Key Points

Question

What are the clinical and pathological features of cutaneous involvement during catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS)?

Findings

In this cohort study of 65 patients with skin involvement during CAPS, livedo racemosa, necrotic lesions, splinter hemorrhages, and vascular purpura, along with distal inflammatory edema, were observed. Skin biopsies showed microthromboses in 15 of 16 cases.

Meaning

Cutaneous CAPS encompasses a wide spectrum of clinical features; skin biopsy is helpful as it may confirm microthrombosis in more than 90% of cases.

Abstract

Importance

Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS) is a severe, rare complication of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), but cutaneous involvement has not yet been adequately described.

Objective

To describe cutaneous involvement during CAPS, its clinical and pathological features, and outcomes.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cohort study was a retrospective analysis of patients included in the French multicenter APS/systemic lupus erythematosus register (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02782039) by December 2020. All patients meeting the revised international classification criteria for CAPS were included, and patients with cutaneous manifestations were analyzed more specifically.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Clinical and pathological data as well as course and outcome in patients with cutaneous involvement during CAPS were collected and compared with those in the register without cutaneous involvement.

Results

Among 120 patients with at least 1 CAPS episode, the 65 (54%) with skin involvement (43 [66%] women; median [range] age, 31 [12-69] years) were analyzed. Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome was the first APS manifestation for 21 of 60 (35%) patients with available data. The main lesions were recent-onset or newly worsened livedo racemosa (n = 29, 45%), necrotic and/or ulcerated lesions (n = 27, 42%), subungual splinter hemorrhages (n = 19, 29%), apparent distal inflammatory edema (reddened and warm hands, feet, or face) (n = 15, 23%), and/or vascular purpura (n = 9, 14%). Sixteen biopsies performed during CAPS episodes were reviewed and showed microthrombi of dermal capillaries in 15 patients (94%). These lesions healed without sequelae in slightly more than 90% (58 of 64) of patients. Patients with cutaneous involvement showed a trend toward more frequent histologically proven CAPS (37% vs 24%, P = .16) than those without such involvement, while mortality did not differ significantly between the groups (respectively, 5% vs 9%, P = .47).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cohort study, half the patients with CAPS showed cutaneous involvement, with a wide spectrum of clinical presentations, including distal inflammatory edema. Skin biopsies confirmed the diagnosis in all but 1 biopsied patient.

This cohort study describes cutaneous involvement during catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome, its clinical and pathological features, and outcomes.

Introduction

Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS) is a rare, severe complication of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), characterized by diffuse small-vessel thromboses involving at least 3 organs and potentially leading to multiorgan failure. The prevalence of CAPS ranges from 1% of patients with APS to 5% in patients with primary APS with longer-term follow-up. Although some cutaneous manifestations linked to APS are well known, including livedo racemosa, ulcers, and necrosis, the literature lacks detailed information on the types of these manifestations and pathological findings during CAPS.

The International CAPS Registry’s recent update reported skin involvement (n = 242) in 47% of the 517 CAPS episodes, including livedo reticularis (92%), cutaneous necrosis (55%), cutaneous ulcers (51%), and purpura (30%), but did not report detailed information about cutaneous manifestations or describe their course. A few case reports have described skin involvement in detail, mostly with extensive skin necrosis. Finally, no study has evaluated the diagnostic role or potential complications of skin biopsies in CAPS, although its classification criteria require histologic proof of small-vessel occlusion for definite diagnosis.

Because, to our knowledge, no large series details the cutaneous manifestations associated with CAPS, and little is known about their clinical or histopathological features or prognosis, we aimed to describe these in this series of patients with CAPS and to compare these patients with those without cutaneous involvement.

Methods

Patients

In this cohort study, the French multicenter APS/systemic lupus erythematosus register (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02782039) had institutional review board approval (previously reported) and included 13 centers (see eMethods in the Supplement). Patients included in the register by December 2020 who met the revised international classification criteria for probable and definite CAPS (see detailed criteria in eMethods in the Supplement) were retrospectively included in this study. Oral consent was obtained for all patients, and written consent was obtained for patients with photographs. Systemic lupus erythematosus was defined by the recent European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria.

Patients with CAPS episodes were classified in 2 groups: with or without cutaneous involvement, based on the medical record, specifically the serial physical examinations described there, almost always by a dermatologist. The supplemental material (eMethods in the Supplement) lists the clinical features used to identify the group with cutaneous involvement. Only the first episode with cutaneous involvement (based on the clinical description in medical records and photographs) was included for patients with more than 1 CAPS episode.

We considered specific cutaneous manifestations at diagnosis and during the course of the CAPS episode, but not isolated chronic cutaneous APS manifestations (especially livedo). More details on the cutaneous assessment are available in the supplemental material (eMethods in the Supplement). To reduce bias, all medical records and photographs were reviewed in a standardized manner and classified by expert opinion (F.C., N.M., and N.C.C.).

Data Collection and Reporting Guideline

Data were collected from medical records at baseline (date of CAPS diagnosis) and last follow-up. We collected potential adverse effects of biopsies, including hemorrhagic complications and worsening of lesions, and analyzed histologic reports. An experienced pathologist (P.M.) read all the available slides, also to reduce bias. We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Statistical Analysis

The descriptive analyses reported medians (range) for continuous variables and numbers (percentages) for categorical qualitative variables. The comparisons used nonparametric tests: Fisher exact test for categorical and the Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables. We performed a subgroup analysis of patients with CAPS with cutaneous lesions in and outside pregnancy. For all 2-sided statistical analyses, P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using R statistical software, version 3.6.1 (R Project for Statistical Computing).

Results

Patient Characteristics

Among the 120 patients with a CAPS episode, 65 (54%) had at least 1 with cutaneous involvement (43 [66%] women; median [range] age, 31 [12-69] years) (Table). Patients with and without cutaneous involvement during CAPS did not differ statistically significantly for sex, age, APS type (primary or associated), or antiphospholipid antibody status. Patients with, compared with those without, cutaneous involvement had liver and adrenal involvement less often: respectively, 31% vs 53% (P = 0.02) and 29% vs 53% (P = .01). Histologically proven CAPS tended to be more frequent among those with cutaneous involvement (37% vs 24%, P = .16). Mortality did not differ significantly (5% vs 9%, P = .47).

Table. Comparison Between Patients With and Without Cutaneous Involvement During Catastrophic Antiphospholipid Syndrome.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with cutaneous involvement (n = 65) | Patients without cutaneous involvement (n = 55) | ||

| Sex | |||

| Female | 43 (66) | 39 (71) | .69 |

| Male | 22 (34) | 16 (29) | |

| APS | |||

| Age at diagnosis of APS, median (range), y | 31 (12-69) | 33 (13-66) | .65 |

| Primary APS | 32 (49) | 29 (53) | .72 |

| Associated APS | 33 (51) | 26 (47) | .72 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 26 (40) | 20 (36) | .71 |

| And/or other autoimmune diseasesa | 13 (20) | 11 (20) | >.99 |

| Antiphospholipid antibodies | |||

| Lupus anticoagulant | 58 (89) | 50 (91) | >.99 |

| Anticardiolipin antibodies | 56 (86) | 51 (93) | .38 |

| Anti-β2GP1 antibodies | 42 (65) | 37 (67) | .85 |

| Triple positivity | 37 (57) | 33 (60) | .85 |

| Chronic livedo associated with APS | 17 (26) | 13 (24) | .83 |

| CAPS | |||

| Age at diagnosis of CAPS, median (range), y | 40 (17-81) | 45 (18-78) | .56 |

| CAPS as first manifestation of APS | 21/60 (35) | 20 (36) | .41 |

| Other CAPS manifestations | |||

| Kidney | 47 (72) | 44 (80) | .39 |

| Cardiac | 45 (69) | 35 (64) | .56 |

| Central nervous system | 28 (43) | 28 (51) | .46 |

| Pulmonary | 21 (32) | 24 (44) | .26 |

| Hepatic | 20 (31) | 29 (53) | .05 |

| Adrenal | 19 (29) | 29 (53) | .05 |

| Abdominal other than adrenal | 16 (25) | 16 (29) | .68 |

| Ocular | 8 (12) | 7 (13) | .28 |

| Venous thrombosis | 21 (32) | 9 (16) | .06 |

| Arterial thrombosis | 16 (25) | 12 (22) | .83 |

| Histologic proof of CAPS | 23/63 (37)b | 13/54 (24) | .16 |

| Treatment | |||

| Anticoagulant | 63 (97) | 53 (96) | >.99 |

| Corticosteroids | 61 (94) | 45 (82) | .05 |

| IV Ig | 35 (54) | 29 (53) | >.99 |

| Plasma exchanges | 31 (48) | 21 (38) | .36 |

| Triple therapyc | 48 (74) | 34 (62) | .17 |

| Aspirin | 25 (39) | 22 (40) | >.99 |

| Rituximab | 10 (15) | 11 (20) | .63 |

| Eculizumab | 4 (6) | 3 (6) | >.99 |

| Death | 3/64 (5) | 5/55 (9) | .47 |

Abbreviations: Anti-β2GP1, antibeta 2 glycoprotein 1; APS, antiphospholipid syndrome; CAPS, catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome; IV Ig, intravenous immunoglobulins.

Other autoimmune diseases included Sjögren syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, immune thrombocytopenia, Crohn disease, vitiligo, and primary biliary cirrhosis.

Including 18 skin biopsies.

Based on corticosteroids, anticoagulants, plasma exchanges, and/or IV Ig.

Dermatologic Characteristics

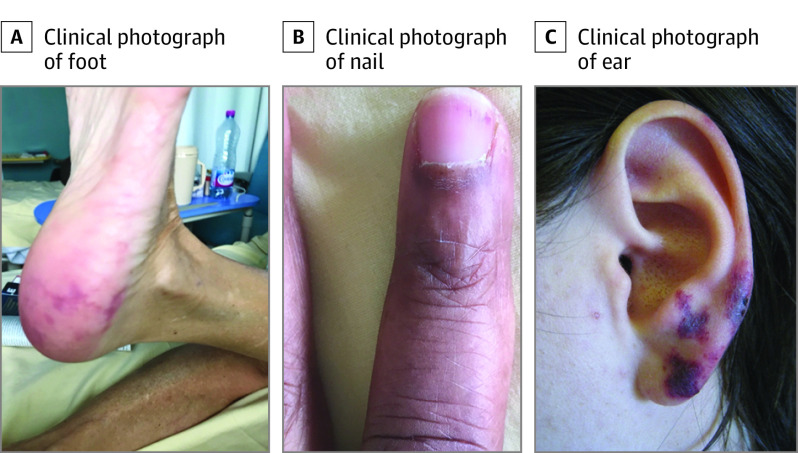

The 65 patients with cutaneous involvement during CAPS episodes presented with newly onset or worsened livedo racemosa (n = 29, 45%), necrotic and/or ulcerated lesions (n = 27, 42%), distal (hands, feet, face) bilateral inflammatory edema (n = 15, 23%), sometimes including purpuric (n = 3, 5%) and/or necrotic lesions (n = 5, 8%), and isolated vascular purpura (n = 9, 14%) (Figure 1). The lesion site was available for 43 patients: lower limbs (n = 19, 44%), upper limbs (n = 18, 42%), and/or face (n = 14, 33%), including ears (n = 13, 30%). The distal inflammatory edema observed in 15 patients was characterized by a painful, warm erythema that evolved rapidly into purpuric lesions and then sometimes necrosis (Figure 2). Four patients (6%) had ear lesions resembling pseudo-chondritis, with inflammatory edema of the ear, sometimes associated with purpuric or necrotic ear lesions (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Cutaneous Involvement During Catastrophic Antiphospholipid Syndrome (Examples in 3 Patients).

A, Recent-onset livedoid rash of the foot. B, Subungual splinter hemorrhages. C, Distal inflammatory edema with purpuric lesions of the ear.

Figure 2. Course of Skin Damage in a Patient With Cutaneous Catastrophic Antiphospholipid Syndrome.

A, Livedoid rash. B, Digital gangrene of 1 toe. C, Digital gangrene of 3 toes.

In addition, 19 patients (29%) presented with subungual splinter hemorrhages, usually associated with other lesions (n = 17) (Figure 1). One patient with these splinter hemorrhages developed digital necrosis on the same finger.

Ear lesions were statistically more frequent during pregnancy: 8 of 12 (67%) vs 5 of 31 (16%) in nonpregnant patients (P = .002) (see additional details in eTable in the Supplement). Moreover, newly onset or worsened livedo racemosa occurred less often in pregnant patients than nonpregnant women: 2 of 16 (13%) vs 27 of 49 (55%) (P = .003) (eTable in the Supplement).

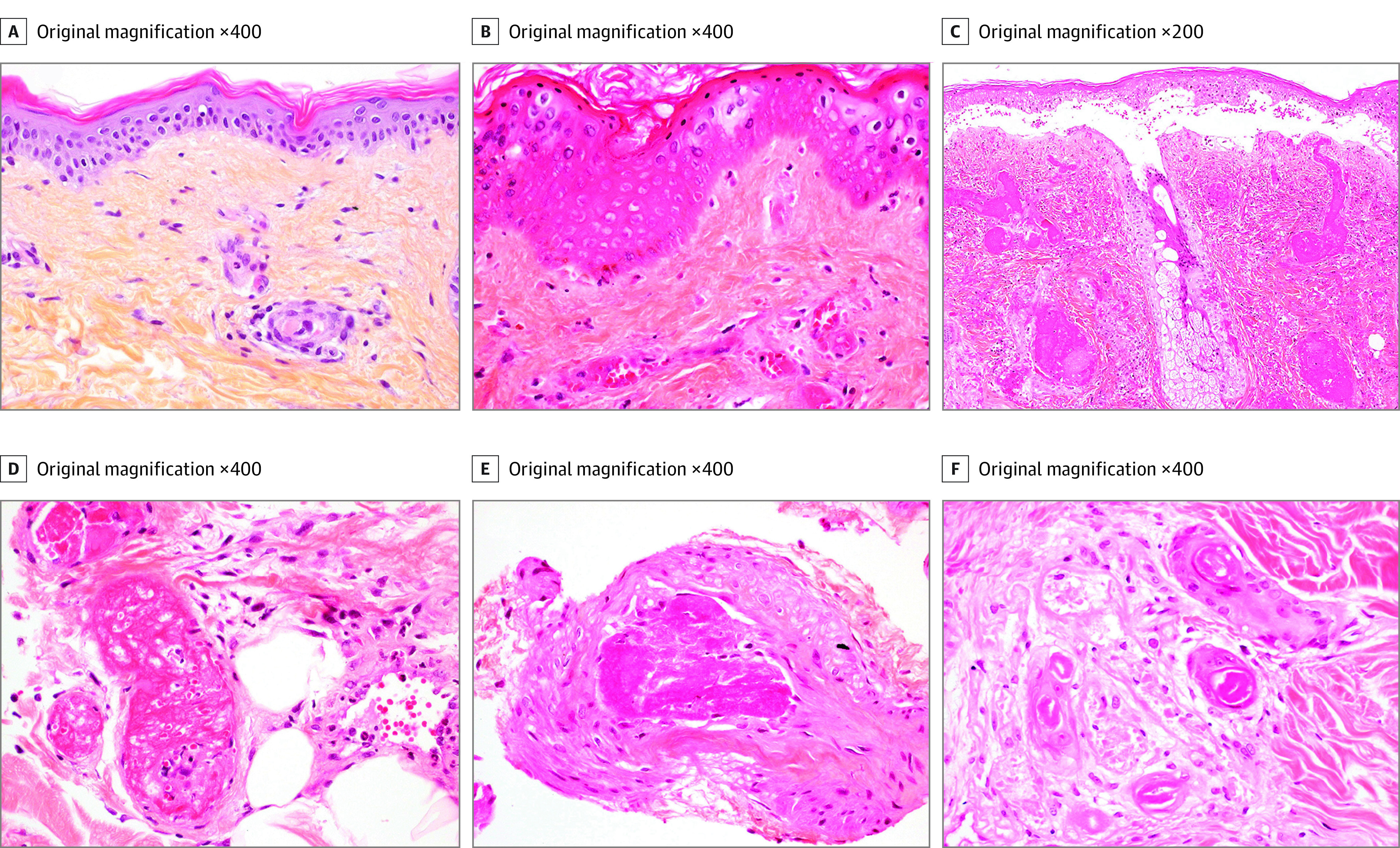

Pathology Findings

Eighteen patients (28%) had a skin biopsy during their CAPS episode, 16 (89%) of which were centralized and reviewed. The histological studies showed microthrombi in 15 of 16 patients (94%), affecting dermal capillaries (see more details in eResults in the Supplement). Figure 3 shows features of histopathological involvement during CAPS.

Figure 3. Histopathologic Findings of Skin Biopsies During Catastrophic Antiphospholipid Syndrome.

Hematoxylin-eosin-saffron (HES) staining. A, Microthrombus in a superficial dermis capillary without inflammation or purpura. B, Microthrombi of superficial dermal capillaries, purpura, and partial ischemic epidermal necrosis. C, Multiple and massive thromboses of the dermal vessels, ischemic epidermal necrosis with bullous junctional detachment, interstitial inflammation, and purpura. D, Multiple deep dermal capillary thrombosis. E, Thrombosis of a vein of the dermohypodermal junction. F, Isolated sweat gland ischemic necrosis.

Outcomes

Finally, 3 of the 64 patients with available data (5%) died during the CAPS episode. Two patients required transtibial amputation, both for macrovascular arterial involvement. No other amputation or autoamputation was observed. One patient had persistent thumb hypoesthesia. Among the 64 patients with available data, 58 (91%) healed without cutaneous sequelae. No adverse effects were reported to be associated with the biopsies, although in 1 patient, necrotic lesions in the lower limbs were suspected of worsening after biopsy. Thus, a skin biopsy appears helpful for confirming the diagnosis and seems to have an acceptable safety profile.

Discussion

This cohort study describes in detail the cutaneous involvement and pathological features of patients with CAPS. Although cutaneous manifestations were frequent in this cohort (54%), their clinical presentation varied widely. Some were known and quite similar to descriptions in the CAPS registry, such as necrotic and/or ulcerated lesions (42% in this study vs necrotic lesions in 55% and ulcers in 51%) and vascular purpura (14% vs 30%). The onset or worsening of livedo racemosa was reported in 45% of this cohort of patients. The registry reported livedo racemosa for 92%, but without indicating if it was due to CAPS or chronically associated with APS. This probably explains this study’s lower rate (another 25% of this cohort had chronic APS-related livedo). Other manifestations have apparently not been described previously, to our knowledge. In particular, we reported that 25% of this cohort of patients had inflammatory edema that was red, warm, painful, located preferentially in the extremities (hands, feet, and/or ears), and probably associated with microcirculatory injuries. This clinical finding contrasts with the standard white or cyanotic and cold appearance of macrocirculatory ischemic lesions generally expected in CAPS and is often initially misdiagnosed as allergy or sepsis. Finally, the splinter hemorrhages in one-third of this cohort of patients indicate the need for careful examination of the nails.

A skin biopsy was performed in fewer than one-third of this cohort of patients, probably because the diagnosis was obvious in some cases or because of disturbed hemostasis and/or its unavailability in emergency CAPS situations. It can nonetheless be useful for diagnosis. Its performance was excellent because microthrombi of dermal capillaries were detected in 94% of these patients, with very few adverse effects of the biopsies. The histologic evidence allowed us to classify CAPS episodes as definite. Thus, histologic proof of CAPS was more frequent, although not significantly so, in the group with skin involvement. This finding confirms the relative ease of performing a skin biopsy compared with those of other organs.

The prognosis of these cutaneous lesions was good in this study’s cohort; they healed without substantial sequelae in most patients, despite some extensive necrotic lesions. This is consistent with a case report describing the complete healing of extensive bullous necrotic lesions. The favorable outcome is probably associated with the microthrombotic mechanism involved, as seen in cholesterol embolism disease, in contrast to a macrothrombotic mechanism. Only 2 patients required amputation, due to associated macrovascular (arterial) disease, which must be sought when distal necrotic lesions are present.

The mortality rate (5%) was low in this cohort, contrasting with a mortality of 37% in the International CAPS Registry, probably because the CAPS included in this cohort were more recent (only 4 episodes before 2000, the year the first guidelines were published) and received treatment in accordance with current recommendations. When we compared patients with cutaneous involvement during CAPS with the rest of the cohort, we found no significant difference regarding the clinical and biological characteristics of their APS, except that the rest of the cohort had more adrenal and hepatic involvement, likely because CAPS requires the involvement of at least 3 organs: if the skin is not involved, another organ must be.

Limitations

The main limitation of the present study is its retrospective nature: data may be missing, especially details about these lesions’ precise course and natural history. Other limitations are the small number of cases due to the rarity of this pathology and the lack of systematic examination by a dermatologist. Nonetheless, most patients were seen by dermatologists and when they were not, they most often received care from experienced internists in referral centers.

Conclusions

In this cohort study, we report the wide variety of skin involvement during CAPS and their healing without major sequelae in most patients. A careful dermatological examination is important in the context of organ failure, and the recognition of these lesions might be helpful for diagnosing CAPS.

eMethods. Supplementary methodological details

eResults. Pathology findings

eTable. Comparison of cutaneous involvement between patients with catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS) in or outside pregnancy

References

- 1.Asherson RA. The catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome. J Rheumatol. 1992;19(4):508-512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cervera R, Serrano R, Pons-Estel GJ, et al. ; Euro-Phospholipid Project Group (European Forum on Antiphospholipid Antibodies) . Morbidity and mortality in the antiphospholipid syndrome during a 10-year period: a multicentre prospective study of 1000 patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(6):1011-1018. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taraborelli M, Reggia R, Dall’Ara F, et al. Longterm outcome of patients with primary antiphospholipid syndrome: a retrospective multicenter study. J Rheumatol. 2017;44(8):1165-1172. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.161364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Francès C, Niang S, Laffitte E, Pelletier Fl, Costedoat N, Piette JC. Dermatologic manifestations of the antiphospholipid syndrome: two hundred consecutive cases. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(6):1785-1793. doi: 10.1002/art.21041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cervera R, Piette JC, Font J, et al. ; Euro-Phospholipid Project Group . Antiphospholipid syndrome: clinical and immunologic manifestations and patterns of disease expression in a cohort of 1,000 patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46(4):1019-1027. doi: 10.1002/art.10187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodríguez-Pintó I, Moitinho M, Santacreu I, et al. ; CAPS Registry Project Group (European Forum on Antiphospholipid Antibodies) . Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS): descriptive analysis of 500 patients from the International CAPS Registry. Autoimmun Rev. 2016;15(12):1120-1124. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2016.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sadick V, Lane S, Fischer E, Seppelt I, Shetty A, McLean A. Post-partum catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome presenting with shock and digital ischaemia—a diagnostic and management challenge. J Intensive Care Soc. 2018;19(4):357-364. doi: 10.1177/1751143718762343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Incalzi RA, Gemma A, Moro L, Antonelli M. Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome presenting with multiorgan failure and gangrenous lesions of the skin. Angiology. 2008;59(4):517-518. doi: 10.1177/0003319707305404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amital H, Levy Y, Davidson C, et al. Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: remission following leg amputation in 2 cases. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2001;31(2):127-132. doi: 10.1053/sarh.2001.27660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Townsend LR, Cotton JP, Altman DA, Gildenberg SR. Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67(5):e214-e216. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aghdashi M, Aghdashi M, Rabiepoor M. Cutaneous necrosis of lower extremity as the first manifestation of catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome. Mod Rheumatol. 2015;25(3):490-492. doi: 10.3109/14397595.2014.882222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Legault K, Schunemann H, Hillis C, et al. McMaster RARE-Bestpractices clinical practice guideline on diagnosis and management of the catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome. J Thromb Haemost. 2018;16(8):1656-1664. doi: 10.1111/jth.14192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Asherson RA, Cervera R, de Groot PG, et al. ; Catastrophic Antiphospholipid Syndrome Registry Project Group . Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: international consensus statement on classification criteria and treatment guidelines. Lupus. 2003;12(7):530-534. doi: 10.1191/0961203303lu394oa [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erkan D, Espinosa G, Cervera R. Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: updated diagnostic algorithms. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;10(2):74-79. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2010.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morel N, Bonnet C, Mehawej H, et al. Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome and posterior ocular involvement: case series of 11 patients and literature review. Retina. 2021;41(11):2332-2341. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0000000000003185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aringer M, Costenbader K, Daikh D, et al. 2019 European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78(9):1151-1159. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-214819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mufti A, Maliyar K, Syed M, Pagnoux C, Alavi A. Approaches to microthrombotic wounds: a review of pathogenesis and clinical features. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2020;33(2):68-75. doi: 10.1097/01.ASW.0000617860.92050.9e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bucciarelli S, Espinosa G, Cervera R, et al. ; European Forum on Antiphospholipid Antibodies . Mortality in the catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: causes of death and prognostic factors in a series of 250 patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54(8):2568-2576. doi: 10.1002/art.22018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tektonidou MG, Andreoli L, Limper M, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of antiphospholipid syndrome in adults. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78(10):1296-1304. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2019-215213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Supplementary methodological details

eResults. Pathology findings

eTable. Comparison of cutaneous involvement between patients with catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS) in or outside pregnancy