Abstract

Lewis (Le) antigens have been implicated in the pathogenesis of atrophic gastritis and gastric cancer in the setting of Helicobacter pylori infection, and H. pylori-induced anti-Le antibodies have been described that cross-react with the gastric mucosa of both mice and humans. The aim of this study was to examine the presence of anti-Le antibodies in patients with H. pylori infection and gastric cancer and to examine the relationships between anti-Le antibody production, bacterial Le expression, gastric histopathology, and host Le erythrocyte phenotype. Anti-Le antibody production and H. pylori Le expression were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, erythrocyte Le phenotype was examined by agglutination assays, and histology was scored blindly. Significant levels of anti-Lex antibody (P < 0.0001, T = 76.4, DF = 5) and anti-Ley antibody (P < 0.0001, T = 73.05, DF = 5) were found in the sera of patients with gastric cancer and other H. pylori-associated pathology compared with H. pylori-negative controls. Following incubation of patient sera with synthetic Le glycoconjugates, anti-Lex and -Ley autoantibody binding was abolished. The degree of the anti-Lex and -Ley antibody response was unrelated to the host Le phenotype but was significantly associated with the bacterial expression of Lex (r = 0.863, r2 = 0.745, P < 0.0001) and Ley (r = 0.796, r2 = 0.634, P < 0.0001), respectively. Collectively, these data suggest that anti-Le antibodies are present in most patients with H. pylori infection, including those with gastric cancer, that variability exists in the strength of the anti-Le response, and that this response is independent of the host Le phenotype but related to the bacterial Le phenotype.

Helicobacter pylori is a prevalent human pathogen, and chronic infection of the gastric mucosa by the bacterium results in the development and recurrence of human gastritis, gastric and duodenal ulcers, and an increased risk of gastric cancer and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma (11). The cell envelope of H. pylori, like those of other gram-negative bacteria, contains lipopolysaccharides (LPSs), the O-polysaccharide chain of which expresses blood group antigens similar to those of the host (5–7, 22, 23, 33). These antigens are predominantly type 2 blood group determinants Lewis x (Lex) and Lewis y (Ley), although type 1 blood group determinants Lewis a (Lea) and Lewis b (Leb) have also been described (5–7, 18, 23, 40). Since these determinants are present in the gastric mucosa of normal individuals, bacterial expression of these antigens has been suggested to camouflage the bacterium and aid in colonization (3, 22, 25, 26, 29, 33). In addition, H. pylori LPS, by inducing a low immunological response, may prolong H. pylori infection longer than would occur with a more aggressive pathogen (25).

Lex and Ley antigens have been implicated in the pathogenesis of atrophic gastritis in the setting of H. pylori infection (30, 31). Autoimmunity may also play a critical role in the pathogenesis of H. pylori-linked carcinoma and MALT lymphoma (16, 38). Negrini et al. reported that H. pylori-induced antibodies cross-reacted with gastric mucosa in both mice and humans and that chronic gastritis could be induced in mice by hybridoma cells, which produced a cross-reacting anti-Ley antibody (4, 30, 31). Also, it has been demonstrated that human and mouse H+,K+-ATPases express Ley and Ley+Lex, respectively, and that both gastric mucin and the gastric H+,K+-ATPase β chain are potential targets of H. pylori-induced antibodies (4). Other studies have shown that the onset of gastritis and autoantibody production parallels the expression of H+,K+-ATPase during ontogeny in a BALB.D2 Mls-1a mouse model of autoimmune gastritis, and that exposure of the neonatal peripheral immune system to native stomach antigens does not prevent autoimmunity, but rather leads to adverse autoimmune lesions in the target organ (10). In humans, sera from dyspeptic patients with H. pylori infection inhibited the binding of an antibody recognizing Lex and, moreover, the extent of inhibition correlated with their reactivity with purified LPS (4).

The present study investigates further the role of the blood group determinants Lex and Ley on H. pylori LPS in H. pylori-mediated autoimmunity. We determined the presence of Lex and Ley epitopes on H. pylori clinical isolates from an unselected group of consecutive patients undergoing upper endoscopy and correlated the presence of these antigens with the levels of anti-Lex and anti-Ley antibodies in patient sera. In addition, we examined the sera of 48 individuals with biopsy-proven gastric cancer from a geographical area of high H. pylori occurrence to determine the prevalence of anti-Lex and Ley antibodies in vivo in patients with gastric cancer, thereby testing the hypothesis that anti-Lex and anti-Ley antibodies may play a role in H. pylori-mediated autoimmunity and in gastric cancer pathogenesis. The role of host Le antigen phenotype was also evaluated with respect to the strength of the anti-Le antibody response in our patient groups.

(A preliminary report of this research was presented at the 8th United European Gastroenterology Week, Brussels, Belgium, 25 to 30 November 2000.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients.

Subjects were recruited from a group of 207 consecutive persons attending the open-access endoscopy service at University College Hospital, Galway, Ireland, and included 120 men and 87 women (mean age, 54 years; range, 13 to 90 years). Persons who had received antibiotics, H2 receptor antagonists, or proton pump inhibitors during the 4 weeks prior to upper gastrointestinal endoscopy were excluded. All patients were Irish, and all were Caucasian. Serum was also available from 48 consecutive subjects with gastric cancer from an area of high prevalence of H. pylori infection (Kaunas, Lithuania). All patients gave informed consent for inclusion in this study.

Specimens and analysis.

For Irish patients, during upper endoscopy three gastric antral biopsy specimens were obtained using the same size biopsy forceps from similar topographical sites at each endoscopy from within 3 cm of the pylorus. Fundal biopsies were obtained only when endoscopic examination suggested gastric atrophy. Blood samples (10 ml) were collected into tubes containing EDTA and clot activator at the time of endoscopy from a single venepuncture site immediately prior to the administration of sedation.

One of the antral biopsy specimens was cultured for H. pylori, and confirmatory biochemical and microscopic tests were performed (39). Stock cultures were maintained at −70°C in horse serum supplemented with 20% glycerol and, when required for characterization, H. pylori isolates were cultured on blood agar for 48 h and identified as described above. A second biopsy was smeared on a glass slide and examined for H. pylori using a Giemsa stain. Sections of the third biopsy specimen embedded in paraffin wax were prepared and stained with hematoxylin and eosin stain for light microscopy as described previously (19) and assessed subjectively by one blinded histopathologist for H. pylori colonization density. Sections were graded 0 to 3, corresponding, respectively, to absent, scant, moderate, and heavy bacterial colonization. The severity and activity of gastritis in the same specimens were also graded 0 to 3, according to the criteria described previously (19). For all patients, antibodies (immunoglobulin G) against H. pylori were measured in patient sera by a qualitative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using a commercially available kit (HM-CAP; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.), according to the manufacturer's instructions. H. pylori infection was defined as being present if the culture alone or any combination of two other tests was positive (18, 19).

Determination of H. pylori blood group antigen phenotype.

Cells of H. pylori isolates were harvested from blood agar plates and prepared as described previously (18). Protein concentrations of cell suspensions were determined using a Pierce protein assay detection system (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.). Subsequently, an ELISA with whole bacterial cells (40) was used as described previously (18) to determine the reaction of anti-Le antigen monoclonal antibodies (MAbs; Signet Labs, Inc., Dedham, Mass.) with the whole cells. The specificities of the antibodies in the assay were validated by their ability to recognize synthetic Le antigens, Ley conjugated to human serum albumin (Ley-HSA; Isosep AB, Tulinge, Sweden), and Lex conjugated to bovine serum albumin (Lex-BSA; Dextra Laboratories, Reading, United Kingdom), respectively, and the LPS of H. pylori NCTC 11637, P466, and MO19 containing polymeric Lex, polymeric Lex with terminal monomeric Ley, and Ley monomer, respectively (5–7). In addition to controls without primary or secondary antibody, wells coated with Escherichia coli J5 were included in each assay as negative controls. The optical density values measured at 492 nm (OD492) were considered positive for the presence of blood group antigens if the OD was greater than 0.3 OD492 units (ODU), since nonspecific binding never exceeded this value.

Determination of the presence of anti-Lex and anti-Ley antibodies in serum.

To determine whether or not antibodies to Lex and/or Ley were present in patient sera, experiments were performed in which patient serum was incubated overnight with LPS, bacterial whole cells, and Le glycoconjugates to evaluate whether addition of patient serum reduced binding of the commercial anti-Lex and anti-Ley antibodies. For experiments using bacterial whole cells, preparations of H. pylori NCTC 11637 and P466 were prepared as described above. Flat-bottom microtiter plates were coated overnight with 100 μl of twofold dilutions of H. pylori cell suspensions in bicarbonate coating buffer (40). Twofold dilutions of patient serum (100 μl of phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] plus 1% fetal calf serum plus patient serum) were added and incubated overnight at 37°C, blocked with 2% BSA for 2 h and, subsequently, incubated with twofold dilutions of anti-Le mouse MAb in PBS containing 1% BSA and 0.1% Tween 20 (PBS-BSA-Tween) at 37°C for 2 h. Between incubation steps, wells were washed three times with PBS-Tween. Specificity of MAb binding was defined as in the previous experiments. Bound mouse antibodies were detected using goat anti-mouse antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (Sigma). Thus, inhibition of the binding of commercially available anti-Lex and anti-Ley antibodies by patient sera was measured. Control experiments were performed as before.

Experiments with glycoconjugates and purified LPS were conducted in a similar manner but with 10 μg of Lex-BSA or Ley-HSA and also purified LPS from H. pylori strains NCTC 11637, P466, and MO19 coated onto microtiter plates overnight in bicarbonate coating buffer.

Absorption experiments.

To determine whether the binding of patient sera which had reacted with Lex and Ley epitopes in the previous ELISA experiments could be removed or reduced, sera were pretreated by incubation with glycoconjugates of Lex-BSA or Ley-HSA at room temperature overnight before testing. Absorbed sera were added in the ELISA experiments, and the reduction in inhibition of binding of commercially available anti-Lex and anti-Ley antibodies was measured.

Host Le blood group antigen typing.

Host Le antigen phenotypes were determined with a macroscopic tube agglutination technique on washed erythrocytes, within 24 h of collection, using commercially available murine anti-Lea and anti-Leb blood grouping reagents (Bioscot Labs, Edinburgh, Scotland) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis.

For quantitative data, analysis was performed using the Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis tests for comparisons of two, and more than two, independent groups, respectively. The colonization density of H. pylori and the lymphocyte and neutrophil densities were expressed as the means ± the standard error of the mean. Correlations were performed between continuous variables using either linear regression with Pearson's product moment correlation or by calculation of Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (rs). Significance was set at the 5% level (two-tailed P). All data analysis was performed using StatsDirect statistical software package, version 1.7.3.

RESULTS

Patients, H. pylori infection, and pathologies.

Of the 207 patients undergoing endoscopy. H. pylori isolates were available for analysis in 84 (49 men and 35 women; mean age, 51.2 years; range, 17 to 90 years). Of these, 78 (93%) had endoscopically visible disease. Twelve patients (14%) showed duodenal ulceration, and ten (12%) showed gastric ulceration, all in conjunction with antral gastritis. Fifty-six patients (67%) had endoscopic evidence of chronic gastritis, and six patients (7%) had normal endoscopic findings. These patients were classified as having nonulcer dyspepsia after sonography of the upper abdomen was found to be normal. Of the Irish patients who were H. pylori negative (n = 123) by our defined criteria (culture negative, histology negative, serology negative), serum was examined from 60 of these patients for the presence of anti-Le antibodies. This group is referred to as the control group in the remainder of this study. All patients with gastric cancer were H. pylori positive.

Presence of anti-Lex and anti-Ley antibodies in sera of patients with H. pylori-related pathologies.

ELISA experiments were undertaken using whole cells of H. pylori, glycoconjugates of Le antigens, or H. pylori LPS to determine whether or not anti-Le antibodies were present in the serum of our patient groups. Results of the greatest consistency were obtained when purified LPS was coated onto the ELISA plates and, therefore, this methodology was used throughout the study. In particular, in experiments in which glycoconjugate-coated ELISA plates were used, consistent results were obtained in only about 50% of tests, suggesting that synthetic glycoconjugates were inefficiently bound within the experimental system or that antigen presentation by glycoconjugates was suboptimal and variable between experiments. Consistent with the latter suggestion, it has been shown previously (4) that bound glyconjugates of monomeric Lex or Ley were less effective at detecting anti-Le antibodies in H. pylori-positive sera than were bound polymeric Le antigens similar to those found in H. pylori LPS. In addition, a comparative study of the binding of anti-Le antibodies to soluble and plate-coated glycoconjugates was performed to assess the influence of soluble versus solid-phase presentation of antigen for anti-Le antibody recognition. This validation study found greater and more consistent antibody binding to soluble (100%) than to the plate-bound Le glycoconjugates.

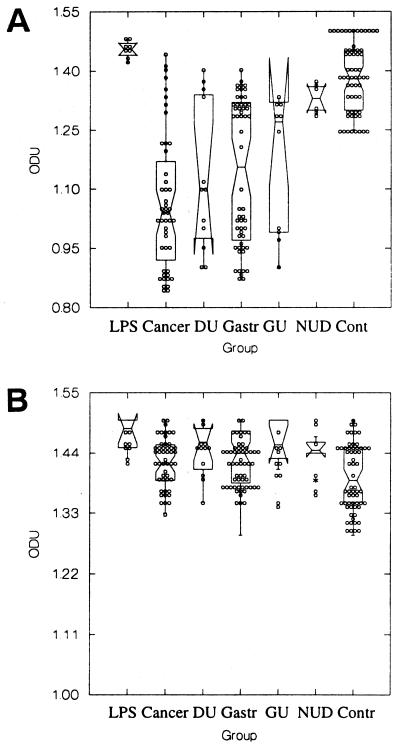

Binding of commercially available anti-Lex antibody to the LPS of H. pylori NCTC 11637 (Fig. 1A), which expresses Lex, was measured at a median of 1.45 ODU (range, 1.42 to 1.48 ODU). When patient sera were incubated with the LPS of NCTC 11637, a significant reduction in binding of commercial anti-Lex antibody was found for patients with gastric cancer, duodenal ulceration, chronic gastritis, and gastric ulceration compared with the control group that was H. pylori negative (P < 0.0001, T = 76.4, DF = 5, Kruskal-Wallis test). To confirm that the observed immune responses were related to Lex determinants on the O-side chains of LPS alone and not due to reaction with other areas within H. pylori LPS, such as the core region or lipid A region, absorption experiments were performed. After absorption of the patient sera with synthetic Lex glycoconjugate, binding of the commercial anti-Lex antibody was enhanced significantly for all disease groups (Fig. 1B). The ODU readings from all patient groups fell within the range observed for the patients who were H. pylori negative, and no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) was found between groups for binding of the anti-Lex antibody.

FIG. 1.

Inhibition of binding of commercially available anti-Lex antibody to Lex-expressing H. pylori LPS (NCTC 11637) by patient sera of different disease groups before absorption (A) and after absorption (B) with Lex glycoconjugate. Direct binding of commercial anti-Lex antibody alone to the LPS was measured (LPS), and the abilities of unabsorbed or absorbed sera from gastric cancer (Cancer), duodenal ulcer (DU), chronic gastritis (Gastr), gastric ulcer (GU), and nonulcer dyspepsia (NUD) patients, as well as from a control group (Cont), to inhibit the binding of the commercial antibody were determined. Excluding the control group, a significant enhancement of binding of the commercially available anti-Lex antibody was found when absorbed patient sera were tested.

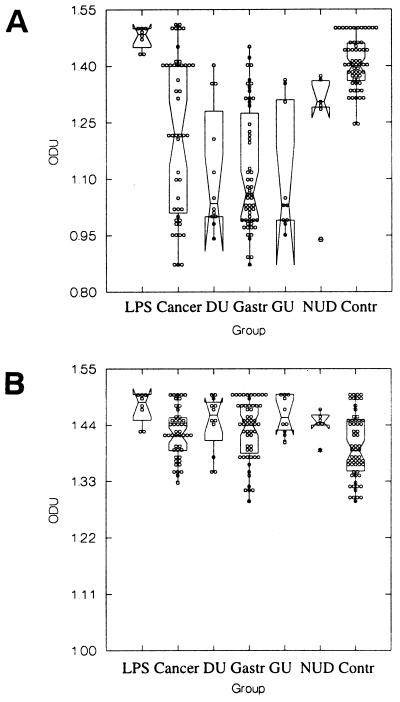

In a similar manner, direct binding of commercial anti-Ley antibody to the LPS of H. pylori P466 (Fig. 2A), which expresses Ley, measured 1.485 ODU (range, 1.43 to 1.5 ODU). When patient sera were incubated with the P466 LPS, a significant reduction in binding of anti-Ley antibody was again found in patients with gastric cancer, duodenal ulceration, chronic gastritis, and gastric ulceration compared to H. pylori-negative controls. Also, the difference in antibody binding between patients with nonulcer dyspepsia and controls was significant (P < 0.0001, T = 73.05, DF = 5, Kruskal-Wallis test). Absorption of patient sera with synthetic Ley glycoconjugate was performed and, excluding the control group, a significant enhancement of binding of the commercially available anti-Lex antibody was found when absorbed patient sera were tested (Fig. 2B). The ODU readings from all patient groups fell within the range observed for the H. pylori-negative controls, and no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) was found between groups for binding of the anti-Ley antibody.

FIG. 2.

Inhibition of binding of commercially available anti-Ley antibody to Ley-expressing H. pylori LPS (P466) by patient sera of different disease groups before absorption (A) and after absorption (B) with Ley glycoconjugate by patient sera of different disease groups. Direct binding of commercial anti-Ley alone to the LPS was measured (LPS), and the abilities of unabsorbed or absorbed sera from gastric cancer (Cancer), duodenal ulcer (DU), chronic gastritis (Gastr), gastric ulcer (GU), and nonulcer dyspepsia (NUD) patients, as well as from a control group (Cont), to inhibit binding of the commercial antibody were determined. Excluding the control group, a significant enhancement of binding of the commercially available anti-Lex antibody was found when absorbed patient sera were tested.

Moreover, for both anti-Lex and anti-Ley antibodies, and in all disease groups, a range of inhibition of commercial anti-Le antibody binding was observed (Fig. 1A and 2A), suggesting that the potency of the anti-Le response varies between individual patients.

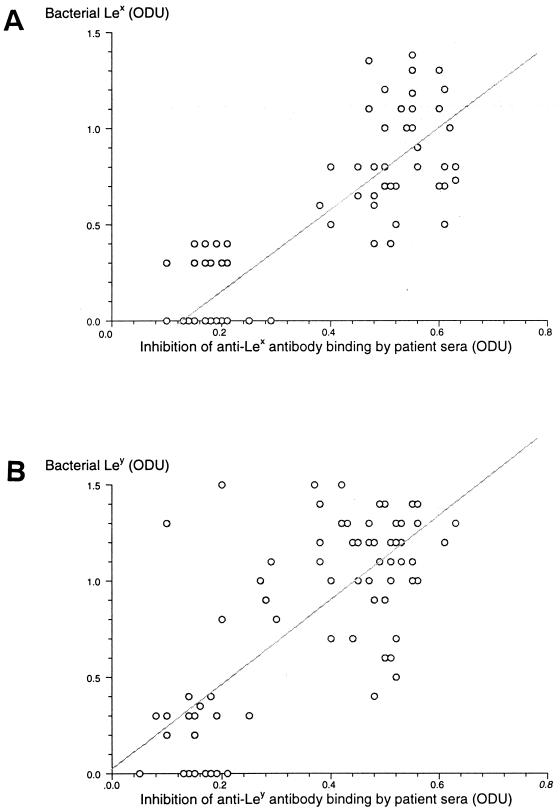

Relationship of bacterial Le expression to anti-Lex and anti-Ley antibodies.

Eighty-eight percent (74 of 84) of H. pylori isolates were identified as having Lex, Ley, or a combination of Lex and Ley expressed on their LPS. This total included 4 strains (5%) with Lex alone, 23 strains (27%) with Ley alone, and 47 strains (56%) expressing both Lex and Ley. Ten isolates (12%) had no evidence of either Lex or Ley expression on their LPS. Figure 3 shows the relationships between the presence of anti-Lex and anti-Ley antibodies in patient sera, and the expression of Lex and Ley on the H. pylori isolates from the same patients. The ODU values obtained for the amount of Lex and Ley on individual isolates is plotted against the ODU values of inhibition of binding of commercial anti-Lex or -Ley antibody, respectively, to H. pylori LPS by patient sera. Using Pearson's product moment correlation, a highly significant correlation was found between the presence of Lex determinants on H. pylori isolates and the presence of anti-Lex antibody (Fig. 3A; r = 0.863, r2 = 0.745, P < 0.0001) and bacterial expression of Ley determinants and the presence of anti-Ley antibody in patient sera (Fig. 3B; r = 0.796, r2 = 0.634, P < 0.0001).

FIG. 3.

Correlation of inhibition of binding of commercial anti-Lex (A) and anti-Ley (B) antibodies by the sera of H. pylori-positive patients with bacterial expression of Lex and Ley, respectively, on isolates from the same patients.

Relationship of host Le phenotype to anti-Lex and anti-Ley responses.

Lewis blood typing can identify both the Le antigen phenotype and the secretor status of most individuals. Leb is the predominant blood group antigen expressed on epithelial cell surfaces and the erythrocytes of secretors, whereas Lea is that expressed by nonsecretors, but expression of both type 1 and type 2 Le antigens occurs in the gastric mucosa (22, 33). In particular, surface and foveolar epithelia coexpress either Lea and Lex in nonsecretors or Leb and Lex in secretors and, hence, it was of interest to determine whether a relationship existed between host Le phenotype and anti-Le responses. Of the 84 H. pylori-positive patients, 58 (69%) were secretors [Le(a−,b+)], 21 (25%) were nonsecretors [Le(a+,b−)], and 5 (6%) had the recessive [Le(a−,b−)] phenotype. Since secretor status cannot be determined from the recessive [Le(a−,b−)] phenotype and since salivary testing is required, patients with the recessive phenotype were excluded from further analysis. Random analysis of gastric biopsies for Le antigen expression gave consistent results with those of erythrocyte typing. Patients who expressed Lea on their erythrocytes or epithelial surfaces (nonsecretors) were not more likely to have higher levels of anti-Lex antibody present in their sera than secretors who expressed Leb (1.147 ± 0.187 ODU versus 1.16 ± 0.177 ODU; P = 0.677, Mann-Whitney test) and, also, secretors did not produce a significantly higher level of anti-Ley LPS antibody than nonsecretors (1.117 ± 0.162 ODU versus 1.155 ± 0.175 ODU; P = 0.524, Mann-Whitney test).

Histological findings and anti-Lex and anti-Ley antibody production.

Using Spearman's correlation coefficient, we examined the relationships between anti-Lex and anti-Ley antibody production and bacterial colonization density, as well as lymphocyte and neutrophil inflammatory responses in patients classified into two groups: those with peptic ulceration and those with chronic gastritis alone, excluding patients with nonulcer dyspepsia (Table 1). For both groups, no statistically significant association (P > 0.05) was identified between anti-Lex and anti-Ley antibody production and any of the histological parameters. However, a trend toward significance (rs = 0.407, P = 0.060) was observed between the antral lymphocyte infiltrate and the anti-Lex antibody response in the cohort of patients with peptic ulceration. A similar, but less significant, trend (rs = 0.216, P = 0.108) was noted between the observed lymphocyte infiltrate and the anti-Ley response in the cohort of patients with chronic gastritis.

TABLE 1.

Relationship of amount of anti-Lex and anti-Ley antibodies in sera of H. pylori-infected patients to colonization density, lymphocyte infiltrate, and neutrophil infiltrate in ulcer and chronic gastritis diseasea

| Comparison | Ulcer patients

|

Chronic gastritis patients

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs | P | 95% CI | rs | P | 95% CI | |

| Anti-Lex antibodies versus: | ||||||

| H. pylori colonization density | 0.111 | 0.617 | −0.32–0.61 | 0.127 | 0.347 | −0.139–0.377 |

| Lymphocyte infiltrate | 0.407 | 0.060 | −0.01–0.707 | −0.035 | 0.796 | −0.295–0.229 |

| Neutrophil infiltrate | 0.062 | 0.781 | −0.471–0.369 | 0.032 | 0.795 | −0.229–0.295 |

| Anti-Ley antibodies versus: | ||||||

| H. pylori colonization density | 0.173 | 0.217 | −0.268–0.554 | −0.026 | 0.879 | −0.282–0.243 |

| Lymphocyte infiltrate | 0.228 | 0.190 | −0.151–0.633 | 0.216 | 0.108 | −0.048–0.453 |

| Neutrophil infiltrate | −0.017 | 0.935 | −0.406–0.436 | 0.169 | 0.210 | −0.097–0.414 |

CI, confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

The results of the present study provide evidence for a relationship between Lex and Ley antigen expression on H. pylori isolates and the development of anti-Le induced antibodies in their infected hosts. In addition, we have identified anti-Lex and anti-Ley antibodies in the sera of patients with gastric cancer. Sera from H. pylori-infected patients reacted much more strongly with the LPS of H. pylori NCTC 11637 and P466, expressing polymeric Lex and polymeric Lex with terminal monomeric Ley (5–7), respectively, than sera from noninfected controls (Fig. 1 and 2). These experiments also demonstrated for the first time that not only do antibodies found in the serum of patients infected with H. pylori cross-react with LPS but these antibodies also recognize Le epitopes within LPS. It has been suggested previously that a major fraction of the human serum response to the LPS of H. pylori-infected individuals might be directed toward the LPS core or lipid A regions (4) or non-Le epitopes present in the O-polysaccharide chain of LPS (43, 44). The results of the present study clearly show the reaction of human sera with Le epitopes within LPS; first, because of the methodology of the inhibition ELISA which determined binding of commercial anti-Lex or -Ley antibodies to LPS after reaction with patient sera (Fig. 1A and 2A) and, second, by the reduction of inhibition within the ELISA of anti-Le autoantibodies when patient sera were preincubated with synthetic Le glycoconjugates in absorption experiments (Fig. 1B and 2B).

That the experimental system performed at its optimal when LPS, rather than whole cells or synthetic glyconjugates, was coated onto reaction plates is also noteworthy, since it demonstrates that antigen presentation may be of importance in the recognition of an epitope by an autoreactive antibody, as suggested previously (25). In particular, glycoconjugate-coated ELISA plates yielded consistent results in only about 50% of tests compared to LPS-coated plates, and a comparative analysis of anti-Le antibody binding to soluble and plate-bound Le glycoconjugates showed greater and more consistent antibody binding to the former antigen format. Moreover, a previous comparative study of serological assays using different antigen presentation formats has shown differences in ability to detect anti-Lex and anti-Ley antibodies in H. pylori-positive patient sera (20). Although glycoconjugate-coated ELISA plates have been applied previously to detect anti-Le antibodies in H. pylori patient sera and could not effectively demonstrate differences compared to control sera (1), those studies which have used ELISA with LPS or cell-derived preparations were able to show differences between infected and noninfected individuals (4, 34), again reflecting the importance of the antigen presentation format. Consistent with this interpretation, the commercially available synthetic Le glycoconjungates that were used in the present and previous (42) studies contained monomeric Le antigens only but, in a small study, plate-coated glyconjugates of monomeric Lex or Ley were found to be less effective in binding anti-Le antibodies in H. pylori-positive sera than were natural polymeric Le antigens (4), which were similar to those found in H. pylori LPS (5–7, 23).

Yokota et al. (42) have reported in their study of Japanese H. pylori isolates that the antigenicity of the O-polysaccharide chain varied depending on the strain and disease group; particularly, those from gastric tumors showed low antigenicity. Moreover, in the present study, the potency of the anti-Le response varied between individual patients, possibly reflecting these differences in antigenicity but also reflecting the immune responsiveness of the host. In further studies, Yokota et al. (43, 44) reported the occurrence of a highly antigenic epitope and a weakly antigenic epitope, both expressed in the O-polysaccharide of H. pylori, as well as the occurrence of strains not expressing an O-polysaccharide chain (rough-LPS). It is important to note that subculturing of strains in vitro can lead to loss of O chains from H. pylori LPS (27), but in this study isolates were handled to maintain Le antigen expression under the conditions optimized in our previous investigations (18, 19, 39). Although Yokota et al. were unable to correlate the epitopes in the O chains with the presence of Le antigens by the methods they employed (43, 44), the sugar composition of the LPS they analyzed was consistent with the presence of Le antigens (44). Furthermore, attempts by these workers to produce MAbs and rabbit antisera against epitopes independent of Le antigens have failed to date (44), and only anti-Le antibodies have been obtained. Therefore, this raises questions to the identity of the epitopes identified by Yokota et al. (43, 44) and their relationship to Le antigens.

In this study we have determined that the principal determinant of the anti-Le response is not related to host Le phenotype per se but rather to the amount of bacterial Lex and Ley expression. Highly significant correlations were found between the presence of bacterial Lex determinants and the presence of anti-Lex antibody in patient sera (Fig. 3A; r2 = 0.745). Similar, but not as significant, was the correlation between the presence of bacterial Ley determinants and anti-Ley in patient serum (Fig. 3B; r2 = 0.634). These results contrast with those of one study in which absorption experiments with H. pylori to remove autoantibody reactivity against the parietal cells of the gastric mucosa and anti-Le antibodies were unsuccessful (14) but are in agreement with those of another study in which autoantibodies were diminished by absorption with Le-positive H. pylori lysates (30). Moreover, Negrini et al. reported that sera from 84% of patients with H. pylori infection reacted with antral gastric mucosa and 66% of patient sera with corpus gastric mucosa (30, 31) and that the prevalence of anti-Le autoantibodies correlated with lymphocytic infiltrate and gastric gland atophy (31). Consistent with these findings, anti-Ley H. pylori-induced autoreactive antibodies in mice can react with the β chain of the H+,K+-ATPase gastric proton pump (4) but, in the light of the failed absorption experiments with human sera in one study (14), these results were reinterpreted to indicate differences between mouse and human autoantibodies (2).

However, the results of the present study show that this interpretation should be reconsidered. The discrepancies between the results of absorption studies (14, 30) and the inability to detect anti-Ley antibodies in patient sera (9, 25) may reflect the importance of antigen presentation in the test system. First, in the present study, the LPS of H. pylori P466 (which expresses monomeric Ley carried on polymeric Lex) was used in the detection of anti-Ley antibodies rather than a monomeric antigen format. Second, the outer membrane of H. pylori undergoes blebbing, thereby producing outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) which contain LPS expressing Le antigens (15, 21, 25). Interestingly, absorption of patient sera from the present study with synthetic glycoconjugates and OMVs, under the same conditions as used in this study, has yielded preliminary results showing a decrease in their autoreaction with human gastric mucosa (A. P. Moran et al., unpublished data). Differences in the presentation of Le antigens on the OMV surface versus that on the bacterial surface may also explain the difficulties encountered in absorbing anti-Le antibodies from patient sera with bacterial whole-cell lysates in a previous study (14), which led to the conclusion that the production of anti-Le antibodies was independent of bacterial Le expression (9, 14).

We have previously reported that bacterial Lex expression in patients with H. pylori-related ulcer disease was significantly related to lymphocyte infiltration of the gastric mucosa (18). In particular, in patients with chronic gastritis, significant relationships were found between the expression of Lex and H. pylori colonization density and neutrophil and lymphocyte infiltrates, and bacterial Ley expression was related to neutrophil and lymphocyte infiltration. In other studies, experiments indicate that neutrophils are a potential target recognized by anti-Lex antibodies (4, 35). Neutrophils express CD15 (Lex) on members of the adhesion promoting glycoprotein family (CD11/CD18). Anti-Lex MAbs activate and cause enhanced adherence of these cells, which may result in tissue damage and inflammation (4, 35, 36). Also, recent data indicate that Le antigens may play a role in bacterial adhesion to the gastric mucosa (12), thereby aiding the contact of secreted products with the mucosa and thus potentiating the development of the inflammatory response (25). In this study, no significant association was identified between the presence of a potentially autoreactive anti-Le antibody and any histological parameter, although a trend (rs = 0.407, P = 0.060) was observed between antral lymphocyte infiltrate and the anti-Lex response in patients with peptic ulceration. A less significant trend (rs = 0.216, P = 0.108) was noted between the observed lymphocyte infiltrate and the anti-Ley response in the cohort of patients with chronic gastritis. That the predominant inflammatory infiltrates in this group of patients in the setting of anti-Le antibodies are lymphocytes is not, in our opinion, unexpected. Acute inflammatory cells occurring as the predominant cell type would be more likely to be early after colonization with H. pylori, rather than late as in the setting of chronic gastritis. This concept is supported by the fact that the presence of anti-Le antibodies is likely to be determined by the duration of infection with H. pylori (8).

It is unlikely that the presence of anti-Lex and anti-Ley antibodies in H. pylori-positive patients would be solely responsible for both the initiation and the maintenance of an autoimmune response in infected patients. Nevertheless, based upon the available data, it can be speculated that the mechanisms underlying autoantibody production likely include molecular mimicry between constitutively expressed bacterial LPS and those of the gastric mucosa (4, 25, 26, 30, 31), as well as facilitated exposition of the bacterial epitopes to a recruited gastric mucosal immune population which is influenced by host immunoregulation and environmental factors. Subsequently, host structural epitopes could become exposed and presented to the immune system to further drive the autoreactive response, as suggested previously (2, 14). A cross-reactive antibody such as anti-Ley may initiate damage to the proton pump, with subsequent alteration in acid output (4). Changes in acid output can influence the LPS structure of the infecting bacterial strain such that phase variation occurs in the generation of Le epitopes (28) and, hence, a secondary reduction in autoreactive antibody production could occur, thereby confounding interpretation of the role of H. pylori-induced anti-Le antibodies. Moreover, anti-Lex antibodies may augment the immune response by causing complement-mediated lysis of host target cells as observed in other infections (32, 37). Following the initiation of the inflammatory cascade, other virulence factors, such as those associated with the cagA and vacA genes, would maintain the immune response with consequent progressive histological damage (24). Although the relationship between the presence of anti-Le antibodies and disease states is not clear, utilization of transgenic mice models expressing Le determinants (13, 17), coupled with longitudinal studies in humans known to express clonal isolates of H. pylori (41), may help clarify the full significance of anti-Le autoimmunity.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amano K I, Hayashi S, Kubota T, Fujii N, Yokota S-I. Reactivities of Lewis antigen monoclonal antibodies with the lipopolysaccharides of Helicobacter pylori strains isolated from patients with gastroduodenal diseases in Japan. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1997;4:540–544. doi: 10.1128/cdli.4.5.540-544.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Appelmelk B J, Faller G, Claeys D, Kirchner T, Vandenbroucke-Grauls C M J E. Bugs on trial: the case of Helicobacter pylori and autoimmunity. Immunol Today. 1998;19:296–299. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01281-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Appelmelk B J, Monteiro M A, Martin S L, Moran A P, Vandenbroucke-Grauls C M J E. Why Heicobacter pylori has Lewis antigens. Trends Microbiol. 2000;8:565–570. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01875-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Appelmelk B J, Simoons-Smit I, Negrini R, Moran A P, Aspinall G O, Forte J G, de Vries T, Quan H, Verboom T, Maaskant J G, Ghiara P, Kuipers E J, Bloemena E, Tadema T M, Townsend R R, Tyagarajan K, Crothers J M, Jr, Montiero M A, Savio A, de Graaff J. Potential role of molecular mimicry between Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide and host Lewis blood group antigens in autoimmunity. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2031–2040. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2031-2040.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aspinall G O, Monteiro M A. Lipopolysaccharides of Helicobacter pylori strains P466 and MO19: structures of the O antigen and core oligosaccharide regions. Biochemistry. 1996;35:2498–2504. doi: 10.1021/bi951853k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aspinall G O, Monteiro M A, Pang H, Walsh E J, Moran A P. O antigen chains in the lipopolysaccharide of Helicobacter pylori NCTC 11637. Carbohydr Lett. 1994;1:151–156. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aspinall G O, Monteiro M A, Pang H, Walsh E J, Moran A P. Lipopolysaccharide of the Helicobacter pylori type strain NCTC 11637 (ATCC 43504): structure of the O antigen and core oligosaccharide regions. Biochemistry. 1996;35:2489–2497. doi: 10.1021/bi951852s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chmiela M, Wadström T, Folkesson H, Planeta Malecka I, Czkwianianc E, Rechcinski T, Rudnicka W. Anti-Lewis X antibody and Lewis X-anti-Lewis X immune complexes in Helicobacter pylori infection. Immunol Lett. 1998;61:119–125. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(98)00004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Claeys D, Faller G, Appelmelk B J, Negrini R, Kirchner T. The gastric H+,K+-ATPase is a major autoantigen in chronic Helicobacter pylori gastritis with body mucosa atrophy. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:340–347. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70200-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Claeys D, Saraga E, Rossier B C, Kraehenbuhl J P. Neonatal injection of native proton pump antigens induces autoimmune gastritis in mice. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1136–1145. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9322508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunn B E, Cohen H, Blaser M J. Helicobacter pylori. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:720–741. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.4.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edwards N J, Monteiro M, Walsh E J, Moran A P, Roberts I S, High N J. Lewis X structures in the O antigen side-chain promote adhesion of Helicobacter pylori to the gastric epithelium. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:1530–1539. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Falk P G, Bry L, Holgersson J, Gordon J I. Expression of a human α-1,3/4-fucosyltransferase in the pit cell lineage of FVB/N mouse stomach results in production of Leb-containing glycoconjugates: a potential transgenic mouse model for studying Helicobacter pylori infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1515–1519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faller G, Steininger H, Appelmelk B, Kirchner T. Evidence of novel pathogenic pathways for the formation of antigastric autoantibodies in Helicobacter pylori gastritis. J Clin Pathol. 1998;51:244–245. doi: 10.1136/jcp.51.3.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fiocca R, Necchi V, Sommi P, Ricci V, Telford J, Cover T L, Solcia E. Release of Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin by both a specific secretion pathway and budding of outer membrane vesicles. Uptake of released toxin and vesicles by the gastric epithelium. J Pathol. 1999;188:220–226. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199906)188:2<220::AID-PATH307>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greiner A A, Marx J, Heesemann J, Leebmann J, Schmausser B, Müller-Hermelink H K. Idiotype identity in a MALT-type lymphoma and B cells in Helicobacter pylori chronic gastritis. Lab Investig. 1994;70:572–578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guruge J L, Falk P G, Lorenz R G, Dans M, Wirth H P, Blaser M J, Berg D E, Gordon J I. Epithelial attachment alters the outcome of Helicobacter pylori infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3925–3930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heneghan M A, McCarthy C F, Moran A P. Relationship of blood group determinants on Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide with host Lewis phenotype and inflammatory response. Infect Immun. 2000;68:937–941. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.2.937-941.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heneghan M A, Moran A P, Feeley K M, Goulding J, Egan E L, Connolly C E, McCarthy C F. Effect of host Lewis and ABO blood group antigen phenotype on Helicobacter pylori colonisation density and the consequent inflammatory response. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1998;20:257–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1998.tb01135.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hynes S O, Moran A P. Comparison of three serological methods for detection of Lewis antigens on the surface of Helicobacter pylori. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;190:67–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hynes S O, Moran A P. Lewis antigen expression on outer membrane vesicles of Helicobacter pylori: implications for virulence. Gut. 2000;47(Suppl. I):A28. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mollicone R, Bara J, LePendu J, Oriol R. Immunohistologic pattern of type 1 (Lea, Leb) and type 2 (X, Y, H) blood group-related antigens in the human pyloric and duodenal mucosa. Lab Investig. 1985;53:219–227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Montiero M A, Chan K H N, Rasko D A, Taylor D E, Zheng P Y, Appelmelk B J, Wirth H P, Yang M, Blaser M J, Hynes S O, Moran A P, Perry M B. Simultaneous expression of type 1 and type 2 Lewis blood group antigens by Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharides. Molecular mimicry between H. pylori lipopolysaccharides and human gastric epithelial cell surface glycoforms. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:11533–11543. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.19.11533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moran A P. Pathogenic properties of Helicobacter pylori. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31(Suppl. 215):22–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moran A P. Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide-mediated gastric and extragastric pathology. J Physiol Pharmacol. 1999;50:787–805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moran A P, Appelmelk B J, Aspinall G O. Molecular mimicry of host structures by lipopolysaccharides of Campylobacter and Helicobacter spp.: implications in pathogenesis. J Endotoxin Res. 1996;3:521–531. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moran A P, Helander I M, Kosunen T U. Compositional analysis of Helicobacter pylori rough-form lipopolysaccharides. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1370–1377. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.4.1370-1377.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moran A, Knirel Y, Senchenkova S, Widmalm G, Hynes S, Jansson P E. Acid-induced phase variation in Lewis antigen expression by H. pylori lipopolysaccharides. Gut. 2000;47(Suppl. III):A1–A2. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108574200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moran A P, Sturegård E, Sjunneson H, Wadström T, Hynes S O. The relationship between O-chain expression and colonisation ability of Helicobacter pylori in a mouse model. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2000;29:263–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2000.tb01532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Negrini R, Lisato L, Zanella I, Cavazzini L, Gullini S, Villanacci V, Poiesi C, Albertini A, Ghielmi S. Helicobacter pylori infection induces antibodies cross-reacting with human gastric mucosa. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:437–445. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90023-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Negrini R, Savio A, Poiesi C, Appelmelk B J, Buffoli F, Paterlini A, Cesari P, Graffeo M, Vaira D, Franzin G. Antigenic mimicry between Helicobacter pylori and gastric mucosa in the pathogenesis of body atrophic gastritis. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:655–665. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8780570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nyame A K, Pilcher J B, Tsang V C Y, Cummings R D. Schistosoma mansoni infection in humans and primates induces cytolytic antibodies to surface Lex determinants on myeloid cells. Exp Parasitol. 1996;82:191–200. doi: 10.1006/expr.1996.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sakamoto J, Wantanabe T, Tokumara T, Takagi H, Nakazato H, Lloyd K O. Expression of Lewis a, Lewis b, Lewis x, Lewis y, sialyl-Lewis a and sialyl-Lewis x blood group antigens in human gastric carcinoma and in normal gastric tissue. Cancer Res. 1989;49:745–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sherburne R, Taylor D E. Helicobacter pylori expresses a complex surface carbohydrate, Lewis x. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4564–4568. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.12.4564-4568.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skubitz K M, Snook R W. Monoclonal antibodies that recognize lacto-N-fuco-pentos III (CD15) react with the adhesion-promoting glycoprotein family (LFA-1/NMac1/gp150,95) and CR1 on human neutrophils. J Immunol. 1987;137:1631–1639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stöckl J, Majdic O, Rosenkranz A, Fiebiger E, Kniep B, Stockinger H, Knapp W. Monoclonal antibodies to the carbohydrate structure Lewis x stimulate the adhesive activity of leucocyte integrin CD11b/Cd18 (CR3, Mac-1,α(m)β2) on human granulocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 1993;53:541–549. doi: 10.1002/jlb.53.5.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Dam G J, Claas F H J, Yazdanbakhsh M. Schistosoma mansoni excretory CCA shares carbohydrate epitopes with granulocytes and evokes host antibodies mediating complement-dependent lysis of granulucytes. In: van Dam G J, editor. Circulating gut-associated antigens of Schistosoma mansoni: biological, immunological and molecular aspects. Leiden, The Netherlands: University of Leiden; 1995. pp. 174–187. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vollmers H P, Dammrich J, Ribbert H, Grassel S, Debus S, Heesemann J, Müller-Hermelink H K. Human monoclonal antibodies from stomach carcinoma patients react with Helicobacter pylori and stimulate cancer cells in vitro. Cancer. 1994;74:1525–1532. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940901)74:5<1525::aid-cncr2820740506>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walsh E J, Moran A P. Influence of medium composition on the growth and antigen expression of Helicobacter pylori. J Appl Microbiol. 1997;83:67–75. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1997.00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wirth H P, Yang M, Karita M, Blaser M J. Expression of the human cell surface glycoconjugates Lewis X and Lewis Y by Helicobacter pylori isolates is related to cagA status. Infect Immun. 1996;64:4598–4605. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.11.4598-4605.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wirth H P, Yang M, Peek R M, Jr, Hook-Nikanne I, Fried M, Blaser M J. Phenotypic diversity in Lewis expression of Helicobacter pylori isolates from the same host. J Lab Clin Med. 1999;133:488–500. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(99)90026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yokota S-I, Amano K-I, Hayashi S, Fujii N. Low antigenicity of the polysaccharide region of Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharides derived from tumors of patients with gastric cancer. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3509–3512. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3509-3512.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yokota S-I, Amano K-I, Hayashi S, Kubota T, Fujii N, Yokochi T. Human antibody response to Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharide: presence of an immunodominant epitope in the polysaccharide chain of lipopolysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3006–3011. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.3006-3011.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yokota S-I, Amano K-I, Shibata Y, Nakajima M, Suzuki M, Hayashi S, Fujii N, Yokochi T. Two distinct antigenic types of the polysaccharide chains of Helicobacter pylori lipopolysaccharides characterized by reactivity with sera from humans with natural infection. Infect Immun. 2000;68:151–159. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.151-159.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]