresponding to sample I (curve III) are also indicated (A). The standard curve is the plot of the crossing point, intersection of the best-fit line through the log-linear region and the noise band, versus the log copy numbers. The parameters of the linear regression (error and regression coefficient r) are indicated (B).

The quantification of each gene expression was performed on 70 ng of total RNA preparations. The corresponding RNA samples not previously subjected to reverse transcription were also amplified to measure the amount of contaminating chromosomal DNA. For all genes tested, no contamination by genomic DNA was detectable after DNase I treatment of RNA, indicating specific detection of H. pylori cDNA (not shown). For the determination of H. pylori gene expression in mouse or human stomach, the results were standardized on G3PDH expression.

Statistics.

The data corresponding to gene expression were found to be normally distributed according to Shapiro-Wilks test, indicating that parametric-statistical analysis can be used. Comparison of the mean number copies of transcripts of each gene analyzed (expressed per CFU) between 1 h and 1 week postinoculation was performed with Student's t test. The relation between the level of expression corresponding to each studied gene and the time course of infection was evaluated by a simple linear regression: significance of the model was assessed using an analysis of variance of the regression. Statistical significance was set at a P value of less than 0.05. Error bars in graphs represent standard errors.

RESULTS

Determination of H. pylori gene expression using real-time RT-PCR.

To measure the transcripts level for H. pylori genes, we developed a quantitative RT-PCR assay. We first determined the sensitivity of the quantitative PCR assay for the detection of the four selected H. pylori genes (16S rRNA, ureA, alpA, and katA) by amplifying serial dilutions of genomic DNA from our reference H. pylori strain. Figure 1A shows a representative experiment obtained for the quantification of alpA expression. The corresponding calibration curve (Fig. 1B) was obtained by plotting the initial number of target molecules in the standard series against the corresponding crossing point as described in Materials and Methods. For alpA (Fig. 1) and the three other genes tested (data not shown), the correlation coefficient was >0.99, indicating that under the assay conditions, there was a precise log-linear relation in the range between 10 and 106 input DNA molecules. Data obtained on human or mice gastric samples demonstrated that all reverse-transcribed samples with detectable gene-specific cDNA gave amplification within this linear range (a representative result is shown in Fig. 1A, curve I). Moreover, samples that had not been reverse transcribed showed no detectable amplification (Fig. 1A, curve III), indicating the absence of detection of contaminating DNA. Overall, These results demonstrated the accuracy and reproducibility of this technique over a wide linear range.

Quantification of H. pylori target gene expression in mice over a period of 6 months.

To analyze how H. pylori modulates the expression of the target genes in vivo, we used a mouse model of infection with the mouse-adapted strain X47-2AN (21). The efficiency of cDNA synthesis and the reproducibility of RNA input amounts were assessed in each experimental setup by analyzing an aliquot of each target sample by quantitative PCR for G3PDH mRNA expression. For analysis, the quantitative amounts of each of the four target gene transcripts were standardized on G3PDH expression (Fig. 2). H. pylori expressed the four genes studied in the stomach of mice as early as 1 h post-inoculation, and expression was still detected 6 months postinoculation. These data indicate that bacteria remained in an active expression state for 6 months and that colonization of the stomach may have not been suppressed by the host's immune response. This experiment showed that while the four genes were all expressed in the mice stomach, the amounts of the transcripts were not equivalent: at 3 weeks postinfection, the levels of 16S rRNA transcripts (mean, 2.82 × 108 copies/half stomach [Fig. 2A]) were found to be higher than those of ureA transcripts (mean, 4.28 × 106 copies/half stomach [Fig. 2B]), of katA transcripts (mean, 4.55 × 105 copies/half stomach [Fig. 2C]), and of alpA transcripts (mean, 3.15 × 104 copies/half stomach [Fig. 2D]).

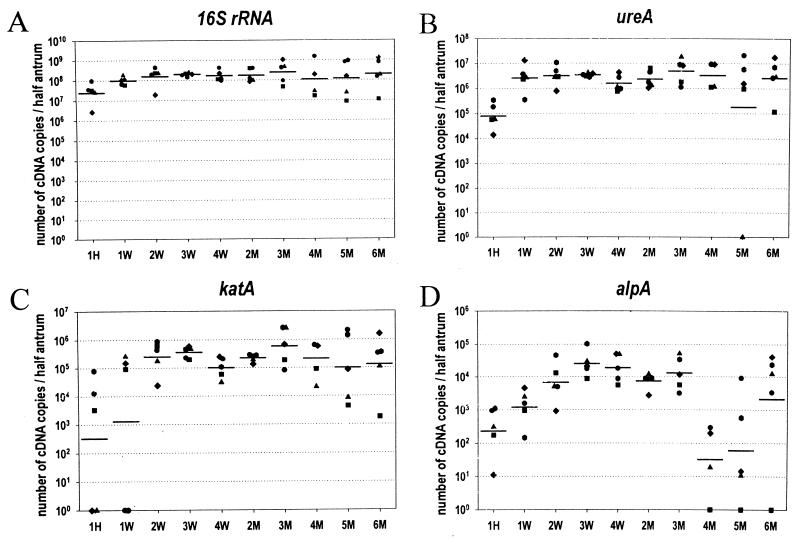

FIG. 2.

Levels of H. pylori gene mRNA during a 6-month course of infection in mice. The numbers of cDNA copies corresponding to 16S rRNA (A), ureA (B), katA (C), and alpA (D) genes were determined in stomachs from Swiss mice over time. Fifty mice that had been inoculated with a suspension of H. pylori X47-2AN were divided in 10 groups (each containing five mice) that were sacrificed at different times (H, hour; W, week[s]; M, months). The numbers of cDNA copies per half stomach normalized to the expression of mouse G3PDH were determined. Horizontal bars represent the geometric means for mice (n = 5) sacrificed at each time point.

In any case, an increase in the expression of each gene was detected during the early stages of infection: between 1 h and 2 weeks postinoculation for 16S rRNA (P = 0.011), ureA (P = 0.05), and katA (P = 0.016) (Fig. 2A to C) and between 1 and 3 weeks for alpA (P = 0.0002) (Fig. 2D). However, whether this increased was due to an up regulation of gene expression per (CFU per se or merely reflected an increase of the bacterial burden in the mouse stomach remained to be determined.

Comparison of levels of expression of target genes in human biopsy samples and in mouse stomachs.

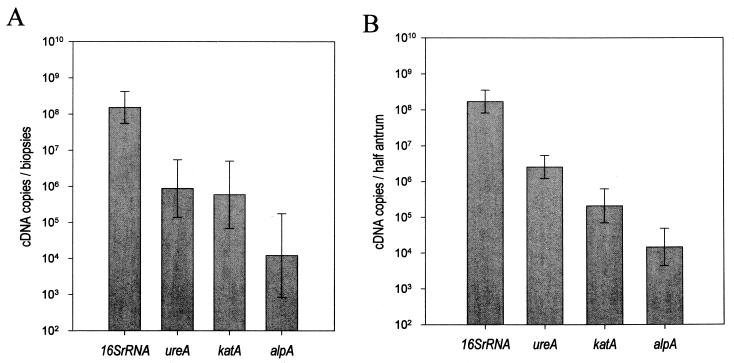

To assess the relevance of the mouse model to humans, expression of the four selected H. pylori genes was quantified in gastric biopsy samples from 15 patients infected with H. pylori and five negative controls. The results showed that the four genes tested were expressed in all infected patients (Fig. 3A). No expression was detected in the negative controls. However, the amounts of the transcripts were not equivalent: the levels of 16S rRNA transcripts (mean, around 108 copies/2 biopsy samples) were found to be higher than levels of ureA and katA transcripts (around 106 copies/2 biopsy samples) and alpA transcripts (mean, 104 copies/2 biopsy samples). In human biopsy samples, as in mice, the predominant cDNA species was 16S rRNA and the least represented was alpA (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Levels of H. pylori gene expression in biopsy samples from asymptomatic patients and in mice stomachs. The numbers of cDNA copies corresponding to 16S rRNA, ureA, katA, and alpA genes were determined in two adjacent biopsy samples from the stomach of each of the 15 infected patients and 5 noninfected controls (A). To allow a comparison, the results from Fig. 2 corresponding to 15 mice (data for three groups) [3 weeks, 1 month, and 2 months postinfection]) were pooled (B). The numbers of cDNA copies per two biopsy samples normalized to the expression of human or mouse G3PDH were determined as described in the text. Geometric means and standard deviations are indicated. After DNase I treatment of each RNA preparation, no target gene expression was detected on the cDNA corresponding to the five negative human and five mouse controls (<10 copies/70 ng of total RNA).

In vivo transcription of target genes as a function of bacterial burden in mouse samples.

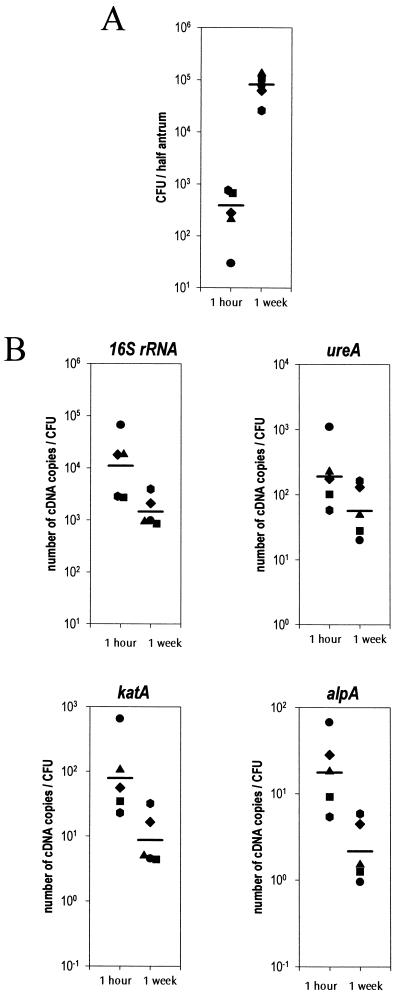

To examine the possible relationship between the bacterial burden and the level of H. pylori gene expression within the gastric mucosa, these parameters were determined simultaneously on the same stomach samples. It was then possible to normalize the number of each transcript to the CFU density (number of cDNA copies per CFU). For this purpose, the levels of infection at 1 h and 1 week postinfection were determined for each mouse, using viable counts (Fig. 4A). The quantification of the number of CFU at 1 h postinfection (mean, 390 CFU/half stomach) showed that only a very small fraction (approximately 1/20,000) of the challenge inoculum was able to colonize the stomach. During the early stages of infection (between 1 h and 1 week), there was a mean 205-fold increase in bacterial density in mouse stomach tissue (mean, 8 × 105 CFU/half stomach) [Fig. 4A]). Figure 4B shows the effect of this increased bacterial density on the expression level of each gene (number of copies per CFU). For the four genes analyzed, the mean number copies of transcripts expressed per CFU was higher at 1 h than at 1 week postinoculation. The differences between the 1-h and 1-week samples in gene expression and bacterial density were statistically significant for 16S rRNA (P = 0.018), katA (P = 0.015), and alpA (P = 0.015) and showed a strong trend for ureA (P = 0.098) These results suggest that the global increase of 16S rRNA, ureA, katA, and alpA expression detected during the early stages of infection in the previous experiment (Fig. 2) could be explained by an increase in bacterial burden in the stomach and not by an up regulation of gene expression per CFU.

FIG. 4.

Influence of bacterial burden on expression levels of H. pylori genes during infection in mice. (A) Quantitative H. pylori culture of gastric tissue on half of the antrum of each mouse was performed on five mouse stomachs at 1 h and 1 week postinfection. (B) The amounts of 16sRNA, ureA, alpA, and katA transcripts were determined for the corresponding mouse stomachs at 1 h and 1 week postinfection. The results were normalized by the number of CFU contained in each preparation used for RT-PCR (cDNA copies/CFU). Horizontal bars represent the geometric means for mice (n = 5) sacrificed at each point.

DISCUSSION

While mouse models have been widely used to identify protective antigens for development of vaccine against H. pylori, to our knowledge, no study has addressed the expression of H. pylori genes in this animal model. To assess the reliability of the mouse model in comparison to human infection, we compared the expression patterns of four selected H. pylori genes within mouse stomachs with those in biopsy samples from infected human subjects. For this purpose, we have developed a real-time RT-PCR to detect H. pylori gene expression kinetics in experimentally infected and chronically infected humans. This study shows that the four genes were expressed in mice throughout the 6-month time course and also within the gastric mucosae of all 15 infected patients (Fig. 2 and 4). The successful detection of the genes in all infected patients indicated that potential variations in the nucleotide sequences of the target genes of the infecting strain did not interfere with the priming of the PCRs. Moreover, the same relative expression level of each gene was found in human and mice mucosae, suggesting that no host-specific regulation occurred. The results obtained with human samples reinforced the observations obtained with the mouse model, as they were independent of the identity of the infecting strain and the time course of infection. Indeed, the infecting strain was probably unique to each patient, based on previous studies on the genomic variability of human H. pylori isolates (15, 31). Comparing the results obtained with these two different hosts, we conclude that that the level of gene expression in the mouse model reliably predicts that in humans.

Two alternative hypothesis may explain the fact that the alpA, ureA, and katA transcripts were always detected within infected gastric mucosae independent of the time course of infection or the identity of the infecting strain: (i) their expression may be constitutive and dependent only on the presence of viable bacteria, or (ii) their expression may be required for successful colonization and persistence of H. pylori in its natural niche. A recent paper indicated that urease expression is regulated by acid exposure (6), suggesting that the second hypothesis may be preferred. Moreover, urease activity has been demonstrated to be required for initial colonization or infection of the host, as genetically constructed urease-negative mutants were found to be unable to colonize the stomachs of nude mice (34) or gnotobiotic piglets (7). Thus, at least urease activity may be essential for the persistent growth of H. pylori in the stomach during chronic infection. While no data on alpA and katA regulation of expression are available, characterization of H. pylori catalase has indicated that the enzyme was highly expressed to allow the bacterium to survive in an environment rich in toxic components (16, 27). Recently it has been reported that catalase activity is essential for the survival of H. pylori at the phagocyte cell surface (29). AlpA is a lipoprotein which has been described as a putative adhesin specific for adherence to human gastric mucosa (26). However, the exact roles of katA and alpA in colonization remain to be determined, and isogenic mutants for this two genes would be required to address this question.

One unexpected aspect of this study was the possibility that the bacterial burden within the gastric mucosa may affect the level of expression of the four genes tested. In the mouse model, we found a significant negative effect of bacterial burden on the expression of 16S rRNA, katA, and alpA at 1 h postinfection compared to 1 week postinfection (Fig. 4). One could argue that at the 1-h time point, adherent bacteria may be present and may not survive in the viability assay used, thus leading to a reduced number of viable CFU compared to the 1-week time point. However, after homogenizing mouse stomachs in the tissue grinder, we used the complete suspensions for viable counts without any centrifugation steps. Under these conditions, we could expect that even adherent bacteria may be able to form CFU after plating on adequate growth media. Whether this observation, the effect of bacterial burden on H. pylori gene expression, was a mechanism to monitor the population density and control the expression of specific genes in response to population density or was due simply to a reduced metabolism (including RNA synthesis) in response to nutrients limitation at high density remains to be assessed. As originally described for luminescent organisms, population density is an important factor in bacterial physiology, often associated with growth phase effects, which affects expression of dozen of genes of bacteria approaching stationary phase and has been reported for many bacteria (for a review, see reference 23). Several lines of evidence suggest that H. pylori produces quorum-sensing molecules; however, while the existence of a functional luxS homologue which is required for the production of autoinducer 2 in Vibrio harveyi has been reported in two independent studies (12, 19), no role of this signaling molecule in regulating any H. pylori gene expression has been reported. Whether or not any quorum-sensing mechanism or molecule is responsible for the effect described in this study remains to be determined.

Overall, this work showed that quantitative RT-PCR assay is a powerful tool for the analysis H. pylori gene expression in situ and that the mouse model may be a useful model for the characterization of H. pylori genome expression during infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank S. Gimenez and V. Sanchez for excellent technical assistance with animals and C. Hessler for performing statistical analysis. T. Monath, H. Kleanthous, and L. Lissolo are acknowledged for critical reading of the manuscript. We are grateful to C. Moste for support and to O. Gandrillon for helpful discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alarcon T, Domingo D, Lopez-Brea M. Antibiotic resistance problems with Helicobacter pylori. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 1999;12:19–26. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(99)00051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alm R A, Ling L S, Moir D T, King B L, Brown E D, Doig P C, Smith D R, Noonan B, Guild B C, deJonge B L, Carmel G, Tummino P J, Caruso A, Uria-Nickelsen M, Mills D M, Ives C, Gibson R, Merberg D, Mills S D, Jiang Q, Taylor D E, Vovis G F, Trust T J. Genomic-sequence comparison of two unrelated isolates of the human gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1999;397:176–180. doi: 10.1038/16495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atherton J C, Cao P, Peek R M J, Tummuru M K, Blaser M J, Cover T L. Mosaicism in vacuolating cytotoxin alleles of Helicobacter pylori. Association of specific vacA types with cytotoxin production and peptic ulceration. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17771–17777. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.30.17771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beier D, Frank R. Molecular characterization of two-component systems of Helicobacter pylori. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:2068–2076. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.8.2068-2076.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buckley M J, Xia H X, Hyde D M, Keane C T, O'Morain C A. Metronidazole resistance reduces efficacy of triple therapy and leads to secondary clarithromycin resistance. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:2111–2115. doi: 10.1023/a:1018882804607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dong Q, Hyde D, Herra C, Kean C, Murphy P, Morain O, Buckley M. Identification of genes regulated by prolonged acid exposure in Helicobacter pylori. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2001;96:245–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eaton K A, Brooks C L, Morgan D R, Krakowka S. Essential role of urease in pathogenesis of gastritis induced by Helicobacter pylori in gnotobiotic piglets. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2470–2475. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.7.2470-2475.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eaton K A, Krakowka S. Effect of gastric pH on urease-dependent colonization of gnotobiotic piglets by Helicobacter pylori. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3604–3607. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.9.3604-3607.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feldman R A, Eccersley A J, Hardie J M. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori: acquisition, transmission, population prevalence and disease-to-infection ratio. Br Med Bull. 1998;54:39–53. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a011678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferrero R L, Thiberge J M, Huerre M, Labigne A. Recombinant antigens prepared from the urease subunits of Helicobacter spp.: evidence of protection in a mouse model of gastric infection. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4981–4989. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.4981-4989.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferrero R L, Thiberge J M, Kansau I, Wuscher N, Huerre M, Labigne A. The GroES homolog of Helicobacter pylori confers protective immunity against mucosal infection in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6499–6503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Forsyth M H, Cover T L. Intercellular communication in Helicobacter pylori: luxS is essential for the production of an extracellular signaling molecule. Infect Immun. 2000;68:3193–3199. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.6.3193-3199.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guy B, Hessler C, Fourage S, Haensler J, Vialon-Lafay E, Rokbi B, Millet M J. Systemic immunization with urease protects mice against Helicobacter pylori infection. Vaccine. 1998;16:850–856. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00258-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guy B, Hessler C, Fourage S, Rokbi B, Millet M J. Comparison between targeted and untargeted systemic immunizations with adjuvanted urease to cure Helicobacter pylori infection in mice. Vaccine. 1999;17:1130–1135. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00332-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han S R, Zschausch H C, Meyer H G, Schneider T, Loos M, Bhakdi S, Maeurer M J. Helicobacter pylori: clonal population structure and restricted transmission within families revealed by molecular typing. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:3646–3651. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.10.3646-3651.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hazell S, Evans D J, Jr, Evans D G, Graham D Y. Helicobacter pylori catalase. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:57–61. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-1-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higuchi R K, Fockler C, Dollinger G, Watson R. Kinetic PCR: Real-time monitoring of DNA amplification reactions. BioTechnology. 1993;11:1026–1030. doi: 10.1038/nbt0993-1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ilver D, Arnqvist A, Ogren J, Frick I M, Kersulyte D, Incecik E T, Berg D E, Covacci A, Engstrand L, Boren T. Helicobacter pylori adhesin binding fucosylated histo-blood group antigens revealed by retagging. Science. 1998;279:373–377. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joyce E A, Bassler B L, Wright A. Evidence for a signaling system in Helicobacter pylori: detection of a luxS-encoded autoinducer. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:3638–3643. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.13.3638-3643.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karita M, Tummuru M K, Wirth H P, Blaser M J. Effect of growth phase and acid shock on Helicobacter pylori cagA expression. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4501–4507. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4501-4507.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kleanthous H, Myers G A, Georgakopoulos K M, Tibbitts T J, Ingrassia T W, Gray H L, Ding R, Zhang Z Z, Lei W, Nichols R, Lee C K, Ermak T H, Monath T P. Rectal and intranasal immunizations with recombinant urease induce distinct local and serum immune responses in mice and protect against Helicobacter pylori infection. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2879–2886. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2879-2886.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krishnamurthy P, Parlow M H, Schneider J, Burroughs S, Wickland C, Vakil N B, Dunn B E, Phadnis S H. Identification of a novel penicillin-binding protein from Helicobacter pylori. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5107–5110. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.16.5107-5110.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lazazzera B A. Quorum sensing and starvation: signals for entry into stationary phase. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2000;3:177–182. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(00)00072-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marchetti M, Rossi M, Giannelli V, Giuliani M M, Pizza M, Censini S, Covacci A, Massari P, Pagliaccia C, Manetti R, Telford J L, Douce G, Dougan G, Rappuoli R, Ghiara P. Protection against Helicobacter pylori infection in mice by intragastric vaccination with H. pylori antigens is achieved using a non-toxic mutant of E. coli heat-labile enterotoxin (LT) as adjuvant. Vaccine. 1998;16:33–37. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marshall B J, Annear C S, Goodwin J W, Pearman J R, Warren J R, Amstrong J A, Royce D I. Original isolation of Campylobacter pyloridis from human gastric mucosa. Microbios Lett. 1983;25:83–88. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Odenbreit S, Till M, Hofreuter D, Faller G, Haas R. Genetic and functional characterization of the alpAB gene locus essential for the adhesion of Helicobacter pylori to human gastric tissue. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:1537–1548. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Odenbreit S, Wieland B, Haas R. Cloning and genetic characterization of Helicobacter pylori catalase and construction of a catalase-deficient mutant strain. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6960–6967. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.23.6960-6967.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Radeliff F J, Hazell S L, Kolesnikow T, Doidge C, Lee A. Catalase, a novel antigen for Helicobacter pylori vaccination. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4668–4674. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4668-4674.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramarao N, Gray-Owen S D, Meyer T F. Helicobacter pylori induces but survives the extracellular release of oxygen radicals from professional phagocytes using its catalase activity. Mol Microbiol. 2000;38:103–113. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Satin B, Del Giudice G, Della B V, Dusi S, Laudanna C, Tonello F, Kelleher D, Rappuoli R, Montecucco C, Rossi F. The neutrophil-activating protein (HP-NAP) of Helicobacter pylori is a protective antigen and a major virulence factor. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1467–1476. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.9.1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suerbaum S, Smith J M, Bapumia K, Morelli G, Smith N H, Kunstmann E, Dyrek I, Achtman M. Free recombination within Helicobacter pylori Proc. Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:12619–12624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sutton P, Wilson J, Lee A. Further development of the Helicobacter pylori mouse vaccination model. Vaccine. 2000;18:2677–2685. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tomb J F, White O, Kerlavage A R, Clayton R A, Sutton G G, Fleischmann R D, Ketchum K A, Klenk H P, Gill S, Dougherty B A, Nelson K, Quackenbush J, Zhou L, Kirkness E F, Peterson S, Loftus B, Richardson D, Dodson R, Khalak H G, Glodek A, McKenney K, Fitzegerald L M, Lee N, Adams M D, Venter J C. The complete genome sequence of the gastric pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nature. 1997;388:539–547. doi: 10.1038/41483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsuda M, Karita M, Mizote T, Morshed M G, Okita K, Nakazawa T. Essential role of Helicobacter pylori urease in gastric colonization: definite proof using a urease-negative mutant constructed by gene replacement. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1994;6(Suppl. 1):S49–S52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Warren J R, Marshall B J. Unidentified curved bacilli on gastric epithelium in active chronic gastritis. Lancet. 1984;1:1273–1275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wittwer C T, Ririe K M, Andrew R V, David D A, Gundry R A, Balis U J. The LightCycler: a microvolume multisample fluorimeter with rapid temperature control. BioTechniques. 1997;22:176–181. doi: 10.2144/97221pf02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]